Introduction

This paper explores the relationship between irrigation canals, the Andean concept of tinku (the coming together of two parts to create a whole), the importance of liquids, and the circulatory nature of time in the Moche world. I contend that canals acted as tinku—they united and divided physical space both socio-politically and temporally. The water running through the canals, and liquids in general, served as animating forces in Moche society. Netherly's (Reference Netherly1984) case study on political organization in the Chicama Valley prior to Spanish arrival in 1532 shows that, like the Inca, the late pre-Hispanic Chicama Valley was composed of moieties with fractaline political authority, meaning that at any scale, any part of the political system has the same underlying structure as the whole system. The irrigation canals and the Chicama River acted as boundaries and delineated the lands of these moieties. Here I argue this was also the case centuries earlier in Moche times.

I use as a case study the Moche site Licapa II, a midsized ceremonial centre in the Chicama Valley. Licapa II consists of two adobe brick platform mounds, known as huacas, separated by an irrigation canal. Each side of the canal is characterized by distinct material culture and activities. Furthermore, the construction periods of the huacas date to different phases—one side pre-650 ce and the other post-650 ce. Drawing on the Quechua concept of tinku, or the coming together of two parts to create a whole, I suggest that the canal served both to divide and to unify ritual and socio-political space physically and temporally. I also contend that the water running though the canal and that liquids in general—blood, urine, semen, corn beer, etc.—were vital to the society's energetic flow. Ultimately, I suggest that Licapa II can be viewed as a microcosm, or synecdoche, of valley-level organization. Allen (Reference Allen and Howard-Malverde1997) defines synecdoche as a figure of thought, where the whole is enveloped as a part of the larger whole, much like fractals in geometry or nested Russian dolls.

Because the Moche had no writing systems and what survives of ancient north coast languages is fragmentary, to elucidate Moche worldview I turn to Spanish chronicles, colonial-era documents and ethnohistoric and contemporary Quechua- and Aymara-language accounts from the highlands. Concepts and traits extracted from these works paint a rich picture of life just prior to Spanish contact. Inca archaeology greatly benefits from this knowledge, and years of fieldwork provide examples of how many of the concepts were manifest on the physical landscape (Bauer Reference Bauer1998; Zuidema Reference Zuidema and Decoster1990). However, both the antiquity of specific Quechua and Aymara terms and ideas, as well as the relevancy of applying these terms and ideas to interpret the archaeological record of much older and geographically distant cultures like the Moche, present ongoing questions.

Here I evaluate if some Inca and highland Andean concepts understood from Quechua and Aymara sources were operating centuries earlier on Peru's north coast during Moche times (200–850 ce). I draw on concepts centring on geographic features that connect and are common to highland and coastal regions (mountains, rivers and canals). This approach is distinct from other readings of Moche imagery and archaeology that import Quechua/Aymara narratives to verify specific interpretations of images (Hocquenghem Reference Hocquenghem1987; Sánchez Garrafa et al. Reference Sánchez Garrafa, Casas Salazar and Dolorier Torres2012). My approach uses the archaeological record to inform and test the applicability of the concept, rather than accepting that all Andean concepts were universally appropriate in Moche times.

The Moche and their language

Archaeologists recognize the Moche phenomenon by common artifact and architectural styles that extended over 10 contiguous coastal valleys. Moche culture is characterized by decorated huacas,Footnote 1 wealthy elite burials and exquisite ceramics. Moche is also understood by a series of ritual practices that took place at huaca complexes. Detailed realistic, fine-line drawings on ceramic vessels depict these practices.

Scholars once believed that the Moche were a homogenous polity, as proposed by Rafael Larco Hoyle (Reference Larco Hoyle1945), the father of Moche studies. Research at Moche sites in the 1990s led scholars to realize instead that Moche consisted of at least two major cultural regions—one in the north and one in the south—with the large Pampa de Paiján desert dividing the two (Fig. 1). These two regions are characterized by different ceramic and architectural styles (Castillo & Donnan Reference Castillo, Donnan, Uceda and Mujica1994).

Figure 1. North Coast of Peru.

A refined chronology and better understanding of regional associations among and between sites allows for new interpretations of how socio-political relations may have developed and been negotiated. Many scholars now contend that the Moche area was subdivided into independent polities whose alliances cross-cut the northern and southern regions (Castillo & Donnan Reference Castillo, Donnan, Uceda and Mujica1994; Castillo et al. Reference Castillo, Fernandini and Muro2012; Castillo & Uceda Reference Castillo, Uceda, Silverman and Isbell2008; Quilter & Koons Reference Quilter and Koons2012).

The archaeology of Moche has made significant strides over the last three decades, yet many archaeologists pay only cursory attention to the Moche language(s). This is mainly due to a lack of material evidence, such as writing systems. However, it is significant that two major languages were spoken in what was the Moche region prior to the Spanish arrival: Quingnam in the south and Mochica in the north. Both are now extinct and their antiquity unknown, but fragmentary evidence from various sources allows us to make some linguistic and geographical reconstructions (Calancha Reference Calancha1638; Carrera Reference Carrera1644; Cerrón-Palomino Reference Cerrón-Palomino1995; Middendorf Reference Middendorf1892; Salas García Reference Salas García2002; Urban Reference Urban2019). One reconstruction shows that they overlapped in the northern part of the Chicama Valley—near the archaeological site of Licapa II—and where we observe the frontier or boundary in material differences between the northern and southern Moche regions (Netherly Reference Netherly and Christie2009; Fig. 2). Although it is compelling to think that the linguistic divide corresponds to the material divide in Moche times, more interdisciplinary research is needed.

Figure 2. Chicama Valley polity divisions during the late pre-Hispanic era as derived from Netherly (Reference Netherly1984), Ramírez (Reference Ramírez1995) and Clément (Reference Clément2015). The canals shown here are modern canals that were in use in the pre-Hispanic era and abandoned ancient canals that are currently seen on the landscape. The canals were digitized from satellite imagery and checked with Netherly's (Reference Netherly1984) maps. The sites in the valley with Moche V materials and the Mochica/Quingnam language boundary are also noted.

Languages carry with them perceptions of reality and the ordering of the world. Even if certain words are translatable across languages, the concepts they embody do not always hold the same meaning (Mannheim & Salas Carreño Reference Mannheim, Salas Carreño and Bray2015). Yet regardless of language, many concepts were probably mutually understood by coastal and highland people quite early. Camelid pastoralism and agricultural exchange between vertical ecozones pre-dates 3000 bce, and recent genetic modelling shows gene flow between the northern coast and highlands by at least the Moche period (Nakatsuka et al. Reference Nakatsuka, Lazaridis and Barbieri2020). Because of prolonged interactions, pre-contact-period people understood and spoke various languages. This is substantiated by shared vocabulary between coastal languages and adjacent highland languages, such as Culli (Urban Reference Urban2019). It also includes the borrowing of Quechua words into Mochica after 700 ce (Beresford-Jones & Heggarty Reference Beresford-Jones, Heggarty, Heggarty and Beresford-Jones2012; Lau Reference Lau, Heggarty and Beresford-Jones2012). Intense connections between the coast and highlands led to shared ontologies concerning physical features of the Andean landscape, explicitly rivers and mountains.

Andean worldview in the highlands and north coast

In order to understand a Moche mindset better, it is useful to draw on what we know about an Andean worldview from highland Quechua and Aymara sources. Dualism is embodied in a number of conceptual ideas that shaped Andean thought. Binary pairs such as male/female, sun/moon, sky/earth, mountain/valley and wet/dry are complementary and oppositional (Gelles Reference Gelles1995; Platt Reference Platt, Murra, Wachtel and Revel1986; Zuidema Reference Zuidema and Decoster1990). These pairs, referred to as yanantin in Quechua and meaning ‘to serve together’, can be symmetrical and ranked equally or asymmetrical and ranked unequally (Platt Reference Platt, Murra, Wachtel and Revel1986). For example, the male/female pair is complementary but asymmetrical since male ranks slightly higher than female. Two opposed pairs coming together to form a whole was essential to a functional society and is embodied in the concept of tinku.

In Quechua, as well as Aymara, the noun tinkuy means ‘binding or meeting’ (Cereceda Reference Cereceda, Bouysse-Cassagne, Harris and Platt1987). As a verb, it is translated to ‘encounter or come together’. This ‘coming together’ is to achieve balance (Gelles Reference Gelles1995). In this respect, tinku refers to any two parts that come together to make a whole. Examples include the confluence of two rivers, the seam holding two pieces of cloth together, the uniting of two separate channels of the stirrup-spout bottle into one, or the way a single irrigation canal joins two parcels of land (Burger Reference Burger1992; Netherly & Dillehay Reference Netherly, Dillehay, Sandweiss and Kvietok1986; Ossio Acuña Reference Ossio Acuña1992; Quilter Reference Quilter2010). This balance also relates to the concept of ‘the centre’. Unlike Western thought where the centre is a single point, in the Andes the centre refers to a line where two sides meet and is defined by what is on either side (Gelles Reference Gelles1995, 715).

The layout of highland Andean communities in upper and lower components is a manifestation of tinku. In Inca Cusco, this division was both horizontal (hanan to the north and hurin to the south) and vertical (hanan is physically above hurin). Gose (Reference Gose1996) notes that there was also a temporal component to this division, as space and time were merged in highland Andean thought, a concept known in Quechua and Aymara as pacha (Allen Reference Allen1998; Bouysse-Cassagne & Harris Reference Bouysse-Cassagne, Harris, Bouysse-Cassagne, Harris and Platt1987; Qespi Reference Qespi1994). In the Inca king lists, the first five rulers are assigned to Lower Cusco, where the more recent were ascribed to Upper Cusco. Gose (Reference Gose1996) suggests that the rulers in the later part of Inca society literally looked down the hillside and back in time to their ancestors. Furthermore, Dean (Reference Dean2007) suggests that tinku also operated to bring the unordered realm of nature together with that of the ordered world of the Inca. She argues that the incorporation of rock outcrops into Inca buildings is the visual evidence of this coming together.

The term tinku today is synonymous with ritual battles fought between the upper (male) and lower (female) moieties—known in Quechua and Aymara as ayllus—in Andean communities, both in the pre-Hispanic past and present (Platt Reference Platt1987). The purpose has been interpreted as “symmetric justice” or “equilibrium wars” that served to bring balance to society and foster fertility (Gelles Reference Gelles1995; Platt Reference Platt1987). These ritual battles remain a key factor in political negotiations today. In her study on ritual battles during colonial and more contemporary times, Hopkins (Reference Hopkins1982) notes that the main objective is to shed blood. The blood nourishes pachamama (mother earth) to ensure a good harvest.

There is fluidity and a dialectic nature to tinku. The ‘coming together’ is often a forceful or violent collision between two opposing forces. This union results in synthesis and the creation of something new. For example, when men and women come together a baby is formed, or when two small streams collide a bigger, more powerful river results. Likewise, bloodshed in tinku battles renews societal order. Liquids are vital in all these unions, and this intimacy between tinku and fluids underscores the larger role fluids played in Andean society.

In Inca times and today, liquid in various forms (e.g., water, blood, corn beer, urine, semen, etc.), and especially the circulation of liquid, was essential to the fertility of living beings and the earth (Cummins & Mannheim Reference Cummins and Mannheim2011; Sikkink Reference Sikkink1997). This circulation was linked to mountains and their prominence in Andean worldview. In many ethnohistorical accounts, the mountain is associated with the erect penis of a male, whereas the valley bottom, and the river running through it, is seen as a woman's vulva (Bastien Reference Bastien1978). The recycling of liquids (semen/water) through the system—from mountain top to valley bottom, from male to female—represented the fertilizing effects of liquids and was and is a key belief in Andean religion (Bastien Reference Bastien1978).

A Quechua term that is relevant to this ritual feeding or offering is t'inkay, which means to ‘sprinkle or libate’. Not to be confused with tinku,Footnote 2 t'inkay is a physical gesture where liquid is sprinkled or spilled onto the earth. The gesture is often enacted in a ritual context to ensure fertility and restore to the mountains the fluids that were spent during the rainy season (Gose Reference Gose1994). A series of rituals involving this physical gesture—known as t'inka rituals—are enacted in modern-day Huaquirca (Gose Reference Gose1994). The t'inkas involve heavy drinking, offerings of corn beer and blood sacrifice to mountain deities to promote agricultural and animal fertility.

Time, like liquid, in Andean thought can also be characterized in this circulatory nature. In non-literate societies, the passing, or flow, of knowledge through oral tradition took on a circulatory nature as it was handed down, recited and repeated throughout the generations (Howard-Malverde Reference Howard-Malverde1990; Swenson & Roddick Reference Swenson and Roddick2018). The circulation of and privileged access to this knowledge was the source of power held by the ancestors (Kelly Reference Kelly2017). To sustain the connection to the knowledge source and legitimize the acts of their progeny in the present, ancestors remained a part of the living world. They were memorialized as part of the living landscape and continuously revitalized though sustained sacrificial offerings by their descendants. Thus, the physical landscape and time (past and present) were fused and inseparable (pacha), and the living commingled with and tended to the dead with offerings of food and, especially, drink.

Thus, integral to a highland Andean worldview was the flow of both liquids and time. Whether it be water though an irrigation canal, corn beer at ceremonies or knowledge though ancestors, circulation had real implications for politics past and present.Footnote 3 Canals, rivers and flowing springs delineated the lands of different social and political groups throughout the Andes in the past and today (Bray Reference Bray2013; Sherbondy Reference Sherbondy1982). As the landscape was alive with the ancestors, sustaining the flow was a necessity for the well-being of all.

Shifting attention to the north coast, much like the ayllu system in the highlands, dualistic or bipartisanship organization was also in place there prior to Inca and subsequent Spanish conquest (Netherly Reference Netherly1984; Rostworowski de Diez Canseco Reference Rostworowski de Diez Canseco, Moseley and Cordy-Collins1990). The indigenous Chicama Valley population was organized into a series of polities, known as repartimientos. The best documented were the Chicama and Licapa repartimientos. Each repartimiento contained ranked and nested moieties known in Spanish as parcialidades, translated to ‘part of a whole’ (Netherly Reference Netherly1984; Reference Netherly, Moseley and Cordy-Collins1990; Ramírez Reference Ramírez1995; Reference Ramírez1996). At the top of the social hierarchy was the paramount lord, who was responsible for the entire repartimiento and the higher-ranking parcialidad (Fig. 3). A second person was in charge of the lower-ranking parcialidad. Under the paramount lord and the second person were a series of lower-level lords. At the lowest level, the population was grouped by economic specialization (Netherly Reference Netherly1984).

Figure 3. Moiety division and hierarchy of the Chicama Valley in 1565. (After Russell & Jackson Reference Russell, Jackson and Pillsbury2001, 162; based on Netherly Reference Netherly1984, table 1).

Numerous colonial-era documents from the Chicama and Licapa repartimientos relate to irrigation (Caramanica Reference Caramanica2018; Netherly Reference Netherly1984; Ramírez Reference Ramírez1995).Footnote 4 Canal management was organized on the system of nested hierarchies of socio-political control (Fig. 4). I contend that the canals acted as tinku: they physically brought together different moieties on the landscape. The life-giving water circulating through these canals was vital to their role not only in agricultural sustainability and fertility, but also as a symbol of the circulatory nature of time and the ancestral political ties the moieties had to the land. These ancestral ties ran generations deep and can be interpreted in the archaeological record of ceramic styles in Moche times, as described below.

Figure 4. Parcialidad divisions of the late pre-Hispanic and early colonial period delineated by irrigation canals (after Clément Reference Clément2015; Netherly Reference Netherly1984; Russell & Jackson Reference Russell, Jackson and Pillsbury2001).

Moche worldview

I now turn to evidence from Moche archaeology to show that the Andean concepts outlined above were relevant in earlier times. Many scholars have argued that dualism was a feature of Moche society and visible in aspects of Moche art and praxis (Bourget Reference Bourget2006; Holmquist Reference Holmquist, Wuffarden, Majluf, Bondil, Holmquist, Pimentel and Alva2013; Swenson Reference Swenson, Jennings and Swenson2018). Yet dualism is not always explicit in the archaeological record. It is easy to suggest that the existence of two huacas at a Moche site is a manifestation of dualism (Quilter Reference Quilter2002), yet time is a critical component since not all huacas at any given Moche site were constructed or in use at the same time. Refined work on chronology at the Huacas de Moche site now shows that prior to 650 ce, the Huaca de la Luna was the main structure. Around 600–650 ce, focus shifted to the Huaca del Sol (Uceda Reference Uceda, Quilter and Castillo2010). Although not contemporaneous, these huacas still could have been some kind of manifestation of dualism, as the importance of time—as seen in the Inca Cusco example above (Gose Reference Gose1996)—has not been addressed for Moche. This is explored more below.

Drawing on the idea that moiety organization was similar in Inca and Moche times, Topic and Topic (Reference Topic, Topic, Nielsen and Walker2009) and Benson (Reference Benson2012) argue that the Moche participated in a form of ritual battle similar to tinku. However, the crucial aspect of tinku in terms of a physical part of the landscape that brings two parts together has not been addressed in Moche studies. Below I suggest that the concept of tinku extends beyond ritual battles for the Moche and applies to canals in Moche times. A canal acts as a thread that weaves two parts of the landscape together in physical, social, temporal and symbolic terms. The water flowing through the canals and snaking through mountains and huacas on the landscape was also vital to the well-being of society.

Other highland concepts are also notable in the Moche archaeological record. As in the highlands where mountains are often associated with males, some Moche ceramic vessels depict an erect penis as a mountain peak (Scher Reference Scher2012). Huacas are symbolically associated with mountains—places of power that are connected with sacrifice, fertility and the source of flowing water (Swenson & Warner Reference Swenson and Warner2016). At the Huaca de la Luna, Guadalupito, Mocollope and numerous other Moche sites, extant hills and rocky outcrops were incorporated into the huaca construction, intimately connecting them to the power of the mountains and also perhaps representing a vertical, as well as a natural/cultural, manifestation of tinku (Dean Reference Dean2007). Huacas are also often placed at the base of coastal mountains, where they replicate alignments and/or features of the mountains themselves (Koons Reference Koons2012; Swenson & Warner Reference Swenson and Warner2016). Liquids feature prominently in our understanding of what happened at Moche huacas. The spilling of blood during sacrifices fed the earth and awakened the huacas. Corn beer flowed freely at ceremonies and through consumption was transformed into urine and eventually returned to the earth (Cummins & Mannheim Reference Cummins and Mannheim2011).

The gestural sprinkling of fluids, much like the Quechua word t'inkay, is apparent at Pañamarca, a southern Moche huaca centre. Here, murals were spattered with liquid—possibly with hallucinogenic properties—as part of an architectural reopening event (Trever Reference Trever and Costin2016). At Licapa II, as an act of closing, liquid was poured over a Moche tomb inside the architectural layers of Huaca A (Koons Reference Koons2012). A similar tomb-closing event involving spilled liquid is seen at San Jose de Moro (Mauricio & Castro Reference Mauricio, Castro and Castillo Butters2008).

The stirrup-spout bottle in particular is intimately tied to the movement and circulation of fluids. These vessels are ubiquitous at Moche huaca centres and in tombs. They were constructed so that liquid flows into and out of the vessel's body through the circular spout, mimicking the flow of vital bodily fluids (Weismantel Reference Weismantel2021). Along with scenes of sacrifice and bloodshed, sexual acts are the subject of a suite of stirrup-spout and other vessels. Weismantel (Reference Weismantel2004) claims that vessels portraying sexual acts between women and skeletons, as well as images of skeletons masturbating, highlight the importance of ancestors in the living Moche world. She suggests that the exchange of fluids between the living and the dead demonstrates a conception of time and kinship that is not linear, but circulatory. Ancestors remain active players in the lives of the living, as their fluids circulate through each generation. Claiming descent from an ancestral lineage was the key to economic and political power, as control of irrigation systems and agricultural fields was linked to ancestral ties (Weismantel & Meskell Reference Weismantel and Meskell2014). To keep things circulating and in order, the past had to exist in the present to legitimize political power.

The fusion of and circulation of space and time can also be interpreted in the built environment. Many Moche huacas are encapsulated within a new remodel or reconstruction phase, which Spence Morrow (Reference Spence Morrow, Swenson and Roddick2018) suggests signals temporality as synecdochal. Older, terminated buildings, which were once whole huacas themselves, are enveloped by new ‘whole’ huacas. Through the renewal process, the older buildings, or phases, become energized and active ‘parts’ of the new whole huaca. As such, built structures were fluid and malleable in their everlasting presence on the landscape. They marked time and legitimized political order by linking the present authority to a deep and layered history (Spence Morrow Reference Spence Morrow, Swenson and Roddick2018; Spence Morrow & Swenson Reference Spence Morrow, Swenson, Tantaleán and Lozada2019). Thus, through construction projects large and small, the Moche manipulated the flow of time. Beyond the Moche, the stability and permanence of structures from all time periods no doubt played an important role in people's lives throughout time. The built environment of the entire coast can be viewed as a palimpsest where the past and present commingled.

Below, I contend that canals acted as tinku—they brought two parts of the society together to create the whole and entwine the past with the present. Furthermore, the flowing, or circulating, of liquids though the canal systems was vital in delineating this socio-political order and tying it to the realm and power of the ancestors.

Ceramic styles and irrigation networks in Moche times

The distribution of different Moche ceramic styles, specifically Moche IV and V, helps elucidate Moche socio-political organization in the Chicama Valley and how it relates to canals. Research over the last decade shows that Larco's pioneering five-phase ceramic sequence (Moche I–V) cannot be strictly understood as phases, but rather is better characterized as different regional styles that have a loose association with time (Donnan Reference Donnan2011; Koons & Alex Reference Koons and Alex2014). The southern part of the Chicama Valley post-600–650 ce is dominated by Moche IV wares, a style that probably originated at the Huacas de Moche (Franco Jordán et al. Reference Franco Jordán, Gálvez Mora, Vásquez Sánchez, Uceda and Mujica2003; Russell & Jackson Reference Russell, Jackson and Pillsbury2001). Moche V ceramics characterized the northern part of the valley

Of the more than 40,000 Moche ceramics in the database at the Larco Museum in Lima, 207 are Moche V. Most of these have an unknown provenience, but many of the remainder come from the northern Chicama Valley, specifically from the area around Paiján and Tchuín, the same region as the colonial-era Licapa polity (Fig. 2; Table 1). Significantly, many are from along the canal segment that ran through Licapa II, and excavations here revealed other examples (Koons Reference Koons2015). This canal was defunct by the colonial era and to my knowledge is not discussed in any documents. It is also unclear as to how this canal was integrated into the overall network and received water from the Chicama River, but an evaluation of satellite imagery, existing canals and valley hydrology suggests a few possible routes, detailed in Figure 5. The flowing water through the canal intimately connected the places and people who resided alongside it. Thus, moiety organization might explain the material differences seen between the northern and southern Chicama Valley.

Figure 5. Possible original routes of the canal that runs through Licapa II. In order of likelihood: 1. The Colup canal had a branch that extended further to the west from the main artery seen today. 2. Water from the Nuxa canal could have travelled past Mocan to the desert valley margin, where it descended to Cerro Azul and eventually Licapa II and Paiján. This is plausible based on the topography and current canal configurations but would have made Licapa II and the Paiján region vulnerable to water shortages. 3. Both the Colup and Nuxa canals were used to water Licapa II and Paiján, making this a prominent region because of its varied access to sources of water. 4. There was another canal branch now under modern agricultural features that brought water more directly from the Nuxa canal or via another route.

Table 1. Sites with Moche V ceramics in the Chicama Valley. (Information compiled from Museo Larco's online catalogue.)

I suggest that Moche V was a style associated with the northern Chicama Valley and in the region of the colonial-era Licapa polity (Fig. 2). Moche IV dominates the southern part of the valley—the location of the Chicama polity. This region probably had closer affiliations to the Moche Valley to the south, as is evidenced by similarities in material programmes at Huacas de Moche and El Brujo. It is also significant that the boundary between the Quingnam and Mochica languages map to this same location (Netherly Reference Netherly and Christie2009; Urban Reference Urban2019). Although much more study is necessary, the linguistic division may mirror the material differences found in the northern versus southern parts of the Chicama Valley.

It is noteworthy that, while Moche IV wares are found in the northern part of the valley, very few Moche V wares are found in the south (Régulo Franco pers. comm., 11 May 2020). These patterns can be explained by how the nested structure of Andean moieties functioned. If the Chicama polity ranked higher than that of Licapa, then we would expect to find dominant polity materials in the subordinate territory, but not necessarily the reverse. Furthermore, Moche IV and V wares obviously occur outside the Chicama Valley. Using the moiety model, we can conclude that political expansion of a community occurred by increasing the scale of the moiety divisions that were recognizable as complementary units bound by reciprocal relationships (Topic & Topic Reference Topic, Topic, Nielsen and Walker2009). These moiety dynamics could account for Moche V ceramic styles spreading outside the northern Chicama and into other valleys north and south, as well as for the variety of materials found at all Moche sites.

Similar to the colonial era, in Moche times the canals acted as tinku, uniting and dividing moieties at different scales. Social organization can be traced though the different ceramic styles that dominate and characterize sites affiliated with canal branches in the north and south parts of the valley.

Licapa II in the Chicama Valley

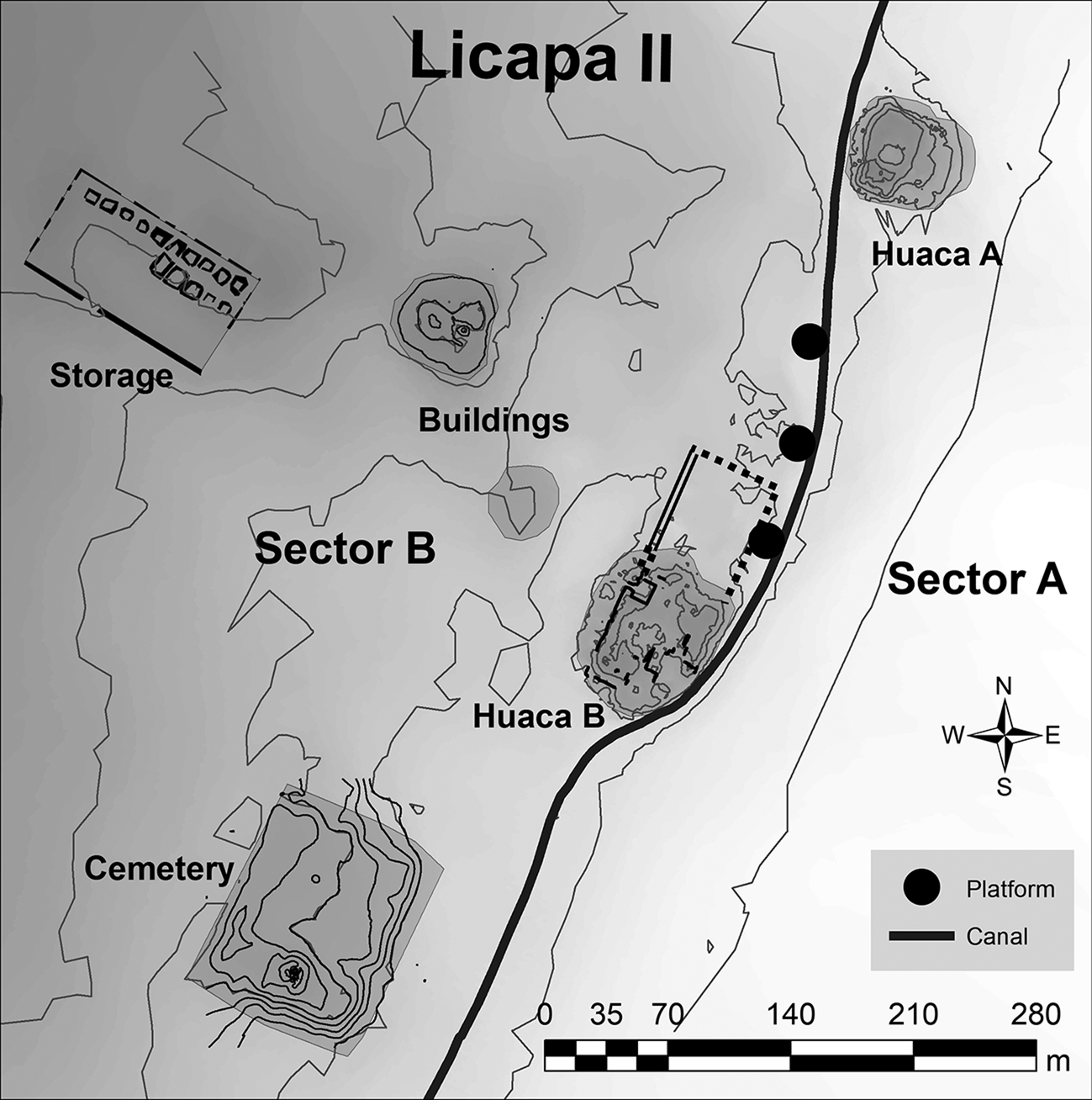

Licapa II can be viewed as a synecdoche of the valley-level organization. It is a mid-sized ceremonial centre on the northern desert margin 25 km from the Chicama River. Licapa II is situated at the base of Cerro Azul, a large coastal mountain, and is dominated by two huacas, Huaca A and Huaca B. Significantly, an irrigation canal bisects the site into two sectors (Sectors A and B) that have distinct archaeological signatures (Fig. 6; Table 2). Here I suggest that the canal acted as tinku in that it brought together the two sectors. The circulation of water through the canal and the importance of liquids in the activities of the site overall both point to the significance of concepts understood from Quechua and Aymara—tinku, liquids and time— in Moche life.

Figure 6. Licapa II showing the structures, the canal and the platforms along the canal. The excavated part of the residential area included the northernmost of these platforms.

Table 2. Comparison of Sectors A and B at Licapa II.

Sector A

East of the canal is Huaca A, a 55 × 57 m and 9 m tall structure that is highly visible from below. Radiocarbon dates show that Huaca A construction levels are pre–650 ce (Koons Reference Koons2015), but Huaca A could have continued to be used for ceremonies after its final phase of construction. The ceramics associated with Huaca A lack ornate decoration; I refer to these as the Licapa A style (Koons Reference Koons2015). They are stylistically different from the Moche IV, Moche V and Late Moche ceramics found in Sector B; these ceramics contain elaborate narrative scenes (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Examples of Moche vessels from the Chicama Valley found during my excavation and in the Museo Larco (ML). (A) Licapa A-style goblet from Licapa II (author's photograph); (B) Moche IV vessel from Facalá (ML003700); (C) Figurative Moche V vessel from Mocán (ML003758) (D) Geometric Moche V vessel from Tchuín/Paiján (ML011015); (E) Late Moche vessel from Paiján (ML002298). (Images B–E are from the Museo Larco, Lima, Peru.)

A significant part of the Licapa A ceramic assemblage consisted of goblets, much like the ones used in the Sacrifice Ceremony, also known as the Presentation Theme. The Sacrifice Ceremony is best known from fine-line drawings on ceramic vessels; these drawings depict warriors and anthropomorphized animals slitting the throats of prisoners to fill goblets with their blood. These goblets are then presented to highly regaled elites (Donnan Reference Donnan, Quilter and Castillo2010; Donnan & McClelland Reference Donnan and McClelland1999).Footnote 5 Donnan (Reference Donnan, Quilter and Castillo2010) claims that the Sacrifice Ceremony was the glue that held the Moche together as an archaeologically recognizable culture. Archaeological evidence from Huaca de la Luna indicates that this ceremony or something similar was probably enacted there (Uceda Reference Uceda, Quilter and Castillo2010). One of the scenes depicts an elite holding goblets and seated on top of a structure that architecturally is very similar to Huaca A.Footnote 6 Based on the presence of goblets and the architectural form of Huaca A, I have suggested that this structure is where important Moche ceremonies, like the Sacrifice Ceremony, were performed at Licapa II (Koons Reference Koons2015).

Overall, Huaca A served a ritual purpose that was intimately tied to the imbibing and pouring of liquids. Inside the layers of Huaca A was a burial of a female and liquid was poured over her head in a closing act. The goblets used to present and drink blood or other liquids in ceremonies that took place on this artificial mountain, as well as the intimate relationship of the huaca and the canal, both point to the significance of liquids and their circulation in this sector.

Sector B

Huaca B, two small structures, a platform cemetery, storage area and a residential area sit west of the canal in Sector B. Huaca B is larger than Huaca A, measuring 80 m long, 66 m wide and 6–7 m high. It consists of enclosed rooms and chambers at different levels; these rooms and chambers are not visible from outside the structure, suggesting that Huaca B's function was for more private activities than in Huaca A. A large, walled platform is situated on the north side of the huaca. Here I uncovered evidence for feasting in the form of four large cooking or corn-beer brewing vessels, known as paicas, placed in a row and supported by adobe frames. Adjacent to the paicas was a large ash-filled pit from cooking and brewing activities. Additionally, my team found over 30 musical instruments on the platform near the ramp entrance to Huaca B. All of this indicates that music, feasting and consumption were important elements of rituals on this part of the site.

Ceramics from this sector are northern Late Moche fine-lines, Moche IV and Moche V (Fig. 7). Moche IV and V ceramics were found together throughout all stratigraphic contexts, reinforcing that these represent contemporaneous styles and not temporal phases (Koons Reference Koons2015). Radiocarbon dates indicate that this sector of the site was primarily used from roughly 600–800 ce.

In Sector B, we excavated a portion of the residential area that abuts the west side of the canal and located six layers of occupational surfaces that included hearths, rooms and a guinea-pig pen (Koons Reference Koons2015). The plethora of fine Moche IV and V ceramics suggest that people using this space were of elevated status and/or lived here only during ceremonies that involved these fine ceramics.

The final occupation level in this residential zone consisted of a raised platform made of adobe. A continuous plastered floor extends from the canal up to the easternmost wall of the platform, seamlessly connecting the canal and platform structure. Farther to the south but in the same residential zone of the site, the ground topography and the architecture visible inside looters’ holes indicate that there are at least two additional adobe platforms along the west side of the canal (Fig. 6). I suggest that the intimate association of these platforms and the canal indicates the continued, and possibly increasing, importance of water and/or ceremonies surrounding water and this canal in this marginal desert zone.

The canal as tinku

The entire site is intimately woven together and defined by the canal and what lies on either side. Sector A consists of the highly visible Huaca A, where ceremonies were performed with goblets possibly once filled with blood. Sector B consists of the privately enclosed Huaca B, a residential area and at least three adobe platforms in direct association with the canal. I contend that the canal acted as tinku at the site level; it divided the site into two sectors, yet united the two halves to make a whole. Vital to the canal's role was the water that ran through it; the water libated and sustained the land and the people who lived there.

The different ceramics on either side of the canal may be related to nested moiety divisions. Moche IV and V wares are almost all found on the west side of the canal in Sector B. Sector A had Licapa A style and very few examples of Moche IV wares, and no Moche V. The activities associated with each site sector were also distinct. These differences may indicate that this canal united and divided not only the site itself, but also nested moiety divisions within a larger polity, much as canals did in later times. Perhaps like tinku, the canal at Licapa II was where two polities came together to perform ceremonies that served to balance the site, the different moiety divisions and the Moche society as a whole. However, time is also a factor in the material differences of Sector A and B, yet our linear understanding of time might obscure the living role of ancestors and ancestral lands and how this related to moiety organization and Moche politics.

In these terms, Licapa II can be viewed as a synecdoche or microcosm of the nested structure of organization in the Moche world. Much as micro-ayllus are nested within macro-ayllus, where at each level the same structure was replicated, the canal's role at Licapa II can be seen as a microcosm of how canals in their entirety delineated and defined socio-political organization at the valley level. The key to maintaining balance and cohesion within the society was through rituals—many of which involved liquids in its various forms. These rituals included sacrificial bloodshed in terms of ritual warfare and offerings to huacas, ancestors and mountain deities, ceremonies involving heavy consumption of corn beer, and undoubtedly ceremonies surrounding the canals and the life-giving waters that flowed with them and outlined space socio-politically and temporally.

Tinku, liquids and time at Licapa II and beyond

As the canal acted as tinku, the circulation of liquids through the canal was a vital component in both physical and symbolic forms. During the summer months, the water discharge from the Chicama River can be low. This probably disrupted the operation of the canal, situated 25 km away from the river. The small platforms along the canal could have held ritual significance, possibly related to the need for water in this desert zone.

Water temples along canals are noted in Inca Cusco and elsewhere (Wright Reference Wright, Dunn and Van Weele2017), and it is possible that the structures at Licapa II were used for some ceremonies associated with the circulation of water. However, many Moche sites are at the distal ends of irrigation canals (Quilter Reference Quilter2002; Quilter & Koons Reference Quilter and Koons2012). Quilter (Reference Quilter2002) suggests that if the concept of the circulation of water down from the mountains and back up (Bastien Reference Bastien1978) was a key feature of Moche religion, as in other Andean religions, then positioning important sites at the distal ends was quite appropriate. Perhaps some Moche huacas were involved in systems of water distribution similar to temple management of irrigation in Bali (Lansing Reference Lansing1987), where the timing of when field sections were irrigated was linked to when rituals were held at associated temples (Quilter & Koons Reference Quilter and Koons2012). It is also noteworthy that in the colonial era some lands were watered from the distal end of the canal to the intake so that the communities farthest away from the river were the first to receive water (Netherly Reference Netherly1984). Therefore, Licapa II's position in what today seems like a marginal zone may have actually been desirable in the past. Its proximity to and alignment with the mountain peaks of the inimitable Cerro Azul could have also been a factor.

The importance of liquids at the site is highlighted by the canal and the activities performed on either side. The canal can be viewed as a metaphorical river, weaving between the two mountains (huacas) at the site. The water in the canal ensured the earth's fertility, much like blood from the sacrifices performed at Huaca A. In some circumstances, this blood was from prisoners captured and/or ritually sacrificed in tinku-like battles. Likewise, feasting and consumption involving corn beer, and no doubt urine and other bodily excretions, were important activities in Sector B. When viewed holistically, the circulation of fluids at Licapa II is vital to understanding its role in the Moche world.

The circulatory nature of time was also embossed on the landscape at Licapa II. Radiocarbon dates, as well as distinct ceramic assemblages, indicate that Sector A and B were primarily in use, or at least constructed, at different times. Elsewhere, I have suggested that the differences we see in the two site sectors highlight changes throughout Moche society around 650 ce (Koons Reference Koons2015). However, if we take a step back from this linear understanding of time and incorporate the chronological data with an Andean understanding of time as being circulatory—the past alive in the present (Bray Reference Bray, Swenson and Roddick2018; Swenson & Roddick Reference Swenson and Roddick2018; Weismantel Reference Weismantel2004)—then a more complex picture begins to emerge.

Sector A, although chronologically older than Sector B, may have had ancestral significance and continued to play an active part in people's lives, even if its primary use changed or shifted over time. With this understanding, it is significant that the canal at Licapa II divides the site into the two sectors. It also acts as a centre line that unites and defines what is on either side in spatial and temporal terms. Likewise, at the Huacas de Moche, the Huaca de la Luna surely remained integral in the lives of the site's inhabitants even after it closed and the focus shifted to the Huaca del Sol and the New Temple (Uceda Reference Uceda, Quilter and Castillo2010). Canals are present between these huacas and may have played a role in uniting and dividing the site spatially and temporally, but this has yet to be explored. Overall, the temporal component to tinku is not as explicit in the Quechua sources or archaeology (cf. Gose Reference Gose1996), but the north coast's dry environmental conditions and extreme preservation of the past on the landscape suggest that we can add new understanding to this concept from the archaeology of the coast, despite language differences.

Conclusion

From this analysis, I suggest that a fractaline organization system was in place by Moche times. Canals were the dividing line between moieties in late pre-Hispanic times. I argue these divisions have their roots in the Moche era, if not earlier, and can be traced to the clustering of particular Moche ceramic styles along canal branches.

The site of Licapa II can be seen as a microcosm of the socio-political division of space in the valley. The two distinct sectors are separated, yet also united, by a canal. We can view each sector as a part of a whole or both together as a manifestation on the landscape of the Quechua concept of yanantin. The canal acts as tinku, the centre that brings the two parts together to achieve balance. The huacas at Licapa II, like other Moche huacas, mimicked sacred mountains, and liquids—blood, corn beer, semen, urine, etc.—served to enliven them during ceremonies. The fact that the canal, a metaphorical river, weaves between two huacas—separating them yet bringing them together—demonstrates the power and significance of the circulation of fluids of all kinds. Furthermore, the water in the canal would also have had significance, as it libated the land it ran through. It is probable that water rituals and the political motivations surrounding these were pertinent to Moche society, much like the modern-day t'inka rituals that function to return fluids to the mountains, which supply the rain and foster fertility (Gose Reference Gose1994). In its various forms, liquid was symbolic of and essential to the cyclical rhythm of nature and the world. It was vital to ensuring the well-being within an individual body, the ancestors, the community as a whole and the cosmos (Sikkink Reference Sikkink1997).

We can use this case study to reflect on how aspects of Moche society can be viewed through the lens of more recent accounts of Andean worldview. However, rather than applying Quechua and Aymara concepts wholesale to the Moche, we must look to the archaeological record to evaluate critically the applicability of each term/concept on an individual basis. In so doing, it is apparent that certain ideas have great time-depth and spatial reach, regardless of language. The dualistic nature of political organization is a shared principle, as well as ideas involving geographical features common to all of the Andes, such as mountains and rivers. By taking a ground-up approach, the understanding of Andean conceptual frameworks becomes an additive process and not merely one of trying to make terms fit. For example, the exceptional preservation on the north coast allows us to understand better how time functioned and was inscribed on the landscape. From an analysis of the canal at Licapa II, I suggest that the concept of tinku operated on multiple levels, including in the temporal realm. Thus, by using this approach, we can identify nuances in Andean concepts we would not see if we were looking only at Spanish chronicles or Quechua and Aymara resources.

Acknowledgements

Preliminary thought on this topic appeared in my dissertation, and I thank Jeffrey Quilter, my former advisor, for comments. I thank the Larco Museum for access to their database. Lisa Trever, Steve Nash, Ari Caramanica, Mary Weismantel, Patrick Mullins, Erin Baxter and Rick Wicker provided tremendous support on various portions of this work. I also thank the anonymous reviewers for valuable feedback on previous iterations of this paper. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (Dissertation Improvement Grant 1032294) and the National Geographic Society (Committee for Research and Exploration Grant). Fieldwork was conducted under Resolución Directoral Nacional N° 292/INC Lima 17 February 2010.