In Fall 2008, the Democratic candidate for president, Barack Obama, asked then-president and chief executive officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Timothy Geithner, whether he would consider serving as treasury secretary in a future administration. According to his autobiography, Geithner pointed out that he lacked the necessary political skills. The newly elected president from the ‘left’ party on the American political spectrum nevertheless chose the ‘economist’ after the election, and in the midst of a financial crisis. The new treasury secretary received daily training from the president’s chief of staff in an attempt to bolster his political skills but never really felt comfortable in his political role.Footnote 1

Is this anecdote representative of a broader phenomenon? One set of authors, writing more than two decades ago about the rise of economists in governments, argued that ‘the demand for economists rose radically with the sense of crisis’,Footnote 2 and later work notes that governments may appoint economists to top positions when the economy is in trouble.Footnote 3 But other scholars emphasize that left parties have credibility problems in government,Footnote 4 and do less badly with markets when they have constraints on them, such as International Monetary Fund programsFootnote 5 or domestic institutional barriers to change.Footnote 6 The Geithner anecdote could be representative of left-leaning presidents appointing economists to improve their credibility with markets.

When economists become policy makers remains poorly understood.Footnote 7 Early work on ministerial selection is largely descriptive.Footnote 8 Blondel finds that ‘specialists’ (appointments corresponding to prior training) are less frequent than ‘amateurs’, except in economic portfolios.Footnote 9 This work does not explain cross-national patterns and trends, and it excludes recent decades. Later studies find that competitive elections increase politician ‘quality’, for instance in terms of educational background.Footnote 10 However, the selection of finance ministers and central bankers is rarely studied, despite their crucial importance for fiscal and monetary policy.Footnote 11

If differences in economics background did not have policy implications, they may be best left for political biographies. Yet a growing literature associates the characteristics of leaders with economic growth,Footnote 12 public spending,Footnote 13 budget deficitsFootnote 14 and market liberalization.Footnote 15 The characteristics of cabinet ministers may affect social welfare and labor market policy.Footnote 16 The professional backgrounds of central bankers are linked to inflation.Footnote 17 German state finance ministers with previous financial sector experience have had more success in cutting deficits.Footnote 18 Chwieroth contends that, in emerging market economies, ‘neoliberal’ finance ministers and central bankers, identified by where they studied economics, are more likely to liberalize capital accounts and to cut social spending.Footnote 19 In addition, experimental work shows that individual behavioral traits, specifically levels of ‘patience’ and ‘strategic skills’, affect trade policy choices.Footnote 20 Yet none of these studies explain why some types of economic policy makers are selected in the first place. Perhaps the best work to combine a selection model with one on policy is the book-length treatment by Adolph, but it is limited to central bankers and emphasizes their career backgrounds.Footnote 21

This focus on individuals should be seen in a broader context of studies that examine partisanship and policy. Early debatesFootnote 22 from the 1970s concerned the trade-off captured in a Phillips curve between low inflation and growth, with right parties favoring the former and left parties the latter, but subsequent research on partisan cycles is mixed.Footnote 23 Some recent work considers whether partisanship affects the likelihood of crises, with one piece on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries suggesting that right governments are associated with the development of financial crises, while left governments have to deal with their consequences.Footnote 24 Myopic voters then move rightward as the consequences are longer lasting and voters blame the left.Footnote 25 Yet much of this literature assumes a monolithic ‘left’ or ‘right’. What is missing is the actor set.

We contribute the first comprehensive analysis of when economists become top-level ‘economic policy makers’, focusing on financial crises and the ideological position of a country’s leader. We present a new dataset of the educational and occupational background of 1,200 political leaders, finance ministers and central bank governors from forty developed democracies from 1973 to 2010. We find that left leaders appoint economic policy makers who are more highly trained in economics, and finance ministers who are less likely to have private finance backgrounds but more likely to be former central bankers. Finance ministers appointed during financial crises are less likely to have a financial services background. A leader’s exposure to economics training is also related to appointments. This suggests that one crucial mechanism for affecting economic policy is through the selection of certain types of economic policy makers. We speculate about future uses of the dataset to explore partisan economic cycles.

FINANCIAL CRISES, PARTISANSHIP AND APPOINTMENTS

A first question to consider is why leaders do not always appoint economists to economic policy roles. The work cited above and what we provide below indicate that the modal choice for finance minister is not an economist. Economists are more frequent as central bank governors, but even there one finds variation – the first Bank of England governor to hold a PhD in economics was Mark Carney, who was appointed only in 2013. Blondel argued that ‘specialists’ as ministers have substantial authority on a given topic both among cabinet colleagues and among civil servants.Footnote 26 At the same time, as our Geithner anecdote suggests, they often lack the more ‘political’ skills within a party and with voters more generally. If one presumes that leaders need first and foremost to get re-elected and that there are fewer agency losses in a principal–agent relationship when a ‘generalist’ is more sensitive to the political pressures facing the leader, all else equal, the leader would prefer a more political appointee to a more technocratic one. Under what conditions would the leader’s appointment preferences be reversed?

One possibility concerns financial crises. In addition to worries about voters, governments need to pay attention to investors, who can provide capital to get out of the crisis. If markets balk at a government’s rescue plan, it cannot borrow money when it needs funds quickly. The nature of the voter reaction to a financial crisis should also matter. Someone bears the costs of a financial crisis, and negotiating politically viable policies to address such a crisis is difficult. No private actor can buy out the financial sector, and it falls to the government to propose solutions and to execute decisions. Such crises impose different types of financial costs on government.Footnote 27 These costs tend to be largest in the advanced economies we examine.

Having an economist in charge of economic policy during a financial crisis may increase the government’s credibility with both markets and voters, and outweigh any expected agency losses for two reasons. First, there may be greater confidence that the policy maker knows the field and understands the problem. This knowledge can be crucial when a policy mistake can prolong a financial crisis.Footnote 28 Crises also focus attention on policy. Mosley finds that investment fund managers normally pay little attention to government policies in developed countries.Footnote 29 When there is a risk of sovereign default, however, they pay close attention. Domínguez cites the need to signal commitment to pro-market policies to investors as a reason for the emergence of ‘technopols’ in Latin America – technically skilled politicians, mainly economists.Footnote 30 Voters, however, care more about economic performance when a country falls well behind the performance of other countries.Footnote 31 When this is not the case, they consider a wider variety of policy issues.

A second reason relates to distributive politics. The politics of adjustment is about pushing the costs of reform onto political opponents.Footnote 32 The appointment of an economist may convey the message that traditional politics are at least suspended until after the financial crisis, with ‘efficiency concerns’ trumping ‘redistributive ambitions’.Footnote 33 This may be because experts have different career concerns due to incentives to demonstrate technical competence to their peers, in our case academic and professional economists, not (just) to win the next election.Footnote 34

Both arguments suggest that economists are more likely to become economic policy makers during financial crises than in non-crisis periods. We examine whether banking (or financial) crises increase the demand for economic policy makers with advanced economics training and who understand the financial industry. But demand could vary across different professional backgrounds: individuals seen as too closely associated with the troubled financial sector, such as former private bankers, are unlikely to inspire confidence during banking crises and may well be less likely to become policy makers at such times. Our data allow us to examine this nuance.

Hypothesis 1: Financial crises increase the likelihood that leaders appoint economists as economic policy makers.

Hypothesis 2: Financial crises decrease the likelihood that leaders appoint economists with a professional background in the finance industry as economic policy makers.

Next, consider how partisanship relates to potential agency losses for a leader. A crude way of thinking about partisanship is that left governments represent labor power while right ones represent capital.Footnote 35 If governments were simple mirrors of their constituencies, the left would have a union official as a finance minister while the right would have a banker. However, another important constituency is markets. Most governments must gain credibility with capital markets to finance the state and to reassure investors.Footnote 36 In the period we consider, ‘markets’ means ‘world markets’. To signal economic competence to distrusting markets, who indeed fear that the economic policy makers are simply direct copies of their leaders, left governments should be more likely to appoint economists.Footnote 37 This may be especially so during financial crises, when governments must borrow money from investors.

Hypothesis 3: Leaders from a left party are more likely to appoint economists as economic policy makers.

Hypothesis 4: Financial crises amplify the likelihood that leaders from a left party appoint economists as economic policy makers.

For central bank appointments, Adolph argues that the demand for relevant occupational backgrounds will vary in more subtle ways with government ideology. He predicts that left parties will appoint central bankers with ‘dovish’ occupational backgrounds, such as work in government or the central bank, while right parties will appoint people with ‘hawkish’ backgrounds, such as individuals who previously worked in the finance ministry or private finance.Footnote 38 This again fits the argument that leaders try to minimize agency losses in their economic policy maker appointments. Our data allow us to explore this relationship with a different sample, and we extend the analysis to finance ministers.

Hypothesis 5: Leaders from a left party are less likely to appoint economists with a professional background in the finance industry as economic policy makers.

Hypothesis 6: Leaders from a left party are more likely to appoint economists with a professional background in the central bank as economic policy makers.

Before we proceed, a caveat: it is not a priori clear that being an economist in itself is a desirable trait for an economic policy maker, and this is not our argument. A good manager with little economic competence may do as well, or better, than an economics PhD; a more politically inclined economic policy maker may be more successful at selling and implementing a given policy than an economics professor. Moreover, ministries and central banks have many staff who shape policy decisions.Footnote 39 We leave these aspects to future research.

VARIABLES AND DATA

We collected data on the educational and professional backgrounds of finance ministers and central bank governors. As we later examine whether economists as heads of government are less likely to appoint other economists, for comparison, we also include leaders. The dataset covers all twenty-seven European Union (EU) members as of 2010 and thirteen non-EU members of the OECD. It spans the years 1973 to 2010, but we only include democratic periods as indicated by a positive Polity score.Footnote 40 This yields data on 427 leaders, 537 finance ministers and 212 central bank chiefs.

We use two measures of academic training in economics. The first indicates an advanced (graduate) education in economics, in the form of either a masters or doctoral degree, or both. This coding is preferable to a simple indicator for a masters degree due to differences in tertiary education systems. For instance, many US students enter PhD programs directly from undergraduate study, whereas the first qualification awarded in some other countries is equivalent to a masters degree. Our second measure indicates a doctorate or PhD in economics.Footnote 41

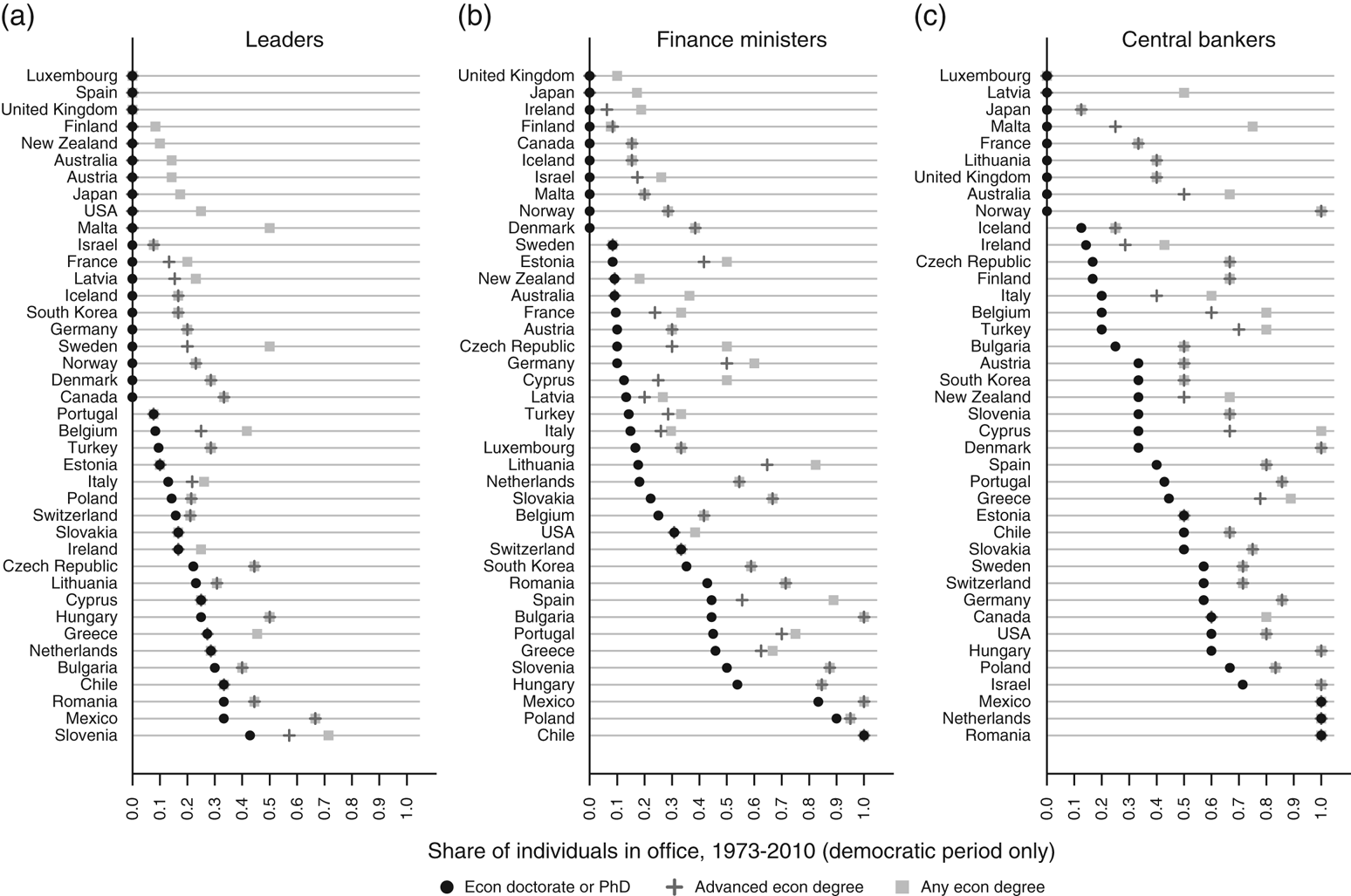

Figure 1 compares cross-country education patterns. Nineteen per cent (10 per cent) of leaders had an advanced degree (PhD) in economics. For finance ministers, the equivalent figures are 39 and 22 per cent. Ten out of the forty countries never had a finance minister with an economics PhD during the sample period. At the other extreme is Chile, where every finance minister since the restoration of democracy has had a PhD in economics, followed by Poland and Mexico. Moreover, three southern European countries at the center of the Eurozone crisis – Greece, Portugal and Spain – had better-trained finance ministers than most of their peers. In each case, more than half of them had an advanced degree in economics and about 45 per cent at the doctoral level. In nine countries, no central bank governor had a PhD in economics, but 62 per cent (34 per cent) of governors had an advanced degree (PhD) in economics. Across the three categories, central bankers have the highest level of economics training, followed by finance ministers and then leaders.

Fig. 1 Economics training by category of policy maker and country Note: the data appendix provides variable definitions and sources. Democratic years are defined as those with a positive Polity score. Years prior to the independence or creation of a country are excluded.

We also collected information on the professional trajectory of each economic policy maker prior to assuming office. We use these data to construct three measures of experience as a professional economist. They capture whether an office holder previously worked as an economics professor, in a central bank or in financial services (a commercial bank or the wider financial industry). Career backgrounds can cover multiple occupations, so these indicators are not mutually exclusive, and unlike our education variables they are not clearly correlated.

Figure 2 summarizes the share of policy makers with a given occupational background by country. We observe an association between prior careers and the likelihood that economics skills are important for a particular position. Compared with leaders and finance ministers, there are substantially more central bank governors with prior experience in central banking or financial services. Given that central bankers tend to have the highest levels of educational attainment across the three categories, it is also not surprising that academic economists are more prominent. However, as with educational background, the range of country averages is substantial, and these figures do not reveal when policy makers are most likely to have these characteristics.

Fig. 2 Occupational background by category of policy maker and country Note: the data appendix provides variable definitions and sources. Democratic years are defined as those with a positive Polity score. Years prior to the independence or creation of a country are excluded.

Our independent variables refer as precisely as possible to the time when an individual took office. We obtain indicators of banking crises from Laeven and Valencia.Footnote 42 Our measure of the ‘leftness’ of a leader’s party is based on Benoit and Laver’s 20-point left–right dimension score, standardized to a theoretical range from 0 (extreme right) to 1 (left).Footnote 43 We discuss alternative definitions and data sources as part of our robustness checks. The data appendix provides full details.

SPECIFICATION AND RESULTS

We estimate a baseline linear probability model in which the probability that an economist becomes an economic policy maker p in country c at time t is a function of our crisis and partisanship variables. We include country fixed effects to absorb time-invariant determinants, and decade effects account for the changing nature of academic training in particular – doctoral degrees were less common in the past:

$${\rm Economist}_{{{\rm pct}}} {\,\equals\,}\beta _{{\rm 1}} {\rm Left}_{{{\rm ct}}} {\plus}\beta _{{\rm 2}} {\rm Crisis}_{{{\rm ct}}} {\plus}{\rm Country}_{{\rm c}} {\plus}{\rm Decade}_{{\rm d}} {\plus}{\epsilon}_{{{\rm pct}}} $$

$${\rm Economist}_{{{\rm pct}}} {\,\equals\,}\beta _{{\rm 1}} {\rm Left}_{{{\rm ct}}} {\plus}\beta _{{\rm 2}} {\rm Crisis}_{{{\rm ct}}} {\plus}{\rm Country}_{{\rm c}} {\plus}{\rm Decade}_{{\rm d}} {\plus}{\epsilon}_{{{\rm pct}}} $$

The results in Panel A of Table 1 show that a leader from an extreme left party is about 19 percentage points more likely to appoint finance ministers with a PhD in economics (Column 2), and 28 percentage points less likely to appoint someone with a finance industry background (Column 5), than a leader from an extreme right party. Left leaders are also 22 percentage points more likely to appoint former central bank staff to the finance portfolio. During financial crises, individuals with a private finance background are 10 percentage points less likely to be appointed (Column 5). In contrast, the results for central bankers in Panel B of Table 1 reveal few patterns. Left leaders are more likely to appoint central bank heads with an advanced economics degree (Column 1). This coefficient is substantively large but imprecisely measured. The sample size for these regressions is small, as central bankers on average last longer in their jobs than finance ministers.

Table 1 Economists as Policy Makers, Main Results

Note: the estimates are from linear probability models with country and decade fixed effects (not reported). Standard errors clustered by country are in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

As our dependent variables are binary, we repeated the analysis using conditional (fixed effects) logistic regressions. Reassuringly, this yields an identical pattern of results (see Appendix Table A1). One drawback is that conditional logistic regressions are costly in terms of observations when variation in outcomes is rare and concentrated among some units. Moreover, the coefficients are less intuitive to interpret. Hence we prefer linear probability models, which are also standard in related work.Footnote 44

Next, we introduce a range of different specifications to examine the robustness of our findings. The full results appear in the online appendix. The first concerns the measurement of financial crises. Reinhart and Rogoff’s definition is broader and yields more appointments during a banking crisis, about 18 per cent of finance ministers and 21 per cent of central bank heads in our sample versus about 12 per cent for both categories with Laeven and Valencia’s data.Footnote 45 However, Reinhart and Rogoff cover fewer countries (thirty-two versus thirty-eight). For finance ministers, we get the same pattern of results, while crisis-time appointments to head the central bank are now more likely to have a PhD in economics (Table A2). Secondly, our results do not change with a wider crisis measure that also includes currency and debt crises as identified by Laeven and Valencia (Table A3).

We then augment our model with an interaction to allow the effect of partisanship to vary across crisis and non-crisis periods:

$${\rm Economist}_{{{\rm pct}}} {\,\equals\,}\beta _{{\rm 1}} {\rm Left}_{{{\rm ct}}} {\plus}\beta _{{\rm 2}} {\rm Crisis}_{{{\rm ct}}} {\plus}\beta _{{\rm 3}} {\rm (Left}_{{{\rm ct}}} {\times}{\rm Crisis}_{{{\rm ct}}} {\rm )}{\plus}{\rm Country}_{{\rm c}} {\plus}{\rm Decade}_{{\rm d}} {\plus}{\epsilon}_{{{\rm pct}}} $$

$${\rm Economist}_{{{\rm pct}}} {\,\equals\,}\beta _{{\rm 1}} {\rm Left}_{{{\rm ct}}} {\plus}\beta _{{\rm 2}} {\rm Crisis}_{{{\rm ct}}} {\plus}\beta _{{\rm 3}} {\rm (Left}_{{{\rm ct}}} {\times}{\rm Crisis}_{{{\rm ct}}} {\rm )}{\plus}{\rm Country}_{{\rm c}} {\plus}{\rm Decade}_{{\rm d}} {\plus}{\epsilon}_{{{\rm pct}}} $$

The coefficient on the interaction term is never significant at conventional levels: the appointment decisions of left leaders during financial crises cannot be distinguished from those in non-crisis periods (Table A4). For central bank heads, the joint effect of left partisanship in a crisis is significant at the 10 per cent level in the first education regression, showing that left leaders are likely to appoint a central bank head with an advanced economics degree during a financial crisis.

We also consider the possible effects of a battery of additional control variables. Markets and voters may care more about having an economist in place when debt levels are high, so we account for debt as a percentage of GDP.Footnote 46 Central bank independence might increase the likelihood that an economist is appointed as central bank governor. Moreover, it may be correlated with unobserved variables and affect finance minister appointments as well. We use Cukierman’sFootnote 47 measure of central bank independence as updated by Bodea and Hicks.Footnote 48 Coalition government may constrain appointments, with a party leader lacking an economics background more likely to become finance minister, and it makes delegation of monetary policy more likely.Footnote 49 We therefore include a dummy variable for coalition government.Footnote 50 Where political constraints increase policy stability, governments may not need to signal to markets their commitment to market-friendly policies because policy changes are unlikely.Footnote 51 We use the Henisz measure for political constraints.Footnote 52 Places with weak bureaucracies may compensate with economists at the top, so we include a measure for bureaucratic quality from the International Country Risk Guide. Finally, countries with higher capital mobility might be where capital favours technocratic governments. While decade dummy variables already capture common changes over time, we add the Chinn-Ito measure for capital account openness.Footnote 53

In the finance minister regressions, our core findings are stronger with these controls included (Table A5). In the central banker regressions, crisis and partisanship are now never statistically significant (Table A6). Interestingly, neither is central bank independence, but political constraints reduce the likelihood that a governor was an economics professor or had prior experience in central banking.Footnote 54

We further explored the context in which leaders are most likely to appoint economists. First, we restricted our sample to the advanced industrialized democracies of OECD members prior to 1993, excluding Turkey. The main results on whether a finance minister has a finance background hold, but none of the education results go through (Table A7). This is consistent with an interpretation that left leaders in emerging markets are more likely to appoint formally trained economists in order to assure investors of their commitment to market-friendly policies. Next, using the full sample and an augmented interactive model, we find no evidence that left leaders are under increased pressure to appoint economists the higher the stock of public debt (Table A8) or the lower the government’s political constraints (Table A9).

We conclude our analysis with an extension. Our dataset allows us to explore whether the perceived need to appoint an economist may be less when other senior policy makers already have such credentials. We augment the main model with our measure of advanced economics training for the leader and for the remaining economic policy maker (Table A10). Leaders with advanced economics training are more likely to appoint finance ministers with a central banking or private finance background, by 8 and 9 percentage points, respectively, but the academic training of the central bank head plays no role. When appointing finance ministers, leaders with economics training may reward relevant practical experience. Next, consider monetary policy makers. Central bank governors are, respectively, 24 and 17 percentage points less likely to have an advanced economics degree or PhD when they are appointed by leaders with an advanced economics education. They are also 31 percentage points less likely to have a private finance background when the finance minister has advanced economics training. These results strongly suggest that appointment decisions are not made in isolation, and reflect economics expertise across senior government roles.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

In the introduction, we used the appointment of Timothy Geithner as treasury secretary as an example of an economist becoming an economic policy maker. It was one observation, however, and there were different possible explanations for his appointment. Based on our analysis, the appointment as ‘finance minister’ of a central banker who had studied economics at the postgraduate level was more likely because the president came from a left party.Footnote 55 The example illustrates a wider pattern of increased demand for economists where markets and populations may be nervous about whether those in power are able to manage the economy.

More specifically, while we do not find that financial crises make the appointment of economists more likely (Hypothesis 1), those with a background in private finance are less likely to be appointed at such times (Hypothesis 2). We document an increased demand for economists when leaders from left parties are in power (Hypothesis 3), but at best weak evidence that this is amplified during financial crises (Hypothesis 4). However, left leaders avoid appointing finance ministers with professional experience in the financial industry (Hypothesis 5), and prefer those with a central banking background (Hypothesis 6). Adolph documents a similar pattern for central bankers, but we find it only for finance ministers. This could be because Adolph considers an earlier period, 1945 to 1998, during which central bank appointments were perhaps more politicized.Footnote 56

A growing literature considers the effects of the type of policy makers without paying attention to their selection. We demonstrate that partisanship systemically affects the initial selection of those policy makers. Our results should encourage more thought about the causal mechanisms that may undergird ‘partisan’ political business cycles in some fields, or perhaps why they do not appear in some studies. Clark and Arel-Bundock find that the decisions of the politically ‘independent’ US Federal Reserve Bank favour Republican presidents over Democratic ones.Footnote 57 Their evidence suggests that their model performs better than Abrams and Iossifov’s, who examine the partisanship of the president who appoints the Fed Chairman.Footnote 58 One reason may be that central bankers want to be in the finance industry after their central bank careers and are captured by the industry. While our results on central banker appointments are weak, we do find that left leaders are much more likely to appoint former central bankers than people with financial industry backgrounds to the finance ministry. This suggests that the loop between the financial industry and prominent government jobs has a partisan hue to it, and that it is more common under right governments.

A limitation of our study is that we look exclusively at the primary economic policy makers. There are other cabinet members who may influence policy, as Alexiadou shows for employment and social welfare policy.Footnote 59 Concerns about agency losses may weigh more heavily on the minds of leaders when markets do not demand a certain type of policy maker in a portfolio. While our extension shows that leaders do not make appointment decisions in isolation, future work could use our framework to assess the backgrounds of the wider set of cabinet ministers.