Introduction

Tetrastichus giffardianus Silvestri is a gregarious koinobiont endoparasitoid that oviposits in the larvae of several species of tephritids, including pest species (Fernandes et al., Reference Fernandes, Araujo, Souza, Souza and Nunes2019a). This parasitoid was introduced into Hawaii in 1912 from West Africa for biological control of the Mediterranean fly Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann) and quickly became established throughout the Hawaiian Islands (Purcell et al., Reference Purcell, Nieuwenhoven and Batchelor1996). Due to this successful introduction, T. giffardianus was later redistributed to several countries in Central and South America for the biological control of fruit flies (Ovruski et al., Reference Ovruski, Aluja, Sivinski and Wharton2000; Mohamed et al., Reference Mohamed, Ramadam and Ekesi2016).

It is noteworthy that the main advantage of using T. giffardianus in augmentative biological control is due to the high proportion of females among the offspring. Moreover, T. giffardianus females penetrate the fruit to lay eggs in the larvae, which allows the direct attack to larvae that had escaped from Opiinae parasitism, since tephritid larvae tend to be located deeper in larger fruit (Garcia and Ricalde, Reference Garcia and Ricalde2013).

In the Southeast of Brazil, T. giffardianus was introduced during the 1930s for the control of C. capitata in citrus orchards (Citrus spp.). However, T. giffardianus was not recaptured in the region where it was initially released (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Araujo, Guimarães, Nascimento and Lasalle2005). Interestingly, 60 years after its introduction, T. giffardianus has been reported in other regions of Brazil, particularly in the Northeast (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Araujo, Guimarães, Nascimento and Lasalle2005; Araujo et al., Reference Araujo, Fernandes, Silva, Ferreira and Costa2015).

Many failures in the establishment of natural enemies are probably due to problems of adaptation by the species to the climatic conditions of the environment where they were released (Loni, Reference Loni1997). Temperature is one of the most important factors directly affecting fertility, sex ratio, longevity, and life cycle duration at different insect developmental stages (Wiman et al., Reference Wiman, Walton, Dalton, Anfora, Burrack, Chiu, Daane, Grassi, Miller, Tochen, Wang and Ioriatti2014; Poncio et al., Reference Poncio, Nunes, Gonçalves, Lisboa, Manica-Berto, Garcia and Nava2016; Groth et al., Reference Groth, Loeck, Nornberg, Bernardi and Nava2017; Stacconi et al., Reference Stacconi, Panel, Baser, Pantezzi and Anfora2017). Therefore, knowledge on the temperature requirements for the development of different insect species allows for the construction of models of occurrence and survival, both for the prediction of the necessary conditions for their establishment in a new environment and also for their rearing and release in biological control programs (Nyamukondiwa et al., Reference Nyamukondiwa, Weldon, Chown, le Roux and Terblanche2013).

The parasitoid T. giffardianus is a potential candidate for the control of C. capitata in northeastern Brazil. Thus, it is paramount to understand how temperature affects its biology in order to improve the chance for a successful establishment in the environments where the parasitoids will be released. However, information on the effect of temperature on the biology of this parasitoid is scarce. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of different constant temperatures on the biology and development of T. giffardianus during the egg-adult period on C. capitata larvae and construct a fertility life table.

Materials and methods

The populations of C. capitata and T. giffardianus used in this study were reared in climate-controlled rooms at a temperature of 25 ± 2°C, relative humidity of 70 ± 10%, and a photoperiod of 12:12 h (L:D) at the Laboratory of Applied Entomology of the Universidade Federal Rural do Semi-Árido (UFERSA), in Mossoró, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

The C. capitata flies were kept in semitransparent plastic cages (27.6 × 33.1 × 48.7 cm3) (SANREMO®, Esteio, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil) with one side lined only with voile fabric for oviposition and one side with a sleeve-shaped screen to allow handling. Petri dishes (10 cm diameter × 1.5 cm height) containing food and 250-ml plastic bottles with absorbent tape (Spontex®, Ilheús, Bahia, Brazil) were placed inside the cage. The adult diet consisted of a 1:4 mixture of Brewer's yeast and sugar. Eggs were collected in a water-filled container placed under the fabric side of the cages. Fluorescent bulbs were placed close to the oviposition fabric to attract females. Every 24 h, eggs collected in the plastic tray were transferred to a beaker (200 ml), and with the aid of a syringe (3 ml), 0.5 ml of eggs were collected and placed in a tray (250 ml) containing artificial diet (Albajes and Santiago-Alvarez, Reference Albajes and Santiago-Alvarez1980). This volume of eggs produced approximately 5000 larvae and/or pupae.

Larvae were fed the artificial diet until reaching maximum development. Puparia were collected and placed in a new breeding cage. The cage with the oldest insects was replaced by a new cage weekly for the continuous rearing of C. capitata.

For T. giffardianus rearing, tropical almond (Terminalia catappa) fruits infested by C. capitata larvae and parasitized by T. giffardianus were collected in the urban area of Mossoró (5°11′26″S and 37°20′17″W; elevation 20 m). Fruits were taken to the laboratory and placed in plastic trays (26 × 40 × 10 cm3 [l × w × h]) with a 4-cm layer of fine vermiculite and covered with voile. After 7 days, the vermiculite was sieved to obtain the puparia, which were transferred to Petri dishes (10 cm diameter × 1.5 cm height) containing a thin layer of moistened fine vermiculite. The emerged adults of T. giffardianus were reared according to the methodology described by Fernandes et al. (Reference Fernandes, Souza, Alves, Felipe and Araujo2019b). The parasitoids were reared in a metal-acrylic cage (30 × 30 × 30 cm3 [l ×w × h]) with an opening (10 cm width × 10 cm length) at the top covered with voile for ventilation and a sleeve-shaped screen on the side to allow handling. The parasitoids were fed with granulated sugar in a Petri dish (4 cm diameter × 1.5 cm height) and pure honey brushed on a piece of paper. Water was supplied from a 50-ml plastic bottle with absorbent tape (Spontex®). For parasitoid reproduction, third instar larvae of C. capitata were exposed to parasitoids in a 1000 ml plastic container (15 cm diameter × 9 cm height) for a period of 24 h. After exposure to parasitoids, the larvae were transferred to Petri dishes containing a diet to complete their development, and the pupae were placed in a plastic container (9.5 × 9.5 × 1.6 cm [l × w × h]) with slightly moistened vermiculite until the emergence of flies and/or parasitoids.

The identification of the parasitoids was carried out by Dr Valmir Antonio Costa at the Instituto Biológico, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil. Voucher specimens were deposited at the parasitoid Hymenoptera collection at the same institution.

Effect of temperature on the development of the immature stages of T. giffardianus

Initially, third instar larvae of C. capitata were exposed to parasitism by T. giffardianus at 3 days of age for a period of 24 h. Larvae were exposed to parasitoids in a 1000 ml plastic container (15 cm diameter × 9 cm height) inside the cage and held in a climate-controlled room at 25 ± 2°C, 60 ± 10% relative humidity, and 12:12 h (L:D) photoperiod. After the exposure period, larvae were individually placed in polystyrene tubes (2.6 cm diameter × 6.1 cm height) (Injeplast®, São Paulo, Brazil) containing moistened vermiculite for pupation and closed with plastic film until the emergence of the flies and/or parasitoids. Afterwards, the polystyrene tubes were placed in climate-controlled chambers at constant temperatures of 15, 20, 25, 30, and 35 ± 1°C, 70 ± 10% relative humidity, and 12:12 h (L:D) photoperiod. Observations were made daily to record the date, number, and sex ratio of the emerged parasitoids.

Based on emergence data, the average duration of the egg-adult period of T. giffardianus was calculated for each temperature tested. The experiment was carried out in a completely randomized design with five treatments (temperatures) and 100 replicates, each larvae-pupae of C. capitata was considered as a replicate.

Effect of temperature on biology and demographic parameters of T. giffardianus adults

Newly emerged adults of T. giffardianus (<24 h old) were paired in plastic cages (20 × 20.5 × 15.5 cm3 [l × w × h]) with an opening (10 cm width × 10 cm length) covered with voile fabric on one side to allow aeration and a sleeve-shaped screen on another side to allow handling. The parasitoids were fed pure honey brushed on paper (5 cm width × 5 cm length). Water was supplied from a 50 ml plastic bottle with absorbent tape (Spontex®). The pairs were kept in a climate-controlled chamber at constant temperatures of 15, 20, 25, 30, or 35 ± 1°C, 70 ± 10% relative humidity, and 12:12 h (L:D) photoperiod.

Throughout the experiment, seven third-instar larvae (±10 days old) of C. capitata were offered daily to each female for a period of 24 h. Larvae were offered inside fruits (T. catappa) that had been infested manually using tweezers. After the exposure period, larvae were placed in 50 ml plastic cups containing artificial diet, and the puparia were subsequently placed in individual polystyrene tubes (2.6 cm diameter × 6.1 cm height) (Injeplast®) containing slightly moistened vermiculite and closed with plastic film until the emergence of adults (flies or parasitoids).

The number of emerged flies and parasitoids was evaluated daily. The puparia that remained intact were dissected to check for the presence of flies or parasitoids to determine the true parasitism rate. The dissection was performed using a scalpel and tweezers under a stereoscopic microscope (Motic) at 80 × magnification.

The following parameters were quantified: number of offspring (NO), sex ratio (SR), percent parasitism (P), and longevity of males and females. The number of offspring was obtained using the equation: NO = number of emerged parasitoids + number of non-emerged parasitoids. The sex ratio was calculated using the equation: SR = (number of females)/(number of females + number of males). The parasitism and daily parasitism were obtained using the equation: P (%) = (number of parasitized pupae)/(total number of larvae exposed to parasitism) × 100. The cumulative parasitism was obtained using the sum of daily parasitism.

Fertility life table

The following parameters of the life fertility table were estimated: the net reproductive rate (R o), the intrinsic growth rate (r m), mean interval between generations (mean generation time [MGT]), the population doubling time (DT), and the finite rate of population increase (λ). The r m was estimated according to the equation: ∑e−rxlxmx = 1, Where x is female age in days, lx is the age-specific survival rate, and m x is the number of daughters produced per female alive at age x. The R o = ∑ lxmx; MGT in days is given by MGT = ln R o/r; DT in days is DT = ln (2)/r; and λ = er (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Kaçar, Biondi and Daane2016a).

The experiment had a completely randomized design with five treatments (temperatures) and 20 replicates, each replicate consisting of one T. giffardianus pair. The data obtained from the biological parameters of immature and adult were used to construct a fertility life table.

Statistical analysis

The data were tested for normality with the Shapiro Wilk test and for homoscedasticity with the Hartley test, and the independence of residuals was assessed by a graphical analysis. The data were subjected to analysis of variance (P ≤ 0.05). If statistical significance was found, the effects of the temperature were assessed with Tukey's test (P ≤ 0.05). The longevity (days) of females and males was analyzed by constructing survival curves using the Kaplan-Meier estimator. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test conducted with R v3.4.4 (R Development Core Team, 2018). The fertility life table parameters were estimated with the Jackknife technique (Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Ingersoll, McDonald and Boyce1986) using ‘Lifetable.sas’ (Maia et al., Reference Maia, Luiz and Campanhola2000) in the SAS system environment.

Results

Effect of temperature on the development of immature stages of T. giffardianus

Among the temperatures studied, complete development of the immature stages occurred at 20, 25, and 30°C. The total preimaginal development time was 41 days at 20°C, and the minimum was 11 days at 25°C, with the mean development time ranging from 33.14 ± 1.72 days at 20°C to 16.65 ± 1.75 days at 30°C (fig. 1). The mean development time of T. giffardianus was prolonged when the temperature was lowered.

Figure 1. Mean duration of the egg-adult development period of Tetrastichus giffardianus in Ceratitis capitata larvae maintained at different temperatures with a relative humidity of 70 ± 10% and a photoperiod of 12:12 h (L:D). Columns with different letters are significantly different based on the Tukey test (P ≤ 0.05).

Effect of temperature on biology and demographic parameters of T. giffardianus adults

The mean number of offspring per female was significantly affected by temperature (F = 26.97; df = 2; P = 0.001) (table 1). The number of offspring produced by T. giffardianus females decreased as females aged. The maximum number of offspring per female (140) was recorded at 25°C and the minimum number (3) at 35°C.

Table 1. Mean number of offspring (emerged and non-emerged), mean rate of parasitism (percent) and sex ratio of Tetrastichus giffardianus maintained at different temperatures with a relative humidity of 70 ± 10% and a photoperiod of 12:12 h (L:D)

a Values followed by the same letter in the column are not significantly different based on the Tukey test (P ≤ 0.05).

b Values followed by the same letter in a column do not differ from each other by the comparison test of proportions (P ≤ 0.05).

The highest mean parasitism rates were recorded at 25 and 30°C (table 1). The sex ratio of the emerged parasitoids was biased towards females at all temperatures studied, with the highest proportion of females recorded at 20°C (table 1).

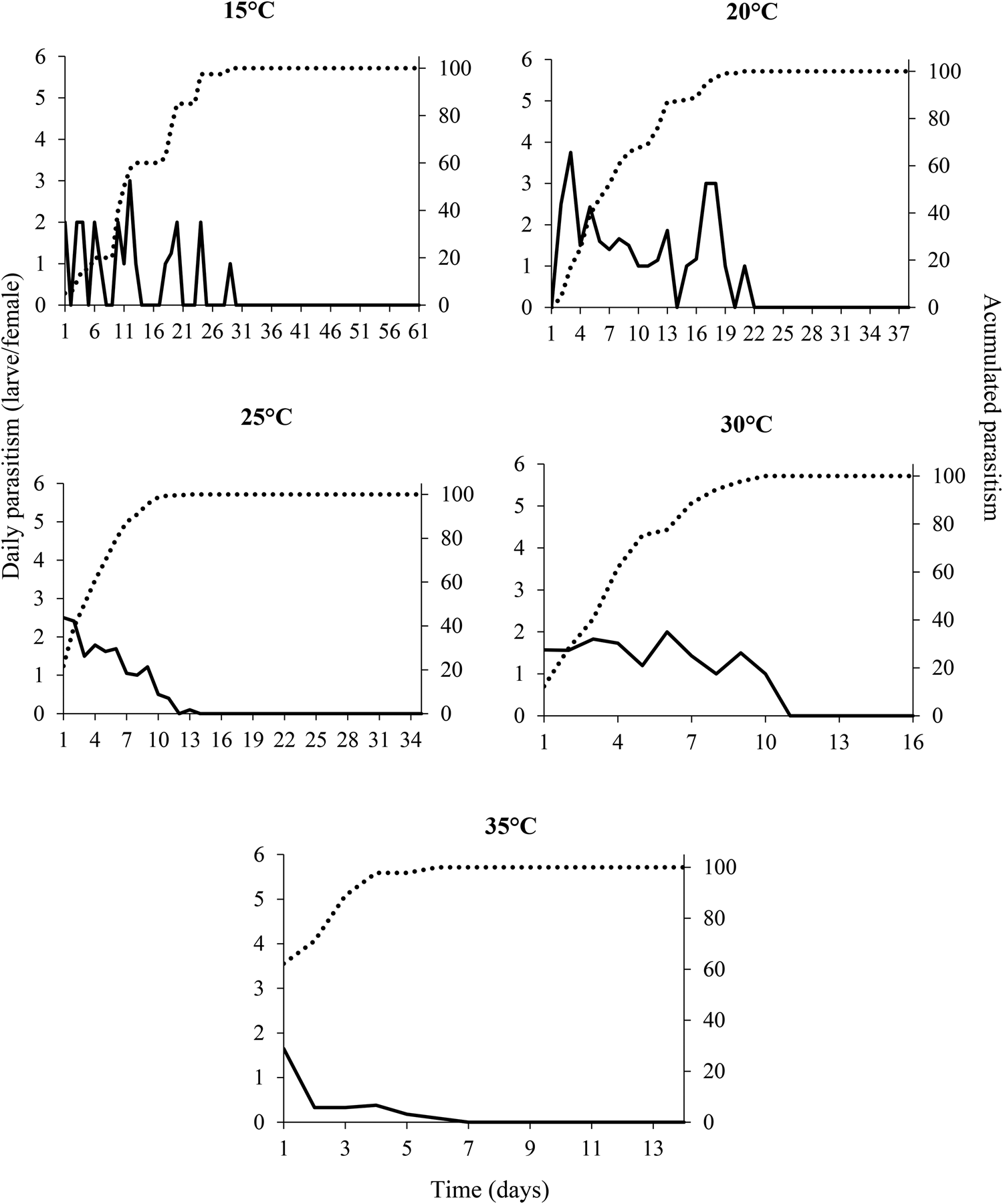

The daily parasitism rate at all temperatures was variable and did not exceed six larvae per day for the entire life of the females (fig. 2). The peak levels of parasitism were 3, 3.8, 2.5, 2, and 1.7 larvae per day at the temperatures of 15, 20, 25, 30, and 35°C, respectively (fig. 2). These parasitism peaks occurred between 1 and 12 days after.

Figure 2. Daily (__) and cumulative (….) rates of parasitism by Tetrastichus giffardianus on larvae of Ceratitis capitata at different temperatures (15, 20, 25, 30, and 35°C) with a relative humidity of 70 ± 10% and a photoperiod of 12:12 h (L:D).

The cumulative parasitism rate of 80% was reached on day 19, 12, 7, 7, and 3 of life of the females, which was inversely proportional to the temperatures of 15, 20, 25, 30, and 35°C, respectively (fig. 2).

Differences in the longevity of parasitoids were observed both in males (X 2 = 144; df = 4; P = 0.000) (fig. 3a) and females (X2 = 92.6, df = 4; P = 0.000) (fig. 3b) at different temperatures. The mean life span of males ranged from 50.3 days (15°C) to 8.4 days (35°C) (fig. 3a). In females, longevity ranged from 30.9 days (15°C) to 8 days (30°C) (fig. 3b). Males lived longer than females at all temperatures studied, except at 25°C.

Figure 3. Male (A) and female (B) survival curves of Tetrastichus giffardianus maintained at different temperatures (15, 20, 25, 30, and 35°C) and relative humidity of 70 ± 10% and a photoperiod of 12:12 h (L:D). Curves followed by the same letters, for each sex, are not significantly different using the log-rank test (Tms = mean survival time).

Fertility life table

Temperature significantly influenced (F = 38.97, df = 2, P = 0.0001) the net reproductive rate (R o) of T. giffardianus (table 2). Females maintained at 20 and 25°C showed an increase in the R o of 189.6 and 326.7%, respectively, when compared with females maintained at 30°C. The intrinsic rate of increase (r m) was significantly affected by temperature (F = 11.34, df = 2, P = 0.0001) and the maximum r m was recorded at 25°C.

Table 2. Parameters from the fertility life table of Tetrastichus giffardianus in Ceratitis capitata larvae reared at different temperatures and relative humidity of 70 ± 10% and a photoperiod of 12:12 h (L:D)

Means (± standard error) followed by the same letter in the row are not significantly different based on the Tukey test (P ≤ 0.05). R o (net reproductive rate), r m (intrinsic growth rate), MGT (mean generation time) and λ (finite rate of increase).

The MGT of T. giffardianus was inversely related to temperature (F = 4.48, df = 2, P = 0.0001) (table 2). The population DT differed significantly at the evaluated temperatures with the lowest DT occurring at 25°C. The finite rate of population increase (λ) was also influenced by temperature (F = 14.48, df = 2, P = 0.0001), and the maximum population growth rate was obtained at 25°C.

Discussion

Effect of temperature on the development of the immature stages of T. giffardianus

Our results showed that temperature influences the development of the immature stages of T. giffardianus. The temperature range in which immatures of T. giffardianus developed (20–30°C) demonstrates that this parasitoid can develop properly in different tropical environments. In general, this temperature range is the most suitable for the pre-imaginal development of most tropical parasitoids such as Doryctobracon areolatus (Szépligeti) (Gonçalves et al., Reference Gonçalves, Andreazza, Lisbôa, Grützmacher, Valgas, Manica-Berto, Nörnberg and Nava2016), D. longicaudata, and Fopius arisanus (Sonan) (Appiah et al., Reference Appiah, Ekesi, Salifu, Afreh-Nuamah, Obeng-Ofori, Khamis and Mohamed2013). However, the immature stages of other parasitoids such as Diachasmimorpha kraussi (Fullaway) (Sime et al., Reference Sime, Daane, Nadel, Funk, Messing, Andrews, Johnson and Pickett2006), Doryctobracon brasiliensis (Szépligeti) (Poncio et al., Reference Poncio, Nunes, Gonçalves, Lisboa, Manica-Berto, Garcia and Nava2016), and Aganaspis pelleranoi (Brèthes) (Gonçalves et al., Reference Gonçalves, Nava, Andreazza, Lisbôa, Nunes, Grützmacher, Valgas, Maia and Pazianotto2014) do not develop at a constant temperature of 30°C.

Although immatures of T. giffardianus were not able to complete their development at 15°C, this finding most likely has no bearing with host survival as some host C. capitata specimens emerged at this temperature. Some studies showed that C. capitata is capable of developing at low temperatures (10–15°C) (Ricalde et al., Reference Ricalde, Nava, Loeck and Donatti2012; Szyniszewska and Tatem, Reference Szyniszewska and Tatem2014). The pre-imaginal non-development of T. giffardianus at a constant temperature of 35°C possibly occurred due to physiological changes in the parasitoids, as they rapidly consumed the host and therefore could not complete the development.

The rate of development of the immature stages of T. giffardianus showed an inverse relationship to temperature. Low temperatures (15°C) led to an increase in the number of days to adult emergence and high temperatures (between 30 and 35°C) led to a decrease in the number days to adult emergence. This probably happened because exposure to extreme temperatures can alter host–parasitoid interactions, thus causing lethal or sublethal damage to parasitoids as a result from changes in the host immune system (Hance et al., Reference Hance, van Baaren, Vernon and Boivin2007; Mirondis and Savopoulou-Soultani, Reference Mirondis and Savopoulou-Soultani2008).

Effect of temperature on biology and demographic parameters of T. giffardianus adults

The different temperatures studied significantly affected the biology and demographic parameters during the adult phase of T. giffardianus. Females of T. giffardianus began ovipositing within the first 24 h after emergence and approximately 50% of oviposition took place by the 5th day of life, except at 15°C when that value was reached only on the 11th day of life. This oviposition behavior is common in parasitoids that emerge with high loads of mature eggs as they tend to maximize their reproduction in the first days of life (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Kaçar, Biondi and Daane2016b).

The largest number of T. giffardianus offspring was recorded at 25°C. Studies on other species of fruit fly parasitoids such as D. longicaudata (Appiah et al., Reference Appiah, Ekesi, Salifu, Afreh-Nuamah, Obeng-Ofori, Khamis and Mohamed2013), Aganaspis daci (Weld) (De Pedro et al., Reference De Pedro, Beitia, Sabater-Muñoz, Asís and Tormos2016), and F. arisanus (Groth et al., Reference Groth, Loeck, Nornberg, Bernardi and Nava2017) reported a higher number of offspring at 25°C. Therefore, our results show that the temperature that favors the highest number of T. giffardianus offspring is similar to what has been found for other species of fruit fly parasitoids.

The sex ratio of the progeny of T. giffardianus was not affected by temperature and was always biased towards females. Thus, our results show that there is no risk of decline in the breeding of T. giffardianus due to the reduction in the number of females in the progeny as a function of temperature. This same trend of a higher proportion of females in the offspring was observed for Tetrastichus giffardii Silvestre reared in C. capitata at 26°C (Mohamed et al., Reference Mohamed, Wharton, Mérey and von and Schulthess2006). Furthermore, Ramadan and Wong (Reference Ramadan and Wong1990) reported that populations of T. giffardianus obtained from fruits in the field also showed a higher proportion of females. The sex ratio of offspring is important for biological control agents, as the higher this proportion the higher the population growth and parasitism rates (Heimpel and Lundgren, Reference Heimpel and Lundgren2000).

The highest daily rates of parasitism by T. giffardianus were recorded at 20 and 25°C. These levels were lower than those observed in braconids (Vargas et al., Reference Vargas, Ramadan, Hussain, Mochizuki, Bautista and Stark2002; Meirelles et al., Reference Meirelles, Redaelli and Orique2013; Poncio et al., Reference Poncio, Nunes, Gonçalves, Lisboa, Manica-Berto, Garcia and Nava2016). However, this low rate of parasitism is compensated for by the gregarious habit of T. giffardianus, since a single parasitized larva/pupa can produce several parasitoids. In our study, some larvae/pupae parasitized by T. giffardianus produced 25–30 individuals. Purcell et al. (Reference Purcell, Nieuwenhoven and Batchelor1996) reported that an average of 11.7 parasitoids emerged from each pupa, at a temperature of 26°C. At temperatures of 15 and 20°C, parasitism was distributed more evenly, whereas at 35°C there was a marked concentration of parasitism in the first days of female life, probably due to acceleration of their metabolism. This daily parasitism distribution pattern was observed in other species of fruit fly parasitoids (Gonçalves et al., Reference Gonçalves, Nava, Andreazza, Lisbôa, Nunes, Grützmacher, Valgas, Maia and Pazianotto2014; Poncio et al., Reference Poncio, Nunes, Gonçalves, Lisboa, Manica-Berto, Garcia and Nava2016; Groth et al., Reference Groth, Loeck, Nornberg, Bernardi and Nava2017).

The 80% variation in cumulative parasitism of T. giffardianus was a function of temperature. The metabolic rate of parasitoids and their reproductive processes can speed up or slow down as a function of temperature (Jervis et al., Reference Jervis, Ellers and Harvey2008; Jaworski and Hilszczański, Reference Jaworski and Hilszczański2013). It is possible that the inverse relationship between temperature and cumulative parasitism occurs due to a trade-off between longevity and reproduction, as observed for A. pelleranoi by Gonçalves et al. (Reference Gonçalves, Nava, Andreazza, Lisbôa, Nunes, Grützmacher, Valgas, Maia and Pazianotto2014).

The results obtained in this study showed that the longevity of T. giffardianus adults decreased with increasing temperatures and males had a longer lifespan. Some studies have suggested that parasitoid survival time is directly related to host size, insects that develop in larger hosts are longer-lived (Sagarra et al., Reference Sagarra, Vincent and Stewart2001; Jervis et al., Reference Jervis, Ellers and Harvey2008). However, in gregarious parasitoids that share host resources, offspring longevity is probably not directly related to host size (Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Poelman and Tanaka2013). It is possible that the high energy demand of reproduction had a negative impact on the longevity of T. giffardianus females, thus reducing their lifespan.

In general, insect longevity is important as a component of individual fitness, which can be considered as an indicator of survival ability. Thus, the negative effect of temperature on the longevity has been widely studied in other fruit fly parasitoids (Appiah et al., Reference Appiah, Ekesi, Salifu, Afreh-Nuamah, Obeng-Ofori, Khamis and Mohamed2013; Gonçalves et al., Reference Gonçalves, Nava, Andreazza, Lisbôa, Nunes, Grützmacher, Valgas, Maia and Pazianotto2014; De Pedro et al., Reference De Pedro, Beitia, Sabater-Muñoz, Asís and Tormos2016).

Fertility life table

The highest estimated net reproductive rate (R o) in this study was 69.96 at 25°C, which indicates that T. giffardianus maintained at this temperature increases by approximately 70 times with each generation. The decrease in R o observed at the other temperatures was probably due to the existence of a trade-off between the reserves used for offspring production and longevity, as reported for other parasitoids by Casas et al. (Reference Casas, Pincebourde, Mandon, Vannier, Poujol and Giron2005) and Snart et al. (Reference Snart, Kapranas, Williams, Barrett and Hardy2018). The net reproductive rate observed in T. giffardianus was much higher than the net reproductive rate of many species of solitary parasitoids, such as D. longicaudata with a R o of 45.56 on C. capitata at 25°C (Meirelles et al., Reference Meirelles, Redaelli and Orique2013). The difference between the R o values of T. giffardianus and D. longicaudata may be explained by the gregarious habit and female-biased sex ratio of the former.

The intrinsic rate of increase (0.21) of T. giffardianus recorded at 25°C was higher than the r m of other species of fruit fly parasitoids such as D. longicaudata (r m = 0.14) (Meirelles et al., Reference Meirelles, Redaelli and Orique2013) and A. pelleranoi (r m = 0.02) (Gonçalves et al., Reference Gonçalves, Andreazza, Lisbôa, Grützmacher, Valgas, Manica-Berto, Nörnberg and Nava2016). The r m index is a major component in the determination of demographic parameters, since it indicates whether the species will be successful in a particular environment or host and the higher the r m, the better the species adapts to the environmental temperature (Pedigo and Zeiss, Reference Pedigo and Zeiss1996). Therefore, among the studied temperatures, T. giffardianus showed an excellent ability to be successful, in an environment with a temperature of 25°C.

The MGT of T. giffardianus showed an inverse relationship with temperature; the higher the temperature the lower the MGT, which was 20.43 days at 25°C. The MGT observed in this study was similar to the value of 21.09 days at 25 ± 2°C documented for this same parasitoid by Purcell et al. (Reference Purcell, Nieuwenhoven and Batchelor1996). This relationship exists because insects are ectothermic organisms in which body temperature varies according to the environmental temperature and the rates of biochemical reactions and biological processes tend to increase exponentially with temperature (Zuo et al., Reference Zuo, Moses, West, Hou and Brown2012).

The shortest DT between generations of T. giffardianus was 3.3 days and was recorded at 25°C. This results in lower than the 3.9 day DT reported by Purcell et al. (Reference Purcell, Nieuwenhoven and Batchelor1996) for T. giffardianus reared on C. capitata at 26°C.

The highest finite growth rate (λ) of T. giffardianus was 1.23 and was recorded at 25°C; at 20 and 30°C there was a reduction in the production of offspring and consequently in the number of females, which directly influences the reduction in λ values. Vargas et al. (Reference Vargas, Ramadan, Hussain, Mochizuki, Bautista and Stark2002) studied the reproductive and population parameters of six species of braconid fruit fly parasitoids and observed the highest finite growth rates (1.08 to 1.13) at 26 ± 2°C.

Based on these results, T. giffardianus adults are more tolerant of extreme temperatures (15 and 35°C) than the immature stages. At the adult life stage, T. giffardianus can parasitize the host over a wide temperature range (15–35°C). Additionally, according to the analysis of the fertility life table data, the best T. giffardianus performance occurs at 25°C for all the parameters studied. Therefore, this is the recommended temperature for T. giffardianus reproduction and mass rearing.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Carter Robert Miller for kindly reviewing an earlier version of the manuscript and Valmir Antonio Costa for the identification of parasitoids. The authors also thank the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) for granting a scholarship to E. C. Fernandes and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the productivity grant in research awarded to D. E. Nava, J. G. Silva, and E. L. Araujo.