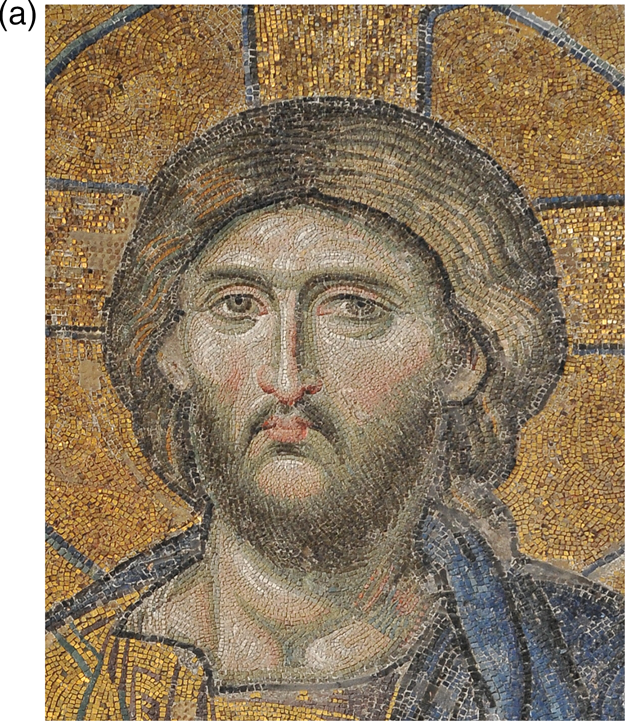

After the recapture of Constantinople in 1261 artistic production in Byzantium experienced a recovery. This recovery was expressed in the remarkable production of a large number of monumental and non-monumental works created during the turbulent reign of Michael VIII Palaiologos (1259–82) and particularly the reign of his son Andronikos (1282–1328).Footnote 1 In the capital of Byzantium itself the beginning of this splendid period is marked – according to the prevailing view – by the mosaic panel of the Deesis in the Hagia Sophia (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The Deesis panel, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople. Ekkehard Ritter, Byzantine Institute and Dumbarton Oaks fieldwork records and papers, Dumbarton Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.

The depiction of the Deesis (Trimorphos) survives in a fragmentary state in the gallery of the church and in the south section of the gallery, a space reserved for the emperor and his family, courtiers, servants and guards. It is an over-life-sized depiction (width: 6.03 m) that covers all of the available surface, from the floor to the springing of the vaults. The figure of Christ Pantokrator has been placed, as was the usual practice, in the middle of the composition. It is rendered frontally, with a cross-halo. Christ raises his right hand in a gesture of blessing, while in his left he holds a bejewelled Gospel book. Remains of tesserae beneath and to the right of Christ indicate that he was originally seated on a throne. Christ is flanked by the figures of the Virgin Mary and St John the Baptist, with their hands raised in supplication. The gold ground of the depiction is formed by successive rows of trefoil motifs.

Due to its unique style of execution and the lack of epigraphic data, the Deesis mosaic has given rise to a variety of different datings. For example, Thomas Whittemore (1871–1950) – the scholar who succeeded in convincing the Turkish government in 1931 to remove, under his supervision, the plaster covering the Byzantine mosaics in the Hagia Sophia – was the first to draw a stylistic connection between the suppliant figure of the Virgin and the figure of the Virgin in the Vladimir icon, dating the mosaic to the last years of the eleventh or to the first half of the twelfth century.Footnote 2 André Grabar believes that the work was created in the late twelfth century,Footnote 3 while Otto Demus, in his study on the art of the Kariye Djami (1975), dates the work to the end of the reign of Michael VIII Palaiologos.Footnote 4 Recently, the present author has dated the mosaic as late as the first decade of the fourteenth century.Footnote 5

Notwithstanding these divergences, most researchers now accept that the mosaic was constructed in 1261, between 25 July and December of that year at the latest, as part of the general renovation of the church that was carried out in view of the anticipated coronation of the emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos. As is well known, the coronation probably took place at the end of August or in September 1261 and, in any event, before Christmas that year.Footnote 6 It is also well known that Michael Palaiologos entered Constantinople on 15 August 1261, three weeks after its recapture. The feast-day of the Dormition was chosen as the day for Michael to make his ceremonial entry into the city so that he could show his reverence for its guardian, the Virgin. Deno John Geanakoplos and Ruth Macrides follow Akropolites in holding that ‘the entire day's programme was intended as a thanksgiving to God rather than a celebration of an imperial triumph’.Footnote 7

The view that the Deesis mosaic was created in 1261 was established by Robin Cormack, who also contended that the mosaic was accompanied by a suppliant figure of the emperor Michael VIII which no longer survives and that, stylistically, the work probably draws on Italian art of the period,Footnote 8 a view which concurs with that of Demus. However, other researchers, such as Alice-Mary TalbotFootnote 9 and, with reservations, Cecily Hilsdale,Footnote 10 have shown that there is insufficient evidence to support the construction of the Deesis mosaic at this particular date. Let us examine the historical and artistic facts.

1. The facts

Although he emphasizes the piety of Michael VIII Palaiologos, George Akropolites does not mention any artistic interventions in the church of Hagia Sophia either before or after the emperor's entry into Constantinople.Footnote 11 Neither does Nikephoros Gregoras make any such mention: he notes the various repairs carried out in Constantinople and the city's embellishment immediately after its recapture, he makes no reference to Hagia Sophia.Footnote 12 It is true, of course, that George Pachymeres claims that Michael went on to see to the renovation, under the supervision of the monk Rouchas, those parts of the church that had been altered by the Latin conquerors, and that he furnished the sanctuary with sacred vessels and vestments:

Kαὶ τὸ μὲν ἱερὸν ἅπαν μετεποίει πρὸς τὴν προτέραν κατάστασιν, ἐκτραπὲν ἐπὶ πολλοῖς παρὰ τῶν Ἰταλῶν. Καὶ δὴ ἐπιστήσας τὸν μοναχὸν Ῥουχᾶν, ἄνδρα δραστήριον ἐπὶ τοῖς τοιούτοις, τό τε Βῆμα καὶ ἄμβωνας καὶ σωλέαν καὶ ἄλλ’ ἄττα βασιλικαῖς ἐξόδοις ἀνῳκοδόμει. Εἶτα πέπλοις καὶ σκεύεσιν ἱεροῖς τὸ θεῖον τέμενος καθίστα πρὸς τὸ εὐπρεπέστερον. Εἶτα καὶ χώρας προσετίθει τῇ ἐκκλησίᾳ …

And as for the temple [of Hagia Sophia], he restored it in its entirety to its previous state, since it had been modified in many ways by the Italians. Having appointed as responsible the monk Rouchas, very capable in such matters, [the emperor] renovated at his own expense the Bema, the ambo, the solea and other parts of the church. He also decorated this divine temple with veils and holy vessels. After that, he endowed the church with estates …Footnote 13

However, Pachymeres makes no mention of the Deesis mosaic. I believe that, had the mosaic been constructed especially for the coronation of Michael VIII, it would have been difficult for him and his successors not to mention it, unless we accept that the phrase καὶ ἄλλ’ ἄττα βασιλικαῖς ἐξόδοις ἀνῳκοδόμει also refers to works of a pictorial character despite the verb ἀνῳκοδόμει.

Furthermore, Michael VIII's chrysobull on behalf of Hagia Sophia, possibly issued in 1272, states that the emperor μὴ ἐν μόνοις ἀναθήμασιν σκευῶν ἱερῶν καὶ ἁγίων ἐπίπλων τὸν καινισμὸν ἐπισπεῦσαι, καὶ τὴν ἀνανέωσιν ἀπεργάσασθαι, ἀλλὰ γὰρ δὴ καὶ ἐπὶ τοῖς αὐτουργίοις, καὶ ἐπὶ τοῖς κτήμασιν, ἐξ ὧν ἐτήσιοι πρόσοδοι τοῖς τοῦ Θεοῦ ἐπιγίνονται λειτουργοῖςFootnote 14 (carried out the decoration and completed the renovation of the church, not only with donations of holy vessels and furniture, but [he] also endowed it with land/estate, from which the ministers of God receive income annually). Yet even here there is no mention of the construction of a mosaic in Michael's honour. Nor does Manuel Holobolos refer to this work of art in his Encomium to the same emperor (1267), even though he provides information about Michael's renovation of the Hagia Sophia.Footnote 15 Even Gregory II the Cypriot, Patriarch of Constantinople (c.1241–c.1290), in his Encomium to the same emperor (1273?),Footnote 16 while listing a series of works and donations made by Michael after the recapture of the City, does not mention the renovation of Hagia Sophia, let alone the mosaic decoration within it:

Τῆς δέ σου περὶ τὸ θεραπεύειν τὸ θεῖον θερμότητος πολλὰ μέντοι καὶ ἄλλα τεκμήρια⋅ θείων ναῶν ἁπανταχοῦ τῆς Ῥωμαίων ἀνοικοδομαί, ξένων καταγωγαί, νοσούντων ἐπιμέλειαι … οὐχ ἧττον δὲ δή που καὶ τῶν φροντιστηρίων καὶ ἀσκητηρίων, ὅσα γε δὴ καὶ κατὰ πόλεις καὶ ἐν ἐρημίαις ἀνήγειρας …

The marks of your zeal in the service of God are many and varied: the rebuilding of holy temples in every corner of the Roman empire, guesthouses, hospitals … and, not least, the places of [spiritual] study and hermitages erected by you in cities and deserts alike …Footnote 17

From the foregoing it is clear that Michael VIII Palaiologos laboured for the reconstruction and embellishment of his capital, and of course for the alterations that needed to be carried out in Hagia Sophia. There is no evidence, however, that Michael played any part in the construction of the Deesis mosaic in the gallery. It may be reasonably assumed that the lack of evidence in the sources regarding art works in Hagia Sophia is due to the fact that Michael had other priorities in the spheres of the economy, defence, diplomacy and demography, amongst others. In any event, the lack of information about the mosaic, particularly in texts eulogizing the emperor's work, weakens – if it does not eliminate altogether – the case for the dating of the mosaic to 1261. There is, too, other evidence that casts doubt both on this dating and also on the construction of the mosaic as part of the renovation work on the church in preparation for the coronation of Michael Palaiologos. More particularly, Cormack's view that the mosaic panel of the Deesis was constructed with the financial assistance of the said emperor as part of the aforementioned renovation work is open to question.

First and foremost, the siting of the Deesis mosaic in the south tribune of Hagia Sophia and its eastward orientation indicate that this particular work is not connected with some kind of political or institutional event. This is for the simple reason that the mosaic cannot be seen either from the nave or from the gallery itself. In order to see it, one must enter the central part of the south gallery, turn to the south and then to the west. Consequently, the siting of the mosaic in this inconspicuous position, in an area reserved for the use of the imperial family and its courtiers and not the general public, does not suggest a connection with a political or ecclesiastical event of a public nature like an imperial coronation.

Moreover, Talbot has pointed out that the construction of such a mosaic in the period between Michael's entry into Constantinople on 15 August 1261 and his coronation the following autumn seems unlikely.Footnote 18 Indeed, even if we accept that immediately after his entry into Constantinople, not having any other priorities, Michael hastened to commission the work in question, the mosaic's large dimensions, together with the use of tiny tesserae in the faces and the complex structure of the gold ground, indicate that considerable time would have been required to construct it, not least for the production of the tesserae, particularly the gold ones. It should be noted that, the quality and the form of the tesserae in the Deesis mosaic are unique.Footnote 19 This fact suggests that the artists working on the mosaic very likely produced the tesserae themselves, having no other option.

Apart from this, the dating to 1261 of a work of such high technical skill and plastic quality cannot be easily justified if one considers the fact that mosaic art at this time was in decline. It should be recalled that the last monumental mosaic ensemble to be constructed before 1261, at least in mainland Greece, belongs to the late eleventh or early twelfth century: the Daphni Monastery outside Athens. So where and how did the illustrious artists who executed the Deesis mosaic gain their experience? In Latin Constantinople or in Laskarid Nicaea, where not a single monumental ensemble, let alone a mosaic one, survives?

At this point one could claim that, according to the celebrated Ekphrasis of Nikolaos Mesarites (1198–1203), the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople was redecorated with mosaics in about the year 1200.Footnote 20 This view was supported by Ernst Kitzinger and Henry Maguire.Footnote 21 However, it cannot be accepted without question as it is not substantiated by any other source.Footnote 22 It should be noted, however, that the absence of mosaic ensembles in the period between 1100 and 1260 could be due to a variety of different reasons, such as natural disasters, and the creator of the Deesis mosaic in Hagia Sophia may indeed have had a model which no longer survives. Nevertheless, three things should be taken into consideration here: a) in the pioneering royal commissions of the thirteenth century, the wall-paintings in the katholika of the Mileševa Monastery (1220–34) and the Sopočani Monastery (1268–76), the artists allude to the mosaic art by painting imitations of tesserae on gold ground; b) the first extant mosaic ensemble we have from the thirteenth century, the Church of the Paregoritissa at Arta, dates from the end of that century and, more importantly, displays evidence of difficulty in the treatment of form with tesserae and, by extension, a lack of experience in mosaic techniques,Footnote 23 and c) the next period after the Middle Byzantine era that is impressive for its large-scale and high quality mosaic ensembles is the first quarter of the fourteenth century.

Mosaic art had experienced a long period of decline and the situation gradually began to change from the late thirteenth century onwards, during the reign of Andronikos II Palaiologos. Consequently, neither the appearance of the Deesis mosaic in the mid-thirteenth century, nor its dating to that time, can be justified, at least on the basis of the data we currently have at our disposal.

2. The art of the Deesis mosaic in the context of Late Byzantine painting

The mature and sophisticated artistic idiom of the Deesis mosaic appears to be an isolated case in the context of painting trends in the period around 1260, since no monumental ensemble of similar quality survives from the same era. At this point it should be mentioned that Byzantine art during the Latin (1204–61) and the early Palaiologan period is marked by a coexistence of various artistic tendencies and a certain reluctance to develop and consolidate a new style of painting, distinctively different from the Komnenian.Footnote 24 At the same time, this insistence on the Komnenian pictorial tradition is fully manifested in the artistic production of the Latin East.Footnote 25 It is for these reasons that no crusader painting or mosaic can be considered as a precursor or contemporary of the Deesis mosaic. For if one assumes that the dating to 1261 is correct, the monuments that could be compared with the Hagia Sophia mosaic are located outside the Byzantine dominions and consist in the following: the wall-paintings in the katholikon of the Mileševa Monastery (1220–34) and those in the Church of SS Nicholas and Panteleimon in Bojana in Bulgaria (1259).Footnote 26

Maria Panayotidi notes that ‘the Bojana frescoes present a great similarity with the Deisis mosaic panel at Ayia Sophia in Constantinople, of 1261. It was most probably the work of mosaicists from Nicaea, where the imperial court was transferred, during the period of exile, and where qualified masters and mosaic workshops must have flourished’.Footnote 27 However, the wall-paintings in the katholikon of the Church of Saints Nicholas and Panteleimon at Bojana have deteriorated considerably at many points. Therefore, the similarity between the Bojana wall-paintings and the mosaic in Constantinople is probably coincidental. Furthermore, the art at Bojana clearly draws on the great tradition of Komnenian art which was strong in the thirteenth century, a fact that can be clearly seen in the draftsmanship and the anatomical details – something which does not apply in the case of the Deesis mosaic.

Maria Panayotidi's attribution of the Deesis mosaic to a Nicaean workshop is worth brief comment here, not least because similar views have been expressed by almost all Greek researchers. Indeed, recently Konstantia Kefala, in her study on thirteenth-century wall-paintings in the churches of Rhodes, links a number of that island's monuments with Nicaea.Footnote 28 It is certain that the political, ecclesiastical and cultural influence of the Nicaean state extended far beyond its physical boundaries. It is also certain that Nicaea soon claimed to be the exiled seat of the legitimate Byzantine government as it became the base of the Patriarch and home of most of the Byzantine aristocracy. The Orthodox residents of the Latin Empire of Constantinople (Imperium Constantinopolitanum) and the monks of Mount Athos regarded Theodore I Laskaris, the ‘New Zorobabel’ and ‘New Moses’, as the true and legitimate claimant to the Byzantine throne.Footnote 29 Nevertheless, the arguments put forward by the researchers, such as the above mentioned and also Vojislav Djurić, Panagiotis Vokotopoulos and Manolis Borboudakis,Footnote 30 conflict with the following facts: firstly, the lack of any reference to an art work in the sources; secondly, the lack of monuments in Nicaea itself; and finally, the fact that the artistic ensembles that researchers associate with the Laskarid state are conservative in character and display a variety of different idioms.

In my view, these facts do not support the existence of a large artistic centre in Laskarid Nicaea. The complete absence of surviving architectural and artistic works in the Nicaean state may be due to fortuitous reasons. Yet again, this is strange if we consider the fact that the two other regional Byzantine states – that of Trebizond under the Great Komnenoi (to a lesser extent) and that of Epirus under the Komnenos Doukas dynasty (to a greater extent) – boast a notable and uninterrupted artistic output.Footnote 31 Whatever the case, the connection between the Deesis mosaic and a supposed ‘art of Nicaea’ is an arbitrary one not only because we have no information to support this and the mosaic has no ‘artistic parallel’ in western Anatolia, but also because the artistic idiom of the mosaic bears no relation to the generally conservative wall-paintings and miniatures that researchers associate with Nicaea.

In my opinion, the only monumental work that can, with relative confidence, be connected with the Deesis mosaic, if the latter is assumed to have been constructed in 1261, is the pioneering wall-paintings in the Mileševa Monastery (1220–34).Footnote 32 However, the artistic idiom of the artist who created the Deesis mosaic certainly does seem to draw heavily on that of the painter of the Mileševa Monastery. The large eyes of the figures in the Serbian decoration and the crude rendering of the muscles of the faces and the drapery folds are not to be found in the Deesis mosaic. The refinement and academicism in the treatment of form and the lack of overt references to Komnenian art suggest a later dating for the Deesis mosaic. In my estimation, the work clearly expresses another artistic milieu: that of the early fourteenth century.

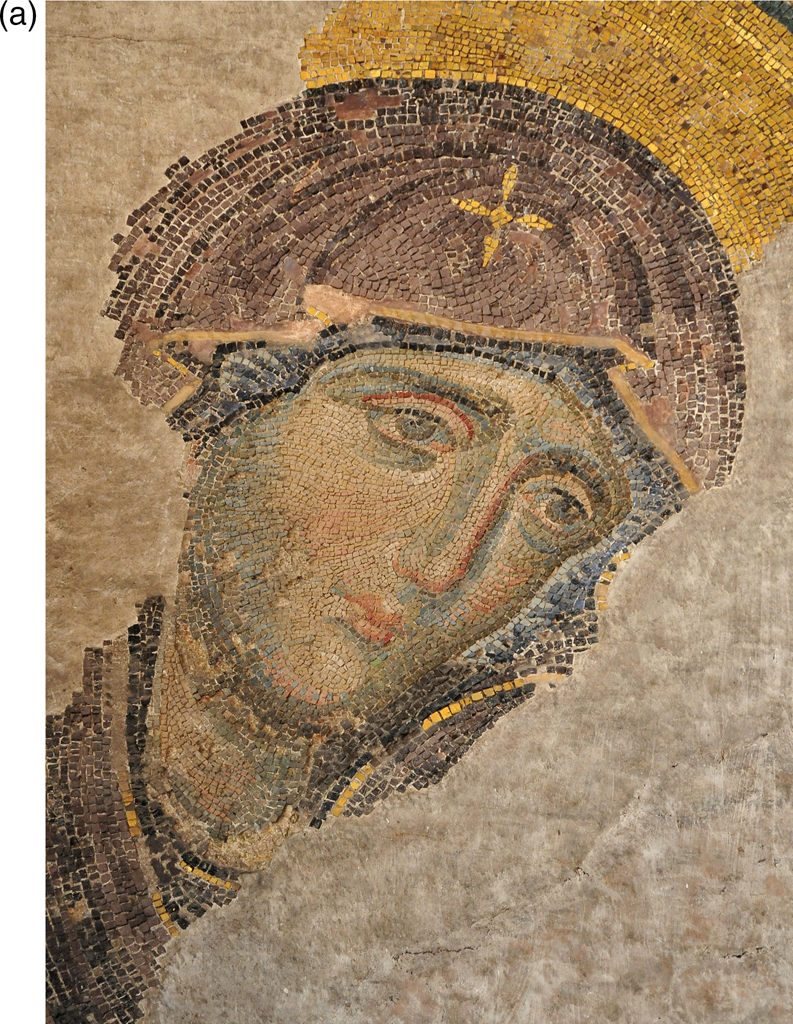

In particular, if the figure of Christ in the Deesis mosaic is compared with the corresponding figure on the south-east pier of the Protaton at Karyes on Mount Athos (Figs 2a–b) or the figure of the Virgin with that on the north-east pier of the same church (Figs 3a–b), it is clear that the artistic idiom of the Deesis panel is closely connected with that of the painter of the Athonite church. The draftsmanship, with the specific typology of anatomical volumes and a certain underlying clumsiness in their articulation, the low tonality in the garments, and the refinement in the treatment of the drapery folds attest to some connection between the mosaic and the Protaton wall-paintings, recently been dated to the years 1309 and 1311, just before the decoration of the katholikon of the Vatopediou monastery (1311), on the basis of historical, epigraphic and stylistic evidence.Footnote 33 The modelling of the face of Christ in the Hagia Sophia mosaic is refined and elegant, with slight tonal differences between the base colour and the shading and between the flesh and its illuminated sections, and its particular arrangement of the linear lights, just as in the face of the Christ in the Protaton.

Fig. 2a. The Deesis panel, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople. Detail after K. M. Vapheiades, Late Byzantine Painting: Form and pictorial space in the art of Constantinople, 1150-1450, Athens 2015, fig. 162a.

Fig. 2b. Christ enthroned, Protaton Church, Mount Athos. Detail after Manouil Panselinos, Εκ του ιερού ναού του Πρωτάτου, Thessaloniki 2003, no. 94.

Fig. 3a. The Deesis panel, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople. Detail after K. M. Vapheiades, Late Byzantine Painting: Form and pictorial space in the art of Constantinople, 1150-1450, Athens 2015, fig. 161.

Fig. 3b. The Virgin enthroned and Child, Protaton Church, Mount Athos. Detail after, Manouil Panselinos, Εκ του ιερού ναού του Πρωτάτου, Thessaloniki 2003, no. 93.

It should also be noted that the mannerism and sophistication of form that is abundantly clear in the Hagia Sophia mosaic also suggests early fourteenth-century works, such as the mosaics in the church of the Holy Apostles in Thessaloniki and those in the Chora Monastery.Footnote 34 After comparing the figure of Christ in the Hagia Sophia mosaic (Fig. 2a) with that on the south-east pier of the Protaton (Fig. 2b) and that in the church of the Chora Monastery, which bears the epithet ἡ Χώρα τῶν Ζώντων (Fig. 4), I have come to the following conclusions: the figure in the Hagia Sophia mosaic has more harmonious proportions than that in the Protaton (ratio of head height to shoulder width). However, to a certain extent, it lacks the movement suggested in the Chora figure, with its lowered right shoulder and the off-centre position of the pit of the neck. The head of the Christ in the Protaton is almost circular in outline, while that in the Hagia Sophia mosaic is almost oval. In the figure in the Hagia Sophia mosaic the low tonality in the garments and the fluid plasticity of the drapery folds, although they are characteristic of the art of mid- and late thirteenth-century icons and miniatures, are rare in the monumental painting of the same period. The linear rendering of the anatomical features which marks many of the Protaton painter's figures is less pronounced in the Hagia Sophia mosaic, though this is even more true of Metochites’ church. The modelling of Christ's face in the Hagia Sophia mosaic, like that of the face of the Virgin, is organic and refined. The absence of fragmentation of form is clear to see, as are the slight tonal differences between the base colour and the shading and between the flesh and its illuminated sections, a feature that lends naturalness to the faces. This is an effect achieved by the craftsman who decorated the Chora Monastery and (to a lesser extent) by the Protaton painter. However, the most important thing is that the shading on the head of Christ in the Hagia Sophia mosaic appears to acquire substance since the shading on the neck and in the areas beneath the eyes takes the form of cast shadows, a feature which also occurs in the head of Christ in the Chora Monastery but not in that at the Protaton.

Fig. 4. Christ Chalkitēs, Monastery of the Chora, Constantinople. Detail. Carroll Wales, Byzantine Institute and Dumbarton Oaks fieldwork records and papers, Dumbarton Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.

I believe that the foregoing analysis is sufficient to show that the mosaic panel in the south gallery of Hagia Sophia should be dated as late as the beginning of the second decade of the fourteenth century, the same date as the mosaics of the funerary chapel in the Pammakaristos Monastery (after 1303/4, 1310–15), which are quite similar from a stylistic point of view to that of the Deesis panel. It is also worth noting that the mosaics of the eastern arch of the Hagia Sophia (also a Deesis) are dated to the middle of the fourteenth century,Footnote 35 such as those of the eastern apse, according to George Galavaris and Massimo Bernabò.Footnote 36 This fact indicates that more than one artistic work came into being in the Hagia Sophia during the first half of the fourteenth century. Consequently the Deesis mosaic should be perceived in the context of the fourteenth-century Palaiologan decorations in the mentioned church. However if the dating of the mosaic in the second decade of the fourteenth century is correct, who commissioned the work and for what reason?

3. The patron and the reasons for the creation of the Deesis mosaic

There is not a single mention of the Deesis mosaic in the sources. In spite of this, it is possible to place under critical scrutiny a number of hypotheses based on the facts we currently have at our disposal.

The Deesis mosaic is situated in the south gallery of Hagia Sophia, which was reserved for the emperor and his entourage. The mosaic was constructed in an area of the church devoted to private rather than public worship, despite its large size and the fact that ecclesiastical synods and meetings were once held here.Footnote 37 If we accept the date proposed, it is clear that the mosaic must have been commissioned either by the emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos or a member of his close circle. It should be recalled that Nikephoros Gregoras emphasises Andronikos’ concern for the churches of Constantinople and Hagia Sophia, as well as his unselfish intentions:

Ὁ δὲ βασιλεὺς Ἀνδρόνικος οὗτος πολλῷ βέλτιον κρίνας τοὺς προϋπάρξαντας βελτιοῦν τε καὶ συνιστᾷν κατὰ τὸ εἰκὸς καὶ τοὺς ἐπιόντας ἐκ τοῦ χρόνου κινδύνους μετὰ τῆς προσηκούσης βοηθείας τε καὶ σπουδῆς ἀποκρούεσθαι, ἣ τοὺς μὲν ἀφιέναι πίπτειν, φιλοτιμεῖσθαι δ’ ἐκ βάθρων ἐγείρειν ἑτέρους, ἐν τούτῳ τὴν πᾶσαν ἐκείνου σπουδὴν καὶ φιλοτιμίαν … καὶ ἵνα τὰ ἐν Ἀσίᾳ καὶ Εὐρώπῃ πολίχνια παραδραμὼν … τῶν ἐκ Κωνσταντινουπόλει μνησθῶμεν ἔργων … καὶ τελευταῖον ὁ μέγιστος οὗτος καὶ περιβόητος τῆς τοῦ Θεοῦ Σοφίας νεώς⋅ ὅν δὴ καὶ ἔτι πλέον περιποιήσασθαι ἤθελε μέν, ἀνέκοψε δ’ αὐτοῦ τὰ τοιαῦτα σκέμματα ὁ καθάπερ λαῖλαψ αἰφνίδιος ἐπελθὼν τῆς βασιλείας μερισμός τε καὶ σύγχυσις.

The Emperor Andronikos, considering that much better to improve and rebuild existing churches as appropriate, and to repel the dangers that the passage of time brings with proper aid and care, than to let some collapse, and to seek honour by building others from the foundations, showed all his care and zeal in this … Leaving aside the smaller cities of Europe and Asia … let us mention all the projects that took place in Constantinople … and lastly the greatest and most illustrious Church of the Holy Wisdom of God; this he wished to secure and care for even more, but he was hindered in such enterprises by the division and the turmoil of the empire that erupted like a sudden storm.Footnote 38

Given Andronikos’ interest and concern for the Hagia Sophia (as exemplified by his reinforcement of the church with buttresses in 1317), as well as his upgraded institutional role in the Church and piety, which can be clearly seen in a series of contemporary texts and events of his reign, we are obliged to accept that the most likely patron of the Deesis mosaic was Andronikos II Palaiologos. This proposal is reinforced by two further facts.

The representation of the Deesis, as an iconographical epitome of the Second Coming, clearly has an eschatological character. This iconographical theme has a long history in the art of Byzantium, conveying the role of the Virgin (and John the Baptist) as an intercessor on behalf of the salvation of mankind at the Last Judgement.Footnote 39 The eschatological and soteriological character of the theme is emphasized by the very scale of the sacred figures, much larger than life size. And this cannot be accidental. In my opinion, this is a reflection of the faith of the mosaic's patron, of his sense of insignificance before the Righteous Judge and God of Mercy. It also indicates the intensity of the desire for Christ's intercession marked by this votive offering. It is obvious that in commissioning such a large eschatological representation in his own sacred space, the patron did so in order to seek and invoke God's mercy and help. But for what reason? What exactly does this imperial donation refer to? To what need does it attest?

If we look at the events that took place in the period around and after the year 1300, during which the Deesis mosaic appears to have been created, it is clear that Byzantium was in the throes of a political, economic and religious crisis. Indeed, the period would be crowned by the end of the Catalan raids,Footnote 40 the termination of the Arsenite schism (1310)Footnote 41 and the end of pillaging by Turkish mercenaries, with the aid of the pious protostrator Philes Palaiologos (1314).Footnote 42 It is likely, then, that the representation of the Deesis in the section of Hagia Sophia's south gallery reserved for the imperial family expresses Andronikos Palaiologos’ entreaties to Christ the Saviour, as well as his faith in the intercession of the Virgin Mary, the guardian of Constantinople, for the salvation of the Empire from its internal and external foes, and particularly the Turks.

Τhe ‘private’ character of the mosaic in question is supported by the fact that the representation of the Deesis is located in the south part of the Bema of the Byzantine churches (single-door ‘diakonikons’): this space is reserved to eminent ktetors or wealthy patrons, usually members of the imperial family.Footnote 43 This indeed reinforces the hypothesis that the Deesis mosaic decorated a private oratory for the emperor and his family. But what were exactly the purpose and the meaning invested in this oratory?

The eschatological symbolisms conveyed by the mentioned iconographic theme fits the rituals performed in the narthex and the side chapels, where arcosolia and tombs are usually to be found. The Deesis was a favoured subject for funerary sites and monuments, such as the tomb area beneath the chapel of St John the Baptist in the Iveron Monastery on Athos (980–1005),Footnote 44 the Ossuary in Baškovo Monastery (twelfth century),Footnote 45 the church of St Nicholas in Varoš near Skopje (1298),Footnote 46 the chapel of the Monastery of Pammakaristos, Constantinople (1310–15),Footnote 47 the north-west chapel of the katholikon of the Virgin Hodegetria at Mistra, Laconia (1322/3),Footnote 48 and the narthex of the katholikon of the Monastery of Christ Pantokrator, Mount Athos (1363), whose original form and purpose was funerary, with the Deesis over the grave of the ktetors.Footnote 49

Given its subject's funerary associations, it is worth asking if the Deesis mosaic in the tribune of the Hagia Sophia had a similar function. This link could be discussed in light of the archaeological evidence indicating burials in the same space.Footnote 50 However, such evidence is so thin and datable to the Latin period of Constantinople, which perhaps points more towards the Western tradition of burying in the aisles. No Byzantine writer speaks of funerary monuments inside Hagia Sophia during the reign of Andronikos II. Besides, it is well known that the chapel of St John the Baptist attached to the katholikon of the Monastery of Constantine Lips was the favourite burial place of the Palaiologan imperial family.Footnote 51 Nevertheless, such a possibility cannot be excluded, since the galleries of the Byzantine churches had multiple uses, which remain unclear.Footnote 52

On the other hand, it is very attractive to assume that the space decorated by the Deesis mosaic was a replacement for the palatine chapel of the Virgin of Pharos totally destroyed during the Latin period. It is known that the most precious relics of Christendom, such as those of Christ's Passion, were housed in this church until the reign of the Latin emperor Baldwin II. Because of this Nikolaos Mesarites described the church of Pharos as an image-substitute of the Holy Sepulchre.Footnote 53 Given the absence of a hallowed palatine chapel after 1261 and given that the space in front of the Deesis mosaic reserved for the emperor was sanctified as a substantial part of Hagia Sophia church, this hypothesis could be valid, no matter how difficult to prove. So regardless of the above reasonable assumptions, there can be few doubts it constituted a sacred locus, invoking God's mercy and eternal life.

The woeful events mentioned above came to a conclusion in the first few years of the second decade of the fourteenth century, during the patriarchate of Nephon I (1310–14), the patron of the mosaic decoration in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Thessaloniki.Footnote 54 Considering the fact that the mosaic ensemble in the Church of the Holy Apostles was created by an artist whose style is similar to that of the painters who decorated the Protaton (1309–11), it is likely that Patriarch Nephon, who was from Beroea, played a part in the creation of the Deesis mosaic by recommending the artist who had received a similar artistic training to the painters of Thessaloniki, and particularly those of the Protaton Church.

Concluding remarks

Medieval monuments are often treated by art historical scholarship as timeless, unaffected by today’s cultural agenda. However, contemporary perceptions of heritage, and attention to the layers of a monument’s history can make an essay on a medieval mosaic quite timely. It has been argued here that the mosaic panel of the Deesis in the south gallery of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople most likely constitutes a supplicatory offering by Andronikos II Palaiologos – a pious ruler who cared for the needs of the cathedral church of his capital – due to the woeful situation his empire found itself in at the beginning of the fourteenth century. Furthermore, the proposed dating to between 1310 and 1315 allows for the possibility that Patriarch Nephon I – an illustrious patron of the time who served as a connecting link between the art of Thessaloniki and that of Constantinople in the early fourteenth century – played a part in the creation of the Deesis mosaic.

Dr. Konstantinos M. Vapheiades is Lecturer in Byzantine Art History in the Higher Ecclesiastical Academy of Athens (Department of Management of Ecclesiastical Heritage) and Director of the Academy of Theological and Historical Studies of Holy Meteora. He has taught in many of Greece's universities and written research papers and monographs exploring Byzantine and post-Byzantine iconography and painting, especially on Mount Athos and Meteora.