Introduction

Labor and environmental provisions in preferential trade agreements (PTAs) have become stricter over the yearsFootnote 1 and the push for enforcing those clauses by means of sanctions has been gaining momentum.Footnote 2 In trying to understand why nontrade issues (NTIs) in PTAs are getting stronger, recent works have focused on the strength of lobbying by import-competing firms, NGOs, and trade unions.Footnote 3 However, a fuller picture requires understanding of the patterns of lobbying by leading protrade business interests on nontrade issues (NTIs) in PTAs.Footnote 4 Large, protrade, and highly integrated firms and industry associations lobby hard on trade and can therefore work as a powerful force in favor or against the promotion of sustainable development objectives in trade deals. Thus, the study of what internationally active firms want from NTIs in PTAs is not trivial, not least because of the global trade and environmental/labor governance implications of ever-stronger environmental and labor provisions in PTAs.Footnote 5 This article seeks to offer a contribution to that debate by focusing on how business interests position themselves on sanctions-based enforcement of labor and environmental provisions in PTAs over the years. Sanctions are an important component to assess the strength of a treaty's dispute settlement.Footnote 6 They are, however, a highly contentious topic to protrade firms and business associations. For instance, US and EU protrade interests were all adamantly against linking trade to labor and environment in a manner possibly leading to sanctions (fines or withdraw of tariff preferences) in the early 1990s. Still, in recent years protrade firms/business associations from the United States (i.e., Intel, Business Roundtable) have explicitly supported sanctions to enforce NTIs,Footnote 7 while protrade interests in the European Union remained opposed to such instruments.Footnote 8 The increase/decrease in the levels of export-dependence and global value chain (GVC) integration does not suffice to fully account for those patterns of change/continuity, nor do explanations centered on recent antiglobalization sentiments.

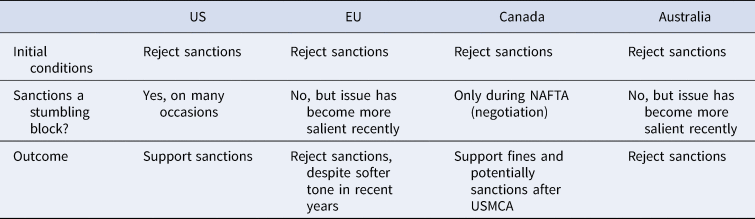

Bearing the preceding in mind, why do protrade firms/associations based in certain countries end up explicitly supporting the inclusion of labor and environmental provisions in PTAs in a manner possibly leading to sanctions? When will they change their views? I argue that the answer to those questions depend to a large extent on how past experiences affect a firm's/association's perception of losses. My argument is that difficulty to approve or negotiate trade agreements due to issues pertaining to the enforcement of labor and/or environmental provisions in past PTAs create incentives for protrade business interests to progressively change their position on the enforcement of those provisions over the years. I probe that argument using two paired comparisons (EU–US, Australia–Canada) of the position of protrade firms/business associations on labor and environmental provisions in PTAs between 1993 and 2019. My analysis attests the overall plausibility of my argument, although some findings add even more nuance to my initial expectations. This article responds to recent calls for more studies on the relation between nontrade issues and protrade preferences,Footnote 9 especially in a context of growing politicization of trade. This article then reinforces that business lobbying on NTIs, in addition to being influenced by exogenous economic preferences, is affected by past experiences. The results offer new insights into how business interests lobby NTIs and can shed new light on the politics of the design of sustainable development provisions in PTAs.

Besides this introduction, this article is organized as follows: First, I review the literature, then I present my theoretical argument and the methods. I then analyze the position of EU, US, Canadian, and Australian protrade firms/associations on trade–labor–environment linkage. Finally, I draw a few conclusions and avenues for further research.

What Does the Literature Say?

Business lobbying can affect the design of international institutionsFootnote 10 and recent works have reasserted that large, protrade firms are often the ones lobbying harder on trade due to their growing integration to value chains,Footnote 11 product differentiation,Footnote 12 and/or fears of foreign discrimination.Footnote 13 However, amid existing works on the link between trade and sustainable development, few have given due attention to the political activities of protrade business interests.Footnote 14 The ones that do still fall short of accounting for change in the positions and/or preferences of those interests over the years. Why do protrade firms/associations change views on how they want the enforcement of sustainable development provisions in PTAs to be? I here present three possibilities based on the literature: (1) classic export-dependence, (2) GVC-integration, and (3) the rise of protectionist sentiments in recent years.

The existing literature often expects protrade interests to be hesitant vis-à-vis the possibility of including nontrade objectives in economic agreements.Footnote 15 Lechner (Reference Lechner2016), for instance, argues that exporters often want trade agreements to be free from issues that could potentially lead to an impasse in negotiations. In addition, flexibility provisions in PTAs—which may include stronger labor and environmental provisions as a form of ex post safeguard—are seen by exporters as an inefficient response to the risk they face in international trade,Footnote 16 especially if sanctions are part of the picture.Footnote 17 Based on that, one could hypothesize that growing export-dependence leads to growing opposition of firms/associations against strong trade–labor–environment linkage in PTAs. However, that hypothesis does not seem to explain a key juncture for US and EU business interests in recent years. The European Union and the United States negotiated an agreement with South Korea at roughly the same time. But while US-based firms/associations operating in the manufacturing sector (i.e., the National Association of Manufacturers) changed their position on the link between trade and labor/environment in US PTAs during the time the US–Korea deal was negotiated,Footnote 18 EU-based firms/associations operating in the manufacturing sector did not.Footnote 19 That happened despite the fact that, at around the time the US–Korea PTA negotiations and ratification took place (2005–11), the level of export-dependenceFootnote 20 of US firms/associations in the manufacturing sector varied little vis-à-vis the start of the negotiations (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Export-dependence of the US and EU manufacturing sector in the bilateral trade with Korea (% US/EU GDP). Source: OECD TiVA dataset.

As pertains to GVC integration, Poletti, Sicurelli, and Yildirim (Reference Poletti, Sicurelli and Yildirim2020) find that labor and environmental standards can increase the variable costs of GVC-integrated firms (vertically integrated or otherwise), which would therefore oppose sustainable development provisions in PTAs. From the perspective of the authors’ argument, the very support of GVC-integrated firms to trade and sustainable development provisions in US PTAs would seem counterintuitive. However, Lechner (Reference Lechner2018) argues that labor and environmental provisions in PTAs may benefit highly integrated firms in high-skilled and least polluting sectors, which might therefore lobby for stronger such provisions over the years as their integration to value chains increase. Malesky and Mosley (Reference Malesky and Mosley2018) also consider that GVC integration may incentivize firms in some sectors to promote labor rights along the supply chain so to achieve greater markups. Thus, one could hypothesize that growing GVC integration in certain low-skilled industries, such as the textile/apparel sector,Footnote 21 should lead to stronger lobbying against labor provisions in PTAs. Based on that, the gross imports of intermediate textiles and apparel products from Asia-Pacific countries (the frontier of EU and US PTA expansion) seen in Figure 2 would suggest a strengthening in lobbying against NTIs across Atlantic in recent years. In reality, however, while the American Apparel and Footwear Association (AAFA) has been supportive of strong labor commitments in US PTAs with Asian countries after 2008,Footnote 22 the European Branded Clothing Alliance (EBCA) remained against the inclusion of sanctions in the sustainable development chapters of EU PTAs in recent years.Footnote 23 Following that same rationale, the decreasing outward FDI Australia's manufacturing sector (in average low-skilledFootnote 24, Footnote 25) does not correlate with the recalcitrant opposition of manufacturing firms to labor provisions in Australian PTAs (Figure 3).Footnote 26

Figure 2: Gross imports of intermediate products from Asia-Pacific countries (APEC) in the textiles and apparel sector (million USD). Source: OECD TiVA.

Figure 3: Total outward FDI in Australia's manufacturing sector (million AUD). Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Finally, one could argue that the recent antiglobalization sentiment led to increasing attention and support to nontrade issues,Footnote 27 and that this incentivized firms/business associations to shift positions and publicly promote themselves as supporters of sustainable development provisions in PTAs. Curran and Eckhardt (Reference Curran and Eckhardt2020) propose that multinational corporations (MNCs) may deploy sustainability initiatives to counter rising protectionism in recent years. Although it is plausible that protrade business interests will expand their voluntary initiatives of social and environmental responsibility in times of backlash against globalization, those interests are unlikely to give in to sanctions to achieve those objectives. Protrade business interests in the European Union, for instance, did not substantively relax their positions against the use of sanctions to enforce sustainable development objectives in PTAs in recent years.Footnote 28 Moreover, some US business associations that nowadays publicly support trade–labor–environmental linkage still mostly rejected the possibility of sanctions in US PTAs in the late 1990s/early 2000s,Footnote 29 when the United States was in the midst of an earlier wave of antiglobalization sentiment. All in all, I contend that the literature fails to fully account for the change/continuity in the position of firms/industry associations because (1) it lacks an explanation of the specific incentives for protrade business interests to change their position on the use of sanctions in labor and environmental provisions in PTAs. Besides, (2) the literature fails to fully account for the role of endogenous variables (i.e., policy learning after policy failures) to explain across-time change.

The Argument: Why and When Will Business Interests Shift Positions?

Regulations? Yes… Sanctions? No.

The position of protrade business interests on the link between trade and sustainable development is, as indicated by Lechner (Reference Lechner2018) and Malesky and Mosley (Reference Malesky and Mosley2018), nuanced. Works on firms’ support for stronger sustainability regulations lend support to that affirmation.Footnote 30 At the same time, however, those works underscore that such support is dependent upon the level of stringency of the regulation at hand. Bearing that in mind, the starting point of my argument is that the inclusion of sanctions to enforce labor and environmental provisions in PTAs goes against the economic preferences of protrade business interests. For one, autonomous exporters want to assure some harmonization of labor and environmental regulations to limit “unfair trade” while still supporting trade liberalization. However, fines/sanctions may have negative effects on firms’ exports, are often argued to be ineffective, and can put initiatives of trade liberalization at risk due to opposition by trade partners.Footnote 31 Therefore, they are seen as not “worth the pain.”Footnote 32 Also, sanctions also generate a context of uncertainty to which GVC-integrated firms are highly sensitive.Footnote 33 If labor and environmental dispute settlement allows for the use of sanctions, GVC-integrated firms fear that those provisions will be misused and that sanctions will be triggered and lead to unplanned increase in production costs along the supply chain. Even if labor and environmental provisions are not likely to be enforced, exporters and multinationals are afraid of the uncertainties and potential unintended consequences associated with the inclusion of sanctions or fines to enforce those provisions. Take, for instance, the example of the Business Council of Canada, which reaffirmed that they were against linking trade sanctions to nontrade issues “however remote” the possibility of sanctions might be.Footnote 34 And although vertical integration helps solve hold-up problems among firms in the value chain, vertically integrated companies are still subject to third parties launching dispute settlement against them due to alleged breaches of the labor and environmental provisions of a PTA.

Why Do Protrade Business Interests Soften Their Opposition to Sanctions?

Proponents of stronger dispute settlement mechanisms to enforce labor and environmental provisions in PTAs may be benefited by the volatility-reducing properties of PTAsFootnote 35 but will tend to oppose a trade deal that does not meet their expectations. Those groups, which include import-competing firms, NGOs, and trade unions, have shown their ability to mobilize to achieve their objectives in trade.Footnote 36 In turn, despite the costs of using sanctions to enforce nontrade issues in PTAs, it seems fair to assume that protrade firms and business associations prefer “a bad [trade] deal than no deal.”Footnote 37 In other words, when faced with the choice of acquiescing to stronger labor and environmental provisions in PTAs or potentially face a trade deadlock, protrade firms/associations will opt in favor of the former. Even then, protrade business interests might support/acquiesce to sanctions only temporarily and go back to a no-sanctions position after a contentious PTA is approved. When will they stick to a new position? Although some works in the international political economy (IPE) field have explored how past experiences may affect the design of international institutions,Footnote 38 the IPE literature often assumes (implicitly or explicitly) that the preferences of domestic interests are fixed.Footnote 39 From that perspective, changes in positions are temporary and the result of a short-term strategic calculus by firms. To understand when firms systematically change their positions and/or preferences on labor and environmental provisions in PTAs, we need to understand when they will change their mid- to long-term assessment of gains and losses.

Protrade business interests are constantly assessing their propensity of gains and losses (e.g., trade deadlocks). That assessment may occur on an ad hoc basis and lead to temporary shifts in position, but the greater the number and significance of the experiences acquired over the years telling business interests that not linking trade to labor and environment in a manner possibly leading to sanctions can lead to trade deadlocks, the greater the likelihood that protrade business interests will shift their mid- to long-term assessment of gains and losses. That change can be seen from the perspective of bounded rationality, as firms use previous experiences to fill in decision-making gaps, but it can also be seen from the perspective of rational anticipation of reactions, as done in this article: firms constantly assess their strategic options and experience-based learning help them project the cost-benefit of changing their positions. As Peter MayFootnote 40 has cogently argued, there are multiple forms of learning, and in this article I focus primarily on “political learning”: lessons about political processes and prospects and about the political feasibility of policy instruments. Political learning is not haphazard and may eventually lead to a more profound change (“social learning”). Based on that, the changes in public positions explored in this article can be seen as a baseline and may point to deeper changes in economic preferences down the road. Political learning is more than a one-off change in strategic calculus and points to a medium to long-term change in the prospects of gains and losses. In other words, the more protrade business interests obtain experience that failing to link trade to labor and environment in a manner possibly leading to sanctions can trigger trade deadlocks, the more likely they should be to shift their positions on the issue. That argument rests on a few assumptions. Firstly, firms are always seeking to learn from previous experiences but learning is more likely to be triggered after moments of (imminent) policy failure. Secondly, firms are able to make a fair assessment of the increased or reduced propensity of future deadlocks based on past experiences.

Why Do Protrade Business Interests Openly Support Sanctions?

Saying that protrade interests will learn to not oppose sanctions is certainly not the same as saying that they will explicitly support sanctions. Instead, they may decide to avoid making any commitments on nontrade issues in PTAs. This could lead to a reduced number of public submissions explicitly committing on nontrade issues in PTAs. At the same time, however, participation in sustainable development initiatives can be seen as an indicator of a firms’ willingness to undertake socially and environmentally positive behaviorFootnote 41 and can lead to price premiums.Footnote 42 If protrade firms/associations learn from previous experiences that (1) opposition against the inclusion of sanctions to enforce trade–labor–environmental linkage is unfeasible and can lead to reputational costs and (2) that sanctions will be part of a deal independently on whether or not they decide to commit on those issues, they may progressively decide to explicitly promote nontrade issues in PTAs (even if sanctions are part of the equation) so to send a positive signal to buyers that they are committed to sustainable development. In sum:

Hypothesis: The more often the debate surrounding the use of sanctions to enforce the labor and environmental provisions of PTAs becomes a stumbling block in the negotiations/ratification of a country's trade deals, the greater the support for the use of sanctions to enforce labor and environmental provisions in PTAs by protrade firms/associations based in that country.

Methods

In this article, I do a paired comparison of EU and US, Canadian and Australian protrade business interests. Those cases have similarities that allow me to control for theoretically/empirically relevant variables that could potentially influence my analysis. For instance, Australia and Canada have similar electoral systems, variables that could impact how economic interests position themselves on NTIs.Footnote 43 In general, the players under analysis are strongly integrated to the global economy,Footnote 44 have a diversified economy,Footnote 45 and a diverse set of trade partners. The paired cases (EU–US, Australia–Canada) also have comparable levels of parliamentary scrutiny of the trade policy-making process.Footnote 46 The countries/bloc in each paired comparison share similar power levels, as measured by their GDP. The cases also mimic the overall support for trade in advanced liberal economies, although that support has shrunk lately due to growing antiglobalization sentiment.Footnote 47, Footnote 48 Bearing all the preceding in mind, each set of paired cases follow first and foremost a most similar strategy.Footnote 49

But what can the selected cases tell us about a larger population? Firstly, the United States and the European Union are powerful trade actors and hubs from where the design of PTAs is copied.Footnote 50 Thus, they can be considered influential cases.Footnote 51 Furthermore, the two pairs of selected cases involve countries from the Atlantic and the Pacific, with different institutional settings, distinct power levels, and distinct approaches to linking trade and environment/labor. The selected cases also offer variation in the number of trade agreements negotiated and capture well the trend toward North-South PTAs over the years.Footnote 52 The cases selected offer variation in the number and strength on nontrade issues in PTAs over the years.Footnote 53 Therefore, if the selection of the United States and the European Union is in part justified by their position as “influential cases,” the selection of Australia and Canada adds more variation to the mix, allowing the paired cases to be more “representative in the minimal sense of representing the full variation of the population” (protrade business interests based in advanced liberal economies).Footnote 54 One could argue that the United States and Canada are exceptional given their shared NAFTA experience, something that could limit the external validity of the argument. However, one could also affirm that NAFTA was simply “ahead of its time” and that we may see conditions leading to a similar level of politicization of the labor and environmental provisions of NAFTA in other countries over the years. In view of that, I contend that the selected cases offer a good compromise between (1) assuring variation in the independent value (IV) and dependent value (DV), (2) assuring some initial prospects of external validity, and (3) meeting the need to control for key idiosyncratic characteristics of the selected cases in (4) a small-n setting.

How do I select the firms/business associations analyzed in this article? I cast a wide net when searching for protrade firms/associations and their positions, which I obtain primarily by means of public submissions. Public submissions are a form of outside lobbying that allows me to shed light on the political activity of business interests. I only select public statements in which firms/associations explicitly position themselves on nontrade issues. Those sources are complemented and triangulated using specialized and mainstream news (Agence Europe, Inside US Trade, and NexisUni platform) and selected interviewsFootnote 55 (Table 1), besides the existing literature. A key challenge here is that the preferences of individual firms and industry associations for trade may differ.Footnote 56 However, I assume that the position of business associations will be dominated by the protrade preferences of large, GVC-integrated firms that lobby hard in favor of trade liberalization. That assumption seems plausible as business associations often have a protrade stance in trade negotiations.Footnote 57 Moreover, protrade firms are more likely to form coalitions due to stronger political action than antitrade firms.Footnote 58 And even if individual firms decide to lobby on their own if intraindustry cleavages arise, their public position would still be captured by a careful screening of public submissions across and within each selected case.

Table 1: List of interviews

How do I go about probing my hypothesis? My DV has three values: (1) rejection of suspension of tariff treatment and/or fines, (2) support of fines, (3) support of suspension of tariff preferences. I treat my DV as an ordinal variable. Experience shows that firms tend to support fines (a monetary penalty) before supporting trade sanctions (suspension of preferential tariff treatment).Footnote 59 Thus, from the perspective of firms/associations there seems to be a hierarchy between “trade sanctions” and “fines.” As a measure of my IV, I rely on my knowledge of the individual PTAs to define whether enforcement of labor and environmental provisions was a stumbling block in the negotiation and/or ratification of the trade agreements. I cross-validate my conclusions with my interviewees. To probe the plausibility of my hypothesis, I follow a two-step process. First, I test for whether firm/business associations’ positions are congruent with my initial expectations. As a second step, I seek to probe the causal link between the difficulty of the negotiation/ratification of a PTA and change in firms and associations’ positions. To do so, I first look for direct and explicit references by protrade firms/associations linking the need to address issues pertaining to labor and environment to the feasibility of new trade initiatives during the 1993–2019 period. Whenever those direct and explicit references are not available, I look for a correlation between (1) the timing of the difficult negotiation/ratification of a PTA and (2) greater willingness, by protrade firms/associations, to discuss stronger labor and environmental provisions in PTAs. I would expect to see a progressive process of change as political learning sets in and thus temporary backtracking is not per se counterintuitive (firms engage in ad hoc change of strategies before a more substantive reassessment of mid- to long-term prospects of gains and losses take place due to political learning).

Paired Comparison I

European Union

During the 1990s and 2000s, nontrade issues in EU trade agreements were not a major source of contention. For the sake of “policy coherence,”Footnote 60 the EU Commission promoted labor provisions in EU trade deals in the late 1990s even if mobilization for such clauses was low. EU large exporters and multinationals, in turn, were rather silent in that period as the European Commission was not promoting sustainable provisions that were binding or subject to dispute settlement. On the flipside, EU associations of large protrade firms such as the Foreign Trade Association (FTA) and the Union of Industrial and Employers’ Confederations of Europe (UNICE) were much more focused on opposing trade-labor linkage at the multilateral trade level, where the possibility of using sanctions to enforce labor rights in trade policies was more pronounced. There, EU protrade interests openly positioned themselves against trade-labor linkage in a manner possibly leading to sanctions during the 1990s. In 1999, UNICE affirmed that it “does not accept the rationale behind … moves to use trade sanctions to achieve social policy objectives.”Footnote 61, Footnote 62

The level of contention of labor and environmental provisions in EU bilateral trade agreements remained quite low during the early 2000s, to the extent that some business interests all but ignored the issue.Footnote 63 Even after the release of the much criticized Global Europe strategy (2006), when the European Union introduced new obligations related to labor and environment in its “new generation” PTAs, groups critical of the new EU strategy were divided and their mobilization did not suffice to really put new EU PTAs at risk.Footnote 64 Throughout that period, EU protrade firms remained steadfastly against sanctions and fines to enforce the trade and sustainable development chapters (TSD) of EU PTAs. Recalling the years 2005–6, an EU business representative mentioned that for the business community “it was fine” if the commission linked trade to sustainable development, as long as “we had a good deal and provided that it is not going to stop the machine … as long as it is not subject to sanctions or fines, business is not going against it.”Footnote 65 The Colombia PTA highlighted that labor provisions in trade deals can become salient, but that deal was not put under real danger in virtue of issues pertaining to sustainable development. As such, BusinessEurope remained against the use of sanctions or fines to enforce labor and environmental provisions in EU PTAs.Footnote 66 Other leading business associations also rejected a sanctions approach (Table 2).Footnote 67

Table 2: EU PTAs and sustainable development

In May 2015, during the negotiation of the TTIP, BusinessEurope affirmed that it supported the European Union's “soft pressure” approach instead of the United States’ stronger provisions.Footnote 68 To the extent that EU trade agreements have been getting more contentious since the early 2010s, especially after the TTIP and CETA negotiations, EU protrade interests such as the FTA have already demonstrated willingness to debate the merits of a reform in the sustainable development provisions in EU PTAsFootnote 69 in anticipation to the possibility of a trade deadlock in the future. During the TTIP negotiation, in turn, one could notice that BusinessEurope was rather “soft-spoken” in its opposition against the US sanction-based approach, asking for a “balance” between the US and EU approaches.Footnote 70 That change, however, was not sufficient to trigger a deeper change in the position of EU protrade actors, which still remain opposed to sanctions and fines. The less stringent and more “soft-spoken” opposition of EU protrade associations against sanctions in recent years may point to a growing recognition of salience of nontrade issues in EU PTAs, as attested by the recent push for stronger sustainable development provisions in EU PTAs by France and the Netherlands.Footnote 71 The softened language of EU firms and the recalcitrant opposition to sanctions indicate that they know that NTIs matter, but have not yet acquired the political learning that sanctions are a necessary condition to the success of future EU trade deals. That can be for two reasons: (1) protrade interests expect that in the future the consensual EU decisions rules will save the dayFootnote 72 or (2) they anticipate that the difficulties in the negotiations of recent PTAs were not directly connected to the issue of sanctions to enforce PTAs (and instead were connected to broader antiglobalization sentiments). They may therefore seek concessions on other fronts before moving on to relaxing their views on sanctions.

United States

US protrade interests were strongly against trade–labor–environment linkage in the United states during most of the 1990s. In 1993, the Business Roundtable and the US Chamber of Commerce underscored that “[the proposal of linking trade to labor and environment] threatens to create a new, politically unaccountable bureaucracy” and characterized trade sanctions as “unnecessary” and “counterproductive.”Footnote 73 However, differently from the European Union, trade–labor–environment linkage in the United States has been a key topic of contention during the negotiation of NAFTA and greatly increased the prospects of a trade deadlock. Therefore, the US Trade Representative (USTR) recognized in a cabinet meeting in 1993 that NAFTA was not likely to succeed without the possibility of sanctions to enforce its labor and environmental provisions.Footnote 74 Although large firms temporarily acquiesced to NAFTA's side deals,Footnote 75 in 1997 the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) underscored that “it is our strong recommendation that the fast track legislative package includes some guiding language suggesting the inappropriate nature of using unilateral sanctions for non-trade purposes.”Footnote 76 NAFTA did not immediately lead to political learning that could introduce a systematic change in the position of firms.

Labor and environmental issues were a major topic of contention not only during the 1993 NAFTA debate but also during the 1997 fast-track debate.Footnote 77,Footnote 78 As a matter of fact, the 1997 fast-track bill was eventually derailed after an unprecedented lobbying effort by labor unions and their allies.Footnote 79 A key topic of discussion during the 1997 fast-track debate was the perceived weakness of NAFTA's environmental and labor side agreements.Footnote 80,Footnote 81 In line with what I would expect, after fast-track was put on hold in 1997 NAM and other business coalitions showed willingness to discuss issues related to labor and environment in trade to avoid future trade deadlocks.Footnote 82 In result, in January and February 2001, the Business Roundtable, Emergency Committee for American Trade (ECAT) and General Motors signaled their openness to having the trade agreement with Chile (2001) include labor and environmental clauses in a manner possibly leading to fines, explicitly underscoring that dealing with those issues was necessary to avoid trade deadlocks along the lines of the fast-track fiasco of 1997.Footnote 83 Political learning started to set in. Still, many other leading business associations such as the US Chamber of Commerce remained against strong trade–labor–environmental linkage and even the Business Roundtable was internally divided.Footnote 84 Labor and environmental provisions were also a key topic of contention during the 2002 fast-track negotiations and during the negotiation and ratification of Central American–Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR), which was approved by only a two-vote margin. Because of the reduced prospects of trade bipartisanship in the United States due to the degree of contention of labor provisions in PTAs, a representative from NAM affirmed in January 2007 that “labor is really the prize, the main issue, and groups like NAM, we acknowledge that there are going to be discussions on that. We accept that.”Footnote 85 A former industry representative further corroborated that the near defeat of CAFTA-DR led to the more flexible position of large US exporters and multinationals on trade–labor–environment linkage after 2005.Footnote 86

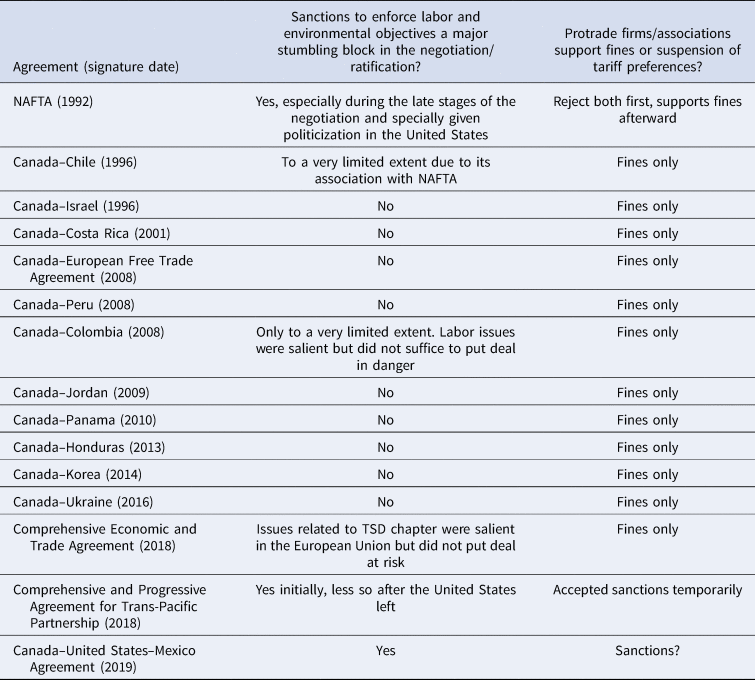

CAFTA-DR was the coup de grâce leading to political learning as pertains to sanctions and NTIs. After the so-called May 10 agreement, which consolidated labor and environmental provisions that were fully binding and subject to the possibility of trade sanctions, key protrade firms/associations decided to start to openly support NTIs, although many interests decided to remain quiet on the issue. The author did not find any protrade firm/association opposing trade–labor–environmental linkage after 2007. Groups that were previously against labor and environmental provisions in PTAs, such as the US Chamber of CommerceFootnote 87 and those that were in favor of fines but not sanctions back in 2001 (i.e., Business Roundtable), positioned themselves in favor of stronger sustainable development provisions in US PTAs. The public submissions by the US Council of International Businesses (USCIB), NAM, National Foreign Trade Council (NFTC), US Chamber of Commerce, and ECAT to the US Federal Register between 2008 and 2019 show that whenever explicit references to labor and environment are present, they support the idea of “strong and enforceable” provisions in line with the May 10 deal.Footnote 88 The fast-track debate of 2015 and, to a lower extent the negotiation and ratification of the Colombia PTA (2011), were also challenging due to issues pertaining to labor—and, to a lesser extent, environment. The difficulty involving the negotiation of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the imminent renegotiation of NAFTA led large US protrade interests to reassert their support for trade–labor–environment linkage in a manner possibly leading to sanctions (Table 3).Footnote 89, Footnote 90 One could, however, affirm that the change in the firms’ positions was not a response to policy failures and rather a response to a change in government composition or in the strategies of policy makers. In reality, however, (the fear of) trade policy failures are a common causal factor influencing both the Democrat majority in 2006Footnote 91 and the change in the position of US business interests. In other words, change in the preferences of the Congress is not likely to be an independent variable explaining change in the position of firms. Besides, trade is more often than not a low public salience topicFootnote 92 and thus policy makers will not rank it high in their list of priorities unless the topic is “activated” by lobbying groups and trigger fears of costly policy defeats.

Table 3: US PTAs and sustainable development

Paired Comparison II

Canada

In the early 1990s, large Canadian firms were often against the possibility of using trade sanctions or fines to enforce trade–labor–environmental linkage. In June 1993, before NAFTA was ratified, the Canadian Chamber of Commerce underscored that “if trade sanctions or monetary fines are part of the final side agreement texts, the Chamber could not support Canada being a part to those agreements.”Footnote 93 A similar concern was voiced by the Business Council on National Issues (BCNI).Footnote 94 However, by the time it became clear that NAFTA would risk ending up in a deadlock unless the side deals were possibly subject to trade sanctions, Canadian businesses started progressively shifting their position. In the case of Canada, however, the side deals were only subject to fines and not to trade sanctions. As long as sanctions were not a possibility to enforce labor and environmental provisions in PTAs, Canadian firms expressed “cautious optimism” with NAFTA's dispute settlement and with the PTAs that followed.Footnote 95 Canadian business associations such as the Business Council of Canada and the Canadian Exporters Council remained adamantly opposed to trade sanctions.Footnote 96

The early but partial shift in the position of large Canadian firms after a risky PTA negotiation is to be expected. However, some business associations such as the Canadian Chamber of Commerce still underscored that “a trade agreement is a trade agreement” and that labor and environment should not be dealt with within trade governance institutions.Footnote 97 It is plausible to affirm that political learning that could lead to support of sanctions had not yet settled in then. With time, however, the Canadian government consolidated its approach to trade and sustainable development issues in a manner possibly leading to fines. In turn, the discussions surrounding a PTA with Chile (1996) mimicked the NAFTA debate. Along the way, large Canadian firms became more united in accepting and even supporting fines—but not suspension of tariff preferences—to promote sustainable development objectives in trade. The Chile PTA was not particularly troublesome and therefore I would a priori not have expected firms to further consolidate their positions then. However, the proximity (geographic and economic) between Canada and the United States, as well as spillovers from NAFTA may have favored the creation of strong networks of transnational of advocates across North America.Footnote 98 That and the fact the Chile negotiations were still framed as part of the NAFTA debate may have contributed to consolidate NAFTA's experience as a form of political learning to Canadian firms. Over the 1990s and 2000s, representatives from the Business Council of Canada have underscored that labor provisions in Canadian PTAs needed “teeth”Footnote 99 that allowed those firms to promote themselves as progressive forces on sustainable development, as I would expect after “political learning” sets in.

The Canada–Colombia PTA also raised a yellow flag as pertains to the odds of a Canadian trade agreement being approved. The labor provisions in the Colombia trade agreement helped slow down the approval of its implementing bill. For reference, the Canada–Chile was in force 8 months after the end of the negotiations, compared to 33 months in the case of the Canada–Colombia PTA. During the Colombia PTA, industry representatives once more underscored that Canadian businesses wanted labor provisions in the Colombia PTA to “have teeth.”Footnote 100 Canadian firms did not further change their position against sanctions at that moment, however. Such deeper change seems to have been taking place more recently, after the negotiation of TPP and USMCA. During the TPP negotiations, the Business Council of Canada acquiesced to the presence of sanctions in the TPP, if only due to US pressure (Table 4).Footnote 101 Later on, that approach was consolidated during the NAFTA renegotiation. A representative from the business community of Canada recognized that NAFTA had a very strong and negative connotation and that stronger stakeholder support was necessary for USMCA to be approved. The interviewee confirmed that their acquiescence as pertains to the possibility of sanctions in the USMCA was linked to the anticipation of a potential trade deadlock unless stricter labor/environmental provisions were part of the equation.Footnote 102 It remains to be seen, however, whether the position of large Canadian firms will remain one in favor of sanctions or whether they will go back to a fines-based approach.

Table 4: Canadian PTAs and sustainable development

Australia

At the bilateral level, Australia's trade deals were generally not put in danger by the debate on labor and environmental provisions. For one, key domestic interests in favor of nontrade objectives in PTAs have long recognized that Australia is an export-dependent country.Footnote 103 And although Canada also considers itself a trading nation, the Canadian experience with NAFTA strongly increased the stakes of trade–labor–environmental linkage in that country. Because the effects of NAFTA on the mobilization of groups in favor of stronger trade–labor–environmental linkage have been felt much after the agreement was approved, the absence of a NAFTA-like experience in Australia as opposed to Canada is likely to have contributed to lower domestic mobilization in favor of stronger labor and environmental provisions in Australian PTAs. By the same token, given the perception of Australia as having low bargaining power in international negotiations,Footnote 104 Australian NGOs and labor unions preferred to center their lobbying efforts on other objectives more narrowly related to domestic labor market regulation.Footnote 105 In result, mobilization surrounding the promotion of labor and environmental provisions in Australian PTAs has generally been rather restricted, as shown during the negotiation of the Australian–US PTA.Footnote 106 As a matter of fact, Australian trade agreements generally do not include labor and environmental chapters unless required by third parties.Footnote 107 Despite the absence of labor and environmental provisions in most Australian PTAs, those deals were negotiated and their implementation bills cleared the Australian Parliament without much difficulty. Bearing that in mind, I would expect there not to be strong incentives for large Australian protrade firms to accept trade–labor–environment linkage in a manner possibly leading to sanctions or fines over the years.

In the early 1990s, during the WTO “social clause” debate, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the Business Council of Australia have insisted that nations should rely on economic growth to raise labor standards, therefore rejecting trade–labor linkage, let alone in a manner possibly leading to trade sanctions or fines.Footnote 108 That position was upheld during the 2000s and 2010s. The Australian Chamber of Commerce has, on a few occasions, “recognize[d] these [labor and environmental provisions] as important issues but question[ed] their merit for inclusion in trade agreements.”Footnote 109 In a submission to the Australia–EU PTA back in 2018, the Business Council of Australia underscored that it “considers that the inclusion of labor and environmental provisions in trade agreements conflate domestic policy issues with international trade and investment.”Footnote 110 A representative from a large Australian business coalition confirmed that “we'd really rather see labor issues disconnected from trade agreements.”Footnote 111 The representative confirmed that their organization's position has remained one of not linking trade and nontrade issues in the 2010s. In other words, one notices a much more reluctant approach to trade–labor–environment linkage by large Australian firms than by their Canadian counterparts despite the similarities shared by those countries.Footnote 112 To be clear, the negotiation of the labor and environmental provisions of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) could have put the agreement at risk and potentially create incentives for Australian firms to change their position. However, after the United States left the trade talks, fears of a trade deadlock connected to labor and environmental issues waned. It is plausible that Australian firms would have temporarily acquiesced to stronger labor and environmental provisions in the TPP should the United States have stayed, just as in the case of the US–Australia PTA. However, that might still not have led to political learning, as organizations pushing for stronger NTIs were much more concerned about temporary visas and temporary employment (Table 5).Footnote 113 In 2018, the Australian Labor Party's did commit to promote internationally recognized labor standards in Australian deals.Footnote 114 Although that may point to future changes in how Australian promotes labor and environmental objectives in trade, so far Australian protrade interests do not have strong incentives to change their position against NTIs.

Table 5: Australian PTAs and sustainable development

Conclusion

Why do protrade business interests shift positions on certain aspects of trade and sustainable development? I here argued that distinct experiences in enforcing the labor and environmental provisions of trade policies affects the views of business interests on how enforcement should be in the future. I presented my argument using two paired comparisons. I showed that US protrade business interests relaxed their position on the enforcement of trade–labor–environment linkage due to fears of trade deadlocks. Those fears were by far not as pervasive in the European Union. In recent years, however, EU protrade business interests have become a great deal more “soft-spoken” about the possibility of using sanctions to enforce nontrade issues in PTAs after the TTIP and CETA experiences, although they still oppose those instruments. In turn, the association between the enforcement of nontrade issues and fears of trade deadlock was more pervasive in Canada than in Australia. However, the timing of change among protrade firms/associations based in Canada adds nuance to my findings. Canadian protrade firms started to consistently support fines to enforce labor and environmental provisions in PTAs around the time the Chile PTA was being negotiated, something that seems at first counterintuitive from the perspective of my argument. That can be explained by the fact that the Chile PTA was part of the NAFTA debate, thus increasing the political costs of opposing stronger NTIs. In Australia, the movement in favor of stronger labor and environmental provisions in PTAs is still relatively weak and the focus on issues related to, for example, labor mobility seems to have diluted the focus on NTIs. Given the low politicization of labor and environmental provisions, Australian firms do not consider them a necessary condition to successful PTAs except under very specific occasions. All in all, my research hypothesis is plausible (Table 6), although it also suggests that mechanisms of policy diffusion among neighbors could play some role in the analysis.

Table 6: Empirical results

The results of this article are in line with Curran and Eckhardt's (Reference Curran and Eckhardt2020) expectation that protrade firms will act on nontrade objectives to preserve trade liberalization. However, while the authors are focused mostly on voluntary initiatives of regulation, this article fleshed out causal mechanisms that help explain when firms will support “hard law” to pursue sustainability objectives.Footnote 115 The results suggest that a focus on exogenous economic preferences to explain the lobbying behavior of firms is only part of the equation and can be complemented by endogenous explanations centered on experience-based learning. Overall, my findings paint a picture of large firms as reactive rather than proactive forces when it comes to certain aspects of the promotion of sustainable development objectives in trade, most notably strong dispute settlement mechanisms. In that regard, the persisting opposition of certain protrade firms/associations against stronger labor/environmental provisions in PTAs can help explain why, despite growing bottom-up pressure, certain countries and regions (i.e., Australia and EU) stick to labor/environment templates that are not as strong as wished by many labor unions and NGOs. Future works can benefit from exploring when past experiences will trigger ever deeper changes in how firms behave with regard to NTIs. In addition, the question as to what kinds of experiences are individually more or less likely to lead to a change in the positions of business interests as pertains to sustainable development provisions in trade also deserve more attention. Are firms in some sectors more prone to learn from previous experiences than others? Are experiences in certain domains (i.e., sustainable development) more likely to trigger change in preferences than experiences in other domains (i.e., bilateral safeguards)? Can a similar causal mechanism as the one presented in this article apply to other trade-related issues, most notably ISDS? Finally, how does experience of failure in a given country affect the position of firms in other countries? Those questions may help shed further light on the role of protrade business interests in the recent trend toward ever stricter labor and environmental provisions in PTAs.