Poverty reduction [is] at the top of the global agenda [and has] reshaped policy priorities, galvanizing the attention and interest of governments, international organizations, the private sector, and individuals … We are in search of a truly global partnership for development [where] “convergence” must be an overarching principle. At the same time, we need to allow for differences in the pace and rhythm of getting there.

—Pascal Lamy, former director-general of the World Trade OrganizationFootnote 1Tackling grand challenges like poverty, climate change, modern slavery, political instability—and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic—has required, and continues to require, sustained collaborative efforts from an array of diverse stakeholders (George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi, & Tihanyi, Reference George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi and Tihanyi2016). Toward this end, private, state, and transnational actors like the United Nations (UN), the World Bank, the International Labour Organization, and the World Health Organization (WHO) have set overarching goals and launched programs aimed at tackling such challenges, ranging from the Sustainable Development Goals to the Paris Agreement and COVAX.Footnote 2 As a result of these initiatives, stakeholder practices have advanced considerably, with numerous novel and sophisticated arrangements for mobilizing multiple actors toward a common goal (Abbott, Reference Abbott2012, Reference Abbott2013; Hargrave, Reference Hargrave2009; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010).

Stakeholder theory, on the other hand, has arguably not kept sufficient pace in examining the dynamics of these stakeholder arrangements that organize around issues rather than firms. We attribute this to implicit conceptual premises in existing accounts: firm–stakeholder relationships are represented through the image of either a “hub-and-spoke” wheel—that is, a collection of dyadic interactions (Freeman, Reference Freeman1984; Mitchell, Agle, & Wood, Reference Mitchell, Agle and Wood1997)—or a “web,” where the firm is a central node within a larger stakeholder network (Rowley, Reference Rowley1997; Werhane, Reference Werhane and Phillips2011). Although not without their contributions, such images contain considerable limitations for understanding how multiple stakeholders coordinate around grand challenges. For one, organization–stakeholder ties and the overall network structure are in a dynamic and co-constitutive relationship: for instance, as firms learn about and adapt to changing stakeholder demands (Girard & Sobczak, Reference Girard and Sobczak2012), those relationships are likely to evolve, with incremental changes accumulating into substantive transformations of the entire structure (Bothello & Salles-Djelic, Reference Bothello and Salles-Djelic2018). Furthermore, these perspectives do not adequately capture other important characteristics of stakeholder systems, such as the functions or roles of different actors, the emergent properties of stakeholders organizing together, or the teleology (i.e., aims and goals) of the overall arrangement. To wit, dyadic- and network-based images are not geared toward viewing the whole as more than the sum of its stakeholder parts.

We propose, therefore, that to understand how actors address grand challenges, we require a novel conceptualization of firms and their stakeholders as stakeholder systems. We derive the term from general systems theory (von Bertalanffy, Reference von Bertalanffy1968), a perspective that views social systems as comprising interrelated and interdependent components that function together as a cohesive whole. This conceptualization is suited for both detailed scrutiny of relationships and holistic views of the whole system (von Bertalanffy, Reference von Bertalanffy1972); in other areas of management literature, the systems view has been highly useful in helping us understand phenomena like interorganizational relationships, managerial goals, and organizational structure (Kast & Rosenzweig, Reference Kast and Rosenzweig1972; Shipilov & Gawer, Reference Shipilov and Gawer2020; Van de Ven, Reference Van de Ven1975), but also more directly business sustainability (Bansal, Grewatsch, & Sharma, Reference Bansal, Grewatsch and Sharma2021).

Thus far, however, a systems-level perspective in stakeholder research has been surprisingly absent, despite a more recent renewed interest in organizational systems theory more broadly (Adner, Reference Adner2017; Shipilov & Gawer, Reference Shipilov and Gawer2020). The sparse handful of accounts that we do have are often limited to a cursory observation that firms and their stakeholders are interdependent (Schilling, Reference Schilling2000; Werhane, Reference Werhane2008, Reference Werhane and Phillips2011). We therefore have yet to explore other, equally important implications of stakeholder behavior within a systems perspective, such as teleology (i.e., the articulated goals or problems driving action) or the narratives that collectively drive actors toward a common goal. Importantly, we have yet to flesh out fully the potential of a systems view to conceptualize simultaneously the dynamic interactions between interorganizational relationships (Kilduff & Brass, Reference Kilduff and Brass2010) and the overall stakeholder collective (Welcomer, Cochran, Rands, & Haggerty, Reference Welcomer, Cochran, Rands and Haggerty2003). Our goal in this piece is to take an explanatory approach to theorizing (Cornelissen, Höllerer, & Seidl, Reference Cornelissen, Höllerer and Seidl2021) and “establish the fundamental processes and structures that ‘underlie’ and therefore explain” (6) the dynamics of stakeholder systems.

We therefore seek to advance a stakeholder systems view using reasoning by metaphor (Cornelissen, Reference Cornelissen2005, Reference Cornelissen2006), drawing insights from ballet choreography. We argue that stakeholders in a system and around a focal organization behave as dancers on a stage: despite having their own roles, functions, and purposes, the actors are interdependent and coordinate to produce a performance (Harrison & Rouse, Reference Harrison and Rouse2014). In addition, as with other systems, ballet performances comprise properties like teleology, interdependence, and storytelling; as such, they contain elements that are absent from competing dyad- and network-based accounts. Our metaphor thereby provides the basis for a “semantic leap” (Cornelissen, Reference Cornelissen2006: 1584) that generates new ways of making sense of organizations and their contexts by drawing parallels with other phenomena (Cornelissen, Reference Cornelissen2005; Ketokivi, Mantere, & Cornelissen, Reference Ketokivi, Mantere and Cornelissen2017).

In our case, we propose that ballet (the source domain) is useful for analyzing and explaining how firms and stakeholders respond to grand challenges (the target domain) in a manner that other metaphors do not sufficiently capture. The focus of dance on “acting, watching and feeling more than verbalizing and listening” (Hanna, Reference Hanna1987: 18) therefore offers fertile terrain for novel conceptualizations requiring action, aesthetics, timing, and dynamism, especially in management studies, where theorization is mainly drawn from language-based metaphors (Bitektine, Haack, Bothello, & Mair, Reference Bitektine, Haack, Bothello and Mair2019). Dance therefore offers a rich context for theorizing about how organizations and stakeholders coordinate, especially in light of grand challenges.

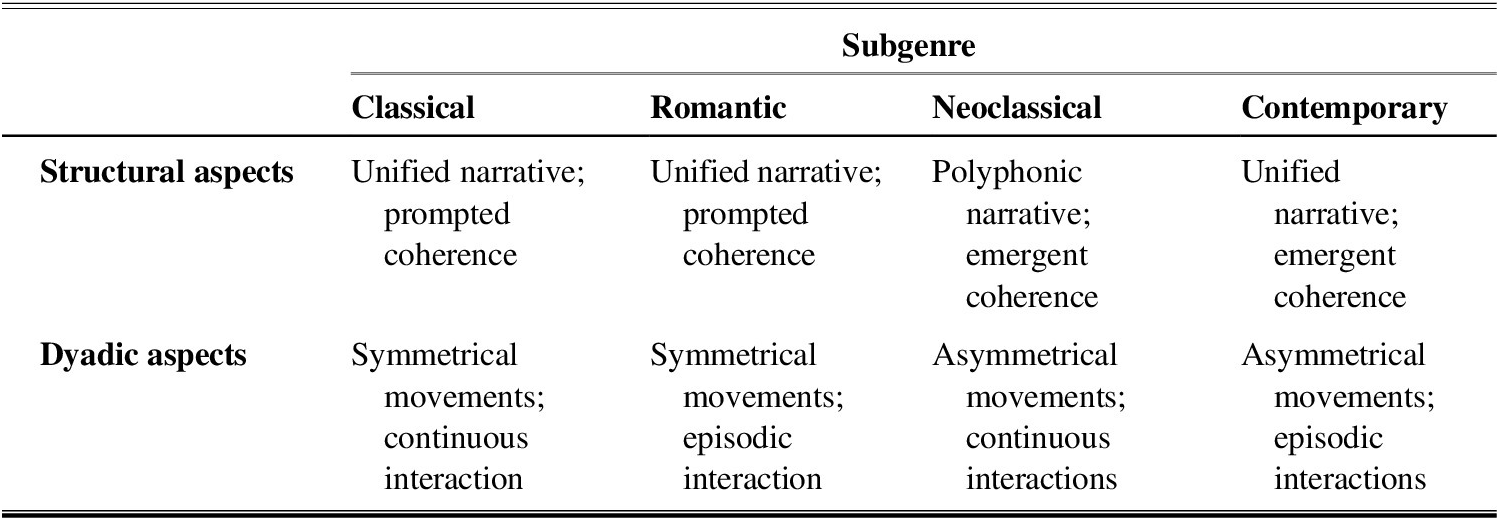

To inform our metaphor, we select seven iconic ballet performances from four subgenres: classical (Swan Lake, The Nutcracker), Romantic (La Sylphide, Giselle), neoclassical (Apollo) and contemporary (Clytemnestra, Isadora). We use dance theory—a framework used by choreographers to produce choreographies and partner interactions that are both harmonious and meaningful (Biehl, Reference Biehl2017; Daly, Reference Daly1994; Hanna, Reference Hanna1987; Kolo, Reference Kolo2015)—to define four axes that capture major points of choreographic variance. In doing so, we also capture some fundamental ways stakeholder interactions and arrangements coevolve. Two axes (narrative and coherence) are based on ensemble distinctions across our sample of ballets and therefore reflect characteristics at the level of the stakeholder collective. The remaining two (interactions and balance) reflect relational characteristics between the principal dancer and partners and therefore parallel firm–stakeholder dyadic ties. Aside from allowing a discussion of how the two levels are co-constitutive (Archer, Reference Archer1995; Barley & Tolbert, Reference Barley and Tolbert1997), these characteristics generate insight regarding the evolution of stakeholder systems over time.

The rest of the article proceeds as follows: we first take stock of how stakeholder theory has moved beyond the limits of dyadic interactions (Margolis & Walsh, Reference Margolis and Walsh2003) but also highlight the constraints of recent network-based accounts. We then outline the advantages of a stakeholder systems approach, as well as the merits of ballet as a metaphor. We proceed to expose the specific cultural objects under study: seven ballets across four types of choreographic styles, using dance theory as a bridge between the domain of origin (ballet) and the target domain (stakeholder theory). Consequently, we develop our metaphor and flesh out the characteristics of stakeholder systems. We then use this framework to theorize some dynamics of stakeholder systems, proposing two paths along which a system might evolve. Finally, we discuss how ballet and a stakeholder systems view bring a unique perspective to stakeholder management, especially in addressing grand challenges.

STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS: THE RELEVANCE OF STAKEHOLDER SYSTEMS

The “Hub-and-Spoke” Metaphor: Early Dyadic Perspectives

Stakeholders are defined as groups or individuals that have a direct or indirect relationship (whether based on interest, interdependence, or power) with a focal actor, generally the firm. Initially formalized through the seminal work of Freeman (Reference Freeman1984; see also Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar, & De Colle, Reference Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar and De Colle2010; Freeman, Harrison, & Zyglidopoulos, Reference Freeman, Harrison and Zyglidopoulos2018), early perspectives on stakeholders sought to identify and catalog the major groups of actors that could affect (or be affected by) a firm—for example, customers, employees, suppliers, the media, or governments. This understanding consisted of a “hub-and-spoke” image of ties between the focal firm and stakeholders that was, by construction, dyadic. Subsequent research elaborated on this metaphor, highlighting how, for instance, two actors within the same stakeholder group could potentially have different relationships with the focal firm (Bridoux & Stoelhort, Reference Bridoux and Stoelhorst2014; Shymko & Roulet, Reference Shymko and Roulet2017). Instead of simply defining which stakeholders “counted” (Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2015), management theorists focused on the characteristics that made them salient to a focal actor (Mitchell, Agle, & Wood, Reference Mitchell, Agle and Wood1997; Neville, Bell, & Whitwell, Reference Neville, Bell and Whitwell2011).

Since then, stakeholder theorists have sought to reveal how firms may most effectively react to the pressures they face from stakeholders (Frooman, Reference Frooman1999). For example, instrumental stakeholder theorists propose that organizations build a “relational ethics strategy” that is based on either communal relationships or more transactional- and market-oriented exchanges (Bridoux & Stoelhorst, Reference Bridoux and Stoelhorst2016; Jones, Harrison, & Felps, Reference Jones, Harrison and Felps2018). Both perspectives have implications for where the firm should position itself in its relationship with its constituents for efficient stakeholder management but are still, at their core, based on Freeman’s hub-and-spoke image. The perspectives subsequently fall short in considering how stakeholders connect with or through each other, independently from their link with the focal firm. As Rowley (Reference Rowley1997: 890) notes, “each firm faces a different set of stakeholders, which aggregate into a unique pattern of behavior.” Accordingly, more recent contributions have proposed an alternate metaphor of a “web” (Welcomer et al., Reference Welcomer, Cochran, Rands and Haggerty2003), in other words, a network reconceptualization of stakeholder arrangements.

The “Web” Metaphor of Networks: Conceptual Merits and Limitations

Network research emphasizes the importance of going beyond dyads (Burt, Kilduff, & Tasselli, Reference Burt, Kilduff and Tasselli2013; Kilduff & Brass, Reference Kilduff and Brass2010; Tasselli & Caimo, Reference Tasselli and Caimo2019) based on two observations of stakeholder behavior: 1) the influences of different stakeholders over a focal actor necessarily overlap and interact with each other (Frooman, Reference Frooman1999) and 2) the salience of a stakeholder to a focal organization is not necessarily direct because intermediary parties mediate the relationship with and among stakeholders (Neville et al., Reference Neville, Bell and Whitwell2011; Roulet, Reference Roulet2020). Network characteristics like social capital (Cots, Reference Cots2011; Okazaki, Plangger, Roulet, & Menéndez, Reference Okazaki, Plangger, Roulet and Menéndez2020) are therefore important considerations for understanding stakeholder arrangements: Rowley (Reference Rowley1997), for instance, proposes that the density of the stakeholder network surrounding an organization leads to increased pressure while the organization’s centrality enables more resistance to this pressure. The network perspective therefore offers important explanatory power: Hein, Jankovic, Feng, Farel, Yune, and Yannou (Reference Hein, Jankovic, Feng, Farel, Yune and Yannou2017), for example, consider how organizational goals are potentially achieved not only through resource provision and exchange between the firm and stakeholders but also through facilitating exchanges among stakeholders themselves.

However, while a network image has proven generative for understanding stakeholders as part of a broader web, there are numerous conceptual shortcomings, in particular with capturing the dynamism of stakeholder arrangements. This omission is important for multiple reasons. First, dyadic relationships and structure are interrelated and coevolve. Bothello and Mehrpouya (Reference Bothello and Mehrpouya2018), for instance, illustrate how one intermediary actor shapes the field of urban sustainable development through its dyadic relationships with standard-setters, which carries implications for all other actors within the field. Second, the trajectory of coevolution of dyad and structure may be underpinned by teleological factors that are not captured by a network view, for instance, when actors coalesce to deal with larger problems. In an illustrative case, Haas (Reference Haas1989) shows how cleanup of pollution in the Mediterranean occurred through epistemic communities where actors were, in many cases, disconnected from each other. Third, a network perspective is not geared toward conceptualizing temporal dynamics with stakeholders, such as rhythm and pace, for instance, the frequency of firm announcements to stakeholders or the timing of environmental investments (Bowen, Johnson, Shevlin, & Shores, Reference Bowen, Johnson, Shevlin and Shores1992; Nehrt, Reference Nehrt1996). Fourth, and crucially, understanding network characteristics does not aid in assessing the appropriateness of how stakeholders coordinate to achieve a goal.

These conceptual constraints inhibit exploration of many recent empirical phenomena, especially around how stakeholders coalesce around addressing grand challenges (George et al., Reference George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi and Tihanyi2016). For instance, multistakeholder initiatives (MSIs) like the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil, the Forest Stewardship Council, or the Marine Stewardship Council are constructed around a specific environmental problem and involve a variety of parties that coordinate to collectively create responsible behavior (Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012; Moog, Spicer, & Böhm, Reference Moog, Spicer and Böhm2015). Members of such initiatives are considered stakeholders of an issue rather than of an organization (Saffer, Reference Saffer2019). Yet, in focusing on nodes and ties, a network perspective contains certain blind spots: the moral legitimacy of MSIs, for instance, is treated as the outcome of stakeholders being tightly or loosely coupled to each other (Rasche, Reference Rasche2012), when legitimacy may in fact serve as an antecedent to rather than a consequence of network structure.

These omissions therefore require a different perspective on stakeholder arrangements. A revised conceptualization would ideally retain the strengths of the network view in analyzing the structural arrangement of stakeholders while also incorporating the analytical depth of studying dyadic links. It would also potentially shift away from reifying the organization as the focal actor and instead consider how social actors act as a collective toward solving a social issue (Werhane, Reference Werhane and Phillips2011). We propose that the most promising path is to extend recent work on system perspectives in organization studies (Shipilov & Gawer, Reference Shipilov and Gawer2020).

Developing a Stakeholder Systems Perspective

In his classic treatise Metaphysics, Aristotle (Reference Sachs1999: 8.6: 1045a) discusses how entities are often formed with properties that extend beyond a simple aggregation of individual parts. Von Bertalanffy (Reference von Bertalanffy1950: 417) formalized this simple idea into systems theory, defining a system as “a set of elements standing in interrelation among themselves and with the environment.” He initially applied his insights to account for the functions of biological organisms before extending them to other forms of systems as diverse as computer programs, traffic flows, and economies. The premises of systems theory were particularly useful for explaining organizational and managerial phenomena (Kast & Rosenzweig, Reference Kast and Rosenzweig1972; Parsons, Reference Parsons1951; von Bertalanffy, Reference von Bertalanffy1972), culminating in chaos theory and complexity theory (Allen, Maguire, & McKelvey, Reference Allen, Maguire and McKelvey2011; Anderson, Reference Anderson1999; Anderson, Meyer, Eisenhardt, Carley, & Pettigrew, Reference Anderson, Meyer, Eisenhardt, Carley and Pettigrew1999).

Organizational systems can be understood as arrangements of actors that have purposes but are nonetheless interrelated, coordinating internally and adapting to their environment to achieve a central goal (Lai & Huili Lin, Reference Lai, Huili Lin, Scott and Lewis2017). Beyond organizations, systems thinking has also produced important contributions for business ethics, for example, by “circumvent[ing] what often appear to be intractable problems created by systemic constraints for which no individual appears to be responsible” (Werhane, Reference Werhane2002: 33) and by decentering stakeholder analysis (Werhane, Reference Werhane and Phillips2011).

Importantly, systems thinking is versatile enough to consider collectives of actors at different levels of analysis from the dyad to the entire system—as well as the subsets in between (Kast & Rosenzweig, Reference Kast and Rosenzweig1972; Werhane, Reference Werhane2002). As a consequence (and in contrast to the stakeholder network view), a stakeholder systems perspective considers existing interorganizational arrangements as more than just a set of firm–stakeholder relationships. Systems are by nature adaptive (Werhane, Reference Werhane2008) and therefore have the conceptual bandwidth to simultaneously examine the dynamic properties of both dyadic ties and the overall structure, as well as the recursive relationship between the two.

We define the term stakeholder system as a set of actors who perform various roles and functions but collectively mobilize toward the achievement of a larger social goal.Footnote 3 A systems approach acknowledges the interplay between dyadic ties and overall structure, enabling us to explore the dynamic of this interplay and consider effectiveness across different levels. In considering both components simultaneously, we can also theorize about how the two aspects coevolve. Conceptual and methodological limitations have thus far prevented such an examination, despite stakeholder theory being key to understanding the challenges faced by organizations and society (Margolis & Walsh, Reference Margolis and Walsh2003).

Considering the abstract nature of stakeholder systems and the potentially limitless number of variables that could be considered to understand them, we turn toward the use of metaphors to select key dimensions. We do not aim at being exhaustive but rather use those dimensions to illustrate the value of a stakeholder systems approach. Metaphors offer some flexibility in our thinking because of the “plurality and openness in meaning” and interpretation they enable (Cornelissen, Reference Cornelissen2005: 753). Standard theory building largely draws on metaphors from natural and social sciences, as well as from the humanities, with some of the most valuable contributions coming from powerful parallels with the performance arts (Biehl, Reference Biehl2017). Thus we propose that examining the rich artistic material of ballet choreography—through the lens of dance theory—can reinvigorate accounts of stakeholder engagement.

BALLET CHOREOGRAPHY, DANCE THEORY, AND STAKEHOLDERS

Motivating the Metaphor of Dance and Ballet Choreography

Given the diversity of systems that exist (von Bertalanffy, Reference von Bertalanffy1968), a stakeholder systems view requires a specific metaphor for us to demonstrate its generative value. As such, we proceed to explore the potential of dance—and ballet choreographies more specifically—to fill that role. Dance has already been used to explain organizational phenomena: Harrison and Rouse (Reference Harrison and Rouse2014), for instance, explore how creativity and elastic coordination occur in modern dance groups. With respect to stakeholder dynamics, scholars have drawn passing parallels to dance. The interaction between parties has, for example, been labeled as a “tango” (Kraan, Hendriksen, van Hoof, van Leeuwen, & Jouanneau, Reference Kraan, Hendriksen, van Hoof, van Leeuwen and Jouanneau2014; Tasselli & Caimo, Reference Tasselli and Caimo2019): in tandem with stakeholders, the focal organization coordinates and aligns action to produce a form of collective performance.

We propose that this metaphor has the potential to extend stakeholder theory for multiple reasons. First, dance contains temporal patterns, such as pacing and rhythm, that may be highly relevant for understanding how firms and stakeholders interact (Barnett, Reference Barnett2007; Bowen et al., Reference Bowen, Johnson, Shevlin and Shores1992). As Hanna (Reference Hanna1987: 30) observes, dance has a “motor” comprising elements like accent (stress/intensity), duration (length of time for movements), meter (grouping of beats/accents), and tempo (rate or speed of sequential movements). Another key distinguishing feature is that choreography is a system where action is purposive and purposeful rather than routine: Kurath (Reference Kurath1960: 234) notes that “out of ordinary motor activities, dance selects, heightens or subdues.” Third, dance contains a judgment of aesthetic value that complements the conventional focus on economic value in stakeholder studies (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Harrison and Zyglidopoulos2018): the quality and competence of a dance must be determined by some referent group, which allows for inclusion of norms and values around what stakeholder actions can be considered appropriate. In a broad sense, then, choreography informs the coordination of actors in social and physical spaces (Harrison & Rouse, Reference Harrison and Rouse2014; Kolo, Reference Kolo2015), thereby offering a fruitful domain of inspiration.

Ballet specifically is a rich metaphor compared with other forms of dance for generating new conjectures on the dynamics underlying stakeholder systems: the aesthetic value is based on dyadic dependence between dancers—the dance of one individual is affected by and affects the movement of others—as well as an overall choreographic arrangement (Hanna, Reference Hanna1987). More pragmatically, given its cultural hegemony in the West, the various subgenres of ballet have, for better or worse, been explored in dance studies more extensively than other forms, such as swing or hip-hop. With ballet, we are therefore furnished with conceptual and empirical material to distinguish highly diverse formats and rules—or lack thereof (Anderson, Reference Anderson2018)—which allows us to contribute to stakeholder theory.

The implications for understanding the dyadic relationships between actors and the dynamic of the system as a whole are not captured by other social systems—even those in the arts. For instance, orchestras may provide insight into characteristics like harmony and tempo, but how one performer is expected to play is largely predefined, with few dyadic exchanges among musicians and no spatial separations. By contrast, choreography acknowledges that the spatial positions of actors and their actions are relational to others’ and that this apparatus as a whole is what produces aesthetic value. In this sense, ballet offers a “representation that form[s] approximations of the target subject under consideration and that subsequently provide[s] the groundwork for extended theorizing” (Cornelissen, Reference Cornelissen2006: 1579).

Dance Theory as a Bridge between the Ballet Metaphor and Stakeholder Theory

Our metaphor (Cornelissen, Reference Cornelissen2005, Reference Cornelissen2006) enables us to characterize the dynamics experienced by systems of stakeholders and the dimensions across which those systems can be compared and understood. The material of ballet choreography provides a unique source that can be transferred toward the target domain of stakeholder theory, thereby enabling a dialogue between dance choreographies and stakeholder theorizing. We propose that dance theory (Hanna, Reference Hanna1987) acts as a bridge, facilitating interpretation of the first domain and its application to the second. Specifically, dance theory allows us to interpret and characterize a variety of ballet choreographies, applying those characteristics to understand stakeholder systems.

Dance theory is the body of frameworks to codify, produce, and interpret dance performances (Hanna, Reference Hanna1987). In other terms, it is a “frame of reference” composed of “the laws, forms and power structure” that give sense to those performances, specifically the articulation between bodily movements, space, and narrative (Brandstetter, Reference Brandstetter2014: 199). Yet, dance theory also emphasizes as much “fluid[ity] and open[ness] in our thinking as possible” (Burt, Reference Burt2000: 130); there is therefore no formal theorization as we understand it in the field of management, with hypotheses or propositions. Hanna (Reference Hanna1987: 187) refers to dance theory as an assessment of aesthetic value, or the appropriateness of what is staged when it involves interpreting characteristics of performances, of what makes them remarkable, and of what connects them. As new concepts and aesthetics have emerged, giving rise to new ways of rendering artistic performances, the evaluation and new ways of appreciating them evolve in parallel, whether for public audiences, architects, or performers (Brandstetter, Reference Brandstetter2014) Nonetheless, dance theory, despite its differences with theorization in other fields, is not only for dance scholars but also targeted at creating a “discursive context” around the dancing praxis (Burt, Reference Burt2000: 125). It thus serves as a way to label a material practice in order to better understand it, reproduce it, and apprehend it in its broader social context.

Dance theory has been used outside the field of cultural production and has found many applications in management science, business, and organization studies. Among the most important contributions, the work of Biehl (Reference Biehl2017) explores the power of dance theory to derive takeaways for collaboration or unpack relational leadership. A significant body of work bringing together dance theory and organization explores questions of individual embodiment (e.g., Slutskaya & De Cock, Reference Slutskaya and De Cock2008). Other pieces explore group interactions: for example, Rowe (Reference Rowe2008) uses dance as a metaphor to inform the mechanisms of team learning. Kolo (Reference Kolo2015) explores the potential contributions of choreography to organizational research, noting its focus on living together in time and space.

Setting the Stage: Ballet and Its Various Subgenres

Ballet is a performance dance that originated in fifteenth-century Italy before spreading to France and Russia (Homans, Reference Homans2013; Paskevska, Reference Paskevska2005). It combines both music and dance and was initially performed in chambers at royal courts by and for nobles. Strongly influenced by the schools of dance across those different geographies, the richness of ballet stems from a process of striking evolution where subgenres and stylistic approaches branched off without replacing prior styles (Sgourev, Reference Sgourev2021). For instance, the emergence of neoclassical and contemporary ballet did not erase the legacy of classical and Romantic ballet. Subgenres coexisted, informed each other, and addressed overlapping audiences (Sgourev, Reference Sgourev2015). Nowadays, ballet performances usually rely on a set of professional dancers who have undergone expert training, and performances of classical and Romantic ballet are still sought after as much as newer subgenres.

We cover a range of seven paradigmatic ballet performances across four subgenres: classical (Swan Lake, The Nutcracker), Romantic (La Sylphide, Giselle), neoclassical (Apollo), and contemporary (Clytemnestra, Isadora). (Anderson, Reference Anderson2018). We select those performances because they represent a diversity not only in the style of dance but also in the structure and dynamics of choreography. Though the different subgenres have borrowed characteristics from each other, the manner in which they combine different attributes in each case produces a distinct style of dance that informs subsequent theorization. In supplementary materials published online, Appendix A provides illustrative photographs of one ballet in each subgenre, and Appendix B provides links to videos of four ballets exemplifying the dynamics discussed in the article.

The most well-known type of ballet is also the first to emerge in Italy, France, and Russia: the classical ballet. This subgenre is therefore considered traditional and based on an established repertoire of movements, choreography, and story lines, supported by elaborate costumes and sumptuous sets (Sgourev, Reference Sgourev2015). Swan Lake and The Nutcracker are considered as the epitome of classical ballet and are characterized by large ensembles and a rigid narrative structure. The aesthetic value of this subgenre is derived from the technical execution of moves, with dancer interactions that tend to be frequent and symmetrical (Anderson, Reference Anderson2018).

Romantic ballets, on the other hand, despite having numerous overlapping elements with their classical counterparts, are distinct in their focus on the role and the performance of the dancers, with emotions as a source of aesthetic. These ballets emerged in the mid-nineteenth century, almost two centuries after the first academy of ballet, which formalized classical ballet as a professionalized art, was founded in Paris (Homans, Reference Homans2013). As with classical ballets, Romantic ballets are driven by linear storytelling and focus on technique but are distinguished by their emphasis on more episodic interactions between the characters. The Romantic subgenre highlights the prima ballerina, and the narratives often revolve around spirit characters, many of whom are female. La Sylphide is often considered as the first Romantic ballet, with a plot revolving around a young Scotsman’s infatuation with a forest spirit and his tumultuous relationships with his fiancée and best friend. Giselle is the second Romantic ballet we review and is the story of a woman who is revived by female forest spirits after dying of heartbreak.

With the passage of time, and at the turn of the 1910s, ballet productions started becoming more adventurous and experimental, in particular under the influence of Sergei Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes (Sgourev, Reference Sgourev2015). As with many cultural productions during this era, such ballets were expressions of opposition to the Romantic movement (Anderson, Reference Anderson2018) and were aimed at reviving and reinterpreting elements from traditional ballet. This new subgenre became known as neoclassical ballet and included spectacles like Apollo by George Balanchine, arguably the most well-known neoclassical choreographer. In contrast to Romantic ballets, the scenery and the costumes of neoclassical ballets are muted or in some cases absent, while narratives are more abstract and nonlinear. The dancers rely more on core body movements, with interactions that are physically asymmetric, combined with emergent connections that break away from formalities common in classical and Romantic ballets. In such ballets, dancers interact more through continuous opposition than through communion (Paskevska, Reference Paskevska2005). In the case of Balanchine’s Apollo, the story is oriented on the Greek god Apollo and three muses.

Contemporary ballets, finally, combine elements of classical ballets with more recent aspects of dance derived from jazz and mime (Paskevska, Reference Paskevska2005). They also rely on physical performances but are faster, reintroducing narrative centrality and incorporating acting during the performance. Clytemnestra by Martha Graham is thus characterized by energy and borderline violent dance moves, supported at the same time by a conspicuous narrative. The last performance we mobilize is Kenneth McMillan’s Isadora, a tribute to the life of dancer Isadora Duncan. Isadora is often seen as an act rather than a ballet, oriented around the life of the dancer and her tumultuous relationships with her partners.

The seven ballets we selected are emblematic of their subgenres; they were dominant at different epochs yet now coexist as iconic performances. They capture, in our view, the diversity of ballet choreographies; the striking differences across styles can be used to generate theoretical insights into the nature of stakeholder arrangements, as well as into organization–stakeholder relationships. In the following section, we proceed to translate those key characteristics into multiple dimensions that can apply to stakeholder engagement.

CHARACTERIZING STAKEHOLDER SYSTEMS AS BALLET CHOREOGRAPHY

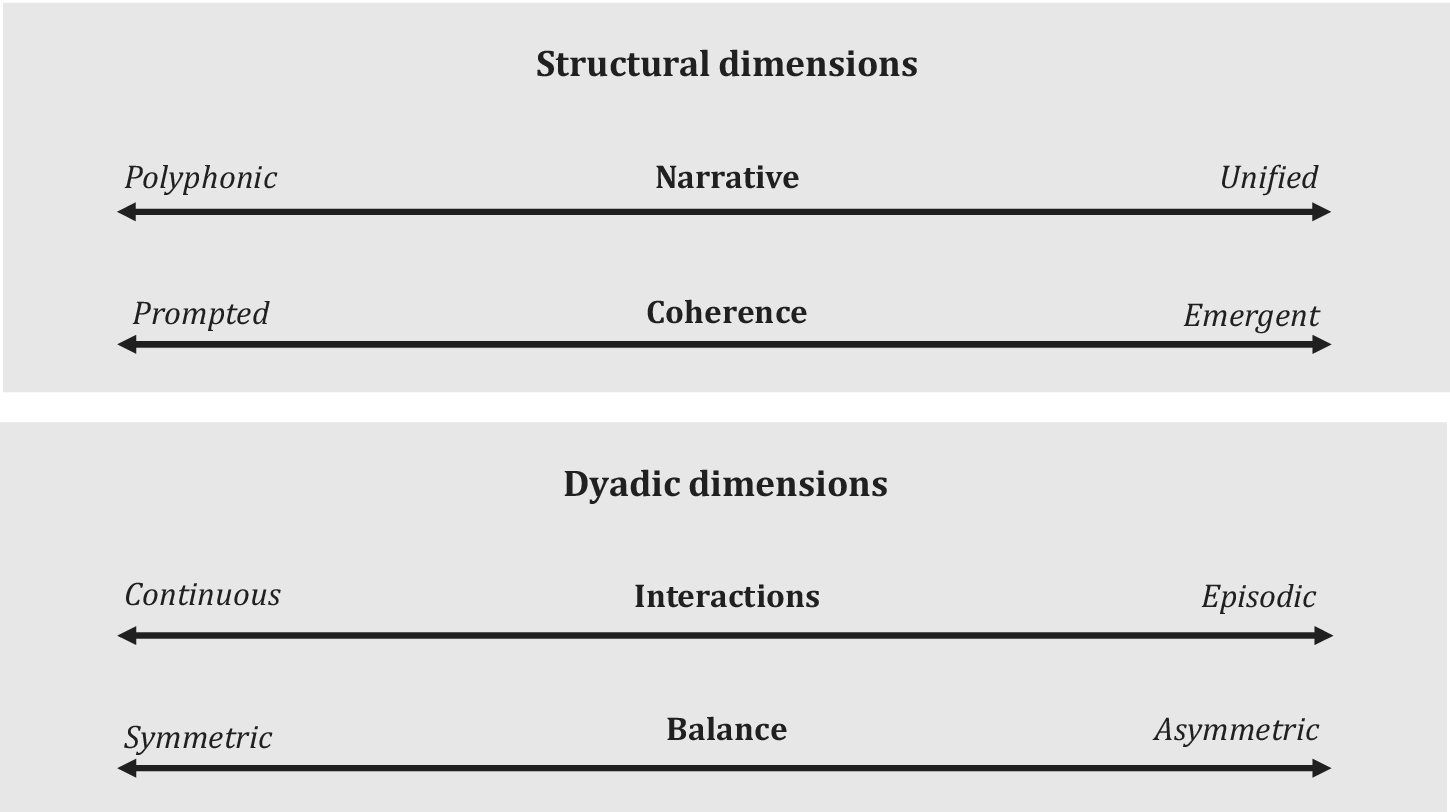

In this section, we aim at mobilizing our metaphor to flesh out the key characteristics of the system of ballet, upon which we can theorize the dynamics of a stakeholder arrangement. Through our identification of relevant dance theory work on ballet (Brandstetter, Reference Brandstetter2014; Burt, Reference Burt2000; Daly, Reference Daly1994; Hanna, Reference Hanna1987) and our review of the aforementioned ballet choreographies, we identify key dimensions of dance performances that revolve around patterning, pace, and motion. However, ballet choreography is about both the subjective experience of the dancers and the audience’s evaluation (Hanna, Reference Hanna1987); in this sense, two aspects of the theorization of ballet (Paskevska, Reference Paskevska2005) can be extended to the domain of stakeholder thinking. In contrast with traditional stakeholder thinking, which focuses on economic value (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Harrison and Zyglidopoulos2018), we consider how aesthetic value—or the appropriateness of what is staged—can translate into stakeholder thinking. More specifically, we consider that the appropriateness of a stakeholder system depends on the means and ends of the arrangement in addressing grand challenges (Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012; Prell, Hubacek, & Reed, Reference Prell, Hubacek and Reed2009). We consequently illuminate four major dimensions of dance at two levels, revealing system-level properties of the overall stakeholder systems as well as relational (i.e., dyadic) characteristics between two actors. The metaphor of ballet therefore allows us to theorize about dynamics in stakeholder arrangements and relationships simultaneously. Table 1 presents our interpretation of the structural and dyadic characteristics of the four types of ballet, while Figure 1 distills these into four dimensions.

Table 1: Subgenres of Ballet and Characteristics of Systems

Figure 1: Transposing Dimensions from Ballet to Stakeholder Systems

The first two dimensions that emerge from the ballet choreographies relate to the structural characteristics of the stakeholder system. Here the choreographic elements of the ballet are conceptualized as characteristics of the overall stakeholder arrangement. The remaining dimensions elucidate dynamics at the dyadic level. In this metaphor, the focal firm is taken as a principal dancer, with interactions that occur not only between this dancer and the supporting cast but also among other dancers themselves. Within this metaphor, individual stakeholder interactions are seen as a set of dance moves between dyads; from our range of ballet performances, we observe differences in how dancers are expected to interact and interface. Transposed onto the domain of stakeholder systems, this informs the ways we conceptualize stakeholders connecting with each other. Taken together, the four dimensions not only help us reveal the quality of interactions but also pave the way for understanding how stakeholder systems evolve, adapt, and synchronize.

Structural and Dyadic Characteristics of Ballet (and Stakeholder) Systems

Structural Dimensions

Polyphonic versus unified narrative. The classical and Romantic ballet performances are typically choreographed as a unified narrative, generally oriented around a principal dancer; effectively, this style organizes the rest of the dance troupe and can be readily communicated to the audience. The Romantic ballets of La Sylphide and Giselle, for instance, follow the story of a principal female spirit character and their relationships with a human male. Alternatively, neoclassical ballet (in our case, Apollo) relies on a multiplicity of intricate narratives, often in the background, as the performance relies less on a unified plot than on a confluence of distinctive and competing narrative threads. Thus a dance can also be choreographed as a polyphonic narrative, with a “multiplicity of independent and unmerged voices and consciousnesses … each with equal rights and its own world [that] combine, but do not merge, into the unity of an event” (Bakhtin, Reference Bakhtin1984: 208). In those pieces, the aesthetic value is derived from following multiple perspectives on the same event.

We conceive these as two ends of the same spectrum: applied to a stakeholder system, this dimension reveals the extent to which multiple stakeholders share a narrative with a focal actor, such as a firm. At one end of the spectrum, we have a unified narrative, where the entire stakeholder system approaches an issue from the same perspective, with consensus around definition, diagnosis, and/or goals. This can be driven by a focal organization that leads how sense making occurs around an issue; for instance, Bothello and Mehrpouya (Reference Bothello and Mehrpouya2018) discuss how a nongovernmental organization (NGO) named ICLEI created a framing of sustainable urban development that other NGOs eventually adopted. However, a unified narrative can also emerge in the absence of direct ties: Haas (Reference Haas1989, Reference Haas1992) illustrates how stakeholders mobilized toward regulation of ozone-depleting substances and Mediterranean pollution through similar understandings of cause-and-effect relationships, despite being disconnected from each other.

At the other end of the spectrum, when causal attributions are more complex, multiple divergent perspectives within a stakeholder arrangement can emerge, leading to a polyphonic narrative (Belova, King, & Sliwa, Reference Belova, King and Sliwa2008; Hargrave, Reference Hargrave2009). Different pockets of social actors within the stakeholder system perceive an issue differently, and their own perspective evolves independently from other narratives. Reinecke and Ansari (Reference Reinecke and Ansari2016) highlight how polyphony is endemic to these so-called wicked problems as they observe the diverging perspectives of various actors in the context of conflict minerals in Democratic Republic of Congo. These actors not only possess differing ideas of prescriptions to a problem but also disagree on the diagnosis of the problem itself.

Prompted versus emergent coherence. The second dimension articulates a key aspect common to both choreography and stakeholder systems, namely, the motivation that drives the arrangement to coalesce in the first place. Classical and Romantic ballets tend to be highly deterministic and scripted; appropriateness is based on technical proficiency, where dancers’ moves are programmed and propelled by the narrative. In contrast, the neoclassical and contemporary ballets are based more on an organic evolution rather than on adherence to a scripted routine; the appropriateness of the choreography is contingent on reactions to and from other characters. For instance, in neoclassical ballets like Apollo or contemporary pieces like Clytemnestra, the appeal of the performance is partly derived from physical and emotional spontaneity, stemming from proximity to other dancers.

These characteristics inform our second dimension of coherence. While the previous dimension of narrative focuses on the process of ongoing sense making and storytelling, coherence is about whether actors are “pushed” or “pulled” together. Applied to stakeholder theory, actors may be pushed together or prompted to form an arrangement, for instance, when a crisis threatens to harm an organization and/or its constituent stakeholders (Pearson & Clair, Reference Pearson and Clair1998). The COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, spurred the creation of the COVAX facility to ensure equitable distribution of coronavirus vaccines, an initiative involving Gavi (an alliance of for-profit vaccine producers), the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, and the WHO (McAdams, McDade, Ogbuoji, Johnson, Dixit, & Yamey, Reference McAdams, McDade, Ogbuoji, Johnson, Dixit and Yamey2020). Alternatively, an arrangement can cohere in the absence of such prompts, forming more organically through common interests that “pull” together to address an important—albeit not necessarily urgent—problem. These emergent stakeholder arrangements can still be facilitated by external actors to catalyze problem solving: for example, we observe how supranational actors, such as the UN, play an essential role in “orchestration,” creating platforms and fora for stakeholders to self-organize around a specific issue (Abbott & Snidal, Reference Abbott and Snidal2010; Andonova & Levy, Reference Andonova and Levy2003). We conceptualize these systems as the other end of the spectrum, where an arrangement coheres in the absence of a shock (Aakhus & Bzdak, Reference Aakhus and Bzdak2015; Allen et al., Reference Allen, Maguire and McKelvey2011; Anderson, Reference Anderson1999). This is a common process in the case of MSIs, which usually come together to solve specific issues, such as climate change (de Bakker, Rasche, & Ponte, Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019), even if there is no short-term threat.

The two structural dimensions that we outline here are distinct yet complementary: the narrative dimension captures the evolving discursive aspects of the system, while coherence focuses on the triggers driving the emergence of the system. We observe a range of combinations: a stakeholder system can, for instance, emerge organically without forming a unified narrative; some initiatives around addressing a social issue feature a diversity of frames or viewpoints that do not need to be reconciled over time (Reinecke & Ansari, Reference Reinecke and Ansari2016). On the other hand, a prompted system can create a unified narrative despite the relevant actors coming from diverse backgrounds. Table 2 summarizes the four structural conditions of a stakeholder system and showcases illustrative examples of each.

Table 2: Structural Dimensions of a Stakeholder System

Dyadic Dimensions

In contrast to the first pair of dimensions, which focus on structural characteristics, our second pair relates to the dyadic ties between the focal organization (principal dancer) and its related stakeholders (supporting dancers). Contingent on the arrangement, these insights potentially extend to relationships between supporting dancers themselves. In the seven ballet performances we included, we focused on the properties of the interactions between individual dancers. In particular, the “importance of movement (the fact of bodily action) and motion (illusion and residual action resulting from the kind of movement produced)” lies in the way they connect individual performers (Hanna, Reference Hanna1987: 37). Within the discursive space created by the performance (Brandstetter, Reference Brandstetter2014), the interaction between dancers also signals the balance of power. Such interactions not only determine the immediate performance but also contribute to the unfolding of the narrative (Burt, Reference Burt2000; Roulet, Reference Roulet2020). We use dance theory to outline these dimensions, then proceed to apply them to firm–stakeholder relationships as well as to linkages between stakeholders.

Continuous versus episodic interactions. The first of these dimensions is based on the continuity of interactions: relationships may be episodic and sporadic, or they can be continuous. Classical ballets, such as The Nutcracker, follow the same duo of characters—Clara and the Nutcracker—and make them the focal point of the entire performance. In La Sylphide, the interactions between the main characters—the Sylph and the Scotsman—are more intermittent as they are brought together and taken apart several times throughout the ballet. Part of the aesthetic value of these performances is contingent on the rhythm, pace, and frequency of these interactions. By contrast, Clytemnestra and Isadora feature complex webs of characters who interact intensely but irregularly with each other.

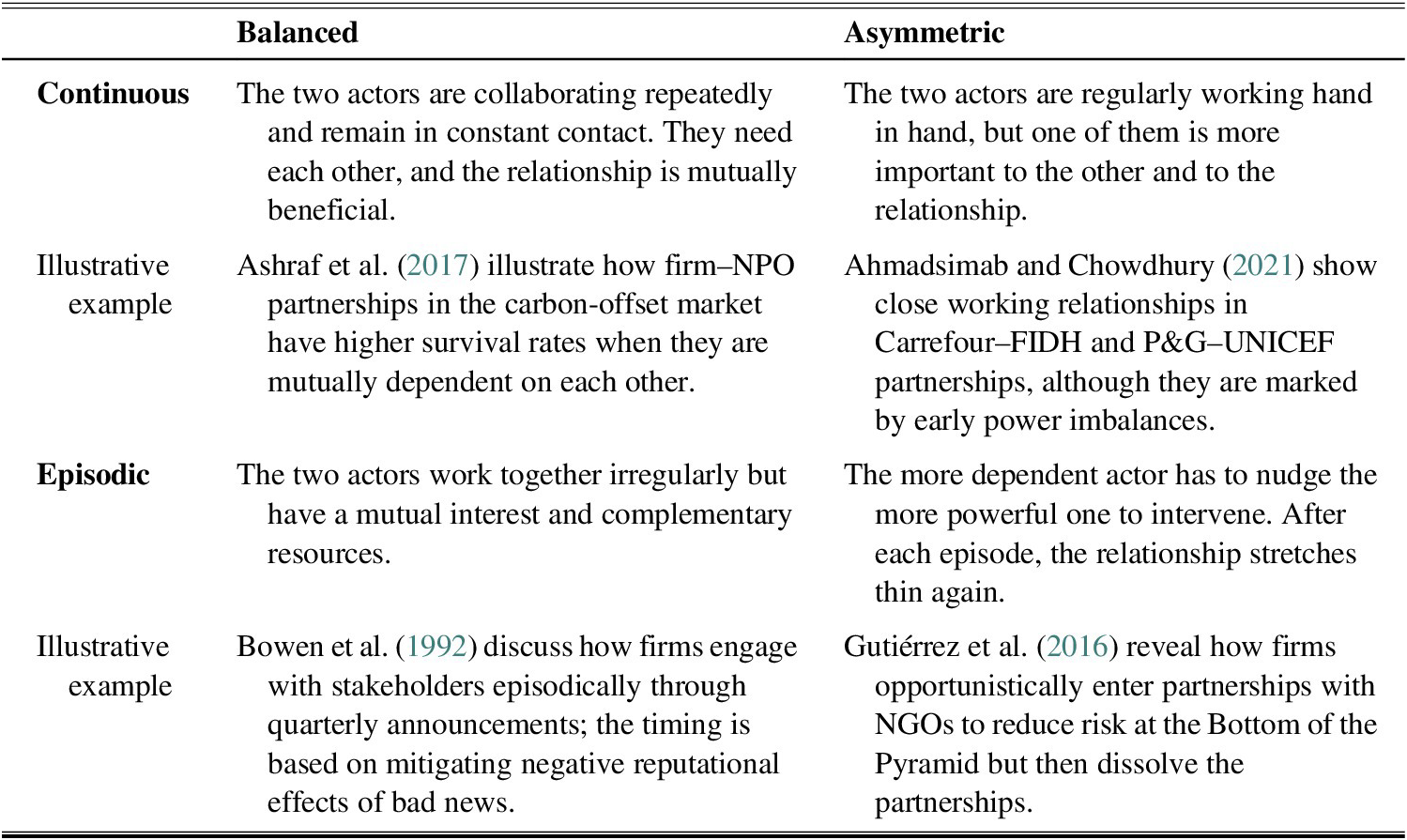

Similarly, the frequency of firm–stakeholder relationships can be mapped as two ends of a continuum. Episodic interactions of dancers are likely to be ad hoc, triggered by unpredictable issues that emerge in the relationship and irregularly increase stakeholder urgency (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Agle and Wood1997), for instance, product recalls or supply chain breakdowns. Accordingly, the episodic nature of these relationships implies transactional and market-based collaborations (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Harrison and Felps2018), as those episodes usually call for swift resolutions—or at least attempts at them. At the other end of the continuum, in the same way that two dancers remain entangled for the whole performance, we can imagine firm–stakeholder relationships that are continuous. Those are more likely to be labeled as working relationships (Welcomer et al., Reference Welcomer, Cochran, Rands and Haggerty2003) that are stable and consistent over time, often based on norms of mutual reciprocity (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Harrison and Felps2018).

Symmetric versus asymmetric power. Across the different ballet performances, we consistently observe characters influencing the movement and behavior of others (Daly, Reference Daly1994). For instance, Clara frees the Nutcracker from a spell, while the Sylph in La Sylphide entrances the Scotsman, drawing him into the forest. By and large, though, Romantic and classical ballets usually involve highly symmetrical performances, with the dancers engaging in reciprocal interactions. By contrast, neoclassical and contemporary ballets often rely on asymmetrical dancing that often includes physical and symbolic dependence; Apollo, for instance, features the main dancer hoisting and holding aloft a muse on his back for several minutes, while in another scene, he “grants” space for the muses to take center stage and express themselves in turn.

When transferred to the realm of stakeholder relationships, we argue that this dimension of balance captures the extent to which one party exercises power and influence over another in a relationship (Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2015; Hillman, Withers, & Collins, Reference Hillman, Withers and Collins2009), usually through control over crucial material, human, financial, and symbolic resources. As Mitchell et al. (Reference Mitchell, Agle and Wood1997) note, certain stakeholder arrangements may be characterized by power asymmetry that is either firm dominant or stakeholder dominant, where the actor providing resources uses this ability to control the relationship and dominate decision-making. Yet there also exist instances of firm–stakeholder relationships in which both parties are mutually dependent on each other (Ahmadsimab & Chowdhury, Reference Ahmadsimab and Chowdhury2021; Ashraf, Ahmadsimab, & Pinkse, Reference Ashraf, Ahmadsimab and Pinkse2017). This symmetry within a relationship usually accompanies a bidirectional sharing of resources.

Taken together, our theorization of the two dimensions of dyadic relationships within stakeholder systems acknowledges and integrates a wider range of relationship dependencies and dynamics beyond what is covered in prior studies (Bundy, Vogel, & Zachary, Reference Bundy, Vogel and Zachary2018). Importantly, the nature of these dyadic characteristics applies to both firm–stakeholder relationships and stakeholder–stakeholder linkages. Our conceptualization, therefore, does not necessarily consider the firm as the center of the system but rather as one actor within a larger constellation of actors oriented around a particular issue. Table 3 summarizes the four conditions of dyadic relationships within a system and illustrates those four situations with relevant examples.

Table 3: Dyadic Dimensions of Stakeholder Relationships

THE DYNAMICS OF STAKEHOLDER SYSTEMS

In the previous section, we characterized stakeholder systems using two attributes at the structural level (narrative and coherence) and two attributes at the dyadic level (continuity and balance of power). We do not make the case, though, that these are exhaustive; rather, they demonstrate how new analytical dimensions emerge when we reconceptualize stakeholder arrangements using a novel systems metaphor. Yet systems are by nature dynamic (von Bertalanffy, Reference von Bertalanffy1972): they transform over time when, for instance, constituent members and their relationships with each other change or when goals evolve (Anderson, Reference Anderson1999; Werhane, Reference Werhane2002); this affects how the arrangement ultimately mobilizes together to collectively solve an issue. In the following section, we build on our fundamental characteristics to offer a dynamic model exhibiting potential adaptive paths taken by stakeholder systems.

Key Assumptions to Identify Dynamics of Stakeholder Systems

Although we distinguish between structural characteristics and dyadic relations of stakeholder arrangements, a systems perspective also highlights how the two sets of dimensions are interrelated. Lawrence (Reference Lawrence, Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin-Andersson and Suddaby2008), for instance, suggests that influence and force—which are individual-level expressions of power—condition and are conditioned by institutional-level forms of power, such as domination and discipline. A systemic perspective therefore acknowledges the importance of feedback loops (Levasseur, Reference Levasseur2004) as changes in the subpart of the system affect the system as a whole. Conversely, dynamics of the system trigger change at the micro-level. We can imagine the interaction between structural and dyadic dimensions to be recursive: structural dimensions would affect dyadic elements, which would in turn affect structural dimensions, and so on. This recursive cycle might well contribute to the disruption of the system but also potentially to its maintenance (Islam, Zyphur, & Boje, Reference Islam, Zyphur and Boje2008).

Accordingly, we proceed to theorize how the dynamics in structural characteristics and those at the dyad level potentially co-constitute each other. On one hand, dyadic ties are affected by structural characteristics of the overall arrangement—for example, more ties can be created when the overall system is larger. On the other hand, some higher-level system characteristics can be derived from the attributes of components interacting (von Bertalanffy, Reference von Bertalanffy1972: 411)—this implies that an aggregation of dyadic changes may result in changes to structural characteristics. Although there may be a multitude of potential paths linking structural and dyadic dimensions of stakeholder systems, we focus on what are potentially the most salient connections. Accordingly, the insights we develop are based on the characteristics of two specific dynamics of stakeholder systems. They are meant, not to be exhaustive or to capture all potential evolutions of stakeholder systems, but simply to illustrate the explanatory power of our model to formulate relevant scenarios.

Illustrating the Dynamics of Stakeholder Systems

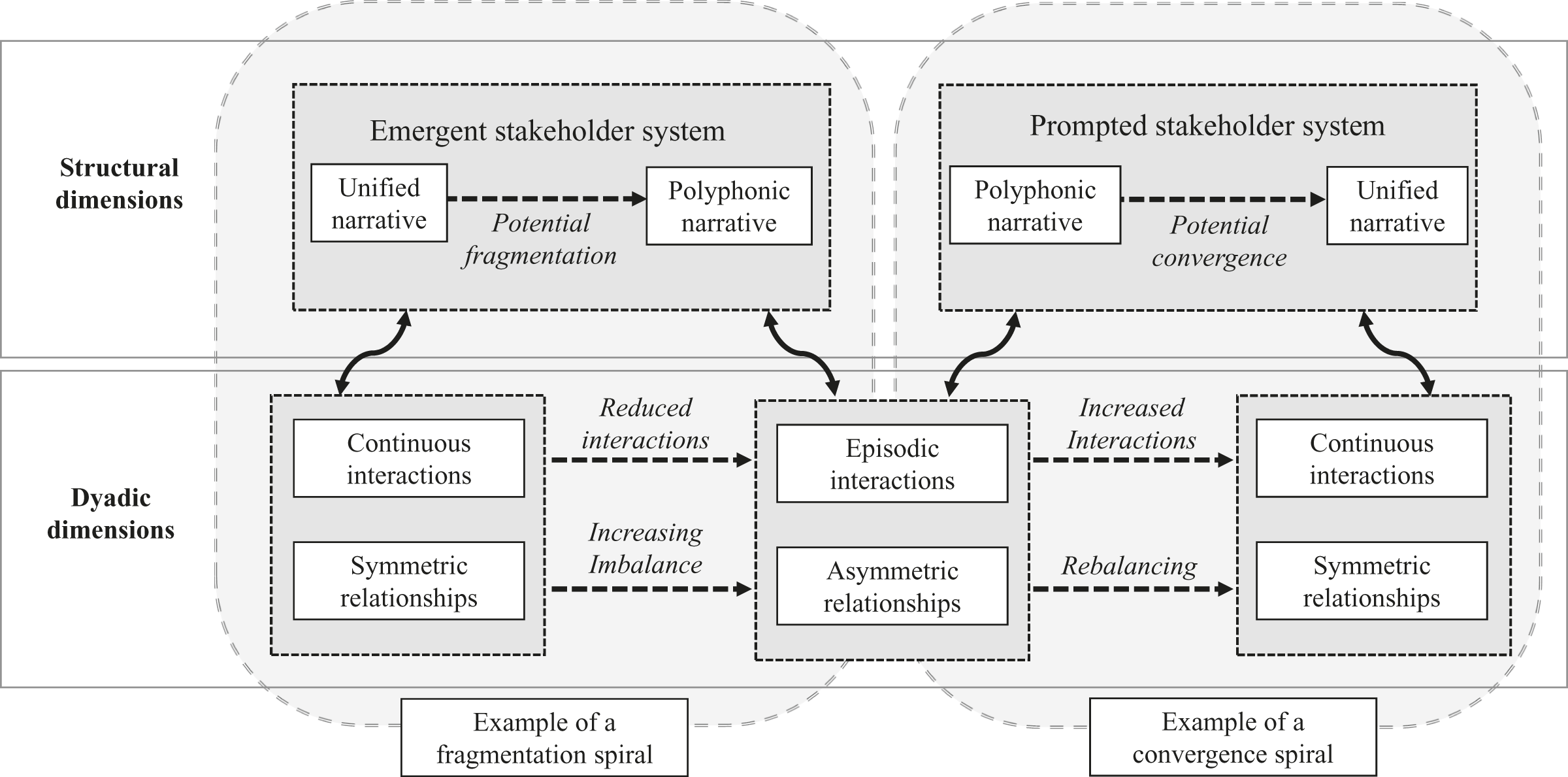

We proceed to highlight two potential dynamic paths that stakeholder systems may take (Figure 2): the first illustrates how structural and dyadic dimensions are interrelated and coevolve in an emergent system, while the second depicts the same process, but in a prompted system. In doing so, we can point to the recursive relationships between dyadic and structural dimensions in our model, while outlining how both evolve over time.

Figure 2: Potential Dynamic Paths in Stakeholder Systems

In situations of emergent stakeholder systems, stakeholders may be brought together organically through, for instance, shared interests or geographical and political proximity. Initiatives with voluntary participation and proximity in interests and understanding are likely to bring together actors that share at least some common understanding of the issue, indicating a unified narrative at the system level. Early on in such a system, we propose that this results in balanced relationships and continuous interactions. However, this dynamic may not necessarily persist. Numerous studies in the area of private and transnational governance highlight a process where stakeholders convene to address a social or environmental problem but, over time, fragment into competing interests with different views of the problem (Bothello & Mehrpouya, Reference Bothello and Mehrpouya2018). While this may not necessarily happen, an emergent stakeholder system coupled with a unified narrative may risk a fragmentation spiral. If the stakeholder system does not converge toward potential solutions, differences between stakeholders’ perspectives are more likely to emerge (Gutiérrez, Márquez, & Reficco, Reference Gutiérrez, Márquez and Reficco2016), leading to the fragmentation of the narrative. In turn, such fragmentation is likely to generate imbalance in dyadic relationships as positions become more entrenched and interactions more episodic. Recursively, those degraded dyadic relationships further fragment the narrative into polyphony.

There are several empirical accounts of such a spiral. Fransen (Reference Fransen2011; Fransen & Conzelmann, Reference Fransen and Conzelmann2015) reveals how, for instance, the fragmentation of private sustainability standards in forestry and clothing partially stemmed from regulatory actors that became too stringent—an issue which hints at dyadic power imbalance between the regulator and the regulated. In this situation, we witness a fragmentation spiral triggered by the effect of deteriorating dyadic relationships on structural dimensions of the stakeholder system. Yet the reverse can also occur, where narrative plurality leads to power imbalance: Marques (Reference Marques2019) demonstrates how transnational governance settings that are highly fragmented can, in some cases, result in regulatory capture by industry and trade associations. This therefore shifts the power balance in dyadic relationships, asymmetrically favoring business interests.

In the case of a prompted system, on the other hand, stakeholders may be cast together (perhaps unwillingly in situations of crises) and obliged to interact and coordinate. Different actors struggle to make sense of the issue or phenomenon, specifically with respect to cause–effect relationships and potential solutions (Reinecke & Ansari, Reference Reinecke and Ansari2016). In such situations, actors produce different perspectives on a problem and lack the experience of productive dialogue and exchange (Daudigeos, Roulet, & Valiorgue, Reference Daudigeos, Roulet and Valiorgue2018). As a result of this plurality of narratives, we expect dyadic relationships to be, at this early stage, episodic and asymmetric; this may in turn reinforce polyphony at a system level.

Over time, though, the repeated interactions between stakeholders in this newly formed system may enable mutual learning and thus homogenization—about both the issue at stake and others’ perspectives. Hargrave (Reference Hargrave2009), for instance, discusses how moral imagination can facilitate collective action toward an overarching goal, even among competing interests. As stakeholders coordinate in this prompted system, they may compromise or rethink their initial positions (Hill & Jones, Reference Hill and Jones1992), facilitating convergence on a unified narrative (de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019). We argue that, recursively, this unified narrative will positively influence stakeholder relationships. First, this will increase the continuity of the relationship as partners develop a common language, perspective, and purpose (Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012). Second, because of this unifying narrative, stakeholders can learn, coalesce, and reorganize themselves to minimize their dependencies and increase their negotiating power (Gutiérrez et al., Reference Gutiérrez, Márquez and Reficco2016). In turn, those more frequent interactions caused by their embeddedness in a developing system will further the unification of the system’s narrative.

This convergence spiral is one of the potential dynamics of a prompted stakeholder system. As the stakeholder system is forced into collaboration and suffers from polyphonic narratives, the dyadic level is characterized by episodic interactions and asymmetric interactions. At this stage, stakeholders necessarily struggle to understand each other’s position and rationale and what they have to offer to each other. As the narrative becomes more homogenous, and stakeholders learn from each other, interactions become more frequent and balanced.

An example of this process can be observed in the stakeholder systems that work toward solving climate change (Ansari, Wijen, & Gray, Reference Ansari, Wijen and Gray2013; Schüssler, Rüling, & Wittneben, Reference Schüssler, Rüling and Wittneben2014). Ansari et al. (Reference Ansari, Wijen and Gray2013), for instance, highlight how a disparate set of actors with distinct logics were brought together to address the problem of climate change. Through a series of field-configuring events, these actors collectively created an overarching consensus of the problem in addition to solutions, such as the Kyoto Protocol. Although coming from diverse perspectives, they learned from each other, compromised, and accepted each other’s system of rationality. Thus they converged toward a unified narrative, also benefiting dyadic relationships, which recursively furthered a common systemic understanding and approach.

DISCUSSION

Using the metaphor of ballet choreography, we sought to highlight the merits of a systems view of stakeholders. Our stakeholder system theory stresses the importance of simultaneously considering structural dimensions of stakeholder arrangements and dyadic characteristics of stakeholder relationships. Building on the argument that two sets of dimensions recursively affect each other, we illustrated the explanatory power of our model of stakeholder systems: we identified two potential paths for stakeholder systems to evolve, following a fragmentation or a convergence spiral, based on interactions between dyadic and structural dimensions. These are meant merely to map some part of the reality of stakeholder system dynamics, although we also acknowledge the possibility of myriad different directions. The dynamics of stakeholder systems can experience different pathways due to differences in the nature of external jolts (Michaelson & Tosti-Kharas, Reference Michaelson and Tosti-Kharas2020) or initial configurations or the specific issue at stake (Bothello & Salles-Djelic, Reference Bothello and Salles-Djelic2018; Djelic & Quack, Reference Djelic and Quack2007).

We expect that the metaphor of ballet choreography and our characterization of stakeholder systems will open new areas of research and generate useful insights for existing literature. In particular, our metaphor should further the shift away from a focus on the economic value produced by stakeholder relationships (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Harrison and Zyglidopoulos2018) to provide a more encompassing, macro perspective that assesses the aesthetic value of stakeholders mobilizing toward achieving a goal (Harrison & Wicks, Reference Harrison and Wicks2013), specifically in the context of grand challenges (George et al., Reference George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi and Tihanyi2016). By extension, we hope that our systems approach can provide more comprehensive answers to outstanding questions in stakeholder-related research on social responsibility (Margolis & Walsh, Reference Margolis and Walsh2003) but also specific phenomena, such as MSIs (de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019; Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012), cross-sector social partnerships (Ahmadsimab & Chowdhury, Reference Ahmadsimab and Chowdhury2021; Ashraf et al., Reference Ashraf, Ahmadsimab and Pinkse2017), and transnational standard-setting (Djelic & Sahlin-Andersson, Reference Djelic, Sahlin-Andersson, Djelic and Sahlin-Andersson2006; Marques, Reference Marques2019; Reinecke, Manning, & Von Hagen, Reference Reinecke, Manning and Von Hagen2012).

From Stakeholder Dyads and Networks to Stakeholder Systems

Our framework offers important theoretical implications for stakeholder theory: in elucidating the implications of considering stakeholder arrangements as a system, we complement the stakeholder dyad (Freeman, Reference Freeman1984; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar and De Colle2010) and network (Rowley, Reference Rowley1997) perspectives that currently underpin much of current stakeholder research. Specifically, we are able to incorporate relational and structural aspects of the system simultaneously (Lawrence, Reference Lawrence, Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin-Andersson and Suddaby2008), while highlighting how the two may be interrelated. In this way, we reconcile, on one side, a more relational perspective on stakeholders, rooted in behavioral approaches (Bridoux & Stoelhorst, Reference Bridoux and Stoelhorst2014, Reference Bridoux and Stoelhorst2016) and studies of reciprocity (Bosse & Coughlan, Reference Bosse and Coughlan2016; Bosse, Phillips, & Harrison, Reference Bosse, Phillips and Harrison2009), with a more structural approach (Cots, Reference Cots2011; Okazaki et al., Reference Okazaki, Plangger, Roulet and Menéndez2020). Ultimately, we highlight how a systems perspective can reconceptualize actors as stakeholders of an issue rather than of a firm.

Our argument also proves generative to advancing stakeholder analysis, for instance, with respect to identification of stakeholders and assessment of their salience (Neville et al., Reference Neville, Bell and Whitwell2011). For instance, from a network perspective, stakeholders that are on the periphery of the network are viewed as marginal (Prell et al., Reference Prell, Hubacek and Reed2009). A systems perspective, on the other hand, illustrates how stakeholders may be disconnected from central actors but nonetheless be relevant because they share comparable goals and fulfill complementary roles. For example, many “epistemic communities” (Daudigeos et al., Reference Daudigeos, Roulet and Valiorgue2018; Haas, Reference Haas1989, Reference Haas1992) comprise stakeholder groups who, despite being fully disconnected from each other, mobilize toward addressing an issue because they share similar narratives (specifically, the understanding of cause and effect around a particular issue). A stakeholder systems perspective thus compels us to rethink identification and salience beyond the perspective of the focal organization (cf. Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Agle and Wood1997).

Furthermore, approaching stakeholder theory through a systems lens bears important implications with respect to the predictive power of stakeholder analysis. Traditional approaches to stakeholder theory focus on the performance of the focal organization (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Harrison and Felps2018), in other words, its ability to satisfy stakeholder demands or its corporate social performance (Margolis & Walsh, Reference Margolis and Walsh2003). By contrast, a systemic perspective can help address “grand challenges,” whose solutions necessarily involve a multiplicity of stakeholders coordinating with each other, not only with one focal firm or organization (George et al., Reference George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi and Tihanyi2016; Prell et al., Reference Prell, Hubacek and Reed2009; Tantalo & Priem, Reference Tantalo and Priem2016). Theory on MSIs (Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012) already reconceptualizes stakeholders as being concerned with an issue rather than with a firm. We note that our revised focus does not preclude the possibility of examining specific firms as the trigger of issues that bring stakeholders together; rather, it provides additional insight into how stakeholders act in concert once an issue becomes salient, irrespective of the source.

Despite this revised focus, a systems perspective nonetheless contains implications for firm strategy. For instance, a key competence for firms is to understand the narratives that drive the actions of different actors (Werhane, Reference Werhane and Phillips2011), rather than mediating the relationships between stakeholders as is proposed within a network perspective (Roulet & Pichler, Reference Roulet and Pichler2020). Firms can also proactively trigger the structuring of a stakeholder system around an issue (de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019); in advocating to make an issue salient, firms can also shape the process of emergence and coordination of an entire stakeholder system. For instance, in early international summits following the coining of the term sustainable development, for-profit actors formed an association called the Business Council for Sustainable Development, with a mandate to develop industrial best practices and provide input in environmental policy making (Bothello & Salles-Djelic, Reference Bothello and Salles-Djelic2018; Mebratu, Reference Mebratu1998). Thus firms have the capacity to structure actively the stakeholder system through sense-making activities, that is, by creating and establishing norms and narratives.

Interestingly, a stakeholder systems theory also advances what we could call the macro-foundations of stakeholder theory, rather than its micro-foundations. The micro-foundational perspective on stakeholder theory has already elucidated how stakeholders can be managed when they have heterogeneous motives (Bridoux & Stoelhort, Reference Bridoux and Stoelhorst2014), for example, when stakeholders favor fairness and reciprocity. A macro perspective zooms out to the arrangement as a whole, rather than focusing on its subparts. Such an approach allows us to consider the links between stakeholders (e.g., how they may influence each other) based on different roles and functions within the overall structure. In a macro-foundational perspective, the focus is how firms’ behavior can be enabled and constrained by their stakeholder systems—not only by individual stakeholder influences (Frooman, Reference Frooman1999).

Finally, our metaphor of dance also allows us to contribute to the literature on organizational systems, which has been the subject of revived interest in recent years (Shipilov & Gawer, Reference Shipilov and Gawer2020). By using the metaphor of dance, we introduce novel elements to the study of systems, such as pacing and rhythm (e.g., episodic vs. continuous interaction), that can be fruitful for understanding how firms and stakeholders interact (Barnett, Reference Barnett2007; Bowen et al., Reference Bowen, Johnson, Shevlin and Shores1992). Furthermore, through our distinction of “prompted” and “emergent” systems, we provide a basis for understanding which systems form through external triggers and which coalesce through their internal properties. Third, dance contains a judgment of value that is missing from other forms of system: a ballet is considered aesthetically appropriate in some combinations of system features but not others. This is what Hanna (Reference Hanna1987) calls aesthetic value—a judgment of the appropriateness of the arrangement. Systemic perspectives can benefit from going beyond considering only economic value to instead consider the value produced by the system for society in a broader sense. We can therefore point to novel elements of systems that have thus far been overlooked. We do not, however, claim that ballet is the only system that can elucidate these dynamics; it is but one system that is generative of stakeholder system insights.

Limitations and Future Research Avenues

The two structural and the two dyadic dimensions of our models could also be perceived as limiting the potential of our metaphor. To some extent, the choice of the characteristics of stakeholder systems we put forward in this theoretical piece might be circumscribing the dynamics we can theorize about. Future research could flesh out different characteristics of stakeholder systems—to go beyond what could be seen as simplifying binary contrasts in our current model—by further taking advantage of the rich literature on system dynamics. This also shapes potential pathways to change that can occur in stakeholder systems. As previously pointed out, the dynamics of stakeholder systems that we identify only cover parts of a broad and complex phenomenon. Future research could further explore the dynamics of stakeholder systems by identifying alternative pathways, depending on the issues at stake.

Furthermore, the choice of ballet for our metaphor could be criticized for offering too much of a Western lens on stakeholder theory, and also because ballet is often seen as a cultural products for elites. However, neoclassical and contemporary ballets have deviated quite significantly from elitist canons, tastes, and modes of consumption of their predecessors, as they relate far more to modern dance and more recent genres of music. Future research could bring in more music- or dance-related metaphors: jazz, for example, has been commonly used as a metaphor for organization (Lewin, Reference Lewin1998). Existing work has also recognized the importance of dance as not only a fruitful metaphor but also a methodological tool for organization studies (Biehl, Reference Biehl2017). While the metaphor of ballet is a plausible one (Cornelissen, Reference Cornelissen2005, Reference Cornelissen2006), we could consider other potential metaphors that could be explored to further stakeholder system theory.

Practical Implications: Organizing as a System

We believe that a systems-level view on how organizations engage with stakeholders has practical implications toward enabling positive social change and addressing grand challenges (Greenwood, Reference Greenwood2007). For managers, we argue that a systems view facilitates an acknowledgment that the firm may not be the hub or central node in problem solving around a specific challenge (Werhane, Reference Werhane and Phillips2011). Rather, it emphasizes the idea that businesses have particular contributions to make that, despite being necessary, may not be sufficient for tackling large-scale and pervasive social and environmental problems (Roulet & Bothello, Reference Roulet and Bothello2020). This entails the important recognition that other actors have roles and responsibilities in addressing an issue, as well as unique resources that firms cannot offer. Such complementarities among different actors are a crucial aspect of a systems-based view and reinforce the need for managers to strengthen—rather than substitute for—relationships with other actors in their environment. Our approach also suggests that third parties might orchestrate those systems and coordinate different parties, align the interests of different actors, and spread information (Berkowitz, Crowder, & Brooks, Reference Berkowitz, Crowder and Brooks2020).

Beyond this, our specific metaphor of ballet also contains managerial implications. Our image encourages awareness of how the structural and dyadic characteristics between firms and their stakeholders are interwoven and dynamic; for instance, relational traits like resource dependence are not fixed but evolve over time. Importantly, this evolution has an assessment of appropriateness by different organizational audiences. Specifically, managers should be aware that their interactions with stakeholders do not only contain functional qualities but are judged according to aesthetic standards by different actors. Finally, the general management of organizations can benefit from the metaphor of dancing (cf. Harrison & Rouse, Reference Harrison and Rouse2014), in particular to think about collaboration as harmonious coordination.

CONCLUSION

In this article, we sought to establish the first pillars of a “stakeholder system theory,” using dance theory and the metaphor of ballet. The structural and dyadic dimensions of stakeholder systems complement existing characterizations in stakeholder theory, whether the hub-and-spoke model of firm–stakeholder relationships (Bundy et al., Reference Bundy, Vogel and Zachary2018) or more recent network perspectives (Rowley, Reference Rowley1997). The metaphor that we provide helps overcome some limitations of existing stakeholder frameworks, namely, considering structural and dyadic aspects in isolation from each other and thus limiting our ability to theorize the dynamic and adaptive aspects of stakeholder systems.

Our perspective also departs from a focus on stakeholders of a firm to consider stakeholders of an issue (Saffer, Reference Saffer2019). We have sought to shift the debate away from stakeholder frameworks that focus on a central firm and its relationships with its constituents. Such accounts are based on specific conceptual premises that unduly ignore important considerations, such as the goal of the overall arrangement or the frequency of interactions. These perspectives are also ill suited to simultaneously consider the structural and dyadic levels of analysis, as well as their coevolution. To overcome those limitations, we brought in the metaphor of ballet choreography, building on the analysis of seven iconic performances across four subgenres. We used dance theory as a bridge to identify the key characteristics of those performances that could subsequently be translated into the stakeholder domain. Our resulting framework reconceptualizes stakeholder arrangements as “stakeholder systems,” in other words, a set of social actors attempting to address a particular issue. We aim for this metaphor and our resulting model to feed future research on grand challenges and inform how public and private actors coordinate to address environmental and social issues.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the feedback we received from our editor, Bruce Barry, and three anonymous reviewers. We also thank Bertrand Valiorgue, Emilie Bourlier-Bargues, Lionel Garreau, and participants of the April 2021 research seminar at Université Paris Dauphine on systems theory.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2021.36.

Thomas J. Roulet (t.roulet@jbs.cam.ac.uk, corresponding author) is an associate professor in organization theory at the University of Cambridge, where he teaches leadership, organizational behavior, and social sciences. His work focuses on negative social evaluations (stigma, scandals, etc.) and systemic and institutional approaches to social change. He has been published in academic outlets such as Academy of Management Journal, Academy of Management Review, Academy of Management Annals, and practitioner journals such as Harvard Business Review and MIT Sloan Management Review. His work has been covered in a number of media, including the Financial Times, the Economist, and Le Monde.

Joel Bothello is an associate professor of management in the John Molson School of Business, Concordia University, as well as the holder of the Concordia University Research Chair in Resilience and Institutions. His research examines a variety of business and society phenomena, including corporate social responsibility, informal economy entrepreneurship, and urban sustainability. His work has been published in leading academic and practitioner journals. Bothello is also the cofounder of Organization Scientists 4 Future (OS4F), a movement of organization and management scientists seeking to inspire action on climate change.