Introduction

In 2010 a leafminer of the genus Coptodisca Walsingham (Lepidoptera: Heliozelidae) was collected for the first time in Europe, both on black walnut (Juglans nigra L.) and common walnut (Juglans regia L.) (Juglandaceae) (Bernardo et al., Reference Bernardo, Sasso, Gebiola and Viggiani2011, Reference Bernardo, Sasso, Gebiola and Viggiani2012). Coptodisca is a Nearctic genus that includes 18 described species of tiny leafminer moths (Lafontaine, Reference Lafontaine1974; Davis, Reference Davis, Hodges, Dominick, Davis, Ferguson, Franclemont, Munroe and Powell1983; Reference Davis and Kristensen1998, online Supplementary material 3). Currently, there is only one dichotomous key for identifying the five Coptodisca species that feed on Ericaceae (Lafontaine, Reference Lafontaine1974). Species are described mostly on the basis of forewing colour pattern (Chambers, Reference Chambers1874; Busck, Reference Busck1878; Braun, Reference Braun1916; Dietz, Reference Dietz1921). The genitalia have been described or illustrated for only four species (Opler, Reference Opler1971; Lafontaine, Reference Lafontaine1974) and these descriptions and illustrations are inadequate for taxonomic purposes. Therefore, identification of adults is nearly impossible when the host plant is unknown. In addition, DNA sequences have thus been published for Coptodisca kalmiella Dietz (Pellmyr & Leebens-Mack, Reference Pellmyr and Leebens-Mack1999; Wiegmann et al., Reference Wiegmann, Regier and Mitter2002); and Coptodisca lucifluella (Clemens) (as C. ella: van Nieukerken et al., Reference Nieukerken, Wagner, Baldessari, Mazzon, Angeli, Girolami and Doorenweerd2012), which limits the use of a molecular identification approach.

Adults of all Coptodisca species share a forewing that is whitish or metallic silver in the basal half and golden or yellow in the apical half, with two opposing white triangles at two-thirds of the length of the wing, and a black apical patch. Individuals of some species have a greater or lesser suffusion of dark-grey scaling on the basal part of the forewing (Davis, Reference Davis and Kristensen1998).

As in the other Heliozelidae, Coptodisca females pierce the underside of a leaf using a greatly extensible, piercing ovipositor to lay eggs singly within the leaf (Davis, Reference Davis and Kristensen1998). After hatching, the developing larva excavates a mine in the host leaf by eating the mesophyll. Once mature, the larva constructs a flat, oval case by cutting a disc from the upper and lower epidermis of the mine and joins them with silk to form a cocoon (Davis, Reference Davis and Kristensen1998). In most instances, the larvae produce a silk strand to reach the ground, and there pupate among leaf litter or by attaching their cases to the bark or leaves of the host plant. Abandoned mines with small oval holes are characteristic of the leaf damage caused by these leafminers.

Coptodisca species have one or more generations annually (Slingerland & Crosby, Reference Slingerland and Crosby1914; Weiss & Beckwith, Reference Weiss and Beckwith1921; Hileman & Lieto, Reference Hileman and Lieto1981; Maier, Reference Maier1988; Davis, Reference Davis and Kristensen1998), and overwinter as a larva inside a cocoon case (Braun, Reference Braun1916; Weiss & Beckwith, Reference Weiss and Beckwith1921) or as an egg (in case of evergreen plants: Opler, Reference Opler1971; Hileman & Lieto, Reference Hileman and Lieto1981; Maier, Reference Maier1988; Hespenheide, Reference Hespenheide1991; Rickman & Connor, Reference Rickman and Connor2003), with pupation and adult emergence occurring the following spring (Slingerland & Crosby, Reference Slingerland and Crosby1914; Davis, Reference Davis and Kristensen1998). Hibernating diapausing pupae have been recorded only for C. lucifluella and an unidentified species (Brown & Eads, Reference Brown and Eads1969; Heyerdahl & Dutcher, Reference Heyerdahl and Dutcher1990). The pupal exuviae protrude from the case upon eclosion (Weiss & Beckwith, Reference Weiss and Beckwith1921; Payne et al., Reference Payne, Tedders, Cosgrove and Foard1972).

The only named species of Coptodisca known to attack walnut trees is the North-American walnut shield bearer C. juglandiella (Chambers, Reference Chambers1874), which has been recorded to feed only on the black walnut, J. nigra (Chambers, Reference Chambers1874). A precise characterization of the invasive species and a good knowledge of its current geographical distribution are the first essential steps in evaluating its potential hazard and defining management options. Therefore, the first aim of this paper was to provide a morphological and molecular characterization of the leafminer. Secondly, several different biological parameters were studied (cycle, number of generations, mortality, distribution on trees, etc.), as there was little known about the biology of this leafminer and its biology could be affected by association with different host plants and by its invasion into a new area. Finally, the level of infestation and the kind and the intensity of damage in walnut orchards were studied to evaluate the necessity of pest control.

Material and methods

Taxonomic characterization

Morphological analysis

To identify Coptodisca, we compared the specimens with the original descriptions of the genus Coptodisca (as Aspidisca: Clemens, Reference Clemens1860) and all of its species (checklist in online Supplementary material 3). In addition, we compared the specimens collected in Italy with available type material, with additional museum material borrowed from North-American collections, and with the specimens recently collected in North America by EJvN (see online Supplementary material 1 for details).

Morphological details were taken from mounted dry specimens or dissected specimens mounted on permanent slides in balsam–phenol or euparal. For morphological methods (dissection and photographing of genitalia and wings) and terminology see van Nieukerken et al. (Reference Nieukerken, Wagner, Baldessari, Mazzon, Angeli, Girolami and Doorenweerd2012). Male genitalia of Coptodisca are difficult to dissect and embed in a fixed position, because of their small size and almost cylindrical shape; we therefore studied genitalia first in glycerine. The number of antennal segments in adult moths was counted in preparations of descaled adults (see the species description below).

Molecular analysis

We used part of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase c subunit I (COI) gene, also known as the ‘DNA barcode marker for animals’; a widely used marker suitable for systematics at the species level (Hebert et al., Reference Hebert, Penton, Burns, Janzen and Hallwachs2004). Previously as phylogenetic reconstruction had not been attempted for the genus Coptodisca, and to have a robust inference we included eight species for which fresh material was available and that could be identified to species (C. arbutiella Busck, C. juglandiella, C. kalmiella, C. lucifluella, C. negligens Braun, C. quercicolella Braun, C. saliciella Clemens, C. splendoriferella Clemens) plus three specimens that could not be assigned to any known species (here indicated as Coptodisca sp. 1, 2 and 3). A total of 28 specimens were selected for molecular analyses (table 1). DNA from the abdomen of dry specimens or from fresh larvae killed and stored in alcohol was extracted using a Chelex–proteinase K-based protocol as in Gebiola et al. (Reference Gebiola, Bernardo, Monti, Navone and Viggiani2009) for Italian specimens and the Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit or a Macherey Nagel magnetic bead tissue kit on an automated KingFisher flex system for American specimens. Some extractions from the abdomen of adults or larvae were non-destructive, such that genitalia and larval pelts could be mounted in euparal on slides (Knölke et al., Reference Knölke, Erlacher, Hausmann, Miller and Segerer2005). COI barcodes were obtained using the primers LCO1490 and HCO2198 (Folmer et al., Reference Folmer, Black, Hoeh, Lutz and Vrijenhoek1994) or LepF and LepR (Hajibabaei et al., Reference Hajibabaei, Smith, Janzen, Rodriguez, Whitfield and Hebert2006); the latter sometimes coupled with the internal primers MH-MR1 and MF1, respectively (Hajibabaei et al., Reference Hajibabaei, Smith, Janzen, Rodriguez, Whitfield and Hebert2006). For American samples, universal tails (for example, M13 or a combination of T7 promotor and T3) were attached to the primers to increase yield and to facilitate higher throughput (Regier & Shi, Reference Regier and Shi2005). PCR cycles were as in Gebiola et al. (Reference Gebiola, Bernardo, Monti, Navone and Viggiani2009). Amplicon size was checked on a 1.2% agarose gel, then the DNA was purified and sequenced at XiLin sequencing in Beijing, China (Italian specimens) or at Macrogen Europe or Baseclear, Leiden (American specimens). Ambiguous sections of chromatograms from Italian specimens were edited by eye using BioEdit (Hall, Reference Hall1999), while Sequencher 4.2 (Gene Codes Corporation) or Geneious R6 (http://www.geneious.com) software was used to assemble the forward and reverse sequences of American specimens. A maximum likelihood tree was obtained using RAxML 7.0.4 (Stamatakis, Reference Stamatakis2006) after 1000 multiple inferences on the original alignments using the GTRCAT nucleotide model, starting from a random parsimonious tree, with the default initial rearrangement settings and the number of rate categories. Branch support was based on 1000 rapid bootstrap pseudoreplicates. Incurvaria masculella (Denis & Schiffermüller) (Lepidoptera, Incurvariidae), Heliozela sericiella (Haworth), Antispila treitschkiella (Fischer von Röslerstamm), Antispila oinophylla (van Nieukerken & Wagner) and Holocacista rivillei (Stainton) (Lepidoptera, Heliozelidae) were used as outgroups to root the tree. Specimens used in this study are listed in table 1 along with GenBank accession numbers (KJ426997- KJ427024); sequence data are also available in the public BOLD dataset ‘Coptodisca lucifluella in Italy’ [dx.doi.org/10.5883/DS-COPIN]. Uncorrected intra- and interspecific p-distances were calculated with Mega 4 (Tamura et al., Reference Tamura, Dudley, Nei and Kumar2007).

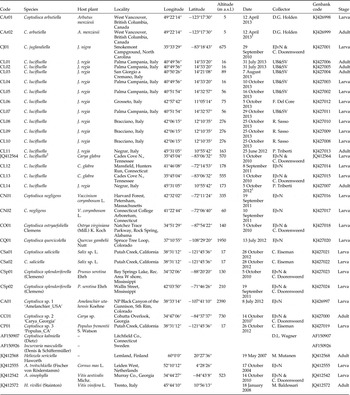

Table 1. Specimens used for molecular analyses, with host plant, collection localities and dates, geographical coordinates and Genbank accession numbers.

1 Date of collection of larva, the sequenced adult reared later from these larvae.

2 Originally published under the name Coptodisca ella.

EJvN,E.J. van Nieukerken; UB&SV, Umberto Bernardo & Salvatore Vicidomini.

Biological characterisation

The observations of life cycle, the level of damage and stage of invasion were conducted by sampling in agricultural and urban environments, in organically and chemically treated orchards (all trees of chosen fields were used to collect samples), in two Italian regions: Lazio and Campania. Further sampling was conducted in other Italian regions to evaluate the distribution of C. lucifluella. Geographical coordinates and altitude are presented in Online Resource 2. A site was suspected to be infested when mines and holes were present in the leaves of the sampled plants. The life cycle and the levels of infestation during the leafminers’ last generation were studied from September 2010 throughout October 2013. Larval instars were recorded from 15 randomly collected leaves, twice monthly between June and September 2012 in Bracciano (RM, Lazio) and San Giorgio a Cremano (NA, Campania). In 2013, samplings were performed weekly, and extended to three other orchards (sites 1, 2, 3) in Palma Campania (NA) (online Supplementary material 2).

Individual leaflets were considered as sample units; however, the percentage of infestation was also calculated for compound leaves to give an estimate of distribution of infestation on the tree. The number of mines and holes per leaflet were recorded and the percentage of infestation was calculated as [infested leaflets (or leaves) × 100/sampled leaflets (or leaves)]. Furthermore, to have an estimate of leaves with greater damage due to the construction of the pupal cases, the percentage of leaflets with holes was calculated as [number of leaflets with holes × 100/sampled leaflets]. Lastly, the percentage of larval mortality from the first instar to mature larvae was calculated as [100−(number of holes per leaflets × 100/number of mines per leaflets)]. Living and dead larvae were singly isolated to evaluate the level of parasitization (study in progress) while the remaining part of the leaves were stored in plastic bags at 25°C in a climatic chamber, to evaluate the presence of eggs by checking for new mines after 1 week. Larval mortality in the pupal cases was not included in this study.

Sampling stopped when no more living larvae could be found in the sampled trees. The last sampling event of the year was the latest in which at least one living larva was recorded.

Samples collected in San Giorgio a Cremano were used to record the mean dimension of complete mines and pupal cases. They were measured with a stereomicroscope at a magnification of 25 ×. The following measurements were recorded: maximum length and width of mines, and length and width of pupal cases. The area of the oval pupal cases was calculated with the formula [width × length × (2 × π)−1]. A total of 44 adults collected in Italy (40 in San Giorgio a Cremano and 4 in Negrar) and 17 collected in the USA (online Supplementary material 1) were used to measure forewing length.

To evaluate the distribution in the canopy, an additional sampling in the Palma Campania orchards was made on 29 October 2013. The same number of leaves (15 compound leaves) was collected at 2 and 6 m from the ground by hand from low branches and with the aid of lopping shears from the medium–high canopy.

Statistical analyses

To assess whether the differences of infestation (of leaflets), the number of mines, the number of holes and the different larval mortality recorded in different years at the same locality, were significantly diverse, data satisfying conditions of normality and homoscedasticity, untransformed or after appropriate transformation, were analysed by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Means were subsequently separated at the 0.05 level of significance by a multiple range test (Tukey HSD or, in the case of unequal samples, Bonferroni). In all the other cases, a non-parametric test (Kruskal–Wallis) was used and medians were graphically separated by a Box-and-Whisker plot analysis (Statgraphics plus, 1997). Proportions of infested leaflets and leaves with holes between different years of sampling of the same field and the percentage of larval mortality (from the first instar to mature larvae) were compared by G test (Sokal & Rohlf, Reference Sokal and Rohlf1995). All data are presented non-transformed with their standard error (±SE).

Results

Taxonomic characterization

Morphological analysis

All the examined Italian specimens and the American specimens collected on Carya species, possess a forewing pattern characteristic of C. lucifluella Clemens (and present in the Lectotype, albeit faded due to age; see online Supplementary material 3), with a fuscous dark to almost black suffusion of the dorsal or posterior half of the wing tip, including the area proximal to the first silvery patches (fig. 1a, b). This is a good diagnostic character as all the other Coptodisca feeding on Juglandaceae and most other species have this area as pale as the costal region or just a shade darker (see online Supplementary material 3). However, two species feeding on different hosts have a similar forewing pattern: C. quercicolella (Braun, Reference Braun1927; Opler, Reference Opler1971) feeding on Quercus in the Western USA and C. saliciella feeding on Salix throughout the USA (for example, http://bugguide.net/node/view/849941/bgpage). These species can be diagnosed – apart from their host plants – by small differences in the genitalia (which need to be studied in more detail) and with different DNA barcodes. The American and Italian specimens that were examined also agree in the genitalia (fig. 2), but a lack of a taxonomic revision makes these characters presently less useful for diagnostic purposes.

Fig. 1. Life stages and damage of walnut shield bearer, Coptodisca lucifluella on Juglans regia in Italy: (a) adult; (b) forewing; (c) larva in mine; (d) larva outside mine; (e) pupal cases on a leaf; (f) pupal cases under the bark; (g) damage on a leaf of Juglans regia; (h) mines with holes and pupal cases attached to the edge; (i) pupal exuvium protruding from the case upon eclosion.

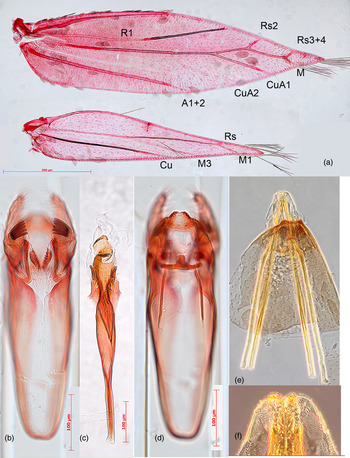

Fig. 2. Coptodisca lucifluella, morphology details: (a) wing venation with veins labelled (see text); (b) male genitalia (with phallus removed) in ventral view; (c) phallus in ventral view; (d) male genitalia in a more dorsal view; (e) terminal segments of female with oviscapt and apophyses; (f) detail of oviscapt tip with 5 teeth. a+ c slide EJvN4458, USA, Maryland; b, d slide EJvN4462, Italy, Negrar; e, f slide GV10Cl, Italy, San Giorgio a Cremano.

Molecular analysis

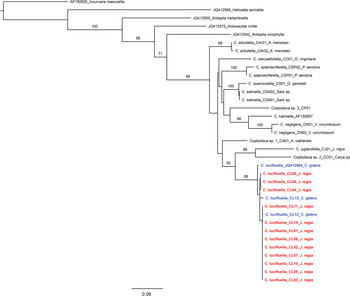

COI barcodes were obtained for all the selected specimens (28) (table 1). No stop codons or frame shifts were detected. The phylogenetic analysis, which is the first for the genus Coptodisca, showed that the genus Coptodisca is monophyletic, although the basal relationships within the genus are not resolved. Among the American specimens, there are two distinct species feeding on Carya: C. lucifluella and an unknown, probably new, species from Georgia (Coptodisca sp. 2 (Cc01)), which had a COI distance of 11% (online Supplementary material 4). The phylogenetic tree also showed that all specimens collected in Italy (12) belong to the same clade as North American C. lucifluella (three specimens) (fig. 3) and that all sequenced Coptodisca feeding on Juglandaceae (C. juglandiella, C. lucifluella and Coptodisca sp. 2 (Cc01)) are closely related. Furthermore, the Italian specimens of C. lucifluella collected in seven different orchards (five localities) carried only two haplotypes (table 1), whereas each American specimen carried a distinct haplotype (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Maximum likelihood tree for COI data. Bootstrap support >70% for taxonomically relevant splits are reported above branches. Specimens of Coptodisca lucifluella in red are from Italy, in blue are from the USA.

Species redescription

Based on the morphological and molecular evidence, we concluded that the species that has invaded Italian walnut orchards is C. lucifluella. Due to the poor original description (Clemens, Reference Clemens1860), the species is here redescribed using Italian and American material (online Supplementary material 1).

Coptodisca lucifluella (Clemens)

Aspidisca lucifluella Clemens, Reference Clemens1860: 209. Lectotype (here designated) ♀: [United States, Pennsylvania, Easton, larva September–October on hickory, imago emerged in June]. Label photographs see online Supplementary material 3.

Aspidisca ella Chambers, Reference Chambers1871: 224. Holotype [probably lost]: [United States, Kentucky, Covington, reared from case found on an Oak tree] New synonymy

Aspidisca lucifluella; Chambers (Reference Chambers1871): 224.

C. lucifluella; Felt (Reference Felt1906): 717; Forbes (Reference Forbes1923): 228; Payne et al. (Reference Payne, Tedders, Cosgrove and Foard1972): 74.

Coptodisca ella Forbes (Reference Forbes1923): 228 [probably a synonym of lucifluella]; van Nieukerken et al., Reference Nieukerken, Wagner, Baldessari, Mazzon, Angeli, Girolami and Doorenweerd2012: 51.

Coptodisca sp.: Bernardo et al., Reference Bernardo, Sasso, Gebiola and Viggiani2011: 638.

[Coptodisca juglandiella: van Nieukerken, Reference Nieukerken, Karsholt and Nieukerken2013; Ellis, Reference Ellis2014. Misidentifications]

Male (fig. 1a, more photos in online Supplementary material 3). Head face and vertex covered with appressed, strongly metallic silvery-white scales, sometimes prominently raised in dried specimens (a drying artefact). Labial palps porrect, white. Maxillar palps small, 1-segmented. Antennae silvery grey with ca. 16 segments and each flagellomere with two rings of scales. Tongue as long as head.

Thorax and basal third of the forewing is silvery white (fig. 1b), usually becoming darker towards the forewing posterior edge. Forewing is from one-third yellow in the anterior (or costal) to two-thirds dark fuscous to almost black in the posterior (dorsal); in the middle along costa there is a triangular silver streak, edged with black on both sides; a second triangular spot, frontally edged black and distally ending against the black, terminal, fan-shaped patch (forming the darkest part of the forewing); posteriorly (on the dorsal edge) there is a triangular silvery streak in the fuscous area, opposite to the first costal streak; in the apical wing part there are two small silvery spots each comprising just a few scales, one spot just frontally of the fan-shaped spot and one just posterior of it; terminally there is a distinct fringe line of grey fringe interrupted by a few black hair-scales running straight from the fan-shaped spot; anteriorly the fringe becomes more yellowish. Hindwing grey, fringe grey but more anteriorly yellowish. Underside of the forewing almost black, anterior (costal) one-third yellowish. Abdomen dark grey.

Measurements: Wingspan 4.1 ± 0.1 mm (3.4–4.7, n = 13); forewing length 1.9 ± 0.2 mm (1.6–2.3, n = 61), no difference between sexes (1.9 ± 0.06, males n = 10, 1.9 ± 0.04, females n = 11) (ANOVA test d.f. = 1, P = 0.94, F = 0.01), nor between USA (1.9 ± 0.04, n = 17) and Italian specimens (1.9 ± 0.02, n = 44) (ANOVA test d.f. = 1, P = 0.60, F = 0.28).

Venation (Fig. 2a): Almost identical to that of A. oinophylla (van Nieukerken et al., Reference Nieukerken, Wagner, Baldessari, Mazzon, Angeli, Girolami and Doorenweerd2012). Forewing with Sc barely visible. R1 a separate vein, connected by persistent trachea to Rs+M stem. Rs+M terminating in five branches, interpreted as Rs2 (possibly with 1) to costa, Rs3 + 4 to costa just before apex, one M branch to dorsum just beyond apex, possibly CuA1 (earlier interpreted as M2 + 3) to dorsum and a weakly developed CuA2. A1 + 2 a strong, separate vein. Hindwing with Sc barely or not visible, Rs+M a strong vein, bifurcate from ca. one-quarter of upper vein ending in two branches: Rs and M1, lower vein single (M3); Cu separate, A absent.

Male genitalia: The general structure of male genitalia (fig. 2b, d) was very similar to all the checked congeneric species. Vinculum elongate and almost cylindrical, combined length of vinculum and tegumen (‘capsule’) ca. 395–570 μm (n = 3). Valva length ca. 130–175 μm; pectinifer with a comb of 5–7 teeth; the few specimens examined suggest that the number of teeth in the left valva is always one higher than in the right valva (fig. 2b). Phallus long, ca. 310–520 μm with lateral rows of ca. 5 annellar spines (fig. 2c).

Female: Colour as male. Antennal segments 14. Abdomen distally pointed. Anterior and posterior apophyses reaching anterior edge of segment V. Oviscapt tip with 5 teeth (fig. 2e, f).

Larvae pale yellow (fig. 1c, d); newly formed pupae pale yellow but darker with age. Pupal case oval (fig. 1e, f, i), mean length 2.92 ± 0.044 mm (2.20–4.18), mean width 1.74 ± 0.025 (1.32–2.42). Pupal case area 8.04 ± 0.216 mm2 (4.75–14.63) (n = 60).

Comments

Probably the only surviving syntype from Clemens’ collection, labelled ‘Holotype’, was examined and selected as the Lectotype (see details and photographs in online Supplementary material 3).

Counting antennal segments of adult moths appears to be difficult in dry specimens, because each antennal segment has two annuli of scales (as in other Adeloidea), a point that was previously overlooked (Davis, Reference Davis and Kristensen1998; van Nieukerken et al., Reference Nieukerken, Wagner, Baldessari, Mazzon, Angeli, Girolami and Doorenweerd2012); in the descriptions of A. oinophylla (Lepidoptera: Heliozelidae) the numbers of antennal segments are therefore incorrect and ca. twice the real number. The finding of different numbers of teeth in the left and right valval pecten is interesting, and was also observed in several other Coptodisca.

Distribution

Coptodisca lucifluella is widespread in Eastern North America and has been recorded in NE Texas, Mississippi, Georgia, North Carolina, Maryland, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin, New York and Connecticut (this study; Clemens, Reference Clemens1860; Chambers, Reference Chambers1871, 187; Payne et al., Reference Payne, Tedders, Cosgrove and Foard1972; Heyerdahl & Dutcher, Reference Heyerdahl and Dutcher1985). It has also been recorded from pecan in New Mexico (Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2011), probably introduced along with the host tree, as this state is outside the natural range of Carya.

Coptodisca lucifluella appears to be widespread throughout Italy. Since the first record in the Campania and Lazio regions (Bernardo et al., Reference Bernardo, Sasso, Gebiola and Viggiani2012), it has been found from the Veneto (northern) to the Basilicata (southern) regions. It has been collected in all sampled localities, except for some isolated trees at high altitude (over 1200 m a.s.l.) in Montella (AV, Campania) (Bernardo et al., Reference Bernardo, Sasso, Gebiola and Viggiani2012) (see fig. 4 and online Supplementary material 2 for more details).

Fig. 4. Map showing the distribution of Coptodisca lucifluella in Italy. In red Bracciano, San Giorgio a Cremano and Palma Campania (the orchards of survey), in green the orchards where the leafminer was recorded and in blue the location where the leafminer was absent.

Hostplants

Coptodisca lucifluella was collected in Italy on J. regia and J. nigra, but in North America on various Carya species: C. glabra Miller (pignut hickory), C. illinoensis (pecan) and C. tomentosa Sarg (mockernut hickory).

Life cycle

A total of approximately 1500 walnut leaves (9000 leaflets) were collected in the three sampling years and examined for the presence, the number and the life stage of C. lucifluella. The lifecycle of C. lucifluella was observed for other Coptodisca spp. (Davis, Reference Davis and Kristensen1998) except for the following features: pupal cases were collected either from leaves, on bark or from leaf litter. However, the number of pupal cases that were attached to twigs and leaves (fig. 1e) with a silken thread decreased with the approach of winter, while the number of those between and under bark increased (fig. 1f). Developmental stages of the leafminer sampled during the years are reported in fig. 5.

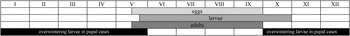

Fig. 5. Life cycle of Coptodisca lucifluella in Italy. Roman numbers denote months.

The number of annual generations differed depending on the sampling year, but at least three (2011–2012) or four (2013) generations annually were recorded. Active mines (larva present and feeding) were continuously recorded in the period between June and September to October, resulting in overlapping generations. The first newly laid eggs were collected in June (2011) but egg-laying may start as early as in 2013 when some larval holes were already sampled in the first days of June. The duration of the first generation (egg to adult) in June was 18–20 days in 2011. The last larvae ready to hibernate inside the case on leaves were collected in September or October. Mature larvae hibernated in dormancy, mediated by quiescence. Adult emergence from pupal cases collected in November was forced in December by placing the cases at room temperature.

Level of damage

The mean number of mines per leaflet at 2 m of tree height (3.4 ± 0.20) and at 2 m (2.6 ± 0.13) did not differ significantly (d.f. = 1; P = 0.126; n = 660, n = 332 at 2 m and n = 328 at 6 m; Kruskal–Wallis test), and neither did the number of holes per leaflet at 2 m (1.2 ± 0.08) and 6 m (1.1 ± 0.08) (d.f. = 1; P = 0.940; n = 660, n = 332 at 2 m and n = 328 at 6 m; Kruskal–Wallis test). All sampled compound leaves of the last generation of each year, in September–October, were infested (table 2). However, the percentage of leaflet infestation changed with the sampling years, being higher in 2011 and 2013, and lower in 2012. The mean percentage of infested leaflets ranged between 52.4 ± 5.04 and 93.7 ± 2.08% (table 2) depending on year and locality. The mean percentage of infested leaflets with holes due to the preparation of pupal cases by larvae ranged from 24.2 ± 3.31 to 68.4 ± 6.45 (table 2).

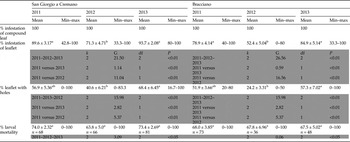

Table 2. Percentage of infestation of compound leaves and leaflets, percentage of leaflets with holes and of larval mortality in San Giorgio a Cremano and Bracciano after the last generation (September–October) over the last 3 years.

All data are presented non-transformed with their ±SE. Values with the same letter, in the same sampling locality, indicate no significant differences at the G test. A comparison between results recorded in different years of sampling, in the same locality, was performed. Fifteen compound leaves in each locality and year were sampled. n = number of replicates. Results of statistical analyses are shown on a grey background.

No significant differences were recorded in the mean percentage of larval mortality over the years in either of the sampling localities (table 2). The mean number of mines per leaflet was variable, ranging between 1.1 ± 0.19 and 5.3 ± 0.42 (table 3), while the mean number of holes per leaflet ranged from 0.4 ± 1.03 to 1.5 ± 0.17 (table 3).

Table 3. Mean number of mines and mines with holes of Coptodisca lucifluella for leaflets in San Giorgio a Cremano and Bracciano after the last generation (September–October) in the last 3 years.

All data are presented non-transformed with their ±SE and values with the same letter, in the same place of sampling, are not significantly different at the 5% ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis test. A comparison between data recorded in different years of sampling, at the same locality, was performed. Fifteen compound leaves per locality per year were sampled, but they were composed by a different number of leaflets; n = number of leaflets).

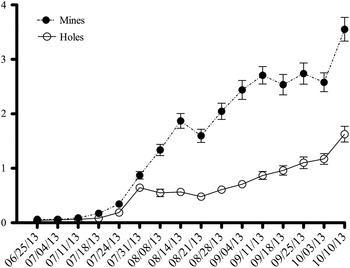

Data on the average number of mines and holes per leaflet showed the same trend in the two sampled areas; at each site differences were significant only between the data of 2012 and those of 2011 and 2013, and all numbers were lower in 2012 (ANOVA test d.f. = 2, P < 0.01, F = 27.45 for mines and Kruskal–Wallis d.f. = 2, P < 0.01 for holes at San Giorgio a Cremano; Kruskal–Wallis d.f. = 2, P < 0.01 for both mines and holes of Bracciano) (table 3). The mean length of the completed mines was 7.81 ± 0.211 mm (4.5–13.2) and the mean width was 3.48 ± 0.104 mm (1.98–5.94) (n = 60). An example of the annual trend in the mean number of mines and holes per leaflet is summarized in fig. 6 (2013, mean of the three orchards of Palma Campania, sites 1, 2, 3).

Fig. 6. Seasonal development of Coptodisca lucifluella, mean value of number of mines and holes per leaflet, in Palma Campania in 2013.

Discussion

Any new association between an indigenous plant and an exotic invasive species needs to be investigated, especially if the plant is of economic interest (Nentwig & Josefsson, Reference Nentwig and Josefsson2010). For the majority of alien species, there is often a lack of knowledge about their biology and control, with C. lucifluella being no exception. Furthermore, when an invasive pest colonizes a new host plant in a new area, its impact can be devastating, eventually leading to the extinction of the plant species (Kenis et al., Reference Kenis, Auger-Rozenberg, Roques, Timms, Péré, Cock, Settele, Augustin and Lopez-Vaamonde2009).

The first important step when a species is found for the first time in a new habitat is its correct identification. The identification of C. lucifluella was challenging due to the unsatisfactory characterization of most species of Coptodisca, which necessitates a taxonomic revision of the genus. Nonetheless, the number of candidate species that could have matched the invasive Italian samples was greatly reduced by the evidence that in Italy and the rest of Europe there is only one other leafminer that attacks J. regia, Caloptilia roscipennella (Hübner) (Tomov et al., Reference Tomov, Trencheva, Trenchev, Cota, Ramadhi, Ivanov, Naceski, Papazova-Anakleva and Kenis2009; Lopez-Vaamonde et al., Reference Lopez-Vaamonde, Agassiz, Augustin, De Prins, De Prins, Gomboc, Ivinskis, Karsholt, Koutroumpas, Koutroumpa, Laštůvka, Marabuto, Olivella, Przybylowicz, Roques, Ryrholm, Sefrova, Sima, Sims, Sinev, Skulev, Tomov, Zilli and Leeset2010). This species belongs to the family of Gracillariidae, thus is easily distinguishable from Coptodisca, for example, by the completely different shape of its mines (Patocka & Zach, Reference Patocka and Zach1995; Ellis, Reference Ellis2014).

Until the first record in Europe in 2010 (Bernardo et al., Reference Bernardo, Sasso, Gebiola and Viggiani2012), all Coptodisca species were exclusively found in the Nearctic and Neotropical regions (Davis, Reference Davis, Hodges, Dominick, Davis, Ferguson, Franclemont, Munroe and Powell1983, Reference Davis and Kristensen1998; Hespenheide, Reference Hespenheide1991). In the Nearctic region, only C. juglandiella, Stigmella juglandifoliella (Clemens) and S. longisacca Newton & Wilkinson (Nepticulidae) have been recorded to damage the genus Juglans, but the Nepticulidae produce completely differently shaped mines and the adults of these species are easily recognizable (Newton & Wilkinson, Reference Newton and Wilkinson1982). The first description of C. lucifluella was based on specimens reared from hickory in Pennsylvania by Clemens (Reference Clemens1860). A few years after the first description, the very similar C. ella was described (Chambers, Reference Chambers1871). However, soon thereafter Chambers expressed doubts on the validity of this species, due to the morphological similarity with C. lucifluella and to it likely having the same host plant (he examined the residues of the leaf forming the pupal case) (Chambers, Reference Chambers1874). Synonymy between C. ella and C. lucifluella was also suggested by Forbes (Reference Forbes1923). Coptodisca ella had unknown biology except that it had been reported from samples taken from the bark of oak trees (Chambers, Reference Chambers1871, Reference Chambers1874). No new records or information on C. lucifluella or C. ella have been published recently.

It is noteworthy that more unnamed species occur on Juglandaceae in North America, including a Californian species feeding on Juglans californica S. Wats, and one feeding on Juglans microcarpa Berlandier in the Guadalupe Mountains of Texas (D. Wagner, personal communication). Unfortunately, we were unable to get DNA sequences out of the material of these species that we examined (see online Supplementary material 1 and 3 for details and photos), but morphology shows that they are different from C. lucifluella.

Although the multiple lines of evidence here strongly suggest that the Coptodisca found in Italy is C. lucifluella, there are small inconsistencies with older literature (about American populations only) that should be evaluated, concerning: (a) the colour of larvae (previously described as light brown instead of yellow) (Payne et al., Reference Payne, Tedders, Cosgrove and Foard1972); (b) the initial shape of the mine (tortuous versus straight) (Payne et al., Reference Payne, Tedders, Cosgrove and Foard1972); (c) the shape of holes (most of the mined portion of leaflet leaf is contained in the pupal case versus only a small portion of the mine) (Payne et al., Reference Payne, Tedders, Cosgrove and Foard1972) (fig. 1g, h); and (d) the stage at which it overwinters (pupae versus mature larvae) (Heyerdahl & Dutcher, Reference Heyerdahl and Dutcher1990). Notwithstanding the possibility of erroneous observations in earlier literature, such discrepancies have three possible explanations: (1) as we have shown that there are at least two species of Coptodisca on Carya, some of the previous data could refer to a species that is as yet unnamed; (2) differences could be associated with the host plants (Carya versus Juglans), for example, colour of larvae could be affected by plant substances (Yamasaki et al., Reference Yamasaki, Shimizu and Eujisaki2009). Similarly, both the shape of mines and holes could be affected by host plant condition, because a different thickness of the leaves influences the shape of mines, with smaller mines in thicker leaves and larger mines in thinner leaves; (3) the hibernating stage may be affected by the milder climate of Italy, with higher winter temperatures and hotter summers than the climatic conditions in the USA, Georgia (the state where Payne et al., Reference Payne, Tedders, Cosgrove and Foard1972 collected data), or by the existence of intraspecific variability in the hibernating life stage. Lastly, our observation that a large number of pupal cases can be found on walnut leaves during the first two generations – a behaviour previously reported only for C. lucifluella (Payne et al., Reference Payne, Tedders, Cosgrove and Foard1972) on pecan leaves – serves as confirmation of the identification.

Molecular analysis of the Italian specimens showed a low haplotype variability (only two); this could be due to the founder effect (the reduced genetic variation that occurs when a population is established by a single or a few specimens) (Gillespie & Roderick, Reference Gillespie and Roderick2014), suggesting that C. lucifluella arrived in Italy by a single introduction event and with few individuals. This is a common pattern recorded for invasive species (e.g. Rubinoff et al., Reference Rubinoff, Holland, Shibata, Messing and Wright2010; Cifuentes et al., Reference Cifuentes, Chynoweth and Bielza2011). However, a wider knowledge of the haplotype variability in the native area of C. lucifluella and a finer scale analysis (for example, by microsatellites) are needed to obtain more information about the number of introductions.

Data collected over the last 3 years about C. lucifluella's diffusion and density in Italy show that its invasiveness, based on the terminology of Colautti & MacIsaac (Reference Colautti and MacIsaac2004) ranged between the stages IVa (widespread but rare) and V (widespread and dominant). With the exception of Campania and Lazio Regions, the density of the leafminer is still quite low, having rarely been found at a density of more than two or three holes per leaflet. This suggests that either the introduction has happened in one of those two regions (Bernardo et al., Reference Bernardo, Sasso, Gebiola and Viggiani2012) or that it is there where the leafminer finds better climatic conditions to develop. However, further investigations are needed to determine the locality and the source of the first introduction, especially considering that in recent years new plantations of pecan have been made in Italy.

Our biological data showed that C. lucifluella completes three to four generations annually in Central and Southern Italy. Our results are congruent with previous North-American observations, where at least four generations annually were hypothesized based on the increase in larval density per year on pecan trees (Heyerdahl & Dutcher, Reference Heyerdahl and Dutcher1990). Active larvae were found throughout the period June to October and new mines were observed in almost all samples, matching data previously recorded in Georgia on another host (Heyerdahl & Dutcher, Reference Heyerdahl and Dutcher1990). The large overlap between generations could lead to underestimation of the real number of generations. Our observations span 3 years, yet they are confined to Central and Southern Italy; hence, we cannot exclude the possibility that a smaller number of generations are completely in colder areas.

Our observations showed a homogeneous distribution of the population in the examined orchards (in the last sampling all of the sampled leaves were infested) and in the canopy. The damage, even with a high percentage of infestation, does not seem economically important, due to the small size of the insect and of its mines, confirming observations for several species of Heliozelidae recorded on cultivated plants in Italy over the last 20 years, which only episodically caused economic damage (Bernardo et al., Reference Bernardo, Monti, Nappo, Gebiola, Russo, Pedata and Viggiani2008; De Tomaso et al., Reference De Tomaso, Romito, Nicoli Aldini and Cravedi2008; Baldessari et al., Reference Baldessari, Angeli, Girolami, Mazzon, van Nieukerken and Duso2009; van Nieukerken et al., Reference Nieukerken, Wagner, Baldessari, Mazzon, Angeli, Girolami and Doorenweerd2012). Except for occasional outbreaks, Coptodisca species are also not considered serious pests in their native countries (Slingerland & Crosby, Reference Slingerland and Crosby1914; Brown & Eads, Reference Brown and Eads1969; Maier, Reference Maier1988; Heyerdahl & Dutcher, Reference Heyerdahl and Dutcher1990). However, the damage caused by the leafminer could be used by pathogens to introduce themselves inside the leaves. It has also been demonstrated that leaves of Vaccinium macrocarpon Aiton mined by C. negligens had an earlier abscission than unmined leaves, which lead to a reduction in the longevity of leaves (Maier, Reference Maier1989, Hespenheide, Reference Hespenheide1991). This kind of damage, in the long run, could weaken a tree and therefore the real extent of the C. lucifluella damage on its host needs to be assessed over a longer time span.

Coptodisca lucifluella was described by Clemens in 1860 and hitherto collected only on hickory leaves (Carya sect. Carya: Carya spp.) and pecan (Carya sect. Apocarya: Carya illinoensis (Wang)) (Clemens, Reference Clemens1860; Chambers, Reference Chambers1871; Payne et al., Reference Payne, Tedders, Cosgrove and Foard1972). The association between C. lucifluella and J. regia and J. nigra is here reported for the first time. Recently, two other Nearctic insects feeding on Juglans invaded Italy: the walnut husk fly Rhagoletis completa Cresson (Diptera: Tephritidae) (Duso, Reference Duso1991; Ciampolini & Trematerra, Reference Ciampolini and Trematerra1992; Eppo/Cabi, Reference Smith, McNamara, Scott and Holderness1997; Benchi et al., Reference Benchi, Conelli and Bernardo2010) and Pityophthorus juglandis Blackman (Coleoptera: Scolytidaee) (Montecchio & Faccoli, Reference Montecchio and Faccoli2014). In the case of C. lucifluella, we do not know if the actual host range in the native area also includes Juglans or whether the host shift occurred in Italy after its invasion. However, it is interesting to note that all Coptodisca feeding on Juglandaceae are phylogenetically close (fig. 2), following the general principle that related insects feed on related plants (Menken et al., Reference Menken, Boomsma and Nieukerken2010).

The level of potential damage by C. lucifluella is greatly reduced by the high mortality of younger larval instars. This level of mortality is partly due to parasitization by indigenous parasitoids that are adapting to the new host (Bernardo et al., in preparation). A conspicuous complex of parasitoids of C. lucifluella has also been recorded in the Nearctic region (Yoshimoto, Reference Yoshimoto1973; Heyerdahl & Dutcher, Reference Heyerdahl and Dutcher1985; Gates et al., Reference Gates, Heraty, Schauff, Schauff, Wagner, Whitfield and Wahlet2002). In the native area the parasitism rate of C. lucifluella has been reported to reach a maximum of 61% at the leafminer's peak density and to be host-density dependent. Both larvae and cocoons (with larvae and pupae) were parasitized but the highest percentage of parasitization was recorded for cocoons (Heyerdahl & Dutcher, Reference Heyerdahl and Dutcher1985).

Concluding remarks

Due to its widespread distribution, we assume that C. lucifluella arrived in Italy several years ago. Its actual distribution is likely to be wider than recorded here, as it was collected in nearly every surveyed location. Considering its widespread presence and rapid reproduction, C. lucifluella might quickly increase its abundance and distribution in Italy and other European countries. Nevertheless, as also observed for other Heliozelidae and excluding the outbreaks, the level of damage does not seem to be worrisome. The possibility remains, however, that damage by C. lucifluella, if continued for a number of years, might lead to a progressive reduction in carbohydrate reserves and a gradual decline in tree health and performance. Based on the high mortality recorded and on the large number of parasitoids being collected, it would be preferable to encourage biological control rather than performing chemical treatments.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0007485314000947

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Craig Phillips and five anonymous reviewers whose comments helped improving the manuscript and Bodil Cass for kindly editing the language. Besides, the authors wish to thank Salvatore Vicidomini, Lucio Bernardo, Renato Feola, Riccardo Jesu, Fabrizio Del Core, Pasquale Cascone, Paolo Triberti and Francesca Lecce for the samplings throughout Italy. Camiel Doorenweerd and Ruben Vijverberg are acknowledged for molecular work in Leiden. The authors thank David L. Wagner (Storrs, CG, USA), Donald R. Davis (Washington DC, USA), Peter T. Oboyski (Berkeley, CA, USA), Jason Weintraub (Philadelphia, USA), Charley Eiseman (Massachusetts, USA) and Dave Holden (Vancouver, BC, Canada) for the loan or gift of North American specimens. This research activity was supported by MIUR with the project titled: Insects and globalization: sustainable control of exotic species in agro-forestry ecosystems (GEISCA) PRIN, id: 2010CXXHJE and partly, in the first years of activity, from funds of Campania Region URCOFI (Unità Regionale Coordinamento Fitosanitario).