Introduction

Do countries participating in an International Monetary Fund (IMF) program witness an improvement in international investor sentiment? When a crisis-ridden country participates in an IMF program, how would an international investor seeking long term investment react? While there is a large body of literature examining the consequences of IMF programs, systematic empirical evidence on IMF effects, specifically on investor perception per se, remains scant. Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) involve either building or acquiring productive capacity usually with a long-term perspective. Thus, investors keenly observe the policy outcomes in their potential investment destination and update their perceptions about the desirability of the planned investments and consequently reallocate resources. Therefore, if participating in an IMF program arrests the fall in creditworthinessFootnote 1 and attracts foreign capital,Footnote 2 then its impact on investor perception should have been positive in the first place. However, the literature on the relationship between IMF programs and FDI is controversial. While the argument is still contentious,Footnote 3 many believe that a country's participation in an IMF program is associated with a decline in FDI.Footnote 4 While much of the previous work looks at FDI flows, this paper examines the impact on investor confidence, which is a more direct test of the theoretical mechanism.

The IMF programs are designed to encourage competitiveness and promote macroeconomic stability and subsequent economic growth by imposing conditions that require governments to undertake a series of economic reform measuresFootnote 5 that are perceived favorably by foreign investors. Thus, countries participating in IMF programs should be able to attract more FDI as it increases the prospects of economic stability and thereby creates a conducive business climate. This is popularly known as the “catalytic effect.” However, empirical support for catalytic hypothesis with reference to FDI is scarce. Biglaiser and DeRouen (Reference Biglaiser and DeRouen2010) conducted the only study that finds convincing, positive evidence on the effect of IMF program on U.S. FDI inflows. While a number of studies find a negative effect of IMF programs on FDI, few studies have found either a positive effect or no significant effect.Footnote 6 I argue that the reason for these divergent results could be due to neglecting the role of an important element of IMF lending: conditionality. Arguably, this is a significant shortcoming of the existing literature on IMF and FDI, which I attempt to address in this study. By accepting a large number of conditions imposed by the IMF, the government's commitment to undertake economic reforms to restore macroeconomic stability is significantly enhanced. Moreover, in countries dogged by crises, investors shy away from investing not only because of economic turmoil but also because the credibility of the government's commitment to reforms becomes questionable.Footnote 7 Accepting IMF conditions involves a huge ex ante and ex post political cost for the incumbent government. Despite these political costs, accepting IMF conditions signals the government's intent and commitment to reforms. By accepting prior actions and performance criteria conditions—the set of conditions required to be complied before disbursements are made—further enhances the credibility of the government's commitment to economic reform. I test these contentions using the Investment Profile index compiled by the International Country Risk Guide which serves as a measure of investor response in a panel data setting covering 166 countries during the 1992–2013 period (twenty-two years). To measure the influence of the Fund, I use the IMF's Monitoring of Fund Arrangements (MONA), which contains many cases compared to what previous datasetsFootnote 8 have covered on conditionalities. I use disaggregated data by the type of policy conditions—namely, prior actions and performance criteria—as well as structural benchmarks and number of quarters in a year a country has been under the arrangement for each of these specific conditions.

Estimating the impact of IMF conditions on investor perception is not straightforward because countries may not only opt into an IMF program but also into conditionality.Footnote 9 I utilize a Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) in a conditional mixed-process (CMP) framework, which estimates three simultaneous equations combining the instrumental variable approach to address the endogeneity of both IMF program participation and that of IMF conditionality. I find that a positive impact on investor confidence is driven by prior actions and performance criteria conditions. These findings are in stark contrast to those who argue that IMF conditional programs are akin to swallowing a bitter pill. In fact, my results demonstrate that the so-called bitter pill may act as a palliative. These results are robust in regards to controlling for selection bias, fixed effects, and endogeneity. These results also survive a variety of robustness checks.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: section 1 discusses the theory and presents the testable hypotheses. Section 2 describes the data, estimation, and identification strategy. Section 3 presents the results and discussion, and section 4 concludes.

Arguments and hypotheses

The literature examining the effects of IMF programs on capital flows focuses on the “catalytic effect” in which participation in IMF programs helps spur capital inflows into the country. There are two dimensions of the catalytic effect, namely, signaling and commitment effects. Countries use IMF program as a signaling strategy towards the international investor community (and rating agencies, as shown by Gehring and Lang, Reference Gehring and Lang2018) to signal government's commitment to undertake economic reform measures. But the question remains as to why the government doesn't enact the policy without entering the IMF program. I argue that history provides some guidance here. Generally, it has been observed that countries carry out economic reforms only when they have their backs against the wall. That is because economic reforms entail costs that are upfront and concentrated on a few groups. But the economic benefits are felt only in the medium- to long-run as they take time to materialize.Footnote 10 Krugman (Reference Krugman1998) argues that political cost to undertake economic reforms are extremely high and most governments often resist reforms. Sharma (Reference Sharma2012) finds empirical support that countries undertake radical reforms when they are faced with a severe economic crisis. He provides anecdotal evidence on how several countries embarked on structural reforms when confronted with a crisis. Examples include India (1981, 1991), South Korea (1998), Indonesia (1998), and Argentina (2002), among others. After a hard landing in 1997–98, these countries converted the crisis into an opportunity to reform and clean up the banking system, improve export competitiveness, and restore fiscal order. The IMF was then loathed in East Asia and castigated globally for imposing “austerity” in return for bailouts. Since then, those Southeast Asian economies have undergone many painful structural reforms. But that really set the stage for a buoyant economic recovery over the next fifteen years. Therefore, undertaking economic reforms become even more important for countries reeling under severe financial and economic distress. While Vreeland (Reference Vreeland2007) points to recidivism as the main reason for participation in IMF programs, Jensen (Reference Jensen2004) argues that a country is more likely to participate in an IMF program if its economic condition seems distressing largely due to unsustainable levels of external debt, fiscal deficit, balance of payments crisis, and exchange rate problems. These unfavorable conditions have a negative influence on investor sentiment, therefore forcing the countries to participate in IMF programs. As countries participate in IMF programs, governments hope that introducing economic policy reforms will not only improve the investment climate but also increase the prospects of economic revival. Thus, the focal point of the catalytic hypothesis is that investors would react positively to reform measures resulting in the revival of investor sentiment, which translates into FDI thereafter. The empirical evidence on the catalytic hypothesis, however, remains contentious. Biglaiser and DeRouen (Reference Biglaiser and DeRouen2010) find that countries under IMF programs tend to attract more FDI from U.S. investors. But Moon and Woo (Reference Moon and Woo2014) find that countries that are strategically closer to the United States attract less FDI with IMF programs. This lowers the credibility of the IMF program intended to reform the economy, thus, sending negative signals to international investors. However, Woo (Reference Woo2013) finds support in favor of the catalytic effect as conditions attached in the IMF programs increase FDI inflows. Other studies also find support for the catalytic hypothesis but only under certain circumstances, such as countries with weak economic fundamentals.Footnote 11 Interestingly, Bird and Rowlands (Reference Bird and Rowlands2002), Barro and Lee (Reference Barro and Lee2005), and Edwards (Reference Edwards2006) find that participating in IMF programs send a negative signal to international investors leading to capital flight. Likewise, Jensen (Reference Jensen2004) finds that countries participating in IMF programs receive 25 percent less FDI compared to countries that have not participated in the IMF's program. These findings are in stark contrast to the catalytic hypothesis.Footnote 12

Dreher and Rupprecht (Reference Dreher and Rupprecht2007) and Boockmann and Dreher (Reference Boockmann and Dreher2003) provide plausible explanation as to why the catalytic effect may not always materialize. They find that countries participating in IMF programs do not always carryout economic reforms because of the time inconsistency problem. The IMF provides governments the perverse incentives to introduce half-baked reforms ex ante to receive the first installments of a loan only to renege on the promise made to carry forward the reforms in the future. Moreover, from a theoretical and empirical point of view, the impact of IMF programs on macroeconomic outcomes remains contentious.Footnote 13 While some find that the IMF's involvement is associated with an improvement in macroeconomic outlook,Footnote 14 others find that the overall impact of IMF programs remain negative.Footnote 15 Highlighting the impact of economic reforms, Campos and Kinoshita (Reference Campos and Kinoshita2008) find that countries that embark on economic reforms tend to attract more FDI. Thus, if involvement in the IMF inhibits governments from initiating reforms, then the credibility of governments’ commitment to economic reforms becomes questionable.

Studies arguing in favor of catalytic hypothesis presume that the commitment to economic reform by the government participating in IMF programs is credible. But Marchesi and Thomas (Reference Marchesi and Thomas1999) show that IMF distinguishes between governments based on how committed they are to undertake tough economic reforms, which are often politically costly for the incumbent. Thus, the role of conditionality becomes crucial. Governments committed to economic reforms can use the conditions imposed by the IMF as a credible signaling device to the international investor community. Conditions pushed by the IMF usually entail (i) fiscal austerity by increasing taxes while cutting government expenditures, (ii) tight monetary policy by raising interest rates and at the same time reducing new credit, and (iii) even devaluation when deemed necessary.Footnote 16 The IMF justifies the practice of conditionality as insurance, otherwise their loan repayments would be at risk of default and thereby affect their prospective lending activities.Footnote 17

Although conditionalities are at the center of the controversy often associated with the IMF, they enhance the credibility of government's commitment to reform. I provide three explanations to this effect. First, participating in an IMF program involving a laundry list of conditions to be implemented entails ex ante political cost. Usually, politicians perceive an electoral cost in committing and adopting economic reforms. A popular perception among policy makers is that governments are afraid of losing votes due to the short-run political costs associated with introducing tough economic reforms. There is a large body of anecdotal evidence suggesting that IMF induced reforms face severe resistance from various groups in the society who perceive themselves to be losers from such policies.Footnote 18 Powerful interest groups who are certain to lose after implementing reforms may lobby hard to block them.Footnote 19 Several studies report empirical evidence specifically on the political costs of IMF induced reforms. While Smith and Vreeland (Reference Smith, Vreeland, Ranis, Vreeland and Kosack2003) conclude that IMF programs affect survival rates of political leaders, Dreher and Vaubel (Reference Dreher2004) find that IMF program participation affects the re-election probability of incumbent governments. Also, Dreher and Gassebner (Reference Dreher and Gassebner2012) find that IMF involvement is associated with government crises involving cabinet changes, or the replacement of entire governments. Despite these huge, up-front political costs, commitment to implement tough IMF conditionalities does send a powerful signal to both domestic constituencies and international communities that the incumbent government is willing to put its political capital at stake to revive the economy. Thus, agreeing to implement a list of tough IMF conditionalities enhances the government's credibility to reform, thereby resurrecting sagging investor sentiment.

Second, once committed to implementing reform policies as a part of IMF conditions, reneging on those commitments might incur ex post political costs. The first such ex post cost would be to cease the disbursement of future loan tranches by the IMF and even restraining itself from giving further loans to the country. As a result, the reputational damage for the government both domestically and internationally could be huge. For the domestic constituency, this could send a signal of government's incompetence in managing to pull the country out of a rut. Globally, the suspension of IMF loans abruptly might hurt the prospects of getting new loans from other donor agencies and private investors. The government would certainly find that the financial market, banks, and the other international financial institutions refusing to lend money at reasonable rates (or would demand an exuberantly high risk premium), unless the government convinces them by undertaking pretty much the same set of reforms that the IMF asked it to carry out anyway. In fact, life would be much tougher for countries, especially crises-ridden countries, without the IMF than with the IMF prescription of “conditionalities.” As investors trust the implementation of reform policies monitored by the IMF staff, their perception of the country as an investment destination starts to improve.

Finally, it has been argued that the reform-oriented governments often face domestic political opposition.Footnote 20 Vreeland (Reference Vreeland2003, 39) points out that, “governments use IMF agreements to push through policies that otherwise would be defeated. Conditions allow governments to tie their hands and tip the political scales in favor of economic reform.” The governments, which intend to pursue a reform agenda to signal to foreign investors, accept conditionalities imposed by the IMF to not only push reform policies forward, but also to use those conditions to increase governments’ bargaining power with those opposed to reforms.Footnote 21 Thus, governments concerned about sending a strong signal to recuperate from drooping investor sentiment on the one hand and tackling domestic constituents’ opposition to reforms on the other, will tie their policy preference to the IMF conditions to push contentious policy reforms forward. In fact, in the case of labor market reforms, Rudra and Nooruddin (Reference Rudra and Nooruddin2014) contend that governments deliberately initiate labor policy reforms using labor related IMF conditions to weaken the historical stranglehold of privileged labor. The literature provides evidence that governments use the IMF as a “political cover” to push economic reforms to signal to investors that they are committed to reforming the economy.Footnote 22 I derive the following hypothesis from this discussion:

Hypothesis 1:

International long-term investor sentiment for a country improves with an increase in the number of IMF conditions attached.

Investors may not, however, react to countries participating in IMF program, per se, but are rather interested in the type and nature of the conditionalities attached. IMF conditions are classified into three types, namely, prior actions, performance criteria, and structural benchmarks. The prior action conditions are those that the recipient countries are expected to fulfill prior to the approval of the agreement and the necessary financing of the program by the IMF's executive board. The key feature of prior action conditions is the non-compliance. A country would not receive any funds if they did not comply with the conditions under prior actions. Under the performance criteria, the conditions set by the executive board are required to be met by the recipient country by a specific date as per the agreement. Performance criteria conditions are measured by the IMF on a quarterly basis with specific variables that help monitor the progress. Thus, from time to time, credit disbursements are released in tranches only after full evaluation of compliance on performance criteria conditions. Like prior actions, compliance is the key feature that needs to be met before disbursements are made. The structural benchmark conditions cover specific structural reforms. Because most of the structural reforms are neither directly measurable nor quantifiable, non-compliance of these conditions does not result in either halting loan disbursements or termination of the program.

Accepting IMF conditions under prior actions and performance criteria can affect investor sentiment positively because it displays the willingness of a government for reforms. While reneging on the conditions under performance criteria can halt further loan disbursements, failure to implement prior action conditions in the first place, even before the loan is disbursed, means exiting from the program. On the other hand, no such risk is associated with the non-compliance of structural benchmark conditions. However, this does not mean that structural benchmarks are not credible, but that they are not important either for the investor simply because they are often difficult to quantify, tough to monitorFootnote 23 and therefore enforcement by the IMF staff is lax.Footnote 24 Furthermore, an unmet performance criteria condition requires a formal waiver from the Executive Board of the Fund, a structural benchmark condition does not need a formal waiver if unmet. Goldstein suggests, “Failure to meet structural benchmarks conveys a negative signal but does not automatically render a country ineligible to draw, instead, a decision about eligibility would be judgmental.”Footnote 25 Given the non-punitive nature of the structural benchmarks, I argue that accepting prior action and performance criteria conditions can significantly enhance the credibility of a government's commitment to long-term investors on undertaking policy reforms to restore economic order. To summarize the arguments:

Hypothesis 2:

International long-term investor sentiment for a country improves with an increase in number of performance criteria and prior action conditions attached.

Data and methods

Model specification

I use panel data covering 166 countries (see appendix 1 for list of countries) from 1992–2013 (twenty-two years) to examine the impact of IMF conditions on investor perception. The study period begins in 1992 when the IMF conditionality data coverage was made available by the IMF's MONA database. I estimate a parsimonious model with the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) controlling for country (ν i) and year (λ t) fixed effects with standard errors clustered at the country level.

$$IP_{it} = \varphi_i + \beta_{1} IMF\_cond_{it} + \beta_{2}Z_{it} + \nu_i + \lambda_t + \omega_{i_t} $$

$$IP_{it} = \varphi_i + \beta_{1} IMF\_cond_{it} + \beta_{2}Z_{it} + \nu_i + \lambda_t + \omega_{i_t} $$Wherein, the dependent variable, IP it denotes the investment profile index for country i in the year t sourced from the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG). The investment profile index measures the experts’ opinion on the government's general attitude towards foreign investments, especially the FDI. This is a relatively close proxy of the perception of long-term foreign investors because it gauges whether foreign investors with a long-term perspective are interested in investing in the country.Footnote 26 Gupta, Kangur, Papageorgiou, and Wane (Reference Gupta, Kangur, Papageorgiou and Wane2011) at the Fiscal Affairs Department and Strategy, Policy and Review Department of the IMF consider this measure to capture government's attitude towards investments. The index is compiled from the observations of in-house country experts of the ICRG based on information gathered from foreign investors seeking direct investments, making them ideal for this study. The index measures the government's attitude on contract viability, profit repatriation, and payment delays. The rating assigned is on the scale of 0–12 in which the maximum score denotes a favorable government attitude towards foreign investors with a long-term perspective.Footnote 27 While the mean value of the index is 7.8, the standard deviation is 2.5, suggesting a considerable variation among countries in the sample.

The  $IMF\_cond_{it}$ is the main variable of interest capturing the number and type of IMF conditions. It is noteworthy that measuring IMF conditions is not straightforward. The information on conditions is made available by the IMF's MONA database. The data on conditions made available by the IMF is only from 1992. The MONA database simply lists the number of conditions a country has been under in various years. Thus, neither the data nor the information on the precise severity of conditions is available.Footnote 28 In the absence of severity of conditions, I focus on disaggregating the total number of conditions country i has been under during its tenure in an IMF program by three different types. These three types, as discussed earlier, are performance criteria, prior action, and structural benchmark conditions. Under the performance criteria conditions, the release of a loan installment is conditional upon performance of the government on fulfilling the agreed upon conditions. These conditions are subject to quarterly evaluations by the IMF staff. Those conditions, which the government is required to undertake in order to receive first loan disbursement, are the prior actions. Finally, those conditions aimed at structural reforms, which are often difficult to quantify and thus tough to monitor, are the structural benchmarks. A simple back of the envelope calculation shows that there are roughly twenty-one performance criteria conditions per country-year, followed by nineteen structural benchmark conditions and six prior actions conditions per country-year during 1992–2013 period. During this period, performance criteria conditions contributed 46 percent of the total IMF conditions.

$IMF\_cond_{it}$ is the main variable of interest capturing the number and type of IMF conditions. It is noteworthy that measuring IMF conditions is not straightforward. The information on conditions is made available by the IMF's MONA database. The data on conditions made available by the IMF is only from 1992. The MONA database simply lists the number of conditions a country has been under in various years. Thus, neither the data nor the information on the precise severity of conditions is available.Footnote 28 In the absence of severity of conditions, I focus on disaggregating the total number of conditions country i has been under during its tenure in an IMF program by three different types. These three types, as discussed earlier, are performance criteria, prior action, and structural benchmark conditions. Under the performance criteria conditions, the release of a loan installment is conditional upon performance of the government on fulfilling the agreed upon conditions. These conditions are subject to quarterly evaluations by the IMF staff. Those conditions, which the government is required to undertake in order to receive first loan disbursement, are the prior actions. Finally, those conditions aimed at structural reforms, which are often difficult to quantify and thus tough to monitor, are the structural benchmarks. A simple back of the envelope calculation shows that there are roughly twenty-one performance criteria conditions per country-year, followed by nineteen structural benchmark conditions and six prior actions conditions per country-year during 1992–2013 period. During this period, performance criteria conditions contributed 46 percent of the total IMF conditions.

I employ the official count of the number of conditions included under each type for country i in year t during the 1992–2013 period. Unfortunately, due to lack of information on the exact timing of entry of (some of) these conditions,Footnote 29 I calculate the sum of all of the conditions under performance criteria, prior action, and structural benchmarks, respectively, during each of the year(s) an IMF program is in force. In order to avoid over-counting and duplicity, I follow Dreher et al. (Reference Dreher, Sturm and Vreeland2015) to divide all three conditions by the number of quarters during each of the year(s) an IMF program is in force. The number of conditions per quarter in the mid-1990s increased, followed by a steep decline during the early 2000s economic boom years. Post-2008 financial crisis, there is a steady increase in conditions per quarter. Previous studies have used the number of IMF conditions as a proxy for the severity of conditions imposed by the IMF.Footnote 30

The vector of control variables (Z it) includes other potential determinants of investor perception, which are obtained from the extant literature on the subject.Footnote 31 Following others, I include GDP per capita (logged) as a proxy for the level of development in the host country. I expect richer countries to enjoy a positive investor perception. I include a measure of regime type based on the Marshall and Jaggers (Reference Marshall and Jaggers2002) Polity IV index coded on a scale of −10 to +10. I transform the coding into a 0–20 scale, where a higher value represents full democracy (which is +10 on Polity IV index). This variable is the proxy for property rights protection and stability. Previous studies find that investor confidence is likely to be higher with democratic regimes.Footnote 32 Similarly, previous studies have also found that long-term investors prefer regimes with strong property rights and a low corruption reputation. A measure of trade openness capturing total trade as a share of GDP sourced from the UNCTAD statistics 2016 is included. A civil conflict measure, which is dummy coded 1 for each year a country has at least one active conflict with twenty-five battle deaths, obtained from Uppsala Conflict Data Program 2014, see Gleditsch, et al. (Reference Gleditsch, Wallensteen, Eriksson, Sollenberg and Strand2002), is also controlled. Finally, I include a dummy capturing debt, banking, and currency crises events sourced from Laeven and Valencia (Reference Laeven and Valencia2013). Reinhart, Rogoff, and Savastano (Reference Reinhart, Rogoff and Savastano2003) find that excessive levels of external debt and threat of default have significant negative influence on investor perception. Apart from this, I also include a measure of inflation.

Endogeneity

Estimating the impact of IMF conditions on investor perception is not straightforward because entry into the IMF program in the first place is not a random event. Countries decide based on macroeconomic, financial factors whether to participate in the IMF lending program, thus, leading to a self-selection problem. Therefore, estimating Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) models would lead to selection bias. To circumvent this problem, previous studies have used the Heckman regression estimator,Footnote 33 which takes account of the determinants of a country's decision to enter an IMF program, the non-random treatment assignment, and models it in non-linear specification. However, it is unclear whether countries also self-select into conditions. Some argue that conditions are requested by countries.Footnote 34 In this study, we are faced with the problem of self-selection into conditions by countries, because if the intent of the incumbent government is to send a credible signal to international investors, then such a government would be more than willing to accept more conditions. In fact, this argument is in line with Vreeland (Reference Vreeland2003) who argue that in order to counter domestic political opposition to policy reforms, governments might seek IMF conditions. If this is the case, then one could expect the IMF to be less lenient towards countries in crises in imposing the conditions, thereby enhancing the prospects of implementation of much required economic policy reforms. Thus, the equation (1) faces the problem of endogeneity in which there are two endogenous variables, namely, IMF program participation and conditionalities of the IMF. As Stubbs et al. (Reference Stubbs, Kentikelenis, Reinsberg and King2018, 15) points out, “if one wishes to distinguish effects of conditionality from other aspects of IMF programs, but is also interested in how this compares to cases without an IMF program, then both a measure of conditionality and a binary indicator for IMF participation should be included in the model.” We follow Stubbs et al. (Reference Stubbs, Kentikelenis, Reinsberg and King2018), Forster et al. (Reference Forster, Kentikelenis, Reinsberg, Stubbs and King2019), and Lang (Reference Lang2016) to include both IMF program participation and conditionalities into equation (1) with the assumption that countries self-select not only into the IMF's program but also conditionality. Estimating equation (1), which include two self-section endogenous variables, requires a three, simultaneous equation estimator (three-stage least squares, 3SLS). However, due to non-linearity of IMF program participation, estimating three simultaneous equations using 3SLS may not be a viable option. Following Stubbs et al. (Reference Stubbs, Kentikelenis, Reinsberg and King2018) and Forster et al. (Reference Forster, Kentikelenis, Reinsberg, Stubbs and King2019), I use utilize a Maximum Likelihood Estimator (MLE) in a conditional mixed-process (CMP) framework implemented by David Roodman's (Reference Roodman2011) cmp command in STATA 15. The underlying concept of the CMP framework is that it can estimate three equations jointly when the errors in the equations are correlated. So, the multi-equation model consists of three simultaneous equations, which combine the instrumental variable approach to address the endogeneity of both IMF program participation and conditionality, as shown below:

$${\widehat {IMF}}_{it} = \varphi_i + \beta_1IV_{it} + \beta_2Z_{it} + \lambda_t + \omega_{i_t} $$

$${\widehat {IMF}}_{it} = \varphi_i + \beta_1IV_{it} + \beta_2Z_{it} + \lambda_t + \omega_{i_t} $$ $${\widehat {IMF\_cond}}_{it} = \varphi_i + \beta_1IV_{it} + \beta_2Z_{it} + \nu _i + \lambda _t + \omega_{i_t} $$

$${\widehat {IMF\_cond}}_{it} = \varphi_i + \beta_1IV_{it} + \beta_2Z_{it} + \nu _i + \lambda _t + \omega_{i_t} $$ $$IP_{it} = \varphi_i + \beta_1{\widehat {IMF}}_{it} + \beta_2{\widehat {IMF\_cond}}_{it} + \beta_3Z_{it} + \nu _i + \lambda_t + \omega_{i_t} $$

$$IP_{it} = \varphi_i + \beta_1{\widehat {IMF}}_{it} + \beta_2{\widehat {IMF\_cond}}_{it} + \beta_3Z_{it} + \nu _i + \lambda_t + \omega_{i_t} $$ Here, equation (4) is the outcome equation in which IP it is the investment profile index for country i in the year t, which is the outcome variable of interest. I use the predicted values of IMF program participation ( ${\widehat {IMF}}_{it}$) derived from equation (2) and the fitted values of IMF conditions per quarter (

${\widehat {IMF}}_{it}$) derived from equation (2) and the fitted values of IMF conditions per quarter ( $IMF\_cond_{it}$), namely, prior actions, performance criteria, and structural benchmarks, separately from equation (3). The variables IV it in equation (2) and (3) denotes exogeneous instrumental variables discussed below.

$IMF\_cond_{it}$), namely, prior actions, performance criteria, and structural benchmarks, separately from equation (3). The variables IV it in equation (2) and (3) denotes exogeneous instrumental variables discussed below.

In equation (2),  ${\widehat {IMF}}_{it}$ is a discrete variable with value 1 in year t, if country i is under an IMF program for at least five months in a financial year, and 0 otherwise. The data is sourced from Boockmann and Dreher (Reference Boockmann and Dreher2003) and Dreher (Reference Dreher2006). Out of 166 countries, about 104 countries were under IMF programs during the 1992–2013 period. The maximum number of countries under an IMF program was sixty-eight in 1996, while a minimum of thirty-three countries were registered in 2013. The average number of countries in IMF programs during this study period is about fifty-two.

${\widehat {IMF}}_{it}$ is a discrete variable with value 1 in year t, if country i is under an IMF program for at least five months in a financial year, and 0 otherwise. The data is sourced from Boockmann and Dreher (Reference Boockmann and Dreher2003) and Dreher (Reference Dreher2006). Out of 166 countries, about 104 countries were under IMF programs during the 1992–2013 period. The maximum number of countries under an IMF program was sixty-eight in 1996, while a minimum of thirty-three countries were registered in 2013. The average number of countries in IMF programs during this study period is about fifty-two.

The main variable of interest in equation (2) is the IV it, which is the proposed instrumental variable. Following Forster et al. (Reference Forster, Kentikelenis, Reinsberg, Stubbs and King2019) and Lang (Reference Lang2016), I use an interaction between the probability of a recipient country being in an IMF program in year t and the liquidity ratio of the IMF defined as total assets divided by the total liabilities,  ${\bi {iv}} = \big ( {{1 \over {22}}\; \mathop \sum \limits_{y = 1}^{22} {\bi p}_{{\bi it}}\; \times {[Liquidity\; ratio]}_{\bi t}} \big)$. The data on probability of a recipient country being in an IMF program (pit), which is a share of years a country has been under an IMF program, comes from Dreher (Reference Dreher2006) and I compute the liquidity ratio using the information from the IMF's yearly balance sheets. I believe that this variable is exogeneous because previous research shows that the number of countries participating in an IMF program is determined by the IMF's budget constraint.Footnote 35 In years with resource abundance, i.e., a higher liquidity ratio, the IMF is likely to assist more countries and vice versa. It could also mean that countries that have been in IMF program longer in the past are more likely to enter the program in the future, especially when the IMF's liquidity is abundant (Bird et al., Reference Bird and Rowlands2002). This identifying assumption is similar to that of Forster et al. (Reference Forster, Kentikelenis, Reinsberg, Stubbs and King2019), Vadlamannati et al. (Reference Vadlamannati, Li, Brazys and Dukalskis2019), Reinsberg et al. (Reference Reinsberg, Kentikelenis, Stubbs and King2019), Brazys and Vadlamannati (Reference Brazys and Vadlamannati2018), Dreher et al. (Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks and Strange2017), and Dreher and Langlotz (Reference Dreher and Langlotz2017), which was first adopted by Nunn and Qian (Reference Nunn and Qian2014) in which a time-varying exogenous variable is interacted with an endogenous variable that varies only across countries to produce an instrument that then varies across countries and over time. Thus, the excludability assumption is that the investor perception index for countries with differing levels of past IMF exposure will not be affected differently by changes in the IMF liquidity ratio, other than its impact on IMF program participation.

${\bi {iv}} = \big ( {{1 \over {22}}\; \mathop \sum \limits_{y = 1}^{22} {\bi p}_{{\bi it}}\; \times {[Liquidity\; ratio]}_{\bi t}} \big)$. The data on probability of a recipient country being in an IMF program (pit), which is a share of years a country has been under an IMF program, comes from Dreher (Reference Dreher2006) and I compute the liquidity ratio using the information from the IMF's yearly balance sheets. I believe that this variable is exogeneous because previous research shows that the number of countries participating in an IMF program is determined by the IMF's budget constraint.Footnote 35 In years with resource abundance, i.e., a higher liquidity ratio, the IMF is likely to assist more countries and vice versa. It could also mean that countries that have been in IMF program longer in the past are more likely to enter the program in the future, especially when the IMF's liquidity is abundant (Bird et al., Reference Bird and Rowlands2002). This identifying assumption is similar to that of Forster et al. (Reference Forster, Kentikelenis, Reinsberg, Stubbs and King2019), Vadlamannati et al. (Reference Vadlamannati, Li, Brazys and Dukalskis2019), Reinsberg et al. (Reference Reinsberg, Kentikelenis, Stubbs and King2019), Brazys and Vadlamannati (Reference Brazys and Vadlamannati2018), Dreher et al. (Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks and Strange2017), and Dreher and Langlotz (Reference Dreher and Langlotz2017), which was first adopted by Nunn and Qian (Reference Nunn and Qian2014) in which a time-varying exogenous variable is interacted with an endogenous variable that varies only across countries to produce an instrument that then varies across countries and over time. Thus, the excludability assumption is that the investor perception index for countries with differing levels of past IMF exposure will not be affected differently by changes in the IMF liquidity ratio, other than its impact on IMF program participation.

In choosing the determinants of a country's entry into an IMF program (Z it) in equation (2), I follow prominent studies in the literature—Dreher et al. (Reference Dreher, Sturm and Vreeland2015), Dreher et al. (Reference Dreher, Sturm and Vreeland2009), Dreher and Vaubel (Reference Dreher2004), Vreeland (Reference Vreeland2003, Reference Vreeland2007), and other comprehensive evaluations of early studies on IMF lending (Barro and Lee, Reference Barro and Lee2005). Accordingly, I include GDP per capita (log), measured in 2000 USD constant prices. Richer countries are less likely to participate in IMF programs. Likewise, I also control for the rate of GDP growth in the selection models. To capture the country's vulnerability to internal and external crises, I include two measures. First is the inflation sourced from the World Development IndicatorsFootnote 36 and second, is a dummy variable indicating whether a country has experienced all or one of three crises, viz., currency crisis, debt crisis, and systemic banking crisis, sourced from Laeven and Valencia (Reference Laeven and Valencia2013). Following Vreeland (Reference Vreeland2007), I include a measure of democracy, as discussed earlier, and also include a measure of new democracy, which takes the value 1 for the first five years since a country turns democratic (i.e., registering a score of +5 or more on the Polity IV index). New democracies are vulnerable to economic crises and are more likely to participate in IMF programs. I include a measure of trade openness as countries more open to trade are less likely to participate in IMF programs.Footnote 37 It is argued that resource rich countries are less likely to participate in IMF programs because of the windfall profits from resource rents.Footnote 38 I include a measure of natural resource rents as a share of GDP sourced from the World Development Indicators. Accordingly, the World Bank defines resource rents as unit price minus the cost of production times the quantity produced. Following Vreeland (Reference Vreeland2007), I include a count measure of past participation in the IMF program to capture recidivism. Finally, previous studies found a strong relationship between voting patterns in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) and IMF lending.Footnote 39 I use the UNGA voting alignment index developed by Strezhnev and Voeten (Reference Strezhnev and Voeten2012). This measure codes votes in agreement with the United States as 1, votes in disagreement as 3, and abstentions as 2. The resulting numbers are then divided by the total number of votes in the UNGA each year, yielding a measure that is coded between 0 and 1. Dreher and Sturm (Reference Dreher and Sturm2012) argue that major shareholders like the United States and its allies use their voting power in the IMF to disburse loans to countries to pursue their international political goals. Lending through the IMF allows the United States to bare only a fraction of the cost and reduce the transaction costs vis-à-vis using its own resources. Note that in IMF program equation (2), I include year fixed effects but not country-specific fixed effects due to the incidental parameter problem.Footnote 40 Lastly, equation (2) controls for year fixed effects and standard errors are clustered at the country level. The descriptive statistics on all the variables are in appendix 2, and definition and data sources are provided in appendix 3.

In equation (3),  ${\widehat {IMF\_cond}} _{it}$ are the three types of conditions, namely, prior actions per quarter, performance criteria per quarter, and structural benchmarks per quarter. The vector (Z it) includes control variables from the outcome equation (4). Note that in equation (3), I control for both country and year fixed effects and standard errors are clustered at the country level. The IV it is the instrumental variable, which is three different interaction variables between the probability of a recipient country with prior action, performance criteria, and structural benchmark conditions in year t, respectively, and (log) of total number of countries in an IMF program in year t,

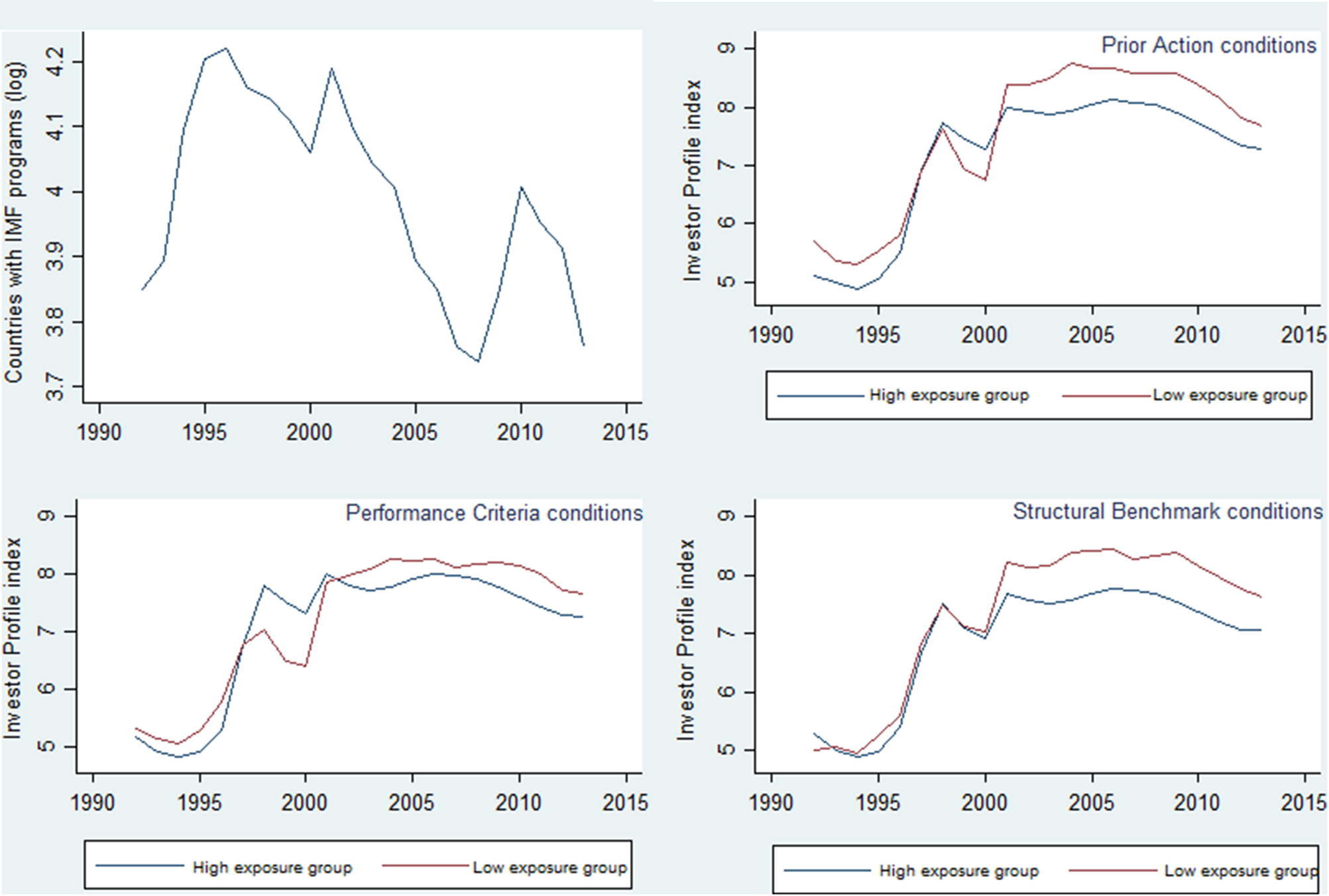

${\widehat {IMF\_cond}} _{it}$ are the three types of conditions, namely, prior actions per quarter, performance criteria per quarter, and structural benchmarks per quarter. The vector (Z it) includes control variables from the outcome equation (4). Note that in equation (3), I control for both country and year fixed effects and standard errors are clustered at the country level. The IV it is the instrumental variable, which is three different interaction variables between the probability of a recipient country with prior action, performance criteria, and structural benchmark conditions in year t, respectively, and (log) of total number of countries in an IMF program in year t,  ${\bi iv} = \bigg ( {{1 \over {22}}\; \mathop \sum \limits_{y = 1}^{22} {\bi p}_{{\bi it}}\; \times {[No.\; of\; countries\; in\; IMF]}_{\bi t}} \bigg).$ The data on both measures is sourced from Dreher (Reference Dreher2006). Once again, past studies show that as more countries participate in an IMF program the budget constraints on the IMF increases. This, in turn, results in a greater number of conditions on recipient countries as budget constraints of the IMF become binding.Footnote 41 Indeed, figure 1 captures the correlation between number of countries in an IMF program and total conditions in panel 1 and conditions disaggregated by type in rest of the panels. As seen, except for structural benchmarks, on average, more conditions are attached by the IMF in the years when more countries require IMF program support.

${\bi iv} = \bigg ( {{1 \over {22}}\; \mathop \sum \limits_{y = 1}^{22} {\bi p}_{{\bi it}}\; \times {[No.\; of\; countries\; in\; IMF]}_{\bi t}} \bigg).$ The data on both measures is sourced from Dreher (Reference Dreher2006). Once again, past studies show that as more countries participate in an IMF program the budget constraints on the IMF increases. This, in turn, results in a greater number of conditions on recipient countries as budget constraints of the IMF become binding.Footnote 41 Indeed, figure 1 captures the correlation between number of countries in an IMF program and total conditions in panel 1 and conditions disaggregated by type in rest of the panels. As seen, except for structural benchmarks, on average, more conditions are attached by the IMF in the years when more countries require IMF program support.

Figure 1: Countries with IMF program & Mean number of conditions by type

The validity of the selected instruments in both equations (2) and (3) depends on two conditions. The first is instrument relevance, which is that the instrument must be correlated with the explanatory variable in question—otherwise it has no power. In the case of linear estimations, Bound, Jaeger, and Baker (Reference Bound, Jaeger and Baker1995) suggest examining the joint F-statistic on the excluded instrument in the first-stage regression. The selected instrument would be relevant when the first stage regression model's joint F-statistics is above 10.Footnote 42 Second, the selected instrument should not differ systematically with the error term in the second stage of the equation, i.e. [ωit |IVit] = 0, meaning the selected instrument should not have any direct effect on the outcome variable of interest—investor perception index, but only indirectly via the instrumented variables. The excludability of both our instruments rests on the assumption that the probability of conditions will not be affected differently by changes in number of countries in IMF programs in the past, other than through the impact of types of conditions. Following Stubbs et al. (Reference Stubbs, Kentikelenis, Reinsberg and King2018), Dreher et al. (Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks and Strange2017), I test this assumption graphically by plotting both IMF's liquidity ratio and countries in IMF programs (log) over time, and ICRG's investor protection index by high and low exposure groups. These results, discussed in section 3 in detail, suggest no apparent parallel trend between liquidity ratio and countries in IMF programs (log) over time and investor perception index of high exposure countries.

Empirical results

Table 1–3 present the main results. Table 1, which is the baseline model, presents the results on IMF conditions per quarter with controls, which are added stepwise. Table 2–3 reports results of the same correcting for endogeneity concerns. Before examining the regression results, a simple back of the envelope calculations provides a first descriptive look at the impact of IMF conditions. Countries that have participated in IMF programs with more than ten conditions attached per quarter do witness 0.80 points lead on the investor perception index (coded on 0–12 scale) over countries that do not participate in IMF programs. Likewise, those with performance criteria and prior action conditions have an advantage of 0.60 and 0.26-points respective leads on the investor perception index.Footnote 43 It is noteworthy that these leads are not small as the investor perception index changes slowly over time. Further to this, figure 2 presents a simple bivariate scatter plot on the role of IMF conditions and investor perception index, wherein the IMF conditions are disaggregated into three groups, namely, those with high exposure to IMF conditions, moderately exposed, and those with low exposure.Footnote 44 As seen among countries which are in IMF program, those with high conditions have some positive association. But the relation appears to be negative for those in the moderate category and strongly negative for those with low exposure to IMF conditions. These simple, stylized facts show that countries with IMF conditions attached do see an advantage in terms of an improvement in investor sentiment. These simple bivariate statistics, however, may lead to spurious conclusions without controls, such as income, or the lack of democracy, or economic crises, that could explain the differences rather than IMF conditions. I, thus, examine the statistical relationship in greater detail and precision in multivariate models.

Figure 2: Correlation between IMF conditions & Investor Profile index in low, medium & high conditionality countries

Table 1: IMF conditions and investor perception during 1992–2013 – OLS estimates

Notes: Country fixed effects and year dummies are included and clustered standard errors in parenthesis. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1

Table 2: IMF conditions and investor perception during 1992–2013 – IV estimates

Notes: Country fixed effects and year dummies are included and clustered standard errors in parenthesis. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1

Table 3: First-stage regression results from the IV estimates

Notes: Country fixed effects and year dummies are included and clustered standard errors in parenthesis. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1. PC denotes Performance Criteria, SB is Structural Benchmark

Table 1 reports the impact of IMF conditions attached on investor perception index, controlling for a country's participation in an IMF program. As seen in column 1, we find the impact of participating in an IMF program to be statistically insignificant. In column 2, we add prior action conditions per quarter and find the results to be statistically insignificant. One plausible explanation is the conscious attempt by the IMF to move away from the prior actions, which were identified as harsh conditionalities, towards other forms of conditions including performance criteria and structural benchmarks. For instance, a new set of guidelines adopted by the IMF, in 2002, called “the Guidelines on Conditionality,” recommended the limited use of prior action conditions.Footnote 45 Furthermore, the recommendations included setting up a notional cap and reducing the existing level of prior action conditions to exactly half in the years to come. The new set of suggestions made by the IMF's internal evaluation in 2007 and 2013 suggests moving away from prior actions to more review-based assessments, which are undertaken more frequently, that includes (a) assessments against the conditionality itself and (b) a broader analysis of the overall performance of the economy.Footnote 46 In fact, during 1992–2013, the average prior action conditions were down from ten in the early 2000 to about six as in 2013. I suspect that this shift in focus away from prior action conditions might be one of the explanations for the reported insignificant effects, or the results could be biased because of the endogeneity problem. Next, in column 3, we include performance criteria conditions, which are positive on long-term investor perception and are significantly different from zero at the 10 percent level. The substantive effects suggest that a standard deviation increase in performance criteria conditions per quarter yields an increase of 0.13 points in the investor perception index. However, increasing the performance criteria conditions per quarter by the maximum value would increase the investor perception index by almost 1.26 points, which is 51 percent of the standard deviation of the investor perception index. Notice that these are unconditional effects. But these results remain robust when controlling for additional control variables in column 7. Finally, column 4 captures the results of structural benchmark conditions. As expected, there is no significant effect of these conditions on investor perception. In both columns 4 and 8, the structural benchmarks are significantly not different from zero. As discussed earlier, the IMF is flexible on the implementation of structural benchmark conditions mainly because they are tough to quantify and, hence, difficult to monitor.

Next, I employ my preferred identification strategy in the models presented in table 2. As discussed in the previous section, I correct for endogeneity of IMF program participation and types of conditionalities using an instrumental variable approach in which I use instruments that are interactive in nature. The probability of IMF program participation in the past interacted with the liquidity ratio of the IMF and the probability of types of conditions applied in the past interacted with the number of countries under an IMF program (log). Column 1 reports results from the model estimating the impact of IMF program participation on investor perception and in column 2–4, I plug in step-wise all three types of conditionalities. As seen from column 1, after correcting for endogeneity concerns, I now find a strong negative effect of IMF program participation on the investor perception index, which is significantly different from zero at the 1 percent level. In fact, these negative results on IMF program participation are more in line with the existing literature on IMF programs and FDI.Footnote 47 However, as seen from column 2, prior action conditions per quarter, after correcting for endogeneity, is now positively associated with the investor perception index, a result that is statistically significant at the 5 percent level. At the mean value of prior action conditions per quarter (2.35 conditions per quarter) there is roughly a 0.35 point increase in the investor perception index, but a standard deviation increase in prior action conditions per quarter results in an increase of 1.07 points. Notice that these results are net of income, democracy, economic crises, and other controls, which are controlled in the model. Similarly, we also find a positive significant effect of performance criteria conditions in column 3. One standard deviation increases in performance criteria conditions per quarter increase in the investor perception index by roughly 1.42 points. These results are in stark contrast to those who argue that participating in IMF conditional programs dents investor sentiment. These results lend firm support to my hypotheses that types of conditions do matter. Prior actions and performance criteria conditions bind the recipient countries to undertake economic policy reforms in order to receive further successive installments from the IMF. This binding obligation associated with both these conditions adds further credibility to the governments’ commitment towards policy reforms, thereby improving investor confidence. Notice that the structural benchmark conditions, such as in table 1, remain statistically insignificant even after correcting for the endogeneity problem (column 4).

With respect to the results on control variables in table 2, we find that the level of economic development (proxied by per capita GDP) is the prime determinant of investor perception, which remains statistically significant at the 1 percent level. As discussed earlier, macroeconomic and financial crises have a strong negative effect on investor perception. Notice that democracy is significantly different from zero at the conventional levels of statistical significance in column 2–4. Moving away from a strict autocracy to a full democracy increases the investor perception index by 0.69 points. Notice that the results on control variables remain largely the same in table 1–2.

Overall, three key findings can be reported from the IV results shown in table 2, column 1–3. First, once corrected for endogeneity concerns, prior action conditions become statistically significant while the substantial effect of the performance criteria has increased multifold compared to the corresponding OLS estimations reported in table 1. Second, we find a divergent result for IMF program participation in comparison to conditionalities, particularly prior actions and performance criteria. As suggested earlier, it could be due to neglecting the role of conditionality, which is an important element of IMF lending. For investors, a government's credibility is significantly enhanced when it accepts tough conditions under the prior actions and performance criteria categories. It signals commitment to economic reforms to restore macroeconomic stability, knowing fully well that accepting such conditions involve a huge ex ante and ex post political cost. Third, the bottom of table 2 lists additional statistics that speak to the strength of the instrument. The joint F-statistic from the first stage rejects the null that the instruments selected are not relevant instruments (see column 2–4). In fact, the models produce a higher joint F-statistic of 199, 221, and 185, respectively, which remains significantly different from zero at the 1 percent level.

The results from IV estimations reported in table 2 hinge on the assumption that the identification strategy applied is fully valid. In order to examine the validity of my identification strategy, I first present the first-stage regression results from predicting the IMF program participation in table 3, column 1 and the types of IMF conditionalities in table 3, column 2–4. As seen in column 1, we find a positive effect of the instrument on IMF program participation suggesting that more countries are likely to participate in an IMF program when then IMF's liquidity is high. The positive effect also means that countries with a high track record of past participation in the IMF's program are more likely to borrow when its budget is free from liquidity constraints. The interactive effect is best assessed with a margins plot, which depicts the magnitude of the interaction effect from the model in the first panel in figure 3. To calculate the marginal effect of IMF program probability, we consider the conditioning variable (IMF liquidity ratio) and display graphically the total marginal effect conditional on the liquidity ratio of the IMF. The y-axis of first panel in figure 3 displays the marginal effect of IMF program probability, and the marginal effect is evaluated on the IMF liquidity ratio variable on the x-axis. We include the 90 percent confidence interval. As seen, and in line with our theoretical expectations, the IMF program probability in the past increases the chances of participating in an IMF program (at the 90 percent confidence level, at least) when the IMF liquidity ratio is more than 17 percent. These results are on expected lines and are supported by previous studies.Footnote 48

Figure 3: Vizualized Effect of the Instrumental Variable (IV)

With respect to the control variables on selection into IMF programs, we find that poor countries are more likely to participate in IMF programs. However, democratic countries, as opposed to autocratic countries, are more likely to participate in IMF programs, a result which remains statistically insignificant. New democracies also are more likely to participate in IMF program, which is significantly different from zero at the 1 percent level. The results also show that countries with macroeconomic crises are more likely to join IMF programs. For instance, a country with debt, banking, or currency crises, is 18 percent more likely to participate in IMF programs, which is significantly different from zero at the 1 percent level. These results are in line with the findings documented by Dreher et al. (Reference Dreher, Sturm and Vreeland2009) and Vreeland (Reference Vreeland2003, Reference Vreeland2007). Interestingly, inflation has no significant effect on IMF program participation. In line with previous findings of Dreher et al. (Reference Dreher, Sturm and Vreeland2015), Dreher et al. (Reference Dreher, Sturm and Vreeland2009), and Vreeland (Reference Vreeland2003, Reference Vreeland2007), I find the UNGA voting alignment index to be positive and significant in explaining a country's decision to join IMF programs. A standard deviation above the mean value of the UNGA voting index increases the chances of participating in IMF programs by 10 percent, which is statistically significant at the 1 percent level. Finally, countries dependent on natural resource rents are less likely to participate in IMF programs. A standard deviation increase in rents as a share of GDP is associated with those 5 percent less likely to participate in an IMF program, which is significantly different from zero at the 1 percent level. Lastly, there is also evidence for recidivism, wherein an additional year spent under previous IMF programs increases the likelihood of re-entering an IFM program by 5 percent, while spending forty-two years in a previous IMF lending program (the maximum value in the sample) would increase the chances of re-entering an IMF program by 12 percent.

The first-stage results on the instruments of the types of IMF conditions are presented in table 3. Note that we include all the control variables from the outcome equation, along with the instruments. As seen from all of table 3, the results demonstrate the relevance of the selected instruments. They show a negative correlation between the instruments and the respective types of IMF conditions measured in quarters, which is highly significant. For instance, as seen in table 3, the negative effect of the instruments suggest less prior actions and performance criteria conditions when more countries participate in an IMF program. This also means that countries that have spent more conditions on prior actions and performance criteria in the IMF's program in the past are less likely to obtain a larger number of conditions. Once again, I rely on conditional plot to interpret these results. The y-axis of the second panel in figure 3 displays the marginal effect of prior action conditions probability; the third and fourth panels show the marginal effects of performance criteria and structural benchmark probabilities. The marginal effects are evaluated on the number of countries under IMF programs on the x-axis. As before, the 90 percent confidence interval is included. As seen, the probabilities of all three types of conditions in the past increase the number of conditions (at the 90 percent confidence level, at least) when the number of countries participating in IMF programs is high. Note that these results remain statistically insignificant for structural benchmark conditions. These results are on expected lines and are supported by previous studies in the literature, which largely suggest that the IMF attaches more conditions when demand for the programs from countries increases.Footnote 49 To sum up, these results show that the IMF is not only generous in funding more countries when liquidity is high (results from column 1), but also imposes more conditions when demand for loans is high to ensure loan repayment. Note that the F-statistic of the first-stage analysis statistic rejects the null hypothesis that these equations in table 2 are under identified at the 1 percent level. The instruments are also jointly relevant in table 3, with the F-statistic ranging between 185 to 221, which is significantly different from zero at the 1 percent level.

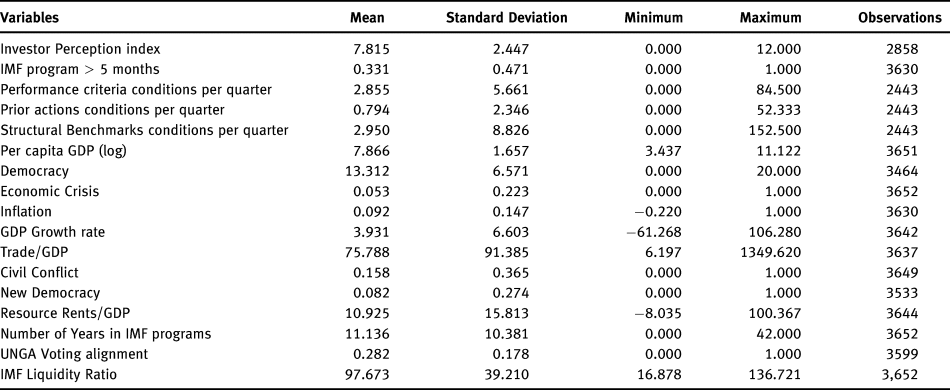

With respect to the excludability of these instrumental variables, I examine the parallel trends in the investor perception index in high and low exposure states vis-à-vis the exogeneous variation in the IMF's liquidity ratio during our study period in figure 4. Though some similarity is resembled in both the graphics, there is no clear-cut trend similarity between liquidity ratio and investor perception index in high exposure states. Similarly, figure 5 examines the presence of parallel trends in the investor perception index in high and low exposure states vis-à-vis the exogeneous variation in the number of countries under IMF programs. The top left-hand panel in figure 5 shows the temporal evolution of number of countries under IMF program (log) and the top right-hand panel captures the investor perception index across high and exposure states of prior action conditions. Likewise, in the third (bottom left-hand) and fourth (bottom right-hand) panels presents investor perception index across high and exposure states of performance criteria and structural benchmark conditions, respectively. As seen, there is no trend similarity whatsoever between countries under IMF programs (log) and investor perception index in high and low exposure states. In sum, the instrumental variable is plausibly excludable to investor perception index in specific countries proves to be highly relevant in this instance.

Figure 4: Parallel trends in Investor Profile index in High & Low exposure countries & IMF Liquidity Ratio

Figure 5: Parallel trends in Investor Profile index in High & Low exposure groups & Countries With IMF programs

Checks on robustness

I examine the robustness of the main findings in the following ways. First, I estimate the baseline specifications of MLE over three simultaneous equations reported in table 2 by dropping all the control variables. The results on IMF conditions’ effect on the investor perception index remains robust to excluding all the control variables from the model. Second, I relax the assumption of non-linearity in the IMF program participation equation and estimate a 3SLS with the setup being like that of MLE. The new results based on the 3SLS estimator remain robust. The instrumented effect prior actions and performance criteria conditions on investor perception index remain positive and significantly different from the 1 percent level. Third, I use Heckman regression estimator,Footnote 50 which takes account of the determinants of a country's decision to enter into an IMF program, the non-random treatment assignment, and models it in non-linear specification. The linear estimation of investor perception is estimated after the non-linear prediction equation, as the IMF program weeds out the countries, which are not part of its lending programs. The Heckman estimator explicitly models selection on a theory-based exclusion restriction variable, i.e., an exogenous instrument, discussed in section 2, that influences a country's participation in an IMF program but does not influence the dependent variable—investor confidence—in the second step. The positive effect results of IMF conditions (prior actions and performance criteria) on investor perception index remain robust. Fourth, I exclude the observations with extreme values in the variables on IMF conditions. For instance, in the variable total IMF conditions per quarter, while the mean value is about 6.6 conditions per quarter, the maximum value is about 152.5 conditions per quarter. I identify such extreme values and exclude them from the sample. The baseline results without outliers are qualitatively unchanged, suggesting that the results are not driven by extreme values. Fifth, following Dreher et al. (Reference Dreher, Sturm and Vreeland2015), I replace IMF conditions measured in quarters with count of IMF conditions. As discussed earlier, the data on conditions provided by the MONA dataset is a cumulative number of conditions and types of conditions in force. Estimating the models with a count of cumulative number of conditions does not change the results in terms of the sign of the coefficient and the statistical significance. Finally, I also estimate the models using ordered probit with time-fixed effects and heteroscedasticity consistent robust standard errors by converting the dependent variable of investor protection index into an ordinal structure of 1 to 12 by reconfiguration and rounding off the values to the nearest point. However, in ordered probit models, I do not control for country-specific fixed effects due to the incidental parameter problem (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2002). Estimating the results with ordered probit time fixed effects do not change the original results drastically. The robustness check results, not shown here due to brevity, are available upon request. In summary, the results taken together seem robust to using alternative data, specification, and testing procedure.

Conclusion

The theoretical and empirical literature on how IMF program participation impacts investor sentiment remains contentious. In this paper, I argue that the reason for the divergent results is due to neglecting the role of the conditionality imposed by the IMF. Merely participating in an IMF program may not revive international investor sentiment. Rather, investor sentiment improves as governments enhance the credibility of their commitment to key economic policy reforms by accepting various conditions attached to the IMF arrangement, reneging on such agreements incur ex ante and ex post political costs. I empirically test these arguments by relying on the IMF conditions data released by the MONA database. Furthermore, I disaggregate the data on conditionalities by the type of policy conditions and number of quarters in a year a country has been under the arrangement of specific conditions. Using panel data on 166 countries during the 1992–2013 period (twenty-two years), my findings show that long-term foreign investor sentiment resurrects when countries participate in IMF programs with prior actions and performance criteria conditions attached. These results survive a range of robustness checks including alternative data and testing, methods such as applying 3SLS and Henchman selection models.

These results highlight two key policy implications. First, these findings are in stark contrast to those who argue that IMF conditional programs are akin to swallowing a bitter pill. If it is not reforms that matter, then it might be that the IMF, who is the “doctor,” is being blamed for death of the patient, particularly when the patient refuses to take the medicine. In fact, my results demonstrate that the so-called bitter medicine may act as a palliative. Second, previous research has documented that investors do react to economic policy reforms. If so, crises-ridden, cash-strapped developing countries, often dependent on long-term capital inflows to finance their balance of payments books of accounts, could significantly benefit from policy reforms by complying with the IMF conditions. By complying with the conditions, the governments can signal credibly their willingness to undertake reforms and thereby set the tone for higher economic development trajectory.

Appendix

Appendix 1: Countries under study

Appendix 2: Descriptive statistics

Appendix 3: Data definition and sources