Over the last two decades, we have witnessed the rise of a new neoliberal form of capitalism that is dominated by institutional investors, such as pension funds and asset managers (Davis, Reference Davis2009; Useem, Reference Useem1996). This rise has been accompanied by private and public regulatory efforts to encourage corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the consideration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues by financial actors (Giamporcaro & Gond, Reference Giamporcaro and Gond2016; Marti & Scherer, Reference Marti and Scherer2016; Slager, Gond, & Moon, Reference Slager, Gond and Moon2012). In this context, the field of socially responsible investment (SRI) is a highly relevant domain in which to explore how national governments can experiment with and mobilize new forms of interventions (Djelic & Sahlin-Andersson, Reference Djelic and Sahlin-Andersson2006; Gilbert, Rasche, & Waddock, Reference Gilbert, Rasche and Waddock2011; Kourula, Moon, Salles-Djelic, & Wickert, Reference Kourula, Moon, Salles-Djelic and Wickert2019).

However, we know little about how governments promote the adoption of CSR within the context of financial markets. Moving beyond the perspective that CSR studies do not consider the role of government, a growing stream of studies investigate the relationship between CSR and government (Knudsen & Moon, Reference Knudsen and Moon2017; Kourula et al., Reference Kourula, Moon, Salles-Djelic and Wickert2019). Despite its contribution to the analysis of national CSR policies (Albareda et al., Reference Albareda, Lozano, Tencati, Midttun and Perrini2008; Knudsen, Reference Knudsen2018; Vallentin, Reference Vallentin2015) or CSR-government relationships (Gond, Kang, & Moon, Reference J.-P, Kang and Moon2011; Knudsen, Moon, & Slager, Reference Knudsen, Moon and Slager2015), this research has little to say about how new governmental CSR interventions change or interact, or how financial market contexts shape such interactions. Overlooking how governmental interventions change and interact prevents scholars from analyzing their systemic impact, and thus obfuscates effective CSR policy design (Knudsen & Moon, Reference Knudsen and Moon2017; Schneider & Scherer, Reference Schneider and Scherer2019). In addition, neglecting finance as a “regulatory space” (Power, Reference Power, Huault and Richard2012: xiii) can misrepresent governmental capacities to regulate CSR, given how financial markets weigh on governmental choices and policies (Scherer, Rasche, Palazzo, & Spicer, Reference Scherer, Rasche, Palazzo and Spicer2016).

In this article, we address these blind spots by studying how governmental CSR interventions have evolved and interacted within the French financial market. We build on insights from the literature on CSR and government (Dentchev, Haezendonck, & van Balen, Reference Dentchev, Haezendonck and van Balen2017; Knudsen & Moon, Reference Knudsen and Moon2017; Kourula et al., Reference Kourula, Moon, Salles-Djelic and Wickert2019; Schneider & Scherer, Reference Schneider and Scherer2019), as well as Osborne and Gaebler’s (Reference Osborne and Gaebler1992) nautical analogy of the state engaging in steering and other actors in rowing, which is a central reference point in the literature on regulative capitalism (Braithwaite & Drahos, Reference Braithwaite and Drahos2000; Denhardt & Denhardt, Reference Denhardt and Denhardt2000; Levi-Faur, Reference Levi-Faur2005). Steering interventions relate to “governing by setting the course, monitoring the direction and correcting deviations from the course set” (Crawford, Reference Crawford2006: 453) and are regarded as governmental actors’ prerogatives in a neoliberal context. Rowing interventions, on the other hand, relate to the enterprise, products, and service provision and are usually handled by private actors (Osborne & Gaebler, Reference Osborne and Gaebler1992).Footnote 1

Our empirical analysis focuses on the role played by a range of French governmental actors (e.g., the state and state-owned investment groups) in the development of the national SRI market between 1997 and 2017, through interventions that targeted public companies as well as institutional investors. SRI practices involve the consideration and inclusion of traditional nonfinancial—otherwise known as ESG—information into investment decision-making processes (Eurosif, 2018; Kurtz, Reference Kurtz, Crane, McWilliams, Matten, Moon and Siegel2008), with the purpose of enhancing public company CSR behavior and investment returns. With €920 billion assets under management (AuM) subject to the integration of ESG criteria within investment decisions, France is one of the most dynamic European SRI markets (Eurosif, 2018) and is characterized by the role of the state in the development of its market (Arjaliès & Durand, Reference Arjaliès and Durand2019; Crifo, Durand, & Gond, Reference Crifo, Durand and Gond2019).

Drawing on historical and longitudinal sources of secondary data and seventy-eight semistructured interviews, we analyze all of the governmental CSR interventions that occurred as the French SRI market developed between 1997 and 2017 and show how these interventions redefined the distribution of roles between governmental and private actors. That is, beyond classical forms of state-led steering and private, actor-led rowing (Braithwaite & Drahos, Reference Braithwaite and Drahos2000; Levi-Faur, Reference Levi-Faur2005), we abductively (Ketokivi & Mantere, Reference Ketokivi and Mantere2010) identify new combinations of steering and rowing that blur the private/state dichotomy and allow for deeper, low-cost forms of state control of business conduct. Apart from regulatory steering—which is the use of (hard) regulation without planning sanctions for noncompliance—we identify two other modes of intervention: delegated rowing—the mobilization of state-controlled organizations to change market actor behavior—and microsteering—the mobilization of technologies of governance, such as labels or standards, to micromanage market actor behavior.

Adopting a social mechanism approach (Stinchcombe, Reference Stinchcombe1991), we then analyze how interactions between modes of intervention become “transformed into some kind of collective outcome” (Hedström & Swedberg, Reference Hedström and Swedberg1998: 23). Here, we identify two main mechanisms that we refer to as layering and catalyzing. Layering relies on the complementarities between interventions and explains how the accumulation of regulations in the marketplace supported the creation of new state-owned actors and allowed them to experiment with new governance tools. The catalyzing mechanism relies on the alignment of interventions and explains how coexisting interventions produce targeted pressure points, which extend regulatory depth and breadth and ultimately provoke a major shift in the market as well as SRI mainstreaming.

By showing how governmental CSR interventions interacted within the French financial market, our analysis offers a threefold contribution to theory. First, we identify new modes of governmental CSR interventions that recombine steering and rowing so that governments can enhance their influence, even though they operate within a neoliberal order. Second, we theorize two social mechanisms that explain how governmental CSR interventions interact and thus clarify how multiple interventions can be effectively orchestrated. Third, we highlight how governments mobilize financial intermediaries—such as public pension funds—to influence other market actors and identify some of the necessary market-related conditions for the deployment of effective governmental CSR interventions.

GOVERNING CSR: CONCEPTUAL BACKGROUND

Recognizing and Accounting for Governmental CSR Interventions

Although CSR has traditionally been defined as corresponding to voluntary business activities (Barnett, Hartman, & Salomon, Reference Barnett, Hartmann and Salomon2018; Carroll, Reference Carroll, Crane, McWilliams, Matten, Moon and Siegel2008), where CSR means “going beyond obeying the law” (McWilliams & Siegel, Reference McWilliams and Siegel2001: 117), a growing body of literature has shown that national governments can, and do, play a role in the adoption and formation of CSR behavior (Dentchev et al., Reference Dentchev, Haezendonck and van Balen2017; Matten & Moon, 2004; Moon & Vogel, Reference Moon, Vogel, Crane, McWilliams, Matten, Moon and Siegel2008). This move towards a “related perspective” (Knudsen & Moon, Reference Knudsen and Moon2017: 15) that investigates how CSR and governmental activities overlap is consistent with legal scholars’ view that CSR not only happens beyond law but also through law (McBarnet, Reference McBarnet, McBarnet, Voiculescu and Campbell2007; Zerk, Reference Zerk and Zerk2006), notably through national procurement policies (McCrudden, Reference McCrudden2007). In line with Schneider and Scherer (Reference Schneider and Scherer2019), we define governmental CSR interventions as “the system of public goals, strategies, laws, regulations, incentives, and funding priorities that governmental agencies, or their representatives, implement to motivate, facilitate and shape the CSR activities of business firms” (1148). In contrast to these authors, however, we refer to interventions rather than policies to stress that governmental actions in the CSR realm often take the form of soft, rather than hard, regulations that aim at nudging, as opposed to commanding, private actors.

Initial studies of “CSR and government” have established the existing range of governmental CSR interventions. One stream of research has documented public policies related to CSR in different regions of the world (Albareda et al., Reference Albareda, Lozano, Tencati, Midttun and Perrini2008; Knudsen et al., Reference Knudsen, Moon and Slager2015). For example, Steurer, Martinuzzi, and Margula (Reference Steurer, Martinuzzi and Margula2012) showcase the differences in themes and instruments of public policies focused on CSR across multiple European Union (EU) member states and find that western member states (e.g., Denmark) are relatively more active than Eastern European countries (e.g., Poland) in the CSR regulatory space. On the other hand, Knudsen et al. (Reference Knudsen, Moon and Slager2015) analyzed changes in CSR policies in twenty-two EU member states and identified some convergence of CSR-related public policies within specific regions. To explain this cross-national diversity and to document governmental CSR interventions, a second stream of studies has developed typologies of the processes by which government and private actors interact around CSR (e.g., Fox, Ward, & Howard, Reference Fox, Ward and Howard2002; Gond et al., Reference J.-P, Kang and Moon2011; Steurer, Reference Steurer2010).

Together, this prior research suggests that governments operate as strategic actors in the CSR field (Gond et al., Reference J.-P, Kang and Moon2011; Moon & Vogel, Reference Moon, Vogel, Crane, McWilliams, Matten, Moon and Siegel2008)—especially in Europe (Knudsen et al., Reference Knudsen, Moon and Slager2015). Governments can organize the delegation of CSR activities to private actors (Vallentin & Murillo, Reference Vallentin and Murrillo2012), shape business behavior through a vast repertoire of instrumental means (from financial incentives to endorsements) and modes of interaction (from command and control regulation to pure delegation), or focus on a variety of CSR-related domains (from suppliers’ procurement to corporate reporting and responsible investing).

Explaining How Governmental CSR Interventions Work

Recent research efforts focus on clarifying the assumptions underlying governmental CSR interventions (Knudsen & Moon, Reference Knudsen and Moon2017), as well as the mechanisms by which they produce effects in the business world (Schneider & Scherer, Reference Schneider and Scherer2019). This research does so by incorporating insights from studies of regulatory capitalism (Braithwaite, Reference Braithwaite2011; Levi-Faur, Reference Levi-Faur2005), which find that state authorities still exert considerable power through the multiple regulatory activities they deploy (Wood & Wright, Reference Wood and Wright2015).

Knudsen and Moon (Reference Knudsen and Moon2017) provide a deeper and enriched understanding of governmental CSR policies as embedded within global forces (Polanyi, Reference Polanyi, Polanyi, Arenseberg and Pearson1957), inherited policies and domestic institutions (Knudsen, Reference Knudsen2018; Matten & Moon, Reference Matten and Moon2008), and agential in the sense that CSR policies also result from the deliberate choice of governments to intervene in specific CSR domains. Building on this assumption of an embedded and agential approach to governmental CSR interventions allows us to conciliate the notion that government still matters despite globalization and to conceptualize various modes of governmental CSR interventions. Knudsen and Moon (Reference Knudsen and Moon2017), however, stress the lack of investigation and theorization regarding the interactions among multiple CSR policies that are deployed directly or indirectly by national governments. Prior empirical studies have usually adopted a cross-national comparative design (e.g., Albareda et al., Reference Albareda, Lozano, Tencati, Midttun and Perrini2008) or used ad hoc examples of governmental CSR-related practices to conceptualize typologies (e.g., Gond et al., Reference J.-P, Kang and Moon2011). As a result, this research has little to say about whether and how various governmental interventions in a specific country interact to shape a CSR domain or outcome. In particular, prior studies do not empirically investigate how governments diversify their use of CSR from a form of deregulation (e.g., delegating activities to private entities) to regulation (e.g., interventions that shape the activities of private entities), or even re-regulation (e.g., turning soft laws into mandatory regulations).

Schneider and Scherer (Reference Schneider and Scherer2019) have moved the analysis of “CSR and government” one step further by conceptualizing the mechanisms by which governmental interventions shape market actors’ CSR behavior and specify their boundary conditions. Building on a definition of a social mechanism as “a process in a concrete system, such that it is capable of bringing about or preventing some change in the system as a whole or in some of its subsystems” (Bunge, Reference Bunge1997: 414), they theorize four processes that make governmental CSR policies work. These processes are as follows: 1) the modification of available restrictions of business behavior through re-regulation, the design of economic incentives, or the creation of isomorphic pressures; 2) the shaping of actors’ preferences and values, for instance, in the context of interventions in deliberative collective decision-making; 3) the provision of knowledge and resources; and 4) the empowerment of third parties to pressure firms towards engaging in CSR compliance. According to these authors, through these processes, “governmental CSR policies can help businesses overcome the barriers that the lack of sufficient motivation, capabilities, knowledge, and legitimacy pose” (Schneider & Scherer, Reference Schneider and Scherer2019: 1162, emphasis added).

Although a social mechanism approach is well suited to capturing the multiple interactions among governmental CSR interventions, Schneider and Scherer (Reference Schneider and Scherer2019) mainly focus on the mechanisms underlying each mode of governmental intervention and the identification of their specific boundary conditions. As a result, the mechanisms by which different modes of governmental CSR intervention interact remain unknown. In addition, even though Schneider and Scherer (Reference Schneider and Scherer2019) highlight boundary conditions that weigh on the mechanisms they identify, they overlook the particular conditions that financial markets create for firms. We now focus on these two limitations, as they motivate our empirical study.

How do Governmental CSR Interventions Interact: Governing through Orchestration

To holistically and longitudinally investigate the interactions between governmental CSR interventions, we build on concepts from the regulative capitalism literature (Abbott, Genschel, Snidal, & Zangl, Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2015, Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2017; Braithwaite, Reference Braithwaite2011; Levi-Faur, Reference Levi-Faur2005). Consistent with the assumption that governments are agential (Knudsen & Moon, Reference Knudsen and Moon2017), we regard governments as able to initiate “a wide range of directive and facilitative measures designed to convene, empower, support, and steer public and private actors engaged in regulatory activities” (Abbott & Snidal, Reference Abbott and Snidal2009: 510).

To capture the variety of governmental CSR interventions, we rely on the distinction between steering interventions—which relate to leading, thinking, directing, and guiding—and rowing interventions—which relate to enterprise and service provision (Osborne & Gaebler, Reference Osborne and Gaebler1992: 25). This distinction has largely been used to account for a new division of labor between governments’ steering—through “hands off” or “soft” types of regulation—and private actors’ rowing—by providing services and technological innovation instead of the state (Osborne & Gaebler, Reference Osborne and Gaebler1992; Levi-Faur, Reference Levi-Faur2005). In contrast, we regard steering and rowing as two useful categories to abductively make sense of current modes of governmental intervention that may blur this traditional distinction.

We regard governments as coordinating CSR interventions through modes of rowing and/or steering, and accordingly consider that a CSR policy “package” can be “orchestrated” by government. Orchestration is defined as “the mobilization of an intermediary by an orchestrator on a voluntary basis in pursuit of a joint governance goal” (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2017: 722) and refers to the enrolment of several intermediaries—through soft governance means—to achieve specific political objectives. Although this notion has primarily been used to investigate how transnational governance organizations or nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) deploy their policy activities (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2015, Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2017), Henriksen and Ponte (Reference Henriksen and Ponte2018) show its empirical relevance to investigations on how governments coordinate many forms of interventions in the aviation industry. In this article, we focus on the mechanisms underlying the orchestration of governmental CSR interventions in financial markets.

Making Governmental CSR Interventions Work in a Financialized Context: Governing through Financial Markets

In the context of financial capitalism (Davis, Reference Davis2009), financial markets are both a central space in which national governments can shape the business adoption of CSR and a potential constraint that weighs on government and firm capacity to implement CSR policies. Prior governance studies suggest that financial markets, per se, can constitute a space for regulating corporate behavior (Engels, Reference Engels, Djelic and Sahlin-Andersson2006), and that multiple forms of “discreet regulations” (Huault & Richard, Reference Huault and Richard2012) take place within, if not through, practices like corporate financial reporting (Botzem & Quack, Reference Botzem, Quack, Djelic and Sahlin-Andersson2006). Marti and Scherer (Reference Marti and Scherer2016) also argue that the promotion of social justice and welfare by corporations requires governmental intervention in the financial sector. Schneider and Scherer’s (Reference Schneider and Scherer2019) analysis of the boundary conditions of governmental CSR interventions also indirectly points to financial markets as a context that shapes the capacity of governments and firms to successfully carry out such interventions. For instance, governmental legitimacy and capacity to engage neutrally in deliberative contexts may be restricted by the lack of credibility of governments in the eyes of financial actors, and firms’ willingness to provide resources to comply with CSR regulations may be reduced by pressures from their shareholders.

Although prior studies of governmental CSR interventions mention SRI policies as a lever of action for government (e.g., Knudsen et al., Reference Knudsen, Moon and Slager2015; Steurer et al., Reference Steurer, Martinuzzi and Margula2012), the mechanisms by which governments directly shape investors’ responsible behavior within financial markets—and, subsequently, indirectly shape corporations’ responsible behavior through financial markets—has been overlooked. In this article, we focus our analysis on how a range of governmental CSR interventions interact within the context of the construction of a national SRI market. Our analysis is guided by the following question: How do governmental CSR interventions operate and interact within financial markets in ways that shape firm behavior?

RESEARCH CONTEXT, DESIGN, AND METHOD

Case Selection

To address this question, we draw from an in-depth historical, longitudinal case study of the French SRI market. Our analysis spans the twenty-year development of this market from 1997 to 2017. Although there were only a handful of French asset managers offering a small number of SRI products in the mid-1990s, the French SRI market has become one of the most developed in Europe since then (Crifo et al., Reference Crifo, Durand and Gond2019; Eurosif, 2018). In 2017, for example, a total of €920 billion AuM were subject to a form of “ESG integration” (investment) strategy, compared to €338 billion in 2015 (Eurosif, 2018: 91).Footnote 2

This market is of specific relevance to our research question for two main reasons. First, it represents a case of relatively successful “SRI mainstreaming” (Crifo & Mottis, 2013: 579) in the sense that numerous, leading, French asset managers and the largest pension funds have now integrated SRI practices into their core business (Crifo et al., Reference Crifo, Durand and Gond2019). Such a shift is of significant global financial magnitude, as the French asset management industry is the second largest in Europe and the third largest in the world, after that of the United States and the United Kingdom (Eurosif, 2018). SRI can thus help us appreciate how national regulations operate through a market that is globally connected by nature. Second, this marketplace, like other European SRI markets (Steurer, Margula, & Martinuzzi, Reference Steurer, Margula and Martinuzzi2008), has been influenced by heated political debates, such as that regarding the management of pension funds or employees’ savings (Crifo & Mottis, Reference Crifo and Mottis2016), and is regarded as an established domain of governmental CSR intervention (Steurer et al., Reference Steurer, Martinuzzi and Margula2012). Prior work has also highlighted the role played by the French state and public actors in this market’s early development (Arjaliès & Durand, Reference Arjaliès and Durand2019; Giamporcaro & Gond, Reference Giamporcaro and Gond2016).

Data Collection

To capture the history of governmental CSR interventions in the French SRI market, we collected data from multiple sources that played complementary roles in our analytical process. Appendix A provides a detailed presentation of our data sources and how they were used.

Historical and Secondary Data

Because we adopt a longitudinal approach to the analysis of the role of the government in the French SRI domain, sources of secondary data played a central role in our analytical strategy (Langley, Reference Langley1999). First, we collected newspaper articles about SRI in France using the Lexis Nexis Academic database and key terms related to SRI (e.g., responsible investment or ethical investment) and the most prominent actors from the field (e.g., leading SRI funds or investment firms). These data helped to build a detailed chronology of the stages of SRI development in France over the twenty-year period in question. Second, we collected all of the available, quantified information about the development and transformation of this market from 1997 to 2017 from the websites of organizations such as Novethic or Eurosif (European Social Investment Forum). Third, we collected all of the governmental reports related to SRI, that is, the documents about the ESG policies of the two main public pension funds, as well as publicly available information related to the state-backed labels for SRI. Fourth, our analysis was also informed by prior academic studies of SRI in France (e.g., Arjaliès, Reference Arjaliès2010; Crifo et al., Reference Crifo, Durand and Gond2019; Déjean, Gond & Leca, Reference Déjean, J.-P and Leca2004; Giamporcaro & Gond, Reference Giamporcaro and Gond2016).

Interviews

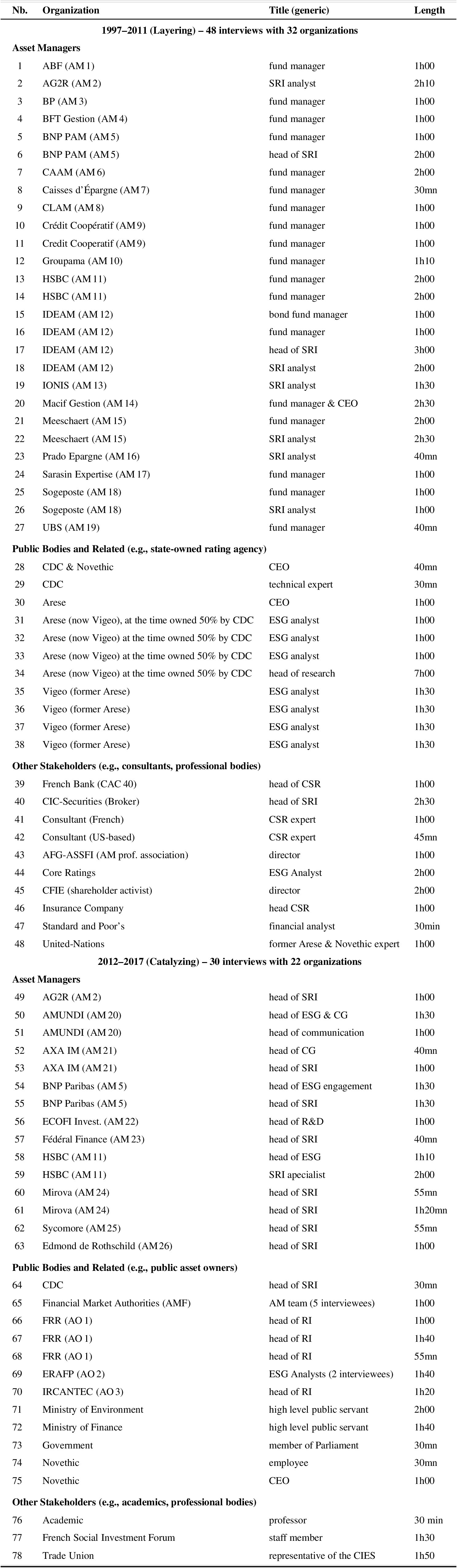

Another important source of information to document the development of the French SRI market and the deployment of governmental interventions was a rich set of seventy-eight semistructured interviews conducted with prominent SRI actors between 2000 and 2017. Forty-eight interviews were completed between 2000 and 2011. We used these earlier interviews to complete and support the secondary archival and historical data to build our narrative. Thirty interviews were completed after 2012 and helped to retrospectively document the effects of the previous period (1997–2011). This second batch of interviews helped us document the in vivo effect of the interactions among the different modes of governmental CSR intervention since 2012.

We count among our interviewees the key actors involved in French SRI “chains of finance” (Arjaliès et al., Reference Arjaliès, Grant, Hardie, MacKenzie and Svetlova2017), such as asset managers (n = 42), state representatives, public asset owners and state-related organizations (n = 23), actors from the leading French CSR rating agency (Arese/Vigeo), and other stakeholders (n = 13), such as trade unions and professional associations (see Appendix B for more details about our interviewees and the timeline of the interview campaigns). Through “snowballing” (Biernarcki & Wardof, Reference Biernarcki and Wardof1981: 141) and our increased familiarity with key actors in the field over the years, we accessed interviewees who played a central, and sometimes prolonged, role in the public administration of and lobbying for the development of the market. Our discussion with these interviewees allowed us to reconstruct elements of the closed-door politics that underlined the design of SRI regulations in the shadow of different ministries between 1997 and 2017.

Participant Observation

Our access to central field actors was also facilitated by the personal ties developed by one of the authors who worked at an organization that played a crucial role in the development of the French SRI market between 2002 and 2008. This author was formally employed to collect and analyze data about the SRI market. Through this position, the author attended high-level discussions about the design and structure of pension fund SRI activities between 2005 and 2007, and observed numerous political dynamics associated with these activities. Many of the contacts developed over this intensive period of field immersion became acquaintances who facilitated further access to SRI actors, who provided open and unpolished insider viewpoints on the highly politicized organizational interactions between private (e.g., asset managers) and public (e.g., state pension fund, ministry) actors during this period. Informal conversations with these interviewees helped us to advance our knowledge of the political dynamics deployed in this market.

Analytical Strategy

To investigate the role of the government in the making of the French SRI market between 1997 and 2017, we combined qualitative (Yin, Reference Yin2009) and longitudinal data analysis methods (Langley, Reference Langley1999), which followed a three-stage process.

Stage 1: Mapping the SRI Market Development through Temporal Bracketing

We first built a detailed chronology of the key events that marked the development of SRI in France over the whole period, identifying the roles of a variety of different stakeholders (asset owners, asset managers, government bodies, CSR rating agencies). Through this process, we could track governmental CSR interventions over the twenty-year period and identify multiple instances of interactions between SRI market development and global forces, such as rising concern about climate change or the emergence of European regulation of SRI. We also relied upon numerous quantitative indicators to track the development of this market in terms of the AuM number of the SRI products developed and the number of asset managers offering SRI products. Figure 1 provides an overview of the evolution of the French SRI market, highlighting its three periods of development. First, from 1997 to 2007 (Period 1), there was continuous growth of the French SRI market, with an increasing number of asset managers participating (from 7 to 47) and a sharp increase in the number of SRI products being offered (from 12 in 1997 to more than 100 in 2007). Numerous changes in the national legal context drove SRI market growth during this first period, which can be referred to as the “construction of a French SRI regulatory springboard.” Second, between 2008 and 2011 (Period 2), we witnessed a phase of legal extension and mainstream appropriation. Despite the 2008 financial crisis, there was a sharp increase in the number of SRI products offered in France (Les Echos, 2009) and a steady increase in AuM subject to ESG criteria in investment decision-making, signifying the “mainstreaming of SRI” among leading French asset managers at the time (Crifo et al., Reference Crifo, Durand and Gond2019; Crifo & Mottis, Reference Crifo and Mottis2016). Finally, between 2012 and 2017 (Period 3), we witnessed SRI mainstreaming in the market, which our interviewees referred to as an “SRI big bang.” In particular, since 2013, the SRI market in France grew exponentially in terms of AuM subject to ESG criteria (from €200 to €322 billion), and the number of new SRI funds created (from 250 to 439 funds). This upsurge in the market derived from the appropriation of ESG investment criteria by major institutional investors between 2006 and 2012 as well as governmental interventions.

Several of our expert interviewees validated this chronology, which we used as an overarching analytical template to identify when governmental CSR interventions took place and what their main effects in the financial marketplace were (see Table 2). Once we identified this pattern of French SRI market development, we focused on how governmental CSR interventions helped to create such mainstream acceptance of SRI in the French financial market.

Figure 1: Overview of the Development of the French SRI Market (1997–2017)

Stage 2: Abduction of Modes of Governmental Intervention

Based on our interviews and secondary data, we grouped the data we acquired about French governmental CSR interventions together and analyzed these through typologies of CSR interventions proposed in the literature (e.g., Gond et al., Reference J.-P, Kang and Moon2011; Knudsen & Moon, Reference Knudsen and Moon2017). Although we initially found Osborne and Gaebler’s (Reference Osborne and Gaebler1992) distinction between steering and rowing relevant to describe governmental interventions, through further analysis, it appeared to be too generic for the empirical complexity of the French government’s interventions in the SRI domain, especially as many of these interventions blended characteristics of both steering and rowing.

Therefore, to make sense of this “anomaly” (Behfar & Okhuysen, Reference Behfar and Okhuysen2018: 329) and to more accurately capture the governmental CSR interventions in our case, we engaged in abductive reasoning (Kekotivi & Mantere, 2010) and analyzed our data again to identify specific combinations or forms of steering and rowing. First, beyond the classical state regulatory steering intervention through direct (or hard) regulation to guide market actors (but without planning sanctions for noncompliance), we identified several indirect forms of state interventions deployed through state-governed organizations that blended elements of steering and rowing, and focused on the empowerment and enrolment of state-owned market actors to deliver CSR policies. We refer to these as delegated rowing interventions. Second, we isolated a third type of intervention that corresponded to a hands-on form of steering by private or public actors and notably took the form of the state capture of SRI labels, which we refer to as microsteering interventions. Microsteering corresponds to governmental CSR interventions that involve the government’s active mobilization of soft power and “technologies of governance,” such as labels, standards, or awards. These technologies share the property of micromanaging actor behavior. Table 1 provides the definition and supplementary illustrations of these three modes of governmental CSR intervention.

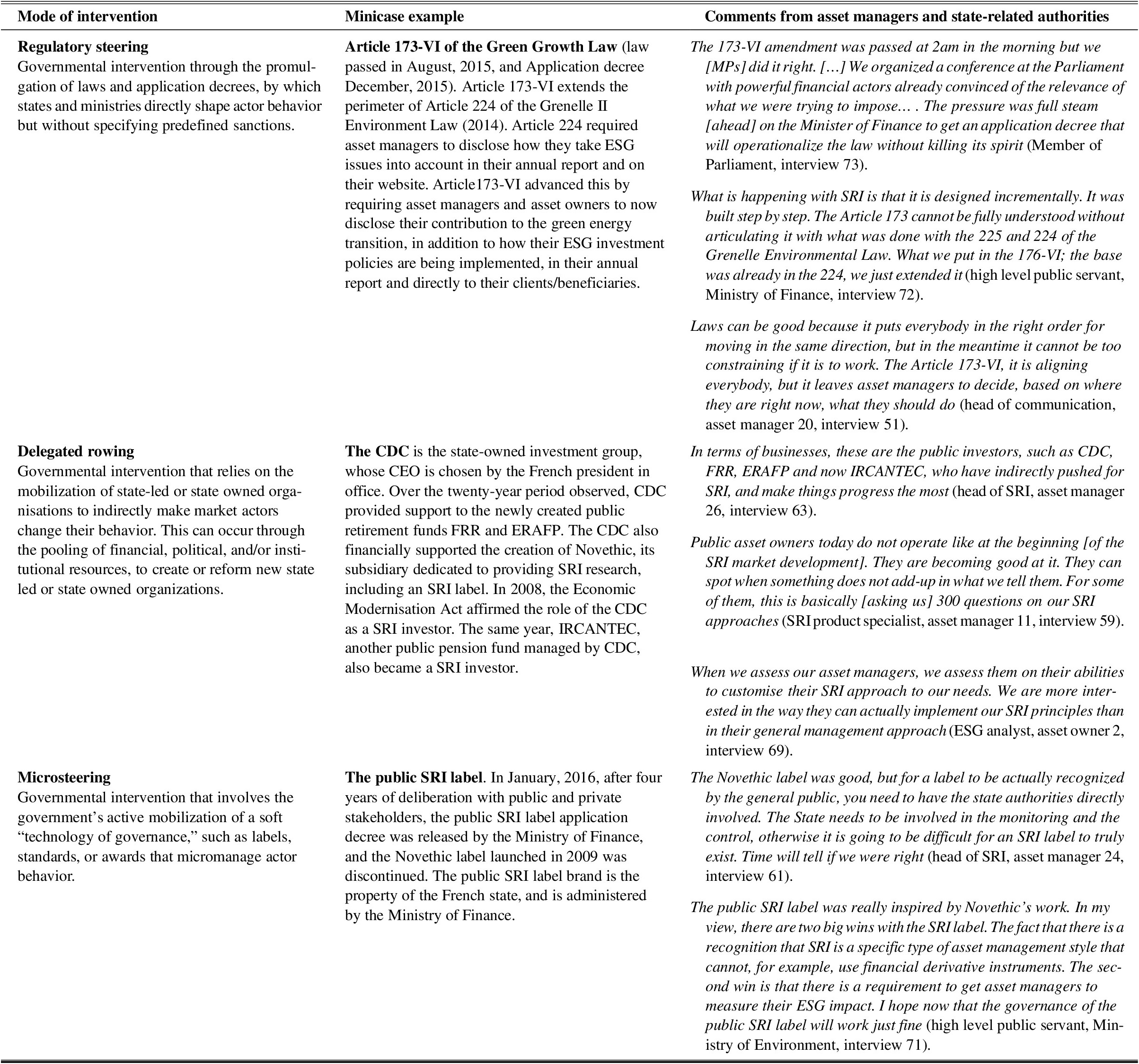

Table 1: Definitions and Complementary Illustrations for the Three Modes of Governmental CSR Intervention

Stage 3: Identification of the Social Mechanisms Explaining How Governmental CSR Interventions Interact

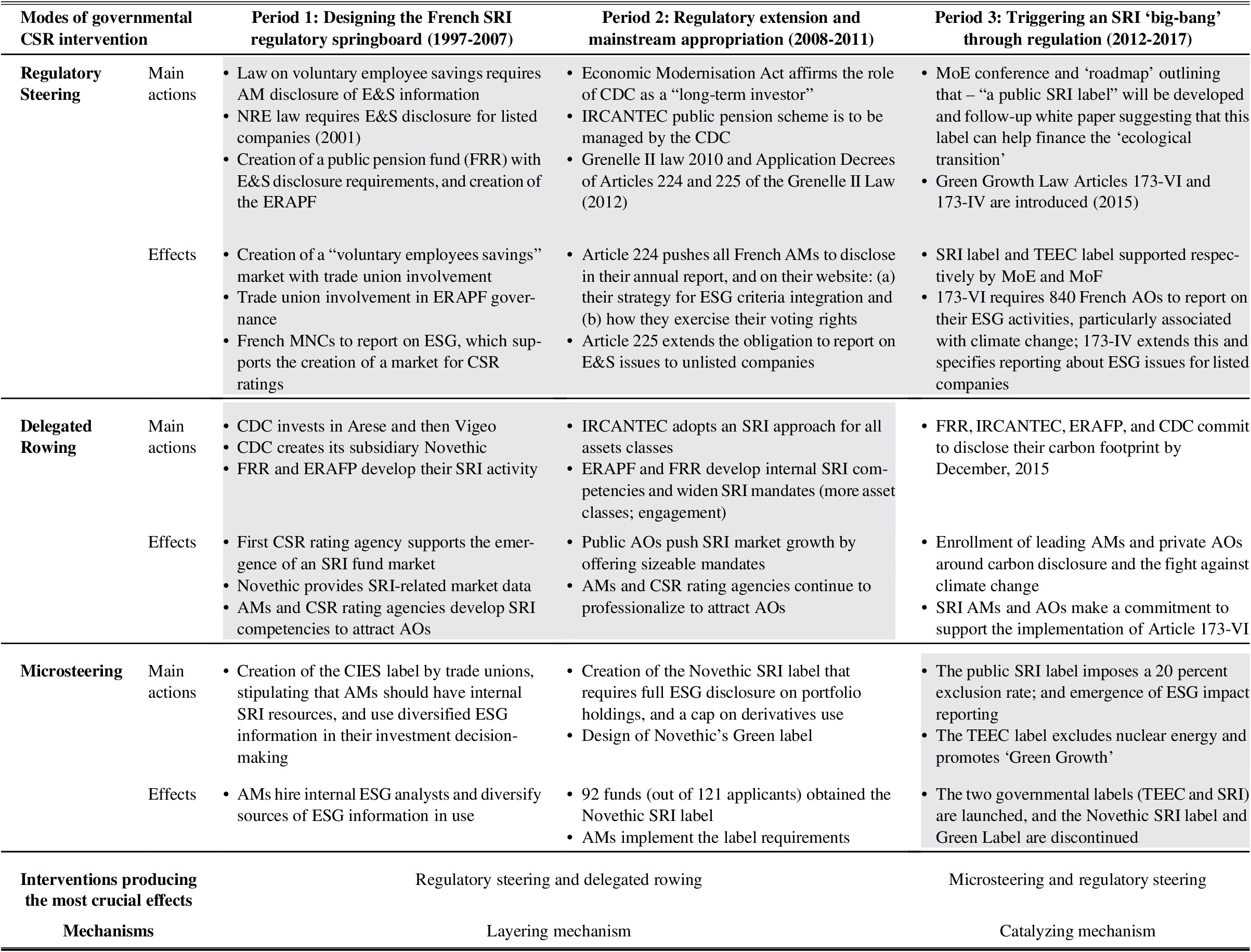

We then used the analytical categories induced in Stage 2 and our temporal brackets identified in Stage 1 to build a chronology of these three modes of governmental CSR intervention. Table 2 summarizes our analysis by showing how the different modes of intervention were mobilized at each period of SRI development and distinguishes the main actions corresponding to the intervention from their effects on the market. Here, we realized that some forms of governmental CSR intervention played a more crucial role in explaining the transformation of the market than others, because the magnitude of their effects was stronger, according to our interviewees (see Table 2).

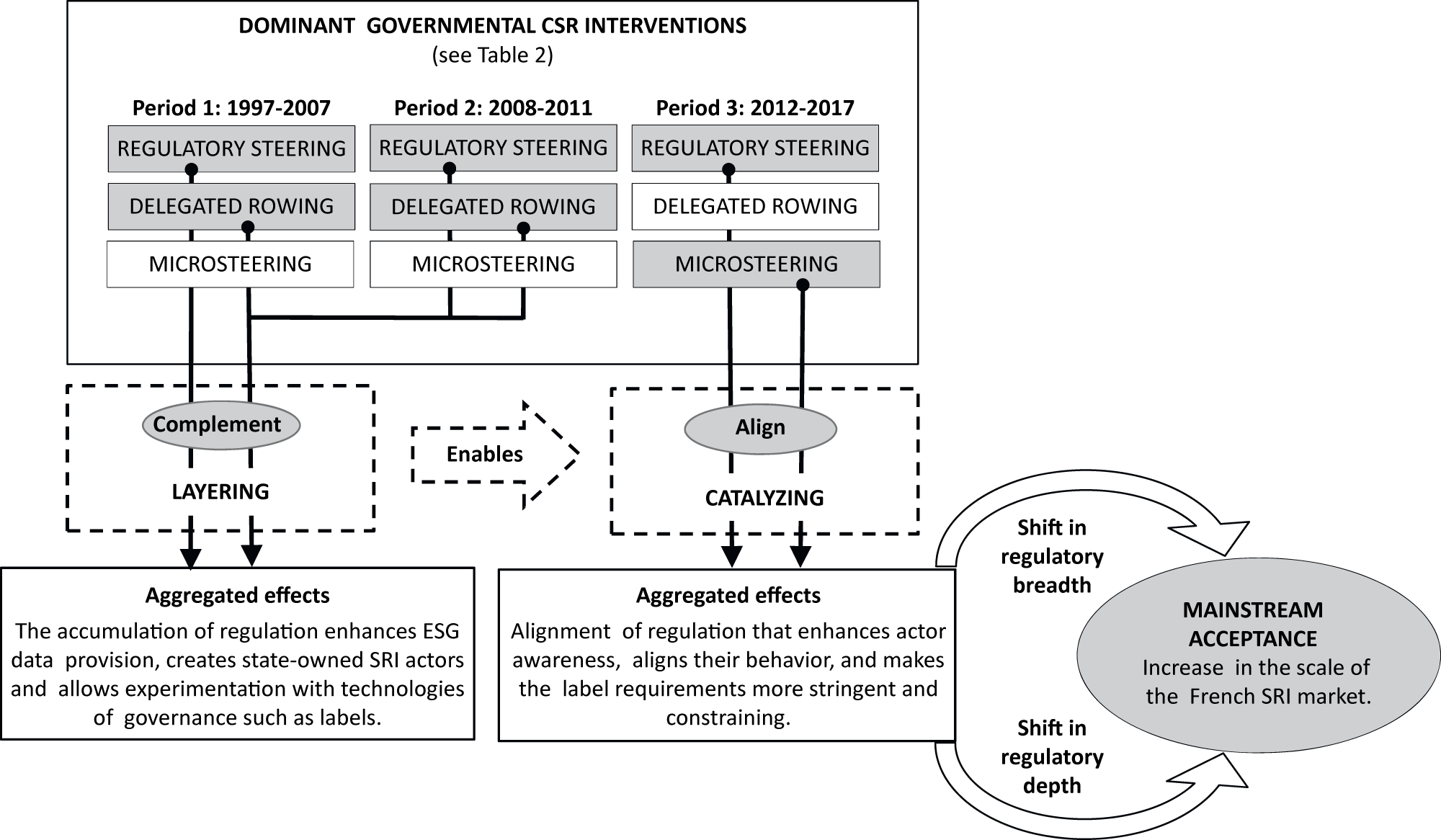

Figure 2: Mechanisms Explaining the Interactions of Governmental CSR Interventions

Table 2: Overview of Governmental CSR interventions on the French SRI market: Effects and Mechanisms (1997–2017)

Note. Cells corresponding to the most crucial effects in the process of SRI market development are shaded. Abbreviations: AFG: Association française de gestion financière; AMs: asset managers; AOs: asset owners; AuM: assets under management; CDC: Caisse des dépôts et consignations; CIES: Comité intersyndical de l’épargne salariale; CSR: corporate social responsibility; ERAPF: Établissement de la retraite additionnelle pour la fonction publique, E&S: environmental and social; ESG: environmental, social, and governance; FRR: fonds de réserve des retraites; MoE: Ministry of Environnment; MoF: Ministry of Finance; NRE: Nouvelle régulation économique; SRI: Socially responsible investment; TEEC: The energy and ecological transition for climate; UCIT: Undertakings for collective investments in transferable securities.

We then revisited our qualitative data to explore how various forms of interactions between, or combinations of, the three modes of governmental CSR intervention could explain the effects we observed (see Table 2). Following Schneider and Scherer (Reference Schneider and Scherer2019), we adopted a “social mechanism” approach (Hedström & Swedberg, Reference Hedström and Swedberg1998; Stinchcombe, Reference Stinchcombe1991) to make sense of the interactions between governmental CSR interventions and focused on the recurrent interactions among governmental CSR interventions, within each period.

Moving back and forth between, on the one hand, the effects of governmental CSR interventions and, on the other hand, their timeline, we realized the importance of the diachronic or synchronic occurrence of these interventions and identified two core underlying mechanisms explaining their holistic impact. The first mechanism is layering, which points to the complementarity between these interventions through a process of accumulation. This process could be metaphorically seen as a form of “legal sedimentation.” That is, each intervention adds a layer of regulation, which creates a context that produces specific effects on market actors (e.g., making CSR calculable, experimenting with new forms of governance). The second mechanism we identified is catalyzing, which relates to the co-occurrence of interventions targeting distinct categories of market actors, making all of them aware of an issue at the same time and aligning their behavior around the issue. The simultaneous interactions among interventions reinforce their impact by operating as a catalyst to SRI mainstreaming within the financial marketplace. Revisiting our chronology in light of these two mechanisms, we realized that layering took place during the first two periods (1997–2011) and catalyzing mainly during the last period (2012–2017), and that both mechanisms involved the combination of distinct modes of intervention. The overarching influence of these mechanisms is depicted in Figure 2. To describe how these mechanisms operate, we developed a detailed narrative that explains the three modes of governmental CSR intervention and their interactions. This narrative forms the basis of our findings section.

ORCHESTRATING AN SRI “BIG BANG”: LAYERING AND CATALYZING

We now show, in detail, how our three modes of governmental CSR intervention built on and complemented each other over time through layering and ultimately aligned the behavior of multiple actors through a series of combined interventions that acted as a catalyzing mechanism for SRI in France. Overall, these mechanisms enabled SRI mainstreaming within the French financial marketplace (see Figure 2).

Layering: Accumulation of Complementary Regulatory Steering and Delegated Rowing Interventions

Dominant Modes of Governmental CSR Intervention in Periods 1 and 2 (1997–2011)

Central to the early development of the French SRI market were the regulatory steering and delegated rowing modes of intervention. Regulatory steering is a mode of governmental intervention used by states and ministries to shape actor behavior through the promulgation of laws and the application of decrees. This mode departs from traditional “command and control” approaches to regulation (MacBarnet, 2007), as the legal frameworks it produces are normally only loosely constraining. These laws do not usually specify sanctions in the case of noncompliance by targeted actors and leave room for multiple forms of operationalization. Between 1997 and 2011 (Periods 1 and 2), regulatory steering progressively enhanced the capacity of a wider range of SRI market actors (first corporations, and then asset managers and public asset owners) to report under the state’s ESG disclosure requirements with increased precision and depth over time.

Delegated rowing corresponds to governmental interventions that rely on the mobilization of state-led organizations to indirectly regulate the behavior of other market actors. Although the responsive capitalism literature regards rowing, in the twenty-first century, as a prerogative—which is usually delegated to the private sector by public actors (Levi-Faur, Reference Levi-Faur2005)—we found that the French state engaged in rowing itself, albeit indirectly. That is, between 1997 and 2011 (Periods 1 and 2), the state pooled financial, political, and institutional resources into new state-led organizations dedicated to SRI and reformed existing organizations by decree with the aim of advancing SRI within the French financial market. Regulatory steering enabled this delegated rowing through the creation of state-led asset owners Fonds de Reserve des Retraites (FRR) and Établissement de Retraite Additionnelle de la Fonction Publique (ERAFP), as well as the mobilization of existing state-owned investment actors, such as Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations (CDC) and their newly created subsidiary, Novethic; these were empowered by the nascent and favorable SRI regulatory environment to act as socially responsible “experts” or “investors” in the French financial market.

How Governmental CSR Interventions Interacted in Periods 1 and 2 (1997–2011)

Layering operated first through an accumulation of regulatory steering interventions that enabled the extension of the number and type of actors subject to compulsory ESG reporting. Over the years, the legal requirements to report on ESG issues moved from corporations in the 2001 New Economic Regulations (NRE) law to employee savings vehicles in the 2001 Fabius law on voluntary employee savings, and eventually to asset managers in the 2010 Grenelle II law (see Table 2)—which, for the first time, obliged asset managers to disclose detailed ESG information (Les Echos, 2012).

There was the NRE [Law] for the companies that turned into the [Grenelle Law Article] 225 and you also had the [Article] 224, which was not super clear but also required from asset managers some ESG reporting. We, asset managers, were asked even before the asset owners to do this. […] The French system channels pressure because the state creates a law for each of the players involved, and this creates a competitive environment for market actors (head of SRI research, asset manager 26, interview 63).Footnote 3

In 2013, a study concluded that 90 percent of asset managers targeted by Grenelle II Article 224 were able to provide general information about their SRI strategies and a list of their investment funds adopting an SRI approach.Footnote 4 As a whole, these regulatory steering interventions by the French state during Periods 1 and 2 forced targeted market actors (companies and investors) to incorporate ESG issues into their activities, so that they could adequately disclose ESG data to CSR rating providers, investors, and other stakeholders, such as trade unions and civil society.

While none of these legal frameworks imposed strict reporting formats, the regulative power of these soft interventions grew as they accumulated, as did the competitive peer pressure associated with their implementation among the key market actors involved. Hence, the consecutive ESG-related laws reinforced each other by extending the scope of the actors involved along the SRI value chain while at the same time deepening the nature of their ESG disclosure requirements.

A second central component of layering was the French state’s combination of regulatory steering and indirect rowing through its major influence on CDC, which is the state-owned investment group, whose chief executive officer (CEO) is chosen by the French president and described by some interviewees as “the financial right-hand man” of the French state. Through multiple application decrees, this organization became more closely involved with the administrative management of two newly created public asset owners: the FRR and ERAFP.

The FRR was established by the pension funds law of July 2001 (law 2001-624) and is a buffer reserve fund designed to protect the French public retirement system in case of financial shortcomings. The ERAFP, created in August 2003 (law 2003-775), is an additional French public service pension scheme whose CEO is appointed by the joint order of the ministers in charge of the public service, the national budget, and social security.

In 2005, the ERAFP’s first action consisted of implementing an ambitious SRI policy to integrate ESG criteria into all of the scheme’s investment decisions. In the same year, the FRR launched its first call for tenders to select asset managers for its SRI funds, followed by the first ERAFP SRI equity call in 2006. These two calls for tender attracted bids from forty and thirty international and local asset managers, respectively (Giamporcaro & Gond, Reference Giamporcaro and Gond2016). The FRR subsequently delegated its SRI investment to six asset managers, whereas the ERAPF entrusted its investment portfolio to two prominent French asset managers: BNP Paribas and IDEAM; the latter a subsidiary of Credit Agricole Asset Management, which, in 2010, merged with another prominent French management house to form Amundi—the biggest French asset manager. In designing two giant asset owners—accounting for €34.5 (FRR) and €4.7 (ERAFP) billion AuM by the end of 2007, who adopted ambitious SRI policies and mandates from scratch, the French government increased the total AuM subject to ESG criteria in the financial market while simultaneously signaling its long-term commitment to SRI to the asset management industry.

The CDC described by interviewees as “being an incubator for SRI” for providing operational and administrative support to the FRR and ERAFP was also tasked in 2007 with managing the IRCANTECFootnote 5—another public pension scheme—which was earmarked by the French government to become an SRI investor:

At the CDC, one of our main internal clients is IRCANTEC. IRCANTEC administrators wanted all IRCANTEC assets to be managed with SRI principles. The first mission for us was to define what that means. An SRI charter was defined. Our job is to implement it with the help of the external asset managers we work with. If you compare us with the FRR, which started its SRI program in 2002–2003, and ERAFP in 2005–2006, we started later in 2007. There is competition between public asset owners but of a benevolent kind. Our goal is to catch up and to be even better (head of RI, asset owner 3, interview 70).

In addition, in 2008, the Economic Modernisation Act (Law 2008-776) marked a significant turning point in the French SRI market, as it repositioned the public investment group, CDC, as an SRI investor, which the following statement from CDC’s website, published directly after this act launched in 2008, outlines:

The CDC is a long-term investor: It analyses the profit of its holdings portfolio on a long-term horizon. This long-term horizon leads the CDC to behave as a SRI investor (CDC Investment Doctrines, December 2008, available on the CDC website).

In general, this revised legal framework confirmed the already well-acknowledged prominence of these state-led organizations in the development of the French SRI market (see Table 1). From 2001 onwards, the CDC, FRR, ERAFP, and IRCANTEC developed their SRI competencies, strategies, and products but also delegated many financial services and products—through market intermediaries and asset managers—that they were not willing to generate directly.

These large public-asset owners led the French financial industry towards more SRI professionalization, not only through their multiple calls for asset manager ESG tenders but also through their direct influence on the SRI agenda itself, notably through voting and engagement with companies on ESG matters (heads of RI and ESG analysts, asset owners 1, 2, 3, interviews 66 to 70; FRR, 2017). These asset owners delicately built their ability to govern the conduct of their asset managers with regard to SRI matters.

If you want to have an ESG impact on the companies, the most efficient way to go about this is to hassle your asset managers regularly. It is a leverage phenomenon that can have multiple effects. We have more than 50 asset managers working for us. Our main leverage on the companies is to get all our asset managers to engage in ESG with them (head of RI, asset owner 1, interview 67).

By applying “soft touch” regulatory steering through laws and decrees, the state created or pushed existing actors to integrate ESG factors into their investment operations. Additionally, this approach made it possible for them to form a pioneering “club” of public asset owners engaged in SRI (head of RI, asset owner 1, interview 68) who were able to influence investee company CSR performance in a delegated fashion through their asset managers.

In addition, the CDC was instrumental in indirectly influencing market actors’ behavior through its role in the consolidation of the informational infrastructure of the SRI market.

At the CDC, we are currently working on developing market tools such as ESG ratings for companies and SRI funds …. I am convinced that financial markets will progressively integrate this broader approach to assess economic performance (Daniel Lebegue, CEO of CDC; interviewed in La Tribune, October 2002).

That is, before becoming legally recognized as an SRI investor in 2008, the CDC financially supported two key ESG calculative agencies: Arese in 1999, which became Vigeo, the national CSR ratings agency, in 2002; and Novethic in 2001, which has its very own subsidiary dedicated to providing CSR and SRI information and research (Giamporcaro & Gond, Reference Giamporcaro and Gond2016). Vigeo enabled the state to exert indirect pressure on companies and asset managers, as it produced company CSR ratings and benchmarks to incentivize companies to improve their CSR strategies and performance, and simultaneously equipped asset managers with a calculative device to enhance their investment decision-making and SRI products.

Similarly, Novethic stimulated asset managers to increase and compare their SRI expertise. Through the support of the CDC and based on the legitimacy and success of its SRI ratings system and market reports (Giamporcaro, Reference Giamporcaro2006), Novethic transformed its SRI ratings system into a certification system in October 2009—which is known as the “Novethic SRI label” (Arjaliès & Durand, Reference Arjaliès and Durand2019). This scheme required asset managers to pay fees to enter the certification process to obtain the label. Novethic equipped the label with an “Independent Advisory Council,” including representatives of civil society organizations as well as public and private stakeholders. To obtain the label, French asset managers had to provide details about their SRI management approach; report on the ESG characteristics of their portfolio; provide clarification on the exact use of derivative instruments considered non-SRI compatible since the 2008 financial crisis; and, more contentiously, disclose the full list of portfolio holdings for any labeled fund at least once a year (Arjaliès & Durand, Reference Arjaliès and Durand2019). This approach to labeling opened up the “black-box” of SRI products available to retail clients, as it forced asset managers to publicly disclose their SRI policies and activities.

When the Novethic label came in, it was ambitious but necessary. You knew as an asset manager that you would need to prove that you were “walking the talk” in order to get in. The asset managers operating in France largely followed the Novethic label (head of SRI, asset manager 5, interview 55).

Overall Impact of Layering in the Financial Marketplace

In sum, throughout Periods 1 and 2 (1997–2011), the French state continuously empowered state-led organizations, such as the CDC, public pension funds, Vigeo, and Novethic, through the combined mobilization of regulatory steering and indirect rowing interventions. These interventions complemented each other so that state interventions resulted in the progressive extension of the French SRI market due to the large size of some of these actors, such as the newly created public funds FRR and ERAFP (direct effect of regulatory steering) or the public asset owners, such as the CDC and IRCANTEC (indirect effect of regulatory steering and delegated rowing), that were “converted” to SRI.

These multiple “layers of regulation” subsequently enabled various relational and “isomorphic” forms of market regulation (Schneider & Scherer, Reference Schneider and Scherer2019). First, the adoption of SRI strategies and practices by dominant public asset owners created peer pressure for other asset owners, as illustrated by the case of AGIRC-ARCCO (the national complementary retirement scheme for private sector employees), which jumped onto the SRI bandwagon in 2006 (see Les Echos, 2006). Second, these state-governed asset owners directly shaped the behavior of private assets managers through the numerous SRI mandates they required. Local and international asset managers began to reorganize themselves—through the creation of dedicated SRI services and competencies—to compete for these pioneering SRI tenders by large, public asset owners. Third, through the delegated rowing that created calculative agencies and regulatory steering regarding ESG disclosures, the French state shaped a competitive market environment around SRI.

Hence, in 1997, only seven asset managers supplied a marginal amount of SRI products; in 2012, fifty-three asset managers (including the largest, Amundi) were actively involved in the management of more than 250 SRI products (see Figure 1). In addition, since 2003, French asset managers, eager to be taken seriously and to benchmark well against their peers, sought to obtain a good Novethic SRI rating. After 2009, asset managers applied to be awarded the Novethic SRI label for their SRI funds. In addition, public asset owners began to complement their nascent SRI expertise, by using the services of organizations such as Novethic and Vigeo, which were created through delegated rowing. For example, in 2006, the ERAPF and FRRFootnote 6 (followed later by IRCANTEC) used Vigeo—as well as other CSR rating agencies—to measure the ESG quality of portfolios managed by delegated asset managers. During the same period, Novethic was tasked by the CDC to act as an internal SRI consultant for the ERAFP (Giamporcaro & Gond, Reference Giamporcaro and Gond2016). Ultimately, this market environment—constituted of the layering of multiple, complementary governmental interventions—enabled the emergence of an “SRI Big Bang” in France through catalyzing.

Catalyzing: Alignment of Regulatory Steering and Microsteering for SRI Mainstreaming

Dominant Modes of Governmental CSR Intervention in Period 3 (2012–2017)

Microsteering involves the active mobilization of “soft” governmental modes of intervention or “technologies of governance,” such as labels, calculative devices (Miller, Reference Miller1992), or standards (Reineke, Manning, & Von Hagen, 2012; Slager et al., Reference Slager, Gond and Moon2012), which micromanage market actor ESG behavior (see Table 1). In our context, microsteering mainly takes the form of SRI labels created with stringent criteria to determine what products and services can be considered “socially responsible.” Through the evolution of the French SRI market between 1997 and 2012, labor unions, market intermediaries such as Novethic, and asset managers were directly involved in SRI label construction (see Table 2). Central to our analysis, however, is the fact that between 2012 and 2017, the French government intervened in order to capture, and thus legally solidify, some of these labels, which became, by decree, the property of the state in December 2015 and January 2016 (see Table 2).

It is the first time the French state created a label for a financial product. It never interfered this way with investment before (head of SRI, asset manager 5, interview 65).

In parallel to microsteering, which emerged as a dominant mode of intervention at the time, this second stage of market development was also characterized by the extension of regulatory steering. The deployment of Green Growth Law Article173-VI (2012-17, see Table 2)—referred to by practitioners as “the 173” and passed in August 2015—considerably extended the French state’s regulatory steering perimeter.

I think that everything changed in 2015 with the Ministry of Environment, which pushed the Green Growth Law and Article 173. This is when you realize that the willingness of the regulator changes everything. When I talk about a ‘Big Bang,’ this is what I meant, that the French state had been the essential trigger of all of the changes that we are experiencing today (head of SRI, asset manager 21, interview 53).

Microsteering and regulatory steering modes of intervention became fully aligned when Article 173-VI passed in December 2015, which stated that any commitment to labels pertaining to the achievement of ESG and climate objectives need to be reported upon both by asset managers and asset owners.Footnote 7

How Governmental CSR Interventions Interacted in Period 3 (2012–2017)

To understand the catalyzing mechanism that aligned and strengthened SRI market forces, it is vital to unpack the series of events that led the French government to co-opt and then take over the microtechnology of governance that was experimented with by labor unions in the early 2000s, i.e., labels (Giamporcaro & Gond, Reference Giamporcaro and Gond2016). This analysis will be followed by a discussion of the genesis of Article 173-VI, which builds on the French state’s SRI regulatory steering effort deployed from 1997–2012 requiring mandatory reporting by public and private asset owners regarding their exposure to carbon risks for the first time.

In July 2012, the Novethic SRI label was singled out as a form of greenwashing by the most famous investigative journalism TV show in France.Footnote 8 During the show, the Head of SRI funds at Amundi and the CEO of Novethic were set upon in front of the camera by the reporters and exposed as being unable to explain why a corporation involved in a recent oil leak was still part of Amundi’s SRI funds (Arjaliès & Durand, Reference Arjaliès and Durand2019). Novethic reacted by increasing the stringency of its SRI label in September 2012 and raising the proportion of SRI-related exclusions from investment portfolios that was needed to bring the label to 15 percent (in comparison to the fund’s investment benchmark). As a result, only 109 funds obtained this new label, in contrast with 156 the previous year (Le Monde, 2012). Subsequently, Amundi rapidly ceased its application for the label and announced that its SRI process would now be certified by another organization that did not necessarily require reliance on exclusion-based criteria (Arjaliès & Durand, Reference Arjaliès and Durand2019). This Amundi/Novethic dispute (Le Monde, 2013) created an unresolved chasm in the French SRI market and marked the entry of the Ministry of EnvironmentFootnote 9 and the Ministry of Finance into the debate, which initiated the French state’s capture of the label development process and produced an unparalleled mode of microsteering regulation.

In June 2013, one year after a state multiparty environmental conference that hinted that a public SRI label was in the pipeline, the necessity of creating a “unique and enriched SRI label” was reiterated by a public report commissioned by the Ministry of Environment and the Ministry of Finance (Brovelli, Drago, & Molinié, Reference Brovelli, Drago and Molinié2013).Footnote 10 The idea of a governmental SRI label was further discussed during the French Banking and Finance Conference for the Energy Transition the following year in June 2014. This discussion led to a series of conferences, events, and workshops during which numerous private and public stakeholders intervened to shape the criteria of the label, as described retrospectively by the CEO of one of the leading French SRI asset managers:

Flagship examples of how regulation can strengthen the attractiveness of commercial activities, and be designed in collaboration with private actors, come to mind…. In September 2012, during ‘the Environmental Conference’ called by the Hollande President, the government announced its willingness to create a public SRI label…. We immediately wanted to work with the government [on this]. This process spread over two years and ran through some difficulties, but we eventually reached a consensus, and the creation of two public labels: The public SRI label under the stewardship of the Finance Ministry; and the ecological transition label under the stewardship of the Ministry of Environment (Philippe Zaouati, CEO of Mirova, extract from his book: Green Finance Starts in Paris, 2018).

Following three years of intense stakeholder lobbying, two distinct yet stringent labels were launched officially by ministerial decrees: “the [financing] energy and ecological transition for climate” (TEEC) label in December 2015 (decree 2015-1615) and the “public SRI label” in January 2016 (decree 2016-10).Footnote 11

This is really the moment [2013-2015] when we all started to lobby the government. If you [the state] really want to create a public SRI label, this is up to you, but this is not going to help you to finance the ecological transition; you will need another label for this, a specialized one (Novethic, CEO, interview 75).

Central to this process was the tension among leading French asset managers with competing views on the “SRI exclusion ratio” to be adopted for labeled funds.

When the Ministry of Finance took over the public SRI label, the objective was to reach a regulatory situation where it has to make sure that SRI is really doing what it says it does, but in the meantime, the ministry had also to deal with the negative and antagonist energy of some market players in order to build something more positive (high level public servant, Ministry of Finance, interview 72).

The public SRI label is a good illustration of how microsteering facilitated greater regulation of private actors, as the capture of this governance tool allowed the French government to reshape investors’ internal investment processes in a relatively “low cost” way. This label also capitalized on prior microsteering interventions from other market actors, such as the Novethic SRI label, but it also strengthened some of their requirements by, for example, including a 20 percent SRI-related exclusion rate on investment portfolios instead of 15 percent, requiring the adoption and implementation of a shareholder ESG engagement policy, and requiring the measurement of SRI portfolios’ positive ESG impact.Footnote 12 In addition, the label broadened the scope of previous microsteering efforts, even though there was an absence of NGOs in the governance of the label, and hence, the label’s independence was still contested:

Because the majority of stakeholders focused only on fighting about the SRI exclusion rate of the label, we could get the elements we wanted within the label about shareholder engagement and detailed ESG impact measurement—two things that were absent from the prior Novethic label. My only regret is that NGOs are not represented in the executive committee (trade union, CIES representative, interview 78).

By stepping into the process of label development and mediating the conflict between leading asset managers, the French state significantly extended the depth of its intervention in the market but in a way that was well received by the French investment industry:

The willingness of the French state to show that it wants to promote SRI is very clear. The public SRI label reference document is testimony to this. This is going very far. This is a very stringent system (SRI product specialist, asset manager 12, interview 59).

Today, the public SRI label remains the property of the French state, and its current administration rests with the Ministry of Finance, while state-accredited third-party providers are in charge of the auditing process and are remunerated directly by asset managers without any further state interference.

The French state not only extended the depth but also the breath of its ability to govern responsible business conduct in Period 3 (2012–2017). The mobilization around the drafting of Article 173-VI is testimony to the work of the French Parliament, the Ministry of Finance, and the Ministry of Environment at the time. From 2012, the French state—through the Ministry of Environment and soon after the Ministry of Finance—engaged in the analysis of how to facilitate the energy transition, which led the state to take a special interest in what had been developed by asset managers, public asset owners, and service providers—such as Novethic and Vigeo—who were engaged in SRI. As one of our leading asset manager interviewees involved in this deliberative process recognized, the French government “was smart,” as it “met with all the SRI players and got them to talk about all the pioneering things they were doing”; the passage of Article 173-VI (see Table 1) and the operationalization of its decree were organized through an ongoing dialogue with investors:

Designing the 173-VI decree was tricky, in the sense that it needed to be kept politically meaningful without losing half the actors in the process. …You cannot force the mainstream finance actors to become SRI actors straightaway….But, if you steer the conversation towards the idea that ‘SRI players have their own motivation but there is a couple of things they understood, you could learn from them.’ You can also start to ask ‘Did you think about your ESG objectives?’ The 173-VI decree is about forcing this strategic reflection about what ‘ESG objectives’ could mean. The goal is to create some kind of acceleration around the SRI idea and to catalyze some research and development from different investors who are more or less advanced but who all have to comply with or explain their ESG objectives (high level public servant, Ministry of Finance, interview 72).

As a result, when Article 173-VI and its decree were released, “there was no other way for asset managers and asset owners than to support Article 173-VI, even with regard to its climate ambitions” (Head of SRI, Asset Manager 24, interview 61).

Overall Impact of Catalyzing in the Marketplace

Overall, the synchronicity of microsteering and regulatory steering created a mainstream acceptance of SRI in the French financial market by suddenly increasing both the depth and breadth of governmental intervention (see Figure 2). During Period 3 (2012–2017), the state proactively captured the previous trade union and state-related agencies’ efforts to create a label for SRI products and fast-tracked the passing of the pioneering Green Law Article 173 regarding climate change reporting. The latter was enhanced by the prominence of ESG issues and the finance sector in the twenty-first conference of the parties (COP 21) and was confirmed by the launch of the Paris Climate Change agreement in mid-December 2015.Footnote 13 In the space of only four weeks, the French state and its ministers released three ground-breaking application decrees for the public ecological transition label (10 December, 2015), Article 173-VI (29 December, 2015), and eventually for the public SRI label (8 January, 2016).

The consecutive development of state-owned labels through microsteering supported the enrolment of major market players who could not refuse the adoption of a label they had codesigned. As shown in Figure 1, between 2012 and 2017 and, in particular, since 2013, the SRI market in France grew exponentially in terms of AuM subject to ESG criteria (from €200 to €322 billion) and the number of new SRI funds created (from 250 to 439 funds). Here, microsteering through the stringent public SRI label enhanced the regulatory depth of governmental interventions in the SRI realm. At the end of September 2018, the public SRI label was awarded to 166 funds from 36 asset management firms with approximately €45 billion AuM (Eurosif, 2018).

In parallel with the rapid adoption of the public SRI label, regulatory steering through Article173-VI also increased the SRI market’s regulatory breath. For instance, Novethic reported that, from a sample of one hundred of the leading institutional investors in France, seventy-three asset owners representing €2,093 billion (or 85 percent) of the combined assets presented documentation that fully or partially complied with Article 173-VI of the 2015 French Energy Transition Act.Footnote 14 Hence, as summed by one of our interviewees, the creation of the public SRI label aligned institutional investors’ commitment with stringent ESG objectives such as those laid out in Article 173-VI:

Today, we can walk on two legs. We improve institutional investor practices with the 173, and we provide a high visibility tool to the general public with the label. But what is super interesting is that it is very likely that some asset owners who want to comply with Article 173-VI will end up investing in funds that were awarded the public SRI label. The main goal of the public SRI label was, in my mind, to reach the retail market, but actually in the future, assets owners are likely to be the ones who will use the public SRI label to fulfil, at a minimum, their ESG objectives (French Social Investment Forum, staff member, interview 77).

In short, both governmental CSR interventions interacted to contribute to SRI mainstreaming within the financial market, as reflected in Figure 1, following the layering and catalyzing mechanisms presented in Figure 2.

CONTRIBUTIONS, DISCUSSION, AND CONCLUSION

In this study, we explored how governmental CSR interventions interact to shape business behavior through financial markets. Through a longitudinal analysis of the French SRI market, we identified three modes of governmental intervention that combine elements of steering and rowing: regulatory steering, delegated rowing, and microsteering. Our findings show how the French government’s CSR interventions interacted through two mechanisms: Layering, which evolved through an accumulation of complementary pieces of regulation and created an informational context favorable for SRI market development within which actors could experiment with new technologies of governance such as SRI labels, and catalyzing, which combined regulatory steering and microsteering interventions to align market actors’ interests and behavior. Layering enabled the catalyzing of the French SRI market so that governmental CSR interventions triggered mainstreaming throughout the market (Figure 2).

Our study has resulted in a number of insights into the theorization of governmental CSR interventions in neoliberal capitalism, the analysis of the interactions of these interventions, the orchestration of these interventions by governments, and the mobilization of financial market intermediaries to regulate CSR. We discuss these insights in more detail below before evaluating some of the boundary conditions of our results as well as the ethical implications of our study.

Contributions to the Study of Governmental CSR Interventions

Reinventing Governmental CSR Interventions: The Recombination of Steering and Rowing

Our first contribution is to identify and label modes of governmental CSR intervention that question the established distinction between the steering role of government and the rowing role of private actors in the provision of public goods (Levi-Faur, Reference Levi-Faur2005; Osborne & Gaebler, Reference Osborne and Gaebler1992). Our results show that, in the case of the French SRI market, such roles became blurred as the government experimented with modes of intervention that enhanced its influence while remaining compatible with the neoliberal search for “low-cost” regulation. Although regulatory steering was privileged as a mode of governmental CSR intervention in France—a country where the role of the state in business affairs remains central (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt, Elgie, Mazur, Grossman and Appleton2016)—these interventions were focused on market construction, blurring the traditional roles of private and public actors. Regulatory steering interventions led to the construction of an informational context supportive of SRI market development (e.g., design of laws supporting the provision of ESG data) and the enabling of market actors’ experimentation with new ways of governing investor behavior (e.g., through the creation of SRI labels). Through such interventions, the French state could enhance its national influence on corporations and even extend that influence beyond the French borders, as “regulated” SRI-focused investors can subsequently influence investee companies globally (see also Vasudeva, Reference Vasudeva2013).

However, our study significantly extends prior insights into governmental interventions by showing that, even in such a state-driven context as France, governments can move beyond steering through the active mobilization of state-owned organizations (delegated rowing) or the capture of labeling initiatives developed by other actors (microsteering). Delegated rowing and microsteering recombined rowing and steering in an unprecedented manner (Levi-Faur, Reference Levi-Faur2005; Osborne & Gaebler, Reference Osborne and Gaebler1992), as they involved the government more deeply without relying on a traditional “command and control” approach to regulation (McBarnet, Reference McBarnet, McBarnet, Voiculescu and Campbell2007). These two modes of intervention further blur the roles of public and private actors in the CSR domain. How the French state dealt with the governmental SRI label provides a good illustration. The government enabled deliberations between private actors, specified the criteria of the label to be implemented by private investors, and defined which private auditors were allowed to audit this label while formally remaining the owner of the label.

Interestingly, the three modes of intervention we identified can activate one or several of the mechanisms theorized by Schneider and Scherer (Reference Schneider and Scherer2019). For instance, governmental CSR interventions in France have provided market actors with ESG-related knowledge (regulatory steering), created massive isomorphic peer pressure by redefining the mission of state-governed financial institutions (delegated rowing), and informed collective deliberations at crucial moments regarding the definition of French SRI and green labels (microsteering). As a whole, the portfolio of governmental CSR interventions we documented in our study shows that, even in a neoliberal context dominated by market mechanisms, governments can intervene to enhance their influence over private actors’ CSR-related behavior. Our analysis, thus, addresses the recent call for studying the mechanisms underlying governmental interventions in “rapidly growing” and “new areas,” such as SRI (Kourula et al., Reference Kourula, Moon, Salles-Djelic and Wickert2019: 1117).

Explaining How Governmental CSR Interventions Interact: Layering and Catalyzing

Our second contribution relates to the interactions among governmental CSR interventions. Recent research has called for both the theorization of the mechanisms underlying governmental CSR interventions (Schneider & Scherer, Reference Schneider and Scherer2019) and a more holistic understanding of how such interventions operate (Dentchev et al., Reference Dentchev, Haezendonck and van Balen2017; Knudsen & Moon, Reference Knudsen and Moon2017), which can be approached by considering how interventions interact.

Our study responds to these calls, as our analysis moves beyond a one-by-one investigation of the social mechanisms by which governmental CSR interventions operate (Gond et al., 2011; Schneider & Scherer, Reference Schneider and Scherer2019) to conceptualize the mechanisms underlying the interactions between these interventions, namely layering and catalyzing. These two social mechanisms are consistent with the “embedded” and “agential” (Knudsen & Matten, 2017: 15) nature of governmental CSR interventions. On the one hand, layering reflects governmental embeddedness within a legacy of CSR regulations, as it suggests that governments can accumulate regulative components of an institutional puzzle waiting to be assembled. In our case, there were no omniscient technocrats with a twenty-year regulatory grand plan. Rather, successive governmental CSR interventions designed the pieces of a multisided regulatory puzzle and, in so doing, developed the breadth and depth of the French SRI market. On the other hand, catalyzing reflects a more agential approach to governmental regulation, as it involves leveraging market actors’ power through the alignment of their interests within a predefined regulatory context. In this regard, catalyzing consisted of French governmental actors purposively adding the last decisive regulatory pieces to the puzzle – through targeted interventions—to trigger mainstream acceptance in the market.

Although, in our case, both mechanisms operated sequentially—with catalyzing depending on pre-existing layering—we think that these mechanisms can potentially operate independently from each other, and we regard the precise nature of their interrelations as an empirical question to be explored in future studies. Methods, such as fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fs-QCA) (Fiss, Reference Fiss2007; Misangyi et al., Reference Misangyi, Greckhamer, Furnari, Fiss, Crilly and Aguilera2017), can help to generalize the analysis of how both mechanisms interact and operate across multiple contexts. In addition, future studies could, for example, explore how different elements of a package of governmental CSR policies (e.g., laws about ESG corporate disclosure, the SRI-focused regulation of state-owned pension funds, support for third parties, or governmental SRI labels) are organized in configurations that produce specific CSR-related outcomes at the country level (e.g., SRI practice diffusion in a given financial market).