Body alteration in human history represents a permanent way for individuals to distinguish themselves from others. Altered appearances, at the same time, signify belonging to sub-groups of society. Tooth filing is one common cross-cultural aspect of embodied identity that preserves on human skeletal remains, unlike modifications to the skin. The Pre-Columbian Maya of the Yucatan peninsula engaged in dental modification, along with head binding, tattooing, piercing and body painting. These corporeal alterations complemented a broad array of adornments related to dress (Carter et al. Reference Carter, Houston and Rossi2020).

Here we examine tooth filing in the context of urban life at the last Pre-Columbian Maya capital of Mayapan, Yucatan, Mexico. This city of 20,000 people represented the nucleus of an expansive regional political domain in the Postclassic Period (1150–1450 ad: Hare et al. Reference Hare, Masson and Russell2008b). Mayapan was a pluralistic, multi-ethnic urban archaeological setting. Our findings reveal that while females, exclusively, filed their teeth (in the skeletal sample), most women and men at the city chose not to do so. Sculptural art nuances the binary sex correlations of dental modification at the site. Mayapan tooth filing patterns highlight the complex interplay of decisions to emulate a general style, with fine-grained, individualized variations on a theme in terms of choice of teeth, style of modification and references to symbolic icons.

This study contributes to comparative archaeological research concerning clothing and adornment (Loren & Nassaney Reference Loren and Nassaney2010; Mattson Reference Mattson2021). Adornment is a means of communication, visually conveying messages about belonging to various social sub-groups (Loren & Nassaney Reference Loren and Nassaney2010, 8). Turner (Reference Turner2012, 486) refers to such presentation as a ‘social skin’, eloquently stating that the ‘surface of the body seems everywhere to be treated, not only as the boundary of the individuals as a biological and psychological entity but as the frontier of social self as well’. Archaeologists have applied this concept to the study of the materiality of adornment (Loren & Nassaney Reference Loren and Nassaney2010, 8).

Identity exists within complex, intersectional matrices of time, space and society (White & Beaudry Reference White, Beaudry, Majewski and Gaimster2009, 210). It is important to consider more than one dimension of personhood in society (Scott Reference Scott and Scott1994). Material culture use, dress, adornment and modification shaped, reinforced and perpetually reproduced or transformed identities in the context of practice (White & Beaudry Reference White, Beaudry, Majewski and Gaimster2009, 211). Corporeal inscription, of which tooth filing is one variant, reflects voluntary or involuntary manipulation of the presentation of individuals (White & Beaudry Reference White, Beaudry, Majewski and Gaimster2009, 212). The body presents archaeologists with the best opportunities to studying the personhood of individual human beings (Joyce Reference Joyce2005). Bodies represent canvases for display (Meskell Reference Meskell1996) and were central in performances of sexual, racial and cultural differences (Loren & Nassaney Reference Loren and Nassaney2010, 9). Bodies themselves, like things, are material entities, used by individuals to experience personhood (Hamilakis et al. Reference Hamilakis, Pluciennik and Tarlow2002). Adornment is explicitly linked to embodiment of self, and to bodily experience (Loren & Nassaney Reference Loren and Nassaney2010, 8).

Social identity and urban life

Cross-culturally, ‘closing’ is practised by sub-groups within society, particularly elites, who distinguish themselves through exclusionary consumption rituals, ornamentation, architecture and dress (Graeber & Sahlins Reference Graeber, Sahlins, Graeber and Sahlins2017; Hinton Reference Hinton1999). Participation in an international elite culture was an important part of maintaining status, wealth and power for late Mesoamerican states, and it paved the way for lucrative cultural and commercial exchange dependencies over great distances (Pohl Reference Pohl, Smith and Berdan2003; Ringle et al. Reference Ringle, Negrón and Bey1998; Smith & Berdan Reference Smith, Berdan, Smith and Berdan2003). Yet in certain contexts, stylistic trends originate from individual trendsetters (or grass roots subgroups), as Blumer (Reference Blumer1969) argues for clothing styles in Paris in the 1960s and Lesure (Reference Lesure2015) considers for ceramic figurines in Formative Period central Mexico.

The study of style in archaeology is a complex undertaking, confounded by a variety of factors affecting artefact attributes and exchange. Shared styles across different spatial and social contexts can sometimes reflect diametrically opposed historical processes (Dietler & Herbich Reference Dietler, Herbich and Stark1998; Hodder Reference Hodder1982; Janusek Reference Janusek2004; Masson & Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Vail and Hernandez2010; Plog Reference Plog1983, 135). Styles can reflect conformity to established conventions, or alternatively, diversity and pluralism, witnessed at the household, site, or regional scale. In urban settings, material correlates of different social affiliations, such as hometown or polity identities, may change through time (Janusek Reference Janusek2004). States strive to inculcate and materialize a sense of unity among subjects, especially residents at urban capitals (Janusek Reference Janusek2004; Marken et al. Reference Marken, Guenter, Freidel, Beyette and LeCount2017; Oudijk Reference Oudijk and Hansen2002; Paine & Storey Reference Paine, Storey and Storey2006). Stylistic choices may counteract state efforts to enforce a normative identity, especially when household-scale activities and possessions constitute subtle acts of resistance (hidden transcripts) for subaltern groups (Chuchiak Reference Chuchiak2004a, Reference Chuchiak, Behrens, Grube, Prager, Sachse, Teufel and Wagnerb; Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Bustamante and Levine2001; Liebmann Reference Liebmann and Card2013; Scott Reference Scott1990).

The concept of authentic social identity is one that is flawed, subjective and dynamic, and minority groups may adopt the material culture of majorities for their own unique purposes (Nassaney Reference Nassaney2012, 8–9, 15). Individuals, families and other groups may live with a ‘double consciousness’ involving masking difference (ethnic, racial) in intolerant social settings (Mullins Reference Mullins, Leone and Potter1999, 171). Yet, as Mullins observes (1999, 170), simple dichotomies such as authentic and ‘false front’ identity presentation do not do justice to the complex decisions and practices of historical peoples. Choosing to adopt mainstream stylistic culture in terms of material possessions or dress may represent a statement of equality that challenges social hierarchies, even if agents are mindful of status rigidity and biases (Mullins Reference Mullins, Leone and Potter1999, 171). Material and bodily social expression may have been regarded with ambivalence, in which agents experience simultaneous attraction and revulsion to the material trappings of a dominant or majority culture (Liebmann Reference Liebmann and Card2013, 31). Dress may constitute mimicry, or its extreme, mockery (Mambrol Reference Mambrol2017).

Beyond style, membership in subgroups of urban places can be determined at settlements like Mayapan. Residential groups at the city differ according to relative wealth and degree and kind of occupational specialization (Masson & Peraza Lope Reference Masson and Lope2014a). Certainly the city's elites distanced themselves from ordinary residents by their elaborate dwellings, restriction of literacy and knowledge, and oversight of production of the most precious, symbolically charged goods (Delgado Kú et al. Reference Delgado Kú, Lope, Masson, Escamilla Ojeda, Alvarado, Russell, Kennett, Masson, Hare, Peraza Lope and Russell2021). In this respect, their behaviour generally resembles elites in complex societies cross-culturally, including earlier in Maya history (e.g. Inomata Reference Inomata2001a; Smith Reference Smith2004, 89). The spatial arrangement and features of house groups, neighbourhoods, or communities may also distinguish social subgroups from one another (e.g. Aldenderfer & Stanish Reference Aldenderfer, Stanish and Aldenderfer1993; Ardren Reference Ardren2002; Ardren & Hutson Reference Ardren and Hutson2006; Masson et al. Reference Masson, Hare, Lope, Masson and Peraza Lope2014; Rice Reference Rice, Rice and Rice2009; Rice & Cecil Reference Rice, Cecil, Rice and Rice2009; Santley et al. Reference Santley, Yarborough, Hall, Auger, Glass and MacEachern1987). However, urban planning and architectural standardization may also be undertaken by state authorities with the goal of strengthening social ties to the urban built environment (Hare et al. Reference Hare, Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014a; Pugh & Rice Reference Pugh and Rice2017; Smith Reference Smith2007, 8).

For urban centres with diverse and dynamic population compositions marked by ongoing replenishment by new arrivals, it is important to consider the origins of migrants and other arriving persons (Paine & Storey Reference Paine, Storey and Storey2006). Commonly, urban places recruit residents from nearby towns and regions; Mayapan was initially populated in this way (Tozzer Reference Tozzer and de Landa1941, 23–6). Historically, migrants often join family already established in a city, or they move to a place with which they are familiar from visits to markets or other events (Russell Reference Russell1972, 231). Cosmopolitan cities invite foreign allies, including military personnel or brides, into their ranks, as was the case for Classic Period Maya polities (Martin & Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008). Mayapan's last regime is said to have invited Gulf Coast ‘mercenaries’ to settle into the city (Roys Reference Roys, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962, 80). Other migrants are attracted by work, trading, or religious opportunities (including the priesthood and pilgrimages) or apprenticeships, and artists and aspiring literati are also drawn by urban allure (Masson & Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Peraza Lope2014b, 558). Cities with reputations as the premier, cosmopolitan centre of governance, learning and the arts, like Mayapan (Roys Reference Roys, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962, 50–51, 53, 56), attract talent from near and more distant locations. Enslaved persons represent an additional category of involuntary urban residents, which, in the Mayapan case, were captured in warfare (Roys Reference Roys, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962, 47; Scholes & Roys Reference Scholes and Roys1938). Evidence for Mayapan's multi-ethnic residential composition derives from historical sources and material archaeological remains (Masson & Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Vail and Hernandez2010; Peraza Lope & Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014a).

These processes provide multiple settings for Others to be present in the milieu of urban places, which in part, may be defined by their characteristic of social diversity and improved tolerance of interpersonal differences compared to small rural settlements (Janusek & Blom Reference Janusek, Blom and Storey2006, 233; Pounds Reference Pounds1973, 344–55). However, as much as governments may desire full conformity and polity-scale loyalty, they may not achieve it (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Carter, Rossi, Carter, Houston and Rossi2020, 1). As Lesure (Reference Lesure2011, 116) observes, stylistic expressions of human personages can reflect local identity divergence, or the opposite, convergence. Both patterns may be manifested in urban, pluralistic settings.

Social identity and body modification at different scales

Archaeological inquiry into the topic of adornment and corporeal presentation has been a fast-growing focus of research in comparative studies of social identity. Body modification represents one facet of intentional adornment. One variable that links family or individual agency is that of desired effect, specifically, the anticipated and perceived social signalling resulting from choices regarding presentation of self. To what extent do adornment and body modification indicate conformity and acceptance into identity dimensions broadly signalling belonging to social groups, and to what extent do they signal difference and social distance from others? One key aspect of body modification that we focus on in this paper is the social scale of practices, including regional, settlement, household (family), or individual persons. For example, the tabular erect form of cranial modification in the time period and region of our study conforms broadly to regional norms, given the standardization, frequency and widespread geographic distribution (Rosenswig et al. Reference Rosenswig, Briggs and Masson2020; Tiesler Reference Tiesler2014). In contrast, dental modification varies to a greater extent for Postclassic sites in the Maya lowlands, suggesting the importance of settlement (hometown) differences in expressions of self. Further, the variable frequency and standardization of tooth filing indicates differences at the family or individual level.

The concept of the imagined community bears directly on these considerations (Yaeger & Canuto Reference Yaeger, Canuto, Canuto and Yaeger2000). Individuals potentially belong to multiple social groups, or communities, not all of which are spatially concentrated. Such groups include families, hometowns, supra-familial heterarchical organizations (age sets, gender, class, occupation, recreational pursuits, neighbourhoods and others), polity and other such cross-cutting bonds. Individuals may belong to multiple identity groups and change some aspects of their presentation situationally (Cohen Reference Cohen1994; Yaeger & Canuto Reference Yaeger, Canuto, Canuto and Yaeger2000, 2, 6), although permanent markings such as shaped heads and filed teeth are not plastic forms of identity signalling. Social diversity may not always correlate with hereditary, hierarchically ranked social class. Mortuary patterns, for example, often express horizontal social distinctions (Tainter Reference Tainter and Binford1977), and Geller's (Reference Geller, Gowland and Knüsel2006, 287) comparative study of Maya tooth filing suggests this practice did not correlate with social hierarchy.

Individuals may differ in their perceptions of communities of belonging; communities are fluid constructs, perpetually reproduced and interpreted by the actions (practice) of their members (Yaeger & Canuto Reference Yaeger, Canuto, Canuto and Yaeger2000, 3, 5). Interactive communities of practice may be temporally fleeting, or long lived (Yaeger & Canuto Reference Yaeger, Canuto, Canuto and Yaeger2000, 8). The study of ancient expressions of fashion represents a promising new avenue of research related to social identity expression, display and the desire to signal affiliation to subgroups of society (Lesure Reference Lesure2015).

Pre-Columbian Maya concepts of the body and corporeal presentation have received considerable attention in the interdisciplinary studies of art and writing (Halperin Reference Halperin2014; Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006; Looper Reference Looper2009; Miller & Brittenham Reference Miller and Brittenham2013; Taube & Taube Reference Taube, Taube, Halperin, Faust, Taube and Giguet2009). Physical alterations represent an important aspect of self-presentation (Duncan & Hofling Reference Duncan and Hofling2011; Geller Reference Geller, Gowland and Knüsel2006; Scherer Reference Scherer2015; Tiesler Reference Tiesler2001; Reference Tiesler2014). Head binding began in infancy because of choices made by caregivers. In contrast, dental modification, performed in early adulthood, may have involved a degree of individual choice, or perhaps a rite of passage that youths were compelled to or desired to endure (Rosenswig et al. Reference Rosenswig, Briggs and Masson2020; Scherer Reference Scherer2015; Tiesler Reference Tiesler2001). Cross-culturally, such rites of passage incorporate painful ordeals that bond initiates to one another through the shared experience. Pain was an intentional component of some of these experiences (Geller Reference Geller, Gowland and Knüsel2006, 285–6). Comfort has often been secondary to sacrifices made by women from various historical societies to achieve body alterations that signalled social status (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Carter, Rossi, Carter, Houston and Rossi2020, 6).

Just over one century after Mayapan fell, clergyman Diego de Landa (Reference de Landa and Tozzer1941, 125) reported on the custom of women filing their teeth in Yucatan. The Mayapan skeletal sample corroborates de Landa's assertion that females tended to file their teeth, with no males at the site exhibiting this modification. However, the practice was surprisingly rare. Other female adornments and modifications mentioned by de Landa included nose piercing (nose plugs), ear plugs, body tattooing from the waist up, anointing themselves in red ointment, as well as a perfumed substance referred to as liquid amber or istahte which they applied in patterned designs (de Landa Reference de Landa and Tozzer1941, 126). Yet very few nose or ear plugs have been recovered archaeologically at Mayapan. Apparently, older women filed the teeth of younger females who desired it, utilizing abrasion techniques with stone and water (de Landa Reference de Landa and Tozzer1941, 125–6). Cranial shaping was also performed by women (Tiesler & Lacadena Reference Tiesler, Lacadena, Tiesler and Lozada2018, 40). Colonial Yucatec language describes individuals with filed teeth as ‘xah’, a saw-toothed person (Barrera Vásquez Reference Barrera Vásquez1995, 931; Tiesler Reference Tiesler2001), or alternatively as ‘xaham’, one that is ‘saw-toothed, like the spines of the back of an iguana’ (Victoria Bricker, pers. comm. to Serafin 2017).

Referencing the gods

Body modification sometimes purposefully mimicked traits of supernatural entities. For the Aztecs, individuals exhibiting features of a specific deity, as the result of a congenital condition or intentional body modification, could be seen to embody that deity's supernatural essence (López Austin Reference López Austin1988). Houston and colleagues (2006, 57–81) similarly argue that an individual's unique identity was represented by the head and face, sometimes embodied in a mask or other work of art, suggested by their reading of the hieroglyphic term ‘baah’. The tabular oblique style of cranial modification so common in Classic Period art (and actual burials) is a referent to the Maize God, whose head is frequently represented as an ear of corn (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006; Schellhas Reference Schellhas1904, 24; Taube Reference Taube, Robertson and Fields1985). Similarly, teeth were likened to maize kernels (Scherer Reference Scherer2015).

Tooth filing patterns may also conform to specific symbolic referents. The ‘T’ shape is a common Classic Period (ad 300–1000/1100) pattern that references the Maya glyph ‘Ik’, meaning wind, breath, aroma, or soul (Houston & Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000). The Maya Sun God of the Classic Period is often depicted with teeth—or a single, projected pointed tooth—bearing the ‘Ik’ referent (Blom & La Farge Reference Blom and La Farge1926; Geller Reference Geller, Gowland and Knüsel2006, 288). Tooth modification in this manner could have imbued the bearer with real world or spiritual benefits stemming from the properties or powers of the sun deity (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006; Scherer Reference Scherer2015). Teeth with jade inlays probably carried similar meaning, given the close relationship of this material with wind and breath (Taube Reference Taube2005). The fusion of the concepts of breath and soul is also indicated by the ‘B5’ tooth filing pattern that is present at Teotihuacan as well as in the Maya area. Scherer observes that the B5 pattern, which consists of a V-shaped notch in the distal corner of the tooth, resembles a stylized butterfly motif that commonly represented souls of the honoured dead in the art of Teotihuacan (Scherer Reference Scherer2015; Reference Scherer, Tiesler and Lozada2018, fig. 4.6).

Filing frontal teeth to a point (‘Pattern C’), as was common for the Postclassic Maya lowlands, and, indeed, much of Postclassic Mesoamerica, is not linked to the iconographic representation of a known god from the Maya codices. Yet it surely was of ritual symbolic import, and may have alluded to wind god/Quetzalcoatl imagery. Tiesler et al. (Reference Tiesler, Cucina, Ramírez-Salomón, Burnett and Irish2017) suggest that the popularity of the ‘C’ tooth filing pattern during the Terminal Classic (800–1100) is linked to Chichen Itza's rise to power and its influence on style and identity. Chichen Itza, like so many later political and religious centres in Mesoamerica (including Mayapan), gave special regard to the Feathered Serpent deity Kukulcan, known as Quetzalcoatl in central Mexico (Ringle Reference Ringle2004). Modifying one's teeth according to referents to this deity would have symbolized, minimally, an affinity to the mythical founder of Chichen Itza, Uxmal and Mayapan, to whom the origins of statecraft and the fine crafts were attributed. Quetzalcoatl/Kukulcan manifested as a wind deity in his aspect of Ehecatl in Postclassic Mesaomerica (Taube Reference Taube1992). Tooth filing in reference to the concepts of holy breath or wind (and this deity) is thus likely to have continued into the Postclassic Period.

Anthropomorphic ceramic artefacts

Female stone sculptures, figurines and effigy censers at Mayapan do not display filed teeth, suggesting that this was not a society-wide norm (Masson & Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Gallegos Gómora and Hendon2012; Peraza Lope & Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014b, 431–40). Female portrayals in art at Postclassic Maya sites usually have pulled-back, centrally parted hair and simple dresses or quechquemitl [triangular shawls] and skirts. They present as youthful or aged, signifying two known female goddesses (Vail & Stone Reference Vail, Stone and Ardren2002).

Effigy incense burners are ubiquitous for the Postclassic period, and especially for Mayapan. They provide an additional window into concepts of appearance and presentation at the city. Carefully crafted through moulding, modelling and painting, these ceramic sculptures portray both standardized attributes of Maya gods and more unique ancestral deities. Anthropomorphic figurines at Mayapan, in contrast, tend to represent generalized ideal types of men and women, lacking recognizable deity attributes, as is also true elsewhere in Mesoamerica (Joyce Reference Joyce1993; Lesure Reference Lesure2011, 113–14; Masson & Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Vail and Hernandez2010). This difference implies a contrast between ritual, public representations and figurines, which may be more relevant to the identities and needs of everyday life (Joyce Reference Joyce1993). Outside Mayapan, female ceramic effigies with filed teeth are known, although rare (Figs 1A & B). Examples include an effigy censer from the site of Zacbo, Yucatan (shared with the authors by Alfredo Barrera Rubio) and a figurine from Aguacatal, Campeche (Matheny Reference Matheny1970, fig. 52a).

Figure 1. Late Postclassic artistic depictions of personages with pointed teeth: (A) female Chen Mul Modeled effigy censer from Zacbo, Yucatan (courtesy Alfredo Barrera Rubio); (B) female Matillas Fine Orange ceramic figurine from Aguacatal (redrawn by Wilbert Cruz Alvarado after Matheny Reference Matheny1970, fig. 52a); (C, D) male Chen Mul Modeled effigy censers from Mayapan.

Examples of male ceramic portrayals with filed teeth from Mayapan (Figs. 1C & D) contradict Landa's account that this was exclusively a female practice. Male effigy censer faces with pointed teeth are spatially concentrated, paralleling findings at Zacpeten, Guatemala (Pugh & Shiratori Reference Pugh, Shiratori, Rice and Rice2018, 245). Seven of nine ceramic effigy examples from Mayapan derive from one public monumental structural group, Temple Q-80 and its adjacent hall Q-81, and shrine structures Q-79/79a (Peraza Lope & Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014b, 459, fig. 7.5c). These two buildings frame the northern border of the main plaza and face the site's principal Temple of Kukulcan (Temple Q-162). Temple Q-80 has a complex set of multiple vaulted rooms facing different directions and it is unlike the city's other temples in this regard. It clearly served a different function that called for private quarters in which multiple participants performed sacred acts. Peraza Lope & Masson (Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014c, 88) suggest it served as the site's ‘Turquoise House’, a facility known as Xiucalli in Postclassic central Mexico, where councillors congregated who were members of the Quetzalcoatl (Kukulcan) priesthood (Ringle Reference Ringle2004, 210). A mural within Mayapan's Temple Q-80 features turquoise symbols (Milbrath & Peraza Lope Reference Milbrath and Lope2003, 27), and the city's only four effigy censers decorated with Venus imagery are concentrated at Q-79 and Hall Q-81. Turquoise and Venus imagery are strongly associated in Postclassic Mesoamerican religious art and with Quetzalcoatl/Kukulcan (Milbrath & Peraza Reference Milbrath and Lope2003, 27). Given this range of indicators that the Q-80 and Q-79 architectural cluster pertains to the activities of the Kukulcan priesthood, the concentration of effigy censer male faces with filed teeth at this group may signify body modification with members of that order, who filed their teeth in reference to wind/sacred breath. Alternatively, the filed tooth censers embodied the image of a patron god of this order.

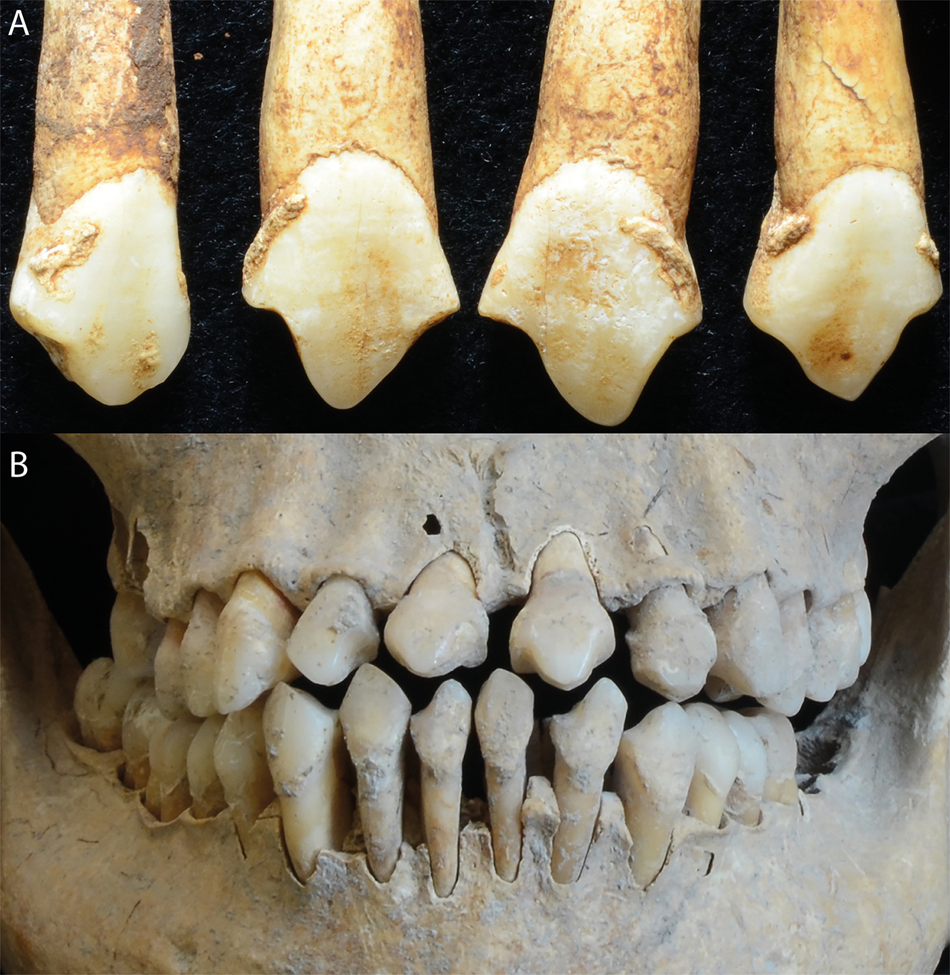

No male skeletons with filed teeth have been found at Mayapan that might suggest dental modification by members of the Kukulcan priesthood. The only examples, as we discuss below, are those of females (Fig. 2). Why females may also have modified their dentition in reference to the concept of wind represents a research question that is difficult to answer. The possibilities that women with filed teeth were in some way related to males (or other communities) engaged with the Kukulcan priesthood or that they were ritual specialists merit future investigation.

Figure 2. Late Postclassic Mayapan burials exhibiting C pattern of tooth filing: (A) Maxillary incisors of young adult female burial 09-01; (B) Middle adult female burial 21.

Mayapan

The city was founded as a new regional political capital in the latter half of the twelfth century ad by regional elites formerly associated with collapsed Terminal Classic (ad 800–1100) centres of Chichen Itza and Uxmal. Founding lords of Mayapan formed a council government of a regional confederacy comprised of smaller states across much of the northern peninsula that endured for three centuries (ad 1150–1450). Mayapan's governors rekindled the mythic charter of its Terminal Classic predecessor capitals, with an emphasis on feathered serpent origin mythology and other outward-looking political art that tied it to important commercial and political centres at least as far as the Gulf Coast, Honduras and the Guatemalan highlands (Milbrath & Peraza Lope Reference Milbrath and Lope2003; Peraza Lope & Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014c; Smith & Berdan Reference Smith, Berdan, Smith and Berdan2003). Commoner residents also engaged this inter-regional trade to a significant degree, with non-local possessions forming large percentages of the household goods deemed essential to daily life (Masson & Freidel Reference Masson and Freidel2012; Reference Masson, Freidel, Hirth and Pillsbury2013). The city was abandoned and the confederation dissolved around 1448 ad, succumbing to cycles of climatic catastrophes and the unrest that ensued from droughts and famines experienced regionally (Masson & Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014c; Peraza Lope et al. Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Hare and Kú2006; Roys Reference Roys, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962). Archaeological investigations of the site began with the Carnegie Institution of Washington in the 1950s (Pollock et al. Reference Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962) and continued more recently from the 1990s onward (Brown Reference Brown1999; Hare et al. Reference Hare, Masson and Russell2014b; Masson et al. Reference Masson, Lope, Hare, Russell, Kú, Ojeda, Cobá, Masson, Freidel and Demarest2020; Reference Masson, Hare, Peraza Lope and Russell2021; Milbrath & Peraza Lope Reference Milbrath and Lope2003; Peraza Lope Reference Peraza Lope1999; Peraza Lope & Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014c; Russell Reference Russell2008).

Archaeological enquiries into ethnicity at the household or settlement cluster scale have met with little success, largely due to the mixture of trade goods from all parts of the peninsula at households studied. The city's residents’ tastes for belongings acquired in the marketplace masked material signatures of ethnicity. Similarly, burial patterns at Mayapan vary considerably, with different types of mortuary features present at individual house groups (Hutchinson Reference Hutchinson, Masson, Hare, Peraza Lope and Russell2021; Masson et al. Reference Masson, Hare, Lope, Masson and Peraza Lope2014, 263; Serafin & Peraza Lope Reference Serafin, Lope, Tiesler and Cucina2007; Smith Reference Smith, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962). Elite dwellings and burials tend to have a more diverse array of objects (compared to commoners), sometimes with specific references to central Mexican religious icons (ceramic deity effigies or masks, for example). Such items are invariably mixed in the same contexts with more common, locally or regionally acquired ceramic or stone sculptures, portraying traditional Maya deities. Masson and Peraza Lope (Reference Masson, Lope, Vail and Hernandez2010) concluded that newcomers to the city from distant destinations assimilated relatively quickly, resulting in the majority of material goods at most contexts conforming to styles, function and symbolism characteristic of Postclassic Maya sites across the peninsula (Masson Reference Masson2001; Masson & Rosenswig Reference Masson and Rosenswig2005; Smith Reference Smith1971). Some pottery types represent exceptions in that they are widely found at the city of Mayapan but not elsewhere (Cruz Alvarado Reference Cruz Alvarado2010; Peraza Lope & Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014a). One pottery type, Pele Polychrome, may signify a social group with ties to the Peten Lakes (Peraza Lope & Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014a; Rice Reference Rice, Rice and Rice2009).

Mayapan was successful in fostering a normative housing style adopted by its residents that is largely unique to the city (Masson et al. Reference Masson, Hare, Lope, Masson and Peraza Lope2014, 194, 202, 209; Masson & Peraza Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Peraza Lope2014b, 550; Smith Reference Smith, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962, 217). Monumental architecture and public buildings at the site reveal complex combinations of conformity to standardized stylistic types, while at the same time builders of specific groups added idiosyncratic decorative motifs, sculptures, murals and wall features (Delgado Kú Reference Delgado Kú2004; Delgado Kú et al. Reference Delgado Kú, Lope, Masson, Escamilla Ojeda, Alvarado, Russell, Kennett, Masson, Hare, Peraza Lope and Russell2021; Hare et al. Reference Hare, Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014a, 189; Masson et al. Reference Masson, Hare, Lope, Masson and Peraza Lope2014, 263; Peraza Lope & Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014b, 126; Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014c, 102).

The conflicting identity politics of kin, hometown, ethnic and city-wide identities have long concerned anthropologists studying the nature of urban life (Janusek & Blom Reference Janusek, Blom and Storey2006, 233). Ironically, despite clear historical testimony to the pluralistic social milieu, and despite the centripetal pull of the hometown (cah) as the primary field of social identity at Contact (Restall Reference Restall, Inomata and Houston2001), the material signatures of Mayapan's residential groups seem to mostly mask inter-family and inter-personal differences. These findings suggest that the city's governors were reasonably successful in casting the urban centre itself as the cah. In this context, the uncommon practice of tooth modification stands out against a general backdrop of conformity and belonging at the city, especially when considered alongside widely practised cranial shaping, a form of corporeal alteration that characterized not only Mayapan residents, but a broader geographic distribution of Maya peoples across the peninsula. Mayapan, by defining itself as a confederacy of cahob [plural of cah], may have successfully inculcated at least a complementary sense of belonging to state, capital city and hometown. Janusek and Blom (Reference Janusek, Blom and Storey2006, 249) make similar arguments for socially diverse Tiwanaku, pointing out the fact that polity (political and urban centre) scale identity was accorded prestige within the city. Like Mayapan, Tiwanaku tolerated differences in the form of body modification, while at the same time encouraging buy-in through the use of ceramic feasting vessels that cross-cut diversity and fostered the unification of diversity.

Materials and methods

The composite Mayapan burial sample includes at least 288 individuals, deriving from sacrificial contexts, mass graves resulting from warfare and violence, and funerary contexts in residential and public settings, within and outside the city's monumental centre (Serafin & Peraza Lope Reference Serafin, Lope, Tiesler and Cucina2007). This study includes 742 incisors and canines representing 61 adult dentitions from Mayapan dating to the Postclassic period. Determination of age and sex of associated skeletal remains followed Buikstra and Ubelaker (Reference Buikstra and Ubelaker1994). All teeth were scored for the presence or absence of dental modification. None was observed in subadults or in premolars or molars; as a result, only incisors and canines of adults are considered in this study. The styles observed were classified for each tooth individually using the system of Romero Molina (Reference Romero Molina1986), and for relatively complete dentitions as a whole we followed Tiesler (Reference Tiesler2001). Dentitions were considered complete if at least one maxillary central incisor was present, as this has previously been shown to be the most commonly modified tooth (V. Tiesler pers. comm. to SS, 2017). Within the Mayapan collection, each adult considered complete had on average seven out of twelve anterior teeth.

Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) dating of the human skeletal samples by Douglas Kennett's lab at the Pennsylvania State University allows for chronological comparisons of the results of this study. Kennett et al. (Reference Kennett, Masson, Serafin, Culleton, Lope, VanDerwarker and Wilson2016) have provisionally analysed these results according to three arbitrary temporal intervals within the Postclassic period (ad 1200–1250, 1250–1400, 1400–1450). The site's historical chronology loosely corresponds to these intervals, with the establishment of the city toward the latter part of the 1100s, its apogee from 1200 to around 1310, a difficult period fraught with droughts, famine and unrest from 1310 to 1400, and a weakened, if resilient state from 1400 to 1450 (Masson & Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014c, table 8.1). The majority of AMS dates fall between 1150 and1400 ad, which can loosely be considered the height of Mayapan's power. Ceramic chronology is not subdivided within this 250-year period at Mayapan, given that the city's major types of pottery were made throughout its existence. However, it has long been noted that Chen Mul Modeled pottery is associated with perhaps the second half of its occupation (Masson Reference Masson2000; Peraza Lope et al. Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Hare and Kú2006; Pollock Reference Pollock, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962).

Analysis of stable carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios in bone collagen was used to assess differences in diet among individuals with different patterns of dental modification. Stable carbon isotope ratios provide information on the ecology of the consumer, distinguishable by the photosynthetic pathways (i.e. C3, C4 and CAM (Crassulacean acid metabolism)) of plants at the base of the food web (DeNiro & Epstein Reference DeNiro and Epstein1978) and between terrestrial versus marine ecosystems (Chisholm et al. Reference Chisholm, Nelson and Schwarcz1982). Stable nitrogen isotope ratios reflect the trophic level of the organism within the local food chain and distinguish between terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems (DeNiro & Epstein Reference DeNiro and Epstein1981; Schoeninger & DeNiro Reference Schoeninger and DeNiro1984). Strontium isotope ratios measured in tooth enamel reflect the local geological and bioavailable signature during the time of tooth development in the first few years of life (Bentley Reference Bentley2006). To identify non-locals, we compared local strontium baselines at Mayapan and the surrounding regions (see George et al. Reference George, Serafin, Masson, Peraza Lope, Wright, Krigbaum, Kamenov and Kennettn.d.b). Additional details of the methods can be found in George et al. (Reference George, Culleton, Serafin, Masson, Peraza Lope, Ebert and Kennettn.d.a,Reference George, Serafin, Masson, Peraza Lope, Wright, Krigbaum, Kamenov and Kennettb).

Results

Below we summarize an array of findings that indicate stylistic patterns of tooth filing, patterns by sex, temporal trends, geographic origin of individuals, and diet. We also consider the spatial distribution of tooth filing among social contexts across the city. Sixty-eight of 742 (9.2 per cent) of the teeth in our sample were deliberately modified. Most commonly, the lateral and central maxillary incisors exhibit filing (Table 1), without significant differences between the maxillary teeth (10.1 per cent; 42/417) and mandibular (8.0 per cent; 26/325) teeth (χ2 = 0.942, p = 0.332).

Table 1. Frequency of dental modification by tooth. n = number of modified teeth. N = number of teeth present and observable for modification. % = number of modified teeth divided by number of teeth present and observable for modification, calculated for each tooth type.

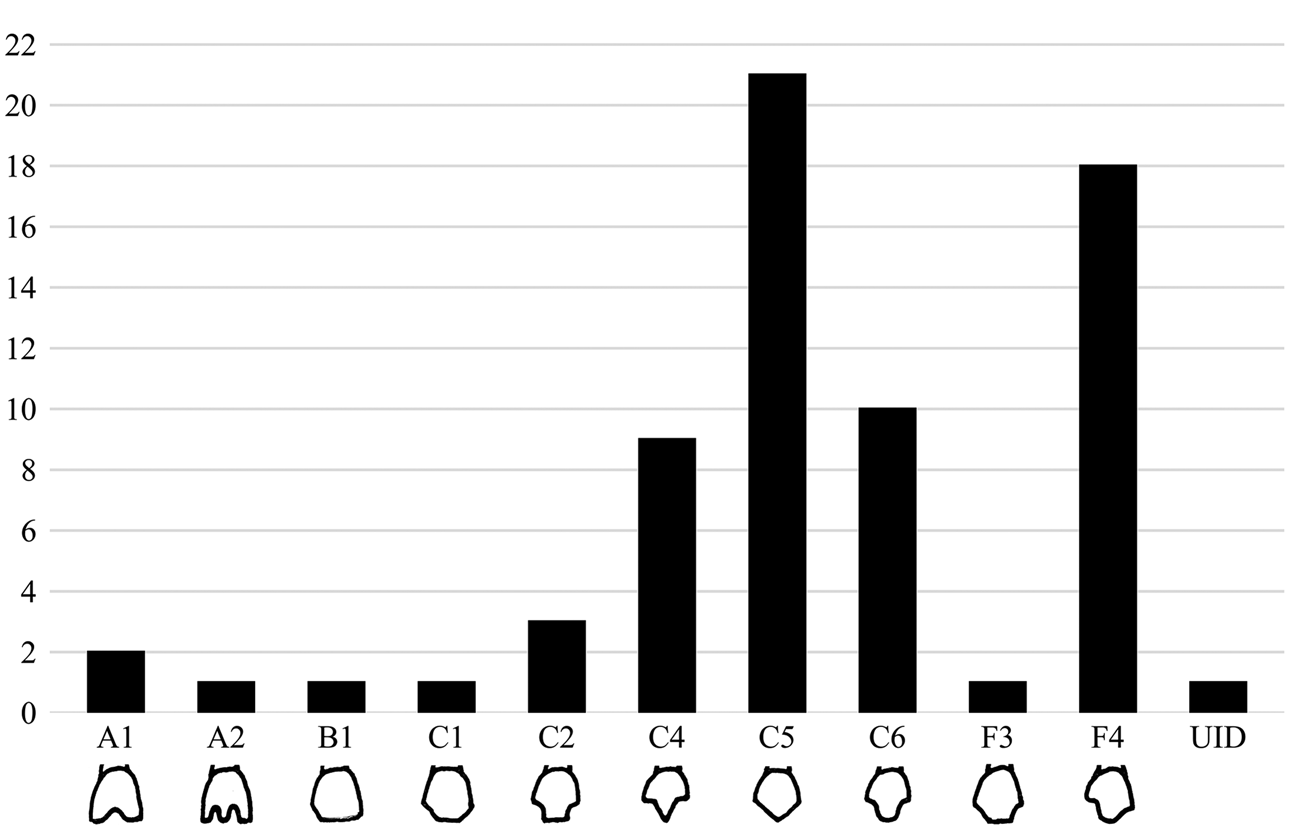

All observed cases of dental decoration represent tooth filing; inlays are absent (Fig. 3). The styles include filing one or more grooves in the middle section of the occlusal surface (Romero Molina's A1 and A2), filing just one corner of the occlusal surface (Romero Molina's B1) or filing both the mesial and distal corners of the occlusal surface (Romero Molina's C1, C2, C4, C5, C6, F3 and F4). The latter group predominates, in particular C5 (30.9 per cent), F4 (26.5 per cent), C6 (14.7 per cent) and C4 (13.2 per cent). The modification in the vast majority of cases shaped the tooth into a single large point, although variation occurs in the contour of the mesial and distal edges.

Figure 3. Number of teeth exhibiting each type of dental modification.

Ten of 61 adults with relatively complete dentitions have filed teeth (16.4 per cent: Table 2). All cases except one exhibit Tiesler's (Reference Tiesler2001) C pattern; the remaining individual exhibits pattern A. Of these 61 adults, 29 are female and 24 are male, with the others undetermined. The sexed skeletons reveal that tooth filing was exclusively a female practice in the sample (27.6 per cent, or 8/29); none of the 24 males exhibited this modification. This distribution among the sexes is statistically significant (Fisher's Exact Test, p = 0.015). An additional female with four filed teeth (exhibiting the C pattern) was excluded from the above tallies because the central incisors were absent. For two individuals with filed teeth, sex could not be determined.

Table 2. Frequency of dental modification by sex and arbitrary chronological intervals within the Postclassic occupation of Mayapan based on AMS dating. n = number of relatively complete individuals with modified teeth. N = number of individuals observable for modification. % = number of individuals with modified teeth divided by number of individuals observable for modification, calculated within each sex and period category.

Table 2 summarizes dental modification trends through time. This practice was more common earlier in the site's history, although this trend is not statistically significant (χ2 = 1.800, df = 2, p = 0.407). From 1200 to 1250 ad, 25 per cent of the sample exhibited filed teeth, more than samples of individuals dating between 1250 and 1400 ad (9.5 per cent) or to the fifteenth century (14 per cent).

Strontium isotope analyses permit the assessment of the childhood origins of 19 individuals out of the 61 with relatively complete dentitions (George et al. Reference George, Serafin, Masson, Peraza Lope, Wright, Krigbaum, Kamenov and Kennettn.d.b, table 1). Similar low frequencies of tooth filing occur among individuals from northwest Yucatan (12.5 per cent, 1/8) and individuals born outside this region (9.1 per cent, 1/11). Analysis of stable carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen isotope ratios (δ15N) in 22 females with relatively complete dentitions by George et al. (Reference George, Culleton, Serafin, Masson, Peraza Lope, Ebert and Kennettn.d.a, table 3) indicate that similar diets were consumed by females in the sample, whether their teeth were filed or not. Females with filed teeth had mean values of –9.8‰ for δ13C and 8.6‰ for δ15N (N = 5). These results are nearly identical to the mean values of females lacking filed teeth, –9.6‰ for δ13C and a mean 8.9‰ for δ15N (N = 17). The differences are not statistically significant (Mann-Whitney U Test, p = 0.583, p = 0.664, for δ13C and δ15N, respectively).

Deliberately modified teeth were found in 15 distinct spatial contexts: 10 in individuals with relatively complete dentitions and 5 representing isolated teeth (Table 3; Fig. 4). These 15 contexts include structures located within or near to the monumental centre as well as in residential zones more distant from the epicentre. These contexts mostly include residential structures, except for individuals located within three elevated shrine structures (Q-71, Q-89, Q-149) and two mass graves (Q-79/79a, H-15). Added to this spatial comparison are single filed teeth from three different architectural contexts (J-50, J-131a and Q-71) published in an earlier study (Fry Reference Fry1956). The frequency of individuals with modified teeth is slightly higher outside the main civic/ceremonial centre (19.4 per cent, 7/36 versus 12.0 per cent, 3/25) but the difference is not statistically significant (Fisher's Exact Test, p = 0.505).

Figure 4. Map of Mayapan showing locations of burials with filed teeth.

Table 3. Dental modification details by individual and context. YA, young adult; MA, middle adult; OA, old adult; A, indeterminate adult; EI, MI, LI, Early, Middle and Late temporal (Postclassic) intervals; HS, higher status; LS, lower status; V, victim of sacrifice or war.

There was little difference according to the social status of individuals with filed teeth (Table 3). Among the individuals of all sexes with relatively complete dentitions, 35 are commoners, 19 are elites and 7 are victims of sacrifice or war. 17.1 per cent of individuals from commoner dwellings had filed teeth (6/35) compared to 15.8 per cent for elites (3/19). These occurrences are not significantly different (Fisher's Exact Test, p = 1.000). For the subset of remains that could be identified as female, 18 are commoners, 8 are elites and 3 are victims of sacrifice or war. A greater proportion of lower-status females (27.8 per cent, 5/18) had filed teeth compared to higher-status females (12.5 per cent, 1/8), although this difference is not statistically significant (Fisher's Exact Test, p = 0.628). Filed teeth, according to these findings, do not correlate with any particular category of status at Mayapan. One female with filed teeth was a casualty of war at Mayapan. She was recovered face down in a mass grave next to Hall Q-79 and Temple Q-80 and had an arrowhead embedded in the right scapula (Serafin et al. Reference Serafin, Lope and González2014). Strontium analysis indicates that she probably grew up in or near Mayapan (George et al. Reference George, Serafin, Masson, Peraza Lope, Wright, Krigbaum, Kamenov and Kennettn.d.b, table 1). She may have been a victim of internal conflict at the city, referred to in mytho-historical documents as a ‘purging of the nobility’ in the late 1300s (Masson & Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014c, table 8.1; Roys Reference Roys, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962, 45).

Discussion

Tooth filing at Mayapan was practised, in low frequencies, mostly or exclusively by women, through all temporal intervals of the city's Postclassic occupation, and equitably among commoners and elites. Individuals with dental modification included those who were born and raised in the Mayapan vicinity as well as migrants into the city. The diets of persons displaying this bodily adornment were not distinguishable from other residents.

These findings are important in terms of understanding the Mayapan sample in comparative context. The Mayapan patterns generally conform to Tiesler's (Reference Tiesler2001) conclusion that dental modification lost its association with high-status persons, particularly males, in the Postclassic compared to the Classic period. Inlays were no longer performed and tooth filing was undertaken by both commoners and elites at Mayapan, if relatively infrequently. Other investigations in Yucatan also reveal the tendency for more females than males to have filed teeth. For example, 52.2 per cent of females have modified teeth compared to 18.2 per cent of males in Tiesler's study of Postclassic cases reported from east coast (Caribbean Yucatan) sites.

While at Mayapan only females had filed teeth, the option was not a practice exclusive to either sex at contemporary sites across the peninsula. Potentially, the two individuals in our sample for which sex could not be determined may have been male. The presence of male effigy censers with filed teeth at Mayapan also underscores the likelihood that certain males adorned themselves in this way. Analysis of dental modification according to sex should also consider the possibility of blended or alternative gender identities, or cross-dressing especially for male ritual specialists, as is known in the art of the Maya area (Ashmore Reference Ashmore and Ardren2002; Geller Reference Geller, Gowland and Knüsel2006; Joyce Reference Joyce1998, 164; Looper Reference Looper and Ardren2002; Stockett Reference Stockett2005, 570; Stone Reference Stone and Miller1988, 75–6). Dressing and other presentation in gender-ambiguous or dual-gender ways may have served to embody personhood for members of society as a whole (or uniting cosmological or reproductive principles). Joyce argues (Reference Joyce2000, 78–81) that transcending binary gender identities in ritual practice was clearly intentional. It is possible that the males represented by effigy censers, concentrated at an architectural group likely to have been the nexus of Kukulcan priests at Mayapan (Peraza Lope & Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014a, 54), reflect men-women of special status of the sort described by Looper (Reference Looper and Ardren2002). Given that these entities do not bear the diagnostic markings of known Maya gods in the codices, they may have represented patron gods unique to the Kukulcan priesthood. An alternative and perhaps complementary interpretation may be that their filed teeth reflect the sacred breath or wind aspect closely linked to Kukulcan and his aspect as the wind god Ehecatl, so common across Mesoamerica (Taube Reference Taube1992, 59).

In general, dental and cranial modification become more regionally homogenous in Postclassic Mesoamerica, with serrated teeth and tabular erect cranial modification predominating, and Mayapan conforms to this pattern (Tiesler Reference Tiesler2014, 22, 240). However, the relative prevalence of tooth filing traditions at Postclassic Maya sites is remarkably divergent at the community level. Mayapan differs from Tiesler's comparative sample of east coast sites in its lower frequency of tooth filing (Tiesler Reference Tiesler2001; 40.9 per cent, 18/44, Fisher's Exact Test, p = 0.007). The popularity of the C pattern among females is reflected at Mayapan as well as at settlements on the northeast coast (Tiesler Reference Tiesler2001). The eastern sites of Laguna de On and Caye Coco conform to the Mayapan pattern for (pointed) tooth filing style and sex association, although tooth filing was much more common at these sites. A higher proportion of female skeletons from these two sites exhibit pointed tooth filing (66.7 per cent, 8/12) compared to males (10.0 per cent, 1/10) (Rosenswig et al. Reference Rosenswig, Briggs and Masson2020, appendix 1). Yet at the site of Santa Rita, an important regional capital with which Laguna de On and Caye Coco were affiliated, no individuals had filed teeth (Chase Reference Chase, Whittington and Reed1997, 24). In addition, more males exhibit dental decoration and more diverse forms of modification occur at Postclassic sites further to the south in Belize such as Lamanai and Chau Hiix (Havill et al. Reference Havill, Warren, Jacobi, Gettelman, Cook, Pyburn, Whittington and Reed1997; Williams & White Reference Williams and White2006). These findings suggest, on the one hand, that tooth filing was more popular at settlements in the Belize region compared to Mayapan, but also that this practice was not standardized between communities with respect to sexual identity or prevalence.

Unlike tooth filing, tabular erect cranial modification was widely practised (88.1 per cent, 37/42) at Mayapan (Serafin et al. Reference Serafin, Lope and González2012) and in hinterland populations (Briggs Reference Briggs2002; Rosenswig et al. Reference Rosenswig, Briggs and Masson2020). Why was cranial modification commonly adopted as a regional marker of social identity, while tooth filing was not? No clear explanations are apparent for the reasons for choosing to file teeth, but doing so appears to have been an individual (or family) rather than community-scale choice. The higher frequencies of dental modification at hinterland sites suggest that the city welcomed migrants from these allied territories, but even in these distant towns, many people had unmodified teeth. In other words, there are no clear ‘source’ towns for populations of persons with filed teeth. Given patrilocal residence patterns, women with filed teeth would have died and been buried at locations where they spent their adult married lives, but they may have undertaken the modifications before marriage. The lack of concentrations of skeletal remains with filed teeth further constrains the prospects for residential-scale analysis of this practice. Based on the present data, we infer that tooth filing was an elective form of ornamentation that was open to individuals, and that doing so did not cause social stigmatization, nor did it mark noble birth.

The relative scarcity of dental modification at Mayapan is also statistically different compared to earlier Maya sites. For example, the proportion of individuals with modified teeth at Mayapan (16.4 per cent; 10/61) is significantly lower than values reported for the northern Yucatan coastal Classic era site of Xcambo (Tiesler Reference Tiesler2005; 31.3 per cent, 31/99; Fisher's Exact Test, p = 0.041).

Modified teeth were similarly rare at two other, earlier urban settings in Classic period Mesoamerica, the political capitals of Monte Alban and Teotihuacan (Cid Beziez & Torres Sanders Reference Beziez, & L and Sanders1999; Martínez Lopez et al. Reference Martínez López, Winter, Antonio, Winter, Martínez López, Autry, Wilkinson and Juárez1996; Rodríguez & Serrano Reference Rodríguez and Serrano1975). While tooth filing correlates with higher social status at Monte Alban, this does not appear to be true for Teotihuacan. Teotihuacan, the larger of the two cities, is particularly identified as a multi-ethnic melting pot tolerant of diverse, household-scale expressions of social identity. Studies of burial practices and skeletal isotope analysis highlight the social diversity of this city's residents (e.g. Manzanilla Reference Manzanilla2015).

Mortuary practices at Mayapan similarly reflect an environment in which families freely diverged from one burial event to the next in terms of treatment and furniture of the deceased at individual residential groups (Hutchinson Reference Hutchinson, Masson, Hare, Peraza Lope and Russell2021; Smith Reference Smith, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962). Occasionally, household artefact assemblages point to ethnically distinct families who possessed concentrations of more unique types of pottery (Peraza Lope & Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014b, 144). Yet for most contexts, facets of the material culture of daily life such as ordinary, common artefacts and forms of residential architecture reflect an adoption of relatively uniform norms (Masson et al. Reference Masson, Hare, Lope, Masson and Peraza Lope2014, 194), as does the popularity of tabular erect cranial modification. Like mortuary practices, tooth filing was a more individual choice. Correlating with neither social rank nor place of birth (local, non-local), women with filed teeth at Mayapan were accepted into urban society.Decisions to file teeth at Mayapan may have been influenced by a desire to emulate popular and fluctuating styles, perhaps related to principles of fashion as applied to archaeology (e.g. Lesure Reference Lesure2015, 113). However, the superficial homogeneity of different variants of the ‘C’ pattern of tooth filing, the principal form observed at Mayapan and numerous other contemporaneous sites, masks subtle variations that merit closer consideration. Some, like Romero's C5 and C8 styles, resemble the simple triangular depiction of filed teeth visible on some of the city's (male) Chen Mul Modeled effigy censers. Others, such as F4, C6 and C4, exhibit varying degrees of elaboration and asymmetry of the mesial and distal corners. All of these subtle variations were probably referents to the same underlying symbolism, perhaps wind or breath. The females who bore these variations on the ‘C’ theme were adopting a prevailing regional style, and the possibility exists that they were ritual specialists. Modest variations may be related to the desire to personalize this theme, or other factors such as perception or skill of craftspersons or family members performing the filing.

When conflicts brought violence to the city, these women, along with others who did not modify their dentition, were susceptible to extermination and hasty burial in the city's mass graves. Female victims in Mayapan's mass graves included individuals born locally as well as migrants. An important mechanism by which women arrived at Mayapan would have been the practice of enslaving war captives. This status merits further consideration for individuals with non-local bone chemistry signatures, although documentary sources indicate that some slaves were also acquired from neighboring northern Yucatan polities (Roys Reference Roys, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962, 47). Female slaves frequently performed domestic services, and some were concubines (Roys Reference Roys1972, 27). Slave trade was also, unfortunately, a key component of economic exchanges between Mayapan (and other northern sites) and Gulf Coast merchants connected to central Mexico (Roys Reference Roys1972, 34–5; Scholes & Roys Reference Scholes and Roys1938). Cross-culturally, slaves are often displaced to locations far from their support networks so that they have diminished prospects for flight and refuge (Graeber Reference Graeber2011, 140, 145; Inomata Reference Inomata, Inomata and Houston2001b). It is worth considering that at least some females with filed teeth, and some lacking this trait, arrived at the city against their will.

Conclusions

City life, in the past as well as today, presents opportunities for amalgamations of hometown identities through processes of acculturation, assimilation, hybridity and the allure of urban cachet. The governors of pre-modern states such as Mayapan may have effectively promoted a narrative of cultural unity at the city, across the confederated polity and among hinterland allies. Such efforts are rarely complete in their transformations of individual or family-scale outlooks. Citizens and subject peoples may conform in some aspects of lifestyle and presentation and diverge in others, and urban leaders are rarely able to control every such choice; it is unlikely that they were motivated to do so. Tooth filing, like mortuary practices at Mayapan, represented one such tolerated arena of individual choice. This form of personal ornamentation contrasted with other aspects of appearance, such as cranial modification, that reflected a person's belonging to a prevalent regional majority of Postclassic Yucatan peoples.

As Stockett argues (2005, 573), it is more productive to focus on the study of social identity as a process that ‘mediated the tension between large-scale, social-defined and small-scale, individually enacted understandings of sex and gender’, rather than focusing more generally on women and binary concepts of sexual identity that have their roots in Spanish Colonial characterizations of Maya societal norms. This study at Mayapan answers Stockett's call by comparing complex patterns of corporeal presentations of identity at the regional and local scale. Normative practices were mediated by individual choice in the pluralistic urban setting of the capital city of Mayapan.

Acknowledgements

Radiocarbon dating and isotope analysis has been facilitated by funding from The Pennsylvania State University under the permission of Mexico's Consejo de Arqueología, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.