I. Introduction

As corporations have faced mounting criticism from activists, local communities and academics for the effects that their operations have had on human rights in various locales, scholarship in the area of business and human rights (BHR) has gained significant traction.Footnote 1 Broadly speaking, BHR scholarship examines the responsibility of corporations for abuses caused directly by corporations and their subsidiaries as well as for various forms of complicity in human rights abuses along their value chains.Footnote 2

The genesis of BHR scholarship was largely in legal studies and BHR continues to be a heavily discussed topic among legal scholars.Footnote 3 The main concern of legal scholars has been to assess whether or to what extent corporate human rights responsibilities can be derived from or established through international law; in short, to justify the nature and content of human rights responsibilities as applied to corporations. While some have focused on reinterpretations of existing international law,Footnote 4 others have engaged in the theorization of new regimes to hold companies legally responsible for their human rights impacts.Footnote 5 Currently, there is a revived discussion among legal scholars on the role of the state in holding corporations legally responsible for human rights abusesFootnote 6 such as through extraterritoriality or other means of international regulation.Footnote 7 The strength of BHR scholarship lies in the justification and elaboration of corporate human rights responsibilities from a legal and philosophical perspective. However, there appears to date to be only a thin discussion of how to move from legal and philosophical responsibilities to the fulfilment of these responsibilities via organizational implementation.Footnote 8

BHR scholarship has been expanding to other disciplines such as accounting,Footnote 9 economics,Footnote 10 international business,Footnote 11 and management. Within management, it is particularly social issues in management (SIM) scholars who engage in BHR scholarship.Footnote 12 BHR scholarship within SIM could be interesting for the advancement of BHR scholarship overall because SIM scholars focus on the elaboration, examination and impact of social and ethical issues on organizations and their management. Footnote 13 SIM scholars also address the broad topic of implementing responses to social and ethical issues, using constructs such as corporate social performance.Footnote 14 SIM scholars further seek to explicate the origin, nature and content of corporate responsibilities, as does BHR. Their starting point often is a concept of the corporation not merely as a legal structure, but as a social or even political institution.Footnote 15 As such, they tend to interpret human rights responsibilities more expansively than legal scholars, with some of them arguing for broad positive responsibilities beyond a negative responsibility to respect human rights.Footnote 16 This, in turn, also requires systematic engagement with the moral limits of such responsibilities.Footnote 17 Such intellectual contributions typically approach the issue through the lens not of legal responsibilities, but rather through the delineation of rights and associated moral responsibilities of corporations.

The purpose of our article is to conduct a systematic review of BHR scholarship within SIM scholarship with three objectives: (1) to introduce non-SIM BHR scholars to useful SIM concepts to strengthen and complement their own research, (2) to expand SIM scholars’ understanding and knowledge about emerging BHR issues to advance their own research agendas, and as a consequence (3) to evaluate the potential of BHR to develop into a subfield of study within SIM. BHR, as we show in this article, has made significant progress in both the legal and SIM literature. However, there are also pressing questions that we seek to address related to the ways in which BHR is implemented and the outcomes of BHR-related actions by corporations.

Our study complements existing recent reviews on BHR scholarshipFootnote 18 in two ways. First, our review is broader in that we include the broad literature in SIM compared with BrenkertFootnote 19 who focused on the contributions of business ethicists to BHR scholarship and hence focused on the ‘normative ethics of business’. Similarly, the reviews of ArnoldFootnote 20 and WerhaneFootnote 21 are narrow in that they focus on particular topics within BHR – justification for corporate human rights obligations and the moral status of corporations, respectively. Santoro and WettsteinFootnote 22 provide a review of BHR scholarship by limiting their review to the most influential books and academic articles. These reviews are important contributions to the BHR literature, and their focus allowed each to undertake thorough analyses of their respective research question. Second, our review differs from existing reviews in that we conducted a systematic literature review and applied a sequence of methodological steps (as explained in the next section) while the existing reviews were more selective in their literature review and did not discuss their methodology explicitly.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section provides an overview of the review methods. This is followed by an overview of existing BHR scholarship in SIM studies. Following the literature review, Part IV presents a research agenda. Finally, we outline the development of BHR as a subfield of study within SIM before a conclusion is drawn.

II. Review Methods and Scope

We have focused our literature review on BHR research within SIM. SIM scholarship examines the ‘relationship between business and society at various levels of analysis’ including the actions of managers, business firms and the market.Footnote 23 Given the different levels of analysis and its wide spectrum, SIM is a highly interdisciplinary research field with scholars from backgrounds in legal studies, accounting, strategy, marketing, sociology and philosophy, to name just a few.Footnote 24 Given the disciplinary diversity of SIM scholars and the relatively broadly defined scope of SIM (and this broad scope is on purpose),Footnote 25 it comes as no surprise that SIM scholarship goes by a number of names such as ‘business and society’, ‘environment, social and government (ESG)’, ‘business ethics’, ‘corporate social performance’ and ‘corporate social responsibility’ (CSR).Footnote 26 Thus, SIM scholarship is boundary- and level-spanning.Footnote 27 SIM research not only encompasses work on specifying the nature and content of corporate responsibility, it also addresses topics such as the ways in which corporations decide how to respond to pressures for responsible behaviour and to social issues, as well as measurement of outcomes of corporate actions related to social issue responses.Footnote 28

Recently, Wood and Logsdon stressed that SIM scholarship is ever-evolving, with a primary mission ‘to continually point the way toward the next big set of issues, problems, experiments, and solutions in business-society relationships.’Footnote 29 BHR certainly is one such ‘next issue’, and given its mission, we believe it is valuable to review how SIM has taken it on. In our article, we refer to SIM scholarship as described broadly in the paragraph above, but we acknowledge that there are important nuances and distinctions within SIM scholarship. In a similar vein, corporate social performance ‘is a set of descriptive categorizations of business activity, focusing on the impacts and outcomes for society, stakeholders and the firm itself.’Footnote 30 Thus, it is broader than some other concepts within SIM as it has three major components (CSR principles, processes and outcomes). While we respect the diversity of SIM scholarship, we refer here to SIM scholarship as an umbrella term capturing the issues at the intersection of business and society, and regard focused research on CSR, corporate social performance and business ethics as ‘areas of inquiry’ within SIM, as recently summarized in Epstein.Footnote 31

The processes and procedures used in this literature review are similar to those applied in other reviews.Footnote 32 The literature review involved several systematic steps. First, we focused on the top five academic journals for SIM scholarship (Business and Human Rights Journal, Business & Society, Business Ethics Quarterly, Business Ethics: A European Review and Journal of Business Ethics). We acknowledge the publication of numerous influential books on BHR. However, we focused our literature review on the scholarly conversation within peer-reviewed journals that publish SIM research. Second, we accessed the journals through commonly used databases (such as EBSCOhost, Business Premier and JSTOR) or directly through their websites, and searched for BHR-related terms (such as human rights, complicity, or United Nations) in titles, abstracts, subject terms or keywords. In addition, each journal issue in which one or more articles appeared was analysed in parallel to ensure that no relevant article was missed. Finally, each article was read by the two authors independently to determine whether it dealt with a BHR-related topic. The authors compared their results and discussed any differences before agreeing on the classifications for each article.

In our review, we focused on articles that address human rights in the business context. BHR scholarship is diverse in breadth and depth. This breadth and depth is mirrored in the variety of articles that is included in our review. BHR scholarship ranges from broad foundational arguments on the role of business in human rightsFootnote 33 to specific human rights issues in the context of business, such as labour standards,Footnote 34 sweatshopsFootnote 35 and poverty.Footnote 36 Likewise, BHR scholarship includes focused studies on particular industries such as the extractive industry,Footnote 37 electronicsFootnote 38 and media.Footnote 39

The review included articles published between January 1990 and August 2017. Several publications have called the mid-1990s the formal beginning of a more focused and systematic discussion on BHR.Footnote 40 As recently summarized by Wettstein and colleagues, ‘a systematic debate on BHR started to emerge only during the mid-1990s’, which was triggered by the complicity of oil companies in human rights abuses in Nigeria and the rising media and attention from non-governmental organizations towards sweatshop conditions and child labour in global value chains.Footnote 41 Prior to the mid-1990s, academic attention to BHR was rather ‘sporadic and fragmented’Footnote 42 with isolated publications in the 1970s and 1980s.Footnote 43 Donaldson’s seminal work Ethics of International Business Footnote 44 can be regarded as one of the first milestones in BHR and has set human rights as a foundational element for corporate conduct. BHR scholarship intensified in the mid-1990s.Footnote 45 Even though the mid-1990s are regarded as the starting point of a more systematic discussion on BHR, we started our literature review in 1990 to avoid missing any scholarship that could potentially be relevant to our analysis. Articles that were published online until August 2017, but had not yet been published in print, were included in the review because this work indicates themes to be found in forthcoming scholarship. In total, 180 articles were included in the analysis.

In reviewing the articles, content analysis was used.Footnote 46 Content analysis allows the researcher to reduce textual data into codes that capture the most relevant elements/themes of the article. We used content analysis mainly qualitatively to identify themes and topics of the reviewed articles. For the coding, we used a codebook that was inductively derived. Table 1 provides an overview of the codebook. For plausibility and reliability reasons, several rounds of coding were conducted. The two authors coded each article along the dimensions of the codebook independently of each other. The articles were divided into batches of 25 and after each author coded a batch of 25 articles, the authors compared and discussed their coding and coding differences to refine the codebook before continuing with the next batch of articles. This process allowed for a continuous refinement of the applied coding categories and followed the procedures of other literature reviews.Footnote 47 The level of coding agreement between the authorship team increased from 73 per cent for the first article batches to 92 per cent for the last article batches.

Table 1. Codebook for literature review

The articles were first coded along their research themes (see Table 1). We identified three research themes (justification, implementation and outcome). These themes highlight the discussions on (1) why corporations have human rights responsibilities, (2) how corporations manage human rights responsibilities, and (3) what results from corporate human rights management.Footnote 48

Besides identifying research themes, we were interested in the epistemological perspective of BHR research in SIM outlets because SIM encompasses many different areas of inquiry, such as business ethics, which is predominantly normative, and CSR that has been described as being more theoretical.Footnote 49 We broadly divided the articles into conceptual, empirical, normative or descriptive.Footnote 50Conceptual articles are theory-based and review the literature to develop a concept in the form of propositions, hypotheses or relations between different constructs. This type of research does not include any collection of new empirical data. Obviously, most papers use or refer to concepts. We classified an article as conceptual when the authors present a new concept or derive a new and innovative relationship among concepts to advance existing scholarship.

Similar to conceptual papers, empirical studies include propositions or hypotheses between different constructs but include an examination of new collected empirical data. Empirical studies can take various forms such as survey studies, case studies or other studies that include observation and collection of quantitative or qualitative data.

Normative articles put forward a particular position relating to what standards, values, behaviour and actions should be like. Normative research is evaluative and can rely on philosophical and non-philosophical argumentation to elaborate on behavioural standards and/or societal expectations (business ethics) or argue what the law should look like (legal scholarship).

Finally, descriptive papers do not engage in empirical work, but rather report data, describe, and evaluate a phenomenon such as multi-stakeholder initiatives. More specifically, the ‘major focus is on reporting fact or opinion [with] no intention of a theoretical or prescriptive contribution’.Footnote 51

Finally, we categorized the articles along their primary level of analysis (macro, organizational and micro). Macro level research focuses on the construction of institutions such as structures and mechanisms of social order. Articles at this level of analysis, drawing on the distinction made by Scott, examine how various actors cooperate, govern and affect each other.Footnote 52 Macro level studies are about the management of relationships between organizations and external bodies.Footnote 53

Organizational-level research uses the corporation as the unit of analysis; here scholars focus on corporate practices and policies. Studies on this level look at the organizational construct overall and ask whether corporations (not individual actors within organizations) are responsible for human rights and if so, how corporations can implement such responsibilities. Thus, we include articles in this category on the conceptualization of the role of corporations when it comes to human rights, or the examination of corporate practices or strategies with regard to human rights, for example. Finally, micro level research focuses on the individual, i.e., the manager, employee or consumer, and can address issues such as how individuals react to human rights abuses, how they make sense of them, or how they evaluate them. Table 1 summarizes the codebook and lists brief definitions of the codes.

A few words of caution are needed at this stage. First, as described above, we coded the articles along research themes, types of research and primary level of analysis. As common with such categorizations, they can suffer some ambiguity as different scholars might define the categories slightly differently. Thus, subjectivity is certainly a challenge, although one endemic to qualitative research generally. To minimize this, the two authors coded the articles independently of each other and discussed each discrepancy in coding until agreement was reached. Second, given that human rights itself is a broad construct, one could argue that almost all BHR articles have a macro perspective. In fact, the line between organizational and macro level studies is particularly thin. When categorizing the articles, we kept asking whether an article focused on the organization (corporation) and its policies, responsibilities and management practices, or whether the article focused on the construction of norms, standards and other institutions in relation to external bodies. We acknowledge that there often can be a fine line between the categories and some articles include elements of several categories. When articles included elements of more than one category, we assigned the dominant category. Finally, the type of journals included in the literature review has an effect on the type of articles published.

III. The Current State of BHR Scholarship in SIM

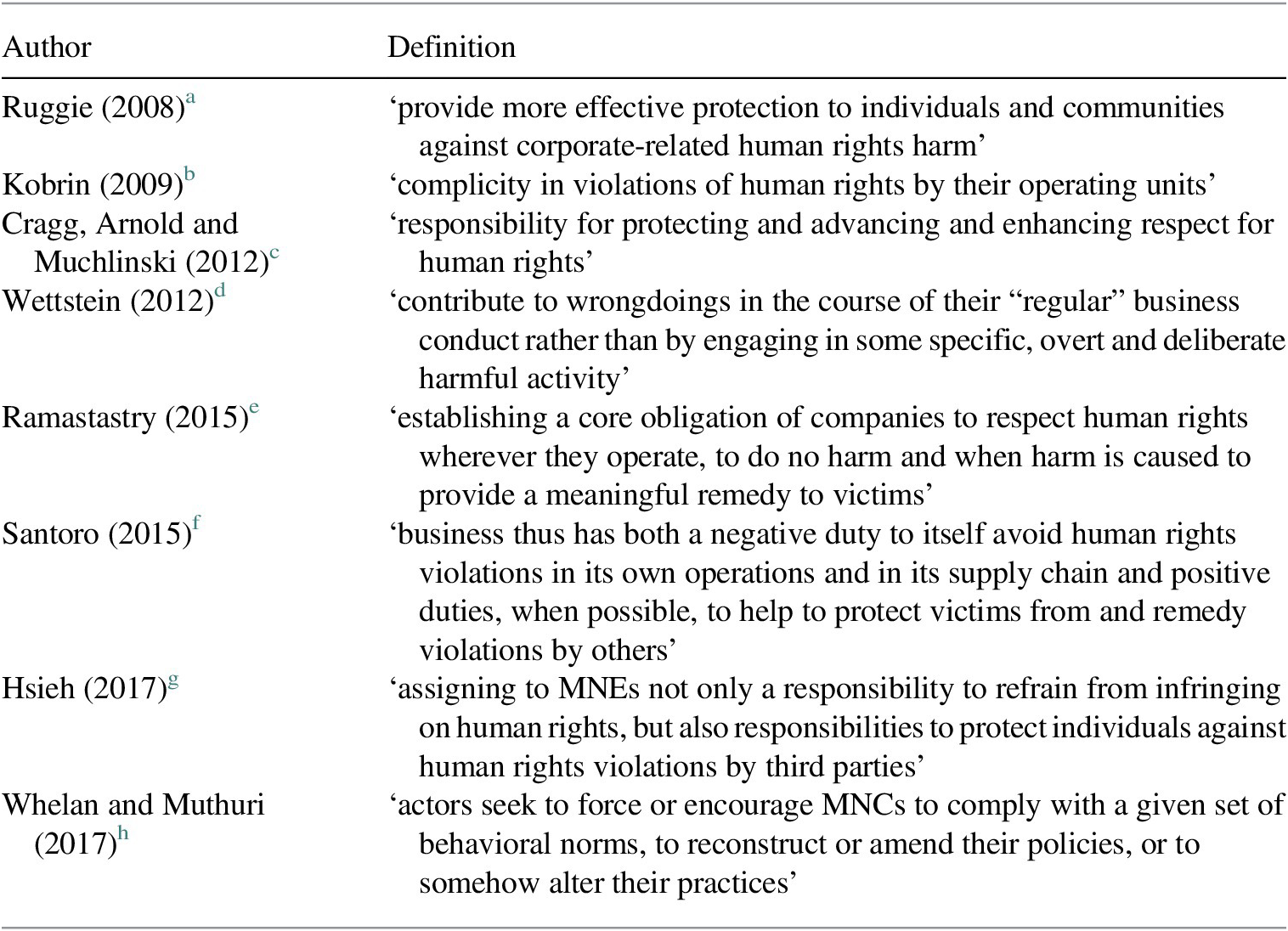

Surprisingly, not many articles provide an explicit definition or description of what is meant by BHR. Table 2 provides an excerpt of some descriptions of BHR (sorted by publication year). Some scholars describe BHR in positive terms as assigning business responsibility, duties and obligations towards human rights,Footnote 54 while other scholars use negative terms such as corporate wrongdoing, complicity and contribution to human rights abuses. Footnote 55 Similar to CSR scholarship,Footnote 56 there is a wide range of elaborations of what BHR scholarship is about. Thus, for our purposes we use BHR as an umbrella term to describe the role and responsibility of corporations for human rights.

Table 2. Business and human rights definitions

a John Ruggie, ‘Protect, Respect and Remedy: A Framework for Business and Human Rights’ (2008) 3:2 Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 189.

b Kobrin, Footnote note 55, 350.

c Wesley Cragg, Denis G Arnold and Peter Muchlinski, ‘Guest Editors’ Introduction: Human Rights and Business’ (2012) 22:1 Business Ethics Quarterly 1.

d Wettstein, Footnote note 16, 38.

e Ramasastry, Footnote note 40, 240.

f Santoro, Footnote note 2, 14.

g Hsieh, Footnote note 54, 305–306.

h Whelan and Muthuri, Footnote note 82, 741.

We divided the review time period (1990–2017) into four 7-year intervals to see how the number of BHR publications has developed over time. Graph 1 provides an overview of the development of each research theme per time interval. The number of publications in each theme has been consistently increasing. This development illustrates not only the growth of the BHR scholarship in SIM but also its healthy maturation. Of the three research themes, justification has been consistently increasing at the highest rate during each time interval.

Graph 1. BHR theme development over time

Tables 3 and 4 provide a numerical overview of the research themes, type of articles, and level of analysis. The smallest number of articles were empirical studies on BHR. Empirical studies only started appearing in 2001 but new empirical work has been regularly published since then.Footnote 57 With regard to the level of analysis, just over 50 per cent of the reviewed articles focus on the organizational level, while 45 per cent focus on the macro level. Only a very small number of reviewed articles (2.2 per cent) address the micro level of analysis (see Table 4). In the following sections, we provide a detailed discussion of each research theme.

Table 3. BHR scholarship in SIM themes and research type

Table 4. BHR scholarship in SIM themes and level of analysis

A. Justification

Scholars use legal and/or ethical argumentation to justify whether businesses have human rights responsibilities, and if so, what the nature and content of those responsibilities are. For example, scholars refer to criminal, international and human rights law and describe how these laws can or should be applied to corporations and make corporations thereby legally accountable for human rights abuses.Footnote 58 Other scholars describe cases of corporate complicity and thereby derive reasons for why corporations should have human rights responsibilities.

Besides relying on law, scholars focus on ethical argumentation for whether corporations have human rights responsibilities and apply ethical theories, such as Kantian ethics,Footnote 59 Confucian ethics,Footnote 60 and social justice.Footnote 61 Hsieh, for instance, argues for a corporate duty of assistance, and outlines some specific conditions when corporations have a duty to assist, and ‘help provide mechanisms through which those affected by their activities are able to contest corporate decisions.’Footnote 62Table 5 provides a summary of the main theoretical perspectives and argumentations that are made in this BHR theme and lists several scholarly contributions.

Table 5. Summary of BHR research on justification

a Edmund F Byrne, ‘In Lieu of a Sovereignty Shield, Multinational Corporations Should Be Responsible for the Harm They Cause’ (2013) 124:4 Journal of Business Ethics 609.

b Stepan Wood, ‘The Case for Leverage-Based Corporate Human Rights Responsibility’ (2012) 22:1 Business Ethics Quarterly 63; Campbell, Footnote note 109; Cragg, Footnote note 1.

c Cassel, Footnote note 58; Karin Buhmann, ‘Public Regulators and CSR: The “Social Licence to Operate” in Recent United Nations Instruments on Business and Human Rights and the Juridification of CSR’ (2016) 136:4 Journal of Business Ethics 699; McCorquodale, Footnote note 66.

d Florian Wettstein, ‘The Duty to Protect: Corporate Complicity, Political Responsibility, and Human Rights Advocacy’ (2010) 96:1 Journal of Business Ethics 33; Rosemarie Monge, ‘Institutionally Driven Moral Conflicts and Managerial Action: Dirty Hands or Permissible Complicity?’ (2015) 129:1 Journal of Business Ethics 161; Kobrin, Footnote note 55; Wettstein, Footnote note 16.

e Kim, Footnote note 60.

f Byrne, note a (Table 5).

g Bernaz, Footnote note 7.

h Denis G Arnold, Robert Audi and Matt Zwolinski, ‘Recent Work in Ethical Theory and Its Implications for Business Ethics’ (2010) 20:4 Business Ethics Quarterly 559; Luke, Footnote note 67; Hahn, Footnote note 36.

i Wettstein, Footnote note 12; Thomas Maak, ‘The Cosmopolitical Corporation’ (2009) 84:S3 Journal of Business Ethics 361.

j Obara, Footnote note 8.

k Cragg, Footnote note 106; Hartman et al, Footnote note 36; Bishop, Footnote note 69; George G Brenkert, ‘ISCT, Hypernorms, and Business: A Reinterpretation’ (2009) 88:S4 Journal of Business Ethics 645.

Graph 1 shows that the justification theme is the strongest research theme in BHR and has not only been continuously growing but rising at a steeper rate than the other two research themes. The continuous discussion on justification has less to do with a dispute about whether business has human rights responsibilities, but rather with a fine-tuning of the foundations why corporations should have human rights responsibilities in light of new developments in the legal realm or of soft-law initiatives. Besides, we see a rise in justifying corporate human rights responsibilities for specific industries or issues.Footnote 63 We believe that it is relatively easier to make justification the basis of a paper in SIM due to the existence of a well-established normative conversation in the literature. Implementation-related scholarship, however, is harder to write about because it requires that we go into the black box of the organization, and outcome-related scholarship requires time, resources and data.

In conclusion, research on the justification of corporate human rights obligations can best be described as being of normative nature applying philosophical and non-philosophical argumentation for or against corporate human rights obligations. Most research in this research stream focuses on the organizational and macro levels discussing the role of companies and other stakeholders in defining corporate human rights obligations, and less so on the role of the individual, such as employees or managers.

B. Implementation

Operating under the assumption that corporations have human rights responsibilities, numerous BHR scholars have examined how to implement human rights policies and processes. More than a third of reviewed articles focus on this theme. Two-thirds of the articles in the implementation theme focus on the organizational level while the other third address the macro level (Table 4). At the macro level, BHR scholars highlight how corporate human rights responsibilities can be implemented through multi-stakeholder and soft-law initiatives such as the UN Global Compact, which encourages corporations worldwide to adopt sustainable and socially responsible policies, and report on their implementation. BHR scholars describe the achievements and limitations of such private regulation initiatives.Footnote 64

The majority of work in this theme describes the human rights management processes or proposes additional processes to manage human rights at the organizational level. The most common forms of implementing human rights management include codes of conduct that outline corporate human rights obligations,Footnote 65 due diligence mechanisms,Footnote 66 and stakeholder management tools.Footnote 67Table 6 provides an overview of the implementation methods and a brief summary of some representative studies.

Table 6. Summary of BHR research on implementation

a Cynthia Stohl, Michael Stohl and Lucy Popova, ‘A New Generation of Corporate Codes of Ethics’ (2009) 90:4 Journal of Business Ethics 607; S Prakash Sethi et al, Footnote note 71; André Sobczak, ‘Codes of Conduct in Subcontracting Networks: A Labour Law Perspective’ (2003) 44:2–3 Journal of Business Ethics 225.

b Rasche and Gilbert, Footnote note 64; Eweje, Footnote note 34; Gerald F Cavanagh, ‘Global Business Ethics: Regulation, Code, or Self-Restraint’ (2004) 14:4 Business Ethics Quarterly 625.

c Deanna Kemp et al, ‘Just Relations and Company–Community Conflict in Mining’ (2011) 101:1 Journal of Business Ethics 93.

d Rajib N Sanyal, ‘The Social Clause in Trade Treaties: Implications for International Firms’ (2001) 29:4 Journal of Business Ethics 379. Rice, Footnote note 67.

e Peter Muchlinski, ‘Implementing the New UN Corporate Human Rights Framework: Implications for Corporate Law, Governance, and Regulation’ (2012) 22:1 Business Ethics Quarterly 145; Matthew Murphy and Jordi Vives, ‘Perceptions of Justice and the Human Rights Protect, Respect, and Remedy Framework’ (2013) 116:4 Journal of Business Ethics 781; Fasterling, Footnote note 66.

C. Outcome

We found only a small selection of articles that discuss the outcomes of corporate human rights abuses and policies. Sixteen per cent of the reviewed articles address the effects or implications of corporate human rights responsibilities. Table 7 provides an overview of the outcomes that were addressed in this research theme. Broadly speaking, scholars examined the effects of corporate human rights abuses or policies on the bottom line,Footnote 68 improved corporate behaviour,Footnote 69 individual motivation,Footnote 70 and trust.Footnote 71 Two-thirds of the articles in this research theme focused on the macro level (Table 4). Janney, for example, discusses how the market reacts when firms join the UN Global Compact.Footnote 72 Several articles examined outcomes on the organizational level such as company responses to human rights reportsFootnote 73 or the effect of intra-organizational pressure to conform to human rights expectations.Footnote 74 Only two articles discussed effects of human rights management at the micro level: for example, Puncheva-Michelotti and colleaguesFootnote 75 looked at how an employee’s understanding of human rights affects their decision making.

Table 7. Summary of BHR research on outcome

a Blanton and Blanton, Footnote note 48; Jay J Janney, Greg Dess and Victor Forlani, ‘Glass Houses? Market Reactions to Firms Joining the UN Global Compact’ (2009) 90:3 Journal of Business Ethics 407.

b Behrman, Footnote note 69.

c Puncheva-Michelotti et al, Footnote note 70.

d Julia Wolf, ‘The Relationship between Sustainable Supply Chain Management, Stakeholder Pressure and Corporate Sustainability Performance’ (2014) 119:3 Journal of Business Ethics 317; Jinhua Cui, Hoje Jo and Manuel G Velasquez, ‘Community Religion, Employees, and the Social License to Operate’ (2016) 136:4 Journal of Business Ethics 775.

Table 8. Future business and human rights research: theoretical perspectives, questions and methods

Outcome is the smallest research theme within BHR. However, it is one that could become critical in assessing the results of BHR management across different levels of analysis based on attributions of ethical obligations to businesses. If firms have human rights obligations and if they manage their human rights responsibilities, what concrete effects on human beings emerge as a result? What are the effects of managing human rights on the individual level for employees and for victims (do victims receive remedies?), on the organizational level (how do human rights management tools relate to corporate performance?), and on the macro level (what are the effects of corporate human rights management efforts on the number of human rights abuses?). These are just a few pressing questions that need attention in future research, as we discuss in the following section.

IV. Business and Human Rights Research Agenda

Our literature review revealed that BHR is an evolving field within SIM with rising numbers of publications and three major research themes. SIM journals have certainly been open to BHR scholarship, but there is more that could be done. In the following, we present a conceptual framework for future BHR research (see Figure 1). This conceptual framework can usefully guide scholars – both SIM and non-SIM BHR scholars – in identifying potential research gaps and embedding their research in related focus areas. The framework consists of two dimensions. On the horizontal axis, we highlight the level of analysis capturing the micro, organizational and macro levels. While we will emphasize the need for more research on the micro level, we will also highlight potential future research directions on the organizational and macro levels. On the vertical axis, we highlight the two research themes – implementation and outcome – that we believe need more consideration in future BHR research. We selected these dimensions based on our literature review and categorization of existing research. Thus, we see future BHR research clustering around raising awareness and triggering actions among employees, examining the management of BHR processes and impact on the firm and society as a whole, and on investigating collaborations with other stakeholders.

Figure 1. Themes in the integration of BHR and SIM scholarship

Here we note the ways in which SIM scholarship and BHR scholarship can benefit from each other. Early BHR scholarship emerged out of analyses of international law, focusing on specifying the nature and content of human rights obligations faced by businesses. As such, this BHR research focused on the theme of justification and largely at the macro level of analysis. BHR scholarship within the field of SIM picked up the theme of justification, primarily but not exclusively from a philosophical perspective. Both fields address normative concerns from different perspectives: philosophical (SIM) and legal (BHR). Although there is a paucity of micro level SIM scholarship in BHR, business school scholars do have particular expertise in understanding the individual- and organizational-level processes that affect implementation of business’ human rights obligations. Drawing on ideas from organizational theory, SIM scholarship has also added conceptual work to BHR. More generally, SIM researchers have particular expertise in the study of implementation and outcomes, such as scholars that examine corporate social performance.Footnote 76 SIM scholars can take ideas related to implementation, help make them practicable by using tools from organizational theory, and then assess the outcomes of business actions related to BHR. In this respect, legal scholarship is complementary with SIM scholarship. Legal scholarship in BHR would benefit from a better understanding of organizational implementation and the assessment of outcomes associated with it, while SIM scholars would benefit from a more fulsome understanding of the provenance of human rights obligations faced by businesses. The framework we have outlined in Figure 1 is useful for understanding the path that research on such issues might take.

A. Future Research at the Macro Level

At the macro level – that is, outside of the organizational context – there are important questions that have received inadequate scholarly attention to date. BHR actor collaboration refers to the processes by which interested actors seek to influence the behaviour of organizations with regard to human rights. Here it would be interesting to examine questions such as the following: what type of soft-law initiatives are most successful in terms of including participating firms with low human rights abuses? What legitimacy mechanisms of soft-law initiatives exist and are most effective for BHR?Footnote 77 Why have some corporate human rights abuses received more attention (activist support) than others? Social movement theory can be helpful here because it provides insights into why and how activists and groups approach corporations.Footnote 78 Additionally, work in non-market strategyFootnote 79 is useful for BHR research in understanding how corporations might effectively respond to the expectations of non-market actors such as activists, legislators and the media (among others) in the human rights domain.

A further macro level topic that has not received attention in BHR scholarship as of yet is BHR impact on society. This addresses how the results of both actor collaboration and the behaviours of firms affect outcomes germane to human rights: what are the impacts of actions by various external actors and organizations in the human rights domain? The most obvious impact is of course the reduction of human rights abuses. Such research could answer essential questions such as these: what is the most effective approach to reduce human rights abuses by corporations – social activism, litigation, regulation or corporate policies? To what extent are these approaches complementary? A key challenge in BHR is access to remedy. Thus, one of the most important outcomes for society is for the victims to receive remedy. The BHR scholarship in SIM has been surprisingly silent in this regard – most likely because it is hard to get access to data. However, data become more and more available through databases such as the Corporations and Human Rights Database, Asset4 and Sustainalytics, which will strengthen research in this direction.

BHR research at the macro level focused on the collaboration with other actors is at the intersection of BHR and corporate diplomacy scholarship, which is slowly getting more traction.Footnote 80 Broadly speaking, corporate diplomacy refers to how corporations manage international issues (such as human rights) and how they engage with and collaborate with public institutions. Thus, the emphasis in this literature is mainly on firm-government collaboration, which is key for progress in macro level BHR research because most human rights abuses are conducted by state actors in the name of joint firm–state projects. Finally, insights from network theoryFootnote 81 can provide novel perspectives on how actors connected to human rights abuses collaborate to address abuses and provide remedy. An analysis of power relations within the network can help in exploring the most efficient ways of providing remedy. A network analysis could thus outline different ways how actors can collaborate or use pressure on other actors within their network to achieve their objectives such as explicit corporate assumptions of human rights responsibilities or receiving remedy.

B. Future BHR Research at the Organizational Level

At the organizational level, we see two main avenues for future research: the management of BHR and the impact of BHR on the corporation. BHR management refers to the processes that organizations use to respond to BHR issues. Such processes can include codes of conduct or other statements of ethical principles regarding human rights, introducing mechanisms to provide remedy to victims of human rights abuses, social auditing and reporting, and human rights assessment and risk management tools among many others. BHR management deals with keeping track of potential human rights infringements, measuring corporate involvement, and the like. It goes without saying that some disciplines such as accounting have already been engaged in the question of how businesses can implement their human rights responsibilities. We hope that our review helps make BHR scholarship in SIM more accessible to non-SIM scholars, such as accounting scholars, and they might find connecting factors to join existing BHR conversations in SIM.

While we have seen significant coverage on BHR management, we still want to highlight several future research questions. What management systems, mechanisms and reporting schemes would be needed to ensure business accountability for human rights abuses? What are optimal processes for managing human rights issues, and do these processes differ based on industry, location, or other factors? When reviewing the literature, we noticed that access to remedy was one of the topics that has not been significantly addressed. How can corporations provide effective remedies (including access to remedy) to victims of human rights abuses? What does remedy in cases of human rights abuses actually look like – apology, monetary compensation, rebuilding villages? The next step would be to analyse the effects on organizational-level outcomes such as profitability, legitimacy and reputation as a result of different sorts of human rights management processes (BHR impact on the firm in Figure 1).

BHR scholarship addressing BHR management and BHR impact on the firm can gain from institutional theory and organizational legitimacy. According to institutional theory, organizations adjust their behaviours according to the perceived standards or norms within society.Footnote 82 Thus, an institutional theory approach to the adoption of corporate human rights policies might shed more light onto the opportunities and challenges of managing human rights, such as identifying the institutional factors that facilitate or hamper the adoption of corporate human rights policies. Recent institutional theory contributions to logicsFootnote 83 and entrepreneurshipFootnote 84 provide further interesting avenues for future research in BHR on the organizational level. Are there different BHR logics at play when looking at different cases (such as conflict minerals, the Rana Plaza collapse, or modern slavery) that would account for the adoption of different types of corporate policies or responses? In a similar vein, which role has John Ruggie played as an institutional entrepreneur and how has he (his role) influenced corporate reactions to the UNGPs?

When it comes to the impact of BHR on the firm, another area for future research would examine the effects of corporate human rights abuses as well as of corporate human rights policies. This research area is at the intersection of BHR and organizational legitimacy. Suchman refers to legitimacy as ‘a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions.’Footnote 85 BHR scholarship has much in common with research on organizational moral legitimacy. Moral legitimacy is achieved when actors co-create values and norms in collaboration with other actors. An organizational moral legitimacy approach might help in examining how such universal corporate human rights responsibilities in terms of codes of conduct or remedy processes can be co-created.Footnote 86 Other questions at the intersection of BHR and organizational legitimacy include: what corporate human rights policies are perceived as legitimate? What is the impact of introducing human rights policies on a firm with low legitimacy versus a firm with high legitimacy? Do some firms gain more from introducing human rights policies than others?Footnote 87 Can the existence of corporate human rights policies lessen the effect of human rights abuses on corporate legitimacy?Footnote 88 What is the impact (if at all) on corporate legitimacy when corporations get connected to human rights abuses? Thus, integrating institutional theory and organizational legitimacy into BHR scholarship will help develop more robust conceptual frameworks as well as advance theory development in the BHR field.

C. Future Research at the Micro Level

Most BHR research is relatively silent when it comes to the micro level of analysis. This is a common challenge in SIM and management scholarship in general and referred to as the ‘micro-macro divide’.Footnote 89 Micro level research is important because ‘[n]onmarket strategy decisions are made by leaders whose motives, judgment, and choices may differ significantly. Therefore, research is needed on the role of heterogeneity of leaders and their interface with the nonmarket environment in driving firm performance’.Footnote 90 Leadership scholarship might be helpful for BHR as it examines managers’ intentions and choices and how these in turn influence their corporations’ decisions and strategies.

BHR awareness addresses the processes by which individuals become aware of BHR issues affecting their organizations. Such awareness can occur at the level of local country management, functional-area management, or at the senior management level. The ways in which individuals become aware of and then take action regarding BHR issues is an understudied area that has implications for how organizations in turn respond to BHR issues. At this level of analysis, organizational behaviour scholarship can enrich BHR scholarship. If the existing discussion in BHR has largely concluded that corporations have a responsibility to respect human rights, it is time to examine how managers and employees can fulfil such responsibilities as well as when they perceive the existence of them. A number of questions arise from organizational behaviour scholarship that are germane to BHR at the micro level: how do you inform, train and educate your staff, employees and managers about BHR? The role of leadership can be crucial.Footnote 91 Obara’sFootnote 92 recent contribution to BHR fits in the BHR awareness cluster: she took a sensemaking perspective and examined how managers in UK firms made sense of human rights.

The historical context of the evolvement of human rights can provide a fruitful perspective for future human rights research at the micro level. Throughout history, human rights have been standing for empowerment, self-determination and the betterment of one’s situation. Thus, ‘human rights have come to define the hopes of the present day’.Footnote 93 The micro-underpinnings of this (and how they determine employee and consumer behaviour) might be an interesting area of inquiry for future research. How do individuals (employees, consumers, etc.) interpret human rights and how does this interpretation affect their behaviour towards others and others’ human rights? While the UNGPs and other initiatives provide some guidance, there is no research on what kind of actual duties lie on individuals for respecting and protecting human rights. What duty does the individual employee have towards local and distant consumers or other stakeholders such as employees in supplier factories? And how do such duties translate into the daily tasks of the employee?

When addressing these questions, attention focus theory, identity theories and sensemaking theory could be helpful. Identity theories focus on what influences the creation of identity and how identity then affects behaviour.Footnote 94 Thus, an identity-focused theory could highlight how employees identify with human rights abuses of fellow employees or other individuals such as consumers or community members.

Raising BHR awareness will ultimately have an impact on the individual, the manager and employee (upper left box in Figure 1). Until now there have been no studies examining the effect of a firm’s involvement in human rights abuses or a firm’s acceptance of human rights obligations on individual employees. What are the outcomes of a firm’s human rights commitment? Does corporate human rights commitment affect an employee’s organizational identification and motivation? What are the effects of corporate complicity in human rights abuses on employee morale or a corporation’s attractiveness to prospective employees? There have been a few studies which examined a firm’s corporate social responsibility policies and their effects on employees,Footnote 95 but there have been no studies on the impact of human rights abuses on the firm–employee relationship. While ObaraFootnote 96 examined how employees make sense of human rights, it is equally relevant to examine how employees perceive human rights abuses by their corporations. How do employees react, justify and defend their corporations’ actions?

Insights from sensemaking theory can be helpful in addressing the aforementioned questions. Sensemaking is about language and communication. Ring and Rands define sensemaking as a ‘process by which individuals develop cognitive maps of their environment.’Footnote 97 Peoples’ senses and assigned meanings to reality are derived from their cognitive predispositions, beliefs and assumptions. Sensemaking is dynamic, social and retrospective. It assumes that social reality depends on cognitive structuresFootnote 98 and that people ‘deal with their realities and especially the actions that have to be undertaken by them in continuous learning processes, fed by experiences and driven by the sensegiving capacity of the human mind’.Footnote 99 A sensemaking approach to BHR can provide a fruitful path in examining the effects of human rights abuses and/or policies on employees.

Table 8 provides an overview of the above discussion on future BHR research, the different theoretical perspectives, sample research questions, and some proposed research methods. Given the type of research questions and data available, we suggest mostly qualitative research methods.

V. Discussion: BHR as a Subfield of Study Within SIM

Within SIM, there are a variety of subfields that follow the pattern we propose that BHR might usefully pursue. Like other fields such as corporate social performance, corporate political activity and sustainability,Footnote 100 we see BHR as emerging as a subfield of study within SIM. Like fields, subfields develop when inquiries or conceptual and empirical problems are not addressed in existing fields in such a way as to adequately move and develop the inquiries and problems further.Footnote 101 This might be due to various reasons such as that existing fields or subfields have different epistemological positions, assumptions, methodologies and perspectives that make them less than fully applicable to new areas of inquiry. Wettstein, for example, stresses that ‘human rights claims deal with the indispensable and thus with what is owed to human beings.’Footnote 102 Abuses of human rights are humiliating to the victims and exemplify a disregard towards the individual’s human qualities. Thus, human rights abuses are closely linked to a quest for remedy, to undo the humiliation and restore one’s dignity and freedom. Given this foundation, BHR can be understood as having developed out of a crisis with increasing cases of human rights abuses resulting in a search for remedying existing harm.Footnote 103 In contrast, existing subfields within SIM such as CSR and corporate social performance sought to advance the proposition that businesses could not only ameliorate the harms caused by their activities to stakeholders and society, but also create positive benefit for them. Our review of BHR scholarship within SIM illustrates how BHR has gradually separated itself from other related subfields in SIM to develop as its own SIM subfield. This development occurred in several waves.

When reviewing the BHR literature we can roughly divide the literature in three overlapping waves. The first BHR research wave started in the 1990s. Here, BHR scholarship often focused on single issues such as child labour, discrimination or corruption, or industries such as oil and gas.Footnote 104 The BHR discussion appears to be rather scattered, isolated and disconnected as publications focused on particular issues and discussed firms’ role regarding that issue instead of a broader role of business for human rights.Footnote 105 It appears that individual human rights issues were examined in isolation of each other without much cross-referencing. In this first wave, scholars either embedded their discussion in a broad human rights narrative by referring to the UN Declaration of Human Rights or other initiatives, or they embedded their discussion in existing narratives such as CSR or business ethics.Footnote 106 Using the language of CSR, BHR scholars sought to delineate normative underpinnings – grounding in international law – for the extension of human rights responsibilities to corporations as non-state actors.

The second wave of BHR started with the appointment of law professor John Ruggie as the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative on Business and Human Rights in 2005. Amongst others, Ruggie’s mandate was to identify corporate responsibility and accountability standards in relation to human rights. With the establishment of this mandate, we observed an increased discussion on the broad topic of business and human rights and questions of whether firms have human rights obligations in general – in contrast to the more issue-focused discussions in the first wave. With the creation and tenure of the mandate, we observed increasing efforts by BHR scholars to examine corporate responsibility through international codes of conduct. WettsteinFootnote 107 sees a similar shift in the BHR discussion at that point. The creation of the UN mandate introduced the terminology of BHR. Until then, the term did not appear in scholarly work in SIM. At that stage, the BHR discourse was still frequently embedded in existing narratives such as CSR and publications were at the intersection of CSR and BHR or business ethics and BHRFootnote 108 with some isolated exceptions.Footnote 109

However, in our literature review we have seen a recent shift in BHR discourse. Several years after the establishment of the Ruggie mandate, scholars started using the term BHR more independently from other SIM concepts.Footnote 110 Thus, we see a third wave of BHR scholarship separating itself from existing concepts in SIM scholarship and paving the way towards BHR as a subfield of study in SIM.Footnote 111 Recent contributions to BHR refer to BHR in its own right without embedding it in other SIM concepts or making it part of other SIM concepts.Footnote 112 Our literature review on BHR revealed an evolution of BHR scholarship from a narrow, issue and industry-focused discussion, to an embedded discussion in connection with SIM concepts, to finally discussing BHR in its own right without explicitly referencing other SIM concepts. We posit, therefore, that in the future, BHR scholarship will continue to evolve as a subfield within SIM, albeit with its own terminology, in much the same way that other subfields within SIM have. The strength of SIM as a field is that it evolves over time to include new subfields that address issues related to ethical implications of business activity as well as business-government-society relationships that present new epistemological challenges. BHR within SIM is the latest, but surely not the last, expansion of the SIM field to take in relevant subfields.

VI. Conclusion

Undeniably, BHR constitutes an important topic that has gained momentum within SIM scholarship. The contribution of this article is threefold. The first contribution is the identification, examination and categorization of extant BHR scholarship within SIM. Our review provides scholars outside the BHR field with an understanding of past research accomplishments in BHR research. Our review highlights the evolution of BHR scholarship from a narrow and issue-focused discussion that was initially embedded in the CSR narrative to a broader discussion on business’ role in human rights. Second, we assessed the current state of BHR scholarship in SIM studies to date and identified gaps in the existing literature when it comes to (1) micro level analysis, (2) the implementation and outcome of corporate human rights management, and (3) empirical studies. Finally, we have sought to advance the view that BHR is emerging as a subfield of study in SIM.

BHR scholars are already convinced of BHR’s distinctiveness from other SIM subfields such as CSR, sustainability or corporate social performance. However, the key is to convince scholars outside the subfield of the need for its existence and legitimacy ‘because the aim of the aspiring community is to work alongside and be taken seriously by the other fields in the academic establishment’.Footnote 113 Legitimacy is particularly important for BHR scholarship because it is based on two interlocking normative claims. One normative claim is that binding human rights responsibilities already exist. The other normative claim extends human rights responsibilities – which have been traditionally the responsibilities of states – to non-state actors such as corporations. Both claims have been the subject of significant critique and analysis. Normative claims are often treated as suspect within management studies,Footnote 114 and thus a field that has normative claims embedded within its scholarship faces significant challenges to its legitimacy.

While our review revealed the rise of BHR scholarship within SIM, the question will be, ‘whether management scholars will embrace the BHR paradigm’.Footnote 115 While legal scholars have dominated BHR scholarship and made important contributions to it, our review has shown that significant contributions to BHR have also been done in other fields, namely in SIM. Having the exposure as an interdisciplinary field across other areas such as management will only further advance the development and impact of BHR scholarship. While BHR scholarship will benefit from an increasing exposure to other fields, it can equally inform other fields and issues.