Introduction

A large proportion of wheat grown in the UK is sown in the autumn, which has resulted in the crop becoming almost semi-perennial with no winter fallow period. This, in turn, has led to an increase in the overwintering insect fauna (Gair, Reference Gair1981). In Brittany, France, Rabasse & Dedryver (Reference Rabasse, Dedryver and Cavalloro1983) found that the hymenopterous parasitoid, Aphidius uzbekistanicus Luzhetski (Braconidae) regularly overwintered on its cereal aphid host, the grain aphid Sitobion avenae (F.) (Hemiptera: Aphididae), whilst around the same time, Vorley (Reference Vorley1986) suggested that in Britain, if weather conditions are favourable, adult parasitoids may overwinter and actively forage during this period (see also Lumbierres et al., Reference Lumbierres, Starý and Pons2007). Therefore, if both aphids and their natural enemies can overwinter within the crop, and if conditions are mild, aphids and/or parasitoids will then be well established when the wheat crop begins rapid growth in the following spring (Vickerman, Reference Vickerman1977a).

Many studies on the overwintering of cereal aphids and their natural enemies (e.g. Starý, Reference Starý1972, Reference Starý1978; Vickerman, Reference Vickerman1977a,Reference Vickermanb, Reference Vickerman1982) have treated wheat crops as truly annual. The crop, therefore, is assumed to be predominantly colonised by aphids and their natural enemies during the spring, when alate (winged) aphids and adult parasitoids migrate from grassland and uncultivated overwintering sites. However, if climatic conditions are suitable for the survival of aphid virginoparae (parthenogenetic forms) within the crop, overwintering aphids may also make a significant contribution to the following year's infestation by colonising the crop in the autumn (Vickerman, Reference Vickerman1977b; Vorley, Reference Vorley1986). Except after very cold winters, the infestation of aphids in spring, therefore, will consist of varying proportions of resident overwintering asexual aphids and winged immigrants (Lushai et al., Reference Lushai, Markovitch and Loxdale2002).

Since early parasitism may have a major effect upon subsequent aphid population size (Carter et al., Reference Carter, McLean, Watt and Dixon1980), it is important to monitor the aphid/crop ratio in early spring. The spring parasitoid population will be affected by: (i) parasitoid abundance in the previous year; (ii) mortality of overwintering parasitoids and/or aphids (either on the crop or on alternative hosts); and (iii) weather conditions in spring (Carter et al., Reference Carter, McLean, Watt and Dixon1980). All of the above factors should be taken into account when forecasting levels of parasitism in the spring aphid population.

Electrophoresis, enzyme and DNA-based, would seem to be a useful approach for assessing both percentage parasitism in overwintering aphid populations and for detecting parasitised as well as fungally-infected alatae, essential data for planning and implementing integrated pest management (IPM) strategies involving these agents in the field. Electrophoresis allows for rapid identification of parasitoids in their larval stages whilst avoiding the delay involved in rearing out adult parasitoids in the laboratory (Castañera et al., Reference Castañera, Loxdale and Nowak1983; Walton, Reference Walton1986; Walton et al., Reference Walton, Loxdale and Allen-Williams1990a,Reference Walton, Powell, Loxdale and Allen-Williamsb; see also Loxdale & Lushai (Reference Loxdale and Lushai1998) and Greenstone (Reference Greenstone2006) for enzyme- and DNA-based methods and Traugott et al. (Reference Traugott, Bell, Broad, Powell, Van Veen, Vollhardt and Symondson2008) for DNA-based methods of parasitoid detection). In addition, the presence of entomopathogenic fungi within live aphids can be detected using certain enzyme systems (Wilding et al., Reference Wilding, Mardell, Brookes and Loxdale1993), including carboxylesterases, as here described.

The present study, therefore, was performed to assess the efficacy of enzyme electrophoresis for testing levels of parasitism in winged S. avenae, as well as rates of parasitism and pathogenic fungal infection, by monitoring of carboxylesterase activity essentially using the electrophoretic key as described by Walton et al. (Reference Walton, Loxdale and Allen-Williams1990a).

Material and methods

Collection and electrophoretic testing

For electrophoretic detection of parasitised aphids, live winged pest and non-pest species were trapped using a 45-cm diameter propeller trap (Taylor, Reference Taylor1955) operated at Rothamsted (51.8°N, 0.37°W) from 15 April to 21 November, 1983 (although, for this particular study, winged S. avenae were only caught and tested between 23 May to shortly after the 14 August, 1983). This trap was placed near to the Rothamsted Insect Survey (RIS) 12.2-m high ‘tower’ suction trap at the meteorological station on the Rothamsted estate (330 ha), which is situated within mixed farmland often sown with cereal crops (see map in Anon, 1988). Since such winged aphids may carry parasitoids when leaving the crop, as well as when colonising it, they were sampled throughout the growing season.

The trap, situated 1.5 m above ground level, was sited and operated as described by Plumb (Reference Plumb1976). Prior to electrophoretic testing, all live S. avenae identified within the daily suction trap samples and used for the parasitism/fungal infection analyses were first tested by Roger Plumb and co-workers at Rothamsted for transmission of barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV) to healthy oat plants as part of a long-term monitoring scheme then operating (see Plumb, Reference Plumb1971). Only those aphids remaining alive after two days following BYDV testing were assayed for esterase activity using the electrophoretic methods and biochemical ‘keys’ previously described by Loxdale et al. (Reference Loxdale, Castañera and Brookes1983), Walton (Reference Walton1986) and Walton et al. (Reference Walton, Loxdale and Allen-Williams1990a,Reference Walton, Powell, Loxdale and Allen-Williamsb). Although aphids were collected on a daily basis, records were grouped to give a weekly assessment of percentage parasitism and fungal infection.

Results

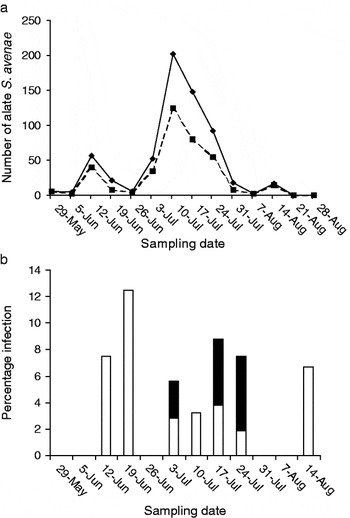

A total of 627 winged S. avenae were caught over the period 23 May–13 November, 1983; of these, around 61% (380 individuals) survived BYDV testing and were subsequently assayed for parasitism (table 1, fig. 1a, b). (The table is additionally presented so that the contribution of infection by both parasitoids and fungi for each sampling period can be more readily discerned; here, only 625 aphids are shown as recorded up to 14 August, 1983, see below.)

Fig. 1. (a) Number of live alate S. avenae trapped for enzyme electrophoretic testing (-⧫-, no. alates trapped; –▪– no. alates tested for parasite/fungal infection). (b) Percentage of alate S. avenae parasitised by A. ervi/A. rhopalosiphii or fungi. Dates on the x-axis refer to the last day of each weekly sampling period (▪, % fungal infection; □, % parasitism).

Table 1. Live winged S. avenae trapped for electrophoretic testing in 1983.

From 6 to 12 June, there was a small peak in total alatae caught and a second much larger peak between 4 and 10 July (table 1, fig. 1a). From 26 June to 10 July, a rapid rise in aphid numbers occurred, which was followed by an equally rapid decline from 10 July to 14 August. Most aphid flight activity ceased thereafter, with only two individuals caught after this date, one of which survived BYDV testing, but did not contain a parasitoid larva or fungus (data not shown). Infection by fungal pathogens (Powell & Pell, Reference Powell, Pell, van Emden and Harrington2007) gave a characteristic banding pattern consisting of a diffuse red background to carboxylesterase (EST)-1 and -2 of the host banding pattern, together with a single well-resolved black band in the region of the host EST-7 (Loxdale et al., Reference Loxdale, Castañera and Brookes1983).

The number of aphids surviving BYDV testing showed a similar pattern to the total alate catch (table 1, fig. 1a), with a maximum of 125 individuals tested between 4 and 10 July. Total percentage alatae attacked by both parasitoids and fungi was consistently low (fig. 1b), averaging only ∼5%, with a maximum of about 13% between 13 and 19 June. The only parasitoid species detected belonged to the Aphidius ervi (Haliday)/Aphidius rhopalosiphi (De Stephani Perez) group previously described by Walton et al. (Reference Walton, Loxdale and Allen-Williams1990a; see also Powell, Reference Powell1982). Infection by entomophthoralean fungal pathogens was only detected between 27 June and 24 July.

Parasitism reached its highest level between 13 and 19 June, whilst fungal infection only became apparent later in the season. Between 27 June and 24 July, fungal pathogens were found to be much more common in the alate S. avenae population and appeared to infect at least as many as those attacked by A. ervi/rhopalosiphi.

Discussion

As shown in this study, alate S. avenae carried developing primary braconid hymenopterous parasitoids within them from the beginning of June to mid-August and were sometimes also infected by fungal pathogens from 27 June to 24 July, with most aphids trapped during the weeks ending 12 June and 10 July. The first peak of aphids probably corresponds to spring migration from overwintering populations into the growing crop (Dean & Luuring, Reference Dean and Luuring1970), whilst the second much larger peak probably represents alate migration in response to crop senescence. Besides transport by alate aphids, adult parasitoids are of course able to actively fly and move into cereal crops themselves. This migration will contribute to percentage parasitism, although it was not currently investigated.

The relatively small number of aphids caught at the peak flights reflects a differential sampling ability of the small 1.5-m high suction trap vs. the standard 12.2-m high Rothamsted suction trap (Macaulay et al., Reference Macaulay, Tatchell and Taylor1988). Thus, the magnitude of the difference in the first peak (week starting 13 June: 1.5=∼21; 12.2=126) is only around one fifth (∼17%) of that expected as it is too for the major peak in flight activity (week starting 4 July: 1.5=∼200; 12.2=1054, i.e. 19%; RIS data). In this case, the 1.5-m trap appears to be capturing relatively far fewer alates than the larger trap. Hence, this likely sampling difference between such traps must be noted when comparing the catches caught during the migratory phase of the aphid and contrasting the molecular ecological results thereby obtained. Such a difference probably reflects the fact that most migrating aphids are normally flying higher than 1.5 m above the ground (mainly first 30 m or so), especially in more turbulent air conditions (Johnson, Reference Johnson1954).

Since, as aforementioned, the spring migration involves movement of S. avenae from overwintering sites into the crop (Dean & Luuring, Reference Dean and Luuring1970; Dean, Reference Dean1974, Reference Dean1978), the present results clearly show that some of these alatae carried parasitoids, though only the primary parasitoids, A ervi and/or A. rhopalosiphi, were detected. The relatively low percentage parasitism may be due to the preference of A. rhopalosiphi for earlier aphid instars, as reported by Shirota et al. (Reference Shirota, Carter, Rabbinge and Ankersmit1983) or because parasitised aphids are simply less capable of migration or due to inclement overwintering conditions. If parasitoids attack aphid instars I–II, then the combined effects of inhibited wing-bud development, the juvenilising effect of parasitism (Johnson, Reference Johnson1959) and death of some aphids during instar IV will result in a comparatively small proportion of parasitised aphids forming alatae. However, if winter weather conditions are unfavourable for the survival of anholocyclic (obligate asexual) S. avenae populations on the crop on which parasitoids could overwinter, migrating aphids (spring migrants) will be an important early source of parasitoids, even though the level of parasitism may be comparatively low. It has also recently been shown in field studies of S. avenae-A. rhopalosiphi that parasitism per se can have a significant effect on the number of aphids surviving the winter and into early Spring (Legrand et al., Reference Legrand, Colinet, Vernon and Hance2004). The low percentage parasitism here recorded is less likely a result of winter conditions, since the winter of 1982/1983 was generally mild in the south-east of England (http://www.london-weather.eu/category.46.html), which should have encouraged both live aphid and parasitoid survival.

Migration undoubtedly allows parasitoids to disperse rapidly as, for example, in the case of the primary parasitoid, Aphelinus varipes (Förster), following its introduction for control of the greenbug aphid, Schizaphis graminum (Rondani), and the corn leaf aphid, Rhopalosiphum maidis (Fitch), on sorghum in the USA (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Coles, Wood and Eikenbary1970). Parasitised alate aphids may also make a significant contribution to the number of parasitoids entering the crop, as noted by Chua (Reference Chua1977), who observed that, in cruciferous agroecosystems in England, mean percentage parasitism of alate cabbage aphids, Brevicoryne brassicae (L.), by the primary parasitoid Diaeretiella rapae (M'Intosh) (measured by live rearing) was around 25% in both 1974 and 1975. Differences in the dispersal and colonising abilities of the primary braconid parasitoids, Praon exoletum (Nees) and Trioxys complanatus (Quilis), were thought by Force & Messenger (Reference Force and Messenger1968) to occur because P. exoletum is carried more frequently by alate hosts.

A delay between crop colonisation by cereal aphids and their subsequent parasitism may result in a large aphid population in which high levels of parasitism only occur when the aphid population is in decline (Starý, Reference Starý1978). Therefore, early establishment of parasitoids in the field is probably important in limiting aphid population size. Starý (Reference Starý1972) considered reservoirs of aphid parasitoids within the agroecosystems to be an important factor for aphid control. However, this depends on the ability of parasitoids to readily switch hosts, which in turn depends not only on the genetics of individual species (Hopper et al., Reference Hopper, Roush and Powell1993) but may even involve morphologically similar/identical cryptic species, as found in Aphidius wasps attacking pea, cereal and nettle aphids (e.g. Powell & Wright, Reference Powell and Wright1988; Pennacchio et al., Reference Pennacchio, Digilio, Tremblay and Tranfaglia1994), each with a significant degree of host adaptation/ecological specialisation (hence militating against Starý's idea).

In northern France, Robert (Reference Robert1979) found parasitism of alate potato aphids, Aulocorthum solani (Kaltenbach), as measured by aphid dissection, to be 31.8%, 7.7% and 35.7% in 1967, 1968 and 1969, respectively. Gardner (Reference Gardner1982), after dissecting 750 alate cereal aphids, S. avenae and Metopolophium festucae (Theobald), from two British sampling sites in 1981, found 8.7% and 4.8% of aphids were parasitised with both species parasitised to the same extent. These results are similar to those of Jones & Dean (Reference Jones and Dean1975), who reported peak parasitism (13.8%) of emigrating alate S. avenae in Britain in the week ending 12 July, 1970. The present study revealed a maximum of 12.5% Aphidiid wasp parasitism during aphid winged migration (i.e. 13–19 June) although this was in a very small sample of only eight individuals. Walton et al. (Reference Walton, Powell, Loxdale and Allen-Williams1990b), by way of contrast, found using enzyme assays, ∼50% parasitism by six primary parasitoids of S. avenae collected from spring wheat in Hertfordshire early in the growing season, whilst Traugott et al. (Reference Traugott, Bell, Broad, Powell, Van Veen, Vollhardt and Symondson2008), using DNA-based assay methods, detected ∼19% parasitism over a 12-week period in S. avenae infesting wheat in Warwickshire, UK and attacked by a suite of 11 parasitoids, including primary and secondary species, i.e. hyperparasitoids. Aphidius rhopalosiphi, Aphidius picipes (Nees) and Ephedrus plagiator (Nees) could be detected in 8.2%, 3.5% and 3.5%, respectively, of all aphids tested. At about the same time (2001–2005), Feng et al. (Reference Feng, Chen, Shang, Ying, Shen and Chen2007), collecting large numbers of alate peach-potato aphids, Myzus persicae (Sulzer), using yellow-plus-plant traps on the top of a six-storey building in an urbanised area of China (Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province) and, thereafter, individually rearing the aphids in a laboratory for ≥7 days, found 52.9% parasitism by the primary parasitoids Aphidius gifuensis (Ashmead) and 47.1% by D. rapae. In a similar study, also performed in China (Yunnan Province), and involving similarly trapped winged B. brassicae, Lipahis erysmi (Kaltenbach) and M. persicae, around 3% were infected (mummified) by A. gifuennsis, D. rapae, E. plagiator and Aphelinus mali (Haldeman) after survival of ∼5 days (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Feng, Chen and Liu2008).

Our results, besides showing that primary Aphidiid wasp parasitoids imported by alate S. avenae were exclusively A. ervi and/or A. rhopalosiphi, also revealed a later burst of fungal infection, peaking at 5.6% for the week ending 24 July, and affecting only those alatae trapped when leaving the senescing crop late in the summer (contrasting with ∼30% winged aphids dying after 2.5 days and attacked by a variety of obligate and non-obligate aphid fungal pathogens representing ten species in the aforementioned study of Feng et al. (Reference Feng, Chen, Shang, Ying, Shen and Chen2007) and ∼19% after 2.3 days, also by ten species, in the study by Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Feng, Chen and Liu2008)). In England, Dean & Wilding (Reference Dean and Wilding1971, 1973) found very few fungal-infected aphids until mid-July, with maximum attack at the end of that month. Our findings thus support these earlier findings by Dean & Wilding and suggest that fungal infection develops in the crop and is, therefore, unlikely to affect those alatae entering at the start of the growing season. However, when assessing mortality due to parasitoids and/or fungi, mutual interference during development should be taken into account if both are present in the same aphid (Powell et al., Reference Powell, Wilding, Brobyn and Clark1986). These authors showed that fungal attack can significantly reduce parasitoid survival. The fact that only two species of parasitoid were found in our study, whereas many more are known from field studies of cereal aphids, including primary and secondary species (Traugott et al., Reference Traugott, Bell, Broad, Powell, Van Veen, Vollhardt and Symondson2008), is more likely to be somehow related to the ecological/environmental circumstances at the time of sampling rather than a methodological one, since using carboxylesterases, a range of taxonomically diverse species can be detected electrophoretically, as shown by Walton et al. (Reference Walton, Loxdale and Allen-Williams1990a; see also Castañera et al., Reference Castañera, Loxdale and Nowak1983).

In the present work, estimates of percentage parasitism were thought to be comparable to live-rearing methods, since, in our study, the aphid hosts were kept alive for a further two days on oat seedlings during BYDV testing. This period should have allowed for continuing development of parasitoid eggs and very early larval stages within individual aphids, which are not yet detectable using enzyme electrophoretic methods, i.e. 1st instar A. rhopalosiphi larvae are only detectable electrophoretically >156 h (Walton et al., Reference Walton, Loxdale and Allen-Williams1990a; see below), but are probably detectable at much earlier stages of development using highly sensitive PCR-based methods involving specific DNA primers (Traugott et al., Reference Traugott, Bell, Broad, Powell, Van Veen, Vollhardt and Symondson2008). Since aphids which died during BYDV testing were not examined for parasitism, it was not possible to assess any effects of parasitism upon the proportion of aphids surviving the BYDV testing. Nevertheless, as with other aphid species, e.g. the spotted alfalfa aphid Therioaphis trifoli f. maculata (Monell) (Force & Messenger, Reference Force and Messenger1968) and S. graminum (Kelly, Reference Kelly1917; Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Coles, Wood and Eikenbary1970), parasitism of alate S. avenae appears to facilitate parasitoid dispersal. Furthermore, if weather conditions are unsuitable for survival of overwintering aphids in autumn-sown crops, spring immigration of alate-borne parasitoids, together with movement of adult parasitoids, assumes a more important role in establishing spring parasitoid populations.

In conclusion, as here shown, enzyme electrophoresis has proved to be a useful approach in the study of alate aphid parasitism by two primary parasitoid wasp species and following pathogenic infection by entomophthoralean fungi. This is because it significantly speeds up detection of both biological control agents (the latter as a functional group rather than as defined individual taxa) whilst, at the same time, permitting identification of the parasitoid larvae without recourse to dissection of aphids and use of taxonomic keys based on morphological criteria of the parasitoid larvae themselves (that is, once their enzyme banding profiles have been duly established: Walton, Reference Walton1986; Walton et al., Reference Walton, Loxdale and Allen-Williams1990a). However, what is still not clear from our data is the differential level of single or dual infection by parasitoids and fungal pathogens, although, during the period when the latter were detected (27 June–24 July), the average levels per control agent are not dissimilar at around 4–5% (![]() =∼5.5 (n=7) for parasitoids vs.

=∼5.5 (n=7) for parasitoids vs. ![]() =∼4.5 (n=3) for fungal pathogens; table 1). This may be contrasted with the work of Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Feng, Chen and Liu2008) where, among the trapped alate aphids, ∼3% were infected by parasitoids and ∼19% with fungi.

=∼4.5 (n=3) for fungal pathogens; table 1). This may be contrasted with the work of Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Feng, Chen and Liu2008) where, among the trapped alate aphids, ∼3% were infected by parasitoids and ∼19% with fungi.

As with the DNA assays, by virtue of its speed and comparative simplicity (and here it may even have an edge over the DNA methods), the enzyme approach could usefully be incorporated into a monitoring system (e.g. BYDV, insecticide resistance) to provide an estimate of parasitism and fungal infection in migrating winged aphids. Such information, coupled with data on aphid and parasitoid overwintering, is essential for predictive models of parasitoid impact on aphid populations (e.g. see Vorley, Reference Vorley1983) for use of such biological control agents in IPM scenarios where the aim is to reduce the impact of pesticides in the environment (e.g. Dean et al., Reference Dean, Dewar, Powell and Wilding1980). Whilst in the present work, the reduced sensitivity of the enzyme assay to detect parasitoid eggs may not have been a significant problem (because the aphids tested were probably old enough for the eggs and young larvae to have developed to a point where they were detectable using the enzyme electrophoretic methods employed), it is likely to somewhat underestimate true percentage parasitism (allowing for the effects of small and, hence, unrepresentative sampling size, as well as the slow parasitoid developmental time in braconid species such as A. rhopalosiphi) in direct field-collected and tested aphid assays, especially during periods of parasitoid population growth (Walton et al., Reference Walton, Powell, Loxdale and Allen-Williams1990b).

As well as practical applications, the data as described here has interesting fundamental ramifications as well. The fact that winged aphids can passively carry parasitoids at early stages of development as well as fungal pathogens (effectively carrying their and perhaps their descendant's ‘death sentence’ with them, assuming they have a few healthy offspring before being overcome) may perhaps explain the persistence of parasitoids in dual aphid-parasitoid metapopulation scenarios, such as that between the specialist tansy-feeding aphid, Metopeurum fuscoviride Stroyan, attacked by its specialist primary braconid parasitoid, Lysiphlebus hirticornis Mackauer (Nyabuga et al., Reference Nyabuga, Loxdale, Heckel and Weisser2010). It may perhaps also directly affect the population genetics of the two key insect players in the tritrophic plant-aphid-parasitoid system, by introducing parasitoids and pathogens to hitherto unattacked aphid colonies and thereby eliminating rare aphid genotypes, more especially during the periods when such colonies are small, as in Spring. Lastly, whilst enzyme electrophoresis as here used was not employed specifically to detect hyperparasitism, potentially there is no reason why this cannot be performed, once suitable biochemical ‘keys’ are produced. With PCR-methods, such hyperparasitism is detectable in around 4% of aphids screened and represents a “significant hyperparasitoid pressure on some parasitoid species” (Traugott et al., Reference Traugott, Bell, Broad, Powell, Van Veen, Vollhardt and Symondson2008; see also Chua, Reference Chua1977). Hence, hyperparasitoids, which can, as with their primary parasitoid hosts and in turn their aphid hosts, persist late into the field season (e.g. Chua, Reference Chua1977; Höller, Reference Höller1990), may provide a further death sentence, this time for the primary parasitoids carried within the living airborne aphids.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Roger Plumb and co-workers for their assistance in collecting winged aphids, Cliff Brookes for technical assistance, Norma Nitschke for advice concerning Excel, Dr Michael Traugott for kindly encouraging us to publish this data set and the two referees, Dr James Bell and an anonymous referee, for their very helpful comments (including data from the RIS survey courtesy of James Bell) which have greatly improved the manuscript.