Byzantium's image as a society in defence from the late-sixth century onwards, both from a political and an ideological viewpoint, is persistent among Byzantinists.Footnote 1 This image is mainly due to the fact that imperial authority underwent two phases of large-scale territorial contraction, first at the end of late antiquity and then again during the late-eleventh and late-twelfth centuries; the latter leading to the empire's disintegration. These developments have led modern scholarship to view the reconquest of the late-tenth century as a kind of interlude, an exception to the rule, and are closely related to the scholarly debate as to whether the medieval Byzantine state should be seen as an empire at all.Footnote 2 Within this framework, the role of Roman imperial ideology on Byzantine military policies has been addressed with scepticism. The recurrent discourse of Roman imperialism, i.e. ecumenism, in Byzantine political jargon is usually regarded as the product of a fossilized, rigid ideological worldview of the imperial court, which was propagandistically employed as a rhetorical construct in order to justify small-scale expansionary warfare through the notion of reconquest.Footnote 3

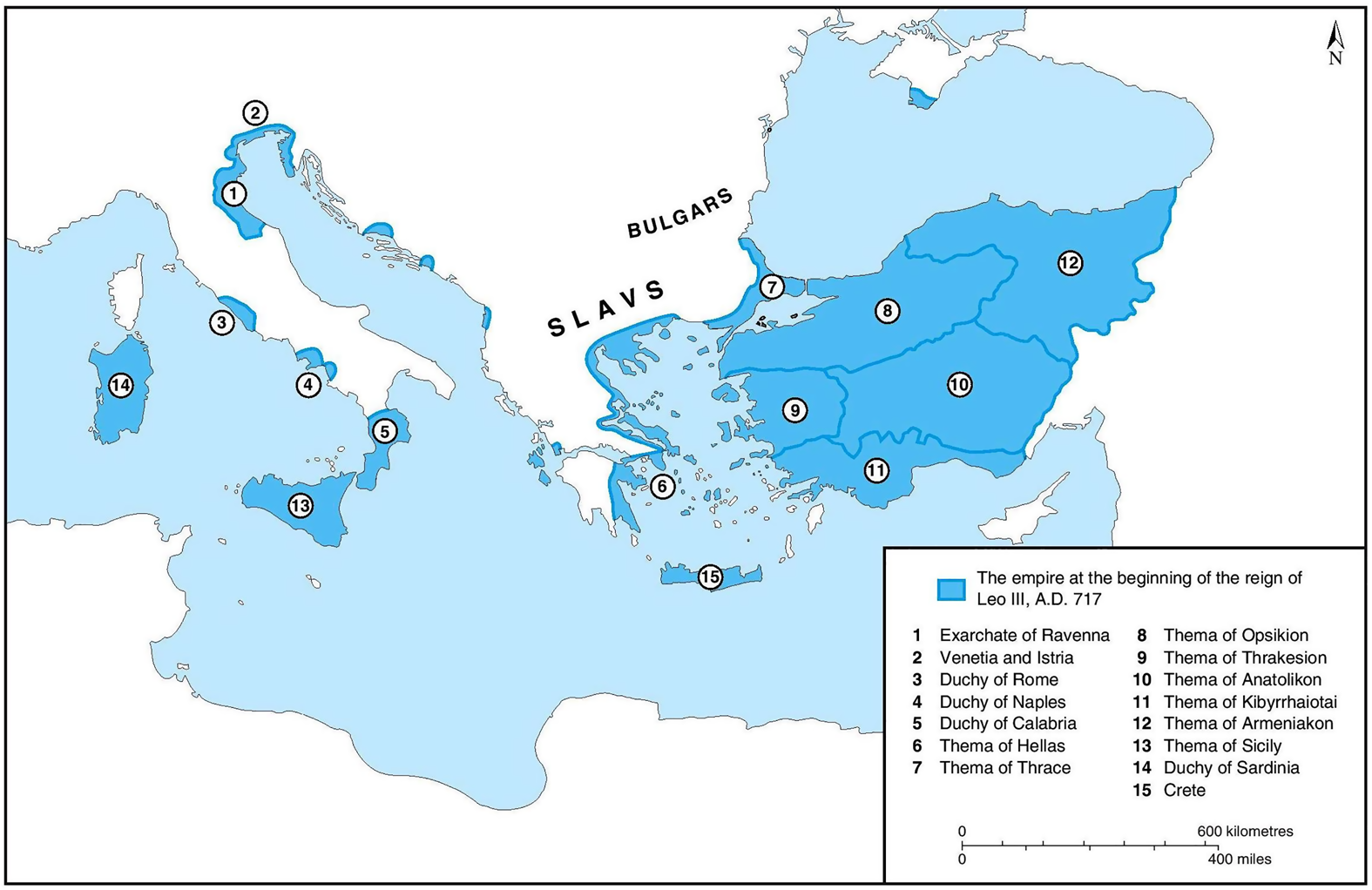

In light of the above, certain issues need to be raised. The first issue is whether the question of empire and imperialism in medieval Byzantium should be approached in a quantitative or a qualitative manner. From a quantitative perspective, for instance, the size and the expansionist policies of the medieval empire of Constantinople can hardly stand comparison with those of ancient Rome in the period of the late Republic or the early Principate. If we adopted a qualitative perspective, however, the image of a society in defence seems to be contradicted by the evidence showing the gradual expansion of the imperial city-state's realm from the eighth up to the mid-eleventh century. A look at the territories under imperial authority in the early-eighth century (map 1) and those in the tenth and eleventh centuries (maps 2 & 3) demonstrates that the rulers of Constantinople quasi doubled their realm and increased impressively the number of their subjects.Footnote 4 By comparison then, the post-seventh century Roman power élite of Constantinople appears to be much more imperialistic in terms of pursuing territorial expansion and the subjugation of new populations than the power élite of the late Roman Empire.

The second issue refers to the role of a common ‘identity’ in warfare. It is easy to question how far the empire's provincial masses identified with the ideals and policies of expansion celebrated through the discourse of reconquest and traditional Roman universalism. Especially, since the material gains from that type of warfare were mainly claimed by the ruling élite while the common provincials carried the heavy burden of taxation for financing the large imperial armies needed for such campaigns.Footnote 5 On the other hand, even though the traditional views that attributed the empire's survival to a broadly shared identity based on Christian ‘orthodoxy’ and the Greek lingua franca no longer hold currency,Footnote 6 scholars have been less prone to equally challenge the identification of the provincial masses with ideals of defence and protection of a superior Roman order, the Rhômaiôn politeia, or of a chosen Christian people, which are dominant in Constantinopolitan writings.

To begin with, the persistent modern image of post-seventh century Byzantium as an ideologically coherent society defending en bloc its common values seems to be related to an underlying tendency in modern scholarship to project upon the defensive activity of the medieval East Roman imperial state traits of modern national societies and nation-states. If this interpretation bears a considerable degree of anachronism, it is yet not fully unjustifiable if we consider that religion and nationalism demonstrate significant analogies as discourses of collective identification, especially when configuring the image of the group vis-à-vis an enemy as the negated external other.Footnote 7 Byzantine sources abundantly testify to the practice of the eastern Roman elite to highlight the Christian religion as the society's principal cultural value and a distinctive marker of Romanness not only in defensive wars against enemies of different faith, such as the Muslims, but even when the enemy was Christian and non-heretic.Footnote 8

However, the different social role and function of similar ideological tropes in structurally different socio-political orders is made evident when it comes to the attitude of the eastern Roman power élite towards expansionist warfare. For instance, for the emerging nation-states in the modern era the liberation of populations as (alleged) bearers of the same ethno-national identity was the main means to legitimize war for occupying the territory in which those populations resided.Footnote 9 Conversely, the main justifying argument for the expansion of the Constantinopolitan city-state's realm in the period examined here was the prerogative of the reigning city of New Rome and its emperor to claim back cities and regions that had once been under the authority of the Roman imperial power. The identity of the populations in the areas of reconquest, either old or new, was an issue of secondary importance.Footnote 10 This attitude was due to the Byzantine power élite's Roman political ideology which promoted identification with a vision of political community whose boundaries were coterminous with the – at any time – current political borders of imperial authority. That enabled a generic categorization as Roman subjects of all populations coming under the authority of the emperor of Constantinople. In this context, the main means to distinguish between first-class and second-class Roman subjects was religious doctrine, not ethnicity or indigeneity.Footnote 11

Taking this into account, the use of analytical terms such as empire and imperialism, when it comes to post-seventh century Byzantium, concerns the way we approach a medieval social order in which an imperial city-state exercised rule over a fluctuating realm with subject populations marked de facto by cultural diversity. As mentioned above, when modern scholars discuss Byzantine expansionism under the justifying rubric of reconquest, the focus is usually on the tenth century and the reconquest of the eastern provinces. The gradual re-imposition of imperial authority over a large part of the Balkan Peninsula in the eighth and the ninth centuries is often downplayed. However, it is a fact that Constantinople had lost control over the largest part of the Balkan Peninsula by the mid-seventh century and that imperial campaigns for the reinstatement of state authority there were motivated by the Constantinopolitan power élite's need to regain control over a lost territory, its natural resources, and its new, culturally diverse population. They had little to do, indeed, with a war whose primary goal was the liberation of fellow Christian-Romans, nor were they propagandized as such.

The latter holds true also for the eastern frontier. Given that the Chalcedonian doctrine was the main reason for the maintenance of an ideological bond between a part of the Christians under Muslim rule and the imperial city-state of Constantinople,Footnote 12 one would expect the idea of protection or liberation of fellow Christians in the East to be a central argument of justification of Byzantine warfare against the Caliphate. Especially, if one considers the background of late antique ecclesiastical historiography which was keen to highlight the Christian identity of populations under Persian rule as a justifying argument for Roman warfare against Persia in the fourth and early fifth centuries.Footnote 13 A look at post-seventh century Constantinopolitan historiography, however, shows that similar justifying arguments are strikingly absent. This indicates that the ideological role of shared religious identity in the configuration of the goals of Byzantine policy of expansion/reconquest needs to be addressed with caution. All the more so, if we consider that the evidence throughout the period from the eighth to the twelfth century demonstrates one thing: For the imperial power of Constantinople, the goal of expanding its control over lost territories and their human and natural resources, when the conditions for such an expansion were favourable,Footnote 14 marginalized issues of doctrinal beliefs or, for that matter, the ethno-cultural identities of the populations in the targeted areas.

Within this framework, one needs to consider that the unanimously acknowledged success of the imperial power in defensive war against the Muslims in Asia Minor refers to its ability to maintain centralized control over a contracted territory and its populations. It has been thoroughly studied how this goal led to defensive tactics that turned the largest part of Asia Minor into a war-theatre for many decades during the second half of the seventh and the first half of the eighth century.Footnote 15 According to a sober modern statement, the imperial regime of Constantinople was successful in protecting the capital and the interior of Asia Minor from Muslim occupation through the tactics of skirmishing warfare, but this was done at the cost of large human and material losses for the populations of Asia Minor.Footnote 16

This valid observation needs to be juxtaposed with present-day theories of a Byzantine ‘grand strategy’, which have been keen on highlighting the empire's ingenious policy of survival against immense external pressure.Footnote 17 That kind of analysis – even though it can have its own merits – concentrates on the political aspect of war and the grand-narrative of empire while marginalising the issues of lived and perceived experiences of imperial warfare by the provincial populations. The latter can hardly be taken a priori to have perceived and appreciated as successful a defensive policy that often caused them a lot of suffering.

Based on this, it makes sense to question how far the provincial populations identified with the ideals and power-political interests of the ruling élite in warfare for the defence of the imperial order. Instead of reifying common identity and regarding it a priori as an agent that predetermined common attitudes empire-wide, one should rather seek to discern whether there was a gap regarding lived and perceived experiences of warfare between the empire's power élite with its Roman imperial outlook and the largest part of provincial subjects – a mental gap directly related to the relationship between an imperial city-state and its provincial periphery.

Imperial vs. provincial perspectives

The perception of war by common provincials in Constantinople's realm was closely linked to the mechanisms for the reproduction of a consensus between rulers and ruled in the socio-political context of a pre-modern tributary state.Footnote 18 A main means through which the imperial city-state could justify the extraction of surplus from its provincial subjects and circumscribe their loyalty was efficient military protection. This consensus between the imperial power and its provincial subjects was, however, seriously questioned in the seventh and early-eighth centuries when the Muslim offensive reached its climax and the Balkan provinces were penetrated by Slavic groups.

In the Balkans, for instance, a significant part of the indigenous population does not seem to have put up serious resistance against the Slavic infiltration, insofar as the imperial power had been inefficient for quite a time to protect the territory from the raids of Avars and Slavs.Footnote 19 With regard to the Muslim expansion in the East, the author of a hagiographical text of the late-ninth century observed that the boundaries of the Roman power had been contracted due to the heresy of the rulers, that is, due to God's punishment.Footnote 20 If this is a topos stemming from the theocentric mentality of an iconophile monk, it entails, nevertheless, an implicit political criticism of the imperial power's failure to come up to its duty and protect a large part of populations under its authority.

Saints’ lives written in a non-Constantinopolitan context are even more important sources for exploring the mentalities of common provincials, insofar as such texts both reproduced and disseminated thoughts and attitudes that shaped the lived and perceived experiences of the populations of Asia Minor at the time of the Muslim offensive.Footnote 21 A good example is the collection of miracles of Saint Theodore the Recruit, written in the late-seventh century. The text summarizes in a picturesque fashion the reality of provincial populations in the course of the protracted Muslim offensive.Footnote 22 The author speaks of systematic raiding that took place yearly.Footnote 23 The enemy was able to winter in the city, kill or capture those that had not been able to take refuge in other places and devastate the site.Footnote 24

This reality is reaffirmed by non-Byzantine sources as well. The Chronicle of 1234, for instance, reports on two campaigns of Muawiya against Caesarea and Euchaita in the 640s.Footnote 25 In Caesarea he took captives from the surrounding area and laid it waste before capturing the city, slaughtering its inhabitants and plundering it. In Euchaita, the intruders were mistaken for friendly Christian-Arab forces and caught the people by surprise. They were able to enter the city without resistance, make plunder and take the women and the children as slaves, leaving the city lay ravaged and deserted.

There are plenty of other reports from both Byzantine and Arab sources that testify to the weakness of the imperial armies to protect significant numbers of provincials, which were constantly exposed to captivity and deportation or killing, the devastation of their crops and the long-term interruption of agricultural activity, the plundering and burning down of towns, settlements and estates, and the robbing of their livestock.Footnote 26 The most important proof of the situation experienced by the provincial populations of Anatolia at the peak of the Arab offensive comes, however, from the study of pollen evidence from certain areas in the 660s and 670s in particular. The absence of anthropogenic indicators points to the abandonment of sites due to the enemy raids, thus verifying the basic picture drawn by the written accounts.Footnote 27

In this regard, the grand-narrative of a coherent social order defending its common values seems to hide more than it reveals when it comes to the common provincials' experience of war and their commitment to the common cause of defending an imperial order that failed to properly protect them. Here, the latest arguments concerning the military reorganization of the empire in the early Middle Ages, the so-called theme system, need also be taken into account.Footnote 28 The older mainstream thesis presented the armies of the themata as the product of a mid-seventh century imperial reform which contributed essentially to the empire's survival. According to this approach, the binding of the soldiers with the arable land of the empire through an alleged centrally-directed allotment of so-called military lands in exchange for military service was considered as an essential measure that entrenched the ideological commitment of an army of peasant-militia to the empire's defence. This thesis promoted, implicitly or explicitly, a romanticized image of the themata as a quasi-national army dedicated to the defence of the empire as common patria.Footnote 29

However, the latest revisionist approaches have definitely debunked the theory of a military reform in the mid-seventh century.Footnote 30 From a military viewpoint, the empire's successful defence against the Muslim offensive was rather the result of the well-directed relocation of the eastern armies of full-time recruits, whose loyal service to the emperor continued to be circumscribed by the established Roman practice of regular payment in kind and/or in cash.Footnote 31 The dispersal of the armies of the magistri militum across the territories of Asia Minor and their concentration on regional defence prevented the permanent occupation of important towns and fortresses by the invading Muslim armies, which would have led to the permanent loss of whole regions.

As a result, the survival of the empire, i.e. of Constantinople's centralized political, military and fiscal authority over certain territories, needs to be approached – equally to the territorial expansion of the imperial authority in the following centuries – primarily as a matter of the emperor's firm control over loyal field armies as well as of élite patriotism towards the imperial centre. The loyalty of the élite of service, in particular of the military élite, to the political culture of the city-state of Constantinople was informed by this elite's vested interests in the imperial system, whereas it was also underpinned by the nature of the Muslim attack.Footnote 32 Within this framework, even though from the late-seventh century onwards the bulk of the recruits in the imperial armies came from the masses of Asia Minor and the Balkan provinces through various practices of centrally-directed recruitment (hereditary, forced or voluntary), this army mainly remained an instrument of the power élite of the imperial city-state, serving primarily its power-political interests and only secondarily those of the provincial masses.Footnote 33

A good case in point with regard to that is the notorious defensive action of Leo Phokas against the invading army of Saif ad-Daula in Anatolia in 961, in a period when the empire was militarily strong and on the offensive. While the field armies of Asia Minor were conducting an offensive campaign against the Cretan Muslims under Nikephoros Phokas, Leo Phokas crossed to Asia Minor with military forces from the Balkans to fill the gap. There, he used skirmishing methods in order to defend the imperial territory from the invading army of Saif ad-Daula. The latter was able to penetrate deep into Anatolia, plunder and devastate a number of settlements, and to take a considerable number of war prisoners.Footnote 34 The Muslim army was successfully attacked and defeated only on its way out of Byzantine territory.

Despite the successful outcome of the operation in power-political terms, one cannot help noticing that local populations and local economies had to suffer significant damages and losses. According to the account of Leo the Deacon, the defeat of the Muslims led to the liberation of all the captives and the booty that had been taken from the Romans. However, this booty was not returned to the local communities that had suffered from the Muslim attack. It was held by the army and the largest part was distributed among the common soldiers as a reward. The liberated captives were given provisions to return to their devastated abodes.Footnote 35 The victory of Leo Phokas was celebrated with a triumph in Constantinople where the war prisoners and the booty from his campaign were paraded.Footnote 36

This incident provides a good example of how the attitudes of provincial commoners towards warfare were shaped through their lived experiences and not by the images of imperial victories as propagated in Constantinopolitan triumphs, panegyrics and historiographical accounts. With this in mind, even though defending provincial territory was an overlapping interest of both the imperial power and the provincials, the latter's actions of defence should not be a priori attributed to broader ideological-political motives. Participation in the defence of their locality may have de facto favoured the perpetuation of Roman imperial rule over the region but this hardly means that their resistance to the invaders was motivated by the Constantinopolitan ideal of defence of the Roman political order, i.e. by broadly shared sentiments of loyalty to a community larger than the local/regional.

The late-ninth century Life of Saint Antonios the Younger sheds light on this. The saint, a sub-governor and military commander in the thema Kibyrraioton at the south-western coast of Asia Minor during the 820s,Footnote 37 was able to avert a Muslim attack against the city of Attaleia (or Sylaion). Striking in this case are the arguments exchanged in the negotiation between the head of the Muslim fleet and the Byzantine officer in their effort to justify or delegitimize the attack, respectively. According to the Muslim commander, the attack was justified because it was directed against imperial territory in order to avenge the attacks of the Roman emperor's army in Syria.Footnote 38 In this argument, warfare is perceived and presented as an issue between two broader political entities, the empire of Constantinople and the Muslim caliphate. The involvement and the suffering of the local community are regarded as a consequence of its Roman geopolitical identity.

The reported answer of the Byzantine commander (the saint) fully deviates from this power-political pattern. He considered the Muslim attack unjust because the local community bore no responsibility for the actions of the imperial army, i.e. of the political centre. According to him, ‘the emperor of the Romans ordered his officers whatever he wanted and this was done, he sent fleets and prepared armies against those resisting his dominion whether his subjects conceded to this or not’.Footnote 39 For this reason, God would not tolerate the injustice done to the local population by the Muslims.Footnote 40 As R.-J. Lilie has plausibly observed, this answer demonstrates the deviation of provincial mentality from the Constantinopolitan mentality of imperial warfare.Footnote 41 In another context, I have argued that this passage is an indication of the identity gap between Constantinople and the provincial masses, which warns against anachronistic approaches to the East Roman community as a national community.Footnote 42

The saint's statement points not only to the lack of identification of provincial populations with the offensive activity of Roman armies on far away fronts. It equally demonstrates that the determined defence of the locality against the Muslim raiders could and did take place without being motivated by the vision of defence of the Rhomaion politeia, i.e. of the Roman order. The whole argument of the local commander is not about defending the imperial order or the land of the Romans against foreign invaders. It is about the right of the local population, both the soldiers of the garrison as well as the civilians, to defend their hometown with the help of God whose assistance they were claiming as righteous Christians facing an attack they had not provoked. Beyond identification with local interest, i.e. local patriotism, religious identity was the main semantic means of contradistinction with the enemy at a broader level.

According to the account of the Life, the commander set young women next to men on the walls to give the enemy the impression of a strong garrison.Footnote 43 The employment of similar tricks in order to deceive the enemy about the own army's strength as well as the participation of civilians as militia in the defence of city-walls were widespread practices which are testified by military treatises and other sources.Footnote 44 Nonetheless, what seems to have primarily contributed to the Muslim commander's decision to abandon the attack was neither the indefinable strength of the local garrison nor the determination of the Byzantine commander to defend the city, but rather the offer of material rewards should the Muslims agree to withdraw.Footnote 45 Even though no precise information is provided about the kind and the amount of the reward offered in exchange for the enemy's withdrawal, one may justifiably presume that this must have been generous enough to convince the Muslim commander not to take the risk of an assault. Considering that it must have come from local resources, that is, from the local taxpaying population, it becomes evident that the latter had to accept further financial losses in order to maintain its freedom and local peace.

The account of the Saint's Life entails, therefore, a certain criticism of imperial warfare, which stems from a social reality, in which provincial communities were often in need to defend themselves with little support from the field armies of the imperial center while these armies were busy raiding enemy territory. This critical stance is all the more important, if we consider that it is presented as coming from the mouth of an imperial officer who commanded the soldiers of the local garrison. Even though it is difficult to assert the authenticity of the reported words of the saint, it is important that both he and the author of the text – probably a pupil of the former – represent provincial mentality.

Antonios was an immigrant Christian, born and raised in Palestine under Muslim rule. After crossing to the imperial realm, he was able to settle in the province of Attaleia and to advance socially due to his connection with the governor-general of the thema Kibyrraioton. As a provincial official, he visited Constantinople only once and stayed there for a few months.Footnote 46 This points to a person not fully assimilated to the Constantinopolitan culture of the ruling élite of service. Even though his Roman identity, as an identity of political allegiance to the emperor in Constantinople, was enhanced through his higher social status and his position in the provincial administration, he was not a fully integrated member of the ruling élite that made up court society.Footnote 47

It follows that the voice of the saint – evidently deviating from the normative Constantinopolitan discourse – may well be taken to echo the voice of common provincials who did not share the same political loyalty as the élite of service and had little understanding for the needs of a centrally planned imperial military policy. The latter aimed primarily to maintain or regain centralized control over territories and populations within a broader geopolitical sphere and was as much defensive as offensive.Footnote 48 Instead, the main concern of provincial populations was the preservation of local peace. Their loyalty to Constantinople as the centre of political power was primarily conditioned by the imperial city-state's ability to deliver effective protection or not.

Common good vs. local interest

The evidence presented so far provides a good point of departure for an analysis of information coming from Constantinopolitan sources, which indicates a lack of consensus between provincial populations and the imperial government regarding political actions of the imperial city-state in the name of the common interest of the Roman order. Theophanes the Confessor counted among the ‘evil deeds’ of emperor Nikephoros I (802–811) two measures related with imperial military policy: first, the forced transfer of indigenous Christian populations from Asia Minor to Greece in order to re-organize areas with Slavic populations that had newly come under imperial authority again; second, the organization of rural communities across the empire into fiscal units collectively responsible for financing their poor members enrolled for military service.

According to the chronicler's own words, in the year 809/10 the emperor:

removed Christians from all the themata and ordered them to proceed to the Sklaviniai (scil. Slavic settlements in the Balkans) after selling their estates. This state of affairs was no less grievous than captivity: many in their folly uttered blasphemies and prayed to be invaded by the enemy, others wept by their ancestral tombs and extolled the happiness of the dead; some even hanged themselves to be delivered from such a sorry pass. Since their possessions were difficult to transport, they were in no position to take them along and so witnessed the loss of properties acquired by parental toil. Everyone was in complete distress, the poor because of the above circumstances and those that will be recounted later on, while the richer sympathized with the poor whom they were unable to help and awaited heavier misfortunes.Footnote 49

This passage has received more attention for the political motives of the emperor's action, namely the restoration of imperial control over parts of the southern Balkan Peninsula and the integration of Slavic populations into the imperial system than for the stance of the transferred populations.Footnote 50 The latter points, however, to the extremely unpopular character of the transfer which common provincials seem to have perceived as an attack against their well-being.

If Theophanes’ information on the common people's reactions needs to be addressed with caution due to the author's agenda regarding Nikephoros I, there is yet good reason why his picturesque report should not be dismissed as a mere invention owing to his hostility towards the emperor. The fact that whole families were forced to leave their regional homeland, sell their properties, and resettle to regions that were distant and foreign to them indicates that a good deal of truth lies in the core of the report and that the imperial initiative can have been anything else but popular. This is supported by the fact that the forced transfer of 809 had been preceded by an effort of the same emperor in 805 to motivate voluntary resettlement to Greece, which had failed.Footnote 51 Therefore, the reactions of the people should be examined from the point of view of consensus or lack thereof between rulers and ruled by the enactment of centrally-directed policies in the name of common interest as viewed from the perspective of the imperial centre. Nikephoros I's action was evidently informed by the Roman raison d’état, that is, the interests of the imperial city-state regarding the restoration of Roman authority over the Balkan provinces.

For similar reasons, the emperor took another measure. According to Theophanes, he “ordered a second vexation, namely that poor people should be enrolled in the army and should be fitted out by the inhabitants of their commune, also paying to the Treasury 18 ½ nomismata per man plus his taxes in joint liability”.Footnote 52 This is the fiscal measure that, as John Haldon has convincingly argued, actually introduced the thematic armies in the early-ninth century as an army-model based on a new system of local recruitment, which was intended to make the financing of the soldiers of the provincial forces a collective responsibility of local communities.Footnote 53 It was, therefore, a measure aiming to strengthen the numbers and improve the efficiency of provincial army units that protected the interests of the Roman realm. However, the reported reactions of the first poor recruits show that this measure was unpopular as well.Footnote 54

From the common people's stance towards such actions of the central government, we may therefore deduce a mental gap between the Constantinopolitan notion of the common interest of the Roman order and the attitude of provincial subjects that prioritized local communal interest. In this context, the imperial government's political project of population transfer for the consolidation of Roman authority in reconquered regions or its fiscal measures for strengthening the empire's military forces were perceived as coercive actions of a distant power centre that were directed against the interest of local communities and their members’ well-being. This said, the fact that the forced population transfer under Nikephoros I seems to have mainly concerned Greek-speaking Chalcedonian Christians demonstrates that the Constantinopolitan state hardly reserved a privileged treatment for the – at least in theory – more Romanized group of its subjects in comparison to other ethno-culturally or confessionally diverse groups.Footnote 55

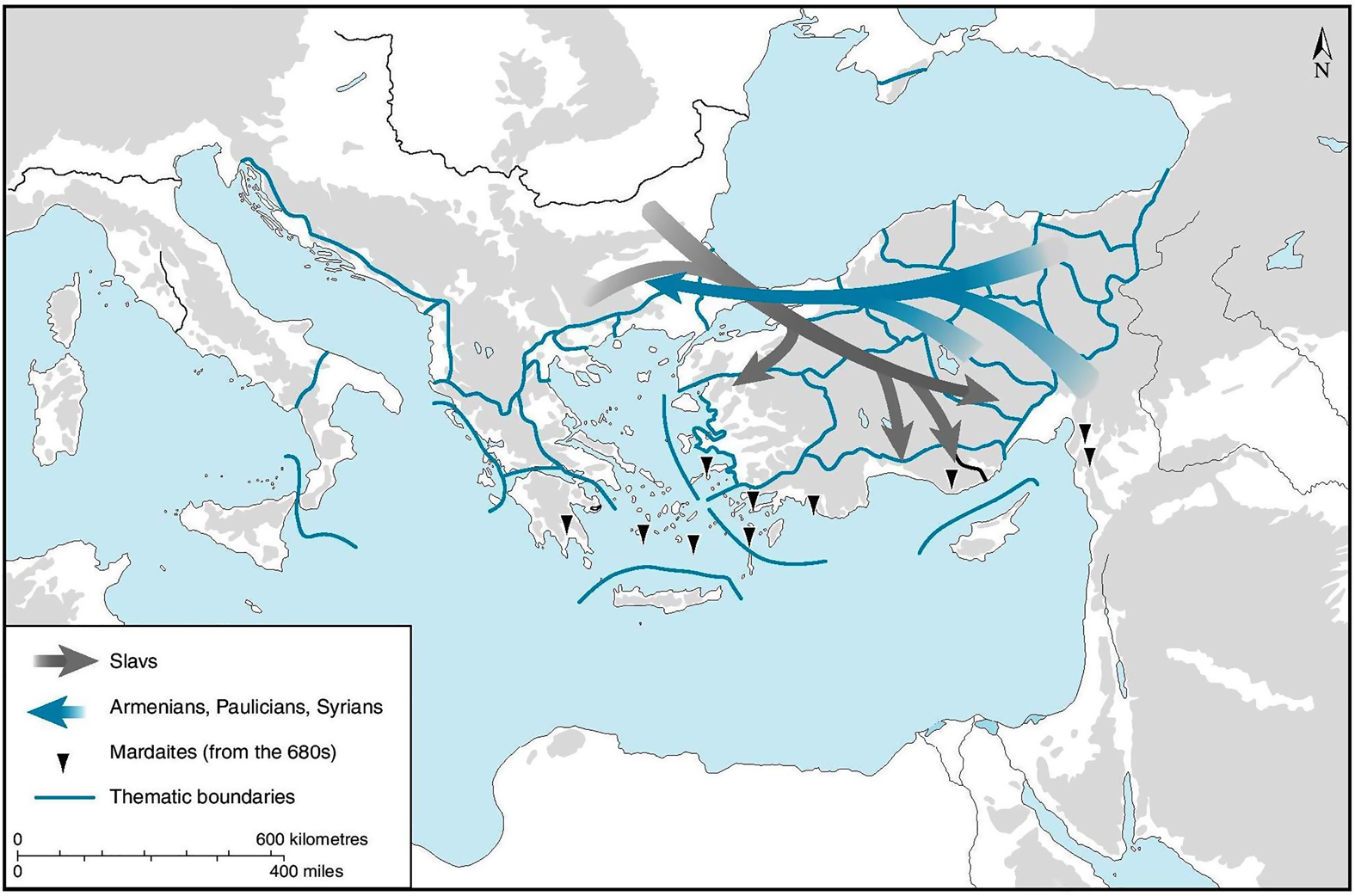

Nikephoros I's action was part of a series of population transfers from the Balkans to various areas of Asia Minor and vice versa between the late-seventh and the tenth century. Large groups of Slavs were transferred and resettled to regions of Asia Minor, while Syrians, Armenians and the ethno-religious group of the Paulicians were compelled to move from areas of eastern Asia Minor to the Balkans, mainly to the region of Thrace (cf. map 4).Footnote 56 This practice of compulsory resettlement and mixture of ethno-culturally diverse populations within the imperial realm provides, therefore, further evidence of the imperial disposition of Constantinople's policy. The power élite used various groups to repopulate regions, to increase the numbers of the productive subject population in its core realm and to strengthen its military forces. To achieve these strategic goals, the state paid little attention to issues of cultural or confessional homogeneity within its realm or, for that matter, to the protection or privileged treatment of a certain culturally dominant group of subjects.

The marginal role that the ethno-cultural bonds between the power élite of Constantinople and its Greek-speaking Chalcedonian subjects played in the configuration of the goals of imperial warfare is also made evident by the crisis of the twelfth century. Michael Angold has explained the reluctance of formerly Roman provincials in Seljuk Anatolia to be reintegrated into the imperial authority of Constantinople as a problem of identity, which contributed to the failure of the imperial power to drive out the Turkish invaders.Footnote 57 This observation raises an important analytical issue, namely the difference between an approach to collective identity as an objective and reified phenomenon or as a subjective phenomenon, i.e. as identification in terms of social and in particular political action. Historians are usually keen to attest collective identities in an objective fashion (based on common cultural markers such as language, script, religion etc.). However, the actual agency of such an objective identity of commonly shared markers in socio-political terms is often questioned by its evident weakness to acquire a subjective dimension, i.e. to be translated into mass political loyalty that is able to promote common action in the name of the group.

In the case of twelfth-century Byzantium, a lack of identification between the Constantinopolitan power élite and provincial populations becomes apparent if one takes a closer look at the Komnenian emperors’ choice of objectives both in offensive and defensive warfare. The latter reveal the imperial mentality that continued to pervade the political culture of the Constantinopolitan city-state despite the radical territorial contraction of its realm. This mentality marginalized the role of a common ethno-cultural identity between the power élite and populations within and outside the borders of the state in the former's military policy. This is made evident by the Komnenian regime's effort to restore imperial authority in the East, which did not prioritize the reconquest of Anatolia, where indigenous population had been for centuries predominately Greek-speaking and Chalcedonian. The current power-political interests of the imperial city-state in the context of the crusading movement made, instead, expansionary warfare in the areas of Cilicia and North-Syria a priority, even though the majority of the populations there were Armenian and Syriac (Arab-speaking) and did not share the orthodoxy of the Chalcedonian creed.Footnote 58

The distance between the power-political interests of the Constantinopolitan city-state and the interests of provincial populations is further confirmed by the priorities of the former in actions of defence. The events of the Second Crusade demonstrate that the security of common provincials came second in the strategic concerns of the Constantinopolitan city-state and the power élite's raison d’état. Emperor Manuel I Komnenos’ main objective was to transport the Crusader armies as soon as possible to Asia Minor in order to prevent attacks against the imperial city. Moreover, he concluded agreements with the German and the Frankish Crusader kings, which guaranteed that the Crusaders would return reconquered cities in Asia Minor to Byzantine authority.Footnote 59 Even though he agreed to provide supplies to the German army that was the first to cross to Asia Minor, in the case of the Frankish army he made a different deal. According to Odo of Deuil, he conceded to the Franks the right to buy all necessary supplies from local markets along the way at a fixed price. If a town or a castle should refuse to sell goods or if there was no market in the area, the Crusaders were allowed to plunder and take what they needed, their sole obligation being not to occupy the plundered piece of land.Footnote 60

This extraordinary agreement turned the provisioning of a large foreign army from a problem of the centre into a problem of certain provinces in western and southern Asia Minor. Modern historians have argued that the agreement was due to the inability of a medieval state to supply two large foreign armies simultaneously.Footnote 61 However, this argument is flawed since it tends to ignore the fact that, by denying to deal with this problem centrally, the emperor transferred all the burden on certain provinces and their population, thus exposing them to the danger of Crusader attacks. This is all the more true if we consider that those areas suffered from regular Turkish raids and that local markets there might not have been in position to cover the needs of a large foreign army.Footnote 62 Moreover, by setting a fixed price for the exchange of goods and making its violation a justifying cause for plunder, the emperor increased the danger of conflict with local populations on route. Not least because no Byzantine forces accompanied the crusading army to control and negotiate the attitudes of both locals and crusaders – the latter being infamous for their undisciplined character.Footnote 63

This practically meant that provincial populations urgently needed to organize local defence and seek refuge to fortified places in order to avoid attacks and plundering in the absence of protection from the imperial centre. According to the account of Odo of Deuil, it was only strong fortifications that prevented the Crusaders from attacking and plundering certain cities.Footnote 64 It comes then as no surprise that local communities along the route of the Frankish army were hostile and ready to cooperate even with the Turks against the Crusaders. Odo of Deuil claims that those actions had been orchestrated by emperor Manuel due to his animosity against the Crusade.Footnote 65 However, Choniates, whose criticism of Manuel's attitude towards the Crusaders is well known, has nothing to say about a plan of the emperor to join forces with the Turks against the Franks.Footnote 66 Moreover, Manuel's action to send an embassy to Louis VII in late 1148 warning him of an imminent Seljuk attack provides further evidence that no such plan existed.Footnote 67

It seems more probable that the Byzantine emperor was indifferent to the fate of the crusading expedition as soon as he was able to secure the safety of the imperial city-state of Constantinople – the soul and embodiment of the empire – and to ensure that the Crusaders would not occupy territory currently under Constantinopolitan authority. In this power-political context, it was not the emperor who orchestrated the Byzantine provincials’ hostility towards the crusading army. Nor should the actions of the locals be explained as owing to their harmonious co-existence with, or any kind of preference towards, the Turks.Footnote 68 These actions should rather be interpreted as a result of local politics of survival in the de facto absence of efficient protection from the imperial centre. Because of his war against Roger II of Sicily in the West, Manuel was not willing to devote any forces either to shadow the Crusaders or to check Turkish forces crossing his borderlines.Footnote 69 For this reason, the provincials of western and southern Asia Minor needed to side with the Turks occasionally in the face of a threat that appeared to be common for both and therefore able to unite them in action.

The case of the Second Crusade offers, therefore, another insightful example of how the Roman raison d’état of the Constantinopolitan city-state could make the protection of large parts of provincial population a low-priority issue. Such practice inevitably challenged the consensus between the rulers in Constantinople and those currently or formerly ruled by them in the empire's territorial core (the Balkans and Anatolia), triggering the latter's lack of commitment to centralized Roman political rule. Various other reported cases of provincial populations in this period resisting cooperation or even fighting against the imperial army make this evident.Footnote 70 In contrast with the seventh century though, the emperors of the twelfth century also saw the loyalty of members of the provincial élite incrementally fade away, as the phenomena of provincialism and separatism demonstrate.Footnote 71 This was of major importance for the different outcome of the twelfth-century crisis which led to the empire's political disintegration.

Conclusion

In this paper I have tried to show that the study of east Roman provincial populations’ actions and attitudes in war between the seventh and the twelfth century needs to avoid oversimplifying approaches to the medieval East Roman order as a culturally and ideologically-bounded society in defence. The goals of imperial military policies, dictated by the imperial city-state's raison d’état, were not a priori in favour of the well-being of provincials and this is an issue closely connected with the structure and function of a pre-modern imperial state. Provincial experiences of war, both lived and perceived, varied greatly according to geographical location and period and were fairly differentiated from those of the Constantinopolitan centre. As a result of this, the ideological commitment of provincial populations to the imperial state was primarily determined by their local interest and not by a broadly shared identification with Constantinopolitan ideals about the perpetuation of a superior Roman order.

Appendix: MapsFootnote *

Map 1: The East Roman Empire in the early 8th century

Map 2: Areas of expansion of imperial of authority from the 8th to the 11th c.

Map 3: The East Roman Empire at its territorial height in the early 11th century

Map 4: Forced transfers of culturally diverse populations within the empire (7th-9th c.)