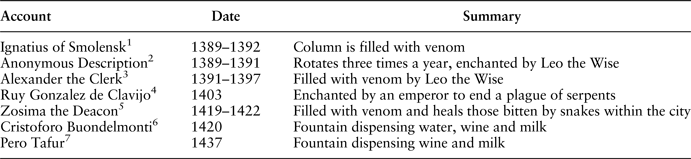

A monumental bronze coil stands amid what remains of the old hippodrome in Istanbul (fig. 1).Footnote 1 Now approximately five-and-a-third metres tall, it was once two metres taller and surmounted by three outward-facing serpent heads (fig. 2). A fragment of one head is in the archaeological museum nearby (fig. 3). The headless stump is today called the Serpent Column. It began its long history at the sanctuary of Apollo in Delphi, where it served as the monumental base for a tripod dedicated to Apollo in commemoration of the Greek victory over the Persians at Plataia in 479 BCE.Footnote 2 About eight hundred years later, in the fourth century CE, the Roman emperor Constantine (r. 324–37) had the column moved to its current location in Constantinople.Footnote 3 Another thousand years later, by the 1390s, the monument's original association with a specific military victory was largely forgotten. Many contemporaries instead saw it as a talisman against snakes and a remedy for snakebites (Table 1).Footnote 4 Three Russian visitors to Constantinople—Ignatius of Smolensk, Zosima the Deacon, and Alexander the Clerk—claim that the column was in fact filled with venom. Alexander the Clerk, the Spaniard Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo, and an anonymous Russian author further noted that a previous Byzantine emperor had enchanted the Serpent Column as a talisman. Even after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Serpent Column continued to be a talisman against snakes and snakebites well into the Ottoman period.Footnote 5

Fig. 1. Istanbul, Serpent Column. Credit: Author

Fig. 2. Cambridge, Wren Library, Trinity College, O.17.2 (Freshfield Album), dated 1574, folio 6 recto. The Serpent Column as depicted in the Freshfield Album. Credit: © Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge

Fig. 3. Istanbul, Archaeological Museum. Upper mandible of a surviving head from the Serpent Column. Credit: © Diliana Angelova.

Table 1. Accounts of the Serpent Column as Talisman

1 Majeska, Russian Travelers, 92-3.

2 Majeska, Russian Travelers, 142-5.

3 Majeska, Russian Travelers, 164-5.

4 Estrada, Embajada a Tamorlán; Strange (trans.), Embassy to Tamerlane, 71.

5 Majeska, Russian Travelers, 184-5.

6 Gerola, “Le Vedute.”

7 Tafur, Andanças é viajes; Malcolm Letts (ed. and trans.), Travels and Adventures, 143.

Technical aspects involved in the making of talismans—the introduction of efficacious substances, the performance of arcane consecrating rites, the presence of a sage ritual expert—play a prominent role in these brief accounts of the Serpent Column as a talisman. For medieval people, talismans were a technology created through the practical application of scientific knowledge—knowledge about the properties of things and images that arise from their relationships with natural forces and entities, including stars, planets, plants, animals, and elements, as well as demons, symbols, and efficacious words.Footnote 6 Seeing something as being a talisman often involved embedding it within an ecology by imagining its relationship with non-human forces. In this article, I examine how the Serpent Column as talisman is a product of such imagined ecologies.

While previous researchers have already addressed the history of the talismanic Serpent Column, few have approached it according to medieval understandings of what constituted a talisman. Earlier studies tend to regard it through the lens of folklore and the anthropology of religion and magic, whereby the monument's talismanic aspect is aligned with broad, often trans-historical, notions of magic and superstition.Footnote 7 In reaction, some recent studies have sought to view the monument within the context of local belief systems, but tend, in the process, to conflate the Serpent Column with other types of efficacious objects, particularly apotropaia and religious objects. I argue here that a talisman is in fact a different kind of object.

Although many talismans can be apotropaia, the two categories are distinct.Footnote 8 An apotropaion—literally, something that averts—need not be a talisman, and vice versa.Footnote 9 The apotropaion is a purely functional category: it averts. Talismans are instead etiologically and ontologically defined. They have a more complex relation to the wider world due to their special origins and properties.Footnote 10 For example, Christian symbols, such as crosses, are often supposed to be apotropaic, but they need not be talismanic. A cross repels evil because it is sacred, and not because of its special properties or its relation to natural forces and entities. While talismans such as the Serpent Column often have aversive properties—and often function as apotropaia—, they do not have to be apotropaic in order to be talismans. For example, two Russian accounts noted that the Serpent Column rotated three times a year.Footnote 11 A turtle talisman was said to go through the streets of Constantinople eating garbage at night.Footnote 12 A talismanic column in Damascus reportedly made donkeys and horses urinate if they circumambulated it three times.Footnote 13 A talisman clearly need not be apotropaic. Collapsing the distinction between apotropaia and talismans risks losing sight of what makes a talisman.

Other studies of the Serpent Column as talisman have emphasized its similarity to religious objects and relics, particularly the brazen serpent.Footnote 14 Nevertheless, existing textual sources from the Byzantine period do not explicitly compare the Serpent Column to the brazen serpent, nor do they describe it as a relic or religious object. However, even if unstated, such associations may have influenced contemporaries’ understanding of the monument. As in medieval medicine, religious symbols, texts, and rituals often played a prominent role in the creation and use of medieval talismans. Contemporaries may have often blurred the boundaries between religion, magic and science in everyday life. Indeed, a number of surviving religious and magical objects clearly conflate these different categories, and this article does not seek to dismiss similarities between the talismanic Serpent Column and religious objects.Footnote 15 Nevertheless, exclusive attention to the monument's religious potentialities downplays the technical aspects of the Serpent Column that connect it to other talismans (i.e., its enchantment by an expert and the idea that it was filled with venom). While the sacred might license, enhance, complement, or justify the use of medicines and talismans, it was essential for neither a medicine to be a medicine, nor a talisman to be a talisman.

In taking up the question of how contemporaries might have understood the Serpent Column as being a talisman, I pursue two inter-related lines of inquiry: first, what characteristics defined what a talisman was, and second, how might those characteristics apply to the monument. The first question deals with the main features of Byzantine talisman science. The second attends to the open-ended, associative thinking that might underlie contemporaries’ recognition of talismans.

The following article is structured in four parts: I first consider the general outlines of Byzantine talisman science, where I show that Byzantines primarily understood talismans in terms of their active properties, and how those properties were configured in relation to non-human intermediaries. The second part examines the pre-talismanic history of the Serpent Column in Byzantium, while the third section discusses other Constantinopolitan monuments that acted as talismans. The final section considers how these various notions of talismans as well as the monument's physical properties, location, and appearance might relate to its recognition as a talisman.

What is a talisman?

What did it mean for something to be a talisman in Byzantium? The classical Greek terms for talismans, telesmata and apotelesmata (τɛλέσματα, ἀποτɛλέσματα), from which our modern word talisman is ultimately derived, come from the verbs telein and apotelein (τɛλɛῖν or ἀποτɛλɛῖν). Both refer to the ritual completion, consecration, or initiation of an object, especially cult objects or items intended for amuletic or magical use. While the term remained in usage in the Byzantine period, especially in classicizing or historical texts, it was overshadowed by stoicheion (στοιχɛῖον), a word that designated a wide variety of things, such as physical elements, basic principles, demons, astral entities, talismanic statues, or letters of the alphabet.Footnote 16 Paul Magdalino has identified stoicheiōsis (στοιχɛίωσις) as the Byzantine name for talisman science.Footnote 17

But what did it mean for Byzantine people to refer to a talisman as a stoicheion? Researchers have debated several possibilities. According to Claes Blum, the primary sense of the word referred to inscribing magical signs, letters, and characters in the process of enchanting the talisman.Footnote 18 Richard Greenfield, commenting on Blum's work, has instead favoured another interpretation—rejected by Blum—namely that stoicheiōsis relates to the ‘fixing’ of astral powers.Footnote 19 I see little reason to impose a strict meaning for stoicheiōsis against other potential meanings. Stoicheiōsis may have been suited to designate talisman science because of its ability to suggest multiple aspects related to the making of talismans. In addition to Blum's and Greenfield's understandings of the term, stoicheiōsis also connotes instruction and teaching, and might, therefore, have suggested specialized learning.Footnote 20 It may have also evoked the four physical elements, which linked the planets and stars above to the things on the earth below.Footnote 21 That many of these stoicheiōtic things—elements, demons, astral entities, and letters of the alphabet—were involved in linking or attaching natural forces to an object could indicate that stoicheiōsis was more broadly understood as being a way of linking objects to natural forces.

In the talisman sciences of the medieval Mediterranean, these linkages were supposed to endow an object with special properties.Footnote 22 Byzantine talisman science combined the theory of special properties, the idea that talismans and other materials had unseen properties arising from their hidden elemental composition and orientation, with two concepts: first, cosmic sympathy (συμπάθɛια), the idea that secret affinities or resonances connect things in the universe; and second, natural antipathy (ἀντιπάθɛια), the notion that some things naturally oppose or counteract each other.Footnote 23 Specialists and laypeople alike used both concepts to explain interactions in the natural world whenever temporal or spatial distance intervened between cause and effect.

Sympathy was an especially prevalent explanatory concept. The writer Nikephoros Gregoras (ca. 1295–1360) describes sympathy, in his commentary on Synesios of Cyrene's treatise on dreams, in terms of attraction: ‘just as iron is [attracted] by a magnet, so also this or that is [attracted] by this or that material (ὕλης), this or that design (σχήματος), or this or that speech (φωνῆς).’Footnote 24 The idea of likeness, especially between an image and its prototype, was central to many Byzantines’ conception of sympathy.Footnote 25 The scholar Michael Psellos (d. ca. 1081) noted, ‘though substances (ὕλαις) are often separated, the distance between them does not prevent them from acting upon each other (…) an image (ɛἰκὼν) and an imprint (τύπος) convey the operation of magic (τὴν ἐνέργɛιαν τῆς μαγɛίας) to the archetype.’Footnote 26 Psellos’ image and imprint can be understood in analogy to James Frazer's two broad categories of sympathetic magic: mimesis or resemblance and contact or contagion.Footnote 27 These two types of relationship were believed to enable sympathetic linkage between two things physically separated in space.

Different philosophical traditions furnished different explanations for the invisible links between sympathetic objects. In antiquity, Stoics argued that elemental forces, constituting a larger soul, linked different parts of the cosmos, while Neoplatonists emphasized non-physical linkages between the material and immaterial world, principally by way of demons and other minor divine beings.Footnote 28 These different explanatory models co-existed in Byzantium.Footnote 29 Moreover, as with other forms of occult knowledge, these different understandings of sympathy appear to have occurred across the social spectrum, not only in elite, learned circles, but also in humbler and less literate contexts.Footnote 30

Regardless of the differences between these conceptions of how talismans might work, they share the idea that talismans are linked to, and act within, a larger system involving non-human operators. The talisman's primary range of application is the non-human: While the human audience is often the talisman's beneficiary, or ultimate target, the talisman is believed to act on connections, through non-human intermediaries in configurations of various, often local, networks of interactions. Stated another way: talismans belong to a type of ecology. Humans cannot see the links within this ecology, but must instead imagine the talisman's action within its non-human domain of application.

The Serpent Column as fountain

From the time of the Column's arrival in Constantinople to its earliest-attested appearance as a talisman in the 1390s, it is largely absent from the textual record.Footnote 31 During this period, it seems to have been sitting in plain sight.Footnote 32 It probably initially retained its associations with the sun, Apollo, Delphi, and victory against the Persians.Footnote 33 It may have also been considered apotropaic, as snake imagery in the medieval Mediterranean often was.Footnote 34 It inherited such a role from the guardian serpents and dragons of the ancient world.Footnote 35 By the eighth century, if not earlier, locals began to give many of the monuments in the Hippodrome occult interpretations, especially as tools for telling the future.Footnote 36

During this time, the Column was turned into a fountain.Footnote 37 It may have been already part of a string of fountains with its initial installation upon the hippodrome's central barrier, an area known as the euripos (ɛὔριπος), a term that otherwise designates a turbulent strait or narrow sea.Footnote 38 The euripos fountains further incorporated the Theodosian obelisk, the masonry obelisk, both still standing in the hippodrome, and the now-destroyed Skylla group, which portrayed a sea monster attacking Odysseus and his crew.Footnote 39 The fountains and statues, such as the Skylla group, would have given the euripos a marine ambience, perhaps ultimately due to an ancient association between the chariot races and Poseidon.Footnote 40 Poseidon, the earth-shaking god of deep oceans, was also a ‘tamer’ and a ‘frightener of horses’.Footnote 41 Within this maritime setting, the Serpent Column as a fountain might have recalled the sea serpents believed to inhabit the earth's oceans.Footnote 42

For much of its early history in Constantinople, the Serpent Column belonged to this wondrous fountain. Memory of its original role as a dedication to Apollo probably persisted for some time, especially given the traditional connection between hippodromes and the sun.Footnote 43 The tendency to give monuments in the hippodrome occult readings, especially on account of their pre-Christian origins, and to ascribe apotropaic force to threatening animal imagery in general, could also suggest that some of the elements that would have enabled contemporaries to identify the Serpent Column as a talisman were already in place. As it stands, however, direct evidence of such interpretations prior to the 1390s has not come down to us.

Snakes, eagles, lions, and storks

While we do not have clear evidence that medieval spectators recognized the Serpent Column as a talisman until the 1390s, we do for other monuments nearby. A bronze statue of an eagle killing a snake, also in the hippodrome, was principle among them.Footnote 44 The statue established the precedent for a talisman against snakes in the hippodrome.Footnote 45 In his De signis, the writer Nicetas Choniates (1155–1217) described the statue after its destruction by crusaders in the thirteenth century.Footnote 46 Choniates first records how Apollonius of Tyana enchanted the statue with secret rites and demons and then described how snakes were so terrified of the statue that they were afraid to leave their burrows. While Choniates does not deny that the statue was ritually consecrated as a talisman, his lengthy ekphrasis tends to downplay that explanation for its efficacy.Footnote 47 Choniates in fact gives two explanations for its efficacy: first, its consecration, and second, its antipathetic visual impact. The text does not explicitly choose between them.

The poet Manuel Philes (ca. 1275–1345) also plays upon the idea of antipathetic statuary in his description of a fountain decorated with carvings of snakes and lions. The poet notes that the stone snakes desire to move, but are frozen in terror lest they slip from the rock to ravenous lions, who gape at their would-be meal from below.Footnote 48 Although bestowed with life through the sculptor's art, both the snakes and lions are immobilized: the snakes in anticipation of slipping and dying, the lions in readying themselves to catch their prey. Here, Philes deploys the idea of opposition or antipathy in the animal world in order to temper the topos of the enlivened work of art.Footnote 49 His playful description pertains to the fictive content of the work, and not to its actual place within a type of ecology. Philes’ description of the fountain shows that contemporaries could imagine or entertain the antipathetic qualities of a work without necessarily supposing that it was a talisman or that it was actually efficacious against real animals. Nevertheless, it may have been easy enough for contemporaries to make that cognitive leap from first recognizing the theme of antipathy in a work to imagining that it had the actual ability to repel vermin.

Another talisman, mentioned in the Patria, a tenth-century description of Constantinople, as well as the Chiliades by the twelfth-century writer John Tzetzes (ca. 1110–80), complemented the eagle talisman in keeping the city free of snakes.Footnote 50 Both texts describe how snakes once infested the city. The swarming snakes attracted a mustering of ravenous storks. However, the storks, eventually growing tired of their food, proceeded to drop the snakes into the local water supply or onto people in the street. In desperation, the inhabitants appealed to Apollonius of Tyana who fashioned a statue of three storks facing each other that thereafter kept storks out of the city.Footnote 51

Each of these authors evokes antipathy to describe an artwork's impact on animals. They principally see fear as the underlying cause for the snakes’ avoidance or immobilization. Nevertheless, Philes does not describe his fountain as a talisman. His play upon the themes of antipathy and vivacity or liveliness is restricted to his elaboration on the work's content. The mere presence of snake imagery therefore did not make something a talisman, or even an apotropaion. An agonistic or antipathetic theme could be a sufficient source of diversion on its own. In contrast, Choniates, Tzetzes, and the Patria describe fully-fledged talismans, in which forces of nature are manipulated and plugged back into a larger ecology.

Serpent Column as pharmakon

The Fourth Crusade in 1204 drastically altered the urban landscape of Constantinople.Footnote 52 Almost two centuries later, the hippodrome was a grassy ruin, an ideal home for reptiles. The Serpent Column sat alongside obelisks and empty plinths as one of the last visible remnants of the bronze menagerie that had once existed there. The fountain had dried up; the Skylla group had vanished.Footnote 53 By the 1390s the Serpent Column reappears in the written record, first in a series of Russian accounts, and then in three reports written by Spanish and Italian observers in the fifteenth century (Table 1).Footnote 54 While none of these sources are written from the perspective of a local, the fact that visitors from different regions make similar statements suggests a common Byzantine source.Footnote 55

As already noted, three Russian observers stated that the column was filled with venom. Zosima the Deacon added that if someone bitten by a snake within the city limits touched the monument, he or she would be cured. For those bitten outside of the city, there was no cure.Footnote 56 The Florentine Buondelmonti noted that it was once a fountain that dispensed water, wine and milk, while the Spaniard Pero Tafur mentioned only milk and wine.Footnote 57 The Russian Anonymous Description alone states that the column rotated three times a year, while another version of that text even gives the exact days on which it moved.Footnote 58 The Anonymous Description and that by Alexander the Clerk both state that the emperor Leo the Wise (r. 886–912) enchanted the Serpent Column. Leo supplanted Apollonius of Tyana's role as a talisman-maker in the Late Byzantine period.Footnote 59 By the thirteenth century, his name was connected to several magical texts and a series of prophecies penned a century or so earlier.Footnote 60 At approximately the same time, he began to be credited with making talismans and other marvellous inventions.Footnote 61 The Spaniard Gonzalez de Clavijo also mentioned that an emperor (without specifying which one) enchanted the statue in response to a plague of serpents.Footnote 62 Clavijo's reference to a plague of serpents recalls not only earlier stories of other talismans in Byzantium, but also the fiery snakes that led Moses to erect the brazen serpent (Numbers 21:4–9). While no texts explicitly compare the Serpent Column with the brazen serpent, the biblical precedent might have underscored or justified its efficacy as a talisman.Footnote 63

However, the Serpent Column and the brazen serpent differ crucially in their appearance and in how people were supposed to engage with them. In many Byzantine representations of the brazen serpent, we see the serpent raised up on a pole, as, for example, in illustrations from the much-copied Octateuch manuscripts (fig. 4).Footnote 64 Thus suspended, the brazen serpent withdraws from touch and heals through optical contact alone. In contrast, the Serpent Column was touchable.Footnote 65 The brazen serpent represents a single snake; the Serpent Column, three. Moreover, while the brazen serpent was biblically sanctioned, the same cannot be said for the Serpent Column. It is hard to know how significant these differences would have been to contemporaries. Other than the brazen serpent, the Serpent Column may have also recalled images from a variety of medical, pre-Christian, and occult contexts, such as the healing serpents of Asclepius or Hygeia, the protective serpents of ancient Roman lararia, as well as the entwined serpents on the caduceus, the wand carried by Hermes, and with it, broader hermetic associations.Footnote 66

Fig. 4. Smyrna, Library of the Evangelical School, A.1, 12th c., folio 168 verso, now destroyed. Moses raises the Brazen Serpent. Credit: D.C. Hesseling, Miniatures de l'Octateuque grec de Smyrne (Leiden: A.W. Sijthoff, 1909), 72, pl. 238.

Despite their differences, the implicit rationale underlying the curative power of both the Serpent Column and the brazen serpent is essentially the same: the idea that like cures like, an extension of the principle of sympathy through mimesis.Footnote 67 Both objects allow snakebite victims to encounter an image and copy of the cause of their affliction. However, this second encounter is attenuated: It is with a copy and not the original, and it occurs through touch and vision and not through a second snakebite. Under these new conditions, the attraction between similar things enables reversal and opposition.Footnote 68 An image and copy imprinted in the victim counteract the prototype's venomous bite. Although vision and touch are different ways to effect a cure, they accomplish essentially the same objective: a second, and attenuated, contact. In the prevailing Aristotelian theory of perception, both vision and touch involve the impressing of a percept's form upon the percipient through a medium, that is to say, air in the case of vision, flesh for touch.Footnote 69 Analogous to the operation of sympathy, both forms of perception involve contact and copy. Both cures double the prototype as a copy in turning it against itself.

As this comparison to the brazen serpent suggests, the Serpent Column's perceptibility—its appearance and materiality—probably played a role in how contemporaries understood its talismanic action. At the basic level of visibility, the ruination of the Column's surroundings would have assisted contemporaries first in noticing it, and then in recognizing it as a talisman.Footnote 70 Without water, and in the midst of a ruin, the Serpent Column may have looked more like a talisman than it had previously. If, when water flowed through the fountain, the Serpent Column had once recalled water serpents, then without that water it may have now resembled an intertwining of vipers—monumental testimony to the old belief that water snakes transform into vipers when their ponds dry up.Footnote 71 With the fountain dry and the central barrier despoiled, viewers also had greater direct access to the monument. Some of the ancient inscriptions covering the Column's lower coils may have then been more visible.Footnote 72 If these inscriptions were at all discernable, even if illegible, they may have made the Column appear as though it had been enchanted as a talisman in the past. As noted earlier, the Byzantine word for talismans, stoicheia, also refers to letters of the alphabet.Footnote 73 Ancient inscriptions, however mundane, were often accorded special or talismanic properties in the medieval Mediterranean.Footnote 74 At the same time, metalworking itself had deep associations with magic and the occult going back to the ancient world.Footnote 75 The bronze material of the monument and the scale of the casting may have readily recalled such associations.

Contemporaries may have also seen the Column's intertwining serpents as a means of controlling actual serpents or counteracting their venom. For example, a twelfth-century so-called poison cup from Syria (fig. 5) shows two confronted, knotted serpents. An inscription on the outside of the bowl specifies, ‘this blessed cup is useful against the sting of a serpent’, among many other things.Footnote 76 A similar image, with only one instead of two knotted serpents, appears on a Byzantine plate from Cherson in Crimea (fig. 6). Although lacking an inscription, it may have had a similar role in counteracting poisons.Footnote 77 The knotting of the serpents’ bodies on both vessels seems to suggest containment and self-defeat, which apparently make each vessel a type of antidote or guarantee against poisoning. Knotting and binding were a regular part of everyday magical practices.Footnote 78 Byzantine people for this reason may have ascribed apotropaic powers to knotted, Solomonic, and spirally fluted columns.Footnote 79 The fact that Clavijo explicitly likened the Column's form to a rope with three intertwined elements may hint at such a reading for the Serpent Column.Footnote 80

Fig. 5. Private Collection, fine Damascus poison cup, brass, Syrian School, 12th c., diameter: 11.1 cm. Credit: Private Collection; Photo © Christie's Images / Bridgeman Images.

Fig. 6. Red clay bowl with knotted dragon motif from Byzantine Cherson, 13th c, diameter: 18.9 cm. Credit: I.S. Chichurov, Byzantine Cherson (Moscow: Nauka, 1991), no. 250.

The Column's intertwining serpents might have also suggested viperid reproduction. Depictions of intertwined coupling vipers, such as in the late ninth- or early tenth-century Morgan Dioscorides (fig. 7), offer formal parallels for the Serpent Column.Footnote 81 In his Theriaka, Nicander describes how when vipers copulate, the female decapitates the male. The offspring eventually chew their way out of their mother.Footnote 82 Nicander adds that a viper-repellent salve could be concocted from the ashes of vipers that had been caught coupling at crossroads.Footnote 83 The intertwined serpents of the Serpent Column may have suggested anti-viper properties, by alluding to their dramatic reproductive destiny, or to the material basis of a salve purported to keep them at bay.

Fig. 7. New York, Morgan Library, MS M 652, folio 343 recto. Male and female vipers copulate in an illustration accompanying a paraphrase of Nicander's Theriaka. Credit: © Morgan Library, New York.

Whatever the monument's form suggested to viewers, the claim that venom filled its cavities meant that its efficacy was not only a result of what it seemed to portray, but also what was purported to be inside it. The venom inside the monument recalls the ancient practice of placing pharmaka, powerful substances, inside statues usually so as to cast spells or to animate them.Footnote 84 Nevertheless, this venom also exemplifies the Column's talismanic nature. According to Galen, just as a magnet spreads through iron and transforms its qualities with the force of its own special qualities, so too do poisons alter the nature of the human body by changing its humours.Footnote 85 The special properties and sympathetic qualities of talismans were similarly said to result from changes to its nature.Footnote 86

Through the attraction and opposition of similar things under the principle of sympathy, the venom inside the Column was supposed to counteract the venom in the snakebite victim's body. However, by touching the Column, the beneficiary does not make direct contact with the venom inside it; instead, the Column and the venom together enable the cure. The fact that the cure requires both Column and venom suggests that it works like a compound drug made of multiple components. The bronze alloy of the statue is an admixture of different metals and other materials, which were together understood to contribute to a unique final product.Footnote 87 On a more basic level, the ancient word for the Column's patina was identical to a word for poison, ios (ἰός).Footnote 88 Although the Column's envenomed bronze cavities, its dark, patinated surfaces, the noxious form of three intertwined serpents, and the barely legible ancient inscriptions covering their coils might be individually dangerous, the talisman had been compounded in the right way, with the right words, at the right time, by the right ritual expert.

In comparison to the earlier talismans set up by Apollonius of Tyana, the Serpent Column appears to be notably more medicalised, which could hint at shifts in how talismans were conceived of in the Late Byzantine period. This medical quality is still, however, effectively an extension of the Byzantine talisman's broadly ecological nature. As venom upset the regular balance of the body's humours, the Serpent Column healed by intervening within a local system, the beneficiary's body, either by drawing out the venom, or by counteracting it and restoring balance through sympathy.Footnote 89 The specificity of place in the action of the Serpent Column, either in keeping snakes out of the city or by protecting only those within it, likewise speaks to its particular place within a local ecology.

Conclusion

This study examines how contemporaries may have understood the Serpent Column as a talisman. The Serpent Column first appears in the textual record as a talisman in the 1390s. While it may have been regarded as a talisman prior, the Fourth Crusade and centuries of hardship probably gave the Serpent Column a more prominent position in the urban landscape than it had previously. Exactly when—and over what period of time—the Serpent Column became a talisman remains unknown. Nevertheless, as contemporaries began to attribute talismanic properties to the monument, they imagined it within a wider system of interactions between various non-human operators—snakes, demons, potent substances, as well as astral and elemental forces. The Serpent Column was bound to this network sympathetically and antipathetically by way of the venom inside it, as well as the monument's shape and the inscriptions on it. Looking at the hollow bronze coil with its three terrible heads, contemporaries might imagine snakes fleeing from it, the venom said to be inside it, a victim of snakebite miraculously healed, Moses and the brazen serpent, Leo the Wise performing arcane rituals with efficacious words calling upon demons, planets, and stars. In doing so, the medieval beholder envisions a world where the talisman actively mediates between the human and non-human.