In one of the most famous sentences in the history of economic thought, [Adam Smith] wrote, “it is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their self-interest.” Smith neglected to mention that none of these tradesmen actually puts dinner on the table; ignoring cooks, maids, wives, and mothers in one fell swoop (Folbre, Reference Folbre2009: 59).

From The Coca-Cola Company to Goldman Sachs to Walmart, corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives intended to bolster women’s entrepreneurship have proliferated in firms across the globe in recent years. At least half of the 50 largest companies in the United States Footnote 1 and 40 of the largest in the world Footnote 2 support programs of this nature, and these numbers are rapidly increasing. Corporate support for women’s entrepreneurship thus represents one of the most explicit manifestations of CSR engagement with gender to date.

Scholarship on gender and CSR is at an early stage. However, as this special section attests, this landscape is changing (Coleman, Reference Coleman2010; Grosser, Reference Grosser2009; Grosser, Reference Grosser2016; Karam & Jamali, Reference Karam and Jamali2015; Kilgour, Reference Kilgour2007; Kilgour, Reference Kilgour2012; Miller, Arutyunova, & Clark, Reference Miller, Arutyunova and Clark2013; Prugl, Reference Prugl2015; Thompson, Reference Thompson2008). Moreover, as I later detail, feminist scholarship has made limited—but important—contributions to mainstream CSR scholarship across several decades. These include insights regarding stakeholder theory (Buchholz & Rosenthal, Reference Buchholz and Rosenthal2005), corporate governance and citizenship (Grosser, Reference Grosser2009; Machold, Ahmed, & Farquhar, Reference Machold, Ahmed and Farquhar2008), and business ethics (Borgerson, Reference Borgerson2007). However, following a review of CSR-related research in six major publication venues for scholarship on CSR, I contend that insights from feminist economics concerning the nature of “work” in particular have not been sufficiently applied to CSR to date. Because feminist economics attends to the gendered nature of economic arrangements and the ethical implication of these, it represents a fundamentally interesting body of literature for those working in and studying gender and CSR.

In order to demonstrate one way in which insights from feminist economics are relevant to research on CSR, this article proceeds as follows: first, I outline the puzzle or motivation for this research in scholarship and practice. I establish that a growing cadre of corporations runs programs supporting women entrepreneurs and that these programs represent a major aspect of current CSR engagement with gender. Second, I provide a brief review of research on gender and entrepreneurship. Third, with the problematic around women’s entrepreneurship and CSR established, I provide a brief review of feminist engagement with the CSR literature. Fourth, I introduce the field of feminist economics, emphasizing just one aspect of this extensive body of scholarship: the historically freighted and gendered definition of “work,” a topic I argue to be of relevance to CSR scholars. Fifth, in order to demonstrate how these concepts might be employed, I use perspectives from feminist economics on work to examine literature on entrepreneurship. The aim of this exercise is to explore the extent to which certain gendered, unexamined assumptions about the nature of work may affect how entrepreneurship is placed to facilitate the integration of business and social demands, a core aim of CSR. Finally, I present a conceptual framework for this phenomenon, which can inform work by future researchers.

WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT THROUGH ENTREPRENEURSHIP: A CSR STRATEGY GAINING GROUND

Corporate support for women’s entrepreneurship spans a remarkable range of industries and takes multiple forms. One of the world’s largest investment banks, Goldman Sachs, supports 10,000 Women, an initiative that aims to “[foster] economic growth by providing [ten thousand] women entrepreneurs around the world with a business and management education, mentoring and networking, and access to capital.” Footnote 3 Launched in 2008, this program has been active in 43 countries and, from 2014, partnered with the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation to raise capital to support “100,000 underserved women entrepreneurs globally.” Footnote 4 The world’s largest beverage company, Coca-Cola, leads 5by20, which seeks to “enable the economic empowerment of 5 million women entrepreneurs across the company’s value chain by 2020.” Footnote 5 Launched in 2010, 5by20 has worked with women entrepreneurs in 40 countries from the corporate position statement that “women are a powerful global economic force, but they are consistently undervalued.” Footnote 6 The year 2011 saw the launch of the ongoing Global Women’s Economic Empowerment Initiative by Walmart, the world’s largest retailer. The stated aim of Walmart’s set of programs is to “empower women worldwide” by providing “hard-working women [entrepreneurs] . . . opportunities to improve their own lives and . . . the lives of their families and communities.” Footnote 7

These initiatives are significant in scope and potential impact. Each was launched by its firm’s chief executive officer and has received important attention from policymakers and media. These three programs are but a handful of examples of multitudinous Footnote 8 recent corporate initiatives launched in a similar spirit. Analysis of these programs offers fertile ground for scholars of CSR and gender.

A complete analysis of the factors contributing to the rise of corporate interest in women’s enterprise falls outside the scope of this article, but can be presented as stylized facts containing at least three key contributing influences. First, since at least the early 2000s, entrepreneurship in general has received increasing—though not uncontested—attention as a means of pursuing market-based approaches to development and social impact (Blowfield & Dolan, Reference Blowfield and Dolan2014; Bruton, Reference Bruton2010; Bruton, Ahlstrom, & Obloj, Reference Bruton, Ahlstrom and Obloj2008; Calas, Smircich, & Bourne, Reference Calas, Smircich and Bourne2009; Scott, Dolan, Johnstone-Louis, Sugden, & Wu, Reference Scott, Dolan, Johnstone-Louis, Sugden and Wu2012; Webb, Kistruck, Ireland, & Ketchen, Reference Webb, Kistruck, Ireland and Ketchen2010).

Second, the highly publicized experiences of microfinance, which famously—if not always intentionally—emphasized provision of financial instruments to women, combined with enthusiasm across the mid-2000s for “conditional cash transfers” to female heads of household to attract interest from policy organizations including the World Bank, the United Nations, and national governments. Research by these bodies began to suggest that women possess the ability to catalyze a “multiplier effect,” i.e., that increases in women’s income appear to have multiple positive secondary effects on children and communities (Elborgh-Woytek, Reference Elborgh-Woytek2013; Mason & King, Reference Mason and King2001; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2010; United Nations Development Program, 2006b; World Bank Group, 2014). The World Bank famously supported a case for gender equality as “smart economics” (World Bank Group, 2006) and continues to propose links between women’s empowerment and “shared prosperity” (World Bank Group, 2014). The outcome of these first two phenomena has been the creation of a politically influential case for gender empowerment in the economic sphere.

Third, in the wake of slow or stagnant economic growth since 2008, corporations and policymakers have been in search of alternative strategies through which to recover economic dynamism. In the quest for elusive growth, numerous elite think tanks as well as financial services and consulting firms published reports setting out a “business case” for empowering women, often presenting women entrepreneurs as a source of untapped or inadequately tapped financial returns (Buvinic, Furst- Nichols, & Pryor, Reference Buvinic, Furst-Nichols and Pryor2013; Coleman, Reference Coleman2010; Economist Intelligence Unit, 2012; Koch, Lawson, & Matsui, Reference Koch, Lawson and Matsui2014; McKinsey & Company, 2010; Nikolic & Taliento, Reference Nikolic and Taliento2010; Silverstein & Sayre, Reference Silverstein and Sayre2009; World Economic Forum, 2014). In industries ranging from banking to consumer goods, women are increasingly cast as an untapped source of customers, suppliers, and innovators. Female participation in the formal labor force is up across some industries and regions, yet women remain disproportionately likely to be unemployed, underemployed, or informally employed relative to men across the globe (Elborgh-Woytek, Reference Elborgh-Woytek2013). Thus, due in no small part to their historical exclusion from formal markets and concurrent relative specialization in unpaid/care work (Kabeer, Reference Kabeer2016), women appear to represent a means through which business and social goals may be simultaneously pursued, making women’s enterprise attractive for CSR activity.

Practices of CSR should be examined as part of a wider system of governance and institutions including civil society, multilateral organizations, and national governments (Moon & Vogel, Reference Moon, Vogel, Crane, McWilliams, Matten, Moon and Siegel2008). Indeed, a host of additional demographic, social, political, and economic variables contributed to—and continue to affect—the rise in corporate interest in women’s entrepreneurship. And of course, the strategic embrace of gender equality—i.e., as a means to a “knock on” social or business benefit—is not without its critics (Arutyunova & Clark, Reference Arutyunova and Clark2013; Grosser & van der Gaag, Reference Grosser, van der Gaag, Wallace, Porter and Ralph-Bowman2013; Prugl, Reference Prugl2015). However, for the purposes of this article it is sufficient to establish that support for women’s entrepreneurship represents a prevalent, highly influential avenue of direct business engagement with gender. Analysis of this CSR phenomenon opens important possibilities for theoretical consideration of the interface between gender and business. Because CSR activities have significant potential consequences for political and institutional arrangements (Hahn, Reference Hahn2012; Hahn, Figge, Pinkse, & Preuss, Reference Hahn, Figge, Pinkse and Preuss2010; Scherer & Palazzo, Reference Scherer and Palazzo2007), there is a need to be theoretically attentive to the ways in which these activities may reinforce or challenge extant areas of inequality, particularly as CSR establishes closer engagement with variegated aspects of gender in society (Cudd, Reference Cudd2015; Karam & Jamali, Reference Karam and Jamali2013; Prugl Reference Prugl2015).

SCHOLARSHIP ON GENDER AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Before proceeding into discussions of scholarship, some clarification of terms is in order. First, both CSR and entrepreneurship accommodate a broad set of related literatures. In this article, I use the terms “CSR literature” and “CSR scholarship” to refer to articles about CSR available in leading publication venues for CSR-related topics. Footnote 9 Similarly, references to “entrepreneurship scholarship” and the “entrepreneurship literature” speak to work within the top academic journals of that field. Footnote 10 The word “empowerment” is used in this article without adherence to any single definition of the term. Footnote 11

In business and management literature, the study of women entrepreneurs is known to bring certain tensions to light. For example, scholarship traditionally demonstrates that women’s enterprises tend to perform—in general terms—less strongly relative to those owned by men in terms of growth rates, access to formal finance, hiring of employees, and other standard measures of entrepreneurial success (Boden & Nucci, Reference Boden and Nucci2000; Brush, DeBruin, & Welter, Reference Brush, De Bruin and Welter2009; Coleman, Reference Coleman2000; Coleman & Robb, Reference Coleman and Robb2009; Eddleston, Ladge, Mitteness, & Balachandra, Reference Eddleston, Ladge, Mitteness and Balachandra2016). Globally, research has tended to suggest that overall, women’s entrepreneurial ventures are conspicuously smaller, start with less capital, and are relatively less likely than men’s to access high-value sectors (Brush, Carter, Gatewood, Greene, & Hart, Reference Brush, Carter, Gatewood, Greene and Hart2004; Coleman & Robb, Reference Coleman and Robb2009; Fairlie & Robb, Reference Fairlie and Robb2009; Gatewood, Carter, Brush, Greene, & Hart, Reference Gatewood, Carter, Brush, Greene and Hart2003; Hisrich & Brush, Reference Hisrich and Brush1984; Kelley, Brush, Greene, Herrington, Ali, & Kew, Reference Kelley, Brush, Greene, Herrington, Ali and Kew2015; Morris, Miyasaki, Watters, & Coombes, Reference Morris, Miyasaki, Watters and Coombes2006). This apparent gap between the performance of men’s and women’s businesses, between the promise and potential of female enterprise and its reality, remains a source of perplexity for scholars and practitioners.

Researchers have explored many reasons for gendered differences in entrepreneurial performance. Suggested—and often hotly debated—hypotheses include the existence of limitations on women’s self-confidence (Amatucci & Crawley, Reference Amatucci and Crawley2011; Kirkwood, Reference Kirkwood2009; Roper & Scott, Reference Roper and Scott2009; Venugopal, Reference Venugopal2016; Wilson, Kickul, & Marlino, Reference Wilson, Kickul and Marlino2007), entrepreneurial motivation (Crant, Reference Crant1996; Duberly & Carrigan, Reference Duberley and Carrigan2012; Fairlie & Robb, Reference Fairlie and Robb2009; Saridakis, Marlow, & Storey, Reference Saridakis, Marlow and Storey2014), “appetite” for risk Footnote 12 or personal interest in profit (Brindley, Reference Brindley2005; DeMartino, Barbato, & Jacques, Reference Demartino, Barbato and Jacques2006; Humbert & Brindley, Reference Humbert and Brindley2015; Maxfield, Shapiro, Gupta, & Hass, Reference Maxfield, Shapiro, Gupta and Hass2010), access to credit or industry knowledge (Coleman, Reference Coleman2000, Coleman & Robb, Reference Coleman and Robb2009; Demirguc-Kunt, Klapper, Singer, & van Oudheusden, Reference Demirguc-Kunt, Klapper, Singer and Van Oudheusden2014; Manolova, Carter, Manev, & Gyoshev, Reference Manolova, Carter, Manev and Gyoshev2007; McGrath Cohoon, Wadhwa, & Mitchell, Reference McGrath Cohoon, Wadhwa and Mitchell2010; Wu & Chua, Reference Wu and Chua2012), or to networks (Aldrich, Ray Reese, & Dubini, Reference Aldrich, Ray Reese and Dubini1989; Diaz Garcia & Carter, Reference Diaz Garcia and Carter2009; Foss, Reference Foss2010; Jayawarna, Jones, & Marlow, Reference Jayawarna, Jones and Marlow2015; Lerner, Brush, & Hisrich, Reference Lerner, Brush and Hisrich1997). Each of these areas has resulted in the production of research streams, many of which are actively pursued. However, other scholars of women’s entrepreneurship have eschewed perspectives privileging the suggestion that women themselves “underperform” as entrepreneurs, seeking instead to identify how the theory and institutions of entrepreneurship might be gendered in ways that meaningfully disadvantage women (Ahl, Reference Ahl2006; Baughn, Chua, & Neupert, Reference Baughn, Chua and Neupert2006; Calas et al., Reference Calas, Smircich and Bourne2009; Fischer, Reuber, & Dyke, Reference Fischer, Reuber and Dyke1993; Gupta, Goktan, & Gunay, Reference Gupta, Goktan and Gunay2014; Klyver, Nielsen, & Evald, Reference Klyver, Nielsen and Evald2013; McGowan, Redeker, Cooper, & Greenan, Reference McGowan, Redeker, Cooper and Greenan2012).

For example, in a now highly cited piece in entrepreneurship’s leading journal, Bird and Brush (2002: 41) argued for a “gendered perspective on organizational creation,” drawing attention to ways in which women’s entrepreneurial experiences might be inadequately captured by scholarship. In 2006, the same journal featured a call for a community of scholars dedicated to systematic theory building on women’s enterprise, characterized by research acknowledging the “heterogeneity of what constitutes women’s entrepreneurship” (de Bruin, Brush, & Welter, Reference de Bruin, Brush and Welter2006: 590). Brush et al. (Reference Brush, De Bruin and Welter2009) have gone on to reiterate the need for critical reflection on established theories of entrepreneurship, calling for the use of gender as a means through which to make manifest and interrogate de facto assumptions of the field. Work by multiple authors (Ahl & Nelson, Reference Ahl and Nelson2015; Hughes, Jennings, Brush, Carter, & Welter, Reference Hughes, Jennings, Brush, Carter and Welter2012; Welter, Reference Welter2011; Zahra, Reference Zahra2007) has stressed the importance of the examination of context, including family and informal institutions, in explorations of entrepreneurial outcomes. For example, Vincent (2016: 1180) uses a Bourdieuian framework to demonstrate that the accumulation of crucial forms of capital contains a temporal aspect, i.e., that “[gendered] participation in the domestic field can affect self-employed careers negatively.” Similarly, Jennings and McDougald (2007: 747) argue for examination of potential gendered strategies for managing the “work-family interface” when exploring the growth of entrepreneurial firms. Henry, Foss, Fayolle, Walker, and Duffy (2015: 584) caution that a failure to account for the “contextually embedded” nature of women’s diverse experiences with entrepreneurship may perpetuate a “traditional . . . dated and inaccurate” view of women’s alleged entrepreneurial underperformance.

Finally, Calas et al. (Reference Calas, Smircich and Bourne2009) advocate that scholars approach entrepreneurship not as primarily an economic activity with potential social impact, but rather as a “social change activity” open to a variety of possible positive, neutral, and negative outcomes. Various authors (Ahl, Berglund, Pettersson, & Tillmar, Reference Ahl, Berglund, Pettersson and Tillmar2016; Al-Dajani, Carter, Shaw, & Marlow, Reference Al-Dajani, Carter, Shaw and Marlow2015; Haugh & Talwar, Reference Haugh and Talwar2016) have initiated research compatible with this perspective, including Lewis (2014: 4) who articulates an “urgent need to direct critical attention away from a dominant focus on masculinity and the exclusion of women from . . . entrepreneurship,” instead advocating for examination of how “plural femininities” become “included in the organizational sphere.” In this work, Lewis advocates a need to reflect gender as a “situated social practice” with multiple performative possibilities (Lewis, Reference Lewis2014: 4).

Research findings from outside of the management literature have suggested that globally, women entrepreneurs may face numerous contextual barriers not addressed by standard entrepreneurship promotion interventions such as training, networking, or provision of credit (Agarwal, Humphries, & Robeyns, Reference Agarwal, Humphries and Robeyns2005; Duflo, Reference Duflo2012; Kabeer, Reference Kabeer2005; Kabeer, Reference Kabeer2011; Nussbaum, Reference Nussbaum2011; Sen, Reference Sen2004). These include gender-specific hurdles in the form of legal or customary regimes of asset ownership; the inability to enter into contracts without male support; barriers in terms of access to credit; gender-based violence; gaps vis-à-vis men in terms of literacy or numeracy; as well as other factors including healthcare access, time poverty, and the notable influence of additional systemic (not personality-based) factors on the development of entrepreneurial “aspirations” and readiness to accept certain types of risk (Elborgh-Woytek, Reference Elborgh-Woytek2013; International Finance Corporation, 2014; Koch et al., Reference Koch, Lawson and Matsui2014; World Bank Group, 2014; World Bank Group, 2017). Each of these represents a topic of potential interest for CSR scholars. To what extent, therefore, is entrepreneurship-as-usual a means to advancing positive gender outcomes via CSR?

CSR AND FEMINIST SCHOLARSHIP

CSR can be understood as an as activity which “recognizes the social imperatives of business success and addresses its social externalities” (Grosser & Moon, Reference Grosser and Moon2005a: 328). Although the “scope and application of CSR are essentially contested” (Moon & Vogel, Reference Moon, Vogel, Crane, McWilliams, Matten, Moon and Siegel2008: 307), a single definition of CSR is neither possible nor necessary (Carroll, Reference Carroll1999; Moon & Vogel, Reference Moon, Vogel, Crane, McWilliams, Matten, Moon and Siegel2008). CSR is often taken to refer to the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary/philanthropic expectations that society has of organizations (Carroll, Reference Carroll1979; Carroll, Reference Carroll1999). It can be understood as an enduring yet dynamic “cluster concept” which, situated in particular social, political, and economic contexts, helps draw attention to the range of impacts business does or could have on society (Frederick, Reference Frederick1986; Freeman, Reference Freeman2010; Matten & Moon, Reference Matten and Moon2004).

The study of CSR is characterized by a rich diversity of conceptual approaches. These include, for example, work on the stakeholder organization (Freeman, Reference Freeman2010; Carroll, Reference Carroll1991), corporate citizenship (Wood & Lodgson, Reference Wood and Lodgson2002; Matten & Crane, Reference Matten and Crane2005), and corporate social performance (Carroll, Reference Carroll1979; Clarkson, Reference Clarkson1995; Wood, Reference Wood1991). Crane, Matten, and Spence (Reference Crane, Matten and Spence2013) offer what they consider to be six possible “core characteristics” of CSR. These include an understanding of CSR as containing a voluntary component (i.e., not one required by law), attentive to manage externalities associated with business activities, possessing a multiple stakeholder orientation (in contrast to a single orientation, i.e., towards shareholders), seeking alignment of social and economic responsibilities, oriented towards the practices and values of organizations and groups, and encompassing the core activities of a business, i.e., going beyond philanthropy towards CSR as “built in” rather than “bolted on” everyday business practice.

To be sure, CSR calls into question easy distinctions between what is a business issue and what is not, engaging the ethical position of businesses vis-à-vis their market relationships, workplace relationships, as well as relationships with communities and natural environments onto which their operations have an impact (Grosser, Reference Grosser2009). As Grosser reminds us, “while CSR is about what companies are, or are not, doing to behave responsibly towards society, [CSR] is not limited to company actions” (Grosser, Reference Grosser2009: 292). Rather, CSR is irrevocably situated within variegated forms of societal governance, which of course include government and civil society as well as business institutions (Moon & Vogel, Reference Moon, Vogel, Crane, McWilliams, Matten, Moon and Siegel2008).

Gender represents a fundamental feature of social arrangements, impacting on the full range of institutions to which CSR scholarship seeks to be attentive (Marshall, Reference Marshall2007). Nevertheless, while gender concerns did not form a principal feature of the study—or practice—of earlier work on CSR (Barrientos, Dolan, & Tallontire, Reference Barrientos, Dolan and Tallontire2003; Coleman, Reference Coleman2002; Grosser & Moon, Reference Grosser and Moon2005b; Thompson, Reference Thompson2008) more recently, scholarship on CSR and gender has been increasing within CSR-related literatures (Cudd, Reference Cudd2015, Grosser, Reference Grosser2016; Karam & Jamali, Reference Karam and Jamali2013, Karam & Jamali, Reference Karam and Jamali2015; Kilgour, Reference Kilgour2012; Marshall, Reference Marshall2007; Pearson, Reference Pearson2007; Prieto-Carrón, Reference Prieto-Carrón2008; Prugl, Reference Prugl2015; Said-Allsopp & Tallontire, Reference Said-Allsopp and Tallontire2014). For example, work by Karam and Jamali (Reference Karam and Jamali2013) posits the potential of CSR to contribute to “positive developmental change supporting women” both in the Middle East and in “developing countries” more generally (Karam & Jamali, Reference Karam and Jamali2015: 32). Barrientos et al. (Reference Barrientos, Dolan and Tallontire2003) and Prieto-Carrón (Reference Prieto-Carrón2008) examine ethical issues surrounding women and supply chains, and Grosser (Grosser, Reference Grosser2009, Grosser, Reference Grosser2016) explores the possibilities held by CSR to advance the impact of policy instruments around gender mainstreaming and gender equality as well as via women’s NGOs.

Research on CSR has also accommodated various efforts to bring explicitly feminist perspectives to bear on the analysis of CSR. Feminist scholarship is historically and philosophically a broad church (Ahl, Reference Ahl2006; Jaggar, Reference Jaggar1983), and this is reflected in feminist theoretical contributions to CSR literature. Explicitly feminist contributions may be grouped into at least four conversations, with the caveat that these are broad, non-exhaustive categories. One important set of feminist contributions probes key aspects of the influential stakeholder view of the firm, pointing out, for example, ways in which stakeholders may have been implicitly construed as ancillary, rather than integral, to the “basic identity” of a corporation (Buchholz & Rosenthal, Reference Buchholz and Rosenthal2005; Spence, Reference Spence2016; Wicks, Gilbert, Daniel, & Freeman, Reference Wicks, Gilbert, Daniel and Freeman1994). These feminist contributions challenge the view of the firm as an entity that can be meaningfully excised from the relationships and communities in which it is situated, and detail the implications of this analysis (Burton & Dunn, Reference Burton and Dunn1996; Lampe, Reference Lampe2001; Wicks et al., Reference Wicks, Gilbert, Daniel and Freeman1994). A second and partially overlapping body of scholarship concerns feminist ontological and epistemological perspectives on the nature and situation of a firm, emphasizing the need to be attentive to the presence of masculinist assumptions such as atomic individualism (Buchholz & Rosenthal, Reference Buchholz and Rosenthal2005; Wicks, Reference Wicks1996) and the imperative towards control (Wicks, Reference Wicks1996), as well as to the gendered nature of labor markets (Pearson, Reference Pearson2007) and organizational practices (Marshall, Reference Marshall2007) when undertaking CSR scholarship.

A third set of contributions articulates areas in which feminist ethics may advance understanding of corporations and citizenship (Grosser, Reference Grosser2009), governance (Machold et al., Reference Machold, Ahmed and Farquhar2008), business ethics (Borgerson, Reference Borgerson2007), and the practice of gender equality as CSR objective (Grosser, Reference Grosser2009; Larrieta-Rubín, Velasco-Balmaseda, Fernandez, Alonso-Almeida, & Intxaurburu-Clemente, Reference Larrieta-Rubín, Velasco-Balmaseda, Fernández, Alonso-Almeida and Intxaurburu-Clemente2015). Finally, scholarship exploring potential contributions from theorists emphasizing relationship and the ethic of care (much drawing on canonical work from scholars outside the field of business and management including Carol Gilligan, Virginia Held, and Nel Noddings) has sustained a vigorous conversation within CSR-related research across several decades (Burton & Dunn, Reference Burton and Dunn1996; Dobson, Reference Dobson1996; Dobson & White, Reference Dobson and White1995; Simola, Reference Simola2012; White, Reference White1992). Scholarship engaging relationship or care perspectives arguably represents the most frequent engagement with feminist research in CSR-related literatures, though authors have cautioned that scholarship on relationality and care should not necessarily be conflated with feminist perspectives (Borgerson, Reference Borgerson2007; Derry, Reference Derry1996).

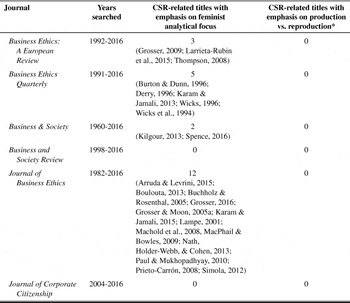

Feminist insights have made important contributions and continue to represent fruitful avenues for analysis across a variety of CSR themes. However, as I show through an analysis of leading journals accommodating CSR-related topics (Table 1), Footnote 13 mainstream CSR research has not directly attended to feminist economics critiques regarding the dichomization of production and reproduction, and engagement with insights from other sources on this issue is sparse within the mainstream literature.

Table 1: Production and Reproduction in CSR Scholarship: A Content Review of Selected Journals

* The third column includes CSR-related articles characterized by a feminist analytical focus, whereas the fourth column refers to CSR-related articles featuring a feminist analysis of the interface between production and reproduction in particular.

Of course, this characteristic lack of engagement does not indicate complete absence of the topic from CSR scholarship. For example, in their analysis of CSR and gender mainstreaming (GM), Grosser and Moon (Reference Grosser and Moon2005a) remind readers that GM acknowledges that all individuals, regardless of their gender, are potential carers, and draws attention to the need to examine the interface between formal work and other aspects of life. Similarly, Thompson (2008: 98) emphasizes financial and social costs associated with the gendered dichotomization of paid and unpaid/care work and argues that “the notion that family and household concerns are alien to the business of productivity” is a key contributor to women’s marginalization. Scholars including Pearson (Reference Pearson2007) and Hayhurst (Reference Hayhurst2014) have moved towards these issues in their CSR-related work, and some scholars in literatures of relevance to CSR topics have explored similar themes (Acker, Reference Acker2006; Barrientos et al., Reference Barrientos, Dolan and Tallontire2003; Elias, Reference Elias2008; Elias Reference Elias2013). However, within much CSR scholarship, such insights are muted at best. I argue that feminist economics offers a concise and coherent framework with which to engage the separation of production and reproduction, and one which is particularly portable for scholars of gender and CSR.

FEMINIST ECONOMICS AND THE DEFINITION OF “WORK”

Critical engagement with the dichotomization of production and reproduction is an area in which feminist economists have made significant contributions. Like other heterodox economic approaches, feminist economics seeks to provoke a shift in mainstream economic thought. In order to accomplish this, the field has engaged a variety of intellectual tasks vis-à-vis standard economic theory and practice, including the identification of apparently unarticulated assumptions present in conventional approaches (England, Reference England, Ferber and Nelson1993; Ferber & Nelson, Reference Ferber, Nelson, Ferber and Nelson1993; Nelson, Reference Nelson, Ferber and Nelson1993; Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Humphries and Robeyns2005), the introduction of systematically underexplored or unexplored topics to research agendas (Folbre, Reference Folbre1994; England & Folbre, Reference England, Folbre, Ferber and Nelson2003; Humphries, Reference Humphries2011), engagement with nonstandard epistemological approaches (Ferber & Nelson, Reference Ferber, Nelson, Ferber and Nelson1993; Jennings, Reference Jennings, Ferber and Nelson1993), and, at a fundamental level, a re-framing of the ends and aims of the discipline itself. Reflecting on the field, Ferber and Nelson summarize this latter effort; maintaining, “We challenged the definitions of economics based on rational choice theorizing and markets and suggested instead a definition centered around the provisioning of human life” (Ferber & Nelson, Reference Ferber, Nelson, Ferber and Nelson2003: 1). Nancy Folbre has described the task of the field as follows, “The point is not that conventional political economy fails to put gender first, but rather that it underestimates its importance within the larger picture” (Folbre, Reference Folbre1994: 50).

Because feminist economics is not well known in mainstream CSR research, I will provide a review of one strand of thought within that corpus that is particularly relevant to questions surrounding female entrepreneurship. This is the historical and theoretical tension present in the question of how “work” is defined, including the separation of production from reproduction.

Nancy Folbre’s (Reference Folbre1994) book, Who Pays for the Kids? Gender and the Structures of Constraint, places the question of the definition of work within a broad social critique. Folbre sets out a sophisticated analysis of how both collective and individual action relate to the formation of social structures. She emphasizes the difficulty of making generalizations about groups in society, given that individuals maintain affiliation with multiple groups at any given time based on complex factors including socioeconomic status, age, race/ethnicity, religion, family circumstances, and gender. Yet, with these caveats in place, Folbre continues to speak of women as a group—particularly a group of economic actors—and emphasizes the role of gender in the formation of markets and economic systems.

One reason Folbre feels able to speak of women as a group is that her analysis offers extensive evidence of women’s disproportionate participation, relative to men, in unpaid/care work (reproduction). Indeed, one of Folbre’s core observations is that work undertaken in the care of others—children, the elderly, and the less able—has been systematically undervalued and rendered all but invisible to public policy and management. Her scholarship traces a process through which, within classical liberal economic theory, the market and the home became formally understood to inhabit “separate spheres.” The market sphere was and is understood to be masculine, public, and “productive,” the home sphere feminine, private, and progressively imagined to be non-economic or “unproductive.” This approach to the separation of productive and reproductive spheres, she argues, is firmly reflected in contemporary economic institutions.

It is on this understanding of women’s conventional dominion over an “invisible” form of work that Folbre builds her gender analysis. Her insight is a powerful articulation of longstanding critiques of the dichotomization of production and reproduction originating from a variety of fields. She points out that these fundamental tensions between unpaid/care work and market work hold regardless of the gender of the person undertaking the activities. This perspective is particularly valuable in that it can be sustained without reliance on essentialisms, i.e., the use of stereotypes about the character, personality, or preferences of any individual woman or women as a group. Human beings are, of course, irrespective of gender, “individuals-in-relation” who receive and give care at various points in the life cycle (Nelson, Reference Nelson2010: 243). However, Folbre presents compelling evidence that norms, incentives, policy, and law often combine to ensure that women are—as a group and relative to men—engaged in work in the reproductive sphere to such an extent that it is no insignificant factor in their engagement with market endeavors.

Production and Reproduction: Key Concepts

Diane Elson defines reproduction as “a non-market sphere of social provisioning, supplying services directly concerned with the daily and inter-generational reproduction of . . . human beings” (Elson, Reference Elson2010: 203). Reproductive labor thus encompasses “unpaid work in families and communities” (Elson, Reference Elson2010: 203; Folbre Reference Folbre1994: 3) relating to the “care, socialization, and education” of others. Similarly, production can be traditionally understood to refer to formal or informal paid activities that contribute to a good or service that can be exchange for a money price (Elson, Reference Elson2010). A range of commentators have suggested that finance and production arguably “free ride” on reproductive work, without which “economies would simply not function” (Acker, Reference Acker2006; Folbre, Reference Folbre1994: 3; Sepulveda Carmona, Reference Sepulveda Carmona2013; United Nations Economic and Social Council, 2016: 1). Feminist economists employ two concepts: “the study of provisioning” and “social reproduction” to overcome the apparent stalemate between production and reproduction in the analysis of individuals’ and groups’ economic behavior. On this topic, their fundamental argument is that production and reproduction are neither separate nor cleanly separable, and that their dichotomization has highly gendered effects.

Julie A. Nelson has set out the case for economics as the study not primarily of choice, but of “provisioning.” She is incredulous that the distinction between “productive” and “unproductive” labor, i.e., that which results in the production of a good exchangeable for money and that which does not, is a useful one. She posits:

What is needed is a definition of economics that considers humans in relation to the world . . . Focusing economics on the provisioning of human life, that is, on the commodities and processes necessary to human survival, provides such a definition (Nelson, Reference Nelson, Ferber and Nelson1993: 32).

Nelson argues that human survival, in this context, evidently includes survival through childhood, bringing care, nonmaterial services, and family labor “into the core of economic inquiry… just as central as food or shelter” (Nelson, Reference Nelson, Ferber and Nelson1993). Nelson points out, (not without irony), “[t]he Greek root of both the words ‘economics’ and ‘ecology’ is oikos, meaning ‘house.’” In a reversal of the ancient Greek distinction, then, between women’s assigned role in the private oikos and not the public polis, she suggests, “economics could be about how we [as society] live in our [collective] house” (Nelson, Reference Nelson, Ferber and Nelson1993: 33).

Such a perspective opens intriguing analytical space, especially when taken alongside Nancy Folbre’s use of the concept of “social reproduction.” Footnote 14 While social reproduction is a widely employed concept across a range of disciplines, Folbre reminds her readers that social reproduction is by no means limited to care for family members. This lens loosens the strictures placed on caregivers as unproductive “dependents,” reframing them as crucial contributors to economy and society. Social reproduction introduces the need to “devise broader and better kinds of support for nonmarket work,” including that conducted for those who do not happen to have a biological relationship with the caregiver. Crucially for those working within CSR, Folbre emphasizes that ignoring unpaid/care work has been shown to reduce women’s wellbeing and bargaining power (Folbre, Reference Folbre1994: 10). She points out that while liberal economic paradigms may bring individual freedoms and challenge traditional social norms, they can also “foster new concepts and definitions that exaggerate the relative importance of market work” (Folbre, Reference Folbre1994: 10) in ways that materially disadvantage women.

Insights from feminist economics on what counts as work—and whose work counts—remind scholars of gender and CSR that the distinction between production and reproduction represents a theoretical position, not an ontological reality. Nonmarket settings “produce”—non-trivially—subsequent generations of employers, employees, paid and unpaid caregivers, taxpayers, and entrepreneurs (Folbre, Reference Folbre1994). Because of this, a case is made for a view of economic life that includes all work, paid and unpaid, which takes place within and outside “market exchange.” This is not to ignore the reality of tradeoffs between paid and unpaid/care work, but to observe that how these tensions manifest, and for whom, is determined by social norms, systemic constraints, and structural factors.

ENTREPRENEURSHIP LITERATURE: PERSPECTIVES ON WORK

In Why Research on Women Entrepreneurs Needs New Directions, her influential Footnote 15 article in entrepreneurship’s foremost academic journal, Helene Ahl (Reference Ahl2006) identifies what she calls “the division between work and family” as one of ten discursive practices characteristic of entrepreneurship research (604). Footnote 16 She asserts that entrepreneurship literature reflects an implicit understanding of work as an activity undertaken in a public “sphere,” apart from family, which is defined to exist in a private, individualized domain (604-5). In the same analysis, Ahl also argues that entrepreneurship research tends not only to assume that “work” and “family” represent two theoretically and empirically distinct poles of human endeavor, but also to “position the family as being a problem . . . an impediment for a woman to start and run a business” (605, italics added). Thus, though she does not directly discuss the interface between production and reproduction in her article, Ahl’s work, along with that of others (Aldrich & Cliff, Reference Aldrich and Cliff2003; Bird & Brush, Reference Bird and Brush2002; Brush et al., Reference Brush, De Bruin and Welter2009), provides an entry point for analysis of entrepreneurship in light of insights about the nature of work.

Because of the influence of the literature, the framing of these issues within entrepreneurship research has important implications for CSR programs emphasizing women’s entrepreneurship. In this section, I ask: Does entrepreneurship scholarship engage with unpaid/care and provisioning activities Footnote 17 as a form of work, i.e., rather than as one among many demographic or individual-level characteristics that may or may not contribute to entrepreneurial failure/success? If so, how? Put another way, to what extent do contemporary approaches to entrepreneurship appear to reflect the classical claim that production and reproduction can be cleanly separated from one another, and/or that they occupy separate (and often gendered) spheres, only one of which—the market sphere—holds substantial economic significance?

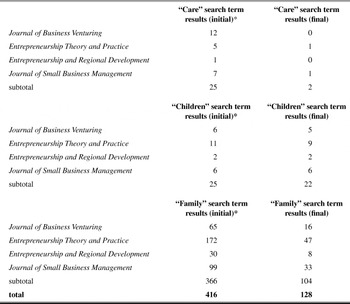

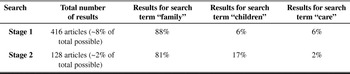

To engage these questions, I undertook a systematic three stage search of the terms “care,” “children,” and “family” as well as terms related to the elderly and disabled, Footnote 18 in leading journals from the field of entrepreneurship: Journal of Business Venturing (searched 1985-present, 1,800 total articles), Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice (searched 1988-present, 1,350 total articles), Entrepreneurship and Regional Development (searched 1998-present, 340 total articles), and Journal of Small Business Management (searched 1971-present, 1,760 total articles). In Stage 1, each search term was applied to the abstract, keywords, subject description, and title of articles within each journal. Since these words can be used in much wider contexts (e.g. health care), in Stage 2, results of each search were examined using more detailed exclusion criteria set for each search (Table 2) in order to identify articles appropriate for further (Stage 3) analysis. Table 3 presents the results of Stages 1 and 2 of the search.

Table 2: Review of Unpaid/Care Work in Entrepreneurship Literature (Stage 2)

* Initial results are distinguished from final results based on the application of exclusion criteria. For “care,” initial results were excluded from final results when related to health, medical care, or healthcare systems. For “children,” results were excluded when reference was to non-dependent children (e.g. management succession for adult children in a family firm). For “family,” results were excluded when the term was used exclusively as a descriptor, i.e., in reference to a “family firm.”

Table 3: Does Entrepreneurship Literature Engage Unpaid/Care Work?

Does the entrepreneurship literature engage unpaid/care work? Stage 1 and 2 analysis indicates that the answer is largely no. The entrepreneurship literature contains relatively limited engagement with unpaid/care work related themes, with ~2% of over 5,000 articles across several decades emphasizing this topic. When entrepreneurship research does address unpaid/care work, Stage 1 and 2 analysis shows they most frequently do so through a generalized reference to “family.”

With this established, I sought to answer how entrepreneurship engages unpaid/care work. To accomplish this, I analyzed the content of each of the 128 articles remaining from Stage 2 in depth. My aim in this (Stage 3) was to identify and analyze articles that engaged family as a form of work, i.e., that provided at least a minimal level of detail about the nature of care-related or unpaid labor undertaken by entrepreneurs (a reference to time allocated to childcare, or to housework, for example). In so doing, I ensured that my analysis in fact represented meaningful reflections on entrepreneurship scholarship’s engagement with unpaid/care work and the division between productive and reproductive labor. Upon completion of Stage 3 of the literature search, just 35 articles (2 for “care,” 9 for “children,” 24 for “family”) of the 128 possible articles were found to substantively engage these themes.

Entrepreneurship, Production, and Reproduction: Findings

Entrepreneurship scholarship engages the interface between production and reproduction to a limited extent, and in a relatively cursory manner. A comprehensive analysis of the 35 articles identified following Stage 3 of this review illustrates how entrepreneurship does engage this interface, when it does so. Footnote 19 Three tendencies emerge from the review. First, entrepreneurship appears to understand “family” (its closest reference to unpaid/care or reproductive work) as dichotomous to production or market work, casting business as either ontologically separate to or cleanly separable from family. Second, entrepreneurship tends to assume that the dichotomous relationship between production and reproduction is one characterized primarily by conflict or tension between two inherently incompatible realms. Some scholars signal alertness to the ways in which the institutions and norms constituent of these realms have been socially and historically composed, but many appear to simply take their incommensurability as given. Third, entrepreneurship appears to uphold a gendered separation of spheres. Scholarship investigating how women entrepreneurs manage conflict between “business” and “family” is relatively commonplace. No articles dedicated to this topic could be identified for male entrepreneurs in this review. Just 8 of the 35 articles included in the final review made any mention of male engagement with unpaid/care work. In 5 of these 8 articles, the mention was made only to note that males’ unpaid/care role was secondary to the unpaid/care work of females.

One note before proceeding: in my analysis, I by no means wish to imply that market and unpaid/care work are simply interchangeable. I acknowledge them as two types of activity that possess distinctive features, often governed by different logics by those who undertake them. Indeed, they are frequently experienced as existing in conflict with each other. The trade-offs demanded of those who engage in both types of activity are well documented across a variety of literatures. With this caveat in place, the point I wish to make is that the gendered separation of production and reproduction is typically taken as given in entrepreneurship, and that feminist economic analysis makes clear that this is erroneous. Production and reproduction may be experienced as distinct and governed by different logics, but this is not because they are ontologically separable in any “natural” sense. While some aspects of reproduction may be incompatible with some aspects of production, others may not be. Norms and institutional arrangements strongly mediate the extent to which these distinctions manifest, and for whom. Yet, institutional arrangements structuring the interface between paid and unpaid/care work were given attention in just three (Lee, Wong, Foo, & Leung, Reference Lee, Sohn and Ju2011; Lerner et al., Reference Lerner, Brush and Hisrich1997; Williams, Reference Williams2004) of the 35 articles analyzed in this review. Only one (Williams, Reference Williams2004) explicitly makes the case that policies to support entrepreneurship could be considered alongside childcare policy. In this sense, Williams acknowledges that while production and reproduction may possess their own distinctives and tensions, the nature of the interface between business and unpaid/care work is contingent and context-dependent.

To conclude this section, I briefly discuss examples from entrepreneurship of production and reproduction as dichotomous, in conflict, and gendered.

Unpaid/Care Work is Dichotomous to Entrepreneurial Activity

In her study of entrepreneurs’ personal motivations and value systems, Fagenson (Reference Fagenson1993) presents family and work as two fundamentally dissimilar activities pursued by individuals motivated by divergent personal values. Similarly, work by Morris et al. (2006: 239) explores whether women were “pushed” or “pulled” into of entrepreneurship by examining the nature of their personal motivations. In so doing, the authors draw a distinction between what they call “wealth or achievement factors” as opposed to “family motives.” This article concludes (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Miyasaki, Watters and Coombes2006: 240) that growth, i.e., the pursuit of non-family objectives in the economic realm, is a “deliberate choice” and that women have to “make careful trade-off decisions” as they navigate these opposing realms. Such work archetypically assumes that the pursuit of one realm or the other is the outcome of a process of personal choice and individual preference rather than a balancing of two different types of valuable work.

Unpaid/Care Work is in Conflict with Entrepreneurial Activity

The entrepreneurship literature features an established conversation on work and family. However, family is most frequently perceived to be not only dichotomous to but also in conflict with business activity. Iterations of the entrepreneurial work-family conflict metaphor are numerous in the literature.

Entrepreneurship’s engagement with “work-family conflict” overwhelmingly emphasizes the experience of women entrepreneurs navigating care for young children (Eddleston & Powell, Reference Eddleston and Powell2012; Lee, Sohn, & Ju, Reference Lee, Sohn and Ju2011; Winn, Reference Winn2006). Shelton (2006: 285) examines strategies undertaken by women entrepreneurs to manage “work-family conflict” by “manipulating roles.” Here family is vaguely cast in terms of the fulfillment of a “role,” yet the fundamental work and activities constituent of this role are left largely unarticulated. The article suggests women pursue one of three strategies for manipulating roles: role elimination, role reduction, and role sharing. Because the interface between family and entrepreneurship is taken to be negative, role management by women entrepreneurs is presented as a crucial aspect of female entrepreneurial success.

The entrepreneurship literature contains repeated affirmations that entrepreneurs, women in particular, face significant conflict between work and family. This conflict is primarily seen as arising from the family side of these two opposing spheres. Women’s care for young children is perceived as particularly aberrant vis-à-vis business pursuits.

Production and Reproduction Assigned to Gendered Spheres

Analysis by DeMartino and Barbato (Reference Demartino and Barbato2003) is a helpful illustration of how scholarship on the individual motivation of entrepreneurs may reify a gendered conceptual split between production and reproduction. Their study posits the existence of individual level “motivational differences” between male and female MBA-educated entrepreneurs in the United States:

The findings of this study, confirming earlier research, suggest that women are motivated to a higher degree than equally qualified men to become entrepreneurs for family-related lifestyle reasons. Women are less motivated by wealth creation and advancement...These differences became even larger when the comparison is between married women and men entrepreneurs with dependent children (DeMartino & Barbato, Reference Demartino and Barbato2003: 816).

The article goes on to detail a distinction between individual orientations towards “family/lifestyle” and “wealth/advancement” (DeMartino & Barbato, Reference Demartino and Barbato2003: 821). In such work, entrepreneurship tends to focus on an individual level of analysis in response to what feminist economists would contend to be systemic, institutional level concerns.

More recent articles in the review suggest that some entrepreneurship scholars are seeking to reconcile the gendered dichotomization of “work” and “family.” However, as in work by McGowan et al. (Reference McGowan, Redeker, Cooper and Greenan2012), the case that production and reproduction must be more unified on a conceptual level has not overtly been made. In their work, McGowan et al. (2012: 68) advocate a view of work and family and work spheres characterized by permeable boundaries, but note that their research suggests that “for most women obtaining and maintaining an appropriate balance between the domestic and business spheres of their lives remained a constant challenge and source of tension and stress.” The article provides tools with which to engage the work-family interface in nuanced ways. However, it nevertheless manifests underlying assumptions about the tensions between reproduction and production, tacitly framing children as primarily individual, private goods maintained by individual women who opt to “balance” such obligations. While the theme of care as a “lifestyle choice” is not nearly as unambiguous in this article as in others, the piece stops short of engagement with the full range of unpaid/care work, as well as the social, political, and economic significance of reproductive work.

Entrepreneurship research reflects a long-standing gendered division between production and reproduction. To close this section, therefore, it is not altogether trivial to examine the earliest article analyzed for this review. In his 1974 Journal of Small Business Management piece, Mancuso (1974: 18) addresses “Mr. Reader,” arguing, “everybody knows only a handful of women have started an ongoing business enterprise from nothing.” The primary aim of the piece is to identify the specific personality and character traits definitive of entrepreneurs; a process that the author intriguingly takes to have its roots in childhood. He asks:

When other kids were out playing ball, why was he [the entrepreneur] busy hustling lemonade? When his friends were dating cheerleaders, why was he organizing rock concerts? . . . Or marketing grandmother’s pickle recipe? (Mancuso, Reference Mancuso1974: 16).

Notably, the environment of security and provision from which this individual hustled lemonade was, of course, one created and sustained by provisioning work; the ongoing preparation of meals, support of the development of mathematical and language skills required for sales, and (one might imagine), the free supply of lemons, sugar, reliable clean water and other inputs, not to mention of grandmother’s pickles.

This anecdote serves to illustrate the ways in which production and reproduction are, in fact, incredibly difficult to disentangle. However, their conceptual separation is a long-standing, taken-for-granted norm within business and management. One outcome of this is that unpaid/care work is systematically obscured and underestimated within research agendas. As a result, even when seeking to engage explicitly with family, the entrepreneurship literature has tended to perpetuate a vision of an individual entrepreneur active in a market setting, without meaningful engagement with the unpaid/care work that enables markets. It is easy to look askance and perhaps even smirk at some of the assumptions and conclusions made so explicit in Mancuso’s article. The piece may read, on the one hand, as from another era. But, it is not amiss to probe whether entrepreneurship’s engagement with unpaid/care work has truly made a conceptual shift in the decades since Mancuso’s musings on baseball, cheerleaders, and lemonade stands.

PRODUCTION AND REPRODUCTION: A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR SCHOLARS OF GENDER AND CSR

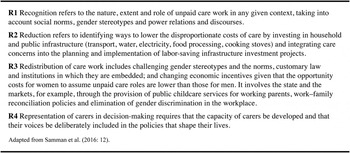

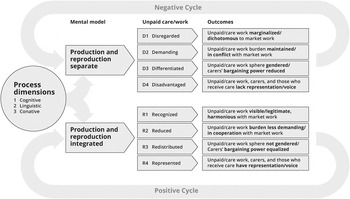

What is to be gained by scholars of gender and CSR by looking at the CSR, entrepreneurship, and feminist economics literatures in combination? Drawing on the “4R” framework (Figure 1) for analysis of unpaid/care work (Samman, Presler-Marshall, & Jones, Reference Samman, Presler-Marshall and Jones2016), Footnote 20 I propose a framework (Figure 2) that attends to the recognition (R1), reduction (R2), redistribution (R3), and representation (R4) of unpaid/care labor within the context of CSR. This is a tool for theory building that draws attention to the dichotomous, conflictual, and gendered nature of the relationship between production and reproduction.

Figure 1: The 4R Framework for Understanding Unpaid/Care Work

Figure 2: Production and Reproduction in CSR

Such an understanding of the relationship between productive and reproductive work constitutes what Basu and Palazzo (2008: 123) call a “mental model” in their work on CSR and sensemaking. Sensemaking can be understood as “a process by which individuals develop cognitive maps of their environment” (Ring & Rands, Reference Ring, Rands, van de Ven, Angle and Poole1989: 342). From a sensemaking perspective, the shape of CSR activities is determined not as a result of “external demands, but instead from organizationally embedded cognitive and linguistic processes” (Basu & Palazzo, Reference Basu and Palazzo2008: 123). Thus, “mental models” which lie beneath sensemaking “influence the way the world is perceived [by organizations]” (Basu & Palazzo, Reference Basu and Palazzo2008: 123) and shape organizational responses to stakeholders. In short, for Basu and Palazzo, “decisions regarding CSR activities are taken by managers, and stem from their mental models regarding their sense of who they are in their world” (Basu & Palazzo, Reference Basu and Palazzo2008: 124). Their framework is concerned with three process dimensions of CSR: cognitive, linguistic, and conative (behavioral), i.e., “what CSR thinks, says, and does” (Basu & Palazzo, Reference Basu and Palazzo2008: 132).

To build my conceptual model, I use the 4R framework to draw attention to outcomes related to process dimensions of CSR, with particular attention to mental models related to the separateness or integration of production and reproduction (Figure 2). In this model, outcomes follow a framework I call the “4Ds,” which manifest when the “4Rs” are absent or weak. In this case, process dimensions of CSR result from a mental model in which production and reproduction are perceived to be inescapably separate. This in turn leads unpaid/care work to be disregarded (D1) where it could be recognized (R1). Overlooking unpaid/care work means the burden of this work remains demanding (D2) where it could be reduced (R2). A perception of production as separate from reproduction perpetuates processes and structures in which responsibility for unpaid/care work is differentiated (D3) between genders, when in fact it could be redistributed (R3) between men and women. Finally, when the performance of unpaid/care is understood not as work but a matter of duty, culture, or economically trivial individual “lifestyle choice,” unpaid/care work—as well as anyone who depends on or performs it—tends to be disadvantaged (D4) instead of represented (R4) in public forums.

The model describes outcomes associated with each of the 4Rs and 4Ds, and identifies the circular nature of CSR processes and outcomes. For example, when mental models (cognitive processes) characterized by the perceived ontological separateness of production and reproduction influence CSR managers, unpaid/care work is likely to be unnoticed or disregarded (D1) within the operational (conative) and communication (linguistic) aspects of CSR programing. The outcome of D1, in this case, is that unpaid/care work is overlooked while CSR strategy and activity emphasize—ostensibly dichotomous—market activities such as business training, networking, or finance for women entrepreneurs. The marginalization of unpaid/care work within the linguistic and conative processes of CSR reinforces the mental model of distance between production and reproduction within the cognitive process dimensions of CSR, and thus the cycle perpetuates. It is this iterative, implacable character of the connection between CSR processes and unpaid/care work outcomes that the model accentuates. Equally, the model also points to a way forward: where cognitive processes acknowledge unpaid/care as a relevant aspect of work, it can be recognized (R1) as a visible, legitimate, and valuable endeavor with important implications for market work. The communication (linguistic) and conative (programmatic) aspects of CSR in turn reify the status of unpaid/care work—and those who benefit from and perform it—away from that of a business non sequitur.

Conceptual Framework: Implications

This model allows scholars of gender and CSR to engage questions about production and reproduction through their research. While it is little explored in current scholarship on CSR and gender, unpaid/care work is receiving increasing attention as a “major human rights issue” (Sepulveda Carmona, Reference Sepulveda Carmona2013), corroborating its place as a topic of relevance for the theory and practice of CSR. For example, research suggests that in many contexts, when a female caregiver’s unpaid/care work is experienced as incompatible with her market work, female children may be substituted into unpaid/caregiving roles, often to the detriment of their own wellbeing (Sweetman, Reference Sweetman2014). An estimated 35.5 million children under five years old are left alone or in the care of a child under ten years old for an hour or more each week across the world—a number larger than the total number of children under five in all of Europe (Samman et al., Reference Samman, Presler-Marshall and Jones2016). Globally, household chores such as fetching clean water and gathering firewood dramatically impact the lives of many women and girls. The United Nations estimates that 90% of the water and firewood provisioning work in Africa is done by women or girls, and that these tasks can demand up to six hours of time daily. Innovations in transport, water infrastructure, and energy can therefore have a significant impact on girls and women (Ferrant, Pesando, & Nowaka, Reference Ferrant, Pesando and Nowacka2014; Samman et al., Reference Samman, Presler-Marshall and Jones2016; Sweetman & Deepta, Reference Sweetman and Deepta2014). For scholars of gender and CSR, this context is significant not least because globally, women spend between two and ten times more hours on unpaid/care work than do men (United Nations Development Program, 2006a). In addition, female relative specialization in unpaid/care work is linked to higher gender wage gaps, lower levels of female labor force participation, and gender gaps in terms of job quality (Ferrant et al., Reference Ferrant, Pesando and Nowacka2014).

Prominent institutions ranging from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to Oxfam to the World Bank have recently drawn attention to the topic of unpaid/care work and women’s empowerment (Gates, 2016; Hegewisch & Niethammer, Reference Hegewisch and Niethammer2016; Samman et al., Reference Samman, Presler-Marshall and Jones2016; Slaughter, Reference Slaughter2016; Sweetman & Deepta, Reference Sweetman and Deepta2014; Woetzel et al., Reference Woetzel, Madgavkar, Ellingrud, Labaye, Devillard, Kutcher, Manyika, Dobbs and Krishnan2015). Oxfam has identified unpaid/care work a little- acknowledged contributor to the “glass wall” holding women back from equality in many contexts (Kidder, Reference Kidder2014), and the United Nations has stated that:

The unequal distribution of unpaid/care work undermines the dignity of women caregivers; makes them more vulnerable to poverty; and prevents them from enjoying their rights—to work, to education, to health, to social security and to participation on an equal basis with men (Sepulveda Carmona, Reference Sepulveda Carmona2013: 4).

Against this backdrop, theory building on gender and CSR requires conceptual frameworks with which to critically engage the interface between production and reproduction. The framework I have presented meets this need by providing scholars of CSR and gender a highly portable tool with which to constructively consider the phenomenon of unpaid/care work in their research.

In this article, I have focused on CSR programs that aim to advance gender outcomes via promotion of women’s entrepreneurship. However, CSR engages gender in many ways, including via initiatives in supply chain and sourcing, training, and public communication on gender themes, to name a few. Footnote 21 The model I propose enables analysis of the process dimensions of CSR associated with such programs, and facilitates exploration of a range of important research questions including:

Cognitive processes: Under what conditions do CSR managers’ norms, attitudes, and values (cognitive processes) affect the gender outcomes of the programs they support? Which features of gendered experience might be recognized/disregarded as a result of CSR managers’ mental models? In what contexts do CSR managers attend to/seek out information about unpaid/care work? In which contexts are mental models that aim to recognize, reduce, redistribute, and/or represent unpaid/care work able to become normative? When and how might CSR unreflectively contribute to unpaid/care work being disregarded, persistently demanding, differentiated between men and women, and disadvantaged in public fora?

Linguistic processes: What norms regarding the gender-differentiated nature of production and reproduction are expressed via CSR communications? To what extent does this communication recognize unpaid/care work? To what extent does it disregard or even obscure/delegitimize unpaid/care work? How do the stakeholders with whom CSR programs engage interpret messaging about gender norms around work? Under what circumstances can CSR communications support the redistribution of unpaid/care work between genders? In what contexts can corporate communications advocate for the representation of unpaid/care work in public settings?

Conative (behavioral) processes: How do program operations change when program design recognizes unpaid/care work? How do these changes impact stakeholders? Are questions about unpaid/care work and/or metrics to capture this labor included in program design? In what contexts can CSR programs support innovation to improve efficiency associated with unpaid/care tasks and thus reduce the burden of these tasks so they are less demanding?22 What actions can CSR programs take to enable the redistribution of unpaid/care work between the men and women impacted by their initiatives? Which actions can CSR leaders use to parlay their strategic influence into increased representation for unpaid/care work in policy and public forums?

CSR impacts on unpaid/care work through its cognitive, linguistic, and conative processes. When influenced by a mental model of taken-for-granted distance between production and reproduction, unpaid/care work is likely to be disregarded and disadvantaged, as well as remain demanding and gender differentiated under the processes of CSR. However, a different mental model can lead CSR processes to generate more positive outcomes. First, CSR processes can help unpaid/care work to be recognized. This might be accomplished by CSR initiatives that create metrics to capture time use and unpaid/care work, seek a deeper understanding of country circumstances including the availability/lack of social safety nets and resources for care available, or raise awareness of the impact of unpaid/care work on market outcomes for women. Second, processes of CSR might reduce unpaid/care work by, for example, innovating to improve task productivity, the organization of care, or by supporting expansion of access to key care infrastructure. Third, CSR can help redistribute unpaid/care work between men and women through corporate policies and program design, as well as by engaging with men on norms as part of CSR efforts. Finally, CSR can facilitate the representation of unpaid/care work via engagement with policymakers and other stakeholders on the topic, for example through advocacy to maintain or expand key care-related services.

The model I present in this article provides a conceptual framework through which to examine the implications of the separation of production and reproduction in CSR scholarship. It also offers scholars a useful tool for analysis of the status of unpaid/care work in CSR practice. These contributions are possible because of the premise behind the model: that the relationship between production and reproduction is not given, but rather that it is shaped by norms, institutions, and structural factors. When CSR programs are blind to unpaid/care work, they may fail to advance women’s wellbeing, and even cause unintended harm. When CSR programs assume production and reproduction to be separate, some women may stand to benefit economically. But, other, more vulnerable women—including school-age girls and women of lower socioeconomic status—may take up unpaid/care work with deepening inequalities as a result.

In the development of this article, I engaged senior leaders of several high-profile CSR programs aiming to empower women through entrepreneurship for comment on their experience with unpaid/care work via their initiatives. As one replied, the area is crucial yet underexplored: “I must admit we’ve done nothing related to care within the design of our projects, except for a very small program… It really is the next focus area and worth exploring” (Firm 1 informant). Another noted that unpaid/care work appears to impact the success of her large, global program with women entrepreneurs, noting, “we haven’t really researched the issue [of how unpaid/care work impacts our initiative], but it’s something our team definitely sees, particularly in our international markets.” She went on to observe that while many women in the program she runs initially view entrepreneurship as “something they can do part time while they are raising kids . . . as their enterprises mature, it can be harder to strike that balance . . . it seems there is a nexus between care and growth” (Firm 2 informant). Another executive reflected:

We tend to take [unpaid/care work] as a given constraint [for women with whom we work] and adjust our [program] expectations from there. I’ve really never thought about questioning that constraint [through our programs]. But we could and we should (Firm 3 informant).

Still another informant pointed to a forthcoming study by the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation on the business case for corporate-supported childcare in emerging and developing economies (Policy Institute informant). For scholars of gender and CSR, the need for rigorous analysis of the interface between production and reproduction is urgent and growing.

CONCLUSION

My analysis demonstrates that mainstream approaches to entrepreneurship habitually reflect a longstanding, artificial separation of production and reproduction into separate, gendered spheres. In the absence of critical reflection on the dichotomization of these spheres, entrepreneurship as an approach to CSR may reflect the internal bias that “work” is that which is done for pay in a market context, and the rest is “life” or economically trivial personal “choice.” Such biases, if they remain unacknowledged, may hamper the gender empowerment outcomes of CSR programs.

Unpaid/care work provides the absolutely essential foundations for any other kind of work, entrepreneurship included. The conceptual framework introduced in this article demonstrates that, if attuned to issues brought forth by the feminist economics analysis of “work,” CSR can recognize, reduce, redistribute, and help represent unpaid/care work (the “4Rs,” featured in Samman et al., Reference Samman, Presler-Marshall and Jones2016), in the service of women’s empowerment. Alternatively, when such insights are overlooked, CSR entrepreneurship projects can lead unpaid/care work—and those who undertake and rely upon it—to be disregarded as the burden remains demanding and differentiated between genders, disadvantaged in public and policy settings (the “4Ds,” my own), leading to deepening inequalities. Thus, the need for greater sophistication among CSR scholars and practitioners concerning the definition of “work” is evident.