1. Introduction

Tjwao is a severely endangered and highly under-researched language spoken in the western part of Zimbabwe, near the Botswanan border. Tjwao belongs to the Eastern Kalahari subgroup of the Khoe-Kwadi language family (cf. Güldemann and Vossen Reference Güldemann, Vossen, Heine and Nurse2000: 103; Phiri Reference Phiri2015)Footnote 2 and, although absent in previous phylogenic models (see e.g. Westphal Reference Westphal and Sebeok1971 and Vossen Reference Vossen1997), it is most likely closely related to the northern varieties of the “Tshwa” dialect cluster spoken in eastern Botswana, such as Hiechware (Dornan Reference Dornan1917), Gǁabak'e (Westphal Reference Westphal and Sebeok1971), and Tcire-Tcire (Chebanne Reference Chebanne, Batibo, Dikole, Lukusa and Nhlekisana2009).

Scholarly literature published on Tjwao remains sparse. However, research activities conducted by the authors of this paper have recently yielded an analysis of the Tjwao nominal system (Fehn and Phiri Reference Fehn and Phiri2017) and an examination of the tense-aspect-mood (TAM) of two verbal constructions – the hĩ and the ha grams (Andrason and Phiri Reference Andrason and Phiri2018). Current interest in the description and analysis of Tjwao takes place, paradoxically, at a moment when the future of the language is heavily threatened. Being used sporadically by no more than eight elderly speakers and lacking any sign of robust intergenerational transmission (Phiri Reference Phiri2015), Tjwao finds itself on the verge of imminent extinction.Footnote 3

The present paper aims to contribute to the documentation and analysis of the Tjwao language system, by examining one of the least understood aspects of Khoe-Kwadi grammar – interjections. Following Andrason and Dlali (Reference Andrason and Dlaliforthcoming), our research will be conducted within a prototype-driven approach to interjections. To construct our model, we draw eclectically on works presented by Felix Ameka, Damaris Nübling, and Ulrike Stange which, in our view, constitute the most compelling accounts of the interjectional category currently available in scholarship (see Ameka Reference Ameka1992a, Reference Ameka and Brown2006; Nübling Reference Nübling2001, Reference Nübling2004; Ameka and Wilkins Reference Ameka, Wilkins, Östman and Verschueren2006; Stange and Nübling Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014; Stange Reference Stange2016).

The article is organized as follows: in Section 2, we will contextualize our study by familiarizing the reader with the available literature on interjections in the Khoe-Kwadi language family, and by presenting the main tenets of the framework underlying the research. In Section 3, we will introduce the original evidence related to the meaning (pragmatic and semantic) and the form (syntax, morphology, and phonology) of interjections in Tjwao. In Section 4, this evidence will be evaluated within the adopted framework. Lastly, in Section 5, we will draw conclusions and propose avenues for further research.

2. Background

2.1. Interjections in Khoe-Kwadi

To date, the available literature on interjections in languages of the Khoe-Kwadi family remains sparse. Reasons for this dearth may be seen in the dire sociolinguistic situation affecting Kalahari Khoe-Kwadi languages: since all varieties of this subgroup have comparatively small numbers of speakers and, for the most part, can be considered endangered (Brenzinger Reference Brenzinger, Witzlack-Makarevich and Ernszt2013), linguists may have felt it more pressing to document phoneme inventories, lexicon, and morpho-syntax rather than focusing on less well-understood aspects of grammar (Widlok Reference Widlok2016). Furthermore, as canonical interjections (see Section 2.2 below) are highly context-dependent, the declining use of many Khoe-Kwadi languages in everyday conversation poses an obstacle to the successful documentation of larger corpora of naturally produced language, which are fundamental for the study of interjections.

The entire scholarly treatment of interjections in Khoe-Kwadi is limited to a short section in Kilian-Hatz's (Reference Kilian-Hatz2008) grammar of Khwe and Widlok's (Reference Widlok2016) brief discussion of selected interjections in ǂAkhoe Haiǁom. In Khwe, the class of interjections is large and highly diversified with regard to their meaning and form. This diversity is related to the varied origin of interjections and, in particular, their ability to draw from verbs and nouns (Kilian-Hatz Reference Kilian-Hatz2008: 246). The most important semantic types attested include emotions and insults, greetings, rules of conduct, routines of politeness, as well as conversations directed at animals (Kilian-Hatz Reference Kilian-Hatz2008: 247–8). Syntactically, interjections are complex utterances; cannot be negated; and occupy clause-initial and less frequently clause-final positions (Kilian-Hatz Reference Kilian-Hatz2008: 246). Morphologically, interjections are “invariable simplicia” (ibid.). Phonologically, interjections may violate rules governing the sound system of Khwe by allowing consonant clusters. They also “form their own intonation unit[s]” (ibid.). Although drawing on a large corpus, thus lending itself to a comprehensive linguistic analysis, Widlok's (Reference Widlok2016) study of interjections in ǂAkhoe Haiǁom is almost exclusively anthropological.Footnote 4 Nevertheless, in light of the examples provided, one may infer certain conclusions regarding the linguistic characteristics of the interjectional category. As far as their meaning is concerned, interjections are context-dependent: their semantic interpretation draws heavily on “the situational context in which they are uttered” (Widlok Reference Widlok2016: 140). As far as their form is concerned, the majority of interjectional lexemes attested are secondary interjections (cf. Nübling Reference Nübling2001; Ameka and Wilkins Reference Ameka, Wilkins, Östman and Verschueren2006: 4, see Section 2.2 below). This means that interjections tend to be derived from other lexical classes, specifically full lexical verbs (e.g. am ‘right, correct’) or vocative pronouns (e.g. e-tse ‘hey you’) (Widlok Reference Widlok2016: 141). The exceptions are replies to yes/no questions, which are primary interjections. Interjections may also be borrowed, being thus “multilingual” (ibid. 142). Syntactically, interjections are both “words” and “utterances” (ibid.). Phonologically, they may contain “aberrant features”, e.g. the cluster mb (ibid. 141). Lastly, interjections are typically accompanied, or even replaced, by facial expressions or bodily gestures that provide clues for relevant interpretations (ibid. 142).

Information concerning interjections in other Khoe-Kwadi languages – in particular, Standard Namibian Khoekhoe (Hagman Reference Hagman1977; Haacke and Eiseb Reference Haacke and Eiseb2002), Ts'ixa (Fehn Reference Fehn2016), and Naro (Visser Reference Visser2001) – can only be inferred from dictionary entries and sentences exemplifying other grammatical phenomena. Interjections also feature abundantly in the many Khwe texts assembled by Köhler (Reference Köhler1989, Reference Köhler1991, Reference Köhler1997, Reference Köhler2018), without receiving a systematic linguistic analysis thus far.Footnote 5

2.2. FrameworkFootnote 6

Our study is developed within a prototype-driven approach to interjections (Andrason and Dlali Reference Andrason and Dlaliforthcoming). We understand the category of interjections as a (radial) network that is organized around a prototype and contains members characterized by a distinct membership status (Janda Reference Janda2015). We define the prototype cumulatively through a set of properties related to meaning and form. In our definition, we inclusively draw on the key typological studies of interjections presented by Ameka (Reference Ameka1992a, Reference Ameka and Brown2006), Nübling (Reference Nübling2001, Reference Nübling2004), Stange and Nübling (Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014), and Stange (Reference Stange2016), who view the interjectional word class through the lens of prototypes. The adoption of prototype theory to categorization ensures that the interjectional category is both internally diversified (“flexible”) and coherent (“firm”) (cf. Janda Reference Janda2015: 137). It also has two important consequences. First, although the prototype constitutes a central concept in our approach to interjectionality, it cannot be equated with the interjectional category itself. Second, no single prototypical trait constitutes a necessary and/or sufficient condition allowing for an item to be included in the category of interjections (for details see Janda Reference Janda2015).

As far as its meaning is concerned, a prototypical interjection is emotive or sensorial – it communicates the current emotional states of speakers or their sensations, exhibiting “an ‘I feel’ component” (Stange and Nübling Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014: 1983; see also Nübling Reference Nübling2004: 20 and Stange Reference Stange2016: 18–20). It constitutes a semi-automatic instinctive response to experienced stimuli (Ameka Reference Ameka1992a: 108–9; Nübling Reference Nübling2004: 19–20; Ameka and Wilkins Reference Ameka, Wilkins, Östman and Verschueren2006: 16; Stange and Nübling Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014: 1982–3; Stange Reference Stange2016: 10, 19–20). It is non-referential and monologic – with no addressees or third parties involved (Ameka Reference Ameka1992a: 109; Nübling Reference Nübling2004: 19; Stange and Nübling Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014: 1982–3; Stange Reference Stange2016: 10–11, 13, 42). It is polysemous and multifunctional, being thus context-dependent to a considerable extent (Ameka Reference Ameka1992a: 114; Reference Ameka, Wilkins, Östman and Verschueren2006: 743; Ameka and Wilkins Reference Ameka, Wilkins, Östman and Verschueren2006: 2; Stange and Nübling Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014: 1985; Stange Reference Stange2016: 12, 41). It is accompanied by physical gestures – interjections being viewed as vocal gestures (Ameka Reference Ameka1992a: 112, Reference Ameka and Brown2006: 743; Nübling Reference Nübling2004; Ameka and Wilkins Reference Ameka, Wilkins, Östman and Verschueren2006: 3; Stange and Nübling Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014: 1982, 1986; Stange Reference Stange2016: 45).

As far as its form is concerned, a prototypical interjection is holophrastic. It constitutes a complete and non-elliptical utterance (Ameka Reference Ameka1992a: 107–8, Reference Ameka and Brown2006: 743–5; Nübling Reference Nübling2004: 20; Stange and Nübling Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014: 1982–3; Stange Reference Stange2016: 20, 48).Footnote 7 When used in a sentence,Footnote 8 it is not integrated into that sentence structure. It does not constitute a structural element projected by the predicate, nor does it modify any of the arguments and adjuncts. It also fails to be a component in constructions (Ameka Reference Ameka1992a: 112, 118; Reference Ameka and Brown2006: 743–5; Stange and Nübling Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014: 1985; Stange Reference Stange2016: 20, 48). This lack of structural integration is visible in the isolation from the remaining parts of a sentence (Ameka Reference Ameka1992a: 108; Stange and Nübling Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014: 1982) – interjections occupying an initial or a final position (Drescher Reference Drescher, Niemeier and Dirven1997; Ameka and Wilkins Reference Ameka, Wilkins, Östman and Verschueren2006: 4; Nordgren Reference Nordgren2015: 44) and constituting independent prosodic units marked by pause, intonation, and/or contouring (Ameka Reference Ameka1992a: 108, Reference Ameka and Brown2006: 745; Nübling Reference Nübling2004: 30; Nordgren Reference Nordgren2015: 38, 45; see, however, O'Connell and Kowal (Reference O'Connell and Kowal2008: 137, 139) who argue against the “articulatory isolation” of interjections).Footnote 9 The interjectional prototype is mono-morphemic, which implies its indivisibility into more fragmentary units (Ameka Reference Ameka1992a: 111, Reference Ameka and Brown2006: 743–4; Stange and Nübling Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014: 1985), and its incompatibility with inflections, derivations, and compounding (Ameka Reference Ameka1992a, Reference Ameka and Brown2006: 743; Nübling Reference Nübling2004: 29; Ameka and Wilkins Reference Ameka, Wilkins, Östman and Verschueren2006: 5; Stange and Nübling Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014: 1985; Stange Reference Stange2016: 36). It contains sounds and sound-combinations that are foreign or peripheral to the inventory of the language in which it is used (Ameka Reference Ameka1992a: 112, Reference Ameka and Brown2006: 744–5; Stange and Nübling Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014: 1982, 1985).Footnote 10 It is pronounced with greater energy and volume (Nübling Reference Nübling2004: 22; Stange Reference Stange2016: 20), and exhibits a mono-syllabic (typically vocalic) structure (Nübling Reference Nübling2004: 24–5).Footnote 11

The interjectional prototype described above is an ideal constructed in light of cross-linguistic tendencies and cognitive saliency. Interjections attested in a language may comply with that ideal to a greater or lesser degree, depending on how many prototypical features are fulfilled. The more features that are instantiated, the more canonical an interjection is – and the more central its representation in the categorial radial network. Inversely, with fewer features being met, the status of an attested interjection becomes less canonical and its place in the network more peripheral. Overall, canonical interjections are more extra-systematic, sometimes being regarded as para-linguistic or para-grammatical (Ameka Reference Ameka1992a: 112, Reference Ameka and Brown2006: 745; Stange Reference Stange2016: 6; contra Norrick Reference Norrick2009: 888). In contrast, non-canonical interjections exhibit a more systematic, and hence more genuinely linguistic or grammatical profile.

Within the radial network of the interjectional category, emotive interjections (i.e. those expressing feelings and sensations) and primary interjections (i.e. items that are exclusively used as interjections) generally occupy a central position. They tend to be the most canonical and extra-systematic (Ameka and Wilkins Reference Ameka, Wilkins, Östman and Verschueren2006: 3–4; Nübling Reference Nübling2004: 17; Stange and Nübling Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014: 1983; Stange Reference Stange2016: 6, 10–13, 18–9; Borchmann Reference Borchmann2019). Inversely, a greater number of non-canonical interjections located at the category's peripheries are found among non-emotive interjections (i.e. cognitive, conative, and phatic)Footnote 12 and secondary interjections (i.e. interjections derived from other lexical classes or expressions; Nübling Reference Nübling2001; Ameka and Wilkins Reference Ameka, Wilkins, Östman and Verschueren2006: 4). Conative and phatic interjections violate several meaning-related properties. For instance, they tend to be deliberate and dialogical. They are produced purposefully and involve addressees.Footnote 13 In turn, secondary interjections violate various formal features. They are pluri-morphemic, exhibit inflections and derivations, consist of several syllables, and do not contain aberrant sounds or sound combinations. Overall, secondary phatic interjections are viewed as the least canonical (Stange Reference Stange2016: 18).Footnote 14

3. Evidence

The evidence presented in this paper draws on fieldwork conducted in Tsholotsho (Zimbabwe) in November 2018. The data collected reflects the language use of ten informants – the only competent and fluent native speakers of Tjwao (Phiri Reference Phiri2015, Andrason and Phiri Reference Andrason and Phiri2018: 270).Footnote 15 The larger part of the collected interjections was elicited. The elicitation involved one of the following three methods: (a) speakers linguistically expressed emotions and sensations that could be easily identified on images presented to them; (b) speakers constructed or completed sentences the use of which constituted a necessary part of an improvised situation; (c) speakers translated Ndebele sentences containing interjections in prototypical contexts of use. Additionally, a number of tokens were extracted from spontaneous discourses and oral narratives. In total, 42 different interjections were collected, and their usage thoroughly documented through a variety of contextualized examples.

3.1. The meaning of interjections in Tjwao

Tjwao exhibits the four main classes of interjections: emotive, cognitive, conative, and phatic. The largest number of interjections collected in our fieldwork (20) belong to the emotive type: a-a, ãã-ã, ã-ã, a-nǁa, ccc, e-e, ehe, eyi, hll, i-ii, mm, oo, pff, ss, xuu, wu-wu-wu, yaa, yee, yeyi, and yii.Footnote 16 Emotive interjections communicate the emotional states of speakers, in particular their feelings or sensations. These two sub-types of emotive interjections are attested in the Tjwao language. The feelings conveyed by emotive interjections can be positive or negative. Examples of positive feelings encoded by interjections are: happiness and excitement (e.g. yee in 1a), admiration (yeyi in 1b), relief (xuu), and approval (ehe).

A wide range of emotive interjections express negative feelings, such as: annoyance or irritation (e.g. ãã-ã in 2a), repugnance (oo and wu-wu-wu in 2b), fear or anxiety (yii in 2c), anger (a-nǁa and e-e in 2d), contempt (ã-ã and a-nǁa), sadness (mm and yee in 2e), and disapproval (ã-ã).

The interjection a-a expresses surprise that, depending on context, may constitute a negative, positive, or emotionally neutral experience:

Emotive interjections may also refer to sensations experienced by speakers. Typical sensations encoded by interjections in Tjwao are the experiences of tiredness (xuu in 4a), physical pain (ss and i-ii in 4b), bad odour (pff in 4c), and heat (eyi in 4d), as well as those of cold (ccc) and good taste or smell (hll).

Cognitive interjections found in Tjwao concern mental states. The most common cognitive processes encoded by interjections involve knowing (yaa in 5a) or inversely not knowing (hii-i in 5b), understanding (woo in 5c), remembering (aha in 5d), and doubting (eh).

Conative interjections are another prolific class of interjections in Tjwao, and are represented by ten lexemes: kip-kip-kip, kiti-kiti-kiti, mbh-mbh-mbh, psi-psi-psi, c, tee, tsua(-tsua), yii, ǃ-ǃ-ǃ, ǀ-ǀ-ǀ, and a whistle. Three sub-types of conative interjections may be distinguished. First, conative interjections are employed to draw the attention of other persons. The most typical attention getters in Tjwao are yii and yeyi:

Second, conative interjections are used as commands. They are directed to other persons with the aim of prompting a specific reaction on their part. For instance, the interjection c in (7a) is employed to request silence, whereas yeyi in (7b) is employed to urge a person passing by to come closer.

Third, conative interjections are directed to animals to incite them to perform a specific action. For instance, by means of the interjection tsua (typically uttered in sequences of two tsua-tsua), the speaker urges cattle and donkeys to start moving forward or to continue going further (8). In contrast, the interjection tee is used to stop the motion of larger animals. Usually, different types of animals necessitate the use of different interjections. For example, mbh-mbh-mbh is employed with cattle and donkeys; ǃ-ǃ-ǃ and kip-kip-kip with chickens, psi-psi-psi and kiti-kiti-kiti with cats, and ǀ-ǀ-ǀ with puppies. Adult dogs are usually called by a characteristic whistle.

The last semantic class of interjections found, the phatic type, is also well represented in Tjwao, containing the following lexemes: ã-ã, ehe, hm, kaa-ta, ti kua tcaru, ti kua ʔabu, toa/tca/ca dzee-ha e, toa/tca/ca tan-a-ha e, yaa, and ʔam. However, as will be explained in Section 3.2, only four of these items are primary interjections (i.e. ã-ã, ehe, hm, and yaa). The remaining phatic interjections are secondary, being derived from other word classes or complex constructions. As is true across languages, phatic interjections are used in Tjwao to express the speaker's attitude “towards the on-going discourse” (Ameka Reference Ameka1992a: 114, Reference Ameka1992b, Reference Ameka and Brown2006: 744) by establishing, maintaining, and interrupting communication, or by deciding what information enters and what information does not enter into the conversation. The two most common interjections used to open and terminate the communicative channel are grammaticalized routines employed in greetings (i.e. toa dzee-ha e? ‘good day’) and leave-taking (i.e. kãĩ-se kau ‘goodbye’) respectively. Similar interjectional routines are employed for the purpose of thanking (ti kua ʔabu / ʔam ‘thanks’) and apologizing (ti kua tcaru ‘sorry’). The maintenance of the communicative channel is achieved by means of hm, functionally equivalent to ‘yes, I am listening’. The interjections filtering information determining its inclusion or exclusion from the conversation are ehe, yaa, and ʔam expressing agreement (9a), and ã-ã and kaa-ta expressing disagreement (9b). The same interjections are also used as response forms equivalent to ‘yes’ (ehe, yaa, ʔam) and ‘no’ (ã-ã, kaa-ta) (9c).

Emotive interjections, whether expressing feelings or sensations, tend to constitute semi-automatic, spontaneous, and unplanned verbal reflexes. They are often produced as immediate reactions to linguistic and/or extra-linguistic stimuli. These types of interjections are not intended to induce verbal or non-verbal responses from the other participants as they are in principle monologic and lack addressees. For instance, in (10a), a man touches a hot kettle. In reaction to the sudden experience of a pain burning his hand, he produces a non-deliberate reflex-like cry. In (10b), the speaker experiences the biting cold passing through his body. Immediately and with no intention to engage in a conversation with someone else, he produces the interjection ccc. Indeed, no other persons participate in the event, the interjection being employed reflexively. Example (10c) is produced during a meeting. Unexpectedly, a person arrives. To express his surprise, one of the attendees spontaneously utters the interjection a-a. Even though other persons are involved in the event, as they participate in the meeting, the interjection is not addressed to them, but rather is used as an outlet for the amazement experienced subjectively by the speaker. In any case, no response was prompted by its use.

In contrast to emotive interjections, conative and phatic interjections are often intentional. In (11a), the speaker utters the interjection yii to draw the attention of a boy that stands further away. Its use is fully deliberate. In a similar vein, in (11b), the speaker wants a cat to come closer. For that reason, he purposefully uses the interjection psi-psi-psi.

Generally, interjections in Tjwao are non-referential. That is, they disallow discourses about third parties. They cannot be used to describe properties of the other participants in the situation (i.e. participants different from the speaker her/himself) or the activities in which those participants are engaged. For example, in (12), the interjection xuu expresses the speaker's experience of tiredness and cannot be used to denote similar emotions or sensations experienced by others. Therefore, the use of the 1st person pronoun, referring explicitly to the speaker himself, is not necessary. The inherent reflexivity of the interjection makes it clear that the person that is tired is the speaker. Similarly, the interjections oo and a-nǁa express the feelings of repugnance and anger as experienced subjectively by the speaker. Both interjections cannot be employed to describe what the other persons involved in the event may feel.

However, interjections – even the emotive ones – may have a minor referential component in Tjwao. That is, they can refer to the properties of objects, creatures, or events that cause the determined feelings and sensations as experienced by the speaker (compare with the same observation made by Stange Reference Stange2016). For example, in (13), the interjection hll is used by the speaker to express his positive experience when savouring food. However, the same lexeme also indicates that the food is tasty and good. As a result, hll refers to both the speaker's experience and the properties of the object by which that experience is prompted.

The meaning of various interjections, especially emotive and cognitive ones, relies heavily on their context of use, in particular the extralinguistic situation in which they occur, and the conversational inferences drawn. Given this context-dependency, some interjections are highly polysemous and exhibit a wide range of semantic potential. For example, the interjection yee is able to express positive emotions such as happiness (14a) or excitement (see (1a) above), as well as negative emotions such as sadness (14b; see also (2e)).Footnote 18 Similarly, ss connotes pain on the one hand (15a), and spiciness and bad taste on the other (15b); xuu expresses not only tiredness (see 12 above), but also dissatisfaction, disappointment, and relief.

In contrast to emotive and cognitive interjections, the semantic potential of phatic and conative interjections is much more constrained. Several interjective routines exclusively serve a single function, i.e. welcoming (toa dzee-ha e), leave-taking (kãĩ-se kau), thanking (ti kua ʔabu), or apologizing (ti kua tcaru). Similarly, conative interjections are typically used to request a specific type of activity, being moreover directed to a well-determined type of addressee, e.g. cattle (mbh-mbh-mbh), cat (kiti-kiti-kiti), or fowl (ǃ-ǃ-ǃ). Hardly, if ever, may the use of such interjections be extended to other contexts and semantic domains.

In some cases, the broad semantic potential of an interjection allows it to be included in more than one major interjectional type. For instance, yii may function as an emotive interjection communicating fear and anxiety, as well as a conative interjection used to draw attention, or to request a person to come closer.

Interjections in Tjwao are related to gestures. First, interjections tend to be accompanied by expressive body movements, typically hand gestures and facial expressions. For instance, the interjection of doubt eh (16a) is often complemented by raising one's eyebrows. The interjection ccc (16b) is complemented by the speaker embracing himself and performing a shaking movement. The interjectional routine ti kua tcaru (16c) is complemented by a clap of hands. The response words ehe, yaa, and ʔam ‘yes’ as well as kaa-ta and ã-ã ‘no’ are regularly accompanied by vertical or horizontal head movements, respectively.

Second, being equivalent to physical gestures, interjections may be entirely replaced by body movements. For example, in (16a) and (16b), the two gestures explained above may substitute the interjections eh and ccc, respectively, without any substantial loss of information. Nevertheless, the use of interjections without gestures is also widely attested.

3.2. The form of interjections in Tjwao

All interjections collected in our fieldwork, irrespective of their meaning and form, can function holophrastically. That is, they may constitute complete self-contained utterances and therefore be used in a conversation instead of fully-fledged canonical sentences. This will be illustrated below by several situations witnessed during data collection activities.

When listening to a person repeating the same story, a Tjwao speaker utters the emotive interjection ãã-ã to give an outlet to his feeling of annoyance. This interjection is employed independently as a self-standing utterance – it is not accompanied by any other word or sentence. Another example concerns the emotive interjection hll. This interjection is regularly used without complementary clausal or sentential elements to communicate satisfaction with the taste of good food. With conative lexemes, the holophrasticity of interjections and their independence are even more common. For instance, c is virtually always produced on its own, with no additional elements. In such cases, it is fully equivalent to a canonical imperative ngoo ‘be quiet!’.Footnote 19 In a similar vein, all conative interjections addressed to animals – e.g. ǃ-ǃ-ǃ used with fowl and ǀ-ǀ-ǀ used with dogs – function as self-standing utterances. They tend to be employed without any additional words or clauses accompanying them. The phatic filler hm typically appears on its own indicating ‘yes, I am still listening’. The interjectional response words conveying affirmation (ehe, yaa, and ʔam) and negation (ã-ã and kaa-ta) are also mostly used holophrastically. Lastly, routines featuring in greetings, leave-taking, thanking, and apologizing are small clauses or small sentences themselves, their utterance-like function being therefore evident and, in fact, tautological.Footnote 20

The most evident cases of the holophrastic use of interjections are found in dialogues in which each turn is composed exclusively of an interjection, as in (17) below. The conversation begins with person A seeing person B. A calls B, using the attention getter yii. Hearing this, B expresses his surprise by means of the emotive interjection a-a. Subsequently, A produces the interjection yee to make his excitement and happiness clear. Speaker B experiences the same feeling and expresses this by means of ehe.

All emotive, cognitive, and conative interjections collected in our fieldwork are non-elliptical. That is, they are not shortened versions of longer utterances or more elaborated constructions. For instance, in (18a), the interjection mm expressing sadness experienced by the speaker due to the loss of a relative does not constitute an abbreviated variant of a more complex expression. Similarly, the interjection ehe expressing approval and excitement in (18b) is not a modification of a more elaborate structure.

The non-elliptical character of phatic interjections requires a more nuanced discussion. To begin with, all phatic routines such as ti kua tcaru, ti kua ʔabu, toa dzee-ha e, and toa tan-a-ha e are complete clauses. They are thus not abbreviated by definition. However, it is likely that as their grammaticalization continues, some parts will be eliminated due to phonological and morphological reductions concomitant to grammaticalization (Nübling Reference Nübling2001; Hopper and Traugott Reference Hopper and Traugott2003).Footnote 21 Consequently, at later stages, the above-mentioned routines may indeed become shortened versions of complex constructions. More grammaticalized versions of input clause-like expressions may already be observed in the interjections kaa-ta and ʔam. Kaa-ta is derived from the verbal base kaa ‘want’ negated by means of the imperfective negator ta. ʔam is derived from the base ʔam ‘agree’. Due to the various processes involved in grammaticalization, these two input constructions have likely shrunk to their present forms, eliminating pronouns and other types of markings.

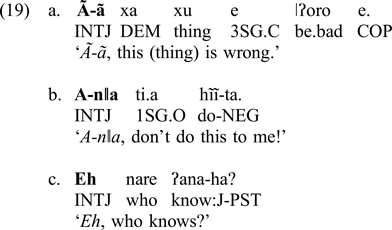

Although interjections in Tjwao may always be used independently as self-standing non-elliptical utterances, they may also form parts of larger sentences. This is evident in most examples introduced in Section 3.1 above, in which interjections indeed feature as components of complex utterances. In such cases, however, interjections tend to maintain their syntactic independence. First, interjections fail to be integrated into a clausal structure. They are not governed by the verb and do not constitute an “integral part” of the clause and its formative segments (cf. Stange and Nübling Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014: 1985). They cannot be used as arguments or adjuncts, nor do they modify the arguments and adjuncts already employed. Furthermore, although interjections may appear in declarative affirmative (19a) and negative (19b) sentences, as well as in imperative (19b) and interrogative (19c) sentences, they preserve their own illocutionary status and are not negated, questioned, or turned into imperatives. Overall, interjections are unaffected by syntactic operations of negation and interrogation.

Second, interjections do not enter into constructions with other grammatical elements, in particular other lexical classes. They do not govern complements nor are they parts of more complex phrases in which they would be governed by other entities. The only potential exceptions are cases in which interjections form coherent units with vocative nouns (20).

In Tjwao, interjections tend to appear at the boundaries of speech. In nearly all examples where interjections are used as parts of larger sentences, they occupy a sentence-initial position. For instance, in (21a), the interjection ãã-ã constitutes the first element in the sentence, itself placed at the beginning of a turn. In (21b), the interjection oo is found within a longer monologue. Even though it does not open a turn, but rather constitutes a subsequent slot in it, this interjection occupies a sentence-initial position. Interjections may also appear at the end of a turn or in a sentence-final position (21c). This is, however, uncommon. The extremely sporadic cases in which interjections appear sentence-internally emerge when vocative phrases are used at the end of a sentence. In such instances, the interjection is placed between the core clause and the vocative noun (21d). The use of interjections in other types of sentence-internal position seems to be ungrammatical in Tjwao.

Irrespective of their sentential position, interjections are typically pronounced in isolation from the other parts of the sentence. They tend to constitute independent intonation units, separated from all the other sentential components by pause or comma intonation (22a-b). Again, the common exceptions are vocatives, which often resist phonological separation from interjections. Instead, the whole vocative phrase composed of the interjection and the vocative is separated from the rest of the sentence by an audible pause (22c).

As far as their morphology is concerned, the majority of Tjwao interjections exhibit a simple, mono-morphemic structure. That is, interjections such as a-a, ãã-ã, ã-ã, aha, a-nǁa, c, ccc, e-e, eh, ehe, eyi, hii-i, hll, hm, i-ii, mm, oo, pff, ss, xuu, woo, yaa, yee, yeyi, and yii cannot be fragmentized into smaller meaningful components. Some interjections – all of them belonging to a conative type – apparently exhibit a more complex structure. The interjections kip-kip-kip, kiti-kiti-kiti, mbh-mbh-mbh, psi-psi-psi, ǃ-ǃ-ǃ, and ǀ-ǀ-ǀ are regularly produced as multiplicative patterns composed of three identical segments. However, as they cannot be realized as mono-segmental units (i.e. as kip, kiti, mbh, psi, !, and ǀ), their morphological complexity seems to be precluded. That is, in each case, the multiplication would be phonetic rather than morphological (derivative) as is typical of interjections across languages (Nübling Reference Nübling2004). It should, however, be noted that speakers do have access to the elementary segments of those interjections since each triplet may be expanded to four, five, six or any larger number of segments. Nevertheless, as was the case for tri-segmental uses, multiplication found in sequences composed of more than three segments has no morphological (derivative) function. Lastly, the interjections tsua(-tsua), tee, and ʔam that are homophonous with verbal bases – either native or borrowed from Bantu – meaning ‘come’, ‘stand, stay, stop’, and ‘agree’, respectively, are also mono-morphemic.Footnote 22

Crucially, none of the above-mentioned interjections carry any type of inflectional or derivational affixes available in Tjwao, nor do they exploit mechanisms of compounding, thus containing non-interjectional elements donated by other lexical classes. For instance, whether addressed to one person, two persons, or a group of persons, conative interjections c and yii are not inflected in singular, dual or plural, as is possible for pronouns, nouns (including vocatives), and verbs (e.g. in imperative) in Tjwao.

Contrary to the interjections analysed above, which typically belong to the emotive, cognitive, and conative types, several phatic interjectional lexemes or constructions exhibit a complex internal structure. They are composed of a number of inflectional and derivational morphemes, as well as verbal bases, pronouns, and adverbs. However, this internal complexity is not the property of the interjections themselves, but rather stems from their diachronic foundation. That is, although grammaticalized into interjectional routines, they derive from small clauses that contain(ed) separate words marked by inflections and derivations. For example, the interjection toa/tca/ca dzee-ha e used as a welcoming routine originates from a small clause built around a number of elements: the 2nd person pronoun, either formal toa or informal tca/ca; the verbal base dzee ‘pass the day’ inflected in the so-called ha gram, which is marked by the suffix -ha (Andrason and Phiri Reference Andrason and Phiri2018); and the question marker e. A similar structure is exhibited by the interjection toa/tca/ca tan-a-ha e employed in greetings before noon. The only difference is that the base tan- ‘get up’ is used and that the juncture exhibits the form a. Similarly, the interjection of leave-taking kãĩ-se kau contains the adverbial morpheme -se (kãĩ-se ‘well’ from kãĩ ‘good’), while the interjections of apologizing ti kua tcaru and thanking ti kua ʔabu / ʔam exhibit the imperfective morpheme kua. These last two interjections also contain the personal pronoun of the 1st person singular ti.

The above discussion demonstrates that although some interjections have emerged as reflexes and have thus functioned as primary interjections from the beginning of their grammatical life, others are secondary interjections, having evolved from non-interjectional lexical classes and/or constructions. The vast majority of interjections attested in our fieldwork are reflex-like primary interjections: a-a, ãã-ã, ã-ã, aha, a-nǁa, c, ccc, e-e, eh, ehe, eyi, hii-i, hll, hm, i-ii, oo, pff, ss, xuu, woo, yaa, yee, yeyi, yii, wu-wu-wu, kip-kip-kip, kiti-kiti-kiti, mbh-mbh-mbh, psi-psi-psi, ǃ-ǃ-ǃ, and ǀ-ǀ-ǀ. In contrast, the number of (more or less grammaticalized) interjections that are derived from non-interjectional lexical classes or more complex constructions is lower. This non-interjectional origin is patent in various phatic routines which, as explained above, still preserve their clausal structure: toa/tca/ca dzee-ha e lit. ‘have you spent the day (well)?’, toa/tca/ca tan-a-ha e lit. ‘have you gotten up (well)?’, kãĩ-se kau lit. ‘stay well!’, ti kua ʔabu / ʔam lit. ‘I thank you’, and ti kua tcaru lit. ‘I am sorry / I apologize’. The interjection tee most likely derives from the base tee ‘to stand, stay, stop’ used as an imperative. In this case too, no morphological or phonological reduction processes seem to have operated and the link between the interjection and its lexical source is easily recoverable. In contrast, in case of the interjections kaa-ta and ʔam, access to the original structures is no longer available due to the highly advanced extent of their interjectionalization and grammaticalization. As stated above kaa-ta consists of the verbal base kaa ‘want’ and the negative imperfective suffix -ta. It most likely derives from a small clause signifying ‘I don't want’. During the evolution of this initial expression into the lexeme ‘no’, the 1st person pronoun has been lost. The morphological reduction experienced by ʔam is even greater. This interjection arguably derives from an expression ‘I agree’, ‘I've agreed’, or similar. In this case, both the pronoun and the TAM marker have been eliminated, the form being reduced to the verbal base ‘agree’.

Additionally, at least one interjection, tsua(-tsua) constitutes an uncontested case of borrowing, being adapted from the Southern Bantu imperative tswa ‘go, come (from)’ present in Tswana and Sesotho (see also Sepedi tšwa ‘go (out), come (out)’). It is possible to find more similarities between interjections in Tjwao and Southern Bantu, especially as far as the primary (usually emotive) type is concerned. The interjection ehe, expressing approval and agreement, is almost identical to êhêê which is used in Tswana with the same function (Cole Reference Cole1955: 394). It is also similar to the interjections of approval and agreement ee and heéi in (Western) Shona (Fortune Reference Fortune1955: 431; Fivaz Reference Fivaz1970: 166; Wentzel Reference Wenztel1961: 254) and e in Kalanga (Louw Reference Louw1915: 98). The Tjwao interjection of surprise a-a coincides with an analogous lexeme in Western Shona (Wentzel Reference Wenztel1961: 254; see also Tswana a; Cole Reference Cole1955: 395). The interjections yaa, yee, yeyi, and yii are comparable to Tswana (i)ja (Cole Reference Cole1955: 395) as well as, albeit to a lesser extent, to ayi and ai in Western Shona and Kalanga (Louw Reference Louw1915: 98; Wentzel Reference Wenztel1961: 254) – all of which, like their Tjwao counterparts, express distress, sympathy, excitement, admiration, and/or surprise. Further, more or less accurate, correspondences are interjections communicating repugnance and contempt (Tjwao oo vs. Tswana ô and ôii), pain (Tjwao ss vs. Tswana ušš and išš (Cole Reference Cole1955: 395)) and Kalanga shu (Louw Reference Louw1915: 99),Footnote 23 and cold (Tjwao ccc vs. Tswana tshi (Cole Reference Cole1955: 395)) and Kalanga isha (Marconnès Reference Marconnès1931: 231). The conative interjection used to call fowl is also relatively similar in Tjwao (ǃ-ǃ-ǃ) and Tswana (q-q-q-q) (ibid. 396). In most cases of such Tjwao-Bantu co-occurrence, it is difficult to demonstrate clearly that a transfer from Bantu to Tjwao has taken place. Given the reflex-like nature of interjections, their biological foundation, and psychological primacy (O'Connell et al. Reference O'Connell, Kowal and Ageneau2005: 153), interjections may not only be culture-specific but also universal (Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Hougaard and Levisen2019: 3).Footnote 24 Therefore, the similarities between Tjwao and Bantu interjections need not be attributed to areal spread. They may equally be due to spontaneous separate developments. Tjwao interjections also reveal some similarity with interjections in Khwe. To be exact, Khwe èhé used in replies to greetings as well as to express acknowledgement (Kilian-Hatz Reference Kilian-Hatz2003: 44; Reference Kilian-Hatz2008: 247) approximates ehe in Tjwao; yɛ´, which expresses a wide range of emotions (Kilian-Hatz Reference Kilian-Hatz2008: 247) approximates yee, yeyi, and yii; à ɛ´ approximates a-a, both interjections expressing surprise (ibid.); and ã́ ã̀ used to communicate disapproval and disagreement is almost identical to ã-ã employed in the same function (ibid. 246). Again, the similarities may be genetic, areal, or merely coincidental.

The majority of the interjections collected in our fieldwork do not involve sounds that are absent from the phonological or phonetic inventory of the Tjwao language. The few – noticeable – exceptions are the interjections hm, ss, ǃ-ǃ-ǃ, hll, and mbh-mbh-mbh. The interjection hm makes use of a low sound pronounced with the mouth closed and the airstream being released through the nose, possibly transcribed as [hm̩ˀ] or [m̥m̩ˀ]. It approximates the pronunciation of functionally equivalent lexemes signalling the maintenance of the communicative channel, found in Indo-European languages, e.g. hm in English, Spanish, or Polish. The consonants [s] and [ɬ] found in the interjections ss and hll contravene the rules of the Tjwao sound system by being pronounced ingressively, i.e. as [sː↓] and [ɬː↓] respectively. The interjections ǃ-ǃ-ǃ and mbh-mbh-mbh are built around click sounds that otherwise do not belong to the standard phonemic inventory of Tjwao, namely the alveolar click [!] and the bilabial click [ʘ].Footnote 25 The conative whistle used to call dogs is perhaps the most extra-systematic from a phonological perspective.

The sound combinations, e.g. consonant clusters and syllable structures, found in interjections often respect the phonotactic principles operating in Tjwao. Again, certain important anomalies can be observed. First, contrary to the lexical classes of nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs, interjections are the only fully-fledged words that tolerate vowel-less structures. Eight interjections exhibit consonantal nuclei: either a lateral (hll), a fricative (pff, ss, c, ccc), a nasal (mm), or a click (ǃ-ǃ-ǃ, ǀ-ǀ-ǀ). Second, consonants used in interjections may be long and extra-long (see hll, pff, ss, ccc) – a rare phenomenon in Tjwao. Third, in interjections, vowels are not only short (eh, ã-ã, yeyi, eyi) and long (oo, ãã-ã, xuu, yee, yii)Footnote 26 – which is typical of all the remaining lexical classes – but may additionally be lengthened to an exaggerated duration of three or more morae. For instance, the interjection expressing repugnance oo [oː] is often extended to a three-moraic, or even four-moraic, pronunciation [oːː(ː)].

Vowels play, in general, a significant role in interjections in Tjwao. First, although not asystematic per se, interjections exhibit a remarkable tendency to use vowels in a word-initial position. That is, most interjections begin with a vowel (a-a, ãã-ã, ã-ã, aha, a-nǁa, e-e, eh, ehe, eyi, i-ii, oo) or a semi-vowel (woo, wu-wu-wu, yaa, yee, yeyi, yii). Second, some interjections are composed only of vowels, or vowels and semi-vowels (a-a, ãã-ã, ã-ã, e-e, eyi, i-ii, oo, woo, wu-wu-wu, yaa, yee, yeyi, yii). This vocalic nature is especially patent in emotive interjections of which only five (pff, ss, ccc, hll, xuu) have a genuine consonant as their first (and typically only) phonetic element. The remaining fourteen emotive interjections start with a vowel or a semi-vowel. In contrast, conative interjections tend to begin with a consonant.

Primary interjections tend to be monosyllabic and bisyllabic. The bisyllabic interjections usually exhibit harmonious patterns. These may involve: the reduplication of a vowel (a-a, ãã-ã, ã-ã, e-e, i-ii),Footnote 27 vocalic harmony in the first and second syllable (aha, a-nǁa, ehe), the multiplication of a syllable whether vocalic or non-vocalic (mbh-mbh-mbh, wu-wu-wu, kip-kip-kip, ǃ-ǃ-ǃ, ǀ-ǀ-ǀ, kiti-kiti-kiti), as well as the repetition of a glide or, alternatively, the imprecise reduplication of a syllable (yeyi). Primary interjections consisting of more than two syllables that would not result from multiplication are absent in Tjwao.

All the anomalies described above only characterize primary interjections. Secondary interjections such as toa dzee-ha e, toa/tca/ca tan-a-ha e, kãĩ-se kau, ti kua ʔabu / ʔam, and ti kua tcaru exhibit fully regular phonological profiles. This is also true of those secondary interjections that have been profoundly interjectionalized and grammaticalized, e.g. kaa-ta, ʔam, tee, as well as the interjection tsua(-tsua)Footnote 28 adapted from a Southern Bantu (Tswana) imperative.

Interjections – whether primary or secondary – invariably bear accent. Some of them tend to be uttered with greater energy and louder volume. This is typical of emotive interjections, the attention getter yii, and conative interjections requesting motion (tsua(-tsua)) or its cessation (tee). By contrast, a more expressive and louder pronunciation is unusual with the other conative interjections used to attract animals (kip-kip-kip, kiti-kiti-kiti, mbh-mbh-mbh, psi-psi-psi, ǃ-ǃ-ǃ, ǀ-ǀ-ǀ) and with the majority of phatic interjections (e.g. hm).

4. Results and discussion

The evidence presented in the previous section reveals a considerable internal diversity in the category of interjections in Tjwao.

As far as their meaning is concerned – in the realm of both semantics and pragmatics – Tjwao interjections may, although need not, comply with the typological prototype. From a semantic perspective, as expected, interjections can express emotional and sensorial states. However, their semantic interjectionality may also be lower, interjections being used to indicate the state of knowledge, draw attention, express wishes, establish, maintain or interrupt communication, and perform various routines. For each main interjectional type – emotive, cognitive, conative, and phatic – the various sub-types common across languages are also attested. From a pragmatic perspective, interjections are often semi-automatic, spontaneous, and unplanned, constituting immediate reflexes to linguistic and extra-linguistic stimuli. Some may, however, be produced deliberately. A number of interjections are monologic, thus lacking addressees. Nonetheless, some are dialogical, being produced to respond to other participants’ utterances or trigger determined responses on the part of interlocutors. Interjections are most frequently used in a non-referential manner, even though some can exhibit a minor referential component. The meaning of various interjections relies heavily upon context, which renders them highly polysemous. Contrary to this tendency, several interjections can be monosemous and characterized by restricted contexts of use. Lastly, interjections are often accompanied by gestures, and can even be replaced by body movements. However, this is not universal and gesture-free interjections are also widely attested.

Similarly, as far as their form is concerned – whether in the realm of syntax, morphology, or phonetics – interjections oscillate between compliance with the typological prototype and the violation thereof. From a syntactic perspective, interjections can function holophrastically, forming complete self-contained utterances. Such utterance-interjections are not usually elliptical. However, in the cases of a few interjections that derive from complex constructions, certain components present in original sequences have been eliminated due to the process of a phonological, morphological, and syntactic erosion typical of grammaticalization. While holophrasticity is always grammatical, interjections may also form parts of larger sentences. In such cases, they generally maintain their syntactic independence. They are not governed by the predicate, cannot function as arguments or adjuncts, and do not modify other elements in the sentence. They do not participate in syntactic operations and have no bearing on the illocutionary force of the adjacent part of the sentence. Furthermore, interjections do not enter into constructions, with the exception of vocatives. Interjections appear at the boundaries of speech, occupying a sentence-initial position or, significantly less often, a sentence-final position. Their sentence-internal usage is infrequent, being confined to uses with vocatives. Interjections tend to be phonetically isolated from the rest of the sentence, thus constituting a separated intonation unit regularly marked by a pause. Vocatives are, again, a noticeable exception, as they often form conjunctive intonational units with interjections. From a morphological perspective, most interjections exhibit a simple mono-morphemic structure, although more complex, i.e. multiplicated, structures, are also possible. Nevertheless, in multiplicated interjections, multiplication only plays a phonetic function rather than a morphological one. Interjections do not carry inflectional or derivational affixes, nor do they exploit mechanisms of compounding. The only interjections that exhibit a complex internal structure, being composed of inflectional and derivational morphemes, as well as lexically transparent bases, are those derived from constructions and small clauses. In such cases, morphology is not the property of an interjection itself but rather reflects the morphology of the components that built up the original construction or clause. From a phonetic perspective, interjections may involve extra-systematic sounds, specifically: the ingressive sounds [sː↓] and [ɬː↓], the click sounds [!] and [ʘ], the sound [hm̩]/[m̥m̩], and the whistle. However, many other interjections are fully systematic as far as their vowels and consonants are concerned. Various phonotactic properties of interjections are systematic with a few important anomalies, in particular the presence of vowel-less structures, long consonants, and exaggeratedly long vowels. Overall, vocalic elements play a prominent role in interjections, with a general tendency for vowels to appear word-initially. A number of interjections are mono- or bisyllabic. However, longer interjections are also attested. Bisyllabic interjections often exhibit harmonious patterns. Interjections invariably bear stress. They are often accompanied by greater energy and louder volume although this is, again, not universal.

In our view, the category of interjections in Tjwao described in this article can only be comprehended and explained in its entirety by the radial model, which stands in agreement with the prototype-driven proposals formulated by Ameka (Reference Ameka1992a; Reference Ameka and Brown2006), Nübling (Reference Nübling2001, Reference Nübling2004), Stange and Nübling (Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014) and Stange (Reference Stange2016). The use of this model ensures the maintenance of the internal diversity of the category on the one hand, and the recognition of its coherence on the other. In the centre of the interjectional category in Tjwao one finds canonical interjections that comply with the typological prototype fully, both in terms of their meaning and form (e.g. hll [ɬː↓], ss [sː↓] and oo when pronounced with an exaggerated length, i.e. [oːːː]). In contrast, the peripheral zone of the category is occupied by non-canonical interjections that comply with the prototype minimally (e.g. toa dzee-ha e, toa tan-a-ha e, and kãĩ-se kau). Many other interjections are located in the intermediate areas of the categorial network, that is between the canonical centre and the non-canonical periphery. Overall, in Tjwao, belonging to the category of interjections is not a binary question of either/or but rather a matter of degree – some members being more interjectional than others. The most canonical and thus central members of the interjectional category in Tjwao are emotive primary interjections. They are also the most extra-systematic, distinguishing themselves most clearly from other lexical classes found in the Tjwao language. The least canonical and thus the most peripheral are secondary phatic interjections. They are the least extra-systematic and approximate other lexical classes more closely.

The results of our study enable us to compare the category of interjections in Tjwao with similar categories in other Khoe-Kwadi languages for which at least basic descriptions exist, i.e. Khwe (Kilian-Hatz Reference Kilian-Hatz2003, Reference Kilian-Hatz2008) and ǂAkhoe Haiǁom (Widlok Reference Widlok2016). In the three languages, the interjectional categories are highly diversified as far as their meaning and form are concerned, and the semantic interpretations of their members are heavily context-dependent. Syntactically, Khoe-Kwadi interjections may function as complete utterances; cannot be negated; and usually occupy a clause-initial position. Morphologically, they are invariable and simple. Phonologically, they may exhibit aberrant sounds and sound combinations. They are also strongly correlated with gestures. However, contrary to ǂAkhoe Haiǁom (Widlok Reference Widlok2016), the number of primary interjections in Tjwao is larger than that of secondary interjections derived from non-interjectional lexical classes/constructions through interjectionalization.

Our research not only confirms several propositions related to the synchronic structure of an interjectional category in Tjwao and in related languages – it also corroborates certain typological diachronic hypotheses. Most importantly, in agreement with observations made by typologists (Ameka Reference Ameka1992a, Reference Ameka and Brown2006; Nübling Reference Nübling2001, Reference Nübling2004; Stange and Nübling Reference Stange, Nübling, Müller, Fricke, Cienki and McNeill2014; Stange Reference Stange2016), interjections in Tjwao derive from three types of sources: (a) reflexes that yield primary interjections directly; (b) constructions that draw on other lexical classes and that through interjectionalization initially yield secondary interjections and, if the process continues, primary interjections; and (c) lexemes borrowed from other languages. These manners of the formation of interjections in Tjwao fully concord with the developmental processes identified in two other members of the Khoe-Kwadi linguistic family, i.e. Khwe (Kilian-Hatz Reference Kilian-Hatz2003, Reference Kilian-Hatz2008) and ǂAkhoe Haiǁom (Widlok Reference Widlok2016). Moreover, as far as the process of interjectionalization is concerned, in the three languages, secondary interjection typically draws on verbs, nouns, and pronouns. Overall, productive access to all the possible sources of interjections in Tjwao and Khoe-Kwadi validates the view that the category of interjections is open and relatively easily renewable (Ameka and Wilkins Reference Ameka, Wilkins, Östman and Verschueren2006: 2, 7; Norrick Reference Norrick2009: 889).

Lastly, our study provides further evidence for trends exhibited by interjections in other languages that have recently been noticed in scholarly literature. In particular, in Tjwao, the initial syllables of primary emotive interjections tend to either be onsetless or exhibit semi-vocalic onsets. That is, primary emotive interjections usually start with a vowel or a semi-vowel rather than with a genuine consonant. In this regard, Tjwao attests to a behaviour previously observed in Xhosa (Andrason and Dlali Reference Andrason and Dlaliforthcoming) and Biblical Hebrew (Andrason et al. Reference Andrason, Hornea and Joubert2020). This behaviour is most likely related to the general vocalic nature of interjections (Nübling Reference Nübling2004: 24–5).

5. Conclusion

The present paper provided a systematic description of interjections in Tjwao, the first in scholarship thus far. The analysis of the original evidence within a prototype-driven approach demonstrates that in Tjwao: (a) the interjectional lexical class constitutes an internally diverse category confined between the canonical centre and a non-prototypical periphery; and (b) emotive primary interjections exhibit the highest degree of canonicity and extra-systematicity, while the canonicity and extra-systematicity of secondary phatic interjections is the lowest. Overall, the research validates the utility of the prototype-driven model in studies on interjections, corroborating its synchronic and diachronic propositions.

Abbreviations

- ADVZ –

adverbializer

- ANT –

anterior

- C –

common gender

- CAU –

causative

- COP –

copula

- DEM –

demonstrative

- EMPH –

emphatic

- F –

feminine

- FUT –

future

- IMP –

imperative

- INTENS –

intensification/intensifier

- INTJ –

interjection

- IPFV –

imperfective

- J –

juncture

- M –

masculine

- NEG –

negator/negation

- O –

object

- PN –

proper noun

- PRF –

perfect

- PROG –

progressive

- PST –

past

- Q –

question marker

- SG –

singular

- 1 –

1st person

- 2 –

2nd person

- 3 –

3rd person