The Armenian Arsacid king Aršak II (r. 350–68) stood before the Sasanian shāhanshāh Šāpur II (r. 309–79) on Iranian ground and repeatedly professed his obedience. Šāpur did not trust his vassal, though, and so he devised a trick to verify Aršak's loyalty. He imported Armenian soil to the Sasanian court. Even as Aršak called himself Šāpur's servant, the king of kings took Aršak by the hand and led him to stand over Armenian land. Once there, Aršak could no longer dissimulate and he cried out:

Away from me, malignant, servant, lording it over your lords! I shall not spare you or your children from the vengeance [due] to my ancestors, nor forgive the death of king Ardavān.Footnote 1 For you who are [but] servants have now taken the cushion from us, your lords. But I shall not concede this until that place of ours shall return to us!

՚Ի բաց կաց յինէն ծառայ չարագործ տիրացեալ տերանցն քոց․ այլ ոչ թողից զքեզ և որդւոց քոց զվրէժ նախնեաց իմոց, և զմահն Արտևանայ արքայի։ Զի այժմիկ ձեր ծառայից զմեր տերանց ձերոց զբարձ կալեալ է․ բայց ոչ թողից, եթե ոչ տեղիդ մեր առ մեզ եկեսցէ.Footnote 2

Šāpur then led Aršak back onto Iranian soil. The Armenian king apologized profusely and went back to claiming submission.

Šāpur's trick continued, according to P‘awstos Buzandac‘i, from morning into evening. Aršak alternated between servile obedience and vitriolic revenge as he moved back and forth from Iranian to Armenian soil. This test, as one might suspect, led to an awkward dinner conversation that night. The kings of Iran and Armenia should have sat next to each other at the same cushion, but Šāpur instead arranged for Aršak to be demoted and for his cushion to rest directly on Armenian soil. Aršak was angry and announced: “That is my place where you are reclining, get up from it and let me take my ease there, for that has been the place of our people. And when I shall reach my own realm, I shall seek the utmost vengeance from you!” (Իմ այդ տեղի, ուր դուդ ես բազմեալ․ յոտն կաց այդի, թող ես այդր բազմեցայց, զի տեղի ազգի մերոյ այդ լեալ է․ ապա եթե յաշխարհն իմ հասից, մեծամեծ վրէժս խնդրեցից ՚ի քէն).Footnote 3

This anecdote engages a thorny question in the study of Armenian history. Although Aršak only spoke his mind on Armenian soil, his words did not inscribe Armenian identity. Aršak vehemently addressed the king of kings not as an Armenian, but as an Arsacid. He expressed his legitimacy based on his people (azg) and their loyalty to the memory of Ardavān (r. 213–24), the last Great Arsacid king whose death in battle against Ardašīr (r. 224–42) ushered the creation of the Sasanian Empire. Aršak's azg, then, is not the Armenian ethnos, but rather the Arsacid genos, thus collapsing the difference between the Great Arsacids and the cadet Armenian branch.Footnote 4 This tale offers historians insight into the lasting relevance of the memory the Great Arsacids in bolstering Armenian claims to legitimacy and an explanation for Armenian–Sasanian relations. On the one hand, Armenians engaged with Sasanian art and culture, and Armenian generals were fêted as heroes of the realm as they led Sasanian armies in the East. Yet on the other hand, early Armenian literature reads as a litany of Sasanian atrocities. The Battle of Avarayr in 451 looms large in Armenian memory and the Sasanians, damned as a whole for Yazdegerd II's misdeeds, are much maligned in Armenian sources. The anecdote of Aršak at Šāpur's court provides a medieval explanation for this disconnect, balancing active Armenian involvement in Sasanian military and court with the simultaneous disparagement of all things Sasanian. Arsacid lineage continued to inform Armenian claims to power and Armenian interactions with the Sasanians well after the fall of the Parthian realm.

Following the fall of the Sasanian Empire, historians writing in Arabic and Armenian transformed much of Iranian history into something new.Footnote 5 The Sasanians retained their usefulness as models of rule for the Umayyads and ʿAbbāsids alike, not to mention the many families of the Iranian intermezzo who would subsequently reinvent Sasanian idioms of power.Footnote 6 The Arsacids were not as salient to post-conquest Muslims and, accordingly, Arsacid history fell to the wayside in Arabic texts. By contrast, medieval Armenians could not unremember the Arsacids. The second Great Arsacid king Aršak the Great had invested his brother Vałaršak as king over Armenia, establishing a line of Arsacid kings through a cadet branch of the family. While the Great Arsacids fell from power with the death of Ardavān in 224, the Armenian Arsacids held out against Sasanian expansion and so lasted a full two centuries longer, only falling from power in 428. Arsacid rule was indeed a distant memory by the time of the Islamic conquests, but it was more recent in Armenia than it was in Greater Iran.

Arsacid longevity alone did not assure their centrality to the Armenian narrative. Rather, the Armenian Arsacids were touchstones of both political and ecclesiastic power in medieval Armenia.Footnote 7 The Armenian Arsacids were responsible for the spread and protection of Christianity through the elevation of a line of Parthian patriarchs and they remained independent in the face of Sasanian expansion. Medieval Armenian sources consistently identified Arsacid kings and Grigorid patriarchs of the Armenian Church with the epithet Parthian, Part‘ew (պարթև). The traditional title of the Parthian elite, Pahlav (պահլաւ), also continued to appear in Armenian sources even into the early Islamic period, before the emergence of the New Persian pahlavān (hero). It is hardly surprising, then, that the Arsacids and Parthians more broadly retained their relevance to Armenian authors in the Umayyad and early ʿAbbāsid periods.

Narrating Great Arsacid history is an exercise in chasing elusive and amorphous shadows. A. Hartmann explained that “there is not one ultimate memory, but rather diverse cultures of memory at different times, societal structures, and social strata, and … these cultures of memory are dynamic, creative and discursive”. She further posited that memory may or may not be competitive, depending on whether there is a “plurality of cultures of memories” or “a single hegemonic culture of memory”.Footnote 8 The significance of the Arsacid past was contested, so multiple cultures of memories relating to Parthian rule emerge from the pages of Arabic, Armenian, and Persian sources. This article explores early medieval Armenian constructions of the Arsacid past. Armenians writing between the late Sasanian and early ʿAbbāsid periods invested Arsacid history and Parthian identity as markers of independence from the Iranian empire, whether ruled by the shāhanshāh or the caliph. The main symbol of this independence was the city of Balkh, located in modern Afghanistan. Despite the remarkable heterogeneity of Armenian historiography, extant sources reflect a hegemonic culture of memory pertaining to Balkh within early medieval Armenia,Footnote 9 even if each individual author had his own idiosyncratic reasons for drawing on this tradition. In other words, despite the wide variety of voices, sources, and agendas found in early medieval Armenian sources, the stories about Balkh draw similar conclusions.

The first part of this article investigates how Balkh became a site of memory in medieval Armenia. Scriptural geography, genealogy, folk etymology, and origin stories serve as strategies of remembrance to establish Balkh as a touchstone of both Arsacid power and Parthian identity. The second part of this article explores why medieval Armenians fixated on Balkh as a symbol of independence. Medieval Armenian histories establish Balkh in a broader narrative of rebellions against the shāhanshāh. They also legitimize Armenian independence, imagined as both political (Arsacid royalty) and ecclesiastical (the Grigorid patriarchs). The model for such independence was the Great Arsacid line which ruled from Balkh, invincible and capable of completely decimating Sasanian armies. We cannot understand how and why Armenians deployed Balkh as a symbol based solely on narratives of “what really happened” in either Armenia or Khorasan. The Great Arsacids who ruled from Balkh are, after all, likely to be later interpretations of the Parthian kings intertwined with stories about the Kushānshāhs. Balkh accrued layers of meaning in Armenian literature that spoke to the intended audiences and the political realities of the medieval period. As such, the final part of this article analyses Balkh as a site of memory, briefly accounting for the specificities of the early medieval Armenian perspective vis-à-vis the perspectives of post-conquest Muslims as preserved in Arabic sources.

I. Strategies to remember Balkh

Armenian sources of the Sasanian and early Islamic periods invest Balkh with considerable power through scriptural geography, genealogies, folk etymology, and origin stories of pre-eminent medieval Armenian noble houses. These strategies work together to locate Balkh as the source of Armenian power.

Scriptural geography

Anania Širakac‘i (seventh century) wrote his Geography more or less contemporaneously with the Islamic conquests. The short recension of Širakac‘i's text (translated by Hewsen) identifies ArianaFootnote 10 as the k‘ust of Xorasan (քուստի Խորասան),Footnote 11 which is composed of a number of different lands:

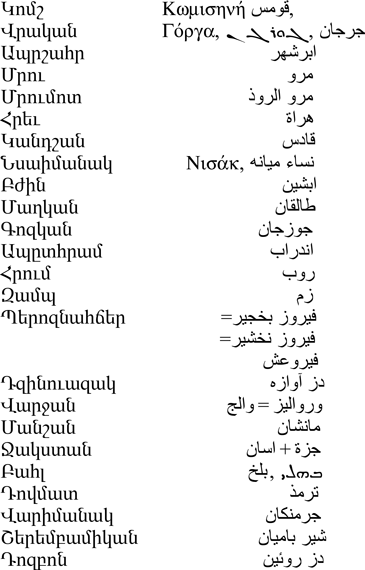

Komš, Vrakan, Apršahr, Mru, Mrumot, Hrew, Kandšan, Nsaianak, Bžin, Małkan, Gozkan, Apǝthram, Hrum, Zamb, Peroznahčer, Dzinuazak, Varǰan, Man, Šanǰakstan, and Bahl, which [belong to] the Parthians; Dovmat, Varimanak, Šerembamikan and Dozbon.Footnote 12

Կոմշ, Վրական, Ապրշահր, Մրու, Մրումոտ, Հրեւ, Կանդշան, Նսաիմանակ, Բժին, Մաղկան, Գոզկան, Ապըտհրամ, Հրում, Զամպ, Պերոզնահճեր, Դզինուազակ, Վարջան, Ման, Շանջակստան, Բահլ, որ են Պարթեւք, Դովմատ, Վարիմանակ, Սերեմբամիկան, Դոզբոն․Footnote 13

Thankfully, Markwart (Reference Markwart1901: 71–91) identified these toponyms in Ērānšahr nach der Geographie des Ps. Movses Xorenac‘i (1901) with remarkable success:

If we follow Markwart's identifications and Hewsen's translation cited above, Širakac‘i's Parthia includes lands in modern north-eastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan, and northern Afghanistan.

The long recension of Širakac‘i's Geography, however, only identifies Balkh as Parthia: “to the north [of Ariana] is the province of Parthia between Cold Carmania and Hyrcania, according to Ptolemy, but today, because of the city of Bahl, the Persians call it Bahli-Bamikk‘, which is ‘Morning Bahl’” (ի հիւսիւսոյ Պարթեւաց աշխարհն, ասէ Պտղոմէոս՝ ընդ մէջ ցուրտ Կրմանայ եւ Վրկանի․ բայց Պարսիկք կոչեն այժմ յաղագս Բահլ քաղաքի զնա Բահլի-Բամիկք, որ է Բահլ-առաւօտին).Footnote 14 The Middle Persian bām means dawn and bām-īg refers to the light of dawn.Footnote 15 The association of Balkh with the morning further solidifies its eastern location, marking the city as the place where the sun rises. The long recension of Širakac‘i's text also acknowledges that the definition of Parthia can be troublesome and offers an explanation: “The Holy Scriptures call all of Ariana ‘Parthia’, but I think this is because the kingdom belonged to the former. The Persians call these regions Xorasan, that is, ‘Eastern’” (Եւ աստուածային գիրն զամենայն Արեաց աշխարհն Պարթեւք կոչէ․ ինձ թուի վասն թագաւորութեան ի նոցանէ լինելոյ։ Բայց Պարսիկք կոչեն զկողմանքս զայս Խորասան, այսինքն արեւելեայ).Footnote 16 He then lists several other cities associated with Khorasan.

Širakac‘i's claim that the broader definition of Parthia stems from Scripture is interesting because Parthia is not actually defined in the Bible. Xorenac‘i (eighth or ninth century) offers an explanation for this confusion:

The divine Scriptures show us that the twenty-first patriarch after Adam was Abraham, and from him descends the Parthian people.Footnote 17 For [Scripture] says that after the death of Sarah, Abraham married K‘etura, from whom were born Emran and his brothers. These Abraham in his own lifetime separated from Isaac, sending them to the east. From them springs the Parthian people, and descended from these is Aršak the Brave, who rebelled against the Macedonians and reigned in the land of the K‘ušans…Footnote 18

ՅԱդամայ քսաներորդ առաջներորդ նահապետ մեզ զԱբրահամ աստուածայինքն ցուցանեն պատմութիւնք, և ի նմանէ եղեալ ազգդ Պարթևաց։ Քանզի ասէ, յետ մեռանելոյն Սառայի՝ առեալ Աբրահամու կին զՔետուրայ․ յորմէ ծնան Եմրան և եղբարք նորա, զորս Աբրահամ ի կենդանութեանն իւրում մեկնեաց յԻսահակայ․ արձակելով յերկիրն արևելից։ Յորոց սերեալ ազգ Պարթևաց․ և ի նոցանէ Արշակ քաջ, որ ապստամբեալ ի Մակեդոնացւոց՝ թագաւորեաց յերկըրին Քուշանաց․․․Footnote 19

These passages allude to Genesis 25: 2, according to which Abraham had sons with his concubine Ketura, and 25: 6, which reads: “But while he [Abraham] was still living, he gave gifts to the sons of his concubines and sent them away from his son Isaac to the land of the east”. Xorenac‘i also refers to Aršak the Brave as a descendant of Ketura: “the Parthians rebelled from subjugation to the Macedonians. From then on Aršak the Brave ruled, who was from the seed of Abraham out of the descendants of K‘etura, for the fulfillment of the saying of the Lord to Abraham: ‘Kings of nations will come forth from you’”. (Genesis 17: 6 and 16) (ապստամբեն Պարթևք ի ծառայութենէ Մակեդոնացւոցն։ Ուստի և թագաւորեաց Արշակ Քաջ, որ էր ի զաւակէ Աբրահամու, ի Քետուրական ծննդոց, առ ի հաստատել բանին Տեառն առ Աբրահամ, թէ թագաւորք ազգաց ի քէն ելցեն).Footnote 20

These passages map the Parthians onto the biblical landscape, making them the descendants of Zemran of the Book of Genesis, the son of Abraham through Ketura. The claim that Scripture identified the entire region as Parthia requires the assumption that the “east” in Genesis refers to Parthia. The passages in Širakac‘i and Xorenac‘i work together, then, to identify Balkh not just geographically, but also biblically – and, so, signalling its importance as a building block of identity construction.

Genealogy

Xorenac‘i is not the only medieval Armenian author concerned with tracing the origins of the Parthians back to Abraham and, from him, to Adam. Several medieval Armenian historians present genealogies to locate the Arsacids in sacred history, lending scriptural explanation to the power structures of medieval Armenia by tracing the descent of humankind. Such genealogies also demonstrate the connections between the Great Arsacids and the Armenian Arsacids. The only thing differentiating the two was that the Great Arsacids ruled from Balkh, which means that the city appears consistently in genealogical explications about the Parthians.

The seventh-century Primary History of Armenia starts with Japheth and lists out his progeny, generation by generation, including the Armenians and the Parthians.Footnote 21 The anonymous author describes the exploits and military successes of the Arsacid king Aršak the Great, who reigned “in Bahl šahastan in the land of the K‘ušans” (ի Բահլ Շահաստանի յերկիրն Քուշանաց).Footnote 22 To segue into the next generation, the author describes the partition of the empire:

And these are the princes of the Parthians who reigned after Aršak their father in Bahl šahastan in the land of the K‘ušans. They say that Aršak, king of the Parthians, had four sons: the first, they say, he made king over the land of the T‘etalians, the second over the Cilicians, the third over the Parthians, and the fourth over the land of Armenia.Footnote 23

Եւ այս են իշխանք Պարթևաց, որք թագաւորեցինն զկնի Արշակայ հաւր իւրեանց ի Բահլ շահաստան յերկիրն Քուշանաց։ Որդիք չորք ասեն լեալ Արշակայ արքայի Պարթևաց․ զառաջինն ասեն թագաւորեցոյց Թետալացւոց աշխարհին․ զերկրորդն ի վերայ Կիլիկեցւոց․ զերրորդն ի վերայ Պարթևաց․ զչորրորդն ի Հայաստան աշխարհին.Footnote 24

This provides kinship relations between Parthian, T‘etal, Cilician, and Armenian royalty, all claiming authority through descent from Aršak who ruled over Balkh. The author then provides two lists of names to chart the Arsacids genealogically. The first covers the Great Arsacids who ruled over Bahl šahastan in the land of the K‘ušans, a designation that appears frequently in the genealogical summaries, followed immediately by a list of the Arsacids who ruled over Armenia. In this form, the lists of kings appear as parallel claims to legitimacy, particularly given the way that many of the names jump from one list to the next (e.g. Aršak, Ardavān, Aršawīr, Vałaršak). The repetitive references to the city of Balkh in these lists, then, signals to the reader-audience which Aršak is intended, as if the branches would be hopelessly confused without the geographical marker to distinguish between the two.

Balkh appears in other genealogical lists designed to bind the Parthians and Armenians to each other and to the biblical narrative. As we saw above, Xorenac‘i's history also asserts genealogical claims made on behalf of the Arsacid kings. He starts at the beginning with Adam, which sets him in a deep-rooted tradition of employing biblical genealogy as the basis for identity construction. Xorenac‘i locates Aršak explicitly: “Aršak the Brave reigned over the Parthians in the city that is called Bahł Aṙawotin [i.e. Morning Balkh] in the land of the K‘ušans” (Թագաւորէ ի վերայ Պարթևաց Արշակ Քաջ ի քաղաքին, որ կոչի Բահղ Առաւօտին, յերկրին Քուշանաց).Footnote 25 The son of Aršak the Brave, Aršak the Great, also ruled from Balkh and he appointed his brother Vałaršak over Armenia. Xorenac‘i, like the author of the Primary History, lists generations of Arsacids with the heading “these are the Pahlavik kings” (եւ են թագաւորք պահլաւիկք այսոքիկ).Footnote 26 Balkh appears to denote which kings were Great Arsacids and which were Armenian Arsacids.

Folk etymology

The designation of the Arsacid kings as Pahlavikk‘, or Pahlavs, further embeds the city of Balkh into the language of legitimacy in medieval Armenia. The term Pahlav is the dynastic title of the Parthian elite.Footnote 27 Modern scholars have (not without contention) associated the title Pahlav with the land of Parthava. Footnote 28 Some references in early Armenian literature seem to corroborate this reading, albeit laconically. For example, the fifth-century History of the Armenians by Agat‘angełos explains that the Armenian Arsacid king Xosrov sought vengeance following the death of Ardavān and the fall of the Great Arsacid line. Ardašīr swayed a Parthian lord – the father of Grigor Lusaworič‘, no less – to side with him by promising to reward him: “I shall return to you (your) native Parthian (land), your own Pahlav” (զբնութիւնն պարթևական, զձեր սեփական Պալհաւն ի ձեզ դարձուցից).Footnote 29 It is not entirely clear if this phrasing implies apposition or if the part‘ewakan (land) is something different from the Pahlav. Xorenac‘i includes the same passage, though he inserts specific reference to Balkh: “he [Ardašīr] promised to return to them their original home called Pahlav, the royal city of Balkh, and all the country of the K‘ušans” (խոստանայր զբուն տունն դարձուցանել ի նոսա, որ Պահլաւն կոչէր, զարէայանիստ քաղաքն Բահլ, և զամենայն աշխարհն Քուշանաց).Footnote 30 Again, the definition of Pahlav and the relationship between Pahlav and Balkh are unclear, though their centrality to Parthian identity is obvious. Other passages in Xorenac‘i's text inform the interpretation of this passage, such that we might read Pahlav in apposition to Balkh.

Xorenac‘i twice suggests that the term Pahlav is a relative adjective (a nisba, so to speak) for Balkh: the Armenian toponym Bahl was read as the source for Pahlav, meaning “of Bahl”. He explains the rise of certain Parthian families, noting that when the king Artašēs reigned he honoured his siblings: “he promoted them above all the noble families, preserving the original name of each family so that they were called as follows: Karen Pahlav, Suren Pahlav, and the sister Aspahapet Pahlav” (և ի վերայ քան զամենայն նախարարութիւնս կարգէ, զնախնականն ի վերայ պահելով զանուն ազգին, զի կոչեսցին այսպէս․ Կարենի Պահլաւ, Սուրենի Պահլաւ, և քոյրն՝ Ասպահապետի Պահլաւ).Footnote 31 Xorenac‘i repeats this information twice, in fact, and draws attention to the repetition. It was such important information, he claims, that it merited retelling because it explained the heritage of Grigor Lusaworič‘ and, through him, the Parthian patriarchs of the Armenian Church. Xorenac‘i also explains why the siblings of Artašēs were called Pahlav: “his brothers would be called Pahlav from the name of their city and great and fertile land” (զեղբարսն անուանել Պահլաւս՝ յանուն քաղաքին իւրեանց և աշխարհին մեծի և քաջաբերոյ).Footnote 32 With the reference to their city, Xorenac‘i does not necessarily trace Pahlav to Parthava. This is not surprising, as the Armenian word for Parthia, Part‘ewk‘, could not be confused with Pahlav. In Sebēos's history, for example, the title Pahlav frequently appears side-by-side with Part‘ew.Footnote 33 This suggests that medieval Armenians understood the two to serve different functions, divorcing Pahlav from the toponym Parthava.

Another passage in Xorenac‘i's history also suggests that he understood Pahlav to mean Balkhī. In the genealogical passages that listed out the Arsacid kings, Xorenac‘i explains:

From them [Abraham and Keturah] springs the Parthian people, and descended from these is Aršak the Brave, who rebelled against the Macedonians and reigned in the land of the K‘ušans for thirty-one years; and after him his son Artašēs for twenty-six years, and then Aršak, the latter's son, called “the great”, who killed Antiochus and made his brother Vałaršak king of Armenia, appointing him second in his kingdom. He himself went to Bahl and ruled there securely for fifty-three years. Therefore his offspring were called Pahlavk‘ just as those of his brother Vałaršak [were called] Arsacids after their ancestor's name.Footnote 34

Յորոց սերեալ ազգ Պարթևաց․ և ի նոցանէ Արշակ քաջ, որ ապստամբեալ ի Մակեդոնացւոց՝ թագաւորեաց յերկըրին Քուշանաց ամս երեսուն և մի․ և յետ նորա որդի նորին Արտաշէս ամս քսան և վեց․ ապա Արշակ նորին որդի, որ կոչեցաւն մեծ, որ զԱնտիոքոսն եսպան և զՎաղարշակ զեղբայր իւր թագաւոր կացոյց Հայոց, երկրորդ իւր առնելով։ Եւ ինքն չուեալ ի Բահլ՝ հաստատեաց զթագաւորութիւնն իւր ամս յիսուն և յերիս․ վասն որոյ զարմք նորա Պահլաւք անուանեցան, որպէս և եղբօրն Վաղարշակայ ի նախնւոյն անուն՝ Արշակունիք․Footnote 35

This passage relates the title Pahlav specifically to Aršak's rule in Balkh, not the general province Parthava. Otherwise, there is no explanation for his use of “therefore” (վասն որոյ, “on account of which”), which links the title Pahlav to Aršak's rule in Balkh in particular.

The association of Pahlav with the city of Balkh in particular also appears in much later genealogical tables, possibly deriving from Xorenac‘i. A note in one seventeenth-century manuscript explains that “Abraham took K‘etura as wife, from whom he begot six sons. They killed one another, and the remainder filled the earth. One of these were the Turks, who are also called Palhavunis, after the name of the city of Pahl,Footnote 36 and the Arsacids on account of Aršak the Brave” (էառ կին Աբրահամ զՔետուր, յորմէ ծնաւ որդիս Զ։ Մինն զմինն եսպան, եւ այլքն լցին զերկիր, որոց մի են թուրք, որ եւ Պալհաւունիք կոչին՝ Պահլ քաղաքին անուամբ, եւ Արշակունիք՝ յաղագս Արշակայ քաջին).Footnote 37 While this is a late manuscript, this demonstrates that Armenians read Pahlav as a specific reference to Balkh.

To be sure, reading Pahlav as a nisba cannot confirm an actual etymological connection between Pahlav and Balkh, a question I gladly leave to the philologists. Rather, such folk etymologies reveal the active process of remembering the city and imbuing it with meaning.

Origin stories

The identification of the ruling Arsacids as Balkhī is not the only reference to origin stories that stress the Parthianness of the powerful Armenian elite. Xorenac‘i clarifies that Grigor Lusaworič‘ was Surēn Pahlav, while the Kamsarakan noble house was Karen Pahlav, explaining that this is important to mention “so that you may know that this great family is indeed the blood of Vałaršak, that is, the line of Aršak the Great, brother of Vałaršak” (զի ծանիցես զազգս զայս մեծ, թէ հաւաստի արիւն Վաղարշակայ են, այսինքն զարմ Արշակայ մեծի, եղբօր Վաղարշակայ).Footnote 38 This passage yet again asserts the close connections between the nobles and royals and between the two branches of the Arsacid family. While the Kamsarakank‘ declined in the early medieval period, their purported descendants claimed the name Pahlavuni in the eleventh century. The choice of the name Pahlavuni reveals that they actively drew on their memory of Arsacid power and claim to Parthian heritage as they reinvented their house. Inscriptions and dedications left from the various branches of the Pahlavuni family identify them even as late as the thirteenth century as “of the race of the Pahlavunis to which was united the family of the Arsacids”.Footnote 39

Other houses also situated their power in relation to Parthian and Arsacid history, and explicitly evoked the importance of Balkh as the origin of Armenian–Parthian power. The most famous story, as told by Chinese minstrels (գուսանք) and recorded by an anonymous Armenian author in the Primary History, is dramatic. During the reign of Ardavān, the last Great Arsacid king, two brothers named Mamik and Konak lived in China. Their father Kaṙnam was a powerful lord second only to the king of China. When he died, the king married Kaṙnam's wife and sired a son with her. After the death of the king of China, Mamik and Konak rebelled against their half-brother Čenbakur, but Čenbakur emerged victorious. “Mamik and Konak fled to the Arsacid king who sat in Bahl šahastan in the land of the K‘ušans” (փախստական լեալ Մամիկն և Կոնակն գնան առ արքայն Արշակունի, որ նստէր ի Բահլ շահաստանի, յերկիրն Քուշանաց).Footnote 40 Čenbakur threatened to wage war against “the king of the Parthians” (արքայն Պարթևաց), who protected Mamik and Konak from their half-brother.

But the latter [the Parthian king], sparing the [two] men, did not give them into his hands but wrote to him in a friendly way: “Let the treaty of peace, he said, remain firm between us, for I have sworn to them that they will not die. But I had them taken to the West, to the edge of the world, to that place where the sun enters its mother”. Then the Parthian king ordered his army to take them under heavy guard, with their wives and sons and all their effects, to Armenia to his relative the Arsacid king, who was king of Armenia. And there they multiplied greatly, and they became a great clan from Mamik and Konak.Footnote 41

Իսկ նորա խնայեալ յարսն՝ ոչ ետ զնոսա ի ձեռս նորա, այլ գրէ առ նա սիրով․ «Անդրէն ուխտ խաղաղութեան մերոյ, ասէ, հաստատուն կացցէ ի միջի մերում, զի երդուեալ եմ առ նոսա, զի նոքա մի՛ մեռցին․ այլ ետու տանել զնոսա ի մուտս արևու և յեզր երկրի, ի տեղին յայն, ուր արեգակն ի մայրն մտանէ»։ Յայնժամ հրամայէ արքայն Պարթեաց զաւրաց իւրոց տանել զնոսա զգուշութեամբ մեծաւ, կնաւ և որդւովքն իւրեանց և ամենայն աղխիւն իւրեանց յերկիրն Հայոց առ ազգական իւր արքայն Արշակունի, որ էր թագաւոր Հայաստան երկրին, ուր և սերեալ բազմացան յոյժ, և եղեն յազգ մեծ ի Մամիկայ և ի Կոնակայ։Footnote 42

The designation of Armenia as the land where the sun sets offers a neat parallelism to Balkh of the Morning, where the sun rises. Claiming such exotic and powerful origins, the Mamikonean family subsequently emerged as the most powerful noble house in early medieval Armenia until they fomented two unsuccessful rebellions in the eighth century.

This story has provoked considerable debate, mostly about the potential Chinese heritage of the pre-eminent Armenian noble house of the early medieval period. Modern scholars such as C. Toumanoff have suggested that the Mamikoneank‘ were not in fact Chinese, but rather that they were Georgian.Footnote 43 In the Encyclopaedia Iranica article on the Mamikoneank‘, N. Garsoïan tactfully explains that “this origin is disputed by scholars, who have not yet reached a final conclusion”.Footnote 44 While these disputes will undoubtedly continue apace, the details are not relevant for our current purposes.

Regardless of the “true” ancestral home of the Mamikoneank‘ (a topic that is well outside the purview of this article), the story that circulated in the seventh century clearly connected the Mamikoneank‘ to China. The title of the Chinese emperor, Čenbakur, is attested in many Armenian histories of the early Islamic period including Širakac‘i, Xorenac‘i, and Łewond. Čenk‘ means China or Chinese and bakur is the Armenicized version of the Parthian baɣpuhr, meaning son of God.Footnote 45 The title is also attested in non-Armenian sources: “The word faghfur, an Arabic/Early New Persian rendition of MP bag/y-puhr (Bactrian βαγɛποορο), means ‘son of god’ and is the normal name for the Emperor of China in Classical New Persian texts”.Footnote 46 Further, the insertion of Balkh into this story only makes sense if the ancestors of the Mamikoneank‘ emigrated from China to Armenia, as the city would quite obviously not have been a convenient waypoint en route from Georgia to Armenia. The anonymous author of the Primary History thus could only have been evoking the Chinese imperial elite. A mnemohistorical approach allows us to bypass debates about the “real” homeland of the Mamikoneank‘ in order to analyse the deployment of Balkh as a symbol of Arsacid power and its co-optation into an Armenian narrative.

This foundation story imbues the Mamikoneank‘ with their power in a number of ways. Their ancestors were highborn in the Chinese Empire. They were rebels, ensconced in Balkh, a city famous as a refuge for rebels. They claim protection from the last of the Great Arsacids, who risk a war with China on their behalf. The Great Arsacid king Ardavān himself arranged for them to emigrate from Balkh to Armenia. In this, the path of the two brothers mirrored the migration of the Armenian Arsacids themselves, who also moved from Balkh to Armenia by the order of the Great Arsacids. These parallels between the Mamikoneank‘ and the Armenian Arsacids establish the nobles as comparable to Armenian royalty. In modelling Mamikonean emigration on the Arsacid past, the significance of Balkh expands. It is no longer simply the homeland and power base of the Armenian royalty, but the source of power of the most influential Armenian nobility as well.

II. Celebrating the impotence and decimation of the Sasanian realm

Early medieval Armenian historians employ strategies of remembrance that invest the city of Balkh with great significance, imbued with the power to legitimize noblemen and royalty alike. If the strategies above reveal how Balkh was remembered, they do not adequately explain why Balkh was remembered. Medieval Armenian sources demonstrate no familiarity with Balkh as a contemporary city. They did not describe the shifting populations as the city slowly transformed from a Buddhist centre to an Islamic holy city. Armenian Balkh was not a lived city.Footnote 47

As demonstrated in multiple examples above, Balkh legitimized the Armenian political elite by collapsing the differences between the Great Arsacids and the Armenian Arsacids. Similarly, Balkh legitimized the ecclesiastical elite by tracing the line of Parthian patriarchs back to their Pahlav origins. The memory of Balkh was harnessed to make two additional political claims related to the Armenian relationship with the Sasanian Empire. First, Balkh emerges as the centre of an empire whose kings could easily withstand Sasanian aggression. Second, Balkh emerges as a refuge for Parthian rebels against the Sasanians. These two work together to establish a model for Armenian elite who chafed under Sasanian and caliphal rule.

The Arsacids of Balkh as the model of Parthian independence from the Persians

In all relevant Armenian sources, Balkh remains squarely in an anti-imperial space. The Sasanians, who appear in most Armenian sources as the unjust tyrants who oppressed Armenia, could not control the wily city. Accordingly, Balkh's freedom from Sasanian oppression left open possibilities to explore how just rulers (the Great Arsacids) surpassed their Persian foes.

P‘awstos Buzandac‘i (fifth century) mentions Balkh twice. Even though his broader agenda does not align with the celebration of Arsacid power, his references to Balkh reflect the city's position in the medieval Armenian archive.Footnote 48 Both of P‘awstos's passages about Balkh serve similar agendas. First, the Armenian Arsacid King Aršak II – the same Aršak whose awkward dinner conversation with Šāpur II appears at the start of this article – was in Khuzestān. He acknowledged Sasanian rule: “about that time, the war between the Persians and the Armenians calmed down because the Arsacid king of the K‘ušans, who held the city of Bałx, had stirred up war against Šāpuh, the Sasanian king of Persia” (Եւ զայնու ժամանակաւ խաղաղացաւ պատերազմ տալ Պարսից ընդ Հայս․ զի Արշակունին թագաւորն Քուշանաց, որ նստէր ի Բաղխ քաղաքի, նա յարոյց տալ պատերազմ ընդ սասանականին Շապհու և թագաւորին Պարսից).Footnote 49 While this passage reads somewhat incoherently, the Sasanian capture of Aršak and his army was the actual cause for the Armenian–Persian détente. P‘awstos explains that the shāhanshāh left Aršak in chains and took the imprisoned Armenian army with him to fight the Great Arsacids in Balkh. Šāpur also brought with him a eunuch, the favourite companion of Aršak, named Drastamat. The Great Arsacids (here called the Arsacid Kushans) emerged victorious by a landslide, decimating the Persian forces. Šāpur escaped with his life only due to the heroism of Drastamat. As a boon for these heroic deeds, Drastamat asked to return to Aršak and honour him as king. Šāpur evinced concern at this request, fearful of Aršak, “all the more that he is a king and my colleague, my opponent; who has been held chained in that fortress” (թող թէ զնա զայր թագաւոր և զիմ ընկեր կապեալ եդեալ յայնմ բերդի զհակառակորդն).Footnote 50 Drastamat returned to prepare a kingly banquet for Aršak, who drank deeply of wine, lamented the state of kings under foreign rule, and then plunged his knife through his own heart. His body collapsed onto the cushion where kings recline. Drastamat removed the knife from his king's body and followed him in death.

This anecdote offers a few interesting suggestions about Arsacid–Sasanian relations. From this, it is clear that Armenians understood the Great Arsacids to be greatly superior to the Sasanians, whose forces were obliterated and whose king only survived due to the intervention of a servant of the Armenian Arsacid king. The army of the Armenian Arsacids may have marched east under a Sasanian banner to fight the Great Arsacids of Balkh, but they did so under duress, as defeated prisoners, with no implication of free choice. The Arsacids of Balkh resisted Sasanian aggression and bested both the Sasanian army and the shāhanshāh himself. Although the Sasanians had defeated the Armenian Arsacids and imprisoned Aršak, Šāpur still feared him and identified him as both a colleague and an opponent. This places Aršak and Šāpur as equals. Aršak's death is self-inflicted, the power move of an imprisoned king whose death was itself a protest against Sasanian rule. Drastamat's suicide is not just a statement of support for his king, but the spilled blood of the hero whose bravery upheld the Empire. Their blood stained the very symbols of kingship, suggesting the defiling of legitimate claims to power. What does this mean for Balkh? P‘awstos explicitly identifies Balkh as an Arsacid city. Balkh remained out of reach of Sasanian power and capable of decimating Sasanian forces. The Arsacids of Balkh emerge as the foils to the Armenian Arsacids, a reminder of how the power structure should be working.

The second story in P‘awstos's history follows much the same line as the first. After the death of Aršak II, Šāpur returned to war with the captured Armenian forces: “For at that time, the Sasanian king of Persia had been waging war against the great Arsacid king of the K‘ušans, who held the city of Bałh” (Քանզի զայն ժամանակաւ թագաւորին Պարսից սասանականին տուեալ էր պատերազմ ընդ մեծ թագաւորին Քուշանաց ընդ արշակունոյն, որ նստէր կ Բաղհ քաղաքին).Footnote 51 Yet again, the Great Arsacid king decimated the Sasanian army, leaving not a single Persian soldier alive. Šāpur learned of the fate of his army from two Mamikonean brothers, described as super-human giants, who had “performed many deeds of valor in this battle, though they survived [only] on foot” (բազում քաջութիւնս կատարեալ ի նմին նակատուն, սակայն հետիոտս ապրէին).Footnote 52 Unlike the first story, which casts the Armenian Arsacid king as the imprisoned and moral (if tragically doomed) hero, in this story the Armenian king was complicit. The Mamikoneank‘ returned to Armenia to confront the Armenian Arsacid king Varazdat for plotting against past generations of Mamikonean heroes and for not adequately recognizing their contributions to the realm. The Mamikonean brothers railed against Varazdat, calling him unworthy of claiming Arsacid royalty:

You, then, are no true Arsacid but a bastard child, that is why you have not acknowledged the faithful servants of the Arsacids [i.e., the Mamikoneank‘]. Indeed, we are not even your servants but your equals and [even] greater than you, for our ancestors were kings in the realm of the Čenk‘ [Chinese].Footnote 53 And on account of quarrels [between] brothers, and because much blood flowed, we set out to seek a haven and settled [here]. The first Arsacid kings knew who we were and whence [we came], but you, since you are no Arsacid, go from this realm, lest you die by my hand!Footnote 54

Նա դու չես իսկ Արշակունի, այլ ի պոռնըկութենէ եղեալ ես որդի․վասն այդուրիկ ոչ ծանեար զվաստակաւորսն Արշակունեաց։ Նա մեք չեմք իսկ լեալ ձեր ծառայք, այլ ընկերք ձեր և ի վերայ քան զձեզ․ զի մեր նախնիքն լեալ էին թագաւորք աշխարհին Ճենաց, և վասն եղբարց իւրեանց գրգռութեանն, զի արիւն մեծ անկեալ է ի վերայ․ վասն այնր եմք գնացեալք․ և վասն բարւոյ հանգստի գտանելոյ եկեալ դադարեալ եմք։ Առաջին թագաւորքն Արշակունիք, որք գիտէինն զմեզ ով էաք կամ ուստի էաք․ այլ զի դու քանզի չես Արշակունի, գնա յաշխարհէս, և մի մեռանիր ի ձեռաց իմոց։Footnote 55

Varazdat retorted that the Mamikoneank‘ were welcome to return to China if they were so displeased with his rule. This argument escalated to an armed confrontation, culminating with the Mamikonean lord repeatedly pummeling the Arsacid king over the head with the butt of his spear. Varazdat was forced to flee to Byzantium, while the Mamikoneank‘ raised Arsacid children to take the throne.

In this second story, the Great Arsacids of Balkh remain the invincible foes of the Sasanians, capable of annihilating the entire Persian army (again). Only the Mamikoneank‘ survived, and barely, due to their super-human qualities. This time, two Mamikonean brothers return from Balkh – an obvious nod to the stories of Mamik and Konak, which they then harness explicitly to make their claim to superiority. The Armenian Arsacids again failed to live up to the expectations cast upon them as descendants of the Great Arsacids, so the Mamikoneank‘ challenged them. The Mamikonean heroes evoked the parallels between their family and the Armenian Arsacids, as described above. Both families traced their legitimacy back to the East and to Arsacid greatness. The Mamikonean brothers in this story remind Varazdat of the illustrious heritage of the Mamikoneank‘ and their relationship with the Great Arsacids of Balkh.

In these stories, Balkh performs the same function. It was the residence of the Arsacid kings of the K‘ušans who were entirely unbeatable in battle. They consistently annihilated the Sasanian army. In both cases, the Armenian armies only backed the Sasanians under duress and they died in droves on the field, with the exception of the few plucky if bedraggled heroes. These heroes emerge as the voice of reason, the conscience of the Armenian Arsacids, to remind them of their rightful place in the world. In both of these stories, the goal was to remind the Armenian Arsacids that they should not collaborate with the Sasanians against the Great Arsacids of Balkh. Such collaboration was an unnatural inversion of the expected power structure, turning towards the aggressive and oppressive Persians to wage war against the Arsacids of Balkh who remained the very source of their legitimacy. In both cases, this betrayal spelled defeat for the Armenian Arsacids. Balkh was where the Arsacids remained free of Sasanian aggression, ruling independently with an unbeatable military. The Arsacids of Balkh ruled as the Armenian Arsacids should have ruled.

The city of Parthians and rebels

The story of Mamikonean origins introduces another common theme in Armenian perceptions of Balkh. The brothers escaped China after a failed rebellion, reaching Parthian territory in Balkh beyond the reach of Čenbakur. Balkh also appears in Armenian sources as a refuge for other rebels confronting the Sasanian Empire, frequently associated with loyalties to old Parthian families.

One such reference to Balkh as a refuge for rebels is in Xorenac‘i's account of the rise of the Sasanian Empire. Xosrov, the Armenian Arsacid king, had attempted to raise resistance to Ardašīr's coup over Great Arsacid territory. The first Sasanian shāhanshāh responded by killing all of the scions of his family in the East, the Karen pahlav. Only one survived, a young man named Perozamat who “had taken flight to the land of the K‘ušans” (փախեաւ յաշխարհն Քուշանաց).Footnote 56 Perozamat evaded Ardašīr's attempts to capture him and settled among the Kushans, a Parthian lord safe from ominously predatory Sasanian ambitions. The Kushans thwarted Ardašīr's every attempt and rebuffed his every promise to protect and monitor access to this child. The story of this protected Parthian boy in Kushan territory, Xorenac‘i explains, remained important because it explained the heritage of the noble Armenian family, the Kamsarakank‘ (the ancestors of the Pahlavunik‘ described above).

Balkh and Kushan territory also appear to be a refuge for other famous Parthian rebels. Sebēos relates that Hormozd IV (r. 579–90) ended many of the noble lines of Persia and also killed the Parthian and Pahlav descendants of Anak, the father of Grigor Lusaworič‘. Sebēos then segues neatly into the story of Bahrām VI Čōbīn:

It happened at that time that a certain Vahram Merhewandak, prince of the eastern regions of the country of Persia, valiantly attacked the army of the T‘etals and forcibly occupied Bahl and all the land of the K‘ušans as far as the far side of the great river which is called Vehṙot [Oxus] and as far as the place called Kazbion [دز روئين].Footnote 57

Եւ եղև ի ժամանակին յայնմիկ Վահրամ ոմն Մերհեւանդակ, իշխան արևելից կողմանց աշխարին Պարսից, որ հարկանէր քաջութեամբ իուրով զզաւրս Թետալացւոց և բռնութեամբ ունէր զԲահլ և զամենայն երկիրն Քուշանաց, մինչև յայնկոյս գետոյն մեծի, որ կոչի Վեհռոտ, և մինչև ցտեղին, որ կոչի Կազբիոն։Footnote 58

Although Bahrām set out on this venture in the service of the Sasanian Empire, he sent back so little of the spoils that Hormozd rebuked him. Angered by the king's disrespect, Bahrām's men rallied around their leader and declared an open rebellion against the Sasanian Empire. For our purposes, this rebellion is useful for two reasons. First, it reveals the dangers of Parthian actors even at the imperial court. Bahrām, who was Mihrānid, does not appear as such in Sebēos's history, but rather as merhewandak and mihrac‘i, a servant of Mithra. Yet Sebēos focuses on the Parthianness of the main actors in the fallout of Bahrām's campaign: the mother of Ḵosrow is identified as “a noble of the house of the Parthians” (նախարար տանն Պարթևաց).Footnote 59 She and her brothers kill Hormozd to install the child Ḵosrow II (r. 590, 591–628), allowing his Parthian uncles primacy in raising the new king even as he fled. Despite the destructive capability of Bahrām's rebellion, the true threat to Hormozd was his murderous Parthian wife and her brothers. Second, Sebēos's history demonstrates how Armenians localized rebellion in Balkh. When Bahrām was eventually ousted from power, Sebēos claims that “he went and took refuge in Bahl šahastan, where by Ḵosrow's order he was put to death by its people” (չոգաւ և անկաւ ի Բահլ Շահաստան, ուր և ի բանէն Խոսրովայ սպանաւ ի նոցունց իսկ).Footnote 60 Even here, Balkh evades Sasanian control. While Ḵosrow proved powerful enough to demand Bahrām's death, the people of Balkh (and not any official of the Sasanians) effect the punishment. This projects a city beyond the direct reach of Sasanian control, where the people can choose whether to acquiesce or reject the orders of kings.

Parthia, though not Balkh in particular, also appears in relation to the sixth-century rebellion of Vistahm. Sebēos identifies him as a Parthian, and claims that he goes back to Parthian lands, his ancestral home. Pourshariati claims that this notice about Vistahm's homeland “clearly refers” to Khorasan “in the context of Sebeos's chronicle”.Footnote 61 Although Sebēos never uses the term Khorasan, nor does he define “the land of the Parthians” (երկիր Պարթեաց); Pourshariati is undoubtedly correct. In a later passage, Sebēos refers to the Islamic incursion in the Sasanian East:

In the 19th year of the dominion of the Ismaelites, the army of the Ismaelites which was in the land of Persia and of Khuzistān marched eastwards to the region of the land called Pahlaw, which is the land of the Parthians, against Yazdegerd king of Persia. Yazdegerd fled before them, but was unable to escape. For they caught up with him near the boundaries of the K‘ušans and slew all his troops.Footnote 62

Յամին ԺԹ-երորդ Իսմայելացւոց տէրութեանն, զաւրն Իսմայելացւոց, որ էին յերկրին Պարսից և Խուժաստանի՝ գնացին ընդ արևելս ի կողմանս Պահլաւն կոչեցեալ երկրի, որ է երկիր Պարթեաց, ի վերայ Յազկերտի արքային Պարսից։ Եւ փախեաւ Յազկերտ յերեսաց նոցա, և ոչ կարաց ճողոպրել․ քանզի հասին զհետ նորա մերձ ի սահմանս Քուշանաց, և կոտորեցին զամենայն զաւրս նորա։Footnote 63

Since we know that Yazdegerd died near Marw, we read into this our own assumption that the land east of Persia and Khuzestān is Khorasan. The fact that the seventh-century historian Sebēos describes Khorasan as the “land called Pahlaw, which is the land of the Parthians” demonstrates the longevity of the associations of the East and Parthianness in Armenian chronicles. In short, Sebēos not only places both Bahrām Čōbīn and Vistahm in Parthia, he also locates the death of Yazdegerd (and, so, the collapse of Sasanian rule itself) in Parthia near the borders of the Kushans instead of employing the contemporary toponym Khorasan. The land of the Kushans could not bow to Sasanian control.Footnote 64

III. Overwriting and forgetting the Kushans

If early medieval Armenian authors participated in this hegemonic culture of memory within Armenia by conveying the Parthian past as a model for independent Arsacid rule, this does not imply that the Armenian memories of Balkh were constructed ex nihilo to serve this purpose. In understanding the significance of memory, historians do not relinquish the past to the realm of pure myth. Rather, the process of remembering and forgetting the past has political valence. Stories of the past could be contorted to fit the needs of the (then) present, but this does not signify that they were invented out of whole cloth. Ancient Balkh was home to the Kushan emperors (c. 2nd c. bce–230 ce) and then the Kushano-Sasanians (c. 230–350 ce), who provided a backdrop against which Armenians and post-conquest Muslims could exert their own claims to cultural, religious, and/or political significance. The frequent reference to the Kushans as part of the set phrase “Bahl šahastan in the land of the K‘ušans” suggests that they remained part of how early medieval Armenians navigated the legacies of the Parthian past. The last section of this article briefly addresses the Kushans as a way to place the early medieval Armenian memories into the broader context of the “plurality of cultures of memories”.

Two snippets in Xorenac‘i's history suggest that the “Arsacids ruling in Bahl šahastan in the land of the K‘ušans” could reflect a specifically Armenian rewriting of the Kushans. First, when the first Sasanian shāhanshāh Ardašīr attempted to lure Parthian nobles to support his rule, the Armenian Arsacid king Xosrov moved to forestall him. Xosrov sent out messages “to his own kin the Parthian and Pahlav families, and to all of the forces of the land of the K‘ušans” (առ իւր տոհմայինսն Պարթև և Պահլաւիկ ազգս).Footnote 65 The Aspahapet and Suren branches of the family refused to back Xosrov to fight the Sasanians. When he returned to Armenia, resigned to the fate of the Great Arsacids, Xosrov received a message:

Then there came to him some of his own messengers who had gone to the more illustrious nation far inland, as far as Bahl. They brought him word that “your kinsman Vehsač‘an with his branch of the Karen Pahlav have not given obeisance to Ardašīr, but is coming to you in answer to your summons”.Footnote 66

Յայնժամ հասանեն առ նա ոմանք ի հրեշտակաց իւրոց, որք ի պատուականագոյն ազգն երթեալ էին, ի խորագոյն աշխարհն, ի նոյն ինքն ի ներքս ի Բահլ․ բերին նմա համբաւ, եթէ «ազգական քո Վեհսաճան, հանդերձ ցեղիւն իւրով Կարենեան Պահլաւին, ոչ հնազանդեաց Արտաշրի, այլ ի կոչ քո դիմեալ գայ առ քեզ»։Footnote 67

A modern numismatist (Carter Reference Carter1985: 217, n. 3) identified Xorenaci's ruler of Balkh Vehsač‘an as the Kushan king Vāsudeva I (r. 191–225), who minted coins in Balkh. She labelled Xorenac‘i's claim to kinship with Karēn Pahlav “a seemingly odd notion”. The logic here is not odd, so much as internal to the Armenian tradition. Xorenac‘i himself had built extensively on centuries of Armenian traditions that identified the East and Balkh in particular as Parthian. If a dynasty held its own against the Sasanians in Balkh, it would have made sense for a medieval Armenian to label it as Arsacid.

A second case returns to Xorenac‘i's description of Perozamat, the Parthian youth from Karen Pahlav who fled to the land of the Kushans to evade Ardašīr's attempts to annihilate the scions of the Great Arsacids. This Perozamat reportedly lived in the land of the Kushans in the third century and returned to Armenia during the reign of the Sasanian shāhanshāh Šāpur (r. 240–270). This means that Xorenac‘i's Perozamat lived in the land of the Kushans at precisely the same time that a Kushano-Sasanian king named Pērōz (r. c. 245–270) minted Bactrian coins in the city of Balkh.Footnote 68 At least in Xorenac‘i's case, then, it stands to reason that some of the “Arsacids” of Balkh were in fact an interpretive reading of the actual rulers of the Kushans at the end of the Great Kushan Empire and start of the Kushano-Sasanian line. This is not an obvious identification because scholars of Kushano-Sasanian kings would have no reason to investigate the dealings of Parthian elites. From the Armenian perspective, though, all of the rulers of Balkh were Parthian.

A mnemohistorical approach allows historians to acknowledge how and why Balkh became central in the Armenian texts of the early Islamic period without concern as to whether this reflected the “reality” of the city's history. The traditions described above that link Balkh and the Arsacids are specifically Armenian. They uphold Armenian claims to legitimacy and memories of independence vis-à-vis the Sasanians and the Caliphate. Their goal was never to describe the Kushānshāhs, but to narrate stories that placed Armenian claims to political legitimacy into the broader framework of Iranian history.

Such traditions are not wholly different from what appears about the city in Arabic sources; however, the goal and emphasis are different in Arabic. Like the Armenian, extant Arabic sources do not demonstrate sustained concern about the Kushan emperors or the Kushano-Sasanians. However, historians writing in Arabic had no reason to bolster the Arsacids as symbols of legitimacy, either. The caliphs and Muslim elites such as the Būyids were far more likely to employ the Sasanians as models of kingship, rather than the Arsacids. There are two trends to the Arabic traditions about Balkh. On the one hand, Balkh was associated with pre-Islamic grandeur. It was a Kayānid city, where Zoroaster once walked. It was therefore a thoroughly Persian city. However, there are also Islamizing threads that serve to ascribe new meanings to layer over the pre-Islamic traditions.Footnote 69

Muslim sources in Arabic most frequently identify Balkh as the capital of the Kayānid king Kayḵosrow and his descendants.Footnote 70 They identify this specifically as a Persian tradition: “The Persians claim, according to what is mentioned in the book of Sakīsarān, that … those people [Kayḵosrow and his family] settled Balkh, which was the capital of their realm” (وعبر .Footnote 71(الفرس على ما ذكر فى كتاب السكيسران ان…هؤلآء القوم كانوا يسكنون بلخ وكانت دار مملكتهم Masʿūdī also explains that “in some of the tales reported by the Persians, it is mentioned that he [Kayḵosrow's successor] built Balkh the beautiful” (ذكر فى بعض الروايات من اخبار الفرس انه بنا بلخ الحسنا).Footnote 72 The city became the home of Goštāsp, who received the prophet Zoroaster.Footnote 73

The other main thread of traditions about Balkh in ʿAbbāsid-era literature serves to Islamize the city. The Faḍāʾil-i Balkh relates a tradition about Abraham, recorded on the authority of the Prophet Muḥammad himself. Abraham reportedly visited Balkh and prayed there at the suggestion of an angel, who identifies the city as the location of a prophet's grave. Abraham prayed for the city's success.Footnote 74 Earlier sources also provide prophetic connections to Balkh. Dīnawarī acknowledges that the Kayānid dynasts built the city, but places its foundation during the reign of Solomon, who even travelled east and visited it.Footnote 75 This adds another layer of prophetic history, melding sacred history into the reigns of legendary Persian kings. Other sources do not describe the significance of Balkh based on Abrahamic faiths, but instead identify it as the site of Nawbahār, the temple built to honour the moon.Footnote 76 While this preserves some information about Buddhist practice in pre- and early Islamic Balkh, some sources work to reconcile that by integrating stories of Abraham into the foundation of such non-Islamic monuments.Footnote 77 Additionally, information on Nawbahār has obvious relevance for the authors writing in the early ʿAbbāsid period because upkeep of the temple was the purview of the Barmakī family.

Even if most fixate on the tales about the Kayānid or Islamic history of the city, Balkh does appear as an Arsacid capital in one Arabic text from the early Islamic period. After Alexander slew Darius, Yaʿqūbī claims, the Party Kings (a term that frequently appears to refer to the Arsacids) ruled from Balkh: “Then the kingdom of Persia became divided and was ruled by kings called the Party Kings. Their royal residence was located at Balkh. Genealogists assert that they were descendants of Gomer, son of Japheth, son of Noah” (فافترق ملك فارس وملك ملوك يسمّون ملوك Footnote 78(الطوائف وهؤلاء كان ملكهم ببلخ ويزعم النسّابون انّهم من ولد عامورا بن يافث بن نوح This passage demonstrates that at least one historian writing in Arabic in the ʿAbbāsid period in fact knew of the stories about Balkh as an Arsacid city where the descendants of Japheth ruled. This claim is very much in line with Armenian sources above, which confirms that the Arabic and Armenian sources should not be read as wholly different from one another. It is possible that Yaʿqūbī even heard of these tales in Armenia, given his familial ties to the province. However, this memory was both contested and actively curated. Yaʿqūbī specifies explicitly that the history of Arsacid Balkh was actively forgotten, rather than passively unremembered. “They [the Persians] had historical reports; these were recorded, but, as we have seen, most people reject them and consider them abhorrent; we have omitted them because our policy is to leave out everything abhorrent” (ولهم اخبار قد اثبتت راينا اكثر الناس ينكرونها ويستبشعونها فتركناها لانّ مذهبنا حذف كلّ مستبشع).Footnote 79 While the Muslim authors seem to have had no trouble accepting Kayānid claims to the grandeur of Balkh, even if qualifying them as legends and tales, Yaʿqūbī is quite clear to disavow Arsacid presence in the city. Yaʿqūbī's comment here suggests that the Arsacid past of the city was forgotten in the early Islamic period, while new memories were constructed and prioritized to make the pre-Islamic past relevant for historians of the ʿAbbāsid period and the Iranian intermezzo.

Although the historians writing in Arabic sometimes employ the same strategies of remembrance (e.g. genealogy, biblical prophets), they do not embark on the same project as the Armenian texts. For example, Balkh sometimes appears as a city of rebels in Arabic sources, as well.Footnote 80 The city was a refuge for the ʿAlid Yaḥyā b. Zayd during the reign of ʿAbd al-Malik (r. 684–705);Footnote 81 a key city as Qutayba b. Muslim put down revolts in 705 and 708–9;Footnote 82 the site of a rebellion of Ḥārith b. Shurayḥ in 733–4;Footnote 83 and the domain of Rāfiʿ b. Layth during the reign of Amīn (r. 809–13).Footnote 84 The Arabic reports acknowledge the role of Balkh in rebellions on the edge of the Sasanian empire,Footnote 85 but far more frequently they locate Balkh in Islamic history, as part of the Islamic world but just out of reach of the caliph.Footnote 86 By contrast, the Armenian sources only remember pre-Islamic rebels in Balkh, each with ties to Parthianness, as a way to foment trouble against the Sasanians. The Arsacids and other Parthian rebels (e.g. Bahrām Čōbīn) retained their significance into the ʿAbbāsid period as models for Armenian independence from caliphal rule.

IV. Conclusion

As the fount of Arsacid power, Balkh accrued traditions over time. These layers were biblical, which made the Parthian story part of Christian history. They were also both political and social. Balkh was remembered as the seat of the Great Arsacid kings. Armenian claims to legitimacy hinged on the recognition that the Great Arsacids and the Armenian Arsacids were one and the same, so the homeland of the Great Arsacids became the homeland of the Armenian Arsacids. Just as it was the homeland of the great Parthian houses, such as Karen and Suren, so too was it the homeland of the great Armenian houses, Pahlavuni and Mamikonean. The city offered refuge to the rebels and the oppressed, on the edges out of reach of both the Persians and the Chinese. What was Balkh? To early medieval Armenians, Balkh was the heart of Parthianness and, so, the original homeland of the Armenian kings and nobles. It bore the Great Arsacids, who consistently annihilated the armies of the Sasanian shāhanshāh. After the fall of the Great Arsacids, it became a city of Parthian rebels who fought valiantly for their independence from Persian aggression.

Stories of rebels and independent kings found their footing in early medieval Armenia, where vassal status under the Sasanians and the Caliphate seemed to offer much the same challenges. To medieval Persians, though, such stories of Balkh as a centre of rebellion and independence made less sense. Historians writing in Arabic similarly forgot the Kushānshāhs and employed many of the same strategies of remembrance, but in the early ʿAbbāsid period most references to Balkh underscore caliphal claims and conjure memories of a long-lost, legendary Persian past. This is not to suggest that Armenian and Persian stories about Balkh were irreconcilable; the lines between literary traditions of the Near East have always been porous. Instead, the differences in medieval accounts related to Balkh reflect the competitive construction of cultures of memories. Historians honed in on different snippets of the traditions circulating about Balkh based on what they wanted to say or what they deemed relevant or interesting to their audiences.

It is hardly surprising that most of the sources that remember Balkh as a city of independence and rebellion date from the late Sasanian to the early ʿAbbāsid periods: P‘awstos Buzandac‘i's History of the Armenians, Širakac‘i's Geography, the anonymous Primary History, Sebēos's History, and Xorenac‘i's History of the Armenians. Although very different in outlook and goals, these authors all reflect the hegemonic culture of memory pertaining to Balkh within early medieval Armenia. These sources date between the fifth and ninth centuries, when Armenia was consistently under imperial control. Following the collapse of the ʿAbbāsid Caliphate in 861 with the death of Mutawakkil, Armenia was not reintegrated into the empire. Balkh appears in passing mention in Armenian histories of the tenth century, but it is rare and did not retain its significance.Footnote 87 Given that remembering is essentially a political process, it is likely the symbol of independent Parthian power and rebellion faded with the rise of the Bagratuni and Arcruni kingdoms. There was no foreign power for the Armenians to chafe against, simply the rising threat of Byzantium to the west. Neither of the independent Armenian kingdoms of the tenth century claimed Arsacid ancestry. Memories of Parthianness and Arsacid power still lingered, but shorn of their immediate political usefulness. The interpretation of Balkh as an Arsacid city and refuge for rebels slid from canon to archive.Footnote 88