With the notable exception of Equinor—the company known until very recently as Statoil—few businesses have been more iconic in Norwegian history than Christiania Glasmagasin, which today produces fine glass at Hadeland Glassverk and porcelain at Porsgrunds Porselænsfabrik. Though the company has a major online presence and at least forty-five outlets throughout the country, from Mandal in the south to Harstad in the north, its name remains almost uniquely identified with its majestic former emporium, finished with fine-grained gray-white Iddefjord granite in 1899, on the square in front of Oslo Cathedral (Figure 1). The store originated in 1776 as an outlet for Norwegian glassworks, itself a direct descendant of the Royal Norwegian Chartered Company established on May 21, 1739. The business has, of course, undergone remarkable transformations during its nearly three hundred years of continuous existence, but its core focus on producing glass has remained clear and, appropriately, offers a unique lens through which to analyze the relationship between public policy and private initiative at the origins of Norwegian industrialization and, more broadly, between the often divergent historiographical perspectives offered by business history, the history of capitalism, and the history of political economy.Footnote 1

Figure 1. Christiania Glasmagasin, Oslo, 1899. (Photographer unknown. Photo courtesy of the Oslo Museum, Oslo, Norway.)

Specifically, this article considers the company's founding, growth, and management in the nexus of economic theory, public policy, private investment, international emulation, and the environmental constraints that characterized eighteenth-century Denmark-Norway. Then, it addresses the surprising fact that the firm operated at a yearly loss from its very beginning until 1787, a period of almost fifty years. From the perspective of state capitalism, there are many reasons that it might make long-term sense to support unprofitable activities in order to nurture strategic industries, but why were private investors so patient over such a long period?Footnote 2 And what does this tell us about public-private partnerships and, more generally, the political economy of development in Enlightenment Norway? In addressing these questions, we begin to respond to Mary O'Sullivan's important call for more business historical research on the role and perception of profitability in the history of capitalism.Footnote 3 We will argue that investors endured their losses for so long—though not without voicing frustrations—for a number of reasons, including the hope that a monopoly might eventually be granted the company for the sale of glass in Denmark-Norway once it had proved it could meet the entire domestic demand for all kinds of relevant products. Another deciding factor was the prevalence of patriotic sentiments informing the need to establish industries in Norway at a time when the world was perceived to be divided between leading countries that exported manufactured goods, on the one hand, and colonial polities focused on raw materials, on the other. Investors, finally, were further able to bear sustained losses in the industry because, though large in absolute terms, they were nonetheless dwarfed by the vast profits generated by their share in the contemporary timber trade. Given these underlying explanations for investor patience, we will demonstrate how a changing political and intellectual climate in Norway—informed also by the world's first translation of Adam Smith's 1776 Wealth of Nations—led to shifting constellations of regulatory measures and ownership structures in the country's glassworks that eventually allowed the company to break even in 1787 and, in the early nineteenth century, to become an icon of the country's early industrialization.

Nature and Nurture

The Norwegian Company—which in 1887 would become Christiania Glasmagasin—was originally granted the privilege to exploit the country's enormous natural forest resource wealth in new ways and, more specifically, to transform its abundant raw materials into glass, furniture, weapons, charcoal, tar, and other manufactured goods that were not yet produced in the country.Footnote 4 This was a local expression of a broader movement of political economy observable throughout the European world that is often identified by such terms as “mercantilism,” “Colbertism,” and “Cameralism.” Though specific manifestations of this policy orientation were endlessly varied, it remains that early modern European writers and legislators on economic matters had increasingly come to emphasize the need for import substitution and export-led growth. As far as possible, legions of writers argued, and policymakers established, countries should seek to refine and use their raw materials domestically, because productivity gains in manufacturing allowed for greater domestic value addition and thus greater wealth creation in a world of competing states among which comparative power was progressively a reflection of relative prosperity.Footnote 5 In Denmark-Norway, this orientation of political economy (at the time identified explicitly with the originally Germanic tradition of Cameralism) gained new momentum as a result of the hard times that followed in the wake of the Great Northern War of 1700 to 1721.Footnote 6

According to Kommersekollegiet, or the Board of Trade, the governmental unit in charge of the economic policy and development of the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway, the new economic policy in favor of domestic manufacturing should be supported by “powerful means,” because in the face of more mature international competition, industrial activities would by necessity “perish” without active state support.Footnote 7 This movement was spearheaded particularly by the Danish Cameralist and bibliophile Otto Thott, who envisioned Denmark-Norway as an integrated economy in which flat and fertile Denmark would be the breadbasket while Norway, where “Climate and Nature themselves struggle against agriculture,” would focus on the ocean, timber, and minerals.Footnote 8 In line with the major contemporary writers on political economy in Europe, Thott warned against the example of Spain, weak and destitute amid all the abundant mineral wealth of the New World, and chided Norway, with all its natural riches—including “fisheries … the gold mine of the North”—for still having to import “even the most ordinary things.”Footnote 9 In order to secure employment, independence, and wealth, and therefore relative power in international relations, Denmark-Norway would increasingly have to add value to its raw materials domestically. To do this, “good Masters” ought to be invited to “teach” their skills to “locals,” so that, “with time,” they might spread around the country; an array of policies—from credit facilitation to outright prohibitions against competing foreign goods—should be implemented to encourage the development of domestic manufacturing.Footnote 10 The importation of glass, in particular, had “brought a great deal of money out of the country, particularly after the fire in Copenhagen,” a reference to the great 1728 fire in the Danish capital, its reconstruction still ongoing in 1735.Footnote 11 Given the inputs and resources necessary for a glass industry to flourish, however, Thott suggested that “there must be places that exist in Norway, where forests can be beneficially employed” for that purpose.Footnote 12

The company established to undertake these developments was originally owned by King Christian VI of the House of Oldenburg (1699–1746) and his family with 100 shares, Danish and German private investors with 771 shares, and a small group of Norwegians with 8 shares.Footnote 13 Many terms were in use at the time for describing such investors in Scandinavia, but most Norwegians would have made their fortunes as merchants or in the mining, fishing, and particularly timber sectors, at a time when northern forests essentially supplied the Dutch and British fleets with their most crucial raw materials.Footnote 14 These leading Norwegian businesspeople were known as “patricians” or, more colloquially and jokingly, “plank nobility” and, eventually, simply “capitalists.”Footnote 15 As Christen Henriksen Pram explained in 1811,

Under the denomination of Capitalists [Kapitalister] or Rentiers [Rentenerer], the last census gives a number of 650 families with 5607 individuals in both Kingdoms [of Denmark-Norway], but these are far from the only ones who own capital, who largely belong to other classes of people [Folkeklasser], as few wealthy people are only wealthy people …. Neither do they form their own class of humans [Menneskeklasse].Footnote 16

Compared with limited liability companies, the partnership constituting the Norwegian Company, or simply “the company,” was different in that each investor or “owner” was personally responsible for the company's activities, including any potential losses, in full.Footnote 17 In the 1740s, and in line with its broad initial spectrum of privileges, the company initiated a number of activities including the production of charcoal, tar, resin, potash, sodium nitrate, and bricks. It even operated an iron mine.Footnote 18 The company had at first been awarded a royal privilege to be the only producer of all kinds of glass, first in Norway and then also for the whole Kingdom of Denmark-Norway, but this industry initially represented only a minor part of its activities.Footnote 19 The founding document describes the company's mission in terms similar to those employed by Thott: “to allow the Company to establish Glassworks in the furthest distant Forests, from where Timber otherwise can be brought, or otherwise turned into money.”Footnote 20 The glass industry was explicitly championed as a means of valorizing Norway's natural resources, and particularly its vast forests. Attempts had repeatedly been made to establish a glass industry in Denmark in the past—around 1570, 1650, and 1690—but they had always failed for lack of a sustainable source of fuel. Norway's massive timber resources were seen as a solution to this problem, and just as abundant hydropower would facilitate the country's proper industrialization in the nineteenth century, so proximity to strategic raw materials justified the establishment of glassworks there in the eyes of the Danish government and of private investors alike.Footnote 21 Indeed, as the company's first director would write in a 1760 letter, at a time when numerous glassworks had been forced to close down across Europe for lack of access to fuel, in some places in Norway “forests are so abundant that 20 glassworks cannot consume them in infinite time.”Footnote 22 But glass manufacturing at the time required more than just fuel; it required sand and either potash—potassium carbonate derived from boiling ash—or sodium from kelp ash, all of which also were in abundant supply in Norway.Footnote 23 As a result, Norway saw two new glassworks opened in the 1740s. The first was the Nøstetangen glassworks in Hokksund, near Drammen (1741–1778), which was established to produce small amounts of various types of green glass. Later, in the 1750s, it developed to become a premier producer of fine crystal glass and other luxury products such as chandeliers.Footnote 24 Aas Green Glassworks (1748–1765) was set up a few years later to produce bottles and other green glass in Sandsvær, near the old mining center of Kongsberg. Each glassworks employed twenty-five to thirty workers, blowing glass twelve hours a day for five days a week.Footnote 25

Although the country was richly supplied with the necessary raw materials for glass production, technical know-how was sorely lacking in Denmark-Norway. Therefore, the company immediately embarked on a project of explicit emulation by engaging with European technical literature on glassmaking, attracting—as Thott had suggested—skilled workers from the continent and even pursuing industrial espionage (which got one Norwegian envoy, the company's future director Morten Wærn, arrested in London and held for a month); it was precisely the sort of diffusion of knowledge and expertise that historical centers of glassmaking from Venice to England had long sought to prohibit.Footnote 26 At the same time, many skilled workers made their way to Norway from the continent looking for jobs on their own accord, and emulation was manifestly both a top-down and a bottom-up process at the time.Footnote 27 Though his name is lost to time, the first “glass master” to arrive in Norway hailed from Thuringia and came to set up shop at Nøstetangen in the early 1740s.Footnote 28

Even with access to foreign expertise, abundant raw materials, and active governmental support, however, the first years of the company's history were far from profitable. The original partnership sold the company during the winter of 1750–1751 to a new group of investors, who subsequently reestablished it under new management. And though it remained a private-public partnership, the number of shareholders was markedly reduced. King Fredrik V (1723–1766) held 30 percent of the shares, and his close friend, advisor, and soon director of the Danish East India Company, Count Adam Gottlob Molkte, held 10 percent. The remaining shares were owned by private investors, including three Norwegians and the firm Anker & Wærn, representing two of Scandinavia's wealthiest families. The new director was Caspar Herman von Storm, a Norwegian military officer and book collector who had studied abroad and who also became the Amtsmann (governor) of Akershus county in 1757 and eventually superior governor of a region of six counties (Akershus stiftamt) in eastern Norway from 1763.Footnote 29

Market Segmentation and the Challenge of Solvency

Storm and the new owners had a strong vision for the future of the glass sector and initiated a plan to develop the industry so it would cover the demand for all types of glass for the Danish-Norwegian market. This new strategy revised the original 1739 plan entirely. Rather than ambitiously seeking to develop a large number of disparate industries related to Norway's natural resources, the company now focused its efforts solely on glass. From the very beginning, the company had served a very small, high-end market in this space. The king and his court represented the most important market for the glassworks, and as late as the 1750s, the royal wine cellar in Copenhagen was the largest single customer of the Norwegian glassworks, purchasing around one-third of its total production.Footnote 30 After the reconstruction, however, the company's general assembly stated in 1753 that its primary aim now was to serve all segments of the Danish-Norwegian market, and all social classes, with a much broader variety of glass products.Footnote 31 This basic idea found its practical expression in a bold plan to expand the industry by investing in new glassworks (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Map showing glassworks in the Kingdom of Denmark and Norway. (Map by Isabelle Lewis.)

This plan included a new glassworks in Hurdal (established in 1756) for the production of crown glass, which was window glass of high quality based on English and French technology acquired by explicit industrial espionage and produced by glassworkers from the two countries.Footnote 32 It also included a new glassworks in Biri (1766) for the production of fensterglass (cylinder glass), which was window glass of cruder technology produced mainly by glassworkers from Bohemia. In 1762, a glassworks in Hadeland was established for the production of bottles and other green glass, to replace the now closed glassworks at Aas. All of these glassworks were located within a radius of less than 150 kilometers from Christiania, which became Kristiania in 1877 and later, in 1925, Oslo (the original name the city had enjoyed from its medieval founding until the great fire of 1624).Footnote 33 Later in the eighteenth century, the company set up two additional glassworks for window panes, one in Hurum (known as Taxmaster Schimmelmann's glassworks from 1779), for the production of bottles, and one in Jevne, in Fåberg near Lillehammer (1792), for the production of taffelglass, which was window glass of a quality higher than fensterglass but lower than crown glass. What follows focuses primarily on the glass industry from the 1751 reconstruction to the end of the eighteenth century, when the frequently interventionist ideals of Cameralism gave way to more market-based solutions as guiding principles for the development and operation of the company. In particular, we will seek to relate the changing political economy of the period to actual business practices at the time.

Given eighteenth-century accounting norms, it is actually something of a puzzle to uncover a company's real annual profits and losses. What we do know is that the company technically went bankrupt in 1751, after twelve years of operation, and that the reconstructed company continued to lose money. To cover these losses, individual investors had to pay in proportion to the number of shares they held. Such personal outlays had to be borne repeatedly, not only to cover running losses but also to invest in new glassworks. And this situation led to debates among shareholders and stakeholders in the glass industry, both public and private, about how to better organize the company to turn the situation around and begin making profits. They discussed different organizational alternatives as well as different ownership structures, and their debates reveal different—and changing—views on the role of the state in developing new industries in eighteenth-century political economy.

In addition to the necessity of additional large investments for setting up new glassworks, the reconstructed firm also continued to suffer from cash flow problems and from structural difficulties inherent to the business itself. In order to serve the Dano-Norwegian market, for example, the company established warehouses in Copenhagen, in Denmark, and in Christiania and Drammen, in Norway.Footnote 34 In effect, a major challenge to the company's profitability, and one that would repeatedly cause its shareholders concern, related to its logistics at a time of still limited territorial marketization.Footnote 35 Most of the products were shipped 100 to 150 kilometers from the different glassworks out to the coast. Given the condition of infrastructure at the time, and particularly roads, transportation was easier during winter, when ice and snow cover both increased speed and reduced breakages, than during summer. The company calculated that 5 percent of all shipments broke in wintertime, compared with 12 to 20 percent during the snow-free months. In addition, the farmers who transported the finished glass products over land received lower wages in winter than in summer, when they had more to do. The Norwegian investor Carsten Anker, a member of the timber patriciate and future director of the Danish East India Company as well as one of Norway's founding fathers, investigated this personally, finding that farmers demanded 6 rigsdaler (Rd) to transport one hundred bottles from Hadeland to Christiania in summertime, compared to only 2 Rd during winter.Footnote 36 Once the glass had arrived safely at the coast, most of it was then shipped by sea from the ports of Drammen or Christiania to the warehouse in Copenhagen. While logistics by land were simpler during the winter months than during summer, however, the inverse was true at sea. Indeed, because of icing on the Oslo Fjord, the company's glass had to be stored in a warehouse in port until the March melting before it could be shipped to Copenhagen.

Transportation was thus costly and seasonally uneven, and the company's logistical bottlenecks caused severe problems, particularly during some periods from the late 1770s onward when the Norwegian glassworks experienced booms in demand. The organizational structure of having several glassworks and several warehouses also had consequences for the company's accounting practices and perception of profits and losses. From the main reports in the ledger, one could get the impression that the company was always profitable, since all the glass the company shipped from its glassworks toward its warehouses was defined and recorded as income at the expected price.Footnote 37 These reports say nothing about whether glass was broken during transport, or whether the warehouses in the end were able to sell any of it. Since most of the output from the glassworks produced in the 1750s and 1760s was not sold at all, there is a massive disparity between the balance presented in the company's central ledger and its real financial situation. In order to get an overview of the company's actual financial condition, we have therefore reconstructed a more complete picture of its real profits and losses by going through the day-to-day records of its warehouses and comparing, on an annual basis, the income from its actual market sales with the expenses that the glassworks reported (see Figure 3). Though we know that a minor part of the production was sold directly from the glassworks to local markets in rural Norway, and thus not reported as sales income through the warehouses, it is nonetheless evident that the operation never became profitable during the period under analysis. Because of the nature of the company's incorporation, and particularly its unlimited liability, this led to severe and ongoing yearly losses for shareholders.

Figure 3. Annual income from sales and reported expenses, Norwegian Glassworks 1751–1769. (Sources: Ledgers 1751–1760, 1767–1773, no. 3, Private archive no 1, National Archives, Oslo.)

Before the reconstruction, the company's first owners had invested a total of 56,000 Rd in stocks, which they lost when a new partnership bought the company in 1751. In addition, the company's debts at that time totaled 23,800 Rd. The contemporary Danish-Norwegian monetary system—divided between debased and sometimes banknote courants on the one hand and hard specie on the other—hailed from 1713, though its basic currency structure dated back to the Renaissance: 12 penning = 1 skilling; 16 skilling = 1 mark; 6 mark = 1 rigsdaler. The rigsdaler, or Rd, contained 4/37 of the silver content of a Cologne mark, or 25.28 grams of silver. For comparison, an urban male laborer in Copenhagen made about 3 marks a day, or half a rigsdaler.Footnote 38 The new owners paid 10,000 Rd for the company, and its remaining debt at the time was covered through a lottery in Denmark.Footnote 39 The new agreement stipulated that investors would remain jointly liable for the entirety of the company's debts. Furthermore, according to its bylaws, the company's general assembly—where one vote represented one share—could decide with “simple majority” that all shareholders had to contribute to cover the annual losses. If anyone refused, management was entitled to sell their respective shares at a public auction.Footnote 40

This agreement had major consequences for the shareholders. Between 1752 and 1771, the company's investors on average paid more than 12,000 Rd annually to cover losses.Footnote 41 The main reason for these losses was simply that the company failed to sell its products. In the 1750s, real income from sales represented between 0 and 17 percent of total production costs. In 1760, production costs were more than 22,000 Rd, while income from sales did not reach 3,500 Rd. As late as 1769, production costs were approximately 61,000 Rd, and income from sales only around 21,000 Rd. The value of the products stored in the company's warehouses was around 200,000 Rd, or three entire years’ worth of output from the Norwegian glassworks, representing two-thirds of the customs revenues from sound dues in Øresund levied on all foreign ships crossing the line between Helsingør and Helsingborg separating the North Sea from the Baltic—one of the most important sources of Danish Crown revenue.Footnote 42 The new and expansive state-led economic policy from the 1730s had assumed that new industrial activities would create their own demand. This did not happen as expected, however, and the state found itself forced to directly subsidize a number of the industries whose establishment it had encouraged.Footnote 43 In the case of the Norwegian glass industry, the king paid 35.5 percent of the costs necessary to keep the company running from 1739 to 1776.Footnote 44 As such, private investors bore the brunt of the costs of keeping the company solvent and operational in the initial decades of sustained losses.

Some scholars have argued that a dearth of private capital was the main constraint in the development of industrial activities in Norway in this period.Footnote 45 However, this does not seem to have been the case in the glass industry. On the contrary, the company expanded and established a number of new glassworks to enable the manufacture of a great variety of glass products precisely because private investors were willing to finance sustained losses. Year after year, decade after decade, they covered losses when management asked them to. Eventually, though, by the late 1760s, investors began to prove less willing to comply, and Anker's cousin James Collett and other members of the Christiania timber patriciate gave the company loans that later had to be repaid by the shareholders.Footnote 46 Earlier scholarship has claimed that the company's investors simply were not motivated by profit but rather contributed to the industrialization of Norway out of a sense of idealism or patriotism.Footnote 47 Though the investors’ motivations doubtlessly were multifaceted and complex, the company's archives nonetheless demonstrate the degree to which both management and investors indeed sought profitability for decades. In 1753, for example, the general manager, Storm, optimistically wrote that if they could only manage to recruit more skilled foreign workers, the company could “annually expect more than 1,000 Rd in profit.”Footnote 48 Similarly, economic arguments were frequently cited as the main reason the company ought not make any new investments or operational changes, such as replacing local wood with imported coal as the main energy source for the glassworks.Footnote 49

Because the company had difficulties in selling its products, one might ask why management did not try reducing prices in order to render their goods more competitive. Variations of this question were addressed broadly in contemporary economic debates in Denmark-Norway.Footnote 50 Even with a 6 percent tariff on imported glass, Norwegian substitutes were more expensive than foreign imports, and Storm believed a tariff of no less than 40 percent would be necessary to render them competitive.Footnote 51 Through the 1750s, he argued in effect that Norwegian glass should be more expensive because of higher local labor costs.Footnote 52 Indeed, wages seem to have absorbed a higher percentage of operating costs in Norwegian glassworks than in comparative establishments in continental Europe (see Figure 4). As would eventually become clear, however, structurally high production costs were a consequence of the spirit of emulation in which the company had been founded. As Morten Wærn wrote in 1772, the costs of production in the company depended entirely on the high wages that initially had been promised foreign workers, to convince them to move to rural Norway, and could not be mitigated “until the now remaining foreign workers have passed away.”Footnote 53 This is why the company, without additional state support, eventually invested in apprenticeship programs and, importantly, permanent vocational schools in several locations from the mid-to-late 1770s, teaching not only glassmaking but also mathematics, reading, writing, and religion. With some state support, the company even helped initiate a pension fund for workers.Footnote 54

Figure 4. Operating expenses by percentage of total, selected glassworks. (Sources: Rolv Petter Amdam, Tore Jørgen Hanisch, and Ingvold Pharo, Vel blåst! Christiania Glasmagasin og norsk glassindustri 1739–1989 [Oslo, 1989], 15 [slightly revised]; Warren C. Scoville, Capitalism and French Glassmaking, 1640–1789 [Berkeley, 1950], 15; Francesca Trivellato, “Guilds, Technology, and Economic Change in Early Modern Venice,” in S. R. Epstein and Maarten Prak, eds., Guilds, Innovation and the European Economy, 1400–1800 [Cambridge, UK, 2008], 199–231, esp. 227; Quentin R. Skrabec, Edward Drummond Libbey, American Glassmaker [Jefferson, NC, 2011], 9; Edward Beatty, Technology and the Search for Progress in Modern Mexico [Berkeley, 2015], 124.)

One reason that the company's management did not worry unduly about prices was that they expected the king to ban all glass imports to Denmark-Norway once the Norwegian glassworks had reached sufficient capacity to satisfy domestic demand in the two Kingdoms. Such a ban would also eliminate competition from foreign glassworks that had established a presence in the region before the Norwegian producers came online. For instance, representatives from companies in Bohemia had traveled around Denmark already in the seventeenth century to sell glass and had even established warehouses in Copenhagen.Footnote 55 As late as 1752, a Norwegian merchant was granted a royal privilege to sell German glass in the cathedral city of Trondheim.Footnote 56 As such, in addition to the more civilizational mission in which the investors were involved, they were also motivated by the expectation of future protection to continue production in the face of ongoing losses. And they had good reason to believe that such a restriction would eventually be introduced. A number of other products, including refined sugar, were protected by just such an import ban. In 1762, more than 130 products were banned from import to Denmark and more than 30 to both Denmark and Norway.Footnote 57 As mentioned, the precondition for being protected by an import ban was that the industry proved itself productive enough to meet Denmark-Norway's total demand. Only then might a ban on imports in the sector in question be considered.Footnote 58 And from the 1750s the domestic market for glass was growing. Where previously only elites had used glass drinking vessels, ever larger parts of society now embraced the custom; more wine was bottled and drunk by a wider array of people; window panes in houses became larger; and glass windows penetrated ever deeper into the countryside. Even farmers began to introduce glass windows in their barns, “so that the light, that has a great impact on the health of the livestock, is let in.”Footnote 59 Glass was, as such, quite evidently a growth industry in Denmark-Norway at the time, intimately connected not only to the extension of traditional husbandry but crucially to the expansion of consumerism and commercial society there in the second half of the eighteenth century.Footnote 60

The expansion of the glass industry was implemented according to plan. More than discussing prices, what mattered for the company was building as many glassworks as were necessary to produce all kinds of glass, in order to convince the king that they could indeed cover the entire market for such goods. For instance, a frequent exchange of letters in the late 1750s between Storm and Adam Gottlob Moltke, who represented the king, did not reflect any concerns about whether a ban would be decided, but instead focused on the progress of the glass industry's development and on when it would be able to meet all domestic demand for glass products so that a ban could be implemented.Footnote 61 In numerous letters, Storm also assured investors that the expansion was going well and that the king would soon be pleased with the company's progress and finalize the import ban, thus finally allowing the company to break even and then rapidly become profitable.Footnote 62 The king's long-established economic policy with regard to protecting new industries as soon as they had proven that they could meet the demands of the domestic markets thus gave the impression of a credible commitment that created expectations for future profit among the investors in Norwegian glassworks. This, in turn, facilitated their decision to continue facing losses year after year.Footnote 63

Beyond the question of the profitability of the business, merchants in Copenhagen complained about the quality of the goods produced by the Norwegian glassworks. This view was supported by the customs service that in 1766 stated that too many bottles were “of too poor quality to be transported with wine on long journeys.”Footnote 64 Moltke, who, in line with contemporary principles of governance, was chiefly concerned with the “common good,” noted that while six thousand bottles were sent to Copenhagen in 1757, the problem was that “many bottles were too big, some too small, yes, the design is not accurate.”Footnote 65 And Storm claimed that the mismatch between supply and demand was what kept postponing the import ban. He therefore sent Wærn, then a member of the board of managers, to Copenhagen in 1759 to convince Moltke that “a proper supply of Norwegian glass would never be lacking in Copenhagen.”Footnote 66 Many in the imperial capital nonetheless held that the Norwegian glassworks produced too many unmarketable products. At the same time that some glass products were stored and not sold, there was a high demand for products that were not stocked in the company's warehouses.Footnote 67 Nonetheless, the much anticipated ban on imports was finally institutionalized in 1760, at a time when the Norwegian glassworks were still clearly unable to meet domestic demand. This is evident from the fact that the company was allowed to import fifteen hundred chests with cylinder glass from Pomerania only two months after the ban was established.Footnote 68 Indeed, the company, as well as glass masters, wine shops, and pharmacies, was occasionally allowed to import glass to meet demand throughout the subsequent decade, in spite of the ban.Footnote 69

The company faced a dilemma well known to the historiography of planned and command economies. Unable to single-handedly master the forces of supply and demand, it ended up producing too many of some products and too few of others.Footnote 70 Particularly in the 1750s, when economic policy pushed for the expansion of the glass industry, management developed plans to meet the whole spectrum of plausible Dano-Norwegian demand for glass. This proved easier said than done. Regarding window panes, for example, Storm thought that what the market wanted was expensive and high-quality crown glass rather than what he maintained was lower-quality cylinder glass, or fensterglass.Footnote 71 On their end, it turned out, domestic consumers largely demanded German fensterglass. And as unsold crown glass piled up in the company's warehouses, the government was forced to allow the import of German fensterglass to meet demand. Admitting to his mistake, and proverbially reading the market better, Storm ultimately decided to invest in a new, dedicated glassworks at Biri, near Gjøvik, to produce fensterglass domestically.Footnote 72

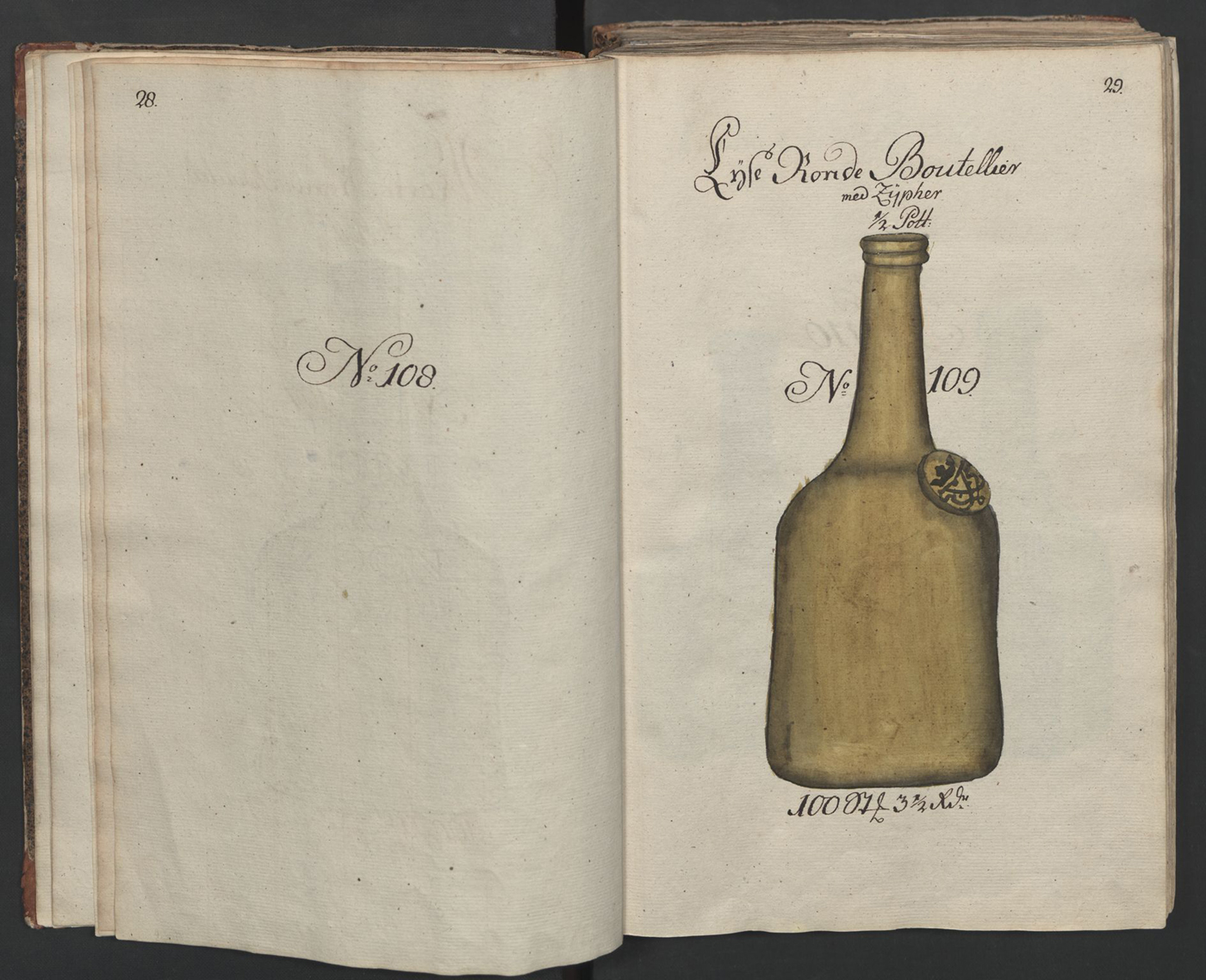

As an institution, the monopoly provided the company with challenges as well as opportunities. The obligation to produce all kinds of glass was particularly demanding. Not only did the company commit itself to being able to produce all types of glass products, but it also had to ensure that the warehouses of all major cities in Denmark-Norway were stocked with the full catalog of goods. Furthermore, the company promised to, in the future, supply “all models and kind of glass that may be invented.”Footnote 73 This idea of producing and storing all kinds of glass at all times was expressed visually in a 1763 catalog that the company commissioned from the Danish engraver Ip Olufsen Weyse, a hand-colored register illustrating more than six hundred products ranging from small drinking glasses to bottles and window panes (Figure 5).Footnote 74 These were the products that the company promised to produce and store in order to be rewarded the import ban. If we consider the logistical challenges the company faced in getting products to markets as a result of its geography of operations, not to mention those relating to climate and changing seasons, this beautiful catalog exemplifies the most important institutional constraint on the monopoly in the period.

Figure 5. Hand-colored manuscript catalog of models and prices for glass products from the glassworks at Nøstetangen and Aas, 1763. (Courtesy of the National Archives of Norway, Oslo.)

Resentment and Reform

Undoubtedly, the government's policy attracted investments in the glass industry and helped keep the dream of profitability alive among investors, despite the yearly losses. As it turned out, however, even the 1760 import ban did not inaugurate an era of profits for the company—and yet shareholders continued to invest in new glassworks and to cover running losses. In the 1760s, this could continue because of changing management strategies. While investors were asked to cover transparent losses on a yearly basis through the 1750s, shareholders were asked only late in the decade to cover the company's yearly losses for the 1760s.Footnote 75 This is because Storm and Jacob Benzon, the new general director after 1767, personally provided the capital for some of the investments and for all of the losses every year in the form of loans to the company. The other shareholders, unaware of the arrangement, eventually complained that the situation had not been discussed in the general assembly.Footnote 76 Investors were finally asked in 1767 to repay the loans to cover losses for the previous years, when the market expanded and Benzon in cooperation with the customs service made a critical survey of the company, including the conditions at all glassworks. The last relatively large glassworks, in Biri, had been inaugurated the previous year, and Benzon concluded that the critical years were over and the company would finally be able to meet demand for the most popular products moving forward.Footnote 77 However, this assessment would again prove too optimistic, and as the company continued to fail to break even, investors finally began losing confidence. A crisis was at hand.

While glass production in Norway increased in the 1760s, it dropped again in the early 1770s. From a production value of 61,000 Rd in 1769, it fell to 35,000 Rd in 1776.Footnote 78 Several glassworks had to close or suspend operations, among them the new fenster glassworks in Biri, for most of 1772, and Hadeland for the production of bottles from January 1772 to June 1776. This was extremely costly, since the company continued to pay the salaries of the workers, who were all first-generation immigrants whom management feared would leave the country if not paid.Footnote 79 The crisis was partly financial, as it was harder to raise money to cover operational losses, but also organizational. More specifically, management was weak during the period, unable to negotiate between different factions regarding how the company should be run to achieve profitability. One alternative was to let private investors take over the glass industry entirely, letting it sink or swim in accordance with market forces, consumer preferences, and simpler economic incentives; another was for the king to increase his shares and solidify a state ownership of the company.

Shares were split in the early 1770s, and in 1771 there were twenty-four shareholders in addition to the king.Footnote 80 The two largest private investors were Benzon, the current manager, with 17.5 percent and Storm, the previous manager, with 10 percent. According to the company's bylaws, all shareholders had to pay to cover losses or make further investments if the general assembly voted in favor of it. As mentioned, it was, in principle, possible to auction off the shares of noncompliant shareholders, but management seems to have thought it better to work for consensus than to threaten any such auction explicitly. After all, there was a danger that no one would bid on the shares in question, and this would reveal and make public the real underlying value of the company. The company's organizational structure and regulations were, in other words, poorly suited to raising new capital in cases where the majority of shareholders were not in favor of it. As mentioned, management had been able—although against growing opposition—to convince the company's shareholders to pay the debt through the 1760s, but the situation changed around 1770. Shareholders waited ever longer after the decision had been made in the general assembly to pay their debts, and they frequently complained that management did not listen to the other shareholders.Footnote 81 Votes in the general assembly were no longer unanimous, and in the face of mounting pressure, Benzon eventually resigned as manager of the company. A new management team, consisting of Wærn, who years earlier had embarked on a journey of industrial espionage for the company, and Court Junker Stockflett, was appointed in 1770 but was soon replaced by another team, made up of Bailiff Søren Hagerup and Chief Magistrate Fredrik Wilhelmsen. This latter team would go on to manage the company during subsequent years of crises.Footnote 82

In this situation of continuing losses and growing distrust of management, a group of Norwegian private investors made a radical offer that represented an alternative model to that under which the company had operated since its incorporation. In short, they wished to move the focus of the company's strategy from economic self-sufficiency, fully supplying the domestic Dano-Norwegian market with every kind of glass product, to a clearer rationality based on profits. The ownership structure could remain, but the individual glassworks would be made more independent under leaseholder agreements and given an explicit mandate to be profitable. And, crucially, their lessee administrators were to be incentivized by the promise of a share of any eventual profits for the company at large. The offer was made in 1770, when Kay Brandt offered to lease the glassworks of both Hadeland, of which he was the administrator, and Biri. Brandt had been in the company since 1747 and knew the industry well. His offer was accepted, and he was allowed to lease the two glassworks for ten and six years, respectively. He was not alone in such an undertaking, however; indeed, he was one of five Norwegian investors who sought to change the business model at the time. Another was David Bolt, manager of Hurdal glassworks, who, similarly, was allowed to lease it with the backing of Benzon, who at that time had just stepped down as director of the company, and two of the richest merchants in Christiania: James Collett, who had provided crucial loans to the company in the 1760s, and the forest owner and timber merchant Bernt Anker, at that time Norway's wealthiest man.Footnote 83 Through these leases, most of the risk would be transferred from the company to individual investors and entrepreneurs who believed in the industry. According to the contract, both the skilled labor force and the royal privilege would remain. In return, leaseholders had to commit to maintaining the glassworks and keeping them in operation, as well as to paying the company 1,400 Rd annually per glassworks, close to the value of 8 percent of the company's total shares.Footnote 84 The Norwegian Company remained as a sales organization and continued to set prices for glass goods at its warehouses. However, leaseholders could influence their returns by selling directly from the glassworks instead of shipping their output to one of the company's warehouses. While the company paid 30 Rd for each shipment of one thousand small bottles from Hadeland to Christiania, for example, Brandt was able to sell the same bottles for 35 Rd to local customers.Footnote 85 In this vein, he recruited a network of sixteen agents in Norway and nine in Denmark to sell straight from the glassworks rather than through the central warehouses.Footnote 86 Needless to say, these strategies challenged the government's original ambitions for the planning and regulation of the glass industry in fundamental ways.

Even with his best efforts, however, Brandt did not manage to make the Hadeland and Biri glassworks profitable. He proved unable to raise the necessary capital to continue operations and, faced with debt and unable to pay his workers, was forced to give up his contract with the company.Footnote 87 Bolt and his co-investors who had leased the Hurdal glassworks were more successful.Footnote 88 On the one hand, this was because of his much wealthier financiers, who gladly bankrolled operations of the glassworks; on the other, Bolt had decided to abandon the company's long-held views on prices, cutting them by 25 percent in an attempt to increase demand and achieve economies of scale.Footnote 89 Carsten Anker, who at that time represented the government's interests in the Norwegian glass industry, frowned upon Bolt's new strategy, as it ultimately would benefit the leaseholder as a private individual. Had the reduction in prices benefited the company as such, it might have been acceptable, Anker opined, but not if it favored an outside leaseholder “with no knowledge whatsoever of economic and physical matters.”Footnote 90

And even if Hurdal seemed to perform better than before, its main investor, Bernt Anker, was not happy. His investment had also been motivated by profit, and he had considered “this contract a straightforward lease contract”—an investment with a certain possibility of profit. Yet, instead of profits, he found an utter mess for which no one in the company was willing to take responsibility. One director, Wærn, wanted to leave the company, and another director, Court Junker Stockflett was “as paralyzed as a dead man.” And behind them, Bernt Anker wrote, sat the previous manager, Storm, “who orchestrates the company.” Furthermore, Anker criticized the company for not handing over the old stock of glass to the leaseholders, as agreed in the contract.Footnote 91 He eventually lost patience and, in December 1774, made an offer to acquire the whole company with all glassworks, including the privilege, and its stock of glass for 70,000 Rd. The offer would imply a complete reorganization of the company and dramatically weaken the role of the state in the industry. Eleven shareholders met to discuss the bid at the company's general assembly on December 10, 1774. No one opposed it on principle. Several suggested that the bid should be 10,000 to 30,000 Rd higher. Among them was Brandt but he also expressed his thankfulness to Anker for “thus lifting the interested parties out of this interminable aggravation—which had cost him [Brandt] all of his welfare.” or the chaos, in short, that had cost Brandt his fortune.Footnote 92 Ultimately, it would be the Dano-Norwegian tax authority that would have to accept the bid for privatization. Instead of doing so, however, it offered a counter bid for the whole company. On behalf of the king, the government now wished to buy all the shares in the company for 400 Rd each, which was 37.5 Rd, or 8.6 percent, lower than Anker's offer. The alternative being offered to those investors who were unwilling to sell was to pay 200 Rd per share—that is, half the offered share price—to finance the continuing operation of the company. In the face of such pressure, most private investors decided to sell to the king, and by 1776, only Carsten Anker, Nils Tank, and James Collett remained as private owners, the king having increased his ownership stake to nearly 82 percent, or 139 of 160 shares.Footnote 93

One may well ask why the state did not accept Bernt Anker's offer. Principally, as one of its representatives explained at the 1776 general assembly, it was because there was “good reason to fear that the individual's intention only was to realize [sell off] the company's stock of glass and then close all the glassworks down.”Footnote 94 Pursuing what it understood to be the public rather than private interest, the state maintained that Denmark-Norway benefited from a glass sector to satisfy internal demand for imports, provide rural employment, build domestic expertise, and valorize natural resources that otherwise were exported raw. The positive externalities of the glassworks, in this vision, compensated for their running losses. As Carsten Anker later reflected, the state had acquired the majority of shares in the company “in order to avoid the closure of the company, and to maintain industriousness in the country, which was more important to the State than the yearly loss of operations were for the Royal Treasury.”Footnote 95

That said, it is not evident that Bernt Anker and his group of investors had really been interested in closing the glassworks down. They had made clear that they disagreed with the principle that national considerations should trump profitability and, as such, had more faith in the glass industry than in the government's management of it. As one of them had argued at the 1774 general assembly, the different glassworks would benefit from being organized as independent units, “which can be done best by Private Owners.”Footnote 96 The private shareholders, in short, regarded the existing organizational form of the company and the industry as a constraint hindering profitability, while the government regarded it as a safeguard for the principle of serving the common interest by making Denmark and Norway self-sufficient with glass and promoting industrialization. This was an important theoretical debate in the European world at the time, which only would intensify in the coming decades, but which in this case found practical expression at the intersection of economic policy and business practice.

By the time the investors sold their shares to the king for 400 Rd in 1776, each share had cost them, on average, 1,580 Rd.Footnote 97 In the aftermath of the royal bid, all of the company's glassworks were put under the management of a new government entity called the Norwegian Manufacturing Administration. In addition to the glassworks, the manufacturing administration managed other activities such as the cobalt mine and blue color works at Modum, better known as Blaafarveværket, which at its height in the 1830s and 1840s would provide no less than 80 percent of the global supply of blue coloring.Footnote 98 Carsten Anker, still a private investor, became the director of the glassworks unit within this new organization. The acquisition might be seen as symptomatic of the government's attempts to resist the rise of more market-oriented principles of political economy at the time, but, as it were, the new government administration itself undertook precisely such measures in its continuing quest for not only national strategic interests and the proverbial common good but also seemingly ever elusive profitability.

In this, the government's approach to political economy was also shaped by a boom in demand for glass that began around the time of the king's nearly complete nationalization of the company in 1776. The growth was dramatic, and sales that year were more than five times what they had been in 1769. Indeed, demand increased so fast that Norwegian glassworks were unable to meet it during the boom from 1776 to 1781, and the glass master guild in Copenhagen complained about the difficulties in securing enough glass.Footnote 99 The increasing demand was caused mostly by a thriving construction industry, partly in reaction to the disastrous explosion of Copenhagen's gun powder magazine on March 31, 1779, when a very large number of window panes were broken throughout the city.Footnote 100

The complaints arose primarily in Copenhagen, naturally, because Denmark was by far the largest market for Norwegian glass. From 1767 to 1773, only 35 percent of the company's output was sold in Norway, while 3 percent was exported to Hamburg, Amsterdam, Riga, Danzig, and Saint Petersburg. The remaining 62 percent was sold in Denmark. Considering the longer period from 1766 to 1791, no less than 75 percent of all Norwegian glass was sold in Denmark and, from there, in its colonies. Although Denmark is rarely considered from an imperial perspective in the historiography of early modern Europe, it nonetheless enjoyed colonial possessions in Asia, Africa, and the West Indies that influenced its foreign policy, economic strategies, and popular culture alike (Figure 6).Footnote 101 Indeed, a significant proportion of Norwegian glass bottles (as high as 18 percent) were filled with wine for export to the Danish colony in Tranquebar, India, now Tharangambadi.Footnote 102 Within Norway, Christiania represented the largest share of sales in the period from 1767 from 1773, with 36 percent, followed by Bergen and Trondheim (both 13 percent), Drammen (11 percent), Fredrikshald (now Halden) (5 percent), and finally other cities (15 percent) and local sales at the glassworks (7 percent).Footnote 103

Figure 6. Map of overseas possessions of the Danish and Norwegian Empire. (Map by Isabelle Lewis.)

The company's failure to meet demand during the boom in the late 1770s precipitated a new debate about the import ban. Carsten Anker remained deeply skeptical of the idea of opening the Dano-Norwegian market again, because he doubted Norwegian glass would be able to compete with foreign imports in terms of both “quality and price.” Rather than letting “the public” feel the difference, and thus eventually “complain” in the future, Anker thought it better to let people “avoid the suffering.”Footnote 104 The alternative was to expand domestic production by establishing new glassworks. Several possible locations were discussed, including as far north as North Trøndelag, and the Norwegian Manufacturing Administration made plans for further expansion in 1778.Footnote 105 As a result, Taxmaster Schimmelmann's glassworks opened in Hurum in 1781, principally to produce bottles. This new enterprise revealed shifting investor motives, especially with regard to the localization of the glassworks. As mentioned, all the earlier glassworks had been located far from the sea but close to forests, in order to make easy use of local natural resources necessary for the production of glass, particularly wood for fuel. Now, however, in a period of increasing demand, the speed of transportation to Copenhagen became the primary economic and logistical obstacle for the company. In hindsight at the time, even Carsten Anker admitted that locating the glassworks far from the sea had been “the most important … of the many and significant mistakes made in the establishment of the Norwegian glassworks.”Footnote 106 According to Anker's new plan, Biri glassworks would be closed and its production moved to Hurum, which was closer to the sea. And from Hurdal, similarly, crown glass production was to be moved to a new glassworks—also nearer to the coast—dedicated to the production of fensterglass and crown glass, as well as bottles, which were the company's most market-sensitive products.Footnote 107 This last idea was not implemented. To compensate for the lack of wood in Hurum, production was originally to be based on imported coal, and earlier skepticism that production based on coal would be too expensive—not to mention counterproductive to the original idea of valorizing domestic raw materials—had seemingly lost out in the calculus of costs.Footnote 108 Such a coal-fueled glassworks was in effect put in operation in Hurum in 1784, but it soon proved to be a failure. The quality of the glass was poor, and production costs were higher than expected. Most importantly, the boom years were coming to an end. While Norwegian glassworks sold bottles for 72,000 Rd in 1781, three years later the sales value had sunk to 32,000 Rd. The stock of glass grew again, and longer transport times would no longer be a problem for the company until the next boom, this time for window glass, emerged in the early 1790s. The glassworks in Hurum was then reopened, only to be shuttered yet again once that boom, too, ended.Footnote 109 The entrepreneurs and investors in the Norwegian glassworks learned the costs of organizing according to fluctuating market demands the hard way. Further attempts at running that specific glassworks were abandoned, and when the next boom in demand for Norwegian glass began in 1803, a new wood-fueled glassworks inland at Jevne, close to Lillehammer, had been established and made a more sustainable contribution to the industry.Footnote 110

Visible and Invisible Hands

The first translation of The Wealth of Nations was into Danish. In 1779, only three years after the original publication of Adam Smith's masterpiece, the book was officially translated and published in Copenhagen.Footnote 111 The majority of the translation's subscribers were Norwegian, and several key persons in the glass administration were among those who initiated and supported the translation.Footnote 112 The book was translated by Frants Dræby, who had been private tutor for Collet's family in Christiania. He had been persuaded to complete it by Carsten Anker and Andreas Holt, who both had met Smith in Glasgow during their Grand Tour.Footnote 113 Smith had personally recorded the meeting in their diary of the journey, in an entry from May 20, 1762:

I shall always be happy to hear of the welfare and prosperity of three Gentlemen in whose Conversation I have had so much pleasure, as in that of the two Messrs. Ancher and of their worthy Tutor, Mr Holt.Footnote 114

At that time, Holt and Anker were two of the four members on the board of the Norwegian Manufacturing Administration, and it is worth asking, after having seen the direct influence of Thott's ideas on the founding of the Norwegian glass industry, whether Smith's ideas similarly might have influenced the sector and its administration in the later eighteenth century.

From an organizational standpoint, the state had never been more active in managing the glassworks than in the years following 1776. The glassworks were run by a state-owned company from 1776 until 1782, when they were incorporated in a new partnership called Handels- and kanalkompaniet (The Trade and Canal Company), with a majority of private shareholders. The new company was built on a similar vision to the one that had inspired the Norwegian Company in 1737, namely, to exploit the country's natural resources. Now, however, those resources included the new Eider Canal (also known as the Schleswig-Holstein Canal) connecting the North Sea to the Baltic. The partnership was to run a variety of commercial and industrial activities in Denmark-Norway at the time, including the glassworks, but it had no commercial success. In 1784, the glassworks unit demerged from the company, to be run as a state-owned enterprise until 1824.Footnote 115 Already in 1794, however, the state leased out the glassworks again, this time to Hans Wexels, an experienced manager who had replaced Carsten Anker as director of the glass industry in the Norwegian Manufacturing Administration in 1781 and then had been made general director of the glass industry in The Trade and Canal Company. In 1794, Wexels leased the glassworks for a period of fifteen years at an annual rate of 8,000 Rd.Footnote 116

Though the state had strengthened its position in the glass industry in many ways since its incipience, this period of state ownership and private leaseholding would witness the introduction of more liberal regulatory reforms and, for the first time in half a century of operations, a turn to profitability as operations became more efficient. If the company continued to post yearly losses during the first decade or so following the king's 1776 takeover, it could finally report total profits of 3,479 Rd in 1787, no less than forty-eight years after it was incorporated.Footnote 117 This state of affairs would continue uninterrupted for the next fifteen years.Footnote 118 Partly, the company's sudden profitability was simply the consequence of a technical operation that essentially spun off the old stock of unsold glass as a separate entity that would sell directly to markets during periods of high demand, thus removing the value of this inventory from the original company's accounts.Footnote 119 At the same time, other operational factors contributed to the turnaround. A commission managed by the Danish entomologist Johan Zoëga was given a mandate to introduce more cost-efficient methods in the glass industry in emulation of successful foreign practices, “such as in the German glassworks.”Footnote 120 The commission further suggested that salaries, which had been comparatively high in Norway following wage inflation during the boom years, were to be reduced. As a result, following yearly wage increases of 20 to 40 percent in the period between 1776 and 1783, salaries were now cut by around 50 percent.Footnote 121 The costs of some raw materials were similarly reduced, while at the same time, glass prices increased—by 10 to 20 percent in 1783 alone.Footnote 122

No less importantly, the company's obligation to produce all types of glass at any one time to ensure the domestic supply of Denmark-Norway, a principle that private investors had long fought against, now came under attack again. In 1772, Wærn had argued that it was impossible to be profitable as long as the company had to maintain a full stock in so many different cities. His proposal had been to maintain only two warehouses in Norway, in Christiania and Drammen, and to allow customers to order from the central catalog and from advertisements.Footnote 123 But nothing happened. Indeed, the company further committed itself to also maintaining a warehouse in Copenhagen of such a size that it could cover the full demand for glass throughout all of Denmark in 1781.Footnote 124 Only in 1787 would the much-protested institutional constraint of keeping warehouses with stocks of all kinds of glass be abolished. According to Wexels, who argued strongly for this reform, the management of the glass industry ought to be given “the freedom to organize the operation according to the demand.”Footnote 125 The final change came after the previously mentioned 1787 commission had made a new plan for the glass industry. The commission argued that the vast array of different glass products that had to be stored should be reduced to a more manageable number.Footnote 126 Thus, when Wexels began his period as leaseholder in 1794, he could start almost from scratch with an industry now liberated from some of the most arduous regulatory constraints that had shaped the first half-century of its existence.

Not surprisingly, this new situation of yearly profits, growth, and gradual liberalization attracted several interested investors. Among them was, again, Carsten Anker, who already had made a bid on the entire company on behalf of a group in 1787. There were also several competitors to Wexels's 1793 bid to lease the glassworks.Footnote 127 Yet, the king still did not sell. Why not? The Danish finance minister Ernst H. Schimmelmann had suggested an explanation in 1787:

It is beyond all doubt that, if the glassworks could be sold with safety for the capital and the continuing manufacture for the country's needs, then it would from all perspectives be much more advantageous than either leasing them or trying to run them on your majesty's account.Footnote 128

As long as domestic production would continue, in other words, the state wanted to sell the glassworks—it just found the offers too low. In effect, Wexels had a paragraph included in his contract that decreed he could indeed buy the glassworks if the parties could agree on a price. But beyond the question of price and the company's underlying value, there was a second, regulatory concern that made a sale difficult. From the late 1780s, the state was increasingly looking to liberalize the industry to encourage its international competitiveness, while potential buyers were insisting on maintaining the old privileges and, crucially, the relative ban on glass imports from 1760.

When the glass company management had negotiated for the import ban in 1760, then-director Storm had already feared that they might be accused of pursuing monopolistic privileges and that they would be associated with “that hated name of monopolium.”Footnote 129 In practice, of course, this was what the industry was awarded, and though more economically liberal ideas had driven the private investors interested in acquiring the glassworks from the late 1760s, the tables had turned as the glassworks became profitable in the late 1780s. Now it was the state that wanted a more liberal regulatory regime, perhaps even under the influence of Smith's recently translated Wealth of Nations, while private interests essentially resurrected Thott's old arguments for imposing stronger protections for the industry. No less ironically, one of the primary champions of liberalization at the time was the glass masters’ guild in Copenhagen. It officially criticized the glass industry in 1788, claiming that the quality of the company's goods was poor because of its monopolistic privileges. Additionally, as evident from the fine foods and wines they consumed, it was argued that the industry's management lived a life of luxury and corruption because of the rents they were extracting from an overly regulated market. The managers, a representative of the guild bewailed, had gotten their jobs through powerful friends—“from poor people they grew to become capitalists, while the country always has losses.”Footnote 130 If only privileges were abolished, the guild maintained, the price of glass would fall, benefiting both exports and domestic consumers.Footnote 131 Regulators listened, and beginning in the late 1780s, the salaries of the glass industry's managers were explicitly linked to the company's profitability, to the point that they would be reduced if it failed to turn a profit. Not only that, but, in accordance with the 1787 committee's recommendation, the two directors Wexels and Peter Hersleb Essendrop both had their fixed salaries cut. In exchange, they were given incentives to perform, with a promise of 20 percent of all profits as well as a bonus of 1,500 Rd if profits exceeded 3,000 Rd.Footnote 132

Far from an idiosyncrasy of the glass industry, these reforms were expressions of the state's comprehensive new vision of economic policy, according to which, in the face of the high costs of subsidies and the increasing challenge of smuggling, the state partly felt forced to liberalize as a means of improving its financial situation.Footnote 133 This process of liberalization had been planned by the Department of the Treasury for many years. In 1787, the Board of Trade had argued that if the state were to sell the glassworks, it should also have the right to abolish the industry's protective privileges.Footnote 134 And, when a new period of leasing out the glassworks began in 1793, the state initiated a debate on how “to achieve the liberation of manufactures and trade.”Footnote 135 The new lease agreement for the period from 1793 to 1808 stated that privileges to produce glass would be abolished after ten years, import restrictions on window panes after three years, and on other types of glass after ten years, which meant that for the last five years of the contract, the Dano-Norwegian glass industry would operate on a principle of essentially free international competition. The monopoly was abolished in 1804, after which imports were allowed and competing glassworks were built in Norway.Footnote 136 The purpose of this gradual experiment was, explicitly, “to thus achieve, on the basis of experience, certainty about whether the glassworks can exist on their own in the future.”Footnote 137 The transition to a more “liberal” political economy was, in other words, not something pushed for by private interests, at least not in this case, but rather something carefully planned for by the state once the industry had at long last achieved profitability. Indeed, reinforcing the Fabian nature of these reforms, the leaseholder received financial support to prepare for the gradual exposure to international competition in the form of 8 percent production subsidies.Footnote 138

Of course, this is not to say that new ideas about political economy had not penetrated the state apparatus—far from it. As contemporary debates in the National Board of Trade made clear, questions of economic principles were frequently debated at the highest levels of government. A 1794 intervention explained the case plainly: “Manufacturers who can experience progress in the face of competition with foreign factories are far more secure, and build on far firmer ground, than those who are shielded by uncertain prohibitions.”Footnote 139 The new orientation of political economy was, in short, both intellectual and practical in nature. But while the government increasingly argued for more liberal principles in the 1790s, private interests in the business continued to resist the changing policy orientation. After all, as Smith wrote about such matters, “people of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.”Footnote 140 Though the phrase is frequently taken to indict all sorts of businesspeople, its first, Danish translation gives a more specific contemporary reading of Smith's term: “manual laborers of a Guild [haandværks-Folk af eet Laug] seldom come together even to pass time and enjoy themselves without their gathering ending in a conspiracy against the public [Sammenrottelse mod Publikum] or some contrivance to raise prices.”Footnote 141 Conspiracies, in short, were a problem of guilds, not the pastime of capitalists, investors, and entrepreneurs. Nonetheless, Carsten Anker fought against liberal reforms in the sector when he proposed to acquire the whole glass industry in 1787, and when restrictions on imports gradually began to be abolished in 1803, the leaseholder Wexels similarly sought to stop the process as best he could. His experiences as a leaseholder, Wexels argued, proved that “these [glass]works are even less able than certain other manufactures to compete with foreign glass factories without help, either in the form of premiums for production and export, or through prohibitions against the importation of certain kinds of foreign glass.” Not only that, but why should Denmark-Norway unilaterally liberalize at a time when the great powers of the age continued to protect their own domestic glass industries? France, after all, still banned glass imports, and England maintained an export premium of 22 percent.Footnote 142 And English observers were all too happy to note that the old patterns of trade with Denmark-Norway continued: “what we import being materials, and our exports manufactured goods.”Footnote 143

The consequences of the reforms would be dramatic, Wexels warned, and indeed they were. In this and other ways, the early nineteenth century inaugurated a new and very different chapter in the history of the Norwegian glass industry. First, the sector was exposed to international competition in 1804; then Denmark became an export market following Norwegian independence in 1814; and finally, the state sold its shares to private investors in 1824. The foundational era of one of Norway's most iconic industries was then over, and the company faced new challenges as it continued its tumultuous journey toward the present. The final privatization of the company was debated at length in the Norwegian Parliament. Carsten Anker, then director of the state glassworks and grand old man of the industry, was called upon to advise on the matter in 1821. The parliamentary committee continued to consider the industry in light of the larger economy of the country, arguing, for example, that in spite of losses, “one should not fail to draw attention to the fact that the operation of the [glass]works has prevented the loss that would have arisen had one retired all their employees and workers.”Footnote 144 But Anker himself was reported to have drawn “a historical account of their state since their establishment,” arguing for the necessity of their privatization given present conditions. Though he did not mention Smith's Wealth of Nations by name in his speech, his debts to the book that he had helped translate decades earlier were clear as crystal.Footnote 145 Not only were private entrepreneurs and investors incentivized by their personal stakes in the business to work harder and be more successful than salaried state managers, but the committee also echoed Anker's warning in Parliament about continuing state ownership:

the State thus becomes manufacturer as well as merchant with these products—something which is to be advised against from a number of perspectives; first of which is that any manufacture is a branch of industry that almost belongs to private [interests], and which the State should seek to promote, but not itself become involved in, except in the case of the greatest need.Footnote 146

Parliament approved the sale, with eleven votes against, but voted unanimously that the glassworks should be “run at the State's expense” until a high enough price was reached. As it happened, Carsten Anker would not live to see that day. He passed away while inspecting the Biri glassworks in 1824, shortly before the industry that he so profoundly influenced was privatized.Footnote 147

The Political Economy of Business Enterprise

The Norwegian Company, later Christiania Glasmagasin, represents one of the country's first and, eventually, most successful stories of industrialization. It bridged the so-called industrious and industrial revolutions, and, simultaneously a symptom and a driver of an emerging culture of consumption, it expanded hand in hand with what contemporaries called “commercial society” in Norway.Footnote 148 Neither wholly private nor entirely public, the company was the product of Dano-Norwegian political economy at the time and could not have succeeded without the skill and resilience of private enterprise, on the one hand, or public protection and policy, on the other. At the same time, its origins and history were deeply shaped by the unique political—and, crucially, environmental—conditions of Denmark-Norway: by the climate, geography, and particular confluence of natural resources found there. And the complex dynamics of the Norwegian Company offer a remarkable example of how traditional historiographical dichotomies between planning and laissez-faire fail to reflect the complexity of the historical record.Footnote 149 Private entrepreneurship and management were necessary for the company's founding, but the agency of its regulation remained resolutely state-centered, whether during the period of monopoly and prohibitions or that of free international competition. Liberal reforms were not forced on a weakening Leviathan state by strengthened private interests freed from the fetters of regulation—quite the opposite. The business never existed outside of the sphere of regulation.Footnote 150

From this perspective, the question remains as to why private investors proved willing to sustain high yearly losses for almost half a century. At first glance, it is hard to ignore that the scenario presented by the eighteenth-century Norwegian glassworks jibes poorly with long-influential theories about entrepreneurs, investment, and indeed capitalism itself. By most current understandings of the concept, the investors in the Norwegian glassworks were not “maximizing shareholder value”—certainly not in the short, medium, or, by the measure of contemporary life expectancies, long or even very long terms.Footnote 151 Even accepting that for decades they expected an import ban that might eventually make the company profitable, it remains that—given that the median age of death in Norway was less than forty years in 1770—Dano-Norwegian glass investors literally accepted more than a lifetime of losses.Footnote 152 Because it was an unlimited liability company, it is hard to argue that the investors were not aware of the losses either, or, for that matter, were really ignorant of the true financial situation they were in. The yearly nature of their payments to cover losses means that they either willingly took the losses or were, for lack of a better term, utterly incompetent. The latter explanation seems unsatisfactory given what we know of some of the investors and how they made fortunes in other sectors, and this itself may be part of the key. Though 12,000 Rd in yearly losses was a veritable fortune in Denmark-Norway at the time, corresponding to the value of almost 8,500 barrels of cheap beer in Copenhagen, or two million bricks, it paled in comparison to the wealth that contemporary investors had accumulated in the timber trade.Footnote 153 When Carsten Anker's cousin Bernt Anker, himself an investor in the glassworks from the 1770s onward, died as Norway's wealthiest man in 1805, his fortune was estimated at 1.5 million Rd.Footnote 154 It may also be that, as the state itself did, investors approached the losses in this particular industry as acceptable because of positive externalities for other sectors in which they were involved—in Carsten Anker's case, perhaps most evidently the East India Company, which, as we saw, absorbed considerable quantities of glass bottles for wine export to the small Danish colony of Tranquebar. However, a full picture of the shareholders’ financial activities may be beyond what the surviving documentary evidence can supply; in any case, it is worth remembering that, historically, corporations were frequently understood to have a wider set of duties and responsibilities than mere profit maximization.Footnote 155 The dream of profitability surely kept the glassworks going. Even so, there may also have been nonfinancial reasons for the shareholders’ willingness to shoulder losses.