Modern welfare state regimes have deep historical roots, and early social interventions anticipated later policies of post-war welfare states (Castles Reference Castles1993; Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Estevez-Abe, Iversen and Soskice Reference Estevez-Abe, Iversen, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001; Flora and Heidenheimer Reference Flora and Heidenheimer1981; Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Petersen, Petersen and Christiansen Reference Petersen, Petersen and Christiansen2010). Long before the twentieth century, Denmark had many hallmarks of social democratic welfare states: citizen rights to social support, municipal responsibility to provide jobs to all, and early social investments in mass education. Pre-twentieth-century British policy anticipated the profile of liberal welfare regimes: no municipal jobs programs, no social rights, late mass education and passive, punitive poor supports (King Reference King1995; Weir et al. Reference Weir, Orloff and Skocpol1988). France, to become a Christian democratic welfare regime, fittingly relied largely on the Catholic Church and Christian charity for poor supports until the late nineteenth century; it lacked social rights and enacted mass education quite late (Kahl Reference Kahl2005). This diversity of anti-poverty interventions presents a puzzle: why did historical anti-poverty programs in Britain, Denmark and France differ so dramatically in their goals, beneficiaries and agents for addressing poverty?

We suggest that countries historically combatted poverty in such diverse fashion due to fundamentally different cultural views of poverty and the working classes. Whereas Danish elites articulated social investments in peasants and workers as part of the solution for augmenting economic growth, political stability and societal strength, their British counterparts viewed the lower classes as a challenge to these goals. The French perceived the poor as an opportunity for Christian charity.

Our article explores diverse views of poverty and develops a theoretical model of cultural work. Cultural actors and artifacts contribute to the context of the historical development of welfare regimes by offering a cultural lens through which other actors evaluate the problems of poverty, their own interests and potential modes of political engagement. Cultural work takes place through the structure of national cultural tropes and the agency of cultural actors. At a structural level, each country has a distinctive ‘cultural constraint’, or set of cultural tropes (symbols, labels, narratives and repertoires of evaluation), that appears in the national-level aggregation of cultural products (such as literature), persists through successive epochs and helps denizens of the country make sense of the world. Influences on the cultural symbols and narratives comprising the cultural constraint derive from authors’ ‘real’ life experiences and their creative renderings of reality. Yet authors also inherit symbols and narratives from the past: cultural tropes found in national corpora of fiction are passed down from one generation of cultural actors to the next and provide continuity of tropes over successive epochs. At the agency level, cultural actors apply cultural tropes to specific policy-making episodes. These actors specialize in putting neglected issues on the public agenda, ascribing meaning to social problems, and popularizing and legitimizing policy positions.

We use two methods to evaluate cultural work. First, we develop an empirically quantifiable method of testing cross-national distinctions in historical, literary depictions of poverty. We build corpora of national literature from 1700 to 1920 (including 562 British, 521 Danish and 498 French major fictional works) and construct snippets of text around words associated with poverty. Using quantitative text analyses, we calculate the frequency of words within the snippets associated with the goals (charity vs. skills), beneficiaries (individual vs. society) and agents (church vs. government) of welfare state policies. Secondly, we use process tracing in case studies to observe cultural actors' engagement in major episodes of welfare reform.

Our quantitative findings confirm that there are clear cross-national cultural differences in depictions of poverty in eighteenth-, nineteenth- and early twentieth-century literature in Britain, Denmark and France. Cultural depictions of poverty relevant to the goals, agents and beneficiaries of social interventions correspond to the values of each country's modern welfare regimes; therefore, we may reject the null hypothesis that cultural differences do not affect policy outcomes. Our case studies show that writers self-consciously engage as political actors by employing their cultural depictions in crucial episodes of welfare state development and, particularly in Denmark, that authors' political allies give writers credit for their contributions to political processes. We do not assert that cultural influences are more important than patterns of social cleavage and the demands of class actors, variations in religious sects or institutional rules for political engagement. Yet if cultural work provides context for the expression of class interests, culture serves as an intervening variable that helps other actors imagine their policy preferences and win the ideological war in policy battles.

We contribute to the political science literature by offering a model and method of evaluating cross-national, historical differences in cultural constructions of policy problems. Unexplained political phenomena are often attributed to cultural differences; yet apart from (contemporary) public opinion research, we have limited tools with which to assess empirically falsifiable, historical, cross-national, cultural distinctions. Our work improves on tautological, national cultural explanations of the past (Huntington Reference Huntington1996) to provide an independent measure of culture that is not derived from the institutional differences that cultural arguments purport to explain.

We advance welfare state theory by refining how a cultural lens adds context to compelling explorations of the impacts of religion, class struggle and political institutional rules in the development of early anti-poverty programs. As neglected actors in stories of policy evolution, authors and their cultural depictions of poverty help frame early efforts at poor support that establish path dependencies for modern welfare states before the advent of parties, unions, employers' associations and other agents in social policy development.

Classifying Welfare State Regimes

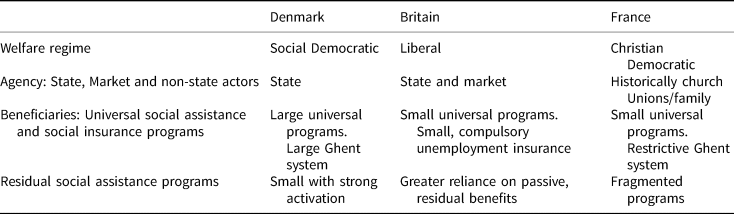

To understand the relationship between cultural depictions of poverty and welfare states, we must explicate cross-national variations in the institutional design of social programs to combat poverty. Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) identifies three ‘welfare regimes’: social democratic (for example, Denmark), Christian democratic (for example, France) and liberal (for example, Britain). Each regime has distinctive goals related to poverty reduction, primary beneficiaries of social support and agents responsible for administering programs.

In terms of goals, policy makers in all types of regimes develop social interventions to protect individuals from the social risk of poverty. Countries in liberal regimes rescue individuals from poverty with a minimum level of poor support and encourage private charitable activity for needy individuals (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990; King Reference King1995; Weir et al. Reference Weir, Orloff and Skocpol1988). Countries in Christian democratic regimes also focus on the individual; however, while liberal countries treat the individual as a poor person needing support, Christian democratic countries view the individual as a worker requiring a secure income (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Palier Reference Palier2010). Social democratic countries protect individuals from destitution, but they also use social investments, or policies to increase citizens’ skills and productivity, to support social and economic goals such as growth-enhancing investments in skills (Iversen and Stephens Reference Iversen and Stephens2008; Martin and Swank Reference Martin and Swank2012; Morel, Palier and Palme Reference Morel, Palier and Palme2012). These countries also used redistribution to achieve equality in the post-war period (Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Korpi and Palme Reference Korpi and Joakim1998).

These welfare state goals are associated with the different beneficiaries of social programs: targeted schemes serve specific individuals or (means-tested) groups, whereas universal programs offer benefits to the entire society. Liberal and Christian democratic welfare programs create benefits for specific individual groups (such as the elderly, children, the middle class or the poor). Social democratic welfare states are more likely to offer universal programs based on citizenship and social investment policies to help all contribute their work effort to society (Bonoli Reference Bonoli1997; Chevalier Reference Chevalier2016; Gough et al. Reference Gough1997). The goal of creating social provisions to strengthen society is very different from a government responsibility to rescue citizens from poverty, granting social rights to the poor or a view of charity as a social behavior; these instances all primarily focus on the needs and rights of the individual. Building a strong society requires every individual to have the necessary skills and citizenship qualities to make an economic and social contribution (Estevez-Abe, Iversen and Soskice Reference Estevez-Abe, Iversen, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001; Petersen, Petersen and Christiansen Reference Petersen, Petersen and Christiansen2010; Martin Reference Martin2018; Wiborg Reference Wiborg2000, 236).

Diverse welfare state regimes rely on different agents and tools to administer social programs. In liberal and social democratic regimes, governments (at the national or local level) provide social protections funded by taxes: liberal governments often fund means-tested social policies, while social democratic governments implement public services. Christian democratic countries make greater use of social insurance programs that are administered by non-governmental organizations (unions and/or the Church) and funded by workers' and employers' contributions (Castel Reference Castel1995; Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001).

To explain such diversity, scholars analyze the origins of the development of welfare states with explorations of economic, political, institutional and religious factors. The economic origins of this evolution are related to industrialization, because capitalist production generates greater social risks (Rimlinger Reference Rimlinger1971; Wilensky Reference Wilensky1975). The ‘power resources’ approach examines the political origins, for instance by exploring the role of trade unions and left-leaning parties (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Korpi Reference Korpi1983). The institutional origins relate to electoral institutions and associated political co-ordination (Cusack, Iversen and Soskice Reference Cusack, Iversen and Soskice2007; Flora and Heidenheimer Reference Flora and Heidenheimer1981, 47; Martin and Swank Reference Martin and Swank2012; McDonagh Reference McDonagh2015). Lastly, studies stress religious influences on welfare development, such as church/state struggles over state building, the crucial role of Christian democratic parties in continental welfare states and doctrinal differences in religious sects (Kahl Reference Kahl2005; Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967; Van Kersbergen and Manow Reference Van Kersbergen and Manow2009).

These works largely focus on the golden age of welfare states after the Second World War, and pay some attention to the late nineteenth century. Yet important cross-national divergence in treatments of poverty date back to at least the eighteenth century. Granted, policy ideas about social protection have changed over time. For example, Enlightenment ideas about poverty and the need for labor mobility encouraged outdoor relief for workers, workhouses became more popular with the rise of economic liberalism in the mid-nineteenth century, and structural risks associated with globalization prompted less punitive social insurance protections at the turn of the twentieth century (Quadagno Reference Quadagno1988). Yet by 1802, Denmark had already mandated local governments to provide jobs for all citizens and linked poor support to social investment in mass education; all citizens were granted the right to social support in 1849 (Petersen, Petersen and Christiansen Reference Petersen, Petersen and Christiansen2010, 15). Britain offered only limited relief (largely to the deserving poor), did not require municipalities to provide jobs, did not connect poor relief to skills development and did not recognize social rights during this period. France largely left poverty under Catholic Church control until the late nineteenth century, offered only passive benefits, emphasized charity and neglected skills (Manow and Palier Reference Manow, Palier, Van Kersbergen and Manow2009). Table 1 reports early distinctions among poverty regimes.

Table 1. Institutional design of welfare regimes at the beginning of the twentieth century

Our study investigates how culture intersects with cross-national distinctions in welfare regimes, following the work of others studying culture. Petersen, Petersen and Christiansen (Reference Petersen, Petersen and Christiansen2010, 39) view the formation of collective identities as central to Danish welfare state development. Cox (Reference Cox1992) draws attention to deep cultural logics that inform alternative systems of social delivery (See also Castles Reference Castles1993; Svallfors Reference Svallfors1997). Conceptions of the good society differ across social democratic, Christian democratic and liberal welfare regimes (Oorschot, Opielka and Pfau-Effinger Reference Van Oorschot, Opielka and Pfau-Effinger2008). Ideas and values shape the policy foundations of comparative political economies (Hall Reference Hall1993; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008). We contribute by offering greater specification of the mechanisms through which cultural artifacts resonate with political reforms.

Model of Cultural Work

We suggest that cultural actors and artifacts contribute to the historical development of welfare regimes by offering a cultural lens through which other actors evaluate the problems of poverty, their own interests and possible modes of political engagement. Changes in socio-economic circumstance, class power and dominant political philosophies periodically prompt countries to adopt new social policies. Cultural values influence the interpretation of new policy ideas and social groups' preferences for specific policy tools. Cultural work happens through the structure of national cultural tropes and the agency of cultural actors.

The Structure of National Culture: ‘The Cultural Constraint’

At a structural level, each country has a distinctive ‘cultural constraint’, comprised of the national-level aggregation of cultural symbols and narratives appearing in cultural products such as literature. The cultural constraint is predicated on the idea that political and social actors draw from a country-specific ‘cultural toolkit’ to formulate strategies and ascribe meaning to social problems (McNamara Reference McNamara2015; Swidler Reference Swidler1986, 273–6). Symbols and narratives include ‘repertoires of evaluation’ or cultural constructs that mold our assessments of the collective good and suggest symbolic boundaries among social groups (Lamont and Thévenot Reference Lamont, Laurent, Lamont and Thévenot2000). The toolkit is heterogeneous and does not predict specific choices; yet cultural tools and ‘repertoires of evaluation’ are unevenly distributed across nations. Some countries are more likely to access certain cultural tropes than others (Lamont and Thevenot Reference Lamont, Laurent, Lamont and Thévenot2000, 5–6; Berman Reference Berman1998; Berezin Reference Berezin2009). This national-level aggregation of cultural products persists through successive epochs, is used by cultural actors to depict social and political phenomena, and helps citizens interpret their world. We investigate the cultural constraint in literature (a rich source of symbols and narratives), but it also appears in other cultural forms.

Influences on the cultural symbols and narratives comprising the cultural constraint derive from three sources: ‘real’ life experiences of authors, their creative renderings of reality, and inherited symbols and narratives from the past. First, authors write about life as they know it; their depictions reflect the core values of their societies, assumptions about political engagement, patterns of class conflict, religious beliefs and norms of political institutions. Dickens' portraitures most certainly describe his childhood in the London slums. Yet cultural expectations and institutional rules, class relations, etc. may co-evolve and have a mutually reinforcing relationship, as Macfarlane (Reference Macfarlane1973) shows in his study of British individualism dating back to the thirteenth century. The practice of English nationals living in nuclear families (unlike in continental Europe) reinforced norms of individualism, and individualistic norms reinforced nuclear family living. Since cultural assumptions are deeply interwoven with institutional and class arrangements, it is difficult to assign causal weight to culture in historical development.

Secondly, cultural sociologists are quick to point out that cultural actors do not simply reflect national values and reproduce perfect images of life. Authors' own creative renderings of reality may realign perceptions; in particular, great artists with unique voices may create new interpretations (Schwarz Reference Schwarz1983). Thus Dickens chooses to emphasize certain themes, such as the mistreatment of children, in his depictions of Victorian poverty.

Thirdly, writers are also influenced in their contemporary depictions of social issues by cultural touchstones they inherit from the past. Symbols and narratives found in national corpora of fiction are passed down from one generation of cultural actors to the next. Fiction writers act collectively as purveyors of the cultural symbols and narratives of their national literary traditions, and conjure up symbols from the past to bear upon present problems (Williams Reference Williams1958). Some novels certainly challenge the master narratives of their literary traditions, and cultural constructs and cannons evolve over time (Poovey Reference Poovey1995, 7). Yet even as each generation redraws cultural touchstones, there is continuity in tropes over successive epochs. Familiar touchstones inform the ‘political unconscious’ (or gap between authors' intended goals and their subtext messages) that is unacknowledged by the text (Jameson Reference Jameson1981; Fessenbecker Reference Fessenbecker2016). Kipling recognizes the power of the national corpus when he writes: ‘The magic of Literature lies in the words, and not in any man. Witness, a thousand excellent, strenuous words can leave us quite cold or put us to sleep, whereas a bare half-hundred words breathed upon by some man in his agony, or in his exaltation, or in his idleness, ten generations ago, can still lead whole nations into and out of captivity’ (Kipling Reference Kipling1928, 6).

The Agency of Cultural Actors: The Dynamics of Cultural Work

Cultural artifacts must be marshalled to have relevance for historical welfare state development. Therefore, we also observe the agency of cultural actors in policy-making episodes at critical junctures of welfare state development, as authors use cultural artifacts in historically contingent ways to support new political agendas (Berman Reference Berman1998; Berezin Reference Berezin2009). Cultural actors' comparative advantage as purveyors of cultural artifacts shapes their contribution to public policy in three ways.

First, fiction writers join other intellectuals as the avant garde in putting neglected issues on the political agenda. In pre-democratic regimes, literature was a crucial medium for intellectuals to debate issues, shape public consciousness and influence rulers (Keen Reference Keen1999, 33). British social problem novelists used their fiction to address issues such as poverty to which politicians paid scant attention. Novels are a terrific medium for inspiring emotional commitments to social concerns; Uncle Tom's Cabin did not cause the US Civil War, yet it fanned the outcry against slavery (Guy Reference Guy1996, 11).

Secondly, writers engage in framing by ascribing specific meaning to economic, social and political problems and solutions; it is also important to note evidence that policy makers receive and use cultural artifacts to explain problems (Griswold Reference Griswold1987). Narratives have enormous influence on our beliefs and assessments about how the world works; imaginaries shape economic action (Beckert and Bronk Reference Beckert, Bronk, Beckert and Bronk2018, 4). Victorian novelists helped define poverty and the suffering of working-class children in a culturally specific way (Carney Reference Carney2017; Childers Reference David2001; Poovey Reference Poovey1995). Of particular interest to this article is how authors frame the beneficiaries (individual vs. society), goals (charity vs. social investments in skills) and agents (church vs. state) of interventions to resolve social problems. For example, Matthew Arnold sought mass education to facilitate individual self-development: the ‘grand aim of education’ for the middle class is ‘largeness of soul and personal dignity’; culture brings ‘feeling, gentleness, humanity’ to the lower classes (Kuhn Reference Kuhn1971, 53).

Thirdly, activist writers may participate in coalitions with political allies to win policy battles: they particularly use cultural touchstones to legitimate and popularize esoteric policy ideas among a wider public. In this regard, Herman Bang in Tine (Reference Bang and Christophersen1984[1889]) credits, blames and implicitly recognizes the role of the old poets who with patriotic words brought Denmark to the disastrous 1864 war: ‘It is the poets who have filled us with fresh visions and heralded the new age…it is his visions that have carried us to this day…even if they were only illusions…his is the responsibility’ (Bang 48). Within these coalitions, authors use cultural tools to legitimize or challenge structures of authority, as when bildungsroman convey norms of appropriateness (Apol Reference Apol2000). Groups may compete over the formation of national identities and offer diverse national myths to claim legitimate political authority (Keen Reference Keen1999, 2; Poovey Reference Poovey1995, 15).

Some writers publicly work with political parties and movements, and even serve in Parliament. Others protect their role of legitimizing specific positions by hiding behind their art to claim political neutrality; this may be one reason why their influence has been relatively understudied by political scientists. Thus even as Matthew Arnold carefully reviewed drafts of his brother-in-law's Education Act of 1870 (establishing British mass education), he avoided explicitly political public activities. As he wrote to his mother on 17 October 1871, ‘things in England being what they are, I am glad to work indirectly by literature rather than directly by politics’ (Arnold Reference Arnold1900, 7vc7.) Hardy argued that political neutrality was necessary in a letter to Robert Pearce Edgcumbe on 23 April 1891: ‘the pursuit of what people are pleased to call Art so as to win unbiassed attention to it as such, absolutely forbids political action’. Coleridge vigorously participated in the Tory, Anglican school-building effort, yet he wrote to Beaumont in December 1811, ‘I detest writing Politics, even on the right side’ (Coleridge Reference Coleridge and Griggs1956, 352.)

We make note of our causal claims. We cannot definitively argue that cultural actors and artifacts have a causal impact on the development of welfare state regimes; that is, that without writers' depictions, welfare regimes would have developed differently. It may be that writers were simply influenced by the societal values and material conditions of their times. Alternatively, it may be that authors were agents of ideational change and played a crucial role in shaping modern welfare states. But in either case, we use quantitative evidence to verify cross-national differences in cultural depictions of poverty and show that these correspond to cross-national variations in welfare regimes. Thus we can disprove the null hypothesis that culture does not affect welfare state development. Moreover, following Falleti and Lynch's (Reference Falleti and Lynch2009) model of context in causal processes, we view the cultural constraint as part of the ‘context’ of policy making. The cultural constraint does not have an independent causal effect, but it structures how other factors influence welfare regime development (see Figure 1). This is similar to how public opinion structures the effect of political parties (Busemeyer, Garritzmann and Neimanns Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann and Neimanns2020). Thus, we suggest an ‘effects-of-causes’ rather than a ‘causes-of-effects’ approach by stressing the relevance of a factor without claiming that it fully explains the outcome (Mahoney and Goerz Reference Mahoney and Goerz2006).

Figure 1. Causal logic of argument

Note: I = inputs; M = mechanisms; O = outputs

Source: Falleti and Lynch Reference Falleti and Lynch2009

Hypotheses

We use quantitative evidence (discussed below) to evaluate the predicted correspondence between the underlying values attributed to welfare state regimes and the values found in literary depictions of poverty. We expect to find that texts referencing poverty should have different associations with the goals (skills vs. charity), beneficiaries (society vs. individual) and agents (state vs. church) of social protection in Denmark (a social democratic welfare regime), Britain (a liberal welfare regime) and France (a Christian democratic welfare regime). We offer the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: References to skills words should be greatest in Denmark, where social investment policies are crucial goals of welfare state provision; references to skills words should be lowest in France, where Christian charity was central to anti-poverty interventions.

Hypothesis 2: References to charity words should be greater in France, which emphasized Catholic charity, and Britain, which sought relief for deserving poor individuals, than in Denmark.

Hypothesis 3: References to society words should be greater in Denmark than in Britain and France.

Hypothesis 4: References to individualism words should be greater in Britain and France than in Denmark.

Hypothesis 5: References to family words should be greater in Britain and France than in Denmark (which emphasizes society and workers).

Hypothesis 6: References to government words should be greater in Denmark and Britain than in France. References to government in Britain should be lower than in Denmark, because liberal welfare states combine government provision with a reliance on benefits obtained through markets.

Hypothesis 7: References to religious words should be greater in France, which historically relied on church provision of social protections, than in Britain and Denmark.

Hypothesis 8: An increase of references to poverty in fiction should anticipate significant political reforms in all countries.

Table 2 summarizes the words that we expect to find for each policy dimension of the diverse welfare regimes.

Table 2. Words associated with each policy dimension of diverse welfare regimes

Quantitative and Qualitative Methods

We use two methods to substantiate our claims: (1) a quantitative analysis of large corpora of national works of fiction to evaluate our structural arguments about culture and (2) comparative case studies to evaluate the agency of cultural actors in episodes of policy reform. First, our quantitative analysis uses computational linguistic techniques (in Python) to test observable differences in depictions of poverty appearing in corpora of British, Danish and French novels, poems and plays between 1700 and 1920 (after which copyright laws limit access). The list of fictional works in the corpora were compiled from country collections of national literature (for example, the Archive of Danish Literature) and from online lists of important works and authors from the eighteenth to early twentieth centuries.

The Danish corpus includes 521 works; the British, 562 works; and the French, 500 works. Full text files are provided by national archives and HathiTrust. We recognize bias both in the initial publication of works (slanted toward upper-class male authors) and in online lists of important works; however, we avoid adding bias by deferring to expert judgment about the collections. The Danish and French corpora include virtually all works available online; where some choices were made about inclusion in the British corpus, we randomly sampled works from all authors on our lists. Because available full-text files are often not first editions, we manually altered the dates of works to reflect their initial publication. The timing of publication is crucial for establishing the sequential relationship between cultural artifacts and reform moments.

We expect to find cross-national variations in cultural scripts about poverty that correspond to the characteristics (goals, beneficiaries and agents) of contemporary welfare states. We construct snippets of fifty-word texts around poverty words, stem the corpora and take out stop words. We calculate temporal and cross-national variations in word frequencies that reference goals (charity vs. skills), beneficiaries (individuals vs. society) and agents (church vs. government). A supervised learning model is appropriate because our categories are specified by theory: our object is not to assess how an individual document fits into a corpus, but to investigate cross-national and temporal differences among works that are presorted by country, language and time (Hopkins and King Reference Hopkins and G2010; Laver, Benoit and Garry Reference Laver, Benoit and Garry2003). We calculate difference-of-proportions tests to evaluate significant differences between countries.

We derive our major concepts (government, church, etc.) from theoretical discussion, but we must make choices about the specific words included in each concept. We initially generated lists of words for each category by identifying the top 200 words in major novels using the HathiTrust word cloud software and coding these words into appropriate groups. We then added synonyms derived from online dictionary searches. We also looked at the frequency of words found in the corpora and chose the most frequently used words, as we sought to give all languages the opportunity to perform in each category. But we also carefully avoided words with multiple meanings such as ‘society’, which in English refers to both upper-class ‘high society’ (most prevalent usage) and the community of people living in a country with shared customs, laws, etc. We instead used the term ‘social’. We used ‘poverty’ and other words connoting poor people; however, we did not use ‘poor’ (stakkel in Danish) as it could refer to an impoverished person, a suffering person (‘poor you’) or an inferior. The political terminology used to refer to a concept often changes over time. Thus bienfaisance and charité may both be translated as ‘charity’; however, they are used during different historical periods. We control for this problem by including relevant terms from all periods under investigation and by including varied spelling of words (for example, Dannemark and Danmark). We have widely read fiction from this era and make sure to use historically appropriate words (see the Appendix).

Our second method uses process tracing in brief case studies to evaluate how authors engage in significant welfare reform episodes in Britain, Denmark and France. We seek evidence that networks of authors put the issue of poverty on the public agenda in decades preceding significant policy acts. We explore how major works framed the problem of poverty in light of the goals, beneficiaries and agents of poverty reduction. We identify how cultural actors became involved with political coalitions for poverty reforms and document authors' influence on policy makers. While we cannot prove that authors' activities were the determining factor in social struggles, process tracing allows us to demonstrate that fiction writers played the predicted role as political actors in coalitions for policy change; in some cases, their contemporaries credit them with contributing to reforms. We primarily cite authors of major works, who engaged with the political debate. This choice creates a bias against authors with minority voices, but it accurately highlights authors who wielded political power. Less influential authors are included in our quantitative corpora; their voices are thus preserved in the overall cultural profile of literary output.

Quantitative Findings

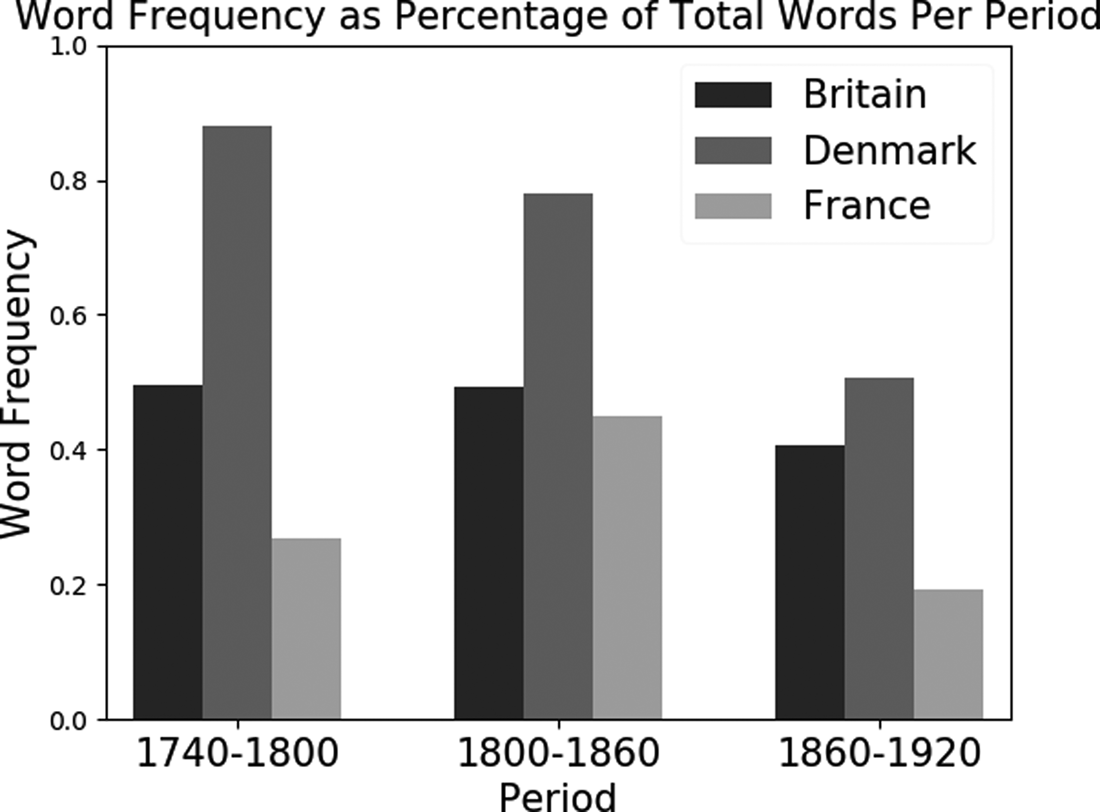

Analyses of the British and Danish corpora using machine-learning techniques show significant and largely predicted differences (the Appendix reports the results of difference-of-proportions tests). Figure 2 shows Denmark has the highest number of references to poverty. Some increase in poverty words precedes reform moments in 1800 and 1900 in Denmark, and 1800 and 1860 in France.

Figure 2. Frequencies of all poverty words

Note: word frequency as percentage of total words per period. words include poverty, pauper, destitute, needy, indigent, beggar, mendicant.

Figure 3 shows that frequencies of skills words are significantly higher in Denmark than in Britain or France for most periods. In all three countries, skills are more important to poverty at the end of the eighteenth century with Enlightenment ideas, decline with the punitive attitudes toward poverty in the mid-nineteenth century, and rise again at the end of the century (see the appendix for means-of-proportion tests).

Figure 3. Frequencies of skills words (within poverty snippets)

Note: word frequency as percentage of total words per period. words include skill, ability, capacity, competency, qualification.

Figure 4 illustrates that charity words are significantly more frequent in British and French snippets than in Danish ones (where these are non-existent in some periods). Britain scores higher than France in the late eighteenth century because poverty was so often associated with suffering (often upper-class) women rather than workers.

Figure 4. Frequencies of charity words (within poverty snippets)

Note: word frequency as percentage of total words per period. words include charity, benevolence, philanthropic and beneficence.

Figure 5 confirms our predictions that Denmark's social democratic welfare regime has, for most periods, significantly higher frequencies of society words than Britain and France (for some periods). Society references are highest in France and lowest in Britain during the French Revolution.

Figure 5. Frequencies of society words

Note: word frequency as percentage of total words per period. words include England, English, Britain, country, folk, people, collective, communal, mutual, custom, social.

Figure 6 confirms our prediction that individual words are higher in Britain and France than in Denmark. Individualism declines somewhat in Britain in the late nineteenth century with the move toward perceptions of structural poverty. Figure 7 shows that family words are also significantly higher in Britain and France than in Denmark, as predicted.

Figure 6. Frequencies of individualism words (within poverty snippets)

Note: word frequency as percentage of total words per period. words include individual, independent, person, character, liberal, self.

Figure 7. Frequencies of family words (within poverty snippets)

Note: word frequency as percentage of total words per period. words include family, marriage, children, parent, mother, father.

Figure 8 shows that Denmark has the highest frequency of words associated with government, followed by Britain and then France. References to government words decline in Denmark at the end of the nineteenth century with the rise of the non-state co-operative movement and industrial self-regulation.

Figure 8. Frequencies of government words (within poverty snippets)

Note: word frequency as percentage of total words per period. words include nation, government, law, council, commission, power, public, legal, committee, king, kingdom, emperor, crown, throne, municipal, parish, illegal, court.

Figure 9 does not confirm our expectations that religion words will be most frequent in France because the church is historically responsible for social provision. Although France scores higher than Britain, Denmark has the highest frequency of religion words. This finding is consistent with the view that the Lutheran church acted as a stand-in for local government in early state development in Denmark (Knudsen Reference Knudsen and Knudsen2000); a strong church is consistent with a strong state, unlike in France. Religious words in Denmark are particularly frequent during the evangelical activism of the mid-nineteenth century; these words decline everywhere with the secularization at the end of the century.

Figure 9. Frequencies of religion words (within poverty snippets)

Note: word frequency as percentage of total words per period. words include religious, rectory, church, cathedral, dissenter, Anglican, priest, God, spirit, bishop.

Thus, our findings largely confirm our hypotheses. In Denmark, we find high word frequencies on the ‘state’, ‘skills’, ‘society’ and ‘religion’ dimensions. In Britain, we find medium-high word frequencies on the ‘state’ and high frequencies on the ‘individualism’ and ‘charity’ dimensions. In France we find high word frequencies on the ‘church’, ‘individualism’ and ‘charity’ dimensions. While cultural depictions in each country also respond over time to shifting economic climates, class struggle, political institutions and dominant ideas about the public space, cross-national differences among countries endure.

Case Study Findings

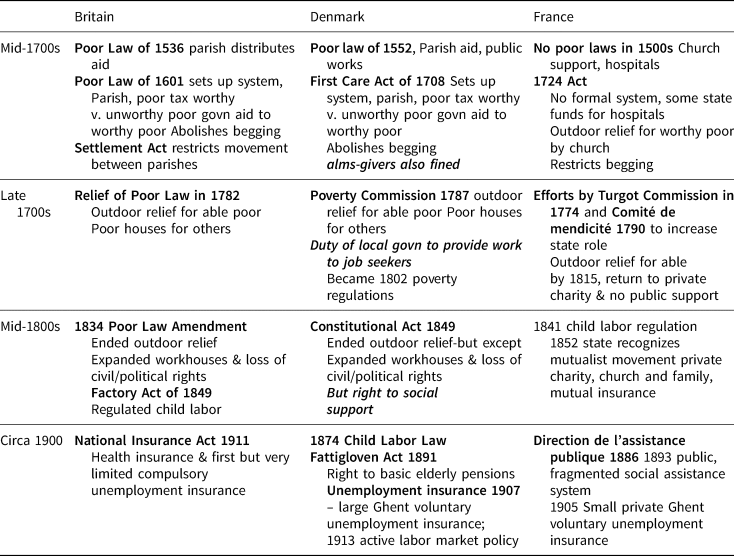

This section describes the process tracing of crucial cases to document authors' involvement with policy-making episodes, focusing on the early nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when countries finally developed social insurance programs. Table 3 summarizes the historical differences in the development of welfare states in Britain, Denmark and France.

Table 3. Historical differences in social policy

Denmark

In 1700, Denmark was a primitive land with low productivity, serfs and a low standard of living. Yet by the end of the century, Enlightenment-inspired reforms had transformed Danish society and prevented the French Revolution from significantly affecting the country (Christiansen et al. Reference Christiansen, Johansen and Petersen2010, 111–15). The Poverty Commission of 1787 (Fattigkommissionen af 1787) charged municipalities with providing work, shelters for the unemployed, hospitals for better health care and homes for the impoverished elderly. A mass education system was created alongside these poverty reforms. Regulations introduced in 1802 and 1803 intensified prohibitions against begging, but created a poverty tax to provide resources for the poor (Wessel Hansen Reference Wessel2008, 179). Eighteenth-century advocates who sought to improve the lives of peasants linked social reforms to the expansion of agricultural productivity, sought social investment in education, and presupposed that peasants’ social stability was necessary to the mandates of economic growth (Sundberg Reference Sundberg2004, 146).

Authors put poverty, education and land reforms on the public agenda long before the 1787 commission. In the 1720s, Ludvig Holberg (the ‘father of Danish literature’ and an expert on Nordic mythology) began writing plays in the Danish language, featured peasant characters (in a break with the past), and consistently emphasized poverty's negative impact on society, the importance of building skills and the necessity of state intervention. For Holberg, poverty harmed both individuals and society; therefore, it was in the interests of estate owners to improve the lives of their peasants. ‘Whoever loves himself should act in a benevolent way toward his peasants, as there is a union between their interests. The devastation of the peasant will be the devastation of the estate’ (Holberg 1971, 1720_191–216). Holberg's title character in his 1741 adventure novel, Niels Klim's Journey Under the Ground, complains that his skills are not being sufficiently recognized. He is told that the collective comes first: ‘Merit ought to be rewarded, but the reward should be adapted to the object, that the State may not suffer’ (Holberg Reference Holberg and Gierlow1845[1741], 807 of 1846).

Holberg was immensely important to Enlightenment reformers and writers alike through his work and by bequeathing his fortune to the Sorø Academy, a school for educating future statesmen. The academy adopted Holberg's ideas (teaching in Danish, encouraging study of the old Nordic myths) and hired his former students such as Jens Schielderup Sneedorff (later tutor to the crown prince), who wrote that peasants should be honored members of society (Plesner Reference Plesner1930, 20–28). Sorø educated estate owners, such as Christian Ditlev and Johan Ludvig Reventlow, who would head the Poverty, Education and School commissions set up in the 1780s. In a letter dated 19 June 1770, Ludvig wrote to his sister Charlotte: ‘I believe with you that the greatest happiness of the state is to have happy and rich peasants instead of a few wealthy landowners’ (Bobe II, 3).

Romantic poets and playwrights at the century's end affirmed that a strong society required the participation of all classes of people. Adam Oehlenschläger (the country's most famous poet before 1870) presented his vision of the ‘organic society’ in an 1800 prize-winning essay considering ‘Would it be beneficial to Scandinavian belles lettres if old Norse mythology were introduced and generally adopted in place of Greek mythology?’ (Hanson Reference Hanson1993, 181; Mai Reference Mai2010). Oehlenschlager's evil title character in Hakon Jarl (1805) is contemptuous of society, ‘as afraid Of his own warriors as he is of’ the enemy (93), steals farmers' daughters and prefers to rely on slaves (105).

After the crown prince and his close associates (including the Reventlow brothers) staged a bloodless coup in 1784, writers were important allies in political coalitions to reform the Danish political economy and to provide legitimacy for the new regime. Oehlenschlager and other writers met to discuss crucial issues of the day at the Drejer's Klub and formed the Society for Future Generations (which civil servants also joined) to nurture citizenship and disseminate useful knowledge (Bokkenheuser Reference Bokkenheuser1903, 24–5; 177–182). In 1785, Christen Henriksen Pram and Knud Lyne Rahbek (from the Drejer's Klub) started a journal, Minerva, that featured articles on art and politics and included among its 496 subscribers 41 members of the extended royal family (Munck Reference Munck1998, 216). When reactionary estate owners from Jutland opposed the reforms, writers intervened with a war of words to ardently support the new regime and the end of serfdom. Knud Rahbek claimed that writers were as crucial to the late-eighteenth-century reforms as civil servants such as Bernstorff, Reventlow and Coljbørn (Bokkenheuser Reference Bokkenheuser1903, 116–118).

Denmark entered a period dominated by economic laissez-faire thinking in the middle of the nineteenth century; for example, it abolished guilds in 1857. The Constitutional Act of 1849 ended outdoor support and denied rights to able-bodied, workhouse inhabitants; yet it simultaneously created social rights to public support for those who were unable to support themselves (Petersen, Petersen and Christiansen Reference Petersen, Petersen and Christiansen2010, 70–2). No significant anti-poverty legislation was enacted apart from the constitutional reform. Yet despite the ruling liberal ideology, strong societal movements, such as the Danish folk high school movement, sought to sustain high levels of social investment in poor workers to combat poverty at the municipal level and to preserve collective strands in society (Petersen, Petersen and Christiansen Reference Petersen, Petersen and Christiansen2010, 79–80). Authors inspired local communities to engage in self-help activities. In 1838, Nikolai Frederik Severin Grundtvig offered poverty as a metaphor for individualism threatening collectivism: ‘the impoverishment of the individual heart and spirit for those who have forgotten the collectivism of the golden age’ (Grundtvig Reference Grundtvig1904–9, 122–5).

In the late nineteenth century, Denmark encountered competitive world markets, social problems associated with industrialization, expanding skills requirements and industrial conflict associated with labor market liberalization (Gourevitch Reference Gourevitch1986). Yet the political realm was deeply dysfunctional due to a stalemate between the Right Party (which controlled the executive and upper house of parliament) and Left Party (which controlled the lower house). When he was unable to gain parliamentary approval for his finance policies, Prime Minister Jacob Estrup imposed provisional budgets. The Left Party refused to address most measures, so virtually no significant legislation was passed from 1875 until the early 1890s (Henrichsen Reference Henrichsen1911, 67–72). Finally, parties collaborated on comprehensive solutions to social problems and universalism, starting with the 1892 Old Age Pension and culminating with the 1907 Unemployment Act (Petersen, Petersen and Christiansen Reference Petersen, Petersen and Christiansen2010, 81–2).

Two interrelated networks of authors worked to advance social and democratic reforms on the public agenda. Led by literary critic Georg Brandes and Edvard Brandes (writer and future finance minister), Modern Breakthrough (or free-thinking) authors attacked the earlier generation's romanticization of working-class lives with a new realism that starkly depicted social problems (Skovgaard-Petersen Reference Skovgaard-Petersen1976). Another group of authors (Holger Drachmann, Jakob Knudsen, Henrik Pontoppidan and Johan Skjoldborg) was associated with the folkloric movement and the folk high school movement inspired by Grundtvig (Coe 27).

These authors framed poverty in specific ways that anticipated later social democratic welfare state assumptions. They linked poverty to inadequate social investment in skills, viewed industrialization as an opportunity for growth, and emphasized connections between growth and social protections (Skovgaard-Petersen Reference Skovgaard-Petersen1976, 11–12). They offered favorable portrayals of workers as a class and moved away from the distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor. Thus Nobel prize winner Henrik Pontoppidan's Lucky Per conveyed appreciation for industrialism, sympathy for workers harmed by industry, a benign view of unions, and education and social protections as the best means of offsetting industrial risk. For Per, ‘It struck him what a fresh and active sympathy the workmen manifested from the beginning, although most came out of Copenhagen's lower classes…They did not quarrel with anyone and were held together by mutual respect’ (Pontoppidan Reference Pontoppidan2010[1898], 480). Per's fiancé, Jacobe, founded a school that would become ‘a sanctuary, a refuge…the children will also be given the capital for a bright and fruitful sense of life that they can later draw upon’ (477–8).

Authors emphasized that poverty detracted from society and social peace, as is captured in Holger Drachmann's play, ‘There Once Was’, the most performed play in Danish history. The male lead tells his wife that ‘the little people must bear life's burdens together’ (72). The final song, ‘We love our land’, sung every year on the summer solstice, is an ode to the strength of Danish community, love of peace, and commitment to defense against external enemies and internal discontent (Drachmann Reference Drachmann1902, 121). Modernists regarded state institutions more favorably than their British counterparts (Skilton Reference Skilton, Hertel and Kristensen1980, 37–43); while appreciating the importance of private community action, they pointed to the pitfalls of the private system. Thus Jakob Knudsen (Reference Knudsen1901) in The Old Priest wrote about the corruption associated with funding a new private Folk High School and the need for oversight to protect against violation of the social bonds.

The dysfunctionality of the political realm meant that cultural politics played a pivotal role; writers considered literature to be the best venue for political change (Frederiksen Reference Frederiksen2020, 65–6.) Viktor Pingel, leader of the student society movement and a close associate of Georg Brandes, noted that the struggle for democracy in Denmark was very much along cultural lines (Skovgaard-Petersen Reference Skovgaard-Petersen1976, 135). Fiction writers became directly involved as activists in the fight against Estrup in November 1878, by developing their own faction of the Left Party, entitled the ‘literary Left’ (or European Left), to elevate literary perspectives in social debates (Hvidt Reference Hvidt2017, 122–8). Edvard wrote to his brother in 1877 that the problem was not simply Right Party strength but Left Party weakness, and advocated co-operation with the farmer wing of the Left (Sevaldsen 1974, 235–8).

Authors worked closely with Left Party politicians, such as Viggo Hørup (who founded Politikken with Edvard Brandes), to sway public opinion on social rights, education and religion (Frederiksen Reference Frederiksen2020, 70–1,114, 166–7). The Literary Left also helped the Left Party forge a new ideological platform that was crucial to the battle for constitutional reform. As Left Party leader Christian Berg noted, ‘As long as the other had all the intelligence, it was a hopeless case to make people understand that the true opinion was on our side.’ But with the help of the Literary Left, ‘We waged war with culture more than with the party.’ The Literary Left constituted, ‘our poets, our professors, our jurists, journalists…Like manna from heaven, the literary Left came down into this desert…we had what we lacked’ (Hvidt Reference Hvidt2017, 127–8.) The alliance between the literary and peasant factions disintegrated in 1884, when the peasant wing formed an alliance with the moderates within the Left Party. Yet the faction later became the highly influential Radical Left Party that was extremely important to the origins of the welfare state (Henrichsen Reference Henrichsen1911, 96).

Finally, authors helped facilitate links between farmers in the Left Party and workers in the Social Democratic Party. Evangelical farmers and urban workers had little contact and a strong cultural disconnect. Yet the authors and intellectuals communicated with both groups, and writers played an important role in facilitating connections in advance of democratic change in 1901. The common ground between workers and farmers, which became one of the hallmarks of the social democratic system, helped pave the way for the 1907 Unemployment Insurance Act. The act embraced principles of voluntarism and state subsidies for funds. This enabled the continuation of private initiatives from unions, rural co-operative self-help movements and insurance pooling. Thus the 1907 act benefitted both urban and rural workers and strengthened the political coalition at the heart of the social democratic model.

Britain

In 1800, Britain encountered rising problems of poverty, as the enclosure movement (turning agricultural workers into wage laborers), growing industrialization and urbanization destabilized society (Doheny Reference Doheny1991, 335). Yet unlike Denmark, Britain produced limited welfare innovation (apart from the small Relief of Poor Law Act of 1782) and largely left the 1601 Poor Law in place until the new Poor Law of 1834. Whereas Denmark expanded municipal responsibility for job provision and social investments, few British municipalities adopted the Speenhamland system or developed public jobs; public poor relief remained limited and punitive and private, or church philanthropists added to public programs (Block and Somers Reference Block and Sommers2014, 127–34). Thereafter, the new poor law of 1834 reaffirmed the most punitive impulses of the 1601 act; the able-bodied poor could only receive support in prison-like workhouses.

The Danish celebration of the peasant found no analogue in Britain. Eighteenth-century novelists largely ignored the working class or treated them humorously. Defoe wrote extensively about religious freedom and individual responsibility, but paid scant attention to poverty or societal concerns (Marshall Reference Marshall2007, 556, 561). In Robinson Crusoe (1721), the title character lives outside of society for a quarter century; commercial capitalism and slave trading allow him to become a wealthy man (28).

At century's end, writers in the conservative (Burke, Trimmer) and radical (Godwin, Wollstonecraft, Shelley) camps held opposing views of the French Revolution; yet neither side paid much attention to working-class poverty. Thomas Malthus’ Essay on the Principle of Population (1797) did much to set perceptions of the poor. Malthus believed the population would increase with a rise in the means of subsistence unless population growth was limited by checks such as moral restraint (late marriage), vice (prostitution) and misery (starvation) (Malthus Reference Malthus1809, 27–8). Therefore, poor support would only exacerbate poverty. While critics denounced Malthusian pessimism, there was a strange convergence of the left and right on concerns about overpopulation and excessive reproduction among the lower classes. Denmark and Norway each had a lower population density than Britain in 1800, and the Danish government sought to increase population growth. Yet Malthus attributed Norway's (then part of Denmark) density to positive policy (later marriage rates) rather than higher mortality; he was impressed that Norwegians (alone in the world) had thought through the problems of surplus labor and were more concerned about the happiness of the working class than elsewhere (Malthus Reference Malthus1809, 326).

Authors who did write about poverty framed it in ways that resonated with the assumptions of Britain's liberal welfare state regime. They linked poverty relief to charity for suffering individuals (usually from the upper and middle classes) rather than for social investments in skills, differentiated between the deserving and undeserving poor, and expected private philanthropy to augment state efforts. Gripping stories described gentry forced into declined circumstances and women suffering from profligate male misbehavior, such as Mary Wollstonecraft's (Reference Wollstonecraft1798) title character in Maria and the Wrongs of Women. Samuel Richardson's Pamela concerns a gentleman's family that has fallen into poverty. Pamela's virtuous defense against the untoward advances of her master is offered as exemplary behavior on the part of the poor, as Pamela is ‘bred to be more ashamed of dishonesty than poverty’ (Richardson 1740_388–1,169, 1,179). Pamela transforms her master from monster to husband and inspires a spirit of charity among her new upper-class associates.

Instead of linking poverty to a lack of social investment in education, many British elites feared that mass literacy would threaten social stability (Brantlinger Reference Brantlinger1998). Coleridge recognized that some schooling for the poor could limit alcoholism (Coleridge Reference Coleridge and Griggs1956[1796]). Yet Wordsworth was much more pessimistic about educating the poor; in a letter to Francis Wrangham, he rejected a state system of national education and argued that schooling should concentrate on those at the top and then filter down (Knight Reference Knight1907, 180).

Authors viewed poverty as under government jurisdiction, yet private Christian charity should augment public benefits and benefits should be kept low so as not to fan Malthusian tendencies toward overpopulation. Radical Jeremy Bentham conceptualized a National Charity Company funded by a poor tax to give some benefits to the deserving poor and send the undeserving poor to workhouses (Bentham Reference Bentham and Quinn2010). In 1787, Sarah Trimmer advocated for Houses of Industry for the able-bodied poor, and even sought residential schools where five-year-old girls could learn spinning, etc. The schools would attract young gentlewomen benefactors and eliminate the need for government funding (Trimmer Reference Trimmer1801, 69–70). Mary Shelley's monster in Frankenstein longs for wife and hearth; yet his creator fears that the monster's progeny would threaten mankind. Malthusian overpopulation became a powerful literary meme even for those such as Charles Dickens who are sympathetic to the working class (Steinlight Reference Steinlight2018, 7–8, 22).

The New Poor Law of 1834, which reduced poor taxes, ended outdoor relief and expanded prison-like poor houses, was a product of Whigs on the left, such as Lord Brougham. Some Tories such as Wordsworth opposed the law, sensing that curbs on almsgiving would reduce opportunities for Christian charity (for example, as in the poem ‘The Old Cumberland Beggar’) (Chandler Reference Chandler1980, 756). Yet the surprising feature of the law was how much convergence there was on this punitive approach and how the left led the vanguard against outside poor support.

The late nineteenth-century decline of British industry and rising structural employment amplified attention to working-class misery, social strife and skills deficits (Williams 1896, 1). Britain responded with the National Insurance Act of 1911 that created health insurance and a tiny, compulsory unemployment insurance. The pilot unemployment insurance program represented a small break with the past by acknowledging structural unemployment; however, protections were limited, no labor exchanges facilitated employment and most poor continued to be served through means-tested social assistance (Gough et al. Reference Gough1997; Foerster Reference Foerster1912, 300–304; Shepard Reference Shepard1912, 232–4). Thus, the act followed Britain's history of social innovation: support entailed an individual minimum rather than a societal maximum, and state power controlled individual malfeasance rather than provided jobs (Harris Reference Harris1992, 119).

After the passage of the 1834 law, Victorian social reform novelists (such as Charles Kingsley, Charles Dickens and Elizabeth Gaskell) depicted the punishing lives of the poor with realistic, heart-rending portrayals of individual suffering; yet they stopped short of more systemic views. Victorian writers reinforced political attention to the agonizing conditions of women and children, railed against child labor, celebrated charitable sentiments and anticipated the pillars of the later liberal welfare state model: the differentiation of classes of the poor and a reliance on charity. Dickens greatly resented Malthusian descriptions of the poor and grieved for poor children (Hughes Reference Hughes1903, 1), yet even he neglected the problem of the lack of skills for society. Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol to attack the report of the Second Children's Employment Commission and bragged about his literary power when he told commission member Southwood Smith that his book would have ‘twenty thousands time the force’ of a pamphlet on child labor (Henderson Reference Henderson2000, 145).

Later writers linked poverty to structural risks associated with capitalism and globalization (Crosthwaite 336–7). Writers and policy makers in the TH Green network were inspired by the earlier social justice novels of Kingsley and Dickens, but also viewed poverty as a systemic problem. The Fabian Society drew socially concerned fiction and nonfiction writers from the upper and middle classes such as Sidney and Beatrice Webb, George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells and Bertrand Russell.

Yet despite growing concerns about structural unemployment, even these authors framed poverty in ways that resonated with the liberal welfare regime, drawing distinctions between the deserving and undeserving poor and depicting a culture of poverty. In George Gissing's The Netherworld, most of the poor descend into lives of drunken squalor. Fabian Bernard Shaw (Reference Shaw2017[1913], 45) poked fun at the culture of poverty in Pygmalion: ‘Undeserving poverty is my line….it's the only one that has any ginger in it’. Yet even Fabians shared Malthusian concerns about overpopulation, cultural degradation and the gene pool. Wells refers to the ‘extravagant swarm of new births’ as the ‘essential disaster of the nineteenth century’ (Carey Reference Carey1992, 1). In The Time Machine (1898), Wells imagines an out-of-control underworld population that preys on the upper-world inhabitants (Wells1898, Loc 500).

Fighting poverty was a way for young idealists to nurture their finer impulses. Mary Augusta Ward's eponymous Robert Elsmere (1888) evolves from a country parson to a social activist who has ‘gone mad’ with a new religion: ‘Dirt, drains, and Darwin’ (Ward 3,189). Hardy's biographer, Michael Millgate (Reference Millgate2004, 88–9), describes Hardy's long-term goals as ‘self-education, self-development and self-discovery’ (Millgate Reference Millgate2004, 100). The concept of social rights evolved during this period. George Gissing's Denzil Quarrier (1892_262–109) articulated an individual right to social support: ‘if I found myself penniless in the streets …It would be the duty of society to provide me with [social support].…as civilized beings we have rights’.

Fabians diverged from past anti-poverty measures: the Webbs highlighted structural unemployment and proposed labor exchange and training in the Minority report, yet they retained a major role for private charity (Webb Reference Webb1909, 199, 208). They met repeatedly with Winston Churchill in advance of the 1911 National Insurance Act (Webb Reference Webb1909). Moreover, Gilbert (Reference Gilbert1976, 1,058–60) suggests that the act's limitations reflected Lloyd George's interest in protecting the City of London from excessive social reforms. Yet even the Fabians reinforced limitations of the liberal welfare state in seeking conditional relief to improve the character of the poor. The act was very British in that the state could only use its power to relieve the distress of suffering individuals (Gilbert Reference Gilbert1976, 855–61).

France

The failure of the Protestant Reformation allowed the Catholic Church to remain the primary agent for social protection in France (which had no poor law until the late nineteenth century). The Catholic Church provided poor support and charged its flock with a moral duty to provide alms (Geremek Reference Geremek1997; Gutton Reference Gutton1974). In 1724, the French king provided minimal financing for general hospitals to hold beggars and vagrants, but most of these institutions remained privately run under Church control (Castel Reference Castel1995; Gutton Reference Gutton1974; Schwartz Reference Schwartz1988). Some attempts were made to provide public outdoor relief during the French Revolution (Hudemann-Simon Reference Hudemann-Simon1997, 19–20), yet the social assistance system remained complex, underdeveloped, and reliant on religious and private financing (Castel Reference Castel1995, 374; Dessertine et Faure Reference Dessertine, Faure, André and Pierre1992). Furthermore, in the wake of the French Revolution, the political (rather than the welfare) regime claimed political attention, and poverty was largely left off of the agenda.

Throughout the eighteenth century, writers depicted the poor as akin to the ‘noble savage’ (bon sauvage) or deserving innocents with few resources, who are neither lazy nor eager for excessive wealth. In Rousseau's famous novels Julie ou La Nouvelle Héloïse (1761) and Emile ou De l’éducation (1762), relatively poor, rural people claim a moral advantage over the urban rich: ‘having always lived a uniform and simple life, I have kept in my spirit all the clarity of primitive lights…my poverty was moving away the temptations that dictate the sophisms of vice’ (Rousseau L'Emile 1762_23–29). These positive depictions of the poor reinforced leaving poverty off the political agenda and charitable support for paupers to the Church.

No French bestsellers in the early nineteenth century centrally addressed poverty (see Lyons Reference Lyons1987). Instead, two groups of widely read authors were important in focusing attention on other issues. First, religious novels and stories were hugely popular. Thus La Fontaine's Fables (1668) and Fénélon's Télémaque (1699), although written in the seventeenth century, continued to command the highest readership by extorting the importance of moral and religious education for the individual. Secondly, Enlightenment authors (such as Voltaire and Rousseau) were widely read in the nineteenth century; yet they discoursed on the political regime (the revolution's legitimacy and the best political institutions) and neglected poverty as a political issue. Their works addressed civil and political citizenship rather than social citizenship. Writers’ absence of attention to the poverty issue was met with a lack of public intervention.

The landscape shifted around 1840–50, when the literary movements of Romanticism and Realism gave birth to hugely successful social novels (romans sociaux). Eugène Sue's best-selling Les mystères de Paris (1842–1843) explored the lowest classes of society in Paris and put poverty on the agenda from a qualified socialist perspective. Sue was very engaged politically and was elected in 1850, after the 1848 revolution, as a socialist Republican deputy. During this period, Republicans sought ‘national workshops’ (ateliers nationaux), public assistance and a right to work. Yet conservatives, liberals, monarchists and the Church eventually barred state intervention (Renard Reference Renard1986).

The other very important figure at the time was Victor Hugo. Hugo's famous social novels paid great attention to working-class poverty and depict the poor with both positive and negative connotations. Initially, he pictured the Church as the appropriate agent of poor relief and the state as a repressive rather than ameliorating force. His Quasimodo in Notre Dame de Paris (1831) is an orphan hunchback who deserves relief provided by the Church, that is, Frollo, priest and archdeacon of Notre Dame de Paris. Hugo was at the time still a Conservative, and was even elected to Parliament in 1848. Yet, after his initial social novels, he directly addressed poverty in his Discours sur la misère (Discourse on poverty), which he presented in Parliament in 1849. The discourse did not produce reforms, and after the coup d’état in 1851, Emperor Napoléon III rejected proposals to develop public assistance programs. With the birth of the Second Empire, both Eugène Sue and Victor Hugo went into exile, and censorship associated with the regime led to a depoliticization of novels (Lyons Reference Lyons1987).

Social novels remained quite popular, however, especially when the Third Republic replaced the Second Empire after 1870. Victor Hugo remained very influential during his exile. His famous Les Misérables (1862) put poverty at the center of the novel. The expression ‘les misérables’ means both the poor and the despicable in French, and Hugo's characters included both the poor and despicable Thénardier and the poor but noble Jean Valjean. Valjean struggles to help the poor, but is hounded by Javert, policeman and representative of state authority, who represses rather than assists unfortunate characters in the novel.

With the fall of Napoléon III and the birth of the Third Republic, anti-clerical Republicans triumphed over clerical Monarchists and finally progressively shifted the balance of political life between church and state (Manow and Palier Reference Manow, Palier, Van Kersbergen and Manow2009). French authors during this period contributed to the Republican cause by stressing the structural nature of poverty under conditions of expanding social protections; yet they continued to depict state intervention with some degree of skepticism. The most famous author at the time was Emile Zola. Although he was very politically engaged in favor of the Republic, unlike Sue and Hugo, Zola never ran for office. However, through his famous social novels as well as his journalism, he had great influence at the time, shaping the political debate.

Zola's novel Germinal (1885), for instance, describes the difficult life of miners in Northern France. Etienne falls into poverty after losing his job, becomes a miner and then leads the workers' strike against the company. The novel's message is that involuntary unemployment associated with economic transformation pushes the able-bodied into poverty, and labor activism is appropriate (Sassier Reference Sassier1990). By helping to put poverty on the agenda, Zola fueled the Republican coalition that eventually led to the ‘laicization’ of social assistance, which occurred with laws passed in 1893, 1905 and 1913 (Renard Reference Renard1986, 22). Yet the Church continued to provide benefits parallel to growing public protections against social risks (Dessertine and Faure Reference Dessertine, Faure, André and Pierre1992; Renard Reference Renard1986). Republicans sought a strong role for the central state, while traditionalists preferred delivery by the Church and family; the fragmented system of social welfare provided by municipalities constituted a compromise (Renard Reference Renard1986). The fragmented public system was reinforced in 1930, but compulsory unemployment insurance developed only in 1958 (Daniel and Tuchszirer Reference Daniel and Tuchszirer1999; Hatzfeld Reference Hatzfeld1971). Indeed, despite the demand for social protection, even Republicans did not always perceive the state positively, as is obvious with Zola's life. In Germinal, the working class must defend itself against the state, which violently represses the strikes (Radé Reference Radé2015), and Zola was himself forced to leave France due to his engagement in favor of Dreyfus in his article ‘J'accuse!’

Conclusion

The distinctions among modern welfare regimes have deep historical roots. While similar policy ideas and socio-economic challenges motivated British, Danish and French policy makers to fight poverty through the ages, early anti-poverty experiments anticipated modern welfare state regimes’ different approaches to the goals, beneficiaries and agents of social programs. Denmark featured a strong role for social investment in anti-poverty programs as early as the eighteenth century, when local governments were charged with providing work to the able bodied. The British state assumed responsibility for controlling the poor, but interventions remained minimal and punitive. The Church largely retained control over poor support in France until the late nineteenth century, and government programs continue to be supplemented by non-state actors. Moral education rather than skills development was the primary object of concern.

We suggest that countries' specific responses were mediated, at least in part, by the mobilization of cultural actors and artifacts. Cultural actors, acting as avant garde activists, helped to put new concerns about poverty on the political agenda. Writers framed policy problems and solutions with culturally-specific references to the goals, beneficiaries and agents of the welfare state. Writers were particularly important to the popularization of, mobilization of support for, and legitimation of specific policy solutions to poverty problems. Their political allies credited them with having an impact on welfare state trajectories. Authors were influenced in this framing by their inherited cultural tropes (the cultural constraint) but reworked and updated these touchstones to address changing socio-economic conditions and hegemonic ideas about poverty reduction. Thus fiction writers grappled with the dialectical tension between sustaining cultural and institutional continuities, even while facilitating change in the cultural narrative.

We use quantitative computational linguistic methods to document significant cross-national differences in the language of poverty within large corpora of British, Danish and French literature dating back to 1700. By the eighteenth century, Danish writers were already discussing poverty with references to skills and society; British writers referenced charitable interventions for vulnerable individuals (especially women and children). Both countries included many references to government. French authors made few references to government, but frequently mentioned words associated with individualism, religion and charity.

These findings have ramifications for the study of welfare states. For example, a deep commitment to building a strong society, rather than redistribution for equality, dates back to the early 1700s in the Danish social democratic state, which helps us understand the modern social democratic emphasis on social investment policies. While scholars debate whether challenges associated with globalization and deindustrialization are bringing about a convergence among welfare states, the persistence of nationally specific themes in depictions of poverty through the eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth centuries may indicate some consistency in future policy trajectories (Palier Reference Palier2010).

Our work also has implications for the study of culture and politics. Scholars recognize that cultural values are associated with modern cross-national distinctions in welfare programs (Svallfors Reference Svallfors1997), yet pinpointing the historical contributions of culture has been more elusive. We fill this gap with our empirical analysis of the cultural constraint within British, Danish and French literature, and document both cultural continuities over time and cultural differences across nations in depictions of poverty. Writers act collectively to rework imaginaries about poverty for new challenges at each age of social innovation.

Supplementary material

Online appendices are available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000016.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to Ben Getschell and Andrei Lapets for their programming assistance and to HathiTrust and Arkiv af Dansk Litteratur for files. We thank Rob Johns and our anonymous reviewers for their superb guidance, as well as Karen Anderson, Jens Beckert, Suzanne Berger, Taylor Boas, Patrick Emmenegger, Patrick Fessenbecker, Torben Iversen, Des King, Tim Knudsen, Sebastian Kohl, Niki Lacy, Michele Lamont, Julie Lynch, Anne-Marie Mai, Eileen McDonagh, Jim Milkey, Elisabeth Møller, Thomas Pastor, Klaus Petersen, David Soskice, Kathy Thelen, Pieter Vanhuysse, and Margaret Weir. We also thank members of seminar series at Harvard Center for European Studies State and Capitalism working group, St. Gallen University, Danish Center for Social Science Research at Southern Denmark University, SDU working paper series, Third Nordic Challenges Conference at Copenhagen Business School, Max Planck Institute, Yonsei University, American Political Science Association and Council for European Studies.

Financial support

Tom Chevalier thanks the Harvard Center for European Studies for offering a research stay through the German Kennedy Memorial Fellowship. Cathie Martin thanks for their generous funding the National Endowment for the Humanities (Grant #20200128124651855), Boston University Hariri Institute (Research Award #2016-03-008), and Boston University Center for the Humanities.