We are not here to build friendships, we are here to serve a common goal.Footnote 1

My feeling is that even if one has a position of responsibility, that does not prevent one from having some… interest for the person and not only for the work produced.Footnote 2

Many scholars advocate the promotion of care in organizations (Barsade & O’Neill, Reference Barsade and O’Neill2014; Colbert, Bono, & Purvanova, Reference Colbert, Bono and Purvanova2016; Dutton & Ragins, Reference Dutton and Ragins2007; Gittell & Douglass, Reference Gittell and Douglass2012; Lawrence & Maitlis, Reference Lawrence and Maitlis2012; Rynes, Bartunek, Dutton, & Margolis, Reference Rynes, Bartunek, Dutton and Margolis2012). The general consensus is that workplaces are better places when coworkers care for each other, and that caring relationships make organizations more productive. Some scholars also argue that care for coworkers is a moral good (Liedtka, Reference Liedtka1996; Peus, Reference Peus2011; Solomon, Reference Solomon1998), and that organizations have a moral duty to promote care in the workplace. Caring for one’s work is thus another way to care for coworkers, as well as customers and suppliers (Burton & Dunn, Reference Burton and Dunn1996; Liedtka, Reference Liedtka1996).

Yet responsibilities for work and for coworkers in the workplace are not always compatible. Caring for work and for coworkers may converge, as in helping-on-the-job situations (e.g., Chou & Stauffer, Reference Chou and Stauffer2016; Grant & Patil, Reference Grant and Patil2012), where caring for coworkers supports work objectives and may have positive organizational outcomes (e.g., Kao, Cheng, Kuo, & Huang, Reference Kao, Cheng, Kuo and Huang2014). However, in many other work situations, there is implicit or explicit conflict between the two. When achieving organizational objectives requires personal sacrifices with respect to one’s wellbeing, health, or work–life balance (Karasek, Reference Karasek1979; Pfeffer, Reference Pfeffer2016), “caring” about work all too often becomes a priority, and caring for coworkers may interfere with this. It has been argued that the prevailing work-centered ethos (Weber, Reference Weber and Parsons1930), enhanced by the capitalist pursuit of profit, constrains the possibility of care and compassion in the workplace (Fotaki & Prasad, Reference Fotaki and Prasad2015; George, Reference George2014). Caring in the workplace is thus a complex practice that may confront coworkers with ethical dilemmas and trade-offs.

Ethicists of care have unveiled the everyday ethical dilemma of managing competing responsibilities (Tronto, Reference Tronto1993, Reference Tronto2010). Organizations may also develop distinct practices (Nicolini, Reference Nicolini2012) in dealing with the dilemma of care allocation. In the opening quotations, Fanny, a participant in our study, brushes aside any dilemma in insisting that the primary purpose of work relationships is to further the organization’s objectives, not “to build friendships.” In contrast, Marie-Claire explicitly recognizes care for both the “person” and “the work produced.” Hence, she raises the dilemma of care allocation between work and coworkers, while Fanny does not. In each of the two organizations we studied, we were surprised that a distinct care allocation was maintained across various coworker relationships and interactions. Since care allocation is an inherently ethical dilemma (Held, Reference Held2006; Tronto, Reference Tronto1993), we would have expected to observe constantly changing practices arising from the tension of this dilemma. In this article, we ask how employees deal with the care allocation dilemma, and how specific care allocations are maintained in organizations.

We conducted an in-depth qualitative study of two contrasting cases in order to understand how employees may maintain allocations of care specific to their organization. We identified the role of “boundary work”—the effort to construct, dismantle, or maintain symbolic and social distinctions and demarcations (e.g., Lamont & Molnár, Reference Lamont and Molnár2002; Langley, Lindberg, Mørk, Nicolini, Raviola, & Walter, Reference Langley, Lindberg, Mørk, Nicolini, Raviola and Walter2019)—through which employees negotiated the boundary of their caring responsibilities towards work vis-à-vis their coworkers in everyday organizational practices. In Fanny’s workplace, a communications agency (COMMS), the care allocation dilemma was actively suppressed. We found that this was achieved by maintaining a symbolic boundary between coworkers’ professional and personal selves. In Marie-Claire’s workplace, a public child protection agency (SERV), coworkers’ reluctance to erect a boundary between their professional and personal selves allowed the need to care for each other as “whole” persons to surface. Recognizing the competing needs for care meant that coworkers negotiated the allocation of care on an ongoing basis, involving a continuous struggle to distribute and share limited care resources (e.g., time, attention, emotions).

This study contributes to research on care in organizations in two substantive ways. First, although ethicists of care recognize the care allocation dilemma (Held, Reference Held2006; Tronto, Reference Tronto1993), we extend this to the workplace and argue that previous conceptual research has tended to underestimate competition between caring for coworkers and achieving work objectives (André & Pache, Reference André and Pache2016; Gittell & Douglass, Reference Gittell and Douglass2012; Lawrence & Maitlis, Reference Lawrence and Maitlis2012; Liedtka, Reference Liedtka1996). This study highlights the importance of recognizing this dilemma, and examines coworkers’ struggles to deal with it in practice.

Second, by showing how a specific allocation of care is maintained, this research contributes to understanding how, in the context of coworkers’ relationships, an ethics of care is enacted in organizations (Liedtka, Reference Liedtka1996; Linsley & Slack, Reference Linsley and Slack2013; Moberg, Reference Moberg1997; Vijayasingham, Jogulu, & Allotey, Reference Vijayasingham, Jogulu and Allotey2018; Weiskopf & Willmott, Reference Weiskopf and Willmott2013). While showing how the dilemma of caring for coworkers and maintaining commitment to the work underlies relations at work, we also observe that it may be repressed or upheld. We explain the role of boundary work (Lamont & Molnár, Reference Lamont and Molnár2002; Langley et al., Reference Langley, Lindberg, Mørk, Nicolini, Raviola and Walter2019) in this process by demonstrating how either demarcating or uniting personal and professional selves conditions the possibility of caring for each other in the workplace. We argue that this practice has political implications for determining what and who are worthy of care in the workplace.

In the next sections, we review existing research on the dilemma of care allocation and the morality of coworker relationships. We then describe the methodology of our grounded theory research, and present our findings on the maintenance of care allocations in organizations. Finally, we discuss the contribution of this research to theory and its implications for practice.

The Ethical Dilemma Of Care Allocation And The Morality of Coworker Relationships

While feminist scholars advocate a view of morality as responsibility and care for a particular other (Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1982), they also recognize the dilemma of allocating care and distributing limited resources: “In general, caring will always create moral dilemmas because the needs for care are infinite” (Tronto, Reference Tronto1993: 137). Care is often addressed in the context of ethics and gender, emphasizing relationships and responsibilities emerging from women’s situated experiences (Noddings, Reference Noddings2003; Ruddick, Reference Ruddick1995); yet the different types of care, and the work involved in producing and providing it, touch on issues of policy and politics (Held, Reference Held2006; Nelson, Reference Nelson2001; Tronto, Reference Tronto1993, Reference Tronto2010). In her pathbreaking article, Liedtka (Reference Liedtka1996) positions the issue at the organizational level and initiates a conversation on caring organizations. Following ethicists of care (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson1984; Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1982; Held, Reference Held1993; Tronto, Reference Tronto1993), she considers caring as taking an ethical stance, and raises the question of how to reconcile care (for customers, competitors, shareholders, employees, suppliers) with organizational effectiveness. She highlights the conflict between the traditional view of business, which is impersonal, instrumental, and object-focused, and an ethics of care that requires a focus on the needs and growth of a particular other. This article draws on these authors’ work and examines how care allocation is maintained in practice.

Philosophical and Political Underpinnings of an Ethics of Care

An ethics of care perspective focuses on the relationship between the self and a particular other in a specific context, as a way to attend to the needs of this particular other (Held, Reference Held2006; Lawrence & Maitlis, Reference Lawrence and Maitlis2012; Liedtka, Reference Liedtka1996; Tronto, Reference Tronto1993). This notion of care has been developed in feminist theory in opposition to the Kantian view of ethics that positions morality within the realm of reason and as an abstract and universal exercise (Tronto, Reference Tronto1993). In contrast, care ethicists insist on the role of emotions and feelings, and on the application of morality in situated circumstances (e.g., Ferguson, Reference Ferguson1984; Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1982; Sevenhuijsen, Reference Sevenhuijsen2000; Tronto, Reference Tronto1993). From this perspective, morality is not a blind application of universal ethical rules, but a practice based on personal relationships with particular others in particular situations (Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1982). Thus, ethics is “not a system of principles, but a mode of responsiveness” to relationships and the obligations and responsibilities that they entail for particular others (Cole & Coultrap-McQuin, Reference Cole and Coultrap-McQuin1992: 40; Fisher & Tronto, Reference Fisher, Tronto, Abel and Nelson1990). In short, ethics of care emphasizes interconnectedness, relationships, nurturing, and responsibility towards concrete embodied others (Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1982). The feminist ethics of care also recognizes that “care work” is often precisely the type of work not valued by the market (Nelson, Reference Nelson2001), such as privacy, emotion, and attending to “need” rather than “demand.” While it began as a critique of society’s exploitative neglect or lack of recognition of women’s caregiving (Noddings, Reference Noddings2003), feminist scholars have expanded the domain of the ethics of care to include broader problems of social organization and practice, such as social policy, economic markets, work organizations, and leadership (Gabriel, Reference Gabriel2009; Held, Reference Held2006; Liedtka, Reference Liedtka1996; Sevenhuijsen, Reference Sevenhuijsen2003; Waerness, Reference Waerness, Gordon, Benner and Noddings1996).

The Dilemma of Care Allocation between the Work and the Coworkers

Research on the enactment of an ethics of care in organizations tends to assume that caring for coworkers and caring for organizational outcomes are compatible (Lawrence & Maitlis, Reference Lawrence and Maitlis2012; Liedtka, Reference Liedtka1996). However, coworker relationships focusing explicitly on achieving work outcomes (Ferris, Liden, Munyon, Summers, Basik, & Buckley, Reference Ferris, Liden, Munyon, Summers, Basik and Buckley2009; Moberg & Meyer, Reference Moberg and Meyer1990) lead to a conflict of interest between work and friendship (Bridge & Baxter, Reference Bridge and Baxter1992; Pillemer & Rothbard, Reference Pillemer and Rothbard2018). This focus on work may challenge one’s ability to care for another person. Indeed, attentiveness to others has been emphasized as an initial condition for our ability to care (Tronto, Reference Tronto1993). In contrast, a traditional, Western view of morality at work emphasizes some form of detachment from coworkers’ interests (George, Reference George2014; Sanchez-Burks, Reference Sanchez-Burks2002; Weber, Reference Weber and Parsons1930). This raises the question of whether the prevailing work-centered organizational ethos is compatible with the attentiveness to others’ needs that underlies care. Caring for the work involves being intrinsically committed to one’s work, and may be considered a legitimate ethical practice (Weiskopf & Willmott, Reference Weiskopf and Willmott2013); however, it often consumes any care resources that might be allocated to care for coworkers.

There is ample evidence that caring for the work and caring for coworkers may not always be compatible. While some researchers show that coworkers are able to care for each other (Alacovska & Bissonnette, Reference Alacovska and Bissonnette2019; Gittell & Douglass, Reference Gittell and Douglass2012; Rynes et al., Reference Rynes, Bartunek, Dutton and Margolis2012), others observe that workplaces may be settings for the mutually uncaring treatment of employees (Contu, Reference Contu2008; Jackall, Reference Jackall1988; Linsley & Slack, Reference Linsley and Slack2013; Simpson, Cunha, & Rego, Reference Simpson, Cunha and Rego2015). Conflict is evident (Linehan & O’Brien, Reference Linehan and O’Brien2017) when organizational priorities lead to loss of jobs, such as during restructuring (Gunn, Reference Gunn2011). While leaders are expected to care for their followers, their work role prevents them from attending equally to everyone’s needs (Gabriel, Reference Gabriel2015). More generally, among workers’ various responsibilities at work, caring for coworkers may be sacrificed if they are unable to allocate resources both to fulfilling their work tasks and to caring for their coworkers. Yet this tension is somehow disciplined in such a way that allocations of care are maintained over time in the organization.

This tension echoes the observation that the capitalist pursuit of profit may be antithetical to care and compassion (Fotaki & Prasad, Reference Fotaki and Prasad2015; George, Reference George2014; Wrenn & Waller, Reference Wrenn and Waller2017). Held (Reference Held2006) argues that the issue is not to place economic and care perspectives in opposition, but rather to decide which has priority under what circumstances. Whether explicit or implicit, such decisions have political implications, since they enact what is (more) worthy of care in practice. In this article, we observe empirically how these priorities for care are maintained in practice in the work organization, thus answering Fotaki, Islam, and Antoni’s (Reference Fotaki, Islam and Antoni2019: 10) call to “begin the slow work of tracing care through its diverse manifestations in organisational practices and contexts.” Hence, we look at how care for coworkers may be enacted in the work organization, and unveil how boundary work is used as a political instrument to enact in practice what has priority for care in the workplace.

Boundaries Between Spheres of Care

Previous research shows that morality in the workplace differs from morality in other areas of life (Belmi & Pfeffer, Reference Belmi and Pfeffer2015; Jackall, Reference Jackall1988; Molinsky, Grant, & Margolis, Reference Molinsky, Grant and Margolis2012), explaining that issues that would be recognized as ethical outside the work context may not be recognized as such within the organization (Palazzo, Krings, & Hoffrage, Reference Palazzo, Krings and Hoffrage2012; Parmar, Reference Parmar2014; Sonenshein, Reference Sonenshein2007). Regarding care allocation, there is evidence that the personal–professional divide plays a role in recognizing this dilemma. Indeed, ethicists of care denounce confining care within the narrow boundaries of the private sphere (Tronto, Reference Tronto1993).

An eclectic ethics of care, combining feminist and political geography perspectives, challenges the conventional distinction between the public and the private nonwork space associated with emotion, care, and welfare, that informs the morals of interpersonal relationships (Brown & Staeheli, Reference Brown and Staeheli2003). From this perspective, women’s experiences in the private sphere are taken as a “normative model for behavior” in the public sphere, as women’s “capacities for love and care for others come to be seen as a model to be emulated by others, and as a potential basis for public morality” (Mottier, Reference Mottier2004: 330). Caring involves “feeling with” the other (Liedtka, Reference Liedtka1996) and being responsive to their needs, emotions, and desires. In contrast, being “professional” is often taken to mean focusing on the task and setting aside personal issues, limiting the level of affect at work (Sanchez-Burks, Reference Sanchez-Burks2002: 927). It is argued that this personal–professional divide that pervades the workplace conflicts with the ethics of care. For instance, research demonstrates that the workplace is a symbolic space where maternal practices that are praised outside the professional sphere, such as breastfeeding, are actively repudiated (Gatrell, Reference Gatrell2019).

In summary, the divide between the personal and professional spheres seems to be critically important for understanding the possibility for care in the workplace. Focusing on the dilemma of care allocation, we ask: how do employees deal with the care allocation dilemma, and how might specific care allocations be maintained in organizations?

RESEARCH METHOD

Based on a broad interest in understanding what constitute “good” relationships at work, a grounded theory approach was adopted for this study (Glaser & Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967; Walsh, Holton, Bailyn, Fernandez, Levina, & Glaser, Reference Walsh, Holton, Bailyn, Fernandez, Levina and Glaser2015). Typically of an open-ended and inductive design, initial rounds of data collection led to refinement of our theoretical interest. In this section, we describe this “research journey” (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006), which led us to build theory on how employees deal with the ethical dilemma of care allocation, and how they maintain a specific care allocation in their organization. We first explain the theoretical sampling that drove our data collection.

Theoretical Sampling

We initially aimed to identify organizational contexts suited to understanding the nature of relationships at work by choosing two diverse settings to observe how the care allocation dilemma operated in practice. We then proceeded iteratively between fieldwork and data collection, making sense of what we were observing and returning to the field to collect more data to explore or confirm our emergent theorization.

The first research setting, COMMS, a communications agency in France, was chosen because discussion with a senior manager, the gatekeeper, suggested that it would be an exemplary case of “nice” (Natasha, Consulting) and overtly nonconflictual relationships in the workplace. However, initial data collection and analysis at COMMS, including observing and interviewing employees, revealed a much more complex picture. While coworkers maintained polite and friendly relations with each other, they did so only when this was conducive to organizational performance. We were surprised to discover that caring for each other was only implicitly positioned as secondary to their work, overriding any explicit recognition of the dilemma between caring for the work and for coworkers. This discovery led us to seek access to a contrasting work setting where matters of care would be explicitly at the forefront so that we could refine our initial insights on the dilemma of care allocation in the workplace. The first author was granted access to SERV, a child protection agency, where we expected care to be more explicit, given the centrality of care in their everyday endeavors.

After starting our data collection at SERV, it quickly appeared that the allocation of care was not straightforward. As expected, there was much more awareness of coworkers’ needs for care, but personal and affective commitment to alleviating the suffering of children in pain was so intense that it left few emotional, cognitive, or temporal resources to attend to coworkers’ concerns, although they did their best to respond to these needs under the circumstances. Consulting the literature on ethics of care (Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1982; Held, Reference Held2006; Tronto, Reference Tronto1993) allowed us to make better sense of this observation. Caring for people is a duty that we all encounter in our everyday lives as parents, children, siblings, friends, and coworkers; and this multiplicity of caring needs creates the dilemma of care allocation. We observed that being in a caring profession may be a double-edged sword: while it provides the professional skills necessary for caring, occupations requiring the continuous exercise of care and compassion, such as social work and healthcare, often exhaust individuals’ capacity to care (e.g., Adams, Boscarino, & Figley, Reference Adams, Boscarino and Figley2006; Figley, Reference Figley2002; Hooper, Craig, Janvrin, Wetsel, & Reimels, Reference Hooper, Craig, Janvrin, Wetsel and Reimels2010). When emotional and cognitive resources are mobilized as part of the everyday tasks of care, it becomes even harder to offer care outside of work tasks (Figley, Reference Figley2002).

Hence, COMMS and SERV displayed different ways of dealing with the care allocation dilemma that were actively maintained. This constrast allowed theorizing on how specific care allocations are maintained in organizations.

Research Settings: COMMS and SERV

COMMS is a French subsidiary of a multinational, full-service communications agency. Three units were studied: Consulting, Public Relations, and Advertising. Consulting, comprising five to seven employees during the observation, advised clients on their branding and communications strategies. They acquired new contracts and conducted consulting projects, from small-scale workshops with a board of directors on a communications strategy, to much larger projects, such as co-designing the communications strategy of a multinational corporation. Public Relations, comprising over ten employees, helped clients manage their public image. This required connecting with journalists, almost exclusively over the phone, and writing content for media releases. Finally, the Advertising department was where publicity ideas were elaborated and sold to clients for their communications campaigns. It comprised around one hundred employees across strategic planning, creativity, and client relations. During the observation, the communications sector as a whole was being transformed, threatening the traditional advertising business model. As a result, all units experienced significant commercial pressures, with fluctuation in size and high staff turnover. The various units regularly moved around or out of the building when their contracts were extended or terminated.

SERV was a local unit of the French national child protection service (Aide sociale à l’enfance) run by a local authority (French “département”). Children were taken into care by SERV based on a judge’s decision. The team of ten care workers, including the head, six social workers, and three secretaries, were responsible for organizing foster and care plans following a judge’s order, and for working with various partners (foster families, hosting venues, parents, police, health services, etc.) for the well-being of the child. Most employees had worked there for years (between three and thirty years), apart from an intern who had only spent six months there. Also, during the observation, two employees left on maternity leave and were replaced by employees on short-term contracts. Located in a small town in a rural area, SERV covered a large geographical area, and social workers had to travel regularly to visit children, foster families, and hosting venues.

Data Collected: Ethnographic Observations and Interviews

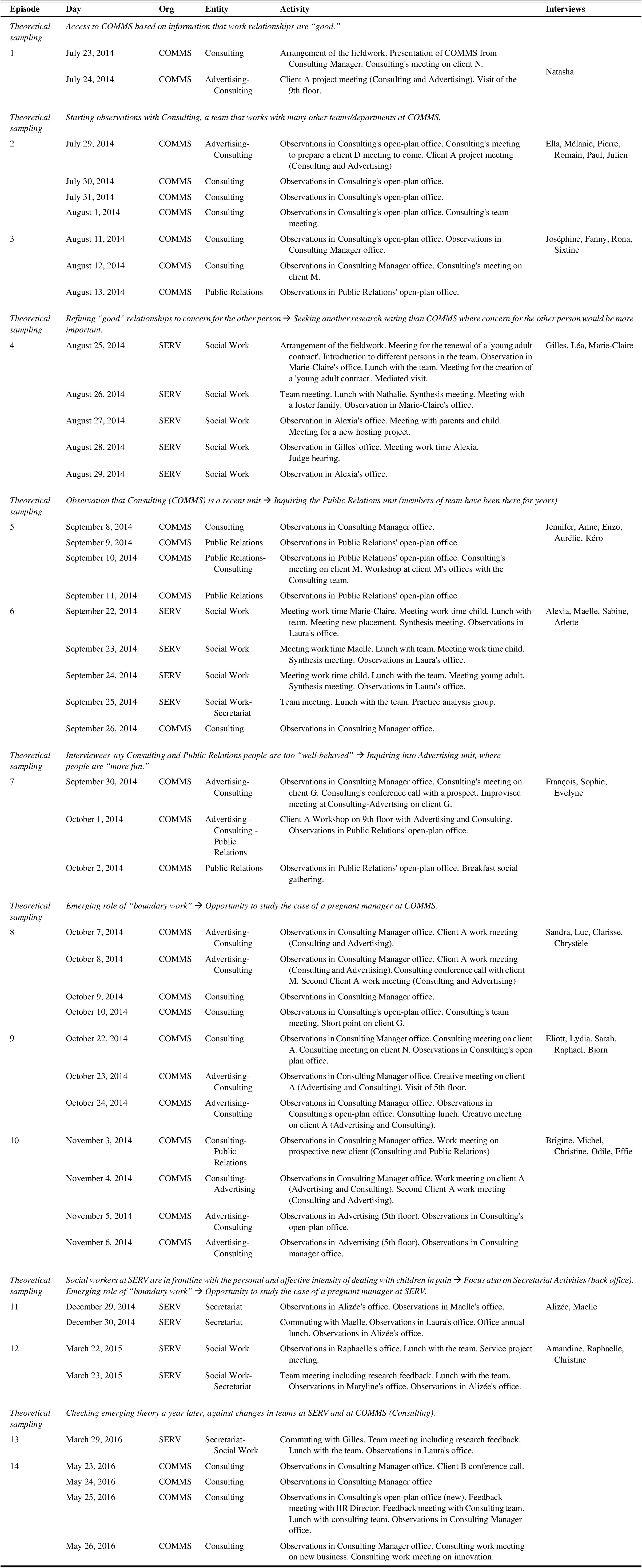

The data collection combined ethnographic observation with interviews, covering a broad range of situations. As shown in Table 1, which summarizes our data collection process, the researcher (first author) spent time in different units at both COMMS and SERV, and observed meetings, office work, spontaneous work interactions, morning greetings, lunchtime get-togethers, etc. Observations were recorded in a field diary, yielding more than 170 pages of single-spaced field notes. Also, dozens of documents were collected (see Appendix A), including emails, internal documents, client presentations (for COMMS), and human resource management memos (for SERV). Formal, open-ended interviews were conducted to better understand coworkers’ perspectives on everyday practices, norms, and beliefs about relating to each other at work. Interview appointments were made during the observations. At COMMS, thirty-three employees were interviewed, although one interview was excluded because the recording was inaudible. These included all eight employees in Consulting, eight out of eleven in Public Relations, six out of more than one hundred in Advertising, and ten respondents from other entities working directly with Consulting. Attention was given to interviewing employees of different gender, age, years of work experience, and levels of responsibility (managers, top managers, seniors, juniors, interns). At SERV, all thirteen employees of the local branch were interviewed (including ten respondents from the Social Work unit and three from the Secretariat unit).

Table 1: Data Collection Process

All interviews followed a similar structure (see interview guide in Appendix B), starting with a short introduction, and then expanding in an open manner to allow the interviewees to explore any topics that appeared relevant to them. Questioning revolved around a central, guiding question: “According to you, what do you think is the appropriate way to behave with each other at work?” The interviews were also informed by the observations: interviewees raised examples from situations that they knew the researcher had observed, and the researcher invited comments on situations involving the interviewees. Table 2 summarizes the data collected.

Table 2: Data Collected

Data Analysis: Iterative Coding and Confrontation with Existing Knowledge

As is typical of grounded theory, data analysis was an inherent part of data collection. Data analysis and data collection were intertwined through iterative coding, which is the constant comparison of data and emerging theory (Birks, Fernandez, Levina, & Nasirin, Reference Birks, Fernandez, Levina and Nasirin2013). Following grounded theory techniques for systematic coding and constant comparison (Birks et al., Reference Birks, Fernandez, Levina and Nasirin2013; Holton, Reference Holton, Bryant and Charmaz2007), the data were first open-coded by the first author. This first level of coding entailed rereading the material and systematically labelling chunks of text (or images) according to the content of the material. This endeavored to capture the nature of relationships at work, including care for coworkers, how employees qualified the relationships, and contextual attributes (individual, organizational, environmental) that might play a role in shaping coworker relationships. These codes included “attention-availability,” “fairness,” “relational endeavor,” “respect,” “helping,” “self-interest,” “having fun,” “being well,” “arrival-adapting,” “food sharing,” “work skills,” “personal issues at work,” “sharing personal life,” “information exchange,” “conflict,” “role clients,” “comparing workplaces,” and “performing-producing.” After coding around 30 percent of the material, the codes were reviewed to check for overlaps and to merge them, or to add nuances and develop new codes as needed. This process ultimately yielded ninety-two codes from the observational data and eighty-eight from the interview data. Memos were written systematically to keep track of the meaning of each code and to ensure consistency. Appendix C shows an example of a memo for the code “personal issues at work.”

Iteration between data and literature, enriched by discussions between the authors, led to the emergence of the themes of ethics of care and the dilemma of care allocation (Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1982; Held, Reference Held2006; Liedtka, Reference Liedtka1996; Tronto, Reference Tronto1993). In trying to understand the nature of relationships, care appeared to be a useful concept to define what we were observing. Moreover, the literature on ethics of care enlightened the contrast we observed between COMMS and SERV, allowing us to identify the cases as different instantiations of the dilemma of care allocation. This dilemma was explicit at SERV, where employees directly raised the issue of facing agonizing choices of caring for either the work or coworkers. This dilemma was largely implicit at COMMS, but briefly resurfaced despite efforts to conceal it, such as when considering the special needs of pregnant employees, as discussed next.

In attempting to explain the contrast between SERV and COMMS, our analysis indicated that COMMS employees differentiated between what COMMS respondents called the “personal,” i.e., personal aspects of their lives that could be exposed in the workplace, and the “personal-personal,” i.e., personal aspects that should not be exposed in the workplace. This resonated with feminist critique of the artificial boundary between the personal and public spheres (Tronto, Reference Tronto1993) that confines care to the personal sphere, as well as the empirical argument that care requires consideration of the wholeness of the person (Dutton, Worline, Frost, & Lilius, Reference Dutton, Worline, Frost and Lilius2006; Lilius, Worline, Dutton, Kanov, & Maitlis, Reference Lilius, Worline, Dutton, Kanov and Maitlis2011).

We thus focused our analysis on how COMMS employees worked to create and maintain this invisible symbolic boundary between professional and personal selves, which in turn delimited the acceptable allocation of care for coworkers as opposed to for work. To do so, we consulted the boundary work literature (e.g., Hobson-West, Reference Hobson-West2012; Kantola & Kuusela, Reference Kantola and Kuusela2019; Lamont & Molnár, Reference Lamont and Molnár2002; Langley et al., Reference Langley, Lindberg, Mørk, Nicolini, Raviola and Walter2019; Peifer, Reference Peifer2015) and found great resonance with our data. Boundary work is defined as the “purposeful individual and collective effort to influence the social, symbolic, material or temporal boundaries, demarcations and distinctions affecting groups, occupations and organizations” (Langley et al., Reference Langley, Lindberg, Mørk, Nicolini, Raviola and Walter2019: 3–4). The analysis revealed a marked separation between “personal” and “professional,” which was constantly but implicitly enacted in practice at COMMS, while explicitly resisted at SERV, where employees made a conscious effort to consider coworkers as whole persons. We then wrote a theorized storyline for each case (Golden-Biddle & Locke, Reference Golden-Biddle and Locke2007), offering a narrative of organizational members’ actions and interpretations of what happened. This was followed by theoretical discussions explaining how specific allocations of care between work and coworkers’ needs are maintained in work organizations.

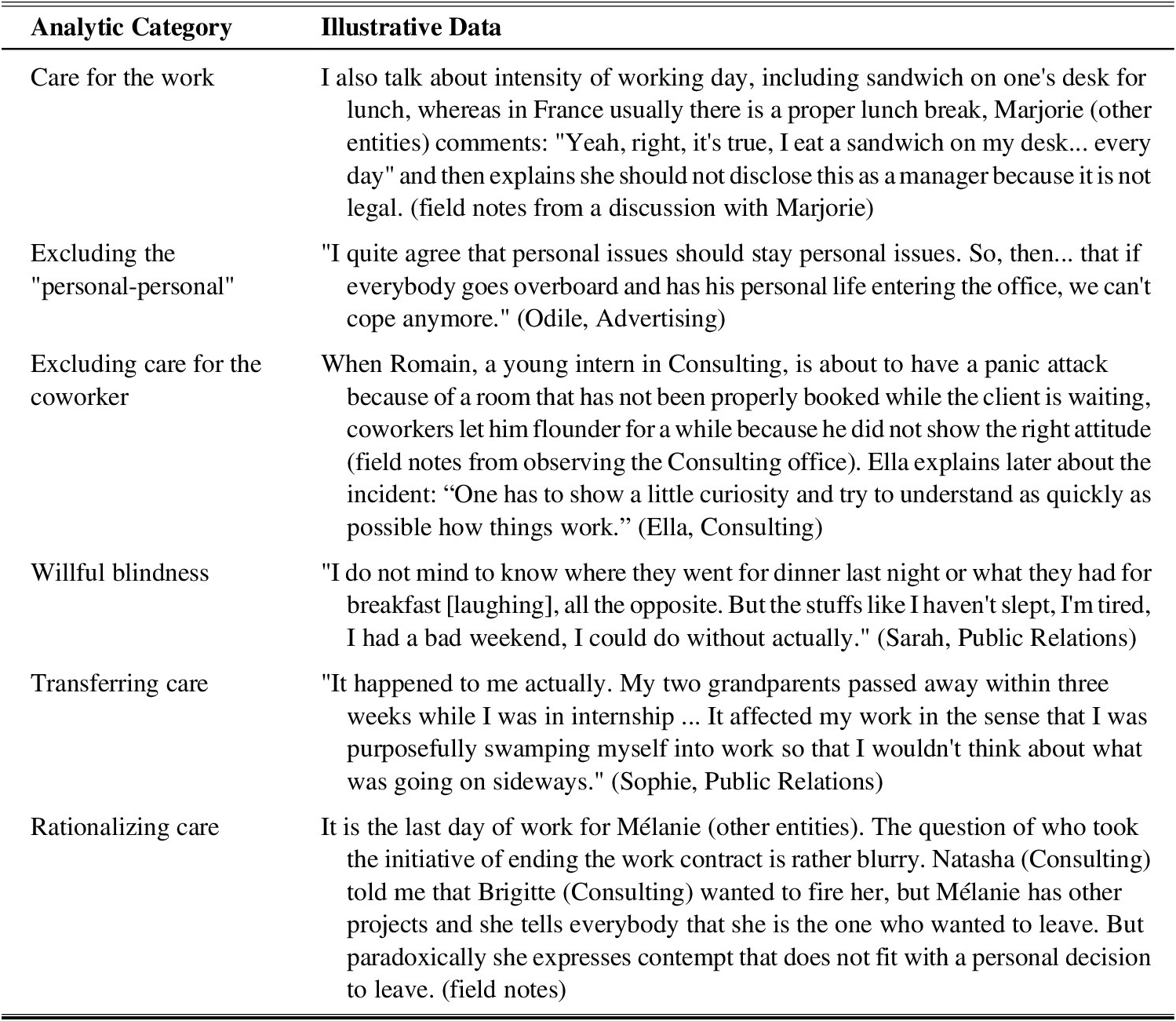

At COMMS, we found that the care allocation largely concerned work, and that this exclusion of coworkers from care was supported by a strong distinction between elements of workers’ lives that were or were not relevant to work. We also coded instances of breakdowns of this care allocation, where needs to care for coworkers emerged, threatening to destabilize the unique concern for work. Comparing care across such breakdown situations revealed a pattern of responses. We identified three general practices: willful blindness, transferring care, and rationalizing care or its absence. Table 3 illustrates these concepts.

Table 3: Illustrative Data on Emerging Themes at COMMS

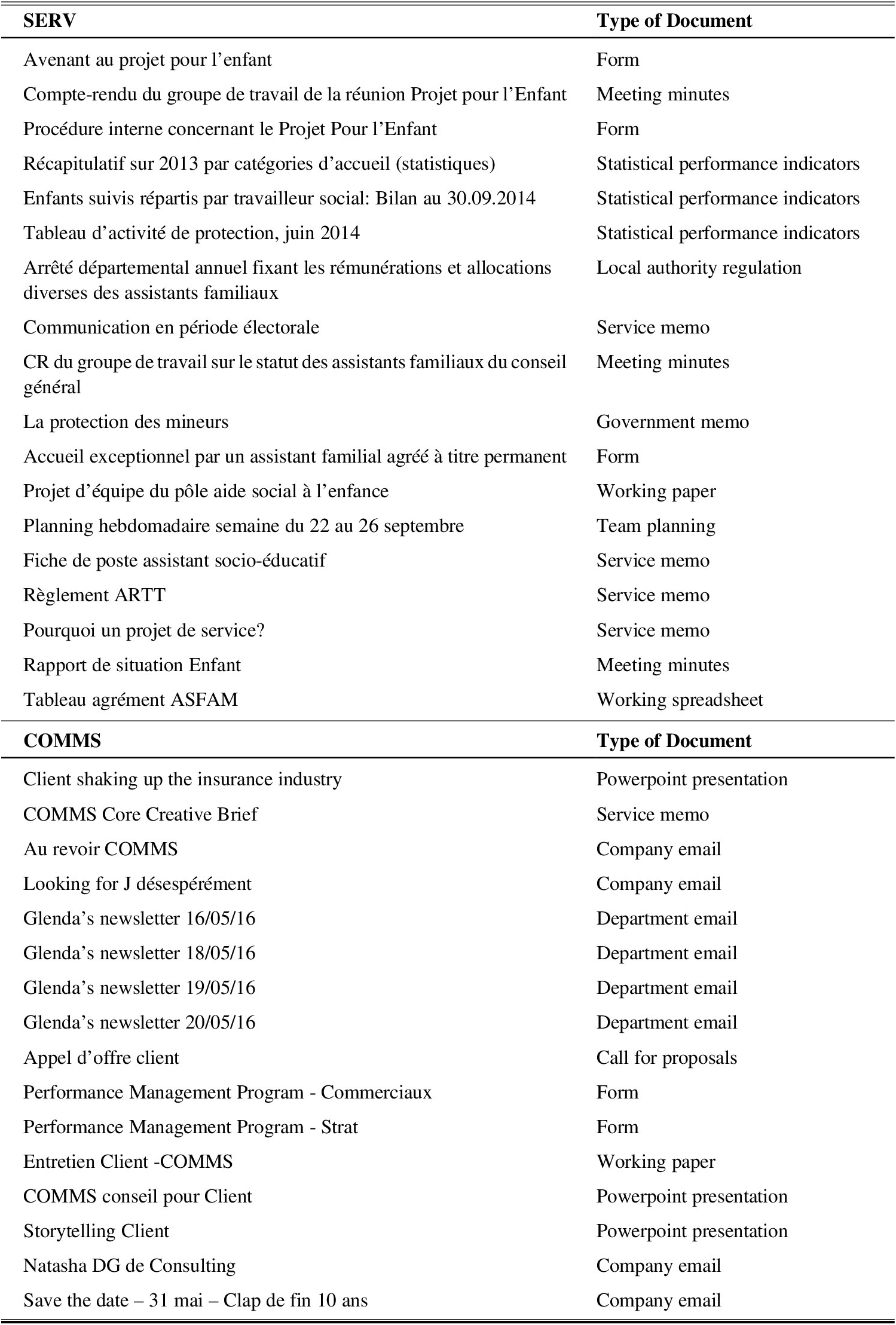

At SERV, our findings indicated that the care allocation included both work and coworkers. We thus focused our analysis on understanding how care for coworkers was sustained, and identified the role of boundary work, consisting of the symbolic joining of personal and professional selves of workers, thus constructing them as whole persons. We also coded instances of breakdowns in the allocation of care and where care for coworkers was questioned. The analysis revealed three practices resisting these breakdowns: asserting care, inverting care, and problematizing care. Table 4 illustrates these concepts.

Table 4: Illustrative Data on Emerging Themes at SERV

Finally, we returned to the field a year later (March–May 2016) to share our early research findings with the research participants, and to confirm that our observations were still relevant, given employee turnover (around 20 percent at SERV and 30 percent at COMMS). We present our findings for each research setting in the next sections.

COMMS: MAINTAINING CARE FOR THE WORK

At COMMS, our findings reveal that care for the work was clearly prioritized over care for coworkers. Despite outwardly friendly and jovial relationships among coworkers, care for coworkers was only provided to the extent that it served work purposes. The vignette below illustrates the day-to-day maintenance of the boundary of care in a typical day for Natasha, a manager in the COMMS Consulting unit.

Natasha arrives at 9:15 when offices remain almost empty. Before arriving, she stops at a grocery shop nearby to buy fresh orange juice and biscuits to share with the team she manages, whom she calls “the kids.” Natasha explains that these little gifts enhance motivation for the job.

Settled at her desk, Natasha exults: “Yes! We racked up the numbers for October!” She has to make sure the team is bringing in enough money to sustain itself, otherwise she will not be able to keep employing several of “the kids.” She is worried for her team because she will be on maternity leave in a few weeks and could not find anybody good enough to replace her while she is gone. Sandra, from Public Relations, will take over for some specific projects, but there will be no specific person covering her role. She tried a temporary work agency who sent a woman to support her, but after a few weeks she dismissed her. This decision was hard. Natasha felt she was being the “bad guy.” But it was not working out, so she has no doubt that she made the right decision. Business is business.

For now, Natasha is meeting with Bjorn from Advertising about the hot topic of the moment: the mission for InC, an insurance company. They are excited about the idea to revolutionize the insurance business. Bjorn and Natasha decide to call on one of the “big shots” at InC to check on an idea: “We would like to know whether we are two dreaming lunatics.” Their interlocutor welcomes the idea quite warmly, laughing at it, but he dismisses it immediately because it would conflict with insurance regulation. Natasha and Bjorn do not lose their light spirit and laugh: “There’s a bit of work but we’re gonna get there.” Back to square one.

Afternoon. Natasha and Bjorn meet briefly with Brigitte, her boss, who is overseeing the InC mission. Brigitte left them with a huge pile of work to do before tomorrow’s meeting.

Evening. Natasha and Bjorn are still working in Natasha’s office on the InC mission, now joined by Pierre, senior consultant, and Eliot, a young intern, from Natasha’s team (Consulting). Pierre is working on a ninety-page book for another client that is due tomorrow. He is here because he “shares” Eliot, who is working on both projects. He already knows that he will work until 5am to finish the book, and cynically comments, “That’s how we make profit.” Natasha does not react to that, but she thinks that Pierre is working that late because he did not organize well enough, more evidence that he is not ready for promotion. In addition, “nocturnals” [night-time work] are part of the job. She is, herself, quite frustrated to have to work late because she has family responsibilities, but she does not mention it and tries to keep a light spirit. When Eliot tries to help Bjorn by coming up with ideas to write on the presentation slides, Natasha laughs: “The man who shot sentences faster than a speeding bullet.” Bjorn laughs as well: “True that! Keep it easy, less is more!”

It’s quiet for a while. Then Natasha speaks up: “I can feel that, the InC meeting tomorrow, there will be blood…[and] at breakfast time on top of it…Eww!” Everybody laughs.

Allocation of Care at COMMS: Prioritizing Care for the Work

At COMMS, employees focused on providing creative, efficient, and timely communication services. People buzzed around, creating spontaneous meetings at any hour, forgetting about the time, focusing on tasks due the next day and sometimes in the next hour. Every situation must be productive, sometimes indirectly, like learning or networking in preparation for future projects, but the ultimate objective of every action was to provide high-quality work.

When confronted with a difficult situation, such as urgent work on a troublesome project, Natasha cared for her team members simply to help them remain productive, which would potentially lead to success. If a team member had no potential to contribute to the task or to the organizational goals, then Natasha would not care for them. This had been the case with the temporary worker who had started working with Natasha in anticipation of replacing her during her maternity leave, but whom she had decided to dismiss before taking leave. The question of the impact of her decisions on her coworkers’ personal lives was irrelevant and seemed not to enter into her considerations.

As a result, helping each other was part of the job and was not directed at caring for the person as an end in itself. If coworkers were not deemed to have the “potential” to contribute, they would not receive care. In the introductory vignette, Natasha does not empathize with Pierre for staying at work until 5am because she believes he could have organized his time better to deliver on his tasks on time, as she explained in her interview. COMMS managers and coworkers allocated care to each other only to the extent that it served the work purpose.

Maintaining an Allocation of Care Centered on Work: Keeping a Professional Distance

Looking across our observations, we suggest that the allocation of care at COMMS described above was maintained through ongoing boundary work that prevented the care allocation dilemma from surfacing. Central to this boundary work was maintenance of a clear distinction between the workers’ personal and professional selves, as described in more detail below. Figure 1 illustrates this general process.

Figure 1: Maintaining the Allocation of Care at COMMS

Maintaining a clear boundary between their personal and professional selves enabled COMMS employees to keep a professional distance and overlook potential needs to care for coworkers, which only surfaced in extreme situations (see next section). They distinguished between the parts of their personal lives that they revealed easily at work, and their “personal-personal” lives that they would never allow to surface in the workplace. Implicitly, they seemed to follow clear norms about which aspects to reveal, and which ones to be silent about. They talked about their latest Ikea purchases, but only as a means to illustrate consumers’ approach to buying furniture. They talked about their own bank accounts when trying to imagine future banking services. However, they remained notably silent about their personal-personal lives, as Sarah (Public Relations) put it, such as their health, personal grief, or family matters. The personal-personal life was irrelevant to work life; hence, it was not evoked, especially if it related to difficult or negative events that might take up time and energy during interactions at work. Kero (Public Relations) emphasised that “even when one has issues at home, they should be left at home then, and when you arrive in the agency it is joyful and cheerful.” Fanny (Public Relations) explained that a former colleague was always complaining about her romantic life. Her coworkers had asked her to stop doing so, explaining to her that it was inappropriate because it slowed down the teamwork. The problem with employees exposing their personal issues was that it encumbered the work life with elements that did not advance or even hindered their work. A harmonious working life required avoiding encumbering coworkers with one’s own personal difficulties. COMMS employees expected each other to draw a boundary between what should be exposed and what should not, what should be made visible and what should remain invisible.

This everyday boundary work to segment what was relevant or irrelevant to work allowed them to shield themselves from noticing coworkers’ needs for care, and thereby from any conflict between caring for the work and for coworkers. Conflict was avoided by keeping a “professional distance” (Odile, Advertising) from each other. For Sixtine (Advertising), it was a matter of coping: “I think that this is a survival reflex even; you can’t be troubled by each other’s problems, otherwise you won’t get through.”

In summary, enacting a strong boundary between aspects of the person that were and were not relevant to performing the work allowed workers to avoid dealing with care for coworkers, and the potential dilemma between allocating care to the work or to coworkers.

Maintenance Work to Resist Breakdowns in the Allocation of Care

Despite everyday efforts to conceal the personal-personal from the workplace, we observed micro-breakdowns when such aspects surfaced that confronted employees with a need to care for the person as a person. While these breakdowns occurred regularly, we identified three types of maintenance work in which COMMS employees engaged to contain such overflows of need for care and to restore the allocation of care: willful blindness to caring needs, transferring care from the coworker to the work, and rationalizing the care dilemma or its absence. Figure 2 illustrates this maintenance work.

Figure 2: Resisting Breakdowns in the Allocation of Care at COMMS

Willful Blindness to Caring Needs

When pertinent personal issues demanding care permeated the professional life boundary but resisted being transferred to care for the organization, we observed that coworkers exercised what we term willful blindness to caring needs. Despite efforts to supress the personal-personal in everyday work life, some personal matters, including bodily needs such as illness or pregnancy, transcended the personal boundary and tended to impinge on the work. Hence, even if bodily needs were seen as either irrelevant to or limiting work, they could not always be successfully excluded from the workers’ presence in the organization.

Natasha’s pregnancy exemplified how human bodies disturbed the boundary between caring for the work and the coworker. Natasha, a manager in Consulting, was pregnant during the observation; yet nobody, including herself, ever talked about it. Even though her pregnancy was becoming increasingly visible, her colleagues were purposefully blind to it. For instance, no arrangements for her maternity leave were discussed. Ten days before her actual leaving, her team members were visibly anxious but would still not talk about it. The following excerpt from our field notes describes an event that revealed how Natasha herself sustained willful blindness to her own need for care:

Natasha is supposed to see a midwife at 4:45pm for the monitoring of her pregnancy. She is a bit worried that she might be late because an important client meeting that she attends might last longer than initially planned…

In the end, the meeting ends after 5pm. Natasha misses her pregnancy monitoring appointment. But she doesn’t seem angry when they finally come back from the meeting. They debrief about it quickly then with Brigitte, her boss, who got back in the meantime. Natasha seems happy about the meeting; they explain what worked well and what raised more questions or resistance. Natasha tells Brigitte that she had to miss her appointment. Brigitte doesn’t react; she looks at me though.

Later, Natasha tells me that she was annoyed about missing her appointment. She has her second ultrasound a week later so it should be OK. She would rather have been reassured that everything was alright though with her unborn baby.

Natasha did not actively “hide” her pregnancy, but she did not allow her pregnancy to be visible at work, nor place constraints on it, for instance, by attending medical appointments. One awkward moment was when Natasha told her boss, Brigitte that she had missed her medical appointment because of a late meeting. Brigitte was ill at ease because this might not look good while the researcher was observing the exchange. Suddenly, the pregnancy was made visible, and competing needs to care for the work and the coworker re-emerged.

Transferring Care from the Coworker to the Work

When faced with the need to care for a coworker, we observed that COMMS employees sought to transform the need for care for coworkers into care for the work, which we call transferring care. The vignette below illustrates how a young intern, a vulnerable temporary coworker, signalled the need to be taken care of independently of his work, and how care was transferred back to the work.

Eliot started his six-month internship a few weeks ago and is struggling with a project involving several high-level managers in the company. The project participants are not collaborating with him as much as they are supposed to. This situation drains his energy and makes him feel scared that he may not be able to fix it. One late night, he ends up in Natasha’s office, his manager, and they have a discussion about this experience. He is obviously upset and Natasha displays a benevolent attitude toward him. However, she does not verbally express empathy for Eliot’s suffering. Instead, she brightly turns the problem into a positive by stating that “there is an opportunity for reflection,” and they start elaborating how to improve project management at COMMS in general.

In this vignette, Natasha does not take care of Eliot’s suffering as such. Instead, she undermines his suffering and encourages him to treat this painful experience of failing at a work task as an opportunity to improve the organization’s functioning overall. Eliot will thus turn things around by getting ahead of the situation, and by showing competency and contribution to the organization through an improved understanding of COMMS’ project management processes. Natasha skillfully transforms Eliot’s personal need for care into care for the organization.

Rationalizing the Care Dilemma or its Absence

Sometimes, neither the care could be transferred nor the personal-personal ignored, and COMMS workers faced the dilemma of care allocation between the work and the coworker. In such instances, we observed a practice of rationalizing care, which emerged as a last resort to restore the allocation of care, as logical reasoning led coworkers to believe that it was impossible to provide care. Michel, a senior manager in Advertising, explained that he regretted being unable to maintain the employment of somebody who had been on sick leave for a while (due to a burnout) and had then returned to work but with a lower level of performance:

And when the person comes back then … her position is not available anymore, then she comes back, well it is complicated to take the same thing back and all, and also at that level it is complicated afterward for us to find a position and so. Well, what we could allow ourselves to do with Kim [who had multiple sclerosis], for example, we can’t do with everybody, that is to say having somebody that you accompany again so that she really takes back her confidence in herself, her job and all, at a high level. Well, we can’t afford it, then in the end we let her go.

Taking the decision to dismiss an unproductive employee, a common occurrence leading to high turnover at COMMS, was a clear breach of care for the person. When “tough” decisions had to be taken involving sacrificing someone’s wellbeing, COMMS employees resolved the issue by asserting that there was no possible alternative. As a last resort, COMMS employees again constructed the situation as one in which there was no dilemma, with no choice between alternative possibilities, and behavior constrained by objective facts.

SERV: MAINTAINING CARE FOR THE COWORKER ALONG WITH CARE FOR THE WORK

In contrast, at SERV, our findings suggest that care for the work and for the coworker were seen as equivalent and competing, rather than the latter being subordinated to the former. Caring for coworkers required mobilizing resources such as time, focus, energy, and emotions that could otherwise have been used for work; thus, while aiming to care also for coworkers, SERV employees struggled with competing caring needs. Rather than supressing the dilemma of care allocation, SERV employees acknowledged and confronted it on a daily basis. The vignette below illustrates the struggle to maintain this allocation of care in a typical day for Maelle, a social worker at SERV.

December morning. Maelle arrives at the office with a sore neck. Yesterday she had to drive 60km on snow-covered roads for a home visit in a small town. It took her two and a half hours. She realized she should not have gone considering the weather and being four months pregnant, but at the time she felt that she had to do it.

This morning she has no outside appointments, but a 9 o’clock “work time” meeting with Gilles, the head of service, and Nathalie, the psychologist. Arlette, the secretary in charge of Maelle’s administrative cases, is not there yet. Due to a packed schedule with appointments, they cannot wait for her. Arlette enters the room at 9:30 and asks, “You started already? I’ve been here since 8:50.” There has been an obvious miscommunication. Nobody had tried to find her in the secretaries’ office next door. Arlette is visibly offended, but she does not complain, and joins the work meeting right away. The group continues to review “Maelle’s situations.”

The next “situation” involves a child who has accused her foster family of threatening her with a knife. The group strongly suspects this is an attempt by the child’s mother to discredit the foster family. Maelle is uneasy, as this situation necessitates a confrontation with the mother to find out the truth. Gilles offers to step in, but with a warning directed to Maelle: “I’m going to be a bit hard on her. No need to worry about it.” And teasing Maelle’s softness: “No need to comfort her afterwards.”

After the meeting, Maelle goes back to her office to try to catch up on overdue reports. But the phone rings and rings. Maelle then makes a call out to [foster family] about the problem with the eight-year-old girl caught in a conflict between two foster families, with her biological mother taking the side of one of the families. The confrontation is difficult, and Maelle voices her reluctance to call the foster mother: “I don’t want to call her.”

Afternoon. Maelle travels to another SERV office and shares the ride with Marie-Claire, a colleague who has an appointment near the same location. Colleagues have been noticing for some time that Marie-Claire has been unwell and out of touch. It turns out that Marie-Claire is going through a divorce. Maelle does not know how to react to this. She feels guilty for not taking the time to ask how Marie-Claire is doing, but she has so many cases to deal with right now.

Allocation of Care at SERV: Acknowledging Competing Needs for Care

In the vignette above, describing a typical work day, Maelle is physically and emotionally weighed down by competing responsibilities. She would like to care for her colleagues, but is aware that caring for coworkers requires resources that might otherwise be used for the sacred mission of caring for children in pain. Indeed, members of SERV were absorbed by their mission to care for the children for whom they were responsible as part of their job: “their life is at stake, it is about their future” (Maelle, Social Work). The following excerpt from an interview illustrates the strain they felt when they could not seem to find the right solution for a particular child. Christine recalled a situation where she had to pick up a child and find an emergency fostering solution, as he had been thrown out of the foster family after being expelled from his school:

There are situations like that that come back in our heads all night, but we have to … Here it is, a kid like that, nobody wants him. We tell ourselves, well, what do we do with him? We’re not gonna leave him roofless; he’s sixteen, we’re not gonna leave him… without anything. Eh, that’s hard still at times and not finding a solution for him. Telling oneself that nobody wants him then. That’s the harsh reality. There are times “woohoo!” during the night to tell oneself but what is he doing there? How can he still be standing? So why hasn’t he committed suicide yet [laughs]? No but.… The kids! How do they manage to keep standing? (Christine, Social Work)

At the same time, SERV employees also believed in the importance of caring for coworkers. Maelle (Social Work) said that she felt “the duty to ask the other what is going on and then, well, to see how I can help her.” But when struggling to take care of children experiencing psychic pain, they acknowledged that “it is not easy to hold out a hand to the other colleague” (Alexia, Social Work). Yet, between various appointments and stressful tasks, they were not always considerate toward each other, at least not superficially. For instance, they did not always greet each other properly, even though they apologized for it. The introductory vignette illustrates how Arlette’s coworkers had forgotten that she was supposed to join the meeting, failed to stop at her office for morning greetings, and simply started without her, which she felt resentful about as she explained in the interview.

However, the objective of caring for each other was put to the test in everyday work situations. The following excerpt from our field notes describes observations during a meeting when SERV employees were negotiating who would take care of the new intern:

Gilles (Social Work) asks: “No, but who takes her Monday morning? Who is there on Monday morning? Christine?” Christine (Social Work) answers: “We are all here.” Understanding this is not a “yes,” Gilles argues that the intern does not have to be on somebody’s shoulder in particular: “She will go from one office to another, navigating.” But they react to this that it is not the right way to do it.

The issue of tutoring the intern was a problem of workload allocation. Nobody wanted to shoulder the overload. However, they were also concerned about taking care of the intern, who was coming to learn the job and needed proper tutoring. In the end, Christine did so.

Allocating Care to both the Work and the Coworker: The Worker as a Whole Person

Our findings suggest that maintaining a more balanced, though conflictual, allocation of care at SERV, as described above, also involved boundary work that prevented rather than promoted the demarcation of a person’s individual needs from those of her professional self. Rather than distinguishing between personal and professional aspects, allocating care to the coworker was made possible through consideration of the worker as a whole person. This recognition led to awareness of the entanglement between personal and professional lives, and resulted in a feeling of responsibility for colleagues as particular others, hence allowing care to be maintained for both coworkers and the work. Figure 3 illustrates this process.

Figure 3: Maintaining the Allocation of Care at SERV

Overall, SERV’s employees strongly segmented their work and home lives, having specific working hours outside of which they did not work, and avoiding taking any work home. However, this boundary did not translate into a demarcation between their personal and professional selves. For instance, Marie-Claire (Social Work) stressed that “I am a person and I can’t split myself… well, when I am at work I carry who I am and with my story.” Moreover, when scheduling a meeting with the whole team for Amandine’s end of internship presentation, they considered each other’s family situation to decide on a suitable slot:

Gilles (Social Work) proposes a meeting early in the day because they have another meeting at 11am, so Alizée (Secretariat) proposes 8:30 or 9am, and several people reply immediately”9!” and laugh about it, conscious that they are not able to commit to start a meeting at 8:30am. Gilles tries to insist “I can be there at 8:30,” but concedes “but I don’t have young children.”

Knowledge of employees’ personal lives was acknowledged not only in everyday organizing, but also in recognizing particular strengths and weaknesses in relation to the job. When Maelle (Social Work) had to place some young children who were about the same age as her own, her colleagues checked on her afterwards to see how she was doing because of the emotional strain they expected her to experience. In this case, she was not doing so well. A couple of colleagues stayed late to talk her through the situation and help her process it. Of course, this was done on their own time as the work day had already finished.

Maintenance Work to Resist Breakdowns in the Allocation of Care

While the allocation of care at SERV included coworkers, this confronted employees with the dilemma of care allocation. Supporting each other was demanding as it required time and emotional investment. When this care allocation was threatened by extreme tensions between competing caring needs, we observed three ways in which employees engaged in maintenance work to resist any reduction in the allocation of care: asserting the need for care for coworkers, problematizing competing care needs, and inverting care priorities. Figure 4 illustrates this maintenance work.

Figure 4: Resisting Breakdowns in the Allocation of Care at SERV

Asserting Care for Coworkers

First, we observed that SERV employees constantly asserted the need for care for coworkers. They reminded each other that care must be extended to others at work, independently of care for the work. The following interview excerpt illustrates how Maelle resisted threats to undermine care for coworkers by asserting this care as an obligation in itself.

I have experienced here, then at work but not here with the SERV team, with a person who was outside, who was working in the [Prevention team], who was dealing with a grief, the death of her husband, who went through a period of depression after he passed away and … who was pouring out like that naturally without being asked. She was coming to us, sitting down and then talking, talking, talking … about what she has experienced that is super hard, that she cannot cope with it. And several times she came in front of me at the office. I did not say, … “well I have work to do, I can’t listen to you.” I was able to tell her, but after perhaps half an hour or forty-five minutes of listening to her on her personal life, “perhaps it would be important that you could see a professional, that you could confide in somebody else.” But I could not close the door bluntly saying “this is not the right place.” … Well, I felt … I would not even say I had to, because then I felt like I was helping. For her at that time, she needed to talk, hence I was available for her, so I listened to her naturally (Maelle, Social Work).

When Maelle was confronted with a need to care for a colleague in another social service department who could not get through a personal loss and kept looking for support in the office, she struggled because it demanded a huge amount of time and attention. She was ambivalent about it, but decided to remain available to her, even though it drained her energy and time and encroached on her work tasks. She explained that it would have been “inhumane” not to care for her colleague during this testing time.

Problematizing Competing Needs for Care

Another way in which SERV workers resisted shifting of the boundary of care in favor of work was through problematizing care. This meant collectively acknowledging the dilemma of care allocation between the work and coworkers. SERV employees recognized that personal issues did impinge on their work. Since they cared deeply about their work, they were bothered that these personal situations prevented them from fulfilling their mission. The pregnancy situation was a sharp illustration of such an impingement. During the observation period, two care workers announced their pregnancies and went on maternity leave. The excerpt below shows how coworkers used humor to problematize the dilemma:

Alizée (Secretariat) tells me the story of when Sabine (Social Work) announced she was pregnant, emphasizing how surprised they were. They laugh about the situation, but in a very benevolent tone, without judgment, assuming that expecting babies is always good news, but naturally not necessarily for work, especially since she is pregnant with twins and had to stop working so soon. Hence, when Maelle (Social Work) announced she was also pregnant, that was such a bad coincidence.

They were in a team meeting discussing how to cope with Sabine’s absence before she would be replaced. But when they turned to Maelle, she felt she had to tell them she was pregnant as well (she explained this to me in the car later). So Gilles, the head of service, made a theatrical joke: he stood up, put his coat and scarf on, and left the room. And they are still laughing about it.

The situation was comical because of the sequencing. This was considered a sort of “bad luck” situation. Gilles’ practical joke—pretending to leave—emphasized that the situation was no longer tenable: how could they cope with two colleagues on maternity leave when there was so much work to do? SERV employees understood the joke because they acknowledged that it made their work more difficult. Nevertheless, colleagues were not resented for being pregnant and did not (as at COMMS) seek to hide it from their coworkers, who were ultimately happy for them. In one of the following meetings, Christine (Social Work) joked: “Bad news of the day: who is pregnant?”

The excerpt above shows not only the initial problematization of the pregnancy when the news was broken, but also how such an important personal event took precedence over the work. While pregnancy was not good news for the work that had to be completed, it was still celebrated as good news for the person who was expecting.

Inverting Care Priorities

Finally, SERV employees allowed caring priorities to be inverted. When deemed exceptionally significant, the need to care for a coworker could be prioritized over care for the work. An illustration of this was part-time work to take care of one’s own children as utilized by several social workers with young children. Nobody ever questioned this decision, even though it imposed strong constraints on the organization of the work. It was very difficult for part-time workers to take on occasional extra tasks; the responsibility rested on the full-time workers, and hence was not shared fairly in the team. Moreover, part-time work made it much more difficult to arrange the numerous meetings and appointments that constituted a large part of the work. Even though working part-time was not an efficient configuration for the job, there was no question of changing this situation.

DISCUSSION

Ethicists of care have pointed out the dilemma of care allocation that arises because resources are limited while needs for care are infinite (Held, Reference Held2006; Tronto, Reference Tronto1993). We have found that care for work and care for coworkers compete for these limited resources (e.g., time, attention, emotions), leading to a dilemma between the two. Moreover, in some organizations, workers care both for the work and for coworkers (Rynes et al., Reference Rynes, Bartunek, Dutton and Margolis2012), while in others, care for coworkers is neglected (e.g., Gunn, Reference Gunn2011; Jackall, Reference Jackall1988; Linsley & Slack, Reference Linsley and Slack2013; Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Cunha and Rego2015). Based on the two organizations we studied, we examined how specific allocations of care were maintained. We found that employees coped with the dilemma of care allocation through recurrent boundary work (Langley et al., Reference Langley, Lindberg, Mørk, Nicolini, Raviola and Walter2019), which led to them explicitly or implicitly allocating or denying care to coworkers. This boundary work constituted a purposeful individual and collective effort to demarcate, enact, and re-enact what was worthy of attention while at work.

While the dilemma of care allocation is pervasive in work organizations, we have found that different organizations approach it differently. The contrast between COMMS and SERV was chosen as part of our research design because we were looking for research settings where issues relating to care would be a core focus as opposed to a secondary matter. It is beyond the scope of this article to explain whether the differences in care allocation we observed between COMMS and SERV reflected the types of organization—an advertising company operating in a hyper-competitive market and a social service agency providing a public good. Indeed, when care concerns are at the core of the organization’s mission, we might expect it to be more natural for individuals to raise the dilemma of care allocation. Yet public care services are becoming ever more subject to marketization (Fotaki, Reference Fotaki2011; Lloyd, Reference Lloyd2005), and in practice, observations tend to show that individuals and organizations deal with the tension between providing care and optimizing organizational resources through mechanisms that allow the tension to be ignored entirely (Fotaki & Hyde, Reference Fotaki and Hyde2015; Llewellyn, Reference Llewellyn1998). While institutional and economic conditions may play a role in our ability to care for each other in the workplace (Fotaki & Prasad, Reference Fotaki and Prasad2015; George, Reference George2014; Wrenn & Waller, Reference Wrenn and Waller2017), our study has shown that it is not external constraints of the organizational environment alone but, instead, it is the everyday boundary practices of coworkers that suppress or acknowledge care for coworkers.

We discuss below how our theorization of the role of boundary work in maintaining care allocations in the workplace allows us to contribute to management and organization theory. In particular, we emphasize that boundary work demarcating personal and professional selves is a political act that undermines care in the workplace. We also contribute to knowledge on care in organizations by focusing on the importance of the wholeness of the person at work. We then extend our reflections to moral boundaries in the workplace and finally discuss implications for practice.

Boundary Work and the Undermining of Care in the Workplace

Management and organization researchers have proposed the ethics of care as an alternative ethical framework for organizations (Lawrence & Maitlis, Reference Lawrence and Maitlis2012; Liedtka, Reference Liedtka1996). However, the problem of care allocation with limited resources (Liedtka, Reference Liedtka1996; Tronto, Reference Tronto1993) remains largely ignored, preventing us from fully understanding how an ethics of care materializes in practice. This research suggests that such neglect may reflect suppression of the care dilemma in the workplace, cultivated through the boundary work (Lamont & Molnár, Reference Lamont and Molnár2002; Langley et al., Reference Langley, Lindberg, Mørk, Nicolini, Raviola and Walter2019) involved in demarcating personal and professional selves.

Boundary Work and Suppression of the Dilemma of Care Allocation in the Workplace

The feminist ethics of care reveals that care is undervalued in our society (Held, Reference Held2006; Sevenhuijsen, Reference Sevenhuijsen1998), and that political choices dictate whose needs are attended to (Tronto, Reference Tronto1993, Reference Tronto2010). Our empirical study shows that care for coworkers is equally undervalued in work organizations. At COMMS, the boundary work consisted of constraining aspects of personal life that would impinge on commitment to work, precisely because they would make explicit the care dilemma and the need to care for coworkers; yet care for coworkers remained implicit and would resurface in extreme situations. However, this undermining of care might also be contested. Prioritizing care for the work over care for coworkers was contested at SERV, where members were making a collective effort to resist the blindness to personal issues that comes with notions of professionalism (Sanchez-Burks, Reference Sanchez-Burks2002), and to remain attentive to coworkers’ caring needs.

We see that the way the dilemma of care allocation between work and coworkers is settled through organizational practices constitutes a political act that reflects the priority given to potential needs for care. These findings echo Tronto’s (Reference Tronto1993) assertion that attentiveness to the need for care is political, as it poses a key challenge to the enactment of an ethics of care:

We have an unparalleled capacity to know about others in complex modern societies. Yet the temptation to ignore others, to shut others out, and to focus our concerns solely upon ourselves, seems almost irresistible. Attentiveness, simply recognizing the needs of those around us, is a difficult task, and indeed, a moral achievement (Tronto, Reference Tronto1993: 127).

In the specific context of work organization, we find that the issue of shutting others out is further heightened by our concerns upon our work. The attentiveness that Tronto emphasizes is not merely a matter of “noticing” (Kanov, Maitlis, Worline, Dutton, Frost, & Lilius, Reference Kanov, Maitlis, Worline, Dutton, Frost and Lilius2004). Admittedly, when the need for care is not made available to be noticed, there is no possibility of caring. However, this availability is not a question of materiality—such as in open-plan offices— but rather a question of the meaning we attribute to it. Noticing is only possible when a pre-existing meaning is attributed to the individual employee as a person and a whole human being, not merely as a worker. Our theorization based on boundary work suggests that individuals’ presence as whole human beings at work is determined by the purposeful symbolic meaning attributed to them, rather than the material permeability of the boundary, as discussed next.

The Wholeness of the Person and the Possibility of Care in the Workplace

The boundary work observed in this research was concerned not merely with recognition of two different spheres—work and home—but rather with the wholeness of the person. Should workers be considered only as workers, or as whole people? This relates not to the spatial and temporal separation of work and home (Clark, Reference Clark2000; Kreiner, Hollensbe, & Sheep, Reference Kreiner, Hollensbe and Sheep2009; Ollier-Malaterre, Rothbard, & Berg, Reference Ollier-Malaterre, Rothbard and Berg2013), but to the necessity to consider workers in their entirety (George & Dane, Reference George and Dane2011; Peus, Reference Peus2011). At SERV, there was a marked spatial and temporal distinction between work and home, yet the personal part of the individual employee, which did not necessarily contribute to the work, was brought into existence. In contrast, at COMMS, only the person’s professional dimensions, along with personal aspects serving the work (“personal-professional”), were allowed within the symbolic boundary constituting the “worker.” Personal aspects that were likely to conflict with work interests (personal-personal) were left outside this boundary. Objects worthy of attentiveness unfold from such boundary work. Hence, boundary work contributes to determine what constitutes the worker, what should be taken care of (Tronto, Reference Tronto1993), and what does not count as care.

Our findings suggest that only when no explicit boundary is drawn between a coworker’s productive and “unproductive” care dimensions, and when the other person is recognized as a whole human being, can caring for coworkers materialize and thrive. When the human side of workers is obscured, this allows for their subjection to the productive imperative. Hence, this research suggests that the question of the wholeness of the person is critical to the possibility of developing caring relationships in organizations.

Further Reflections for Understanding Moral Boundaries in the Workplace

This research supports a view of morality in organizations as collectively constructed from the structure and culture of the workplace (Gehman, Trevino, & Garud, Reference Gehman, Trevino and Garud2013; Gordon, Clegg, & Kornberger, Reference Gordon, Clegg and Kornberger2009; Jackall, Reference Jackall1988; Reinecke & Ansari, Reference Reinecke and Ansari2015; Sonenshein, Reference Sonenshein2005, Reference Sonenshein2007; Whittle & Mueller, Reference Whittle and Mueller2012) and emerging in interactions (Anteby, Reference Anteby2010; Linehan & O’Brien, Reference Linehan and O’Brien2017). In his classic ethnography, Jackall (Reference Jackall1988) demonstrated how managers systematically shut out elements of work that they felt they could do nothing about. Here, we go one step further to show how employees in the organization create blind spots for themselves (Fotaki & Hyde, Reference Fotaki and Hyde2015), the blind spot in this case being coworkers’ humanity as whole persons. Building on research on boundary work (Hobson-West, Reference Hobson-West2012; Kantola & Kuusela, Reference Kantola and Kuusela2019; Lamont & Molnár, Reference Lamont and Molnár2002; Langley et al., Reference Langley, Lindberg, Mørk, Nicolini, Raviola and Walter2019; Peifer, Reference Peifer2015), we suggest that this concept is central to understanding the construction of a specific morality in organizations (Palazzo et al., Reference Palazzo, Krings and Hoffrage2012; Parmar, Reference Parmar2014; Sonenshein, Reference Sonenshein2007).

Political and Ethical Underpinnings of the Personal-Professional Boundary

While traditional management research tends to portray the personal–professional divide as desirable in the modern workplace (McDonald, Townsend, & Wharton, Reference McDonald, Townsend and Wharton2013; Uhlmann, Heaphy, Ashford, Zhu, & Sanchez-Burks, Reference Uhlmann, Heaphy, Ashford, Zhu and Sanchez-Burks2013), we join ethicists of care in challenging this idea. The latter regard the public–private boundary as confining care to the sphere of the family and personal life (Fisher & Tronto, Reference Fisher, Tronto, Abel and Nelson1990; Tronto, Reference Tronto1993). Organization and management researchers agree on the appropriateness of having a boundary between life in and outside work. Research on work–life conflicts reveals that employees engage individually in boundary work to enhance their identity (Kreiner, Hollensbe, & Sheep, Reference Kreiner, Hollensbe and Sheep2006; Ollier-Malaterre et al., Reference Ollier-Malaterre, Rothbard and Berg2013), as well as negotiating their preferences regarding the extent to which their work and family lives are segmented (Clark, Reference Clark2000; Kreiner et al., Reference Kreiner, Hollensbe and Sheep2009; Nippert-Eng, Reference Nippert-Eng1996). We contribute to this debate by showing that this boundary work is not merely an individual effort but is rather the result of a collective effort to negotiate meaning, which has significant political and ethical underpinnings.

The undermining of care that results from this boundary work in turn enhances “professionalism” as a desirable value, and as an attribute that the person at work must continuously display. Professionalism has been associated with the capacity to look at things from a distance, without being biased by affect (Sanchez-Burks, Reference Sanchez-Burks2002). In this view, professionalism, seen as cold reasoning as opposed to emotionality, will hinder the possibility for care. Our study questions the compatibility of this view of professionalism with the possibility of caring for people at work. It has been argued that bodily affects and emotions, such as compassion and sympathy, condition the enactment of an ethics of care in the workplace (Fotaki, Reference Fotaki2015). If care requires the engagement of emotions, the professional downplaying of emotions will make care impossible. This may explain Gatrell’s (Reference Gatrell2019) “abjection as practice” regarding rejection of the maternal body at work: the professional, non-affective workplace cannot indulge nor even accommodate breastfeeding mothers who so triumphantly symbolize the value of care.

Scholars increasingly recognize that emotions are an important source of organizational knowledge that have an impact on institution building (Creed, Hudson, Okhuysen, & Smith-Crowe, Reference Creed, Hudson, Okhuysen and Smith-Crowe2014; Lok, Creed, DeJordy, & Voronov, Reference Lok, Creed, DeJordy, Voronov, Greenwood, Oliver, Lawrence and Meyer2017) and shape moral choices (Toubiana & Zietsma, Reference Toubiana and Zietsma2017; Wright, Zammuto, & Liesch, Reference Wright, Zammuto and Liesch2017). We contribute to this stream of research by showing that the boundary between personal and professional self actively promoted in the modern workplace may actually be seen as a political act to shut out emotions that would otherwise trigger moral dilemmas and threaten consideration of work as the highest moral good.

Implications for Practice: Recognizing the Ethical Dilemma of Care Allocation