Introduction

How do law, economic incentives, and interest group organization combine to produce regulatory policy? An oft-voiced concern is that powerful players in the regulated industry itself will dominate by virtue of their superior organizational, informational, and financial resources. This disproportionate influence may manifest itself in the legislative phase, when lobbying and campaign expenditures convince legislators to soften their positions on the stringency of the rules that govern the industry. Or, insofar as regulatory responsibilities are invariably delegated to administrative agencies and independent commissions charged with implementation, regulated industries may have the upper hand ex post as well—lobbying the bureaucracy directly or expending resources to convince Congress to reign in agencies inclined to interpret statutory delegations expansively. The result, in either case, is the weakening of regulatory stringency, potentially beyond that preferred by a majority of citizens.

An alternative perspective emphasizes the ability of lobbying entrepreneurs to assemble broad-based coalitions to advance mutual interests and coordinate the activity of participants.Footnote 1 Importantly, citizen organizations may make common cause with industry when more stringent regulations threaten both. In such cases, industry can form strategic alliances to influence legislators and regulators, in effect leveraging its financial and organizational advantages in exchange for the political advantages afforded by a more broad-based, diverse coalition.

This paper examines the interplay of delegated regulatory authority and private influence in the context of the implementation of residential mortgage market regulation under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (hereafter Dodd-Frank).Footnote 2 We focus on the credit risk retention rule, whose drafting Congress assigned to six agencies. Credit risk retention requires that sponsors of asset-backed securities retain “skin in the game”—that is, an unhedged interest in the credit risk related to a security's underlying assets. Dodd-Frank mandated a 5 percent retention requirement, but delegated to the regulators the task of defining which 5 percent. Critically, any mortgage that was deemed a “qualified residential mortgage” (QRM) would be exempt from the risk retention requirement altogether. As rulemaking proceeded, the central policy debate boiled down to whether a down payment requirement would be included in the QRM standard and, to a lesser extent, maximum debt-to-income ratios for borrowers.Footnote 3 Regulators ultimately eliminated any down payment requirement, and adjusted the debt-to-income ratio to the related, relaxed standard the newly created Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) had created in its qualified mortgage (QM) standard governing lender liability.

Mortgage market regulation provides a particularly useful setting in which to explore competing accounts of private influence. From a methodological perspective, scholars as far back as Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider1960) have recognized that private interests often succeed in achieving their policy goals by keeping issues off the agenda. By contrast, the financial crisis of 2007–08, coupled with unified Democratic government in 2009–10, forced mortgage market regulation onto the agenda. Accordingly, a focus on this issue is especially helpful in examining how the political behavior of affected interests responds to new regulatory authority that emerges from plausibly exogenous origins.Footnote 4

From a substantive perspective, securitization critically affects the real estate market. Securitizers might be reluctant to include non-qualified assets when packaging mortgages, potentially constraining credit availability and pushing up interest rates for low-income borrowers. By the same token, a lax QRM definition might reintroduce the very sorts of systemic risk that motivated the credit risk retention requirement in the first place. More generally, residential mortgage lending constitutes an enormous fraction of the U.S. economy. The Federal Reserve reported Q4 2015 total mortgage debt of $13.8 trillion, the equivalent of 69 percent of GDP.Footnote 5 Nearly $10 trillion of this total was for one-to-four family residences. How these regulations are cast, thus, has profound distributive implications, affecting who is ultimately able to afford a home, as well as implications for how systemic risk affects financial markets.

We proceed as follows: first, after briefly summarizing competing accounts of private influence in the regulatory process, we discuss the underlying issues surrounding mortgage markets, securitization, and the regulation of both. We then consider the political economy of the proposed regulation. Contra unrefined capture accounts stressing the importance of political investments by powerful industry players, we find no evidence of a significant uptick in either political contributions or overall lobbying expenditures by major mortgage lenders during critical moments in the regulatory process. Our analysis, instead, demonstrates the importance of interest group coalition building. We describe the emergence of the ad hoc Coalition for Sensible Housing Policy (CSHP) in opposition to the stringent down-payment requirements of the initial QRM rule, and document the diversity of its membership in terms of both ideology and lobbying footprint. This diversity is echoed in the high ideological diversity of opponents to the rule in Congress. Lastly, we provide evidence consistent with coordination by the CSHP in the regulatory comments process and, complementarily, discordance among regulated firms. Our analysis, though restricted to one policy issue, provides more general lessons concerning the interplay between political expenditures, organization, and information in private influence in policymaking.

Background

Private influence in policymaking

The term “capture” to describe disproportionate industry influence on regulation dates at least as far back as Woodrow Wilson. Contemporary academic discourse on the subject may be divided into ex ante and ex post strands. The ex-ante perspective suggests that regulations are designed to serve industry from the start.Footnote 6 The ex-post strand focuses on how agencies initially constituted to mitigate the adverse consequences of natural monopolies, production externalities, or coordination failures might come to be dominated by the very industries whose behavior was to be regulated.Footnote 7 A related literature considers interests acting through elected officials to pressure agencies into enacting favorable policies.Footnote 8

A more recent literature focuses on the role of asymmetric information. Laffont and Tirole (Reference Laffont and Tirole1991), for example, develop an agency-theoretic framework, where a firm can capture an agency by offering side payments to regulators in exchange for collusion in misrepresenting costs. Gailmard and Patty (Reference Gailmard and Patty2012, chapter 7) consider a model of “delegated cheap talk,” in which a political principal appoints a regulator sympathetic to an industry's point of view in order to elicit truthful revelation from the industry. And Gordon and Hafer (Reference Gordon and Hafer2005; Reference Gordon and Hafer2007) describe models in which regulated firms can make costly signals to regulators via their political expenditures, achieving reduced scrutiny in the process.

A prominent feature of both ex-ante and ex-post accounts of industry is the superior financial resources that regulated interests bring to bear to affect policy. While a meta-analysis by Ansolabehere, De Figueiredo, and Snyder (Reference Ansolabehere, Di Figueiredo and Snyder2003) finds little evidence that corporate campaign contributions affect voting behavior in Congress, Stratmann (Reference Stratmann2002) finds a significant relationship between changes in contributions from the banking, insurance, and securities industries campaign contributions between 1991 and 1998 and changes in representatives’ votes on repealing Glass-Steagall. Gordon and Hafer (Reference Gordon and Hafer2005) document a relationship between the political expenditures of energy companies and reduced regulatory scrutiny by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. More recently, De Figueiredo and Silverman (Reference De Figueiredo and Silverman2006) find returns to lobbying by universities represented by Appropriations Committee members, while Richter et. al. (Reference Richter, Samphantharak and Timmons2009) document returns to lobbying in the form of lower corporate taxes. You (Reference You2017) finds higher levels of lobbying expenditures by large firms and trade associations on bills with more particularistic provisions.

An alternative account of private influence downplays the financial resources of firms or groups in favor of their organizational resources. Hansen (Reference Hansen1991), for example, describes the role of the American Farm Bureau Federation in coordinating agricultural interests in the first half of the twentieth century. Hansen (Reference Hansen1998) describes the role of commercial associations in shaping federal bankruptcy law, most importantly the Bankruptcy Act of 1898. And Schattschneider's (Reference Schattschneider1935) account of tariff policy stresses oligarchic hierarchies of interest groups, often subsidized by their wealthiest members. Coordination also plays a critical role in accounts of regulatory politics stressing firm and interest group collusion—either in the context of trade associations or ideologically diverse coalitions.Footnote 9

Several studies have found disproportionate industry influence in credit market regulation in the contexts of the financial crisisFootnote 10 and the thrift debacle of the 1980s.Footnote 11

The Dodd-Frank Act: lead-up and follow-upFootnote 12

There would, almost certainly, have been nothing like Dodd-Frank without a financial crisis. Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan was said to have turned a deaf ear to Fed governor Edward Gramlich's call for regulation of subprime lending. Neither he nor his successor Ben Bernanke nor Congress had much appetite for increased regulation before 2008. Since the politics of regulation respond to economic crises, we weave descriptions of the economy into our account of the regulatory response.

In 2006, the housing bubble burst. The Case-Shiller 20-City Composite Home Price index fell from its all-time high of 206.49, in May 2006, to 140.79, in June 2009. Increasing numbers of mortgages, particularly the “subprimes,” became delinquent. Foreclosure filings rose from 771,552, in 2006, to 2,871,891, in 2010.Footnote 13 Many of the troubled mortgages were securitized in Private Residential Mortgage Backed Securities. The market for these securities collapsed. Insurers, notably American International Group (AIG), were unable to make good on the credit default swaps that had insured the securities. The crisis also weighed heavily on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which were placed into conservancy in September 2008. After Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy on 15 September 2008, the Fed undertook an $85 billion rescue of AIG the next day.

Main Street then woke up to an international financial crisis, and after September 15, Barack Obama pulled ahead of John McCain in the polls. Obama's victory in November was complemented by increased Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress. The Obama Administration did not make financial regulation its major priority, instead focusing its attention on the Affordable Care Act. But by the time Congress passed the ACA on 10 March 2010, the crisis had abated. The NBER declared the second quarter of 2009 as the end of the recession, and by the time the president had signed Dodd-Frank on 21 July 2010, unemployment was down to 9.4 percent, while the housing index remained above its 2009 low.

Action in the Senate was pivotal to the passage of Dodd-Frank. The bill passed easily in the House, where Democrats had a large majority. In the Senate, the Democrats were three votes shy of avoiding a successful filibuster once Russ Feingold (WI) announced he would vote against the bill because it did not go far enough. Feingold's defection meant satisfying Scott Brown (R-MA), who forced the bill to be stripped of a tax on banking transactions. He and the two Maine Republican moderates, Olympia Snowe and Susan Collins, ultimately voted for the bill. Partisan conflict over the bill gave no indication of the overwhelming bipartisan coalition that would emerge in 2011 on regulation of the mortgage market, described below.

The sharp ideological split found in Senate passage of Dodd-Frank, when all but one of the Democrats and only three Republican moderates supported the bill, may well have masked ideological ambiguity over the details of mortgage market regulation. Liberals wanted regulations that would protect consumers from “bad” products but also wanted to maintain access to credit for low-income borrowers. Conservatives objected to government intervention in the economy, per se, but wanted tight regulation to limit systemic risk and future bailouts. During Senate debate on Dodd-Frank, Senator Bob Corker (R-TN) proposed an amendment (3955) to require a 5 percent down payment on new mortgages and additional credit and income history reporting for borrowers with more than 80 percent loan-to-value. The amendment, co-sponsored by senators Gregg (R-NH), LeMieux (R-FL), Coburn (R-OK), and Brown (R-MA), was defeated 42–57.

The tensions present for both liberals and conservatives were expressed in the details of Dodd-Frank. The provisions relevant to our empirical analysis concern two rules regarding residential mortgages. First, Section 1942 of the statute amended the Truth-in-Lending Act to give lenders a “safe harbor” from borrower-initiated lawsuits for violations of the ability-to-repay rule, when the loan met the standards for a QM, and also delegated crafting of the QM definition to the newly created CFPB. Dodd-Frank appears to have given the CFPB complete discretion over QM:

The Board may prescribe regulations that revise, add to, or subtract from the criteria that define a qualified mortgage upon a finding that such regulations are necessary or proper to ensure that responsible, affordable mortgage credit remains available to consumers …

This language, however, is preceded by very specific language on matters such as balloon payments, points and fees, length of mortgages, adjustable-rate mortgages, and income verification, that could be considered starting points for the CFPB. Clearly, a broader definition of QM reduces liability concerns and would, thus, be favored by lenders. On these matters, the CFPB largely followed Congress,Footnote 14 and the industry did not contest these aspects of the QM rule. Floros and White (Reference Floros and White2016) and Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (2019) find evidence that these provisions have led to a substantial reduction in default risk. (By contrast, the term “down payment” does not appear in Dodd-Frank.) It should be further noted that, in addition, to the statutory language in Dodd-Frank, the CFPB created an ability-to-repay (ATR) ruleFootnote 15 that imposed lending standards (such as employment verification) that are in addition to QM. The CFPB currently refers to the combined standards as the ATR/QM rule.

Second, the Act specified conditions for credit risk retention (as described in the introduction), carving out an exemption for QRMs and delegating rulemaking authority to six agencies: The Fed, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The relationship between QM and QRM is specified in Section 941 of the Act:

The Federal banking agencies, the Commission, the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, and the Director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency in defining the term “qualified residential mortgage” … shall define that term to be no broader than the definition “qualified mortgage” as the term is defined under … the Truth in Lending Act, as amended by the Consumer Financial Protection Act of 2010, and regulations adopted thereunder.

Note that “no broader” denotes a weak inequality, thus, permitting QRM to be identical to QM.

The QRM exception, offered by senators Landrieu (D-LA), Hagan (D-NC), and Isakson (R-GA), entered Dodd-Frank by unanimous consent to amendment 3956. Aside from authorizing the exemption of QRMs from credit risk retention requirements for securitizers, the statute provided no details beyond the “no broader” constraint. Moreover, the language appeared to give the CFPB first-mover status, although the CPFB would not begin operations until July 2011.

The six agencies announced a proposed QRM rule the week of 28 March 2011 and published it on April 29 in the Federal Register. The proposed QRM rule was tight: the statutory QM features (points, balloon payments, etc.) were incorporated, but, critically, a 20 percent down payment would be required for new home purchases.Footnote 16 Borrower monthly housing debt could be only 28 percent of income, and total monthly debt 36 percent of income. These requirements would have placed a large slice of residential mortgages outside of QRM status, despite their meeting other underwriting standards—potentially raising rates on those mortgages owing to the downstream effects in the secondary market.Footnote 17

A recovering economy and a weak housing market set the stage for the political activity we detail in the empirical analysis below. Even prior to the formal announcement of the standards, in a bipartisan letter on 16 February 2011, Senators Landrieu, Hagan, and Isakson called for not including a down payment standard in QRM.

The stringent initial QRM rule ignited a firestorm of protest, coming (as we demonstrate below) not primarily from mortgage lenders, but from realtors. The realtors allied with a subset of lenders, as well as mortgage insurers and builders, along with borrowers, civil rights and other left-leaning organizations. Critical in this respect was the ad hoc formation of the CSHP, which lobbied against the rule. CSHP found itself supported by an ideologically heterogeneous swath of members of Congress. An important feature of the CSHP's efforts was its detailed white paper describing the adverse consequences of the down payment requirement, which was submitted during the proposed regulation's notice and comment period.

The next regulatory step was a proposed QM rule issued by the Fed on May 11. This proposal, largely a placeholder for the CFPB (which began operations on July 11), solicited comments on alternatives. It did not include language about down payments or propose a firm standard on borrower debt-to-income ratios (although it discussed them at length).

The CFPB issued a final QM rule on 30 January 2013. By then, the crisis was receding. Unemployment was down to 7.5 percent, and the Case-Shiller index had rebounded to 156.02. The rule had no down payment restriction and imposed a 43 percent total debt to income standard.Footnote 18 Standards were “temporarily” patched for any loans purchased by the GSEs. Congress had allowed other federal lenders to define their own standards. Small lenders had relaxed standards. The 43 percent standard was only slightly below the 45 percent restriction that the 2011 proposal had mentioned as a standard lending criterion before the crisis, and well above the 36 percent in the 2011 proposed QRM rule.

On 28 August 2013, a revised QRM proposal simply aligned QRM with QM. Down payments and strict debt-to-income ratios were dropped. The QRM rule was finalized on 22 October 2014. By that point, unemployment had fallen to 6.2 percent, lower than in the same month of 2008, and the Case-Shiller index exceeded its April 2008 level.

In the analysis that follows, we explore the political conditions that led regulators to back down on the stringent QRM rule. We then relate features of the mobilization that occurred against the rule to more general lessons concerning private influence on policymaking.

Data and approach

As noted in the introduction, mortgage market regulation provides a fertile environment in which to assess competing accounts of private influence in the regulatory process. That being said, even stipulating the essential exogeneity of the financial crisis that gave rise to the Dodd-Frank Act, we, nonetheless, lack a “silver bullet” identification strategy that would permit us to definitively assess the political mechanisms underlying the form that regulation would ultimately take. Accordingly, we proceed by looking for empirical patterns consistent or inconsistent with the competing accounts of private influence described above.

Our empirical strategy unfolds in four steps. First, we search for any upticks in political and lobbying expenditures by the mortgage lending industry and CSHP members in the quarters in which the initial QM and QRM rules were under active consideration. An unrefined industry influence account would anticipate increases in lender lobbying expenditures and possibly campaign contributions during these periods, although the latter may be mitigated by cyclical variation brought about by the electoral calendar.

In isolation, this approach would be of limited utility, for two reasons. First, rulemaking under Dodd-Frank was ongoing during this period, and covered many aspects of the mortgage market, including disclosures, servicing, escrow, and appraisals. Thus, while the presence of a significant uptick in expenditures would be interpretable as evidence in favor of the unrefined influence account, the absence of a significant uptick would not be definitive evidence against it. Second, while lobbying disclosure forms reveal the set of agencies (including both houses of Congress) lobbied on behalf of a client and the set of issues lobbied on, they do not disaggregate total expenditures across these categories. Thus, our analysis of the expenditure data should be understood as a first cut at assessing the operative mechanism.

Lobbying data comes from disclosure reports mandated by the Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995 (as amended) and the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act of 2007. The second source of data comes from Federal Election Commission campaign finance data. The Center for Responsive Politics compiles the lobbying and FEC data and provides them on their website (opensecrets.org); CRP cleans the data and assigns industry categories to specific clients. For the analysis in this paper, we use bulk data generously provided by CRP and archived on their website. Mortgage lenders were identified on MortgageStats.com from the first quarter of 2007 through the third quarter of 2014.

In the second step, we examine the (revealed) preference profile of active opponents of the proposed rule. First, we examine the lobbying footprint and ideological heterogeneity of the Coalition for Sensible Housing Policy. The former relies on the lobbying data described above; for member organization ideology, we rely on CFScores,Footnote 19 which estimates ideology on a Left-Right scale based on political contributions. Second, in a related analysis, we examine the ideological leanings of members of Congress who expressed opposition to the QRM rule (and the down payment requirement in particular), using legislator DW-Nominate scores.Footnote 20 The unrefined industry influence account would anticipate ideological clustering on the political right among groups and legislators actively opposed to the QRM measure, consistent with the composition of the earlier opposition to Dodd-Frank's legislative enactment. Evidence of ideological heterogeneity among opponents would be, by definition, more conducive to a cross-ideological coalition account.

In the third part of the analysis, we consider evidence of cross-subsidization within the Coalition. While ad hoc coalitions are under no obligation to report the sources of their resources, indirect evidence may be found in changes in the lobbying expenditures of member organizations around the time the rule was under consideration. A surge in the lobbying expenditures of a subset of “big players” coincident with the QRM rule proposal is consistent with cross-subsidization. This part of the analysis is subject to the same caveat concerning the noisiness of lobbying data as the first part.

In the final part of our analysis, we turn to a detailed examination of the content and timing of comments to regulatory agencies by Coalition members and non-coalition individuals and organizations. Notice and Comment proved an important forum in which affected parties raised objections to the proposed policy and the drafting agencies considered them. To uncover the identities of commenters, we scraped the text of all comments on those rules using the regulations.gov API and the search engines of agencies that do not archive comments on regulations.gov. We examine the identity of commenters from the Coalition and the timing of their comments; and consider the content of those comments by examining the extent of overlap with the CSHP white paper. For this latter analysis, we use a commonly-employed plagiarism detection algorithm: n-gram string comparison.Footnote 21 Evidence that the CSHP was serving in a coordinative role can be found in (1) clustering in the timing of comments of CSHP member organizations in comparison with the timing of comments by other actors; and (2) textual similarity of comments by CSHP members with the Coalition's white paper, relative to the comments of other actors. Lastly, we supplement this quantitative approach with a qualitative assessment of the content of the comments themselves. This permits us to detect commonalities in the objections of certain players in the broader interest group environment, as well as dissension in the ranks of the regulated industry.

Results

Industry and coalition political expenditures

We first consider whether the introduction of new mortgage regulation on the legislative and regulatory agenda affected patterns of political expenditures, among lenders in particular. Specifically, we restrict attention to the set of large lenders—those who were ever in the top one hundred by volume from 2008 to 2014—who made political expenditures during that period; and, for comparison, CSHP members who had made expenditures during that period. We look for changes in expenditures by members of the respective groups in three key periods: (1) the quarter in which Dodd-Frank was initially passed; (2) the notice and comment period for the initial QRM rule; and (3) the notice and comment period for the revised QRM rule. To do so, we simply regress the first difference of expenditures on a vector of quarter-specific indicator variables (along with, for the lenders, the first difference of total loan volume, to control for idiosyncratic effects of lender business that might be spuriously correlated with the timing of the statute and pursuant regulations). We then graph the estimates. We look at changes in lobbying expenditures, PAC expenditures, and the fraction of PAC expenditures going to Republicans. Results appear in figure 1.

Figure 1: First Differences in Political Expenditures by Top 100 Mortgage Lenders and Politically Active CSHP Members

Examining lobbying expenditures (the top panel), we observe little quarterly variation in expenditures by lenders (the solid line). In fact, each of the quarters in question witnessed slight decreases in lobbying expenditures, the third of which (in the quarter in which the QRM rule was finalized) is statistically distinguishable from zero. By contrast, lobbying by politically active CSHP members experienced upticks during both quarters in which QRM was under consideration, with the uptick for the initial QRM rule approaching statistical significance at conventional levels (p = 0.07, two-tailed).

Turning our attention to the levels of PAC expenditures, we see very little quarterly variation in overall spending on candidates by the committees associated with lenders. There is an increase in lender PAC expenditures in the final QRM rule period that approaches statistical significance (p = 0.06, two-tailed); however, the more intense, initial QRM period experienced a decrease in contributions by lenders relative to the preceding quarter, albeit a statistically insignificant one. By contrast, we observe considerably more volatility in the contributions of CSHP-related committees. That being said, there are no significant upticks or decreases during the three periods under scrutiny for CSHP. In short, the data do not suggest either last-minute contributions to affect the content of the legislation, or that an incipient regulatory regime induced substantial increases in political expenditures.

In the third panel, we plot changes in the fraction of PAC contributions going to Republican candidates. As the graph indicates, lenders do not appear to have shifted their contributions toward Republicans at the three critical regulatory junctures. It bears pointing out, however, that the plot of first differences obscures a significant shift among lenders toward greater overall contributions to Republicans beginning in the third quarter of 2009—consistent with media reports of general dissatisfaction in the financial services industry with the Democratic majority at the time. The shift is also consistent with anticipation of the switch in control of the House brought about by the 2010 midterm elections.

Cross-ideological coalition building

Next, we examine the composition of interest group and legislative coalitions actively opposing enactment of a strict QRM standard. Before proceeding, we provide context for this part of our analysis. Following publication of the initial credit retention rule in 2011, the CSHP submitted its white paper, “Proposed Qualified Residential Mortgage Definition Harms Creditworthy Borrowers While Frustrating Housing Recovery,” as a comment to the six agencies charged with crafting the rule. The comment claimed that Congress had rejected including a down payment requirement in QRM during debates over the relevant section of Dodd-Frank, and that the requirement would harm low income and first-time buyers.

The Coalition argued that the marginal benefit of the down payment requirement in terms of default risk was small when combined with the other underwriting standards included in the definition, but that the cost to home buyers excluded from the QRM designation would be high: on the order of 80 to 185 basis points, stemming from enhanced capital costs of 5 percent risk retention for non-QRM loans, a smaller market of lenders with portfolios large enough to permit 5 percent retention, and reduced liquidity stemming from perceived riskiness of non-QRM loans. The white paper concluded that the down payment would harm consumers, stunt the recovery of the housing market, and fail to shrink government presence in the housing market (by driving non-QRM borrowers to take out FHA loans). Ultimately, the CSHP would propose aligning the QM and QRM standards.

What was perhaps more important than what was said in the white paper was who was saying it. A number of trade associations representing financial, insurance, and real estate interests were on board: these included the American Bankers Association, the Community Lenders Association, the Mortgage Bankers Association, and the National Association of Realtors (on whose data the analysis in the white paper was based). The Mortgage Insurance Companies of America (MICA) also joined: borrowers with mortgages with a loan-to-value ratio above 80 percent must buy mortgage insurance for Fannie and Freddie to purchase them, creating a significant interest for the insurers in a high volume of loans with small down payments. Along with industry trade associations, CSHP also contained a number of community advocacy, progressive, and civil rights organizations as signatories. These included the NAACP, the National Urban League, Habitat for Humanity, Consumer Federation of America, and the National Fair Housing Alliance.

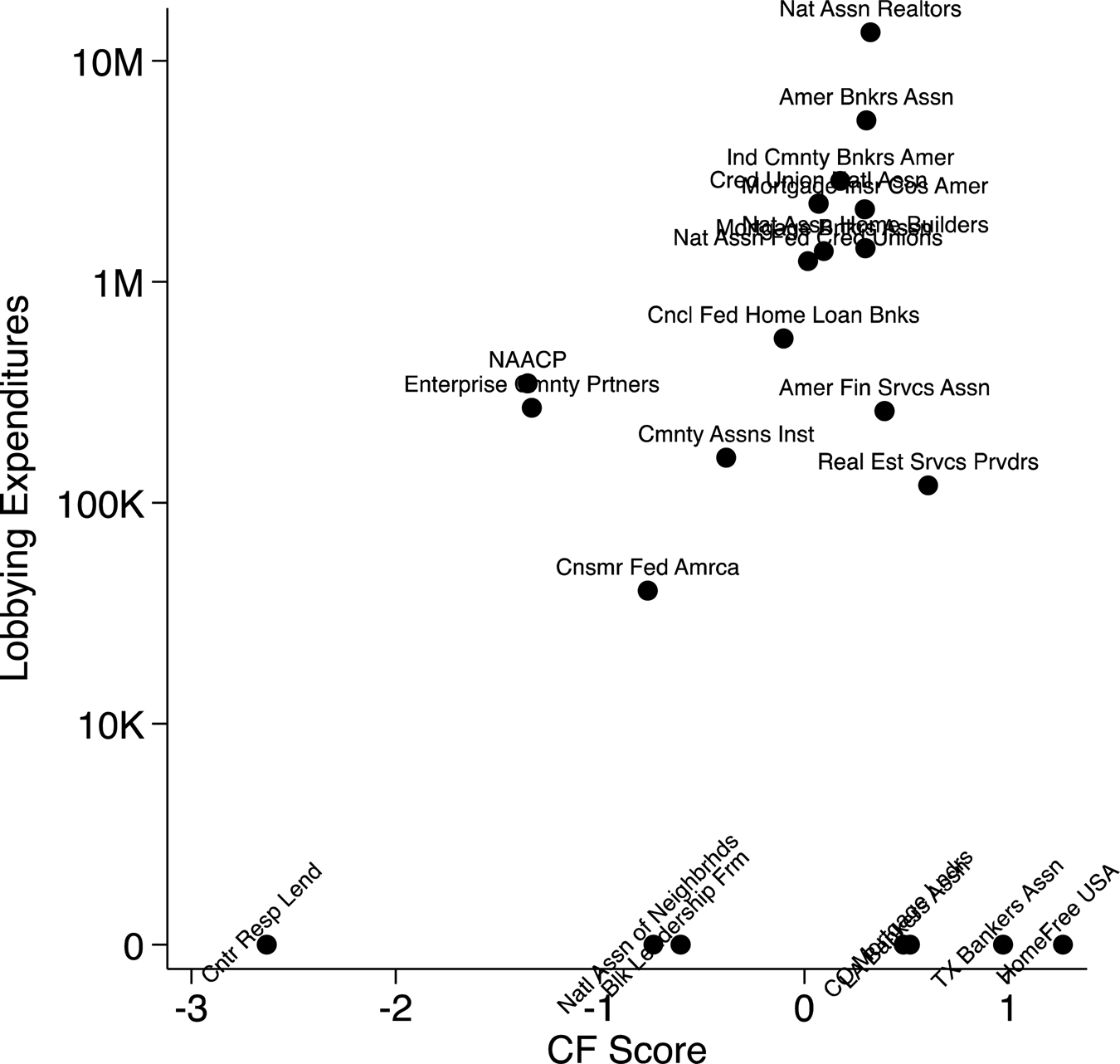

The CSHP's member organizations, then, varied markedly in both their ideological leanings and their lobbying footprint in Washington, D.C. Our measure of lobbying is expenditure in the first half of 2011. Our measure of ideology is the CFScoreFootnote 22: the score is based on campaign donations, with lower values corresponding to more liberal—and, subsequently, higher values more conservative—political leanings. Figure 2 illustrates the substantial political heterogeneity of the Coalition: members ranged from the political Left (see the NAACP, the Consumer Federation of America, and the National Association of Neighborhoods) to the right (the Texas Bankers Association and American Financial Services Association). The “center of mass,” center-right, echoes the findings in Bonica (Reference Bonica2013) for industry groups more generally.

Figure 2: Lobbying Expenditures and Ideological Leanings of Coalition for Sensible Housing Policy Member Organizations

The second thing to note in the figure is the substantial degree of heterogeneity in lobbying activity among Coalition members. Only about half of Coalition members disclosed any formal federal lobbying presence during the initial debate over QRM, and among those that did, the size of that presence varied by orders of magnitude: the eight member organizations spending more than a million dollars in the first half of 2011 were the heaviest hitters in the CSHP, with the National Association of Realtors topping the list at $13.5 million during this period. Parenthetically, we note that high lobbying expenditures are extremely highly correlated with PAC contributions—the pairwise correlation between lobbying in 2011 and PAC contributions summed over the 2010 and 2012 cycles was 0.96.

The cross-ideological nature of opposition to the proposed QRM rule was echoed in the congressional response to the measure. In the months following the agencies’ 2011 proposal, 301 House members wrote to the agencies opposing the down payment requirement—most (282) as signatories to a single petition that circulated in the House. Forty-eight Senators also wrote to oppose the requirement.Footnote 23 The ideological heterogeneity of the commenters mirrored that in the CSHP. Figure 3 displays empirical, cumulative distribution functions of first dimension DW-Nominate scoresFootnote 24 for the members of House and Senate who did (dashed) and did not (solid) oppose the down payment requirement. Several features of these plots are notable. First, critics of the rule span the ideological spectrum. Second, there is little difference between the ideological distribution of critics and silent legislators in both chambers. To add some precision to this claim, we computed Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics (displayed in the figures, along with exact p-values) to test the equality of distributions by chamber. In the Senate, we cannot reject the null hypothesis that legislators who did and didn't object to the rule were drawn from the same distribution. In the House, we can reject the null only at p < 0.10. As is evident from the figure, House differences owe not to a discernible ideological orientation of the commenters, but rather because House members who commented were slightly less ideologically extreme than those who did not.

Figure 3: Ideological Distribution of Legislators Objecting and Not Objecting to the Proposed QRM Rule: Empirical Cumulative Distribution Functions

Interestingly, immediately following the preliminary rule's publication in April 2011, sixteen Democratic members of the House Financial Services Committee sent a letter to the regulatory agencies suggesting that while “it does seem appropriate to establish some down payment requirement (and inversely a loan to value requirement) … we are very concerned that the high 20% down payment requirement in the draft rule inappropriately excludes too many otherwise qualified homebuyers …” The letter pointed to the FHA's 3.5 percent cash down and Fannie and Freddie 10 percent down payment requirements as more appropriate standards to contemplate. Nonetheless, pressure to eliminate the down payment requirement altogether soon came to a head, and twelve of those sixteen signatories to the letter, encouraging moderation, ultimately expressed positions in favor of outright elimination of the requirement.

Political expenditures by specific coalition members

The diversity of interests represented in the CSHP suggests that any attempt to characterize the relevant interest group environment as the lending industry against the public and the eventual capitulation of the regulatory agencies to the demand to drop the down payment requirement as agency “capture” is misleading and reductive. Our analysis of quarterly political expenditures by lenders and CSHP members underscores this point.

Of course, the fact that organizations that specifically coalesced against the proposed rule experienced an uptick in lobbying on average is perhaps unsurprising. We can dig deeper, however, and examine whether specific CSHP members are driving this uptick, and if so, which ones. Given the massive heterogeneity in the overall lobbying footprint described in the preceding section, evidence of significant upticks in expenditures for heavyweight members of the Coalition would be consistent with cross-subsidization; in exchange for the ideological diversity provided by the community and civil rights organizations, housing sector for profits provided the material resources to support the lobbying effort.

Toward this end, we regressed, for each 2011 CSHP member organization with a lobbying presence, the quarterly change in logged lobbying expenditures on an indicator variable for the second quarter of 2011 (when the preponderance of the action concerning the proposed QRM rule occurred). Positive coefficient estimates correspond to above average percentage changes in lobbying in the quarter that the initial QRM rule was proposed, and negative estimates correspond to below average percentage changes. Figure 4 displays coefficient estimates from these regressions along with 95 percent confidence intervals calculated from robust standard errors, ordered by the size of the lobbying presence of the organization in 2011 Q2.

Figure 4: Upticks in Lobbying by Coalition Members during QRM Discussion

Of the twenty-one Coalition member organizations that disclosed lobbying, eight increased their lobbying expenditures by a statistically significant proportion while QRM was in the Notice and Comment phase. To check whether these changes in lobbying expenditures corresponded to lobbying on QRM specifically, we returned to the lobbying disclosure database and examined all issues mentioned by lobbyists for those organizations for the quarter in question. Of the eight organizations in question, six specifically mentioned lobbying on the QRM issue in particular. The National Association of Realtors (which also provided the data analytics for the CSHP white paper) and Independent Community Bankers each filed eighteen different reports mentioning the issue, while the American Bankers Association filed eight reports, the National Association of Federal Credit Unions six reports, the NAACP fifteen, and the Community Mortgage Lenders of American nine. Two other organizations—the American Financial Services Association and the Consumer Federation of America, reported lobbying on Dodd-Frank–related issues more generally. The large increase in Consumer Federation expenditures may be driven by the imminent creation of the CFPB—and indeed, it is mentioned in their disclosures for that quarter.

The picture painted by this analysis, though circumstantial, is one of cross-subsidization within the industry: a few big players providing the lion's share of financial resources for the lobbying effort in exchange for participation by a more diverse array of affected interests. Notwithstanding the substantial lobbying expenditures made by this subset of CSHP member organizations, it is notable that CSHP itself did not itself disclose any such expenditures. Moreover, the public relations firm that helped to organize the Coalition—Rasky Baerlein—did not disclose either the CSHP or any of its member organizations as clients in 2011 or 2013.Footnote 25

Coordination in regulatory commenting

Much of the ire directed at the agencies proposing the initial QRM standard came in the form of comments to the agencies during the mandated Notice and Comment period. Initially, the agencies gave affected interests until June 10 to comment—just six weeks after the initial proposal. Following an outcry, the comment period was extended to August 1, for a total of ninety-four days. During this period, the six agencies received hundreds of comments.Footnote 26 We collected data on the timing of submissions during the ninety-four-day period. In total, our data include 1,861 comments, 120 of which came from members of the CSHP. All 120 of these comments mention concerns with, or objections to, the down payment requirement.

While we lack “smoking gun” evidence that the CSHP facilitated coordination among its members in lobbying, patterns in the timing of comment submissions, and the language of the comments themselves, are instructive. Specifically, we first look for clumping in the timing of submissions by Coalition members, and see whether the timing of their submissions differed significantly from the distribution for non-coalition members.

The results of this analysis are shown in figure 5. This figure shows, for each of the six regulatory agencies, the empirical cumulative distribution function for Coalition members (solid black lines) and non-coalition members (dashed lines). Also shown in the figure are Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics and associated exact p-values. For four of the six agencies, we can reject the null hypothesis that the distributions are the same. Perhaps more importantly, the data suggest that with the exception of comments to HUD and OCC, a large majority of Coalition-member comments came on the day of the deadline, and an even larger majority in the last week of commenting.Footnote 27 Our inability to reject the null for HUD and the OCC may be driven by the fact that fewer coalition members submitted comments to those agencies: for example, only nine of the twenty-five coalition members that submitted comments to any agency submitted to HUD.

Figure 5: The Timing of Coalition Comments to Agencies: Empirical Cumulative Distribution Functions

We next turn to the content of the comments filed by private actors following the publication of the initial QRM rule. We proceed in two steps. First, we assess which interests were the core members of the Coalition, as evinced by the textual similarity of their comments with the language in the CSHP white paper. We then proceed to assess qualitatively the content of the comments themselves. Our quantitative analysis of content similarity proceeds by looking for common n-grams (strings consisting of n words) between a given comment and the white paper, across each comment in the entire corpus of comments, divided by the total number of n-grams in the white paper. The resulting index of textual overlap may be interpreted as the fraction of sequences of words in the white paper that made their way into a comment.Footnote 28 We examined 5-, 10-, and 15-grams; as the results are identical across the different measures, we restrict attention to 5-grams here. Results from the text analysis appear in figure 6.

Figure 6: Textual Overlap of Coalition Member Comments with CSHP White Paper, as Compared to Non-Member Comments

The left panel of the figure displays empirical, cumulative distribution functions for the textual overlap index, broken into CSHP member and non-members, respectively. It is immediate, and perhaps unsurprising, that the distribution of CSHP overlap scores dominates that of non-members. A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of the difference between the distributions confidently rejects the null of no difference.

The right panel plots textual overlap scores for comments made by specific CSHP members, and hints at the organizational center-of-gravity of the Coalition. The four organizations that borrow most heavily from the white paper are the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB), the Community Mortgage Banking Project, the National Neighborworks Association, and the National Association of Realtors (this last one is unsurprising, given that the CSHP had based its white paper on the Realtors’ data). The NAHB scores particularly high on 5-gram similarity, as their comment, in addition to echoing some of the concerns expressed in the CSHP white paper, actually appended the CSHP white paper itself to the organization's own comment.

The content of specific comments

What did the comments actually say? Several non-industry organizations emphasized the disparate impact of a down payment requirement on minority borrowers. Groups representing lenders and mortgage insurers, and some of their members, suggested relaxed LTV or debt-to-income standards in QRM. The participation of several trade associations representing banks and mortgage lenders in the CSHP masked some dissension in their ranks, however. While most lenders echoed the CSHP attack on the down payment requirement, a representative from JP Morgan Chase voiced approval for the loan-to-value threshold, calling it “appropriate,” as it would contribute to a decreased rate of default.Footnote 29 A comment from Wells Fargo suggested possibly raising the LTV from 80 to 90 percent, but not necessarily doing away with the requirement altogether. And lengthy comments on credit risk retention from Bank of America and Citi ignored QRM altogether. A comment from Ally, the fifth largest lender, only joined in a comment on auto loan securitization, while SunTrust focused its comment on asset-based commercial paper. Generally speaking, the members of trade associations and industry groups, represented in the CSHP, that commented tended to echo opposition to the proposed QRM standard.

Discussion

Time was on the side of the coalition

As discussed above, after the publication of the draft QRM rule in 2011, the economy continued to improve. As the crisis receded, policies aimed at preventing a future crisis lost their appeal. Moreover, agency heads who may have been committed to a stiff standard were replaced. At the SEC, Mary Jo White replaced Mary Schapiro. President Obama nominated Melvin Watt to head the FHFA on 13 May 2013. Although Edward DeMarco remained as acting head of FHFA at the time of the proposed revision, he was clearly a lame duck. At the FDIC, Sheila Bair, a Republican and former counsel to Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole, had given way to Martin Gruenberg, who came to the FDIC from the staff of Democratic senator Paul Sarbanes. When the final QRM was issued, Bair continued to voice support for an 80 percent down payment standard.Footnote 30

Was the bipartisan coalition exceptional?

Our analysis demonstrates that a broad coalition arose to bring down the strict down payment and debt-to-income rules of the initial QRM rule. The Coalition for Sensible Housing Policy grouped lenders, mortgage insurers, realtors, builders and remodelers, servicers, and title insurers. These real estate industry organizations forged an alliance with progressive, low-income housing, and minority advocacy groups. The Coalition found sympathetic ears in Congress, with members across the ideological spectrum fighting the proposed rule.

Clearly, as we showed above, a broad, bipartisan coalition could not be used to support or block the Dodd-Frank Act itself, where the “statutory” markers of QM and QRM were initially put down and the CFPB created. Legislators on the right strenuously opposed the CFPB, and some of them were likely to oppose any form of market regulation. The Coalition was, thus, savvy in limiting the fight to a single aspect of regulation.

By contrast, most aspects of government regulation of the mortgage market appear ideological and partisan. As examples, consider principal reduction and foreclosure relief. Mian, Sufi, and Trebbi (Reference Mian, Sufi and Trebbi2010) show that DW-NOMINATE scores correlate highly with voting on the American Housing Rescue and Foreclosure Prevention Act in 2008. The issue of principle reduction led to progressive calls for removal of Edward DeMarco as acting head of the FHFA and conservative votes against the confirmation of his replacement, Melvin Watt.

Greater long-run consequences pertain to the status of Fannie and Freddie. Dodd-Frank kicked this can down the road by requiring that the Treasury study ending the conservatorship and reforming the housing finance system. Section 1941 gives a “sense of Congress” that is rather unfriendly to the low-income housing policies of Fannie and Freddie and calls for reform. The cheap talk apparently did little to change the partisan divide on passage of the bill. In every year since 2013, Congress has seen Republican and bipartisan attempts at changing the status of the GSEs, but the status quo has held. No bill has received a floor vote, and the GSEs continue to be the largest suppliers of mortgages. After Trump's election in November 2016, share prices of Fannie surged on expectations that Fannie and Freddie might be privatized under unified Republican control. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has stated during hearings that the GSEs were priorities for the administration. Nonetheless, the specifics of a plan for reform remain uncertain, at least through the summer of 2019. The 2018 midterm elections took place with the GSEs largely unmodified during the Trump Administration. By mid-2019, Fannie's and Freddie's share prices were not only well below their highs post-inauguration, but also below those in the last three years of the Obama Administration.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the politics of the final QRM rule suggests several valuable lessons for scholars conducting research on the political economy of influence in regulatory policymaking more broadly. First, while the Coalition that arose in opposition to the proposed rule was very broad, it did not completely envelop a heterogeneous “industry.” The surviving lenders from the 2008 financial crisis may have wanted a legal floor that protected them from new competition from more risk-acceptant lenders. They may have been reluctant to take on regulators after their public reputations had been badly damaged. In particular, the large banks did not enthusiastically support a lax QRM—in fact, it has been accompanied by a reduction in their market share. The most vociferous industry opposition to the proposed down payment standard came not from lenders but from realtors, home builders, and insurers. Thus, any account of this particular instance of regulatory politics that frames the conflict as one of industry against consumers is misleading on two counts: not all of the lending industry was opposed to the more stringent standard, and not all of the opposition came from the lending industry.

Second, we note that too great an emphasis on readily available data sources on private influence can lead to an incomplete picture of the political economy of influence. In the last several decades, researchers have made tremendous strides in our understanding of the subject using both campaign contributions and expenditures data and lobbying disclosure data. Neither of these data sources directly permits analysis of coalition organization and expenditure. A better understanding of coalition organization is in reach with the advent of new tools for text analysis, as well as the advent of e-rulemaking, which has led to the archiving of public comments on regulations.gov and agency websites.

Moreover, many important investments made by private actors seeking to affect policy may not be captured in the data on political expenditures in lobbying and campaign expenditures. When Barry L. Zubrow, executive vice president of JP Morgan Chase, submitted a sixty-seven-page comment on credit risk retention (only part of which concerned QRM), the opportunity cost of his time and staff costs would not be reflected in the lobbying disclosure data. Likewise, the effort that the Mortgage Bankers Association employees put into the data analysis that ultimately makes its way into a coalition white paper are not counted, despite their clear importance to framing the debate. These costs are not the oft-maligned compliance costs of regulation, but rather political expenditures directed at affecting regulation.

Our fourth observation concerns the role of information and expertise in the rulemaking process. Few ordinary citizens comment on regulatory rules. Some citizen comments are just venting steam. But even those that overcome the barriers to entry are rarely going to be able to put forth a quantitative analysis of the costs and benefits of a proposed rule. One who did was David A. Levine, possibly the former chief economist of Sanford C. Bernstein & Company. But his analysis lacks the political savvy of the Coalition white paper. Levine supported the down payment standard but followed with an intelligent argument against a political untouchable, 5% retention. Personal positions, if expressed, are likely to be much less effective than those from organized interests.

To some degree, the organized interests have an informational advantage with respect to the agency. So it is quite possible that, politics aside, they made convincing policy arguments to regulators. However, the advantage should not be exaggerated. The first QRM proposal refers to an abundant academic literature that guided the policy. The Federal Reserve, one of the six agencies charged with credit risk retention, has over three hundred Ph.D. economists on its research staff. If the regulators did not rebut the comments calling for the alignment of QRM on QM, it is likely that they chose to acquiesce for political reasons. Accommodation was facilitated by, in the years following the proposed rule, by replacement of “hawk” regulators such as Sheila Bair. Accommodation is also a response to the way that courts have interpreted the notice and comment provisions of the Administrative Procedure Act—requiring, for example, that agencies respond to comments in revised rules. Even absent an obligation to comply with a comment, if an agency chooses not to rebut it, what can it do but alter the rule in accordance with the commenters’ wishes, lest it be overturned as arbitrary and capricious in court?

A fifth observation is that political expenditures benefit from organization. Public relations/consulting firms provide organization as well as engaging in direct lobbying. We pointed to how Rasky Baerlin organized the Coalition for Sensible Housing Policy.Footnote 31 Rasky Baerlin also organized the trade association U.S. Mortgage Insurers.Footnote 32 Forming a coalition is not a new strategy, of course. The National Consumer Bankruptcy Coalition was a coordinated effort to “reform” consumer bankruptcy law.Footnote 33 But we emphasize that uncoordinated lobbying may not represent productive expenditure.

Finally, we note how different aspects of a complex policy may or may not map onto underlying ideological cleavages in contemporary U.S. politics. As noted above, the opposition to the proposed down payment rule was broad-based and bipartisan. Other policy solutions—such as shrinking GSEs or principal reduction—have a distinctly partisan edge. The extent to which the policy in question maps to partisan divisions has important consequences for a policy's viability, as well as the chances that such a policy will make it onto the agenda in the first place. A president backed by majorities in both houses of Congress will naturally employ a different set of levers than one facing a hostile Congress. A president facing a hostile Congress can still maintain the status quo—with respect to the GSEs for example—if opponents fail to have veto-proof majorities. Bankruptcy “reform” required nine years of coalition activity partly because of opposition of the Clinton administration and some Senate Democrats. The bipartisan adjustment of QM and QRM, by contrast, was almost immediate.