Hills peep o'er hills, and Alps on Alps arise!

PopeThere is reason to doubt whether La sonnambula is a pastoral opera. That doubt does not come from the archive: there we find only unity of opinion, beginning with the work's earliest critics. Bellini deserves praise for his handling of ‘una scena pastorale’, wrote one; the score is suffused with ‘una tinta di pastorale melodia’, another.Footnote 1 Carlo Ritorni called the whole a chimera, though there was no point in disputing that it was simple, tender, pastoral.Footnote 2 George Eliot slipped an allusion to the tenor's aria into The Mill on the Floss, thereby reinforcing the pastoral mood of one work with reference to another.Footnote 3 The consensus continues all the way up until this day, with Julian Budden, Elizabeth Forbes, Simon Maguire, John Rosselli and Mary Ann Smart all doing their bit to affirm La sonnambula's pastoral character.Footnote 4 Critics, whether they derive their authority from reputation or from historical proximity to Bellini himself, are of course not infallible, but anyone who turns to the opera must confess that setting and subject matter make disagreement all but impossible. The village is Alpine, the characters rustic. All the earth is in bloom, the heroine tells us. The meadows, undisguised luoghi ameni, resound with song and the preparations for the wedding feast. Dramatic tension arises from a single pebble – suspected infidelity – dropped into the pool; but those ripples are easily calmed, the placid harmony restored.

For the preceding writers, there is nothing to discuss. The pastoralism of La sonnambula is a matter of fact. If the task is to explain rather than to assert, however, confidence in the label might waver. A sleepwalking Swiss girl and a handful of fine melodies – where, exactly, does the pastoralism lie? Glancing over a few hundred years of writing on the pastoral reveals only contradiction and confusion. Definitions are numerous, which seems only fitting considering that ‘pastoral’ is applied freely to vast swaths of art from antiquity to the present. The idylls of Theocritus, Hardy's novels, Frost's poetry, the landscapes of Claude, Scarlatti's cantatas, Mozart's comedies, symphonies from Beethoven to Vaughan Williams: pastoral applies to one and to all. In literature it is a mode, a ‘broad and flexible category’ uncontained by the limits of a single genre.Footnote 5 In music it is a topic, a tradition that ‘encompasses the whole of the notated repertoire’.Footnote 6 For some, pastoral refers exclusively to depictions of the lives of shepherds; for others, it is a catchall for anything naïve, simplistic and superficial, where landscapes are idealised and the sufferings of the world irresponsibly avoided. The pastoral garden gives shelter to both prelapsarian innocents and sexual hedonists. It is a term of abuse and a term of praise. The nature of opera – that it depends on the cooperation of all the arts – challenges us to hold these definitions in balance. Is the pastoral in La sonnambula to be found primarily in the gentle arc of its plot? Or is it confined to the setting, painted stage hangings showing mill and mountain pine? Is there a single page in the score that could dispel all uncertainty?

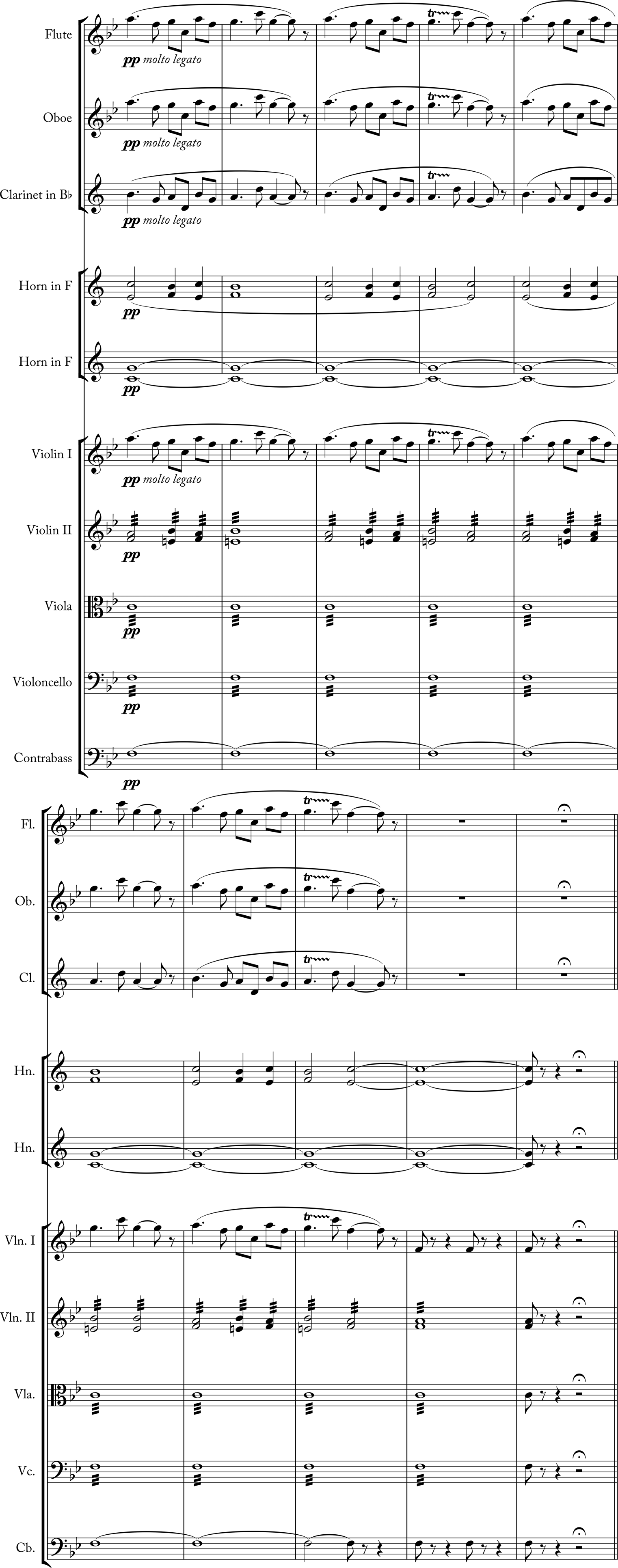

For Emanuele Senici, the most important writer on La sonnambula in recent years, the answer to this last question is an emphatic no. Only once does a shepherd step forward to address his flock upon the mountainside; only once does Bellini signal any interest in the pastoral. Indeed, despite the subject matter, the composer refused to ‘take full advantage of the devices traditionally used to create an Alpine ambience’.Footnote 7 In the early nineteenth century it was the high meadows of Switzerland, Senici demonstrates, that substituted for the once generic locus amoenus of classical poetry, and thus to refuse an Alpine ambience is to refuse a pastoral one.Footnote 8 Other authors in other ages may have chosen Arcady or Arden for the location of their retreats, but for the romantics it was the Alps, with all their purity and indifference to man, that would become the ‘“sentimental” version of classical Arcadia’, an appropriate habitat for the virginal songbirds of La sonnambula and Linda di Chamounix.Footnote 9 Senici turns to old topical associations to show how music might create a sense of place; that ‘all we find in the score is a simple horn call whose last two chords are echoed’ is therefore evidence of the composer's repudiation of setting and mood (Example 1).

Example 1. Bellini, La sonnambula, from Act I, no. 5 Recitativo e coro.

No early critic identified specific moments as pastoral, and thus we cannot be sure whether these horn calls alone were enough to lend the opera that ‘tincture of pastoral melody’. Regardless, identifying a few isolated invocations of the ranz des vaches does not begin to account for the opera's distinct and pervasive atmosphere. Commentators historical and modern have long identified the new direction Bellini took with La sonnambula, a marked retreat from the austere declamatory style of Il pirata or La straniera, often dubbing it a disappointing ‘rapprochement’ with the florid excesses of Rossini.Footnote 10 Whether or not this flight from what might be called a stance of melodic realism relates to the pastoral setting of La sonnambula is difficult to say, because a handful of discrete musical examples cannot capture the evenness and serenity that characterise so much of this score. For to listen to the opera is to be always half-conscious of some pattern hanging in the sky, such that without referring any few bars to a special place, they have that meaning that comes from their being parts of a whole design, and not an isolated fragment of unrelated loveliness.Footnote 11

It is that design, this article argues, that gives La sonnambula its pastoral character – far more than its libretto or occasional uses of local colour. To enter Bellini's pastoral world, to see how an Italian opera premiered in 1831 may have subsumed 2,000 years of literary convention, is no easy task. In part, this is a problem of methodology. Questions of genre and style are only partially answerable through recourse to the archive, and no certainties about the extent to which the pastoral is a meaningful category for Bellini's opera will emerge from the reconstruction of an operatic experience from a handful of newspaper clippings alongside translations of the Eclogues. Historicism, for some years now the dominant approach in opera studies, has its limits. La sonnambula does not exist in the past alone, and this article insists that great rewards can be found in a sympathetic hearing of the opera as it appears to us today. Examining Bellini's self-conscious treatment of musical formulas, for example, reveals much about historical and contemporary ideas of closure, pacing, genre and the pleasures that can be found in musical and literary convention. This article explores ways to write about such large-scale effects. At times it is an experiment in description, in ways to capture something of an opera's gestalt, which is so often ill-served by analytical systems and a narrow selection of musical examples. Talk of the pastoral invokes those dangers that come with importing terms from other disciplines, though this article argues that there is some truth in the resemblances that strike us across music and literature, even if they appear superficial and fleeting when held up to scrutiny.

False pastoral

Then shall I dare these real ills to hide

In tinsel trappings of poetic pride?

CrabbeOne convention of writing on La sonnambula is to begin with an apology, to acknowledge the gap between the world of the work and today, when – it is assumed – audiences are no longer willing to spend an evening listening to some maiden in a flowered apron fret about her chastity. ‘It is hard to take [the opera] seriously nowadays’, says Senici.Footnote 12 For Rosselli it is a matter of faith, for La sonnambula can only be understood properly ‘if the conductor and players believe in the work’.Footnote 13 Such statements are themselves pastoral, if the term is allowed its elegiac connotations, a longing for a time when the relationship between the opera and its audiences was less disquieting than it is today.

There is a long and distinguished history of not taking pastoral works seriously; readers and listeners ‘nowadays’ are hardly the first to look upon the merrymaking of shepherds with some distaste. Pages of testimony could be called upon to demonstrate this fact, though Samuel Johnson's comments on ‘Lycidas’ are perhaps the most famous. For him, the form of the pastoral was ‘easy, vulgar, and therefore disgusting: whatever images it can supply are long ago exhausted; and its inherent improbability always forces dissatisfaction on the mind’.Footnote 14 For many critics, that ‘long ago’ was Virgil, and attempts to revive the myth in the intervening centuries have produced a raft of mediocre parodies. Schiller is equally famous for his dismissal of the pastoral, writing in On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry about the ‘inherent defect of idyllic poems’ that results from the oversimplification of human nature and the repudiation of all art.Footnote 15 The opinion, if we can believe the papers, was shared by many Italians in 1831:

The Arcadians, with their mawkish lovers, those coy nicknames such as Tirsi, Elpino, Amarilli, Dori, and Nice, have made the poetry called bucolic or pastoral distasteful in the eyes of Italians. … Indeed, if we decided to go rummaging about in the poems of this kind written in our age, we would find nothing worthy of particular mention.Footnote 16

If La sonnambula is indeed pastoral – and therefore a repository of clichés – it is easy to see how it was read as stylistically regressive by those who favoured the ‘philosophical’ style of Bellini's earlier operas.

Those sympathetic to pastoral works have found many ways to step outside this tradition of censure and dismissal. ‘The characteristic way’, according to Paul Alpers, ‘is to claim that [the pastoral] undermines or criticizes or transcends itself.’Footnote 17 Senici may insist that he takes La sonnambula seriously both historically and aesthetically, but for him this involves an ‘interpretation of the relationship between the two main characters … as less idyllic and idealised than critics have suggested’.Footnote 18 Less idyllic – is it not disappointing that taking La sonnambula seriously involves denying one of its most agreeable qualities? But it was Bellini who had little interest in pastoral landscapes, according to Senici, Bellini who was reluctant ‘to give the audience musical clues sufficient to allow them to determine where the action takes place’.Footnote 19 The point is reiterated multiple times, though here the eye is tempted to linger over the word ‘sufficient’. Once – the shepherd's call cited earlier – is evidently not enough, but it would be difficult to say just how many times a horn must send an echo down the valley to ensure no one forgets that we are in the Alps. This is not the only instance of idyllic colour, however, for Bellini does provide a rival moment of indisputable alpine pastoralism: during the second, climactic sleepwalking scene, Amina's safe arrival over the mill wheel – she has been treading perilously on a beam, the opera's most iconic moment – is welcomed with a song of thanksgiving that would not be out of place in any pastoral symphony (Example 2). The classic signifiers hold court uninterruptedly for eight bars: string and horn sustain the tonic and fifth, while all other voices play the alpine melody in unison. The tune is both novel and generic; it appears nowhere else in the opera, but it contains no artifice of composition. The listener must accept it for what it is, complete in itself; there is nothing to develop or fragment, so it can only be repeated.Footnote 20 Rosselli, curiously, says the horns ‘take over’ at this point, but their warmth is enlisted primarily to lend some colour, even if the melody itself may sound as if it were taken from them.Footnote 21

Example 2. Bellini, La sonnambula, from Act II, no. 12 Scena ed aria finale.

Perhaps it is because the horns are denied a more prominent role in this scene that Senici does not hear it as unambiguously alpine – timbral and melodic associations have been temporarily sundered. Topics, however, are flexible. Their viability is derived in part from being identifiable outside their original social function: it is said, to summon one famous example, that we are meant to smile upon hearing the beginning of Haydn's Symphony No. 6 ‘Le matin’, recognising that the signal of dawn associated with the horn has been gifted to the flute. Senici cites the shepherd's song in Paisiello's Nina as an important precedent for the pastoral in La sonnambula, which suggests that such licence was no longer possible in 1831. Topics that once roamed freely across symphonies and sonatas have returned to Italian opera as local colour and realism. If the pastoral is confined to the shepherd's pipes, then Bellini ‘refused’ to exploit the opportunities for local colour that Rossini had splashed across Guillaume Tell.Footnote 22

But if timbre, melody and even rhythm are allowed to speak independently of each other, then there is no shortage of musical evidence for the pastoral throughout La sonnambula, beginning with its opening bars. The start of the opera is announced with a horn fanfare (Example 3a), pure timbre and rhythm – 6/8, of course – bereft of any melodic contour. When the curtain rises, this gesture is handed to the banda onstage, which echoes its first blast after one bar of silence, evidently the amount of time it takes for the call to make it down the glen and back (Example 3b). A more traditional operatic depiction of landscape cannot be imagined. If anyone doubted what these short flourishes and the subsequent melody were supposed to mean, the libretto offers a helpful reminder: simply and unequivocally, La sonnambula opens with a series of ‘suoni pastorali’. Describing the chorus that follows presents some challenges, for the selection of the appropriate adjective risks confusing assertion for observation: that the melody is repetitive, that the text, with all its la-la-la-las, reminds us of the natural songs of childhood, conjures up words such as ‘rustic’, ‘jaunty’, even ‘naïve’. Surprisingly, some commentators hear no ‘prominent echo effects’ and insist that the whole of the introduzione is ‘conventional’, perhaps ‘external to the intimate substance of the work’.Footnote 23 To invoke the pejorative overtones of convention is to repeat the old slur against both pastoral poetry and early nineteenth-century Italian music, forgetting, perhaps, that the pastoral depends on convention, on convening, often for the pleasures of song.Footnote 24 Whatever the quality of the melody that closes the introduzione (‘In Elvezia non v'ha rosa’), to begin a work with a farmer's diegetic song is to invoke convention with purpose, to place the opera squarely within the tradition of literary pastoral.

Example 3a. Bellini, La sonnambula, from Act I, no. 1 Coro d'Introduzione.

None of these observations necessarily contradicts Senici's sympathetic reading of the opera, but we nevertheless sense that his interest in the geographic specificity of the Alps leads him to overemphasise what La sonnambula is not. The Alpine setting may have been only incidental, a nod to fashion in a work that seems more interested in recalling the pastoral conventions of the previous century than leading us to the sublime. And yet, Senici's reluctance to couple the opening horn fanfare with the shepherd's call later in the act plants a seed of doubt, and we begin to question the ease with which ‘pastoral’ could adhere to any page in the score. It can be difficult to judge, in other words, at what point a horn call ceases to be pastoral (or to partake of its sister topic, the hunt) and returns simply to being a horn. If the pastoral is to mean anything at all, we must attempt to get to the heart of this term's relation to music, to find some clarity amid its promiscuous usage across musicology and music theory.

What is (musically) pastoral?

In his analysis of the various topoi crowding the first movement of Mozart's String Quintet in C major KV 515, Kofi Agawu makes a curious distinction: at one moment we are meant to hear the pastoral, at other moments the assembled musicians pipe a musette.Footnote 25 The comparison seems curious, like distinguishing between rectangles and squares, red fruits and pomegranates. Surely all musettes are pastoral, though Agawu and other theorists seem to agree that some music can be pastoral without the characteristic effects of the musette. In other words, some vision of Arcadia is possible that does not feature a lone shepherd droning and tootling upon the hillside.

Agawu's first moment of pastoral appears in bars 38–41 (Example 4a), and it is easy to see why this is unlike the musette that begins in bar 86 (Example 4b): no pedal point, no bagpipe, no shepherd. What, then, is characteristically pastoral about it? Its simplicity, perhaps – the shift in texture that throws all attention on the top voice, which merely outlines and then decorates the triad while the supporting voices drift between tonic and subdominant, harmonic bedfellows because of the importance of their shared scale degree. Nothing much happens (the tonic C is sustained by the second viola throughout), but evidently there is still enough harmonic motion to disqualify these bars as a musette.

Example 3b. Bellini, La sonnambula, from Act I, no. 1 Coro d'Introduzione.

Example 4a. Mozart, String Quartet in C major, KV 515 (1. Allegro), bb. 38–41.

Confusion about the musical pastoral arises from its strangeness as a topic, even though it seldom stands apart from its peers. In Wye Jamison Allanbrook's alphabetically arranged universe of topics, for example, it sits unassumingly between ‘passepied’ and ‘pathetic’.Footnote 26 Its singularity becomes apparent, however, upon leafing through Raymond Monelle's classic The Musical Topic, a book organised around the three central topoi of late eighteenth-century music: the hunt, the military and the pastoral.Footnote 27 Monelle begins each section with a history of the topic in question, before pointing to representative quotations in the repertory. For the hunt, he tells of the development of the horn and the various calls that echoed through the woods of Fontainebleau during the reign of Louis XIV. The history of military music is one of marches, piccolos, the drumming of the tattoo and everything else meant to excite both soldier and citizen with war's alarms. The origins of the pastoral, by contrast, are not to be found in shared social practices or the evolution of instruments. With the pastoral, attention turns to literature, and if its history – whether narrated by Monelle or anyone elseFootnote 28 – is going to be discussed at all (rather than cited as something self-evident), the reader is reminded of Theocritus and Virgil, Spenser and Shakespeare, and all those innumerable poets who spun out stories of nymphs and satyrs and shepherds who drank from the cup of Bacchus and filled their afternoons with song. We may have records of actual horn calls and bugle calls that allow us to recognise them as topics in the rollicking symphonic world of Haydn, but we will never hear the melodies that Tityrus played beneath the beech tree at the opening of Eclogue I.

To invoke the pastoral in music, then, is to flirt with myth and metaphor, which perhaps explains the diversity of the term's use among scholars. For some it is the music typically assigned to shepherds in eighteenth-century opera and oratorio, the drone and siciliana of Handel or Rameau. For others, such as Agawu in the preceding example, it can apply to any moment of simple lyricism and harmonic stasis. The divide is hardly new, as a passing glance through an old dictionary reveals: for Peter Lichtenthal, writing in his Dizionario della musica just a few years before Bellini's first triumphs in Milan, pastoral refers to ‘a musical composition of simple and rustic (but delicate) character, usually in 6/8 with a moderate tempo’. This is the pastoral at its most easily identifiable, the musical imitation of the shepherd's pipes, however stylised, however far removed from the actual music making of the labouring poor. Undoubtedly the shepherds were not playing a baroque pifa when the angels brought them news of Christ's birth, but the custom is familiar enough that no one could claim to be bothered by the artifice of it all. Lichtenthal's definition is incomplete, however, for pastoral also has another, suspiciously imprecise meaning. He goes on to note that pastoral designates ‘any opera that represents some episode of idealised country life, in which every sentiment expressed bears the mark of rural simplicity and innocence’.Footnote 29 Here is the literary pastoral, the amorphous ‘mode’ that draws under one heading The Shepheardes Calender, the Aminta of Tasso, and opera after opera in which Orpheus strums his lyre while charmed beasts and white-handed nymphs gather in fields of asphodel. This definition of pastoral is far more expansive than its topical counterpart, at least insofar as it is relevant to music. How, exactly, might a sonata or symphony relate to Virgil's Arcady? Imprecision and metaphor – the perils of leaping between literature and music – has not discouraged many commentators, however.

The most basic narrative trajectory of any pastoral story proceeds from harmony, through rupture, to reconciliation. Because this narrative happens to correspond with the trajectory of almost every piece of tonal music, it is possible to catch a glimpse of the pastoral wherever one might turn. Robert Hatten, for example, draws Beethoven's Op. 101 into the world of the pastoral, by listening for a surface gleaming with a ‘graceful and gentle expressivity’ only momentarily disrupted by tragic outbursts.Footnote 30 Maynard Solomon goes so far as to label the beginning of the Eroica symphony as pastoral, until the C# of course.Footnote 31 For William Caplin, the pastoral, with its emphasis on root-position tonic stability, often characterises the start of movements or serves what he calls a ‘post-cadential’ function, filling lengthy codettas where the tonic is pleasurably reaffirmed over and over again.Footnote 32 In Eden, Hatten, Solomon and Caplin seem to suggest, no one ever thought to leave the initial tonic, and the pastoral begins to stand in for all music otherwise called classical.

The exalted claims made about Viennese classicism – that the works of Mozart and Beethoven are repositories of truth and beauty, that at their best they allow us to catch a glimpse of heroism, genius, the face of the divine – mean that when these commentators invoke the pastoral, they are in fact invoking the tradition of pastoral in its entirety: a mere 2,000 years of poetry, not to mention the work of critics from Sidney to Shelley to the distinguished lecturers of the past century who have taken up their pens for its defence or condemnation. Solomon turns to a gallery of tweeds for his reading of Beethoven's Op. 96, and even though William Empson, Frank Kermode and Renato Poggioli had few thoughts on how Virgil or Shakespeare or Wordsworth might relate to a violin sonata, Solomon does not hesitate to stride across vast domains of Western literature to say something about the cramped grove of tonal music that flourished for a few decades around 1800. The ‘Diabelli’ variations are pastoral, he tells us, the ‘utter indestructability’ of the theme attesting to the ‘unwearying tenacity of every individual’, offering a ‘token of assurance of a permanent place in the order of things’.Footnote 33 Other scholars have similar recourse to the mythic and universal, from Owen Jander's notorious reading of the ‘Scene by the Brook’ as a ‘prophetic’ conversation between the brook, the birds and the composer himself to Richard Will's historically sensitive yet nonetheless Miltonic interpretation of the Sixth Symphony as an essay in the manipulation of time – both idyllic and ‘real’ – that ‘dramatizes fundamentally human concerns about morality’.Footnote 34 Such attitudes were given popular expression in Disney's animation for Fantasia, which has taught generations of young people to associate the Pastoral symphony with the celestial lawns of Olympus rather than the humble meadows surrounding Vienna.

The point here is not necessarily to efface this picture of Beethoven hand-in-hand with the ancients, but rather to try to imagine how Bellini and his Italian contemporaries might be included in the image as well. If we follow these theorists, or anyone who insists that guileless harmony or elegiac lyricism is reminiscent of rural innocence, we are likely to spot Virgilian rustics peeping out in the most unexpected places: however fanciful the vision, it may be that the lament of Eclogue II, the pining of Corydon with his pipe hewn of ‘seven hemlock stalks’, sounded a bit like the cor anglais solo that opens the mad scene in Il pirata. Never mind searching for horn calls, for page after page of Bellini's music would be called pastoral if it were slipped into a sonata by a northern composer. Hatten considers the use of parallel thirds to be a pastoral gesture, thereby reminding his readers of every duet in Italian opera for at least a century and a half.Footnote 35 For this reason, perhaps, topic theory has made few inroads into Italian opera of the early nineteenth century: part of the appeal of drawing attention to surface gestures such as the pastoral is to make the sublime, the recondite and the canonical more humble and democratic, and some of that enchantment is surely lost when the subject is music already associated with convention and the popular.

Thinking of Beethoven alerts us to other challenges as well, and not all of them can be chalked up to the century of hero worship and myth making that followed his death. His sixth symphony was composed at a time when the understanding of pastoral was undergoing a radical shift, and many scholars take for granted that works written after 1800 bearing the name ‘pastoral’ are responses to the newly aestheticised and highly romantic view of ‘nature’. Seemingly with one stroke – guided, no doubt, by Haydn and his oratorios – the musettes of the eighteenth century were transformed into the sublime landscapes of the nineteenth, preparing the way for everything from Schubert's song cycles and Mendelssohn's Hebridean seascapes to the mountains, fjords, ice and snow of Grieg and Sibelius.

Senici claims that nineteenth-century interest in the Alps ‘built on the much older topos of the sentimentalised countryside’, though readers of Paul Alpers will wonder at this use of ‘much’.Footnote 36 ‘It is not self-evident’, Alpers avers, that nature and idyllic landscape, the Golden Age and its nostalgia, ‘are the defining features of pastoral’.Footnote 37 Emphasising nature over the lives of shepherds, he insists, is a distortion of Schiller and the romantics that has clouded understanding of Virgil and the pastoral revival of the English and Italian Renaissance. For an example of this distortion in music history, consider Berlioz's praise for the Pastoral symphony: although Theocritus and Virgil were ‘great in singing the praises of landscape beauty’, their works nonetheless ‘pale in significance when compared with this marvel of modern music’.Footnote 38 Beethoven is not only worthy of being placed alongside the ancients, but he even improves on them.

Given that Alpers, like many writers on pastoral literature, was more interested in reading the Eclogues and As You Like It than revisiting familiar histories of romantic nature worship, perhaps he should be left aside. After all, Bellini was a product of the nineteenth century, which should inspire any researcher to turn dutifully to the discourses on nature by Schiller and his contemporaries. Yet, the simple fact of writing about the 1820s and 1830s (especially in Italy) does not necessarily mean that romanticism is the topic at hand.Footnote 39 Outwardly, an opera such as La sonnambula may display many romantic features – sleepwalking, the Alps, a strong undercurrent of sexual repression – but with a libretto by arch-classicist Felice Romani, it is hardly surprising that the whole thing struck one reviewer as ‘worthy of Metastasio’.Footnote 40

It would be unwise to argue that national context and perspective matter a good deal when discussing pastoral music in the early nineteenth century – that what one tradition of criticism might believe appropriate to Beethoven and his acolytes simply does not apply to Bellini. Such a relativist approach unhelpfully reinforces a pastoral mythology about Bellini himself, the flaxen-haired Sicilian boy with a preternatural gift for song whose graceful melodies lie beyond the tools of language and traditional analysis. It also stiffens divisions between Germany and Italy, tacitly recognising that one school of composition aspires to the universal while the other is doomed to the provincial: Beethoven wrote for the gods, Bellini for the Scala. Though it can be difficult nowadays to make aesthetic judgements with any certainty, it does seem unjust to allow Beethoven his time with Virgil and Shakespeare and deny that opportunity to Bellini: is there not some truth that he might have to share with us as well?

Shepherds in the archive

Virgil and the pastoral tradition can be made relevant to Bellini, of course, but to draw the connection involves tired techniques of historicist recovery – asking what the pastoral meant for Italians in the 1830s, how reading the many new translations of the Eclogues might have shaped the operatic experience of hearing La sonnambula for the first time. The engraving that adorns the title page of one edition of La buccolica (as the Eclogues were sometimes known in Italian) offers some clues.Footnote 41 The cramped image shows mixed vegetation – a leafy oak tree stands before slopes of evergreen pine – and a pair of generically rustic (though far from classically inspired) buildings (Figure 1). In fact, the image is so generic that it is difficult not to spot resemblances between it and Alessandro Sanquirico's original stage designs for La sonnambula (Figure 2), which, because of their own free mixture of trees, leads Senici to argue once again that there is ‘some sort of ambivalence towards a fully-fledged Alpine ambience’.Footnote 42 He goes on to cite a moment in Act II scene 2 in which Amina reminisces about when she and Elvino would sit ‘under the shadow of beech trees’ (‘di questi faggi all'ombra’), further evidence that the opera fails to be as fully Alpine as one might wish.Footnote 43 True, beech trees may not belong in the Alps, but they do belong in Virgil: the first pages of La buccolica describe how Meliboeus first spies Tityrus seated in the ‘spazioso faggio all'ombra’.Footnote 44 The trees should not distract anyone from the shadows they cast, however, for numerous commentators have stressed the centrality of this shade, umbra, to Virgilian pastoral and the locus amoenus. No less an authority than Wendell Clausen observes the sense of cadence that shade lends to Eclogues I and X, while Peter L. Smith calls it Virgil's ‘most prominent pattern of visual imagery’.Footnote 45 Romani, fittingly, placed Amina and Elvino in a ‘shaded vale’ – an ‘ombrosa Valletta’ – and thus it seems only fitting that, upon surveying the hillsides in Act I scene 1, Rodolfo calls them ‘luoghi ameni’.

Figure 1. Title-page engraving from La buccolica di Virgilia (Rovereto, 1828).

Figure 2. Alessandro Sanquirico, set design for La sonnambula, Act II scene 2. (colour online)

Any Italian reader who, like generations before and after him, had spent hours in hot school rooms being lectured to on the perfection of Virgil's Latin must have recognised the echoes of classical pastoralism in Romani's libretto, which perhaps explains why one critic, unsure of how to classify the curiously serene tone of the opera, likened it to ‘un’ Egloga pastorale’.Footnote 46 This said, any discussion of pastoral literature should also recall the more recent, more familiar traditions of the cinquecento, the visions of Arcadia put forth in the Aminta and Il pastor fido, both of which had never ceased to be read. These works were often printed jointly in the nineteenth century, and critics of La sonnambula unwilling to reach all the way back to antiquity eagerly placed Romani alongside the master poets of the Renaissance: according to one, the libretto brimmed with ‘all the grace and good taste’ with which Tasso and Guarini had adorned their subjects.Footnote 47 As far as beeches and shade are concerned, however, there is no reason to distinguish between antiquity and the Renaissance: in Act I scene 2 of the Aminta, the eponymous shepherd describes how his love for Silvia was first kindled sitting ‘a l'ombra d'un bel faggio’.Footnote 48

The pastoral tradition had its detractors of course. In the wake of Madame de Staël's infamous attack on the servile imitation of the ancients, Alessandro Manzoni singled out for derision those Italian poets who had ‘transformed themselves … into so many shepherds who lived in some region of Peloponnesia under names that were neither ancient, modern, pastoral, nor anything else’.Footnote 49 Their herds and bagpipes, their meadows and thatched huts were a national embarrassment, and even a work as celebrated as Il pastor fido was, in the eyes of another critic, shot through with ‘scenes superfluous and idle’, ‘incidents incoherent and unnecessary’.Footnote 50 As is the case with most strands of historical reception, definite judgements are hard to come by. Yes, many critics dismissed pastoral poetry for the staleness of its imagery, but others could speculate about the endless variety possible in the depiction of ‘domestic peace; the affection between husband and wife, friends and brothers; paternal and filial love’. If critics found fault with the pastoral, they did so because of lack of understanding rather than any limitations inherent to the mode.Footnote 51 At best, pastoral poetry offered ‘a clear plot, characters simple and innocent, passions quiet and never overwrought, fluid and sweet versification, a style pure and natural, familiar and plain’, attributes reviewers also freely associated with La sonnambula.Footnote 52

Historical criticism, then, offers up a few conclusions: reading a libretto that evokes the Eclogues, early Italian listeners were drawn to fashion connections with the long tradition of pastoral literature, still enjoyed and debated in the 1830s. Whatever traces of alpine grandeur we might detect (or wish to detect) in the opera today, for the first listeners of La sonnambula the long shadows of Arcadian evening were still more familiar than any part of Switzerland. The question remains, however, whether the pastoral is a useful category for early nineteenth-century Italian opera, whether it applies to any aspect of musical style that can be held in the mind and meaningfully distinguished from other conventions of the period. The historicist approach falters here, for early reviews of La sonnambula are filled with language similar to those patches of literary criticism cited earlier, effusions of adjectives that leave the modern critic nowhere nearer to identifying actual moments of pastoral simplicity in the score, let alone the overarching design of the whole. It is not necessary to invoke grand theories or mythic claims about what Bellini has to teach us about our shared humanity. Something can be said about the opera that does not leave it to be heard as a wash of pleasantness alone.

Placing La sonnambula alongside another opera may help to discriminate its features more clearly. The comparison was often made – and continues to be made, especially as it was sanctioned by Bellini himself – with Paisiello's Nina, though the comparable shepherd's song aside, the work was written several decades prior, and stylistic differences are such that there is little to observe beyond the most superficial of likenesses. Closer musical relations are to be found in another opera with an extended pastoral scene, one performed at Milan's Teatro alla Canobbiana a few months before La sonnambula's premiere: Donizetti's Alina, regina di Golconda. Composed in 1828 – and thus easily overlooked among the operas that preceded Anna Bolena (1830) – Alina was a modest success, revived across Italy several dozens of times well into the 1850s. At first glance, there are many similarities with La sonnambula: a semi-serious plot, a shepherdess as heroine, a confused blend of romantic topics. There are pirates and shipwrecks, enchantment and jealousy, and the whole thing takes place in an imaginary kingdom in India, where, presumably, the air is scented with spice and no one questions having a sorceress queen. The French shepherdess Alina, now Queen of Golconda, spends much of the opera putting her former lover through a series of tests, the last of which involves conjuring up, in the style of Armida, the garden in Provence in which they first met.

The libretto, also by Romani, is filled with stock descriptions of the picturesque: ‘The scene depicts a village in Provence: a small wood on one side, on the other a rustic dwelling, in front of which a stream is crossed by a small bridge: in the distance, knolls and hills.’Footnote 53 Donizetti responds to Romani with a lesson in Italian pastoral: 6/8, A major and a prominent rhythmic figure that, as a stylised version of the Scotch or Lombard snap, had done so much to create the rustic character of La donna del lago (Example 5).Footnote 54 It is also possible to speak of diatonic purity, chains of thirds and sixths, and a limited harmonic orbit, as long as it is remembered that such observations apply to reams of non-pastoral music as well. Helpfully, the libretto calls for a brief passage of ‘musica pastorale’, immediately identified by Volmar as ‘i flauti de’ Pastori’: here, at least, the flute – and not the horn – remains the quintessential pastoral instrument.

Example 4b. Mozart, String Quartet in C major, KV 515 (1. Allegro), bb. 86–89.

For the modern analyst, this scene is striking: not only do score and libretto make explicit the pastoral sound of Italian opera around 1830, but both beginning and end, the limits of pastoral, are not left to conjecture. The scena and subsequent romanza are well bounded – A major reigns throughout. There is no doubt that a pastoral scene has passed when the chorus of maidens comes to a close, the last cadence sounds and the recitative begins once more. What is pastoral (more or less everything in this scene) and what is not pastoral (more or less everything outside of this scene) is clear. But in its very boundedness and transparency, this example from Alina also illustrates one of the principal challenges of writing about the pastoral, recalling the two analogous yet divergent definitions of pastoral.

This scene in Alina is an example of what might be called the ‘topical’ or the ‘characteristic’ pastoral. In opera studies – and writing on music more broadly – listening for such localised effects is reinforced by the limits of the musical example as it appears in book chapters or journal articles. Space is limited, printing scores for the specialist expensive, perhaps unnecessary, and the eight- or sixteen-bar excerpt depends on the author's ability to take a stick and point at some relation that can be readily grasped: ‘These bars are pastoral; I see the drone, the echoing horn calls.’ La sonnambula has few bounded pastoral moments similar to Donizetti's Alina, however, though it is possible to listen to the opera again, making note of every prominent horn effect, every aria or duet in a compound metre (there are several), and every melody that, even by the standards of the day, bespeaks self-conscious simplicity. Some lists and charts, perhaps a graph or two – these are inadequate substitutes for this opera. It is therefore necessary to turn to the second, the looser understanding of pastoral.

This version of the pastoral is far more forgiving. It depends on ‘pastoral principles and outcomes’, as Hatten has recently argued, to reveal ‘an overarching mode that coordinates the dramatic trajectory and expressive significance of the work’.Footnote 55 Hatten sees the distinction between the two versions of pastoral as aligning with classicism and romanticism, or the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries more broadly. One age deployed the pastoral as a topic, enjoyed its characteristic pieces, its drones and musettes; the other ‘troped’ the pastoral, expanding it in various directions to encompass whole movements or even whole symphonies. When the pastoral becomes a title, a trope, it gathers together all other topics; they cease to operate independently, and it is no longer possible to discriminate bar from bar. Hatten's theory – however much it might be said to reproduce rather too neatly Schiller's opposition between the naïve and sentimental – works for analysis, for it allows larger arguments to be made about style, about how music might relate to literature, to retreat, to closure and convention, and to our shared ‘double longing after innocence and happiness’.Footnote 56 Indeed, amid a wide-ranging critique of topic theory and topic theorists, Stephen Rumph singles out Hatten's treatment of the pastoral for its ability to show how an individual topic ‘is articulated through oppositions within the musical structure’.Footnote 57

All this returns the discussion to the central problem of the pastoral. It is a musical topic – discrete, uncomplicated, historical – that can be taught to anyone who can identify a drone. It is also a vague amalgam of feelings – about purpose, labour, sexuality, landscape, tradition, alienation, longing – that has found expression in some of the best (and worst) poetry of the past 2,000 years. Ingenuity is not needed to identify the first kind of pastoral. Undergraduates can hear the shepherds’ music in Messiah; the discussions in this article of Alina or La sonnambula's horn calls involved no analytical wizardry. The presence of the first type of pastoral, however, so often serves as a pretext to write about the second type, with concrete, indisputable observations (these bars do not leave the tonic; here is the flute and the horn) giving way to sweeping assertions about our shared humanity. In the end, the problem of the pastoral has very little to do with the advantages and limitations of topic theory, for it is a problem that plagues all sensitive people who wish to write about aesthetic experience. In Hatten's reading of Schubert's Piano Sonata in G major – the reading praised by Rumph – he detects a ‘penetration to the sublime by means of the fulfilment of plenitude and the timelessness of mystic oneness’.Footnote 58

Wanting to feel at home in the world is a shared human desire, and many writers believe that, understandably enough, music can offer a glimpse of the garden from which we have all been banished. The visions of Beethoven or Schubert differ from that of Bellini, however, and thus to enter Bellini's pastoral world requires us to readjust our expectations for what counts as musically significant. What follows is a discussion of Bellini's treatment of closure in his pastoral opera, his experiments with a pervasive but seldom discussed musical convention that he would not repeat in Norma or I puritani. It may have little to do with the listening habits of early spectators, but if 2,000 years of pastoral poetry have taught us anything, it is that some things may have to be accepted as lost and unrecoverable.

Bellini's idyllic endings

Near the end of the Act I finale, a few words from a distraught Elvino are enough to throw the entire universe of La sonnambula into disorder: ‘Non più nozze!’ (‘There'll be no wedding!’) The community – the chorus, joined by Alisa and Alessio – takes up this call. The curtain falls, and the audience is left to contemplate how the world will be set right in Act II. In early nineteenth-century Italian opera, the Act I finale is conventionally the moment of greatest dramatic tension, and Romani's gesture here cannot be called particularly subtle. It is a testament to the stability of the social order enjoyed by Amina, Elvino and their friends that the most catastrophic disruption imaginable is the cancellation of the wedding feast. That this is a world governed by the conventions of comedy could hardly be more obvious: there may not be a wedding now, but from the beginning no one could doubt how it will all end.

It is thanks to Wye Jamison Allanbrook that we are now attuned to how these conventions governed not only dramatic but also musical logic. Symphonies and piano concertos could have happy endings just as often as operas, and Allanbrook's interest in comedy leads her to ponder one of the most fundamental of musical gestures: the cadence. Cadences, humble yet indispensable, are everywhere in late eighteenth-century music, whose ‘emphatically end-oriented’ design is, for Allanbrook, ‘an enormous part of its appeal’ and grants many of the works of Mozart and Haydn their ‘sense of dramatic coherence, of something having been seen through to an end’.Footnote 59 Her praise of the cadence is in keeping with her characteristic defiance of all those romantics who distrust the endings of KV 466 or Op. 37, not to mention the legions of theorists who, following them, are apt to consider the merry train of dominants and tonics at the end of any instrumental work ‘much ado about nothing, mere comic dither’.Footnote 60 The harmonic drama of sonata form – or whatever one chooses to call the large-scale opposition between two key areas a fifth apart – requires this sense of closure, these ‘waves’ of cadences spilling over the page at the end of both exposition and recapitulation. Though often void of any distinctive melodic character, occurring at moments of motivic liquidation, if one wishes to follow Schoenberg, these successive iterations of V–I are ‘by no means structurally superfluous’, even if they can easily become ‘the butt of musical caricature’.Footnote 61

Allanbrook's words ring with the self-assurance of the iconoclast, though her quarrel with the theorists seems to have been inspired by the methods – rather than the results – of analysis. ‘The just amount of cadential formulas required to gain the period is’, she writes, ‘a function of syntax’, later noting how cadences are essential to achieving a sense of ‘judicious proportion’.Footnote 62 Just and judicious – there is no effort to conceal praise of the master, even if these conclusions have been reached by a pleasantly unfamiliar route. One wonders whether all composers’ judgement was as sound as Mozart's in an age when – ‘perhaps at no other time before or since’ – closure was ‘such a significant musical issue’.Footnote 63

Few would wish to dispute Mozart's authority in matters of syntax, but it is possible to question whether his age was unique in its obsession with closure. Romani reminds us how the rules of comedy were still observed in Milan in 1831, while Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti wrote opera after opera alongside which Mozart's interest in formal and harmonic closure appears to shrink to indifference. Any listener familiar with this repertory will instinctively recognise the importance of cadences, and the historical record reassures us that he is not alone in enjoying their pleasures: Giuseppe Carpani called their appearance in Rossini an embarrassment of riches (‘lusso e dovizia di cadenze’), the frequent ‘invigorating and enriching of the harmony’ or the ‘resolution of the dissonance’ leading to pleasures inexpressible (‘producono un piacere indicibile’).Footnote 64 If Haydn could occasionally use cadences to pointed effect, Rossini made them an integral part of his style.

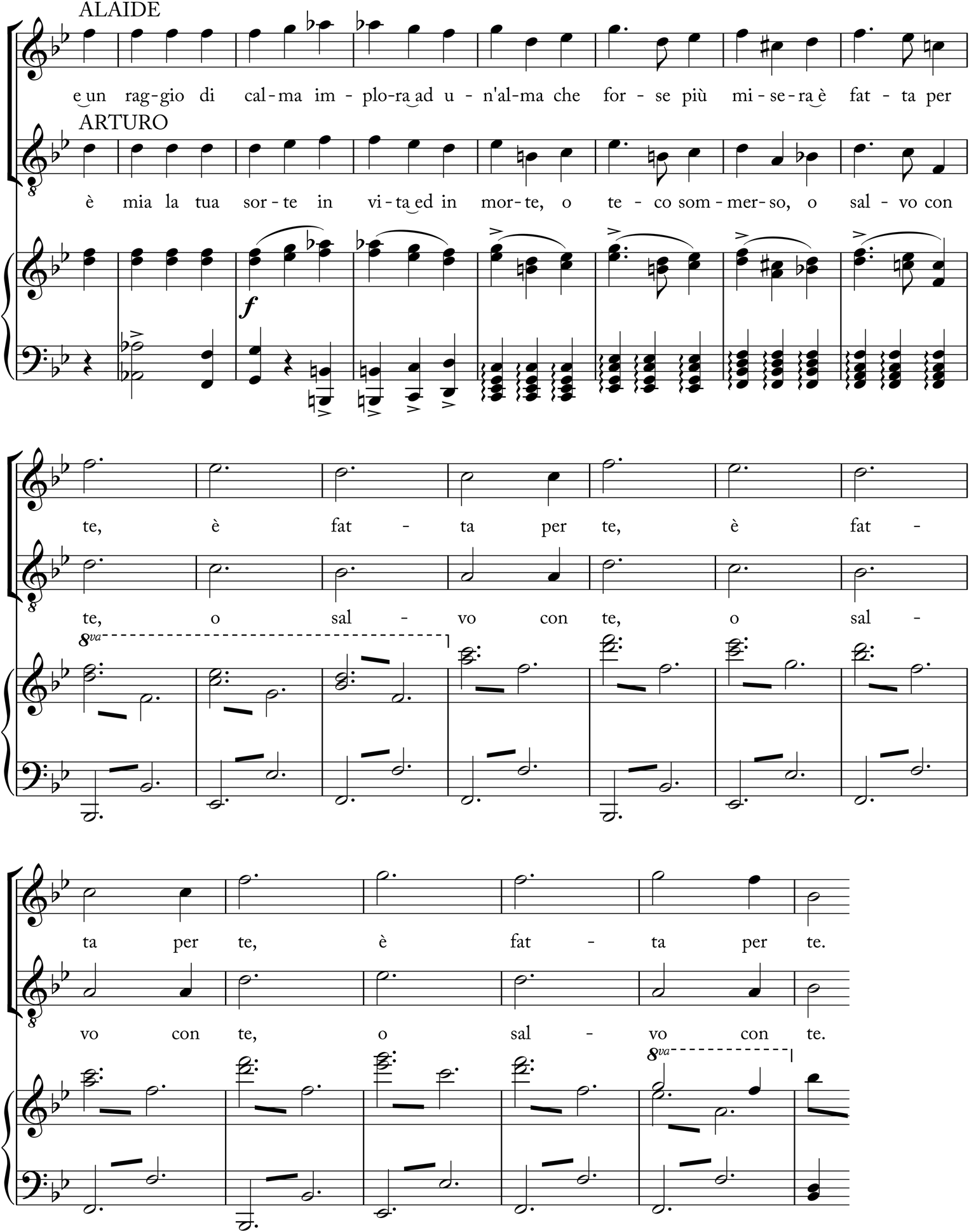

One of the cadences most frequently used by these composers – and joyously anticipated by audiences – is the so-called felicità cadence, a name borrowed from Donizetti, who, when setting out to edit Poliuto to make it more palatable to Parisian tastes, wrote to Mayr about the need to reduce the ‘cadenze felicità felicità felicità’.Footnote 65 It is marked by a melodic descent ![]() $\hat{5}$–

$\hat{5}$–![]() $\hat{4}$–

$\hat{4}$–![]() $\hat{3}$–

$\hat{3}$–![]() $\hat{2}$ (or

$\hat{2}$ (or ![]() $\hat{3}$–

$\hat{3}$–![]() $\hat{2}$–

$\hat{2}$–![]() $\hat{1}$–

$\hat{1}$–![]() $\hat{7}$), which is repeated, often several times, often with the rhythm diminished, before a final arrival on 1. The harmonies are invariably the same – I(6)–ii6–Vþ¼–V

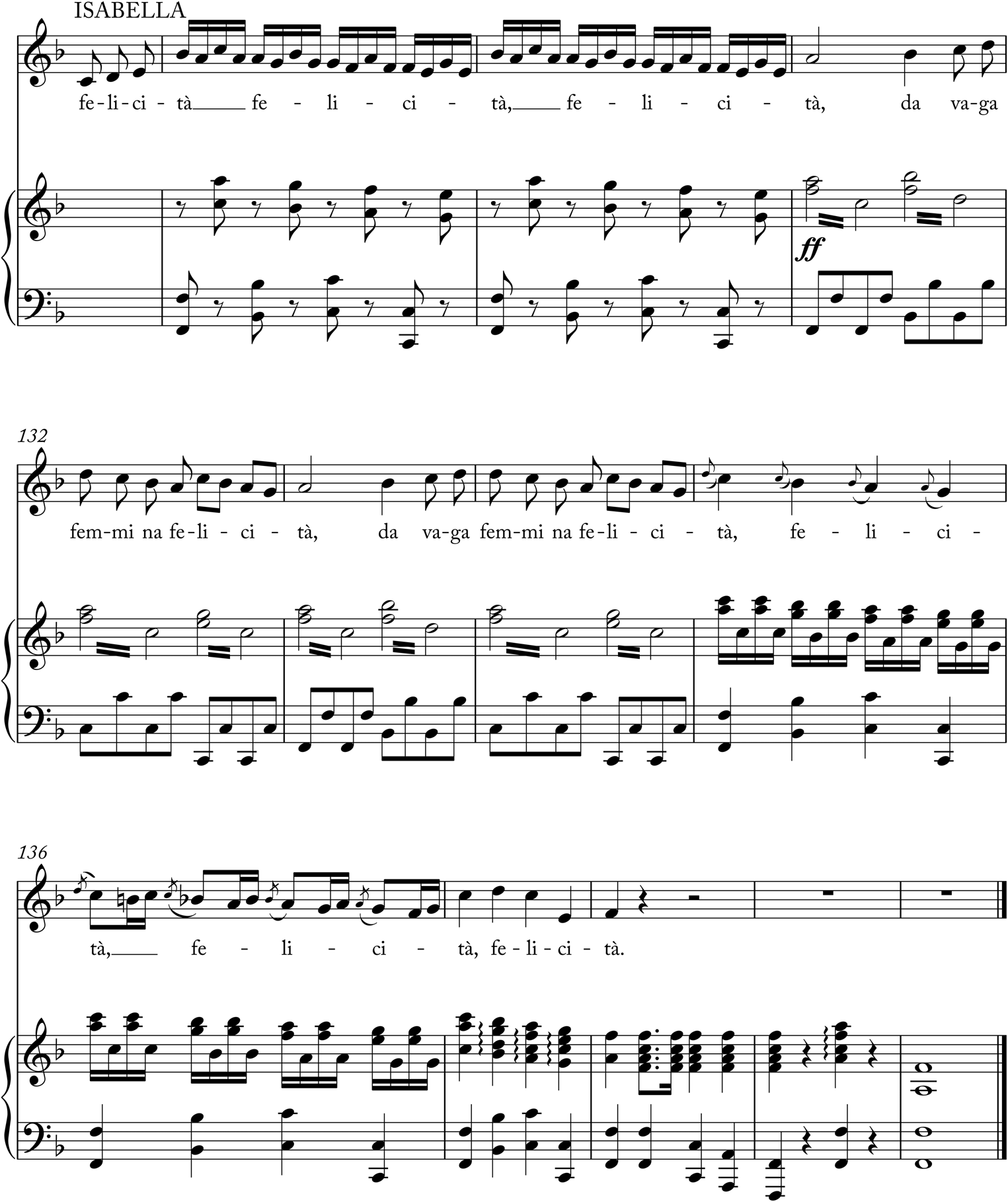

$\hat{7}$), which is repeated, often several times, often with the rhythm diminished, before a final arrival on 1. The harmonies are invariably the same – I(6)–ii6–Vþ¼–V![]() ${\tf="TT9f7a5eeb"{{\raise4.5pt{\atop^{{5}}_{{3}}}}}}$, with the goal naturally being I – and Donizetti was evidently recalling the frequency with which the word ‘felicità’ was set to this pattern when he complained about it to his mentor. Rossini had made them famous, a representative example being the conclusion of Isabella's first aria in L'italiana in Algeri (Example 6, bb. 135–6).

${\tf="TT9f7a5eeb"{{\raise4.5pt{\atop^{{5}}_{{3}}}}}}$, with the goal naturally being I – and Donizetti was evidently recalling the frequency with which the word ‘felicità’ was set to this pattern when he complained about it to his mentor. Rossini had made them famous, a representative example being the conclusion of Isabella's first aria in L'italiana in Algeri (Example 6, bb. 135–6).

Example 5. Donizetti, Alina, regina di Golconda, from Act II, no. 7 Coro e duetto.

The felicità cadence is often joined by several other cadential figures at the end of a cabaletta, though it derives its force in part from the fact that one need not have paid any attention to several minutes’ worth of music for the ear to latch on to the pattern and recognise how to enjoy it. Much of its effect comes from what Janet Schmalfeldt has called the ‘one more time’ technique. The term – almost disarming in its simplicity – does not describe any moment of mere repetition, she insists; what distinguishes this practice is ‘its capacity to withhold resolution precisely where the cadence reaches its highest degree of tension, its potential for creating surprise through thwarted expectation, and for disrupting the rhetoric of closure, with the result that what is repeated becomes imperative, and thus emphatically dramatic’.Footnote 66 Such cadences are scattered through late eighteenth-century music, adaptable to any variety of melodic figurations, so long as, by leaping to an active scale degree, the expected arrival on ![]() $\hat{1}$ is temporarily deferred. A few examples in Cimarosa or Paisiello aside, however, it was Rossini who standardised the shape – brazenly straightforward – endemic to Italian opera, such that Giorgio Paganonne can place it alongside the lyric form or the groundswell as one of the favoured conventions of the age.Footnote 67

$\hat{1}$ is temporarily deferred. A few examples in Cimarosa or Paisiello aside, however, it was Rossini who standardised the shape – brazenly straightforward – endemic to Italian opera, such that Giorgio Paganonne can place it alongside the lyric form or the groundswell as one of the favoured conventions of the age.Footnote 67

While it is possible to speak of Mozart's ‘just’ handling of proportion and form, recent studies of the romantic overture have been eager to stress the unbalanced proportions favoured by Rossini and his followers. For Steven Vande Moortele, the crescendos and cadences in Rossini's overtures ‘overshadow all that precedes [them], in spite of the fact that [they are] structurally optional’, while Scott Burnham hears them as ‘mark[ing] generic convention, again and again’ in a manner that does not ‘relate to the rest of the overture’.Footnote 68 Though many of his techniques – ‘one more time’ and all – were inherited from the previous century, it was Rossini, as these analysts hear him, who transformed form into the formulaic. Because Rossini would never use a felicità cadence in an overture – the pattern was conceived for a voice (or voices) supported by a monolithic orchestral texture – it is possible to bypass these discussions of form: some commentators have ignored formalist concerns altogether and assigned these cadences the workaday function of reminding spectators when to clap. The Germans, disparagingly, invented the term Bettelcadenz for cadences that ‘beg’ for recognition, while for David Kimbell, their ‘loudness and brashness illuminate no dramatic issue; they serve merely to stimulate the audience's enthusiasm’.Footnote 69

It is difficult to disagree with Kimbell's assessment, though his observations do little to explain the appearance of the felicità pattern at moments when prompting applause would not seem to be the task at hand. Take the beginning of the Act II trio in La donna del lago, for example, when Elena's first statement – miles from the end of the number – is rounded off with a cadence that seems to have been plucked from the previous century: the harmonic movement quickens; the voice outlines the supertonic harmony before a graceful turn around ![]() $\hat{1}$ at the cadential dominant; an oboe oversees the whole thing from above. Rossini immediately asserts himself over Mozart, however: virtuosity and felicità follow, such that we almost forget that the singer had already reached a satisfactory ending (Example 7). In Caplin's terms, such moments can be described as overbrimming with ‘cadential content’, bearing little resemblance to the true ‘cadential function’ of the formal ending.Footnote 70

$\hat{1}$ at the cadential dominant; an oboe oversees the whole thing from above. Rossini immediately asserts himself over Mozart, however: virtuosity and felicità follow, such that we almost forget that the singer had already reached a satisfactory ending (Example 7). In Caplin's terms, such moments can be described as overbrimming with ‘cadential content’, bearing little resemblance to the true ‘cadential function’ of the formal ending.Footnote 70

Example 6. Rossini, L'italiana in Algeri, from Act I, no. 4 Coro e cavatina.

In this example, the contrast between late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century senses of harmony is at its most dramatic. Germany vs Italy; harmony vs melody; form vs content; text vs performance: all the old oppositions come swimming to the surface. It is true that the proportions may seem unbalanced on the page; it is true that the cadential gestures strike the ear as excessive, ostentatious, pedestrian and theatrical. Before accepting the terms of defeat and choosing instead to celebrate melody and song, it is first necessary to acknowledge what seems a basic, though seldom articulated, distinction about how musicians on both sides of the Alps handled their inheritance of the classical style. When the great fog of romanticism descended on northern Europe, composers in damp, lonely rooms across Germany and Austria began to resist the old conventions by turning inward; open any page of a celebrated lied, and one is likely to find harmonic movement at the level of the bar – dense, twisted, often unexpected – that few composers writing in the settled decades before 1789 would have dared imagine. Today, those in the business of writing about music have much to say about this repertory, though their techniques can only ever be imperfectly mimicked when dealing with Italian opera: the reliable use of @VI notwithstanding – and how much has been made of this sonority! – this is not a repertory of harmonic daring. That is not to say that it is a repertory without a sense of harmony, only that the sense of harmony works by the page rather than by the bar. On the whole, the Italian response to the eighteenth century's sense of punctuation and tonality – its ‘emphatically end-oriented’ design – was to expand rather than contract, thus the seemingly disproportionate number of cadential gestures needed to close overtures, arias and ensembles that never strayed far from the tonic.

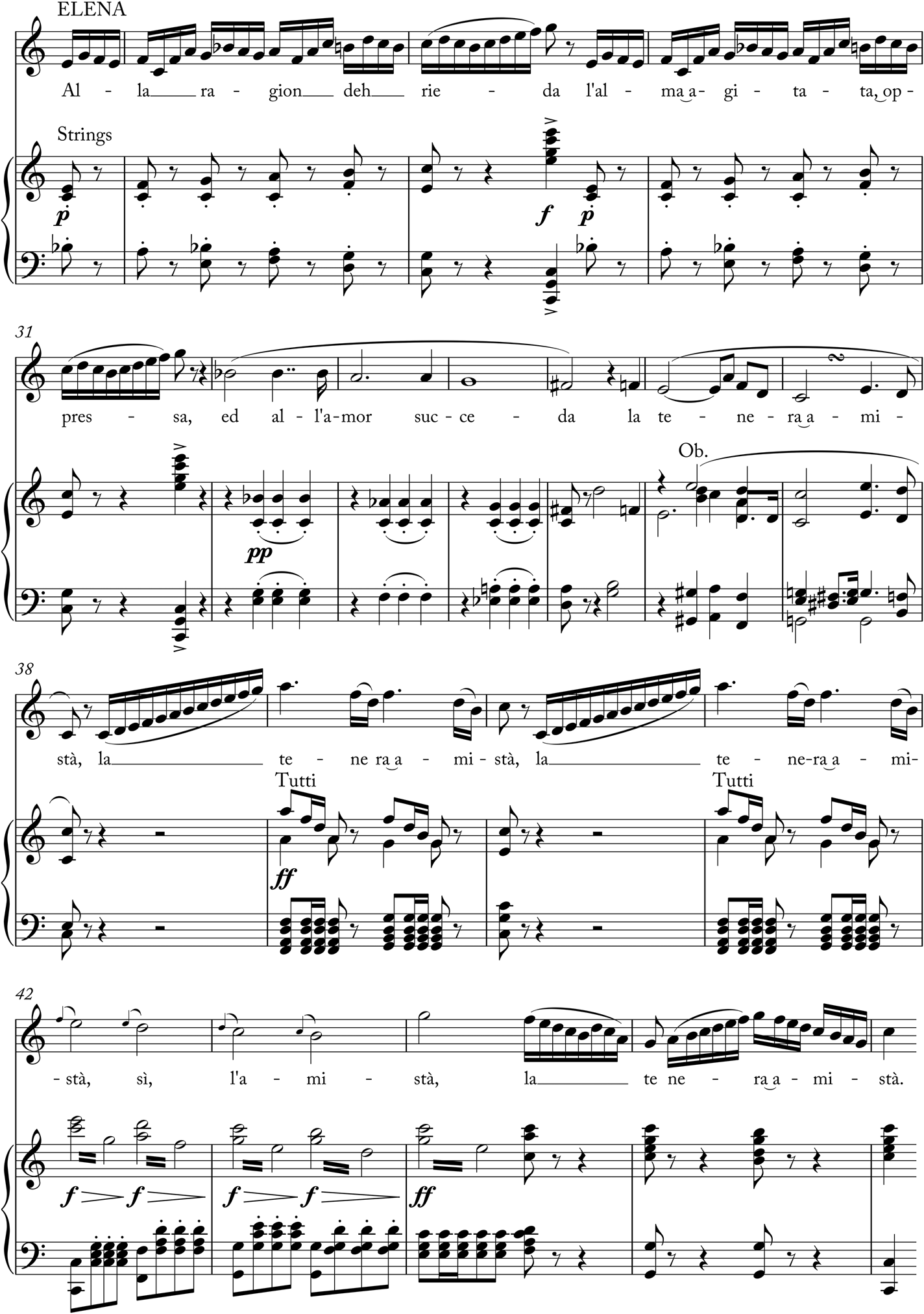

The logic of these cadences is so indispensable to early nineteenth-century Italian opera that even though Bellini may, in Il pirata and La straniera, have cultivated a style that eschewed Rossini's pyrotechnics, he could not abandon the Rossini cadence. The cabaletta that closes the Act I duet between Alaide and Arturo in La straniera is representative of Bellini's temperate approach in the opera (Example 8a). There is nothing extraneous in either accompaniment or vocal line until the end, where the speech-like text setting is engulfed by the felicità cadence (Example 8b). Any number from La straniera could illustrate this point: for all of Bellini's radicalism in the main lyric numbers – marked by their lack of melody, something closer to arioso than aria – the conclusions are invariably, and pleasurably, the same.Footnote 71 Perhaps Bellini knew his austere style would challenge audiences in Milan enough that he did not wish to leave them in doubt about when to applaud as well.

Example 7. Rossini, La donna del lago, from Act II, no. 9 Terzetto.

Example 8a. Bellini, La straniera, from Act I [no. 5] Scena e duetto.

And yet, are the proportions in Rossini and Bellini not just? Would any listener be satisfied if these cadences were expunged? To establish what counts as musically sound in this repertory – at least insofar as pacing and closure are concerned – is no easy task, particularly given the performance record. Here there is chaos instead of consolation, for over the past century conductors have subjected Rossini's, Bellini's and Donizetti's cabalettas and their codas to the most savage of cuts. Changing the score is inevitable, often welcome, but there are few things as disorienting in the theatre as hearing a felicità cadence prematurely initiated (or unexpectedly removed). Completeness need not be the ideal in order to question what makes one arrangement of cadences at the end of a movement successful and another not. Writing about them presents its own challenges, for such moments also stretch the boundaries of what is possible in the printed example. Though it is undoubtedly a singular, recognisable musical feature, the felicità cadence cannot always be captured on the page, as anyone who has ever listened to an Italian opera with the score at hand will know. Especially at the end of an act or a large ensemble, one is not so much reading the score as trying to keep pace with the page turns. A chart may be of some use. Does a cabaletta of a certain length seem to demand a certain number of cadences? If the repeat is cut, should the cadential material be proportionally cut as well? On the whole any writer will struggle to put words to something that must be felt rather than seen.

Once we accept the importance of closure and cadences to this style, how does our view of the pastoral elements of these works change? Asking what the lives of shepherds have to do with the logic of musical closure – admittedly, an unorthodox question – leads to two contradictory theses. On the one hand, the cadence is antithetical to the pastoral. The natives of Arcadia were content to remain in the tonic, and cadences often mark the moment when the illusion of the garden becomes apparent. This tension between a sense of timelessness and the conventions of our world is displayed in miniature in Corelli's offering for the birth of Christ. The last movement of the Concerto fatto per la notte di Natale, Op. 6 no. 8, is in 12/8 and features violins moving in thirds above a sustained bass. But Corelli cannot maintain the atmosphere for more than a bar and a half before the drone passes away and the violins diverge for the voice leading demanded by the cadence (Example 9). The pleasures of pastoral otium, Corelli shows us, are fleeting.Footnote 72 On the other hand, to return to a point raised by Caplin, the pastoral's insistence on root-position tonic stability makes it a close ally to the cadence, or at least reinforces its effects.Footnote 73

Example 8b. Bellini, La straniera, from Act I [no. 5] Scena e duetto.

These were not idle concerns for Bellini, especially given his handling of the felicità cadence in La sonnambula. The first duet shared by Amina and Elvino in Act I (‘Prendi: l'anel ti dono’) is a leisurely affair, even by the standards of Bellini's long melodies. Though 12/8 is not necessarily an unusual metre for Italian opera, nor B flat major an unusual key, both conspire to produce an atmosphere of hushed tranquillity fitting for a pair of lovers who have no reason to expect anything but a cloudless future.Footnote 74 Technically, the critical edition insists, this is Elvino's entrance aria, but given the amount of the time the characters spend singing together, to hear it as an aria rather than a duet demands an unlikely commitment to rule-following.Footnote 75 The orchestration – soft woodwinds in thirds – could have been borrowed from any of Mozart's most tender scenes. This is Bellini at his most pastoral, though it is hard to say whether the harmonies are more reserved, the melody more serene than in any other opera.

The Act I duet between Giulietta and Romeo from Bellini's previous opera offers a useful comparison in this respect. Formal considerations are more important here, for identifying the Sonnambula number as an aria – rather than a duet – means that it is not surprising that Elvino begins his slow movement with no preparation. The duet in I Capuleti e i Montecchi has its scena and the customarily agitated tempo d'attacco, which inevitably casts the slow movement as a kind of retreat, a moment of reflection, a bower of musical loveliness. The form corresponds with the dramatic exigencies of the scene: Romeo urges Giulietta to flee with him, and she hesitates in the name of duty. Questions of honour and the heart are duly contemplated over an Andante. In La sonnambula, by contrast, Bellini is free simply to present one of his long melodies. There is no dramatic justification for this mood, but then again shepherds have never needed a reason to express their happiness in song.Footnote 76 That the melodies also have markedly different shapes is also noteworthy, insofar as we believe melodic contour can tell us something about character. Romeo's range is more extensive than Elvino's, with upward leaps as wide as a ninth. Elvino barely extends beyond a fifth, and when anything is assigned to him that is not stepwise, those leaps are usually downward, though these are sighs of contentment rather than sighs of grief.

The fast movement in the Sonnambula number differs little in mood from the first movement – we have not left B♭ major, and 6/8 hardly contrasts with 12/8 – but if there was little dramatic justification for the slow movement, there is even less for the transition to the cabaletta. Amina's brief use of G minor is a sign of her sadness, to be sure, but these tears mark a joyful speechlessness rather than any real sorrow. When the chorus of villagers enters to encourage their love, they are accompanied by a perpetual motion figure in the strings over alternating tonics and dominants – a series of scales, motivic liquidation; the hand of the organ grinder is spied out of the corner of the eye – which reaches an abrupt end to allow for Amina and Elvino a chance to repeat their song. When the chorus enters for a second time, however, a composer's difficulties become apparent: how does one terminate such circular music? The unison A@s are expected by no one, and before it is possible to conceive of what new directions this music may take, Bellini has initiated a felicità cadence and the duet is swiftly brought to a close (Example 10). The differences with the Corelli excerpt are matters of degree rather than kind, for both composers must find a way to reconcile musical and pastoral convention, which in this instance are fundamentally at odds. The felicità cadence thus sounds unusual here, especially for such a careful composer, if only because it cannot be conceived as the inevitable conclusion to the accumulation of musical energy.

Example 9. Corelli, Concerto grosso, Op. 6 no. 8 [VI.] Largo. Pastorale ad libitum.

It is difficult to say, of course, whether the pastoral mood of La sonnambula prompted Bellini to be more self-conscious about his habits of closure, but there are enough idiosyncrasies in the opera that such a thesis can at least rest in the land of possibility. Rodolfo's aria (‘Vi ravviso, o luoghi ameni’), which follows almost immediately on this duet, also features an unusual ending. Much about the aria can pass without mention, though the last section of the cabaletta, marked più mosso, offers a lesson in the Italian cadence. This section too has a feeling of being somewhat detached from the preceding music, perhaps because the bass line, which had lain dormant, at least unnoticeable, for the past minutes, suddenly assumes a more active role as, through a series of descending and then ascending scales over six bars, it marks out the beginning of an expanded cadential progression: I–vi–IV. The arrival on the cadential 6/4 and the convergence of the voices signal the beginning of the felicità progression, but its pleasures are deferred by a wholescale repetition of the scalar pattern (Example 11a). As much as the repetition sounds as if it is thwarting expectations, the proportions are such that it would transform convention into unbalanced musical nonsense if this passage were not repeated. Still, it is a relief when the felicità progression appears – leisurely, plainly, with none of the adornments we might expect from Rossini – which makes what follows all the more surprising. While the progression could have led to a satisfactory close, Bellini adds a third iteration of the felicità pattern, though this time marked by uncharacteristic homophony: voices and accompaniment declaim the cadence in unison, with Bellini swapping an applied dominant for the cadential 6/4 (Example 11b). The texture is thick, muddled even, and the touch of dissonance seems to remind us simply that all endings do not have to be the same.

Example 10. Bellini, La sonnambula, from Act I, no. 3 Scena e cavatina.

More perplexing still is the felicità cadence in Amina and Elvino's other, proper duet in Act I (‘Son geloso del zefiro errante’). The lovers have quarrelled, but the reconciliation is so swift that the duet again feels like an excuse for more singing. The vocal pattern follows standard procedure for such moments, the shepherds singing independently until their dispute is resolved, which prompts a good deal of parallel sixths and some virtuosic coordination of trills, scales and roulades that did not escape the notice of the opera's first reviewers – Pasta and Rubini were evidently in fine form at this moment.Footnote 77 The orchestra plays almost no role here, pulsing through a series of cadential progressions. It is difficult to imagine a more fitting example of timelessness and the Italian pastoral than this. The challenge for such music – which feels as if it has neither beginning nor end – is to bring it to a close. One solution is to initiate a felicità cadence out of nothing, one that, moreover, departs from all precedent (Example 12). The pattern is familiar – tremolo strings; a declamatory vocal line; one syllable for each harmony – but the setting is unfamiliar, in this moment of such tenderness. The vocal parts sit unusually low (the singers simply do not sing in many performances), and the harmonies diverge from the expected pattern: the feint to the submediant makes this moment less an example of ‘one more time’ repetition than a genuine deceptive cadence. But unlike in the first aria-cum-duet, when the sudden felicità progression was the means to force a conclusion, here the cadence is an interruption: there is still plenty of singing to be had, though now the orchestra is all but absent until the very end. There can be no cadence here, however; the musical energy so far accumulated has already been spent. Amina and Elvino are left to suggest the dominant, and the orchestra can only respond by confirming the tonic (Example 13).

* * *

Bellini would not wholly abandon the convention of the felicità cadence after La sonnambula – it is dispersed throughout his last three operas – but neither would he test the pattern in quite the same way again. The truly radical gesture would have been to dispense with such cadences all together, as he did when he was at his most original: there is nothing even close to a felicità cadence in the second act of Norma. As Mary Ann Smart has observed, however, anyone who wishes to account for the effects of experiment and innovation must be willing to embrace convention and repetition.Footnote 78

Example 11a. Bellini, La sonnambula, from Act I, no. 4 Scena e cavatina.

Example 11b. Bellini, La sonnambula, from Act I, no. 4 Scena e cavatina

Example 12. Bellini, La sonnambula, from Act I, no. 6 Scena e duetto.

Example 13. Bellini, La sonnambula, from Act I, no. 6 Scena e duetto.

The confluence of musical and literary convention in La sonnambula alerts us to the challenges of writing about familiar pleasures. The fact that the cadences operate differently in this opera allows us to see how they had been operating without our notice all along. And while descriptions of musical effects often privilege originality (either explicitly or implicitly), Bellini's treatment of cadences here reminds us that some things are successful precisely because they work with the stuff of everyday life. As Carpani said about Rossini's handling of cadences, ‘not everything is new, but it is the whole that is new’.Footnote 79 This is the lesson of the pastoral, which relies on a stock of conventions and evolves through constant reference to previous iterations of itself. One instance is only intelligible within a tradition, and the pastoral's central conceit is that the community of shepherds might tell us something about what we share amongst ourselves. Perhaps it is for that reason that La sonnambula is a pastoral opera: neither for its melodic serenity, nor for its horn calls and compound metres, nor for its echoes of Virgil, but rather for the simple opportunity it gives us to reflect on why we return to some music over and over again.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Mary Ann Smart and Emanuele Senici for their helpful feedback on earlier versions of this article.