1. Introduction

Among the traces of morphology that remain in Middle Chinese, one of the clearest is the transitivity-related voicing alternation (Chou Reference Chou1962: 79–80, Downer Reference Downer1973, Sagart Reference Sagart2003), exemplified by verbs such as 敗 pæjH ‘defeat’ and 敗 bæjH ‘be defeated’. Consensus does not yet exist on the proto-Trans-Himalayan origins of this alternation (Handel Reference Handel2012). According to the view of some scholars such as Mei (Reference Mei2012) the intransitive voiced verb is the base form, and the transitive one had its initial consonant devoiced by the sigmatic causative prefix *s- (Conrady Reference Conrady1896), while other scholars (Sagart and Baxter Reference Sagart and Baxter2012) argue that this alternation is unrelated to the causative prefix, and that the base form is the transitive verb instead.

To support his hypothesis, Mei (Reference Mei2012) draws on a typological example offered by Tibetan, where according to his source, Shefts-Chang (Reference Shefts-Chang1971), the sigmatic causative devoices voiced obstruents. In this paper, I evaluate Shefts-Chang's claim, and show that an alternative explanation is more economical.

2. The sigmatic causative as a devoicing prefix in Tibetan

Although the causative s- prefix in Tibetan is not productive, unlike in Japhug (Jacques Reference Jacques2015a) or Jinghpo (Kurabe Reference Kurabe2016: 88), it is nevertheless well-attested, and Zhang (Reference Zhang2009) lists more than 100 examples. Causativization can be accompanied with a change of flexion class due to the valency increase; for instance sboŋ, sbaŋs ‘soak’ has the vowel alternation found in some transitive conjugation classes (Coblin Reference Coblin1976) lacking in the base verb ⁿbaŋ, baŋs ‘be soaked’, but this alternation is only an indirect effect of the addition of the causative prefix.

Yet Shefts-Chang (Reference Shefts-Chang1971: 682–6) observes that the causative form of a few verbs whose intransitive counterpart has a voiced stop b- have a causative form with an unvoiced cluster sp-:

1. spub, spubs ‘cause to be turned upside down’ from ⁿbub, bub ‘be turned upside down’.

2. spʲiŋ, spʲiŋs ‘sink, slower, let down’ from ⁿbʲiŋ, bʲiŋ ‘sink in’.

3. spor, spar ‘cause to burn’ from ⁿbar ‘burn’.

She concludes from these examples that the causative s- regularly devoices the following stops (1).

(1) *s-b- > sp-

*s-d- > st-

*s-g- > sk-

In her view, counterexamples such as sboŋ, sbaŋs ‘soak’ from ⁿbaŋ, baŋs ‘be soaked’ must either be interpreted as the result of analogical levelling, or accounted for by more complex clusters such as *s-ⁿbaŋ-s (*b-s-ạ-baŋ-s in Shefts’ notation), where the phonetic element surfacing as ⁿ- in the present tense form of the intransitive verbs prevents the sibilant fricative from devoicing the following stop (Shefts-Chang Reference Shefts-Chang1971: 681).

Although Shefts only adduces examples with labial initial, similar examples can be quoted with velar initials:

1. skon, bskon ‘dress’, ‘cause to wear’ (gʲon-du ⁿdʑug.pa) if from gʲon ‘wear’ (a variant gon without medial is also attested); this example is rejected by Shefts-Chang (Reference Shefts-Chang1971: 692), who argues that skon is rather the causative form of an etymon *(ⁿ)kʰon ‘get caught’ (Shefts-Chang Reference Shefts-Chang1971: viii) reflected by the colloquial Lhasa Tibetan verb kʰø̃́ː ‘get hooked accidentally’ (under the entry ⁿkʰon in Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Shelling, Surkhang and Robillard2001). This etymology is followed by Zhang (Reference Zhang2009: 214).

2. skoŋ, bskaŋs ‘fulfil’ from gaŋ ‘fill, intr.’.

No examples are found with dental initials and affricates.

3. Voicing triplets

Before offering an alternative hypothesis to account for Shefts’ examples, it is necessary to present some background information concerning Tibetan verbal morphology.

Tibetan has a certain number of triplets presenting voicing alternation (Uray Reference Uray1953), which we refer to as A, B, and C following Hill (Reference Hill2014a); the alternations between z- and ts- are due to a sound change *dz- > z- (Hill Reference Hill, Simmons and Van Auken2014b).Footnote 2

1. A: ⁿgag ‘be stopped, break off’

B: ⁿgegs, bkag ‘hinder, prohibit’

C: kʰegs ‘be hindered, be prohibited’

2. A: gaŋ ‘fill, intr.’

B: ⁿgeŋs, bkaŋ ‘fill, tr.’

C: kʰeŋs ‘be full’

3. A: gab ‘hide, intr.’

B: ⁿgebs, bkab ‘cover, tr.’

C: kʰebs ‘be covered over’

4. A: grol ‘be free’

B: ⁿgrol bkrol ‘liberate’

C: kʰrol ‘unravel’

5. A: dul ‘be tame’

B: ⁿdul, btul ‘tame, subdue’

C: tʰul ‘be tame’

6. A: zug ‘pierce, penetrate’

B: ⁿdzugs, btsugs ‘plant, establish, insert’

C: tsʰugs ‘go into, begin’

The A and C verbs are intransitive, and the B-type verbs are transitive volitional. The A-type and C-type verbs have voiced (for instance ⁿgag ‘be stopped, break off’) vs unvoiced initials (kʰegs ‘be hindered, be prohibited’) respectively and B-type have a voicing alternation, with voiced initial in the present (ⁿgegs ‘hinder’) and future (dgag) tenses and unvoiced initial in past (bkag) and imperative (kʰog). Although some forms display aspiration alternation in Classical Tibetan and modern varieties, the aspiration contrast was not phonemic in pre-Tibetan (Li Reference Li1933, Coblin Reference Coblin1976, Hill Reference Hill2007) and will be disregarded in this paper.

The origin of these alternations is not agreed upon by all scholars. Some, working mainly on Tibetan-internal data, believe that the voiced initial of the A form is primary and that the unvoiced initial is due to devoicing (Zemp Reference Zemp2016). Another approach, based on comparison with Rgyalrongic and Kiranti, analyses the unvoiced (transitive) B form as the base form (Jacques Reference Jacques2012b). In this view, the A form corresponds to the anticausative derivation found in most conservative Trans-Himalayan languages (Jacques Reference Jacques2015b), the voiced initial being the result of voicing by the addition of a nasal prefix, with subsequent merger of prenasalized voiced and plain voiced initials in Tibetan. The voiced forms of the B paradigm in the present and future tenses are analysed as being due to a nasal prefix distinct from the one of the B form. The C form is then analysed as directly deriving from the base root by an intransitivizing *-si prefix (Jacques Reference Jacques2016) cognate to the reflexive-middle of Kiranti, Dulong, and other languages (on which see for instance van Driem Reference van Driem1993, LaPolla and Yang Reference LaPolla and Yang2004, Jacques et al. Reference Jacques, Lahaussois and Rai2016).

The ultimate origin of A, B, and C triplets is, however, not of immediate concern to the question discussed in the present paper. In the following section, the only assumption that is made is that the A, B, and C forms in the triplets above are related to each other by morphological derivations, and some triplets of proto-Tibetan may have lost an A, B, or C form.

4. An alternative analysis

The verb ⁿbub, bub ‘be turned upside down’ quoted by Shefts as the base of spub, spubs ‘cause to be turned upside down’ is in fact an A-form, whose corresponding B-form with voicing alternation ⁿbubs, pʰub ‘pitch up (a tent), cover (the roof a house)’Footnote 3 has a larger range of meanings.Footnote 4 No C form such as *pʰubs is attested for this root. In addition, it should be pointed out that the regular causative sbub, sbubs ‘turn upside down’ from ⁿbub, bub is also attested.

A solution offers itself to account for all of these forms without assuming any special sound change: as represented in Figure 1, the two causatives sbub, sbubs and spub, spubs actually respectively derive from the A-form and the past stem of the B form.

Figure 1. The tree of derivations relating the verbs bub, pʰub, sbub, and spub

The meaning of these causatives is not completely equivalent, and is a clue to their distinct derivational origin. While sbub, sbubs indeed means ‘turn upside down’ in particular in collocation with kʰa ‘mouth’, the verb spub can take the noun tʰog ‘roof’ as object in the meaning ‘covering a roof on’, as shown by the literary Ladakhi example (2), exactly as the B-form ⁿbubs, pʰub (tʰog pʰub ‘build, erect a roof’).

(2) sa.doŋ-la tʰog spub-ste

ground.pit-loc roof construct-conv

‘They constructed a roof for the pit in the ground.’ (Zeisler Reference Zeisler2004: 743, citing Franke Reference Franke1905: V: 185)

This example provides a model to account for the apparent voicing alternation between causative verbs and corresponding intransitive verbs, adduced by Shefts to support her devoicing hypothesis (see section 1 above): while the voicing alternation is real, it is unrelated to the sigmatic causative. The s-prefix can be applied to both A- and B- forms of the triplets discussed in section 3. B-causatives, based on the past tense alternant, have s + unvoiced stop clusters, while A-causatives have s + voiced stop clusters. The illusion of a devoicing effect arises if one mistakenly analyses the B-causative (for instance spub, spubs) as directly deriving from the A-form (ⁿbub, bub).

Applying the same analysis to other examples, skoŋ, bskaŋs ‘fulfil’ is also possible. As shown in Figure 2, this is a B-causative deriving from the transitive ⁿgeŋs, bkaŋ ‘fill, tr.’ rather than from gaŋ ‘fill, intr.’. The difference with the previous example here is that no corresponding A-causative exists.

Figure 2. The tree of derivations relating the verbs gaŋ, bkaŋ, bskaŋs, and kʰeŋs

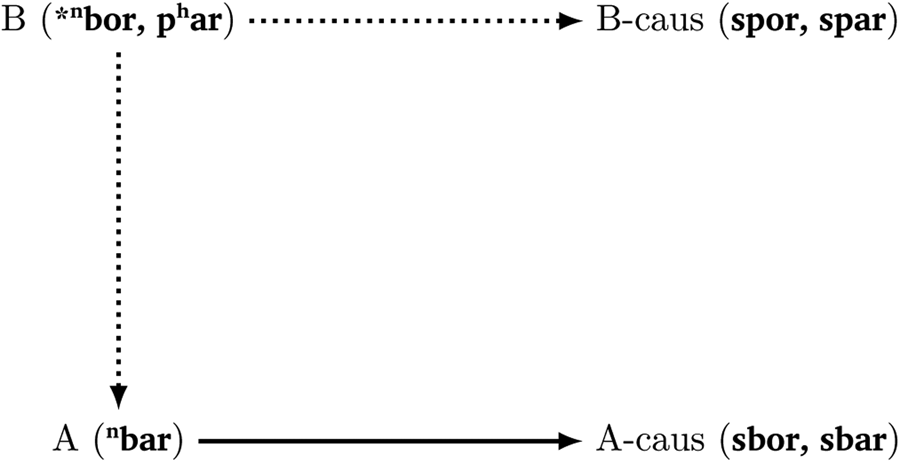

A more difficult case occurs when the B-type verb is not attested. For instance, ⁿbar ‘burn’ has two causatives spor, spar ‘cause to burn’ and sbor, sbar ‘ignite’. In this case, the hypothesis proposed in this paper implies that ⁿbar ‘burn’ is an A-type intransitive verb, whose B-type counterpart *ⁿbor, pʰar used to exist in pre-Tibetan. This verb derived the B-causative spor, spar but then disappeared (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. The tree of derivations relating the verbs ⁿbar, sbor, sbar and spor, spar

If the possibility of unattested B-type verbs *ⁿbor, pʰar is accepted, Shefts' putative sound law can be dispensed with entirely.

5. sC- clusters in nouns

An even more serious argument against Shefts’ hypothesis is the absence of evidence for the devoicing law in the nominal system.

There are a few lexicalized traces of a sigmatic s- oblique (instrumental/locative) nominalization (Jacques Reference Jacques2018). Sigmatic nominalization from verbs with voiced initial or even B-type verbs almost never presents devoicing, as would have been expected under Shefts’ law:

• ⁿbud, bus ‘blow’ → sbud.pa ‘bellows’

• ⁿgel, bkal ‘load on’ → sgal ‘load, back’

• ⁿdiŋ, btiŋ ‘lay out, spread out’ → sdiŋs ‘flat surface’

• dgar, bkar ‘pitch (tent)’ (as in gur bkar ‘pitch a tent’) → sgar ‘encampment’

• ⁿbub, bub ‘be turned upside down’ → sbubs ‘cavity, hollow space’ (place that has been covered up)

• ⁿbigs, pʰug ‘bore a hole’ → sbug ‘cavity, interior’

Since all traces of s- nominalization are synchronically opaque and lexicalized, analogy cannot be adduced to explain the voicing here.

The same is true of other frozen traces of nominal morphology in Tibetan. For instance, the noun sgaŋ ‘mountain’, which is historically related to gaŋs ‘ice, glacier’ by a s- prefix of unknown function, should have had a devoiced onset † skaŋ if Shefts’ sound law were correct. In this case analogy is impossible (since the formation is not only unproductive, but completely isolated), and the absence of prenasalization on gaŋs ‘ice, glacier’ prevents us from supposing that the voicing was preserved by the presence of a nasal preinitial such as *sŋg- > sg-.

6. sC- clusters in modern Tibetic languages

Another type of evidence against Shefts’ hypothesis comes from the evolution of modern Tibetic languages from Old Tibetan. Table 1 lists the regular inherited reflexes of simple voiced stop onsets (without medial consonant) and the corresponding s + stop clusters in various Tibetic languages.

Table 1. The evolution of voiced stops in Tibetic languages

These data illustrate that the s- preinitial has exactly the opposite effect of Shefts’ hypothesis in many Tibetic languages: rather than devoicing the stop, the s- (like other preinitials) preserves the voicing and prevents the voiced stop from devoicing in word-initial position. The only variety in this table with unvoiced stops corresponding to Old Tibetan sb-, sd-, sg- is Lhasa, a language that lost the voicing contrast – the low register tone, however, indicates that the system of onsets of Lhasa originated from something like modern-day Dzongkha, with redundant voicing and low register.

There is only one Tibetic language whose correspondences with OT could seem to provide an example of s- devoicing: Chosrje (Sun Reference Sun2003b). In this language, OT sb-, sd-, sg- become unvoiced, while b-, d-, g- correspond to voiced stops, as if no change had taken place, as illustrated by a few examples in Table 2.

Table 2. The fate of OT voiced stop in Chosrje Tibetan

However, the fact that OT unvoiced unaspirated stops become voiced stops (for instance dzənde ‘sandalwood’, a word of Indic origin) shows that the voicing in words from OT voiced stops such as dʉʔ ‘poison’ cannot be interpreted as a preservation.

To account for the correspondences of voiced and unvoiced stops in all contexts, it is necessary to suppose a sound shift with three intermediate stages, as presented in Table 3. First, Chosrje went through a stage similar to that of Cone (I). Then, the stage I plain voiced stops (from OT sb-, sd-, sg-) devoiced with breathy voice (II). At stage II, the voiced stops only remained when prenasalization was present. Stage I *b (from OT *sb) became *w.

Table 3. The fate of OT velar stops in Chosrje Tibetan

At stage III, after word-initial devoicing took place, unvoiced unaspirated stops (from OT voiced and unvoiced unaspirated stops) both became voiced, but without breathy voice. Stage II *w (from OT *sb) became v. The attested Chosrje system (stage IV) can be derived from stage III by simply losing the tonal contrast.

It is clear therefore that Chosrje data do not offer a typological parallel to Shefts’ and Mei's devoicing hypotheses concerning pre-Tibetan and Old Chinese respectively.

7. Conclusion

Shefts’ devoicing hypothesis is not only problematic from a Tibetan-internal point of view, where it creates more problems than it solves for the analysis of morphological alternation, it is also devoid of any support from the evolution of Tibetic languages and also other language families, where no incontrovertible example of such a sound shift is attested (no example can be gleaned from Kümmel Reference Kümmel2007). The only known parallel for s- devoicing would be Lolo-Burmese, where a sigmatic causative has been reconstructed to account for voicing alternations (Bradley Reference Bradley1979, Gerner Reference Gerner2007, see also Dempsey Reference Dempsey2005 for an alternative hypothesis). I leave the examination of Lolo-Burmese data and Old Chinese to further investigations.