Aristophanic comedy is a common and vibrant point of reference in modern Greek culture, diffused across all demographic groups and throughout the arts. It holds a significant position in modern Greek theatrical life, with a plethora of translations on the market, a regular presence at the annual summer Athens and Epidaurus Festival (often featuring more than one production of the same play), and the perpetuation of Karolos Koun's and Alexis Solomos’ legacy in drama schools. It has also inspired artistic creation in other genres and media with great success, from Manos Hadzidakis’ and Dionysis Savvopoulos’ musical compositions for performances of drama, to Tasos Apostolidis and Yorgos Akokalidis’ best-selling adaptations in comics and Evgenios Spatharis’ shadow-theatre performances. Last but not least, Aristophanes’ oeuvre holds a significant position within the modern Greek education system. Even in primary schools, it is a popular source for school adaptations; it is included in the curriculum of secondary schools, alongside Sophocles and Euripides; it constitutes an undergraduate course in all faculties of Literature in the country, and has been the subject of many doctoral theses and articles.Footnote 2

Equally established in the modern Greek consciousness is Karagiozis, both as a genre (the Greek version of shadow theatre) and a character (the eponymous protagonist, and the archetype of the Greek temperament). The genre constitutes an example of authentic folk art shaped through the ages and, despite its frequent omission from theatrical historiography, rooted in national identity.Footnote 3 On the μπερντές, which is a white, illuminated sheet of fabric, we see Karagiozis’ shack on the left (the West) and the Pasha's Seraglio on the right (the East); the narrative time is supposedly the Ottoman occupation, broadly speaking, whereas the place is totally undefined. There are about fifteen stock characters, whose puppets are two-dimensional figures made of papier mâché, hardened leather, or plastic; the action is developed linearly and on-screen (no flashbacks, flash-forwards, or parallel stories), usually representing the events of one day, and the form is always dialogic (there is no narration). Behind the screen, the performer (καραγκιοζοπαίχτης), either alone or with his assistants, manipulates the puppets and creates their voices. Usually it is he himself who constructs the sets and the puppets and writes the script. Musicians or recorded music accompany the show, which starts with a σέρβικος and ends with a καλαματιανός.

A Greek's initiation into Karagiozis begins from a very young age, and is already institutionalized in Year One textbooks where one meets the main characters and reads an extract from Spatharis’ Ο Μέγας Aλέξανδρος και το καταραμένο φίδι. Footnote 4 In summer touring performances and permanent theatres, through government-approved performances for schools, via the Spathario Museum and its annual festival, through adaptations on state television, in theatre (with actors), and in illustrated books and comics, and even through folkloric souvenirs for tourists, Karagiozis becomes part of common Greek experience and identity. And despite the clear turn of modern shadow theatre towards children's entertainment, Karagiozis has also inspired ‘mature’ fine arts such as Kambanellis’ play Το μεγάλο μας τσίρκο,Footnote 5 Koun's direction of the Acharnians, and Savvopoulos’ song Σαν τον Καραγκιόζη.Footnote 6 Academic interest in the topic, nationally and abroad, is also on the increase; indicatively, the Centre of Byzantine, Modern Greek and Cypriot Studies in Granada (founded by the Greek state through its embassy in Spain in July 1998, and supported by the Onassis, Niarchos, and Ouranis Foundations) is running a project under the auspices of the Hellenic National Commission for UNESCO to support Greece's claim for the recognition of Karagiozis as part of its Intangible Cultural Heritage.Footnote 7

As mentioned above, Aristophanes and Karagiozis have been occasionally correlated on a theoretical level through scholarly works and on a practical level through artistic creation. The correlations between Karagiozis and Aristophanes noted by scholars refer either to the aesthetic similarities or the genealogical relationship between the two comic genres. In the first group, Whitman's work on the common nature of the comic hero is typical,Footnote 8 while Kakridis highlights the structural resemblance of the plots, and Myrsiades the connections on the level of political satire.Footnote 9 The attempts of the second group, which notes a genealogical relationship (notably represented by Reich), remain speculative.Footnote 10 As for the creative, bi-directional, encounter of the two genres, the most direct and elaborated instances have been Koun's directorial approach with the Acharnians (1976), and the adaptations of Aristophanes’ plays for Spatharis’ shadow theatre produced by ERT (state radio and television).Footnote 11

The first traceable encounter between the two genres is the 1919 script Ο Καραγκιόζης μέγας βεζύρης. With its scenario of women taking over government offices under Karagiozis’ role as Grand Vizier, it clearly draws on the Ecclesiazusae and Lysistrata. The script was published as serial episodes in the newspaper Ακρόπολις (27 September-13 November 1919) and bears the signature of the puppeteer Antonis Mollas. However, the content shows that the author could not have been the poorly educated puppeteer but someone highly educated.Footnote 12 This script was not destined to be performed. As far as performances are concerned, it is noteworthy that whereas ancient Greek tragedy invaded shadow theatre in the 1930s (with versions of Oedipus Rex by Vasilaros, Voutsinas and Kouzaros),Footnote 13 Aristophanes had to wait until the 1970s. This delay can be attributed to the Metaxas dictatorship, the military junta, and the entire polarized political situation in between. Even in Κλασσικά εικονογραφημένα (1950s), the Greek equivalent of the American Classics Illustrated series and, an important source of inspiration for Karagiozis artists,Footnote 14 only Wealth was included, i.e. the least political of Aristophanes’ comedies (with a script by Vasilis Rotas). Thus it is not surprising that the first adaptation of an Aristophanic comedy for shadow theatre should have taken place abroad: the Birds, performed by Panayiotis Michopoulos at Harvard University in honour of Cedric Whitman (9 May 1971).Footnote 15 Within Greece, it was the μεταπολίτευση and the dynamic role of ERT during that era that brought Aristophanes to the shadow-screen: Spatharis’ performance of Yorgos Pavrianos’ adaptation of Frogs (1978) and Marianna Koutalou's adaptations of Wealth, Peace, Birds, and Acharnians (1985-9).Footnote 16

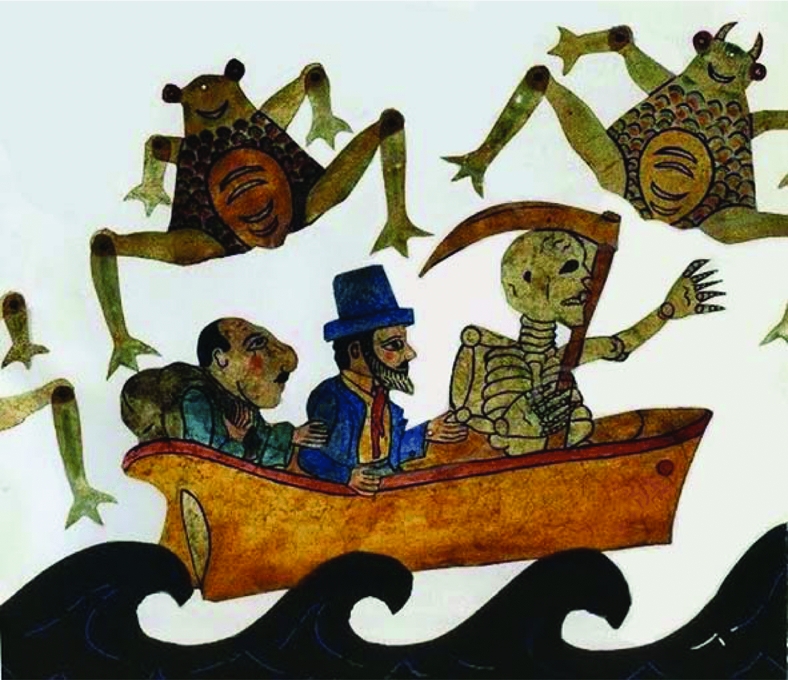

Evgenios Spatharis (1924-2009) was a painter (see Fig. 1) and the most prominent performer of Greek shadow theatre. Inspired by his father Sotiris Spatharis, himself a famous puppeteer, he began his career in Athens during the German occupation. From 1966 to 1992 he performed on state television, bringing Karagiozis to mass audiences, and collaborated with many theatres in staging Karagiozis with actors. He also made many audio and video recordings of his performances and published illustrated scripts as well as his book Ο Καραγκιόζης των Σπαθάρηδων.Footnote 17 He also took his performances on tour and participated in many exhibitions and conferences abroad, receiving several awards and establishing international recognition of the genre. In 1991 he created the Spathario Museum in Maroussi, which offers special programmes for schools and organizes an annual festival. As a result, Spatharis’ voice has been linked in public consciousness with Karagiozis’ character, and his name has become virtually synonymous with the genre.

Fig. 1. Spatharis (2000), Βάτραχοι του Αριστοφάνη, tempera on cardboard 44 × 60. From left to right: Euripides, Aeschylus, Karagiozis, Nionios, Charon. Christos and Polly Kolliali Collection, by kind permission of Polly Kolliali.

Adaptation and codification

Although adaptation theory has almost exclusively dealt with literature-into-film case studies and does not yet have a generally accepted terminology, it offers some useful insights.Footnote 18 Central to my discussion of Aristophanes in Greek shadow theatre will be the concept of transcoding. Hutcheon defines it as intersemiotic transposition from one sign system to another, as necessarily a recoding into a new set of conventions as well as signs.Footnote 19 She distinguishes transcoding on the level of form (shifting a work from one medium or genre to another) and cultural transcoding (shifting a work from one cultural context to another). She labels the latter kind of transcoding as ‘indigenization’, but this term only explains geographical displacements and neglects the temporal axis of cultural differentiation (ancient Greece → modern Greece).Footnote 20 As for the form, which is the aspect that concerns me here, Hutcheon takes account of various adaptations from one medium to another (print texts, theatre performances, films, television series, radio plays, operas, musicals, ballets, graphic novels, video games – one transcribed to another) but only sporadically refers to the mixture of genres.

Shadow theatre is of course a medium. Instead of actors performing on a stage in front of an audience, actors’ or puppets’ shadows are displayed through a white curtain to the audience. As a medium, as a technique in other words, shadow theatre is common all over the world and may well present any play script. But Greek shadow theatre is definitely a genre, with specific structural, narrative, characterological, pictorial and ideological conventions. As such, it ‘both constrains and enables; it both limits and opens up new possibilities’ when it comes to adapt other works.Footnote 21 Specifically with regard to Aristophanic comedy, the overlaps enable and invite the combination of elements characteristic of both traditions.

The two comic genres have indeed a lot in common – principally both are performed and both are comic. In previous decades, the ‘heroic’, ‘historic’, ‘social’ and ‘brigand’ plays, where the end was usually tragic, represented about half of the repertoire of Greek shadow theatre – the other half being the comedies. But in its contemporary form (late twentieth century onwards, which is the scope of this article), the standard comedies predominate (i.e. those where Karagiozis undertakes a job and messes up). In these comedies, just as in Aristophanes’ comedies, the gastronomic and the fantastical elements dominate along with social and political satire, and we can name a plethora of multifarious secondary themes they have in common, such as jobs, nostrums, utensils, and animals.Footnote 22 The comic protagonists – always Karagiozis in shadow theatre – have the same properties (fluency, humour, irony, comic inspiration etc.) and stylistically identical idiolect (comic accumulations, compound words, invention of names, jokes παρὰ προσδοκίαν etc.).Footnote 23 But there are also significant differences, such as the absence or concealment of the sexual element in Karagiozis. Most of these are related to the differing extent of codification of each genre.

Greek shadow theatre is a highly codified genre in most respects – something that may be attributed to its traditional character. Even though the puppeteers partly improvise during the show, there is a standard repertoire which imposes a strict structure. Following Propp, Sifakis uses the term ‘functions’ for the successive episodes of Karagiozis’ comedies, which are: (a) the Pasha lacks something or needs a task to be done; (b) Hadjiavatis intercedes; (c) Hadjiavatis and Karagiozis work together to find someone to undertake the task; (d) Karagiozis eventually undertakes the task; (e) he ridicules the other characters, something that Sifakis regards as the core function; (f) Karagiozis gets into trouble and finally triumphs.Footnote 24 Most of the characters (and in particular the leading ones) are stock characters: their names, appearance, speech, status and relationships are standard. The same is true of iconography: shadow-puppets are always displayed in profile, and buildings are always arranged frontally. Similarly, its ideology is simple and designed to give comfort to the audience: though Karagiozis is amoral, his compassion towards and forgiveness of the poor are unquestionable.Footnote 25

Aristophanic comedy, on the other hand, is much less codified, and can verge on the anarchic. Characters may be of a type or function (εἴρων, ἀλαζών, βωμολόχος) and their masks may have been standardized in Aristophanes’ time (at least for common roles, like slaves and old women), but as characters they are not stereotyped.Footnote 26 Plots follow a general structure (problem – comic plan – result) which is comparable to that of shadow theatre, but each comedy organizes its sections differently and with great flexibility.Footnote 27 The settings range from the underworld to the sky. The ideology is anything but obvious or one-dimensional: it is never clear whether the poet promotes or satirizes the proposed idea, and whether this idea leads to a utopia or a dystopia.Footnote 28

In the following sections, I examine both genres in order to argue that performing Aristophanes as part of Greek shadow theatre involves more than an unconditional shift of medium. Instead, I explore the transcoding possibilities, focusing on two aspects: obscenity and role allocation (casting). Other equally crucial aspects include plot structure or iconography, but space will not permit these to be addressed here. Since ‘theoretical generalizations about the specificity of media [and genres, I would add] need to be questioned by looking at actual practice’,Footnote 29 I focus here on Evgenios Spatharis’ shadow performances of Peace and the Frogs as case studies, and analyse them in the light of adaptation theory.Footnote 30

For the ease of readers not familiar with Aristophanic comedy, I will summarize the plot of the two plays. In Peace, the peasant Trygaeus rides a giant dung-beetle in order to reach Olympus and request Zeus to stop the war. Once he arrives, he learns from Hermes that the gods, disappointed by mortals, have left Olympus, and that War has captured Peace and is crushing the Greek cities in his mortar. Trygaeus summons fellow-peasants from many Greek cities and, after bribing Hermes in order to remain silent, they collaborate and rescue Peace, as well as Opora (Spring) and Theoria (Wisdom) who were also captives. They then return to Athens and celebrate the restoration of Peace. However, not everyone is happy, with some arms-sellers complaining that they have now lost their livelihoods. But the universal joy is great and Trygaeus is given Opora as a wife.

In Frogs, the god Dionysus, along with his slave Xanthias, travels to the underworld with the aim of bringing Euripides back to life and to Athens, where he claims that not a single good tragedian exists any longer. Dionysus asks Heracles, whom he has unsuccessfully tried to imitate by donning his outfit, what is the best way to Hades. As he is afraid to kill himself (the quickest way down), he decides to go via Lake Acheron. Charon ferries him across in his boat, while Xanthias has to walk around the lake. As Dionysus is rowing, the chorus of frogs disturb him with their croaking; but once he and Xanthias have arrived at the shore, a second chorus, consisting of initiates in the Mysteries, appears. After some comic episodes between Dionysus, Xanthias, Aeacus, a maiden, a baker, and an innkeeper, Dionysus is informed that Euripides and Aeschylus are competing about which one is the best tragedian. He thereupon organizes a contest in which he is the judge. The tragedians compare (by praising their own and mocking the other's verses) their poetic style, characters, prologues, and choral songs, and even place their verses on a pair of scales, where Aeschylus is proven to be ‘weightier’. Finally, Dionysus asks the contestants for their political advice, on the basis of which he decides to award Aeschylus the Chair of Tragedy rather than Euripides.

At this point, it is important to clarify that both the phenomenon of Aristophanes’ adaptation into shadow theatre and the case studies employed are exceptional, and far from the performative tradition of Karagiozis of the pre-television era. First, the traditional shadow performers were not educated enough to know Aristophanes; indeed, both adaptations were composed by two university-educated writers who gave their scripts to Spatharis to perform. The second departure from tradition is that the καραγκιοζοπαίχτης is not performing his own script or undertaking any improvisation. Finally, the performances are recorded in a studio without an audience, contrary to the authentic, oral character of the genre, for which interaction with the audience is essential. However, given that Karagiozis’ performances on television date back to 1966 (with Spatharis at the Πειραματικός Σταθμός Τηλεοράσεως) and have continued to some degree (with other performers) up to the present day, this version of shadow theatre is anything but negligible.

Placating the maculate Muse

Obscenity is one of the greatest challenges that shadow theatre has to face when adapting ancient comedy. For obscenity is a radical element of Aristophanic comedy, both as a factor of humour (thematic, verbal and scenic) and a ritual necessity (to celebrate Dionysus). Corresponding to its crucial importance is the considerable amount of scholarship it has generated.Footnote 31 Henderson's The Maculate Muse (1975) remains the basic work in its compilation of sexual and scatological references; Rosen offers a reading of obscenity in Old Comedy in the light of the iambic tradition;Footnote 32 Robson recapitulates this in his technical theorization of Aristophanic humour;Footnote 33 Halliwell discusses the ritual and democratic function of ribaldry;Footnote 34 and Sommerstein has examined sex-based differentiation in Attic Greek, including obscenity in comedy.Footnote 35

Modern Greek shadow theatre, on the contrary, has been ‘purified’ of its obscenity. Indeed, its history charts an evolutionary course. Deriving from the sexually-laden Ottoman shadow theatre (performed only before male audiences, with ithyphallic Karagöz), the Greek version retained a similar character for many years, until the beginning of the twentieth century, which means for half of its history, although the phallus vanished early.Footnote 36 The demand for the ‘Hellenization’ of the genre, the recurrent police bans on performances, and the demographic change of the audience in the 1910s (from a rural, male one to a popular and proletarian one) led to a ‘sanitization’ which culminated in massive television productions in the 1980s and the turn towards younger audiences.Footnote 37 Kiourtsakis’ remarkable book on Karagiozis and carnival, informed by Bakhtin's theory of the culture of popular laughter, is the best study of the ‘sterilization’ of the genre, as he calls it.Footnote 38 In its contemporary form, physicality is strongly present in the Greek shadow theatre (through scenes of dance, eating, fighting and the use of props) but without the obscenity. There are only some scatological vestiges and very few hints of sex; indeed, even less tolerance is shown for sex.

Since retaining obscenity would infringe the moral code of shadow theatre whereas eliminating obscenity would falsify the Aristophanic core, the most moderate and efficient solution might seem to be to reduce Aristophanes’ bawdiness. In the course of its sanitizing process, Greek shadow theatre undertook the following transcodings: (a) Sexual urges have been absorbed by Karagiozis’ hunger; his desire for food is often expressed as a confession in erotic terms, and he often wakes up sweaty, having dreamt of a hot loaf. (b) Sexual desire is undermined or concealed by a romantic ethos, e.g. the competition of the lovers for the hand of the Vizier's daughter, the Nionios’ flirting-serenades. (c) Obscenity is diffused into other sociolects: baby-talk (poo, caca, peepee, weewee etc.) by the Kollitiria (Karagiozis’ children), or by Karagiozis himself while being thrashed; also Stavrakas’ slang and Barba-Yorgos’ supposed Vlach.Footnote 39 (d) Other insulting terms (e.g. animals’ names) are used, usually to laugh at someone's appearance or mental capacity, and of curses.Footnote 40 In terms of vocabulary, none of these options approaches obscenity, but thematically the core of obscenity is preserved, while sexual and scatological overtones are (or may be) implied.Footnote 41

Which of these options the adaptor decides on is principally determined by the audience and the medium. Koutalou's television adaptations were produced by ERT (state television) and were addressed to children; Pavrianos’ Frogs was broadcast as a live performance by ERA (state radio) and addressed to the general public. Inevitably, both of them were conservative, the former much more so. Moreover, the direction of the adaptation (which genre is infused into which) enables different ranges of options: the use of shadow theatre in performances of Aristophanes (such as in the production of the Acharnians by Koun) can be more liberal than the use of Aristophanes in shadow theatre productions. Last but not least, the source-play itself is a crucial factor: the phallic element is so essential to the Acharnians or Lysistrata that these plays become more or less ‘un-adaptable’ in shadow theatre terms. For this reason I have selected two less obscene, and thus more readily adaptable plays. The obscenity in Peace is benign and celebratory rather than aggressive and abusive, whereas in Frogs, more than in any other play of Aristophanes, obscenity remains at a low level.Footnote 42

In Frogs, ‘virtually all of the obscenity in the play is contained in the first scene; most of it is scatological’.Footnote 43 The ‘shitting-climax’ of the introductory crosstalk between Dionysus and Xanthias (1–10), Dionysus’ farting-disputation against the frogs while rowing across the river (221 f.), and his self-soiling when listening to Aeacus’ threats (479–90) are the most characteristic instances. In Pavrianos’ adaptation, none of these has been retained, even implicitly; and this contributes to the overall abandonment of the Dionysian core of the play, as I shall analyse later. As for Peace, its prologue is definitely a scatological παναισθησία, not only verbally but also scenically, as we watch Trygaeus’ slaves feeding the giant beetle with excrement. In Peace, ‘the dung-beetle embodies a more complete reversal of the proper order of things: he eats rather than excretes excrement, his foul-smelling mouth is like an anus, he loves what we naturally abhor’, thus serving ‘to characterize the unnaturalness of wartime’.Footnote 44 In Koutalou's adaptation the beetle is presented speaking in highly cultivated terms; it has a proper dinner with Karagiozis, eating pumpkin-pies (the inspiration must come from v. 28). Though this is an interesting adaptation, through quasi-humanization the beetle loses much of its symbolic and aesthetic function.

Sexual obscenity is far less vigorous in these two plays. In Frogs it is sporadic and isolated, mostly referring to Cleisthenes (48, 57, 422–7). The play prioritizes engagement with ‘gender’ over ‘sex’, through the Dionysian-Herculean polarity and the cross-dressing games, which are excluded from the adaptation. In Peace, sex has a largely symbolic presence: ‘perverted’ sex (in the first half of the play) is exchanged for ‘natural’ sex (second half), barren land for fertilization, war for peace.Footnote 45 Subsequently, eating and sex are closely connected with clear connotations: ὁ πλακοῦς πέπεπται, σησαμῆ ξυμπλάττεται (869); τοῦ μὲν μέγα καὶ παχύ,τῆς δ᾿ ἡδὺ τὸ σῦκον (1351–2) etc.

It is precisely here that the adaptability of Aristophanes into Greek shadow theatre occurs, without either of them being undermined: through the transcoding of Karagiozis’ lust for food. Thus, an ambiguous vocabulary may be retained, bridging ancient with modern humour, without shocking, or ‘corrupting’ the younger members of the audience. However, Koutalou's adaptation does not exploit this opportunity. Instead, it tries to apply the transcoding method of concealing sex with a romantic ethos: whereas in Aristophanes Opora is a mute character, a mere object of sexual and gastric lust (706–12), in the adaptation she is given speech, and has a reciprocal flirt with Trygaeus:Footnote 46

However, in the final scene, nothing reminds us of a marriage ceremony. The newlyweds appear in separate film–frames (actually two μπερντέδες were used), not exchanging a word, a long distance apart, and with many shadow-puppets between them; their relationship ends up not only as asexual but as non-romantic.

In these adaptations the only moment of verbal abuse, yet one that is far from obscene, is the exodus in Frogs, after Aeschylakis is announced as the winner (1472–5 in the original):

Pavrianos eliminated obscenity by not trying to transcode it at all; the overall wording is colloquial, and the rebetiko (!) music of the show preserves an ‘adult’ atmosphere. In Koutalou's adaptation the overall wording is decent, with much didacticism. She attempts some transcoding (e.g. pumpkin-pies instead of shit) but the result obscures, if not reverses, the Aristophanic symbolism, which is precisely to describe a ‘shitty’ society. My conclusion is that, with regard to obscenity, the restrictions imposed by the medium (the state television and radio here) are even stronger than the incompatibilities between the two genres, which offer some effective transcoding possibilities. In live performances a more liberal processing of obscenity would have been enabled.

Casting

As mentioned earlier, the casting of characters is perhaps the strictest convention of Greek shadow theatre. So, when it comes to transcoding a text such as a drama by Aristophanes with its own characters, ‘the key to the process is the casting of the borrowed plot, to some extent, with the stock characters of the shadow theatre’.Footnote 47 The possible adjustments vary from a minimum, where only Karagiozis is introduced into the plot, to the opposite extreme, where all the dramatis personae of the original are replaced or merged with the stock characters, ‘enriching the text with the dialects and the morals of the shadow puppets’.Footnote 48 The former is true of Koutalou's Peace, whereas Pavrianos’ Frogs moves toward the latter. However, it is the kind rather the quantity of the adjustments that concerns me here: in order for a replacement or merger to link the two genres (which is the programmatic intention of both our case studies), the characters should be typologically compatible as well (e.g. the swashbuckler Stavrakas with Lamachus).

A wider debate here is whether Aristophanic characters are types or not. The popular εἴρων – ἀλαζών – βωμολόχος scheme is applied in detail by Cornford,Footnote 49 whereas Silk rejects this neo-Aristotelian model, highlighting the inconsistency and the discontinuities of Aristophanes’ characters.Footnote 50 However, even if this model describes alternating functions rather than types, we have to admit there are some primary functions for each role. Here I use the term ‘type’ very loosely, referring to the status of characters (gender, occupation, age, style etc.) alongside their temperament and function.

With this in mind, let us consider some of the replacements and mergers attempted by Pavrianos in Frogs.Footnote 51 Hercules is impersonated by Stavrakas, the macho-man (koutsavakis) of shadow theatre: his appearance indicates the former but the slang he uses clearly suggests the latter. Aiakos, Pluto's servant, is impersonated by the barbarous Velighekas: again we see a demon, but he speaks Velighekas’ Arvanitika (or, more precisely, a comic perception of Arvanitika). As for Pluto, we do not see him on screen but only hear his voice. Since his voice is as slow and imposing as that of the Pasha, the cruel governor, we can also assume that Pluto is impersonated by the Pasha, who also rarely appears on stage in the Karagiozis repertoire. These amalgamations are successful, since they are based on similarities of character, for Hercules is indeed ‘macho’, Aiakos is barbarous, and Pluto a cruel governor.

The replacement of Aeschylus by Mikis Theodorakis (who is given the name Aeschylakis) and of Euripides by Manos Hadjidakis (who is given the name Euripidakis) constitutes a brilliant analogue.Footnote 52 The diminutive suffix –akis is added to the tragedians’ names, presumably, just because both of the composers’ surnames end in –akis, so that the correlation becomes clearer.Footnote 53 Here we do not have stock characters from shadow theatre, but two recognizable public figures. Theodorakis, whose music was widely viewed as pompous and political, and Hadjidakis, whose songs were considered to be lyrical and erotic, are aligned with Aeschylus and Euripides respectively, presented with the same partiality with which Aristophanes decided to portray the tragedians. In fact, Theodorakis also composed many ‘light’ erotic songs, and Hadjidakis ‘powerful’ political songs.

In the same way that Aeschylus appends a ληκύθιον to Euripides’ lyrics (1199 f.), Aeschylakis appends a πιάτο σκορδαλιά (a dish of garlic sauce) to Hadjidakis’ rhyming lyrics: ‘χάρτινο το φεγγαράκι ψεύτικη η ακρογια λιά ’, ‘ήταν που λέτε μια φορά όπου ’χαμ’ ένα βασι λιά ’, ‘φεγγάρια μου πα λιά ’, ‘κι ο Χάροντας σα φίδι τραβάει την κοπε λιά ’. Afterwards, Euripidakis creates a song that is a parody of Aeschylakis’ style, piecing together the saddest lyrics set to music by Theodorakis, and creating a macabre mishmash just as Euripides does for Aeschylus’ songs (1261 f.). Finally, placed on the scales Aeschylakis’ songs are proven literally to be heavier (see Fig. 2), as in the original (1365–1413):Footnote 54

Fig. 2. Spatharis’ shadow-puppets for Frogs. From left to right: Theodorakis, Karagiozis holding the scales, and Hadjidakis. Spathario Museum, by kind permission of Menia Spathari.

A more problematic case is that of the god Dionysus. He is replaced by the Minister Dionysus, who visits the underworld in search of the best composer, on the model of Dionysus seeking the best tragedian. Minister Dionysus is an ad hoc character that draws on the figure of the stock character Sior-Dionysios (or Nionios). Beyond the common name, this invented persona has nothing (in Aristophanic terms) Dionysian about him and nothing of the Nionios of shadow theatre, not even the characteristic Zakynthian accent with which the shadow-puppet is fundamentally linked. The merger of the god Dionysus with Nionios would have been much more artful, for both of them are characterized by bragging, despondency, coquetry and some feminine elegance; but as it is, Minister Dionysus remains an awkwardly severe presence during the show. The Dionysian core of Aristophanes’ play, as it has been well explored by Lada-Richards,Footnote 55 is thus eliminated through the omission of the following features: Dionysus’ cross-dressing, which rejects the Herculean exemplar (male vs female, 38 f.); the scatological element (man vs beast, 479 f.); and the very comic first episode, with the successive disguises and thrashing of Dionysus and Xanthias (god vs man, 494 f.). The elimination of the Dionysian core erases the highly metadramatic semiology of the play, but mostly – for we are no longer in his era, theatre, and genre – it omits potential scenes of abundant humour. Even if these omissions are partly imposed by the demand for shortening the duration of the performance, the marginalization of Dionysus as a dramatis persona can be attributed to the demand for the primacy of Karagiozis.

It is reasonable that we should now turn to the protagonist of shadow theatre. The debate over typologies of Aristophanes’ characters culminates in a discussion of the protagonists, for whom Whitman established the term ‘comic hero’ as a common type. Though his definition was not universally accepted owing to its focus on individualistic heroism, and although it certainly cannot be applied uncontroversially to all the comedies, it remains credible.Footnote 56 For our purpose, Whitman's comparison of the Aristophanic comic hero with Karagiozis is crucial: they are both poneroi (cunning), grotesque (mixing beast, man and divinity), eirones and/but alazones, immortal, great talkers, with a great plan, turning everything to their own advantage.Footnote 57 But given this perfect similarity of character and the fact that only one character can be the protagonist, in view of the dictates of heroic ‘individualism’, an issue of ‘comic primacy’ arises.Footnote 58

In older comic adaptations from other genres (Δον Ηλίας Κολοκύθας from the marionette theatre;Footnote 59 Γιατρός με το στανιό from Molière;Footnote 60 Ο Καραγκιόζης πλοίαρχος from the old chapbook Μυθολογικόν Συντίπα του φιλοσόφου;Footnote 61 Το καφενείο και ο φόνος του Ισραηλίτου or Ο Διάβολος κουμπάρος from Commedia dell'arte)Footnote 62 Karagiozis assumes the leading role, whereas in later adaptations, and mainly in the non-comic repertoire, Karagiozis almost always becomes a servant.Footnote 63 Following this more recent tradition, both of the Aristophanic adaptations present Karagiozis as a servant. Nevertheless, his comic primacy remains undoubted.

In Koutalou's Peace, Trygaeus has lost his leading and comic role. In quantitative terms (how much and often he speaks), he is clearly inferior to Karagiozis, who initially is just a companion on his journey. But also qualitatively, he has conceded every property of the comic hero to Karagiozis. In the following examples, Karagiozis has ‘stolen’ Trygaeus fluency and comic inspiration (1210–63):

Even the most dominant scene of riding the beetle has been ceded to Karagiozis. Throughout the show Trygaeus remains a colourless presence, with an awkward seriousness in his speech and movements. The same is true of Frogs: Karagiozis has assumed the role of Xanthias and upgraded it to a leading one (the inherent comicality of Xanthias, as precursor of the ‘clever slave’, favours this bridging); but whereas Xanthias leaves in the second half of the original play, here Karagiozis not only continues but exceeds Minister Dionysus, since it is he himself who weighs the two composers. The comic primacy of Karagiozis has been prepared from the beginning with Dionysus’ ‘de-comicalization’ and is established when he embarks on Charon's boat (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Spatharis’ shadow-puppets for Frogs: the frogs of the chorus were drawn en face in breach of the convention of Greek shadow theatre that figures are depicted in profile. From left to right: Karagiozis, Minister Dionysus (Nionios), and Charon in the boat. Spathario Museum, by kind permission of Menia Spathari.

Whereas in both of the adaptations I have examined there is an awkward displacement of the Aristophanic hero, another option (not taken) might have been a merger, i.e. Karagiozis as Trygaeus, Karagiozis as Dionysus and not as their companions.Footnote 64 This transcoding method would have been a more legitimate solution in preserving ‘individualistic heroism’: ‘by the loneliness of his search, the hero does what all must do, and thus becomes Everyman. But Everyman is the universal individual’.Footnote 65

The allocation of roles depends on the narrative functions imposed by the recipient genre, but most of all it depends on the requirements of the plot. In presenting a journey to Olympus (Peace) or to Hades (Frogs), both adaptations have a lot in common with the structure of Karagiozis’ travel adventures, a small but distinct group of plays.Footnote 66 We might say that Trygaeus’ lack of a beetle and Minister Dionysus’ lack of a composer correspond to the first function of Karagiozis’ comedies: the Pasha's lack of something. But in the latter case, the person in need never participates in the action, whereas Trygaeus and Minister Dionysus travel, accompanied by Karagiozis. As for the core function of ridiculing, despite being central to the adaptation of Frogs (as in the Aristophanic original) and exploiting common verbal devices, it is fundamentally different from the Karagiozic model. In traditional Greek shadow theatre, it is always Karagiozis who mocks the others; here, the agents of mockery are Aeschylakis and Euripidakis, each mocking the other.

*

Both Aristophanic comedy and Karagiozis are vivid components of modern Greek culture and identity. They have been theoretically compared by scholars and creatively combined by artists, thanks to their intriguing overlaps: gastronomy, fantasy, social and political satire, and above all the comic hero. When it comes to adapting the former art form into the latter, the main difficulties arise from the fact that Aristophanic comedy is very variable, and often quite anarchic, whereas Greek shadow theatre is highly codified, both in terms of technical conventions and in terms of content (plot, characters, imagery, language and ideology). It is in other words a genre, not simply a medium through which any kind of script or dramatized text can be adaptated unconditionally. Its codification, a product of its historical development and its traditional character, restricts the source-material but at the same time suggests transcription codes. Whereas obscenity is a constitutive element of Aristophanic humour, Karagiozis was gradually ‘purified’ and eventually ‘sanitized’ through a series of transcoding methods (mainly by channelling sexuality into gluttony), which can also be applied to the processing of Aristophanic obscenity.

However, despite this artistic potential, the case studies reveal that the decisions are principally determined by the audience and the medium: in these cases, by the requirements for decency in state television and radio. ‘Adaptation never happens inside an aesthetic vacuum, but inside ideologies and power structures that determine not merely the cultural value attributed to adaptation, but in many cases whether adaptations are possible at all.’Footnote 67 Another challenging aspect is the allocation of roles to the stock characters of Greek shadow theatre. In Koutalou's Peace Karagiozis is inserted into the plot, awkwardly supplanting Trygaeus as the protagonist. Pavrianos’ Frogs experiments with merging the Aristophanic and the Karagiozic characters on the basis of the compatibility between their characters. But again, Karagiozis (as Xanthias) displaces the Aristophanic protagonist, who becomes Minister Dionysus: neither an Aristophanic figure (the god Dionysus) nor a Karagiozic one (Sior-Dionysios or Nionios).

Such problems arise from the convention of Karagiozis’ ‘comic primacy’: only he can be the comic protagonist. And here again, as with obscenity, Aristophanic comedy has precisely the necessary minimum degree of overlap with Greek shadow theatre that enables its transcription, since Karagiozis is indeed a ‘comic hero’. If the ‘axiom of pleasure’ (that is the horizon of expectations of the audience) is an inviolable term in folk art, and if the Aristophanic layer is intended to be recognizable, then the dilemma of ‘codifying the anarchy’ (e.g. sanitizing Aristophanes’ obscenity) or ‘anarchizing the code’ (e.g. denying Karagiozis’ comic primacy) leads to an impasse. The solution seems to be the transcription of anarchy through the code, that is, the employment of Karagiozis as the Aristophanic protagonist (a merger) and the filtering of vulgarity through suggestive language and the use of sociolects, symbols, romance, and rampant gluttony.