Introduction

Reticulitermes flavipes (Kollar) (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) laboratory colonies were tracked for 11 years, beginning with initial alate pairings in 1993. These colonies are the oldest R. flavipes colonies of known age studied to date (see also Grube & Forschler, Reference Grube and Forschler2004). Periodic censuses have provided unprecedented long-term data regarding colony growth, lifespan of primary reproductives and numbers of secondary reproductives, or neotenics, generated after the loss of primary reproductives. This short communication supplements demographic data reported in Long et al. (Reference Long, Thorne and Breisch2003) and describes two distinct patterns of female neotenic production in queenless colonies.

Materials and methods

In 1993, 82 incipient R. flavipes colonies were established using pairs of sibling alates from three separate dispersal flights in Prince George's County, Maryland, USA. The establishment and initial incubation of these colonies is described in Thorne et al. (Reference Thorne, Breisch and Traniello1997). Rearing procedures and census protocols, along with population and caste ratio data gathered between 1995 and 2001, are documented in Long et al. (Reference Long, Thorne and Breisch2003). This communication provides colony census totals from 2003, primary and secondary reproductive tallies from 2004, and analyses of female neotenic numbers and sizes in 1999 and 2004.

Student's t-test determined whether significant differences existed between body weight and colony growth of queenright and queenless colonies and of colonies founded by alates from separate founding parent colony lines (lineage 1 and lineage 3). Among the queenless families, correlation between the number and wet weight of female neotenics and the length of time a colony had been without its primary queen was determined with Pearson's correlation coefficient. ANOVA evaluated the impact of colony size on neotenic production and the total number of neotenic females over time (SAS, 2002). The length of time a colony remained queenless was estimated by summing the years the queen was known to be deceased. For example, although one colony's queen died between the 1999 and 2001 censuses, 2001 was considered its first ‘queenless year’. Thus, it was considered queenless for four years (2001–2004), although this may have been an underestimate of up to two years.

Results

In 2003, lineages 1 and 3 were comparable by all metrics of individuals’ size and colony total; only king weights varied significantly (table 1). In 2001, at 8 years of age, 25 of 29 (86%) colonies retained their primary queens and 28 of 29 (97%) their primary kings (Long et al., Reference Long, Thorne and Breisch2003). Over the next three years, two additional queens (and one entire colony) were lost, dropping the queenright proportion to 22 of 28 (78%). Queenless and queenright colonies continued earlier trends, exhibiting equivalent total population, worker and soldier numbers, soldier weights and egg rank (table 2). Queenright colonies' previous development of significantly smaller workers and more abundant larvae subsided in 2003. Queenless (and one kingless) colonies continued to generate vastly more nymphs than queenright colonies (P=0.0003, t=7.77, df=23). It has been calculated that orphaned colonies are at greater risk of failure than complete nests; thus, nympal production is undertaken to maximize the survival of a colony's genes via alate dispersal (Lenz & Runko, Reference Lenz and Runko1993). In the current study, nymphs may have been produced in anticipation of an alate dispersal flight (Lenz & Runko, Reference Lenz and Runko1993) or subterranean budding event (Snyder, Reference Snyder1920).

Table 1. Demographic data (mean±SE) collected from two unrelated lineages of Reticulitermes flavipes colonies in 2001Footnote a, 2003 and 2004, at ages 8, 10 and 11 years old, respectively.

a 2001 data is reported with all other previous census data in Long et al. (Reference Long, Thorne and Breisch2003); it is provided here for added context.

Significant differences (P<0.05) are noted with an asterisk (*).

Table 2. Demographic data (mean±SE) collected from queenright and queenless Reticulitermes flavipes colonies in 2001 and 2003, at ages 8 and 10 years old, respectively.

a 2001 queenright n=17, queenless n=4.

b Unless noted, 2003 queenright n=19, queenless n=6.

c One recently orphaned colony was exluded from this computation, thus n=3.

Significant differences (P<0.05) are noted with an asterisk (*).

Neotenic individuals were identified in 25% of the 11-year-old colonies. All 28 of these colonies retained one of their primary parents: six contained a surviving king and one a surviving queen. Three of the queenless colonies lost their primary females prior to 1999, thus providing data from colonies whose egg production had been assumed by secondary reproductive females for at least 6 years. All neotenics in the six queenless colonies were female. The one kingless (but queenright) nest contained a female-skewed group of neotenics containing both genders.

The length of time a colony was queenless was independent of the number of female neotenics found during the censuses (r=0.15, P=0.6285) and had no significant effect on neotenic weights (P=0.686, F=0.19, df=1). Neotenic production was not significantly impacted by colony size (P=0.1658, F=20.94, df=6). Although the queenless colonies increased in total size between 1999 and 2003, the average number of female neotenics per colony decreased significantly over this period (P=0.0491, F=4.07, df=3). In 1999, queenless nests contained an average of 11.0 female neotenics (range 3–15); by 2004, the mean dropped to 5.7 (range 1–12) (fig. 1). Rather than being evenly distributed across these ranges, neotenics were produced in clusters of either a few, large individuals or numerous, small neotenic sisters (fig. 2). When between 1 and 3 sisters differentiated within a colony, their mean weight (15.8±2.0 mg) was significantly higher (P=0.049, F=7.13, df=1) than the average weight (8.1±2.1 mg) of sisters within groups of between 6 and 14 individuals. In fact, in both 2003 and 2004, the mean weight of the larger neotenics was not significantly different from the female primary reproductives in queenright colonies (P=0.1388, t=−1.53, df=24).

Fig. 1. Mean numbers of female neotenics in queenless Reticulitermes flavipes colonies. Error bars are standard errors of the mean. Significant differences (P<0.05) are indicted by different letters (LSM).

Fig. 2. Rank order of the total number of Reticulitermes flavipes female neotenics found during the 2001 and 2003 censuses combined. A neotenic cluster with >3 individuals was considered large, one with <3 was considered small.

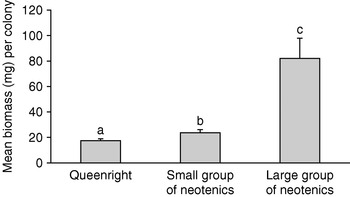

Regardless of group size, differentiation of female neotenics resulted in significantly greater female reproductive biomass per colony than in queenright colonies of equivalent age (P=0.0414, t=2.18, df=20). Primary queens comprised an average of 17.4±1.4 mg of biomass per colony. Weights of individual members of the small assemblies were statistically indistinguishable from primary queens, but the sisters combined for a mean of 23.5±2.7 mg of reproductive biomass per colony. Large clusters contained a mean aggregate biomass of 82.1±16.1 mg (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Mean female reproductive biomass in 10-year-old queenright and queenless Reticulitermes flavipes colonies. Error bars are standard errors of the mean. Significant differences (P<0.05) are indicted by different letters (LSM).

Discussion

These laboratory colonies provided a rare, and possibly unique, opportunity to monitor complete R. flavipes colonies for an extended period of time. Among 28 11-year-old colonies, 97% of kings and 72% of queens persisted. These laboratory cultures add novel data to Keller's (Reference Keller1998) compilation of ant and termite queen lifespans.

In the family, Rhinotermitidae, it is thought that multiple female neotenics differentiate simultaneously after queen loss; however, ‘multiple’ is rarely quantified. In the field, R. flavipes neotenics have been observed in quantities ranging from a couple, to a few dozen, to several hundred (Banks & Snyder, Reference Banks and Snyder1920; Snyder, Reference Snyder1920, Reference Snyder1954; Esenther, Reference Esenther1969; Howard & Haverty, Reference Howard and Haverty1980). With the exception of Howard & Haverty's (Reference Howard and Haverty1980) judgment that each of their field colonies contained at least 50,000 workers, none of the other sources estimated the population size or age of the sampled colonies. Thus, it is difficult to gauge a colony's expected neotenic output relative to its size and age.

In the current, 11-year study, no more than 15 female neotenics were ever found in a queenless colony. While these colonies increased in total size over time, the average number of female neotenics declined significantly between 1999 and 2004. These modest numbers of female neotenics may have been associated with small colony size (relative to field colonies) or spatial constraints of the laboratory nesting areas. However, the one kingless colony contained 75 (2001) and 78 (2003) female neotenics, suggesting that larger assemblies of neotenics are possible in these conditions.

The R. flavipes colonies, in this study, responded to the loss of a primary queen with two distinct strategies. Regardless of population size or the time spent as a queenless colony, female primaries were replaced by groups of either a few, large females or numerous, small females. Similar dual strategies have been observed in Coptotermes lacteus (Froggatt) (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) (Lenz & Runko, Reference Lenz and Runko1993) and Porotermes adamsoni (Froggatt) (Isoptera: Termopsidae) (Lenz, Reference Lenz, Watson, Okot-Kotber and Noirot1985). In several Nasutitermes species, there is a negative correlation between the number of primary queens in a polygynous association and the egg-laying capacity (as estimated by physogastry) of each queen (Thorne, Reference Thorne1984; Roisin & Pasteels, Reference Roisin and Pasteels1985, Reference Roisin and Pasteels1986a,Reference Roisin and Pasteelsb).

As predicted by numerous authors (Miller, Reference Miller, Krishna and Weesner1969; Nutting, Reference Nutting1970; Myles, Reference Myles1999), the replacement responses of these queenless R. flavipes colonies produced significantly more female reproductive biomass than queenright colonies of equal age. However, the larger clusters generated almost 250% more reproductive biomass than the small groups. Large field populations (estimated to be at least in the hundreds of thousands) have been attributed to the relatively substantial reproductive output of neotenics (Snyder, Reference Snyder1920, Reference Snyder1934, Reference Snyder1954; Pickens, Reference Pickens1932; Myles & Nutting, Reference Myles and Nutting1988; Grace, Reference Grace1996); however, the relatively young or small queenless colonies in this study grew on pace with their queenright counterparts.

This long-term analysis of 11-year-old, whole, laboratory-reared R. flavipes colonies provides demographic information regarding colony growth rate and longevity, lifespan of founding reproductives, and the response of colonies to the loss of founding queens. These fundamental elements of colony ontogeny and demography delineate patterns of growth, investment, reproduction and survivorship that may impact both intra- and extra-colony dynamics in these eusocial societies.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted in partial fulfillment of a doctoral degree at University of Maryland-College Park. Financial support was provided to C.E.L. by the Gahan Family Fellowship and the Jeffery P. LaFage Graduate Student Research Award.