Introduction

To call the Quran “a text without context”,Footnote 2 as F. E. Peters has done, is to draw attention to the fact that in spite of the substantial Judaeo-Christian literature which can be meaningfully compared with specific Quranic passages, such intertexts are usually separated from the Quran by a significant linguistic and geographic gap: they are written in Hebrew, Greek, Syriac or Ethiopic, and they come from regions which, on the basis of contemporary means of travel, would have been a journey of several weeks away from the Hijaz, the Quran's putative place of origin.

It is because of this elusiveness of the Quran's immediate cultural context that the figure of Umayya b. Abī l-Ṣalt is relevant to Quranic studies: for unlike most of ancient Arabic poetry, the poems attributed to him treat subjects that are also prominent in the Quran, such as God's creation of the world, the deluge, God's heavenly throne, the last judgement, paradise and hell, as well as Biblical figures such as Noah and Moses. Umayya is said to have been a contemporary of Muhammad – probably a somewhat older one – from al-Ṭā’if, a town about a hundred kilometres to the south-east of Mecca,Footnote 3 and is often described as a pre-Quranic monotheist, i.e., a ḥanīf.Footnote 4 If the poetry transmitted under his name were genuine, it would consequently allow us a tantalizing glimpse into the way Biblical traditions were framed in Arabic in the Quran's immediate environment.Footnote 5

The present article is interested in using some of the material attributed to Umayya for precisely this purpose. Based on Umayya's rendition of the destruction of the Thamūd, an ancient Arabic legend also recounted in the Quran, I will attempt to characterize the nature of the Biblical material that was in circulation in the Quranic milieu, and highlight some of the crucial differences, in both content and literary format, that exist between Umayya's version of the Thamūd narrative and that of the Quran. I shall begin with a number of introductory remarks about previous scholarship on Umayya and the ever-popular problem of authenticity.

1. A brief survey of previous research

Although no proper dīwān of Umayya's literary output has survived, poetic fragments ascribed to him are found in a wide spectrum of works from such diverse genres as Quranic exegesis, lexicography and historiography. This scattered corpus has attracted a certain measure of scholarly attention from the first decades of the nineteenth century. After Alois Sprenger first introduced the figure of Umayya to Western scholarship,Footnote 6 Clément Huart wrote an article in 1904 that labelled the poetry attributed to Umayya a “source” of the Quran.Footnote 7 Huart was unreservedly optimistic about the authenticity of these texts, and in cases of obvious overlap with the Quran generally held the Quran to be dependent on Umayya. Subsequently, a first systematic attempt to gather all of the available material was made by Friedrich Schulthess,Footnote 8 and in the 1970s, two more editions have appeared in the Arabic world.Footnote 9

Huart's article inspired a number of further publications of a generally more sceptical nature, the most important of which was a German monograph by Israel Frank-Kamenetzky, published in 1911, which attempted to identify all the parallels between the corpus of poetry ascribed to Umayya and the Quran, and then proceeds on this basis to distinguish between genuine poems and pseudepigraphic ones.Footnote 10 Although Frank-Kamenetzky's conclusions were approved by no less an authority than Nöldeke,Footnote 11 scepticism came to prevail: in 1926 Tor Andrae devoted a number of pages in his study on The Origin of Islam and Christianity to the poetry attributed to Umayya, and emphatically propounded the view that all of these texts had only emerged in Islamic times, as a poetic distillation of early Islamic exegesis and popular storytelling.Footnote 12 In spite of a 1939 book by Joachim Hirschberg (Jewish and Christian Doctrines in Pre-Islamic and Early Islamic Arabia) which devotes considerable space to Umayya,Footnote 13 Western research appears to have tacitly adopted Andrae's position, according to which all biblically-inspired poetry attributed to Umayya ought to be viewed as pseudepigraphic; in contemporary Quranic scholarship, the Umayya corpus is hardly ever used as intertextual background material that might help gauge the extent to which Jewish and Christian lore was known in pre-Quranic Arabia. In 1996 the issue was taken up again in an article by Tilman Seidensticker who, while admitting that some of the material was in all likelihood spurious, emphasized that a certain number of poems could responsibly be considered to be authentic.Footnote 14 Unfortunately, Seidensticker's measured evaluation of the problem has only partially succeeded in rekindling the debate,Footnote 15 although Seidensticker himself has recently returned to the issue and provided a distinctly helpful survey of different scholars' assessments of individual poems ascribed to Umayya.Footnote 16

2. The problem of authenticity

When glancing through the poems attributed to Umayya, it quickly becomes clear that at least some measure of scepticism is warranted, as many of the poems do indeed look like a pastiche of standard Quranic terminology. Poem no. 27 of the Schulthess edition (= al-Saṭlī, no. 63) provides a representative example of such cases (all passages which employ Quranic diction, or variants thereof, have been underlined;Footnote 17 see the Arabic text in the appendix):

1God of the inhabitants of the world Footnote 18 and of the entire earth and lord of the firm mountains (cf. 41: 10 and elsewhere),

2who built them, and also built seven strong [heavens] (Q 78: 12) without visible pillars (Q 13: 2 and 31: 10) and without men [i.e. helpers];

3and who made them even and adorned them (Q 15: 16 and elsewhere) with the light of the shining sun and the moon (cf. Q 10: 5)

4and of shooting stars that sparkle in its darkness; its missiles are sterner than arrowheads (Q 72: 8).

5He has split the earth, so that springs poured forth from it (cf. Q 7: 160 and 79: 31) and rivers of sweet and clear water,

6and he has blessed its regions (Q 41: 10) and caused to flourish in it the crops and cattle which are there (Q 2: 205).

7Inevitably, one day every long-lived one and every being in the world comes to its end,

8and vanishes after it has been new, and becomes worn out, except for Him who remains, the holy one (Q 59: 23 and 62: 1), full of majesty (Q 55: 78).

9The evildoers are led naked to a place where there are rods (Q 22: 21) and a warning punishment (Q 79: 25).

10They call out: “Woe is us (Q 37: 20), long-lasting woe!”, and they cry out in their chains (Q 40: 73 and elsewhere).

11They are not dead (Q 35: 36 and elsewhere), so that they would be able to rest and all of them roast in the ocean of the Fire (Q 88: 4 and elsewhere).

12The God-fearing, however, inhabit a home of sincerity (16: 30 and elsewhere), and enjoy a life of bliss (cf. Q 88: 8, 101: 7, and elsewhere) in the shade (Q 76: 14 and elsewhere).

13There they possess what they desire (Q 16: 57 and elsewhere) and wish for of delight and of consummate joy.

In this poem, the ratio of Quranic terminology to the remainder of the poem is evidently very high: only one verse out of thirteen does not contain Quranic phraseology. Moreover, the Quranic material is taken from a wide variety of surahs that belong to all four major periods of the Quran's genesis.Footnote 19 The poet hence appears to have been familiar with passages from different parts of the Quran and to have used whatever Quranic material came to his mind. By contrast, the assumption that the poem really does stem from Umayya would require that more than two dozen Quranic surahs drew, over a period of approximately two decades, from one single poem by Umayya – decidedly the less likely hypothesis.

In other poems attributed to Umayya, dependence on the Quran is even more pronounced and may occasionally take on a somewhat comic aspect (no. 46: 1–3 Schulthess):

1To the Lord of the Throne they will be presented – he knows what is public and what is said in secret –

2on the day when we come to Him, the compassionate Lord – His promise will surely come about (cf. Q 19: 61);

3on the day when you come to Him – as He has said – alone (Q 19: 95), when He will not leave out a righteous one nor one who has strayed.

Here, the third verse comes close to a formal citation of the Quran: “on the day when you come to him alone (fardan)” clearly reflects Q 19: 95 (wa-kulluhum ātīhi yauma l-qiyāmati fardā). Moreover, the verse is not merely used, the employment of fardan is also explicitly marked as a citation of something that “God has said”, i.e. as a quotation from the Quran.Footnote 20 In this verse even a pretence of the poem being a pre-Quranic text is no longer upheld. As an aside, this raises the interesting question of whether in certain circles the retrospective fabrication of ḥanīf-style poetry of the kind also ascribed to other supposed pre-Islamic monotheists might not have been a literary diversion rather than a genuine attempt at forgery.

In spite of the substantial uncertainty that adheres to much of the poetry ascribed to Umayya, it is nevertheless improbable that both he and the literature transmitted under his name have been fabricated from scratch. First, it is likely that some historical memory of him must have existed, which could then be used as a peg on which to hang later poetry. As a matter of fact, the first 22 texts collected in the Schulthess edition are conventional ancient Arabic poetry, such as panegyrics on a Meccan noble by the name of Ibn Juʿdān (no. 13 Schulthess). Ibn Hishām's Sīra attributes to Umayya a lament on the Meccans slain at Badr,Footnote 21 which gives credence to reports that Umayya was opposed to the early Islamic community based at Medina. But if Umayya had just been a minor poet who produced conventional fakhr and madīḥ poetry, then why was he credited, albeit falsely, with religious poetry? The most likely answer to this is that Umayya must have possessed at least a certain reputation as a poet treating religious, and more particularly, Biblical subjects. This assumption is borne out by the fact that apart from the two categories of poems just mentioned – conventional secular poetry and Quranic pastiches – the Umayya corpus also comprises a third class of texts: poetry that deals with Biblical material, yet does not conspicuously overlap with the Quran. It is the texts belonging to the first and the third class that Israel Frank-Kamenetzky, in his 1911 study on Umayya, considered to be authentic, while the second category should probably be viewed as later expansions of the corpus that were possible because the latter already included a certain amount of biblically inspired texts. Prima facie, then, the criterion Frank-Kamenetzky used in order to distinguish the authentic core of Umayya's poetry from later additions appears entirely reasonable: the more remote a poem from the Quran, the more likely it is to be authentic; on the other hand, if it exhibits a high density of Quranic elements, and if these amount to entire phrases and concatenations of words rather than isolated expressions, then there is a strong possibility that the poem is later.

This general principle stands in need of certain qualifications, however. First, as many earlier scholars have observed, the evaluation of whether or not a given piece from the Umayya corpus can be held to be authentic must not only take into account the density of Quranic elements it displays, but also whether it overlaps with later Islamic amplifications of the Quran's frequently terse treatment of a certain narrative or issue. It is particularly on these grounds that Seidensticker argues for the inauthenticity of (pseudo-)Umayya's rendition of the Annunciation of Mary (no. 38 Schulthess = no. 79 al-Satlī) in which “the Qur'an is not only quoted or paraphrased but occasionally interpreted in agreement with the tafsīr”.Footnote 22

Again, it cannot be ruled out with complete certainty that the Umayya, rather than the Quranic, text could have been chronologically earlier, since narrative details that the later Islamic tradition grafted onto the Quran might in fact have derived from pre-Quranic Jewish and Christian traditions; Umayya's poem about Mary could therefore be dependent on these latter rather than on their subsequent Islamic appropriation. Hence, one might conclude, the text may well be genuine.Footnote 23 Indeed, the fact that Islamic amplifications of Quranic narratives draw on pre-Quranic midrash literature has been demonstrated in Norman Calder's analysis of the Quranic story of Abraham's sacrifice (cf. Q 37: 102–11).Footnote 24 Interestingly, a poetic rendering of the narrative, expanded by some of the midrashic motifs that later entered Islamic exegesis, is also attributed to Umayya (Schulthess, no. 29: 9–21), and is accepted as authentic both by Frank-Kamenetzky and by Nöldeke.Footnote 25 This stands in striking contrast to the fact that Frank-Kamenetzky at least rejects the poem about Mary (no. 38 Schulthess) as spurious: although in both cases there is considerable overlap between a text attributed to Umayya, on the one hand, and the Quran as well as later tafsīr, on the other, Frank-Kamenetzky arrives at diametrically opposed assessments of the two texts, considering one to be inauthentic and the other to be genuine. Clearly, methodological consistency requires that one's evaluation of the two poems be harmonized in some way, or that significant differences between them be pointed out.

In order to avoid such an impasse between contradictory scholarly intuitions about texts like no. 29 and no. 38, it is probably advisable to say that although these poems perhaps cannot be shown conclusively to be inauthentic, any argument to the contrary that would try positively to establish that they are authentic is also open to serious (and in my view, much greater) doubt. Methodologically, this would seem to require that one refrains from using poems like the one about the Annunciation of Mary as intertextual background material for the historical-critical study of the Quran. The texts that we can safely juxtapose with the Quran are those that stem from what has been labelled above as the third category of texts ascribed to Umayya, namely poems that deal with Biblical material but which do not conspicuously overlap with passages from the Quranic corpus. It is important to point out that this principle of caution, although dictated by scholarly sobriety, comes at a certain price, as it will necessarily make the difference between Umayya's poetry and the Quran appear to be much greater than it would turn out to be if one were to go out on a limb, so to speak, and work with texts such as no. 29 and 38. The degree to which the Quranic texts will come across as “original” or innovative will therefore be directly proportional to the degree of scholarly risk one is willing to take.

Before turning to Umayya's treatment of the Thamūd narrative, it may be helpful to offer a brief thematic outline of at least those poems which historical-critical students of the Quran can, in my view, safely use for intertextual comparison. Two general thematic categories may be discerned in this corpus. First, there is a good deal of material on creation and cosmology. It is noteworthy that the texts do not contain a genuine creation narrative modelled on the Biblical book of Genesis, as one can find in a poem by the Christian ʿAdī b. Zayd which has recently been studied both by Kirill Dmitriev and Isabel Toral-Niehoff;Footnote 26 the texts rather go over different aspects of the finished cosmic structure as it presently operates.Footnote 27 This basic perspective is somewhat reminiscent of the Quran, which also focuses on nature's operations in the present rather than on how God has originated the world in the mythic past.Footnote 28 The second major topic is Biblical history, with a consistent focus on figures from the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, in particular Noah (no. 32: 24–36 and no. 28: 9–13 Schulthess). This predominance of Old Testament figures can also be observed in the early Quranic recitations.Footnote 29

In another respect, however, Umayya and the early Quranic surahs betray considerably different theological and anthropological concerns. For whereas the primary interest of the earliest Quranic surahs is in the eschatological collapse of the world and the resurrection of the dead (rather than explicit monotheism), as Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje argued as early as 1886,Footnote 30 eschatology is much less prominent in the poetry of Umayya. Although one text contains descriptions of hell and of paradise (no. 41: 1–9 Schulthess, see no. 75 al-Saṭlī), the end of the world and the resurrection are only briefly alluded to in the poems which can be considered authentic with some degree of certainty. And even Umayya's portrayal of hell concludes with a rather consolatory perspective: “They float upon it [hell] like particles of rubbish, if the compassionate Lord does not grant forgiveness” (no. 41: 5 Schulthess). There is thus a strong emphasis on God's mercy – in striking contrast to the early Quranic surahs' “theology of rupture”, where man in general (al-insān) is vigorously accused of ingratitude towards God and of his failure to fulfil basic requirements of social solidarity.Footnote 31

3. The destruction of the Thamūd: a comparison of Umayya no. 34 and Q 91

Against this general background I now propose to examine one particular passage from the Umayya corpus, taken from poem no. 34 of the Schulthess edition (see nos. 31 and 30 in al-Satlī's edition; the Arabic text is included in the appendix), and compare it to an early Quranic surah, Q 91 (al-Shams). Both texts describe the destruction of the ancient people of Thamūd that re-appears in later Quranic surahs.Footnote 32 Before examining Umayya's rendition of the Thamūd legend in more in detail, however, it is worth taking a brief glance at the overall structure of the poem as reconstructed by Schulthess:

vv. 1–4: exhortation to praise God (Praise God, for he is worthy of praise …); God's power to bring to life stones and the dead; the heavenly throne.

vv. 5–10: God's creation: everything that exists corresponds to an eternal prototype; animals created by God.

vv. 11–13: the Plagues of Egypt (ants, locusts, empty years, dust).

vv. 14–19: Pharaoh and his army drown in the Red Sea.

vv. 20–22: the Israelites in the wilderness.

vv. 23–32: Thamūd

vv. 33–40: description of a rain spell

It should be noted, however, that the version offered by Schulthess is pieced together from seven different fragments which may not all go back to one and the same author.Footnote 33 The fact that the Thamūd passage is likely to be authentic, as argued below, does not therefore mean that this also applies to the rest of the poem; as a matter of fact, at least the section that retells the drowning of Pharaoh (34: 14–19 Schulthess) should probably be considered post-Quranic, since it does not include any narrative elements that conspicuously diverge from the Quran and in two instances even contains what appear to be poetic restatements of Quranic passages.Footnote 34 The section on God's creation (vv. 5–10), on the other hand, can lay a much stronger claim to going back to Umayya himself, as it significantly differs from the Quran: the passage begins with a reference to the notion that everything that exists corresponds to a supernatural prototype, an idea also alluded to in another poem that is probably authentic (no. 25: 2 Schulthess)Footnote 35 but not found in the Quran; and as the objects of divine creation it lists mainly wild animals (bees, crocodiles, antelopes, gazelles, lions, elephants and wolves, but also pigs and roosters), whereas Quranic affirmations of God as the creator of the world (usually referred to as “āyāt passages”Footnote 36) are always markedly anthropocentric, insofar as they portray the world as a habitat that is above all geared to the needs of man.Footnote 37 In spite of the fact that Umayya shares with the Quran recognition of God as the creator of the world, his interest in wildlife rather than in nature as subjugated to human needs (as in agriculture or cattle breeding) is much closer to more conventional ancient Arabic poetry than to the Quran.Footnote 38

The upshot of this brief review of the poem in its entirety is that in spite of the fact that the seven fragments exhibit the same metre (khafīf) and rhyme (īrā / ūrā) and do appear to match up thematically, and in spite of the fact that Frank-Kamenetzky takes the entire poem to be authentic,Footnote 39 the text as reconstituted by Schulthess is the result of an extended process of gradual growth around an authentic nucleus that consisted at least of vv. 5–10 and vv. 23–32 (see below), and probably also the brief reminiscence of the Plagues of Egypt in vv. 11–13 which are also not particularly Quran-like. The fact that God's creation of the world and the destruction of the Thamūd were apparently dealt with in the same poem is clearly significant, as it shows that certain themes that appear intimately linked in the Quran – where God's power to punish the evil is frequently substantiated with his power to create and maintain the world – appear to have fused with each other already in the poetry of Umayya.

Let us now zoom in on the Thamūd passage of the poem:Footnote 40

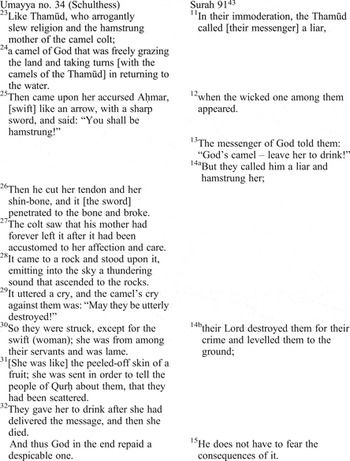

23Like Thamūd, who arrogantly slew religion (tafattakati d-dīna) and the hamstrung mother of the camel colt;

24a camel of God that was freely grazing the land and taking turns [with the camels of the Thamūd] in returning to the water.

25Then came upon her accursed Aḥmar, [swift] like an arrow, with a sharp sword, and said: “You shall be hamstrung!”

26Then he cut her tendon and her shin-bone, and it [= the sword] penetrated to the bone and broke.

27The colt saw that his mother had forever left it after it had been accustomed to her affection and care.

28It came to a rock and stood upon it, emitting into the sky a thundering sound that ascended to the rocks.

29It uttered a cry, and the camel's cry against them was: “May they be utterly destroyed!”

30So they were struck, except for the swift woman; she was from among their servants, and she was lame.

31[She was like] the peeled-off skin of a fruit; she was sent in order to tell the people of Qurḥ about them, that they had been scattered.

32They gave her to drink after she had delivered the message, and then she died. And thus God in the end repaid a despicable one.

Before we are entitled to use this text as an intertextual background to the Quranic treatment of the Thamūd story, however, we have a little dating problem to solve: is the poem really pre-Quranic? Prima facie this would seem to be the case, as the text is one of those poems that has biblically inspired subject matter yet does not show overt terminological overlap with the Quran; Israel Frank-Kamenetzky therefore considers it to be genuine.Footnote 41 In order to facilitate comparison with the earliest Thamūd narrative in the Quran,Footnote 42 the following synopsis can be drawn up:

The most striking point of divergence between both renditions of the Thamūd legend – noted in 1906 by E. PowerFootnote 44 – is the absence in the Umayya text of a messenger, a rasūl allāh, who instructs his people to leave the camel unharmed, yet is disobeyed. Conversely, the Umayya version also contains various elements absent from the Quranic one (notably, the little camel's curse and the escape of a maid of the Thamūd who announces their fate to the inhabitants of nearby QurḥFootnote 45). Yet Tor Andrae, in spite of these important discrepancies between Umayya and the Quran, nevertheless refuses to accept the authenticity of the text.Footnote 46 His reason for doing so is because even though our poem does not overlap with the Quran, it does overlap with traditions one finds in Islamic exegesis of the Quran. In particular, Andrae draws attention to a long report contained in al-Ṭabarī's commentary ad Q 7: 73 (tradition no. 14820) that is attributed to Ibn Isḥāq:

We were told by Ibn Ḥumaid, who said: We were told by Salama on the authority of Ibn Isḥāq, who said: When God had annihilated ʿĀd and their time had been over, Thamūd flourished after them and they were made to follow them in the land; so they settled there and spread out. Then they disobeyed God. And when their corruption had become evident and they worshipped things other than God, he sent Ṣāliḥ to them […].

This introduction is followed by a lengthy narrative: during one of their pagan festivals, the Thamūd challenge Ṣāliḥ to prove his prophetic authority by making a camel come forth from a rock. After having accomplished this, Ṣāliḥ instructs them to leave the camel unharmed and to allow it to take turns in drinking with their own camels. However, one of the women of Thamūd called ʿUnayza conspires against Ṣāliḥ and brings in Aḥmar from nearby Qurḥ in order to organize the slaying of the camel. When Aḥmar has carried out the deed, Ṣāliḥ announces that a divine punishment is about to befall the Thamūd, and retreats to Palestine when the threat is fulfilled.

All of them, young and old, perished, except for a lame servant girl of theirs who was called “al-Zuraiʿa” [apparently corrupted from al-Dharīʿa, “the swift one”]; she was an unbeliever and extremely hostile to Ṣāliḥ. God set her feet free after she had witnessed the entire punishment, and she left faster than anything that had ever been seen, until she came to the people of Qurḥ and told them about the punishment she had seen and how it had struck the Thamūd. Then she asked for something to drink, which she was given; and after she had drunk, she died.

Here, just as in Umayya, there is mention of a lame slave girl who manages, by the help of God, to escape from the disaster in order to tell the people of Qurḥ about it, and then dies after having delivered the news. According to Andrae, the parallel between Umayya and the narrative from al-Ṭabarī indicates that the poem attributed to Umayya is actually dependent on Islamic tafsīr traditions and must therefore be inauthentic. Yet Andrae's argument is hardly convincing. For the report from al-Ṭabarī, unlike the poem, does accord a very prominent position to the prophet Ṣāliḥ, as the anonymous “messenger” from surah 91 comes to be called in later Quranic texts (for example, in the Middle Meccan verse Q 26: 142). It is therefore much more likely, I think, that the narrative from al-Ṭabarī is an attempt to integrate the Quranic account of the destruction of the Thamūd with an older Arabian version of the same event that lacked reference to a messenger figure, but included other details that the early exegetes found illuminating or interesting. From its sheer length, it is clear that the Ibn Isḥāq version of the destruction of the Thamūd attempts to present a unified and exhaustive account of what befell the Thamūd, an account that blends different strands of tradition. The poem attributed to Umayya, on the other hand, is very probably representative of one particular such tradition, as it contains virtually no Quranic elements.Footnote 47 The Thamūd story, then, is really a case where the later tafsīr tradition reworks pre-Quranic material and uses it to flesh out Quranic narrative.Footnote 48 It is thus likely that the Thamūd passage ascribed to Umayya is indeed pre-Quranic, since the hypothesis that the Thamūd poem was produced only after the advent of Islamic scripture is difficult to square with explaining how the poem could have remained so strikingly untouched by what the Quran has to say on the subject. The possible rejoinder, that even a chronologically post-Quranic poem may not have derived from the Quran, hardly appears convincing given that Quranic wording is so clearly reflected in some of the obviously spurious material attributed to Umayya.

What, then, may be said about the relationship between Umayya 34 and surah 91? First, a general observation about the historical placement of the Thamūd. As can easily be observed, the Quran has a stock list of former peoples that have been punished by God on account of their sins; the Quran adduces these historical examples of a limited intervention of God in history in order to show that God is able also to bring about a universal judgement at the end of history. Throughout the early and middle Meccan periods, the cycle of these “punishment legends”Footnote 49 can be seen to grow; later surahs give a list of up to seven episodes (cf. surah 26). As the early surah 89 demonstrates, however, at the beginning of the Quran's genesis the list only encompasses three elements: ʿĀd, Thamūd, and Pharaoh. Umayya's poem shows that a link between the fate of the Thamūd and the Exodus narrative (as represented by the probably authentic allusion to the Plagues of Egypt in vv. 11–13) had already been established in popular lore before the Quran – i. e., the assimilation of Biblical and native Arabian history was already under way by the time the Quran emerged.Footnote 50 Similarly, some sort of linkage between the punishment and destruction of ancient peoples like the Thamūd and hymnic affirmations of divine creation (vv. 5–10) also appears to pre-date the Quran, as remarked above.

Let us now turn to a comparison between the Thamūd passages from Umayya 34 and surah 91. The most important discrepancy, the absence of a messenger figure from the poem, has already been mentioned. According to Umayya, the Thamūd – or rather the individual Aḥmar – commit a cultic transgression: they violate a sacred animal, and their ensuing destruction is the result of a curse called down on them by the slain camel's little colt. Although according to surah 91, the action that brings about their punishment is the same – namely, the hamstringing of a camel – the Quranic retelling pictures it as an act of disobedience to an explicit command given by a divinely authorized prophet: the messenger tells them to leave the camel to drink (v. 13), but they go on to hamstring her nevertheless (v. 14a). It has been noted by Horovitz that the Quranic punishment legends display a constellation of protagonists that corresponds to the situation in which Muḥammad found himself: namely, the confrontation between a messenger commissioned by God to deliver certain commands or warnings, and his unbelieving audience who calls him a liar and refuses to obey him, and is wiped out as a consequence.Footnote 51 With regard to many Biblically inspired punishment legends, such as the stories of Noah and of Moses, this constellation already underlies previous Judaeo-Christian versions or can at least be easily projected upon them. The Arabian Thamūd tradition, however, was apparently a different case: it is reasonable to conclude that the figure of a messenger cast on the precedent of Noah appears for the first time in the Quran. Hence, although we have seen that the stories of Pharaoh and of the Thamūd had already been connected to each other before the Quran, it is only in the Quran that the Thamūd narrative comes to display the basic plot structure that is also at the heart of the other Quranic punishment legends: the constellation of a messenger facing a recalcitrant audience that is punished as a result. This is also why the Quranic version considerably downplays the importance of Aḥmar (who only appears under the general label “the wicked one”, ashqā, in v. 12): as v. 14a states, “they [that is, all of the Thamūd] called him [the messenger] a liar and hamstrung her [the camel]”. The Thamūd are thus collectively guilty of repudiating their messenger and of killing the sacred camel; the “appearance of the wicked one among them” (v. 12) only triggers their crime. There can be no doubt that this insinuation of collective guilt results in a much tighter structural correspondence between the Thamūd narrative and the other Quranic punishment legends, on the one hand, and between the Thamūd narrative and the situation of Muḥammad, on the other. A comparison of Umayya 34 and surah 91 thus affords us a valuable glimpse into how the Quran reorganizes existing narrative lore in order to harness it for the expression of its own prophetology and thereby gives additional coherence to an existing tendency – the assimilation of Biblical history and native Arabian lore.

Another striking difference between Umayya 34 and surah 91 is the fact that the Quranic version only supplies an almost laconic and decidedly undramatic outline of the basic events. Whereas Umayya's version has two climactic moments (the killing of the camel and the curse of the surviving colt), the Quranic account has none: the messenger says, “Do X”, the people disobey, they are punished – and that is the end of the matter. There are no digressive descriptions of the act of hamstringing, there is no mention of a camel colt, and the text is not concerned with clarifying how news of the events was passed on if all of the Thamūd were supposedly killed. There is thus no surplus information in the Quranic version; it is more a plot synopsis than an actual narrative, as all elements that might create some kind of suspense are omitted. The emphasis is very clearly not on narrative entertainment or literary skill as displayed by means of descriptive snapshots, as in Umayya, but rather on the general message it contains. This is already evident from the fact that the Quranic Thamūd passage follows a statement about the respective fates of the good and the wicked: “He who purifies his soul succeeds, and he who corrupts it fails” (vv. 9.10); the following story is obviously meant to serve as an illustration of, and hence is subordinate to, this general truth. That the story is seen from an ideological rather than a purely narrative perspective is also apparent from the thorough paraenetic encoding of the story: the persons and their actions are not referred to by their proper names or by elaborate descriptions, as would have been customary in ancient Arabic poetry, but rather in ethical-religious terms that unambiguously pinpoint their moral standing – the narrative opens with a condemnation of the Thamūd as having “called [their messenger] a liar”, and Aḥmar becomes merely “a wicked one among them”. Even the messenger is not named. The first time he is called Ṣāliḥ is probably in surah 26 with its long cycle of punishment legends; since there all the other messengers are named, it is clear that the Thamūdic messenger, too, has to be given a proper nameFootnote 52 – which turns out to be a highly generic one, too: “righteous one,” which may be viewed as functioning as the implicit contrary to “the wicked one”, ashqā.

4. Umayya and the Quranic milieu

The remainder of this article will attempt to extend some of the observations made so far in view of the question of what Umayya's religious poetry might teach us about the religious situation in Late Antique Arabia, and more particularly about the religious milieu from which the Quranic corpus has emerged. First, can we sketch a profile of the traditions that have fed into the Biblically inspired poetry of Umayya, and can we thus arrive at a more substantial picture of the nature and provenance of the Biblical material circulating in sixth-century Hijaz? Hirschberg has argued that there is a persistent presence of Rabbinic traditions in Umayya,Footnote 53 but caution about his results is warranted, as many of the parallels he points to could perhaps also be found in Syriac Christian sources. The fact that even in discussing a Christian poet like ʿAdī b. Zaid, Hirschberg refers almost exclusively to Rabbinic works suggests that he may not have worked through the relevant Christian works with the same diligence and that pending further study we should hesitate to view Umayya as specifically influenced by the Rabbinic tradition.Footnote 54

Let us briefly examine an example of the way Umayya recycles pre-existing traditions. According to verse 32: 25 Schulthess (“dark clouds enveloped the water”), which belongs to a fragment on the Deluge that Frank-Kamenetzky – correctly, in my view – accepts as genuine,Footnote 55 it was dark while Noah was on the Ark. As Hirschfeld observes,Footnote 56 this detail is attested already in the Ethiopic Apocalypse of Enoch, in the Rabbinic tradition (Genesis Rabbah), and also in later Ethiopic literature.Footnote 57 Whereas the Apocalypse of Enoch mentions the absence of light during the Deluge only incidentally,Footnote 58 the context in Genesis Rabbah is a critical discussion of the etymology of Noah's name that is put forward in Genesis 5: 29, where the Hebrew name Nōăḥ is connected to yĕnaḥămēnû, “he shall comfort us”. Apparently the Rabbis are dissatisfied with this explanation, as the name and the verb only partially share root consonants, and one of the alternative explanations suggested is that the name Noah reflects the fact that during the Deluge, “the planets did not function”, i.e. they rested (lānûăḥ in Hebrew), or perhaps did function but “made no impression”.Footnote 59

As this brief survey of the intertextual background to Umayya 32: 25 shows, Umayya's allusion to the darkness that prevailed during the Flood is much closer to how that particular detail appears in the Book of Enoch: it is treated simply as a narrative detail that heightens suspense rather than being endowed with an exegetical function, as in Genesis Rabbah. In view of this it is more likely that Umayya's reference to the darkness during the Flood derives from narrative traditions similar to what we find in the Book of Enoch rather than from sophisticated exegetical discussions of the sort one encounters in Genesis Rabbah, which again casts doubt on Hirschberg's emphasis on the “haggadic” background of Umayya's poetry.

It is striking that the very different functions performed by a single narrative detail in Umayya and in Genesis Rabbah is reminiscent of the very different ways, analysed above, in which the Thamūd story is used by Umayya and in the Quran: whereas Genesis Rabbah and the Quran employ narrative for the purpose of explaining the Bible or of formulating theological truths, in Umayya the very same narrative lore appears unharnessed from any exegetical or theological anchoring – probably because the respective traditions had undergone a prolonged process of oral retellingFootnote 60 and diffusion among persons more interested in their narrative value than in their usefulness for scriptural interpretation or for illustrating a novel theological message. The milieu we find documented in Umayya's poetry was therefore at once confessionally uncommitted, yet well acquainted with orally transmitted versions of Judaeo-Christian narrative lore.Footnote 61 It is a milieu where a significant amount of Biblically-based notions and narratives were in circulation and constituted a sort of freewheeling savoir sauvage that due to its origin could easily be put in the service of Biblically inspired moralizing – yet the considerable theological potential of such traditions only appears to have been re-actualized in the Quran: it is only in the Quran (as the above analysis of the Quranic retelling of the Thamūd story has tried to show in some detail) that we again find a sustained attempt to subordinate this material to a consistent theological outlook, to reharness it, as it were.

A second general remark that I would like to make about the relationship between Umayya and the Quranic milieu concerns the issue of literary format. Especially when compared to the Quran, Umayya, in spite of his treatment of Biblical subjects, comes across as very much bound to the structural conventions of ancient Arabic poetry. For example, he uses the conventional meters, and his poems exhibit single rhymes, whereas the Quran lacks metre and at least in its early stratum employs changes of rhyme patterns as an effective means to mark off different subsections of a particular surah.Footnote 62 Umayya is traditional also in the way in which he renders Biblical stories: there is a general emphasis on highly detailed description (cf. for example no. 34: 26, cited above) and an extensive use of simile and metonymy that very much ties in with the literary sensibilities that govern the rest of ancient Arabic poetry.Footnote 63

Thus, what set the Quranic texts apart from Umayya are both their ideological “tightness”, i.e. their thoroughgoing imposition of a theological moral on the freewheeling narrative lore on which they draw, and their literary innovativeness. Both aspects are bound up with a third: the Quranic texts' consistent self-stylization as divine speech through the employment of the divine voices (encapsulated both in the use of first-person pronouns and second-person addresses of the Quranic messenger and his listeners). By contrast, the claim to be based on supernatural revelation is completely absent from Umayya's poetry, whose voice is uniformly that of a poet rather than a prophet.Footnote 64 It is significant, I believe, to appreciate the intimate link between all three features: it is because the Quranic recitations both deploy a repertoire of literary forms that is substantially different from the established conventions of ancient Arabic poetry and rigidly infuse the narratives and notions they appropriate from their immediate milieu with a theological message that their insistence to derive from divine revelation could be perceived as credible by (some of) their addressees.

Arguably, if we are to explain historically the emergence of the Quran, then, it is above all these three core features – rather than the fact that the Quran, just like Umayya, uses material familiar from earlier Judaeo-Christian literature – that stand in need of some kind of historical explanation. Unfortunately, as valuable as Umayya's poetry might be, it does not appear to be very helpful in this respect. It is likely that at least with respect to the issues of the Quran's literary format and its sustained claim to derive from supernatural revelation, the oracles attributed to pre-Islamic soothsayers, the kuhhān, may prove to be more germane than ancient Arabic poetry, even poetry of the unconventional sort exemplified by Umayya.Footnote 65

Appendix: Arabic texts

Schulthess, no. 27

١ إلهُ العالَمينَ ![]() ارضٍ ورَبُّ الراسيات ِ من الجِبالِ

ارضٍ ورَبُّ الراسيات ِ من الجِبالِ

٢ بَناها وابْتَنَى سَبْعاً شِداداً بِلا عَمَدٍ يُرَيْنَ ولا رِجال

٣ وسَوّاها ![]() بنور من الشمس المُضيئَةِ والهِلال

بنور من الشمس المُضيئَةِ والهِلال

٤ ومن شُهُب ٍ تَلأْلَأُ فى دُجاها مَرا ![]() أشَدُّ من النِصال

أشَدُّ من النِصال

٥ ![]() الارضَ فانْبَجَسَت عُيوناً وأنْهارأً من العَذْب ِ الزُلال

الارضَ فانْبَجَسَت عُيوناً وأنْهارأً من العَذْب ِ الزُلال

٦ وبارَكَ فى نَوا![]() وزَ

وزَ![]() ما كان من حَرْث ٍ ومال

ما كان من حَرْث ٍ ومال

٧ فكلُّ ![]() ٍ لا

ٍ لا ![]() يَوْما ً وذى دُنْيَا يَصيرُ الى زَوال

يَوْما ً وذى دُنْيَا يَصيرُ الى زَوال

٨ ويَفْنَى بعد ![]() ويَبْلى سِوَى الباقى ا

ويَبْلى سِوَى الباقى ا![]() ذى الجَلال

ذى الجَلال

٩ وسيقَ المُجْرِمونَ وهم عُراةٌ الى ذات ِ المَقامِع والنَكال

١٠ فنادَوْا وَيْلَنا ويلاً طويلاً و![]() ا فى سَلاسِلِها الطِوال

ا فى سَلاسِلِها الطِوال

١١ فلَيْسوا ![]() فيَسْتَريحوا وكلُّهمُ ببَحْر ِ النار ِ صالى

فيَسْتَريحوا وكلُّهمُ ببَحْر ِ النار ِ صالى

١٢ ![]()

![]() بدار ِ صِدْق ٍ وعَيْش ٍ ناعِم

بدار ِ صِدْق ٍ وعَيْش ٍ ناعِم ![]() الظِلال

الظِلال

١٣ لهم ما يَشْتهون وما ![]() ا من الأَفْراح

ا من الأَفْراح ![]() والكَمال

والكَمال

Schulthess, no. 34: 23–32

٢٣ كثَمودَ التي تَفَتَّكَت الدِينَ عُتِيّاً ![]() سَقْبٍ عَقيرا

سَقْبٍ عَقيرا

٢٤ ناقة ٌ لِلإلهِ تَسْرَحُ فى الارض وتَنْتابُ حَوْلَ ماءِ مُديرا

٢٥ فأتاها أُحَيْمِرٌ كأخى السَهْم بعَضبٍ فقال كونى عَقيرا

٢٦ ![]() العُرْقوبَ والساقَ منها ومَضَى فى

العُرْقوبَ والساقَ منها ومَضَى فى ![]() مَكْسورا

مَكْسورا

٢٧ فرَأى السَقْبُ ![]() فارَقَتْه بعدَ إلْفٍ

فارَقَتْه بعدَ إلْفٍ ![]() ً وظَؤُورا

ً وظَؤُورا

٢٨ فأتَى صَخْرةً فقام عليها صَعْقة ً فى ![]() تَعْلو الصُخورا

تَعْلو الصُخورا

٢٩ فرَغَا رَغْوَةً فكانت عليهم رَغْوَةُ السَقْبِ ![]() ا تَدْميرا

ا تَدْميرا

٣٠ فأُصيِبوا إلّا الذريعةَ فاتَتْ من جَواريهُم وكانت جَرورا

٣١ سَنْفة ٌ أُرْسِلَتْ ![]() اهلَ قُرْح ِ بأن قد آمْسَوا ثُغُورا

اهلَ قُرْح ِ بأن قد آمْسَوا ثُغُورا

٣٢ فسَقَوْها بعد الحَديث فماتت وانتَهَى رَبُّنا وأوْفَى حَقيرا