Since Thucydides' account of the Peloponnesian War, the rise of new powers and the resulting shifts in the international distribution of power have been associated with major turbulence in world politics. The current rise of non-Western powers such as Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa represents such a shift and is widely considered to be one of the most significant changes in international politics in the past few decades.Footnote 1 While a growing body of literature has advanced our knowledge about the rising powers, we still lack a clear understanding of how the current power shift affects the international system. Do rising powers oppose established powers, creating potentially dangerous tension in international politics, as some scholars and observers predict? Are we witnessing the ‘remaking of world order’ (Acharya Reference Acharya2018; Huntington Reference Huntington1996; Kupchan Reference Kupchan2012), or are rising powers integrating into the Western-centered international order, leading to harmony and cooperation between ‘new’ and ‘old’ powers, if not to the ‘ultimate ascendance of the liberal order’ (Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2011, 57; also, Kahler Reference Kahler2013), as others claim?

This article challenges two prominent arguments: (1) the more optimistic view that the rising powers are socialized and integrated into the existing Western-centered order and (2) the claim that these powers are a set of highly diverse actors with diverging (if not competing) interests and strategies (Hart and Jones Reference Hart and Jones2010; Laïdi Reference Laïdi2012). Instead, we argue that the rising powers have begun to form a bloc of dissatisfied states opposing the dominant Western powers and the status quo they maintain. We contend that this dissatisfaction arises from three sources: (1) influence on the international stage, (2) status in the international hierarchy and (3) the norms and principles that sustain the current international order. Dissatisfaction with the international status quo is not new; what has changed since the turn of the century is that the rising powers have begun to form a bloc of jointly dissatisfied states. The formation of this bloc, we argue, has resulted from endogenous and exogenous dynamics. Internally, the rising powers have experienced a contemporaneous increase in power over the years driven mainly by unusually high economic growth rates – consistently higher than those in developed countries – enabling them to press for a more influential role in international politics. Externally, the limits of both Western self-restraint and capacity demonstrated by the war on terror after 9/11, the war in Iraq without a UN mandate, regime change in Libya and the instability of the ‘liberal’ order exemplified by the 2008 financial crisis have encouraged the formation of this bloc. Jointly, these dynamics have fostered the institutionalization of the rising powers as IBSA and BRICS.

To evaluate this argument, we provide a systematic comparative analysis of rising and established powers across issue areas and over time. In doing so, we go beyond the extant scholarship on the rising powers that has favored anecdotal evidence including selected foreign policy episodes or statements of state leaders, or which has remained confined to analyzing individual rising powers or selected rising power–established power dyads (namely, the US and China). A smaller number of studies have examined the rising powers as a group, though these tend to focus on their inward dynamics, to the exclusion of their interaction with the established powers. Finally, many analyses remain confined to specific issue areas such as international climate negotiations or the international economy.

To address these limitations, we analyze the voting behavior of the rising powers within the context of a global multi-issue international organization (IO), the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). Assessing voting in the UNGA is particularly well suited to addressing whether rising powers form a bloc to position themselves against established powers because it provides us with consistent data on the positions of a large number of countries (potentially all United Nations member states), both over time and across a broad range of issues in world politics. Our approach builds on work pioneered by Poole and Rosenthal (Reference Poole and Rosenthal1991) to study voting in the US Congress, which others have extended to analyze voting behavior in international legislative bodies, such as the European Parliament (Hix Reference Hix2001), the UN Human Rights Council (Hug and Lukács Reference Hug and Lukács2014) and the UNGA (Bailey, Strezhnev, and Voeten Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017; Voeten Reference Voeten2000; Voeten Reference Voeten2004). Particularly relevant to the present study is Voeten's (Reference Voeten2000) analysis of voting in the UNGA, which identifies the formation of a post-Cold War conflict line between Western and non-Western states. Voeten (Reference Voeten2004) also finds support for the claim that the United States has become an increasingly ‘lonely superpower’ in world politics.

Two recent studies focus on rising powers using voting in the UNGA. Ferdinand (Reference Ferdinand2014) seeks to identify the possible convergence in the foreign policies of BRICS states by comparing their voting behavior in the UNGA over six time periods between 1974 and 2011, and finds increasing voting cohesion among them. Hooijmaaijers and Keukeleire (Reference Hooijmaaijers and Keukeleire2016) examine whether the intensified interaction among the rising powers in the BRICS framework generated stronger voting cohesion among them in the UNGA over the period 2006–2014. Unlike Ferdinand, they conclude that it is ‘not possible to speak about a cohesive BRICS bloc in the General Assembly’ (Hooijmaaijers and Keukeleire Reference Hooijmaaijers and Keukeleire2016, 397).

These analyses remain largely restricted to voting cohesion among the rising powers; their findings are inconclusive. We go beyond these studies in two important ways. First, we analyze the voting behavior of rising powers both as a group and vis-à-vis the established powers. Secondly, we use methods that are better suited to shed light on voting behavior. Rather than relying on cohesion measures that are prone to bias – since they are unable to discriminate between changes in preferences and changes in the Assembly's agenda (Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017, 433) – we use roll-call votes in the UNGA to construct probabilistic models of states' ideal points based on spatial models of voting, and assess how distant these are from one another. Specifically, we apply a combination of W-NOMINATE (Poole Reference Poole2005) and a dynamic ordinal spatial model based on Item Response Theory (Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017) to analyze more than 1,000 roll-call votes in the UNGA from 1992 to 2011, focusing on two different groups of rising powers (BRICS and IBSA). We compare their voting behavior to the coalition of major status quo powers representing the main supporters of the ‘liberal’ world order – the G7, which has historically demonstrated a high degree of voting cohesion in the UNGA (Volgy, Derrick and Ingersoll Reference Volgy, Derrick and Ingersoll2003).

We find dramatic convergence in the voting behavior of the rising powers, largely in parallel to the institutionalization of BRICS and IBSA summits. Concurrently, our analysis reveals that the rising powers vote in ways that are fundamentally different from the established powers. In fact, the voting behavior of ‘new’ and ‘old’ powers differs across a large set of issues in international politics, ranging from human rights to disarmament, fault lines that have remained strikingly stable since the end of the Cold War. At a more general level, this suggests that international politics is characterized by a commonality of dissatisfactionFootnote 2 on the part of the rising powers and interest incompatibility between old and new powers rather than by the harmonious integration of the rising powers into the existing Western-centered international order.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. In the next section, we develop our theoretical argument in four parts: sources of rising power dissatisfaction, internal economic growth, external dynamics and the resulting institutionalization of the rising powers as a bloc of dissatisfied states (IBSA, BRICS). We then introduce the models of probabilistic voting and the UNGA voting data we use to test it. The penultimate section presents and interprets the results of the analysis. We conclude by briefly identifying avenues for further research.

Dissatisfaction and the Formation of a Counterhegemonic Bloc

We propose that the rising powers – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – are dissatisfied with the international status quo and have begun to form a bloc of states against the Western powers that maintain it. This argument builds on insights from power transition theory (PTT) that expects shifts in the international distribution of power to lead to turbulence and conflict in world politics (Kugler and Organski Reference Kugler, Organski and Midlarsky1989; Organski Reference Organski1968; Tammen et al. Reference Tammen2000). The main claim underlying this expectation is that powers experiencing a rapid relative increase in their economic, demographic and military power are positioned to challenge the existing order that has been created by the dominant powers at the top of the international hierarchy to serve their interests. Conflict is likely to arise in such situations because the rising powers seek to change (or overthrow) the established order, while the dominant powers seek to resist substantial changes to that order, and to defend their privileged position within it. To some observers, conflict is almost inevitable during such power shifts (Gilpin Reference Gilpin1983). For proponents of PTT, by contrast, conflict does not follow automatically. It only occurs if the rising challenger is dissatisfied with the international status quo, that is, it is ‘dissatisfied with the established international leadership, its rules and norms, and wishes to change them’ (Tammen et al. Reference Tammen2000, 9). While the scholarship on rising powers typically focuses on rising challenger/declining hegemon relationships (such as the United States and China currently), PTT reminds us that dissatisfied rising powers can form partnerships to challenge the dominant power (Tammen et al. Reference Tammen2000, 11). At the same time, the rising powers do not necessarily confront a single hegemon but a group of established powers that together defend the international status quo (Wohlforth Reference Wohlforth1999, 30). In proposing that Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa have begun to form such a bloc of dissatisfied states (such as IBSA and BRICS) that oppose the ‘liberal’ international order and its main defenders, the United States and its Western allies (the G7), we argue that this dissatisfaction stems from three (interrelated) sources: dissatisfaction with (1) their influence in the current order, (2) their status in that order and (3) the norms, rules and institutions underpinning it.

Influence

Influence refers to an actor's capacity to achieve desired outcomes by modifying a target's behavior. While the means of achieving influence may be coercive, it may also be persuasive in nature (Knorr Reference Knorr1973). The rising powers all have substantial economic, military and political resources (Hurrell Reference Hurrell2006). However, they have not been able to fully transform these resources into political influence to secure material benefits and shape the international ‘rules of the game’. Many Western-centered institutions maintain formal and informal rules that provide their most powerful (Western) members with disproportionate benefits and reflect those powers' normative understandings of the international order (Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2001). Rising powers have forcefully advocated, but with limited success, reforms that would increase their influence in international institutions, including efforts to achieve UN Security Council (UNSC) reform, gain access to leadership positions in the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the Inter-American Development Bank, and shape international negotiations on security, trade and climate change (Hopewell Reference Hopewell2016; Narlikar Reference Narlikar2011; Soares and Hirst Reference Soares de Lima and Hirst2006). Seeking greater influence in Western-dominated Bretton Woods institutions, rising powers have demanded increases in their relative voting shares to counter a de facto G7 veto. They have also criticized the informal procedure of appointing the head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, in which the World Bank presidency is held by an American and the Fund's managing director is a European.Footnote 3 But even when both institutions adapted to increase voting shares for the rising powers in 2010, the voting-power-to-GDP ratio remained heavily skewed toward Western countries (Vestergaard and Wade Reference Vestergaard and Wade2015, 4–5). With the exception of Russia, the rising powers have also been excluded from the G7/8 club of advanced industrial economies that was complemented, though not replaced, by the G20 group of developed and developing countries only in the context of the 2008 financial crisis.Footnote 4

Status

The rising powers also seek positive recognition or status (Deng Reference Deng2008, 21).Footnote 5 Like influence, status has material implications (for instance, higher status can increase a state's power and wealth through enhanced economic and diplomatic exchange), but it can also activate positive emotions like pride and respect. Domestically, leaders can generate legitimacy by credibly demonstrating a commitment to elevate the state's status (Ward Reference Ward2017, 37). The rising powers believe they are entitled to a more important role in the Western-dominated international system (Hurrell Reference Hurrell2006, 1–5); they are all dominant actors in their respective regions and ‘have taken on a self-appointed role as leaders’ (Stephen Reference Stephen2012, 293) in various non-Western alliances, including the G77 at the UN and the G20 at the WTO. Their expectations have not yet been met by established powers, leading to status inconsistency or status dissatisfaction. Status elevation has been a key part of China's foreign policy since the mid-1990s (Deng Reference Deng2008, 8–9), not least to generate domestic legitimacy for the Communist Party's leadership. India, too, has sought to elevate its international standing by mounting its own challenges to the existing order – most prominently by acquiring nuclear capability in violation of the non-proliferation regime (Nayar and Paul Reference Nayar and Paul2003, 11, 14–15). Similarly, Brazil and South Africa have demanded permanent seats on the UN Security Council (Schoeman Reference Schoeman2015, 436; Soares and Hirst Reference Soares de Lima and Hirst2006, 29). Unlike other rising powers, Russia is a resurgent power, often directing foreign policy pursuits with the goal of reestablishing its great power status and reasserting influence over the former Soviet states (MacFarlane Reference MacFarlane2006, 5). The G7/8 ‘outreach’ (or Heiligendamm) process that began in the mid-2000s demonstrated a lack of recognition by the established powers, when Brazil, China, India (and Mexico) were invited to join the G7/8 summits but were not included in decision making. Excluded from the main discussions, South African President Mbeki complained that the rising powers had ‘only been asked to join in the dessert and miss the main meal’ (cited in Schoeman Reference Schoeman2015, 435).

Normative Dissatisfaction

The rising powers are not just unhappy about their lack of influence and status in the international order; they are also dissatisfied with the (Western) norms, rules and institutions that underpin the existing order. Normative dissatisfaction results in efforts to change the normative foundation of the prevailing order (Ward Reference Ward2017, 11). The post-Cold War era has been characterized by a dramatic strengthening of Western norms that are at odds with those held by the rising powers: economic deregulation as reflected in the Washington Consensus vs. interventionist state capitalism (Stephen Reference Stephen2014) and the promotion and protection of human rights and humanitarian intervention (the ‘responsibility to protect’) vs. the primacy of state sovereignty (Hurrell Reference Hurrell2006). With respect to international institutions, the rising powers have traditionally preferred unanimity decisions over majority decisions, and sovereignty-affirming international institutions over those with high levels of authority (Blake and Lockwood Payton Reference Blake and Lockwood Payton2015).

Dissatisfaction with their influence, status and prevailing international norms among rising powers is hardly new. What is novel and begs explanation is why these powers have begun to form a bloc of jointly dissatisfied states against the established Western powers. We argue that endogenous changes within the rising power group and a combination of exogenous dynamics led to the institutionalization of the rising powers as IBSA and BRICS around the turn of the century.

Endogenous Change

For a counterhegemonic bloc to form, not only must its members be dissatisfied with the international status quo, they must also rise in power, mainly through economic growth (Gilpin Reference Gilpin1983; Tammen et al. Reference Tammen2000, 17). This applies to the rising powers that have experienced extraordinary economic growth rates since the early 2000s, empowering them to seek more diplomatic clout. Indeed, despite the economic woes of the new Russian Federation, BRICS as a group boasted higher economic growth rates than the G7 in the first decade after the fall of the Soviet Union (IMF 2019). The pace only quickened in the following decade: BRICS economies averaged just over 6 per cent growth, compared to the G7's 1.4 per cent (IMF 2019). Two widely noted reports published by Goldman Sachs in the early 2000s predicted that BRICS would have a much greater role in the world economy within the next decade (O'Neill Reference O'Neill2001, 6–8),Footnote 6 and overtake the United States, Japan, UK, Germany, France and Italy in less than forty years (Wilson and Purushothaman Reference Wilson and Purushothaman2003, 3–5). This shift represents a marked change in the international distribution of power and has been widely noted by scholars and observers. At the end of the 1990s Wohlforth argued that international politics was unambiguously and durably unipolar (1999, 7–8), with the United States (and its Western allies) firmly at the top of the international hierarchy. Just ten years later, observers noted that ‘the “unipolar moment” is over’ (Layne Reference Layne2012, 203); that the United States is ‘no longer a hyperpower towering over potential contenders;’ and that the ‘rest of the world is catching up’ (Schweller and Pu Reference Schweller and Pu2011, 41–42). Their rise in power has enabled the BRICS countries to press for more influential roles in world politics. For example, India, Brazil and South Africa strongly restated their traditional demands on international trade, the reform of international institutions and economic development (Vieira and Alden Reference Vieira and Alden2011, 511). Brazil and India led the Group of 20 within the WTO developing countries, and resisted attempts by the United States and the EU to consolidate their agricultural subsidy policies. China and Russia have prevented a meaningful UN response to the civil war in Syria,Footnote 7 and, seeking to act as a global norm entrepreneur, Brazil has proposed ‘a responsibility while protecting’ aimed at limiting the use of force included in the Responsibility to Protect doctrine's third pillar.

International Dynamics

In addition to changes occurring within the rising powers, exogenous factors have helped to coalesce an otherwise heterogeneous group of states as the rise in power of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa has coincided with a decline in the legitimacy and effectiveness of the Western-centered order. The aggressive unilateral security policies the United States adopted in its ‘war on terror’ after 9/11, the US-led 2003 invasion of Iraq (without a UN mandate) and regime change by Western powers in Libya in the name of the responsibility to protect have damaged the legitimacy of the Western-centered order, and have exposed the limits of Western (and in particular US) strategic self-restraint (Mastanduno Reference Mastanduno2019; Pape Reference Pape2005, 35; Schweller and Pu Reference Schweller and Pu2011; Walt Reference Walt2006). In international trade, the dominant Western powers were unwilling at WTO Doha Round to open their markets to agricultural trade from the global South (Vieira and Alden Reference Vieira and Alden2011), and the 2007/8 financial crisis has called the instability of the ‘liberal’ economic and financial order to the attention of the rising powers, as well as the fiscal constraints facing the dominant Western economies (Armijio and Roberts Reference Armijo, Roberts and Looney2014, 503).

Institutionalization

We argue that both dynamics – endogenous change as well as external pressures and opportunities – have fostered the institutionalization of the rising powers as IBSA and BRIC(S) groups. Both groupings have multiple aims. They serve to increase intra-IBSA and BRICS co-operation, to harmonize their views across a set of international issues and to co-ordinate their foreign policies (Armijio and Roberts Reference Armijo, Roberts and Looney2014; Stuenkel Reference Stuenkel2015; Vieira and Alden Reference Vieira and Alden2011). The IBSA dialogue forum, established by India, Brazil and South Africa in 2003, had its first High Level meeting at the fringes of the G8 summit in Evian to serve as a tool of foreign policy co-ordination in the areas of international trade and security among the three countries (Vieira and Alden Reference Vieira and Alden2011). Like IBSA, BRICS is an informal institutional platform for co-operation and policy co-ordination. Initiated by Russia alongside the 2005 UNGA meeting, the BRICs members have been convening since 2006 (informally) and formally as BRICS since 2009.Footnote 8 In addition to their respective annual summits, IBSA and BRICS have significantly intensified their technical co-operation by developing a structure that mirrors the G7 from finance and trade to public health, agriculture, science and research, the judiciary and defense (Stuenkel Reference Stuenkel2015, chapter 5). But the BRICS countries also aim to challenge Western dominance in world politics and to increase their global influence by working together to harmonize their negotiation positions on a range of issues (Armijio and Roberts Reference Armijo, Roberts and Looney2014, for IBSA see Alden and Viera 2011). According to one Brazilian representative, the BRICS serves its members as ‘a forum for convergence’ (Stuenkel Reference Stuenkel2015, 89). Importantly, the BRICS have established parallel institutions such as the New Development Bank and the Contingency Reserve Agreement as an alternative to the IMF and the World Bank in which the dominant Western powers exercise disproportionate influence.

IBSA and BRICS members possess substantial economic, military and political resources, yet differences persist. They have managed to leverage their diversity in advantageous ways. While China stands out as the most powerful among them, the other members help Beijing multilateralize its foreign policy strategies, while bringing important resources to the table. Like China, Russia and India are nuclear powers. Moreover, Brazil and India can mobilize coalitions of developing states from the global South (Hopewell Reference Hopewell2016). Russia, a resurgent power, offers unique know-how in dealing with the hegemon, while South Africa, a regional leader in Africa, adds legitimacy and representativeness to the club (Schoeman Reference Schoeman2015, 434, 440–441).Footnote 9

If our argument is correct and rising powers have begun to form a bloc of dissatisfied states, holding similar views about a range of international issues, we should observe an expression of their joint dissatisfaction with the international status quo by voting in increasingly similar ways in the UNGA and by consistently voting against the United States and its Western allies as the main defenders of that status quo.Footnote 10

Competing Views: the Logic of Integration

Our argument challenges competing views on rising power behavior in important ways. First, it counters accounts that depict the rising powers as a set of highly diverse actors with diverging (if not competing) interests and strategies. It has often been argued that the rising powers’ ability to oppose the Western powers is limited due to intra-BRICS rivalry. As Hart and Jones (Reference Hart and Jones2010, 85) note, ‘tensions within this group still outweigh tensions between any one member and the United States’, while Laïdi (Reference Laïdi2012, 615) describes the BRICS as a ‘heterogeneous group of often competing countries’ whose only commonality lies in a strong preference for state sovereignty and independence of national action.

Our argument also challenges accounts that emphasize processes of accommodation and socialization, which claim that – rather than confronting the dominant powers – the rising powers integrate themselves harmoniously into the existing international order. Ikenberry, in particular, has extended the logic of the liberal world order to the non-Western powers. In his view, the existing Western-centered order is expected to accommodate new powers rather than to give way to a more contested and fragmented system (Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2011, also Kahler Reference Kahler2013). There are two mechanisms that explain integration. First, the existing order is harder to overturn: great power war is no longer a means of changing the international system, which makes change necessarily less radical and more incremental. Secondly, integration into the existing order is in the rising powers' own interest, as they benefit from its rules, practices and institutions (Ikenberry and Wright Reference Ikenberry and Wright2008, 11). As a result, Ikenberry argues that today's power shift is not the end of the ‘liberal’ order, but instead represents its ‘ultimate ascendance’ (Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2011, 57).

Others make similar claims of a rather smooth integration by emerging powers, emphasizing processes of socialization. To the extent that rising powers participate in Western-shaped international institutions, socializing effects are expected to emerge through regular and sustained interaction in these institutions, altering the identities and ultimately the interests of their member states (Johnston Reference Johnston2008; Kent Reference Kent2002).

Both claims have observable implications for voting in the UNGA. If relations among the rising powers are characterized by political incoherence, tension and disagreement, this should find its expression in divergent voting behavior of IBSA and BRICS members in the UNGA. Likewise, voting in the UNGA should reflect the hypothesized processes of socialization.Footnote 11 If an integrative logic of liberal world order is at work in international politics and the rising powers are being socialized into that order, we should observe interest convergence between rising powers (BRICS, IBSA) and the Western status quo powers (G7): they should vote in (increasingly) similar ways in the UNGA. These predictions contrast with our argument, according to which we should observe that the rising powers vote in similar ways among themselves, and that they consistently vote against the established powers.

Analyzing Voting in the UN General Assembly

To empirically evaluate these propositions, we use UNGA roll calls to construct probabilistic models of voting that rely on the assumptions of spatial models of politics, based on Black's (Reference Black1958) median voter theorem. We use W-NOMINATE to estimate the ideal points of UN member states. This allows us to assess the ideological distance among the rising powers (BRICS and IBSA states) and between the rising and established powers (the G7 states) in a multi-dimensional policy space (Poole et al. Reference Poole2011; Reed et al. Reference Reed2008; Voeten Reference Voeten2000). W-NOMINATE facilitates the study of voting behavior because it allows us to identify the most salient cleavages upon which states vote – dimensionality of conflict – in international politics, and provides information about the content of votes in the UNGA (human rights, disarmament, economic development, etc.). However, it is less suited to accommodate changes in voting behavior over time (that is, it is not dynamic). To address this potential problem, we complement the W-NOMINATE analysis with a (one-dimensional) dynamic model of voting based on item response theory (IRT) (Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017).

We believe voting in the UNGA is appropriate to test our argument about rising power behavior in IOs. The UNGA is the ‘only forum in which a large number of states meet and vote on a regular basis on issues concerning the international community’ (Voeten Reference Voeten2000, 186). This approach provides us with consistent data on the voting behavior of potentially all UN member states, across a large number of issues in international politics, and over a long period of time.

We acknowledge that the analysis of voting in the UNGA entails at least two important limitations. First, voting in the UNGA is largely symbolic; unlike resolutions in the Security Council, those adopted by the UNGA are non-binding. However, noncompulsory decisions and the lack of direct policy output gives states more freedom to maximize their interests than in other international arenas (Voeten Reference Voeten2000). Moreover, even though UNGA resolutions are not legally binding, they may nevertheless be consequential. As Abbott and Snidal (Reference Abbott and Snidal1998, 24) indicate, inclusive institutions such as the UNGA ‘can have substantial impact on international politics by expressing shared values on issues like human rights [et cetera] in ways that legitimate or delegitimize state conduct’. Similarly, debates and voting within the UNGA are reflected in states' foreign policy behaviors such as loan disbursements by international financial institutions (Voeten Reference Voeten2012, 3) and sanctions placed on Russia as a result of its annexation of Crimea.Footnote 12

Secondly, some have suggested that voting in the UNGA is affected by vote buying – states trade votes in the UNGA for various forms of US aid (Dreher, Nunnenkamp and Thiele Reference Dreher, Nunnenkamp and Thiele2008) or IMF loans (Dreher and Sturm Reference Dreher and Sturm2012) – which biases how states vote.Footnote 13 Others, however, have found that the extent of vote buying in the UNGA remains limited in scope (Carter and Stone Reference Carter and Stone2015) and argue that the evidence concerning the conditions under which vote buying occurs is mixed (Mattes, Leeds and Carroll Reference Mattes, Leeds and Carroll2015, 283). And, while vote buying may affect the voting behavior of weaker recipient states, this is less likely to be the case for more powerful states such as the BRICS. If votes of the rising powers were ‘bought’, effectively pulling these states closer to the Western position, this would strengthen rather than undermine our argument, as we expect the rising powers to form a counterhegemonic bloc of states and to vote against the established Western powers. Thus if vote buying is occurring and we observe contestation, this means that in the unlikely case that rising powers submit to pressure to vote with the G7, they are resisting despite the carrots and sticks on offer.

To analyze the voting behavior of the rising powers in the UNGA, we use the ‘United Nations General Assembly Voting data’ compiled by Strezhnev and Voeten (Reference Strezhnev and Voeten2012). The data contains all roll-call votes – that is, all contested votes on resolutions in the UNGA. Resolutions that are not put to a vote because they were adopted ‘by consensus’, ‘by acclamation’ or similar measures are not included in the data set. These constitute the majority of the resolutions adopted in UNGA, around 64 per cent between 1974 and 2004 (Peterson Reference Peterson2006). We exclude resolutions without a vote for two reasons. First, they do not allow us to estimate the ideal points of rising and established powers. Secondly, the vast majority of resolutions that are adopted without a vote are inconsequential in that they do not require UN members to take specific actions. In addition, a large proportion of resolutions call on the UN itself to act (to organize meetings or to coordinate with other intergovernmental organizations, for instance). As a result, the obligation to act often lies not with UN member states, but with the UN Secretariat and other UN bureaucracies. Only once this burden shifts to UN members themselves do we observe increased roll-call voting. Specifically, roll-call voting is almost always the modus operandi when states – or groups within states – are at the center of resolutions. This distinction is consistent with general knowledge about the political nature of the UN: once particular member states are implicated (or blamed), consensus falls by the wayside.

UNGA resolutions are adopted by a ‘one-state, one-vote’ majority principle. The data report whether a state voted for or against the resolution, abstained from the vote, or was absent. Absenteeism is usually regarded as missing data. Abstentions, however, have been treated as missing values (Reed et al. Reference Reed2008), or as intermediate actions between ‘yea’ and ‘nay’ (Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017). Here, we handle abstentions in two ways. First, we consider abstentions as another – softer – way of voting ‘no’ and merge ‘abstentions’ and ‘no’ votes into the same category (Voeten Reference Voeten2000; Voeten Reference Voeten2004). This is because, in the UNGA, states use both types of votes to express disagreement with a resolution. As Voeten explains, ‘[S]ince UNGA resolutions are not binding, what really matters is whether or not a state is willing to go on the record for supporting a resolution’ (Voeten Reference Voeten2000, 193). Secondly, we analyze a model in which abstentions are considered a mid-point.

We analyze two 10-year time periods, 1992–2001 and 2002–2011, spanning the immediate post-Cold War period through the post-9/11 period. The first period can be considered ‘Western dominance’ in world politics, following the dissolution of the Soviet bloc/Warsaw Pact. Additionally, this period includes South Africa's reinstatement of voting rights following the end of apartheid.Footnote 14 The second period was selected because it coincides with the rise in power of non-Western economies and their institutionalization as IBSA and BRICS.

Finally, we introduce the G7 as the benchmark against which the formation of a rising power bloc and their confrontation of the dominant powers can be assessed. The G7 comprises the world's major status quo powers, including the United States, which makes it an appropriate touchstone. The G7 was formed in the mid-1970s by the most powerful liberal economies to address systemic disturbances and has since displayed consistently high levels of voting cohesion in the UNGA (Volgy, Derrick and Ingersoll Reference Volgy, Derrick and Ingersoll2003, 105).Footnote 15 The group has met as the G8 since Russia's inclusion in 2002; however, they continue to meet more frequently sans Russia. Originally created as an informal institution to co-ordinate the world economy, the G7's tasks have expanded to a range of non-economic issues, including security and the environment. Overall, the G7 lends itself well as a comparison group because neither the G7 nor the IBSA and BRICS groups are caucusing groups whose voting behavior in the UNGA reflects prior formal compromise. Additionally, the IBSA and BRICS as well as the G7 are informal institutions or ‘clubs’ and maintain a similar membership size.

Probabilistic Methods of Voting: Two Approaches

In the following section, we discuss two different, yet complementary, approaches used to test our argument of counterbalancing by the rising powers against established powers and whether they register dissatisfaction with the status quo by contesting the established Western-centered order – W-NOMINATE and IRT. First, we use the W-NOMINATE estimation technique developed by Poole et al. (Reference Poole2011) to analyze all roll-call votes taken in the UNGA during the two study periods. Using the assumptions of spatial voting models (Black Reference Black1958; Downs Reference Downs1957), the method estimates voters' ideal points – in this case, UN member states. States are assumed to maintain single-peaked preferences over an ideal choice in policy space, meaning that possible options further from that choice are considered less desirable. In a one-dimensional model, each vote is represented by two points that correspond to the passage or failure of a resolution. States will either prefer the rejection or passage of a resolution based on which is the closest to their ideal point in Euclidean space. One advantage of W-NOMINATE is its ability to account for voter complexity, as preferences do not always accord with a single issue or dimension. In multiple dimensions, the vote is a vector (with a given length and direction), and a state will have an ideal point associated with each dimension. Each roll-call vote is represented by a cutting line (or plane), which divides the yea from the nay votes. A voter's proximity to a cutting line indicates the model's degree of confidence in predicting whether a state will vote to accept or reject a resolution: points that fall closer to the line reflect less certainty (Poole and Rosenthal Reference Poole and Rosenthal1991, 232). W-NOMINATE estimates the policy dimensions, the Euclidean distance from the location of the vote to the voter's ideal point, and the weight of the dimensions. When applied to domestic legislatures, the dimensions tend to reflect left–right or government–opposition divisions; however, domestic ideological cleavages rarely translate to the international arena. Whereas domestic legislatures or the EU Parliament (Hix Reference Hix2001) lend themselves to a certain degree of predictability, the absence of established political parties in international politics leads to greater uncertainty over the nature of these dimensions in the UNGA. Despite these challenges, a number of techniques can help identify dimensions at the international level.

W-NOMINATE is ideal for arenas in which groups are divided along more than one dimension, but it is not as adept at addressing the comparability of behavior over time. We therefore complement the analysis above with the method developed by Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten (Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017). This technique is based on IRT but shares many assumptions with W-NOMINATE.Footnote 16 To allow for comparisons over time, the dynamic ordinal spatial model uses ‘bridge observations’ – resolutions in the UNGA that are identical over time – to identify whether changes in voting behavior are driven by a change in state preferences (Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017, 435). By identifying these bridging votes, which isolate the cut points, shifting preferences may be ascertained from shifting parameters. However, this model is confined a single dimension and it treats abstentions as a midpoint between yes and no. We estimate the original IRT model as well as a modified version that categorizes nays and abstentions together to align it with the inputs of W-NOMINATE, allowing us to compare the findings from the W-NOMINATE analysis with the original and to our modified IRT models.

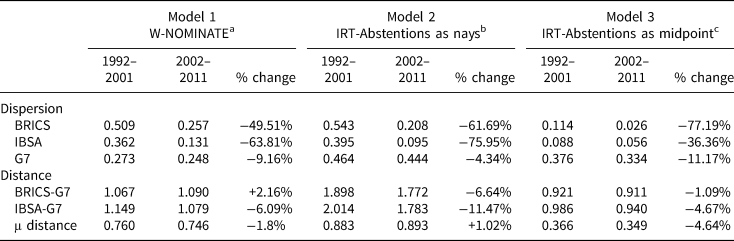

The analysis of ideal points allows us to assess two characteristics. The first is how cohesively rising powers – both BRICS and IBSA – and established powers act in the UNGA across the two time periods. The measure of cohesion is the average Euclidean distance between the members of each group to their respective centroid.Footnote 17 Secondly, the magnitude between the ideal points of the rising powers and the G7 serves as an indicator of convergence/divergence among the groups of states. To measure the magnitude between the two groups, we calculate the Euclidean distances between their centroids. The positions of these states in relation to the cutting lines indicate the degree of disagreement between the groups of states. Cohesion and distance scores are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Measures of dispersion and distance in UNGA voting models

Notes: Dispersion is the average of the absolute values of the distance from the centroid. ‘μ distance’ is the average distance between any two ideal points in the UNGA.

a Ideal point values between [−1, 1].

b Ideal point values between [−1.47, 1.67].

c Ideal point values between [−1.90, 3.01].

Results

Dimensionality of Conflict

The cohesion and distance of the BRICS and G7 groups are directly affected by the existence of multiple dimensions of voting. Thus we briefly identify and discuss the salient dimensions before turning to the main results of the models. The Appendix contains further discussion of dimensionality.

Figures 1a and 1b present the ideal point estimates for the first and second periods of study, respectively. Cutting lines represent four broad issue areas of UNGA voting: economic development, human rights, nuclear proliferation and Israel/Palestine. The angles and positions of the cutting lines indicate the nature of the dimensions. Those with angles between 70 and 110 degrees fall within the first dimension, while angles of 0–30 degrees or 150–180 degrees fall within the second dimension. Lines that fall in the intermediate ranges occur in both dimensions (Voeten Reference Voeten2000).

Figure 1. Spatial maps with ideal points and group centroids. (a) 1992–2001; (b) 2002–2011

The median cutting lines of each issue area indicate a ‘West vs. Rest’ division, echoing Voeten's (Reference Voeten2000) findings. Issues of economic development, human rights and nuclear proliferation – with respective angles of 96, 101 and 82 degrees in the final period – present a clear divide between Western countries and most of the rest of the world. The angle for the Palestinian question, particularly from 2002–2011, falls well outside the exclusive first dimension (135 degrees) and even divides the United States and Canada from the rest of the G7. Figure 1, which includes the proximity of US and Israeli ideal points in both periods (virtually stacked on top of each other), suggests a second dimension that is based on a pro/anti-Israel policy position. Having addressed the probable nature of two dimensions along which UNGA voting is structured, the next section examines the results of the two probabilistic methods of voting to determine whether the rising powers act as a bloc in the UNGA and the extent to which they vote with or against the status quo powers.

Rising Power Bloc Formation

Table 1 reports the findings of the three models – (1) W-NOMINATE, (2) IRT where abstentions are a mid-point between yea and nay and (3) IRT in which abstentions are treated as nays. These findings lend strong support to our argument that the rising powers have begun to form a bloc of dissatisfied powers in the UNGA. As visual inspection of Figure 1 and the dispersion scores reported in Table 1 suggest, the rising powers have coalesced over the two periods. Models 1 and 2 indicate that the IBSA and BRICS countries maintained larger dispersion scores than the G7 group in the first post-Cold War decade (with the exception of IRT Model 3). BRICS members were highly dispersed: China and India were far removed from the group centroid, and Russia was positioned closer to the G7 camp than to the other emerging powers. Three cutting lines in Figure 1a – nuclear proliferation, the Palestinian question and human rights – divide China, India, Brazil and South Africa from Russia (and the G7 members), indicating substantial disagreement among the rising powers over these issues. Russia's closer position to the Western camp in the UNGA captures the democratization period of Russian politics, when the country adopted a more open stance towards the West, joining the G8 as well as the Council of Europe. While the cutting lines and distance from the G7 reveal that the rising powers were generally dissatisfied with the status quo powers, there is little to suggest that they were acting in concert to oppose the G7 position.

Unlike the rising powers, the G7 group displays lower dispersion scores during the period 1992–2001 in Models 1 and 2, indicating that the status quo powers formed a cohesive group in the UNGA. As Figure 1 demonstrates, the G7 members also found themselves on the same side of all four cutting lines, indicating a high level of agreement across these issue areas. As the positions of the cutting lines illustrate, the G7 countries were frequently in the minority. This is consistent with the view that the UNGA is a forum in which developing countries frequently outvote the Western powers.

In the second, post-Cold War, decade (2002–2011), the picture changes quite dramatically, as we observe significant convergence in the voting behavior among the rising powers. This convergence coincides with their institutionalization as BRICS and IBSA in the past decade. In fact, as their lower dispersion score reveals, the BRICS vote nearly as (Model 1) or more (Models 2 and 3) cohesively than the G7 bloc during this period (Table 1). This finding is consistent with the argument that there was a jointly dissatisfied bloc of rising powers.

Even more striking is the percentage change in the dispersion score among the BRICS, IBSA and G7 groups. Dispersion among the BRICS countries has contracted considerably, from 49 per cent in Model 1 to 77 per cent in Model 3. The G7 has also experienced a relative decline in dispersion over the two study periods, but the change is much less dramatic, ranging from 4 per cent to 11 per cent. The changes in IBSA across the two periods have tracked more closely with those of the BRICS. Thus the degree of change among the BRICS and IBSA groups is far more substantial than that of the G7.

At the same time, there is some variation within the camps of emerging powers. While Russia has moved away from the West and closer to the rest of the rising powers, it remains on the opposite side of the nuclear proliferation and human rights median cutting lines from the remaining rising powers (Figure 1b). This offers some support for the argument that Russia, while it clearly has moved closer to the rising power bloc, is a special case within this group (Hart and Jones Reference Hart and Jones2010, 67; MacFarlane Reference MacFarlane2006). Finally, in the second period, IBSA dispersion scores are lower than those of the G7 and BRICS in Models 1 and 2. This would be consistent with arguments that the IBSA states – democratic countries from the global South – maintain common positions in global affairs and may even share a sense of collective identity (Antkiewicz and Cooper Reference Antkiewicz, Cooper, Shaw, Grant and Cornelissen2011, 303).Footnote 18 It is also consistent with the findings of Mielniczuk's (Reference Mielniczuk2013) study, according to which the rising powers have formed a discursive bloc in the UNGA to employ common public rhetoric that centers on notions of multipolarity, non-intervention, poverty alleviation and the restructuring of international institutions (1,087).

We find that G7 states continue to display a high level of voting cohesion, indicated by their low dispersion scores in the second period. As the cutting lines in Figure 1b demonstrate, the United States and Canada (and a few small island states) vote with Israel, while the other members of the G7 vote with the large majority of the UN member states. Moreover, we observe a widening gap between the United States and the other G7 members, a result that we can observe both visually and in terms of the ideal points across all models. This offers support for the argument that the United States, while clearly in the Western ‘camp’ in the UNGA, has become a rather ‘lonely’ superpower (Voeten Reference Voeten2004).

Overall, both methods – W-NOMINATE and IRT – indicate voting convergence among the rising powers, which lends strong support to our argument that, despite their differences, the rising powers have begun to form a bloc in the second period under investigation that was characterized by accelerated economic growth within the rising power camp, a change in the international dynamics (decline of Western self-restraint and effectiveness), and the institutionalization of the rising powers as IBSA and BRICS.

Distances Between the Two Blocs

Having established the degree of in-group cohesion, we turn to how the rising powers position themselves vis-à-vis the established powers. Do they vote against the dominant Western powers, as our argument suggests, or do we instead observe convergence in the voting behavior of rising and established powers, suggesting that processes of socialization and integration are at work? To answer this question, we examine the Euclidean distances between the centroids of the BRICS and IBSA states and the G7.

The position of the groups in relation to the cutting lines in Figure 1b and the distance scores reported in Table 1 support the proposition that the rising powers – with the partial exception of Russia – are dissatisfied, and disagree with the established powers over key issues in international politics. Not only do both BRICS and IBSA members frequently vote against the G7 countries; the distances between the two camps are also large – well above the average distance between any two members of the UNGA for that period (as shown in the final row of Table 1, ‘μ distance’). Across all models, the distance between the BRICS and the G7 is around 50 per cent greater than the average distance, and in some cases it is nearly 2.5 times larger (Models 2 and 3).Footnote 19 The difference between the groups is even more striking in both of the IRT Models (2 and 3), where the distances between the G7 and BRICS fall within the 95th percentile. The extent of disagreement between rising and established powers becomes even clearer when we compare the scores in Table 1 to other meaningful distances between two ideal points. Using distance scores from Model 1, we know, for instance, that the United States and Israel are close allies and have very similar foreign policy preferences, which is reflected in an average distance between their ideal points of 0.02. Likewise, the distance between the two EU members, Germany and France, is 0.19. By contrast, the distance between the United States and North Korea is 1.99, meaning that the two countries are almost always opposed in the UNGA.

While our results show that the distance between both groups is large, and that new and old powers disagree substantially over important issues in international politics, we also find that the distances between the BRICS and IBSA states and the G7 have remained fairly stable over time. There has not been a marked shift in the sense of a convergence in their voting behavior; nor do our results suggest that the two groups have drifted further apart. This is in spite of the increasing participation of the rising powers in international organizations. From 1992–2011 shared memberships in intergovernmental organizations for the BRICS countries increased by 11.4 per cent.Footnote 20 However, increased shared memberships with established powers has not led to socialization or interest convergence on the part of the rising powers. What our data does reveal is a relatively persistent chasm between these two groups of states despite more opportunities for socialization. While this division is not new, what has changed is that the rising powers have become much more powerful, to the point that they are considered ‘systemically important’ in that major international problems such as financial crises can no longer be addressed without them (Payne Reference Payne2014, 1).

The large Euclidean distance between the two camps, their location on different sides of the various cutting lines, and the significant convergence in the voting of the rising powers during the past decade together offer strong support to our argument that the rising powers form partnerships in which the dissatisfied states align in opposition to the status quo coalition.

These findings – rising power cohesion has increased significantly and the distance between them and the G7 is large and relatively stable over time – contradict the widely held view that the rising powers form a heterogeneous group of competing countries, and challenge theories of accommodation and socialization, which would predict interest convergence over time (Bearce and Bondanella Reference Bearce and Bondanella2007). Our results clearly show that there is no evidence of an alignment of interests between new and old powers. Contrary to Ikenberry's claim, we observe the persistence of a ‘contested and fragmented system of blocs’ rather than an ‘ultimate ascendance’ of a liberal global order, at least when we consider the voting behavior of rising and established powers in the UNGA (Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2011, 56–57).

Conclusion

Few observers dispute that the current power shift is real. What is much more contentious is whether the rising powers are dissatisfied with the international status quo and whether they act as a bloc. To help answer this key question in world politics, this article proposes an argument for assessing the degree of dissatisfaction among rising powers and whether that dissatisfaction is reflected in the formation of a counterhegemonic bloc within the context of the UNGA.

We contribute to this research program by advancing an argument of rising power dissatisfaction that highlights three important motivations – the quest for influence, status and their objection to prevailing norms that have come to dominate multilateral institutions like the United Nations. These motivations combine with endogenous factors, changing international dynamics, and their institutionalization on the basis of their shared dissatisfaction.

Methodologically, we contribute to the systematic analysis of rising power behavior by testing these propositions using spatial modeling techniques, analyzing rising power behavior in the UNGA across a range of issue areas and over time. We find notable convergence among rising powers, demonstrated by substantial tightening of the policy space among them. Thus the rising powers are now considered to be system relevant and their voting behavior suggests a commonality of dissatisfaction with the international status quo. Moreover, the results reveal persistent disagreement between old and new powers and are at odds with arguments that predict their harmonious integration into the ‘liberal’ world order. Rather, their behavior within international fora such as the UNSC, where they worked together to block a meaningful response to the war in Syria, or their individual foreign policies outside IOs, such as Russia's annexation of Crimea or China's ‘One-Belt-One-Road’ project, suggest that the rising powers have become more assertive.

We have focused on one particular forum, the UNGA, in which rising powers share membership with established powers; however, shared IOs are clearly not the only arenas in which rising powers can challenge the international status quo. Our argument of contestation as a group of dissatisfied states also applies to new organizations that exclude established powers, such as the New Development Bank and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, as well as continued co-ordination through informal institutions like the G20. Future research should analyze rising power behavior in these institutions in comparable ways to understand the scope and depth of the dynamics of bloc formation and contestation as well as their implications for institutional reform (Zangl et al. Reference Zangl2016).

Another avenue for future research is to investigate the extent to which the rising powers engage in active co-ordination to counter the established powers. In the context of UNGA voting, our data cannot directly address this question, however, as states typically negotiate behind closed doors. Observers have noted that the BRICS ‘are holding regular meetings of their permanent representatives of the UN in New York and Geneva to coordinate policies’ (Armijio and Roberts Reference Armijo, Roberts and Looney2014, 505), but they also point out that a difficulty of research on BRICS foreign policy interaction is that BRICS members make little or no information available about the actual outcomes of these various interactions (Hooijmaaijers and Keukeleire Reference Hooijmaaijers and Keukeleire2016, 393).

However, scholars and practitioners suggest that the BRICS and IBSA states co-ordinate in other institutions and fora. In the context of the WTO, Hopewell finds that ‘Brazil, India and China exhibited a remarkable degree of collaboration. Aligning themselves with one another to counter the traditional powers, the emerging powers were highly successful in accommodating their differences, coordinating their positions wherever possible, and managing inevitable tensions within their relationship’ (Reference Hopewell2017, 1,369). With regard to the BRICS, Desai (Reference Desai2013) concludes that ‘[n]ot since the days of the Non-Aligned Movement and its demand for a New International Economic Order in the 1970s has the world seen such a co-ordinated challenge to western supremacy in the world economy from developing countries’, while a senior Obama administration official stated that it was ‘remarkable how closely coordinated [Brazil, South Africa, India, China] have become in international fora, taking turns to impede US/EU initiatives’ (cited in Wade Reference Wade2011, 347). Whether rising powers co-ordinate their foreign policies at the UN deserves more scholarly attention.

For all the discussion of new versus enduring global orders, there is little consensus among scholars and practitioners of international relations regarding what to call the current global moment and its corresponding power distribution. While the present era of international politics is still searching for a name, there is little doubt that some countries that have remained outside the main power dynamic are searching for a way into the club of ‘rule makers’.

Supplementary material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000538.

Acknowledgements

For helpful comments we thank the editor and three anonymous reviewers. We also thank Michael Bailey, Stephanie Hofmann, Anja Jetschke, Andrea Liese, Tom Long, Mareike Kleine, Eric Payton, Keith Poole, Sven Regel, Matthew Stephen and Bernhard Zangl.

Data availability statement

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/6TNALY