Introduction

European prehistory has traditionally been arranged into closed boxes defined by a number of diagnostic items and specific timing that supposedly allowed discrimination between differentiated archaeological cultures (Shea Reference Shea2019). These idealistic entities have been organized in evolutionary sequences in which changes and ruptures prevailed over continuities. The end of the Palaeolithic cave-art traditions is one of the best examples of this theoretical framework and, in many aspects, it is the case too for the deep ruptures and population replacements proposed as an explanation for the quick adoption of the Neolithic across the continent. Behind these two specific examples, there is a certain disdain for the period in between, the Mesolithic, perceived very often as an irrelevant transition between two significant milestones: the heights of Palaeolithic culture and the starting-point of our own way of life. In this paper, we evaluate some forms of evidence that call into question these general trends in European prehistory, specifically with regard to the abrupt end of the Upper Palaeolithic artistic traditions. According to the evidence, Late Upper Palaeolithic (LUP) graphic expressions in the Iberian peninsula may have intertwined their imagery with nascent Levantine art, suggesting a continuous development that blurs some previously perceived contrast between them.

Our research took place place in two rock-art sites, Cañada de Marco and Los Borriquitos, with Levantine and Schematic rock paintings and with engravings of Epimagdalenian style, the LUP style in Mediterranean Iberia. We recorded an unusual series of overlaps between the graphic expressions in these sites. The finding of figurative and geometric engravings interstratified with the Levantine and Schematic rock paintings offers a glimpse of the continuities between the symbolic codes of the last stages of the LUP and the earliest stages of Levantine art. This is a crucial finding because it could give a solid answer to the open questions about the exceptionality of Levantine art in prehistoric Europe (Robb Reference Robb2015) and about similarities between graphic and symbolic expressions across western Europe around the Pleistocene–Holocene boundary. Levantine art is characterized by vivid depictions of human activities and their interactions with animals, but its chronological background, and in consequence the role played in the social reproduction system, is under debate for the scarcity of evidence to clarify its origin. The facts studied in these two sites suggest that Levantine art evolved from Epimagdalenian rock art and that, in consequence, it is one of the last cultural traits of hunter-gatherers in Holocene Europe.

This significant finding should be contextualized into the growing amount of evidence for LUP and Early Mesolithic (EM) art across Europe (Dalmeri et al. Reference Dalmeri, Cusinato, Kompatscher, Kompatscher, Bassetti and Neri2009; Płonka Reference Płonka2003; Veil et al. Reference Veil, Breest, Grootes, Nadeau and Hüls2012) that has called into question the end of figurative graphic expression during the Pleistocene–Holocene transition. In southwestern Europe, since the beginning of the twentieth century, it has been considered that the end of the Palaeolithic cycle and its millennia-long tradition came abruptly to an end shortly after the Magdalenian (Breuil Reference Breuil and Boyle1952), the moment at which paradoxically it had reached its highest peaks of technical skill and artistic beauty, with higher frequencies in the production of art. Afterwards, post-glacial art would have been reduced to geometric patterns decorating pebbles and slabs retrieved from some Azilian sites across Europe. It seemed that figurative art agency was no longer necessary for post-glacial societies, or that artists had lost the ability to depict the real world. This paradigm was maintained by Leroi-Gourhan (Reference Leroi-Gourhan1971), but it started to breach with the identification of a number of figurative motifs on mobiliary items retrieved from French Azilian sites (Célérier Reference Célérier1988; Coulonges Reference Coulonges1963; Deffarge et al. Reference Deffarge, Laurent and de Sonneville-Bordes1975). This unexpected continuity in the production of figurative art was called Style V (Roussot Reference Roussot and Clottes1990). In the Iberian peninsula, researchers revisited some decorated slabs and newly discovered open-air rock-art sites with engravings and suggested their LUP age, which has been corroborated by well-dated archaeological contexts (Domingo & Roman Reference Domingo and Roman2020). A newly abrupt rupture in graphic expressions was proposed afterwards until the arrival of the Neolithic colonizers (Domingo & Roman Reference Domingo and Roman2020; Villaverde Bonilla et al. Reference Villaverde Bonilla, Román, Pérez-Ripoll, Bergadà and Real2012). The idealistic paradigm for Palaeolithic art was safe again.

However, the profound transformations in the lithic techno-complexes and in the subsistence patterns around the Pleistocene–Holocene transition are not directly correlated to the slow-paced changes attested in the symbolic record, as has been clearly demonstrated by the continuity of Magdalenian-style depictions into early Azilian levels (Naudinot et al. Reference Naudinot, Bourdier, Laforge, Paris, Bellot-Gurlet, Beyries, Thery-Parisot and Goffic2017). Symbolic cultural markers of the Mesolithic populations such as personal ornament items (Newell et al. Reference Newell, Kielman, Constandse-Westermann, van der Sanden and van Gijn1990) suggest gradual changes that highlight the continuities of the post-glacial hunter-gatherers in Europe with their LUP ancestors, even at genetic level (Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Niemann and Iversen2019). In a similar sense, Bueno Ramírez et al. (Reference Bueno Ramírez, de Balbín Behrmann and Alcolea González2007) have repeatedly suggested the continuity of Upper Palaeolithic traditions into the early post-glacial graphic expressions in northern Iberia, proposing an uninterrupted evolutionary framework in which the Iberian Style V examples could be connected to the origin of Levantine art in Mediterranean Iberia. Our contribution to this debate supports this last scenario, in which symbolic productions changed in post-glacial Europe, and specifically in Mediterranean Iberia, at a slow rate in comparison with technological assemblages. Human adaptations to the changing environments of the Holocene by means of social devices like Levantine rock art involved keeping the connections with long-duration symbolic traditions through some shared imagery and the recursivity in the use of rock-shelters that defined ancestral hunter-gatherer landscapes.

Rock art at Cañada de Marco and Los Borriquitos

The Cañada de Marco rock-art site is a 10 m long shelter (Fig. 1a–b) located in Alcaine (Teruel province). According to the latest revision there are 153 pictographs, mainly of Levantine style, distributed over five panels (Ruiz López et al. Reference Ruiz López, Royo Lasarte, Royo Guillén, Alloza Izquierdo, Uzal and Rivero Vilá2016) (Fig. 2). Levantine pictographs exhibit a notable variety of form and colour that could be linked to the recurrent use of this site over a long time, while Schematic pictographs were distributed in the periphery of the shared panels with Levantine art, or in the outermost panels surrounding Levantine ones. This structure suggests the addition of Schematic art to a shelter previously used for Levantine artists. There are some superimpositions between Levantine pictographs, but we do not currently have a clear seriation for all of them, even when specific physico-chemical analyses were carried out for this purpose. The Levantine depictions in this shelter could be attributed to the middle phases of the regional sequence (Utrilla & Bea-Martínez Reference Utrilla and Bea-Martínez2007). The incised engravings at Cañada de Marco were first glimpsed during the recording of the site in the 1990s by Beltrán and Royo. They were first documented during the revision that was carried out in 2016 (Ruiz López et al. Reference Ruiz López, Royo Lasarte, Royo Guillén, Alloza Izquierdo, Uzal and Rivero Vilá2016), identifying three engraved areas underlying Levantine and Schematic pictographs.

Figure 1. (a) Cañada de Marco shelter, indicated by a white arrow; (b) Some of the team members during the campaigns at Cañada de Marco; (c) Los Borriquitos shelter at the head of the Mortero Ravine, indicated by a white arrow; (d) Waterfall at the head of the Mortero Ravine, focal point of a landscape with abundant rock-art sites, seen from Los Borriquitos.

Figure 2. 3D digital tracing of Cañada de Marco, indicating the location of the panels or sectors and of the engraved areas, which are surrounded by white dashed lines.

Los Borriquitos is a small rock-shelter located in Alacón (Teruel), included in the rock-art cluster at the head of the Mortero Ravine (Fig. 1c–d). In the decorated panel, there are 45 pictographs predominantly of Levantine style, most of them seriously damaged by natural weathering and flaking processes. The complex palimpsest formed by Levantine additions has not been studied in depth, but preliminary observations suggest that these pictographs could be attributed to the middle–late phases of the regional sequence. In our opinion, light red figures could be the older intervention in the panel, while black ones could be the more recent. Some Schematic-style pictographs were added in peripheral areas of the panel. The incised engravings at Los Borriquitos have been recorded by our team since 2017, showing a cross-overlapping sequence with Levantine pictographs. This shelter denotates a recursive symbolic usage over time, linked to the ritual location marked by the episodic waterfall of El Mortero ravine, and formed by other three rock-art shelters located around it. Repeated use of this shelter contrasts with the reduced available space and with its limited conditions for refuge.

Unfortunately, the limited protection against weathering provided by the overhangs of Cañada de Marco and Los Borriquitos is responsible for the poor preservation of the older surfaces on which the engravings were executed. Weathering of the incisions and of the pictographs of the later phases demonstrates that we are facing a long-term natural taphonomic process.

Methodology

These rock-art sites have been documented with a methodology specifically designed for the simultaneous recording of pictographs and very fine incised engravings. This was a challenge that allowed a methodological development which was subsequently improved in other sites (Rivero et al. Reference Rivero, Ruiz-López, Intxaurbe, Salazar and Garate2019). We have used the most advanced standards for rock-art recording, including photogrammetric 3D scanning, gigapixel imaging and macro/microphotography. Our purpose was to produce a highly detailed recording of the superimpositions, which at the same time could offer information about the technical features and marks of the incisions (Ruiz-López et al. Reference Ruiz López, Hoyer, Rebentisch, Roesch, Herkert, Huber and Floss2019).

The photogrammetric scanning was based on digital images captured with high-resolution DSLR cameras. Additionally, some macro-photogrammetric scans of the areas with engravings were carried out. Independent series of pictures were shot for recording pictographs and engravings. Illumination played a crucial role in this process because the correct light setting for pictographs did not allow an appropriate perception of the engravings. For this purpose, every group of engravings were illuminated with raking lights from directions that dramatically increased the visibility of these very fine lines. The documentation of the engravings was based on LED spotlights and flashguns, while for the pictographs LED spotlights were used with a high index of colour rendition (CRI >95%) and D50 illuminant.

These 3D models were processed and reconstructed with Agisoft PhotoScan and Metashape. Alignment between 3D models for pictographs and engravings was helped by common reference points. Independent high-resolution photographic textures were produced once the 3D models had been aligned and scaled. The digital tracings of the engravings were drawn in Adobe Photoshop on a Wacom tablet directly on the photographic texture of the 3D models. The photogrammetric high-resolution texture was used as well to obtain the digital 3D tracing of the pictographs, following methodology explained elsewhere (Ruiz López et al. Reference Ruiz López, Hoyer, Rebentisch, Roesch, Herkert, Huber and Floss2019). Finally, the different 3D models of every panel were merged, to produce unified digital tracings of pictographs and engravings. This procedure, although intricate, yields vastly superior results to other methodologies. Laser scanners have a greater geometric accuracy, and structured-light scanners might be more suitable for highly detailed recording of engravings, but they do not capture images appropriated for an accurate reproduction of rock-art paintings. Working directly on the texture derived from the 3D models ensures that the tracings will be placed in their exact position, avoiding the problems associated to unwrapping-based systems. The final rendering of the 3D tracings allows a simple visual understanding of the relationships between the support and the distribution of the figures, as well as how they are affected by weathering.

Gigapixel panoramas produced very high-resolution digital images derived from the stitching of hundreds of photographs. Pictures for gigapixel imaging were illuminated in a similar way to photogrammetric captures. Some of the photographic series were shot with polarized light and polarizer ring filter attached to the lens to enhance the visibility of pictographs by non-invasive and harmless procedures.

The series of microphotographs tried to analyse the relative seriation between engravings and pictographs. They were taken with a Lumos X-Loupe system with ×10–×30 magnification lenses. The setting was illuminated with the array of LEDs attached to the lens, that allows changes in the direction and intensity of illumination. These microphotographs were revised in situ with an iPad remotely connected by Wi-Fi to the camera. This system has a greater resolution and a better optical performance than other options such as Dino-Lite USB microscopes. Additionally, it can be easily attached to a tripod and a macro focusing rail for producing steady shots.

Results

Incised engravings in Cañada de Marco

The incised engravings recorded in this site are preserved in panels 1, 2 and 4, but most of them are concentrated in panel 1. Technically, most of these incised engravings are fine or very fine and probably they were carried out with a burin or with a flint blade producing incisions of different depths. They are very difficult to see because of the fine strokes, but also because the support is badly damaged by an extensive flaking process.

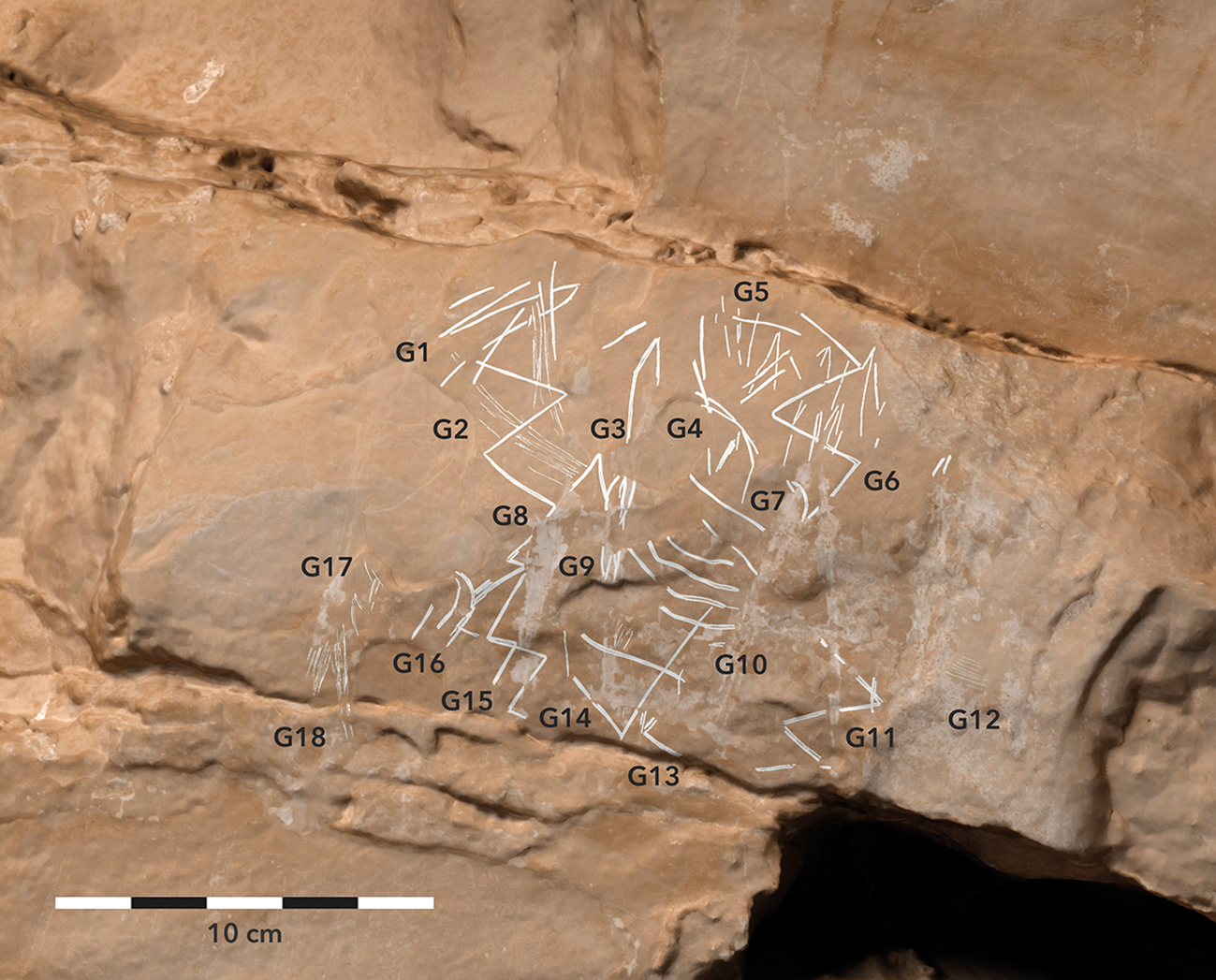

The distribution of engraved motifs in panel 1 is segmented into two zones, upper and lower. The upper zone (Fig. 3) includes geometric motifs, like vertical zigzags, some fusiform signs, and many loose strokes. The more remarkable one is G18, which is very similar to the legs of a figurative motif. Some of the incisions are deeply engraved and are not so patinated as the rest of the figures in the shelter, suggesting a younger age or at least that they have been less affected by taphonomic processes (Fig. 4).

Figure 3. Rendering of the 3D model of panel 1 of Cañada de Marco. Note that most of the semi-naturalistic and Schematic pictographs are overlying incised engravings (thin white lines). The numbers of the pictographs are indicated.

Figure 4. Detail view of the upper zone with engravings in panel 1 of Cañada de Marco, rendered from the 3D photogrammetric model. Note the differences between the very thin and the broader lines.

The lower part of the panel 1 is the more interesting in the shelter. Most of the engraved motifs are concentrated in this area (Fig. 5). They have serious conservation issues derived from an intense flaking process which is determining that engravings are currently preserved just on the surviving remains of the older surfaces. This long-term natural process is even older than the first engravings and is still active. Unfortunately, only two depictions are sufficiently complete to be identifiable, a remarkable male red deer [G25]Footnote 1 and an undetermined quadruped [G36], both oriented towards left. This panel should have included a high number of animal depictions judging by the parallel horizontal lines that can be interpreted as the remains of backs and bellies of at least three animal bodies [G28, G30 and G35]. These zoomorphic remains are accompanied with loose lines, fusiforms, a small reticulate and the remains of some extremely fragmented human figures [G20 and G33], even if this interpretation should be cautiously made due to their precarious preservation.

Figure 5. Digital tracing of the engravings preserved in the lower zone of panel 1 of Cañada de Marco. Most of the figures are deeply damaged by the weathered areas. In the lower box is shown the alternative reading of figures [G24] to [G26].

The stylistic features of panel 1 can be mainly deduced from the two recognizable animal depictions. The stag G25 has a higher degree of naturalism, including some anatomical details such as tail, ears or antlers, and a somewhat dynamic pose indicated by up-stretched front legs and raised head (Fig. 6b). Front legs are straight, without anatomical details or hooves, structured by convergent lines. Rear legs are missing. The body is elongated, slightly bent in the back to increase the dynamism. It has an infill formed by vertical and horizontal parallel lines. The head was represented with just one stroke, without indication of the snout. The markedly synthetic antlers are formed by single lines with several small strokes linked to the main beams. Two vertical lines crossing the body topped off by plumes of short convergent strokes could be arrows. The poor preservation of this figure allows an alternative reading, in which the described motif would be split into two figures (Fig. 5b). On the left, there would be a protome of a stag heading right, formed by an elongated head filled with parallel strokes, the chest, the upper part of the neck and the antlers. The rest of elements in the area would be a smaller animal formed by most of the body of the stag, with legs formed by the vertical lines, alternatively considered part of the arrows. Some minor differences in the strokes motivate this second hypothesis.

Figure 6. Detail views of the motifs [G20] (above) and [G25] (below), the most remarkable engraved depictions preserved in panel 1 of Cañada de Marco. Note how extremely fine incisions of both figures makes their identification very difficult in the images. Compare with Figures 3 and 5 for finding the engravings more easily.

The second zoomorphic figure [G36] is a more rigid depiction, with both pairs of legs stretched and connected to the body in a non-naturalistic way. The legs are formed by triangular structures without anatomical details, filled with multiple incisions. The body is elongated and rigid, with an outline produced by multiple lines and a hatched infill of clumsy lines. A vertical line topped off by a plume of short strokes could represent an arrow fixed to its back.

The presumed human figures recall Levantine-style archers, especially figure [G20] (Fig. 6a). The remains of this figure suggest an archer leaning forward, with an extended arm and an arrow. The broad bands of parallel lines would be the upper part of the legs. A curved line between the extended arm and the legs could be the remains of the bow. Some short parallel vertical lines could be interpreted as arrows. The upper part of the legs, body and arms were executed with a striated infill formed by multiple parallel lines. The poorly preserved figure [G33] could be the remains of the legs and body of another human figure heading left, that was executed with the striated infill technique.

Technical similarities between all these motifs suggest they were carried out in a single stage, except the aforementioned unpatinated strokes in the upper zone. Animal and human depictions were defined by very fine incisions carried out by single strokes of the tool forming juxtaposed bands of lines instead of deep grooves. The bodies are often filled with parallel lines. The definition of legs by means of groups of convergent lines is a typical feature of LUP styles, also used in the neck of stag [G25].

Some of these figures in the lower part of panel 1 underlie semi-naturalistic and Schematic-style pictographs, that are the last addition to this shelter. The complex microstratigraphy produced by the gradual weathering of the panel released fresh surfaces over time for engraving and for painting the semi-naturalistic [figs 24 & 29] and Schematic motifs overlying the incisions (Ruiz López et al. Reference Ruiz López, Royo Lasarte, Royo Guillén, Alloza Izquierdo, Uzal and Rivero Vilá2016). The semi-naturalistic figures are affected by the same flaking events as the underlying engravings, suggesting a shorter time interval between these two stages. Regarding Schematic pictographs, anthropomorphs [fig. 21], zoomorphic figures [fig. 19] and a cluster of dashes [figs 17, 18, 22, 23] are also affected by the flaking process, but less intensely than the rest of the motifs in the panel.

Three engraved figures are preserved in panel 2 (Fig. 7). The small deer is the best preserved engraved motif in this site [G37]. It is characterized by an elongated body, long legs in twisted perspective, progressively tapering towards endpoints without hooves. The head is small with a rounded snout and at least one antler; this is the worst preserved part of the motif. The short tail was indicated. The style is quite similar to the stag in panel 1, but with further elaboration and deeper grooves in the outline. The body is filled with very fine parallel incisions (Fig. 7c). This engraved deer has a mirror reflection in a painted Levantine-style protome, probably of a hind [fig. 85] (Fig. 7b). Some pictograph remains [fig. 84] of a poorly preserved motif overlap the engraved stag (Fig. 8). This engraved deer could be accompanied by another animal, but only a back line is preserved associated with some small strokes [G38].

Figure 7. Rendered views of the 3D model of panel 2 of Cañada de Marco. (A) Overview of the panel, showing the distribution of pictographs; (B) Detail of the group of engravings in panel 2. Note the disposition of [fig. 85] in relation to [G37] suggesting a mirrored composition; (C) Detail of the engraved deer of panel 2.

Figure 8. Photograph of figure [G37] showing the fine incisions of this motif. The dashed lines indicate the points where pictograph 84 is overlying [G37]. Note in the upper microphotograph (30×) how the scratches are filled with red colour paint that afterwards was patinated with a whitish calcite crust. In the centre of the lower microphotograph (10×) the red paint can be appreciated inside of the engraved line in the areas where the calcite crust has dropped.

Finally, in panel 4, there is a group of engravings, some of them with grooves broader than in the previous panels (Fig. 9). The main motif is formed by three convergent groups of long parallel lines which are connected to form a scalene triangle opened at the top [G40–G41]. A small fusiform composed by multiple parallel lines is located near to the large figure [G42]. Some loose incisions are located to the right [G43]. All these engravings are underlying the Levantine art motifs [114, 116 & 117], including at least two human figures (Fig. 10).

Figure 9. Rendering of the 3D model of panel 4 of Cañada de Marco. (A) Overview of the panel, including only Levantine pictographs. (B) Detail of the central area of the panel 4, indicating the area where engravings are underlying to Levantine pictographs. (C) Tracing of the engraved motifs in panel 4.

Figure 10. Microphotography (10×) of one of the points where the red paint of a Levantine pictographs is superimposed on the engraved vertical lines of motif [G41].

Incised engravings in Los Borriquitos shelter

The panel is deeply affected by a severe, long-lasting flaking process that damaged most of the engravings and destroyed many pictographs. Several groups of motifs are preserved in this small panel, distributed over 1 m in the non-flaked surfaces (Fig. 11). The number of superimpositions between pictographs is very high, reflecting long-term usage of this panel and the reduced available space in the shelter. The incised engravings were executed in the same area with fine and very fine incisions, which are really complicated to see. Their current distribution is deeply constrained by a large flaking that mutilated the central area of the panel. All the engravings are distributed around this massive flaking. Taking into account this taphonomic circumstance, the engravings are preserved in four groups generally underlying the pictographs, but not always.

Figure 11. Rendering of the 3D tracing of Los Borriquitos shelter. The dashed boxes indicate the location of the groups of engravings.

Group 1, in the upper part of the panel, includes several straight lines forming angles and two groups of short parallel lines, one of them probably part of a fusiform. This group is underlying a red-stained area and the remains of some small Levantine zoomorphic depictions (see Fig. 14a–b), which are presumably members of the first pictorial intervention in the shelter.

Group 2 of engravings is the largest of the shelter, including the longer and most visible incisions (Fig. 12). Nevertheless, it is not possible to identify specific motifs beyond intersecting lines, some angles and a group of very fine parallel incisions. While most of the incised lines are overlying Levantine pictographs, there are some deeply grooved lines that cut through a small light-red donkey of Levantine style. In consequence, the engraving technique was used between the successive layers of Levantine art (Fig. 13).

Figure 12. The palimpsest between engravings and pictographs in Los Borriquitos is extremely complex for groups 2 and 3 of engravings. The upper version is the rendering of the 3D tracing, including engravings and paintings, while in the lower one the pictographs have been hidden to reveal the incised engravings.

Figure 13. Macro- and microphotographs of the crossed superimpositions between pictographs and engravings in zone 2 of Los Borriqitos. Note at left, a donkey with raised head and ears. The engraved lines cut through the ears and snout, while at other points of the same line, it seems to be under the painting. These long vertical lines are clearly overlapping some pictographs (lower right, microphotograph 10×), but most of the engravings are underlying pictographs as shown in the upper microphotograph (10×).

In group 3 of engravings there are several criss-cross lines forming zigzag, or maybe a reticulate. They are badly damaged, making a more accurate description impossible. In this area can also be found two parallel lines. These incisions are all underlying some depictions of Levantine equids (Fig. 12).

Group 4 of engravings is located in the right part of the panel, near to the limit of a large flaking. Here there are just some straight lines intersecting each other, at angles, and most of them in an almost vertical orientation. These incisions are underlying the human and animal painted depictions (Fig. 14c–d).

Figure 14. Rendering of the digital tracings of groups 1 and 4 of engravings of Los Borriquitos. (A) Digital tracing of the incised engravings in group 1, with examples of striated fusiforms; (B) Pictographs located in the area with engravings of group 1; (C) Digital tracing of the incisions preserved in group 4; (D) In the area of group 4 there is a complex palimpsest of pictographs, all of them overlying the engravings.

The weathering process in this panel is equally affecting Levantine paintings and engravings, which makes it almost impossible to identify taphonomic events beyond that it started after the Levantine pictograph stages.

Analysis of seriation

One of the most striking aspects of these two sites is the high number of superimpositions between engravings and pictographs. This kind of massive overlapping is unusual in the area, forming complex palimpsests that denote a recurrent symbolic use of these two sites over long periods of time. The incised engravings in panels 1 and 4 of Cañada de Marco have very evident overlapping in which, even with the naked eye, it can be seen that paint filled the incisions. To the contrary, in panel 2 of this shelter and in Los Borriquitos direct observation led us initially to consider that the engravings were sometimes overlapping Levantine pictographs.

In the case of panel 2 of Cañada de Marco, the similarity between the colour of the fresh rock and of the calcareous accretion accumulated over these lines makes these engraved lines appear to be free of overlying paint. Microphotography has allowed us to observe the red colouration of the paintings under the crust filling the grooves of the engravings (Fig. 8).

In Los Borriquitos, there are some engraved lines which overlap Levantine pictographs and at the same time apparently underlie the same pictographs at other points, something obviously impossible. Meticulous microphotographic analysis allows us to conclude that these lines produced very shallow engravings that did not go deep into the limestone rock, leaving just a groove over the paintings. The increased pressure exerted with the tool at some points produced incisions that cut through both the paint and the outer layer of the rock (Fig. 13), evidencing that they were engraved over some pictographs. This circumstance has been observed exclusively over one figure corresponding to the phase of light-red pictographs, the older Levantine in this site.

Some of the geometric engravings in the upper part of zone 1 of Cañada de Marco show little accumulation of accretion, so they appear to be much more recent than the rest. Some of these engravings could correspond to Iron Age filiform engravings, with parallels in protohistoric sites such as Arroyo del Horcajo (Royo Guillén et al. Reference Royo Guillén, Arcusa Magallón, Rodríguez Simon, Lorenzo and Rodanés2020).

The seriation in both sites is quite similar, starting with an engraving phase that can be attributed to the Epimagdalenian. Afterwards, several Levantine pictograph stages were added. The superimpositions between Levantine pictographs are quite frequent in these two sites, but are much rarer over the Epimagdalenian engravings. In Los Borriquitos, some incised engravings were added over the older Levantine pictographs, indicating that this kind of very fine incised engraving was used by Levantine artists too. In both sites, the seriation culminates with semi-naturalistic and typically Schematic pictographs, which were arranged on the periphery of the Levantine painted panels, or occupied previously unpainted panels, as is the case in panel 1 of Cañada de Marco. The engraved upper part of sector 1 of Cañada de Marco could include additions more recent than the Schematic art.

Discussion

In the last years, the graphic assemblages produced around the Pleistocene-Holocene transition have increasingly attracted the attention of researchers. The renewed perspectives produced by discoveries in France, Italy, Spain and other European regions have consolidated the persistence of figurative art derived from Magdalenian beyond the traditional limits established by Breuil (Reference Breuil and Boyle1952) and Leroi-Gourhan (Reference Leroi-Gourhan1971). The examples attributed to French Azilian, and more recently to Laborien (Paillet & Man-Estier Reference Paillet, Man-Estier, Langlais, Naudinot and Peresani2014), opened up a path that was later followed by parietal and mobiliary art of the so-called Style V in northern Iberia (Bueno Ramírez et al. Reference Bueno Ramírez, de Balbín Behrmann and Alcolea González2007; Fábregas-Valcarce et al. Reference Fábregas-Valcarce, de Lombera-Hermida, Viñas-Vallverdú, Rodríguez-Álvarez, Soares-Figueiredo, Bueno-Ramírez and Bahn2015; García-Díez & Aubry Reference García-Díez and Aubry2002). Similary, decorated slabs of the Late Epigravettian (Dalmeri et al. Reference Dalmeri, Cusinato, Kompatscher, Kompatscher, Bassetti and Neri2009) and mobiliary items of Feddermesser-Maglemose cultures (Kabaciński et al. Reference Kabaciński, Hartz and Terberger2011; Veil et al. Reference Veil, Breest, Grootes, Nadeau and Hüls2012) have been connected to LUP graphic productions. The radiocarbon dates of these assemblages range between c. 11,800 and 9500 cal. bc. Figurative art survived and reached EM across Europe but experienced a marked reduction in comparison to the global figures for Magdalenian art. In our opinion, Levantine art was connected to this general trend in Europe, being one of the last graphic expressions evolved from the LUP assemblages. The evidence that has been found in Cañada de Marco and Los Borriquitos supports this hypothesis.

The figurative productions around the Pleistocene-Holocene boundary are characterized by simplified depictions of animals, with elongated and geometrically shaped bodies, frequently with small heads, and a reduced number of anatomical details. The bodies are usually filled with striated infillings or with geometric elements, producing a discontinuous pattern. Incised engraving is the most abundant technique on mobiliary items, but paint was used occasionally as well. Human figures are scarce, but there are some examples in quite simplified formats. There are some cave-art examples in Iberia (Corchón-Rodríguez et al. Reference Corchón-Rodríguez, Valladas, Pérez, Arnold, Tisnerat and Cachier1996; Fábregas-Valcarce et al. Reference Fábregas-Valcarce, de Lombera-Hermida, Viñas-Vallverdú, Rodríguez-Álvarez, Soares-Figueiredo, Bueno-Ramírez and Bahn2015), and probably in France too (Watté Reference Watté2011). Geometric patterns coexist with figurative themes in all these corpora. There are some particularities, like the barbed lines used in the contour of Laborien depictions, that reflect regional tendencies to increase diversity.

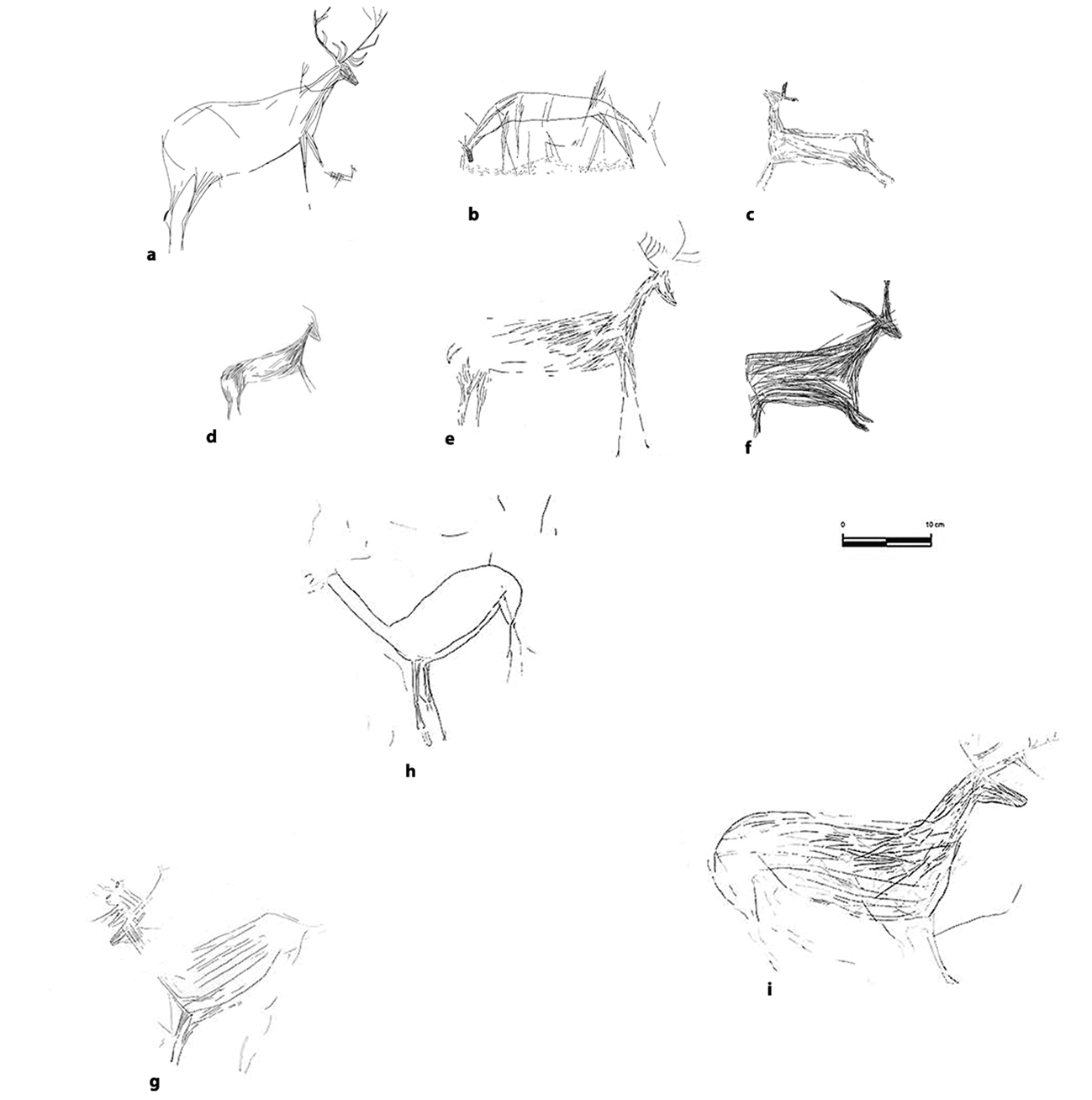

Epimagdalenian art is the Mediterranean Iberian version of this process. In a recent review (Domingo & Roman Reference Domingo and Roman2020), a solid connection was established with the final Upper Magdalenian art in the region, with a temporal context between c. 13000 and 9500 cal. bc (Martínez-Valle et al. Reference Martínez-Valle, Guillem-Calatayud, Villaverde-Bonilla and de Balbín Behrmann2009; Villaverde Bonilla et al. Reference Villaverde Bonilla, Román, Pérez-Ripoll, Bergadà and Real2012). It is known in mobiliary and rock art (Fig. 15), including animal depictions (hinds, stags, horses, aurochs, wild goats) with a tendency towards stylization, marked by elongated bodies and necks, very often with striated infilling, and few anatomical details. Geometric elements like line patterns, reticulates or zigzags are usually combined with figurative ones. The compositions in this art have been described as non-scenic, very often forming palimpsests. It was mainly executed with very fine engraved lines, coexisting with some examples of painted elements, both figurative and non-figurative. Three variants of animal depictions have been described depending on their degree of naturalism, which could coexist over time. It has been considered that the end of this tradition marked an abrupt rupture with any later rock-art assemblage, in parallel to the cultural changes reflected by the appearance of the notch and denticulate facies of the Mediterranean Iberian Mesolithic (Domingo & Roman Reference Domingo and Roman2020; Villaverde Bonilla et al. Reference Villaverde Bonilla, Román, Pérez-Ripoll, Bergadà and Real2012). In consequence, Levantine art is considered of Neolithic age by these researchers.

Figure 15. Map showing the current distribution of mobiliary and rock-art sites attributed to the Late Upper Palaeolithic in Mediterranean Iberia, a territory traditionally linked to Levantine art.

The engraved incisions in Cañada de Marco and Los Borriquitos are comparable in their technical and stylistic features to the Epimagdalenian rock art and mobiliary engravings, including the slabs from Molí del Salt (García Diez & Vaquero Reference García Diez and Vaquero2006), Sant Gregori (Fullola-Pericot et al. Reference Fullola-Pericot, Viñas-Vallverdú, García-Argüelles and Clottes1990; García Diez et al. Reference García Diez, Fontanals Torroja and Zaragoza Solé2002), or Filador (Fullola et al. Reference Fullola, Domingo, Román, García-Argüelles, García-Diez, Nadal, Bueno-Ramírez and Bahn2015) that have been archaeologically dated c. 12,000–10,000 bc. Most of the figurative motifs in these two shelters can be technically described as depictions formed by an outline with striated infillings, that was used equally in all figures independently of their naturalism. This technique was carried out with fine or very fine incisions, sometimes reiterated by parallel strokes, easily observable in some geometric motifs. Stylistically, the three best preserved zoomorphic depictions in Cañada de Marco [G25, G36, G37] are characterized by elongated bodies, small heads and legs without anatomical details, which are consistent with Epimagdalenian features (Fig. 16). These figures exhibit two slightly different stylistic variants. The more naturalistic one is exemplified by the stag [G25] of Cañada de Marco, with some details like ears or tail, while the antlers are synthetic. This figure has a similar pose to the stag engraved at Barranco Hondo that was considered of Levantine style (Utrilla & Villaverde Reference Utrilla and Villaverde2004), but it exhibits less naturalistic traits (Fig. 17a). The up-stretched front legs and raised head of the stag of Cañada de Marco instil dynamism in this depiction, similarly to the small engraved hind jumping from El Cogul, and one of the engraved stags of Parellada IV (Viñas & Sarriá Reference Viñas and Sarriá2010) (Fig. 17c–g). The deer [G37] is a more static depiction, with elongated body, shorter neck and legs unnaturally connected to the body. These features are closer to the hind of Barranco Hondo and the animals of Abric d'en Melià (Fig. 17b–e) (Guillem-Calatayud et al. Reference Guillem Calatayud, Martínez Valle and Melià Martinez2001). Motif [G36] was executed under less naturalistic canons, or we cannot identify naturalistic traits in the survival remains. The groups of parallel lines in the legs, neck and body recall the goat of Abric d'en Melià (Fig. 17d).

Figure 16. The three best preserved figurative motifs in Cañada de Marco have stylistic features concordant with Epimagdalenian art. The reconstruction (lower) of the rear legs of motif [G25] is based on Barranco Hondo (Fig. 17a), and the head is inspired by the examples from Abric d'en Melià (Fig. 17e).

Figure 17. Examples of Epimagdalenian figurative rock art. (a & b) Barranco Hondo (Utrilla & Villaverde Reference Utrilla and Villaverde2004); (c) Cogul (Viñas et al. Reference Viñas, Rubio, Iannicelli and Fernández Marchena2017); (d & e) Abric d'en Melià (Martínez-Valle et al. Reference Martínez-Valle, Guillem-Calatayud, Villaverde-Bonilla and de Balbín Behrmann2009); (f) Vale de José Esteves Rock 16 (Aubry et al. Reference Aubry, Dimuccio, Bergadà, Sampaio and Sellami2010); (g, h & i) Parellada IV (Viñas & Sarriá Reference Viñas and Sarriá2010), comparable to the figurative engravings from Cañada de Marco.

The presence of geometric elements is another typical feature of Epimagdalenian rock art and of the mobiliary art included in this style (Table 1). In Cañada de Marco and Los Borriquitos we have recorded zigzags, reticulates, fusiforms and parallel and intersecting lines.

Table 1. Epimagdalenian rock-art sites in eastern Iberia and painted and engraved imagery recorded in them.

Most of these features can be found in the nearer regions with LUP assemblages like Iberian Style V or Laborien. The Iberian Style V is distributed over the River Douro basin and northwestern Spain (Bueno Ramírez et al. Reference Bueno Ramírez, de Balbín Behrmann and Alcolea González2007; Bueno-Ramírez & Balbín-Behrmann Reference Bueno Ramírez, de Balbín-Behrmann and Bonet Rosado2016). It includes open-air sites and mobiliary art from Foz Côa (Fig. 14i), Siega Verde, Domingo García, and some cave art pictographs from Ojo Guareña (Corchón-Rodríguez et al. Reference Corchón-Rodríguez, Valladas, Pérez, Arnold, Tisnerat and Cachier1996) and Cova Eirós (Fábregas-Valcarce et al. Reference Fábregas-Valcarce, de Lombera-Hermida, Viñas-Vallverdú, Rodríguez-Álvarez, Soares-Figueiredo, Bueno-Ramírez and Bahn2015). Laborien and Style V share similar patterns of display, technique repertoire, stylistic features and species depicted. The chronological context is similar too, ranging between c. 11 500 and 9500 cal. bc. The hatched outline of some of the engraved depictions from José Esteves shelter, in Foz Côa (Portugal), has clear reminiscences with the barbed line contour of Laborien depictions. A similar technique was applied to the back of the deer in the Sant Gregori slab, currently ascribed to Epimagdalenian (Domingo & Roman Reference Domingo and Roman2020).

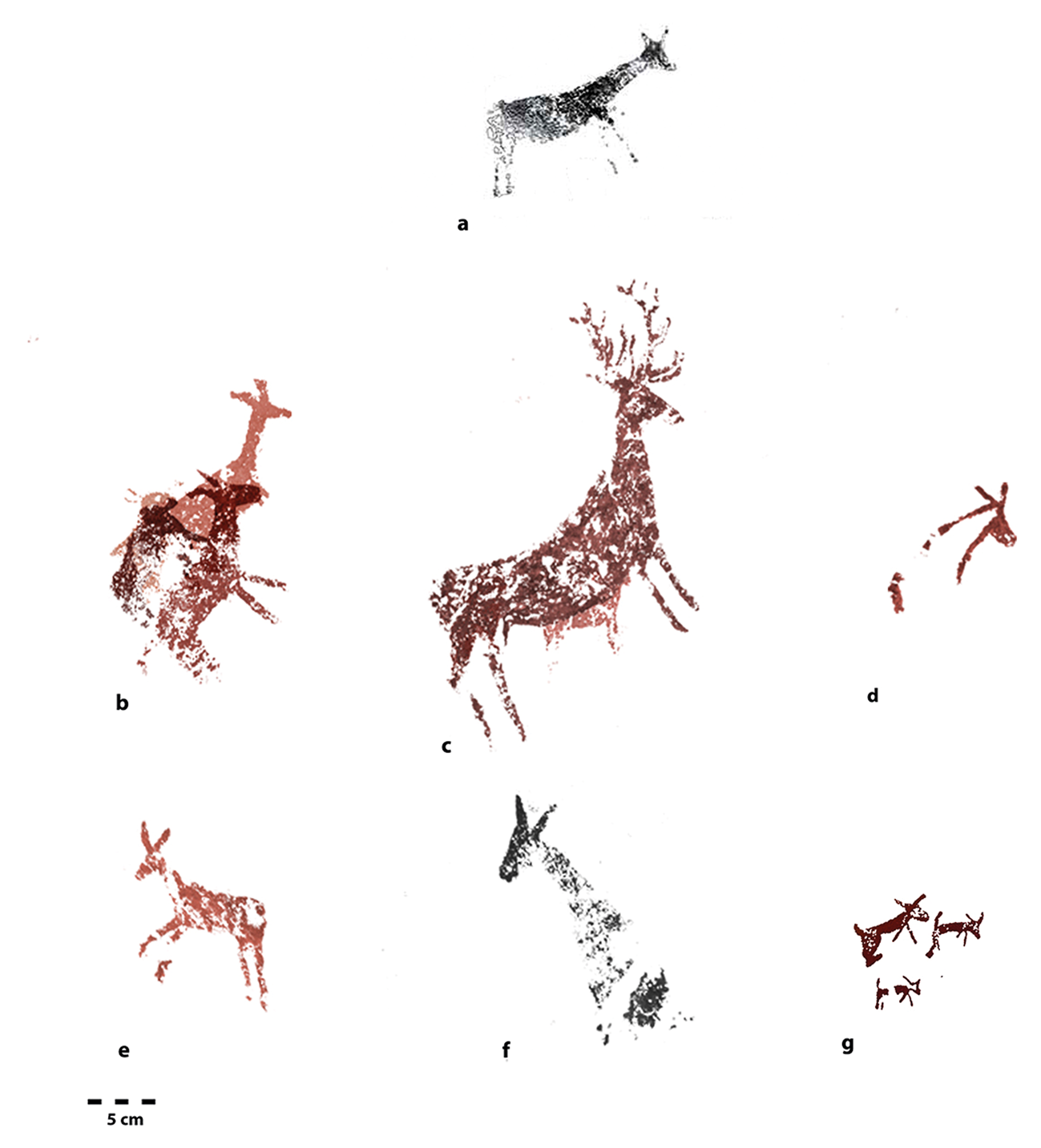

The engravings in Cañada de Marco and Los Borriquitos are good examples of these related traditions inherited from the Magdalenian that spread across Europe around the Pleistocene–Holocene transition and during the first centuries of the Holocene. This is a remarkable point that should be considered for the connections we have observed with the Levantine pictographs in these shelters. Epimagdalenian rock art is preserved in open-air sites located over the northern area of distribution of Levantine art, sharing the same landscape and kind of shelters. Incised engravings frequently coexist with pictographs in these sites; in 60 per cent of the Epimagdalenian rock-art sites, incised engravings share the panels with classic Levantine pictographs, and occasionally with semi-naturalistic and Schematic motifs. Martínez-Valle et al. (Reference Martínez-Valle, Guillem-Calatayud, Villaverde-Bonilla and de Balbín Behrmann2009) suggested an Epimagdalenian horizon for some pictographs in Bovalar cave, figures that share similar features with the engravings, otherwise similar to a myriad of Levantine pictographs (Viñas-Vallverdú et al. Reference Viñas Vallverdú, Rubio and Ruiz2010).

The probable identification of some human figures in Cañada de Marco has an immediate resonance in Barranco Hondo shelter (Guillem Calatayud & Martínez-Valle Reference Guillem Calatayud, Martínez-Valle, Utrilla and Villaverde2004), the only site with engravings of Levantine archers known up to now. Our interpretation of figure [G20] of Cañada de Marco as an archer firing a bow is inspired by the posture and broad thighs of some of the archers of Barranco Hondo [fig. 3 & 8] (Utrilla & Villaverde Reference Utrilla and Villaverde2004). This figure is comparable to many Levantine archers painted in Albarracín, other areas of Aragón, and all around the region with Levantine art (Fig. 18). The legs of the other motif [G33] that could fit into Levantine canons for human figures are comparable to archers 5, 6 and 7 of Barranco Hondo, again with many parallels in Levantine pictographs (Utrilla & Villaverde Reference Utrilla and Villaverde2004). The stylistic and technical similarities between engraved archers and animal depictions in Cañada de Marco suggest they are part of a single intervention, in which was maybe depicted a hunting scene, a typical theme of Levantine art. These connections are suggested as well by the arrows fixed to the bodies of figures [G25] and [G36], a typically Levantine feature (Fig. 17). Arrows have been described in Barranco Hondo, too (Utrilla & Villaverde Reference Utrilla and Villaverde2004). However, in contrast to the stag of Barranco Hondo, the animals engraved in panel 1 of Cañada de Marco are more similar to Epimagdalenian depictions in mobiliary and rock art.

Figure 18. Tracing of figure [G20] from panel 1 of Cañada de Marco, and hypothetical reconstruction of the archer (a). Stylistic parallels for this archer are frequent: (b) Bichrome Levantine archer from Coves del Civil (Tírig) (by J. Cabré); (c) Archer from Hoya de Navarejos II (Albarracín) (by J.F. Ruiz); (d) Archer from Barranco Hondo (Utrilla & Villaverde Reference Utrilla and Villaverde2004). Examples (b) and (c) are figures with similar body structures, reflecting a motion linked to shooting a bow. Example (d) has a strong similarity in the structure of the legs, following typical canons of Levantine art.

Some of the authors who reject any possible connection between LUP art and Levantine art paradoxically accept that Barranco Hondo was Levantine due to the presence of some engraved Levantine archers in a panel that otherwise would have been described as Epimagdalenian (Utrilla & Villaverde Reference Utrilla and Villaverde2004). The presence of human figures that fit into several of the more classical types of Levantine archers led them to postulate this exception to their norm, which considers that Levantine art started during the Neolithic after a long hiatus since Epimagdalenian (Villaverde Bonilla et al. Reference Villaverde Bonilla, Martínez-Valle, Guillem-Calatayud, López-Montalvo, Domingo-Sanz, Arranz, Giraldo and Nash2011). This contradiction has been sustained by the consideration of Barranco Hondo as a cumulative scene produced by the addition of engraved Levantine archers of different typologies to a supposedly pre-existent Epimagdalenian animal group (Domingo & Roman Reference Domingo and Roman2020). However, it does not seem a plausible hypothesis because according to their proposals there is a temporal gap of at least five millennia, and a deep cultural rupture which does not fit with this technical similarity. It would be really exceptional that the only engraved Levantine archers known up to now, and supposedly of Neolithic age, would have been executed in one of the very few panels with Epimagdalenian engravings, considering that there are nearly a thousand Levantine sites with pictographs and just 12 parietal Epimagdalenian sites. In our opinion, the re-cycling of pre-existent figures to compose an engraved Levantine scene would demand a continuity between both symbolic codes that is suggested by the evident technical and thematic similarities. Additionally, recursivity of this engraved panel requires maintaining knowledge of the location of the site, an important point considering the small size of the Barranco Hondo panel and the poor visibility of these very fine incised figures. The continuity we are proposing for Barranco Hondo would be confirmed by the coexistence of Levantine archers with Epimagdalenian-style animals in Cañada de Marco.

Another significant continuity between the Epimagdalenian engravings and the pictographs in Cañada de Marco is located in sector 2. The head of the incised stag in this panel [G37] is reminiscent of the hind of Barranco Hondo and the stags of Parellada IV (Viñas & Sarriá Reference Viñas and Sarriá2010), evidencing its connections with Epimagdalenian conventions. However, this figure could be mirrored by [fig. 85], a painted hind of a similar size that was placed at the same height in the panel (Fig. 7b). These two figures could be forming a scene with two animals of similar format moving in an opposite direction, a theme found in some Levantine sites such as La Saltadora (Domingo Sanz et al. Reference Domingo Sanz, López Montalvo, Villaverde Bonilla and Martínez Valle2007), Val del Charco de Agua Amarga (Beltrán Martínez Reference Beltrán Martínez2002) or Mas dels Ous (Fig. 19). In this case, the pictograph could be mirroring the older engraving, evidencing once more the continuity between these graphic expressions. This painted protome is comparable to the pictograph that has been proposed as Epimagdalenian in Cova del Bovalar (Martínez-Valle et al. Reference Martínez-Valle, Guillem-Calatayud, Villaverde-Bonilla and de Balbín Behrmann2009), but similar figures can be found as well in Cañada de Marco, or in other Levantine shelters in the River Martín region, such as in Los Encebros shelter (Beltrán Martínez & Royo Lasarte Reference Beltrán Martínez and Royo Lasarte2005) (Fig. 20).

Figure 19. Animals opposed by their hindquarters are not very common in Levantine art, but there are some examples nearby to River Martín area, which can be compared to the two animals from panel 2 of Cañada de Marco in compositional principle: (a) La Saltadora IX (Domingo-Sanz et al. Reference Domingo Sanz, López Montalvo, Villaverde Bonilla and Martínez Valle2007); (b) Mas dels Ous (unpublished, by J.F. Ruiz); (c) Val del Charco de Agua Amarga (Beltrán Martínez Reference Beltrán Martínez2002).

Figure 20. Some painted figures from Cova del Bovalar have been attributed to Epimagdalenian art (a) (Martínez-Valle et al. Reference Martínez-Valle, Guillem-Calatayud, Villaverde-Bonilla and de Balbín Behrmann2009). The stylistic characteristics of this figure, with elongated body and neck, triangular head, ears in V, or short legs can also be found in many pictographs considered of Levantine style in the River Martín, from Cañada de Marco (b, c & d) (Ruiz López et al. Reference Ruiz López, Royo Lasarte, Royo Guillén, Alloza Izquierdo, Uzal and Rivero Vilá2016); Los Borriquitos (e & f) (by J.F. Ruiz); or Los Encebros (g) (Beltrán Martínez & Royo Lasarte Reference Beltrán Martínez and Royo Lasarte2005).

The interstratification between engravings and pictographs in Los Borriquitos is another evidence of the continuities between Epimagdalenian and Levantine arts. The technique of incised engraving was not very usual, but it was known by Levantine artists (Martínez-Bea Reference Martínez-Bea, Utrilla and Villaverde2004). Engraved outlines in Levantine painted animal depictions have been unequivocally identified in Roca dels Moros (Viñas et al. Reference Viñas, Rubio, Iannicelli and Fernández Marchena2017) and La Coquinera (Martínez-Bea Reference Martínez-Bea, Utrilla and Villaverde2004), and in different rock-art sites around Albarracín like Barranco de las Olivanas and Cocinilla del Obispo, among others (Martínez-Bea Reference Martínez-Bea, Utrilla and Villaverde2004). Therefore, the engraving technique was not strange to Levantine artists in the Aragonese region.

One of the most interesting aspects of Cañada de Marco and Los Borriquitos is the recursive usage of the panels, starting during the last stages of LUP with parietal engravings and probably finishing around the Chalcolithic period in which most of Iberian Schematic art was carried out. In Cañada de Marco, it is especially significant that Levantine pictographs are only involved in superimpositions with engravings in panel 4. The rest of the engravings are underlying some undefined remains in panel 2, and semi-naturalistic and Schematic pictographs in panel 1. This distinct arrangement suggests some kind of respect from Levantine painters towards the panel with engravings, surely because they were still understandable and assimilable to their own graphic productions, maybe as older stages of this tradition. The pair of mirrored figures proposed in panel 2 points in the same direction. On the contrary, the authors of Schematic paintings freely used the panel where the engravings, already deteriorated at the time, were preserved. A different agency is detected in Los Borriquitos, where Levantine paintings massively overlapped the engravings until they were almost hidden. This behaviour was probably derived from the scarcity of surfaces suitable for painting in this small shelter, that similarly led to the reiterated superimposition between Levantine pictographs in some areas (Figs 10A & 11D). The engravings overlying Levantine pictographs in Los Borriquitos demonstrate that this technique was included in the technical repertoire of Levantine art. The painters of Schematic art respected the central panels in both shelters, adding their pictographs around the areas previously used by Levantine artists, trying to avoid superimpositions with Levantine pictographs, but not with the engravings in panel 1 of Cañada de Marco. In any event, this demonstrates the nature of ‘accumulative panels’ (Sebastián-Caudet Reference Sebastián-Caudet1986) of both shelters perpetuating the rituality of both sites with the addition over time of different styles. These continuities observed in Cañada de Marco between the engravings stage and the Levantine pictographs, in contrast to the dichotomy observed with Schematic art, could be an additional argument that blurs the contrast between LUP and Levantine art.

This accumulation of connections would not be understandable without maintaining the use of a common symbolic landscape based in rock-art sites of long duration and similar forms of occupation and exploitation of the territory by LUP and EM hunter-gatherers. In light of these findings, the alleged hiatus between the very last stages of Palaeolithic art and Levantine art loses much of its credibility, allowing vindication of old theories that already postulated the absence of such hiatus (Beltrán Martínez Reference Beltrán Martínez2002). Our arguments converge with others posed by Bueno Ramírez et al. (Reference Bueno Ramírez, de Balbín Behrmann and Alcolea González2007; Reference Bueno Ramírez, de Balbín-Behrmann and Bonet Rosado2016), Viñas-Vallverdú et al. (Reference Viñas Vallverdú, Rubio and Ruiz2010) or Mateo Saura (Reference Mateo Saura and Viñas i Vallverdú2019), among others, who suggested that Levantine was carried out by the last hunter-gatherers in the Iberian peninsula. The evidence in the two sites studied in this paper is probably among the strongest to suggest that Levantine art evolved directly from Epimagdalenian, at least since the EM, which means that this style may represent a continuous development of a long hunter-gatherer tradition. The similarities in format, technique, patterns of display, conventions, territory and landscape usage support this hypothesis.

The symbolic world of the hunter-gatherers of the last stages of LUP, mainly characterized by animals and geometric elements engraved in parietal and mobiliary items, would be preserved in the Levantine art tradition, principally painted, but with early stages that included incised engravings too. The graphic assemblage of Levantine art constituted by the depiction of humans and animals, and probably some geometric elements (Ruiz-López Reference Ruiz-López and Grünbergn.d.), shared a significant part of the symbolic codes of the LUP and EM expressions across western Europe (Zvelebil Reference Zvelebil, Whallon, Lovis and Hitchcock2011) but evolved differently with a progressive growth of the human figure and the representation of their activities. The increase of the regional diversity from the common roots in LUP could similarly be observed in western Iberia, where figurative rock art continued evolving in the Mesolithic traditions documented in the Tagus and Guadiana valleys (Collado-Giraldo Reference Collado Giraldo2006; Gomes Reference Gomes2007), and in some aspects, a similar process could have happened in the Île-de-France region, in this case emphasizing the geometric component (Guéret & Bénard Reference Guéret and Bénard2017). The exceptionality of Levantine art in European prehistory may derive from its more direct affiliation with the Palaeolithic heritage that survived until at least the Early Neolithic, flourishing in hundreds of sites when many of the traditions derived from LUP were languishing or had disappeared in the rest of the continent.

Conclusion

The discovery of new incised engravings in open-air shelters in the River Martín rock-art cluster, an area with many Levantine and Schematic sites, extends the region where this kind of engraving has been found up to now in Mediterranean Iberia. The technical and stylistic features of the engravings are perfectly coherent with those observed in mobiliary items attributed to Epimagdalenian art, and with those of other LUP art assemblages. For this reason, we consider that the engravings of these two rock-art sites should be included in the last stages of the LUP, a remarkable fact, given the alleged scarcity of this type of rock art in Europe.

In Cañada de Marco and in Los Borriquitos, despite its high level of deterioration, we have discovered a significant number of incised engravings including zoomorphic depictions, some geometrics and the probable remains of some human figures. Animals and signs are very frequent in the sphere of these late-glacial symbolic expressions, but the anthropomorphs necessarily refer to Levantine art. This is a crucial event because we could be witnessing in these sites the encounter between two graphic expressions that many authors have considered completely unrelated and separated by a cultural and temporal abyss of several millennia.

On the contrary, the research we have carried out on a significant amount of evidence in these two sites, including technical and thematic continuities, and the differentiated agency exerted through recursivity by Levantine and Schematic painters towards the Epimagdalenian engravings, leads us to pose the hypothesis that Levantine art could have evolved directly from Epimagdalenian art. In consequence, this may mean that Levantine art is rooted in a very long-lasting visual culture uninterruptedly maintained by hunter-gatherer groups over the Upper Palaeolithic. If our hypothesis is correct, it would support recent investigations at a European scale that reject the ruptures in the figurative graphic record at the end of the Upper Palaeolithic.

Filling the void between LUP art and Levantine art is a remarkable contribution as well for the intense debates around the origin of this last style. If our hypothesis is correct, the engraved animals with arrows hitting their bodies and at least one archer firing them, the mirror-image composition and the recursivity in the use of panels and sites indicate the ties and the confluences between the very last stages of the Palaeolithic cycle and the earliest of the Levantine one. When exactly LUP Epigmagdalenian art transformed or evolved into Levantine art is still an open question, but the chronology of the Epimagdalenian suggests, cautiously at least, an Early Mesolithic framework for the nascent Levantine art. In the future, we hope to verify this hypothesis, and as far as possible, consolidate it with direct and indirect dating which could yield a more precise temporal framework for Mediterranean Epimagdalenian art and the early stages of Levantine art.

The recurrent association of Epimagdalenian engravings with Levantine pictographs in the core area of one of the traditional territories of this last style suggests that the last foragers in Mediterranean Iberia maintained similar symbolic, social and economic uses of the territory to their ancestors until their disappearance. The irruption of Neolithic technology and lifestyles provoked evident changes in the symbolic sphere and in the use of the territory that are manifested in the progressive consolidation of Iberian Schematic art, with all of its variants, and the new production systems. However, it did not completely change the preceding ideological system which somehow was preserved in rock-art sites like Cañada de Marco and Los Borriquitos, and in many others in Mediterranean Iberia, with astonishing levels of symbolic perseverance until historical times, demonstrating that symbolic systems can survive profound changes in economic systems, and thus evolve independently. Thus the symbolic landscapes of the LUP were maintained through the Mesolithic by the last foragers that produced the Levantine art, a tradition of long duration that fills a void in a period of European prehistory which has not been done justice in many respects, especially in terms of appreciation of its graphic expressions.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Nerea Ardébol, Paula Hernaiz, Irene Serrano, María Olmedilla, Carolina García and David Moreno for collaboration during the fieldwork, and especially the contribution by our colleague José M. Pereira, who was in charge of capturing and processing gigapixel images from Cañada de Marco. And finally, we would like to express our gratitude to the supportive advice of reviewers that has noticeably contributed to improving our manuscript. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports of Spain in 2015 and 2016, and the Regional Government of Aragon.