Introduction

The pine wood nematode (PWN), Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Steiner and Buhrer) Nickle (Aphelenchida: Parasitaphelenchidae), is a devastating forest pest and its spread is still increasing (Dwinell Reference Dwinell1997). Recently, the main pine species killed by the PWN in southeast China has changed from Pinus thunbergii Parlatore (Pinaceae) to Pinus massoniana Don. Of the total dead pine trees, the proportion of dead P. massoniana in the forest has increased from 10% to 50% since 1985. Now the PWN is reported in 15 provinces in China. Some provinces, such as Zhejiang, Anhui, and Jiangsu, have suffered severe pine wilt disease outbreaks. More than 5.2 million pine trees were killed by PWN in Jiangsu alone from 1982 to 2003 (Xu Reference Xu2008). Present research is focused on finding a way to control PWN’s principal vector, the pine sawyer beetle (PSB), Monochamus alternatus Hope (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). The adult of M. alternatus emerges from a dead pine tree in early summer carrying numerous nematodes in its tracheae. It flies to a healthy pine tree for maturation feeding on the soft bark of young twigs. As the beetle feeds, nematodes exit from the PSB spiracles and enter the tree through the feeding wound. Once within the plant, the nematodes reproduce rapidly and the infected tree shows symptoms of decline about three weeks later. Beetles that have fed and matured over some three weeks are attracted to such diseased trees and oviposit under the stem bark. The eggs hatch within a week and the larvae feed in the phloem area. The final or fourth instar bores into the sapwood to form a pupal chamber in which it hibernates. In spring, JIII (third instar of juvenile) nematodes aggregate around the chamber wall and, as the beetle pupa transforms, they moult to JIV and move into the spiracles of the callow sawyer beetle adult (Kondo et al. Reference Kondo, Linit, Smith, Bolla, Winter and Dropkin1982). In China, the disease cycle is very similar to that in Japan and South Korea. However, the disease cycle in United States of America, Canada, and Mexico in North America and Portugal and Spain in southern Europe are different since its principal vectors and hosts damaged differ (Sutherland Reference Sutherland2008; Xu Reference Xu2008). It is especially important to use biological, chemical, and physical methods to halt this cycle and control the PSB, the main vector of PWN. In China intensive quarantine, clear cutting, and methyl bromide fumigation of dead pine trees are used to control PWN and its principal vector, PSB. Both aerial and ground spray insecticides can significantly reduce the death of pine trees. Other treatments sometimes used to control the PSB, include spraying MPP (O,O-Dimethyl-O-[3-methyl-4-(methylthio)phenyl] phosphorothioate) oil emulsion on stumps, hot water treatment, chipping dead wood, high temperature treatment, submerging in water, burying slash, and using attractants to lure and kill the PSB. Each of these measures can exert some control the PWN. However, in large areas, it may be that the treatments can be effective, but the application was not satisfactory (Dwinell Reference Dwinell1997; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Xu, Xie, Zhang., Shin and Cheong2008). After clear-cutting the dead pine trees, the remaining slash and stumps can be colonised by the larvae of the PSB.

The parasitoid Scleroderma guani Xiao and Wu (Hymenoptera: Bethylidae) has been evaluated for its relative efficacy to parasitise Anoplophora glabripennis (Motschulsky) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) (Asian longhorned beetle), Saperda populnea (Linnaeus) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae), Xylotrechus grayii (White) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae), Phytoecia rufiventris Gautier (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae), and M. alternatus in order to develop mass rearing technology (Yao and Yang Reference Yao and Yang2008). Results from studies of S. guani, to date, have shown that S. guani is an idiobiont ectoparasitoid. Females first paralyse their host by stinging, which immobilises the host, and then lay eggs on the host body. Larvae are gregarious while developing on their host. After hosts are consumed, mature wasp larvae spin cocoons and pupate. An average of 45 adult S. guani emerge from a single mature host larva of S. populnea. In nature, S. guani was found parasitising 41.9–92.3% of S. populnea larvae in poplar stands in many areas (Yang and Michael Reference Yang and Michael2001). Scleroderma guani is one of the most common biocontrol agents attacking larvae of the PSB. Intensive breeding and release of a natural enemy of S. guani to control M. alternatus larvae along with extensive removal of host stumps and logging slash have achieved good control results and have been a major recent management focus (Yang Reference Yang2004; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Xu, Xie, Zhang., Shin and Cheong2008). In order to manage this pest, we have conducted biological control studies for more than 10 years. The success of biological control depends on an efficient mass rearing system for the parasitoids and the production of large numbers of high quality parasitoids (Chambers Reference Chambers1977; Gandolfi et al. Reference Gandolfi, Mattiacci and Dorn2003).

An environmentally friendly and sustainable plant protection programme incorporates biological control agents, including pathogens, parasitoids, or predators (Burges Reference Burges1981). Entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) such as Metarhizium anisopliae (Metchnikoff) Sorokin (Clavicipitaceae), which are ubiquitous soil borne entomopathogens, have the potential to attack the host during its soil-based living stages. Metarhizium anisopliae has a broad host spectrum; it has been isolated from more than 200 insect species, mainly of the order Coleoptera (Samson et al. Reference Samson, Evans and Latge1988). Successful applications of EPF against different pest insects have been reported by (Ferron et al. Reference Ferron, Fargues and Riba1991; Butt Reference Butt2002). The fungus M. anisopliae (Ma) is also an effective biological agent for the control of both the larvae and adults of M. alternatus and other insects (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Huang and Liu2004). Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Piao, Wang, Shin, Chung and Shu2007) found that S. guani inoculated with Beauveria bassiana (Balsamo-Crivelli) Vuillemin (Clavicipitaceae) has been shown to have some additional effect on the larvae of M. alternatus (Shimazu et al. Reference Shimazu, Tsuchiya, Sato and Kushida1995). It is very difficult to transfer M. anisopliae to the larvae of M. alternatus within their galleries in pine sapwood. Scleroderma guani could be used as a vector of M. anisopliae to transfer and infect to the PSB larvae within their galleries. The objective of this study was to determine the efficacy of S. guani as a vector of M. anisopliae for the enhanced control of M. alternatus larvae and so prevent the emergence of adults of M. alternatus.

Materials and methods

Experimental insects and mass rearing of Scleroderma guani

The parasitoid S. guani was reared on larvae of M. alternatus collected from the Tianmuhu Forest Park, which is in Changzhou City, Jiangsu Province (31º31′44.38″N, 119º42′45.51″E). The larvae of PSB were stored individually in glass vials (4.5 cm in height×1.0 cm in diameter), capped with a cotton plug to prevent cannibalism. All mature PSB larvae were stored at 8–10 °C before be used in parasitoid rearing. Mass rearing was done with single larva of M. alternatus held separately in individual vials. Vials were inoculated with three to four females of S. guani and kept at 26±2 °C, 70% relative humidity, under a light-dark cycle of 14:10 hours. From 2004 to 2013, 15 million adult females of S. guani were produced annually using 0.3 million of larvae of M. alternatus as host. All of the male adults died after mating with female adults of S. guani. Fifteen million adult females were stored in a cold room (at a temperature of 6±2 °C) until their release in mid-July (Xu Reference Xu2008; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Xu, Xie, Zhang., Shin and Cheong2008).

The virulence bioassay of Metarhizium anisopliae (Ma) strains to Monochamus alternatus larvae

Twenty-one strains of Ma from several sources (Table 1) were cultured on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium for 15 days at 25 °C for comparing sporulation. The numbers of spores were counted with a haemocytometer. Each of the four best sporulating strains of Ma was cultured at 20 °C, 25 °C, 30 °C, 35 °C, and 40 °C at 70% relative humidity for 18 hours and under a light-dark cycle of 14:10 hours to compare conidia germination. Five replicates of 100 conidia of each strain of Ma were used to assess conidia germination.

Table 1 Source of strains of Metarhizium anisopliae (Ma)Footnote *

* Most sources of strains of M. anisopliae for this experiment were provided by Piao Chungen, Chinese Academy of Forestry and Li Zenzhi, Anhui Agriculture University.

Suspensions of the four best sporulating Ma strains of the spore concentration was determined with a haemocytometer and diluted to the concentration of 1×108 spores/mL with sterile water (Pilz et al., Reference Pilz, Enkerli, Wegensteiner and Keller2011). Individual PSB larvae were inoculated by spraying 100 µL of suspension into each tube. Thirty PSB larvae in each of five replicates were inoculated with the suspensions of each of the four strains. Larvae in the control group were treated with sterile water. Mortality of larvae was scored daily. Lethal concentration 50 (LT50) (days) were computed for each strain. The best strain was further evaluated by a serial dilution series, 1.0×108, 1.0×107, 1.0×106, 1.0×105 spores/mL, with sterile water as a control, to determine the LC50 for the M. anisopliae with 30 larvae in five replicates for each dilution treatment. Monochamus alternatus larvae were incubated at in 26±2 °C and 75% relative humidity. The mortality was recorded daily. Regression analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois, United States of America).

Use of Scleroderma guani as a vector of Metarhizium anisopliae to larva of Monochamus alternatus

The female Scleroderma guani used as vectors for Ma789 were sprayed with a 1×108 suspension of M. anisopliae strain 789 (Ma789) and allowed to dry for one minute before being transferred to a PSB larva. There were three levels of treatment with either 1, 2, or 3 S. guani inoculated with Ma added to individually PSB larva in its vial, which was closed with a cotton plug. Each treatment consisted of five replicates each with 15 PSB larvae. A parallel series of treatments was set up for non-inoculated S. guani. The experiments were conducted at 26±1 °C and 75% relative humidity. Numbers of parasitoids and dead PSB larvae were recorded daily for up to two weeks. Mortality data was evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Results

Bioassay of different strains Metarhizium anisopliae (Ma)

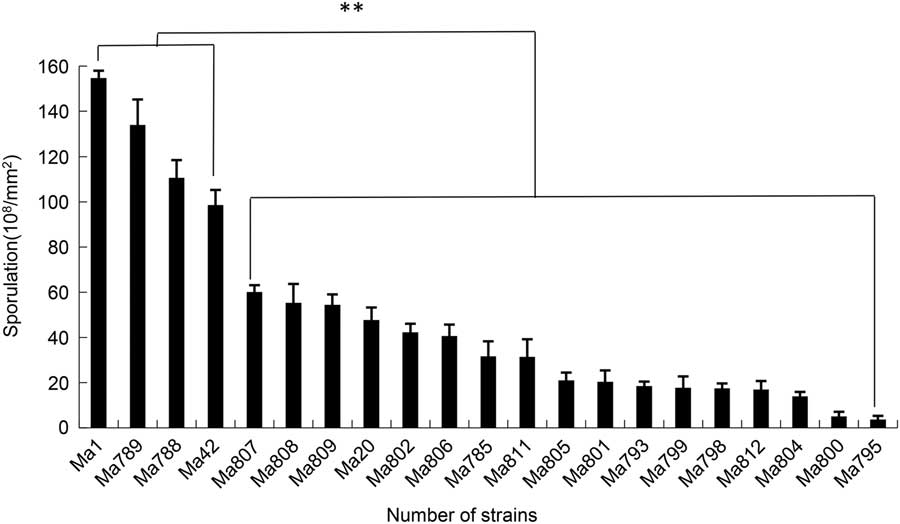

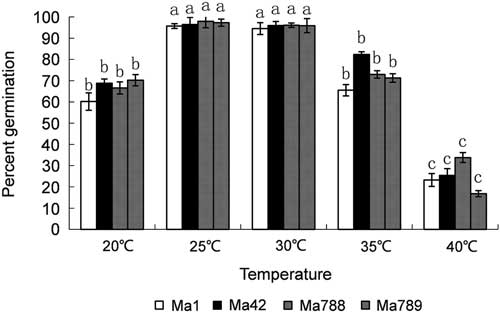

The spore production levels of the 21 strains of M. anisopliae on PDA medium are shown in Fig. 1. Ma1 had the highest sporulation rate, followed by Ma789, Ma788, and Ma42 and showed significant differences among 21 strains of M. anisopliae by Duncan’s multiple range test (α=0.01). These four strains had significantly higher sporulation levels than that of other strains tested (Duncan’s multiple range test, α=0.01). When these four strains of M. anisopliae were tested across a range of temperatures the test results showed that they all germinated best at 25 °C and 30 °C. Germination was lower at 20 °C and 35 °C and poorest at 40 °C (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 The sporulation of 21 strains of Metarhizium anisopliae on medium. Significant differences were detected by Duncan’s multiple range test, α=0.01.

Fig. 2 Effect of temperature on conidial germination of four Metarhizium anisopliae strains. The data are mean±SE. Significantly differences were detected among the four strains by Duncan’s multiple range test, α=0.01.

The virulence bioassay of Metarhizium anisopliae (Ma) strains to Monochamus alternatus larvae

The virulence bioassay test results among from the four best sporulating strains (Table 2) demonstrate that Ma789 was the most virulent strain on the larvae of M. alternatus. The LT50 for Ma789 was 11.51±0.97 days, followed by Ma42 and Ma1, with LT50s of 11.75±1.17 and 11.79±0.58 days, respectively. Ma788 was a relatively weak strain, its LT50 was 12.43±1.85 days. The mortality of the strains Ma789, Ma42, Ma1, and Ma788 on PSB larvae were 83.3±1.27%, 80.0±1.82%, 76.7±3.23%, and 73.3±0.86%, respectively, after two weeks (Table 2).

Table 2 Bioassay of the virulence of four strains of Metarhizium anisopliae against the larva of Monochamus alternatus Footnote *

* The data are mean±SE; lowercase superscripts indicate significant differences, Tukey test, P<0.01. LT50/day is the day that 50% of the larvae of M. alternatus were killed by the strains of M. anisopliae.

In the dilutions series bioassays of Ma789 the LT50s of M. alternatus larvae were 20.61±2.24, 13.38±1.69, 11.53±0.67, and 8.17±1.13 days at spores concentrations of 1.0×105, 1.0×106, 1.0×107, and 1.0×108 spores/mL, respectively. The LC50 of Ma789 to the larva of M. alternatus was 2.9×105 spores/mL (Table 3).

Table 3 The effect of spore concentration of strain Ma789 on mortality of Monochamus alternatus larvaeFootnote *

* The data are mean±SE; lowercase superscripts indicate significant differences, Tukey test, P<0.01. LT50/day is the day that 50% of the larvae of M. alternatus are killed by the strains of M. anisopliae. LC50 is the concentration when 50% of the larvae of M. alternatus are killed by the strains of M. anisopliae.

Use of Scleroderma guani as a vector of Metarhizium anisopliae to larva of Monochamus alternatus

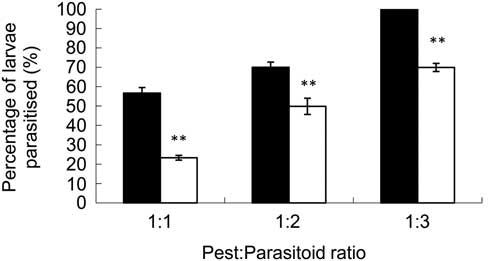

When S. guani is introduced into a PSB vial, the first two days are spent paralysing the PSB larvae and depositing its eggs. During this time there are no noticeable differences of any mortality of the PSB larvae between the S. guani inoculated with Ma789 and the non-inoculated S. guani. One week later, PSB larvae from treatments containing S. guani inoculated with Ma789 showed M. anisopliae infection symptoms that increased over time. There were significantly more PSB larvae killed by Ma789-inoculated S. guani at each level of inoculation (t-tests, P<0.01). When the PSB larvae to Ma789-inoculated parasitoid ratios increased from 1:1 to 1:2 to 1:3 mortality rates increased significantly (Fig. 3) with 100% of PSB killed at the highest treatment level where each PSB larvae had three Ma789-inoculated S. guani. For the inoculated S. guani, F(2,12)=285.8, P<0.001, for the non-inoculated S. guani, F(2,12)=205.8, P<0.001, both series showing significantly greater mortality with increasing ratio of S. guani.

Fig. 3 Percentage of Monochamus alternatus larvae parasitised by Sclerodema guani carrying Ma789 compared with percentage parasitism by S. guani alone. Dark bars are the parasitoid with Metarhizium anisopliae; white bars are for Scleroderma guani alone. The data are mean±SE. Within each ratio, the means are significantly different; t-tests, P<0.01. Mortality data was evaluated by one-way ANOVA showing significant differences when the parasitoid ratios increased from 1:1 to 1:2 to 1:3 mortality rates increased significantly.

Discussion

Metarhizium anisopliae, formerly known as Entomophthora anisopliae (basionym), is a fungus that grows naturally in soils throughout the world and causes disease in various insects. Ilya I. Mechnikov named it after the insect species it was originally isolated from: the beetle Anisoplia austriaca (Herbst) (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). It is a mitosporic fungus with asexual reproduction, which was formerly classified in the form class Hyphomycetes of the form phylum Deuteromycota (Cloyd Reference Cloyd1999). Previous bioassays of seven strains of M. anisopliae to control M. alternatus adults tests were shown to be effective (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Huang and Liu2004). Other experiments reported using different methods for using M. anisopliae on non-woven fabrics and attractants to control the adults of Spondylis buprestoides (Xia et al. Reference Xia, Dind and Liu2005). The virulence of M. anisopliae to the adults of M. alternatus was conducted effectively through the tarsal immersion method (He et al. Reference He, Chen and Huang2005). Our test results showed that the virulence bioassays of four selected strains of M. anisopliae (Ma1, Ma42, Ma788, Ma789) were strongly toxic to the larva of M. alternatus. The virulence test comparing the four selected strains of M. anisopliae showed Ma789 to be the most infective after two weeks. Virulence bioassay results showed the Ma789 strain of M. anisopliae to be the most effective strain for controlling M. alternatus larvae. This strain may have the potential to control other woodborer insects.

Observations of S. guani parasitising the larva of M. alternatus revealed that when a larger PSB larva was stung by the adult of S. guani, the PSB larva reacted strongly, which sometimes killed the adult of S. guani. This larval defence behaviour reduced the rate of parasitoid-caused mortality of the larva of M. alternatus from S. guani. Increasing the ratio of S. guani adults increases the chances of successful parasitism.

Adults of S. guani have also been shown to be able to transfer B. bassiana for controlling PSBs. Test results showed that in large areas of pine forest 80% of the M. alternatus larvae can be parasitised by S. guani and B. bassiana. This rate of control is much higher than that achieved by using either S. guani or B. bassiana alone (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Piao, Wang, Shin, Chung and Shu2007). It has been suggested that S. guani as an ectoparasitoid could transfer B. bassiana for controlling PSB larvae. Our research demonstrated that S. guani inoculated with M. anisopliae spores successfully vectored the fungus to M. alternatus larvae in vitro. The addition of the Ma789 inoculum demonstrated a significant gain in PSB mortality with 100% obtained with the ratio of 1 PSB larvae: 3 Ma789-inoculated S. guani. As M. anisopliae cannot reach the larva of M. alternatus in the PSB larval galleries directly, S. guani not only is a parasitoid natural enemy of the larva of M. alternatus (Samson et al. Reference Samson, Evans and Latge1988; Xu Reference Xu2008; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Xu, Xie, Zhang., Shin and Cheong2008), but is also a vector of Ma789. Therefore, S. guani carrying Ma789 could be a significantly enhanced strategy for controlling the larvae of M. alternatus.

On the other hand, what effect does M. anisopliae have on S. guani? It is very difficult to transfer M. anisopliae into the PSB larval galleries without a vector. While the control potential Ma789 inoculated S. guani on PSB larvae has been demonstrated by our test results, it remains to be determined what effect, if any, the levels of M. anisopliae used in our tests might have on the S. guani parasitoid itself.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers, for their insightful comments. Thanks are extended to Professor Emeritus Dr. John McLean of the University of British Columbia Department of Forest Sciences for contributing his time and energy in revising the manuscript. This research was supported by the Foundation Public welfare projects of State Forestry Administration of China Grant number 201004072. They thank Dr. Piao Chungen, Chinese Academy of Forestry and Prof. Li Zenzhi, Anhui Agriculture University who provided most of the strains of M. anisopliae (Ma) for this experiment.