Advance directives enable individuals to project their healthcare preferences into a period of anticipated incapacity. With advance directives, individuals can designate whom they would like to have make healthcare decisions for them (proxy directives), or give their healthcare provider advice on what to do (instructional directives), or both. Canada has an unusually wide variety of legislative approaches to advance directives. In what follows we describe and evaluate these, with the aim of pointing the way toward the ideally best legislation and policies on such directives.

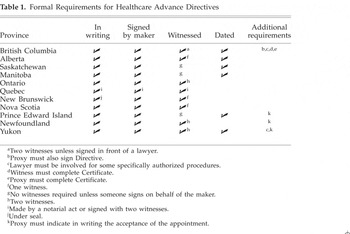

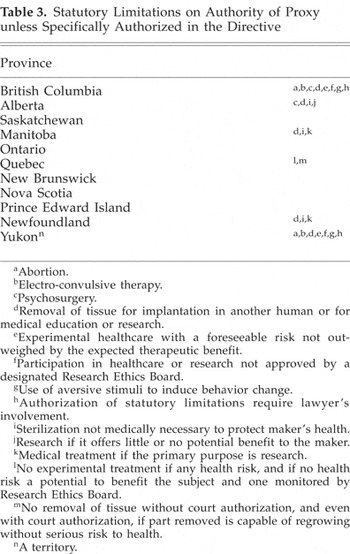

In Canada, legislation on advance directives falls under provincial jurisdiction. There are 11 approaches to advance directives in Canada, corresponding to the 10 provinces and one territory that have legislation in this area. Some are very similar, some are not (Nova Scotia legislation, for example, only gives legal effect to proxy directives). But they all either provide for both proxy and instructional directives or expressly or implictly allow for instructions (some jurisdictions require the proxy to implement any instructions). The principal features of these approaches are summarized in the Tables 1, 2, and 3.

Formal Requirements for Healthcare Advance Directives

Minimum Age for Maker and Proxy

Statutory Limitations on Authority of Proxy unless Specifically Authorized in the Directive

Turning to evaluation, there can be no serious question that making legal provisions for proxy and instructional directives is a good thing. The main issues about advance directives are over how the legislation should be written, and whether there should be a policy to encourage all persons to have advance directives in their life planning. The issues under these heads are extremely complex, and the best we can do here is to state our conclusions with just enough rationale to indicate how we think a full justification of them would proceed. We take the two issues at contention in order.

There are five questions about how advance directive legislation should be drafted. As Tables 1, 2, and 3 indicate, these concern age requirements, the formal requirements of dating and witnessing, the involvement of lawyers, and statutory limitations on the authority of proxies to make decisions.

Age is used in law to draw the line between who can vote, buy alcohol, apply for a driver's license, and so on. But there is nothing intrinsically important about age. It gets its relevance only as a rough index of when appropriate understanding and judgment can be supposed to phase in. When testing directly for those abilities would present administrative difficulties, and no great burdens are put on individuals by having to wait to meet the age requirement, age-based restrictions can be justified on the basis of utility. But in the case of advance directives, neither of these conditions applies. The cases in which young people want to make advance directives will be few and far between and will be limited to situations about which it is very important for individuals to have a say. It thus seems best, as Manitoba and Newfoundland do, to let capable people of whatever age make decisions for themselves.

Dating is important only if we are prepared to specify an expiry date, after which an advance directive is invalid, or a best before date, after which one can take liberties in reading the directive. It is not, however, clear on what principle one could do this, let alone how to go about assigning actual numbers. Dating requirements presuppose that old advance directives are less reliable than recent ones, but that is problematic. It must be assumed that people who go to the trouble of making advance directives have strong feelings about their future healthcare and believe that advance directives are effective instruments to achieve their aims. It strains credibility to suppose that such persons would change their views but nonetheless keep a directive that now does not reflect their wishes. That, however, is exactly what we are invited to think by a dating requirement. Dating thus seems irrelevant, as Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland treat it.

Requiring witnesses is presumably designed to protect against fraud. Fraud will not be foiled, however, unless witnesses certify in front of a lawyer or are contacted before an advance directive is acted on. But legislation frequently requires witnesses without stipulating either of these conditions, and they cannot be stipulated without considerable bureaucratic encumbrance or impairing the effectiveness of directives. Cheers, thus, to Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Prince Edward Island, who do not have this requirement.

Requiring the involvement of lawyers, by contrast, does provide some security against fraud. It may also help individuals make more thoughtful decisions (though if that is the aim, it is odd to require consultation with lawyers but not healthcare providers, who promise to be even more helpful). These advantages, however, like requiring witnesses, come at the cost of putting clear and substantial obstacles in the way of individuals determining their healthcare when incompetent. Only great risks can justify such impediments, and such risks do not seem to be present. The possibility of tragedies arising from inadequate safeguards has to be weighed against the certain knowledge that the safeguards will discriminate against the poor and ill informed and will generally deter people from making advance directives. Thus boos to the Yukon and British Columbia, who make consultation with a lawyer mandatory for some advance directives.

Should statutory limitations be put on the authority of proxies? The authority of proxies has never been absolute. It is limited in two ways. First, like patients themselves, proxies cannot demand treatment that healthcare providers deem inappropriate. Thus any treatment that is provided comes with the concurrence of medical opinion. Second, unlike competent patients, proxies cannot refuse treatment for any reasons, but must act on the values and beliefs of those they represent. These values and beliefs encompass those that are peculiar to the patient, such as being a Jehovah's Witness, and those that the patient can be presumed to have as a reasonable person, such as wanting necessary blood products if one is not a Jehovah's Witness.

With these understandings in place, the question is whether any additional limitations should be put on proxies. We think not. The restrictions (which generally can be overcome with specific provisions in the proxy and sometimes a lawyer's involvement) that we find some provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Quebec, and Newfoundland) imposing give evidence of special-interest lobbies and divide into two kinds. Some, such as those that prohibit the delivery of electro-convulsive therapy, psychosurgery, and risky nontherapeutic interventions on the authority of proxies, are included under the first of the above limitations on the authority of proxies. Others, such as those that deny proxies the authority to consent to abortions or refuse life-preserving treatment, either try to impose moralistic or paternalistic views by making these decisions medical ones or add nothing to the general requirement of having to act in accordance with the values and beliefs of the patient. Individuals should be free to put whatever restrictions they want on proxies, but we think it would make for better law to have restrictions as the exception rather than the rule. The point of designating a proxy in an advance directive is to identify the person you want to make your decisions. The natural understanding of this is that, as long as the proxy acts in accordance with your known or presumed values and beliefs, the proxy should be unfettered unless specifically restricted, just as half the provinces have it.

We now turn to the question of public policy. Only 10% of Canadians have completed an advance directive.1

Singer PA, Robertson G, Roy DJ. Advance care planning. In: Singer PA, ed. Bioethics at the Bedside. Ottawa: Canadian Medical Association; 1998:41.

See note 1, Singer et al. 1998:41. Also, Fagerlin A, Schneider CE. Enough: The failure of the living will. Hastings Center Report 2004;34(2):30–42 at p.38.

There are risks to all advance directives. Proxy directives pose the risk of conflict of interest. The nearest and dearest can stand to profit most from the patient's death. Proxies may also, from a variety of motives, decide not to act on the maker's wishes. But the greatest risks come with instructional directives. Instructional directives can be very useful if patients are chronically or terminally ill, have visible disabilities and fear that physicians may not provide maximal treatment, or have special views such as Jehovah's Witnesses do. But most may not be well served by such a directive. The interventions that one would want in the event of a medical crisis depend on the effects the patient has suffered; the extent, probability, and speed of their reversibility; and the burdensomeness of care. Instructional directives that specify what procedures one wants under what contingencies3

This is the approach taken by the University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics Living Will, available at the Centre's Web site at www.utoronto.ca/jcb, and Molloy W, Mepham V. Let Me Decide: The Health-Care Directive That Speaks for You When You Can't. Toronto: Penguin Books; 1996.

For an example of such an approach see Browne A, Sullivan WJ. Advance directives: A third option. Annals of the Royal College of the Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) 1999;32(6):352–4.

See note 2, Fagerlin, Schneider 2004:34.

There is thus no justification for encouraging everyone to have an advance directive. In Canada, individual healthcare providers, local hospitals, medical schools, nursing schools, and health regions sometimes do encourage this. But there is no official encouragement for such advance planning. There is no Patient Self-Determination Act, and neither the Canadian Medical Association, nor the Canadian Nurses Association, nor any other significant body urges them on the public. This is a good thing, and a situation that some commentators argue that other countries (such as the United States) should return to.6

See note 2, Fagerlin, Schneider 2004:30–42, especially 30–1, 41–2.