1. Introduction

Tangut, an extinct Sino-Tibetan language spoken by the rulers of the Western Xia Xīxià 西夏 empire (1038–1227), has been the subject of increasing attention during the past decade. Aside from works on its phonology and grammar, the question of its classification was raised again when scholars began to confront it with freshly documented languages of the West Gyalrongic subgroup within Qiangic, Sino-Tibetan (which appeared to be closely related to Tangut). Recently, Lai et al. (Reference Lai, Gates, Gong and Jacques2020) included it under the West Gyalrongic taxon, and Beaudouin (Reference Beaudouin2023b) proposed two hypotheses: Tangut either as a Horpa language, or as a sister language of proto-Horpa.Footnote 1

In Gyalrongic languages, the importance of the verb, which displays polysynthetic features – especially Gyalrong (Jacques Reference Jacques, Sybesma, Huang, Behr and Handel2017) – implies that a study of the verb template is mechanically able to provide a great deal of comparanda. The present paper builds on the template of the Tangut verb first described by Jacques (Reference Jacques2011) to provide a cross-comparison with the currently most extensively documented languages of the West Gyalrongic taxon: Geshiza Horpa, Mazur Stau Horpa, and Wobzi Khroskyabs.

This cross-comparison helps draw out three historically attested poles of attraction (pillars) in West Gyalrongic, which provide new evidence for the proximity between Tangut and Horpa languages, and permit a discussion of a traditionally accepted feature of the Tangut templatic distribution in passing, namely, the unexpected absence of valency slot.Footnote 2

I propose here that the conservativeness of each pillar results from an attraction process by the head, which can be observed both synchronically and diachronically.Footnote 3 After undertaking a cross-comparison in section 2, which proposes attraction as the process responsible for the existence of these pillars, I describe the consistency of each pillar in section 3, before drawing up in section 4 the implications of the distinct types of attractions in terms of templatic analysis.

2. A diachronically consistent multipolar template

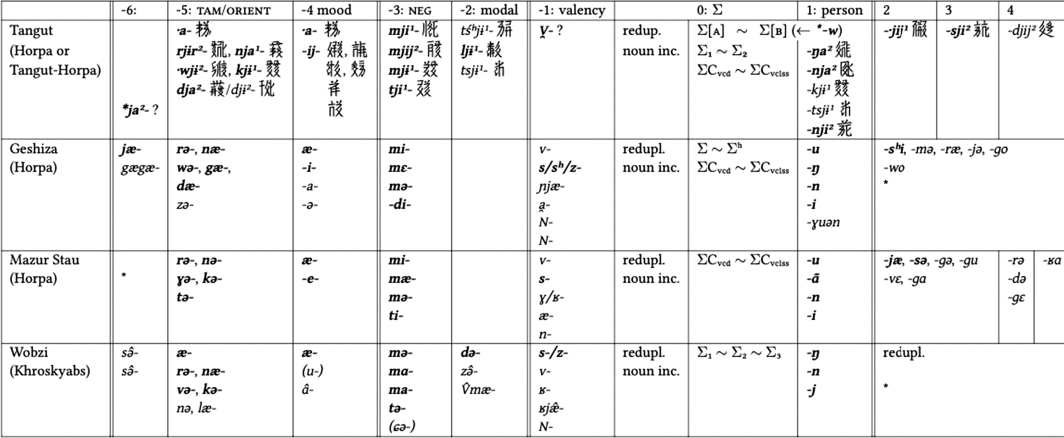

Table 1 gives a comparative overview of the verbal templates of Tangut, Geshiza Horpa, Mazur Stau Horpa, and Wobzi Khroskyabs. I will not explain here in detail for each language the nature and behaviour of the morphemes occupying each slot of these templates. Should readers require additional information on these languages, I invite them to consult the primary sources for this table, including Jacques (Reference Jacques2011), Jacques (Reference Jacques2014: 266), and Beaudouin (Reference Beaudouin2023b) for Tangut; Honkasalo (Reference Honkasalo2019: 231) for Geshiza Horpa; Gates (Reference Gates2021: 240) for Mazur Stau Horpa; and Lai (Reference Lai2017: 293, 846) and Lai (Reference Lai2021) for Wobzi Khroskyabs.Footnote 4

Table 1. Verbal templates for Tangut, Geshiza Horpa, Mazur Stau Horpa, and Wobzi Khroskyabs

* Wobzi has a cognate morpheme =sji, analysed as a clitic though, hence its absence within this slot.

The post-agreement suffixes in Geshiza have a fixed placement corresponding to the displayed order (-wo cannot occur with other suffixes).

Mazur Stau has two morphemes zə- and kɛ- that serve as superlative and intensifier respectively, not included in Slot -6 due to their potential derivational role.

This table is built on zones I call “pillars”, which include the verbal slots of each language and permit an analysis combining diachronic and synchronic descriptions. These pillars are diachronic constructs displaying consistency through time and where one can establish – except for Slots 2 to 4, currently only calqued on Tangut – one-to-one correspondences between all the languages’ slots of this study.

At the same time, for each language considered independently, the different slots’ morphemes establish mutual morphosyntactic or phonetic dependencies taking place within their templatic “domain”, which are synchronic constructs of morpho-semantical boundaries. As we will see, the range of the domain amounts here to those of the pillars due to the proximity of the languages, which often allows us to refer to a “domain/pillar” construct.

3. The three templatic pillars of West Gyalrongic

The present section summarizes, in 3.1 and 3.2, the various attraction processes and cognacies seen within each domain/pillar. The analysis ends with the stem's pillar (3.3). But first, one has to exclude from the analysis Slots 2 to 4, as the principal feature of these morphemes is to not establish links between themselves. This feature is correlated with the impossibility of granting them the status of pillar: even if particular ordering also exists in Geshiza (Honkasalo Reference Honkasalo2019: 607) and in Tangut (which is used as a reference), their only common characteristic from this perspective is to be at the right of the stem. Otherwise, affix ordering differs significantly in each language, even if they all share a cognate inferential morpheme (Tangut ![]() -sji2, Geshiza -sʰi, Mazur Stau -sə, Wobzi -si).Footnote 5 Mazur Stau and Tangut also share a telic/future cognate suffix (Tangut

-sji2, Geshiza -sʰi, Mazur Stau -sə, Wobzi -si).Footnote 5 Mazur Stau and Tangut also share a telic/future cognate suffix (Tangut ![]() -⋅jij¹, Mazur Stau -jæ).Footnote 6

-⋅jij¹, Mazur Stau -jæ).Footnote 6

3.1. Pillar 1 (Slots -6 to -4): TAM, orientation, mood and others

The first phenomenon of attraction can be seen in the two series of orientational preverbs displayed by Tangut, Geshiza, and Mazur Stau. In Tangut, Geshiza, and Mazur, the cognate two series of orientational prefixes (Slots -5 and -4) result from the fusion of Slot -5's prefix with an irrealis prefix seen in Slot -4. This fusion phenomenon is visible from the endocentric point of view of the Tangut themselves, who created a distinct character for each of the outputs produced by flexion: ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() . Geshiza has in Slot -4 two other mood markers (-a- and -ə-) either lost in Tangut and Mazur Stau or innovated by Geshiza. It is currently still difficult to know if Tangut's autobenefactive

. Geshiza has in Slot -4 two other mood markers (-a- and -ə-) either lost in Tangut and Mazur Stau or innovated by Geshiza. It is currently still difficult to know if Tangut's autobenefactive ![]() djɨ2- is a proper innovation, a retention lost elsewhere in West Gyalrongic, or an innovation shared with other West Gyalrongic languages then lost; its use is already quite restricted in Tangut, collocating with only 13 verbs, which makes me favour this last hypothesis. Wobzi Khroskyabs displays two preverbs, nə- and læ-, shared in common with Gyalrong languages, but lost by Tangut and the Horpa languages (Beaudouin Reference Beaudouin2023b: 618–23). On the whole, the proximity is clearer between Tangut and Horpa languages: the presence of the two series of orientational preverbs, the absence of two preverbs Wobzi shares with East Gyalrongic, and the aberrant presence of a syllabic inverse in Wobzi at a place where it would be difficult to disappear in Tangut (if we compare with its probable former non-syllabic presence in Slot -1) advocate for this classification.

djɨ2- is a proper innovation, a retention lost elsewhere in West Gyalrongic, or an innovation shared with other West Gyalrongic languages then lost; its use is already quite restricted in Tangut, collocating with only 13 verbs, which makes me favour this last hypothesis. Wobzi Khroskyabs displays two preverbs, nə- and læ-, shared in common with Gyalrong languages, but lost by Tangut and the Horpa languages (Beaudouin Reference Beaudouin2023b: 618–23). On the whole, the proximity is clearer between Tangut and Horpa languages: the presence of the two series of orientational preverbs, the absence of two preverbs Wobzi shares with East Gyalrongic, and the aberrant presence of a syllabic inverse in Wobzi at a place where it would be difficult to disappear in Tangut (if we compare with its probable former non-syllabic presence in Slot -1) advocate for this classification.

The cognate for the homonyms ![]() ⋅a- “upwards”, INTRG (Tangut) and æ- “upwards”, INTRG (Wobzi) are absent in Geshiza and Mazur. However, this homonymy phenomenon is also attested in g.Yurong Horpa (Lai Reference Lai2017: 321), making it a trans-West Gyalrongic matter, potentially a geographical innovation that spread in varieties of Khroskyabs and Horpa that were already in contact.Footnote 7 The attraction process seen between the orientational preverbs of Slot -5 (and perhaps another prefix of Slot -6 as described below) and Slot -4 (mood) may provide a cognitive background to this kind of reanalysis.

⋅a- “upwards”, INTRG (Tangut) and æ- “upwards”, INTRG (Wobzi) are absent in Geshiza and Mazur. However, this homonymy phenomenon is also attested in g.Yurong Horpa (Lai Reference Lai2017: 321), making it a trans-West Gyalrongic matter, potentially a geographical innovation that spread in varieties of Khroskyabs and Horpa that were already in contact.Footnote 7 The attraction process seen between the orientational preverbs of Slot -5 (and perhaps another prefix of Slot -6 as described below) and Slot -4 (mood) may provide a cognitive background to this kind of reanalysis.

Slot -6 contains morphemes pertaining in each language to different categories (aspect, comparison, etc.). Beaudouin (Reference Beaudouin2021) proposed that ![]() ⋅jij¹ (Slot 4's last morpheme), which appears in continuative constructions, is not derived from the orientational prefix

⋅jij¹ (Slot 4's last morpheme), which appears in continuative constructions, is not derived from the orientational prefix ![]() ⋅a-, but from a proto-form *ja- (Slot -6) cognate with the continuative jæ- of Geshiza. If this is true,

⋅a-, but from a proto-form *ja- (Slot -6) cognate with the continuative jæ- of Geshiza. If this is true, ![]() ⋅jij¹ would result from another fusion, i.e. that of Slot -6 and Slot -4 morphemes.Footnote 8

⋅jij¹ would result from another fusion, i.e. that of Slot -6 and Slot -4 morphemes.Footnote 8

All of these phenomena show the existence of a coherent diachronic, maybe cognitive construct, the slots -6 to -4 establishing between themselves phonetic and semantic links, leading either to flexion (leftward attraction of the affixed orientational/continuative preverb) or reanalysis (rightward attraction of the interrogative preverb).

3.2. Pillar 2 (Slots -3 and -2): negation and modals

The four cognate negative prefixes of Slot -3 (with the unique discrepancy of an interrogative prefix ɕə- in Wobzi) do not receive influence from the slots of the preceding pillar, and can therefore be seen as independent of them, as well as of the stem, which does not undergo modifications because of them nor exert modifications on them.Footnote 9 The relation between Slot-3 (neg.) and Slot -2 (mod.) is one of selection: the modal preverb selects the modal negation (as would a modal verb). As explained below, this feature is probably the cause of the independence of this slot.

Slot -2 exists only in Tangut and Wobzi Khroskyabs, with the sole cognacy between Tangut ![]() ljɨ¹- and Wobzi də-, used in concessive constructions; no modal preverbs are attested between the negation and Slot -1 in the Horpa languages of this study. One may analyse this slot as archaic; however, this does not mean that the morphemes filling that slot are archaic. The potential

ljɨ¹- and Wobzi də-, used in concessive constructions; no modal preverbs are attested between the negation and Slot -1 in the Horpa languages of this study. One may analyse this slot as archaic; however, this does not mean that the morphemes filling that slot are archaic. The potential ![]() tśʰjɨ¹- in Tangut may be an independent grammaticalization of a plain verb meaning “to be able to” (or which evolved towards such a meaning), cognate to the verb tɕʰa “to be able to” of Geshiza (the grammaticalization process would then explain the neutralization of the vowel). This probable path leads to another possibility for

tśʰjɨ¹- in Tangut may be an independent grammaticalization of a plain verb meaning “to be able to” (or which evolved towards such a meaning), cognate to the verb tɕʰa “to be able to” of Geshiza (the grammaticalization process would then explain the neutralization of the vowel). This probable path leads to another possibility for ![]() ljɨ¹- and də-, whose cognacy may potentially be traced back to a non-templatic stage, i.e. when these two morphemes were not preverbs yet.

ljɨ¹- and də-, whose cognacy may potentially be traced back to a non-templatic stage, i.e. when these two morphemes were not preverbs yet.

3.3. Pillar 3 (Slots -1 to 1): in the orbit of the stem

Traditionally, Slot -1 (valency) is found everywhere except in Tangut. This anomaly has been understood as a diachronic characteristic of Tangut, documented as “compression” by Miyake (Reference Miyake and Popova2012), a phenomenon which results, with a more dynamic perspective, from the attraction exerted by the verb stem. Tangut is usually reconstructed as a language that has lost the morphemes present in Slot -1 of its sister languages; however, even if true, phonemically, the distinction encoded by these morphemes survived at the stem level, with no fewer than three alternations (four if one uses the tense hypothesis developed by Nishida and Gong – see the paragraph below).Footnote 10

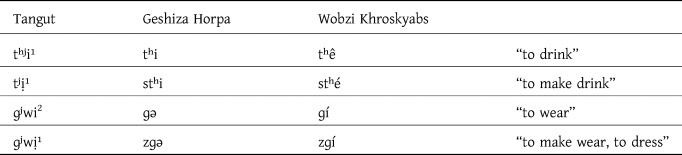

One of the most solidly documented alternations of the verb has been that seen with some syllables of the first minor cycle, noted as a dot since Nishida (Reference Nishida1964–66: T1, 68) and referring to tense vowels. In the case of alternating pairs of verbs of opposed valencies, the origin of this distinction has been explained by Gong (Reference Gong1999) as a reflex of a former causative *s-, whose presence is indeed still accountable in Tangut's closest relatives, as Table 2 shows.Footnote 11

Table 2. Causative pairs in Tangut, Geshiza Horpa, and Wobzi Khroskyabs

However, on the basis of internal and external data, Beaudouin (Reference Beaudouin2023a: §9.3) has proposed reconstructing the syllables of the first minor cycle as prevocalized. This phenomenon, first described in Horpa languages by Honkasalo (Reference Honkasalo2019) (see also Honkasalo and Gates Reference Honkasalo and Gates2023), may have happened earlier in Tangut. If true, this would indicate that Slot -1 in Tangut was not void as previously thought. Further research may or may not confirm the validity of such a hypothesis, which for now already has the positive effect of calibrating the templates and resolving the anomaly.Footnote 12

The ancient *-w of Slot 1 (agreement) is cognate to Geshiza and Mazur Stau's -u, and produced the apparition of Stem B, through fusion with the stem.Footnote 13 The same attraction phenomenon can be seen through the apocope that the agreement suffix underwent in Tangut's sister languages.

The Tangut verb also displays alternations that can be traced back to a pre-Horpa or even pre-West Gyalrongic stage; the voicing contrast due to a former causative prenasalization pertains to this situation. In Table 3, by referring to the Bragbar Situ form (Zhang Reference Zhang2020), one can see the prenasal origin of the voicing phenomenon in West Gyalrongic. In Tangut, the alternation is not as productive as in other languages of the West Gyalrongic subgroup, which can still display a prenasalized morpheme N- in Slot -1.

Table 3. Anticausative pairs in Tangut, Geshiza Horpa, Wobzi Khroskyabs, and Bragbar Situ

4. Types and layers of templatic dependency in WR

The analysis conducted above reveals two kinds of dependency in the West Gyalrongic verbal template construct.

The first is attraction, i.e. the most fundamental domain-internal relationship between a head and its dependent(s). This kind of relationship can only occur within a pillar, and is diachronically responsible for segmental changes. One can include here phonetic attractions such as fusion/flexion (orientational preverbs and continuative, stem alternations) and apocope (agreement suffixes), and also semantic attractions such as the reanalysis seen for a preverb (if this last hypothesis is correct).Footnote 14

The second one is selection, when a head chooses one morpheme among different (allomorphic) options – from the point of view of the allomorph, the existence of the head is a condition of its existence. For instance, a modal verb or preverb chooses the modal negation, which can conversely only appear if this verb or preverb is here. The same is true in Geshiza and Tangut for the inferential, the orientational preverbs encoding perfective or interrogative, and the perfective negation, which all are conditioned by the existence of a past verb stem except in prospective constructions; the same phenomenon applies to the telic, the orientational preverbs encoding imperative or optative, the prohibitive, and the general negation, which all require a non-past stem of the verb (Beaudouin Reference Beaudouin2023b; Honkasalo Reference Honkasalo2019: 137, 272, 443, 545, 600, 613, 636). As one can see, the selection crosses the frontiers between pillars and usually involves the verb stem. This allows us to draw up a differentiation between the central slots (comprised between Slot -1 and Slot 1), and the other peripheral slots, which display a form of relative independence that allows the existence of non-stemic pillars, i.e. a conjunction of domains with their particular heads, which are still selected by the stem. I summarize this conjunction of selections and attractions in Table 4.

Table 4. Conjunction of selections and attractions in the Tangut verb

This last dependency may allow one to infer a phenomenon that can explain the exception seen in the previous point, i.e. that of a modal preverb being able to select the modal negation without being a verb. From a diachronic point of view, this is not a problem, because these preverbs probably used to be plain verbs. From a synchronic perspective, we may call the granting by the stem of the ability to select delegation, and suppose it happens also for each pillar. In other words, a pillar, defined by its attraction or selection competency, would be a pillar thanks to the delegation conferred to the attracting slot by the stem.

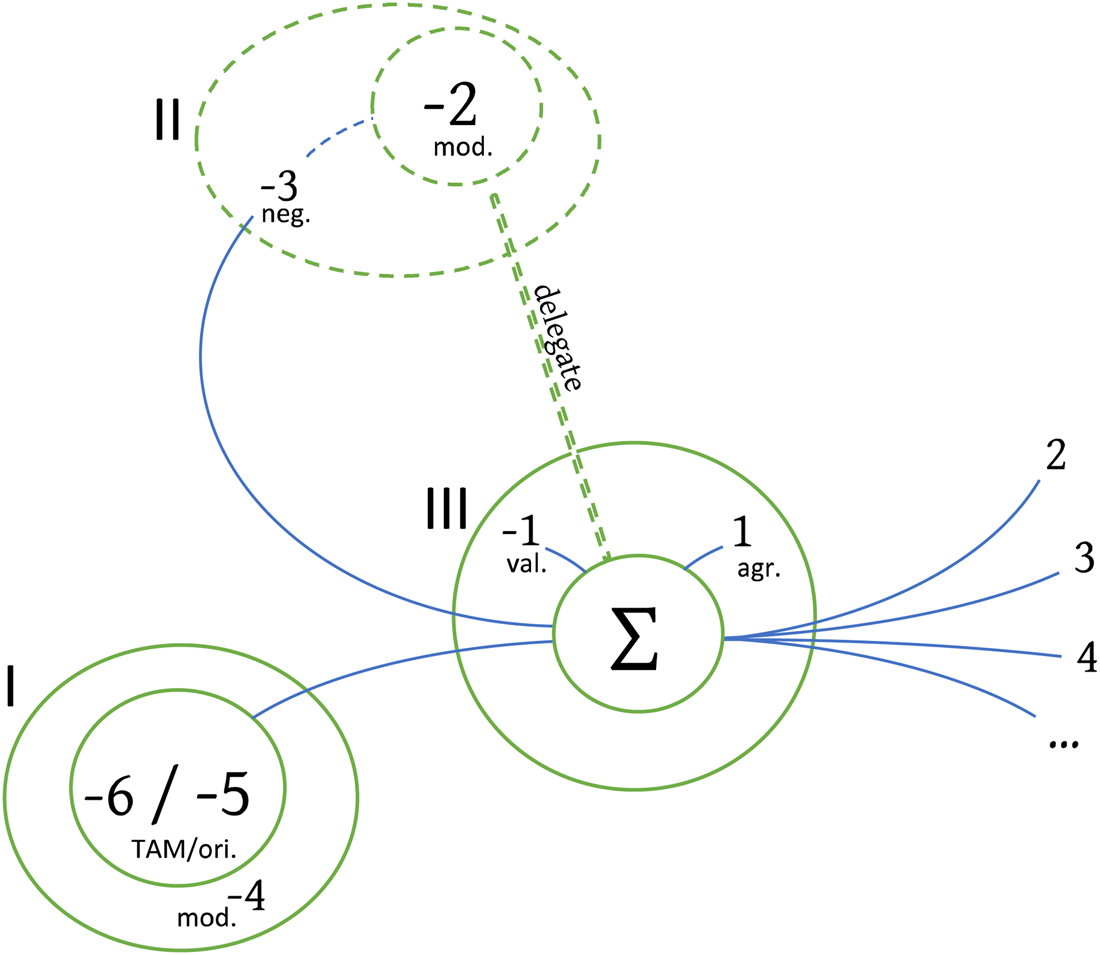

From such a perspective, one may privilege the word “decentralization” over that of independence, as a verbal morpheme in such a frame cannot be absolutely independent of the stem; in West Gyalrongic language, I propose that this decentralization is achieved through delegation of selection and attraction power, in a manner that is correlated with structural leftward preference, and allows drawing different levels of dependency as illustrated in Figure 1. In this figure, one can see attraction represented in a concentric way, and selection as a projection from the stem (or from the modal preverb when there is one). The ensemble takes the appearance of a gravitational system.Footnote 15 These levels of dependency are coherent with the phenomena of attraction responsible for segmental changes.Footnote 16

Figure 1. The nuclear system of West Gyalrongic languages templatic morphology.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Tangut as a Horpa language?

The analysis presented here supports the point of view of Beaudouin (Reference Beaudouin2023b): the evidence seems to comfort a subgrouping with Horpa languages, as these languages present more cognates (among them two series of orientational preverbs) plus an affix ordering nearly identical to Tangut; however, one must keep in mind that such a subgrouping does not result from common innovations, and that there are potential common retentions with Slot -2 (the modal preverb slot) that seem to indicate a distance from Khroskyabs not as important as that revealed by other analyses, especially the phonetic one.

5.2. Attraction as an amphichronic explanatory process

The present paper made a distinction between two kinds of templatic dependencies: attraction and selection. Attraction has segmental repercussions and is domain-internal, whereas selection takes place at a semantic level, is stem-driven, and crosses the domains of each head.

Attraction is a data-driven tool allowing one to overcome the Saussurian distinction between synchrony and diachrony (Saussure Reference Saussure1995 [1916]) in a case where it perhaps becomes a handicap. This centenary distinction has its advantages (it forces us to analyse the structural linguistic grid at work at the moment of utterance) but also leads us to treat both aspects as if they were distinct, which then leaves unexplained the reasons for linguistic change.Footnote 17 Here, attraction is a dynamic concept that explains the flexional and selection processes taking place synchronically, the phenomenon of change, as well as the diachronic consistencies that produce pillars.

5.3. Templatic verbal morphology as nuclear morphology

The present study also showed that it is also untrue to refer to templatic morphology as a “multiple-headed” verbal morphology (Bickel and Nichols Reference Bickel, Nichols and Shopen2007: 51), at least in the case of West Gyalrongic, and, overall, not in an equal way. The verb stem is the only morpheme that is present in all the selection processes, the only exception being the selection power of a modal preverb, which has manifestly verbal origins. Delegation may be the tool through which a non-stemic morpheme can behave as a head and exert attraction over its domain.

Acknowledgements

I want to express my gratitude towards all those who helped improve (former versions of) this paper: the two anonymous reviewers, Guillaume Jacques, and Nathan Hill. Naturally, all remaining errors are entirely mine. The Tangut phonetic reconstruction I follow is Gong Hwang-Cherng (cf. Gong Reference Gong2002) system as it appears in Li (Reference Li2008).