The 1970s wave of criticism against multinationals: An introduction

During the last decade, we have seen an increased opposition to globalization and its various implications, such as free trade, immigration, and the international division of labor. Within this wave of criticism, firms and more specifically multinational enterprises (MNEs) have been major targets, accused of multiple wrongdoings, such as social dumping, fiscal evasion, job cuts, trade deficits, abuses of power, and environmental damages. In many respects, this debate echoes the one that took place during the 1970s with respect to oil shocks, de-industrialization, and imperialism.Footnote 1 At that time, several international organizations, such as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), The International Labor Organization (ILO), and the European Community (EC), started to address the issue of multinationals and international investments, and advocated for the creation of guidelines to regulate their activities.Footnote 2 These efforts to implement international regulations raised sensitive issues for MNEs, who feared that the new rules might affect their leeway to proceed to the necessary restructuring and to take advantage of diverse social and environmental standards in organizing their operations around the globe.Footnote 3 Relying on archival material from the Swiss Union of Commerce and Industry (the so-called “Vorort”) and the Federal Archives, the following paper explores the reactions of Swiss multinationals to these attempts, as well as their strategies for protecting their latitude in conducting business.Footnote 4

The contribution of the article is twofold. First, it contributes to the literature on the history of Swiss capitalism. This growing body of research has demonstrated the strong influence of organized business on Swiss politics, which has not only been exerted through formal and institutionalized consultation procedures but has also often been realized through informal channels due to the porous boundaries that exist between political and economic elites.Footnote 5 Several studies document the specific importance of business interests in shaping Swiss foreign policy and the Swiss government's efforts to defend and secure the foreign investments of Swiss banks and multinationals.Footnote 6 Some recent contributions have also analyzed the propensity of Swiss industrial MNEs to progressively identify themselves as a distinct group within the Swiss business community and to engage in collective lobbying activities.Footnote 7 This article builds on and complements those findings by analyzing how the willingness of international organizations to regard multinationals as a specific subject of regulation in the 1970s prompted representatives of Swiss MNEs to engage in a common political strategy and, as we shall see, involve the Swiss foreign diplomacy to intervene on their behalf.

Second, this contribution furthers our understanding of the political role of MNEs in shaping global governance. It draws on Pepper Culpepper's observation that “the international capitalist system is not a sclerotic network in which the structural location of firms and the relationship of states to those firms are determined solely by resource endowments” and that “the rules that define the system are instead a subject of ongoing political struggle.”Footnote 8 Thus, this paper regards the creation of international guidelines as an interactive and iterative process in which MNEs are agents who try to influence international structures just as much as international structures operate to constrain them.Footnote 9 The analysis also explores how structural power and instrumental power are intertwined,Footnote 10 bringing to light how MNEs have used their instrumental power—by lobbying—to secure their structural power, that is, their ability to control investments in the global economy and take advantage of their exit options.

Studying the strategies of MNEs for dealing with the creation of international guidelines is particularly worthy of interest since, so far, the political and institutional role of MNEs has received much less attention from business historians than their economic strategies or their organizational forms. One explanation for that oversight might be found in the legacy of Alfred Chandler, who contributed to making the hand of managers so visibleFootnote 11 and to drawing attention to economic efficiency to the extent that this somewhat eclipsed other issues around business activities, such as the involvement of entrepreneurs in the political arena at the national and international level. As Martin Jes Iversen puts it, “the critical question remains how companies, viewed in a historical perspective, shaped institutional settings and used these settings as important resources for growth.”Footnote 12

The lack of empirical knowledge of multinationals’ strategies is especially problematic, and not only for the business history field, since it tends to create alleged and preconceived ideas about their effectiveness to impose their will in the political sphere. Indeed, as Christian May and Andreas Nölke point out, “what corporations want, and how they go about achieving it, has often been deduced from macroeconomic and political structures” so that, today, the multinationals and their power have become “mythical.”Footnote 13 In addition, as sociologist Tim Bartley notes of the influence of MNEs on international institutions, their role is even more difficult to grasp when these corporations try to inhibit the establishment of international governance:

There is little doubt that companies have inhibited the development of global governance in some arenas, particularly with regard to labor rights, climate change, hazardous substances, and corporate taxation. […] Specifying exactly what has been inhibited and how, though, is more difficult. Scholars typically focus on governance arrangements that have emerged, rather than looking for failed cases or the watering down of rules over time. Additionally, it is usually easier to observe government representatives negotiating final versions of treaties than corporate actions prior to that point.Footnote 14

Business historians, by drawing on internal and confidential archival materials, have a privileged vantage point from which to study MNEs’ attempts to influence or to prevent the development of institutional settings, as some recent works focusing on the role of companies and business interest associations in shaping US and British politics have shown.Footnote 15 Indeed, a large part of this influence takes place behind closed doors and is therefore difficult to grasp from public sources. It is with good reason that Kim Philipps-Fein uses the expression “invisible hands” in the title of her book to underline the role of some business leaders in building the conservative counterattack against the new deal in the United States.Footnote 16 Moreover, as the political scientist Culpepper theorized and tested, such quiet politics are even more important to study since business leaders and their lobbying associations tend to be more successful when they can act outside the public sphere, and when the legitimacy of their expertise is taken for granted, without being subjected to political struggle.Footnote 17 Drawing on primary sources that were inaccessible to the public in the 1970s, this article therefore sheds light on the little-known and until now largely undocumented political strategies of Swiss MNEs.

The article is structured as follows. The first section analyzes the reactions of Swiss multinationals to the creation of international guidelines and uncovers the existence of an informal task force to deal with this issue. The second section looks inside Switzerland to study political cooperation between firms and the relationships between MNEs and the government, i.e., the functioning of the Swiss capitalist system. The third section analyses the transnational ramifications of the MNEs’ lobbying activities and the channel of influence they have sought to create to reach international organizations.

The empire strikes back: The creation of the Swiss multinationals’ informal task force

At the beginning of the 1970s, the driving forces behind the establishment of international guidelines were Third World countries and labor union organizations. The former were eager to witness the rise of a new international economic order in which postcolonial states would enjoy political and economic sovereignty and, therefore, be able to control the exploitation of their natural resources and benefit equitably from economic activities undertaken on their soil. In advanced industrialized countries, the latter were asking for a larger share of the benefits and more democracy in the workplace, especially regarding investment and restructuring decisions.Footnote 18 Their common hope was that the international community would ultimately agree on a binding agreement that would regulate the activities of MNEs. The foreseen provisions were manifold and included social and labor standards, codetermination rights regarding investment and restructuring, environmental norms, fiscal evasion and transfer pricing regulations, technological transfer, and transparency provisions. These calls for more regulation did not fall on deaf ears, and the “multinational” or “transnational” activities of companies soon became a concern in international organizations such as the OECD, ILO, ECOSOC, and the EC.

Because of these trends, the leading figures of Swiss MNEs had to acknowledge that their business activities would be a matter of political and public concern for years to come. Indeed, in its 1973 annual report, Industrie-Holding, the association of Swiss multinational companies noted that “MNEs have been a fashionable topic for politicians, academics and journalists. The number of publications in this domain is significant.”Footnote 19 This sudden attention as well as the regulatory processes launched in several international institutions were concerning to executives of major Swiss multinational companies. Indeed, in a meeting organized by the Division of Commerce in June 1974, which brought together representatives from the chemical industry (Ciba-Geigy, Roche, Sandoz), the machine industry (BBC, Sulzer), the food-processing industry (Nestlé), the banking industry (UBS, Kreditanstalt), and business interest associations (such as Industrie-Holding and the Swiss Union of Commerce and Industry), the general opinion of the Swiss business community on international guidelines for MNEs was clear. “At best, no guidelines and absolute freedom.”Footnote 20 Unfortunately for them, it was soon obvious that the ongoing regulatory processes launched by international organizations could not be stopped, but in the best case scenario, they could be slowed down and/or driven in the least harmful direction.

The aversion to new regulations was certainly not confined to Swiss MNEs.Footnote 21 Businesses from other countries were also worried about what they perceived as “attacks on the free enterprise” during the 1970s.Footnote 22 However, Swiss MNEs were particularly sensitive to these issues since many of them, such as Nestlé and Ciba-Geigy were—and still are—among the most internationalized firms.Footnote 23 Because of the small size of the Swiss domestic market and companies’ attempts to avoid protectionist barriers, the internationalization of Swiss firms had been an iconic characteristic of the Swiss economy since the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote 24 Therefore, Swiss MNEs considered their international structure as vital, and their long-term experience of globalization had made them very aware of the fact that political decisions might have significant consequences on their ability to maintain and strengthen their expansion.Footnote 25

Regarding the guidelines, various matters were at stake for the Swiss MNEs. The first matter of concern was their legal scope.Footnote 26 In the Swiss MNEs’ view, the code of conduct should be of a non-binding nature, and the final choice to follow the recommendation or not should remain in the hands of executives. A second matter of concern was the definition of what exactly was considered a “multinational company.” The representatives of Swiss MNEs feared that their companies might be discriminated against because of their status if the definition was too restrictive and did not include small firms, state-owned enterprises, or national companies. Therefore, they advocated for a broad definition, based only on a single geographic criterion: having at least one subsidiary outside the home economy. Other matters of concern related to the preservation of MNEs’ structural power with respect to host states and the power of the labor unions. The MNEs did not want to be judged on the international stage since they already had to respect the national laws of host states: special rules for MNEs with respect to labor or environmental standards were, therefore, regarded as discriminatory. On the contrary, the Swiss MNEs saw in the guidelines an opportunity to secure their private property by fostering the creation of international arbitration mechanisms in case of nationalization. Finally, yet importantly, Swiss MNEs feared a strengthening of the role of labor unions if the code should specify labor rights not existing thus far in Switzerland, such as workers’ participation or the right to corporate information. In addition, they wanted to keep labor relations decentralized and to avoid by any means necessary direct negotiations between labor unions and company leadership. Various battle lines were therefore drawn upon the guidelines, where the MNEs’ interests might oppose the interests of labor representatives in addition to the interests of developing countries or communist economies.

In light of these issues, some of the most prominent Swiss MNEs decided to create an informal task force, called the Wirtschaftspolitsche Arbeitsgruppe über multinationale Gesellschaften in September 1972.Footnote 27 Describing the international ramifications of Swiss industries, sociologist François Höpflinger published a book during the 1970s entitled, The Swiss Empire.Footnote 28 Consequently, in following the activities of the Swiss MNEs task force, this case study analyzes how “the Empire strikes back.” In the Swiss Union and Commerce of Industry archives, the first available minutes of one of those Swiss MNEs group meetings dates from 1973, and was written by its first coordinator, Christoph Eckenstein, who was a Swiss diplomat and former special counselor to Raul Prebisch when he was general secretary of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).Footnote 29 Upon his death, Eckenstein was replaced in 1974 by Otto Niederhauser, director of the pharmaceutical company Ciba-Geigy and head of the Federal Office for National Economic Supply, a member of the economic and federal administrative elite.Footnote 30 Niederhauser would remain at the head of the task force until 1984, ensuring a decade of leadership and sustained cooperation. All members had high ranking positions in the following multinationals: Nestlé, Roche, Sandoz, Ciba-Geigy, BBC, and Sulzer. Alexandre Jetzer, secretary of the Swiss Union of Commerce and Industry, was also a permanent member as well as Theodor Faist, secretary of Industrie-Holding. In some meetings, high-ranking officials were invited, the most frequent being Hans Schaffner, former president of the Swiss Confederation, Paul Jolles, head of the Foreign Economic Affairs Directorate, and Philippe Lévy, head of the Division of Commerce. Task force membership was therefore already indicative of the strong existing ties within the business sector and some departments of the federal administration.Footnote 31 The meetings took place an average of five times a year.Footnote 32

The creation of the Swiss MNEs task force was justified by hardship, as its members noted for its tenth anniversary:

The efforts of the industry to promote a better investment climate dates notoriously back to 1972. […] A tightening of the debate and the deterioration of the international investment environment occurred in 1973 after the overthrow of Allende. The vehemence surrounding the discussions about MNEs in ECOSOC, ILO, EC, OECD and elsewhere prompted us to initiate our two task forces, and to have a closer look at further evolutions.Footnote 33

The notion of perceived vulnerability seems indeed critical to understanding company strategy in this context, as well as the laborious and time-consuming coordination that was required. In the task force meeting minutes, MNEs’ representatives indeed constantly referred to their activity mostly as defensive.

The informal MNE task force had two related goals. The first was to influence the spread of information on MNEs in order to improve their image. The second was to follow and influence international negotiations regarding the guidelines. Regarding information, among other efforts, in 1976, Nestlé created the Institute for Research and Information on Multinationals (IRM), based in Brussels and then in Geneva.Footnote 34 In addition, the Swiss MNEs were following through the task force each new published study, article, statement, and colloquium regarding their business activities. For example, they liked the work of Charles Iffland, an economist from the University of Lausanne, on Swiss FDI in Brazil,Footnote 35 but considered sociologist Peter Heinz's research project “extremely hostile to multinationals,” and hoped that he would not get funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation.Footnote 36 It is also interesting to note that Swiss MNEs refused to deliver data to the famous internalization specialist John Dunning in 1976, stating that his study was too detailed.Footnote 37 Outside the academy, the press, leftist critics, religious movements, and especially those of the World Council of Churches (WCC) based in Geneva were sources of concerns.Footnote 38 Here again, one sees MNE's perceived vulnerability to continuous attacks.

Regarding international negotiations, the task force wanted to avoid the creation of new rights and new institutions that could “lead to an escalation and end up as a wailing wall.”Footnote 39 In order to prevent this from happening, the first move of the MNEs was to establish a “Swiss perspective” on the question of international guidelines by assembling and summarizing individual viewpoints. To do so, the task force took the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) document “Guide for International Investments” and the related releases written by Industry-Holding's members.Footnote 40 This act was typical of the traditional way of finding a defendable consensus within private interests in Switzerland. The umbrella organization would consult their members (i.e., companies) through the distribution of communications. When all individual viewpoints were collected, the umbrella organization would then write a summary of the common interests of the concerned economic group.Footnote 41 This is what happened with the MNEs’ informal task force as well, and once the Swiss MNEs’ common view was settled, the next step was to find the means to communicate it. The next two sections will describe how the MNEs proceeded, first by sharing their coordination efforts at the national level and then at the international level.

Economic interest or general interest? The definition of Swiss economic foreign diplomacy

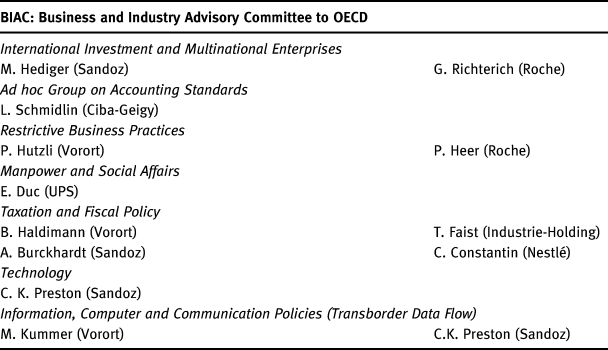

The first way for Swiss MNEs to influence international negotiations is to collaborate with official representatives of the Swiss government and to plant “experts” from their own circles in these areas whenever possible.Footnote 42 In the mid-1970s, the Swiss MNEs task force was closely following the negotiations at the OECD and ECOSOC and a bit less at the CE and ILO. MNEs voiced concerns about the CE at the beginning of the 1980s with the “Vredeling Initiative,” which was aimed at introducing the union right to information and representation at the CE level, and the “Caborn Report,” which listed the advantages and disadvantages of the MNEs’ activities.Footnote 43 Between the UN and the OECD, the environment was clearly less hostile to MNEs in the OECD since it assembled industrialized countries, and Switzerland had an official membership. The MNEs task force recognized this strategic consideration: “The negotiations at the OECD are for us especially important, since the OECD is a tribune of which our country is an official member; here its voice can be heard directly.”Footnote 44 Two Swiss representatives were at the head of the main organizations dealing with MNEs issues, and vouching for the importance of Switzerland as the home country for these types of companies. Jolles was in charge of the Executive Special Committee dealing with the questions of international investments and MNEs, and Lévy was in one of its expert subgroups. Both of them maintained close ties with the informal Swiss MNEs task force, participating in meetings and sending confidential documents, such as the 1974 report by the OECD Secretary General entitled, “Questions concernant l'investissement international y compris les activités des entreprises multinationales.”Footnote 45 Besides these ties with Swiss officials, the Swiss business community was also well integrated in the Business and Industry Advisory Committee to the OECD (BIAC) and in all groups dealing with MNEs issues (See table 1).

Table 1: Representatives of the Swiss Industry in BIAC in 1983. Source: WPA-MNU, Internationale Verbindungen: Personelle Kontakte/Kommissionen. AfZ, IB Vorort-Archiv, 291.4.2.2.1.4.

During informal discussions of the MNEs task force, hosted at the offices of Ciba-Geigy in October 1974 and in the presence of Jolles, the MNEs’ representatives advocated for a “Swiss dampening attitude,” since the OECD tended to go far in its investigations.Footnote 46 Therefore, even within this a priori rather business-friendly association, the Swiss business community involved in international production activities had avoided being the center of attention.

Even more worrisome for them was the United Nations’ resolution to put together a general report on MNEs conducted by experts, called the “Group of Eminent Persons.” This initiative was the result of the accusation of interference in Chilean politics allegedly by International Telephone and Telegraph, a US multinational. Due to the importance of Swiss MNEs, Hans Schaffner, former president of the Swiss Confederation and vice-president of the executive board of Sandoz, was chosen to be part of this selective group of twenty experts. Unfortunately, as for the OECD, we do not know exactly how the Swiss diplomacy managed to have its experts appointed over other countries’ experts, but what is sure is that they were in constant contact with the informal Swiss MNEs task force. In a win-win relationship, Hans Schaffner kept the other MNEs’ representatives informed on the progress of the negotiations, and they provided him data and useful material to strengthen his case.Footnote 47 During the negotiations in autumn of 1973 in New York, he was directly assisted by H. Glättli, another representative of Sandoz and member of the MNEs task force. Swiss business leaders were also represented by Pierre Liotard-Vogt, CEO of Nestlé, at the hearings in Geneva in November 1973, where about thirty experts from various domains (developing countries, MNEs, academics, and other relevant interest groups) had to answer questions.Footnote 48 A month before this session, Hans Schaffner participated in a task force meeting at the Hotel Bellevue in Bern where the firms’ delegates delivered a document to him that summarized their views and followed the questionnaire that the ECOSOC secretariat had prepared for the hearings.Footnote 49 This procedure is indicative of the Swiss business collective defense, since the content of Pierre Liotard-Vogt's statement was the result of prior work for which Hans Schaffner provided the questions and all the MNEs’ representatives helped formulate the best responses.

The minutes of the task force also retrace a few informal discussions between Hans Schaffner and the MNEs’ representatives about the other members of the Group of Eminent Persons and their thoughts on the negotiations. First of all, Hans Schaffner depicted “The East River Bureaucracy” as “hostile,” and noted with concern the “axiom” thinking of Philippe de Seynes, the associate General Secretary of Social and Economic Affairs, considering that “so much power in the hands of so few MNEs was inadmissible.”Footnote 50 Here again, a defensive attitude was evident on the Swiss side, and the former president of the Swiss Confederation expressed a great deal of mistrust regarding some of his colleagues in the Group of Eminent Persons. For instance, he judged the nomination of the French economist Pierre Uri as “worrisome,” and describes the Dutch former president of the European Commission, Sicco Mansholt, as a “perfidious left-wing extremist.”Footnote 51 Hans Schaffner had no better opinion of the German socialist Hans Matthöffer, and hoped that he would not harm the Swiss interests with his linguistic limitations. The economist John Dunning was perceived as “impartial,” and the Japanese Ryutaro Komiya was seen as one of his best allies, lacking “punch” tough.Footnote 52 These very open (and to some extent undiplomatic) exchanges of viewpoints are indicative of the atmosphere of trust and confidentiality prevailing among the informal task force of Swiss MNEs. It also shows how the MNEs’ top executives were ready to spend time and energy because of their perception that their enemies were numerous. It also confirms Samuel Beroud's and Thomas Hajduk's view that the apparent neutrality of international instance should be questioned, and that the role of so-called “experts” and their motives should be investigated.Footnote 53

Swiss efforts to influence the OECD and UN work experienced mixed results. At the OECD, the guidelines adopted in 1976, if not perfect, were at least tolerable for the Swiss business community. The code had a non-binding nature, and was not aimed at hindering the needed restructurings. At best, it dampened their surprise effect by informing the labor unions and authorities before the final decision regarding mass redundancies. Once the code was adopted, the Swiss diplomatic staff and especially Lévy, who participated in writing the text, were willing to prompt the Swiss business community to state publicly their support and willingness to implement its recommendations. According to his view, a “wait-and-see attitude could, in the long run, reinforce the convictions of those who have always professed that non-binding would never have the appropriate impact because of companies’ lack of will, and that only mandatory instruments would have the desired effect at the national and international level.”Footnote 54 Indeed, since something had to be given, at least symbolically, the OECD guidelines were clearly a lesser evil. The Swiss MNEs’ representatives looking backward in 1983 recognized that this code, in comparison to other regulatory initiatives, was “closest to the needs of the economy as well as the most balanced and suitable for improving the international investment environment.”Footnote 55

On the UN side, the result was less favorable. The fears of Hans Schaffner, in seeing his views cast aside, came true as he had to face opposition from representatives of the left and labor movements of industrialized countries as well as those of developing and communist countries. Consequently, the report was viewed as disappointing by the Swiss business community who asserted that many allegations were made without hard evidence.Footnote 56 Therefore, despite the thorough preparation of the MNEs, in contrast with what happened at the OECD, it was impossible to find enough support, and their statements remained just one voice among many. To make the point that he did not subscribe to the report's conclusions, Hans Schaffner wrote his own “dissenting report.” In addition, he published a book that same year to defend MNEs, denouncing the ongoing “campaign against multinationals and ultimately against the free market economy.”Footnote 57 These writings were discussed in the Swiss press, with the right-wing newspapers criticizing the unfair bias of the UN while the socialist and labor union circles pointed out the irony of Hans Schaffner's attitude. The Group of Eminent Persons’ report constituted the first step of international negotiations regarding MNEs at the United Nations, since it recommended the creation of international guidelines, and in order to do so the creation of the Commission on Transnational Corporations (TNCS) and the United Nations Centre on Transnational Corporations (UNCTC).Footnote 58 Because the views within these bodies were so varied, attempts to produce guidelines were unsuccessful, but nevertheless required the constant attention and effort of the Swiss MNEs task force to coordinate with the Swiss delegates and to place their own experts.

At this point, one could ask what role Swiss labor unions played in this story, since a huge part of the negotiations in the OECD, and to some extent, in the UN were made by civil servants on behalf of Switzerland as a whole. This question is even more relevant because of Switzerland's alleged adherence to the coordinated-cooperative model of capitalism and the role of moderator that the state should theoretically endorse. Regarding the negotiations, the general accounts were sent to all concerned interest groups, including Beat Kappeler, secretary of the Swiss Federation of Trade Unions, which was favorable to the international guidelines. Swiss labor unions were at the time collaborating with their international European counterparts and were promoting codetermination rights in Switzerland as well as on the international stage.Footnote 59 Nevertheless, the existence of the Swiss MNEs task force and its privileged ties to civil servants remained unknown . . . until meeting minutes and letters were leaked to the press four years later.

The controversy this leak caused is very interesting from the perspective of the varieties of capitalism since it offers us insight on what the historical players were thinking regarding their own system of representing interests and its legitimacy. During the postwar period, private–public coordination mechanisms and corporatist arrangements played a crucial and widely recognized role in Switzerland, as well as in several other European countries.Footnote 60 Authors such as Katzenstein praised these forms of institutional settings, which allowed for economic flexibility while granting political stability.Footnote 61 In his comparative study, Katzenstein also acknowledges the minor role played by labor unions with respect to the influence of business interest associations in Switzerland. This specific Swiss form of liberal corporatism was therefore brought into public debate by the publication of the confidential documents.

Behind the press release was a nonprofit organization called the Declaration of Bern, who obtained documents after Eckenstein's premature death and subsequent donation of his personal documents to the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies archives in Geneva.Footnote 62 The purpose of the NPO was to demonstrate to the public how MNEs were able to infiltrate the UN and its organizations, to maintain close relations with civil servants, and to put economic journalists under their thumbs. Its criticisms were not centered around the fact that the economy's interests were represented but rather the impression of asymmetry regarding the consideration given to labor and business interests:

It appears from the files that companies continuously exchanged information and maintained close ties with high-ranking civil servants in the Swiss government, whose loyalty they could count on, while other groups experienced enormous difficulties in being granted a simple audience with these same entities.Footnote 63

The secret character of the meetings and the fact that the presidents or vice presidents of the companies were often present was proof for the Declaration of Bern on the importance of international regulation for MNEs. The role of Hans Schaffner was particularly debated since he provided confidential documents to the task force, and because he said negative things about other members of the Group of Eminent Persons. In return, parliamentarians Jean Ziegler and Fanz Jäger asked the Federal Council for clarification regarding the nomination of Hans Schaffner and the role of the Division of Commerce.Footnote 64 In light of the scandal, the Division of Commerce prepared arguments for Fritz Honegger, the federal counselor in charge of the Federal Economic Department.Footnote 65 All arguments were based on the fact that what happened was merely a reflection of the Swiss coordinated system, and that close ties with the MNEs were normal, appropriate, and even recommended since they were the first concerned.Footnote 66

The so-called “multis-papers” affair turned, therefore, into a philosophical struggle regarding the role of company-labor-government relations in Switzerland. Advocates for close company-government relations stressed that it was the role of the Division of Commerce to support the interests of the economy and ultimately the collective interests of Switzerland as the home country of MNEs. For the Declaration of Bern NGO, the observations were a matter of great concern since they called into question the democratic functioning of institutions and because “Swiss foreign policy seems to be defined behind the curtain by economic lobbyists instead of being the result of parliamentary open deliberations.”Footnote 67 The scandal did not bring any concrete consequences, and publicly none of those involved expressed a mea culpa. Nevertheless, it is interesting to quote an internal note from the Federal Finance and Economic Service stating that from that moment on, the public should be better informed regarding the consultation of interest groups, that it was important to better secure the involvement of social partners, and above all “to make sure not to confidentially handle contacts that are normal.”Footnote 68 For the Swiss administration, the problem was therefore interpreted as being more about form than about substance and Swiss strategy being legitimately coordinated, even with the creation of ad hoc groups when necessary.

Old recipes for new problems: Attempts of Swiss multinationals to coordinate at the international level

Beyond the traditional way of integrating economic interests in the shaping of institutions and promoting coordination at the national level, Swiss MNEs also tried to innovate by mobilizing their foreign counterparts.Footnote 69 Indeed, Guy Altwegg, CEO of Nestlé, reported to the Vorort the attempts of European MNEs’ directors to meet in parallel with the Council of European Industrial Federations (CEIF) meetings. Eckenstein wrote a summary concerning this European MNEs group, and reported that the European MNEs’ leaders met in Paris, Frankfurt, and Basel between 1972 and 1973. On the Swiss side, the same companies as in the Wirtschaftspolitische Arbeitsgruppe MNEs task force were represented, but unfortunately no list of all Europeans MNEs participating was included with the summary. In explaining these meetings, Eckenstein noted:

At the origin of the informal group was the recognition that multinational companies were criticized from all sides (by governments, intellectuals, technocrats, academics, clergymen, unions, and so on). This criticism can have undesirable consequences for the functioning of these businesses and for the economic system in general. They create an unfavorable climate and prompt government decisions that are unnecessarily restrictive against big business.Footnote 70

The motivation behind the creation of this European MNEs task force was similar to that which caused the formation of the Swiss MNEs group: hardship and perceived vulnerability. The summary also listed the goals of these meetings, such as improving the sharing of information on the situation in each country and on the international stage, restraining the negative evolution through the national groups of the ICC, and so on.

Nevertheless, it seems that between the wish for better MNEs coordination at the European level and its achievement, the Swiss group noted an unfortunate discrepancy, sometimes indicative of diverging viewpoints and very diverse national situations.Footnote 71 Indeed, the Swiss MNEs task force interpreted the disappointing outcomes of the European MNEs’ group as resulting from its heterogeneity. In their view, a new group should be formed, excluding US MNEs active in Europe and extractive industries, in order to create a task force of “true European MNEs.”Footnote 72 If a constituency of such groups were realized, the Swiss MNEs task force noted that “before making contact with other companies, we should create a document which summarizes the goals of this European group. Then European companies (for example, Unilever and Philipps) should lead the creation of this group so that it does not appear to be a Swiss initiative.”Footnote 73 According to sources, it seems that in the end, the group was never created and the meeting in Basel was the last one since it was decided that the already existing heterogeneous group of European MNEs would become inactive. This failed attempt clearly shows how national logic still prevailed in the 1970s over the intrinsic interests of the MNEs. It also substantiates May and Nölke's observation that “the simple fact that elites are meeting on an international scale does not allow the conclusion that such meetings are de facto indispensable for the success of MNC strategies,” and that proof of the effectiveness of coordination is often lacking.Footnote 74

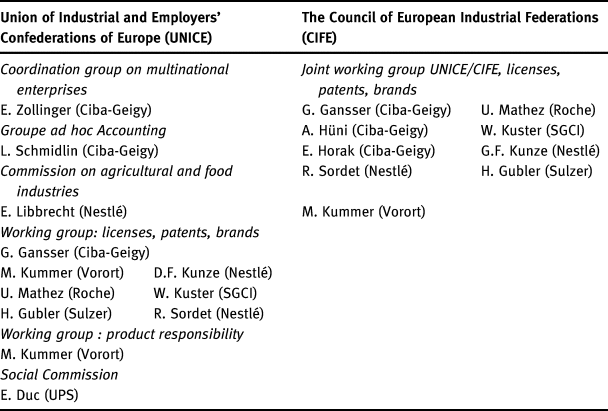

In addition to these attempts launched by multinationals’ representatives, multinationals’ interests were defended within existing international business interest associations, such as the Union of Industrial and Employers’ Confederations of Europe (UNICE) and the ICC by the Vorort. Regarding the UNICE, it's interesting to note the participation of Swiss business, despite the fact that Switzerland was not a member of the EC. Indeed, in 1974, Alexandre Jetzer, one of the Vorort's executive secretaries, informed the Swiss MNEs task force of an association agreement that implied that a member of the Vorort could participate in the UNICE commission on multinationals.Footnote 75 A year later, the MNEs task force noted that “through the UNICE and especially through its working groups, it is possible for Switzerland to exert a certain influence on the EC. Our efforts in that direction are undoubtedly worth it.”Footnote 76 Many company delegates were indeed members of several working groups related to foreign investments, such as those dealing with licenses and patents or those dealing with accounting standards (see table 2).

Table 2: Representatives of the Swiss industry at the UNICE and in CIFE in 1983. Source: WPA-MNU, Internationale Verbindungen: Personelle Kontakte/Kommissionen. AfZ, IB Vorort-Archiv, 291.4.2.2.1.4.

If, thanks to documents in the archives of the Swiss Union of Commerce and Industry, it is rather easy to understand and show the willingness for creating more cooperation at the international level and to expose part of the networks that the Swiss business community developed, it is more challenging to measure the concrete effectiveness of those strategies. Regarding the role of the Swiss business community at the UNICE, we did find an example showing how the Vorort succeeded in creating and shaping a UNICE statement, which was ultimately transmitted to the EC. This happened in the context of the publication of the UN report on MNEs made by the Group of Eminent Persons, whose content displeased the Swiss MNEs representatives and the Vorort. In order to undermine its conclusions, the Vorort, through the intermediary of its secretary, Alexandre Jetzer, intervened to prompt the UNICE to officially condemn the document. Its request was processed by the UNICE “Coordination Group Multinational Enterprises” on 25 June 1974 in Brussels.Footnote 77 The other delegates were reluctant to issue such a release, since they considered it to be more a prerogative of the ICC. It is through perseverance that Alexandre Jetzer was able to make his counterparts agree to the creation of the release, on the condition they would get a turnkey draft. The Swiss delegation provided a text the very same day. While the harsh Swiss tone was a bit softened, the UNICE delegates adopted the text without substantial modifications, allowing the Vorort to impose its view on MNEs. The UNICE secretariat communicated the release to the European Commission on 9 June 1974, while the delegates of its Coordination Group Multinational Enterprises transmitted it to their respective national delegations. This constitutes an example that shows how the Vorort, thanks to its readiness and coordination at the national level, was able to make its voice heard at the European Commission and to have the UNICE condemn the UN report on MNEs by the Group of Eminent Persons.

It should nevertheless be noted that the Vorort as well as the Swiss MNEs task force constantly complained about the lack of coordination and inability of international business interest associations like the UNICE and the ICC to defend a common position. Another complaint was the insufficient efforts of the BIAs of various countries in pressuring their national representatives negotiating in international organizations. Indeed, even if an agreement was found within the UNICE or the ICC, the best way to defend the business position was still to have their own official national delegates fighting for their interests, as would be the case in the Swiss coordinated system. In reality, this was rarely what happened. For example, regarding negotiations for the technology transfer code at the UNCTAD in 1979, Guy Altwegg, assistant director of Nestlé, wrote to Otto Niederhauser, the head of the Swiss MNEs informal group, to complain about the lack of assertiveness on the part of the industrialized countries’ delegates and the complete indifference of certain delegates. He commented on the situation in no uncertain terms:

Which conclusions should we draw from these observations? […] Without any doubt, the industrial circles of many developed countries, even among the most developed, do not care enough about these codes, do not have the audience of their government's ministries in charge of the negotiations or do not make enough effort to inform their government on the sensitive issues that could be detrimental to their foreign activity. I think that we should try to improve this situation, and that we should engage in informal actions toward our industrial neighbors in major developed countries. We should examine with the Vorort how contacts could be established early on before negotiations with employers’ associations from certain industrialized countries […].Footnote 78

The Swiss MNEs task force and the Vorort repeatedly pursued these efforts launched in the 1970s, and yet again throughout the 1980s since the UN code was still in effect. Indeed in 1982, the Vorort issued a new “Swiss position paper” regarding the UN guidelines, listing the points that still needed to be refined.Footnote 79 The document was transmitted on 15 February to the “Coordination group multinational enterprises” of the UNICE.Footnote 80 In addition, the “Swiss position paper” was sent to the some of the heads of European Industrial Federations, such as J.A. Dortland, secretary of the Dutch VNO-NCW.Footnote 81 The production of information, its diffusion through several channels and the cultivation of various contacts within their European counterparts were all part of the strategy of the Swiss MNEs task force and the Vorort to gain influence on the multilateral stage. In 1983, the representatives of the Swiss MNEs, by summarizing their past activities noted that if “in Switzerland, the collaborative work between the Vorort and the Swiss authorities on the UN-Guidelines was manifold […] this collaboration should be improved abroad with other firms and industrial federations.”Footnote 82 These limitations and the resulting opportunities for improvement show how coordination is not an easy task, but rather necessitates constant effort to produce and reproduce.Footnote 83 It was only in 1987 that the Swiss MNEs task force recognized that the functioning of the UNICE had improved, and that this association had started to achieve some good results and wasn't simply “producing a lot of paper.”Footnote 84

Concluding remarks

First, the analysis shows that the attempts of international organizations to introduce guidelines were far from seen as harmless by Swiss MNEs. Indeed, the fear and the perceived vulnerability of MNEs’ representatives were driving forces behind their coordination as a task force and their continuous efforts to engage in political activities. The proliferation of time-consuming meetings and their systematic collection of information concerning their companies prove that they took the work of international organizations seriously. The critical judgements formulated about international civil servants, experts, and unionists by some of the MNEs task force participants are also indicative of their impression of being constantly under fire. This observation of perceived vulnerability is to some extent counterintuitive, since the 1970s controversy was precisely over the question of the allegedly excessive power of multinationals. The attitude of the MNEs showed, therefore, that they were not at all convinced that globalization was following an inevitable evolution, and that they were fully aware that their ability to engage in global production was very sensitive to political decisions and institutional frameworks. Thus, Swiss MNEs used their instrumental power in various ways in order to preserve their structural power.

To preserve their ability to conduct business freely, it appears that Swiss MNEs embraced the idea that unity creates strength. The content of the archives shows the close ties existing among high-ranking MNE representatives from different sectors and the secretive and familiar character of their meetings. It also shows how the MNEs’ task force was integrated into the traditional network of coordination within the Swiss business interest associations, since it included a representative of the Swiss Union of Commerce and Industry. The analysis also demonstrates how MNEs’ representatives relied on Swiss diplomacy to defend their views within international organizations. The fact that the MNEs chose coordination from the many possible strategies as the means to achieve their goals is an interesting illustration of the importance of embeddedness in national institutional arrangements, even for organizations that allegedly have more freedom, such as multinationals. In addition, the archives’ contents uncover how assimilated their interests were to the national interest in general by Swiss diplomacy, without further political debates. The Swiss labor unions, who were in favor of ambitious guidelines, were mostly ignored, and even when the privileged ties between the MNEs representatives and some high-ranking civil servants were exposed in the press several years later, the scandal did not induce concrete changes in the way Swiss foreign policy was shaped.

If the analysis confirms some observations made by other researchers about the importance of coordination between firms and federal authorities within the Swiss capitalist system, it also shows that the work undertaken in international organizations prompted Swiss multinationals to develop new ways of coordination beyond the national level. With their multinational counterparts from other countries, Swiss companies tried to recreate some well-established coordination mechanisms that worked inside Switzerland. Similar efforts were made by the Vorort, which assisted the Swiss MNEs informal task force, for example, by helping to define a European employer's common position on the MNEs codes of conduct within the UNICE. These channels of influence were even more important, since Switzerland was neither part of the United Nations nor part of the EC. The study therefore points out a reverse correlation between the political strength and official representation of a country and the efforts of its national companies and employers’ associations to reach the international level and build coalition with their counterparts.

Regarding their own organizations and that of their counterparts, the judgements of the Swiss MNEs and the Vorort are ambivalent. On the one hand, regarding its influence and coordination at the national level, the Swiss business community was very confident, and conscious of its privileged ties to political authorities compared to other countries. On the other hand, when it comes to their ability to impose their views and ways of employing coordination at the international level, these same entities stressed many difficulties because of the divergent opinions within the employers’ community and the lack of communication. Indeed, if the archives show the existence of an inner circle of representatives of big companies at the Swiss national level, it seems that no equivalent existed at the international level during the period under investigation.

Ultimately, this article invites readers to rethink the relationship between multinationals and the politics of global trade governance by considering multinationals not only as powerful economic agents but also as political actors. This historical analysis shows that multinationals actively and purposefully influenced the creation of new international institutional frameworks, albeit with varying degrees of success. By revealing this fact, the article puts into question mechanistic and deterministic explanations, which too often consider the current organization of production in global value chains as the logical outcome of the globalization process and firms’ rational economic responses to it. Since it appears that there was nothing natural about economic integration and the global rules of the game, scholars should pay more attention to the power struggles that contributed to shaping the regime of global governance if they wish to understand firms’ ability to take advantage of it.