In trying to win elections, political parties and politicians work hard to get their messages across to the public:Footnote 1 they appeal to voters by shifting positions, sticking to ideological principles, claiming credit for policy outcomes, emphasizing advantageous issues and drawing attention away from unpopular positions.Footnote 2 Getting public attention for political messages is particularly important in the context of increasing electoral volatility and issue-based voter decision making.Footnote 3

If parties and politicians want the public to take note of their messages, media coverage is essential. The traditional news media are still the most important source of information for many voters,Footnote 4 even if parties and politicians can to some extent use advertising, canvassing or social media to contact voters directly. Political actors will thus try hard to place their messages in the media.Footnote 5 Many agenda-setting studies show that in election campaigns, political actors successfully set the broader issue agenda, and that the media respond to the issues set by parties and politicians rather than vice versa.Footnote 6 These studies tend to focus on the macro level of campaign agendas, that is, whether (and how) the issue agenda of the mass media is affected by parties’ issue agenda in terms of the salience of policy areas such as the economy and immigration.Footnote 7

However, we know far less about whether political actors are successful at getting their specific policy messages out, and thus at promoting their statements and positions. For example, a party might not just want to raise the salience of immigration per se; it might also want people to know what exactly it is proposing to do. Getting such direct coverage of particular messages is a more challenging task for parties than broader agenda setting. Media attention is a scarce resourceFootnote 8 over which parties compete with each other as well as with other actors and events.Footnote 9 Moreover, whether political actors’ specific messages are reported on ultimately depends on the decisions of journalists and editors who decide what is politically relevant and has a high news value.Footnote 10

This article reports the results of the first observational study in a multiparty context that examines when such specific party campaign messages make the news.Footnote 11 Our core argument is that message content matters: political actors should be able to increase their chances of getting the media’s attention by focusing on topics that are important to voters, other parties or the media. Importantly, this applies not just to powerful politicians but also to ordinary political actors, such as those in opposition or those without high public or party office. While powerful political actors (for example, cabinet ministers) can more easily attract media attention,Footnote 12 message content should matter for all types of actors. Ordinary political actors may thus be able to choose topics strategically in order to increase their chances of media coverage.

Understanding the attributes of successful messages sheds light on the success of electoral strategies, and has broader implications for electoral fairness and political representation. While existing research suggests that political actors set the broader issue agenda,Footnote 13 our results show that we need a more nuanced explanation of the success of specific individual campaign messages. Political actors are more likely to be able to present their own position on an issue (for example, to be quoted in a media report) if they address subjects that are already prominent in the news and important to other parties in the system. Thus the power of the media might be greater than suggested in aggregate analyses of the party and media agenda.Footnote 14

By understanding which specific messages reach the news, we also gain important insights into how the media shapes the incentives underlying issue competition between political parties. For example, parties often pursue issue engagement with their rivals;Footnote 15 the attractiveness of this strategy is evident if the media reports more on messages that address issues that other parties are also discussing. Moreover, content-based incentives may be particularly important for new or less prominent politicians and parties. Such actors will want to send out messages on issues that are most likely to get coverage. However, if issues that are already part of the media or party debate are more likely to make the news, then this limits their ability to address innovative, system-destabilizing issues. In sum, the need for media coverage indicates the opportunities and limits of issue strategies, particularly if pursued by new parties and issue entrepreneurs.Footnote 16 Overall, this study adds to a growing literature on the media success of individual messages such as parliamentary questionsFootnote 17 and party press releases.Footnote 18

Our empirical analysis uses original party, voter and media data on the 2013 Austrian general election. We study campaign messages in party press releases and their appearance in media reports in all relevant newspapers in the final six weeks of the election campaign. Following Grimmer,Footnote 19 we use cheating detection software and manual checks to compare 1,613 relevant press releases with 6,512 media reports published the following day. We supplement these data with other content analyses and survey data on parties, voters and the media. While our empirical analysis is restricted to a single country, this case is particularly well suited to answering our research question. In Austria, the range of daily newspaper editions is still important, which makes them attractive and relevant targets of political communication in press releases. This allows us to establish a closer causal link between campaign messages at day t and media content at day t + 1. Moreover, based on a common coding scheme in the content analysis of party, media and voter data in the Austrian National Election Study (AUTNES), we can match party data with the media coverage of all major national newspapers and of the public issue agenda.

Our findings suggest that about 16 per cent of all party press releases receive media attention, a figure that is remarkably high given the large number and low cost of press releases sent out during a campaign. We also find that the media are more likely to cover a press release if the issue is salient in the media’s issue agenda and if several parties address the issue. This indicates that systemic media and party system agendas affect which issues make the news,Footnote 20 while individual parties’ issue strategies have limited autonomous impact. Existing parties’ dismissive strategiesFootnote 21 may therefore often work, and parties face constraints in their ability to shape the media agenda. Moreover, addressing issues that are important to the media and other parties helps rank-and-file politicians and opposition parties, which lack the newsworthiness of their competitors in government.Footnote 22 In contrast, we find no evidence that the media’s selection of messages is driven by a party’s issue profile or voters’ issue concerns.

This article is structured as follows. First, we discuss how parties communicate their messages to the media and how successful they are in shaping media coverage. Then, we turn to the role of press releases as communication channels for campaign messages before we consider relevant message attributes that may explain variation in their success in getting the media’s attention. Next, we present our data and methods before discussing the results. We consider the broader implications of our findings in the conclusion.

EXISTING RESEARCH ON MEDIA ATTENTION TO PARTY COMMUNICATION

When are parties and politicians successful at getting their messages into the media? Two strands of research, agenda setting and media visibility, provide partial answers to this question. Agenda-setting researchFootnote 23 examines whether the issues addressed by parties and candidates (for example, in speeches, press releases or campaign ads) are also reflected in the media issue agenda, so whether party coverage of issues affects how much these issues are covered and whether they are linked to them.Footnote 24 This research can tell us whether the media agenda on average matches the party agenda, and on which issue areas congruence is higher or lower.

However, there are two important limitations when applying the findings of agenda-setting research to explain the success of party campaign messages in making the news. First, existing studies generally examine the issue agenda using rather broad issue areas such as immigration or the economy rather than more specific issues. Hence, agenda-setting studies do not tell us which individual campaign messages are more likely to get the media’s attention. Secondly, correspondence between party and media agendas does not tell us whether the issues addressed in the media are also explicitly linked to a party and its politicians.Footnote 25 It is particularly difficult to exclude the possibility that the media agenda influences party communication, or that external events and developments affect both parties and the media.Footnote 26 Yet even though there is strong evidence that parties shape the media agenda, we do not know whether this congruence is the result of direct coverage of specific party messages; nor do we know which of the parties’ many campaign messages are covered.

While agenda-setting research focuses on agenda similarity, media visibility research analyses whether the media covers political actors (that is, parties and politicians).Footnote 27 Some studies also analyse whether a political actor’s role is active or passive; that is, whether actors ‘appear as speakers in the news and are given the opportunity to explain their policy positions, to address their preferred issues, or to justify their beliefs and problem solutions’.Footnote 28 Explanatory factors in this context are attributes related to the party or candidate rather than to the content of the message. For example, politicians with leading positions in public or party office are generally more likely to be covered by the media.Footnote 29

However, we have to be cautious when using these findings to explain the success of party campaign messages. While being present in the media is necessary if a politician wants to get his or her message across, it is not in itself a sufficient factor. While visibility research helps us understand which actors are most likely to appear in the media, it is unclear whether politicians can leverage that visibility to increase coverage of their campaign messages.

In sum, research on agenda setting and media visibility tells us which issues or politicians are, on average, more present in the media and whether the media follows parties in the issues they cover. In contrast, our aim is to study the success rate of individual party messages in garnering media coverage. We do so by comparing press releases with media reports the following day.

PRESS RELEASES AS MEDIUMS FOR CAMPAIGN MESSAGES

Press releases are one of a variety of tools political actors can use to reach the media, and are a particularly useful means of capturing what parties want the media to talk about.Footnote 30 They have been used to study patterns of party communication,Footnote 31 party issue emphasisFootnote 32 and framing strategies.Footnote 33 Press releases provide us with a readily available tool for measuring party communication systematically on a day-to-day basis. They allow parties to address their core campaign issues (for example, those emphasized in their manifesto) and to respond to the dynamics of the campaign (for example, the media issue agenda).Footnote 34

Press releases are attractive to politicians: if press releases make it into the news, this is particularly useful to politicians as citizens may be more inclined to believe newspaper stories than political advertisements.Footnote 35 Moreover, press releases are quick to write and cheap to distribute, but can potentially have a large audience if covered by even one large media outlet. They are also attractive to newspapers: given tighter reporting budgets in the digital age, newspaper editors and journalists may gladly use the information – quotes and arguments – contained in press releases.Footnote 36 Indeed, US congressional press releases are sometimes run almost verbatim in local newspapers.Footnote 37

We argue that press releases are successful if the author’s statements made in the press release are used in at least one media report that features the author in an active role. Specifically, we consider a press release to be successful if it results in at least one newspaper article that (1) names the press release’s author (that is, name or party label) as an active speaker in the article and (2) deals with the same specific topic as the press release.

We know little so far about the success rates of press releases in European democracies or indeed in any parliamentary, multiparty context. GrimmerFootnote 38 analyses press releases from ten US senators and six local newspapers and shows that up to one-third of these senators’ press releases appear as sources in local newspapers, particularly in those with scarce resources. Flowers et al.Footnote 39 study the success of 277 press releases sent out by five Republican presidential candidates in 1996; they find significant differences between the national and the local media in whether they cover candidates’ press releases and whether they privilege substantive (that is, issue-related) or informational party messages. However, extrapolating from US-based findings to parliamentary, multiparty systems is not warranted since the latter differ in many respects from the US presidential system. These differences affect how electoral politics works across contexts, for example in terms of negative campaigning,Footnote 40 issue emphasisFootnote 41 and issue engagement.Footnote 42

In non-US research, BrandenburgFootnote 43 and Hopmann et al.Footnote 44 consider the extent to which the media follows parties in a multiparty, parliamentary context. Yet they examine whether the media’s overall issue agenda is shaped by the issue agenda among parties, and not whether specific messages are successful at garnering coverage. Recently, Helfer and Van AelstFootnote 45 have provided important insights by conducting survey experiments in which they ask journalists in Switzerland and the Netherlands to indicate whether they would consider writing a news item based on a fictional party press release. They show that press releases from more powerful parties are more successful at getting the media’s attention, as are messages that are unexpected and contain important policy announcements. However, they do not address the question of whether (and when) real-world parties and politicians are successful at ‘making the news’. In sum, our research builds on and extends the findings in Flowers et al.,Footnote 46 Hopmann et al.,Footnote 47 and Helfer and Van AelstFootnote 48 by considering how the media’s selection of party messages is influenced by a broad set of contextual factors in election campaigns based on unique data from media reports, party messages and voter surveys.

WHY ARE SOME PARTY PRESS RELEASES MORE SUCCESSFUL THAN OTHERS?

In order to make it into the media, campaign messages need to appeal to those who select stories and write articles: journalists and editors. To attract the media’s attention, parties have to enter into a ‘negotiation of newsworthiness’Footnote 49 by internalizing news factors and professionalizing their party organizations and communication behaviour.Footnote 50 The key question to ask is what message attributes have a high news value and are therefore particularly likely to appeal to the media.

A first factor is prior media attention. We expect that the media will be more likely to use a press release as a source if it addresses a topic that is already salient in the news. Continuity is a news value in itself:Footnote 51 the media should be interested in adding to a story that has already been reported on and is familiar to the public.Footnote 52 Moreover, media outlets adopt each other’s stories and issues.Footnote 53 This inter-media agenda setting means that press releases that deal with issues high on the media’s issue agenda are particularly interesting sources. Note that we can even conceive of an important feedback loop in this regard, with parties and politicians talking about issues that are salient in the media because they know these topics are more likely to be picked up.Footnote 54 Our first hypothesis is therefore:

Hypothesis 1 (Media issue importance): Press releases are more successful if they focus on issues that are already salient in the media.

Secondly, the media may be more likely to use press releases on topics that are important to voters. Agenda-setting research analyses the relationship between the media’s and the voters’ issue agenda.Footnote 55 While it is often argued that the media sets the agenda of the campaign,Footnote 56 recent research shows that the causal arrows between different arenas may run in both directions.Footnote 57 For example, while the media may affect the issues that are important to voters, it will be more likely to report on issues that are of interest to their readers. Indeed, increasing competition between news outlets has led to a shift from a supply to a demand market of news production,Footnote 58 encouraging the media to respond to public concerns.Footnote 59 Therefore, issues that are highly salient among the electorate should be more likely to make the news:

Hypothesis 2 (Voter issue importance): Press releases are more successful if they focus on issues that are important to voters.

Thirdly, the media may value novelty and surprise in press releases.Footnote 60 Hence, media outlets may be more likely to use a press release if that issue is new or less prominent for the party.Footnote 61 However, parties typically focus on their key campaign issues, and the media may pay scant attention to such repeated or reiterated messages, which will become increasingly familiar and dull as the campaign progresses. However, some parties develop ownership of certain issues,Footnote 62 on which they may be seen as having greater expertise. Readers may expect these parties to be mentioned if these topics come up in a report, while journalists will turn to them for information. Nevertheless, we expect parties’ messages to be more successful if they address issues that are new or unexpected and hitherto less discussed:

Hypothesis 3 (Party issue importance): Press releases are less successful if they focus on issues that are important for that party.

Finally, the media may be more likely to use a press release as a source if it addresses an issue that is important to several political parties. Although parties prefer to focus on their ‘best’ issues,Footnote 63 they also have incentives to address issues that are important to votersFootnote 64 and to respond to issues raised by their competitors.Footnote 65 If several parties engage in a discussion of the same topic, this may naturally increase the news value of an issue. Moreover, one key news value is conflict,Footnote 66 and this frame is easier to create if there is debate between political parties. A further factor may be that the media strive for balance during campaigns,Footnote 67 and this is easier to achieve on topics that are widely discussed. Indeed, Hopmann et al.Footnote 68 find a positive spillover effect: even parties that do not issue a press release on a topic are likely to be linked to it if another party sends out a relevant press release.Footnote 69 In sum, we expect issue engagement to have a positive effect:

Hypothesis 4 (Party system issue importance): Press releases are more successful if they cover issues addressed by rival parties.

DATA AND METHODS

The empirical analysis is based on content analyses of party press releases and newspaper articles published in the 2013 Austrian national election campaign. Focusing on one country (and a single campaign) allows us to study the success of campaign messages based on the full universe of party messages and media coverage. This research strategy is crucial for our analysis, as any restriction in the number of media outlets would underestimate the success of individual press releases.

Austria is a parliamentary, multiparty system that is particularly well suited for our study. It is also a country where (print editions of) newspapers are still highly relevant: about 73 per cent of the population (above 14 years of age) reads newspapers on a daily basis.Footnote 70 This allows us to focus on paper editions of newspapers, and thus to establish a closer causal link between campaign messages at day t and media content at day t + 1 (see below). At the same time, making it into one of these media reports is highly relevant because many citizens consume these media on a regular basis. Finally, data from the AUTNES allow us to match these party data with the media coverage of all major national newspapers and with the public issue agenda.

We focus on press releases distributed by parties represented in parliament (SPÖ, ÖVP, FPÖ, Greens, BZÖ and Team Stronach).Footnote 71 The Austrian party system shares many characteristics with those of other European countries. It is characterized by moderate pluralismFootnote 72 with a centre-left (SPÖ) and a centre-right (ÖVP) party. The Greens on the left and the Freedom Party (FPÖ) on the right were the main opposition parties in parliament. The BZÖ, a splinter party founded in 2005, lost most of its popularity between the general election in 2008 and the 2013 election campaign. Some Members of Parliament (MPs) left that party and joined the movement of billionaire Frank Stronach (Team Stronach).Footnote 73

Press releases are distributed by the Austrian Press Agency. We use press releases sent by parties including regional branches, parliamentary party groups and ancillary organizations during the last six weeks of the election campaign. These press releases are sent by parliamentary candidates, members of government at the federal and regional levels, MPs, party officers at the national level, as well as collective actors such as party sub-organizations for women, youth and the elderly.

One concern with this sample may be that we also include messages reflecting government business. However, members of government usually have official communication channels to distribute press releases related to their official role and duties. Government members using the party’s communication channels do so in their role as party members (see also the example in Appendix B). Another concern may be that not everyone affiliated with a party was actually part of the national campaign. To address this potential concern, we re-ran our models using a restricted sample of party actors, excluding all actors apart from government members, MPs, party leaders and party chairpersons. The results of this analysis are very similar to those presented below (see Appendix C).

The content analysis is based on 1,922 party press releases.Footnote 74 We drop press releases informing journalists about party campaign events (for example, press conferences, photo ops) and those merely containing pictures and hyperlinks to audio content (N=104). Moreover, we discard releases that are not policy related and, for example, merely contain information on specific campaign events (TV debates, canvassing), opinion polls or changes in party office (N=288). To measure the success of press releases, we identify the politician or party who issued the release. Some press releases are sent by two politicians, and these press releases enter the analysis separately for each politician. This leaves us with a total of 1,613 campaign messages.

We aim to measure whether a press release is successful in the sense that at least one media report uses it as a source. For this purpose, we group press releases by day, creating 41 clusters (one for each day). Next, we identify all media reports published in daily newspapers the day after the press release was issued.Footnote 75 The focus on paper rather than online editions makes it easier to assess a temporal relationship between the press release and the media report the following day. To avoid bias in the selection of newspapers, our sample captures all nationally relevant quality, tabloid and mid-market newspapers. Furthermore, we include media reports from all newspaper sections rather than from a particular a sub-section (for example, front pages). This information is based on the AUTNES media content analysis of eight newspapers (Der Standard, Die Presse, Salzburger Nachrichten, Kronen Zeitung, Österreich, Heute, Kurier, Kleine Zeitung). We use headlines, media reports and background analyses but exclude other types of media reports such as commentaries, interviews, cartoons and letters to the editor (N=6,512).

Each press release needs to be checked against an average of roughly 170 media reports published the following day, meaning that there are about 270,000 press release–media report dyads. To handle these data, we follow GrimmerFootnote 76 and employ a two-stage coding process. First, cheating detection softwareFootnote 77 is used to identify media reports with content that overlaps with that of a press release published the day before. The goal of this automated analysis is to narrow the number of coding units for the following hand-coding process. Yet to avoid false negatives (that is, successful press releases not detected by the software), we choose non-restrictive settings to generate more ‘hits’.Footnote 78 The cheating detection software identifies 1,882 potential ‘matches’, thus allowing us to discard 99.5 per cent of all press release–media report dyads.

Next, we go through these matches manually, reading the press release and the media report, to assess whether a press release was successful (1) or not (0). Based on the definition stated above, a coder deemed a press release as successful if the media report (1) names the press release’s author (that is, name or party label) as an active speaker in the article and (2) deals with the same topic as the press release. Examples of ‘successful’ press releases are shown in Appendix B.

Manually coding the success of press releases is not without its challenges. It is often a relatively easy task when journalists refer to their sources in the text (‘[…] announced in a press release that […]’) or if the press release is a direct source for citations. Similarly, it is relatively easy to identify press releases that did not get the media’s attention if the topic in the release differs from that in the newspaper article. Yet sometimes the coding decision is difficult, especially if the press release and the newspaper article deal with the same policy issue, but no direct evidence for a party’s influence can be found.

We deal with these problems in two ways. First, we assess the reliability of the manual coding process by having a sample of 500 coding decisions made by two coders instead of just one. The inter-coder reliability using Krippendorff’s alpha is reasonably high at 0.82. Secondly, we checked coder decisions carefully and found that disagreement often occurred when press releases and media reports refer to a third event (for example, a press conference). Hence, it is unclear whether the press conference or the press release was used as a source in the media report. This is why we add a control variable in the analysis that indicates whether a press release refers to statements made at a press conference (1) or not (0).

In line with our definition of successful press releases, it is sufficient for there to be at least one matching newspaper article that uses a party press release as a source. Thus for each press release we test whether there is at least one newspaper article for which the press release was used as source (1) or not (0).Footnote 79

Independent Variables

Turning first to the issue-related content of press releases, we classify party press releases into eighteen policy issue areas.Footnote 80 We measure the Media Issue Agenda as the share of newspaper articles dealing with the respective issue area on the day a press release is published.Footnote 81 Thus publishing a press release on an issue that is already salient in the media agenda should increase the probability that a party press release is successful. Data on the media issue agenda come from the AUTNES media content analysis of 6,512 articles in the eight newspapers listed above. Each article is assumed to contribute equally to the media issue agenda.

For Voter Issue Importance, we use a rolling cross-section voter survey carried out during the campaignFootnote 82 that asked respondents to identify the two issues in Austria that are ‘most important to you personally in the upcoming national parliamentary election’. Responses were classified using the eighteen issue areas mentioned above and weighted using survey weights. Interviews were conducted Monday to Friday; we pool observations over the last seven days to obtain indicators for voters’ perceived issue importance on a specific day.

We measure Party Issue Importance using data from the parties’ manifestos published before the election campaign. Based on the relational method of content analysis developed by Kleinnijenhuis and others,Footnote 83 each sentence in the manifesto was separated into the smallest possible full grammatical sentence. Using the same coding scheme as for the press releases and media reports, these statements are then coded into one of the eighteen issue areas.Footnote 84

Finally, we measure Party System Issue Importance as the number of rival parties that address the same issue on a specific day. Thus the measure ranges from 0 (no rival party addresses that issue) to 5 (all parliamentary parties address that issue).Footnote 85 We use this measure instead of the share of messages other parties devote to an issue because the daily number of press releases (on average about forty) is rather small for calculating shares based on eighteen issue areas. This is particularly true for weekends (when fewer press releases are sent) and for larger parties (as their smaller rivals also sent fewer press releases). Our simple measure (from 0 to 5) is less accurate than shares, but also less prone to distortion by a small number of observations.

Control Variables

There are several control variables that we need to take into account. To begin with, media attention is often biased towards the most powerful actors.Footnote 86 Thus parties in government are usually more visible in the news than opposition parties.Footnote 87 We account for this bias using a dummy variable that distinguishes between press releases sent by parties in government (1) and those in opposition (0).

Moreover, the media will privilege actors who are powerful within their own party.Footnote 88 Campaigns are powerfully shaped by the presence of the current party leaders; such ‘centralized personalization’ has been observed for Belgian,Footnote 89 British, Danish, DutchFootnote 90 and IsraeliFootnote 91 election campaigns. A similar logic should apply to party chairpersons, who often run the campaign and are responsible for its ‘spin’. The power of politicians in high public office makes them equally newsworthy for the media.Footnote 92 Other individuals who send out press releases are MPs and parliamentary candidates, party actors at the state and regional levels, heads of intraparty groups (for example, youth organizations) and members of the European Parliament. All these actors may be less interesting and newsworthy to the national media and therefore less successful at getting their messages into the media. We classify party actors who send out press releases as members of the national government (cabinet members and junior ministers), party leaders, party chairpersons, MPs, those in state (Land) governments or other individuals.Footnote 93 When no individual party actor is discernible, we use the category ‘party organization’. Most press releases are sent out by individual MPs, and we use this group as a reference category.Footnote 94

We also include a variable indicating the time a press release was published. Press releases published in the late afternoon or evening have fewer chances to get the media’s attention than those published in the morning. The variable indicates the time (in minutes) since midnight. We also include a variable specifying whether a press release is based on an external event (1) or not (0). The coding is based on a variable in the AUTNES content analysis of party press releases that captures the trigger of a press release. We consider a press release to be triggered externally if it is based on an event in the international arena (for example, an EU summit) or by national actors outside the party and media arena (for example, a report of the Austrian audit court). As mentioned above, we also measure whether a press release refers to a press conference (1) or not (0). Moreover, we account for text length (in words) because, all else being equal, longer press releases provide more information that is (potentially) useful for journalists.

Model Specification

Our dependent variable indicates whether a press release is successful (1) or not (0). Thus we use logistic regression models. Moreover, we cluster standard errors by issue area to account for the fact that some covariates vary only across issue areas.

RESULTS

Are party press releases effective means of shaping the media agenda? Figure 1 shows the share of successful party press releases by party. Overall, about 16 per cent of party press releases attract media attention. There is some variation across parties, but the differences are rather small. Moreover, there is no incumbency or size bonus in terms of the media presence of the two government parties (SPÖ and ÖVP). While the chances of each press release making the news are rather similar across parties, it is also worth noting that parties vary significantly in their campaign intensity. SPÖ (451), ÖVP (344) and FPÖ (475) issued substantially more press releases than the Greens (133), BZÖ (96) and Team Stronach (114). Therefore, given their roughly equal probabilities of making the news, the higher number of press releases issued by larger parties should lead to greater media visibility.

Fig. 1 Share of press releases in media reports, by party Note: The bars show the share of successful press releases by party, while the N in parentheses denotes the total number of press releases per party. The dashed line indicates the overall mean of successful press releases (N=1,613).

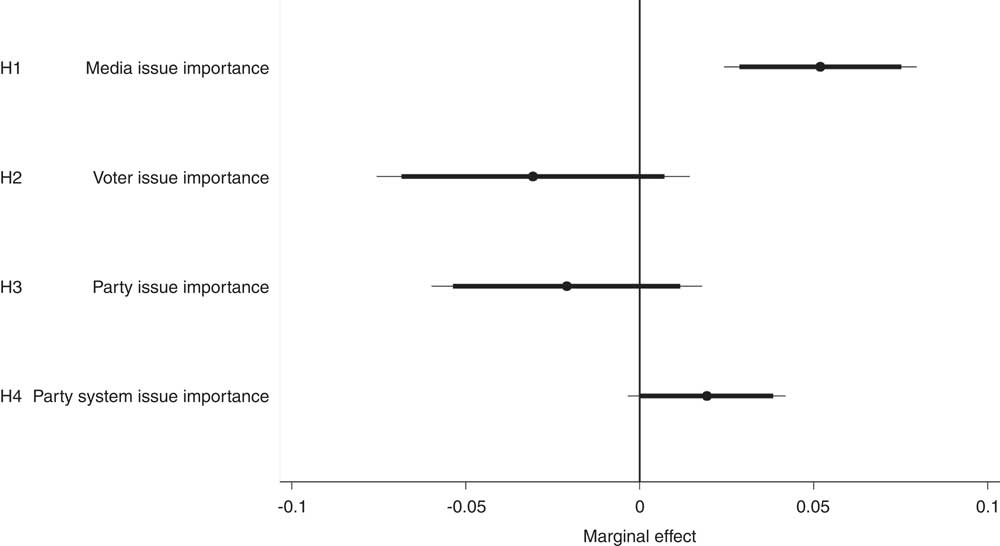

What factors account for the variation in press release success of getting the media’s attention? To answer this question, we estimate logistic regression models to explain the success of party campaign messages in making the news (Table 1). Model 1 shows the results for the full sample with 1,613 party press releases. To provide a meaningful interpretation of the magnitude of the effects, we show marginal effects plots for the variables of interest in Figure 2. Based on the estimates in Model 1, it shows changes in predicted probabilities for an increase by an interquartile range (that is, from the first to the third quartile).

Fig. 2 Marginal effects (Model 1) Note: Marginal effects based on changes from the first (p25) to the third (p75) quartile (i.e., interquartile range). Estimates based on Model 1 in Table 1. Thick lines denote 90 per cent confidence intervals, thin lines denote 95 per cent confidence intervals. All remaining variables are held constant at their mean or mode.

Table 1 Explaining Success of Party Press Releases (Logistic Regression Model)

Note: Standard errors in parentheses; + p<0.1, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Table 1 and Figure 2 provide support for the effects of message content. In Model 1, we find empirical support that media (Hypothesis 1) and party system issue importance (Hypothesis 4) increase the probability of making the news. Ceteris paribus,Footnote 95 increasing media issue salience from 2.7 to 12.0 per cent (that is, the interquartile range) increases the chances that a press release is successful by 5.2 percentage points (see Figure 2). Thus parties have higher chances of making the news when they address issues that are salient in the media issue agenda. Similarly, increasing party system issue attention from one to three rival parties addressing the same issue (that is, the interquartile range) increases their chance of getting the media’s attention by 1.9 percentage points.

In contrast, there is no evidence that voter and party issue importance affect party messages’ ability to make the news. In particular, party messages that deal with issues important to voters are, ceteris paribus, not more likely to make the news than those of less concern to voters (Hypothesis 2). This non-finding may be due to the way we measure the public issue agenda. Using the ‘most important issue’ question format (or its equivalent) to capture voters’ central concerns is quite common in the literature.Footnote 96 Yet these questions seem to measure what is important to the ‘typical’ voterFootnote 97 rather than what might attract a reader’s interest in the news. Thus voters may prefer media reports on exciting or conflictual issues rather than on worthy topics such as pension reform. There is also no evidence that the parties’ core issues affect the likelihood of their press releases making the news. As expected (Hypothesis 3), the effect is negative, meaning that the media is less likely to take up party messages on the parties’ main campaign issues. Yet the effect is not statistically significant at conventional levels.

Turning to the control variables, we find that members of the national government are the most likely to get the media’s attention. The probability that they will attract media attention is 25 percentage points higher than for MPs. There is also evidence that party office matters: party leaders and party chairpersons are more likely to make the news than other party actors. Being a party leader increases the probability of getting the media’s attention by 22 percentage points, while party chairpersons are about 9 percentage points more likely to make the news than MPs. At the party level, there is no evidence that campaign messages of government parties are more likely to get the media’s attention than those of parties in opposition. Moreover, press releases based on external events are not more likely to make the news. Yet there are positive and significant effects of text length and references to press conferences. Thus longer press releases and those summarizing statements made at press conferences have greater chances of getting the media’s attention. Finally, there is a tendency for press releases published later in the day to be less likely to make the news, but the effect does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance.

Taken together, these results suggest that political actors have higher chances of making the news with messages on issues that are important on the systemic (media or party) level. One might ask whether the media indeed has an independent effect (as suggested in Hypothesis 1) or whether its issue agenda results from the parties’ issue agendas. The empirical analysis in Table 1 accounts for the issues parties emphasize in their manifestos. Yet there may also be dynamic effects of the party system’s issue agenda on the previous day (at t−1) on both the media issue agenda at time t and a press release’s chances of getting media attention. To test this, we re-ran the analysis controlling for the party system’s issue agenda at time t−1. The results (shown in Appendix F) lead to similar conclusions as those discussed above: press releases are more successful if they focus on issues that are already salient in the media or to other parties.

Do these content-related factors also matter for politicians who cannot rely on actor-based media attention? To test this, we re-ran the analyses twice (see Table 1). Model 2 excludes top-level politicians (members of government, party leaders and party chairpersons), thus focusing on rank-and-file politicians. In Model 3, we restrict the sample to opposition parties. The results of both models are very similar to those in Model 1: rank-and-file politicians and opposition parties have higher chances of getting the media’s attention if their messages focus on issues that are already salient in the media’s agenda (Hypothesis 1) and those that are important to other parties (Hypothesis 4). This suggests that party actors, even those without top positions in public or party office, can increase their likelihood of making the news by talking about the ‘right’ issues.

As in Model 1, there is no evidence that political actors can increase their chances of getting the media’s attention by focusing on unfamiliar issues or those important to voters (Hypotheses 2 and 3). In fact, for opposition parties (Model 3 in Table 1) we find a negative and statistically significant effect of voter issue importance. Ceteris paribus, the media are less likely to draw on press releases of opposition parties that deal with issues that are central concerns of voters. The distinction between different issue types might explain this puzzle. For example, SorokaFootnote 98 distinguishes between prominent, governmental and sensational issues. Opposition parties such as the Greens and the radical-right FPÖ focused their campaigns more heavily on ‘sensational issues’ such as corruption. These issues might draw massive media attention,Footnote 99 but they are usually not the voters’ central concerns. The voters’ issue agenda is often dominated by ‘prominent’ issues such as unemployment or pensions, that is, issues that affect voters’ daily lives. The media is more likely to set the agenda based on sensational issues rather than prominent issues, and parties are in turn more likely to cater to the media agenda on issues such as corruption. In transmitting these issue agendas, the media is more likely to consider opposition party messages on sensational issues that are not the voters’ core concerns.

Could opposition parties do better when focusing more on the voters’ key concerns? It is difficult to answer this question using data from one country and one election. Government parties may have done a better job at addressing the public’s issue concerns, or they may have simply been lucky that voters were concerned about issues that were also their key priorities. Yet the insignificant effect of voter issue importance in Model 1 suggests that parties cannot increase their chances of getting campaign messages into the media by addressing voters’ key priorities.

CONCLUSION

Party press releases are rather effective means of attracting media coverage. Using data from the 2013 general election in Austria, we find that about 16 per cent of party press releases are successful at getting media coverage. Compared to other party tools (such as advertisements or newsletters), press releases are relatively cheap and quick to produce, may reach a large number of people and are available to a broader set of party actors. Moreover, many party actors and hundreds of press releases compete for journalists’ attention. Considering the low cost and administrative ease of sending out press releases, we see a 16 per cent success rate as relatively high. Our analysis focused on the message attributes that these successful press releases tend to have, and find that coverage is more likely for press releases that address issues that are important to other parties and the media. In contrast, voter issue importance and a party’s own core campaign issues are not associated with press release success.

These findings shed light on the success of electoral strategies and the media’s gatekeeping function, and have broader implications for electoral fairness and political representation in general. First, parties, particularly those in opposition, may find it easier to make the news if they focus on issues that are important to other parties. Studies on issue engagement analyse whether parties address the same issues or ‘talk past each other’.Footnote 100 Our analysis suggests that issue engagement may be useful to opposition parties as it increases their chances of getting the media’s attention.

Secondly, our results imply that issue entrepreneursFootnote 101 and new partiesFootnote 102 may fare better if they address issues that are already gaining interest among the media and other parties. For example, a party that focuses on a specific issue such as immigration or European integration may find media success once its issue becomes prominent on the news agenda or among other parties. This may help explain the breakthrough of new parties, niche parties and issue entrepreneurs.

A third, inverse implication of our analysis is that we show how the dismissive strategy identified by MeguidFootnote 103 and Bale et al.Footnote 104 may work in practice. These authors argue that mainstream parties can prevent competitors’ success if they refuse to address their issues. Our findings indicate a possible mechanism for this strategy. As the media will be more likely to ignore party messages if no other party takes up the issue, new parties may find it hard to place their topics on the public agenda without backing from the media or other parties.

Finally, our study adds to agenda-setting research. In showing that party press releases make the news if they follow the media’s issue agenda, our results suggest that the media might be more powerful than suggested in aggregate analyses of the party and media agenda.Footnote 105 Parties’ dependence on media gatekeeping may raise questions about the mechanisms of media gatekeeping and indicate a potential bias in the selection and coverage of campaign messages.Footnote 106

There is obviously much potential for future research on the media visibility of party campaign messages. Perhaps most importantly, we cannot be certain about the extent to which our findings are applicable to other multiparty systems, since virtually all existing research focuses on US presidential candidates and senators.Footnote 107 Following Hallin and Mancini’sFootnote 108 categorization of media systems, we may expect that our findings apply to other ‘democratic corporatist’ countries in Western and Northern Europe with similar media systems, especially countries that have similar party systems. Yet, like previous research,Footnote 109 we see a need for more comparative research on media gatekeeping and journalistic news selection to test such claims.

Moreover, we note that our study sheds little light on the success of party messages in making the news beyond election campaigns. Outside campaign periods, citizens usually pay less attention to politics,Footnote 110 while media coverage of politics differs in intensity and style.Footnote 111 Thus we cannot extrapolate from our findings to inter-election periods. For example, beyond election campaigns, party messages may be generally less likely to make the news, and party differences may increase compared to campaign periods. We hope future research devotes more attention to the success of party messages between elections.

Similarly, we could ask whether the 84 per cent of press releases that are not covered by the media may nevertheless serve a purpose. One possibility is that press releases, even those we deem to be unsuccessful, indirectly affect journalists and the media. For example, they may draw attention to scandals or important topics, even if their stimulus is not directly reflected in the final media report. It is also possible that political actors use press releases as a signalling device: they are a cheap tool that can be used to communicate with other party actors both within and across parties. If this is the case, then analyses of party press releases could also be used to study intra- and inter-party competition and party behaviour. Future research should therefore make increased use of the wealth of information contained in party press releases.