In today’s global environment, employees are likely to interact with people from diverse cultural backgrounds (Markman, Reference Markman2018). As a result, employers are seeking employees high in cross-cultural capabilities. Since international business opportunities continue to expand and are pursued in every remote corner of the globe (Tung & Verbeke, Reference Tung and Verbeke2010), firms hoping to leverage a competitive advantage are transferring their highly-skilled and most culturally–astute workers to tackle new assignments abroad (Hendry, Reference Hendry1999). Such corporate transferees (i.e., expatriates) are estimated to exceed one-half million worldwide (Aon Inpoint, 2017) and are predicted to grow annually by 2.8 percent (Finaccord, 2018).

Despite the growing popularity and necessity of expatriates to possess cross-cultural capabilities, the context of an international assignment may foster potential downsides of being too culturally literate: opportunism and ethical relativism. As agency and empowerment replace day-to-day management of expatriates, the inherent asymmetric information between the expatriates, firm, and customer can make opportunism problematic (Connelly, Hitt, DeNisi, & Ireland, Reference Connelly, Hitt, DeNisi and Ireland2007). Additionally, because ethical perceptions frequently differ across cultures (e.g., Franke & Nadler, Reference Franke and Nadler2008), people from different cultures often “do not see eye-to-eye in their moral appraisals” (Forsyth, O’Boyle, & McDaniel, Reference Forsyth, O’Boyle and McDaniel2008: 814). Thus, the importance for expatriates to possess the capabilities to adapt to new cultural environments and complex ethical systems (Dau, Reference Dau2016), while also aligning with the interests of their firms and customers, has never been greater.

The study of cross-cultural capabilities has largely viewed them as leading to desirable outcomes (Matsumoto & Hwang, Reference Matsumoto and Hwang2013). This is especially the case for cultural intelligence (CQ), the cross-cultural capability under investigation in the current study. CQ, defined as the capability to manage effectively in intercultural settings (Earley & Ang, Reference Earley and Ang2003), is primarily associated with positive psychological, behavioral, and performance outcomes (see Ott & Michailova, Reference Ott and Michailova2018, for a more recent review, as well as Table 1, discussed below).

Table 1: Selected Outcomes of Metacognitive and Cognitive CQ

Note. The list of references cited in Tables 1 and 2 is available as supplementary document online.

a We report these studies for comprehensiveness as the topics and findings may pertain to the current paper. However, we note that CQ is not measured with its components but as an overall construct where the individual impact of the theoretically different CQ facets cannot be parsed out. While we specifically summarized metacognitive and cognitive CQ studies in this table, we find a similar lack of negative outcomes and ethical considerations when considering motivational and behavioral as well as overall CQ.

The purpose of our study is to explore whether the possession of CQ holds a dark side. The general theory of confluence (Zardkoohi, Harrison, & Josefy, Reference Zardkoohi, Harrison and Josefy2017) illustrates how a potential dark side of CQ—opportunism—can coexist with a bright side—customer relationship performance. In addition, the concept of ethical relativism, defined as the belief that morality depends on the situation and personal perspective (Forsyth, Reference Forsyth1980), sheds light on the relationships between CQ, opportunism, and customer relationship performance.

Our contributions to the international business ethics literature are three-fold. First, we apply the general theory of confluence and extend it toward an international context to explore the potential multifaceted nature of CQ. Specifically, how can expatriates high in CQ excel in relationships with their customers, yet act opportunistically? Prior research has examined the dark sides of other types of personal resources, such as emotional intelligence (O’Connor & Athota, Reference O’Connor and Athota2013), cross-cultural exposure and experiences (Hong & Cheon, Reference Hong and Cheon2017; Lu, Quoidbach, Gino, Chakroff, Maddux, & Galinsky, Reference Lu, Quoidbach, Gino, Chakroff, Maddux and Galinsky2017), and moral integrity on relationship commitment (Li, Zhang, & Yang, Reference Li, Zhang and Yang2018). Our research is the first to provide and empirically examine an encompassing theoretical rationale for a dark side of CQ. An understanding of the dark side of CQ is important (Fang, Schei, & Selart, Reference Fang, Schei and Selart2018; Rockstuhl & Van Dyne, Reference Rockstuhl and Van Dyne2018) because opportunistic behavior can lead to negative firm-level outcomes (Lee, Reference Lee1998; Luo, Liu, Yang, Maksimov, & Hou, Reference Luo, Liu, Yang, Maksimov and Hou2015).

Second, we respond to calls that advance our understanding of international business ethics (Javalgi & Russell, Reference Javalgi and Russell2018; Newman, Round, Bhattacharya, & Roy, Reference Newman, Round, Bhattacharya and Roy2017) and specifically the impact of the international context on the formation of ethical relativism (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Quoidbach, Gino, Chakroff, Maddux and Galinsky2017). Melé and Sánchez-Runde (Reference Melé and Sánchez-Runde2013: 682) note that the “debate on ethical relativism and universal ethics … has important consequences for both business ethics and cross-cultural management,” and no greater context than customer-facing expatriates is likely to exist. Whereas prior research examines the effects of ethical relativism on customer-related outcomes (e.g., Cadogan, Lee, Tarkiainen, & Sundqvist, Reference Cadogan, Lee, Tarkiainen and Sundqvist2009), we extend this work into an expatriate and cross-cultural CQ context. In these contexts, the possibility of unethical behavior may be high because expatriates’ perceptions are more subjective than in a domestic situation (Arikan, Reference Arikan2018; Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Hitt, DeNisi and Ireland2007).

Finally, we also examine customer relationship performance as a positive outcome of CQ. While the role of culture in customer interactions is well documented (e.g., Laroche, Ueltschy, Abe, Cleveland, & Yannopoulos, Reference Laroche, Ueltschy, Abe, Cleveland and Yannopoulos2004), cross-culture researchers have paid limited attention to CQ’s impact on customer outcomes. Magnusson, Westjohn, Semenov, Randrianasolo, and Zdravkovic (Reference Magnusson, Westjohn, Semenov, Randrianasolo and Zdravkovic2013) call for research on how CQ can address customer performance shortcomings. Similarly, Presbitero (Reference Presbitero2016) calls for an examination of how CQ helps satisfy the needs of customers. We address these calls by examining expatriates’ CQ and customer-facing work performance.

This manuscript proceeds as follows: The next section introduces literature relevant to our study. We then propose an extension of the general theory of confluence into the cross-cultural context as a basis for hypotheses development. We develop our field study to test the hypotheses on a sample of expatriates (Study 1). Next, we corroborate results, and propose and test additional hypotheses by means of experimental designs, while extending the generalizability of our study to other cross-cultural situations (Studies 2, 3, and 4). The paper concludes with the discussion of theoretical and managerial implications, along with suggestions for future research.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Cultural Intelligence

Cultural intelligence has a positive impact on a wide array of individual and firm outcomes (Ott & Michailova, Reference Ott and Michailova2018). While negative outcomes of having CQ are rare (see overview in Table 1), interest in its potential dark side has been increasing in academia. Recent calls to explore whether high-CQ individuals may capitalize on their comprehensive cross-cultural knowledge in negotiations (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Schei and Selart2018; Imai & Gelfand, Reference Imai and Gelfand2010) or create other detrimental effects in international contexts is increasing (Rockstuhl & Van Dyne, Reference Rockstuhl and Van Dyne2018).

CQ is composed of the four distinctive dimensions of metacognition, cognition, motivation, and behavior (Earley & Ang, Reference Earley and Ang2003). As CQ is conceptually framed around elements of thinking and doing, Bücker, Furrer, and Peeters Weem (Reference Bücker, Furrer and Peeters Weem2016) group the four CQ capabilities into mental (metacognitive and cognitive CQ) and action (motivational and behavioral CQ) components. The mental dimension presents an individual’s cross-cultural awareness as well as general and context-specific knowledge. The action factor reflects the interest in cross-cultural encounters as well as the appropriate verbal and nonverbal behavior (Bücker, Furrer, & Lin, Reference Bücker, Furrer and Lin2015).

We focus on the mental CQ perspective because it helps understand expatriates’ intentions and actions (opportunism and customer relationship performance) as well as morals (ethical relativism). In the context of expatriation, the mental components of CQ take on elevated importance, especially when the two are considered in conjunction (Thomas, Liao, Aycan, Cerdin, Pekerti, Ravlin et al., Reference Thomas, Liao, Aycan, Cerdin, Pekerti, Ravlin, Stahl, Lazarova, Fock and Arli2015). In order to have the capacity or impetus to act, expatriates must first be able to interpret the environment, understand the disparate cultural stimuli, and catalog the knowledge for potential future use. Thus, cognitive and metacognitive CQ may enhance each other. For example, cognitive CQ may strengthen cultural awareness (i.e., metacognitive CQ) through increased cultural knowledge. Metacognitive CQ may foster higher levels of cultural knowledge by reflecting on cross-cultural experiences (Rockstuhl & Van Dyne, Reference Rockstuhl and Van Dyne2018). In their recent meta-analytic review, Rockstuhl and Van Dyne (Reference Rockstuhl and Van Dyne2018) found that metacognitive and cognitive CQ, but not motivational or behavioral CQ, predict intercultural judgment and decision-making. As judgment and decision-making refer to selecting between alternative strategies while taking into account the potential consequences (Starcke & Brand, Reference Starcke and Brand2016), metacognitive and cognitive CQ are particularly relevant for our framework.

Opportunism

Individuals make decisions and act to further their own goals and objectives. However, an ethical line exists between working toward success and working toward individual advancement at all costs. Opportunism can be defined as “self-interest seeking with guile” (Williamson, Reference Williamson1993: 97). Jap, Robertson, Rindfleisch, and Hamilton (Reference Jap, Robertson, Rindfleisch and Hamilton2013) note that while economic activity is inherently replete with self-interested actions, the aspect of guile suggests dishonest or unethical behavior and gives opportunism a negative connotation. Opportunism may involve behaviors such as “the dissemination of incomplete and misleading information, aiming to conceal or disguise reality in order to defraud or confuse others” (Sakalaki, Richardson, & Thépaut, Reference Sakalaki, Richardson and Thépaut2007: 1181). It can be passive (weak-form opportunism), such as withholding information or neglecting duties, as well as active (strong-form opportunism), such as misrepresenting facts and violating promises or contracts (Wathne & Heide, Reference Wathne and Heide2000). Opportunism can inhibit cooperative effort, increase uncertainty, and hamper commitment or reciprocity (Luo, Reference Luo2006). This harms firm performance and relationships between employees, managers, and customers.

Besides relying on contractual or relational breaches in determining opportunism, recent literature notes the subjectivity of opportunism and the factors and judgments shaping it (Arikan, Reference Arikan2018). Specifically, opportunistic behavior may be in the eye of the beholder, because “victims are more likely to assess a given behavior as opportunistic than transgressors, and their judgments do not relate to the underlying factors in the same way as the victims’ judgments” (Arikan, Reference Arikan2018: 1). This divergence in perceived opportunistic behavior may be a result of varying understandings and interpretations of the contract.

The expatriate context may be particularly germane for opportunistic behavior because (1) cross-cultural differences make monitoring and enforcing stakeholder interests more difficult (Cavusgil, Deligonul, & Zhang, Reference Cavusgil, Deligonul and Zhang2004) and (2) differing cultural values and ethical perceptions make it more subjective. Expatriates who understand cross-cultural differences (e.g., high in metacognitive and cognitive CQ) can more easily interpret cultural cues, choose between alternative actions, and understand their consequences (Ang, Van Dyne, Koh, Ng, Templer, Tay et al., Reference Ang, Van Dyne, Koh, Ng, Templer, Tay and Chandrasekar2007). Therefore, exploring expatriates’ potential and propensity to act opportunistically and understanding their perception of opportunism is relevant to business ethics theory and practice.

Customer Relationship Performance

At the heart of every expatriate assignment is the desire of the multinational enterprise (MNE) to increase market penetration, revenue, and other objective metrics. Thus, MNEs need to select individuals who can quickly “adjust their behavior to the host culture” (Shin, Morgeson, & Campion, Reference Shin, Morgeson and Campion2007: 77). This adjustment helps expatriates build relationships with local customers and meet expectations of both the customer and the firm. Going beyond loyalty, customer relationship performance captures the quality or health of the relationship between the expatriate and the customer. It is contextualized by the satisfaction the expatriate delivers in servicing the customer’s needs (Rapp, Trainor, & Agnihotri, Reference Rapp, Trainor and Agnihotri2010). Individuals who possess the capabilities to obtain information, create knowledge, and manage relationship quality tend to increase customer relationship performance (Menguc, Auh, & Uslu, Reference Menguc, Auh and Uslu2013; Park, Kim, Dubinsky, & Lee, Reference Park, Kim, Dubinsky and Lee2010). An increase in customer relationship performance positively affects individual and firm performance (Panagopoulos, Johnson, & Mothersbaugh, Reference Panagopoulos, Johnson and Mothersbaugh2015).

Customer relationship performance is a common measure in contexts where individuals operate as boundary spanners between their firm and its customers. However, as expatriates are not only boundary spanners between their firms and the customer, but also between countries and cultures, gaining objective measures of relationship quality or satisfaction can be extremely difficult. While each customer’s decision to be a repeat customer is the ultimate signal of customer relationship performance, the expatriate’s perception of customer relationship performance determines how much to invest in each relationship in order to continue meeting stakeholder expectations (Mullins, Ahearne, Lam, Hall, & Boichuk, Reference Mullins, Ahearne, Lam, Hall and Boichuk2014). Incongruence between perception and reality may hamper firm performance. Thus, expatriates’ metacognitive and cognitive CQ may be vital in engendering an accurate assessment of the needs of a culturally diverse customer. The health of the relationship makes expatriate-assessed customer relationship performance a valuable outcome for this study.

Ethical Relativism

Personal ethical perceptions underlie any proclivity for opportunistic behavior in customer relationships. Forsyth (Reference Forsyth1980) juxtaposed idealism with relativism to separate individuals into four ethical ideologies: situationists, subjectivists, absolutists, and exceptionists. Each characterizes how an individual faced with a decision might seek to justify an acceptable course of action based upon a relatively high or low position on each factor. Similarly, under ethics positions theory, an individual’s ethical perspective will influence moral judgments and actions in ethical dilemmas (Forsyth, Reference Forsyth1980; Wang & Calvano, Reference Wang and Calvano2015).

One of the most important dimensions of ethical behavior is ethical relativism, which contrasts with the notion of universal morality and focuses instead on “flexible conceptions of right and wrong based on context” (Valentine & Bateman, Reference Valentine and Bateman2011: 157). Demuijnck (Reference Demuijnck2015: 820) notes that such descriptive relativism is “not only widely accepted, but also taught as standard in business schools and training sessions at multinational corporations.” Individuals who apply a relativistic view recognize that there are many different ways to look at morality, and believe that morality ultimately depends on personal perspective (Forsyth, Reference Forsyth1980). The impact of such a view is likely heightened when individuals “living and working in cultural contexts whose moral practices and pronouncements seem, at least initially, incoherent and arbitrary … find themselves in cultures where their personal conceptions of morality are at odds with the moral actions and judgments of those around them” (Forsyth et al., Reference Forsyth, O’Boyle and McDaniel2008: 828). Expatriates’ relativistic ethical views may, thus, increase the possibility of opportunistic behavior and therefore moderate the proposed effects of metacognitive and cognitive CQ.

The General Theory of Confluence

The general theory of confluence is a novel but comprehensive theoretical framework that, while relying on the basic tenets of agency theory, extends it to take into account the effect of agency problems on third-party stakeholders (Zardkoohi et al., Reference Zardkoohi, Harrison and Josefy2017). The general theory of confluence accounts for potential three-way problems and a wide range of situations and contexts with complex and multidimensional sets of relationships. Specifically, the general theory of confluence considers three broad problems to the principal-agent relationship: agency problems, principal problems, and confluence problems (Zardkoohi et al., Reference Zardkoohi, Harrison and Josefy2017). When the agent’s and principal’s interests align (i.e., confluence of interest between principal and agent), they can choose to collude at the expense of the third party. Our research context touches on two of the problems: the agency and the confluence problems.

First, an agency problem arises because expatriate assignments are characterized by high autonomy, information asymmetry, transaction costs, and monitoring difficulties due to large cultural and geographic distances. Expatriates can develop new information by cultivating local networks that increase their marketability and bargaining power (Yan, Zhu, & Hall, Reference Yan, Zhu and Hall2002). Therefore, firms have little choice but to trust expatriates not to act in their personal interests at the expense of the organization. Whether expatriates fulfill that role is, to a large degree, at their discretion, and costs associated with such autonomy are often challenging to quantify.

Second, the expatriate context also triggers a confluence problem, albeit not between the principal (i.e., MNE) and agent (i.e., expatriate) but between the agent and the third-party stakeholder (i.e., customer). This alternative pairing is possible because of the dynamism and the complexity of the context. According to the general theory of confluence, confluence problems that harm the customer seem most likely to occur when outcomes can be precisely quantified and information is symmetric between the MNE and expatriate (Zardkoohi et al., Reference Zardkoohi, Harrison and Josefy2017). However, the expatriate context (or perhaps any cross-cultural context) is precisely the opposite scenario because outcomes are hard to measure and information is asymmetric. Thus, expatriates have latitude to collude with the customer at the expense of the MNE in order to take advantage of short-term opportunities (Sewchurran, Dekker, & McDonogh, Reference Sewchurran, Dekker and McDonogh2019). The general theory of confluence further suggests that third-party effects may manifest as costs either directly from intentional opportunistic behavior or indirectly without intent. For example, expatriates may intentionally harm the MNE by taking bribes or shirking duties, but also indirectly by offering customers discounts or better contractual conditions.

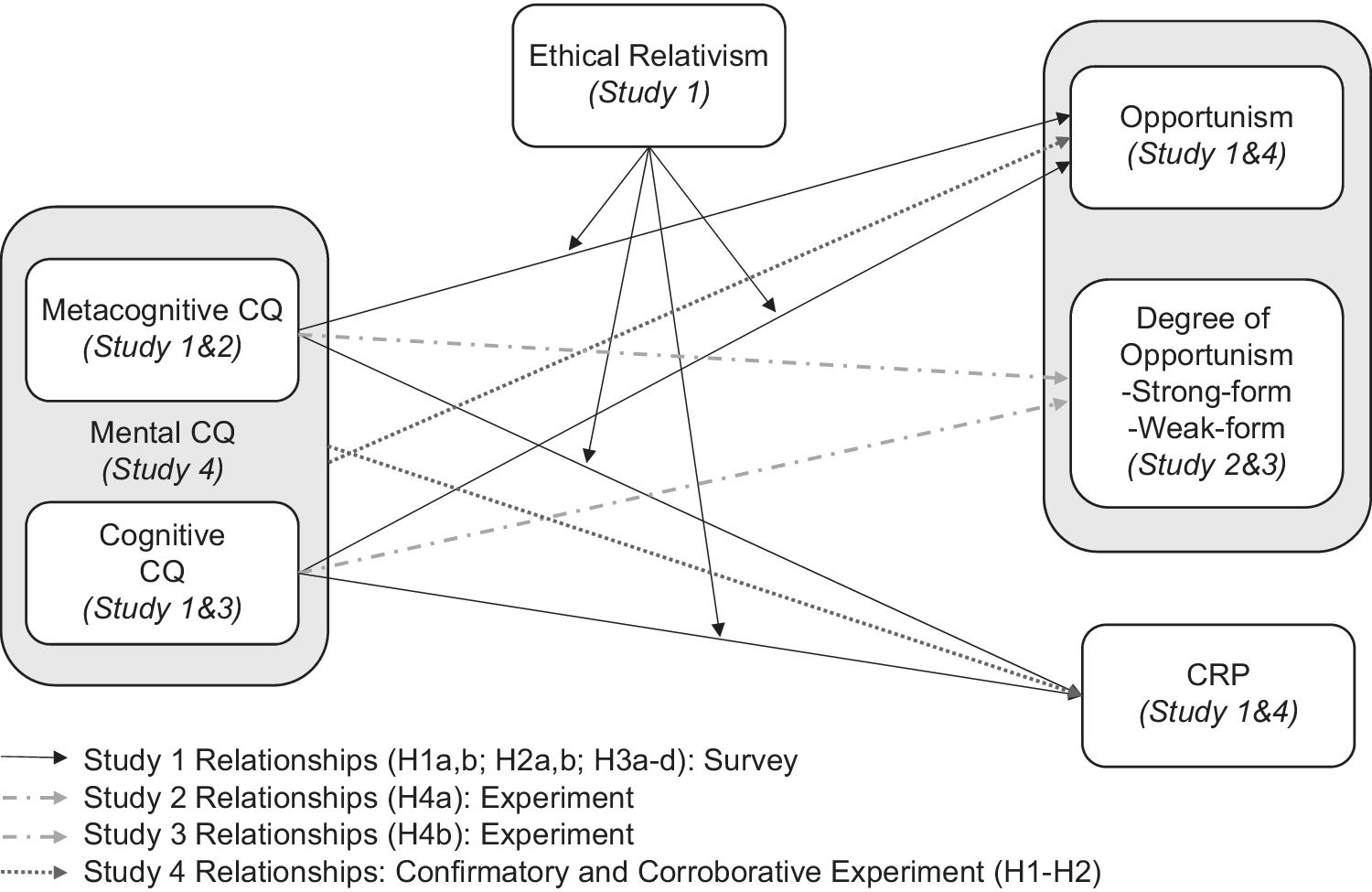

In conclusion, the general theory of confluence provides us with a framework explaining how and why expatriates may act opportunistically against their employer and have the discretion to collude (Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Hitt, DeNisi and Ireland2007) with a customer at the expense of the MNE (Zardkoohi et al., Reference Zardkoohi, Harrison and Josefy2017). Furthermore, it allows us to account for the impact of expatriates’ cross-cultural capabilities as these may enhance the possibility of expatriates acting upon agency and confluence issues. Thus, as foreign employment stimulates the development of metacognitive and cognitive CQ (Crowne, Reference Crowne2008), and the international context may catalyze ethical relativism and opportunistic behavior (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Quoidbach, Gino, Chakroff, Maddux and Galinsky2017), CQ is not solely a positive employee attribute. We now turn to the potential “dark side” of metacognitive and cognitive CQ to develop our hypotheses before proceeding with the “bright side” and other important ethical considerations. Figure 1 presents on overview of our theoretical model and the four studies that test it.

Figure 1: Theoretical Model

HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

The Dark Side: Metacognitive and Cognitive CQ and Opportunism

Consistent with the agency dimension of the general theory of confluence, if control mechanisms do not fully align the incentives of agents with the interests of stakeholders (e.g., the firm or the customer), when autonomy is high and information is asymmetric, self-interested behavior is likely to occur (Zardkoohi et al., Reference Zardkoohi, Harrison and Josefy2017). Also, as opportunism may be subjective (Arikan, Reference Arikan2018) and expatriates high in mental CQ are able to integrate multiple cultural perspectives, they may perceive more short-term opportunities and may be more likely to justify their self-serving behavior (Sewchurran et al., Reference Sewchurran, Dekker and McDonogh2019).

Individuals high in metacognitive CQ possess the cognitive flexibility and awareness to easily assess and adjust to the cross-cultural situation at hand. Especially when facing cultural discrepancies (Gelbrich, Stedham, & Gäthke, Reference Gelbrich, Stedham and Gäthke2016), they can plan ahead, recognize how culture affects their own behavior, and actively adjust their thinking about the other culture (Van Dyne, Ang, Ng, Rockstuhl, Tan, & Koh, Reference Van Dyne, Ang, Ng, Rockstuhl, Tan and Koh2012). This advanced planning makes it more likely that they will find ways to utilize their cultural knowledge to bend moral rules. They may deceive or manipulate their counterparts in order to collude with one party against another in order to achieve their objectives (in line with the confluence dimension of the general theory of confluence). Additionally, they will be able to adjust their thinking about how culture is affecting the situation, leading to more opportunities for self-interested behavior. For example, expatriates high in metacognitive CQ may confront a culture with a more tolerant view of bribery. Expatriates grappling with this cultural discrepancy may engage in a form of performance enhancing arbitrary corruption (Gelbrich et al., Reference Gelbrich, Stedham and Gäthke2016) by either planning ahead of the interaction to take advantage of the culture of bribery or during the deal by accepting kickbacks at the expense of the customer or their employer. Thus, we posit:

Hypothesis 1a: Metacognitive CQ has a positive relationship with opportunism.

Individuals high in cognitive CQ possess the general but also context-specific cross-cultural knowledge that enables them to interact easily with individuals from different cultures. Specifically, possessing cross-cultural knowledge decreases expatriates’ uncertainty (Hammer & Martin, Reference Hammer and Martin1992) while at the same time it increases their knowledge advantage and thus information asymmetry. Since the general theory of confluence suggests that information asymmetry creates incentives for opportunistic behavior (Mishra, Heide, & Cort, Reference Mishra, Heide and Cort1998; Zardkoohi et al., Reference Zardkoohi, Harrison and Josefy2017), we expect those high in cognitive CQ to behave more opportunistically. For example, different cultures have different buyer-seller negotiation styles, and some are more open to bargaining than others (Graham, Kim, Lin, & Robinson, Reference Graham, Kim, Lin and Robinson1988). Expatriates high in cognitive CQ will know if bargaining is expected in a given culture. If they recognize that it is expected, they may withhold information about the product or competitors that could provide leverage for customers, or collude with customers against the firm (e.g., Murnighan, Babcock, Thompson, & Pillutla, Reference Murnighan, Babcock, Thompson and Pillutla1999). Thus, we posit:

Hypothesis 1b: Cognitive CQ has a positive relationship with opportunism.

The Bright Side: Metacognitive and Cognitive CQ and Customer Relationship Performance

In a customer relationship setting, it is essential for expatriates to establish personal connections with customers. Specifically, metacognitive and cognitive CQ may enable expatriates to adopt diverse negotiation heuristics (Caputo, Ayoko, Amoo, & Menke, Reference Caputo, Ayoko, Amoo and Menke2019; Imai & Gelfand, Reference Imai and Gelfand2010), build customer loyalty (Paparoidamis, Tran, & Leonidou, Reference Paparoidamis, Tran and Leonidou2019), and effectively share knowledge (Chen & Lin, Reference Chen and Lin2013). This communication involves discussing benefits of services and products offered as well as considering the concerns of the customer. This may seem to contradict our earlier arguments that higher levels of metacognitive and cognitive CQ may lead expatriates to act opportunistically. However, it is important to distinguish exactly which opportunistic behavior is present and against whom. Apropos of the confluence dimension of the general theory of confluence, expatriates may collude with the firm against other stakeholders, but also may conspire with customers against the firm. Shirking company duties, taking bribes, or offering higher discounts may increase the customer’s perceived value at the cost of the firm.

Individuals high in metacognitive CQ seem particularly well-equipped to deal with culturally different customers due to their awareness and cognitive flexibility. Simintiras and Thomas (Reference Simintiras and Thomas1998) suggest that cross-cultural employees need cultural awareness to be able to anticipate and understand behaviors within the culturally diverse environment. High metacognitive CQ individuals are proactive and understand the cultural mindset of their culturally diverse customers (Van Dyne et al., Reference Van Dyne, Ang, Ng, Rockstuhl, Tan and Koh2012). This increased consciousness and empathy may improve perceived dependability and reduce behavioral uncertainty. In addition, expatriates can adjust their strategies in response to new inputs (Hansen, Singh, Weilbaker, & Guesalaga, Reference Hansen, Singh, Weilbaker and Guesalaga2011). They may be more likely to notice signs of uncertainty or distrust from the customers and act to remedy these cultural misunderstandings. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 2a: Metacognitive CQ has a positive relationship with customer relationship performance.

Individuals high in cognitive CQ are likely to perform better in customer-facing roles through improved cultural adaptation (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Singh, Weilbaker and Guesalaga2011). Specifically, in line with general theory of confluence’s agency scenario, they can develop and cultivate new knowledge about their cultural environment. The possession of cultural knowledge can reduce misunderstandings with individuals from other cultures (Wiseman, Hammer, & Nishida, Reference Wiseman, Hammer and Nishida1989). This effective communication, in turn, may save the customer time, energy, and emotional frustration. Context-specific knowledge is likely to improve the perceived ease of doing business with culturally diverse individuals, while general knowledge can enable the expatriate to develop an environment of trust (Rockstuhl & Ng, Reference Rockstuhl, Ng, Ang and Van Dyne2008). Additionally, knowledge regarding cultural expectations should enable expatriates to appear more dependable and reduce customers’ uncertainty. Thus, we posit:

Hypothesis 2b: Cognitive CQ has a positive relationship with customer relationship performance.

The Ethical Side: The Moderating Role of Ethical Relativism

Numerous studies have documented the negative dispositional and transgressional effects of ethical relativism (see Table 2 for an overview). Further complicating matters in the international marketplace is the stark reality that a “substantial variation in standards (formal and informal) for business ethics across national boundaries” exists (Windsor, Reference Windsor2004: 734). The diversity of ethical frameworks that collide when employees and customers from different cultures are brought together suggests that firms must confront a new set of problems. For instance, Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Quoidbach, Gino, Chakroff, Maddux and Galinsky2017) found that individuals with international experience think in a more morally relativistic manner, which leads to immoral behavior.

Table 2: Selected Negative Outcomes of Individuals’ Ethical Relativism in the (International) Business Context

Negative transgressional effects of ethical relativism (e.g., opportunism) may increase when paired with high levels of metacognitive and cognitive CQ. Individuals who subscribe to ethical relativism may judge their own behaviors based on contextual factors rather than on moral absolutes (Valentine & Bateman, Reference Valentine and Bateman2011). Thus, ethical relativists find it easier to rationalize and justify their unethical behavior (Henle, Giacalone, & Jurkiewicz, Reference Henle, Giacalone and Jurkiewicz2005). Specifically, when the awareness and knowledge of cross-cultural differences interact with this propensity to justify personal deceptive behavior, the likelihood of opportunism increases. Expatriates high in metacognitive and cognitive CQ may not only perceive ethics to be relativistic but also justify their behavior under the disguise of cultural adjustment. Cognitive flexibility and awareness, as well as cultural knowledge of different moral beliefs, may foster self-serving interpretations of ethical norms. Thus, we posit:

Hypothesis 3a: Ethical relativism moderates the relationship between metacognitive CQ and opportunism, such that the positive relationship is enhanced for those with higher levels of ethical relativism.

Hypothesis 3b: Ethical relativism moderates the relationship between cognitive CQ and opportunism, such that the positive relationship is enhanced for those with higher levels of ethical relativism.

While we suggest that ethical relativism further increases opportunism, the same mechanism may decrease an expatriate’s customer relationship performance. Although the expatriate and customer may collude against the firm (Zardkoohi et al., Reference Zardkoohi, Harrison and Josefy2017), the two parties may not see eye to eye in their ethical evaluations or moral justifications. Ethically relativistic expatriates may not meet the ethical expectations of culturally different customers, as morality depends on personal perspectives (i.e., they will exhibit lower ethical sensitivity; Sparks & Hunt, Reference Sparks and Hunt1998). Expatriates may use their metacognitive and cognitive CQ not to adapt to local ethical standards but to further their own interests resulting in a poor customer experience. Also, relativists are less likely to identify ethical issues or incongruences in ethical beliefs (Valentine & Bateman, Reference Valentine and Bateman2011). By decreasing honesty and integrity and potentially creating an incongruence in moral beliefs, ethical relativism may decrease the positive relationship between expatriates’ metacognitive and cognitive CQ and customer relationship performance. Thus, we posit:

Hypothesis 3c: Ethical relativism moderates the relationship between metacognitive CQ and customer relationship performance, such that the positive relationship is attenuated for those with higher levels of ethical relativism.

Hypothesis 3d: Ethical relativism moderates the relationship between cognitive CQ and customer relationship performance, such that the positive relationship is attenuated for those with higher levels of ethical relativism.

STUDY 1: FIELD STUDY OF THE DARK, BRIGHT, AND ETHICAL SIDES OF CQ

Study 1 examines whether metacognitive and cognitive CQ enhance opportunistic behavior (H1a–b) and customer relationship performance (H2a–b) in expatriates using a field study. Further, we investigate whether these effects are moderated by ethical relativism (H3a–d).

Data and Sample

The sample was comprised of 230 expatriates working in the United States. In order to participate, respondents had to be currently on an expatriate assignment and sent by their company to work abroad for at least three months and up to five years. The expatriates came from sixty-two home countries, were predominantly male (60 percent), and on average thirty-three years old. They had been with their company for six years and had averaged three expatriate assignments (including the current one). They worked in predominantly service firms.

Measures

We used established Likert-type scales to measure the constructs (see Table 3 for the items). While respondents were asked to evaluate most statements on scales ranging from 1 to 7 (strongly disagree–strongly agree), the opportunism measure asked for evaluations from 1 to 5 (strongly disagree–strongly agree) because using alternative response scales may reduce common method bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003).

Table 3: Scales and Loadings (Study 1)

Note. Statistics in the right-hand column are standardized loadings. AVE = average variance extracted; CR = composite reliability (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981).

We measured metacognitive and cognitive CQ with the two mental dimensions of the multidimensional CQ scale developed by Ang et al. (Reference Ang, Van Dyne, Koh, Ng, Templer, Tay and Chandrasekar2007). Metacognitive CQ comprises four items of cultural awareness. Cognitive CQ contains six items focusing on cultural knowledge.

Building on earlier research (e.g., Verbeke, Ciravegna, Lopez, & Kundu, Reference Verbeke, Ciravegna, Lopez and Kundu2019), we measured opportunism with an adaptation of the six-item scale based on John (Reference John1984). Respondents were asked to assess statements based on their appropriateness and acceptability.

We measured customer relationship performance with the three-item scale by Panagopoulos et al. (Reference Panagopoulos, Johnson and Mothersbaugh2015). Participants were asked to recall previous or current customer experiences. By focusing on customer relationship performance rather than sales performance, we were able to capture a wider array of frontline employees’ perceptions.

Ethical relativism was measured with an adaptation to the broader business context by the relativism subcomponent of the Marketing Ethical Ideology scale (Kleiser, Sivadas, Kellaris, & Dahlstrom, Reference Kleiser, Sivadas, Kellaris and Dahlstrom2003). The four-item scale assesses the extent to which respondents believe that ethical standards are situational rather than universal.

We minimized spurious impacts by controlling for participant demographics (age and gender), industry, assignment variables (current time in assignment, assignment duration, position, and sum of expatriate experiences), and cultural distance. Prior research has shown that gender may play a role in propensity for opportunism, as women are more likely to avoid conflict and remain interconnected with others (Eagly, Reference Eagly1987). Luo (Reference Luo2007) found that opportunism may vary across industries to cope with various levels of industry structural instability. Employees’ age can affect the degree to which they practice adaptive selling (Levy & Sharma, Reference Levy and Sharma1994), which can, in turn, affect customer relationship performance. Cross-cultural experiences through either previous expatriations or time spent in the assignment can facilitate adjustment (Selmer, 2002), leading to improved performance (Caligiuri, Reference Caligiuri and Sauders1997). Due to the lack of routine and predictable nature of managerial roles resulting in more autonomy (Huang, Iun, Liu, & Gong, Reference Huang, Iun, Liu and Gong2010), the position can affect opportunistic behavior (e.g., Shimizu, Reference Shimizu2012). Additionally, controlling for the most frequently held positions (sales manager and sales director) enabled us to assess whether the customer relationship performance results were driven solely by participants currently working in sales functions. Finally, as opportunism and customer relationship performance may be influenced by cultural differences between expatriates’ home and host country, we controlled for cultural distance using the Kogut-Singh Index (1988).

Results

Measurement Model, Validity, Reliability, and Common Method Bias

We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis with LISREL 8.80 to assess the overall model fit. The measurement model confirmed the fit to the data (χ² (199) = 277.41, p < 0.05, RMSEA = 0.04, CFI = 0.99) and all hypothesized constructs reflected internal consistency (average variance extracted > 0.50) and reliability (composite reliability and Cronbach's alpha > 0.80) (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). Convergent validity was demonstrated based on the internal consistency, reliability, and high standardized factor loadings. Discriminant validity was established as each construct’s square root of the average variance extracted was greater than the correlation between all pairs of constructs (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). Common method bias was a priori reduced by careful study design in line with Podsakoff et al. (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003), and post hoc assessed using the latent method factor analysis. Results revealed that, while common method bias was present (the method factor explained 8 percent of the variance in the data), it was not dominant enough to critically impact our hypotheses testing (Williams, Cote, & Buckley, Reference Williams, Cote and Buckley1989). In conclusion, since the analysis of the measurement model confirms reliability, validity, and common method bias criteria, we commenced with the hypotheses testing. Table 3 presents factor loadings, average variance extracted, and reliabilities. Descriptive statistics appear in Table 4.

Table 4: Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations (Study 1)

Note. N = 230, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. SQRT AVEs on diagonal. Gender = (0=female, 1=Male). Duration = anticipated time in assignment: 1-8 (1 = 3-6 months … 7 = 21-24 months, 8 = 24 months and up). Tenure = tenure with the current company in years. Position = most frequently-held position (0= Others, 1 = sales manager/director). Expatriate Exp. = Sum of Expatriate Experiences, Industry = industry category (0 = services, 1 = manufacturing). Cultural dist. = Kogut-Singh Index. MC CQ = metacognitive CQ. COG CQ = cognitive CQ. CRP = Customer relationship performance. E. relativism = ethical relativism. Home countries of the expatriates (most frequent ones): 11.3% India, 7% Germany, 6.5% Australia, 5.7%, UK, 5.2% China, 4.8% France and Canada respectively, 4.3% Argentina, 3.9% Italy and Mexico respectively, 3% Japan, all others < 2%.

Hypotheses Testing

We used SPSS 22 and the PROCESS macro Model 1 with bootstrapping (Hayes, Reference Hayes2018) to run the linear and moderation analysis. While we proposed that individuals high in metacognitive CQ show higher levels of opportunism, the path analysis revealed that the relationship between the two variables is indeed negative but not significant (b = -0.10, p > 0.05), letting us reject H1a. Consistent with our theoretical argument, opportunism was higher among those individuals with higher levels of cognitive CQ (b = 0.15, p < 0.05), supporting H1b. Customer relationship performance was strengthened by both metacognitive (b = 0.39, p < 0.001) and cognitive CQ (b = 0.25, p < 0.01). Therefore, H2a and H2b were supported (see Table 5).

Table 5: Path Analysis

Note. N = 230, † p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. b = unstandardized regression coefficient; SE = standard error. Gender = (0=female, 1=male), Duration =anticipated time in assignment 1-8 (1 = 3-6 months … 7 = 21-24 months, 8 = 24 months and up). Tenure = tenure with the current company in years. position = most frequently-held position (0 = others, 1 = sales manager/director). Expatriate Exp. = sum of eExpatriate experiences. Industry = industry category (0 = services, 1 = manufacturing), Cultural Distance = Kogut-Singh Index. MC CQ = metacognitive CQ. COG CQ = cognitive CQ. CRP = customer relationship performance. E. relativism = ethical relativism.

Although ethical relativism was positively related to opportunism, the moderation tests revealed that ethical relativism only significantly strengthened the relationship between cognitive CQ and opportunism (b = 0.14, p < 0.01) but not between metacognitive CQ and opportunism (b = 0.06, p > 0.05). Therefore, H3a was rejected and H3b was supported. Furthermore, the simple slope analysis generally confirmed the positive significant relationship between cognitive CQ and opportunism. There is a significant positive relationship between cognitive CQ and opportunism when ethical relativism is high (b = 0.35, p < 0.001) or moderate (b = 0.14, p < 0.05), but not when it is low (b = 0.04, p > 0.05). The higher the individual’s ethical relativism, the stronger is the relationship between cognitive CQ and opportunism (see Figure 2). Finally, the last set of hypotheses predicted that ethical relativism attenuates the positive relationship between metacognitive and cognitive CQ and customer relationship performance. Consistent with our predictions, the relationship between metacognitive CQ and customer relationship performance (b = -0.12, p < 0.05) and cognitive CQ and customer relationship performance (b = -0.10, p < 0.05) weakened when ethical relativism was present, supporting H3c and H3d. The simple slope analysis revealed a positive significant relationship between metacognitive CQ and customer relationship performance at the low (b = 0.55, p < 0.001) and medium (b = 0.40, p < 0.001) levels of ethical relativism, but the effect was not quite significant at the high level (b = 0.22, p = 0.06). A similar pattern was visible for cognitive CQ at the low (b = 0.39, p < 0.001), medium (b = 0.26, p < 0.01), but not the high level (b = 0.12, p > 0.05) of ethical relativism. Thus, CQ has the strongest association with customer relationship performance at low levels of ethical relativism (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 2: Interaction Graph for Cognitive CQ and Ethical Relativism (Study 1)

Figure 3: Interaction Graph for Metacognitive CQ and Customer Relationship Performance (Study 1)

Figure 4: Interaction Graph for Cognitive CQ and Customer Relationship Performance (Study 1)

In summary, Study 1 confirms that cognitive CQ increases opportunism (H1b), and metacognitive and cognitive CQ increase customer relationship performance (H2a–b). Additionally, ethical relativism attenuates the relationship between metacognitive and cognitive CQ and customer relationship performance (H3c–d), but strengthens the relationship between cognitive CQ and opportunistic behavior (H3b). However, the results do not provide conclusive evidence of the dark side of metacognitive and cognitive CQ. A deeper investigation of the interplay between CQ and opportunism is therefore important, especially in markedly different settings.

Additional Hypotheses Development: Strong-Form versus Weak-Form Opportunism

Previous ethics literature has established nuances in the interpretation of ethicality across cultures as well as in opportunism itself (Luo, Reference Luo2006; Razzaque & Hwee, Reference Razzaque and Hwee2002). Luo (Reference Luo2006) distinguishes between strong-form opportunism (i.e., violating contractual norms that are explicitly codified) and weak-form opportunism (i.e., violating relational norms not specified in contracts). The distinction between these two forms of opportunism may be understood from the perspective of the opportunistic actors, their judgment of what constitutes opportunism, the situational characteristics, and their evaluation of the consequences. Strong-form opportunism may result in short-term consequences with formal remedies. Weak-form opportunism may have long-term direct consequences on relationships. These weak-form opportunism breaches are hard to trace and without formal remedies (Hawkins, Pohlen, & Prybutok, Reference Hawkins, Pohlen and Prybutok2013; Luo, Reference Luo2006).

Thus far, however, we have not considered if metacognitive and cognitive CQ have differential effects on strong-form and weak-form opportunism and whether our predictions hold outside the expatriate context in other cross-cultural settings. Informed by our broader framework of ethical relativism, we expect that our predictions extend across cultural settings because societal morality and the concepts of right and wrong are far from absolute (Bajrami & Demiri, Reference Bajrami and Demiri2019). For example, the possession of metacognitive and cognitive CQ enhances intercultural judgment and decision-making (Rockstuhl & Van Dyne, Reference Rockstuhl and Van Dyne2018). And as judgment and decision-making refer to choosing between alternative strategies while evaluating the potential consequences (Starcke & Brand, Reference Starcke and Brand2016), individuals high in metacognitive and cognitive CQ possess a heightened awareness and knowledge of the consequences of their actions. Cognitive flexibility and awareness coupled with cultural knowledge of different moral beliefs may foster self-serving, relativistic interpretations of ethical norms, and consequently create justifiable outcomes. Also, high metacognitive and cognitive CQ individuals may not judge situations to be ethically wrong, especially if the long-term outcome is perceived as beneficial for the majority of the parties involved.

In summary, we propose that individuals high in metacognitive and cognitive CQ understand the ethical norms and will avoid any perception of violating them in order not to jeopardize overall long-term success. On the other hand, to achieve this success, they may be willing to manipulate information and misrepresent contractual insights (i.e., strong-form opportunism) as the benefit of opportunism exceeds perceived costs. In line with the confluence dimension of the general theory of confluence, individuals may collude with customers for their own advantage intentionally, or hurt the firm unintentionally. While strong-form opportunism may be confined by increased contractual control, reduced contractual ambiguity, and environmental uncertainty (Lumineau & Quélin, Reference Lumineau and Quélin2012; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Liu, Yang, Maksimov and Hou2015), the cross-cultural context may inhibit such confinement and provide latitude for strong-form opportunism. Thus, we posit:

H4a: Metacognitive CQ has a positive relationship with strong-form but not weak-form opportunism.

H4b: Cognitive CQ has a positive relationship with strong-form but not weak-form opportunism.

STUDY 2: METACOGNITIVE CQ AND WEAK-FORM AND STRONG-FORM OPPORTUNISM

We conduct Study 2 for three reasons. First, we attempt to better understand the relationship between metacognitive CQ and opportunism (H1a) by examining metacognitive CQ’s impact on two opportunism forms (H4a–b). Second, we examine the role of metacognitive CQ on opportunism by means of experimental design to establish causal evidence. Finally, we expand the setting from expatriates to that of students challenged to use their cross-cultural judgment and decision-making in an international entrepreneurial setting. The development of students’ CQ, and thus future employees or entrepreneurs, has been continuously researched due to the need to possess cross-cultural capabilities when entering a global workforce (Ramsey & Lorenz, Reference Ramsey and Lorenz2016). This context also permits us to demonstrate the fluidity of our ethical relativism lens by placing respondents into a mindset that causes them to confront the reality of diverse cultural viewpoints in their home country.

Participants and Procedure

We used a priming technique to activate the mental schemas associated with metacognitive CQ and the individual’s behavior (e.g., Langer, Djikic, Pirson, Madenci, & Donohue, Reference Langer, Djikic, Pirson, Madenci and Donohue2010). We pretested both the metacognitive CQ and opportunism scenarios to ensure the success of the priming and manipulations (see Appendix A for details). Randomly assigned participants were primed for metacognitive CQ with a video about cultural differences assessment whereas the control group watched a video on supply and demand. Opportunism was similarly manipulated with randomly assigned participants asked to score a strong-form or weak-form opportunism scenario. After concluding that the manipulations were successful, we conducted the main experiment in exchange for course credit with student participants from two large universities in the US Midwest. After elimination of participants who failed quality and attention filters, straight-lined or speeded (Schoenherr, Ellram, & Tate, Reference Schoenherr, Ellram and Tate2015), as well as international students, our sample size was 118 (response rate 92.9 percent).

We randomly assigned participants to either a metacognitive CQ condition (viewing a video on cultural differences) or a control group (viewing an economics video). Following the priming, we took participants to a second study, which ostensibly examined how individuals approach negotiations (see Appendix B). We asked participants to imagine that they were small business owners opening a store where they would share space in a multicultural market. They were asked to negotiate the terms with the other owners, representing a culturally diverse set of nations (Russia, China, and Korea). Participants high in metacognitive CQ should be more aware of the effects of culture on behaviors toward outgroup members, making them less trusting of their counterparts and more likely to form opportunistic intentions (Cavusgil et al., Reference Cavusgil, Deligonul and Zhang2004). We also randomly assigned participants to receive either a strong-form (i.e., breaking a contractual agreement) or weak-form (i.e., violating a relational norm) scenario. After reading the scenario, participants indicated their likelihood to keep pertinent information a secret all the way through the negotiation on a 1 (extremely unlikely) to 7 (extremely likely) scale.

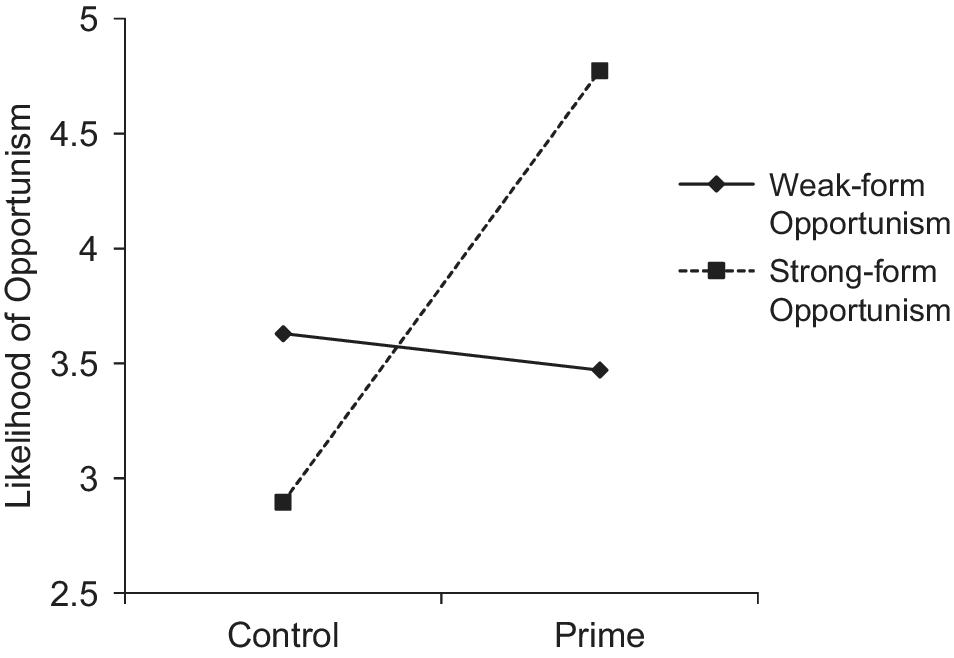

Results and Discussion

Our procedures resulted in a 2 (metacognitive CQ primed vs control) x 2 (weak-form vs strong-form) design. We conducted a two-way ANOVA with dummy variables for cross-cultural awareness prime (1 = cultural video; 0 = supply and demand video) and opportunism type (1 = strong-form; 0 = weak-form) as the factors, controlling for age, gender, and the participant’s ethical relativism (α = 0.78). The interaction between the metacognitive CQ and the form of opportunism was significant (F(1, 111) = 7.61, p < 0.01).Footnote 1 Examination of the marginal means indicated that those primed for metacognitive CQ were more likely to act opportunistically in the strong-form scenario (M Prime = 4.13, M Control = 3.46), whereas the primed group was less likely to act opportunistically in the weak-form scenario (M Prime = 3.43, M Control = 4.60) (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Interaction Graph for Metacognitive CQ and Opportunism Form (Study 2)

In summary, metacognitive CQ impacts opportunism differentially, depending on whether a contractual or a relational norm is violated. The opposing effects of metacognitive CQ on strong-form and weak-form opportunism found in Study 2 sheds light on the nuanced relationship between metacognitive CQ and opportunism, and offers alternative and causal support for our hypothesized model (i.e., H1a and H4a). Finally, it also provides context for the broader theme of diverse cultural viewpoints that engender individual ethical relativism.

STUDY 3: COGNITIVE CQ AND WEAK-FORM AND STRONG-FORM OPPORTUNISM

Study 3 replicates Study 2’s experimental priming technique, albeit for cognitive CQ. In line with Study 2, we attempt to provide causal evidence for the Study 1 finding that cognitive CQ increases opportunistic behavior (H1b). Second, we investigate if cognitive CQ is positively related to strong-form but not weak-form opportunism (H4b). Third, in extension to Study 2, we add an anagram task (e.g., Lu et al., Reference Lu, Quoidbach, Gino, Chakroff, Maddux and Galinsky2017) to account for actual rather than self-reported opportunistic behavior. Specifically, we instruct participants to solve four anagrams in two minutes and self-report the number they solved. As only two anagrams are solvable, those who claim to have solved more than two were coded as behaving opportunistically (strong-form).

Participants and Procedure

As we relied on the same opportunism scenario as in Study 2, we focused our pre-test on the cognitive CQ scenario. After confirming the success of the cognitive CQ priming (see Appendix C), we tested our main experiment in exchange for course credit with student participants from two large universities in the US South and Midwest. Student participants were selected to allow for equivalency and comparability between Studies 2 and 3. After elimination of participants who failed quality and attention filters, straight-lined or speeded, as well as international students our sample size was 106 (response rate 84.1 percent).

Results and Discussion

In line with Study 2, the process resulted in a 2 (Cognitive CQ primed vs control) x 2 (weak-form vs strong-form) design. We conducted a two-way ANOVA, controlling for age, gender, and the participant’s ethical relativism (α = 0.77). The interaction between the cognitive CQ prime and the form of opportunism was significant (F(1, 99) = 6.83, p < 0.01).Footnote 2 Examination of the marginal means indicated that those primed for cognitive CQ were more likely to act opportunistically in the strong-form scenario (M Prime = 4.77, M Control = 2.90), whereas there was no significant difference between the likelihood to act opportunistically in the weak-form scenario (M Prime = 3.47, M Control = 3.63) (see Figure 6). Finally, the anagram test confirmed the robustness of the results. Participants primed for cognitive CQ were more likely to overstate the number of anagrams solved (M Prime = 27 percent overstated, M Control = 11 percent overstated; p < 0.05), and thus were more likely to behave opportunistically (i.e., strong-form).

Figure 6: Interaction Graph for Cognitive CQ and Opportunism Form (Study 3)

In summary, we provide causal support that the possession of cognitive CQ may trigger opportunistic behavior, specifically in its strong-form (H1b and H4b). Different from Study 2, where we found opposite effects of primed metacognitive CQ on strong-form and weak-form opportunism, in Study 3, cognitive CQ only affected strong-form opportunism significantly. Study 3 also provides support for the broader view that individual ethical decision making is not static and can be impacted by the situational context and CQ level.

STUDY 4: A TEST OF THEORY AND UNDERLYING MECHANISM

Having established the general effect of the two CQ components on customer relationship performance on opportunism and the moderating effect of ethical relativism (Study 1), as well as the differential effect of metacognitive and cognitive CQ on strong-form and weak-form opportunism (Study 2 & 3), the next step is to corroborate evidence and understand how the impact of the two mental CQ components on opportunism can coexist with the positive effect on customer relationship performance. Additionally, as Study 1 was conducted with expatriates and Studies 2 and 3 with students, we seek to employ a different sample to further enhance external validity and generalizability of the results. Thus, we conduct Study 4 using an experimental reflection and allocation design with working adults in the United States. Mental CQ may not only develop and be required in the international contexts but also proves helpful for cross-cultural interactions in the domestic environment (Lorenz, Ramsey, Morrell, & Tariq, Reference Lorenz, Ramsey, Morrell and Tariq2017).

As the general theory of confluence suggests that confluence may lead to misallocation and adverse effects for third-party stakeholders (Zardkoohi et al., Reference Zardkoohi, Harrison and Josefy2017), we introduce an allocation scenario to establish the priority of expatriates’ interests (oneself, firm, and customer). An allocation priority toward oneself and the customer would offer additional causal evidence for the results established in Study 1 (H1a–b; H2a–b) and provides another test of our theoretical framework.

Furthermore, to understand the underlying drivers of participants’ allocation behavior, we ask participants questions regarding the likelihood that ethical concerns and the belief that “ends justify the means” played a role in their decision. First, while an expected outcome may drive behavior in decision-making, the moral intensity (whether an individual identifies an ethical situation and how important the ethical issue is perceived [Jones, Reference Jones1991]) may determine the degree of violation the opportunistic actors may commit. Individuals high in mental CQ may focus more on the long-term consequences than on the actual decision-making process, thus excluding ethical considerations from their decision-making. Or, as opportunism is subjective, individuals high in mental CQ may not consider certain behaviors as ethically wrong. Second, the focus on long-term outcomes may lead to an “ends justifies the means” argument. Individuals high in mental CQ may accept short-term infractions in order to achieve potential long-term success for most involved parties, or just the ones they consider important. In either case an underlying foundation of ethical relativism, which suggests latitude in an individual’s justification of ethical decision-making, cannot be separated from its very real impact on potential outcomes.

Participants and Procedure

We pretested the mental CQ (both metacognitive and cognitive CQ) prime to ensure the success of the priming and manipulations (see Appendix D for details). Randomly assigned participants were primed for mental CQ with a short video about cross-cultural differences and awareness, whereas the control group watched a video on supermarket psychology. Following the video, participants reflected for three minutes on either an encounter with a customer from a different culture or a general encounter at the supermarket. After concluding that the manipulation was successful, we conducted the main experiment with participants from an online panel in exchange for a monetary award. Participants had to live in the United States, be full-time employed, work in marketing or sales, and have frequent customer contact in their current jobs. After elimination of participants who failed screening, quality, and attention filters, our sample size was 104 (response rate of 92 percent).

We randomly assigned participants to either the mental CQ condition or the control group. Following the priming, we took participants to a second study that examined how individuals approach decisions while expatriated by their company to a foreign country. After explaining the general circumstances of expatriation, we asked participants to imagine that they were an expatriate sent by their company (as their top salesperson) to work and live in China for two years. Their specific task was to expand the company’s business and to build a strong customer base in China. Participants were told that in their position as an expatriate they were currently negotiating a deal with a new customer, and that they must decide how much of the created value each stakeholder should receive (oneself, the company, and the customer). The total sum for distribution was set to $1,000 and could be allocated in any way between the three parties, with the condition that the full amount had to be utilized. The allocation decisions should reflect whether the mental CQ prime would temporarily change participants’ priorities and confluence with respective stakeholders. After the scenario, we asked participants to indicate on a 7-point Likert scale to what degree (1) ethical concerns (Wade-Benzoni, Sondak, & Galinsky, Reference Wade-Benzoni, Sondak and Galinsky2010) and (2) their belief that good outcomes excuse any wrongs committed to attain them played a role in their allocation decision. We concluded the experiment with questions about demographics, international experiences, and specifically prior visits to Asia, including China.

Results and Discussion

The allocation scenario suggests that those primed for mental CQ were more likely than the control group to allocate value created through business dealings to themselves (M Prime = 347.25, M Control = 288.45, p < 0.05).Footnote 3 The control group, on the other hand, was more likely to allocate value created to the firm (M Prime = 327.14, M Control = 407.66, p < 0.01). While the prime group was more likely to allocate value to the customer than the control group, the difference was not significant (M Prime = 327.59, M Control = 303.89, p > 0.05). The allocations suggest the following rank order of priorities when primed for mental CQ: oneself, customer, and then the firm (vs. control: firm, customer, and then oneself). These findings provide an initial test of our general theory of confluence framework. Specifically, the possession of higher levels of mental CQ may influence misallocation of resources and opportunistic behavior benefitting oneself by harming the firm, though not negatively affecting the customer. Second, the test of ethical concerns and an “ends justify the means” rationale provides a more nuanced picture underlying the allocation decision. After controlling for age, gender, international experience, and previous exposure to Asia, the mental CQ prime group was somewhat less likely to take ethical concerns into consideration when allocating the value created (F(1,98) = 2.98, p < 0.10; M Prime = 4.85, M Control = 5.41). However, the mental CQ prime group was more likely to act in a way congruent with an “ends justify the means” argument in their allocation decision (F(1,98) = 6.89, p < 0.05; M Prime = 3.73, M Control = 2.73).

In conclusion, Study 4 corroborates evidence that expatriates high in mental CQ can both behave opportunistically and satisfy their customers (H1a–b; H2a–b). We also establish that high mental CQ may reduce ethical concerns in decision-making and increase the belief that a good outcome excuses any wrongs committed to attain it. Such a relativistic mindset should be of potential concern to firms with global interests and employees working abroad on their behalf.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The present study draws on the general theory of confluence as well as the international business and ethics literatures to investigate whether CQ holds both a dark and a bright side. Across four studies and multiple settings, we generally establish that metacognitive and cognitive CQ lead to superior customer relationship performance while concurrently increasing opportunistic behavior. Study 1 results suggest that metacognitive and cognitive CQ increase customer relationship performance and cognitive CQ increases opportunism. Study 1 also reveals that ethical relativism attenuates the relationship between metacognitive and cognitive CQ and customer relationship performance but strengthens the relationship between cognitive CQ and opportunistic behavior. While Study 1 explores the association using a survey of expatriates, Study 2 and Study 3 investigate, in more detail, the nuanced relationships between the two mental CQ components and strong- and weak-form opportunism, using an experimental design. Both studies suggest that metacognitive and cognitive CQ significantly affect strong-form opportunism, with no or opposing effects on weak-form opportunism. Study 4 corroborates evidence from Studies 1 to 3 and also provides a test of the general theory of confluence by establishing that individuals high in mental CQ have a higher tendency to behave in their own interest. They also may collude with customers for their own and the customers’ benefit, at least in the short-term harming the firm. Finally, ethical concerns may be less likely to play a role for those high in mental CQ, however the ends justify the means argument seems more prominent. Influenced by a new culture, the context of their employment, the perceived outcomes of their actions, and, more broadly, their own mental CQ, individuals may find themselves inclined toward ethical relativism.

Theoretical Implications

This study is among the first to investigate the relationship between two increasingly important constructs: cross-cultural capabilities and dark side behavior (opportunism and ethical relativism). Previous research has almost entirely focused on the bright side of possessing high levels of metacognitive and cognitive CQ with only recent research advocating for a more balanced treatment (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Schei and Selart2018; Rockstuhl & Van Dyne, Reference Rockstuhl and Van Dyne2018). By unveiling a potential dark side of the two mental CQ components while at the same time emphasizing the coexistence of a bright side, we present a more nuanced view of the implications of possessing CQ.

First, we establish metacognitive and cognitive CQ as important antecedents to opportunistic behavior as well as ethical relativism. Thus, we extend Lu et al.’s (Reference Lu, Quoidbach, Gino, Chakroff, Maddux and Galinsky2017) finding of the negative impact of international experiences on immoral behavior into the realm of cross-cultural capabilities. While this finding seems novel, extant literature has suggested that in some situations, individuals with higher CQ may “try to benefit themselves, thus, likely reducing the total benefit to the group” (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Schei and Selart2018: 166). Related evidence from the cross-cultural adaptation literature has shown similar results of “too much of a good thing” (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Schei and Selart2018: 166) with higher levels of an apparently good capability also having negative effects (Francis, Reference Francis1991). By replicating these findings in markedly different cross-cultural settings, from the expatriate, to the student and an average American employee, we also extend the generalizability of the findings and the pervasiveness of the potentially problematic impact of CQ across various subsections of the population.

Second, Zardkoohi et al. (Reference Zardkoohi, Harrison and Josefy2017: 417) challenged agency theory by introducing the general theory of confluence as “a more complete conceptualization” that considers “how the corporate context may induce opportunistic behavior by and against multiple parties.” Our paper is the first to test the novel theoretical framework while also adding to its boundary conditions. We extend the general theory of confluence to the expatriation and cross-cultural context where information is more asymmetric and the chances for opportunistic behavior are high. We suggest that instead of the expatriate colluding with the company at the expense of a third party, there may be a confluence between the expatriate and the customer. In support, we find that CQ leads to both opportunism and customer relationship performance.

Third, by demonstrating that mental CQ can lead to positive and negative outcomes, we present an intriguing but not unprecedented ethical paradox. Much like Forsyth (Reference Forsyth1980) who put forth a classification of ethical ideologies suggesting that individuals can be high or low on both idealism and relativism, we demonstrate that those who score high on both outcomes likely judge opportunism as subjective (Arikan, Reference Arikan2018). While our results reveal opportunistic behavior is targeted toward the firm, the customers do not seem to suffer from it. Conversely, the customers received a slightly higher allocation than they did from the control group. Individuals may rationalize their self-serving behavior as not hurting the customer or their employer (considering the similar distribution in the allocation decisions between the three stakeholders when primed for mental CQ). We also establish that high mental CQ individuals are more likely to justify their means based on the outcomes attained. By lending empirical support to this argument, we add CQ as a potential relevant factor shaping individuals’ opportunism judgments (Arikan, Reference Arikan2018).

Finally, we demonstrate how individuals’ mental CQ can interact with their ethical perspective resulting in different ethical behavior decisions. Our results reveal that high mental CQ individuals are less likely to consider ethics in their value allocation decisions. While mental CQ can help satisfy the wants and needs of diverse customers, ethical relativism reduces the positive relationship between mental CQ and customer relationship performance. Thus, we extend research on the individual’s ethical perspective to the expatriate context, and highlight the importance of ethical perspectives when examining cross-cultural situations (e.g., Valentine & Bateman, Reference Valentine and Bateman2011).

Managerial Implications

This research has implications for practitioners and the HR selection process. First, managers should note that individuals working in boundary spanning roles in a cross-cultural environment are exposed to increased opportunities for unethical behavior. Individuals with higher levels of mental CQ are more likely to take advantage of these opportunities. The natural reaction to these findings is to question whether firms should increase corporate governance (centralized policies) or hire less culturally astute individuals for expatriate assignments, challenging conventional wisdom. However, our findings also show that ethical relativism positively moderates this relationship. Therefore, managers may be able to reduce opportunistic behavior by implementing tactics to influence individuals’ ethical perspectives to be less relativistic (Wang & Calvano, Reference Wang and Calvano2015), training moral competence (Gentile, Reference Gentile2016), and evaluating their ethical perspective when making assignment decisions. Considering ethical relativism scores as part of the assignment process may reduce unethical behavior in the presence of asymmetric information between the employee and organization.

Additionally, we demonstrate that mental CQ can improve customer relationship performance in a cross-cultural context. Managers may be able to improve employee cross-cultural performance through the use of training to increase awareness and knowledge (Ramsey & Lorenz, Reference Ramsey and Lorenz2016), or proactively impact universalistic, as opposed to relativistic (Demuijnck, Reference Demuijnck2015), views when deployed on expatriate assignments. In particular, metacognitive CQ has a stronger effect on customer relationship performance than cognitive CQ, which supports prior arguments that cultural awareness is perhaps the most essential of the CQ components because it links cognition with behavior (Magnusson et al., Reference Magnusson, Westjohn, Semenov, Randrianasolo and Zdravkovic2013). Further, our results indicate that ethical relativism can negatively moderate the relationship between those cross-cultural capabilities and customer relationship performance. Therefore, managers may be able to maximize the benefits of cross-cultural training if it is coupled with ethical training to minimize the influence of an individual’s ethical relativism. This will enable firms to optimally benefit from the employee’s cross-cultural skills. In summary, managers can maximize the benefits and minimize the negative consequences of an employee’s mental CQ by assessing their ethical perspective during the recruitment and the selection phase for an international assignment.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

Our study’s limitations also provide fertile ground for future research. First, our research focuses on self-reported customer relationship performance. Future work might consider employing secondary customer and supervisor ratings. Such an approach would provide insight into how ethical relativism might bias the employee’s self-perception of performance. Future empirical efforts may also examine cross-cultural motivation and adaptive behaviors so that managers understand how an assignment abroad may yield a negative consequence, such as opportunism. Second, future research may distinguish between different types of customer relationships. Some scholars have argued that social exchange theory may provide additional insights into opportunistic behavior for long-term buyer-seller relationships (e.g., Luo et al., Reference Luo, Liu, Yang, Maksimov and Hou2015). Therefore, future research should examine whether the customer relationship type has an impact on the relationship between CQ and opportunistic behavior. Third, future research may also examine additional negative behavioral outcomes of CQ as well as the specific tactics employed by culturally intelligent individuals. For example, Kilduff, Chiaburu, and Menges (Reference Kilduff, Chiaburu and Menges2010) suggest that emotional intelligence can lead to four dark-side tactics in organizational settings. This type of fine-grained examination may be conducted with CQ and opportunistic behavior in different organizational contexts. As discussed above, employees may act opportunistically against the firm, customer, and coworkers. Identifying the opportunism tactics toward these three entities will allow researchers to provide practitioners with more effective solutions for avoiding CQ’s dark side. Finally, future research might also consider how varying compensation systems, or even promotional pathways linked to enhanced firm performance in international settings, might alter individuals’ perceptions of their most desirable personal outcomes in expatriate settings.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/beq.2020.2.

Acknowledgements

We thank the handling editor, Kelly Martin, and the two anonymous reviewers for their developmental feedback and guidance throughout the review process. We also would like to acknowledge the research support from Clark Johnson. The research received funding from Florida Atlantic University, Saint Louis University, and the University of Alabama.

APPENDIX A Pretest of Stimuli (Metacognitive CQ)

We pretested the experimental study using an online panel. We recruited participants residing in the United States, eliminated respondents with nationalities other than “US American,” as well as those who did not match the student age sample characteristic for our main experiment of Study 2. This resulted in a sample size of twenty-six.

In the first pretest, we randomly assigned participants to view a video either about assessing cross-cultural differences in product design (experimental group) or about supply and demand (control group). The priming video discussed the need for marketers to be aware of cross-cultural differences when designing products, which was of importance for the student sample in our main experiment. After viewing the video, participants completed the measure for metacognitive CQ (α = 0.68), and cognitive CQ (α = 0.85), and the twenty-item Generalized Ethnocentrism scales (Neuliep & McCroskey, Reference Neuliep and McCroskey1997 α = 0.83)—ethnocentrism may be a further alternative explanation. Participants in the cultural prime group (vs. control group) indicated an increase in metacognitive CQ (M Prime = 4.89, M Control = 4.10; F(1, 24) = 4.24, p = 0.05). In line with our predictions, the prime had no effect on cognitive CQ (M Prime = 3.97, M Control = 3.76; F(1, 24) = 0.17, p > 0.05) or ethnocentrism (M Prime = 2.57, M Control = 2.84; F(1, 24) = 1.67, p > 0.05). We conclude that the CQ metacognitive priming was successful.

Similarly, in the second pretest, we tested the opportunism scenario. We randomly assigned twenty-six participants, who were selected using the same criteria as in the first pretest, to read either a strong-form or weak-form negotiation scenario. After reading the scenario and subsequently the definitions of strong-form and weak-form, we asked them to rate the scenario on a 0 (weak-form) to 100 (strong-form) scale. Participants rated the strong-form scenario as significantly more strong-form than the weak-form scenario (M Strong = 72.13, M Weak = 40.00; F(1, 24) = 14.89, p < 0.01). We conclude that the opportunism type manipulation was successful.

APPENDIX B Introduction to the Negotiation Experiment