We assume that exporters prefer freer trade. Nearly a century ago, classical trade theory's specific factors model addressed the implications of what entire internationally-oriented industries stood to gain from trade,Footnote 1 and today this underlying concept is refined by new-new trade theory's rigorous focus on the heterogeneity of firms, wherein export activity has been found to be a strong predictor of pro-liberalization preferences and behavior.Footnote 2 This accords with the image of the prototypical exporting firm that the literature produces: large, productive, innovative . . . and few and far between.Footnote 3 In particular, exporting is viewed as costly—so much so that only a small upper tier of firms can bear these costs—and so export activity is often portrayed as a decision made by individual firms largely on the basis of their total factor or labor productivity. However, firms cannot make this decision in a vacuum. This paper considers what it means for a firm to export: particularly, how the nature of exporting and characteristics of exporting firms vary across countries, and what implications that holds for economic policy formation.

The paper's primary contribution is to connect firm-level traits thought to incentivize exporting to national-level factors that may alter the productivity threshold at which firms find exporting a profitable or worthwhile business endeavor. Specifically in the arena of trade policy formation, it draws first on a body of research arguing that the array of preferences held, and political actions undertaken, by firms can influence policy outcomes, and suggestsFootnote 4 that special interest politics may provide a more robust explanation for systematic differences in trade policy across regime types than previous voter-driven mechanisms. Firms’ export orientation becomes a rough proxy for their preferences on trade, assuming that exporters generally are alike along certain characteristics.

Having identified several key traits of exporting firms drawn from the new-new trade theory literature, and borne out of empirical analysis of firms sampled in wealthy democracies, I then argue that the relationships between such traits—particularly productivity and innovation—and export orientation should be conditioned by domestic factors. This section develops a structural argument explaining how democratic political institutions incentivize better business climates and information provision for firms, maximizing the ability of productive firms to self-select into export markets. It also argues that innovation should more weakly predict export orientation in developing economies than it does in developed ones, focusing on alternative growth strategies employed at different stages of economic development.

In the empirical section of this paper I identify testable relationships between characteristics of firms and their export activity rooted in past literature. While I generally find support for these hypotheses using World Bank survey data from nearly one hundred countries, the strength of the relationships between firm-level traits and export orientation is highly contingent upon domestic context; that is, political regime type and level of economic development condition the degree to which productivity and innovation correlate with export activity.

Why exporters? Debates on determinants of trade policy

Democracies have long been understood to be different—broadly, more liberal—in their trade policy, an empirical fact that has generally been attributed to the presence of a voting public pushing for freer trade, somewhat counterbalanced by a protectionist special interest channel. Describing the decades prior to the United States’ major liberalization of trade beginning in 1934, Gilligan writes that American trade policy was essentially this: “import-competing interest groups asked for protection, [and] legislators gave it to them.”Footnote 5 This characterization fits into the classic narrative of “protection for sale,”Footnote 6 in which domestically-oriented business interests push for higher tariffs and other trade-restricting measures against the interests of the average consumer. And in turn, widespread trade liberalization, often coinciding with greater democratization in developing countries, has been frequently explained through a selectorate theory or median voter logic emphasizing the democratically-elected policymaker's need to provide public goods to satisfy at least a simple majority of their constituents.Footnote 7

Critically, this framework and the workhorse theories of trade underlying it, “assume a representative firm, at least within each industry,” generating a paradigm in which firms uniformly impose pressure upon the state for protectionist trade policy through lobbying efforts presumed to represent the cohesive interests of an entire industry.Footnote 8 Yet this stance is contradicted by a growing body of research displaying heterogeneity at the level of the firm along an array of characteristics including size, labor productivity, wages paid, skill intensity, number of products or services offered, etc. Across and within industries, variation in the characteristics of firms has become a key explanatory factor for the multitude of divergent preferences that firms as political actors hold, and for their participation in the policymaking sphere to advance those preferences. Increasingly, the systematic liberalization of trade policy in the United States—and in democracies more generally—has been attributed to the lobbying efforts of large and internationally-oriented firms more so than voters, for whom economic policy is often perceived as not salient or too complex.Footnote 9

One of the most significant distinctions political economists have drawn among firms is their export orientation, arguing that exporting firms hold different policy preferences than do their domestically-oriented counterparts; namely, they prefer greater openness and they engage more frequently and directly to influence policy.Footnote 10 In addition to corresponding to differences in policy preferences and political participation, firms’ export activity is also linked to particular traits; thus, while considerable evidence has been accumulated to suggest that exporting firms are functionally distinct from non-exporting ones, they have largely been characterized as being an extreme minority, an elite upper tier of large, productive, and highly innovative firms.Footnote 11 It has become a stylized fact, based off of US firm-level data, that “engaging in international trade is an exceedingly rare activity.”Footnote 12 In general, exporting firms advance different policy preferences than their domestically-oriented counterparts, and the way we tend to describe this former group conjures up a very specific profile of a limited body of corporations.

Unsurprisingly, recent work finds that although firms like this—large, incredibly successful, endowed with financial and organizational resources—are few in number, they have an outsized influence on government.Footnote 13 On the surface, it seems plausible that a small proportion of very large and influential firms pushing for free trade could hold more sway over policy than the much greater body of import-competing firms pushing for protection, thereby accounting for trade liberalization. However, for this story to help restore an explanation for regime-type differences in trade policy, it requires 1) that democracies either face more pressure from, or pay more attention to, pro-free-trade corporate interests than do nondemocracies on average, and 2) more to the point of this paper, that we know whether the archetype of the exporting firm—its traits, its preferences, its political activities—holds up in a broader context. Put simply, the characteristics that have come to define exporters across Western Europe and North American may not accurately portray those in non-democracies or industrializing markets, and there is not strong enough evidence that our core expectations about firms ring true across varied levels of political and economic development.

Until recently, firm-level data access limited scholars’ ability to make true cross-national comparisons, and many broad generalizations about firms’ characteristics, preferences, and behavior (such as are noted above) have been drawn from the population of firms operating in the United States and other Western democracies, for whom much fuller operating data were available. The literature has been dominated by single-country case studies focusing on the wealthiest and most technologically advanced nations in the world. Certainly, this is useful for gathering information about firms and economies dominating global trade, but it makes it hard to draw inferences that can be generalized to firms in less democratic or less developed settings—and if the average exporter is fundamentally different in an autocracy or a developing economy, this muddies our understanding of corporate special interests in setting economic policy, our expectations about the types of regulations exporters should prefer, or any number of inferences drawn under the assumption that exporters everywhere were generally alike.

A number of scholars have recently employed the cross-national firm-level data gathered by the World Bank Enterprise Surveys to advance arguments about the interplay between domestic political and economic institutions and firm-level characteristics, focusing predominantly on lobbying activity and perceptions of influence over the policymaking process.Footnote 14 Even as such work expands our body of knowledge on firm heterogeneity and its implications for trade, the general findings on export orientation rest on the assumption that exporters around the globe have something in common, that exporting firms worldwide look, feel, and behave the same way that the small proportion of superstar exporters of the United States do. It is therefore crucial that we return to some of the most robust predictors of export activity in these settings—notably, productivity and innovation—and put the relationships between particular firm-level traits and firms’ export orientation to a rigorous taking cross-national variation into account.

Why export?

Over the past few decades, economics and business outlets have published scores of academic studies on the relationship between firm characteristics and exporting behavior, in which scholars have conducted rigorous empirical examinations of firm-level data. On several of these relationships there is broad consensus: scholars generally agree that participation in export markets is positively correlated with productivity, size, greater innovativeness, more educated labor force, higher wages, better past sales performance, and greater capital intensity in production.Footnote 15 Focusing just on a few of the most theorized-about variables, in this wider sample of firms I still expect the general new-new trade theory tenets explaining export orientation to obtain:

NNTT Hypothesis. On average, size, productivity, and innovation should be positively correlated with the likelihood of a firm's activity in export markets.

None of these relationships is original or controversial: they are derived from past new-new trade theory literature, but require a test with a new sample; it may also provide some assurance that these data generally behave the way we expect them to, and the original findings that follow are not simply the result of measurement error. Where I do deviate from conventional expectations, though, is with regard to the interaction between these firm-level traits and national-level ones. There are theoretical reasons to expect exporters in certain types of countries to be less productive ex ante, and perhaps less innovative as well, and here I explore economic and political arguments that should condition the impacts of productivity and innovation on exporting.

Reassessing the role of productivity

Economists focusing on the importance of firm heterogeneity and its economic implications have exerted significant effort in analyzing differences in firms’ productivity levels, attempting to ascertain whether an exogenous decision to export can raise labor or factor productivity, or whether the decision to participate in export markets is endogenous to firms’ pre-existing higher levels of productivity. On the one hand, by expanding operations to an international arena, firms are exposed to greater competition, and engage more directly with global flows of information and technology, thus helping them to increase productivity levels at a higher rate immediately upon first exposure.Footnote 16 On the other, export operations are often associated with some degree of costliness, which less productive firms are not able to bear. Higher rates of productivity growth in the first year following entry into export markets indicate support for the proposition that firms begin exporting and then increase their productivity (learning), whereas an overall greater productivity differential pre-entry between firms who begin thereafter to export and those who do not indicates support for self-selection.

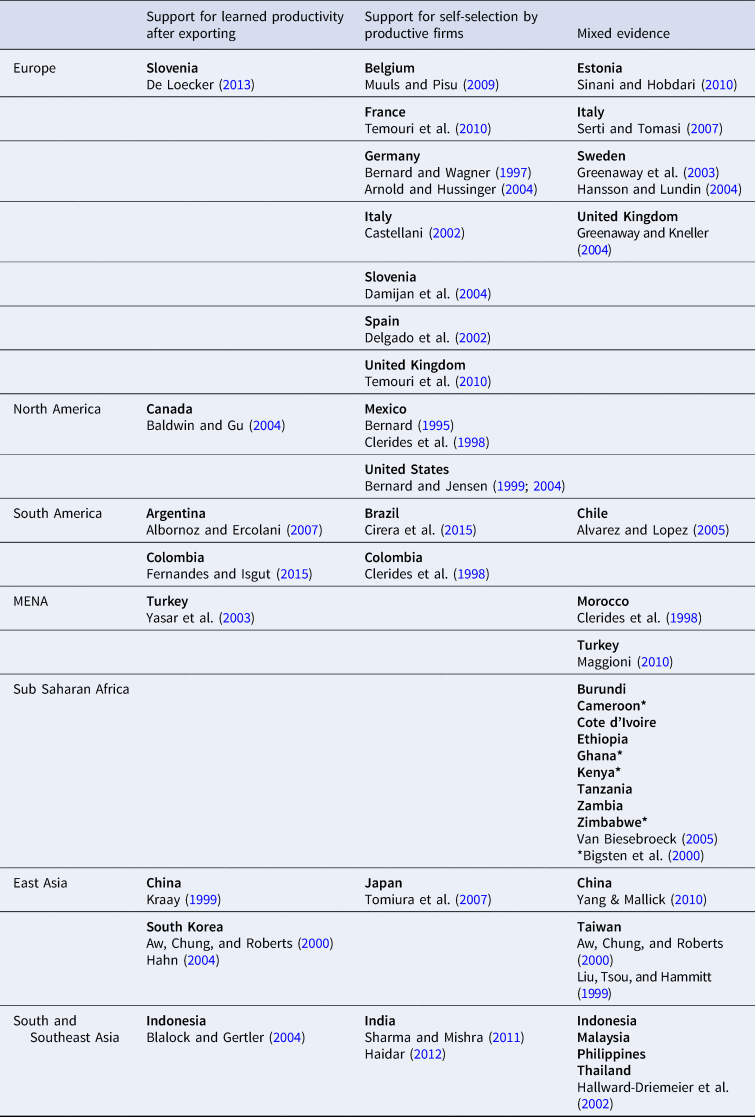

Table 1Footnote 17 indicates the economies in which scholars have conducted such studies, totaling approximately three dozen; I highlight here some major cross-national efforts in addition to several single-country case studies.

Table 1: Varied support for rival hypotheses depending on country studied

This table indicates that among most wealthy democracies in Western Europe and North America, the evidence largely supports self-selection into export markets, per the logic that the exporter premium supporting post-entry learning in terms of technology and resource acquisition is not large in the most advanced countries. Noting, though, that the World Bank Group has touted an export-driven development strategy such that exposure to international markets can improve the efficiency of manufacturers in less advanced economies, scholars have found stronger evidence of learning by exporting among exporters in Africa, South America, and parts of East and Southeast Asia. In short, our inferences change depending on the countries in which firms are sampled. Firm-level determinants of export market participation likely look different across domestic contexts. To put it more precisely: although productivity levels have been one of the key predictors of export orientation in our studies of firms in wealthy democracies to date, we may not expect them to predict export activity as strongly outside of that domestic context.

Theoretically, there are multiple lines of thought that would account for productive firms in democratic countries being able to self-select into export markets while firms in nondemocratic countries would be less able to do so. Here, we consider two schools of thought linking the structure of government, first, to incentives to regulate the business climate, and secondly, to incentives to provide information.

Democratic and autocratic governments clearly face different political pressures and employ different strategies to retain office: for democrats, public goods provision and welfare-maximizing policies boost support, while autocrats are incentivized to offer private goods to a smaller societal elite.Footnote 18 Where economic prosperity and gains from trade are a boon to politically accountable regimes, autocrats’ hold on power is actively threatened by the growth of a middle class,Footnote 19 and deeper integration within the global trade regime leads to calls for greater public works provision,Footnote 20 a tough demand of leaders who retain power by providing private and excludable goods. It is problematic to autocrats, then, that firm heterogeneity identifies an additional parameter of gains from trade,Footnote 21 or an additional way to provide public goods and the widespread economic gains that threaten autocratic rule.

Without the assumption of heterogeneity among firms, there is a group of domestic firms and a group of internationally-active exporting firms, where all domestic firms share some level of productivity that is not compatible with exporting, and all exporting firms share some static level of productivity that is. If a domestic firm were to enter export markets, it would by definition reflect that firm's productivity level having changed to the exporting level, and the shift of that firm into export markets would not change the average productivity level of either group. But if each firm has its own unique level of productivity and can select into and out of domestic or export markets, firms’ movement across markets shifts the average productivity of each group, maximizing an additional degree of efficiency.Footnote 22 The lower trade costs are, the greater these gains from trade. But it is unlikely that trade costs and the costs of firms’ entry into export markets are equally low across domestic contexts.

Autocratic leaders who are threatened by the political demands made by exporting firms or the pressure that a growing middle class could exert have an incentive to regulate market entry in such a way that ensures control over exporters, and that actively hinders productive firms’ ability to select into export markets. In this context, the complexification of market entry (via documents, procedures, time, and costs of doing business across borders) can be thought of as a form of rent-seeking behavior on the part of public officials.Footnote 23 As democracies reduce trade costs and simplify movement into export markets, they create climates that most closely resemble the aforementioned model's conditions maximizing allocative efficiency and increasing widespread gains from trade; but autocracies can do the opposite, complicating international trade, offering favors to politically-connected businesses, and making it hard for productive firms to enter export markets on their own merits.

A second—and compatible—view of the effect of political institutions on firms’ activity considers an information-based logic. Electorally-accountable regimes are incentivized to disseminate “policy-relevant” economic data, in essence providing information about their operations that allows the public to evaluate them, “affect[ing] the economic performance of market activities.”Footnote 24 By contrast, the likelihood of autocratic regime change increases with the provision of reliable information about the regime, especially via online platforms.Footnote 25 In essence, democracies implement market regulatory policies supporting productive firms’ autonomy to begin exporting, and they share information about it that helps firms better navigate the system. But nondemocracies implement more obstructive barriers to exporting and deliberately make it difficult to navigate or find information about the system that might improve economic performance. As such, I propose a hypothesis in which the effect of productivity on exporting is contingent upon political regime type:

Conditional productivity hypothesis. Productivity level should be more strongly (positively) associated with export activity in democracies than in non-democracies.

Reassessing the role of innovation

Much like the debate over self-selection versus learned productivity among exporting firms, the role of innovativeness has been dissected across single-country samples of manufacturing firms in developed economies across Western Europe.Footnote 26 Innovative firms may select into export markets by virtue of the effect that process innovation has on their productivity levels (although productivity may still be observed to have an independent effect on export orientation controlling for innovation), and exporting firms may learn and become more innovative from their activity in international markets.

Again, though, this assumes that the domestic contexts in which firms operate are comparable. It is perhaps instead the case that developing economies do not possess the same institutional infrastructure to incentivize the level of innovativeness that characterizes exporting firms in developed settings. Drawing on a resource-based view of the firm, performance is dictated in part by access to information, knowledge, and organizational processes,Footnote 27 all factors that would allow firms to innovate both products and processes. However, developing countries may simply lack the ability to acquire these resources or develop these capabilities to the same extent that firms in developed economies can.Footnote 28

Factors affecting firms’ ability (or inability) to innovate in developing countries are interrelated. First, developing countries are by definition, further from the “world technology frontier,” and tend not to adopt innovation-based strategies for growth.Footnote 29 Although this distance from the frontier suggests that returns from innovation could be very high, they generally go unrealized, as firms in developing settings have lower access to capital to engage in R&D and lower access to human capital necessary to complement any R&D spending in such a way as to translate these expenditures into better performance.Footnote 30

In countries further from the world technology frontier, firms are more likely to rely on existing managers rather than replacing them by selecting managers based on higher skill level, and the trend of high-skill emigration from developing countries suggests that this key resource is simply less available to firms in this domestic context.Footnote 31 Further, two-way traders have greater ability to innovate in developing countries, as the import of intermediate inputs may constitute direct acquisition of knowledge from productive and innovative exporters abroad,Footnote 32 but governments in developing countries have historically opposed trade reforms that would facilitate higher imports of intermediate inputs on the grounds of preserving their current account balance.Footnote 33

Stemming from different incentives and ability to innovate in developed versus developing countries, I argue:

Conditional innovation hypothesis. Innovativeness should be more strongly (positively) associated with export activity in middle- to high-income countries than in developing ones.

Data and empirics

The World Bank Group has conducted its Enterprise Surveys (WBES) among firms in approximately 150 countries since 2002, asking batteries of questions on production, sales, markets, labor force, finance, and innovation. As changes to the basic questionnaires and coding strategies, and inclusion of survey weights, occurred after 2005, WBES offers a dataset pooling observations for 286 country-years between 2006 and 2019, representing approximately 160,000 firms.Footnote 34

My dependent variable of interest, export orientation, centers around firms’ exporting activity, which I measure dichotomously. A value of zero represents firms who respond to the question “in [previous fiscal year], what percentage of this establishment's sales were direct exports?” with 0 percent, did not know, or refused to answer, and a value of 1 represents firms who responded to the same question with any value greater than 0.

Derived from previous literature on firm heterogeneity, independent variables of interest capture firms’ size, labor productivity, and levels of innovation. Firm size is measured by the variable employees, which is the logged number of permanent full-time employees from the past fiscal year. Firms report their total sales from the past fiscal year in Local Currency Units, which I standardize to USD using yearly average exchange rate data and divide by one million, generating the variable sales (millions USD). My productivity measure is generated by dividing this converted sales figure by the total number of permanent full-time employees (productivity is logged in the models given its skewed distribution, and firms reporting one million USD or greater value added per worker are excluded from the models). An alternative measure of productivity is included in the Appendix where a measure of firms’ total factor productivity (TFP) estimated by the World Bank is substituted into the same models in place of labor productivity. While the key results still obtain, the sample size is greatly reduced due to missingness on the variables that go into their more complex calculation.

In many rounds of the surveys, firm respondents are given an innovation module asking whether they have “introduced new or significantly improved products or services” or improved a process of production in the past three years, where a response of 1 indicates that they have, and 2 that they have not. I reverse the coding so that the “no” response receives a value of 0 for the innovation variable, and a score of 1 is assigned to firms who have recently developed or improved upon either a product or a process.

While the independent variables described here represent the most robust determinants of exporting activity, several other characteristics should be controlled for. The variable years in operation represents the number of years between the date the survey was conducted and the date with which the respondent answers that their establishment began operations. I also control for locational factors that might facilitate exporting through a binary variable capturing whether or not the firm is located the nation's capital. To account for possible use of industrial policy or central planning to help certain firms export, I include percent state-owned. In further analyses designed to shed some light on the mechanisms linking political regime and economic development to firm-level traits, I also account for firms’ belief that customs regulations are an obstacle to conducting business, their access to information via connection to the internet, and status as an importer. Given the irregular repetition of surveys within countries, I cannot meaningfully analyze any time-series dynamics, but I try to absorb other systematic sources of variation through country, year, and industry fixed effects based on two-digit Standard Industrial Classifications. Table 2 reports descriptive statistics on firm-level variables.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics

As indicated by the mean value of export orientation, firms’ participation in export markets is, on the whole, rare. Of the more than 160,000 firms surveyed in 144 countries between 2006 and 2019, just under 30,000 firms responded with a non-zero percentage of sales accounted for by direct exports. In the pooled sample, then, about 19 percent of firms could be classified as exporters—and this may be a high estimate due to the lower visibility of smaller domestic, and perhaps informal, firms. Broadly, data from the WBES comport with the stylized facts inferred primarily from US and European data: exporters do form a relatively small minority, less than one-fifth of firms sampled.

Yet this figure may strike readers as too high, given past characterizations of exporting as exceedingly rare behavior among the universe of firms. There are multiple ways to interpret this. First, and most cynically, the samples of firms captured by the WBES may be wholly unrepresentative of the universe of firms operating within each country—but I do not believe this to be the case. Given that many of the countries in this sample do not track or provide data on the entire population of firms operating within their borders like the United States, Canada, or some Western European countries do,Footnote 35 the opportunity to compare the WBES sample to countries’ full population of firms is limited. However, I have identified four countries in which reports on the full population of business operating in the country give a picture of the true percentage of exporters; table 3 compares with World Bank's estimates side-by-side with these calculations.

Table 3: Percent of exporting firms from World Bank sample compared to full population of firms

Offering coverage of firms in four distinct regions, these studies of the full population of firms identify 20.6 percent of Chilean firms as exporters between 1990–96,Footnote 36 an average of 4.6 percent in Ethiopia between 1996–2005,Footnote 37 47 percent in Malaysia in 1998,Footnote 38 and 21 percent in Spain between 2001–11.Footnote 39 These numbers map on relatively closely to the WBES proportions of about 21 percent in Chile, 7.3 percent in Ethiopia, 42.5 percent in Malaysia, and 20.8 percent in Spain. It is worth noting also that, while the estimates are far closer for Spain and Chile than Malaysia and Ethiopia, the WBES estimate for Ethiopia is high while its estimate for Malaysia is low. Although not incontrovertible, this should at least somewhat mitigate the concern that the World Bank's stratified sampling technique drastically mischaracterizes the body of firms in operation.

More likely, it may be the case that exporting is indeed the purview of relatively large, productive, and innovative firms, but that the threshold for what constitutes large, productive, or innovative enough is not as high in developing countries or autocracies as it is in the United States or Western Europe. Put another way, it is possible that the firm-level characteristics that correlate with exporting in the developed democracies previously sampled do not correlate as strongly with export orientation in a larger, more diverse sample.

In table 4, I test the basic NNTT hypothesis through logistic regressions with differing specifications. These highlight the consistency of certain key relationships despite missingness on different variables altering the sample size. Consistent with past studies of exporters, I find positive associations between a firm's propensity to export and its size, labor productivity, and innovativeness. Model 1 shows a sparse specification allowing for the greatest sample size, while models 2 and 3 add in control variables for location, years active, state ownership, and import activity; these obviously remove some omitted variable bias present in model 1, but, as model 2 indicates, drop a lot of country-years and, as seen in model 3, more than half the observations of the former two models.

Table 4: Determinants of export orientation—firm-level multiple regressions

Logistic regression with industry, country, and year fixed effects; survey weights employed.* p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

In the pooled samples used here there is consistent support for the NNTT hypothesis: larger, more productive, and more innovative firms are more likely to export. For instance, a one-standard deviation increase in logged number of employees makes firms approximately 12–13 percent more likely to export, a one-standard deviation increase in logged productivity corresponds to a more than 7 percent increase in the likelihood of exporting, and firms that have introduced a new service, product, or process to the market are nearly twice as likely to export.Footnote 40 Table A1 reports models estimated using the World Bank's estimated total factor productivity ratio.

As indicated in the conditional productivity and innovation hypotheses, though, there are theoretical reasons to believe that the relationship between these firm-level traits and firms’ participation in export markets may not be constant across domestic contexts, which argues for pooled models that directly account for critical cross-national differences. To be clear, the models above constitute strong support for the conventional wisdom regarding the types of firms that export, but taking country-level factors into account may explain why the profiles of exporting firms vary so widely across countries.

I have previously highlighted reasons to anticipate different relationships between these traits and export orientation in advanced democracies than in developing countries or autocracies. To get more directly at these conditional effects indicated in the two novel hypotheses, I present additional firm-level regressions in table 5 split into subsamples based on regime type and level of economic development.

Table 5: Firm-level determinants of export orientation in different domestic contexts

Logistic regression with industry, country, and year fixed effects; survey weights employed.

* p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

The two conditional hypotheses focus on the substantive effects of innovation and productivity, respectively, across domestic settings. Looking first at the conditional productivity hypothesis, the differential effect of labor productivity between firms in different political-economic contexts is stark: per model 4.1, a logged unit increase in labor productivity makes firms in democracies,Footnote 41 on average, about 10 percent more likely to export. In nondemocratic settings, though, the effect is deeply attenuated, with model 4.2 suggesting only about a 4 percent increase. Looking more closely at the substantive effects predicted by these two models, figures 1a and 1b show average marginal effects of productivity on the likelihood of exporting in democracies and nondemocracies, respectively.

Figure 1: (a) Marginal Effect of Productivity on Exporting: Democracies; (b) Marginal Effect of Productivity on Exporting: Autocracies

The steep nonlinear slope in figure 1a is what conventional wisdom expects, largely based on single-country case studies from industrialized democracies. When considering a pooled sample of firms in nondemocratic countries, it is not the case that exclusively the most productive export, or that productivity is a robust predictor of export orientation. Taking into consideration the ways that political and economic institutions may jointly affect firm performance, models 4.5 and 4.7 highlight statistically significant positive correlations between labor productivity and export orientation across differing levels of development (granted, the relationship weakens in developing democracies); model 4.6 is remarkable in that it shows no statistically significant association between productivity and the likelihood of exporting in middle- to high-income autocracies, including Kazakhstan, Malaysia, and Turkey.

This finding may shed some light on the proposed causal mechanisms underpinning the conditional productivity hypothesis. Encapsulating the argument that autocrats complicate firms’ self-selection into export markets, a series of difference in means tests presented in the Appendix (table A3a) indicate that exporters in nondemocracies feel customs and trade regulations are a greater obstacle to their operations than exporters in democracies; encompassing the argument about access to information across regime types, a difference in means test also shows significantly lower access to high-speed internet among exporting firms in nondemocracies. With (slightly) less access to transparent information about government policies and markets, it stands to reason that exporting firms in nondemocracies are not set up to maximize their productivity.

Turning now to the conditional innovation hypothesis, the relationship between innovating and exporting is subject to change based on the domestic economic context in which firms operate. In models 4.3 and 4.4, splitting firms between those in developed economies and those in developing economies shows that size, productivity, and innovativeness are all significant predictors of export activity. However, while new-new trade theory intuitions about the characteristics of exporters hold up, these results indicate that the framework does not necessarily apply in the same ways under different levels of economic development.Footnote 42 Figures 2a and 2b show two statistically significant, positive relationships between innovating and exporting, but of different magnitudes. Although innovating still significantly increases the likelihood of a firm in a developing country exporting, the relationship is not nearly as strong in settings further from the world technology frontier.

Figure 2: (a) Marginal Effects of Innovation on Exporting: Developed Countries; (b) Marginal Effects of Innovation on Exporting: Developing Countries

These results are reinforced by models 4.5–4.8, in which the substantive effects of innovation generally attenuate for both developing democracies and developing autocracies (4.7 and 4.8, respectively) compared to similar political regimes in developed economies (seen in 4.5 and 4.6). This attenuation is particularly dramatic between developed democracies (4.5) and developing democracies (4.7), though, more than halving the magnitude of the relationship between innovation and export activity. Returning to the difference of means tests in the Appendix (table A3b), exporting firms in developed countries are significantly more likely to import intermediate inputs, or function as two-way traders, than exporters in developing countries. Since intermediate input importing is a major form of learning to innovate, this comports with theoretical expectations that lower innovation among exporters in developing economies may be a product of governments reluctant to jeopardize their current account by liberalizing trade in key sectors.

Conclusion

Systematic variation in trade policy, particularly between democratic and nondemocratic regimes, had conventionally been explained by arguments resting on an electoral channel or individual-level preferences, but increasingly a body of work focusing on firms as political actors has provided an alternative explanation in special interest politics. New-new trade theory arguments rely heavily on the premise that firms that export are functionally different than those that do not, and their distinct profile leads them to hold, and act upon, different political preferences than their import-competing counterparts. Many of the most influential works study the population of firms operating in the United States, Japan, or other economically advanced democracies across Western Europe, and draw inferences from there on what characteristics define the “typical” exporter.

This paper has analyzed samples of firms spanning nearly one hundred countries, many of which are at lower levels of economic and political development, and argued that the traits scholars have traditionally thought to embody exporters—the largest, most productive, highly innovative firms—actually vary considerably among exporters across different national contexts. While analysis of the pooled sample confirms the basic established relationships between export orientation and size, productivity, and innovation in a more global sample, it also highlights domestic factors that condition these relationships, particularly in less developed and less democratic countries.

If we are to leverage firm-level heterogeneity—and especially variation between exporting and non-exporting firms—to explain key phenomena in trade policy and political economy more broadly, it is crucial to our theorizing not to over-generalize. While exporters worldwide do seem to be larger, more productive, and more innovative on the whole, domestic context plays an important role in the strength of these relationships. Innovation is a weaker predictor of export orientation for firms in developing economies, which tend to be further from the cutting edge of technological developments. More importantly, when considering firms across different political regimes, labor productivity—one of the most theorized-about indicators of exporting—is only a statistically significant predictor of exporting in democracies.

Taken together, these cursory findings open new lines of inquiry, especially regarding the causal processes through which certain political or economic institutions may strengthen or dampen the general relationships between firm-level traits and behavior. Secondly, they should prompt us to reconsider whether (in the absence of explicit survey responses on preferred policies) we can ascribe pro-free-trade preferences to exporters universally, to productive firms, or to productive exporters—or if there are other qualifiers to consider.

Appendix

Table A3a: Difference of means test for conditional productivity hypothesis—customs obstacles and information access (via internet) among exporting firms across regimes

Table A3b: Difference of means test for conditional innovation hypothesis – two-way trading among exporters across levels of economic development

Table A4: Key results from country-by-country regressions indicating greater predictive power for productivity and innovation in wealthy democracies.