Introduction

Black flies (Diptera: Simuliidae) possess phylogenetically informative polytene chromosomes in the salivary glands of their larvae, and many taxa originally described as single species are actually complexes of more than one species, based on descriptions of their sex chromosome segments (Rothfels Reference Rothfels1979; Shields and Procunier Reference Shields and Procunier1982). The majority of these chromosome types within complexes differ by sex-linked paracentric inversions in males that are easily detected (Rothfels and Featherston Reference Rothfels and Featherston1981; Shields and Procunier Reference Shields and Procunier1982; Adler et al. Reference Adler, Currie and Wood2004; Shields Reference Shields2013). Rearranged Y chromosomes are almost always the first indicators of different taxa within these complexes (Conflitti et al. Reference Conflitti, Shields, Murphy and Currie2016), and consequently without analysis of larval polytene chromosomes, many taxa would have gone unrecognised (Rothfels Reference Rothfels1989). For example, the biter of cattle in Alberta and Saskatchewan, Canada is actually Simulium arcticum, IIL-8 (inversion number 8 in the long arm of chromosome II; Procunier Reference Procunier1984), and it is only one member of the complex. This taxon has since been described as a good biological species, S. vampirum (Adler et al. Reference Adler, Currie and Wood2004). Initially, only the rearranged chromosomes were used to identify these types from both larval salivary glands and adult Malpighian tubule polytenes; therefore, if studied cytogenetically, their identity and behaviour could be determined. This approach both facilitated and validated their specific control in the Athabasca River region of north–central Alberta (Procunier Reference Procunier1984).

At least 11 species complexes of black flies have been described for North America, and the number increases to 45 species worldwide (Adler Reference Adler2019). Once complexes are described, biological features of the taxa can be studied further, and some are recognised as good biological species (Adler et al. Reference Adler, Currie and Wood2004). For example, in the S. arcticum complex, 31 taxa have been described (Shields and Procunier Reference Shields and Procunier1982; Adler et al. Reference Adler, Currie and Wood2004; Shields et al. Reference Shields, Clausen, Marchion, Michel, Styren and Riggin2007; Shields and Shields Reference Shields and Shields2018; Shields and Hokit Reference Shields and Hokit2019; Shields and Procunier Reference Shields and Procunier2019), and nine of these have been named as good biological species (Adler et al. Reference Adler, Currie and Wood2004).

The central and northeastern region of Washington state, United States of America, is relatively unstudied, with only seven species of black flies described from just two counties and taxa from the S. arcticum complex recorded from earlier collections (Adler et al. Reference Adler, Currie and Wood2004).

Our previous studies have included larvae collected from freshwater streams in Alaska and western Canada (Shields and Procunier Reference Shields and Procunier1982; Procunier Reference Procunier1984; Shields Reference Shields2016; Shields and Hokit Reference Shields and Hokit2016). More recently, the Shields laboratory at Carroll College (Helena, Montana, United States of America) has studied the cytogenetics of S. arcticum from the Pacific Northwest region of the United States of America (Table 1). In the present study, we extended these distributional studies by analysing the chromosomes of black flies in the central and northeastern region of Washington state, a nine-county area of about 40 000 km2. Simulium saxosum (S. arcticum IIL-2) is widespread west of the Rocky Mountains (Shields and Kratochvil Reference Shields and Kratochvil2011). We hypothesised that we would find this taxon in central and northeastern Washington state and also that we might find new undescribed types of S. arcticum s/l.

Table 1. Previous analyses of Simulium arcticum taxa in the Pacific Northwest, United States of America.

Materials and methods

From 20 to 22 April 2019, we drove the major highway systems in the northeastern corner of Washington state and collected black fly larvae from freshwater streams. Our route included State Route 20, north of Spokane to the towns of Newport, Colville, Republic, Tonasket, and Omak, south on US Highway 97 to the towns of Okanogan, Brewster, Pateros, and Entiat, and finally east on US Highway 2 through Waterville, Coulee City, Wilbur, and Davenport, then back to Spokane, Washington (Fig. 1). In 2020, one of us (JPS) returned to the Little Spokane River (15 March 2020), the Methow River (25 March 2020), Mill Creek, and the Colville River (4 April 2020) to collect more larvae. He also collected larvae from the Wenatchee and Entiat rivers (24 March 2020; Fig. 1). Collecting after this time was constrained by the state-wide COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.

Fig. 1. Collection locations of black flies in central and northeastern Washington state, United States of America.

At these locations, we sampled rivers and streams for black fly larvae. At each site, we recorded stream name, water temperature, and global positioning system coordinates. We sampled in the swiftest locations of the streams wherever possible and fixed larvae in freshly made Carnoy’s solution (3:1 ethanol:glacial acetic acid). This solution was held at 4 °C in a cooler and was changed until its supernatant became clear (usually four changes). Larger rivers (e.g., Columbia, Okanogan, and Pend Oreille rivers) were not sampled: black fly larvae occur at the deepest portions of these larger rivers, and their flow rates were much higher (142 m3/second) than was considered safe for collecting. In the laboratory, we identified black fly larvae to species by observing pupal respiratory filaments, dorsal head patterns, and postgenal clefts (Currie Reference Currie1986; Adler et al. Reference Adler, Currie and Wood2004).

Larvae of the S. arcticum complex that had white or grey gill histoblasts were chosen for the chromosome study. It is at these developmental stages, as indicated by the colour, that polytene chromosomes are optimal for analysis (Shields and Procunier Reference Shields and Procunier2019). We scored each larvae examined in the chromosome study for all inversions but particularly for inversions in the long arm of chromosome II and for the autosomal inversion, IS-1. It was possible to detect heterozygotes for this large inversion (Shields and Procunier Reference Shields and Procunier2019), but scoring the inversion homozygotes was difficult due to the quality of the chromosomes. As a result, a detailed analysis of the homozygous inverted genotype was not included in this analysis. Because unavoidable attrition of chromosomally analysable larvae at sites collected for the first time always occurs, we (JPS) returned to some S. arcticum sites in 2020 to increase the sample sizes. The attrition may be due to larvae being either too immature or too mature for chromosome analysis or being infected by mermithid nematodes (Mermithidae) (Adler et al. Reference Adler, Currie and Wood2004). Mermithid nematodes enter the larvae by piercing the integument (Molloy and Jamnback Reference Molloy and Jamnback1975) and appear to preferentially ingest gonads of both sexes first (Shields, unpublished data), although this is only one interpretation of the larvae. Although the polytene chromosomes are analysable, there can be no positive determination of sex in the infected larvae; therefore, these larvae were not included in our analyses.

Larvae having white or grey gill histoblasts were opened ventrally, placed in tap water for one hour, and blotted onto filtre paper to remove silk. They were hydrolysed in a prewarmed vial of normal hydrochloric acid at 64 °C for nine minutes, then stained in Feulgen for one hour in the dark (Rothfels and Dunbar Reference Rothfels and Dunbar1953). Stained larvae were rinsed in SO2 and H2O for 30 minutes and placed in tap water overnight. Salivary glands and gonads were removed from each larva, placed on the same microscope slide, covered with a coverslip, and gently squashed to flatten and spread the chromosomes (Shields and Procunier Reference Shields and Procunier1982). We used the chromosome maps of Shields and Procunier (Reference Shields and Procunier1982) and Adler et al. (Reference Adler, Currie and Wood2004) to analyse taxa of the S. arcticum complex.

Results

We made 28 collections of black flies at 24 sites in central and northeastern Washington (Table 2). In 2019, we collected 11 species, including S. arcticum at 21 of 22 sites (Table 2). Simulium canonicolum Dyar and Shannon was the most abundant species, being present at 11 sites in seven counties. Simulium canadense Hearle occurred at eight sites in five counties, whereas the Helodon onychodachtylus Dyar and Shannon complex occurred at nine sites in three counties. In 2020, JPS collected again at Mill Creek and the Colville, Little Spokane, and Methow rivers, as well as the Entiat and Wenatchee rivers, which were not collected in 2019. He found S. arcticum, as well as S. canadense and Helodon onychodachtylus, at each of these sites (Table 2). In total, 10 species that were not S. arcticum species occurred at five or fewer sites. These taxa are the subject of a separate study and will not be discussed further here. In the two years of this study, we obtained S. arcticum larvae at 11 sites, six of which had relatively large sample sizes and five of which (Priest and Kettle rivers and Deadman, Sherman, and Granite creeks) had small sample sizes. We summarise below each site that yielded S. arcticum that we chromosomally analysed; see Table 3 for details for each site.

Table 2. Black flies collected in this study, central and northeastern Washington state, United States of America.

Table 3. Chromosome diversity within the Simulium arcticum complex, central and northeastern Washington state, United States of America. X0 and Y0, the standard, noninverted chromosome; IIL (any number), the numbered inversion in the long arm of chromosome II; Ce, enhanced centromere band; Ct, thin centromere band.

Colville River

This site has at least six types of male chromosomes (Table 3). Simulium brevicercum, S. arcticum IIL-21, and S. arcticum IIL-83 were the most prevalent, whereas the other chromosomes occurred only once, which prevented us from determining whether these inversions were sex-linked. The IS-1 autosomal inversion was not found at this site. Because some of the 2019 larvae and most of the 2020 larvae at this site were infected with nematodes, the sex of the larvae could not be determined. As a result, these larvae were not included in our analyses.

Deadman Creek

We obtained only 13 larvae that could be chromosomally analysed from this site (Table 3). Simulium brevicercum, S. arcticum IIL-21, and S. arcticum IIL-51 were present here. Three of these larvae were IS-1 st/i, for a proportion of 0.231 of all of the larvae.

Entiat River

We collected from this site only in 2020. Simulium brevicercum and S. saxosum were the most prevalent. The remaining four types (including IIL-3 and IIL-22) occurred only once; therefore, we do not know if these inversions are sex-linked or autosomal (Table 3). More than half of the 41 larvae were IS-1 st/i, for a proportion of 0.512 of all of the larvae.

Granite Creek

Simulium brevicercum, S. saxosum, and S. arcticum IIL-21 occurred at this site, although only in small numbers. Three of the 11 larvae analysed were IS-1 st/i, for a proportion of 0.273 of all of the larvae.

Kettle River

Simulium brevicercum, S. saxosum, and S. arcticum IIL-51 and IIL-81 were present at this site. Five of the 14 larvae analysed are IS-1 st/i, for a proportion of 0.357 of all of the larvae.

Little Spokane River

We analysed 106 S. arcticum larvae from this site. In both 2019 and 2020, S. brevicercum and S. arcticum IIL-21 were the most prevalent. Simulium arcticum IIL-86 occurred rarely. The autosomal IS-1 inversion does not occur at this site.

Methow River

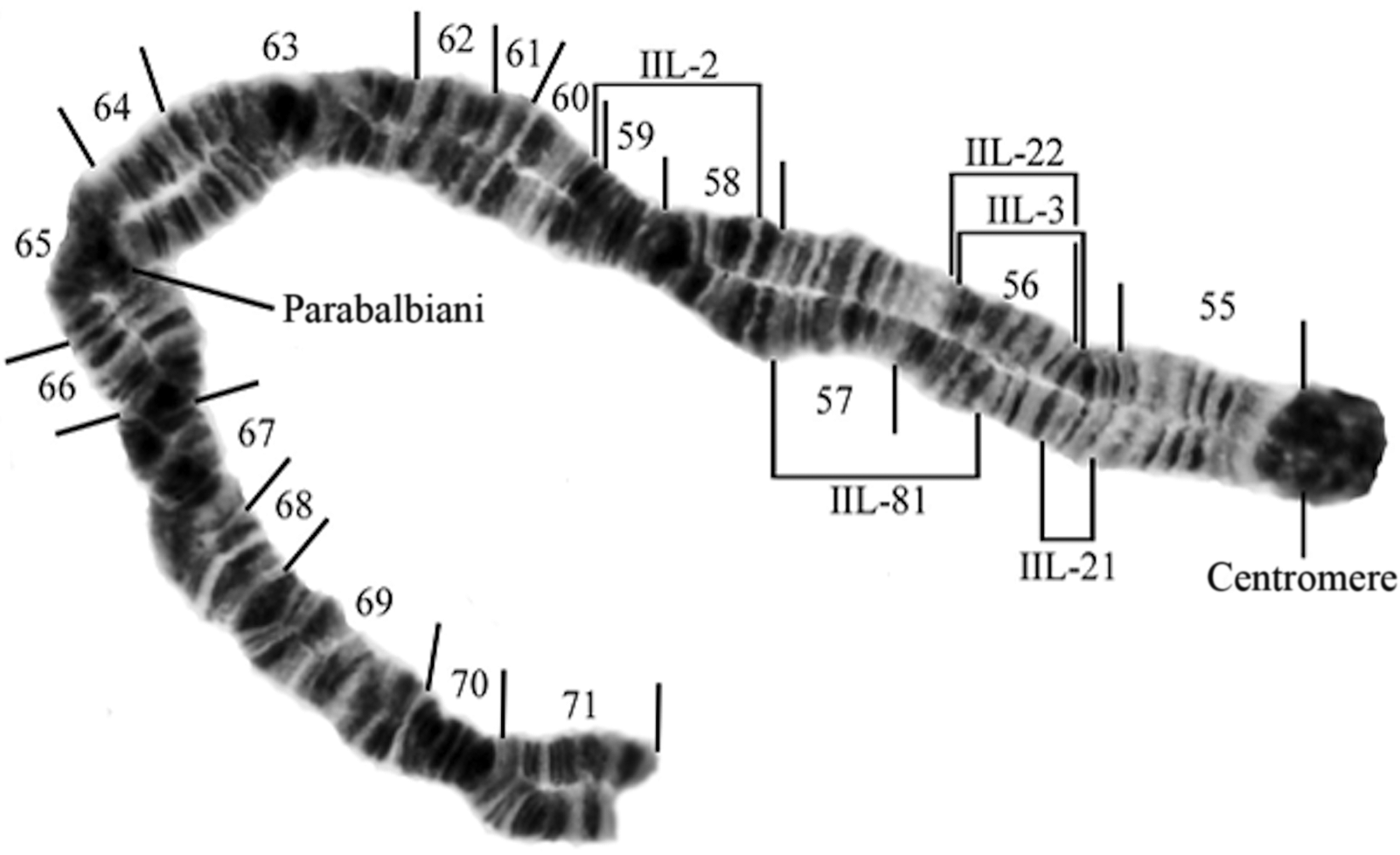

We analysed 261 S. arcticum larvae from this site. Nine types of male chromosomes were found among the 2019 larvae, and eight were found among the 2020 larvae (Table 3). The Methow River is a S. brevicercum/S. saxosum site; it also is home to a cytotype new to science, S. arcticum IIL-81, which occurred in 16 of 73 males collected in 2019 and in 10 of 53 males collected in 2020 (Table 3; Fig. 2). The remainder of male types occurred only rarely. Eighty-seven of 261 larvae were IS-1 heterozygotes, for a proportion of 0.333 of all of the larvae.

Fig. 2. The long arm of chromosome II (IIL-) showing the breakpoints of the relevant inversions of this study (Simulium brevicercum, IIL-standard; S. saxosum, IIL-2; S. arcticum s.s., IIL-3; S. arcticum IIL-21, S. arcticum IIL-22, and S. arcticum IIL-81).

Mill Creek

We analysed 104 larvae collected from this site in 2020 (Table 3). Mill Creek is home to S. brevicercum/S. arcticum IIL-21, with the latter type being the most prevalent of all male types. All other types are rare. Only nine of the 104 larvae collected in 2020 were IS-1 st/i, for a proportion of 0.087 of all of the larvae.

Priest River

Only six S. arcticum larvae were collected here. They were not chromosomally analysed.

Sherman Creek

Only one S. arcticum larva was collected. It was not analysed chromosomally.

Wenatchee River

The Wenatchee River is a S. brevicercum/S. saxosum site. Three S. arcticum s.s. types also occurred here. Other types are rare. Thirty-six of the 107 larvae were IS-1 heterozygotes, for a proportion of 0.336 of all of the larvae.

These data may have a geographic component. We were able to obtain relatively large sample sizes from six sites – three in tributaries of the Columbia River in western Washington and three in tributaries of the Columbia River in eastern Washington. The three sites in western Washington are linked by three chromosome markers, whereas the three sites in eastern Washington are linked by three alternative markers (Table 4). Statistics for the three sites with small sample sizes (Deadman Creek, Granite Creek, and Kettle River) are difficult to interpret. The absence of the IIL-2 inversion at Deadman Creek could be an effect of sample size. However, the presence of IIL-21Y there may indicate that is either autosomal or that the cytotype is sex-linked and rare.

Table 4. Similarities in proportions of IIL-Y0, and dissimilarities in proportions of IIL-2X, IIL-21Y, and heterozygosities of the IS-1 autosomal inversion in populations of the Simulium arcticum complex in western tributaries of the Columbia River and eastern tributaries of the Columbia River, Washington state, United States of America.

Discussion

Simulium canadense, S. arcticum s/l, S. canonicolum, and Helodon onychodachtylus were found at 10 or more sites. Prosimulium exigens was found at four sites, P. formosum at two sites, and P. esselbaughi, S. vittatum, S. bivittatum, and the S. vernum species group were found at only one site.

Simulium brevicercum is the most prevalent taxon of the S. arcticum complex in this study area, being the most abundant male type, except at the Little Spokane River site, where S. arcticum IIL-21 males predominate. This is not surprising: S. brevicercum is both geographically widespread and molecularly diverse. Its distribution occupies 2.3 million square kilometres (Shields and Procunier Reference Shields and Hokit2019), and it occurs in all lineages of our mitochondrial DNA trees (Conflitti et al. Reference Conflitti, Shields, Murphy and Currie2016).

Simulium saxosum (IIL-2) and S. arcticum IIL-21 are the next most abundant types of this study, but they are essentially geographically separated, with S. saxosum occurring in the Columbia River’s western tributaries and S. arcticum IIL-21 occurring in the river’s eastern tributaries. Moreover, the IS-1 autosomal inversion is also informative in this study. All populations of S. arcticum with large sample sizes in the western tributaries of the Columbia River (Wenatchee, Entiat, and Methow rivers) possess heterozygotes for this marker in abundance, whereas eastern tributaries of the Columbia (Colville and Little Spokane rivers and Mill Creek) essentially lack this inversion. This adds credence to the presence of IIL-2 and absence of IIL-21 in the western tributaries and to the absence of IIL-2 and presence of IIL-21 in the eastern tributaries. Female black flies having the IIL-2 inversions may prefer to lay their eggs in western tributaries, whereas females having the IIL-21 inversion but lacking the IIL-2 and IS-1 inversions may prefer to lay their eggs in eastern tributaries.

The IIL-21 inversion is deceptively similar to the IIL-standard banding sequence. The standard banding sequence reads as follows: chromocentre, three sharp bands, wavy puff, three little bands (with the third band being darker), and then the faint band. The IIL-21 inversion reverses the little three and faint bands, such that its sequence reads as follows: chromocentre, three sharp bands, wavy puff, faint, and three little bands (with the dark band of the little three being closest to the faint band). The IIL-21 inversion is the smallest inversion we have found in 24 years of study. In the heterozygotic condition, it does not form a reverse loop.

The presence of IIL-21 larvae in the Little Spokane River is of interest. Previous studies of the Spokane River (State Line and Riverside State Park sites) revealed larvae that lack this inversion completely and are dominated by the IIL-9 inversion. Despite this, IIL-21 occurs at the narrower Latah (Marshall) Creek site, where IIL-9 is absent. The Latah Creek site is only 25 km south of the Little Spokane River (Shields Reference Shields2013). Female black flies having the IIL-21 inversion may prefer to lay their eggs in these narrower rivers rather than in the wider Spokane River.

Although we found S. saxosum larvae, as expected, in the western region of our study area, we found it mostly as X0 XIIL-2 and XIIL-2 Y0 heterozygotes in females and males, respectively (Table 3). Usually S. saxosum occurs as XIIL-2 XIIL-2 homozygotic females and XIIL-2 Y0 heterozygotic males, such as those found at the Cle Elum River in western Washington (Shields Reference Shields2014). Central and western Washington state deserves more study, especially regarding S. saxosum.

This study revealed 13 inversions (S. arcticum IIL-81 to IIL-87 and IIL-89 to IIL-94) new to science. All of these new inversions were found in very low frequencies – usually only once per site, with the exception S. arcticum IIL-81, which was found in one female and 26 male larvae at the Methow River. Most collections of S. arcticum have a number of different male chromosome types (Shields Reference Shields2013); as a result, the diversity at the Methow, with its large sample size (n = 261), is expected. However, in the two years of study at the Methow River, 13 different male chromosome types were found to be present. Moreover, on average one-third of all S. arcticum larvae at the Methow are IS-1 autosomal heterozygotes. Careful study of the Methow River, including scoring of the inversion homozygotes, is warranted.

All female S. arcticum of this study possess the Ce Ce (expanded) centromere structure, whereas all males except one (which was Ct Ct) possess the Ce Ct (expanded, thin) structure (Fig. 3). This marker is clearly sex-linked (Shields Reference Shields2013), but we do not know its effect among flies of either sex.

Fig. 3. The centromere band heterozygote (Ce Ct) of a male Simulium arcticum.

The presence of single IIL-3 and IIL-22 males among 17 male larvae of the Entiat River and among two IIL-3 males at the Wenatchee River is surprising. Simulium arcticum s.s. IIL-3 males are found abundantly at sites in the eastern Rocky Mountains (Shields Reference Shields2013), and S. arcticum IIL-22 has been found only at the Clearwater River Campground site (Shields et al. Reference Shields, Christiaens, Van Luvan and Hartman2009), more than 600 km to the east. These two observations might be examples of what Rothfels (Reference Rothfels1989) described “as one site’s sex-linked inversion being another site’s autosomal inversion.” Another interpretation is that these inversions may be sex-linked but very rare in this area.

The presence of an IIL-9 female at the Little Spokane River is not surprising: IIL-9 occurs in abundance in males nearby at the Spokane River (Shields Reference Shields2013). In a survey of about 15 000 larvae from 234 collections, four IIL-9/IIL-9 males were observed (Shields Reference Shields2013). These two observations may suggest that the IIL-9 inversion is relatively recent and is not yet heterozygotic or totally restricted to males.

At least 20 species of mermithid nematodes infect larval black flies (Molloy Reference Molloy1981; Adler et al. Reference Adler, Currie and Wood2004). Although we have not identified these nematodes to the species level, Peterson (Reference Peterson1960) and Speir (Reference Speir1975) indicate that the genus Gastromermis infects individual larvae of the Simulium arcticum complex. Nematodes appear to preferentially consume gonads rather than polytene chromosomes (Shields, unpublished data), which makes the identification of larval sex difficult and restricts cytogenetic analysis. If some larvae are infected (observation via dissection microscope at the site), more vials can be collected in the hope that at least some larvae collected are not infected. Our recommendation is to collect at any site for at least two years. The first year could reveal the presence or absence of the target taxon or taxa, water temperature, stage of development, and whether larvae are infected. Males, which are most informative regarding chromosomal diversity, usually develop before females (Shields Reference Shields2015), and this knowledge could inform the appropriate collection date during the second year. We collected earlier in 2020 than in 2019 at the Colville, Little Spokane, and Methow rivers and at Mill Creek, hoping to obtain relatively more males. However, more females than males were obtained at these sites in 2020. Stream temperatures were uniformly warmer in 2019, so even though water temperatures were cooler in 2020, we still collected relatively more females. This suggests that appropriate collection dates for white-histoblast larvae are difficult to determine and include knowledge of season, water temperature, development rates, and other unknown factors.

Summary

This study reported 10 black fly taxa in the central and northeastern Washington region, three of which have been previously reported. Western tributaries of the Columbia River that yielded large sample sizes revealed relatively high proportions of S. brevicercum, S. saxosum, and heterozygosities for IS-1, but these tributaries lack the IIL-21 inversion. Eastern tributaries of the Columbia River that yielded large sample sizes showed relatively high proportions of S. brevicercum and S. arcticum IIL-21, but they lack both S. saxosum and the IS-1 autosomal polymorphism. A cytotype new to science, S. arcticum IIL-81 (26 of 126 males and only one female), was found at the Methow River. All female S. arcticum possessed the Ce Ce centromere region, whereas all males but one had the Ce Ct genotype.

Acknowledgements

Carroll College, Helena, Montana, United States of America provided laboratory space and some supplies to G.F. Shields. G.D. Hokit and D. Case helped with figures. Patricia Shields helped with collections. Dr. Peter Adler, Clemson University, South Carolina, United States of America, reviewed and commented on an earlier draft of this manuscript.