INTRODUCTION

Repairing broken firm-stakeholder trust is a complex process that involves a diverse set of stakeholders (Dirks, Lewicki & Zaheer, Reference Dirks, Lewicki and Zaheer2009; Gillespie & Dietz, Reference Gillespie and Dietz2009; Pfarrer, Decelles, Smith, & Taylor, Reference Pfarrer, Decelles, Smith and Taylor2008; Rhee & Valdez, Reference Rhee and Valdez2009). Indeed, scholars have made much progress understanding the dynamics of firm-stakeholder trust repair, taking into account the organization’s responsiveness to key stakeholders (Bundy, Shropshire, & Buchholtz, Reference Bundy, Shropshire and Buchholtz2013; Lange & Washburn, Reference Lange and Washburn2012; Pfarrer et al., Reference Pfarrer, Decelles, Smith and Taylor2008), its resource relationships with stakeholders (Frooman, Reference Frooman1999), the utility of the relationship (Pollack & Bosse, 2014), and the need to actively manage trust (Gillespie, Dietz, & Lockey, Reference Gillespie, Dietz and Lockey2014; Pirson & Malhotra, Reference Pirson and Malhotra2008, Reference Pirson and Malhotra2011; Van Der Merwe & Puth, Reference Van Der Merwe and Puth2014). Recognizing that firms will respond to different stakeholder concerns in different ways, we introduce a new construct, moral salience, which is the extent to which an organization’s misconduct is morally noticeable.

From the Deepwater Horizon/BP oil disaster to Subway’s eleven-inch ‘Footlong’ sandwiches, corporate misconduct damages firm-stakeholder trust. Firm misconduct includes “acts of omission or commission committed by individuals or groups of individuals acting in their organizational roles who violate internal rules, laws, or administrative regulations on behalf of organizational goals” (Vaughan, Reference Vaughan1999: 288). Misconduct can range from actions that are unethical or corrupt to mistakes that stem simply from incompetence or neglect of duties. Similarly, damaged relationships can range from ones that are close and relational to ones that are more distant and transactional.

When an organization commits misconduct, stakeholders view the organization differently. Stakeholders judge the systems, processes, culture, and management practices of the organization (Gillespie & Dietz, Reference Gillespie and Dietz2009) as they try to recalibrate their views based on the event (Dirks & Ferrin, Reference Dirks and Ferrin2001). The repair of organizational trust becomes particularly challenging as the organization tries to reintegrate itself with its stakeholders (Pfarrer et al., Reference Pfarrer, Decelles, Smith and Taylor2008). Organizational trust is critical to the value-creating potential of stakeholder relationships as well as a source of competitive advantage (Barney & Hansen, Reference Barney and Hansen1994). However, once trust is broken, stakeholders must decide whether to rebuild trust with the firm or end the relationship (Malhotra & Lumineau, Reference Malhotra and Lumineau2011).

In order to reverse such judgments, it is important to understand the characteristics of the issue and the firm’s relationships with its stakeholders (Schoorman, Mayer, & Davis, Reference Schoorman, Mayer and Davis2007). Acts of misconduct may be unethical or illegal (Baucus, Reference Baucus1994), and may require different steps to the restoration of trust, “depending on the organization, its stakeholders’ expectations and the transgression itself” (Pfarrer et al., Reference Pfarrer, Decelles, Smith and Taylor2008: 730 footnote). We therefore approach firm-stakeholder trust repair in terms of two factors: the moral intensity of the misconduct (Jones, Reference Jones1991), and the relational intensity of the psychological contract between the firm and its stakeholders (Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997). Together, these two factors comprise moral salience. We develop a model of firm-stakeholder trust repair with these elements, showing how the need for goodwill in repair will vary with moral salience, moderated by the stakeholder culture of the firm.

MORAL INTENSITY

A key component of moral salience is moral intensity, which Jones (Reference Jones1991: 372) defines as “the extent of issue-related moral imperative involved in a situation.” Moral intensity is issue-specific and, as such, does not include decision maker traits or organizational factors. As emphasized by Jones, “In sum, moral intensity focuses on the moral issue, not on the moral agent or the organizational context.” (Jones, Reference Jones1991: 373). Footnote 1 A moral action occurs when a freely performed action harms or benefits another (Velasquez & Rostankowski, Reference Velasquez and Rostankowski1985). Few issues have high moral intensity; most are at the low level. According to Jones (Reference Jones1991), the degree of moral intensity of the issue is a function of six factors: the magnitude of the consequences (i.e., the total of all the harms and benefits) to each stakeholder; the degree of social consensus that the issue is good or evil, harmful or beneficial; the probability of effect (i.e., the likelihood that the harm or benefit will actually occur); the temporal immediacy of the consequences (i.e. the length of time between the present and the onset of consequences of the moral act); the physical, social, cultural and/or psychological proximity between the actor causing the harm or benefit and the effected stakeholders; and finally, the concentration of effect. These components need not all occur for moral intensity to increase and aspects of moral intensity do not always coincide. However, moral intensity will increase monotonically if there is an increase in one or more of these components.

The 2010 Deepwater Horizon/BP plc. oil disaster (herein referred to as the BP oil disaster) is an issue with a considerable degree of moral intensity driven by any or all of the six factors. As such, this example of firm misconduct provides insight into those factors that comprise moral intensity. Magnitude of consequences refers to the scale of the outcomes triggered by the event. The BP oil disaster had enormous negative social, economic and environmental consequences to a variety of stakeholders around the world (Matejek & Gössling, Reference Matejek and Gössling2014). The range of people touched by the disaster included those who lived in the affected area, those who visited there, and even those who ate seafood from the region.

The degree of social consensus became overwhelmingly strong and negative as media accounts detailed the impact of the oil disaster on communities and individuals. Social media compounded the negative reaction. Two months after the disaster, the Washington Post conducted a poll of the public’s reaction: 73 percent of respondents considered it an environmental disaster and 65 percent agreed that the government should pursue criminal charges against BP (Cohen, Reference Cohen2010). However, media coverage is never uniform. The Pew Research Center found that location affects the coverage of disasters: The US Press dominated the coverage of the BP oil disaster, while the non-US press dominated the coverage of the devastating earthquake in Haiti (Sartor, Reference Sartor2010). Press coverage both affects and reflects public opinion and so stakeholders around the world may vary in their perceived degree of social consensus.

The probability of effect was certain as the environmental damage took little time to manifest itself. Additionally, the temporal immediacy of the BP disaster was evident as the ecological disaster quickly affected the oyster fisheries and tourism as the spilt oil washed onto the shores of the states that bordered the Gulf of Mexico.

Proximity is a feeling of nearness to the people who benefit from or are harmed by the firm’s action. This can be more than mere physical proximity. Stakeholders in the affected communities, who were physically very close to the event, were also proximate psychologically, culturally and socially. Most community members felt the impact of the environmental damage, while some also suffered employment and financial difficulties because of the disaster. Even those who were able to stay employed had spouses, family members and friends whose livelihoods were affected (Gurchiek, Reference Gurchiek2010). Some people who lived far away from the oil disaster may have felt a psychological proximity if they had strong views about the fragility of the environment and the ecological effects of the oil disaster. However, other stakeholders who were more distanced geographically and psychologically from the oil disaster would not have felt the same moral imperative as those in closer proximity. Proximity is therefore an aspect of moral intensity that can cause moral intensity to vary between individual stakeholders.

The concentration of effect was very high for those individuals and communities whose entire lives were upended by the disaster. Three years after the disaster, the people who fish and the communities that rely upon them were still reeling from its impact (Smith, Reference Smith2013). Jones (Reference Jones1991) notes that concentration of effect contributes to moral intensity because it offends people’s sense of justice; individual suffering is seen to be disproportionate to the firm’s misconduct. The stories of people whose lives had been destroyed by the disaster’s effects add to the moral intensity of the misconduct.

The Subway $5 Footlong controversy, on the other hand, provides a contrast to the BP oil disaster. It was an issue with a low degree of moral intensity for most Subway stakeholders. In January 2013, an Australian man posted on Facebook a photograph of a Subway sandwich and a ruler that indicated the sandwich was only eleven inches long, sparking a social media discussion on the deceitful practice of the company. Subway responded saying that ‘Subway Footlong’ was simply a trademark name. In 2015, the company settled a class-action lawsuit with nine plaintiffs who received less than $1,000 each (Associated Press, 2015).

Although the controversy was ephemeral in social media, the Subway advertising campaign was a financial success, generating $3.9 billion in sales and causing other fast-food chains to develop similar advertising campaigns (Boyle, Reference Boyle2009; Vranica, Reference Vranica2014). This suggests that for most Subway customers (and other stakeholders, like suppliers), the magnitude of the consequences of the deceptive advertising was low or non-existent, particularly since the product was only 1-inch less than expected. Despite some degree of social consensus about the duplicity, and a fairly high probability of effect because customers were not getting what had been advertised, the psychological proximity was likely only felt by those who had strong views about false advertising or the company, as was the case with the few who later sued the company. The temporal immediacy was quite long; the advertising campaign began in 2012, and the lawsuit was settled in 2015. Finally, the concentration of effect was quite low or non-existent, since Subway sandwiches were continuously sold throughout the period. Therefore, overall, the $5 Footlong controversy seemed to have a low degree of moral intensity for most Subway stakeholders.

Another example of low moral intensity is a product recall because of mislabeling. However, some product recalls have a high level of moral intensity, such as the worldwide 2009-2010 Toyota recalls for faulty floor mats and sticking accelerator pedals, or the 2014 General Motors recalls for faulty ignition switches. These recalls had greater magnitude of consequences because the outcomes of malfunction were grave. The degree of social consensus against these automobile manufacturers also was high, as these vehicles were so widely owned that even people who did not own or operate a recalled vehicle knew other people who did.

These examples illustrate that moral intensity varies from issue to issue. Jones (Reference Jones1991) notes that moral intensity affects the recognition of a moral issue because it causes the issue to be salient. Moral intensity, however, is not the only factor that leads to moral salience. Misconduct causes a breach in the firm-stakeholder psychological contract, and the relational intensity of that psychological contract will affect the way in which that misconduct is perceived (Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997).

RELATIONAL INTENSITY

Relational intensity stems from the psychological contract between a firm and a stakeholder. A psychological contract is a subjective belief a party holds about the obligations that exist between the two parties (Rousseau & McLean Parks, Reference Rousseau and McLean Parks1993; Rousseau, Reference Rousseau1995; Robinson & Morrison, Reference Robinson and Morrison2000). A breach occurs when one party does not fulfill the unwritten promises and obligations that are implicit in a psychological contract (Rousseau, Reference Rousseau1995). Breaches in psychological contracts can have negative consequences. For example, breaches in employer-employee psychological contracts may result in adverse feelings, attitudes and behaviors by employees, which cause them to leave the firm (Dulac, Coyle-Shapiro, Henderson, & Wayne, Reference Dulac, Coyle-Shapiro, Henderson and Wayne2008). We draw upon psychological contract theory (Rousseau, Reference Rousseau1995, Reference Rousseau2011) to characterize the perceived obligations that stakeholders expect from firms and the role those subjective beliefs play when firms fail to fulfill stakeholders expectations.

Psychological contracts range from predominantly transactional to predominantly relational (McLean Parks & Kidder, Reference McLean Parks, Kidder, Cooper and Rousseau1994; Rousseau, Reference Rousseau1995; Rousseau & McLean Parks, Reference Rousseau and McLean Parks1993). Transactional contracts primarily involve economic exchanges with a quid-pro-quo perspective. They incorporate duties and obligations that are narrowly defined, such as those that exist when a supplier provides resources for a certain price. In contrast, relational contracts are more subjective and involve greater personal engagement (Rousseau & McLean Parks, Reference Rousseau and McLean Parks1993). Relational psychological contracts are linked to organizational inducements such as job security, loyalty and organizational citizenship that entail the exchange of socio-emotional currency (Robinson & Morrison, Reference Robinson and Morrison1995). They involve socio-emotional commitments between the parties, such as those that develop when an employee works for the same firm for a long period. While both transactional and relational elements can be present in a given firm-stakeholder psychological contract, the levels of each will vary. So too will the level of moral expectations (McCarthy & Puffer, Reference McCarthy and Puffer2008). Different currencies are associated with perceived infractions of psychological contracts (Rousseau & McLean Parks, Reference Rousseau and McLean Parks1993). Infractions of the terms of a transactional psychological contract tend to be viewed dispassionately because the currency involves the terms of exchange and obligations that either have or have not been broken. In contrast, a relational psychological contract is socially constructed and sensitive to subjective assessments, judgments, and emotional outcry when a breach occurs. Breaches of relational contracts touch on emotions that make stimuli more vivid (Jones, Reference Jones1991) and can lead to a variety of negative work-related outcomes (Robinson, Reference Robinson1996; Zhao, Wayne, Glibkowski, & Bravo, Reference Zhao, Wayne, Clibkowski and Bravo2007).

Emotion is a key element in trust, and it can help stakeholders decide whether or not they are willing to be vulnerable to others (Hosmer, Reference Hosmer1995). When that trust is broken under situations of vulnerability, stakeholders will react with intense feelings towards the transgressing organization, and they will view the misconduct as a morally offensive violation of the norms of the relational contract (Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997). Breaches of transactional contracts are treated more dispassionately. The lack of emotion associated with these contracts allows stakeholders to focus on the terms of exchange instead of taking the leap of faith necessary in more emotionally based relationships. As such, breaches of transactional contracts are felt less strongly than breaches of relational contracts because relational contracts carry a higher level of expectations (Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997). Footnote 2

Thus, breaches of relational contracts are hurtful to the stakeholder. Relational intensity increases as the contract moves toward the relational end of the continuum. The greater the relational intensity of the contract, the more socio-emotional elements come into play. Whereas a breach of a transactional psychological contract is a disappointment to a stakeholder, a breach of a relational psychological contract is a betrayal of trust that violates the norms of the contract. Greater relational intensity in a firm-stakeholder psychological contract will give the firm’s misconduct greater moral salience.

A MODEL OF MORAL SALIENCE

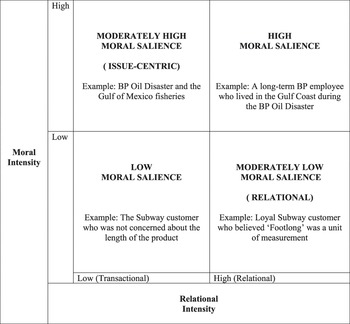

The elements of moral intensity and firm-stakeholder psychological contracts form a construct of moral salience that represents the extent to which the misconduct is morally noticeable. Figure 1 identifies organizational scenarios of moral salience based on the moral intensity of the issue and relational intensity of the firm-stakeholder psychological contract. Moral salience will differ between stakeholders, even in response to the same event. Footnote 3

Figure 1: A Model of Moral Salience Applied to Firm Misconduct.

In Figure 1, we provide an example for each quadrant using the BP Gulf oil disaster (an issue that has high moral intensity) and the Subway $5 Footlong controversy (an issue that has low moral intensity).

The lower row of Figure 1 represents issues of low moral intensity. Jones (Reference Jones1991) notes that most issues have low moral intensity; few issues satisfy all six of his factors. At the bottom left is low moral salience, characterized by low moral intensity and a transactional psychological contract. This is typified by a Subway customer who was indifferent to the actual length of a Subway sandwich or who was totally unaware of the controversy. For these stakeholders, the issue had low moral intensity because the relationship was transactional, based on an economic quid-pro-quo exchange, $5 for a Subway sandwich. In the bottom right corner is moderately low moral salience, characterized by low moral intensity and a relational psychological contract. In this quadrant would be the loyal customers who had developed a strong relational commitment with Subway. Jared Fogle contended that he lost weight eating Subway sandwiches and afterwards became a company spokesperson (Thrasher, Reference Thrasher2013). Nine individuals successfully sued the company based on misleading advertising (Associated Press, 2015). For these stakeholders, the issue, presumably, had moderately low moral salience because, while the moral intensity of the issue was low, the psychological contract was relational. Footnote 4 Relational psychological contracts are subject to emotional assessments. The shortfall in the actual length of the product was perceived as a failure of Subway’s implied promise to provide a twelve-inch sandwich.

The upper row of Figure 1 represents issues of high moral intensity. The BP oil disaster satisfies all of Jones’ (Reference Jones1991) six factors, and so is a rare example of high moral intensity. In the upper left quadrant is moderately high moral salience, characterized by high moral intensity and a transactional psychological contract. The Gulf Coast oyster fisheries whose way of life changed dramatically when oyster beds were devastated by the disaster exemplify this. These stakeholders had no prior relationship with BP and so the relational intensity was low, but the moral intensity of the misconduct was high because of the effect of the disaster on their livelihood. The upper right quadrant is high moral salience, characterized by high moral intensity and a relational psychological contract. This is exemplified by a long-term BP employee whose long tenure at the firm created high relational intensity, and who lived in the hard-hit area of the Gulf Coast among friends and family who suffered the effects of the disaster. For this employee, the misconduct had high moral intensity. The high relational psychological contract coupled with the high moral intensity of the issue suggests high moral salience—misconduct that is morally noticeable.

FIRM-STAKEHOLDER TRUST REPAIR

Trust judgments between firms and their stakeholders are formed based on selective perceptions (Harris & Wicks, Reference Harris and Wicks2010). Trust is lost based on unmet expectations of integrity, benevolence and consistency of action that are inherent in the psychological contract between the two parties. To re-establish trust, stakeholders must hold true to their promises and be consistent, acting in good faith. While there are many aspects to organizational trust, two generalized aspects are: competence-based trust and goodwill-based trust (Emsley & Kidon, Reference Emsley and Kidon2007; Harris & Wicks, Reference Harris and Wicks2010; Malhotra & Lumineau, Reference Malhotra and Lumineau2011). The former encompasses positive expectations about a partner’s ability to perform according to an agreement; the latter concerns the intentions of the other party to act in a trustworthy manner (Nooteboom, Reference Nooteboom1996).

Competence-based trust is considered the cornerstone of inter-firm alliances; in fact, competence-based trust is considered one of the most important conditions for the continuation of inter-firm relationships over multiple transactions (Faems, Janssens, Madhok, & Van Looy, Reference Faems, Janssens, Madhok and Van Looy2008). It is associated with an operational focus due to output, behavioral, and social controls. Competence-based trust is the belief that one party has in another’s technical ability to execute activities (Das & Teng, Reference Das and Teng2001).

Goodwill-based trust is an emotional belief about another party, the confidence that one party will not intentionally harm the other party (cf. Baier, Reference Baier1986). It concerns the motives of the other actor and involves aspects of integrity, benevolence, and candor. Goodwill-based trust is tied to past exchanges and requires a considerable amount of specific information acquired over long periods. From a firm’s point of view, it is demonstrated through good organizational behavior and positive social citizenship. Goodwill activities enhance a firm’s corporate image and cause stakeholders to perceive the firm in a favorable light (Sirgy, Reference Sirgy2002). Difficult to establish, goodwill is also quite fragile; it can be damaged with just a little negative information. Negative experiences can cause accumulated goodwill to decline quickly (Swanda, Reference Swanda1990).

Competence is the ability to perform some task within a specific domain or area (Zand, Reference Zand1972). Mayer, Davis and Schoorman (Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995: 717) argue that ability is a fundamental aspect of trust, so much so that competence in one area affords “that person trust on tasks related to that area.” But, an actor may not be considered trustworthy in other areas where the individual lacks competence. Consequently, when a firm breaks the trust of its stakeholders in a way that calls into question that firm’s ability to do a task properly, the firm, at a minimum, must improve and communicate its technical competence. After an oil spill occurs, an oil company needs to correct its drilling procedures and operations. Following an incident in which a rogue employee misappropriates funds, a firm needs to strengthen its internal controls and reporting procedures. After a product is recalled, a firm needs to correct its quality control processes.

Thus, the actions required to restore competence-based trust will be a function of the task in question, the one in which the firm failed. However, improving a firm’s technical competence is rarely enough. For example, Faber (Reference Faber2005) found that firms that had engaged in fraudulent reporting were not able to re-establish relationships with analysts, institutional owners or short-sellers by simply strengthening their governance structures through separation of CEO/Chair roles, increasing board independence and having more frequent audit meetings.

Beyond re-establishing competence, goodwill is needed to re-establish the organizational trust that stakeholders once had. As noted above, goodwill focuses on the intention of another to behave trustworthily (Nooteboom, Reference Nooteboom1996). Goodwill is an aspect of the moral character of the actor. It is an indicator of how much one can rely upon another, beyond the duty of fulfilling an exchange (Greenwood & Van Buren, Reference Greenwood and Van Buren2010). It takes into account cooperation (Hosmer, Reference Hosmer1995) and vulnerability (Meyerson, Weick, & Kramer, Reference Meyerson, Weick, Kramer, Kramer and Tyler1996). Therefore, goodwill becomes a key tool to show stakeholders that the firm will change following misconduct.

GOODWILL AND FIRM-STAKEHOLDER TRUST REPAIR

Referring to Figure 1, when the misconduct has low moral salience (low moral intensity and low relational intensity), the firm needs to focus on restoring competence-based trust. Transactional relationships establish trust by being faithful to binding voluntary agreements based on expertise (Baier, Reference Baier1986). When the short-lived controversy over the length of the $5 Footlong occurred, Subway used public relations and social media to re-establish brand loyalty (Vranica, Reference Vranica2014). By focusing on its expertise of delivering a submarine sandwich—meats, cheese, vegetables, and seasonings on a long roll of bread—the company demonstrated its technical competence and thereby countered the negative publicity concerning the actual length of the product. This aligns with trust research suggesting that customers value expediency and competence (Auger & Devinney, Reference Auger and Devinney2007), as well as perceptions of quality, rather than goodwill (Harris & Wicks, Reference Harris and Wicks2010).

At the other extreme, when the misconduct has high moral salience (high moral intensity and high relational intensity) the firm needs to focus on rebuilding goodwill-based trust. This is essential both to reinforce the value of the relationship, and to address the gravity of the misconduct. The trust inherent in high relational contracts builds social capital. This social capital can only be preserved if both the firm and its stakeholders maintain mutual commitment and cooperation (Adler & Kwon, Reference Adler and Kwon2002). When the firm does something that damages trust, it must make up for its misconduct, as well as mollify the emotions associated with the breach of the relational psychological contract (Robinson, Reference Robinson1996). Thompson and Bunderson (Reference Thompson and Bunderson2003: 576) note that a breach in an employer-employee psychological contract, based on high relational intensity, may occur even when the employer’s misdeed has “no bearing on how the employee is treated personally.” For the long-term BP employee who lived in the Gulf area, the contract between the employee and BP had high relational intensity and the disaster had high moral intensity. Consequently, goodwill had to be established to indicate that the company would do all it could to ameliorate the situation that it created. Following the disaster, BP provided support services and extra security for its employees, reassured its personnel that their retirement savings were secure, and encouraged retirees to participate in the spill clean-up (Leonard & Sayre, Reference Leonard and Sayre2010). Goodwill is essential in helping an employee to take pride again in being associated with the transgressing company.

Goodwill can be conceived of as representing a firm’s moral character and reputation (Swanda, Reference Swanda1990). When the firm’s misconduct has moderately high (issue-centric) moral salience, goodwill is needed in order to address the high moral intensity of the misconduct. The firm needs to engage in goodwill-trust building, even if the stakeholder has had little, if any, direct relationship with the transgressor. The oyster fisheries are in the issue-centric quadrant of Figure 1. BP’s donation of $48.5 million to various local governments to help in the promotion of the Gulf of Mexico seafood industry was an attempt to try to re-establish trust with those who were dependent upon Gulf of Mexico fishing (Burdeau & Reeves, Reference Burdeau and Reeves2012). In a similar vein, Godfrey (Reference Godfrey2005) argues that philanthropic activities can generate positive moral capital when the act itself is consistent with both the ethical values of the donor and the ethical values of the community. Similarly, activities that are perceived as genuine can help to re-establish goodwill-based trust, even if the transgressor has had no prior dealings with the affected community, as long as the “acts themselves and the imputations about the organization and its actors receive positive evaluations from affected communities and others” (Godfrey, Reference Godfrey2005: 782).

Finally, when the misconduct has moderately low (relational) moral salience, the trust that has been established through goodwill may be able to withstand a misconduct that has low moral intensity. Because these are socio-emotional contracts, a certain amount of goodwill may already exist. Consequently, the firm is not necessarily required to make a significant investment in goodwill. Relational contracts that have been developed over time may have generated a sufficient amount of goodwill to offset the low moral intensity of the misconduct. Malhotra and Lumineau (Reference Malhotra and Lumineau2011) for example, find that if goodwill has already been established, then both parties will be willing to continue the relationship after a dispute has arisen. This is analogous to Godfrey’s (Reference Godfrey2005) claim that stakeholders may give firms that develop positive moral capital the benefit of the doubt when the firm engages in bad acts. Although some investment in goodwill is needed to signal sincerity of intent, a significant goodwill investment is not required. The $5 Footlong campaign generated billions in sales for Subway, and was so successful that other fast-food chains, such as Domino’s and KFC launched similar $5 products (Boyle, Reference Boyle2009). Brand loyalty had been established (Vranica, Reference Vranica2014) and so the 11-inch controversy was short-lived. Subway was given the benefit of the doubt when it was revealed that the bread roll was an inch short of one foot in length.

Our model illustrates the variability and efficacy of goodwill in addressing different levels of moral salience and trust repair. The amount of goodwill will vary with the level of moral intensity and the level of relational intensity.

Proposition 1: The higher the moral salience of the misconduct, the greater the amount of goodwill needed for firm-stakeholder trust repair.

STAKEHOLDER CULTURE

Broader organizational factors may also influence a firm’s orientation towards its stakeholders and the use of goodwill. Stakeholder cultures, for example, are “the beliefs, values and practices that have evolved for solving stakeholder-related problems” (Jones, Felps, & Bigley, Reference Jones, Felps and Bigley2007: 142). These cultures range along a continuum from those that are individually self-interested (agency culture) to fully other-regarding (altruist culture) (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Felps and Bigley2007). The continuum is punctuated with five classifications; however, we focus on the endpoints of the continuum, which inform our model in defining the relationship between goodwill and stakeholder cultures.

At one end of the continuum is the agency stakeholder culture. In an agency stakeholder culture, managers are self-interested with no concern for others (even shareholders). Because an agency stakeholder culture is amoral, nothing is expected of managers in a moral sense. When managers fail to represent shareholders’ best interests, blame is placed on the governance mechanisms because it is understood that managers will pursue their self-interest in the absence of tight controls. Shareholders and other stakeholders only benefit from managerial actions at the agency end of the continuum when their interests are aligned with those of the managers, i.e., the benefit is simply a byproduct of corporate governance, rather than evidence of any moral intentions. An organization with an agency stakeholder culture has “an absence of moral concern for other economic actors” (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Felps and Bigley2007: 144), which leads to an absence of goodwill.

At the other end of the stakeholder culture continuum, is the altruist stakeholder culture. A firm with an altruist culture adopts a fully other-regarding perspective to all stakeholder groups. The altruist manager will treat all stakeholders fairly, respectfully, and honorably, and will not let pragmatic concerns take precedence over moral standards. A firm with this sort of orientation acknowledges its interconnections with a broad range of stakeholders (Preston & Post, Reference Preston and Post1995) that have varying interests, not all of which are economic. As such, the firm seeks to promote both social and economic welfare. The firm and the stakeholder are committed to humanistic values with a respect for rights, justice, and fairness (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Felps and Bigley2007). Altruist stakeholder cultures are likely to have a storehouse of trust and goodwill in their relationships with their stakeholders.

Like the agency stakeholder culture, the altruist stakeholder culture is an extreme that defines an endpoint. Extreme positions are not sustainable and so firms fall somewhere between the two endpoints. The endpoints, however, are useful as they help to define the relationship between goodwill and stakeholder cultures. A firm with an agency orientation is short-term and opportunistic and invests in goodwill only when self-interest dictates. Therefore, it accumulates little goodwill because any goodwill tends to be spent as soon as the need arises. An altruist firm develops goodwill with stakeholders as a matter of course. The altruist firm embraces moral principles, such as fairness, caring, honesty, benevolence, and trustworthiness. These become part of the institutionalized values of the firm and, as such, the firm with an altruist culture is less likely to act in a way that dissipates it. A store of goodwill accumulates over time as the firm follows its moral principles and thereby enhances its positive reputation (Sirgy, Reference Sirgy2002). This pre-existing supply of goodwill provides a cushion that lessens the amount of goodwill needed for repair. Robinson (Reference Robinson1996) and Malhotra and Lumineau (Reference Malhotra and Lumineau2011) found that having an initial store of trust prior to a psychological contract breach led to a lower decline in trust following the breach.

Proposition 2: The closer the stakeholder culture of the firm is to an agency (altruist) stakeholder culture the greater (the lesser) the amount of goodwill needed for firm-stakeholder trust repair.

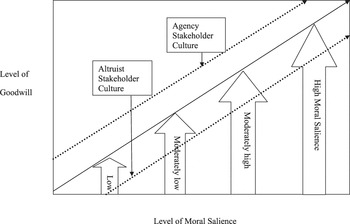

We summarize the relationship between moral salience, goodwill and the moderating effects of stakeholder culture in Figure 2. Issues with low levels of moral salience, where moral and relational intensities are low, need only re-establish their competency; goodwill is not required to repair trust. However, as the level of moral salience increases, the importance of goodwill increases to the point where goodwill becomes essential for firm-stakeholder trust repair. This is moderated by the stakeholder culture of the firm such that an altruist stakeholder culture requires less goodwill, while an agency stakeholder culture requires more.

Figure 2: Moral Salience, Goodwill, and the Moderating Effect of Stakeholder Culture.

DISCUSSION

Damage to firm-stakeholder relationships can be severe enough to pummel even the strongest of companies. However, some firms, particularly those with a stakeholder culture that is on the agency side of the continuum, may be concerned that the development of goodwill is too costly an endeavor. Godfrey (Reference Godfrey2005) makes a similar argument concerning corporate philanthropy. He contends that firms can use corporate philanthropy to generate positive moral capital with its stakeholders. However, he warns against investing in either too much or too little. “Beyond p* [the optimal level], additional philanthropic activity imposes additional costs on the firm, without generating any corresponding value; below p*, the firm leaves relational wealth not fully covered” (Godfrey, Reference Godfrey2005: 791). Similarly, over or under investing in goodwill may not be cost effective for a firm with an agency stakeholder culture. If the firm invests in too much goodwill (i.e., when goodwill is not required), then the firm is incurring additional costs without reaping any benefits. If it invests in too little, it is failing to rebuild the bridge with its stakeholders. We realize that, in practice, managers may not be introspective enough to recognize the moral intensity of a misconduct or even the relationships the firm has with its stakeholders (i.e., whether transactional or relational). Nevertheless, firms that fail to acknowledge moral salience are more likely to choose a suboptimum goodwill repair technique.

Additionally, as we discussed, social judgments and reactions to misconduct will vary for different stakeholders. This may also affect a firm’s ability to respond in the best way. Furthermore, firm-stakeholder psychological contracts may vary beyond the basic transactional and relational distinctions. For example, Bingham et al. (2014) and Thompson and Bunderson (Reference Thompson and Bunderson2003) suggest the inclusion of ideological currency in the psychological contract perspective. This currency is the credible commitment or pursuit of a valued cause by an organization that is exchanged in the psychological contract. The relationship between ideological psychological contracts and an issue’s moral intensity could prove a fruitful direction for future research, particularly with regard to employee stakeholders who react strongly to a firm’s misconduct and therefore require extraordinary goodwill to repair trust.

Furthermore, future research might expand the application of our model to identify how trust repair might vary between a transgressing firm and its normatively legitimate versus its derivatively legitimate stakeholders (Phillips, Reference Phillips2003a, Reference Phillips2003b). In this study, we adopt a broad approach to stakeholders, and we define the firm-stakeholder relationship in terms of the psychological contract in conjunction with the moral intensity of the issue. However, the normative approach to stakeholder theory suggests that a firm’s stakeholders are those parties to whom the firm has moral obligations. This narrow definition of stakeholder includes only stakeholders to whom the firm has direct moral obligations—stakeholders that are normatively legitimate, such as shareholders and employees (Phillips, Reference Phillips2003a). The obligations that a firm owes to these stakeholders are integral to building an atmosphere of organizational trustworthiness and accountability (Greenwood, Reference Greenwood2007; Greenwood & Van Buren, Reference Greenwood and Van Buren2010; Phillips, Reference Phillips1995, Reference Phillips2003b; Scott, Reference Scott2002). Future research might consider different types of stakeholders, and the variation of moral salience with different stakeholder classifications.

We recognize that the stakeholder culture of a firm may be difficult to identify in practice. Jones et al. (Reference Jones, Felps and Bigley2007) reference early empirical work that provides evidence of such identification, and this is a promising area for new research. Using our model of moral salience and trust repair, future researchers might contrast the ways in which different stakeholder cultures attempt to rebuild trust with the use of goodwill.

Our focus has been on misconduct. However, it is important to note that moral salience can apply to situations that are both positive and negative. According to Jones (Reference Jones1991) moral intensity can refer to actions that benefit as well as actions that harm other people. Similarly, psychological contracts evolve from positive as well as negative actions. We leave it to others to examine the moral salience of positive situations, when firm behavior is morally affirmative and noticeable.

CONCLUSION

Rebuilding trust is important to the survival of a firm following misconduct. We propose a new construct called moral salience, which we define as the extent to which firm behavior is morally noticeable. Moral salience is at the heart of trust repair. The greater the moral salience the greater is the need for an investment in goodwill to re-establish trust between the firm and its stakeholders.

The American Red Cross was subject to strong criticism for its handling of the Hurricane Katrina refugees. However, with a store of goodwill dating back to the World War I War Fund and the Roll Call campaigns, the Red Cross has been able to navigate its way back from a potentially disastrous situation. It has re-established relationships with funding sources, local and national communities, employees, and the federal government. As CEO Bonnie McElveen-Hunter acknowledged in 2006, “when an organization is given such an important and sacred trust by the American people, it must do everything in its power not only to ensure that it is worthy of this trust but to deliver in all areas of responsibility” (McElveen-Hunter, Reference McElveen-Hunter2006: 1).

BP, on the other hand, has had a tougher time restoring trust, despite spending over $50 billion for costs associated with the spill including the establishment of a $20 billion fund for victims of the disaster, as well as some executive housecleaning, and its return to profitability just one year after the crisis (Mclean & Chapple, Reference McLean and Chapple2015). When BP CEO Tony Hayward said, “I’d like my life back” when speaking to the families of eleven men who died when the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig exploded, the outrage expressed by both stakeholders and observers was palpable (Mouawad & Krauss, Reference Mouawad and Krauss2010: A1). Technical competence had been re-established, but an investment in goodwill had yet to be made.

All misconducts are not created equal. When a firm commits misconduct, it must immediately correct its faulty procedures by improving its technical competence and communicating that improvement. Then, depending upon the degree of moral salience, the firm must make an investment in goodwill. We offer this framework in recognition of the additional challenges inherent in relationships that are forged from deep bonds and in undoing damage that is severe. In these situations, competence is not enough. The greater the level of moral salience, the greater is the need to incorporate goodwill into trust repair.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Associate Editor Heather Elms and acknowledge helpful reviews from three anonymous reviewers. Additionally, we are grateful to Harry Van Buren and Mark Schwartz, who reviewed earlier versions of this work. All the authors contributed equally; the names are listed alphabetically.