Introduction

How a parasite utilizes its host as a resource (whether it is a permanent vs. non-permanent parasite) may influence its host-searching behaviour. For example, parasites, such as blood-sucking dipterans that need only brief contacts with several hosts or most of the parasitoids that lay eggs more than once, have to find new suitable hosts multiple times (Price, Reference Price1997; Meier et al., Reference Meier, Kotrba and Ferrar1999). For these kinds of parasites, there is an increasing chance of making a mistake and choosing a wrong, unsuitable host. On the other hand, if these parasites can learn (which is still under debate), they can enhance their host search and become better in recognising suitable hosts (e.g. Vinson et al., Reference Vinson, Barfield and Henson1977; McCall & Kelly, Reference McCall and Kelly2002). In contrast, ectoparasites that live their life on a single host cannot improve their host search.

Some ectoparasites shed their wings after accepting a host (e.g. Andersen, Reference Andersen1997; Dick & Patterson, Reference Dick, Patterson, Morand, Krasnov and Poulin2006). Although the shedding of wings seems beneficial for an ectoparasite (because it makes moving inside fur easy and may increase fecundity; cf. Kaitala, Reference Kaitala1988), it also incurs costs. For example, Petersen et al. (Reference Petersen, Meier, Kutty and Wiegmann2007) reported that the loss or reduction of wings severely impedes finding a new host and dispersal capacity. Shedding the wings may also mean that switching hosts afterwards is virtually impossible or limited only to short moments when the host is located close to another suitable host. In this type of situation, shedding the wings before evaluating the suitability of the host or after accepting a wrong host is fatal and could be considered as an evolutionary dead end for the individual (cf. Timms & Read, Reference Timms and Read1999). Thereby, it is essential that parasites that live on a single host and shed their wings should succeed in their host choice the very first time.

Host selection by parasitic species commonly has been divided into four steps: host habitat location, host location, host recognition and host acceptance (Vinson, Reference Vinson1976, Reference Vinson, Kerkut and Gilbert1985, Reference Vinson1998; Godfray, Reference Godfray1994; Stireman, Reference Stireman2002). Host habitat location is based mostly on environmental cues that parasites can associate with the presence of a host. Host location, on the other hand, can be based on direct cues from the host. For example, for blood-feeding insects, carbon dioxide from the host's respiration is considered as the most common signal in host location (Gibson & Torr, Reference Gibson and Torr1999). Certain mosquitoes are known to react to CO2 at a distance of 150 m (Clements, Reference Clements1963). Host recognition at closer distance, for example in mosquitoes, is based not only on odours and chemical signals, but also on visual signals and acoustic, temperature and humidity-gradient cues (e.g. Constantini et al., Reference Constantini, Sagnon, della Torre, Diallo, Brady, Gibson and Coluzzi1998). Finally, the host acceptance of blood-sucking insects may depend on the structure of the host's skin, body temperature and blood composition (e.g. Friend & Smith, Reference Friend and Smith1977; Lehane, Reference Lehane1991).

The deer ked (Lipoptena cervi Hippoboscidae) is an ectoparasite of cervids that often mistakenly attacks and accepts other species, especially humans (e.g. Rantanen et al., Reference Rantanen, Reunala, Vuojolahti and Hackman1982; Reunala et al., Reference Reunala, Laine, Vornanen and Härkönen2008). Paradoxically, deer keds shed their wings after accepting the wrong host, which means that they cannot switch the host after acceptance. Thus, the host selection of individual deer keds easily and regularly fails. Deer keds can use humans as a host, but they have never been reported to reproduce on humans. However, after attaching to humans, they irritate the skin and are, therefore, a nuisance. Increasing problems are reported from this parasite in Scandinavia, especially in Finland (Kaitala et al., Reference Kaitala, Kortet, Härkönen, Laaksonen, Ylönen and Baskin2008; Reunala et al., Reference Reunala, Laine, Vornanen and Härkönen2008). In some cases, the deer ked has been reported to cause serious health problems and symptoms in humans, including chronic deer ked dermatitis (Rantanen et al., Reference Rantanen, Reunala, Vuojolahti and Hackman1982) and occupational allergic rhinoconjunctivitis (Laukkanen et al., Reference Laukkanen, Ruoppi and Mäkinen-Kiljunen2005). It may also act as a vector for various diseases (Ivanov, Reference Ivanov1974; Rantanen et al., Reference Rantanen, Reunala, Vuojolahti and Hackman1982; Dehio et al., Reference Dehio, Sauder and Hiestand2004) by vertical or mechanical transmission. For persons that work or visit forests during the season of host-searching adult deer keds, the nuisance and possible health threats may be acute. In the most deer-ked-prevalent areas, this may restrict forest-based recreational activities, like hunting and berry and mushroom picking. Despite the relatively high importance and abundance of the species in Europe, biology of the species has been poorly studied (but see Haarløv, Reference Haarløv1964).

The deer ked differs from other blood-sucking insects in its host-searching behaviour. First, the deer ked's eclosion habitat, and hence host habitat location, is completely regulated by the host's movements. Deer ked females viviparously produce new pupae throughout the year, which passively drop onto the ground, ready for later emergence (Haarløv, Reference Haarløv1964). Second, there are some indications that they use a sit-and-wait tactic: individuals are sedentary and wait for an approaching host to attack it at a close distance (reviewed in Hackman et al., Reference Hackman, Rantanen and Vuojolahti1983). Host recognition and factors affecting the take-off propensity when the host is detected (probability of attacking the host) should be accurate because the deer ked is assumed to attack the host only once and is also notably prone to shed its wings after host acceptance.

In Finland, the main host of deer ked is the moose (Alces alces), which can harbour up to 17,000 deer ked individuals in a single host (Paakkonen, Reference Paakkonen2008). Our own monitoring in 2007 and 2008 revealed the previously unreported finding that, in Finland, the deer ked also occasionally uses wild forest reindeer (Rangifer tarandus fennicus) and semi-domestic reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus) as hosts (Kaunisto et al., Reference Kaunisto, Kortet, Härkönen, Härkönen, Ylönen and Laaksonen2009). The deer ked also parasitizes roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) and, with a low prevalence, the Finnish population of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). An original host in Eurasia is likely to be red deer (Cervus elaphus) (Haarløv, Reference Haarløv1964). There are rare observations of deer ked attacking wolf (Canis lupus) and occasionally dogs (e.g. Itämies, Reference Itämies1979). However, there is virtually no evidence that deer ked attack wild small or medium-sized mammals like mountain hares (Lepus timidus) and red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) (Finnish Food Safety Authority database). Thus, the cues for host recognition must be related to the characteristics of a large mammal host. The most abundant dipteran parasites of large cervids are known to react to chemical stimuli, such as carbon dioxide and temperature, but they may also use visual stimuli when searching for a host (Clements, Reference Clements1963; Hocking, Reference Hocking1971; Allan et al., Reference Allan, Day and Edman1987). In contrast, our preliminary data suggested that deer ked do not use chemical signals but instead prefer movement as a main cue in its host selection. The other main cues, in addition to movement, that the deer ked uses may be visual stimuli, such as shape and colour, that other similar taxa use (Green, Reference Green1986; Gibson & Torr, Reference Gibson and Torr1999; Stireman, Reference Stireman2002). Prior to the current work, there have been conflicting arguments about the different cues, such as colour, that deer keds presumably prefer; but these hypotheses have never been tested properly. For example, the Finnish National Public Health Institute advises people to wear white clothes to avoid deer keds, but the Institute does not report the source of this information.

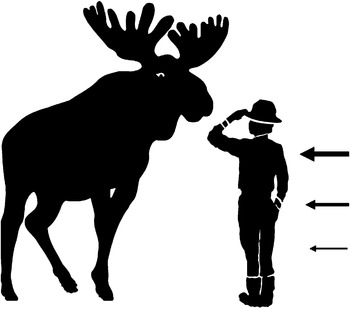

It is important to find a way to avoid deer keds because medical problems may be caused by micro-organisms that can find their way from deer ked to the host. Our main aim was to study whether attacks by deer keds on humans can be avoided by wearing specific colours of clothing. The secondary aim of this work was to explore why the host selection behaviour of an individual deer ked easily fails. We studied these questions by using moving objects (human volunteers) of almost the same height as the natural host, moose. On average, the moose's height is about the same as the upper parts of human (fig. 1; Siivonen & Sulkava, Reference Siivonen and Sulkava1994). The deer ked pupae are associated with the back and neck areas of the moose (see Kaunisto et al., Reference Kaunisto, Kortet, Härkönen, Härkönen, Ylönen and Laaksonen2009). Thus, we predict that attacks by deer ked mostly target the upper part of humans that is also easily visible against a lighter background (i.e. sky) (fig. 1). We also studied the effect of colour but did not have any specific predictions for colour preference. We predicted that deer keds would prefer warmer temperatures on the target, since a natural host is warmer than the environment. Finally, since deer keds can possibly sense temperature gradients and other cues that follow moving animals, we predicted that the back side of the moving object would be preferred. This prediction was also derived from the fact that the back side of a moving object provides a wider aiming angle for attacks (cf. heat tracking in military missiles).

Fig. 1. An indicative illustration of the height at which deer keds were predicted to attack human subjects. Width of the arrow (on the right) indicates our prediction of the body area where deer keds would attack in relation to the height of the natural host, moose (upper, middle and lower parts of the body, respectively).

Methods

The research was conducted in September 2007. The experiments occurred in forests surrounding the Konnevesi Research Station (62°15′N, 26°26′E) and in Saarijärvi, Jokimaa (62°42′N, 25°50′E). These similar study areas were selected because they were presumed to have a high deer ked density. Human study subjects walked randomly in the forest for six, ten or 15 minutes, depending on the trial. Immediately after the walk, the number of deer keds on study subjects was counted. The wind conditions in the experiments were stable, with no detectable wind. The experiments were conducted during the lighted hours of the day, and the weather varied from sunny to half-cloudy during the experiments. The experimental human subjects were dressed in identical experimental garb that varied only with respect to study variables. The head regions of the human subjects were covered with a hood and an insect net hat, and openings in the legs and arms of the clothing were closed in order to prevent deer keds from entering the clothing. During the experimental week, the study persons avoided use of cosmetics and other chemicals in order to minimize the number of potential error sources.

Body parts

To find out which body part the deer keds prefer, the human subjects were dressed in black garb and walked alone in the forest. Transparent flypaper (Ötökkä) (á 4.5×22.5 cm) was used to prevent the deer keds from leaving the humans. Two pieces of flypaper were attached to the upper and lower parts of the torso (both to the front and back sides), and one paper was also attached to both the front and back of each thigh. Persons walked each time for 15 minutes in the experimental area.

Colour

Colour preference experiments were conducted in a pairwise manner: study subjects dressed in the test variables (e.g. black vs. white colour), and walked in the forest side by side (ca. 5 m distance from each other). Test pairs were of same sex and similar size. The persons within the study pairs switched their garb between the trials of the experiments, so both persons within a pair dressed in a specific colour clothing combination in turn. The clothing fabrics were identical in all other aspects than colour. The spectral reflectance of garb was measured with a spectral measurement system with (Hamamatsu PMA-11 fiber spectrometer detector and measurement geometry of 0/45; measurement device developed by InFotonics Center, University of Joensuu). We measured wavelengths ranging from 250–800 nm to reveal possible UV-reflectance, i.e. wave lengths that are visible by many insect species, but not by the human eye (Briscoe & Chittka, Reference Briscoe and Chittka2001).

Black vs. white

The aim of this experiment was to study whether the deer ked would prefer black colour over white colour, or vice versa, in its host selection. This part of the host selection study consisted of two sub-experiments. In both experiments, one person of the pair was dressed in totally white clothing and the other in black clothing. The first part of the experiment was conducted without flypaper using six minute experimental trials. After the first part of the experiment, we found that deer keds sometimes leave the host; and, thus, the second part of the experiment was conducted with transparent flypaper attached to clothing and using longer, ten minute experimental trials. The longer time duration was used to increase the number of deer keds trapped on the flypaper. In this part, two flypapers (á 4.5×22.5 cm) were attached to the upper parts of the garb in such a manner that there was flypaper on the front side and on the back side of the person, ca. 15 cm below the neckline. After the experimental trial, deer keds from the flypaper were counted, as well as any specimens moving freely on the upper and lower parts of the garb.

Black vs. red and black vs. blue

To continue our study on deer ked preferences for certain colours, we also included blue, an unnatural colour, and red, to mimick the colour of some cervid fawns. To test if the deer ked preferred black over red colour, or vice-versa, the people within a pair were dressed in identical garb. On top of the white experimental garb, they wore either a black or a red T-shirt. The flypapers were attached to the T-shirts as described for the earlier black and white experiment. Deer keds were counted only from the T-shirt. This experiment was conducted using a ten-minute experimental time duration. The black vs. blue experiments were conducted in the similar way as black vs. red experiments.

Temperature

To study whether deer keds find their way to a host by using temperature as a cue, we used hand warmer bags (HotHands, 6.4×10.2 cm). Using duct-tape, we attached two heated bags to one shoulder and two identical cold bags to the other shoulder of the experimental garb. A black T-shirt (similar to the ones used in the colour experiments) was worn over the garb and the temperature-bags. On top of the clothing, the heated shoulder temperature was above 20°C while the temperature on the other shoulder was the ambient air temperature (from 5–10°C). Two flypapers were attached to the T-shirt on each shoulder on top of the temperature-bags. This experiment was conducted using a ten-minute experimental time.

Statistical analysis

Since a deer ked that chose one of two study variables could not prefer the other variable, we used related-samples statistics. The normality of the distribution of variables was tested using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. One-tailed statistics were used when the direction for the effects was predicted. To study whether deer ked preferred certain body parts (upper part vs. mid part vs. lower part), we used the Friedman test. To study whether the backside of the body was preferred over the front-side, we used a paired samples t-test. We studied the effect of colour on deer ked host choice using paired statistics. Since the colour variables were normally distributed, we used paired samples t-tests. To study if deer keds preferred the warm shoulder over the cool shoulder, we also used paired statistics; but, since these variables could not meet the requirement of a normal distribution, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used.

Results

In the set of 12 experimental trials testing the preference for different body parts, the total count of deer keds was 134. The backside of the body was preferred over the front-side (Bonferroni-adjusted paired samples t-test (one-way): t=3.010, df=11, P=0.012, n=24; table 1). Moreover, the results revealed that deer keds prefer the upper part of the body and, correspondingly, are averse to the lower part of the body (Friedman test: χ2=19.048, df=2, P<0.001, n=36; table 1). However, it is worth noting that this was just an indicative test since the upper part of the body may be a larger target than the lower part of the body. Spectral measurement curves of the garb are presented in fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Reflectance spectra (250–800 nm) of garb used in the study: solid grey (![]() ), ‘white’ with fluorescence under daylight (D65); dashed grey (

), ‘white’ with fluorescence under daylight (D65); dashed grey (![]() ), ‘white’ without fluorescence; solid black (—), ‘black’; dotted black (· · · ·), ‘red’; dashed black (- - -), ‘blue’.

), ‘white’ without fluorescence; solid black (—), ‘black’; dotted black (· · · ·), ‘red’; dashed black (- - -), ‘blue’.

Table 1. Mean numbers (±SE) of deer keds that landed on the surface of human subjects during experiments (see Methods) testing deer ked preference for body parts, colour and temperature of the object.

In the first set of ten experimental trials for white vs. black clothing, the total count of deer keds was 58. The black clothing was preferred over white clothing in all the study pair trials, the count of deer keds varying from 0 to 5 in white clothing and from 1 to 10 in black clothing (paired samples t-test (two-way): t=4.881, df=9, P=0.001, n=20; table 1). In the second set consisting of eight experiments with flypaper for white vs. black clothing, the total count of deer keds was 100. Again, the black clothing was preferred over white clothing in all the study pair trials, the count of deer keds varying from 0 to 2 in white clothing and from 2 to 22 in black clothing with flypaper (paired samples t-test (two-way): t=4.587, df=7, P=0.003, n=16; table 1).

In the set of 14 experimental trials for black clothing vs. blue clothing, the total count of deer keds was 305. Neither the black clothing nor blue clothing was significantly preferred (paired samples t-test (two-way): t=1.882, df=13, P=0.082, n=28; table 1). In the set of 12 experimental trials for black clothing vs. red clothing, the total count of deer keds was 72. There was no detectable difference in the preference for black and red clothing (paired samples t-test (two-way): t=1.047, df=11, P=0.318, n=24; table 1).

Finally, in the trials investigating whether deer keds preferred a warm shoulder over a cooler shoulder, the total count of deer keds was 94 (table 1). Analysis revealed that more deer keds found their way to the warm part of the body (one-way Wilcoxon signed-rank test: Z=–1.911, P=0.028, n=36; table 1).

Discussion

Our main aim was to study if deer keds can be avoided by wearing certain colours of clothing. Our results suggest that this may be possible since deer keds preferred dark clothing over white clothing. We also hoped to discover why the host choice of an individual deer ked easily fails. The proximate reason for the host choice failure is possibly that the deer ked is innately adjusted to accept any potential host that fulfils its criteria for a suitable natural host. Our main results, together with previous findings, suggest that the deer ked targets large moving objects, prefers warm surfaces, and favours dark and red colours. Paradoxically for deer ked, the only common alternative host of suitable size beside cervids are human beings. Humans are warm, mobile, tall enough and often appropriately coloured, thus fulfilling the criteria of the deer ked host preference. Indeed, for individual deer keds, humans could even be considered an ecological trap (cf. Robertson & Hutto, Reference Robertson and Hutto2006).

An ultimate explanation for the failure of host choice in deer keds could be that the species has a relatively narrow spatial and temporal window when it has to find a suitable host in Fennoscandia. The abundant natural main host in Finland is the moose, which is very mobile and has relatively regular seasonal migration routes during autumn (Heikkinen, Reference Heikkinen2000). Because deer keds seem to be fairly passive in their host searching and can fly only short distances (Hackman et al., Reference Hackman, Rantanen and Vuojolahti1983), they cannot be too selective when they meet a potential host that fulfils their host recognition and acceptance criteria. On the other hand, if a parasite's host choice is temporally or spatially strictly constrained, the probability of its opportunistic acceptance of an unsuitable host increases. On an evolutionary time scale, this inevitably leads to acceptance of more host candidate species. Moreover, when a parasite frequently encounters the wrong, unsuitable host species, it should have adapted to several host species and should not ruin its future possibilities for further host search by shedding its wings (cf. Timms & Read, Reference Timms and Read1999).

Deer keds attacked the upper body parts of humans and preferred the back side of the body over the front side as we predicted. The preference for the upper part of the body may be explained by the fact that the upper body part provides a larger target than the lower part of the body. Alternatively, the legs of a walking person move differently than the upper body and, thus, may provide different landing areas for deer keds. The preference for the back side may be caused by the warmer temperature behind the moving host. This result is further supported by the fact that deer keds preferred the warm area of the experimental subjects.

According to our results, it is clear that more deer keds landed on black clothing than on white clothing, although the deer keds were not totally averse to white. The fur of moose is commonly dark brown or greyish; and, thus, it is not surprising that deer ked favours darkly coloured objects. Dark and unreflecting surfaces, like fur, on the target are known to also attract other blood-sucking insects like blackflies (Simulidae sp.) (Sutcliffe, Reference Sutcliffe1986). This is probably because such surfaces are a cue that can be easily associated with host size, and because the contours of a dark object are easily visible against the sky or other lighter backgrounds.

Spectral measurements of garb show that white garb had a clear reflectance peak in the UV near 300 nm and, thus, is outside the visible range to the human eye (ca. 400–700 nm). In addition, white garb was also highly fluorescent in the daylight (D65), causing the high peak in the reflectance curve at ca. 430 nm (fig. 2). Fluorescent objects ‘convert’ the invisible light into visible light and, thus, cause these objects to look brighter than they would normally be without this phenomenon. It is possible that the deer keds' avoidance of white colour in this study was based at least partly on UV-reflectance or ‘unnatural’ spectral characteristics of the white garb. However, as fluorescence only causes the white garb to look whiter than similar objects without fluorescence, we believe that the avoidance of deer keds was not related to fluorescence, but rather to the white colour itself.

The fact that the red colour was also frequently attacked leads us to suggest that deer ked vision may not be developed enough to distinguish colours other than light-dark contrasts. On the other hand, many of the cervids, such as red deer, and especially fawns, are reddish; and, therefore, deer keds could be adapted to seeing red. Our findings are contradictory to the previous scanty information on deer ked attraction to colours, since Alekseev (Reference Alekseev1985) reported that deer keds attacked humans wearing red overalls 3.3-fold less than those wearing black overalls. Thus, this topic needs future research.

After emergence, deer keds are assumed to climb up on vegetation, allowing them to locate a suitable host visually and fly straight onto it. In our study, deer keds attacked upper body parts of human subjects mainly from the back side. When a potential host passes a deer ked, this induces a take-off flight. After this, the deer ked presumably follows the host from behind, likely using both the temperature (and/or chemical cue) gradients and the silhouette for orientation. By preferring upper and darker parts of the cervid host, a deer ked could ensure that the host animal fits its search image. Supporting this, deer keds have been found to prefer the neck and back area of their natural host (Haarløv, Reference Haarløv1964; Kaunisto et al., Reference Kaunisto, Kortet, Härkönen, Härkönen, Ylönen and Laaksonen2009).

Regarding temperature preference, it is possible that the warmer area on the body was not initially targeted by the flying deer keds. However, after hitting the host the deer keds probably started to move thermotactically towards the warm shoulder and got stuck on the flypaper. Deer keds, like other louse-flies, should be temperature-sensitive since their hosts are warm-blooded animals (Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Roth and Lindquist1950; Bequaert, Reference Bequaert1953; Tetley, Reference Tetley1958). Thus, we conclude that temperature is likely an important factor in host location and/or recognition and potentially in host acceptance. The convection currents of warm air caused by warm-blooded animals under temperate conditions are well within the range of sensitivity of stationary insects but also of insects that are actively flying in search of a host (Hocking, Reference Hocking1971).

Since we studied host choice of deer keds using human targets, our findings can be applied to the every-day life of forest users. Our study of colour preferences could be important because it may help minimize the harm deer keds cause for people. Unfortunately for people using forests for their leisure and work, deer keds may attack warm targets that are large enough. Visual cues are, no doubt, of great importance in host-finding of dipteran parasites at various distances, but these cues may not be specific (Hocking, Reference Hocking1971). Nevertheless, by wearing white clothing that totally covers the body and by closing the entrances under the clothing and under the hair, it is possible to decrease the risk of deer ked bites and, thus, any potential allergic reaction or infection.

To conclude, our study demonstrates that deer keds land on humans in high numbers. This may happen if the parasite is innately adjusted to focus on a certain host and another unsuitable host matches the key characteristics of this natural host. It is apparent that we have only started to understand the complexities of deer ked host choice. Our results have practical importance because they suggest that wearing white clothing can decrease the number of attacking deer keds.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the Konnevesi Research Station and personnel there for their help during the experiment. Also Paul Segersvärd and his professional documentary team are warmly thanked. We thank Ann Hedrick, Christina Lynch, Annukka Kaitala, David Carrasco, Heikki Pöykkö, Sami Kivelä, Geir Rudolfsen, Panu Välimäki and anonymous referees for their helpful and constructive comments on the manuscript. We thank also Anna Honkanen and Anssi Vainikka for their help in the figures of the manuscript, and Jouni Hiltunen and Jussi Kinnunen for spectral measurements of the garb. This study was funded by the University of Oulu (RK), Ella and Georg Ehrnrooth Foundation (LH), Societas Biologica Fennica Vanamo (SK) and Kone Foundation (AK).