Introduction

The chronicle of John Zonaras, which in some manuscripts bears the title the Epitome of Histories (Epitome), is the longest Byzantine chronicle of which we know, printed in three volumes in the Bonn series.Footnote 1 Extending from the creation of the world to John II Komnenos’ accession to the throne in 1118, it appears to have been one of the best-sellers of the Middle Ages, as indicated by the enormous number of manuscripts that transmit the text or parts of it.Footnote 2 With the exception of a few notable studies dealing with linguistic and thematic aspects of the text, much existing scholarship on the chronicle has been concerned with the examination of the sources which underpin Zonaras’ narrative.Footnote 3 This Quellenforschung has focused particularly on the presence of classical and late antique material in the work, which, among other things, has famously been used for the reconstruction of the lost books of Cassius Dio's Roman History.Footnote 4 Far less scholarly attention, however, has been given to the second major classical text exploited by Zonaras for his account of Roman antiquities, namely Plutarch's Roman Lives.

Plutarch appealed to the educated elite throughout the Byzantine period, with his Greek and Roman Lives being frequently read and cited by Byzantine intellectuals.Footnote 5 Plutarch's biographies were valuable sources of historical information about the Greek, and perhaps more importantly, the Roman past, which was inextricably linked with the history of the Byzantine state.Footnote 6 Byzantine literati particularly appreciated the moral and ethical character of the Lives and would frequently consult them to derive models for comparison and emulation.Footnote 7 Plutarch's Lives, moreover, played a key role in the development of the biographical style of writing, noted in Byzantine historical accounts from the tenth century onwards, and offered useful templates for imperial biographies.Footnote 8

The purpose of this article is to investigate Zonaras’ treatment of the Lives in conjunction with the reminiscences of Plutarch's biographies in other universal chronicles, to examine the uses to which the Plutarchean material is put in the Epitome, and, finally, in the light of these considerations, to assess Zonaras as an author.

Plutarch's Lives in Byzantine Chronicles

The historical material covered by Plutarch in his Lives was to a great extent treated also by the later authors of universal chronicles. Byzantine chroniclers usually traced world history, commencing with the biblical story of the creation and reaching up to the author's own time. Within this wide chronological framework, they would cover subjects related to Greek antiquities, in addition to their central focus on Roman history. It may be surprising, therefore, that the great majority of them would not heavily rely on the Lives as historical and antiquarian sources.

Plutarch's biographies do not seem to have been among the texts exploited at all by John Malalas and the unknown writer of the Chronicon Paschale.Footnote 9 In the works of George Synkellos, George the Monk, George Kedrenos, and Constantine Manasses one finds only short pieces of information taken from Plutarch. For example Synkellos draws on Caesar and cites ‘Plutarch, the philosopher from Chaeronea’ as his source, when he relates Julius Caesar's successful campaigns against the Gauls.Footnote 10 Of particular note is Kedrenos’ reference to the now lost Life of the emperor Tiberius. From the short fragment of Tiberius contained in Kedrenos’ chronicle, we learn that the emperor, enraged at Thrassylus of Mendes, the astrologer of his court, considered his assassination.Footnote 11 Interestingly, the corpus of the Lives seems to have played a more important role for the Chronological History of John of Antioch.Footnote 12 This author employed numerous of Plutarch's Roman Lives, such as those dedicated to Romulus, Marius, Mark Antony, Brutus, Cicero, Marcellus, Lucullus and Sulla, as supplements to his principal source (in all likelihood, a Greek translation of the fourth-century Breviarium of Eutropius, or an intermediary source which made heavy use of it).Footnote 13 What is particularly difficult, however, is to say whether these chroniclers drew directly on Plutarch's works or via some intermediary source.

This short overview of the presence of material from the Lives in the Byzantine chronographic tradition demonstrates that Plutarch's biographies were not particularly popular sources of information among authors of universal chronicles. This observation may allow a better appreciation of Zonaras’ individual approach to and special interest in Plutarch. Indeed, Zonaras is the only chronicler to cite abundantly from a series of Lives in his work. More importantly, he can be seen to choose data from Plutarch and make additions or alterations to his source-text following a programme of his own.

Plutarch's Lives in Zonaras’ Chronicle

Zonaras generally employs the Lives in much the same way as he handles all the major sources he consults in the course of his narrative. As an epitomiser he was particularly concerned with creating a concise account, with brevity being highlighted in the proem of the Epitome.Footnote 14 To achieve this, he would significantly compress the texts at his disposal, summarizing them to the barest outline and omitting a large amount of information. Only sometimes does he quote his sources verbatim to emphasize a momentous event.Footnote 15 As with the rest of his material, he heavily abridges and paraphrases Plutarch's narratives. He tends to give a rough outline of the events recounted in the Lives, skipping details and retaining essential data only.

Before proceeding to a closer examination of the Plutarchean material in the Epitome, it is necessary to point out that the chronicle is neatly articulated in two distinct sections. The first one covers Books 1–6 in the Pinder and Büttner-Wobst edition and deals with Jewish antiquities. Zonaras begins his narrative with the Creation and continues up to the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in AD 70. The second-to-last paragraph of the sixth book is clearly used as a concluding paragraph, as is expressly stated: ‘So, at that time the affairs of the Jews came to an end, when Jerusalem was captured in the final conquest by the Romans’ (‘Ἐνταῦθα μὲν οὖν τότε τὰ τῶν Ἰουδαίων ἐτελεύτησε πάθη, ὑπὸ Ῥωμαίων τῆς Ἱερουσαλὴμ τὴν τελευταίαν ὑποστάσης ἅλωσιν’).Footnote 16 The reference to the Romans offers the author the chance to introduce in the final paragraph of Book 6 the theme of the second large section of his account. This section, Books 7–18, relates the history of the Roman Empire and Byzantium, starting with the mythical story of Aeneas’ arrival to Italy.

Τhe way in which Zonaras inserts Plutarch's material into his work differs depending on the section of the chronicle in which it is included. Information from Plutarch in the Jewish section is introduced into the narrative in the form of digressions, discrete units of information not closely related to the principal theme of the section. In this section the author uses two Lives, Alexander and Artaxerxes.

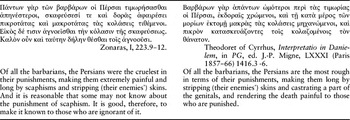

For his description of the apocalyptic visions of the Old Testament prophet Daniel he bases his narrative mostly on Theodoret of Cyrrhus’ Commentary on Daniel. He digresses from Theodoret's account in order to insert a short extract from the Artaxerxes,Footnote 17 where Plutarch talks about scaphism (σκάφευσις), a type of death penalty known in ancient Persia. The term scaphism comes from the Greek word σκάφη (skiff) and denotes an extremely painful punishment in which the condemned person eventually died of septic shock.Footnote 18 Analysing the prophet's vision of the four beasts taken to symbolize the greatest empires of the world, Zonaras tries to account for the bear-like representation of the Persian Empire. He attributes it to the cruel behaviour Persians frequently exhibited, as is indicated by the gruesome punishments they inflicted upon their enemies, such as scaphism. Zonaras explains in detail what the punishment consisted of, essentially rewriting the relevant section of Artaxerxes. What is significant in this case is that Theodoret's Commentary on Daniel, does not mention scaphism at all.

It is obvious, however, that Zonaras deliberately interpolates the punishment of scaphism so as to have the opportunity to embed in his chronicle this short piece of information from Artaxerxes.

The Alexander is the only Plutarchean biography of a famous Greek historical figure exploited in the Epitome. This does not look peculiar, of course, if we consider that the writer pays only scant attention to Greek history.Footnote 19 It is characteristic, for example, that he relies on the works of Herodotus and Xenophon to derive information concerning the Persian Empire, rather than Greek antiquities.Footnote 20 The Macedonian ruler, though, was an exceptional case. He was still very much a central figure in Byzantine culture, as is proved, for instance, by the wide circulation and various recensions of the late antique Alexander Romance.Footnote 21 Interested in relating a story that appealed to his audience, Zonaras would understandably make use of the material on Alexander available to him. This may also be the reason why he offers a relatively long and thorough presentation of the famous king. Based on Plutarch, the writer recounts the leader's military successes as well as memorable episodes that stand out in the narrative of his source, such as Alexander's meeting with Timocleia of Thebes and his exchange with the philosopher Diogenes.Footnote 22 Notably, he gives some space to the divine signs that predicted Alexander's glorious future prior to his birth, his achievements as a young boy and the education he received from Aristotle.Footnote 23 In this respect the way in which Zonaras handles Alexander contrasts with his use of Plutarch's Roman Lives, from which he tends to omit data that shed light on a figure's background.Footnote 24 The history of Alexander is introduced as an excursus from the main narrative line, when the chronicler discusses the Persian-Jewish conflicts.

Ἐπεὶ δὲ μνείαν τοῦ Ἀλεξάνδρου ὁ τῆς ἱστορίας λόγος πεποίηται, καλὸν καὶ τούτου τὰς πράξεις τε καὶ τὰ ἤθη καὶ ὅθεν κἀκ τίνων ἔφυ κατ’ ἐπιδρομὴν διηγήσασθαι, καὶ οὕτως αὖθις ἐπαναγαγεῖν τὸν λόγον πρὸς τὴν συνέχειαν·

Zonaras, I, 329. 9–16.

Now that the account of history made mention of Alexander, it is good to narrate in brief his deeds and dispositions, and whence he came and from whom he was born, and then once again to bring back the account to its continuation.

The passage about Alexander's deeds and character largely constitutes a complete and independent section in itself, which is only loosely attached to what precedes in the narrative. Understanding that his digression into the Plutarchean Alexander deviates considerably from the proper course of his account, Zonaras explains to his readers in advance that he will resume the main thread of his narrative once he has completed the history of Alexander.

The fact that on two occasions Zonaras departs from the main narrative of Jewish history in order to incorporate material from the Lives attests to his strong appreciation of Plutarch as a historian. It shows that Zonaras was intent on using the Plutarchean biographies he had at his disposal, even if they concerned topics to which he would refer only in passing. He would take pains to rework the narrative of his source texts in order to integrate data from Plutarch, eager of course to display his erudition and wide reading.

This is further corroborated when one looks at another text of Zonaras, known as Speech Against Those People who Believe that a Natural Emission of Sperm is a Pollution, addressing the question of whether ejaculation is unclean and therefore not acceptable for a monk.Footnote 25 The writer claims that a monk should not be considered impure on account of ejaculation itself, unless he has sexual fantasies of a woman which lead to the emission of sperm. Even in this case he does not commit a sin, if he is not able to mentally control such dreams. Consequently, he should not be judged and reproached, as if these dreams corresponded to reality. To support his view, Zonaras incorporates as a frame story a short tale known from the Plutarchean Demetrius.Footnote 26 The opening statement reads: ‘It would not be disagreeable to give with a story some weight to the argument. The story is as follows. . .’ (‘Οὐκ ἄχαρι δὲ καὶ τὸ ἐξ ἱστορίας δοῦναι τῷ λόγῳ ῥοπήν τινα. Ἠ δ’ ἱστορία˙’) The tale features a man that fell in love with a woman named Thonis, who would repeatedly reject his advances in spite of the great amount of money he offered her. Ultimately the flame of his love died out when he dreamt of having sexual intercourse with her. Thonis then asked to receive her payment, a request not granted to her by the man. She took the matter to Bokchoris, the leader of the state, who asked the man to bring into the court the amount of gold Thonis demanded of him. Bokchoris then moved the purse with the gold back and forth in the sunlight and urged the woman to receive the shadow as her payment, implying that fantasies are only shadows of the truth. This digression is reflective of Zonaras’ high regard of Plutarch, since the ancient author is the only pagan source on which he relies in his treatise. Aside from Demetrius, he makes use only of writings penned by well-known Church fathers, such as those of Paul, Dionysius of Alexandria, Athanasius of Alexandria, and Basil the Great.

To return to the Epitome, the Lives are of greater usefulness to the author in the second section of the work, when he presents the history of the Roman Empire. He draws upon a series of Roman Lives in cases when the relevant books of Cassius Dio are not available to him, namely Romulus, Numa, Publicola, Camillus, Aemilius, Pompey, Caesar, Brutus and Antony.Footnote 27 His extreme interest in the biographies of distinguished historical figures of ancient Rome is closely connected to the great attention he pays to Roman antiquity in general. Zonaras’ quest for Byzantium's Roman antecedents fit well in the broader intellectual context of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, a period which seems to have witnessed an intensification of interest in Old Rome.Footnote 28 Some indications of this are offered, for example, by contemporary legal manuals and treatises, such as Michael Psellos’ Synopsis Legum, a text that explains several Roman juridical terms, or Michael Attaleiates’ Ponema Nomikon, in which we find a short account of the history of Roman jurisprudence.Footnote 29 Psellos’ Historia Syntomos, moreover, and the historical works of Attaleiates and Nikephoros Bryennios clearly echo their authors’ preoccupations with the Empire's ancient Roman origins.Footnote 30 Dio, too, must have been quite a popular author among learned men of the time. Apart from Xiphilinos who epitomized his history, Kekaumenos, John Tzetzes, and Eustathios of Thessalonike would also include excerpts of Dio's work in their own.Footnote 31 Although the great emphasis Zonaras places on the Roman past fits into this pattern of nostalgia for ancient Rome, it may also be viewed as a result of the chronicler's individual interest in the Roman Empire, and particularly in the forms of Roman government.Footnote 32 His use of Plutarch's Lives assists him in describing the evolution of the Roman political constitutions over time. By selecting Plutarchean material which deals with renowned figures of Republican Rome and the early Roman Empire, he manages to partly repair the loss of certain sections of Dio's history and thus give a more or less uninterrupted account of the Roman political history.

In the Roman section of the Epitome, Plutarch is either the single source that provides the fundamental narrative articulation of the text, or is combined with data drawn from Dio to form the spine of the chronicle. For his account of Romulus, the first king and mythical founder of Rome, Zonaras’ account is based solely on Romulus, offering essentially a summary of the text. Moving on to cover the reign of Romulus’ successor, Numa Pompilius, he draws heavily on Numa from the second chapter of the text onwards.Footnote 33 Thereafter the author leaves Plutarch aside for a while. He consults Dio's history to talk about the five kings of Rome until the overthrow of the monarchy, but soon resumes the use of Plutarch and summarizes Publicola for his narrative of the well-known Roman consul.Footnote 34 He continues to closely follow Dio until he reaches the consulship of Camillus, a point at which he is able to incorporate into his account a considerable amount of material from Camillus.Footnote 35 Afterwards, Dio's work becomes Zonaras’ main authority for a great portion of his text, until the late Republican period. The only notable Plutarchean material is the closely paraphrased short speech of the famous Roman general Aemilius Paullus to the Persian king Perseus, when the latter was brought to Amphipolis.Footnote 36

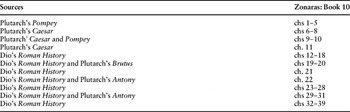

The presentation of the late Roman Republic, contained in Book 10, is slightly more complex. Here, the chronicler mixes a large store of information taken from different Lives with material from Dio. He integrates these pieces of information into his text without naming the different sources from which they originate. Schematically, the compositional structure of this part of the narrative is as follows:

One of the principles that dictates the author's selection of his material is avoiding thematic overlap, which is understandably observed between certain Lives. Zonaras would not repeat the same material found in different Lives, despite slight modifications in the manner in which Plutarch reworked his narrative to draw the reader's attention to the protagonist of each Life. Such repetitions would unnecessarily prolong his account and tire his audience as a result. For example, Zonaras skips the first chapter of the Numa, where Plutarch briefly recounts the legend about the mysterious disappearance of Romulus, and draws on the Romulus instead, in which this episode is discussed more extensively.Footnote 37 The chronicler also attempted to combine the narrative of his sources, in case they partly overlapped with one another. This becomes evident when he stops drawing on the Pompey for a while and starts deriving material from the Caesar. At this point, Zonaras tell us that:

Ἵνα δὲ μὴ δὶς τὰ αὐτὰ ἱστορῆται, ἐν τοῖς περὶ Καίσαρος τὰ λοιπὰ τοῦ Πομπηίου εἰρήσεται, τῇ περὶ ἐκείνου συνεμπίπτοντα ἱστορίᾳ.

Zonaras, II, 314, 6–8.

So as not to narrate the same things twice, I will narrate the rest of Pompey's story along with the story of Caesar, because it coincides with it.

This statement is particularly eloquent, for it reveals something of the chronicler's own method of work. It indicates that Zonaras would select different sources in order to turn the focus of his narrative to certain historical figures. In this case, he relies on Pompey to discuss the statesman's career and individual achievements. However, when Plutarch's text broaches the subject of Pompey's relationship to Caesar, Zonaras prefers to leave the Pompey aside and exploit the Life dedicated to Caesar. This betrays his intention to push Pompey to the ‘background’ of his narrative and bring Caesar to the forefront. Later on, he places emphasis on Pompey's downfall and tragic death by selecting once again material from Pompey, where the focus of the narrative is naturally on the central figure of the Life.Footnote 38 A second example of this strategy can be seen in the way in which Zonaras collates information from Dio and Plutarch to talk about the Battle of Philippi.Footnote 39 The chronicler draws on Dio to give the events of the battle through the eyes of the victors, Octavian and Antony. However, to relate the assassination of Crassus and the fate of Brutus afterwards, he opts to consult Brutus, thus inviting his readers to view the aftermath of the battle from the perspective of the defeated Brutus. This is also the reason for which he changes his sources in the description of the Battle of Actium.Footnote 40 It is Dio's text that provides information for the battle itself. The chronicler, though, relies on the Plutarchean Antony to narrate what followed immediately afterwards. The material he derives from Antony, including the scene in which Cleopatra finds Antony sitting in silence at the prow of the ship, highlights the general's miserable state after his humiliating defeat.

There are some further considerations on Zonaras’ approach to the Roman Lives which are worth mentioning. A comparison between the text of the Lives and the corresponding sections of the Epitome reveals that the chronicler had evidently less taste for the detailed and comprehensive portrayals of Roman individuals than his source. He supplies very little of the general information about the characters’ background and most distinctive features usually found in the introductions and early chapters of the Lives. He does not talk about Numa's education and origins, nor does he refer to Publicola's lineage and notable qualities. He excludes Plutarch's general remarks on Camillus’ career and achievements contained in the opening chapters of Camillus and pays limited attention to the portrait the Roman historian draws of Pompey at the beginning of his Life. In his presentation of Caesar, moreover, Zonaras omits all material provided by Plutarch about Caesar's education and gradual rise to power. In a similar fashion, comments and judgments scattered throughout the Lives about the personalities of historical figures are normally also left out of the narrative.Footnote 41

It can be noted, additionally, that the chronicler shows limited interest in aspects of ancient Roman society and civilisation, as demonstrated by the omission of material concerning social institutions, traditions, and customs of the early Roman Empire. For example, Zonaras excludes from his text the numerous foundation myths of the Roman nation appearing in Romulus, as well as information about festivals, means of worship, laws, and religious institutions introduced by the first Roman kings, including both the Vestal virgins and the Salii priests.Footnote 42 Neither does he tell us of the unlucky days of the Romans, or the feast of the Nonae, about which we read in Camillus.Footnote 43 It is therefore certainly not coincidental that Plutarch's descriptions of the temples erected in Rome do not attract the chronicler's attention either.Footnote 44

It is not hard to understand why Zonaras saw fit to exclude such material from his composition. Information about the characters of Roman individuals as well as details about everyday life in ancient Rome were not immediately relevant to the twelfth-century readers and were therefore cut away. The writer evidently tried to tailor his Plutarchean material to the needs and interests of the contemporary audience. Significantly, though, he maintains in his narrative Roman elements which were still connected to Byzantine culture in some way. He sees fit, for instance, to tell us of the reformation of the Roman calendar instituted by Numa, who introduced January and February into the calendar and created the twelve-month year.Footnote 45

The Epitome’s passage dedicated to the reign of Numa deserves particular attention, for it mirrors Zonaras’ aims to adapt the Roman Lives of Plutarch to the social, religious and cultural context of his own time. Although the chronicler was inclined to abridge the extensive portraits of his exemplar, in the case of Numa, he did so fulfilling his own moralising agenda. In the opening chapters of his Life, Numa is described as a virtuous, self-disciplined and wise man, who, averse to all kinds of entertainment, devoted himself to the service of the gods.Footnote 46 We read that, seeking solitude after his wife's passing, Numa:

ἐκλείπων τὰς ἐν ἄστει διατριβὰς ἀγραυλεῖν τὰ πολλὰ καὶ πλανᾶσθαι μόνος ἤθελεν, ἐν ἄλσεσι θεῶν καὶ λειμῶσιν ἱεροῖς καὶ τόποις ἐρήμοις ποιούμενος τὴν δίαιταν.

Numa, 4.1-4.

forsaking the ways of city folk, determined to live for the most part in country places, and to wander there alone, passing his days in groves of the gods, sacred meadows, and solitudes.Footnote 47

At this point, Plutarch also recalls the legend of Numa's purported union to the nymph Egeria, thanks to whom he was given divine wisdom. Indeed, one of the key elements of Plutarch's depiction of Numa is his strong connection with the divine.

Zonaras now, echoing his source text faithfully, introduces Numa as a ‘man who was known to all for his virtue’ (‘ὄντα ἄνδρα γνώριμον πᾶσι δι’ ἀρετήν’).Footnote 48 He eliminates, however, all references to Numa's devotion to the Roman gods, including his ‘marriage’ to Egeria. Indicative of this are the two minor, but telling, alterations to the aforementioned extract that he makes.

Ὁ δὲ Νομᾶς ἐκλιπὼν τὰς ἐν ἄστει διατριβὰς ἀγραυλεῖν τὰ πολλὰ καὶ διατρίβειν ἤθελεν ἐν λειμῶσι καὶ ἄλσεσιν.

Zonaras, II, 19.21-22.

Numa, forsaking the city folk, determined to live for the most part in country places and to live in groves and meadows.

In this case, the chronicler copies Plutarch almost verbatim, only deleting elements suggestive of Numa's connection to paganism.

The image which emerges of Numa later on in the Plutarchean text is that of the ideal secular and religious ruler. In chapter 8 of the Numa (Numa 8), for example, Numa is presented as a just and peace-loving king, who tried to tame the harsh and warlike temper of the Roman people. To achieve this, he would organize sacrifices, processions and dances in honour of the gods, rituals which were both beneficial and pleasing to the people.Footnote 49 Launching an extensive programme of legislation, moreover, he introduced a series of political and religious reformations. Through his laws, Numa aimed to regulate the Romans’ relationship to and worship of their gods. This is exemplified by his ordinances against the human- or beast-like representation of deities. For a very long period of time, therefore, Romans did not erect shrines or idols to venerate their gods, for they understood that only spiritually could they approach the divine.Footnote 50 Changing the religious practices current in his time, Numa banished blood sacrifices too.Footnote 51 In chapter 16, moreover, Plutarch writes that, to secure peace among citizens, the king distributed land to those who were destitute, as he considered poverty one of the reasons people would resort to criminal activity.Footnote 52

These accomplishments must have made a strong impression on Zonaras, who repeats each one of them. Once again, however, the omissions in his narrative are striking. We can look particularly at how he reworks Numa 8. Although he informs us that the Roman leader managed to soften the fierce disposition of his subjects, he does not tell us of the means through which he was able to achieve this, namely by organizing several festivities and celebrating pagan deities.Footnote 53 More remarkable still, he ‘conceals’ from his audience the ideological context from which Numa's religious policy is said to have originated: the doctrines of the Greek philosopher Pythagoras. The chronicler does not copy Plutarch, who claims that Numa introduced bloodless sacrifices in imitation of Pythagorean rituals, and offers his own explanation instead, which is the belief that ‘gods, who are the guardians of peace and justice, should be clear of murders’ (δεῖν γὰρ τοὺς θεούς, εἰρήνης καὶ δικαιοσύνης φύλακας ὄντας, φόνου καθαροὺς εἶναι).Footnote 54 Although this statement is not attributed directly to Numa, it serves to emphasise the piety of the Roman king.

Throughout the Plutarchean text readers are invited to understand the king's exemplary attitude as a result of the great influence the Pythagorean philosophy exerted on him.Footnote 55 Not surprisingly, Zonaras excludes from his account all the pro-Pythagorean material contained in his source. By deliberately omitting such information from his narrative, the chronicler aims to play down Numa's pagan background and draw a picture of a king who essentially embodies the qualities of a good Christian. He presents us with a Roman leader who managed to bring peace to his people, forbade them to venerate idols and taught them to relate to the divine through some kind of ‘prayer’. He is also viewed as an example of philanthropy, seeking to alleviate the sufferings of the poor. It is clear that Zonaras saw that the Numa was a text which had the potential to undergo a ‘Christianisation’ of sorts.Footnote 56 This then elucidates both the author's awareness of the inherent ethical and moral purposes of the Lives, as well as his inventiveness in adjusting Plutarch's text so as to make it more meaningful to Byzantine readers.Footnote 57

One more passage of the chronicle deserves particular attention. At a certain point in his narrative, Zonaras makes a parallel between a Roman statesman and a Greek one, namely the Roman king Tarquinius Superbus and Thrasybulus, the tyrant of Miletus in the seventh century BC.Footnote 58 Just as Plutarch arranges his Lives in pairs, the chronicler too juxtaposes the story of a Greek historical figure with that of a Roman. As we read in the Epitome, Sextus, the son of Tarquinius who seized power in the city of Gabii, asked his father how he could surrender the city to him. Rather than sending a written reply to his son, Tarquinius cut down the tallest stalks of corn in his field, implying that Sextus must primarily exterminate the most prominent of the Gabii citizens. Zonaras recalls that Herodotus narrates a similar story. Periander of Corinth appealed to Thrasybulus for advice on rulership. Thrasybulus responded by cutting the tallest stalks of corn in his field, meaning that he should by all means eliminate the most distinguished of his subjects who might pose a threat to his authority. Zonaras combines pieces of information from two different sources available to him, Herodotos and Dio, and presents them in a parallel format. Although the author used individual Lives only, it might be tempting to speculate that in this case he was influenced by Plutarch as a literary model, and attempted to imitate the broader organisational scheme of his exemplar.

Conclusions

To recapitulate, unlike his fellow chronographers, Zonaras makes heavy use of Plutarch's Lives in his Epitome. There are references and allusions to the Lives in other universal chronicles as well, but these are scarce and rather limited in scope compared to the great deal of information included by Zonaras in his own text. The digressions into Artaxerxes and Alexander make it clear that the author held the Plutarchean biographies in high regard; one observes that he was keen on tampering with his sources or deviating from the proper course of his narrative in order to exploit the Plutarchean material available to him. An additional reason why Zonaras drew extensively on the Lives, in particular those of Roman individuals, is that he sought to reclaim parts of Dio's history which were lost to him, and in this way give a timeline of the development of the Roman polity. The great interest he exhibits in a number of Plutarch's Roman Lives places him at the heart of contemporary scholarly activity, as it corresponds to the vogue for Roman antiquities observed among Byzantine literati of the period. Αt the same time, though, it echoes the chronicler's own intellectual pursuits and cultural attitudes.

Zonaras selects and arranges the data he derives from the Roman biographies of Plutarch in such a manner so as to lay greater emphasis on a certain figure at the expense of another. The type of information he systematically cuts away from his account, attempting to write succinctly, betrays his individual preferences and tastes as an author. Unlike Plutarch, he was disinclined to elaborate on the background and the personality of a Roman figure and offer many details on aspects of Roman civilisation, subjects which were alien to the current Byzantine traditions. Furthermore, by implicitly ‘christianising’ the portrait of Numa, Zonaras tried to tailor the Roman material he took from Plutarch to suit the social and religious milieu of his time. The structure of the Lives in pairs might have also provided him the inspiration to adopt the same pattern in his presentation of the material he collected from different sources. Such processes of selection, adaptation and reinterpretation indicate that Zonaras’ treatment of his source texts was governed by certain sets of principles, and show the chronicler to be not merely a copyist of earlier writings, but instead a compiler with his own authorial preoccupations.