When Kurt Weitzmann studied the iconography of the Lamentation he saw it as the final episode in a series of scenes depicting the events following the Descent from the Cross: Joseph of Arimatheia and Nikodemos carrying the dead Christ, then the myrrhophores and the Virgin joining the procession and finally all the figures stopping short of the open tomb, sitting on the ground and lamenting over Christ's body in a highly charged emotional scene. Weitzmann identified all the phases of the subject found in illustrated manuscripts before the scene appeared in monumental art in the mid-twelfth century.Footnote 1 Nowadays, thanks to Henry Maguire's research, we know that homilies on the Virgin's lament, which were included in Good Friday services from the eleventh century onwards, played a crucial role in the creation of this theme.Footnote 2

I refer to the example of the Lamentation because the two approaches mentioned above are the ones that have for the most part dominated the study of visual narrative in Byzantine monumental art. The former, which could be defined as descriptive and classificatory, analyses images according to iconographic types, seeking their archetypes and recording their development, while the latter, often developed in response to the taxonomical approach, looks for the textual sources of the images with the aim of understanding their intrinsic meaning or content.Footnote 3 It is also a fact that nowadays in iconographical analyses of Byzantine monumental painting scholars have largely turned to looking for the text behind the image, while they have paid little attention to the question of how an image or a series of images, a narrative cycle, retells and represents a text.Footnote 4 Attempts to answer this question have mainly relied on the taxonomical methodology, which was basically elaborated by Weitzmann in his studies on pictorial narrative in the manuscripts of the early Christian and Byzantine periods.Footnote 5 As a result, visual storytelling in monumental painting has been seen as dependent on book illustration and lengthy narrative cycles unfolding across church walls have usually been attributed to the copying of some, often hypothetical, painted manuscript.Footnote 6

Moreover, Weitzmann's typological approach subsumed an evolutionary model, i.e. the transition from a narrative mode that uses separate images representing a single moment of a story to a cyclic method of narration with pictures showing successive episodes in a continuous space. Focusing mostly on illustrated manuscripts Weitzmann defined the different types of narrative images and saw a progression moving from a monoscenic to a polyscenic narration mode, which he thought was artistically superior.Footnote 7

Widespread endorsement of this concept and of the classical system of monumental iconographic programmes laid down by Otto Demus in his seminal book on Byzantine mosaic decoration resulted in a corresponding evolutionary model becoming tacitly accepted in the study of visual narrative in monumental painting.Footnote 8 This model was based on the premise that there was a transition from the ‘laconic’ and dogmatic iconographic programmes of the period after Iconoclasm to the garrulous story-telling of Palaiologan monumental art with a continual accretion of narrative scenes.Footnote 9 In this scheme the beginnings of the narrative turn is often traced to the Comnenian period, when increasing interest in the individual and her/his emotions led to a ‘humanisation' of religious art and traditional iconographic programmes being extended by the addition of highly charged emotional scenes of the Passion and painted Lives of saints.Footnote 10

It must also be acknowledged that the taxonomies have such deep roots in the study of Byzantine monumental art that even in recent studies they have impeded a historical understanding of visual narrative. For example, although recently Nektarios Zarras and Ivana Jevtić have correctly noted and commented on the innovations in narrative tropes appearing in Palaiologan art – such as a) the development of smaller sub-cycles of scenes within the Passion cycle, b) the lengthy inscriptions annotating the scenes and c) the continuous narrative developing like a frieze with the figure of the protagonist repeated in order to convey physical movement and time sequences – they nevertheless attribute the models that inspired these developments to painted manuscripts or trace their roots back to Early Christian art.Footnote 11 Similarly, they ultimately interpret the narrativity of these Palaiologan cycles as reflecting the influence of the liturgy or the spirit of the age, without posing what – to my mind – is the central question: i.e. why these things should appear at this time and in this way.Footnote 12

In order to tackle this question, I would suggest that we first look for research tools in literary criticism and more especially in narratology, i.e. the study of the narrative structure of oral and written texts.Footnote 13 In this approach narrative is defined as a representation of an event or series of events and it comprises two distinct elements: the story and its telling, i.e. the so called narrative discourse, by a narrator, who is not necessarily the author of the narrative or even identified and present in it.Footnote 14 In addition to these three aspects, story, narration and narrator, what is crucial to a theoretical understanding of narrative in the visual arts is its recipient, i.e. each and every viewer, who will annotate the images with text and dialogue, arrange the plot and finally craft the story.Footnote 15

Starting from these premises, we might first of all agree that, in the Middle Ages, both in Byzantium and in the West, the story behind any visual narrative in monumental art was that of the divine dispensation for the salvation of mankind. Starting from the Creation, it focused on the eventful life of its hero, Jesus Christ, culminating in the drama of the Passion, with an auspicious ending for the faithful in the Last Judgement.Footnote 16 Thus the story also extended into the future, including the lives of a medieval society, a public familiar with the basic points of its plot. Therefore the story of divine Providence constituted both the framing device and the master narrative that contained and delineated all the individual narratives that have come down to us in images from monumental painting/mosaic.Footnote 17

Despite the fact that the nucleus of this story remained the same throughout the Byzantine period, its narration in art varied not just from one period to the next but also from one monument to another in the same period. If, for example, the same viewer attempted to retell the story of the life of the Theotokos through the iconographic cycles of Daphni Monastery near Athens, the Chora Monastery in Constantinople and the Perivleptos in Mistra, s/he would create a very different narration in each case. This discrepancy is not only due to the differences in medium, date or style that separate these programmes, but also to the narrative strategies adopted in each of them.

More specifically, in the monastery church at Daphni, located ten kilometres outside Athens and dated to the third quarter of the eleventh century, one of the earliest middle Byzantine pictorial biographies of the Virgin is preserved.Footnote 18 The six scenes from Mary's Life, shared between the naos and the narthex, are presented out of chronological order and each confined to their architectural framework (fig. 1).Footnote 19 Thus, they are stages in the visual discourse with conceptual and narrative independence. A minimum of action is discernible, since the unusually naturalistic figures are depicted motionless against a gold ground. The viewer's only direct eye contact with the scene is through the gaze of some secondary figure, while all the dramatis personae often seem to have become frozen in time. The Nativity of the Virgin is a typical example (fig. 2): the figures appear closed in on themselves and absorbed in their own thoughts, their gazes do not meet, and only one of the servant girls standing behind the reclining Anne looks out of the composition in the direction of the viewer. If we were to put a text to these scenes it would not be dialogues or monologues spoken by the characters involved, but the words of an external narrator coming from the apocryphal text of the Protevangelium or a Gospel account. Moreover, as the scenes are interwoven spatially and typologically with scenes from the Life and Passion of Christ, this cycle is ultimately open to multiple readings by the viewer.Footnote 20

Fig. 1. Attica, Daphni, Monastery church. View of the interior, late eleventh century. Photo: Ktiv [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 2. Attica, Daphni, Monastery church. The Nativity of the Virgin, late eleventh century. Photo: Municipality of Haidari [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], from http://haidari.culhub.gr/

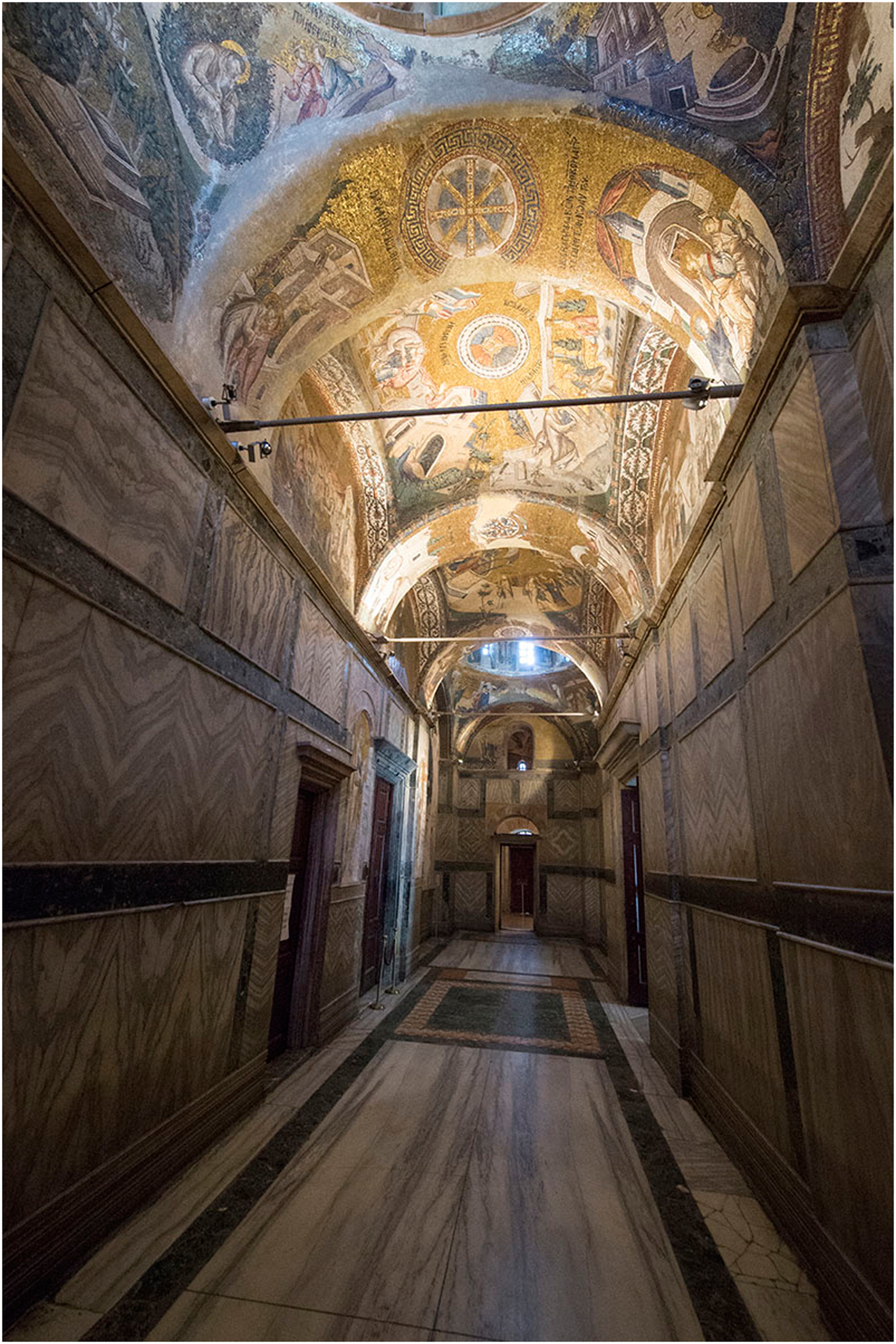

In the Chora Monastery in Constantinople (1315–1320/1) on the other hand the narrative time of the story of the Virgin has been greatly extended, as it contains 22 scenes that unfold in circular fashion on the walls of the inner narthex (fig. 3).Footnote 21 The narrative faithfully follows the Protevangelium and continues in the exonarthex in the same circular fashion with the story of Christ's childhood, in which Mary once again plays a leading role.Footnote 22 The narration is tightly knit, as the events succeed one another in chronological order, both by virtue of their position in the architectural framework and also thanks to the movements and gestures of the protagonists, which lead the viewer from one episode to the next. The postures of the three figures in the scene of Joseph taking the Virgin away from the Temple are typical (fig. 4): the elderly widower and his young son are represented moving to the right towards the next scenes, which take place in their house, while turning back to look in the direction of the young girl, Mary, who is following them.Footnote 23 In this way, the scenes/episodes follow one another in a continuous fashion and the pictorial discourse acquires a rhythmical, uninterrupted flow. However, not all the episodes are allotted the same narrative time. Some can be brief, such as those depicted on the small surfaces of the arches that support the vaults; for example, the emotionally charged scene of the infant Mary taking her first steps (fig. 5).Footnote 24 Others are greatly extended and occupy a whole dome, allowing room to create secondary narratives within each event, such as the young Jewish girls in the procession talking animatedly to one another in the scene of the Presentation in the Temple (fig. 6).Footnote 25 These supplementary events are sometimes turned into embedded narratives.Footnote 26 The episode of the lament of the mothers over their dead children in Herod's Massacre of the Innocents, unique for the size and detail of the representation, is one such ‘story within a story’ of Mary and her new-born son.Footnote 27 Thus, the narrative in the Chora monastery combines multiple narrative times and narratorial voices. The narrators can take part in the events mainly as secondary characters in the plot, who turn their gaze on the beholder, or watch the action with her/him, as for example the young woman, Anne's maidservant, who peers over a low wall at the embrace between Mary's parents on Joachim's return from the wilderness.Footnote 28 However, the chief narratorial voice comes from an external narrator, to whom we should attribute the long passages from the Gospel inscribed in some instances in the background to the scenes.Footnote 29 One more detail that distinguishes the narration in the Chora Monastery is that it does not restrict itself to rendering the action, but includes some painted descriptions of the surroundings that are important in the development of the story. The verdant gardens in the scenes of the Annunciation to Anna, the Virgin Caressed by her Parents and the Entry into the Temple, with their many flowers and magnificent birdlife, including peacocks, pheasants and partridges, are painted references to the literary images of nature with which the Virgin is compared in Byzantine theological texts.Footnote 30 Thus they correspond with the horizon of expectations of the medieval viewer, who was familiar with these literary metaphors, and similarly they multiply the narrative levels in the story.

Fig. 3. Constantinople, Chora Monastery (Kariye Djami), 1315–20. View of the inner narthex. The cycle of the Life of the Virgin. Photo: Dick Osseman

Fig. 4. Constantinople, Chora Monastery (Kariye Djami), 1315–20. Joseph taking Mary home. Photo: Dick Osseman

Fig. 5. Constantinople, Chora Monastery (Kariye Djami), 1315–20. Virgin Mary taking her first steps. Photo: Dick Osseman

Fig. 6. Constantinople, Chora Monastery (Kariye Djami), 1315–20. The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple. Photo: Dick Osseman

By contrast, in the Perivleptos in Mistra, painted some years later (ca 1360–80), despite the increased number of scenes, the narrative discourse is simpler.Footnote 31 The story unfolds in linear fashion, with independent episodes placed in chronological order in the upper register of the walls of the church (fig. 7).Footnote 32 The scenes, divided from one another by frames, are all of the same size. Moreover, they are related to the text of the Protevangelium by the large extracts inscribed on the backdrop to almost all the scenes, like the continuous voice of a narrator in the background.Footnote 33 Ultimately, despite the fact that the visual narrative in the Perivleptos renders almost every phrase of the text, it does not have the sophisticated character and the complexity seen in the Chora Monastery.

Fig.7. Mistra, Perivleptos church (c. 1380). View of the interior, the cycle of the Life of the Virgin. Photo: Sharon Gerstel

The question that arises from the above is whether the different methods of narration and the degree of narrativity can reveal anything about the function of the work, its creators, its audience and finally its date. In other words, could this kind of narratological analysis also be a tool for understanding the work of art in social and historical terms, and not simply another method of classification?

I propose that we approach this question in two ways: 1. by examining whether similar narrative structures are found in contemporary literature. 2. by looking for information about how contemporary viewers read the story in monumental narrative paintings. Though, unfortunately, Byzantine literature has little in the way of these sorts of written testimonies, any evidence of the Byzantine viewer's response to narrative works could make a decisive contribution to the decoding of visual narrative in Byzantium.Footnote 34

I will start with the first question. It is true that the twelfth century was a period that saw revolutionary changes in the field of literature, changes that were already in the making by the end of the eleventh century. The quality, quantity and indeed the originality of narrative genres of this period were so important that Margaret Mullet called it the age of ‘novelisation’ of Byzantine literature.Footnote 35 In addition to the emergence of the romantic novel and narrative poetry, such as the Epic of Digenis Akritis, new, elaborated and sustained narrative features emerge in other genres, for example in historiography and hagiography.Footnote 36 The emergence of the new narrative genres is due both to contact with the corresponding texts of ancient literatureFootnote 37 and the rediscovery of tragedy as an instrument for rhetorical display of pathos and lament.Footnote 38 Thus, as Panagiotis Agapitos has observed, the romances of the twelfth century: ‘…do not represent stories as narrative fiction. They constitute plots in “poetically constructed language”… built out of a series of tableaux vivants in which various πάθη and ἤθη were acted out in strict observation of rhetorical rules’.Footnote 39 The dependence of twelfth-century novels on the Byzantine interpretation of tragedy as rhetorical drama also influenced their narrative structure. That is to say, they are arranged in books, each of which is organised in a defined spatial sequence and a clear arc of time, usually over a single day, and includes episodes, similarly fully chronologically defined, filled with monologues, dialogues, laments and songs, connected one to another with a minimum of action.Footnote 40 The self-contained, episodic arrangement, the rhetorical dramatization of monologues and the use of a narrator to describe the action in these texts are also accounted for by the fact that they were intended to be read out loud in the literary salons of the Comnenian aristocracy, the so-called theatra.Footnote 41 In addition to influencing the dramatized form of the novels, knowledge of the tragic form affected other texts of the period and little plays emerged complete with protagonist and chorus, all texts intended for reading aloud or for some sort of performance in the literary get-togethers of Constantinople.Footnote 42

In my opinion, the way in which the stories of the love-struck couples in twelfth-century novels are told corresponds exactly to the way in which the narrative cycles are organised in the art of the period. Arranged in independent episodes with a well-defined narrative time-frame and unified space, dramatized speeches and minimal action, like a series of tableaux vivants, just as Agapitos has described them, the narration of the Comnenian novels could well be compared to the pictorial biography of the Virgin at Daphni, discussed above, and would be even closer to the narration of the Passion in the Church of St. Panteleimon in Nerezi (1164).Footnote 43 Commissioned by a member of the Comnenian imperial family, Alexios Angelos Komnenos, the painted programme of Nerezi emphasizes the human sacrifice of Christ by means of its prominent position and the size of the scenes of the Passion, which are embedded in a cycle of the Great Feasts and arranged in chronological order (fig. 8).Footnote 44 Each scene forms a conceptual and narrative entity, in which the figures, with their dramatic expressions and their restrained movements, give the impression of having been stopped in their tracks, having just delivered a dramatic monologue.Footnote 45 Thus storytelling and painted cycles share the same rhetorical mode of narration and it is not accidental that both were intended for and connected through patronage relationships with the upper echelons of society in the twelfth-century capital.Footnote 46

Fig. 8. Nerezi, church of St. Panteleimon (1164). The scenes of the Passion: Deposition from the Cross and Lamentation (detail). Photo: Sharon Gerstel

We might also find correspondences between the narrative structure of the same type of text, i.e. the vernacular romances of the late Byzantine period, and the strategies deployed in the visual narratives of that period. In Palaiologan romances the plot is developed in linear mode, the narrative units are not divided into dramatic episodes and storytelling flows continuously.Footnote 47 For the most part it is the same narrative structure that is applied to the painted cycles of the Palaiologan period, in which a continuous narrative very often prevails, i.e. the episodes in the story are depicted without dividing lines against a shared backdrop, in which the figure of the main character is repeated to indicate successive events.Footnote 48 The most highly elaborated examples are the late thirteenth/early fourteenth-century cycles of the Life and Passion of Christ in monuments on Mount Athos, in Thessaloniki and Serbia, the majority of which are connected with the workshop of Michael Astrapas and Eutychios (fig. 9).Footnote 49 Furthermore, in the romances of the late Byzantine period, more refined narrative structures also emerge, reminiscent of the arrangement of episodes in the mosaics of the Chora Monastery in Constantinople, i.e. with embedded narratives and alternating narrators that ‘constantly reshape the audience's experience of the story through shifts in dramatic immediacy’.Footnote 50

Fig. 9. Thessaloniki, church of St. Nikolaos Orphanos (c. 1310–20). View of the interior, the cycle of the Passion (continuous narrative). Photo: Anna Schön [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], from Wikimedia Commons.

The dense dialogues and the role of space in the development of the narration is another common element between narrative texts and visual storytelling in the Palaiologan period. As in the texts, the story in the visual narrative unfolds through lively dialogues, implied by movements and gestures or by lengthy inscriptions that annotate the scenes.Footnote 51 On the one hand these inscriptions transmit the text of the gospel, representing the voice of the external narrator, while on the other, in some instances, they also suggest a dialogue between the figures depicted.Footnote 52 The important role played by dialogue as a vehicle for the narration in visual storytelling is also reflected in the integration of scenes in which the only action represented is a conversation, such as the scene that illustrates Christ teaching his disciples after the Washing of the Feet (fig. 10).Footnote 53

Fig. 10. Staro Νagoričino, church of St. George (1317/18). The Washing of the Feet. Photo: Georgi Serdarov [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Similarly, the colourful descriptions of space in the late Byzantine romances were not only a device for the creation of a theatrical stage for the action but played a crucial role in the development of the narration.Footnote 54 From the point of view of structure these descriptions did not sketch out scenery isolated from the narrated acts, but rather followed the movements of the wandering heroes, reflected their emotional state and were often interrupted by internal monologues or dialogues.Footnote 55 In the same way the elaborate architectural frames in the narrative scenes of Palaiologan art are instrumental in the storytelling in the way they highlight the protagonists of the events, emphasise their emotions and join up the action (fig. 10).Footnote 56 Moreover, certain motifs of space in the novels, such as the castle, loaded with allegorical meaning and symbolism, give the narrative depth and require the audience's or reader's cooperation in order to decipher them.Footnote 57 Painted landscapes, such as the garden full of flowers in the scenes of the Life of the Virgin mentioned above, may have the same function, given that they were intended to transmit similar allegorical messages to the medieval viewer.Footnote 58

The complexity of narrative structure in late Byzantine novels is probably due to the new conditions in which these texts were being received, as they appear to have been written for reading in private.Footnote 59 The transition from public performance to silent reading also has parallels with the general feeling created by the painted narrative cycles of each period. Thus, the Palaiologan iconographic programmes, with their complex narrative tropes and the numerous cycles covering the whole surface of the walls of the churches, give the impression of having been created to be read and that the viewer, like the reader of a book, can come back to them and re-read them, one by one or in a completely different order.Footnote 60

The audience/readership for the vernacular fiction of the late Byzantine period should first of all be sought in the imperial court circles of Nicaea in the thirteenth century and after that, in the fourteenth century, in the same environment in Constantinople.Footnote 61 In these social contexts narrative texts would take on an allegorical interpretation of a Christian nature, which would juxtapose the chequered search for love with man's attempts to get closer to God and gain eternal life.Footnote 62 These allegorical readings, combined with the didactic benefits of the love stories, which the anonymous authors push at every opportunity,Footnote 63 justify romantic storytelling as a form of literary writing and probably explain the fact that it became the model for narrative works with edifying content: literary texts such as the Verses On Chastity, ‘a tale of love, yet absolutely chaste’, as the author, Theodore Meliteniotes (ca. 1330–1393), a high-ranking official of the Patriarchate in Constantinople, says himself. This poem, which faithfully follows the narrative structure and adopts the motifs of vernacular romances,Footnote 64 suggests that fiction and particularly the romances found a wider reading public than previously imagined, reaching even the innermost circles of the church.Footnote 65

Despite the fact that these narrative texts were likely to have been widely distributed, there is no doubt that comparing the depiction of Holy Scripture in monumental art with literary genres of an entirely different nature and content may seem somewhat surprising and perhaps even hard to understand.

So it could be interesting to look for parallels between narrative strategies in painting and in texts with religious content. One obstacle standing in the way of this is the fact that narratological analyses have mainly been carried out on secular works of fiction. Even when it comes to saints’ lives, the material that lends itself best to such approaches, very few of them have been studied by scholars from this point of view.Footnote 66 On the other hand scholarship has in many instances identified some commonality between hagiographic texts and romantic storytelling.Footnote 67 Despite their profound ideological differences, stylistic and thematic similarities in works from these two categories show that the narrative innovations of any given period were not limited to a single literary genre.Footnote 68 This conclusion, which first of all ‘legitimises’ comparing narrative literature with religious painting, is confirmed by two texts with religious content, which have narrative strategies in common with the secular texts and works of art of their day.

The first comes from the pen of Theodore Hyrtakenos, a minor intellectual among the Constantinopolitan intelligentsia of the early fourteenth century.Footnote 69 I am referring to the ekphrasis on the garden of St Anne, a text with allusions to visual images and literary topoi from contemporary romances. The similarities with the latter are so close that it has been described as a ‘mini romance’ despite its Christian subject matter.Footnote 70 Anne's garden is described in the same terms as the gardens associated with the heroines of the romances; it acquires the same symbolisms as they do and is compared by the author to Anne's mental state, thus acquiring the same narrative function as the garden in secular literature and the architectural backdrops in Palaiologan monumental religious painting.Footnote 71

Moreover, as far as the twelfth century is concerned, we have an example of a text with religious content which, although not a typical narrative work, nevertheless recounts the Divine Passion in precisely the way we have seen used in the romantic novels and monumental art. And this is Χριστὸς πάσχων (Christos Paschon), the only surviving ‘tragedy’ from the Byzantine period. It is a cento poem on the Passion of Christ in dialogue form, consisting of more than 2500 iambic verses, mainly based on the tragedies of Euripides, and the majority of which are voiced by the Virgin.Footnote 72 The text constitutes further evidence of twelfth-century interest in the tragic form and has been described as ‘a rhetorical recital of unconnected dramatic episodes in narrative form’.Footnote 73 The minimal action and the unrolling of the story in monumental monologues/laments voiced by the Virgin and other figures, i.e. the rhetorical dramatization of the story of the Passion, undoubtedly has parallels with the way it is rendered in visual terms in contemporary monuments.Footnote 74 Whether or not it can be shown to be true, the notion that dramatized renderings of Holy Scripture, such as Christos Paschon, or more generally the rediscovery of drama as a form of narrative discourse in the twelfth century had an important influence on the iconography of narrative scenes remains a seductive hypothesis and an open question awaiting further research.Footnote 75 But what I can assert with confidence is that a contemporary saw the narrative scenes in a twelfth-century church as dramatized episodes of Holy Writ. I am referring to Nikolaos Mesarites (c.1160–post-1216), who described the mosaics of the Holy Apostles, Constantinople in an ekphrasis towards the end of that century.Footnote 76

This text is very well known, as is the whole debate over its relationship not just to lost images, but also to the earlier and briefer description of them by Constantine the Rhodian.Footnote 77 According to Liz James, the simple and laconic description by the Rhodian is accounted for by his tendency to see miracles in the scenes and to show them to his audience, while Mesarites, working in the rhetorical practices of his day, composed an ekphrasis in a more colourful and narrative fashion.Footnote 78

However, I believe that Mesarites is doing something more than that. He is writing a novel about the life of Christ, a story composed of independent episodes, which are the scenes from the church he is describing. This story has coherence because he is careful to connect the episodes/scenes up in a causal order, something that is a fundamental characteristic of narrative texts.Footnote 79 This relationship does not rely solely on the chronological order of events, but also on iconographical motifs repeated in the scenes. In other words, in order to move on from the Baptism to the next event, the miracle of Christ walking on the waters of Lake Capernaum, Mesarites says that he himself has fallen into the River Jordan and ended up in the Galilean lake, i.e. he connects the events with the iconographical common denominator between the two scenes: water.Footnote 80 At another point the very space of the church itself becomes the link connecting the episodes in the visual narrative because it is the setting in which they unfold. Thus, when finishing his account of the scene of the Women at the Tomb he invites his listeners to hasten with the myrrhophores because: ‘Just as they are making their way to the disciples, the Savior, emerges from some obscure and out of the way corner of the building and welcomes them with the words “All hail”’.Footnote 81

After he has connected up all the episodes depicted in the mosaics in such a way as to form a coherent narrative, he sets out the description of each one as a brief drama.Footnote 82 He describes in detail the protagonists, their gestures, movements and expressions and completes the narrative discourse of each episode with the words spoken by the various dramatis personae. Sometimes these are dialogues, often only emblematic phrases spoken by Christ, words that set the story and the time rolling in the mind of his audience/readers.Footnote 83

The close relationship between Mesarites’ descriptions and similar scenes in later monuments has been already noted by some scholars and was taken as evidence for the dating and development of the corresponding iconographic subjects.Footnote 84 Yet once again the text of Mesarites can offer us much more than that. First of all it gives us some hints as to how the audience of such scenes could craft a story out of a series of still pictures, i.e. it gives us space to explore the mental mechanisms that are in play when a Byzantine viewer reads a visual narration. And secondly it demonstrates that the way stories are told, whether in written texts, oral formulations or paintings, is historically and socially contingent. Therefore, as mentioned above, there is little doubt that finding similar evidence of the Byzantine viewer's response to pictorial narrations would contribute significantly to any attempts to decode visual storytelling in Byzantium.

To sum up, the above analysis has discovered common narrative modes between works of art and literary texts both in the Comnenian period and in the Palaiologan era. This discovery raises many questions: e.g. Could the rediscovery of drama as poetic discourse and the performative presentation of narrative texts in the literary salons of the Comnenian aristocracy put across the theatrical character of visual narrative in the period? On the other hand could the key to understanding the innovations in the narrative modes of the Palaeologan monumental painting lie in the changes in the reception of literary texts in the late Byzantine period, the probable move to private reading and their dissemination beyond a small circle of educated nobles (unlike in the Comnenian period), changes which have been thought to be possible reasons for the emergence of continuous narrative, the emphasis on dialogue and the importance taken on by the descriptions of space in narrative texts ?

These are seductive hypotheses for further exploration and what is certain is that studying narrative strategies in visual works of art and in literary texts side by side could open up new avenues for a better understanding of both of them.