Introduction

The genus, Trichosanthes L. belongs to Cucurbitaceae and consists of ca. 100 species. The genus is of Asiatic origin and is grown at an altitude from 1200 to 2300 m (Saboo et al., Reference Saboo, Thorat, Tapadiya and Khadabadi2012). Trichosanthes anguina L., commonly known as snake gourd or serpent gourd, is a widely cultivated vegetable in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, China, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia, Philippines and Australia (Peter and David, Reference Peter and David1991; Devi, Reference Devi2017; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Singh and Navneet2017). The fruit is a rich source of vitamins A, B and C. In traditional medicine, the plant is used as an appetizer, laxative, aphrodisiac, blood purifier (Sivarajan and Balachandran, Reference Sivarajan and Balachandran1994) and for treatment of wounds including boils, sores, skin eruptions such as eczema and dermatitis (Pullaiah, Reference Pullaiah2006). The whole plant has an immense medicinal value such as antidiabetic (Arawwawala et al., Reference Arawwawala, Thabrew and Arambewela2009), gastro-protective (Arawwawala et al., Reference Arawwawala, Thabrew and Arambewela2010a), anti-inflammatory (Arawwawala et al., Reference Arawwawala, Thabrew, Arambewela and Handunnetti2010b) and antimicrobial activity (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Sayeed, Islam, Yeasmin, Khan and Muhamad2011; Patil and Kannapan, Reference Patil and Kannapan2014). The whole plant is also a good source of antioxidants (Arawwawala et al., Reference Arawwawala, Thabrew and Arambewela2011).

The caterpillar, Diaphania indica (Saunders) (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) is one of the major insect pests of T. anguina in India and Sri Lanka (Roopa et al., Reference Roopa, Rajashekara, Ramakrishna and Venkatesha2014). The insect is also a serious pest of cucumber, melon, gherkin, bottle gourd, bitter gourd, snake gourd, luffa, little cucumber and cotton (Tripathi and Pandy, Reference Tripathi and Pandy1973; Pandey, Reference Pandey1977; Clavijo et al., Reference Clavijo, Munroe and Arias1995; Hosseinzade et al., Reference Hosseinzade, Izadi, Namvar and Samih2014). The first to third-instar larvae feed on the lower surface of leaves, while fourth and fifth-instar larvae gregariously consume leaves. After defoliating, the caterpillar also attacks flowers and fruits of the plant and finally, results in loss of crop yield (Patel and Kulkarny, Reference Patel and Kulkarny1956). The yield loss of different cucurbit fruits varies from 14 to 30%, which depends on the infestation by this caterpillar on crop species (Jhala et al., Reference Jhala, Patel, Dabhi and Patel2005; Singh and Naik, Reference Singh and Naik2006). The insect is abundant in India, Sri Lanka, Burma, Fiji, Indo-china, Japan, Australia, Netherlands, Samoa, Mauritius, Tonga Island, French West Africa, French Equatorial Africa, French Sudan and USA (Patel and Kulkarny, Reference Patel and Kulkarny1956; Peter and David, Reference Peter and David1991; Nagaraju et al., Reference Nagaraju, Nadagouda, Hosamani and Hurali2018). However, we did not find literature on the biology of D. indica on T. anguina.

Synthetic insecticides such as carbaryl, dimethoate, dihydroxycarb and methomyl are commonly applied to control the insect pest, D. indica (Butani, Reference Butani1975; Schreiner, Reference Schreiner1991; Wang and Huang, Reference Wang and Huang1999; Roopa et al., Reference Roopa, Rajashekara, Ramakrishna and Venkatesha2014). But, applications of chemical insecticides are not safe for environmental-health and non-target organisms. Several biopesticides such as Beauveria bassina, Nomurea rileyi, Dipel (a commercial product of Bacillus thruriengiensis) and Helicoverpa armigera nucleopolyhedrovirus (HaNPV) are fruitful for control of this insect pest in laboratory conditions (Roopa et al., Reference Roopa, Rajashekara, Ramakrishna and Venkatesha2014). But, till date, commercial biopesticides are not available in the market. Therefore, a host-plant resistant program is of considerable interest to achieve an efficient and safe control. Different cultivars of a host plant can differ in physiological and morphological characteristics including wax content, nutritional content as well as secondary metabolites (Golizadeh et al., Reference Golizadeh, Ghavidel, Razmjou, Fathi and Hassanpour2017a, Reference Golizadeh, Jafari-Behi, Razmjou, Naseri and Hassanpour2017b; Mobarak et al., Reference Mobarak, Roy and Barik2020), which can affect the development, survival, longevity of adults, reproduction and fecundity of an insect pest.

Construction of life table is very useful to observe the development, survival and reproductive potential of an insect population, which is a popular method to measure various parameters of an insect and this, is necessary for the control of an insect pest (Chi and Getz, Reference Chi and Getz1988; Southwood and Henderson, Reference Southwood and Henderson2000; Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Tao, Chi, Wan and Chu2017). However, the traditional life table does not consider both sexes of an insect, while using age-stage, two-sex life table we can precisely determine the characteristics of an insect population such as stage differentiation, individual differences and male population (Chi, Reference Chi1990; Chi and Su, Reference Chi and Su2006; Huang and Chi, Reference Huang and Chi2011; Mobarak et al., Reference Mobarak, Roy and Barik2020).

Therefore, the objectives of the present study were to (i) construct age-stage, two-sex life table of D. indica to record the development, longevity and reproductive potential of D. indica on the leaves of three T. anguina cultivars (Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1 are currently grown in West Bengal, India due to high yielding potential), (ii) explore the food utilization efficiency measures of D. indica by feeding on the leaves of three T. anguina cultivars, (iii) determine the amylolytic and proteolytic activities of the fifth-instar larvae of D. indica by feeding on the leaves of three T. anguina cultivars, and (iv) understand the probable effect of various nutrients (total carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, amino acids and nitrogen) and antinutrients (total phenols, flavonols and tannins) present in the leaves of three T. anguina cultivars on the development, survival and reproductive potential of D. indica. The findings of this study could be useful in the selection of partially resistant T. anguina cultivar, which can contribute useful data for further T. anguina breeding program and effective management of D. indica.

Materials and methods

Host plants

Seeds of three T. anguina cultivars [Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1 {Baruipur Long and MNSR-1 were originated from India, while Polo No. 1 (F1 Hybrid) was originated from Thailand}] were separately cultivated at the Crop Research Farm (CRF), University of Burdwan (23°16′ N, 87°54′ E), West Bengal, India. Each T. anguina cultivar was attacked by the larvae of D. indica during early May 2018 in the field.

To get leaves from uninfested plants of each T. anguina cultivar, seeds of plants in earthen pots containing ca. 1500 cm3 of soil were grown in the CRF, The University of Burdwan between May and August 2018 under a natural photoregime of 13L: 11 D at 30–37°C. Each plant with the pot was covered by a fine mesh nylon net [100 cm (height) × 60 cm (diameter)] to protect plants from insect damage and unintentional infection. Insecticides were not applied to these plants.

Insect culture

Fifth-instar larvae of D. indica were collected from each cultivar of T. anguina plants growing at the CRF of the University of Burdwan during mid-June 2018. Larvae were taken into the laboratory and transferred on same leaves in glass jars (20 cm diameter × 30 cm height) from which cultivar they were collected. A pair of newly emerged male and female was transferred in a glass jar (20 cm diameter × 30 cm height) for mating and egg-laying (n = 5 pairs of male and female for each cultivar of T. anguina), containing leaves of the same cultivar from which fifth-instar larvae were collected. Eggs (50) laid by females on the fourth day were collected from the leaves of each T. anguina cultivar (Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1). The eggs were separately used for culture in the leaves of each T. anguina cultivar for three generations.

Life table study

Newly emerged fourth-generation adults raised from caterpillars (the sexes were separated by the presence of a tuft of light brown hairs on the tip of the abdomen, which are bushier in female than that of male), which were fed with three generations on the leaves of the same cultivar, were used for the construction of life table. Newly emerged adults (male and female) were placed in fine-mesh nylon net cages (25 × 25 × 25 cm3) for mating and egg-laying (newly emerged males and females mate on the second day of emergence), and same-aged eggs were collected on the fourth day. Groups of 100 eggs collected from females, on which cultivar they were maintained, were employed to construct age-stage, two-sex life table of D. indica on the leaves of each T. anguina cultivar. Each egg was used as a replicate on the leaves of a particular cultivar. Leaves were changed at 24 h interval. To prevent moisture loss from leaves, a moist piece of cotton was placed around the petiole of each fresh mature leaf, which was covered by an aluminium foil to prevent moisture loss. Each larva was transferred into a glass jar (3 cm diameter × 5 cm length) with leaves from a particular T. anguina cultivar until pupation. Each pupa was transferred into a separate glass jar (8 cm diameter × 10 cm length). Development stages, the fate of each larva (dead or alive), larval moulting, pupation time and the emergence of each adult were recorded at 24 h interval. The length and breadth of eggs, and larval instars by feeding on the leaves of a particular cultivar (Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1) were measured to observe the growth of D. indica (egg and first instar were measured by microscope fitted with an objective lens of 10X attached with oculometer ERMA Japan, while from second to fifth instars were measured on millimetre graph paper) (n = 10). Further, the length and breadth of the pupa and newly emerged adults were measured on millimetre graph paper (n = 10). The longevity of each adult (emergence to death) was noted at 24 h interval.

Fecundity of D. indica through lifetime was recorded on the leaves of each T. anguina cultivar, on which larvae were reared. The adult pre-oviposition period (APOP: the period between the emergence of an adult female and her first oviposition), total pre-oviposition period (TPOP: the time interval from birth to the beginning of oviposition), oviposition days, daily fecundity and total fecundity (number of eggs produced during the reproductive period) were recorded on the leaves of each cultivar (Chi, Reference Chi1988; Chi and Su, Reference Chi and Su2006).

Raw data on the survival, development and oviposition of all individuals were analysed based on age-stage, two-sex life table theory (Chi and Liu, Reference Chi and Liu1985; Chi, Reference Chi1988) using the computer program TWOSEX-MSChart (Chi, Reference Chi2017a). The parameters calculated were: age-stage-specific survival rate (sxj, x: age and j: stage), age-specific survival rate (lx), age-stage specific fecundity (fxj), age-specific fecundity (mx), age-stage life expectancy (exj), age-stage reproductive value (vxj).

The potential population growth of D. indica on three T. anguina cultivars (Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1) was projected according to Chi and Liu (Reference Chi and Liu1985) & Chi (Reference Chi1990) to forecast the future population size and age-stage structure by using the TIMING-MSChart program (http://140.120.197.173/Ecology/Download/Timing-MSChart.rar) (Chi, Reference Chi2017b).

Food utilization indices

Newly emerged fourth-generation first-instar larvae that had been fed with the leaves of a particular T. anguina cultivar (Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1) were used for this experiment. Before placing larvae on the leaves of a particular cultivar, larvae and leaves were weighed. Larvae were allowed to feed for 24 h and leaves remained after 24 h of feeding were reweighed. Sample leaves from each cultivar prior to larval feeding and after 24 h of feeding were weighed, oven dried for 72 h at 50 ± 1°C and reweighed to determine the dry weight of the diet supplied to the larvae. The amount of food consumed by larvae was determined by recording the difference between the total dry weight of diet supplied initially and dry weight of diet remained after 24 h interval. Five replicates (each replicate contained ten larvae, n = 10) were conducted on the leaves of a particular cultivar. The fresh weight gain of larvae on the leaves of a particular cultivar during the period of study was determined by recording the differences in the weight of larvae at 24 h interval. Faeces were collected at 24 h interval and weighed, and then placed in a hot air oven and reweighed to find the dry weight of excreta.

The parameters of food utilization indices, i.e., growth rate (GR), consumption rate (CR), relative growth rate (RGR), consumption index (CI), egestion rate (ER), host consumption rate (HCR), approximate digestibility (AD), the efficiency of conversion of ingested food (ECI) and efficiency of conversion of digested food (ECD) all based on dry weight were determined by the formulas of Waldbauer (Reference Waldbauer1968) (Supplementary material S1).

Enzymatic activity of larvae

Fourth-generation fifth instar D. indica larvae that were fed with the leaves of a particular T. anguina cultivar for three generations were used to determine enzymatic activity. For each cultivar, fifth-instar larvae (second day) were placed in ice for paralysis, and after that larvae (n = 5) were rapidly dissected under a stereomicroscope. The haemolymph was cleaned with precooled distilled water, and the extraneous tissues were removed from midguts. Midguts including contents were homogenized in 1 ml of 10 mM NaCl by a glass homogenizer. The solution was centrifuged at 12,000 g at 4°C for 15 min. The supernatant was collected for enzymatic assays and stored at −20°C until use.

Non-specific amylolytic activity of midgut extracts was determined according to Bernfeld (Reference Bernfeld1955) with some modifications by Mohammadzadeh et al. (Reference Mohammadzadeh, Bandani and Borzoui2013). The optimum pH on α-amylase activity in the midgut extracts of D. indica larvae was determined by incubation of the reaction mixture with pH set at 7–12. Soluble starch (1% w/v) as a substrate was added in 20 mM glycine–NaOH buffer (pH 11.5). One-hundred μl of the enzyme extract was added with glycine–NaOH buffer (500 μl; pH 11.5) at 37°C. The reaction began when 200 μl of 1% soluble starch was added and stopped 30 min later by the addition of 300 μl of dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) and heating in boiling water for 10 min. Each treatment was replicated five times including blanks in which substrate was added after DNS, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm in the UV-visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, UV-1800240V). The result was expressed as mg maltose per min (one unit of α-amylase activity was defined as the quantity of enzyme required to produce 1 mg maltose at 37°C per min).

Total general proteolytic activity from enzyme extracts was estimated by the protocol of Elpidina et al. (Reference Elpidina, Vinokurov, Gromenko, Rudenskaya, Dunaevsky and Zhuzhikov2001) using azocasein as a substrate at the pH optimum. The buffer (20 mM glycine–NaOH buffer) was used to determine the pH optimum of proteolytic activity over a pH range of 7–12. Azocasein (1.5% w/v) as a substrate was mixed in 20 mM glycine–NaOH buffer (pH 9.0). Enzyme extracts (100 μl) were added with 200 μl azocasein and 300 μl of 20 mM glycine–NaOH buffer (pH 9.0) at 37°C. The enzymatic reactions were stopped by addition of 30% of 300 μl trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The solution was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min and the supernatant monitored spectrophotometrically at 440 nm. The absorbance from the supernatant was measured at 440 nm in the UV-visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, UV-1800240V). Each treatment was replicated five times including blanks in which substrate was added after TCA, and the result was expressed as mU min−1 (one unit is defined as the amount of enzyme that is required to hydrolyse azocasein to give 1 μg of tyrosine in 1 min at 37°C at certain pH).

Biochemical analysis of leaves

The nutritional parameters from the leaves of three T. anguina cultivars (Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1) were estimated by using 1 g fresh leaves of respective type to various biochemical analysis such as total carbohydrates (Dubois et al., Reference Dubois, Gilles, Hamilton, Rebers and Smith1956), total proteins (Lowry et al., Reference Lowry, Rosebrough, Farr and Randall1951), total lipids (Folch et al., Reference Folch, Lees and Sloane-Stanley1957), total amino acids (Moore and Stein, Reference Moore and Stein1948), total phenols (Bray and Thorpe, Reference Bray and Thorpe1954) and total flavonols (Howell et al., Reference Howell, Bell and Stipanovic1976). Dried leaves were used for determination of total tannins (Scalbert, Reference Scalbert, Hemingway and Laks1992) and total nitrogen (Vogel, Reference Vogel1958) as the water content in fresh leaves may interfere with satisfactory estimations. Each biochemical analysis was replicated five times.

Estimation of moisture content

One gram fresh leaves from each T. anguina cultivar (Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1) was placed in a hot-air oven for 72 h at 50 ± 1°C and the dried leaves were weighed in a balance (±0.01 mg). The water content was determined by recording the difference between fresh and dry weights of leaves (n = 5). The moisture content for leaves of three cultivars was replicated five times.

Statistical analysis

The means and standard errors of life table parameters were estimated by bootstrap technique (Efron and Tibshirani, Reference Efron and Tibshirani1993) with 100,000 replications, which is present in the TWOSEX-MS Chart program containing whether the data are normally distributed (Chi, Reference Chi2017a). The paired bootstrap (Chi, Reference Chi2017a, Reference Chi2017b) was used to evaluate the differences at the 5% significance level in the development time, adult longevity, adult preoviposition period (APOP), total preoviposition period (TPOP), oviposition period and fecundity, and life table parameters (r, λ, R 0 and T) among three T. anguina cultivars. Data on different feeding indices of D. indica and enzymatic activity of the fifth-instar larvae among treatments and the biochemical properties of three T. anguina cultivars were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's test (HSD) (Zar, Reference Zar1999). The Pearson correlation coefficient analysis was applied to observe the relationship between the life table parameters of D. indica and chemical properties (nutrient and antinutrients metabolites) of the leaves of three T. anguina cultivars. All the statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS (version 13.0) software.

Results

Development, survival and oviposition of D. indica

Effect of three T. anguina cultivars (Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1) on the development time of five larval instars, pupal duration and longevity of D. indica adults were presented in table 1. The incubation time of eggs was the longest on Polo No. 1 followed by Baruipur Long and the shortest on MNSR-1. Except for second instar, where larval duration was longer on Baruipur Long and Polo No. 1 than MNSR-1, the development time of first, third, fourth and fifth instars were the longest on Polo No. 1 followed by Baruipur Long and the shortest on MNSR-1. The pupal duration was the longest on Polo No. 1, intermediate on Baruipur Long and the shortest on MNSR-1. The preadult duration (from egg to adult emergence) was completed earliest on MNSR-1 followed by Baruipur Long and the slowest on Polo No. 1. The longevities of adult males and females were the longest on MNSR-1, intermediate on Baruipur Long and the shortest on Polo No. 1.

Table 1. Development time and adult longevity (mean ± SE) of Diaphania indica on three Trichosanthes anguina cultivars

Standard errors were estimated using 100,000 bootstrap resampling. Data followed by different lower-case letter within the row were significantly different based on a paired bootstrap test at 5% level of significance.

Table 2 shows different morphological features of D. indica fed with three T. anguina cultivars (Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1). The length and breadth of eggs, and first instar of D. indica were higher on MNSR-1 than Polo No. 1. The length of third instar was the highest on MNSR-1 followed by Baruipur Long and the shortest on Polo No. 1, but there were no significant differences in the breadth of insects fed with three T. anguina cultivars. The length and breadth of last two instars (fourth and fifth) were the highest on MNSR-1 followed by Baruipur Long and the shortest on Polo No. 1. The data on head capsule width from first to fifth instar of D. indica fed with three T. anguina cultivars (Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1) are presented in Supplementary table 1. The head capsule width of the fifth instar was greater on MNSR-1 than Baruipur Long and Polo No. 1. The length and breadth of pupa, and newly emerged adults (male and female) were smaller on Polo No. 1 than MNSR-1 (table 2).

Table 2. Morphological features of Diaphania indica [n = 10, mean (mm) ± SE] reared on three Trichosanthes anguina cultivars under laboratory conditions (27 ± 1°C, 65 ± 5% r.h. and 12L:12D)

Means followed by different letters for length or breadths of D. indica within the rows are significantly different by Tukey's test at 5% level of significance.

a Newly emerged.

The APOP, TPOP, oviposition days and fecundity of adult D. indica emerged from larvae fed with three T. anguina cultivars are presented in table 3. The APOP was higher on Polo No. 1 than Baruipur Long and MNSR-1, while oviposition days were higher on Baruipur Long and MNSR-1 than Polo No. 1. The TPOP was the longest on Polo No. 1 followed by Baruipur Long and the shortest on MNSR-1. Fecundity was the highest on MNSR-1 followed by Baruipur Long and the lowest on Polo No. 1.

Table 3. Mean (±SE) of adult preoviposition period (APOP), total preoviposition period (TPOP), oviposition period and fecundity of Diaphania indica emerging from larvae reared on three Trichosanthes anguina cultivars

Standard errors were estimated using 100,000 bootstrap resampling. Data followed by different lower-case letter within the row were significantly different based on a paired bootstrap test at 5% level of significance.

The sxj (an individual will survive to age x and stage j) curves of D. indica on three T. anguina cultivars were overall similar (Supplementary fig. 1). The female curves emerged at age 20 d, 22 d and 18 d on Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1, respectively; whereas male curves emerged at age 21 d, 23 d and 17 d on Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1, respectively (Supplementary fig. 1a–c).

The curves of age-stage specific fecundity (fxj) demonstrated variation in the egg-laying performance of D. indica on three T. anguina cultivars (Supplementary fig. 2). The fxj and age-specific fecundity (mx) on Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1 started at 21, 24 and 20 d, respectively (Supplementary fig. 2a–c). The maximum daily oviposition rates were the highest on MNSR-1, intermediate on Baruipur Long and the lowest on Polo No. 1. The females started to oviposit on 21 d and continued up to 33 d on Baruipur Long, while females started to oviposit on 24 d and ended at 34 d on Polo No. 1, but females began to oviposit on 20 d and ended on 29 d on MNSR-1. The highest fxj and mx peaks of D. indica on Baruipur Long were 25 and 26 d, respectively, while the highest fxj and mx peaks on Polo No. 1 were recorded on 30 d, and the highest fxj and mx peaks on MNSR-1 were 23 d (Supplementary fig. 2a–c). We recorded the highest age-specific maternity (lxmx) on 25, 29 and 23 on Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1, respectively (Supplementary fig. 2a–c).

The age-stage specific life expectancy is the probability that an individual of age x and stage j is expected to live. The life expectancies of D. indica at age zero (e 01) were 20.80, 20.05 and 19.75 d on Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1, respectively, which are due to individuals of the same age can develop to different stages, and these individuals will show different life expectancies (Supplementary fig. 3). The maximum life expectancies of female and male D. indica on Baruipur Long were 36 d and 34 d, respectively (Supplementary fig. 3a). The maximum life expectancies of female and male on Polo No. 1 were 36 d (Supplementary fig. 3b), while the maximum life expectancies of female and male were 32d when fed with MNSR-1 (Supplementary fig. 3c).

The age-stage reproductive value (vxj) represents the contribution of age x and stage j to the future population. The reproductive value of a new-born individual (v01), finite rate of increase, on Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1 were 1.157, 1.118 and 1.202 day−1, respectively (Supplementary fig. 4a–c). Females began to emerge at age 20, 22 and 18 days on Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1, respectively, and subsequently, reached its peak values to 149.65, 109.85 and 166.70 d−1 at 24, 25 and 21 d on Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1, respectively. The reproductive values were zero at age 34, 35 and 30 days on Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1, respectively, as the aged adults did not produce eggs.

The gross reproductive rate (GRR) was higher on MNSR-1 than Polo No. 1 (table 4). The intrinsic rate of increase (rm) of D. indica was the highest on MNSR-1 followed by Baruipur Long and the lowest on Polo No. 1, while the finite rate of increase (λ) was the highest on Baruipur Long, intermediate on MNSR-1 and the lowest on Polo No. 1 (table 4). The net reproductive rate (R 0) of D. indica was the highest on MNSR-1 followed by Baruipur Long and the lowest on Polo No. 1, suggesting that more offspring of D. indica would be available within one generation on MNSR-1 (table 4). The mean generation time (T, time needed for an insect population to enhance to R 0 fold of its population size at the constant age distribution) of D. indica was the longest on Polo No. 1, intermediate on Baruipur Long and the shortest on MNSR-1, indicating that the population of D. indica will enhance quicker on MNSR-1 followed by Baruipur Long and Polo No. 1 (table 4).

Table 4. Mean (±SE) of gross reproductive rate (GRR), intrinsic rate of increase (rm), finite rate of increase (λ), net reproductive rate (R 0: offspring/individual) and mean generation time (T) of Diaphania indica reared on three Trichosanthes anguina cultivars

Standard errors were estimated using 100,000 bootstrap resampling. Data followed by different lower-case letter within the row were significantly different based on a paired bootstrap test at 5% level of significance.

Population projection

The stage structures of D. indica are projected with an initial population of ten eggs using the TIMING-MSChart program (Supplementary fig. 5). After 80 days of simulation, the population growth was the highest on MNSR-1 followed by Baruipur Long and the slowest on Polo No. 1. There are 527,539 preadults and 10,401 adults (5508 females and 4893 males) on Baruipur Long, while the numbers of preadults on Polo No. 1 were 4982 and adults were 273 (147 females and 126 males). The numbers of preadults on MNSR-1 were 44,93,595 and adults were 5135 (3166 females and 1969 males).

Food utilization efficiency measurement

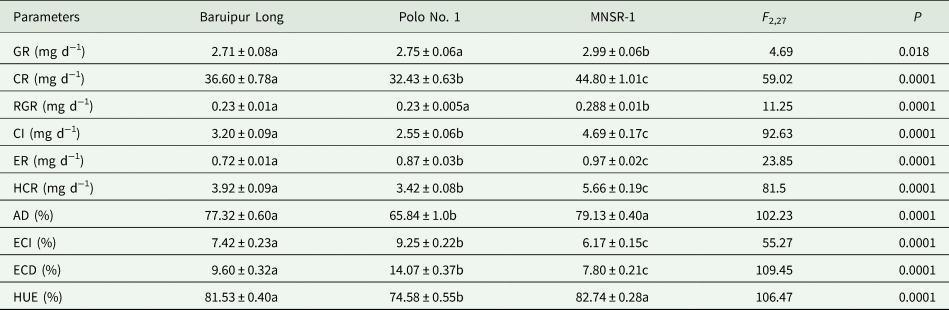

Table 5 presents food utilization efficiency measures for the fifth-instar larvae of D. indica that fed with the leaves of three T. anguina cultivars (Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1) (food utilization efficiency measures for the first to fourth-instar larvae were provided in Supplementary tables 2–5). The GR and RGR values were the highest in insects fed with MNSR-1 than Baruipur Long and Polo No. 1; whereas CR, CI and HCR values were the highest on MNSR-1 followed by Baruipur Long and the lowest on Polo No. 1 (table 5). The value of ER was the highest on MNSR-1 followed by Polo No. 1 and the lowest on Baruipur Long (table 5). Higher values of AD were recorded on MNSR-1 and Baruipur Long than Polo No. 1 (table 5). Both ECI and ECD values were the highest on Polo No. 1, intermediate on Baruipur Long and the lowest on MNSR-1 (table 5). We recorded higher value of HUE on Baruipur Long and MNSR-1 than Polo No. 1 (table 5).

Table 5. Measurement of food utilization efficiency (Mean ± SE) of the fifth-instar larvae (n = 10) of Diaphania indica reared on three Trichosanthes anguina cultivars (Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1)

Food utilization efficiency measures: GR, growth rate; CR, consumption rate; RGR, relative growth rate; CI, consumption index; ER, egestion rate; HCR, host consumption rate; AD, approximate digestibility; ECI, efficiency of conversion of ingested food; ECD, efficiency of conversion of digested food; HUE, host utilization efficiency.

Within the row means followed by same letter(s) are not significantly different by Tukey's test.

Enzymatic activity of larvae

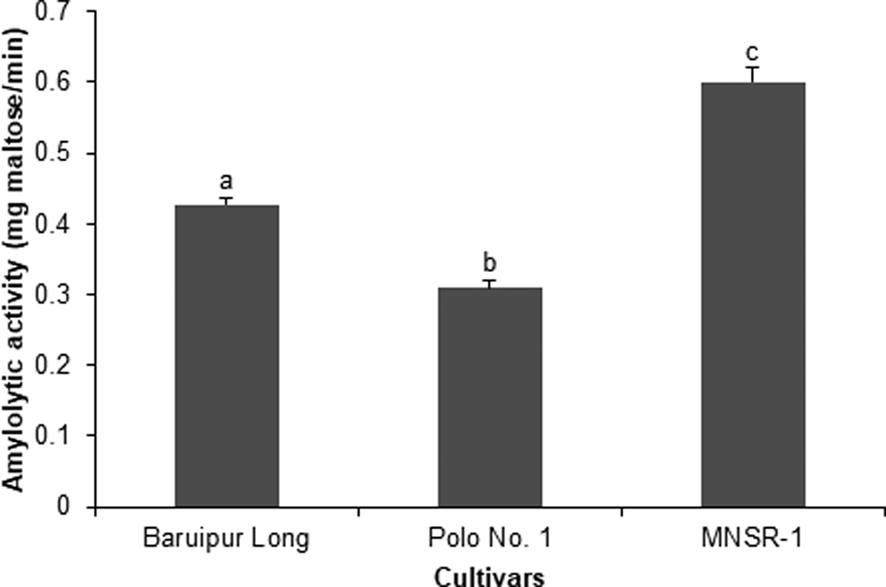

The results for non-specific amylolytic activity in the fifth-instar larvae of D. indica were significantly different among treatments (F 2,12 = 99.33, P < 0.0001), which was the highest in larvae fed with MNSR-1 (0.60 ± 0.02 mg maltose min−1) followed by Baruipur Long (0.43 ± 0.01 mg maltose min−1) and the lowest on Polo No. 1 (0.31 ± 0.01 mg maltose min−1) (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Non-specific amylolytic activity of the fifth-instar larvae of Diaphania indica (n = 5) fed with three cultivars of Trichosanthes anguina. Means followed by different letters are significantly different by Tukey's test at 5% level of significance.

General proteolytic activity in the fifth-instar larvae of D. indica was significantly affected in response to feeding on the leaves of three T. anguina cultivars (F 2,12 = 26.5, P < 0.0001) (fig. 2). Proteolytic activity was the highest in larvae fed with MNSR-1 (0.49 ± 0.02 mU min−1) followed by Baruipur Long (0.41 ± 0.01 mU min−1) and the lowest on Polo No. 1 (0.34 ± 0.01 mU min−1).

Figure 2. General proteolytic activity of the fifth-instar larvae of Diaphania indica (n = 5) fed with three cultivars of Trichosanthes anguina. Means followed by different letters are significantly different by Tukey's test at 5% level of significance.

Biochemical properties of leaves

Total carbohydrates, proteins, lipids and amino acids were the highest in MNSR-1, intermediate in Baruipur Long and the lowest in Polo No. 1 (table 6). The nitrogen content was the highest in MNSR-1 than Baruipur Long and Polo No. 1 (table 6). Total phenols, flavonols and tannins were the highest in Polo No. 1, intermediate in Baruipur Long and the lowest in MNSR-1 (table 6). The highest water content was recorded in MNSR-1 and Baruipur Long than Polo No. 1 (table 6).

Table 6. Biochemical analyses (mean ± SE) of the leaves of three Trichosanthes anguina cultivars

DWL, dry weight of leaves; FWL, fresh weight of leaves.

Means followed by different letters within the rows are significantly different by Tukey's test at 5% level of significance.

Correlation analysis

The analysis of correlation coefficients between life table parameters of D. indica fed with three T. anguina cultivars and biochemical properties of the leaves of three tested cultivars are presented in table 7. Duration of immature stages of D. indica fed with the leaves of three cultivars showed negative correlations with nutrients (total carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, amino acids and nitrogen) and moisture content, while positive correlations were observed with antinutrients (total phenols, flavonols and tannins). A positive correlation was observed between fecundity and nutrients (total carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, nitrogen and amino acids) as well as moisture content, while a negative correlation was observed between fecundity and antinutrients (total phenols, flavonols and tannins) (table 7). Positive correlations were observed for GRR, rm, λ and R 0 with nutrients (total carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, nitrogen and amino acids) and moisture content, while negative correlations were observed with antinutrients (total phenols, flavonols and tannins) (table 7). The T was negatively and positively correlated with nutrients (total carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, nitrogen and amino acids) and antinutrients (total phenols, flavonols and tannins), respectively (table 7). General proteolytic activity was positively correlated with nutrients (total carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, nitrogen and amino acids) and moisture content, while negative correlations were observed with antinutrients (total phenols, flavonols and tannins) (table 7). Non-specific amylolytic activity was positively correlated with total carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, nitrogen and moisture content, while non-specific amylolytic activity was negatively correlated with total amino acids, phenols, flavonols and tannins (table 7).

Table 7. Correlation coefficients (r) of the life table parameters of Diaphania indica reared on three Trichosanthes anguina cultivars with the nutrients, moisture content and antinutrients.

a General.

b Non-specific.

Discussion

Different cultivars of a host plant play a crucial role in population growth and food utilization of insects (Golizadeh and Razmjou, Reference Golizadeh and Razmjou2010; Alami et al., Reference Alami, Naseri, Golizadeh and Razmjou2014; Nemati-Kalkhoran et al., Reference Nemati-Kalkhoran, Razmjou, Borzoui and Naseri2018; Mobarak et al., Reference Mobarak, Roy and Barik2020). Till date, no reports are available on D. indica using age-stage, two-sex life table, and further, the biology of D. indica on T. anguina is reported for the first time. In the present study, the longest preadult duration (egg to adult emergence) was recorded on Polo No. 1 (25.72 d) followed by Baruipur Long (23.08 d) and the shortest on MNSR-1 (19.79 d), suggesting that the variation in the nutritional quality of the leaves of three T. anguina cultivars influenced the development of D. indica. Total larval development of D. indica was 8–10 d on snake gourd (Ganehiarachchi, Reference Ganehiarachchi1997), 15.22 d on gherkins (Cucumis anguria L.) (Roopa et al., Reference Roopa, Rajashekara, Ramakrishna and Venkatesha2014), 13.5 d on C. sativus L. (Fitriyana et al., Reference Fitriyana, Buchori, Nurmansyah, Ubaidillah and Rizali2015) and 9.50 d on bitter gourd (Momordica charantia L.) (Nagaraju et al., Reference Nagaraju, Nadagouda, Hosamani and Hurali2018). The variation in the nutrient and antinutrient metabolites including leaf structure of different host plants might influence the development time of D. indica on different host plants. In this study, immature stages of D. indica showed positive correlations with the antinutrients of leaves (total phenols, flavonols and tannins), suggesting that antinutrients caused a delayed growth of D. indica to reach the adult stage. Koner et al. (Reference Koner, Debnath and Barik2019) showed positive correlations between immature stages of Galerucella placida Baly (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) and antinutrients of Rumex dentatus L. and Polygonum glabrum Willd. (Polygonaceae) leaves.

The fecundity of D. indica on snake gourd, gherkin and cucumber was 267, 116.5 and 250.21 eggs during lifetime, respectively (Ganehiarachchi, Reference Ganehiarachchi1997; Roopa et al., Reference Roopa, Rajashekara, Ramakrishna and Venkatesha2014; Nagaraju et al., Reference Nagaraju, Nadagouda, Hosamani and Hurali2018); whereas in this study, the fecundity of D. indica was the highest on MNSR-1 (259 eggs), intermediate on Baruipur Long (203.68 eggs) and the lowest on Polo No. 1 (151.22 eggs), implicating that variations in fecundity among host plants as well as different cultivars of a host plant could be due to differences in quality and quantity of food consumed by the larvae of D. indica during larval stages (Razmjou et al., Reference Razmjou, Naseri and Hemati2014). In the current study, there is a negative correlation between the fecundity of D. indica and antinutrients of three T. anguina cultivars, suggesting that antinutrients of leaves played an inhibitory role which influenced the egg-laying performance of D. indica. The lowest fecundity of D. indica on Polo No. 1 suggested that the poor nutritional quality of Polo No. 1 than the other two cultivars of T. anguina determines the least performance of D. indica on Polo No. 1.

The intrinsic rate of increase (rm) and finite rate of increase (λ) can exactly predict the overall population growth, development and fecundity of an insect population, and are considered as important parameters in measuring population growth potential (Karimi-Pormehr et al., Reference Karimi-Pormehr, Borzoui, Naseri, Dastjerdi and Mansouri2018; Nemati-Kalkhoran et al., Reference Nemati-Kalkhoran, Razmjou, Borzoui and Naseri2018; Das et al., Reference Das, Koner and Barik2019; Mobarak et al., Reference Mobarak, Roy and Barik2020). The rm was the lowest on Polo No. 1 (0.1112 d−1) and the highest on MNSR-1 (0.1841 d−1), suggesting that poor nutritional quality of Polo No. 1 are the effective factor for delayed development of D. indica. The rm of D. indica on C. sativus is 0.1 individual female−1 d−1, while the net reproductive rate (R 0) is 51 individuals female−1 (Fitriyana et al., Reference Fitriyana, Buchori, Nurmansyah, Ubaidillah and Rizali2015). The R 0 indicates fecundity as well as survival characters, which was the highest on MNSR-1 (82.88 offspring/individual) and the lowest on Polo No. 1 (27.22 offspring/individual). The T indicates as the period that a population needed to enhance R 0 fold of its size when time at infinity and the population approaches a stable age distribution, which was the fastest on MNSR-1 (23.99 days) and the slowest on Polo No. 1 (29.70 days). This study revealed that T of D. indica fed with three T. anguina cultivars was positively correlated with the antinutrients of leaves (total phenols, flavonols and tannins), implicating that the antinutrients of leaves influenced prolonged generation time of D. indica (Koner et al., Reference Koner, Debnath and Barik2019). Here, the finite rate of increase (λ) of D. indica was the lowest on Polo No. 1 (1.1177 d−1) than the other two cultivars tested in this study, indicating that D. indica fed with Polo No. 1 exhibited a slower growth rate and longer generation time among three T. anguina cultivars. The above results suggested that Polo No. 1 is the least suitable cultivar for the development and reproduction of D. indica due to lower amount of nutrients and a higher amount of antinutrients.

Phenols serve as defensive agents against feeding by herbivores and attack by nematodes including fungal and bacterial pathogens (Harborne, Reference Harborne2003). Tannins, an anti-herbivore component, reduce the digestibility of substances (Harborne, Reference Harborne2003), while flavonols help to protect plants from insect attack by influencing behaviour as well as growth and development of insect herbivore (Treutter, Reference Treutter2006; War et al., Reference War, Paulraj, Ahmad, Buhroo, Hussain, Ignacimuthu and Sharma2012). Our findings on the biochemical properties of leaves of three T. anguina cultivars suggested that Polo No. 1 is of poor nutritional quality than MNSR-1 and Baruipur Long because nutrients such as total carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, amino acids and nitrogen content were the lowest in Polo No. 1 than the other two cultivars used in this study; whereas antinutrients or secondary metabolites such as total phenols, flavonols and tannins were the highest in Polo No. 1 than the other two cultivars. This could be the probable explanation for lower growth and development including fecundity of D. indica feeding on Polo No. 1 than MNSR-1 and Baruipur Long. Low water content in the leaves of host plants reduces survivability of insect herbivores. The lowest water content in the leaves of Polo No. 1 than MNSR-1 and Baruipur Long could be another explanation for lower survivability of D. indica on Polo No. 1 (Mattson and Scriber, Reference Mattson, Scriber, Slansky and Rodriguez1987; Roy and Barik, Reference Roy and Barik2012, Reference Roy and Barik2013; Mobarak et al., Reference Mobarak, Roy and Barik2020). The food consumed by the larvae of Lepidoptera could influence the reproductive potential of adults (Razmjou et al., Reference Razmjou, Naseri and Hemati2014). Therefore, this study suggests that the differences in the fecundity of D. indica on three T. anguina cultivars might be due to variations in nutritional quality and quantity as well as secondary metabolites in host cultivars (Sarfraz et al., Reference Sarfraz, Dosdall and Keddie2007; Golizadeh et al., Reference Golizadeh, Ghavidel, Razmjou, Fathi and Hassanpour2017a, Reference Golizadeh, Jafari-Behi, Razmjou, Naseri and Hassanpour2017b).

The ability of an insect herbivore to utilize host cultivars depends on the conversion of food by ingestion and assimilation into body tissues, which influences development, fecundity and survival of adults (Awmack and Leather, Reference Awmack and Leather2002; Genc, Reference Genc2006). Therefore, quality of host plant plays an important role in the growth and reproductive performance of an insect herbivore (Awmack and Leather, Reference Awmack and Leather2002; Razmjou et al., Reference Razmjou, Naseri and Hemati2014; Mukherjee et al., Reference Mukherjee, Karmakar and Barik2017; Malik et al., Reference Malik, Das and Barik2018). The midgut amylolytic activity of D. indica fed with three T. anguina cultivars was positively correlated with total carbohydrates, proteins, lipids and nitrogen, while proteolytic activity was positively correlated with total carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, amino acids and nitrogen, suggesting that the nutritional quality of leaves played an important role in the synthesis and secretion of enzymes as well as digestion of consumed foods. The amylolytic and proteolytic activities of the larvae of D. indica were the highest on MNSR-1 and lowest on Polo No. 1, suggesting that D. indica had a high ability to utilize the leaves of MNSR-1 than Polo No. 1. This observation indicated that digestive performance of insects fed with MNSR-1 would lead to higher survival and increased biological fitness (Srinivasan et al., Reference Srinivasan, Chougule, Giri, Gatehouse and Gupta2005; Bouayad et al., Reference Bouayad, Rharrabe, Ghailani and Sayah2008; Naseri et al., Reference Naseri, Fathipour, Moharramipour, Hosseininaveh and Gatehouse2010; Borzoui and Bandani, Reference Borzoui and Bandani2013; Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Kaur and Gupta2014; Borzoui and Naseri, Reference Borzoui and Naseri2016). In the present study, variations in the parameters of nutritional indices of D. indica were recorded when the insects were fed with the leaves of three T. anguina cultivars (Baruipur Long, Polo No. 1 and MNSR-1). The approximate digestibility (AD) influences the growth rate (GR) of an insect (Shobana et al., Reference Shobana, Murugan and Naresh Kumar2010; Xue et al., Reference Xue, Pang, Wang, Li and Liu2010; Sarkar et al., Reference Sarkar, Mukherjee and Barik2016). Fifth-instar larvae of D. indica showed higher AD and GR when fed with MNSR-1 than Polo No. 1, suggesting that better suitability of MNSR-1 resulted shorter development time and higher fecundity of D. indica.

In conclusion, the development, longevity and reproduction of D. indica were influenced by the nutritional quality in terms of primary essential nutrients and secondary metabolites present in the leaves of three T. anguina cultivars. Our study showed that the prolonged development time and lowest fecundity of D. indica caused the lower intrinsic rate of increase and net reproductive rate of D. indica on Polo No. 1, suggesting that the lower population growth of D. indica could result in lower subsequent infestations. Therefore, the use of partially resistant Polo No. 1 cultivar could be recommended for cultivation. Further research into the potential of using Polo No. 1 cultivar with other control strategies in the integrated pest management programme (IPM) of D. indica in field conditions is necessary.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485320000255.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank anonymous reviewer(s) for many helpful suggestions of an earlier version of the manuscript. The financial assistance from the UGC-JRF, New Delhi, Govt. of India to Rahul Debnath [F.No. 16-6(DEC. 2017)/2018(NET/CSIR)] is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank Dr M. Alma Solis, Research Entomologist, SEL, USDA, Smithsonian Institution, Washington for authenticating the insect. The authors are thankful to DST PURSE Phase-II for providing necessary instrumental facilities.