Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, recent high-profile infectious diseases covered by the mass media included severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the Ebola virus, and influenza A (H1N1). Going back even further, to the Later Middle Ages, we find economic shocks primarily caused by infectious disease and, to a lesser extent, by climate change, and the effect of the convergence of the two on lower crop yields from 1349 to 1357 as follows: “The extreme weather had a great deal to do with this but so too, did the mass slaughter of workers and managers inflicted by the Black Death” (Campbell, Reference Campbell2010: 301). New and renewed infectious disease outbreaks are emerging almost every year, and studies predict that this trend will continue due to a variety of factors, including an aging population and increased air travel for both personal and work-related reasons (Bloom, Black, & Rappuoli, Reference Bloom, Black and Rappuoli2017; Lang, Reference Lang2012). The impact of zoonotic viral infections in the workplace has also been underestimated, given the risk in occupational settings (Vonesch et al., Reference Vonesch, Binazzi, Bonafede, Melis, Ruggieri, Iavicoli and Tomao2019). There have also been calls for research addressing the ethical aspects of COVID-19 in particular (Narula & Singh, Reference Narula and Singh2020):

On February 27, 2020, a whistleblower alleged that employees of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) were not provided personal protective equipment (PPE), protocols were violated, and training was inadequate to protect these employees from quarantined Americans. This complaint also alleged that these HHS employees traveled back home on commercial aircraft, despite being exposed to quarantined Americans (Cochrane, Weiland, & Sanger-Katz, Reference Cochrane, Weiland and Sanger-Katz2020).

Further, 124 nurses and other healthcare workers at University of California-Davis, self-quarantined following exposure to an inpatient who later tested positive for COVID-19. The National Nurses United’s Executive Director reportedly said, “nurses and healthcare workers need optimal staffing, equipment, and supplies to do so. This is not the time for hospital chains to cut corners or prioritize their profits” (National Nurses United, 2020).

Amazon forum participants are reportedly debating surging prices during emergencies and the ethicality of such behavior on the part of retailers. Shortages of PPE such as masks have also been reported (Matsakis, Reference Matsakis2020).

President Trump signs executive order mandating that meatpacking companies reopen. The Sheriff of Black Hawk County, Iowa during a visit to meatpacking plan was reported as saying, “We saw plant management wearing masks, but only a third of the employees. They had outbreaks at that point” (Meyer & Williams, Reference Meyer and Williams2020).

But the idea is raising charged legal and ethical questions: Can businesses require employees or customers to provide proof—digital or otherwise—that they have been vaccinated when the coronavirus vaccine is ostensibly voluntary? (Stolberg & Liptak, Reference Stolberg and Liptak2021).

These five vignettes portray some of the major challenges confronting businesses following the outbreak of infectious diseases, epidemics, or pandemics. In this article, we argue that these business challenges also constitute ethical challenges. Each vignette revolves around a decision impacting a stakeholder group (ranging from consumers to employees). Some scholars argue that ethically responsible management centers on paying attention to stakeholders and not just shareholders (Freeman, Reference Freeman1994). Each vignette involves some degree of harm that could be created, mitigated, or prevented based on the decisions and actions of organizational decision makers. Organizations “have a duty not to impose danger or harm to others” (Kilcullen & Ohles Kooistra, Reference Kilcullen and Ohles Kooistra1999: 159).

Apart from a few exceptions related to AIDS (Maak & Pless, Reference Maak and Pless2009; Ryan, Reference Ryan2005) and bioterrorism (Simms, Reference Simms2004), there is a dearth of literature on business ethics and infectious disease, even though individuals are susceptible to infectious disease at the workplace (Li et al., Reference Li, Xu, Wagner, Dong, Yin, Zhang and Boulton2019). The nomenclature infectious disease ethics has been used to describe the unique ethical aspects associated with infectious diseases as follows:

Infectious diseases raise a relatively unique constellation of ethical problems. Because (in most cases) infectious diseases are spread from person to person, innocent individuals can present a threat to other innocent individuals. Issues of respect for liberty, responsibility, prioritization, discrimination, equality, and distributive justice arise acutely. Restrictions of liberty and incursions of privacy and confidentiality may be necessary to promote the public good (Selgelid, McLean, Arinaminpathy, & Savulescu, Reference Selgelid, McLean, Arinaminpathy and Savulescu2009: 150).

In response to episodic public health crises catalyzed by communicable infectious diseases, governments and organizations develop, implement, and enforce policies, procedures, protocols, and programs. Kumar and colleagues write about the 2009 H1N1 pandemic as follows: “Workplace policies could affect differential exposure to virus and disease incidence” (Kumar, Quinn, Kim, Daniel, & Freimuth, Reference Kumar, Quinn, Kim, Daniel and Freimuth2012: 134). This study finds an empirical relationship between the absence of paid sick leave (PSD) (as an illustration of workplace policies) and the incidence of new cases of influenza-like illnesses, with Hispanics experiencing greater risks. Workplace policies and support programs are targeted at three primary stakeholders: employees, independent contractors or gig workers, and customers. The ethical impact of COVID-19 and its impact on the global economy and labor market are captured by the International Labour Organization’s director general, Guy Ryder: “For millions of workers, no income means no food, no security and no future. … As the pandemic and the jobs crisis evolve, the need to protect the most vulnerable becomes even more urgent” (International Labour Organization, 2020).

We must also recognize where gaps, contradictions, or structural discrimination may exist in government pandemic response. As an example, home care workers are not protected by or identified as essential health workers in the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. As such, they are not protected by the act. In fact, home health care companies lobbied for their exclusion from the act. Yet, these home health care workers are working with adequate protection from SARS-CoV-2 based on the federal statute (Yearby & Mohapatra, Reference Yearby and Mohapatra2020). In the case where there is a gap in a federal policy, then it is incumbent upon the organization employing these workers to offer the protection that is not legally mandated. The Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) in SHRM Foundation’s (2013: 6) Effective Practice Guidelines: Shaping an Ethical Workplace Culture notes, “Legal compliance alone will not build an effective ethical culture.” Turning to a critique of organizational policies, in the same SHRM report, it is noted that not all organizational cultures are uniformly ethical, in part arising from the adequacy of not just organizational policies but systems too. Inadequacy of organizational policies from an ethical perspective may arise from perceptions of unfairness by workers (Society for Human Resource Management Foundation, 2013).

In this article, we aim to build on the interdisciplinary nature of business ethics (Arnold, Audi, & Zwolinski, Reference Arnold, Audi and Zwolinski2010). The intersection of epidemiology, bioethics, public health ethics, and stakeholder theory represents a novel contribution to the business ethics literature. Others recognize that there is no universally agreed upon ethical framework regarding infectious diseases (Smith & Upshur, Reference Smith, Upshur, Mastroianni, Kahn and Kass2019). They highlight the need to address employment and the financial consequences stemming from infectious disease control measures like quarantine and isolation. This requires identifying ethical issues, suggesting best practices in largely unchartered territory, and recommending ethically optimized public and business policy decisions and actions. Through this article, our aim is to show how an integrated, ethical framework has important implications for how we categorize, understand, and resolve the difficult decisions that emerge in the workplace under pandemic conditions.

BACKGROUND

Infectious Disease, Epidemics, and Pandemics

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; 2015) defines an epidemic as “the occurrence of more cases of disease than expected in a given area or among a specific group of people over a particular period of time.” Morens, Folkers, and Fauci (Reference Morens, Folkers and Fauci2009: 1018) recommend that a pandemic be defined as a “large epidemic.” Losses are associated with pandemics and measured by different metrics, such as excess death (Fan, Jamison, & Summers, Reference Fan, Jamison and Summers2018). For a pandemic, specific ethical issues arise, such as forcing the world to “make stark choices about fair access to medicines or vaccines if they become available” (Kupferschmidt & Cohen, Reference Kupferschmidt and Cohen2020).

These stark choices pinpoint how decisions are made and by whom. Geppert (Reference Geppert2020) applies the ethical principles of nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice in how decision-making processes should change in health care settings during a pandemic. Here we assert that organizational decision-making must also shift during a pandemic and can begin this evolution in thinking by incorporating bioethical principles into all types of organizations in an economy. Geppert specifically highlights how such decisions should shift from an individual decision maker to a more collective decision-making process. This shift to collective decision-making recognizes a stakeholder approach. The ethical principles Geppert endorses are based on differences between clinical and public health ethics as posited by Geppert. Critics of applying the four principles of bioethics to public health situations are long-standing (Kass, Reference Kass2001; Upshur, Reference Upshur2002). Kass (Reference Kass2001) advocates for a focus on positive rights. Kass defines public health as “the societal approach to protecting and promoting health” (1776). Upshur (Reference Upshur2002: 101) writes, “Public health practice differs substantially from clinical practice.” Stakeholder theory is also important for this consideration, given the organizational context we are exploring, and we discuss how these pieces intersect. We assert that organizational practice differs substantially from both public health and clinical practice but, in the case of an epidemic or pandemic, that all three practices are relevant. We discuss how each of these foundational principles applies within the workplace in the discussion of our integrated framework.

Infectious Disease at Work

The workplace is a dangerous territory for containing the spread of an infectious disease. COVID-19 is described as the first new occupational disease in ten years (Koh, Reference Koh2020). Edwards (Reference Edwards2016) estimates that employees experience 19–25 percent of all human-to-human contact at work, of which 34 percent involves some type of physical interaction. Despite the prevalence of infectious diseases at work and the relatively high physical contact among workers, previous work on infectious diseases in the workplace is limited (Su, De Perio, Cummings, McCague, Luckhaupt, & Sweeney, Reference Su, De Perio, Cummings, McCague, Luckhaupt and Sweeney2019). An even less studied area explores the ethical implications related to spread of an infectious disease at work, from inside the workplace to outside. There is a growing body of work focusing on health care workers and their role in minimizing the risk of transmission of infectious diseases (Lam, Kwong, Hung, Pang, & Chien, Reference Lam, Kwong, Hung, Pang and Chien2019).

Infectious diseases are indeed an economic issue, as described by Hall (Reference Hall1992: 199): “economic factors may increasingly influence healthcare decisions by raising issues of distribution and access in a time of limited resources.” For example, the trade routes in the 1300s were a mechanism of transmission of the Black Death in Europe (Yue, Lee, & Wu, Reference Yue, Lee and Wu2017). From the late 1800s until today, mine workers in South Africa are at a higher risk of acquiring tuberculosis (TB) and then transmitting TB to others, in part due to the practices of mining companies (Lurie & Stuckler, Reference Lurie and Stuckler2014). Research suggests that biological and economic risks are intertwined (Peckham, Reference Peckham2013), as exemplified by the H5N1 outbreak in 1997. Peckham recognized that public health and financial crises coexist, with the potential for generating tremendous profits. Other self-interested pursuits are hoarding and stockpiling of essential supplies, and even groceries (Snider, Reference Snider2020), by one party, resulting in possible harm to another party.

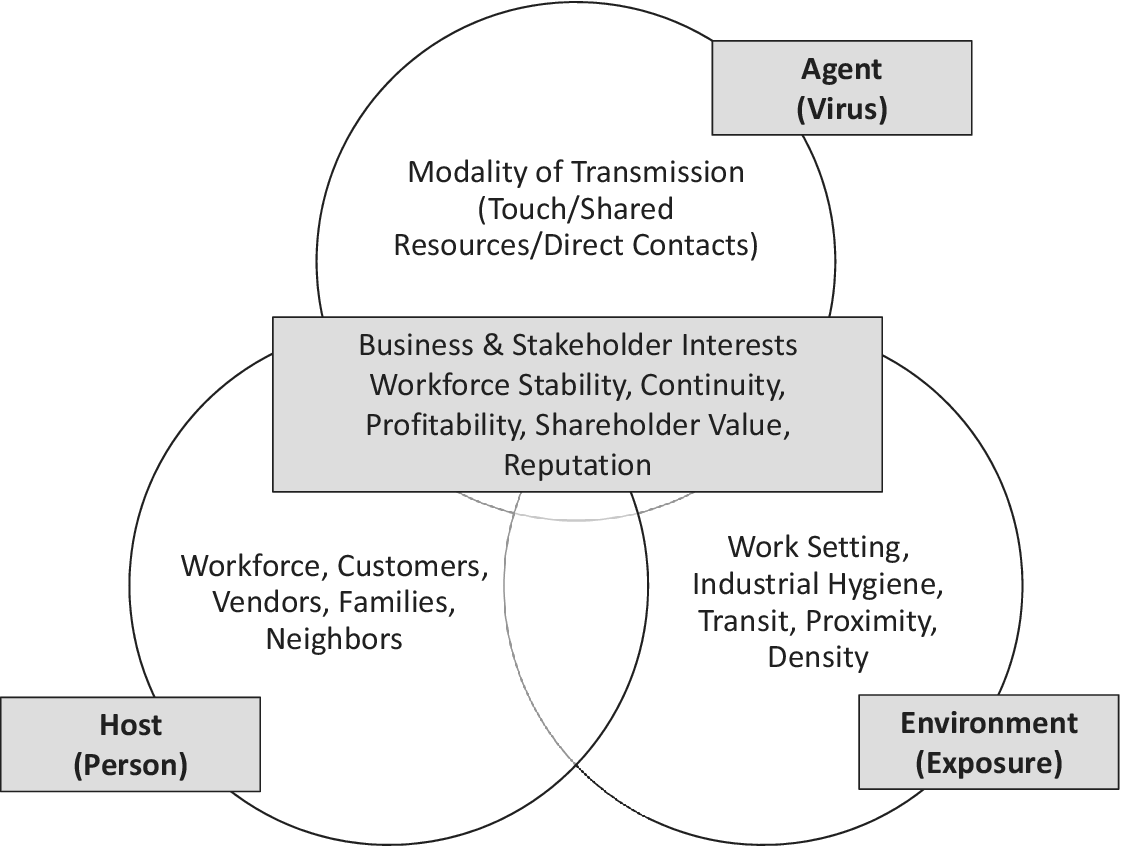

Employees in certain settings, such as health care, and engaged in certain workplace behaviors, such as caring for patients with symptoms associated with an infectious disease, face an increased risk of acquiring an infectious disease at work (Su et al., Reference Su, De Perio, Cummings, McCague, Luckhaupt and Sweeney2019). Regarding PPE shortages, administrators will be morally, ethically, and legally responsible for COVID-19 deaths arising from health care workers refusing to care for patients if “the shortage of PPE is a result of financial and procurement maladministration, negligence, incompetence, or indifference by administrators” (McQuoid-Mason, Reference McQuoid-Mason2020: 2). Other settings include cruise ships and their workers (Heymann & Shindo, Reference Heymann and Shindo2020). Reviewing the literature, we find that infectious diseases are propagated at work due to a host of factors, such as disease factors (e.g., mode of transmission), workplace factors (e.g., work practices and processes), and worker factors (e.g., socioeconomic status/language). These factors are aligned with the epidemiological triad of the agent (and the agent’s vectors), host, and environment (Last, Reference Last2001). This triad has been successfully applied to infectious disease epidemics (Egger, Swinburn, & Rossner, Reference Egger, Swinburn and Rossner2003), most recently to the Ebola virus epidemic (Kaur, Sachdeva, Jha, & Sulania, Reference Kaur, Sachdeva, Jha and Sulania2017). This triad can be directly applied to a workplace or employer by examining how each of the three components relates to this setting (see Figure 1). Then, we can begin to understand how these create ethical dilemmas for organizational decision makers when we overlay them onto business interests, such as continuity and profitability.

Figure 1: The Epidemiological Triad in the Workplace

Host: Who?

Humans are one host as it relates to COVID-19. The Los Angeles Times describes how xenophobia and nationalistic sentiment have resulted in Asians being targeted (Hussain, Reference Hussain2020), leading to physical attacks and the shutdown of many Asian businesses (Yam, Reference Yam2020). Robert (Reference Robert2020), in the American Bar Association Journal, reports on the role of employers in stopping such discrimination in the workplace. Host interventions may include education, behavior change, and pharmacological therapy (Egger et al., Reference Egger, Swinburn and Rossner2003). In a workplace, employers must consider who the potential hosts are—certainly employees, and customers, if they enter the space, but also vendors, advisers, and related service providers. Furthermore, conversations around hosts must recognize the variation and disparate impact on particularly vulnerable populations (i.e., low-wage workers, employees with disabilities or underlying chronic conditions).

Environment: Where?

We conceptualize the environment as the opportunity for exposure. This can be the building or the actual workplace itself. Regarding the physical building, transmission of viruses occurs not just from human to human but also from infected surfaces and materials through fomites (Clem & Galwankar, Reference Clem and Galwankar2009). However, the broader environment where the employer is situated must also be recognized. We must consider proximity to other businesses if employees operate in a dense environment with close quarters, as well as whether employees must use public transportation or travel as part of their work duties. Numerous decisions are under the control of organizational decision makers related to the physical environment of the business operation, such as controlling retail traffic, spacing customers, and inserting protective barriers between employees and the public. Knowing that viruses like SARS-CoV-2 are transmitted by aerosols, one costly but critical consideration for business reopening is making improvements to HVAC systems (Parker, Boles, Egnot, Sundermann, & Fleeger, Reference Parker, Boles, Egnot, Sundermann and Fleeger2020). These types of choices require pragmatic, strategic, and ethical decision-making.

Agent: What?

Traditionally, we consider the agent to be the virus/infectious disease itself as well as the modality of transmission. For example, SARS-CoV-2 is an example of an agent. Coronaviruses are enveloped RNA viruses found in mammals, birds, and humans. In a workplace setting, we must think about the points of contact between employees, or employees and clientele, both direct as well as indirect through shared resources. We must also think about the degree to which organizations operate in a way that contributes to the broader issues related to climate change, which may create a ripe environment for the emergence of new viruses. An example would be whether an organization reduces emissions contributing to pollution, such as the Volkswagen emissions scandal, which is described from the lens of democratic business ethics (Rhodes, Reference Rhodes2016). There have been calls to include climate change within bioethics (Macpherson, Reference Macpherson2013), and others have gone on to describe the relationship between public health ethics and environmental ethics, for example, Lee (Reference Lee2017: 9):

The overlap of public health and environmental ethics also has evolved recently as global climate change and devastation of habitat have exacerbated new and neglected infectious diseases that are transmitted from animals and insects and take a toll on population health.

Applying the Epidemiological Triad in the Workplace

The epidemiological triad (Mausner, Kramer, & Bahn, Reference Mausner, Kramer and Bahn1985) is both a model of disease causation and fundamentally a model used to design and deploy infection control measures. Agencies such as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA; 2020) have released guidance to facilitate planning based on risk identification followed by the implementation of control measures. We will use the epidemiological triad to characterize the related ethical challenges in implementing the control measures faced by employers in the next section and as a guide for our workplace intervention framework in the fourth section.

INTEGRATED ETHICAL FRAMEWORK

Numerous and varied ethical challenges confront decision makers in the workplace during a pandemic. These challenges impact various stakeholders, such as employees, contractors, customers, and vendors, including the stakeholders’ families. Many ethical challenges revolve around what is best for the individual versus the collective, while recognizing that these two are not mutually exclusive. Any set of moral principles is essential for several reasons. First, moral principles enable us to discern that which is salient and warrants our attention and that which is not (O’Neill, Reference O’Neill2001). Second, moral principles are “conceptual resources” that enable us to get a handle on complex situations (Smith & Dubbink, Reference Smith and Dubbink2011: 217). One such illustrative complex situation involves the stay-at-home orders enacted by US governors and mayors. Some (Gostin & Wiley, Reference Gostin and Wiley2020: 2137) argue that “individual freedom is not absolute” but “balanced against compelling public health necessities.” Our framework is intentionally principle based. Upshur (Reference Upshur2002) pinpoints that a principle-based approach is practical and heuristic. Others write about the utility of principles by stating that “principles serve as a record of last resort for this information and are therefore an important ingredient in justifying one’s judgment in any one case” (Smith & Dubbink, Reference Smith and Dubbink2011: 218). Yet, Beauchamp and Childress (Reference Beauchamp and Childress2019), in reflecting upon the fortieth anniversary of their landmark book Principles of Biomedical Ethics (1979), respond to the critiques of principlism as not being posited as a panacea but rather as a method to deliberate and justify actions. Here we review the principles used to characterize the ethical challenges encountered during a pandemic. Table 1 offers concise definitions for each of the principles we highlight.

Table 1: Definitions of Primary Ethical Principles and Theories

Bioethics

Wicks (Reference Wicks1995) suggests that bioethics be examined by business ethicists, calling for greater emphasis on interdisciplinary work. The applicability of integrating bioethical principles with business ethics is illustrated by the following statement: “Among the moral principles that are germane in business ethics are the principles of rights, justice, beneficence, utility, non-maleficence, and truth telling” (Wicks, Reference Wicks1995: 29). These are the bioethical principles posited by Beauchamp and Childress (Reference Beauchamp and Childress2013). Bioethical principles may be used as a guide to identify and solve problems, make decisions, allocate resources, and evaluate the success or failure of past events, while recognizing that these bioethical principles may conflict with each other and other organizational factors, such as legal compliance and profit maximization. As critics of their own framework, the developers of these bioethical principles admit, “We do not suppose that our principles and rules exhaust the common morality; we argue only that our framework captures major moral considerations” (Beauchamp & Childress, Reference Beauchamp and Childress2013: 10).

Beauchamp and Childress (Reference Beauchamp and Childress2019) discuss the applicable situations for the four biomedical ethics principles included in their framework. These applicable situations include those characterized by novelty, uncertainty, ambiguity, and moral conflicts (Beauchamp & Childress, Reference Beauchamp and Childress2019). In the case of COVID-19, more formally known as the 2019 novel coronavirus (Li et al., Reference Li, You, Wang, Zhou, Qiu, Luo and Ge2020), we argue that the criterion of novelty has been met. Regarding uncertainty, one study explored uncertainty facing nurses in the management of emerging infectious diseases, hence meeting the criterion of uncertainty (Lam, Kwong, Hung, & Chien, Reference Lam, Kwong, Hung and Chien2020). Park discusses ambiguity as it relates to the applicability of laws against the backdrop of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) (Park & Skoric, Reference Park and Skoric2017). Moreover, the uncertainty of communication during a novel pandemic threat has been discussed (Han et al., Reference Han, Zikmund-Fisher, Duarte, Knaus, Black, Scherer and Fagerlin2018). Thus the ambiguity criterion has also been met. Finally, moral questions and dilemmas are prominent when emerging infectious diseases arise, such as Ebola (Thompson, Reference Thompson2016) and COVID-19 (Haslam & Redman, Reference Haslam and Redman2020). Hence the moral conflict criterion has also been met. In summary, Beauchamp and Childress (Reference Beauchamp and Childress2019: 11) discuss the applicability of their framework in situations characterized by infectious disease, noting that “threats to public health that require the restriction of liberty through forcible isolation or quarantine and threats to innocent individuals that can be mitigated or eliminated through warnings that breach patient confidentiality” inherently create conflict among the ethical principles. When these principles conflict, the authors suggest that specification and balancing be applied to resolve the conflict rather than some automatic a priori ranking of principles or rights. They also recognize that several derivative rules emerge from this framework, such as confidentiality and privacy. Finally, we consider the bioethical principle of justice in two manners: distributive, or the fair distribution of outcomes (e.g., rewards, punishment) controlled by management decisions (Cropanzano, Bowen, & Gilliland, Reference Cropanzano, Bowen and Gilliland2007), and social justice, which recognizes that disease and illness burdens are determined by human biology and social forces (Alsan, Westerhaus, Herce, Nakashima, & Farmer, Reference Alsan, Westerhaus, Herce, Nakashima and Farmer2011).

Critics would argue that biomedical ethics places a higher priority on individual values over communal values and is not suited for responding to moral issues in public health (Abbasi, Majdzadeh, Zali, Karimi, & Akrami, Reference Abbasi, Majdzadeh, Zali, Karimi and Akrami2018). Beauchamp and Childress (Reference Beauchamp and Childress2019: 11) write, “We do not ignore social responsibilities and communal goals, they are not always trumped by individual rights such as the rights to respect for autonomy, privacy, and confidentiality, as is clear in Principles of Biomedical Ethics Chapters 4–8.” Specifically, examples included in Principles of Biomedical Ethics are infectious disease examples, such as quarantine. Nor is our focus exclusively on the state; rather, it is also on organizations that exist within the constraints of federal and state law. We propose in this article to use biomedical ethics as a cornerstone of our ethical framework but expand the four principles, given the critiques of the applicability of biomedical ethics.

Public Health Ethics

Given that our focus is not the individual health care practitioner nor society overall but the organization, consisting of individuals, groups, and community, we look to public health ethics to expand our characterization beyond bioethics. Importantly, public health focuses on the prevention, not the treatment, of disease (Abbasi et al., Reference Abbasi, Majdzadeh, Zali, Karimi and Akrami2018)—promoting prevention is an important and appropriate role for employers and organizations to play in controlling the spread of a pandemic. Upshur (Reference Upshur2002) describes the tension between individual and community rights in public health practice for the prevention of disease.

Organizations have been framed as communities (Cunha, Rego, & Vaccaro, Reference Cunha, Rego and Vaccaro2014). Not all communities are equal; the COVID-19 pandemic differentially impacts women, workers of color, and low-income workers (Kantamneni, Reference Kantamneni2020). Members of marginalized groups regularly confront systems of power in the workplace and outside that “limit their freedom and impede their lives” (Flores, Martinez, McGillen, & Milord, Reference Flores, Martinez, McGillen and Milord2019: 193). The COVID-19 global pandemic has revealed deep and persisting power imbalances among certain groups of people in the United States (Dickson, Reference Dickson2020; Nixon, Reference Nixon2019).

Our framework is specifically designed for applicability in organizational settings embedded in communities in the case of managing ethical issues during epidemics and pandemics. While we begin with the four principles of biomedical ethics, we go on to include the four principles posited by Upshur (Reference Upshur2002) related to public health more broadly: the harm principle, least restrictive means principle, reciprocity principle, and transparency principle. The harm principle is related to nonmaleficence (Beauchamp & Childress, Reference Beauchamp and Childress1994) and recognizes that the only purpose for which power can be “rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community against his will, is to prevent harm to others” (Mill, Reference Mill1859; Upshur, Reference Upshur2002: 102). Relatedly, the least restrictive means principle asks whether the same ends can be achieved in a way that is less restrictive of the liberty of individuals or groups (Childress et al., Reference Childress, Faden, Gaare, Gostin, Kahn, Bonnie, Kass, Mastroianni, Moreno and Nieburg2002; Pugh & Douglas, Reference Pugh and Douglas2016). While there is no consensus definition of the principle (Giubilini, Reference Giubilini2021), it is also related to the bioethical principle of autonomy with regard to imposing the least amount of restriction on individual rights and freedoms (Gostin & Wiley, Reference Gostin and Wiley2016). Upshur’s third principle, of reciprocity, can be defined as “those who bear such burdens to protect the public’s health are supported by society and public agencies and policies” (Upshur, Reference Upshur2002: 102). This principle has been used to resolve tensions between protecting public health and respecting autonomy (Beeres et al., Reference Beeres, Cornish, Vonk, Ravensbergen, Maeckelberghe, Van Hensbroek and Stienstra2018). Upshur’s fourth public health principle, of transparency, demands clarity and accountability in the decision-making process, as well as stakeholder involvement at each stage (Upshur, Reference Upshur2002: 102).

Beyond Upshur’s (Reference Upshur2002) four principles, solidarity is key in the case of addressing infectious disease outbreaks. Solidarity is described as valuing the moral standing of all stakeholders as members of a community and offering them equal respect and dignity (Jennings, Reference Jennings2019). Solidarity is closely related to social justice, recognizing that different groups may experience greater burdens during a pandemic (Rawls, Reference Rawls2005).

Stakeholder Theory

We argue that stakeholders represent more than shareholders. Manuel and Herron (Reference Manuel and Herron2020: 236), writing about corporate social responsibility (CSR) and COVID-19, assert, “Businesses must act to benefit society, protect employees and maintain the trust of their stakeholders during the pandemic.” It has been recommended that stakeholders be actively involved in creating initiatives designed to recover from COVID-19 in an organizational context (Canhoto & Wei, Reference Canhoto and Wei2021). It is well recognized that stakeholder interests may conflict (Friedman & Miles, Reference Friedman and Miles2002). Hence stakeholder salience is a process used to prioritize the interests of conflicting stakeholders (Mitchell, Agle, & Wood, Reference Mitchell, Agle and Wood1997). In the COVID-19 pandemic, Canhoto and Wei (Reference Canhoto and Wei2021) identified these stakeholders as high on salience: customers, employees, and government agencies.

Positive and Negative Rights

The preservation of human rights overall and positive and negative rights underlies our proposed integrated ethical framework. Foldvary (Reference Foldvary and Chatterjee2011) defines a positive right as a duty by others to provide something of benefit to the holder of the right. An employee may request to work from home, but this request is not a duty owed by the employer. A negative right is a duty by others not to be subjected to an action imposed by others. Mandatory quarantine is an example during pandemics (Martins da Silva & Campo-Engelstein, Reference Martins da Silva and Campo-Engelstein2021). Caplan (Reference Caplan2013: 2667), in writing about the right not to vaccinate, opines, “Liberty in regarding vaccination ends at the start of a vulnerable person’s body.” This notion reflects the sentiment of the harm principle posited by John Stuart Mill (Reference Mill1859/2003), in which individual liberties can be restricted to protect the individual and others. Circling back to issues related to power, Matose and Lanphier (Reference Matose and Lanphier2020: 170) caution decision makers using the example of social distancing to “ensure that the burdens and benefits of social distancing are equitably distributed.”

At the intersection of positive and negative rights are legal considerations, which are beyond the scope here, but as an illustration, consider employer mandates for COVID-19 testing before being allowed to return to the workplace. Such mandates intersect with CDC guidelines, Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) policies, and the Americans with Disabilities (ADA) Act. Rubin (Reference Rubin2020: 2016) argues that employer mandates comply with the business necessity standard of the ADA according to EEOC guidance. Pendo, Gatter, and Mohapatra (Reference Pendo, Gatter and Mohapatra2020) explore the tensions between disability rights law and COVID-19 mask mandates as one of the challenges confronting the fair application of organizational policies on differently abled workers who assert that they have a disability.

ETHICAL DECISION-MAKING AND THE EPIDEMIOLOGICAL TRIAD AT WORK

The epidemiological triad can provide a framework for organizational leaders to analyze data and to design and evaluate interventions amid an infectious, communicable disease. Table 2 illustrates ten common workplace ethical challenges confronting decision makers in organizations, organized by intervention area of the epidemiological triad in the workplace. For each scenario, we identify what core ethical principle is represented and the related decision-making issues.

Table 2: Ethical Decision-Making Issues for Pandemic Response in the Workplace

Host

A variety of ethical principles apply to workplace considerations related to host factors. Nonmaleficence, the ethical and legal duty to avoid harming others, is a starting point to consider the use of PPE (Beauchamp & Childress, Reference Beauchamp and Childress2013). Nonmaleficence is captured by the saying “First do no harm” (Saunders, Reference Saunders2017: 552). For example, the use of PPE should be for the benefit of workers and customers, as a way to continue operating without causing any significant adverse effect or harm by unnecessary exposure to the virus. The New York Times (Scheiber & Conger, Reference Scheiber and Conger2020) reports how workers at Amazon, Instacart, and Whole Foods are striking over concerns about a lack of safety regarding the work environment. Among health care workers, PPE shortages have been pinpointed (Wang, Zhou, & Liu, Reference Wang, Zhou and Liu2020). As we move toward reopening our economy in a post-COVID-19 setting, workers have shown an expectation of being given proper protection by their employers. Decision makers will have to contend with how to do this both safely and realistically and in a manner that ensures equity and justice.

Upshur’s fourth public health principle of transparency bears relevance in situations involving insufficient resources or rationing with respect to infectious disease control measures (Jeffrey, Reference Jeffrey2020). An illustrative example is what will be the distribution approach if there is scarcity with regard to PPE and supplies are limited. How will scarce protective resources be allocated to ensure equity in distribution when demand spikes? In these instances, it is essential that relevant stakeholders know how decisions are made and by whom. Stakeholder theory suggests that, ideally, the relevant stakeholders be included in the planning and decision-making process and, if rationing becomes a reality, that a clear and fair allocation procedure be communicated and followed (Emanuel et al., Reference Emanuel, Persad, Upshur, Thome, Parker, Glickman, Zhang, Boyle, Smith and Phillips2020).

As for beneficence, a growing body of empirical evidence documents the benefits associated with specific workplace interventions. For example, a pilot RCT in a workplace setting empirically demonstrated a modest yet statistically significant effect in decreased workplace infections over a ninety-day period (Stedman-Smith et al., Reference Stedman-Smith, DuBois, Grey, Kingsbury, Shakya, Scofield and Slenkovich2015). Hence, if there is a known benefit, then the decision becomes how to incorporate this empirically validated information into organizational policy, procedures, programs, and budgets. Research demonstrates that access to specialized workplace training related to infectious disease results in reduced anxiety (Wong, Wong, Lee, & Goggins, Reference Wong, Wong, Lee and Goggins2007). If the training was evaluated by the workers to be inadequate, then there were increases in burnout, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and longer perceived risk of infection (Maunder et al., Reference Maunder, Lancee, Balderson, Bennett, Borgundvaag, Evans, Fernandes, Goldbloom, Gupta, Hunter, Hall, Nagle, Pain, Peczeniuk, Raymond, Read, Rourke, Steinberg, Stewart, VanDeVelde-Coke, Veldhorst and Wasylenki2006). It has been recommended that psychological well-being be advanced by implementing occupational health policies or support systems (Brooks, Dunn, Amlôt, Rubin, & Greenberg, Reference Brooks, Dunn, Amlôt, Rubin and Greenberg2018). The promotion of well-being is the cornerstone of beneficence. Furthermore, this approach can bolster transparency, as it can provide a rationale and information to workers and relevant stakeholders about other policies and programs that have been implemented.

Vulnerable stakeholders, such as low-wage employees and those with disabilities, deserve particular attention during a pandemic. While persons with disabilities are not automatically more susceptible to the virus, they may have greater risk due to underlying chronic medical conditions or circumstances that make it more challenging for them to social distance (i.e., reliance on caregivers) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020a). When considering the host aspect of the triad, it is important to remember that not all stakeholders have equal risk in a pandemic. Work-based policies, programs, and interventions should be sensitive to this disparity and develop reasonable accommodations and priorities to address them. If vulnerable populations are overly burdened by the changes made, then the reciprocity and solidarity principles ask us to provide additional support and benefit to these communities.

Environment

The first environmental decision point comes in the form of whether and how a workplace will continue to operate in a pandemic. There is an ethical obligation to provide a safe, positive working environment that avoids harm to workers (Morrison, Reference Morrison2019). Furthermore, if a worksite remains open, can this be a positive environment, partially realized by what Morrison describes as having a “climate of caring” (52). If a worksite cannot operate safely during a pandemic, worker financial stability becomes of paramount concern, grounded in the ethical principles of reciprocity and justice. Issues around pay structures and access to employer-sponsored benefits, ranging from health insurance to sick leave (paid or unpaid), are workplace environmental factors controlled by management and ideally overseen by the board of directors. In the case of an infectious disease with stay-at-home orders, such as with COVID-19, workers with paid sick days (PSD) will be able to stay home with the least amount of financial harm if their employers allow them to access the PSD benefit without duress. Reportedly, one in four (24 percent) of US employees do not benefit from PSD, which is inversely associated with wages. Given the difference in offering PSD based on wages, this compensation philosophy interferes with the autonomy of workers and could violate the harm principle via workers’ decisions about going to work or staying home based on their health status, transmission status, caregiver status, and the economic impact of that decision (DeSilver, Reference DeSilver2020).

Not all jobs are designed to allow workers to follow stay-at-home guidelines and continue to receive a steady income from employment because the job cannot be done remotely or via leveraging technology, such as being a food delivery driver or service professional, such as a hair stylist, massage therapist, or public transit worker. There are gender and racial/ethnic disparities related to this divide. One study found that nearly one in three (28 percent) of male workers, compared to a bit more than one in five (22 percent) of female workers, work in a job that enables them to telecommute (Alon, Doepke, Olmstead-Rumsey, & Tertilt, Reference Alon, Doepke, Olmstead-Rumsey and Tertilt2020). Furthermore, a disproportionate share of Black and Hispanic workers are employed in roles that do not allow them to work from home (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019). The ethical principles of justice, reciprocity, and solidarity ask organizations to develop alternative safety measures for workers whose jobs are not suitable for remote work.

Beyond the impact of the worker, the environment also poses risks on customers and companies in the value chain. Identifying and mitigating these risks are based is the principle of nonmaleficence. In the case of communities like Las Vegas (Creswell, Reference Creswell2020) or Orlando, whose economic ecosystems are linked closely to tourism and theme parks, such as Disney World, not only were nearly twenty-eight thousand workers laid off (Russon, Reference Russon2020) due to closures but the decision to close the theme parks and other businesses, such as restaurants, had a negative impact on agricultural workers, who “were left with hundreds of millions of produce with no available market” (Campbell & McAvoy, Reference Campbell and McAvoy2020: 165). As an example of both solidarity and least restrictive means, Disney Parks and Resorts US set up on-site vaccination centers (Russon, Reference Russon2021). As a major employer in the Orlando community, Disney must prioritize the health and safety of the local community. By promoting vaccination, it can protect the health of its workforce but also influence local visitors to feel safe to return to its theme parks, restaurants, and shopping centers. Yet the other side of the equation is the fact that at the beginning of the pandemic, Disney forecasted that it may lose $175 million due to COVID-19 (Creswell, Reference Creswell2020).

All these workplace examples point to the reality articulated by Lewnard and Lo (Reference Lewnard and Lo2020: 632) when discussing the impact of public health measures to address COVID-19, as follows: “Interventions might pose risks of reduced income and even job loss, disproportionately affecting the most disadvantaged populations; policies to lessen such risks are urgently needed.” These realities exist within the shadows of well-documented socioeconomic injustices committed in the name of public health against the most vulnerable (Kass, Reference Kass2001). As such, organizational decision makers must consider the erosion of autonomy, equity, and justice in their actions, knowing that stakeholders exist within and beyond the walls of their organizations.

Agent

Ethical discussions involving the agent may endeavor to address the root cause of the pandemic, in this case, the SARS-CoV-2 virus. As workplaces set specific policies around vaccination, testing, and quarantine, issues related to the ethical principle of least restrictive means, transparency, and stakeholder theory emerge. Related to infectious disease control, Giubilini (Reference Giubilini2021: 7) writes the following:

In the case of vaccination, the least restrictive alternative could then also be understood as the alternative that imposes the lowest risk of harm possible at the population level, compatibly with achieving herd immunity.

Nudging policies are examples of a least restrictive way to promote regular testing and vaccination uptake rather than mandatory policies (Giubilini, Reference Giubilini2021). Clarifying a set of implementation, privacy, and exemption standards would also serve to mitigate the concerns of an employment-based vaccine mandate. Additionally, Balfe (Reference Balfe2015) recommends that managers and others confer with human resources to maintain the confidentiality of any worker who is suspected or confirmed to be infected with a communicable disease. Fairchild et al. (Reference Fairchild, Haghdoost, Bayer, Selgelid, Dawson, Saxena and Reis2017) acknowledge the balancing act between public health surveillance and the protection of individual autonomy—leaning toward protecting the public while at the same time not abusing or misusing individual privacy protections (Fairchild et al., Reference Fairchild, Haghdoost, Bayer, Selgelid, Dawson, Saxena and Reis2017).

If a workplace is deemed essential or able to reopen following the initial stages of a pandemic, employers must recognize that they could be creating opportunities to promote the transmission of a disease—which tests their obligations under both the principle of nonmaleficence and the harm principle. Additionally, only the federal, state, county, or municipal government can mandate quarantine of individuals (Balfe, Reference Balfe2015). Employers may request that a worker confirmed to have a communicable infectious disease take leave, which could be paid or unpaid. The worker’s job may be held or not. Both decisions have financial and certainly nonfinancial costs and benefits for both the worker and any dependents. Creating negative consequences of quarantining likely would have the downstream impact of workers avoiding quarantining when they should, thereby creating unnecessary risks for the workplace community. As such, leaning on the ethical principles of reciprocity and solidarity may avoid unintended consequences. Employers may need to consider how to encourage or reward voluntary quarantining and notices of exposure.

In the case of COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2 is the infectious disease agent. Among the epidemiological triad, organizational decision makers have greater control and influence over host and environment factors than agent factors. Yet, several factors increase the probability that infectious disease agents will invade human hosts, including poverty, deforestation, climate change, travel, and population density (Nii-Trebi, Reference Nii-Trebi2017). In short, “human actions can also influence the subsequent evolutionary dynamics in these EID (emerging infectious disease) systems” (Rogalski, Gowler, Shaw, Hufbauer, & Duffy, Reference Rogalski, Gowler, Shaw, Hufbauer and Duffy2017: 1). It beyond the scope here to detail the emerging business, public health, and environmental ethics literature regarding climate change, but it is increasingly recognized that organizations contribute to climate change (Dahlmann, Branicki, & Brammer, Reference Dahlmann, Branicki and Brammer2019) and as such could be causing harm to others (principle of nonmaleficence). A commitment to limiting carbon emissions or moving toward zero waste could be an employer-based investment in preventing future outbreaks.

A final consideration is the reality that the federal government is a major funder of basic research, and even vaccine development is financed by the US government (National Science Foundation, 2020). As an example, $13 billion in federal funding was committed to financing COVID-19 vaccine developers (National Institutes of Health, 2020). As such, corporate tax avoidance is an ethical issue (Dowling, Reference Dowling2014) that may have a downstream impact on critical funding, first, to identify, second, to prevent, and third, to treat workers and other stakeholders in the case of infectious disease. Research is critical to mitigating disease spread; providing funding for this work through appropriate tax remittance is an act of solidarity.

Business Interests

We recognize that the traditional epidemiological triad, when applied in a workplace setting, is experienced within the broader context of business interests and sustainability. It is evident that organizations have business interests with respect to communicable infectious disease. Stedman-Smith and colleagues (Reference Stedman-Smith, DuBois, Grey, Kingsbury, Shakya, Scofield and Slenkovich2015: 374) articulate these interests by describing the impact of infectious disease at work as including

the costs of medical intervention for self-insured organizations, rising health insurance premiums, absenteeism, employee replacement, reduced productivity due to working while ill, increases in overtime from higher workloads carried by healthy employees on the job, and reduced morale.

As noted, these impacts only deal with the infectious disease itself and not with subsequent decisions related to quarantine; isolation; mandatory testing; mandatory vaccination; mandatory contact tracing; and decisions to close, curtail, and reopen business operations.

Business interests must be separated from greed. Others evaluate the behavior of agents based on the perceived harm that the agent is willing to enact to acquire resources (Helzer & Rosenzweig, Reference Helzer and Rosenzweig2020). The perceived harm relates to the ethical principle of nonmaleficence. Stakeholder theory is critical given that pandemics like COVID-19 may impact businesses and workers along the value chain, from the initial source to the end user of the product, good, or service. As shown in both Figure 1 and Table 2, there are competing priorities that must be addressed by organizational decision makers to inform actions, while knowing that these actions may cause harm to stakeholders. Regarding infectious disease, this harm may range from financial loss to privacy infringement but extend all the way to include complex health implications up to and including death.

EMPLOYER STRATEGY

Building on the aforementioned identified challenges, we continue using the epidemiological triad and the integrated ethical framework to propose a guide for organizational leaders to develop a strategic approach to their pandemic preparation and response. Each sector of the epidemiological triad holds opportunities for businesses to intervene to mitigate risks and minimize the spread of pandemics, while simultaneously prioritizing an ethical response that honors their relevant stakeholders’ needs. This framework encourages decision makers to identify the risks they have, explore evidence-based strategies to resolve those risks, recognize the ethical concerns that may arise, and then, finally, examine how the strategies can be altered or adjusted to mitigate the ethical concerns. Geppert (Reference Geppert2020) provides a guide to considering how to address some of the ethical challenges encountered. First, focus is the first difference (i.e., individual vs. the group). Second, the tools used to promote change are more different and wide-reaching in pursuing communitarian versus individual aims, such as legal, political, and cultural factors. Third, the ethical principles guiding decisions are different in that autonomy takes center stage in American medical ethics compared to nonmaleficence and justice, especially during pandemics. Fourth, the decision maker should be different, argues Geppert, moving away from the individual provider to a group-based decision-making structure, such as a committee. These groups ought to be supported by evidence-based protocols. If these structures are in place, then the values of consistency, transparency, and fairness are more likely to be realized. We wholeheartedly agree with Geppert that during pandemics, committees should be the decision-making authority, not individual clinicians. Yet, in organizations, decision-making occurs at multiple levels: individual supervisors and groups of individuals, such as committees, councils, and task forces. Furthermore, in organizations, ethical leadership occurs at multiple levels. As an example, ethical leadership can be defined as

the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making (Brown, Treviño, & Harrison, Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005: 120).

As shown, ethics occurs at the level of the individual, the group, and the organization when considering the overall context. Each of these levels, and the power imbalance and tensions between their respective motivations, must be considered when designing interventions to address the ethical implications.

Ethical Scaffold: A Foundation for Employer Readiness

This intervention framework is essential in assisting organizational decision makers to intervene under difficult circumstances in the workplace. What follows is a checklist of business, human resources, supply chain, and financial policies informed by our integrated ethical framework for leaders of decisions and actions to consider during times in which an infectious disease is having an impact on numerous stakeholders. This checklist, given in Table 3, recognizes the balancing required among organizational decision makers and the consideration of stakeholders beyond the organization. This balancing entails considering multiple factors of concern articulated by diverse stakeholders, as “efforts on containment, suppression and mitigation are not only needed with regard to the virus but also with regard to possible adverse societal and economic consequences” (Burdorf, Porru, & Rugulies, Reference Burdorf, Porru and Rugulies2020: 230).

Table 3: Employer Tool/Checklist

Intervention: Host

Employers need to plan for and adopt clear policies and procedures to emphasize disaster preparedness, including for infectious disease, to minimize harm to persons and communities. This is particularly critical for work settings that stay open during an outbreak. Any of these responses can be met with varying impacts by stakeholder groups to promote transparency and ensure justice. As such, employers can use available best practices, for example, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (2020), part of the CDC, offers a number of resources for employers to mitigate the spread and prioritize the safety of workers.

We use the restaurant industry as an illustrative example to bring these concepts to light. This industry clearly has both internal and external stakeholders. Internal stakeholders are coworkers. External stakeholders include restaurant customers, suppliers, friends and family of food workers, and any person in human-to-human contact with food workers. Customers are key stakeholders. However, conflicts may arise between different stakeholders (Ferrell, Reference Ferrell2004). Yet, consumers may evaluate products/services on matters related to how employees are treated, including unsatisfactory safety procedures (Brunk, Reference Brunk2010).

In a survey on infectious disease in the restaurant industry, involving 491 workers in 391 restaurants across nine states, nearly two out of three (60 percent) food workers reported working while feeling ill. Some of the reasons for doing so included concerns about coworkers being short staffed and job loss; another was no sick leave policy—a clear violation of the reciprocity principle. This was the top reason reported by 43 percent of the survey respondents. Another reason was that they did not feel too bad, and they believed they were not contagious. An alarming finding is that nearly one in five (19.9 percent) of the respondents reported working one or more shifts while vomiting or experiencing diarrhea. In most cases, it was the food worker’s decision to work while feeling ill. However, in nearly one in ten (7 percent) of the cases, it was the decision of management (Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Green, Norton, Frick, Tobin-D’Angelo, Reimann, Blade, Nicholas, Egan, Everstine and Brown2013).

These ethical concerns can be mitigated through the creation of a business model and strategic plan that emphasize preparedness and stakeholder involvement in decision-making. It is critical that as these plans are developed, organizational leaders enlist input and engagement from and promote the buy-in of all impacted workers and relevant stakeholders. This will preserve autonomy and transparency.

Intervention: Environment

Environmental interventions range from business policy, often aligned with federal, state, and municipal law, to the physical layout of the workplace. As an example, the US Chamber of Commerce (2020: 1) issued guidance recommending that businesses “coordinate with state and local health officials.” Each of these policies must be implemented from the perspective of least restrictive means.

Workplaces that decide to close operations, if it is not safe to remain open, have other important considerations. For example, Amazon, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and Twitter, during COVID-19, asked their workers to work from home (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton2020). This is an example of a mandatory quarantine imposed by the organization, not the government. This organizational decision sets forth a host of decisions that must be made by the individual worker, ranging from how to maintain productivity to eligibility for compensation and benefits. School systems across the world, from Bahrain (Al Amir, Reference Al Amir2020) to Japan (Rich, Dooley, & Inoue, Reference Rich, Dooley and Inoue2020), suspended classes during COVID-19, in some cases, for weeks. This organizational decision, too, sets forth a host of challenges for working parents, from arranging childcare to continuing to be productive at work. In one small study, almost half (42 percent) of parents with children bore financial consequences resulting from enforced home quarantine targeting schoolchildren during the H1N1 pandemic in 2009 (Kavanagh et al., Reference Kavanagh, Mason, Bentley, Studdert, McVernon, Fielding, Petrony, Gurrin and LaMontagne2012).

These organizational decisions also have an impact on customers and suppliers. As such, stakeholder theory is animated in these decisions with no formulaic way to prioritize stakeholders. The prioritization of stakeholders was featured in a USA Today news story (Bagenstose, Chadde, & Wynn, Reference Bagenstose, Chadde and Wynn2020), which read, “Coronavirus closed Smithfield and JBS meatpacking plants. Many more at risk. Operators may have to choose between worker health or meat in stores.” Kaptein (Reference Kaptein2017), in his work on ethical struggle, suggests that citizens living in the vicinity of an organization are stakeholders. This consideration was incorporated in the CDC’s and OSHA’s Interim Guidance for Meat/Poultry Processing Workers and Employers, which advised that “critical infrastructure workers may be permitted to continue work following potential exposure to COVID-19, provided they remain asymptomatic and additional precautions are implemented to protect them and the community” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020b: 1).

Any decision made to stop or limit business operations can create a downstream financial impact on both the business and its workers. It is of important concern that whatever response is decided upon could be unjust or exacerbate existing socioeconomic disparities among the workforce—creating a violation of the solidarity principle. As such, organizations should work to ensure diverse representation on decision-making and oversight boards and relevant committees. Alternative responses should be evaluated based on equity to ensure that solutions are fair at all segments of the pay scale and for all job classes. Focusing on reciprocity and solidarity can ensure greater compliance with restrictive policies by creating incentives or rewards to quarantine rather than financial consequences.

Intervention: Agent

Phua (Reference Phua2013: 2) describes the reality that the “control of infectious diseases necessitates public health interventions that often infringe on the rights of individuals.” As such, Phua highlights the need to recognize the ethical dilemmas involved. For example, contact tracing is a public health intervention in which the names and addresses are gathered of everyone in physical contact with an individual who tests positive for an infectious disease or is suspected of being positive. This clearly raises issues related to anonymity, confidentiality, privacy, and, possibly, stigmatization.

Testing and contact tracing are intervention tools designed to decrease or eliminate the spread of an infectious disease from person to person. Both tools rely on an individual’s data. For contact tracing, the identities of individuals must be known from a public health perspective because what may follow once the individual is identified is a referral for treatment or a recommendation of self-, employer-, or public health authority–mandated isolation and quarantine.

Employers also have a risk that during a pandemic, whatever responses they make could erode both employee and public trust and loyalty. As such, proactive measures could be taken to find ways to contribute to research and development around vaccines and treatment. Employers can incorporate these endeavors into existing CSR initiatives or foundation/fundraising efforts.

IMPLICATIONS

With a shifting focus driven by these ethical challenges and responses, we anticipate a new opportunity to focus collaboration between the public health sector and employers. Traditional public health departments need to see the business community as a partner in addressing infectious disease. Organizing bodies like chambers of commerce, small business advisory councils, and local/national public health departments should prioritize these partnerships for planning, resource sharing, and best-practice dissemination.

Future research in this area should explore how the epidemiological triad in the workplace model and its tools can be practically deployed in an organizational environment. This can and should begin in an applied manner, while working through strategic governance. Organizations should begin including epidemiological risks in their strategic planning and risk assessment processes. Training and guiding organizational leadership through the concepts and intervention points identified in the previous processes will be a key first step. However, assessing their learning, receptiveness, and ability to apply the ethical principles will be critical in the evolution of our understanding of the model and related strategies. Furthermore, this should be explored in a variety of different settings (essential, family business, food production, service sector) to develop more nuanced approaches. This work can also be applied to other workplace challenges and opportunities related to health and safety, ranging from workplace wellness programs to industrial hygiene/ergonomics. This work can not only support decision-making around initial responses to pandemic outbreaks but also guide the reopening and return to normalcy.

Finally, as we consider policy implications—both in the short and long term—we argue that legislative decisions must support businesses in quickly alleviating the tension between business interests and public health needs. A Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)-style response team should be developed by Congress to enact emergency legislation like the CARES Act on a targeted, temporary basis—in quicker fashion, ready to deploy earlier, at the first signs of infectious spread. This should also include a version of the Defense Production Act (DPA)—asking businesses to pivot and begin manufacturing needed supplies. While some employers make this choice voluntarily, a supportive policy landscape can encourage broader and more rapid responses. Regarding business policy, senior leaders and boards of directors may need to add board seats for those with competence in epidemiology and ethics, not only seats for attorneys and other corporate leaders. Novel emerging infectious diseases may necessitate novel theoretical models and ways of conducting business, because this is not “business as usual,” and it is likely we shall return to a “new normal,” not an “old normal.”

CONCLUSION

The emergence of pandemics like COVID-19 forces us to examine the role of employers in protecting workers, customers, suppliers/vendors, and the community at large. By merging a foundational understanding of epidemiological theory with an integrated ethical framework to ground employer decision-making, we can give structure to a complex and vexing problem. Employers must balance the health and well-being of their employees, customers, and even suppliers/vendors along with the firm’s long-term sustainability. This delicate arrangement can be strengthened when examined through a lens tempered by ethical inquiry. We can and should anticipate future public threats that may challenge employers. By providing guidance, resources, and policy-based recommendations, we can bolster their preparations and equip them for sound, ethical decision-making.

Michele Thornton (michele.thornton@oswego.edu, corresponding author) is an assistant professor of health services administration in the School of Business at SUNY Oswego. She completed her MBA at DePaul University in Chicago and her doctoral degree at the University of Illinois in Chicago–School of Public Health. In addition to teaching, Thornton consults with employers on benefit design and strategic initiatives. Michele’s research focuses on health insurance, disparities, and ethics. She has published this work in both academic and industry journals and presents at national and international conferences.

William “Marty” Martin is a professor in the Department of Management and Entrepreneurship in the Driehaus College of Business at DePaul University. His research focuses on business ethics, public health, and health management. He teaches in business schools, public health schools, and medical schools. His education and training inform his research and teaching. He is educated and trained as a clinical psychologist and epidemiologist. Prior to joining the professoriate, he worked in senior HR roles at a variety of organizations.