Introduction

Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum (Mill.) (Solanaceae)) is among the most extensively cultivated and consumed vegetables in Kenya (MoALF, 2015; HCD, 2017, 2018). It has an annual production of 472,690 t cultivated in 21,718 ha (FAO, 2020). Its value is estimated at KShs 19.9 billion and contributes 38% of the total value of exotic vegetables in Kenya (HCD, 2018). Tomato is highly nutritious and provides good amounts of minerals, antioxidants and vitamins. Besides meeting the nutritional food requirement, tomato production serves as a reliable source of employment and income, thereby contributing to improving livelihoods, and economic growth of the country. Tomato is cultivated in all 47 counties in Kenya under both rain-fed and irrigation systems on open fields or under greenhouse technology (MoALF, 2015). This vegetable contributes significantly to enhancing food security and alleviating poverty. However, successful production is not often achieved due to numerous biotic constraints, among which arthropod pests rank high (Wafula et al., Reference Wafula, Waceke and Macharia2018). The tomato leafminer, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick, 1917) has exacerbated this agricultural problem.

Tuta absoluta, a pest native to South America, was detected in eastern Spain in late 2006 and has since become a devastating tomato pest of worldwide significance (Desneux et al., Reference Desneux, Wajnberg, Wyckhuys, Burgio, Arpaia, Narváez-Vasquez, González-Cabrera, Ruescas, Tabone, Frandon, Pizzol, Poncet, Cabello and Urbaneja2010; Biondi et al., Reference Biondi, Guedes, Wan and Desneux2018). Tuta absoluta is presently spread across Africa and menacing sustainable production of tomato (Mansour et al., Reference Mansour, Brévault, Chailleux, Cherif, Grissa-Lebdi, Haddi, Mohamed, Nofemela, Oke, Sylla, Tonnang, Zappalà, Kenis, Desneux and Biondi2018; CABI, 2020; EPPO, 2020). It was initially detected on Kenyan tomato in Mpeketoni and Witu fields in Lamu County in 2014 and subsequently reported in other counties such as Isiolo, Kirinyaga, Meru, Nairobi, Nakuru, Kakamega, Kajiado and other Rift Valley and Nyanza counties (KALRO, 2014; Mugo, Reference Mugo2014). This invasion poses an important threat to nutrition and food security in Kenya and would result in detrimental socioeconomic impact on livelihoods of small-and medium-holder farmers. Indeed, Pratt et al. (Reference Pratt, Constantine and Murphy2017) estimated an annual monetary loss of KShs 5.98–6.65 billion caused by T. absoluta damages on tomato. Compounded efforts to manage the pest are also associated with increased costs of production and resultant high prices of tomato in the market (Desneux et al., Reference Desneux, Luna, Guillemaud and Urbaneja2011; Pratt et al., Reference Pratt, Constantine and Murphy2017).

Economic losses are derived from direct feeding effects of the larvae. In severe infestations, tomato leaves dry up and attack on other plant parts leads to crop malformation, particularly the developing shoots, and consequent reduction of yield (Urbaneja et al., Reference Urbaneja, Desneux, Gabarra, Arnó, González-Cabrera, Mafra-Neto, Stoltman, Pinto, Parra and Peña2013). Direct attack on fruits induces rotting that reduces both quality and marketability. Infestation levels of T. absoluta are determined using counts of trapped moths, and mines and larvae present on tomato leaves and fruits. Nevertheless, trap catches often provide a more reliable prediction of infestation levels and assists in making timely control decisions before the actual damage on foliage and fruits (Benvenga et al., Reference Benvenga, Fernandes and Gravena2007). Research studies have revealed maximum fruit damage of 100% on open fields and 43.33% in greenhouses (Chermiti et al., Reference Chermiti, Abbes, Aoun, Othmen, Ouhibi, Gamoon and Kacem2009; Mohamed et al., Reference Mohamed, Mohamed and Gamiel2012).

The current control practices for T. absoluta in tomato production systems in Kenya are limited to routine application of synthetic insecticides just like in the native and other invaded regions (Zappalà et al., Reference Zappalà, Biondi, Alma, Al-Jboory, Arnò, Bayram, Chailleux, El-Arnaouty, Gerling, Guenaoui, Shaltiel-Harpaz, Siscaro, Stavrinides, Tavella, Aznaar, Urbaneja and Desneux2013; Mansour et al., Reference Mansour, Brévault, Chailleux, Cherif, Grissa-Lebdi, Haddi, Mohamed, Nofemela, Oke, Sylla, Tonnang, Zappalà, Kenis, Desneux and Biondi2018; Nderitu et al., Reference Nderitu, Muturi, Mark, Esther and Jonsson2018). The larvae, however, escape this approach due to their leaf-mining behaviour (Luna et al., Reference Luna, Sánchez, Pereyra, Nieves, Savino, Luft, Virla and Speranza2012). Consequently, farmers resort to unorthodox control measures such as increasing dosages and frequency of applications, as well as application of pesticide cocktails resulting in reduced efficacy, and potentially more damaging to the environment including ecosystem service providers such as pollinators and other beneficial fauna (Luna et al., Reference Luna, Sánchez, Pereyra, Nieves, Savino, Luft, Virla and Speranza2012; Biondi et al., Reference Biondi, Guedes, Wan and Desneux2018). This misuse and overuse of chemical insecticides could also lead to fast development of pesticide resistant strains as have been observed in many populations worldwide (Han et al., Reference Han, Zhang, Lu, Wang, Ma, Biondi and Desneux2018). Toxic pesticide residues may also persist on harvested fruits, leading to contamination and most notably, food safety concerns for consumers. For these reasons, alternative eco-friendly control strategies are warranted.

An integrated pest management (IPM) strategy based on biological control as the key component is considered as the most viable approach to address T. absoluta. However, crucial information regarding its biology and ecology that is required for the development of an effective, sustainable and environmentally friendly IPM package is scanty. Studies have shown that T. absoluta has diverse species of spontaneous natural enemies (Mansour et al., Reference Mansour, Brévault, Chailleux, Cherif, Grissa-Lebdi, Haddi, Mohamed, Nofemela, Oke, Sylla, Tonnang, Zappalà, Kenis, Desneux and Biondi2018; Ferracini et al., Reference Ferracini, Bueno, Dindo, Ingegno, Luna, Gervassio, Sánchez, Siscaro, van Lenteren, Zappalà and Tavella2019). Therefore, generalist natural enemies in tomato production systems in Kenya could apparently suppress the populations of T. absoluta. However, their field performance is majorly limited by extensive use of pesticides (Nderitu et al., Reference Nderitu, Muturi, Mark, Esther and Jonsson2018). More effort is thus needed to identify and conserve the indigenous natural enemies adapting to T. absoluta to guide on suitable biological control programs and increase their impact in pest management. Studies on geographical distribution and abundance as well as infestation and damage levels on tomato will also be crucial in evaluating its pest status and potential economic risks (Allen and Humble, Reference Allen and Humble2002; Benvenga et al., Reference Benvenga, Fernandes and Gravena2007; Urbaneja et al., Reference Urbaneja, Desneux, Gabarra, Arnó, González-Cabrera, Mafra-Neto, Stoltman, Pinto, Parra and Peña2013). In this regard, the objectives of our study were to (i) determine the abundance of T. absoluta and levels of infestation and damage on tomato in different localities in Kenya, (ii) identify the indigenous natural enemies associated with T. absoluta in Kenya. Our findings would form the basis upon which suitable pest management programs with emphasis on biological control could be developed.

Materials and methods

Field survey

A field survey was conducted in 39 localities in Kenya, from April 2015 to June 2016 to determine the distribution and abundance of T. absoluta, infestation and damage levels on tomato, and associated natural enemies. These localities represent three altitudes commonly found in Kenya: high-, mid- and lowlands. Elevations above 1800 m above sea level (a.s.l) are the highlands; while midlands occupy elevations between 900 and 1800 m a.s.l, and the lowlands are elevations below 900 m a.s.l (Otolo and Wakhungu, Reference Otolo and Wakhungu2013). The survey involved open fields in smallholder farms of <0.5 acres and greenhouses. Selection of a sampling site depended on the availability of tomato at the required phenological stages. These included plants at or nearly flowering stage for sampling of leaves and plants at flowering/fruiting stage for sampling of fruits. Farmers’ practices such as pesticides usage and tomato cultivars planted were not taken into consideration during the study.

Sampling methods

Adult populations of T. absoluta were sampled using delta traps baited with T. absoluta sex pheromone. For each locality, three study sites with tomato plants at or nearly flowering stage were sampled and only one delta trap was used per site. Traps were loaded with removable sticky inserts and sex pheromone lure TUA-Optima PH-937-OPTI (Russell IPM, UK). They were hung at a height corresponding to the upper canopy of the plant (Megido et al., Reference Megido, Haubruge and Verheggen2013), and data were recorded weekly for four consecutive weeks.

Sampling of tomato leaves was carried out in a transversal zigzag sampling pattern at the same sites of pheromone trapping. Thirty plants were randomly selected and assigned labels. Two leaves were picked at random from the middle stratum of each plant (Gomide et al., Reference Gomide, Vilela and Picanço2001). Sixty leaves were thus sampled per site. They were examined and the number of infested leaves was recorded. They were kept in plastic containers (20 × 13 × 8 cm) containing damp paper towels and covered with lids containing fine muslin cloth (16 × 9 cm). The leaves were labelled per site and transported to the laboratory at the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe). They were checked under a stereomicroscope (Leica Microsystems Limited, Switzerland) at 20× magnification to ascertain infestation and counts of mines and larvae per leaf were also recorded. Tomato fruits were sampled from plants at flowering/fruiting stage. Two study sites were selected per locality and 20 fruits were collected randomly per site. They were placed in plastic containers (20 × 13 × 15 cm) and labelled per site. In the laboratory, all fruits were weighed and the number of mines per fruit and total number of infested fruits were recorded. Global positioning system (GPS) readings and altitudes were recorded for all the sampling sites (table 1).

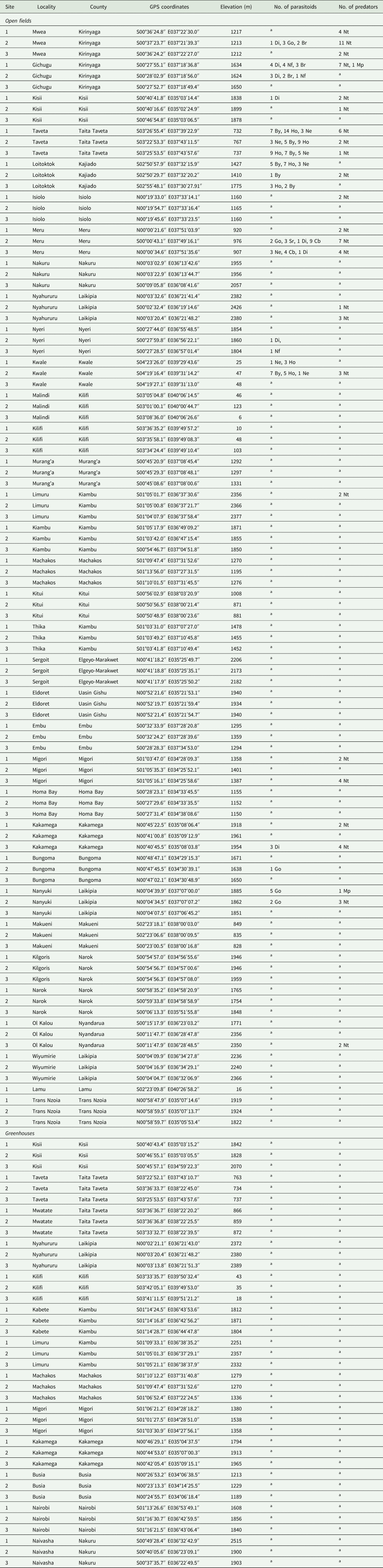

Table 1. Sampling sites for Tuta absoluta and associated indigenous natural enemies from different localities in Kenya between April 2015 and June 2016

Natural enemies associated with T. absoluta: Di, Diglyphus isaea (Walker); Nf, Neochrysocharis formosa (Westwood); Br, Bracon sp.; Ho, Hockeria sp.; By, Brachymeria sp.; Ne, Necremnus sp.; Go, Goniozus sp.; Cb, Chelonus blackburni (Cameron); Sr, Stenomesius rufescens (Retzius); Nt, Nesidiocoris tenuis (Reuter); Mp, Macrolophus pygmaeus (Rambur).

a Parasitoids and predators not found.

Sampling of natural enemies of T. absoluta

Predators of T. absoluta were sampled through active searching on tomato foliage and collected using an adapted aspirator. The aspirator had a plastic collecting vial, and a cap with two rubber tubes running through it. The tube to suck insects into the vial was relatively long, and the tube to draw air was fitted with a fine netting. Parasitoids were targeted from field-collected and infested foliage and fruits. Following the tally, infested leaves were placed in Perspex cages (30 × 30 × 30 cm) fitted with fine netting on opposite sides for ventilation. The cages had a round opening (14 cm diameter) at the front side fixed with a fine netting. The leaves were moistened regularly and developing larvae of T. absoluta were provided with fresh foliage as needed. Infested fruits were placed singly in small containers (6.5 cm height × 11 cm top diameter and 9 cm bottom diameter) containing sterilized sand as a medium for pupation and to absorb sogginess of the ripening tomatoes. They were covered with a fine muslin cloth using rubber bands. All emerging parasitoids and T. absoluta moths were collected and recorded daily.

Sentinel plants

Sentinel plants were used to search for parasitoids in a procedure slightly modified from Abbes et al. (Reference Abbes, Biondi, Zappalà and Chermiti2014). Tomato seeds (var. Simlaw Rio Grande) were sown in plastic germination trays (51 × 32 × 6.5 cm height) in a screen house at the icipe. Seedlings with at least three leaves were transplanted (2 plants per pot) into 2-liter plastic pots (16 cm height × 15 cm top diameter and 8.5 cm bottom diameter) containing soil supplemented with farmyard manure. The plants were maintained under standard agronomic practices. Plants of ~25–30 cm were used for rearing purposes.

A colony of T. absoluta was established from moths emerging from infested foliage and fruits. They were aspirated into Perspex cages (65 × 45 × 45 cm) fitted with a fine netting on opposite sides and had a round opening (20 cm diameter) at the front side to which a fine net sleeve was fixed. The moths were provided with streaks of undiluted honey on the upper wall of cages and moistened cotton wool were placed at the bottom of the cages. The insects were maintained under laboratory conditions of 25 ± 1 °C, 60 ± 10% RH and L16:D8 photoperiod (Abbes et al., Reference Abbes, Biondi, Zappalà and Chermiti2014). Three potted tomato plants were introduced into the cages for oviposition. They were removed after 2 days and placed on the laboratory bench awaiting hatching of eggs. Foliage with developing larvae was cut and placed in separate cages. The larvae were provided with fresh leaves for food until pupal formation. Emerging moths were aspirated daily into the rearing cages. This procedure was repeated severally to maintain the colony of T. absoluta.

Sentinel plants were prepared by infesting healthy potted tomato plants with eggs and three larval instars of T. absoluta (Abbes et al., Reference Abbes, Biondi, Zappalà and Chermiti2014). This procedure was aimed at finding egg and larval parasitoids. Four plants were separately infested with 50 eggs, first, second and third instar larvae using a soft camel hairbrush. Larvae were allowed to establish mines for 1 h and the plants were placed beside open field tomato crops at the icipe. Plants were watered regularly and after 7 days, foliage was cut and placed in Perspex cages (30 × 30 × 30 cm) for the emergence of moths and/or parasitoids. Fourth instars were not included in the study due to their high mobility and tendencies of falling off from the leaves. Pupal parasitoids were targeted by placing 50 green pupae in a glass Petri dish (9.2 cm diameter × 1.7 cm height) and placing them in open field tomato crops for 1 week. They were placed on raised ground free from ants and other crawling insects. One thousand individuals of each developmental stage were exposed. All collected natural enemies were preserved in 70% ethanol for morphological identification and 95% ethanol for molecular identification. They were stored at −20 °C.

Morphological identification of T. absoluta and natural enemies

Adult specimens were identified based on their morphological characteristics by Dr Robert Copeland of biosystematics support unit (BSU), icipe. Molecular identification was done to confirm the species identity of T. absoluta (Kinyanjui et al., Reference Kinyanjui, Khamis, Ombura, Kenya, Ekesi and Mohamed2019), and associated natural enemies.

DNA extraction

For the natural enemies, two adults were randomly selected per species. All samples were surface sterilized using 3% sodium hypochlorite and rinsed with distilled water. They were then put in sterile 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes. Genomic DNA was extracted from individual insect using Isolate II Genomic DNA Kit (Bioline, UK) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing

PCR was carried out to amplify a fragment of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene using Folmer primers (LCO 1490 5′-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′ and HCO 2198 5′-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3′) and Lep primers (LepF1 5′-ATTCAACCAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′ and LepR1 5′- TAAACTTCTGGATGTCCAAAAAATCA-3′) (Folmer et al., Reference Folmer, Black, Hoeh, Lutz and Vrijenhoek1994; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Wood, Janzen, Hallwachs and Herbert2007). The Lep primers were used in cases of poor amplification of the COI gene region by the Folmer primers. PCR was carried out in a 20 μl volume containing 5× MyTaq reaction buffer (Bioline; 5 mM dNTPs, 15 mM MgCl2, stabilizers and enhancers), 0.5 pmol μl−1 of each primer, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.0625 U μl−1 MyTaq DNA polymerase (Bioline) and 15 ng μl−1 of DNA template. Standard cycling conditions of 2 min at 95 °C, then 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 40 s at 54.1 °C (Folmer primers) and 48.1 °C (Lep primers) and 1 min at 72 °C, followed by a final elongation step of 10 min at 72 °C were used. Reactions were set up in a Mastercycler Nexus thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany). PCR products of ~700 bp were resolved through a 1.5% agarose gel and purified using Isolate II PCR and Gel Kit (Bioline, UK) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Purified samples were sent to a commercial sequencing facility (Macrogen Inc., Europe) for bidirectional sequencing using ABI 3700 sequencer. Voucher specimens were stored at the BSU and Molecular Pathology Laboratory, icipe.

Data analysis

Data on weekly trap catches of T. absoluta moths were analyzed using a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with random intercept and slope to assess the linear effect of time on the abundance of T. absoluta. GLMM was carried out using the lmer function of the lme4 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015), and the overall factor effect was assessed using analysis of deviance with Wald χ2 as the test statistic. Data were compared between open fields and greenhouses, and different altitudes and localities. Infestation levels were calculated as percentage of the number of infested leaves or fruits to the total number of leaves or fruits sampled per locality. Data were subjected to a generalized linear model assuming a quasi-binomial distribution error and logit link. Statistical differences in the weekly trap catches and infestation levels were compared using an adjusted Tukey's test.

Data on trap catches per day were averaged per locality and regressed against leaf infestations to test for a positive correlation between the two variables. Abundance of T. absoluta larvae on tomato was assessed by calculating the number of mines and larvae present on infested leaves or fruits per locality. Data were log-transformed (x + 1) to comply with normality assumptions and homogeneity of variance and subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA). Fruit damage was expressed as a percentage of the weight of infested fruits divided by the total weight of all fruits sampled per locality. All percentages were transformed by arcsine square root and analyzed using ANOVA. Comparisons were made between open fields and greenhouses, and different altitudes and localities.

Relative abundance of predators was expressed as a percentage of counts of a single species in a locality over all sampled predators. Parasitism of the solitary parasitoids was calculated as a percentage of emerged parasitoid species divided by the total number of emerged parasitoids and T. absoluta moths per locality. Data were subjected to ANOVA after an arcsine square root transformation and comparisons were made between localities. When ANOVAs were significantly different, Tukey's HSD test was used to separate the means. Data on percentage parasitism obtained from sentinel tomato plants were first transformed by arcsine square root and subjected to a two-sample t-test. All analyses were carried out in R v3.2.3 software (R Development Core Team, 2015).

For molecular identification, COI sequences generated from both Folmer and Lep primers were assembled and edited using Chromas v2.1.1 (Technelysium Pty Ltd, Queensland, Australia). Sequence identities were determined using basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) (Altschul et al., Reference Altschul, Gish, Miller, Myers and Lipman1990). The sequences were deposited in GenBank and assigned accession numbers MT916726 to MT916739.

Results

Distribution and abundance of T. absoluta

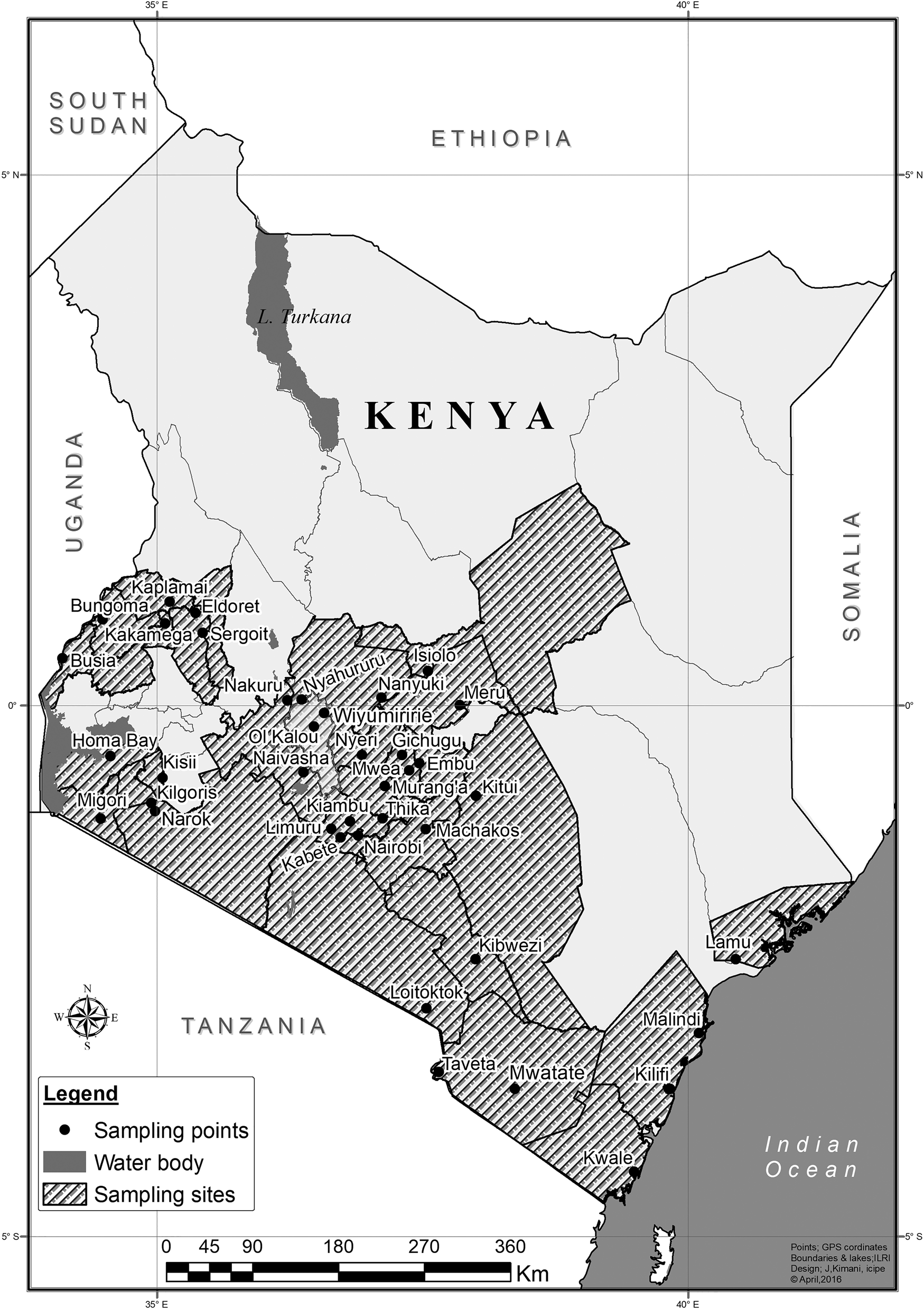

Tuta absoluta was present in all the sampled 39 localities representing 29 counties in Kenya (fig. 1). Overall abundance of trapped moths was significantly higher in open fields (1736.52 ± 76.91) than in greenhouses (1265.67 ± 108.97) (table 2; χ2 = 8.99, df = 1, P < 0.001). However, abundance of T. absoluta in high (1588.48 ± 90.52), mid (1670.56 ± 131.49) and low altitudes (1513.00 ± 109.22) did not differ significantly (table 2; χ2 = 0.62, df = 2, P = 0.730). Analysis of linear effect of time revealed a highly significant difference between the weekly trap data (χ2 = 1119.02, df = 3; P < 0.001). In week 1, 758.62 ± 32.70 moths were recorded, whereas 218.40 ± 10.45 moths were recorded in week 4 (fig. 2).

Table 2. Overall abundance (mean ± SE) of trapped Tuta absoluta moths across different altitudes and cultivation areas

Within columns, means followed by the same lowercase are not significantly different (P < 0.05, adjusted Tukey test).

Figure 1. Map of Kenya showing the sampling sites for Tuta absoluta.

Figure 2. Weekly captures (mean ± SE) of Tuta absoluta moths using delta traps baited with sex pheromone. Bars with same lowercase letters are not significantly different (P < 0.05, adjusted Tukey test).

Average counts of moths per trap per day ranged from 7.75 ± 4.37 to 115.38 ± 15.90 and were significantly higher in open fields (62.02 ± 2.75) than greenhouses (45.20 ± 3.89) (table 3; χ2 = 8.96, df = 1, P < 0.001). Within the greenhouses, significant differences were also observed in the abundance of T. absoluta recorded in different localities (table 3; F 12,143 = 2.76, P = 0.002). Trapped moths were significantly higher in Kisii (77.08 ± 19.39) and Kakamega (67.73 ± 2.03) than in Nairobi (36.35 ± 16.82), Kabete (19.35 ± 9.98) and Busia (15.67 ± 3.25). Similarly, open fields in Loitoktok (115.38 ± 15.90), Mwea (98.00 ± 14.27) and Meru (95.35 ± 5.19) recorded significantly higher abundance than in Makueni (26.81 ± 6.83), Kilgoris (22.98 ± 5.54), Narok (18.25 ± 4.14) and Thika (7.75 ± 4.37) (table 3; F 32,363 = 4.12, P < 0.001).

Table 3. Distribution, abundance and leaf infestation (mean ± SE) for Tuta absoluta in greenhouse- and open field-cultivated tomato in Kenya

Means followed by the same lowercase letters in a column within greenhouses and open fields are not significantly different. Means followed by the same uppercase letters for the mean totals in a column are not significantly different (P < 0.05, Tukey's HSD test).

1 Pooled analysis for greenhouse and open field data.

2 No significant differences across localities.

Infestation and damage levels of T. absoluta

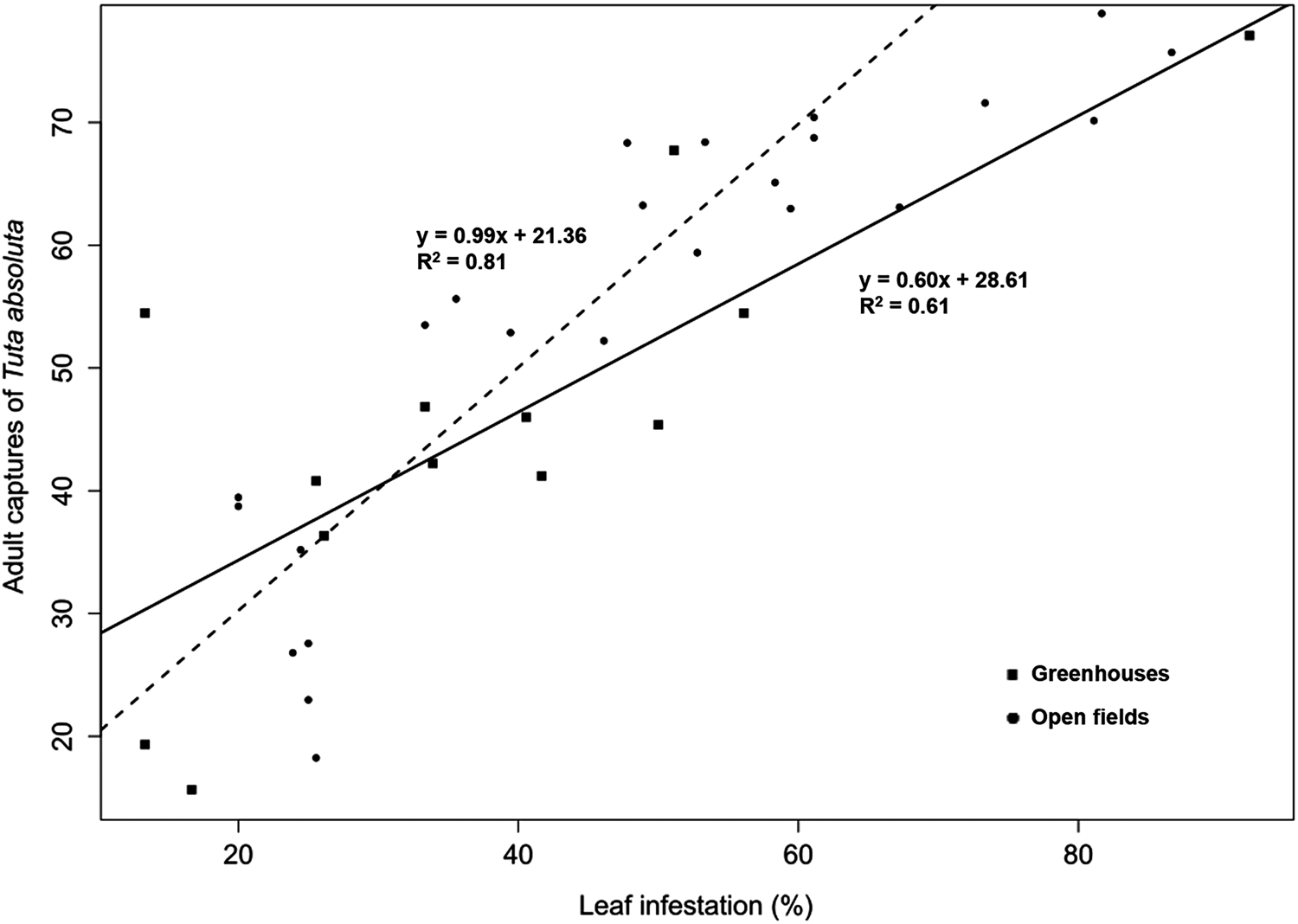

Leaf infestations were significantly higher in open fields (52.07 ± 2.47%) than in greenhouses (37.99 ± 3.69%) (table 3; F = 9.45, df = 1, P = 0.003). Mean infestations in open fields ranged from 3.89 ± 2.42 to 86.67 ± 2.55% and were significantly lower in Thika (3.89 ± 2.42%) than Taveta (86.67 ± 0.00%) and Loitoktok (86.67 ± 2.55%) (table 3; F 32, 66 = 8.20, P < 0.001). In the greenhouses, leaf infestations ranged from 13.33 ± 4.41% to 92.22 ± 3.38% and were relatively high in Kisii (table 3; F 12, 26 = 9.51, P < 0.001). No significant differences were found in leaf infestations across altitudes (F = 0.31, df = 2, P = 0.730). Regression analysis yielded a significant linear and positive relationship between trapped T. absoluta moths and leaf infestations in both open fields (F 1,31 = 132.02, P < 0.001) and greenhouses (F 1,11 = 17.01, P = 0.002) (fig. 3).

Figure 3. Linear regression of daily trap captures (mean ± SE) of Tuta absoluta moths vs. leaf infestation (mean ± SE) of tomato cultivated in different localities in Kenya. The black line and dotted lines represent greenhouses and open fields, respectively.

There were no significant differences in the abundance of mines per leaf between greenhouses and open fields (F 1,136 = 0.73, P = 0.390), hence data were pooled together. Mean counts of mines per leaf, however, differed significantly between localities (F 37,100 = 2.19, P = 0.001). An average count of 3 to 4 mines per leaf recorded in nine localities was significantly higher than 1.10 ± 0.56 mines recorded in Thika (table 3). The maximum and minimum average counts of mines per leaf were 3.71 ± 0.28 and 1.10 ± 0.56, respectively (table 3). No significant differences were observed in the mean count of mines per leaf across altitudes (F 2,135 = 0.24, P = 0.780). The abundance of larvae per leaf ranged from 0.42 ± 0.42 to 2.16 ± 0.45 and did not differ significantly between open fields and greenhouses (F 1,136 = 1.43, P = 0.230), and across altitudes (F 2,135 = 0.63, P = 0.540) and localities (F 37,100 = 1.34, P = 0.130) (table 3).

The levels of T. absoluta infestations on tomato fruits were 17.14 ± 5.81% in the greenhouses and 19.61 ± 2.34% on open fields, hence no significant differences were observed (table 4; F = 0.19, df = 1, P = 0.660). Similarly, there were no significant differences in fruits’ infestation across altitudes (F = 0.92, df = 2, P = 0.410). Data were thus pooled together. Among localities, however, infested fruits in Kisii (60.00 ± 15.00%) were significantly higher than in Naivasha (2.50 ± 2.50), Meru (0.00 ± 0.00) and Migori (0.00 ± 0.00) (F = 1.64, df = 25, P = 0.050). The maximum average count of T. absoluta mines per fruit was 7.50 ± 0.50. There were no significant differences in the number of mines per fruit between open fields and greenhouses (table 4; F 1,50 = 2.07, P = 0.160), and across localities (F 25, 26 = 1.22, P = 0.300) and altitudes (F 2,49 = 3.86, P = 0.280).

Table 4. Fruit infestation and damage (mean ± SE) for Tuta absoluta in greenhouse- and open field-cultivated tomato in Kenya

Pooled analysis for greenhouse and open field data. Means followed by the same uppercase or lowercase letters in a column are not significantly different (P < 0.05, Tukey's HSD test).

1 No significant differences across localities.

The damage levels on fruits in greenhouses (17.64 ± 5.78%) and open fields (19.02 ± 2.49%) did not differ significantly (table 4; F1 ,50 = 0.42, P = 0.520). Similarly, no significant differences were observed on the levels of fruits’ damage across altitudes (F 2,49 = 3.80, P = 0.260). For the localities, the damage of T. absoluta on tomato fruits was significantly higher in Kisii (59.61 ± 12.13%) than in Naivasha (0.97 ± 0.97), Meru (0.00 ± 0.00) and Migori (0.00 ± 0.00) (table 4; F 25, 26 = 1.44, P = 0.045).

Natural enemies of T. absoluta

A total of 81 mirid bugs (Hemiptera: Miridae) comprising two species were recorded. Nesidiocoris tenuis (Reuter) was the most abundant predator (97.50%), and was recorded in 14 localities, while Macrolophus pygmaeus (Rambur) (2.45%) was sampled in two localities (fig. 4). Nesidiocoris tenuis were assigned GenBank accession numbers MT916736 and MT916737, while no molecular analysis was conducted on M. pygmaeus due to limited samples. A total of 160 hymenopterans representing nine species emerged from infested leaves collected from 11 localities, and some could only be identified to the genus level (table 5). These larval parasitoids included four families, Chalcididae (Brachymeria and Hockeria species), Bethylidae (Goniozus sp.), Braconidae (Chelonus blackburni (Cameron) and Bracon sp.) and Eulophidae (Diglyphus isaea (Walker)), Neochrysocharis formosa (Westwood), Stenomesius rufescens (Retzius) and Necremnus species. The overall parasitism was 7.26 ± 0.65%. Hockeria species was the most abundant (31.25%) and accounted for the highest parasitism of 12.88 ± 1.47% (table 5). Parasitism rates exhibited by individual species did not differ significantly when compared between localities (F = 1.86, df = 10, P = 0.120). Diglyphus isaea was the most widely distributed parasitoid and was recorded in six localities (table 5). No natural enemies were recorded from infested leaves and fruits sampled in the greenhouses.

Figure 4. Relative abundance for predators of Tuta absoluta collected from different localities in Kenya.

Table 5. Species composition, abundance and parasitism of parasitoids associated with Tuta absoluta larvae in Kenya

Parasitoids were sampled from tomato crops. Percentage values accompanying species names in the column of the corresponding taxon represent the percentage similarity between study sequences and those from the NCBI GenBank database. Abundance is represented as counts of parasitoids (percentage composition).

a Samples did not match sequences present in the GenBank database.

b Molecular identification not done due to limited number of samples.

Nineteen parasitoids representing two species, Hockeria and Necremnus were recovered from sentinel plants infested with second and third larval instars of T. absoluta. The overall parasitism rate was 1.13 ± 0.25% (table 6). Parasitism rates varied significantly between species (t = 3.50, df = 78, P < 0.001), and Hockeria species was the most abundant (84.21%), with an average parasitism of 1.94 ± 0.42% (table 6). Parasitism of individual species did not differ significantly between the second and third instars of T. absoluta larvae (table 6). In addition, no parasitoids were recorded from the eggs, first instar larvae and pupae of T. absoluta.

Table 6. Percentage parasitism (mean ± SE) of parasitoids obtained from sentinel tomato (var. Simlaw Rio Grande) between November 2015 and March 2016.

Means followed by the same lowercase letters in a row and same uppercase letters in a column are not significantly different (P < 0.05, two sample t-test).

Discussion

Our trap data indicated a widespread distribution of T. absoluta across Kenya. This could be mainly attributed to a year-round cropping and countrywide production of tomato, as well as favourable national agro-ecological conditions (MoALF, 2015; Tonnang et al., Reference Tonnang, Mohamed, Khamis and Ekesi2015), hence ensuring an uninterrupted supply of host. Regional trade of tomato fruits and seedlings from probably infested to non-infested areas may also have played a role in dispersing the pest nationwide (Tonnang et al., Reference Tonnang, Mohamed, Khamis and Ekesi2015). Tuta absoluta was found in low altitudes of 6 m a.s.l and high altitudes of 2515 m a.s.l. Analyses of GLMM also showed that altitude did not significantly influence the abundance of the pest. These results agreed with Pratt et al. (Reference Pratt, Constantine and Murphy2017) who reported that the geographical distribution of T. absoluta was unlikely to be determined by altitude. Tuta absoluta has been associated with altitudes <1000 m a.s.l. (Desneux et al., Reference Desneux, Wajnberg, Wyckhuys, Burgio, Arpaia, Narváez-Vasquez, González-Cabrera, Ruescas, Tabone, Frandon, Pizzol, Poncet, Cabello and Urbaneja2010; Tonnang et al., Reference Tonnang, Mohamed, Khamis and Ekesi2015). Our results, however, showed that the pest can also thrive in altitudes above 1000 m a.s.l. Previous results also confirmed the presence of T. absoluta in altitudes of 1235 m a.s.l in Tanzania and 1140 m a.s.l in Uganda (G. Kinyanjui et al., unpublished data). These findings fitted a report in Colombia, where the pest was found in greenhouse and open field tomato crops at 2600 and 1900 m a.s.l, respectively (Desneux et al., Reference Desneux, Wajnberg, Wyckhuys, Burgio, Arpaia, Narváez-Vasquez, González-Cabrera, Ruescas, Tabone, Frandon, Pizzol, Poncet, Cabello and Urbaneja2010).

The Kenyan highlands are generally characterized by cold climate. Therefore, the presence of T. absoluta in these areas in open fields rather than confined in greenhouses confirmed the species’ ability to survive colder conditions and cause damage at high altitudes (Tonnang et al., Reference Tonnang, Mohamed, Khamis and Ekesi2015; Biondi et al., Reference Biondi, Guedes, Wan and Desneux2018). Typically, altitude does not solely determine the distribution and abundance of a pest species but factors such as climatic and environmental conditions, and availability of suitable host plants play an important role (Geurts et al., Reference Geurts, Mwatawala and De Meyer2012). Therefore, besides high adaptability, the trap data of T. absoluta in Loitoktok and Mwea, which are among the major producers of tomato in Kenya (HCD, 2017), confirmed that availability of tomato seemed to have a decisive influence in the distribution and abundance of the pest.

Trap data corresponded to leaf infestations in open fields and greenhouses. This was expected since high adult populations reflect more oviposition and increased number of mines and larvae on foliage. Moreover, the phenological stage of nearly or at flowering, at which sampling was done, is usually characterized by high populations of T. absoluta eggs and first instar larvae, thus leading to increased levels of leaf infestations and high number of mines per leaf (Chermiti et al., Reference Chermiti, Abbes, Aoun, Othmen, Ouhibi, Gamoon and Kacem2009). A positive correlation between trap data of T. absoluta and leaf infestations on tomato has also been reported (Benvenga et al., Reference Benvenga, Fernandes and Gravena2007; Abbes and Chermiti, Reference Abbes and Chermiti2011; Assaf et al., Reference Assaf, Hassan, Ismael and Saeed2013). These two parameters are good indicators of damage levels (Benvenga et al., Reference Benvenga, Fernandes and Gravena2007). Thus, based on our data of trapped moths and leaf infestations, T. absoluta could be among others, a contributing factor to economic damage of tomato in Kenya. The significant reduction of trap catches in week 4 could either be due to reduced pest populations because of pheromone trapping or reduced efficacy of pheromone lures (TUA-Optima) at the end of their shelf life (Megido et al., Reference Megido, Haubruge and Verheggen2013).

Significant differences were observed in leaf infestations across localities, which could be related to the differential abundance of the pest as reported herein. In addition, different tomato cultivars were sampled, where some are relatively susceptible to T. absoluta attack (Gharekani and Salek-Ebrahimi, Reference Gharekani and Salek-Ebrahimi2014). Generally, leaf infestations on greenhouse-protected tomato were lower than the vulnerable plants in the open fields. However, our results showed that once the pest enters the greenhouses, infestations could be severe reaching up to 92%. The observed differences in the abundance of mines and larvae on foliage could perhaps be due to migration of larvae to fresh mines or to pupation sites.

The levels of fruits’ infestation and damage were generally low. The damage on open field tomato (19%) was lower than Sudan (80–100%) (Mohamed et al., Reference Mohamed, Mohamed and Gamiel2012). However, the overall fruit damage in greenhouses (18%) was close to the levels reported in protected cultivations in Tunisia (20%) (Chermiti et al., Reference Chermiti, Abbes, Aoun, Othmen, Ouhibi, Gamoon and Kacem2009). Our results could be largely influenced by the phenological stage of the crop, since the sampled flowering/fruiting stage is usually characterized by early or no fruits infestation (Chermiti et al., Reference Chermiti, Abbes, Aoun, Othmen, Ouhibi, Gamoon and Kacem2009). At this crop stage, preferent fresh foliage is plenty for T. absoluta larvae (Galdino et al., Reference Galdino, Picanço, Ferreira, Silva, de Souza and Silva2015), and as such, minimal or null infestations on fruits are expected. The relatively high values recorded in Kisii (59.6%) could be linked to high abundance of the pest, which corresponds to increased infestation densities, complete destruction of foliage and a consequent shift of feeding sites (Chermiti et al., Reference Chermiti, Abbes, Aoun, Othmen, Ouhibi, Gamoon and Kacem2009; Galdino et al., Reference Galdino, Picanço, Ferreira, Silva, de Souza and Silva2015). These results also confirmed the study of Cely et al. (Reference Cely, Cantor and Rodriguez2010) who reported that fruit damage was a function of density of T. absoluta populations. Maximum fruit damage is also likely to occur at senescence stage, and therefore, further studies are warranted to assess the population dynamics and damage caused by T. absoluta at different phenological stages of tomato crop.

Our data showed that indigenous natural enemies in Kenya are adapting to T. absoluta and could provide a solid foundation for sustainable management of the pest. However, the overall abundance was low. This could be explained by the short period of adaption, considering that sampling of natural enemies was conducted between April 2015 and June 2016, and the first report of T. absoluta in Kenya was 2014. Nevertheless, most natural enemies of T. absoluta are generalists (Ferracini et al., Reference Ferracini, Bueno, Dindo, Ingegno, Luna, Gervassio, Sánchez, Siscaro, van Lenteren, Zappalà and Tavella2019). Thus, it is highly probable that species diversity will increase in future as more natural enemies adapt to the pest. Low abundance of natural enemies could also be due to adverse farming practices adopted by growers such as calendar-scheduled applications of pesticides to control T. absoluta and other tomato pests. Indeed, Nderitu et al. (Reference Nderitu, Muturi, Mark, Esther and Jonsson2018) observed that farmers in Kirinyaga County sprayed up to 16 times per growing season, which had adverse effects on natural enemies. Awareness campaigns, therefore, on the need to conserve native natural enemies should be considered, because in addition to reducing environmental damage and human health risks, fortuitous biological control could provide some huge economic benefits to growers.

Nesidiocoris tenuis and Macrolophus pygmaeus were found preying on T. absoluta. These polyphagous predators’ prey on a wide range of tomato pests and attack all the pre-imaginal stages of T. absoluta (Urbaneja et al., Reference Urbaneja, Montón and Mollá2009). Mollá et al. (Reference Mollá, Montón, Vanaclocha, Beitia and Urbaneja2009) demonstrated that a good establishment of these two predators on tomato crop significantly reduced T. absoluta infestations on both leaves and fruits. Some authors, however, reported their failure to achieve acceptable levels and thus advocated for integration with other pest control alternatives (Mollá et al., Reference Mollá, Gonzalez-Cabrera and Urbaneja2011; Abbes and Chermiti, Reference Abbes and Chermiti2012; Nannini et al., Reference Nannini, Atzori, Murgia, Pisci and Sanna2012).

A record of nine species of larval parasitoids of T. absoluta indicated a higher diversity in Kenya than in Tunisia and Algeria (Boualem et al., Reference Boualem, Allaoui, Hamadi and Medjahed2012; Abbes et al., Reference Abbes, Biondi, Zappalà and Chermiti2014). However, parasitism rate of 12.9% is relatively lower than maximum parasitism rates reported in Tunisia (25.5%) and Turkey (37.0%) (Doğanlar and Yiğit, Reference Doğanlar and Yiğit2011; Abbes et al., Reference Abbes, Biondi, Zappalà and Chermiti2014). Hockeria species was the most promising in terms of abundance and parasitism rate. This finding differs from studies conducted in Tunisia, Spain and Italy, which reported Necremnus species as the most frequently encountered parasitoids (Ferracini et al., Reference Ferracini, Ingegno, Navone, Ferrari, Mosti, Tavella and Alma2012; Abbes et al., Reference Abbes, Biondi, Zappalà and Chermiti2014; Gabarra et al., Reference Gabarra, Arnó, Lara, Verdú, Ribes, Beitia, Urbaneja, Téllez, Mollá and Riudavets2014).

In the study, different parasitoid species were found in different localities. This finding suggested that environmental and climatic conditions may have had an influence on diversity. Whilst Hockeria and Brachymeria species were the most abundant (52.5%), our results showed that they may be better adapted to mid and low altitudes. The widely distributed Diglyphus isaea also exhibited an adaptability to high and mid altitudes. Our results showed that parasitoids were mostly obtained from localities that registered relatively high infestations and trap catches of T. absoluta. We hypothesize therefore that the occurrence and abundance of the pest may also have contributed to the overall abundance and diversity of the sampled parasitoids.

Species identifications of natural enemies concurred with reports in the native and invaded regions (Desneux et al., Reference Desneux, Wajnberg, Wyckhuys, Burgio, Arpaia, Narváez-Vasquez, González-Cabrera, Ruescas, Tabone, Frandon, Pizzol, Poncet, Cabello and Urbaneja2010; Zappalà et al., Reference Zappalà, Biondi, Alma, Al-Jboory, Arnò, Bayram, Chailleux, El-Arnaouty, Gerling, Guenaoui, Shaltiel-Harpaz, Siscaro, Stavrinides, Tavella, Aznaar, Urbaneja and Desneux2013; Ferracini et al., Reference Ferracini, Bueno, Dindo, Ingegno, Luna, Gervassio, Sánchez, Siscaro, van Lenteren, Zappalà and Tavella2019). Hockeria unicolor (Walker) and Brachymeria secundaria (Ruschka) have been reported in Spain and Turkey (Doğanlar and Yiğit, Reference Doğanlar and Yiğit2011; Gabarra et al., Reference Gabarra, Arnó, Lara, Verdú, Ribes, Beitia, Urbaneja, Téllez, Mollá and Riudavets2014). Although these authors reported low frequency and parasitism, our study showed that Hockeria and Brachymeria species were the most important parasitoids of T. absoluta in Kenya. Diglyphus isaea (Walker) and Neochrysocharis formosa (Westwood) have been reported as parasitoids of Liriomyza species in vegetable systems in Kenya (Foba et al., Reference Foba, Salifu, Lagat, Gitonga, Akutse and Fiaboe2016). Our study, therefore, showed that these species have expanded their host range towards T. absoluta and corroborated reports in Algeria, France, Italy and Spain (Zappalà et al., Reference Zappalà, Biondi, Alma, Al-Jboory, Arnò, Bayram, Chailleux, El-Arnaouty, Gerling, Guenaoui, Shaltiel-Harpaz, Siscaro, Stavrinides, Tavella, Aznaar, Urbaneja and Desneux2013; Dehliz and Guénaoui, Reference Dehliz and Guénaoui2015). Although D. isaea reported a relatively wide distribution, parasitism on T. absoluta was lower than Liriomyza species (Foba et al., Reference Foba, Salifu, Lagat, Gitonga, Akutse and Fiaboe2016).

To our knowledge, Stenomesius rufescens (Retzius) is recorded for the first time as a larval parasitoid of T. absoluta. This finding agreed with studies from Spain, Algeria and France that have reported Stenomesius species as parasitoids of T. absoluta larvae (Zappalà et al., Reference Zappalà, Biondi, Alma, Al-Jboory, Arnò, Bayram, Chailleux, El-Arnaouty, Gerling, Guenaoui, Shaltiel-Harpaz, Siscaro, Stavrinides, Tavella, Aznaar, Urbaneja and Desneux2013; Gabarra et al., Reference Gabarra, Arnó, Lara, Verdú, Ribes, Beitia, Urbaneja, Téllez, Mollá and Riudavets2014; Dehliz and Guénaoui, Reference Dehliz and Guénaoui2015). Our finding on Necremnus species fitted studies from various authors that have reported eight Necremnus species associated with T. absoluta larvae (Ferracini et al., Reference Ferracini, Bueno, Dindo, Ingegno, Luna, Gervassio, Sánchez, Siscaro, van Lenteren, Zappalà and Tavella2019). Identification of Bracon and Chelonus species concurred with reports from native and several invaded regions (Ferracini et al., Reference Ferracini, Bueno, Dindo, Ingegno, Luna, Gervassio, Sánchez, Siscaro, van Lenteren, Zappalà and Tavella2019). Molecular identification further identified Chelonus species as Chelonus blackburni (Cameron), and thus adds to the catalogue of T. absoluta parasitoids as a new record. The recovery of a Goniozus species could be supported by the studies that have reported Goniozus nigrifemur Ashmead as a larval parasitoid of T. absoluta (Ferracini et al., Reference Ferracini, Bueno, Dindo, Ingegno, Luna, Gervassio, Sánchez, Siscaro, van Lenteren, Zappalà and Tavella2019). Despite the diverse species of parasitoid reported to form new association with T. absoluta in this study, the parasitism rate was quite low. This call for introduction of efficient co-evolved natural enemies from the pest aboriginal home for classical biological control of the pest in Kenya and Africa at large, an approach which is being explored (Aigbedion-Atalor, et al., Reference Aigbedion-Atalor, Mohamed, Hill, Zalucki, Azrag, Srinivasan and Ekesi2020).

Conclusion

Our study has shown that T. absoluta is widely distributed in Kenya and has attained significant levels of abundance and infestation on tomato in most production areas. The presence of T. absoluta at high-, mid- and low-elevation regions indicated that its nationwide distribution is not limited by altitude. The observed leaf infestation implied an important reduction in crop productivity, whereas damage on fruits reflected substantial financial losses and low returns. Our findings also indicated that several indigenous natural enemies have adapted to T. absoluta, thus the need to conserve them as a startup of biological control and exploitation in future IPM programs. More research, however, is required to evaluate their effectiveness as potential biocontrol agents of T. absoluta. Furthermore, the study revealed overall low abundance and parasitism rates which pave the way and call for introduction of efficient natural enemies as a potentially sustainable control alternative.

Acknowledgements

This work received financial support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) commissioned and administered through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) Fund for International Agricultural Research (FIA), grant number: 81157481. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the financial support for this research by the following organizations and agencies: African Union Funded Tuta-IPM Project (contract number: AURG II-2-123-2018); the Biovision foundation Tuta IPM project (project ID: BV DPP-012/2019-2021); Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, the Section for research, innovation, and higher education grant number RAF-3058 KEN-18/0005; UK's Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO); the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida); the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC); the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia; and the Government of the Republic of Kenya. G.K was supported by the grant number: 81157481. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the donors. Further appreciation goes to the support from local agricultural extension officers and all tomato farmers who allowed access to their farms. We are grateful to Dr R. Copeland for identification of natural enemies and Dr Daisy Salifu for her assistance with statistical analysis of this work. Francis Obala and Linda Mosomtai are acknowledged for their technical input. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their input that helped improve the manuscript.