The recent literature on comparative authoritarianism has taken what Pepinsky (Reference Pepinsky2014) refers to as an ‘institutional turn’. Autocratic leaders have been found to commonly adopt political institutions, such as ruling parties, in order to stay in power (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2010; Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008; Gandhi and Przeworski Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2007; Geddes Reference Geddes1999b; Greene Reference Greene2007; Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010; Lust-Okar Reference Lust-Okar2006; Malesky and Schuler Reference Malesky and Schuler2010; Slater Reference Slater2010). Scholars argue that parties are valuable institutions because they are particularly well suited to manage intra-elite conflict and allow dictators to make credible inter-temporal power-sharing deals (Boix and Svolik Reference Boix and Svolik2013; Brownlee Reference Brownlee2007; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2008; Reuter Reference Reuter2017; Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Regimes led by single or dominant parties are believed to be especially resilient. Despite this implicit emphasis on the importance of strong parties, the literature on comparative authoritarianism has not developed systematic ways in which to evaluate the institutional strength of autocratic parties. As a result, it is not clear how often ruling parties are actually strong and capable of carrying out these important functions.

This article strives to put the comparative literature on authoritarian parties on more solid empirical foundations. In doing so, I show that strong ruling parties are much rarer than we currently think. I argue that strong parties require established rules, procedures and hierarchies that shape the distribution of power and resources among elites. The institutionalization of these structures de-personalizes the ways in which the organization is run. When parties are transformed into autonomous organizations, they can function regardless of who is in power. Since institutions are especially prone to predation by leaders in autocratic settings, ruling parties are strengthened when rules and procedures guaranteeing the organization's autonomous existence are put into place. A strong autocratic party is one that can perpetuate itself beyond the lifespan of a single leader.

I show that when we define autocratic party strength in this way, strong ruling parties are much rarer than is typically assumed. By examining leadership changes in all non-democratic states from 1946 to 2008, I find that most ruling parties are unable to survive multiple leadership transitions: 57 per cent of all ruling parties fail to survive more than a year after the first leader's death or departure from power. Even conditioning on cases in which the first leader experienced a non-violent exit from power, 52 per cent of ruling parties do not survive the peaceful departure of the founding leader. Furthermore, 32 per cent of ruling parties that are coded as leading single-party regimes fail to survive a year past the departure of the first leader. In sum, these findings challenge the notion that most ruling parties are capable of enforcing inter-temporal promises, because the existence of many parties seems to rely heavily on the influence of a single leader. While strong parties may be key to durable authoritarianism, relatively few parties are truly strong.

A key implication of this study is that scholars may be generating broader theories of party dictatorships based on the experiences of a small number of parties, such as the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) in Mexico or the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Yet as this article demonstrates, a closer look reveals that these cases represent outliers, rather than the typical ruling party. The ways in which ruling party strength is conceptualized and operationalized affect our understanding of the distribution of strong parties across autocratic regimes as well as the accuracy of empirical tests that use quantitative proxies of institutional strength in dictatorships. Instead, this article advocates more nuanced measures that better reflect the bureaucratization of ruling parties, ideally moving beyond the use of discrete regime types.

Conceptualizing Ruling Party Strength

A key argument that has emerged in the literature on authoritarian regimes is that ruling partiesFootnote 1 play a critical role in maintaining and promoting autocratic regime stability. Ruling parties can control and contain elite conflict, thus providing an institutional channel through which members of the ruling coalition can maintain power (Brownlee Reference Brownlee2007; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006; Reuter Reference Reuter2017; Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Parties can also funnel state benefits to elites (Greene Reference Greene2007; Slater Reference Slater2010) or help to co-opt opposition groups (Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008; Lust-Okar Reference Lust-Okar2007). On the mass level, parties can monitor citizens and provide patronage to social groups (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2010; Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010) or gather information for the regime (Malesky and Schuler Reference Malesky and Schuler2010).

However, not all ruling parties are capable of achieving these important aims; the functionalist literature on authoritarian institutions often overlooks this point. Many ruling parties are quite weak and lack the institutional infrastructure, rules and organizational autonomy required to carry out the necessary functions of elite management, rent distribution, co-optation and monitoring. The Mouvement Populaire de la Revolution (MPR) under the rule of Mobutu Sese Seko in Zaire, for example, lacked institutionalized rules and served only to amplify the ruler's arbitrary power during his twenty-eight-year tenure. The MPR manifesto declared that the party ‘will adhere to the political policy of the Chief of the State and not the reverse’. Mobutu used the party as a mouthpiece for this rhetoric, and the MPR disintegrated upon his death (Jackson and Rosberg Reference Jackson and Rosberg1982).

How should ruling party strength be assessed? I argue that, within autocracies, party institutionalization should be considered a critical component of ruling party strength. Party institutionalization is defined as the creation of hierarchical positions and the implementation of rules and procedures that structure the distribution of power and resources within the ruling coalition. Importantly, the creation of such rules and procedures depersonalizes the ways in which the party organization is run by constraining the leader's ability to make arbitrary decisions in the future. Institutionalized ruling parties are autonomous organizations, capable of functioning regardless of which leader is in power.

This focus on organizational autonomy is of particular importance in autocratic settings because one of the key features of authoritarian states is that power is concentrated in the hands of a small group of elites – and often a single leader. Since institutions are especially prone to predation by autocratic leaders, rules, procedures and structures that promote organizational autonomy result in institutional durability. Critical characteristics of the quality of parties in autocratic regimes include the extent to which there are structures and procedures in place to guard against personalist rule and maintain the survival of the party organization. In autocratic settings, a strong ruling party is one that can perpetuate its own existence, beyond the influence of individual leaders.

Importantly, this organizational permanence is a necessary condition if ruling parties are to serve an inter-temporal commitment function. Though autocratic parties often perform multiple regime-stabilizing functions, scholars have stressed that a key purpose of ruling parties is to act as inter-temporal commitment devices that help manage elite conflict (Boix and Svolik Reference Boix and Svolik2013; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2008; Reuter Reference Reuter2017; Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Elites are willing to support a ruling party only if they believe that they will continue to receive a steady stream of benefits and political appointments. For ruling parties to truly serve this commitment function, the party must remain in power for multiple periods and survive leadership changes. As Magaloni highlights, the credibility of power-sharing deals between the leader and party elites ‘crucially depends on the party's ability to effectively control access to political positions and on the fact that the party can be expected to last into the future’ (Magaloni Reference Magaloni2008, 2, emphasis added).

My conceptualization builds on existing scholarship of party institutionalization and strength.Footnote 2 Huntington provided an early conceptualization of party institutionalization as the process through which parties become established and acquire value and stability. In particular, he argued that adaptability and the ability to outlive the founder are key characteristics of a durable organization. An institutionalized party is one that has the ability to exist independently of particular actors. An organization that is merely an instrument of a leader is not an institutionalized party (Huntington Reference Huntington1968, 12–20). As Panebianco notes, ‘Institutionalization entails a “routinization of charisma”, a transfer of authority from the leader to the party’, and very few charismatic parties survive this transfer (Panebianco Reference Panebianco1988, 53).

Other scholars have focused on the aspect of ‘value infusion’, a process through which ‘actors’ goals shift from the pursuit of particular objectives through an organization to the goal of perpetuating the organization’ (Levitsky Reference Levitsky1998, 79; see also Selznick 1957; Selznick and Broom 1955). Levitsky adds an additional dimension of ‘behavioral routinization’ to this concept, noting that ‘[i]nstitutionalization is a process by which actors’ expectations are stabilized around rules and practices…The entrenchment of “rules of the game” tend to narrow actors’ behavioral options by raising the social, psychic, or material costs of breaking those rules’ (Levitsky Reference Levitsky1998, 80). An institutionalized party ‘is one that is reified in the public mind so that ‘the party’ exists as a social organization apart from its momentary leaders’ (Janda Reference Janda1980, 19). Similarly, Levitsky and Murillo (Reference Levitsky and Murillo2009) argue that strong parties are organizations that are stable in that they must survive ‘not only the passage of time but also changes in the conditions – i.e., underlying power and preference distributions – under which they were initially created’ (117, emphasis added).

It is important to note that most prior studies on party institutionalization focus on parties in democratic systems. Despite differences in regime type, much of the conceptualization of democratic party institutionalization can be applied to analyses of authoritarian ruling party strength. Yet there is one important difference: the effect of what Slater (Reference Slater2003) terms ‘infrastructural power’ in promoting the institutionalization of democratic versus authoritarian ruling parties. Scholars of democratic party institutionalization often stress the importance of parties that can build ‘roots in society’ with functioning local branches that raise revenue and establish the party's presence outside of the capital (Mainwaring and Scully Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995). Yet as Slater (Reference Slater2003) argues, such infrastructural capabilities can lead to the personalization of power if there are no effective constraints on the leader. If, for instance, an autocratic leader has absolute control over a ruling party that has broad control over state and society, the leader can simply use the party to shut out potential regime challengers or to persecute potential opposition in civil society without being constrained by his own party elites. In an autocratic context, pervasive roots in society without effective executive constraints can lead to personalized forms of dictatorship.

Therefore in authoritarian regimes, ruling party strength hinges critically on the creation of elite-level rules and procedures that structure the distribution of power and resources between the leader and elites. This emphasis on elite-level institutionalization does not necessarily exclude other possible dimensions of party strength. I stress here that organizational autonomy is a baseline minimal condition that a ruling party must meet in order for it to possibly be considered a strong and durable organization. At the very least, a strong ruling party must have the ability to survive and function as an independent organization. It is not the only component of a strong party, but it is a fundamental one. Although this criterion sounds simple, most ruling parties fail this litmus test. As the data below will show, most ruling parties are unable to survive leadership transitions.

Operationalizing Ruling Party Strength: Problems With Existing Approaches

Developing high-quality cross-national indicators of authoritarian institutions poses some real challenges. Dictatorships are frequently closed off, and restrict or completely eliminate access to reliable and accurate information. Moreover, conventional measures of institutional strength in democracies simply cannot be imported to autocracies due to the lack of free and fair political competition. For example, while electoral results from presidential or legislative elections can serve as credible measures of incumbent or party strength in democracies, the same approach cannot be reliably applied in autocracies because election results are often either falsified or do not reflect citizens’ true preferences.

In light of these data challenges, perhaps the most common dataset that researchers have used as a proxy for ruling party strength is regime typology data. In a seminal study, Geddes (Reference Geddes1999a) classifies all autocratic regimes into one of the following types: military, single-party (sometimes referred to as dominant-party or party-based regimes), personalist or hybrids of these categories. These classifications are based on whether control over ‘policy, leadership selection, and the security apparatus is in the hands of a ruling party (dominant-party dictatorships), a royal family (monarchy), the military (rule by the military institution), or a narrow group centered around an individual dictator (personalist dictatorship)’ (Geddes, Wright and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014, 318).

Single-party regimes are defined as those in which the ‘party has some influence over policy, controls most access to political power and government jobs, and has functioning local-level organizations’ (Geddes, Wright and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014, codebook, 31). By contrast, in personalist regimes, ‘access to office and the fruits of office depend much more on the discretion of an individual leader. The leader may be an officer and may have created a party to support himself, but neither the military nor that party exercises independent decision-making power insulated from the whims of the ruler’ (Geddes, Wright and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014, codebook, 7). Regimes coded as primarily military mostly seem to reflect the absence of a ruling party (though this is not explicitly discussed). In other words, ruling parties that are coded as part of a single-party regime are implicitly considered strong parties.

Geddes’ study and associated datasets have made immense contributions to scholarship on authoritarian politics. It was one of the first studies to codify differences in the institutional makeup of dictatorships. It renewed interest in the study of non-democratic regimes outside the industrialized world and stimulated a large body of recent work on the policies, institutions and consequences of autocratic rule.Footnote 3 However, I argue that regime typologies serve as a poor indicator of ruling party strength due to the aggregate nature of the scoring mechanism. As a result, this measurement problem biases our substantive understanding of the distribution of strong parties across all autocratic regimes.

Since regime typologies are composite indices that aggregate various dimensions of leaders, institutions and military structures into a single category, it is difficult to isolate cases where the ruling party is strong.Footnote 4 Ruling parties can appear to be resilient for a number of reasons unrelated to the strength of the organization itself. The regime, for instance, can benefit from an abundance of natural resources, a charismatic leader or external support (such as from the United States or the Soviet Union during the Cold War). Under these circumstances, a ruling party can remain in power for decades – especially if the founding leader is still in office. Yet these factors reveal very little about the party's underlying degree of institutionalization.

Without examining each individual dimension directly, it can be difficult to determine whether the regime appears strong because it has a strong leader or a strong party. Some regimes appear to be party based, when in fact the party is associated with a strong and charismatic leader who merely exploits the party as a personal vehicle to amplify his authority. Without separating party strength from leader strength, it can be unclear whether the primary source of resilience comes from the party or the leader.

Consider the following case. The Parti Democratique de Guinee (PDG) under the rule of Ahmed Sékou Touré in Guinea is coded as part of a single-party regime. Sékou Touré was a self-proclaimed socialist who portrayed Guinea as a one-party state. Yet the leader personally determined all national policies, and the PDG lacked institutionalized rules and permanent structures. The party was primarily used as a mouthpiece to promote Sékou Touré's ideology and policies, rather than as a forum for elite power sharing. Upon the leader's death, the military seized power in a coup and the PDG was immediately disbanded (Adamolekun Reference Adamolekun1976; Camara Reference Camara2005).

Leader strength and party strength are likely to be confounded within the regime typologies framework due to the way that countries were coded. In her 2003 book Geddes outlined a clear set of guidelines that she used to categorize regimes into different types (225–227). A list of questions was used to assess a country's fit with each regime type (single-party, military, and personalist). Countries were then sorted into regime types according to the following instructions:

Each regime used in the data analysis receives a score between zero and one for each regime type; this score is the sum of “yes” answers divided by the sum of both “yes and no” answers. A regime's classification into a nominal category depends on which score is significantly higher than the other two (Geddes Reference Geddes2003).Footnote 5

As the coding instructions describe, countries were assigned to regime categories based on an aggregate score of multiple criteria. This is problematic for attempts to separate leader strength from party strength due to the heterogeneous mix of questions within the single-party category: some criteria reflect ruling party strength, while others gauge the leader's influence and power.

For example, two criteria used to evaluate the single-party regime category include: ‘Does the party control access to high government office?’ and ‘Are members of the politburo (or its equivalent) chosen by routine party procedures?’ These questions clearly seek to capture the degree of organizational autonomy and the party's ability to function according to set rules. Regimes that score a ‘yes’ on these questions, such as the Soviet Union under the Communist Party or Singapore under the People's Action Party, are likely to have strong ruling parties.

By contrast, two other criteria used to evaluate the single-party regime category: ‘Did the first leader's successor hold, or does the leader's heir apparent hold, a high party position?’ and ‘Is party membership required for most government employment?’ do not reflect party strength. Regimes that score a ‘yes’ on these questions do not necessarily have parties that are institutionalized or organizationally autonomous. Many leaders appoint their cronies or supporters to prestigious party positions, which can be done without a meritocratic promotion structure within the party organization. Leaders also often require all government employees to be party members, but this does not necessarily reflect the institutionalization of the party organization itself.

For instance, in the Dominican Republic under Rafael Trujillo all adults were essentially required to be card-carrying members of the ruling Partido Dominicano (PD). The party was ‘synonymous with almost everyone in the country who was anyone. Membership was practically a routine procedure… No Dominican in public life, business, the professions, or the arts could survive outside the ranks’ (Crassweller Reference Crassweller1966, 99).Footnote 6 Yet the PD was founded and controlled entirely by Trujillo. He appointed all local-, provincial- and national-level party officials, and personally made all party-related decisions. The party in effect existed to amplify the leader's personal influence.

A country that only passes the first set of criteria (that reflects party strength) and a country that only passes the second set of criteria (that reflects leader strength) may both be placed in the same single-party category due to the aggregate nature of the scoring mechanism. Yet because it is unclear what the individual responses to these criteria were, scholars cannot differentiate between regimes with strong parties and those with weak parties (but strong leaders) within the single-party category. As a result, China under CCP rule and Mexico under PRI rule are placed in the same category as Guinea under the rule of Sékou Touré or Mali under the rule of Modibo Keita.Footnote 7

It is important to note that this critique does not necessarily focus on the discrete nature of regime typologies.Footnote 8 Scholars often make categorical distinctions between countries and regimes, with the understanding that discrete labels, such as democracy and dictatorship, may obscure some variation within categories. However, I argue that regimes with highly institutionalized parties and those with weak parties are currently lumped together under the same single-party category. This is highly problematic if scholars use this category as an indirect indicator of ruling party strength.

How Common Are Strong Ruling Parties?

This section presents evidence that parties with organizational autonomy are much rarer than is typically assumed. Importantly, I show that most ruling parties are unable to survive after the death or departure of the founding leader. This is true even of parties that are coded as leading single-party regimes or when we condition on peaceful leader exit. Ruling parties are very common – in fact, most leaders have them. Strong ruling parties, however, are much rarer.

Using data from Svolik (Reference Svolik2012), I identify a global sample of 156 ruling parties and the corresponding regime leader in power for all country-year observations that are coded as authoritarian from 1946–2008.Footnote 9 A few parties, such as the PRI in Mexico or the Communist Party in the Soviet Union, took power prior to 1946, so the variables for those parties are calculated from the time they took office.Footnote 10 For parties that were still in office in 2008, I updated the dataset to reflect the most accurate end date. For instance, the National Democratic Party was in power until 2011 in Egypt, and the Communist Party of Vietnam is still in power. The complete set of ruling parties is listed in Appendix Table 1.

Most authoritarian regimes have ruling parties. Out of 351 autocratic regimes (as defined by Geddes, Wright and Frantz (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014)) from 1946 to 2008, 63 per cent maintained a ruling party at some point, and only 12 per cent of regimes banned political parties the entire time the regime was in power. In fact, 46 per cent of regimes maintained a ruling party the entire time they were in power. The median party was in power for sixteen years; however there is a lot of variation in the data. Thirty-three parties survived in power for only 3–5 years, and forty-five parties were in power for over thirty years, with the longest-ruling party (Liberia's True Whig Party) in power for 102 years (1878–1980). Figure 1 displays the duration in power of the ruling parties in my sample.

Figure 1. Duration of autocratic ruling parties

Note: the histogram displays the number of years that each ruling party was in power. A count of the number of parties in each bin is listed above the bins. One outlier (the True Whig Party in Liberia, which was in power for 102 years) was excluded from this figure, and parties that were in power for less than three years are excluded from the analysis.

To illustrate a baseline level of institutionalization, I focus on the party's ability to survive leadership changes. Leadership transitions are critical junctures that provide a clear test of the party's ability to function independently of the incumbent. In fact, leadership succession is considered to be one of the most significant challenges for the survival of authoritarian regimes (Brownlee Reference Brownlee2007).

For every ruling party in this sample, I count the number of different leaders who took power.Footnote 11 However, leadership changes that occur too frequently may also be a sign of instability. To guard against this, I only consider leaders who remain in power for three or more consecutive years as a complete leadership cycle. Figure 2 displays the number of different leaders each ruling party had while in power.

Figure 2. Leader turnover in autocratic ruling parties

Note: the histogram displays the number of different leaders each party had while in power. A count of the number of parties in each bin is listed above the bins. Two outliers (the True Whig Party in Liberia, which had 12 different leaders and the PRI in Mexico, which had 15 different leaders) are excluded from the figure.

The data reveal that most ruling parties are unable to survive any kind of leadership transition. This is further highlighted when we examine the number of years the party is able to remain in power after the death or departure of the founding leader.Footnote 12

Founding leaders tend to be highly influential figures who enjoy mass support and high levels of legitimacy when they come to power (Bienen and van de Walle Reference Bienen and Van de Walle1989).Footnote 13 Félix Houphouët-Boigny for instance, the first post-independence president of the Ivory Coast, founded the Parti Démocratique de la Côte d'Ivoire in 1946. From the start of his presidency in 1960 until his death in 1993, Houphouët-Boigny kept tight control of authority within the party. In 1995, his favored successor, Henri Konan Bédié won the presidential election but was overthrown in a coup six years later (Akindès Reference Akindès2004; Jackson and Rosberg Reference Jackson and Rosberg1982).

Even when a leader did not create the party, the first leader of the regime often takes over party structures. Mao, for instance, was not an original founder of the CCP, but he quickly rose through the ranks and led the party and regime to power (Meisner Reference Meisner1986). In sum, because the first leader of an authoritarian party tends to be highly influential, we can infer that a party that can remain in power past the first leadership transition has much higher levels of organizational autonomy.

Figure 3 illustrates the number of years the ruling party remained in power after the death or departure of the founding leader. The data show that the average ruling party is unable to survive past the first leader: 57 per cent of parties fail to survive more than a year past the first leader's death or departure from power.

Figure 3. Autocratic ruling party survival beyond founding leader

Note: the histogram displays the number of years each ruling party remained in power past the departure of the first leader. A count of the number of parties in each bin is listed above the bins. One outlier (the True Whig Party in Liberia, which remained in power for 96 years after the departure of the first leader) is excluded from the figure.

This argument remains robust even if we exclude cases where the first leader is forcibly removed, most notably through a coup. To identify how the first leader left office, I rely on the Archigos coding of leader exit (Goemans, Gleditsch and Chiozza Reference Goemans, Gleditsch and Chiozza2009). I exclude all parties that had first leaders who were deposed through assassination, popular protest, a military coup, rebel groups or foreign governments from this analysis. The resulting subsample includes sixty-five parties with a first leader who died of natural causes, retired due to ill health or stepped down through established conventions (such as voluntary retirement or term limits). Even conditioning on cases in which the first leader experienced a non-violent exit from power, 52 per cent of ruling parties were unable to survive beyond the founding leader's peaceful departure. Appendix Figure 1 displays the number of years the ruling party was able to remain in power past the death or departure of the founding leader, conditional on a peaceful leader exit.

Moreover, even many parties that are coded as part of single-party regimes do not outlive the death or departure of the founding leader: 32 per cent of ruling parties that are coded as part of single-party regimes by Geddes, Wright and Frantz (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014) fail to survive a year past the departure of the first leader.Footnote 14 In addition, 33 per cent of ruling parties that are coded as part of any type of party-based regime (single-party, party-military, party-personal or triple-hybrid) do not outlive the founding leader. Appendix Figure 2 displays the number of years a ruling party that was coded as part of a single-party regime was able to remain in power past the death or departure of the founding leader.

To summarize, the data reveal three important lessons. First, if a ruling party has not yet undergone an initial leadership change, it is too soon to determine whether the party organization is durable. The data underscore how difficult it is for parties to outlive their founders, and the first leadership change constitutes a key critical juncture. The fact that the majority of parties cannot be expected to last beyond the tenure of a single leader calls into question whether most parties truly have the capacity to act as inter-temporal commitment devices that can manage elite conflict.

Secondly, strong ruling parties are much less common than we would currently expect. For instance, if we compare these proxies to the regime typologies framework, a third of party-based regimes do not meet basic thresholds of organizational autonomy.Footnote 15 These findings are consistent with studies that emphasize the difficulty of building strong and credible organizations in weakly institutionalized environments (Boix and Svolik Reference Boix and Svolik2013; Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2013).

Thirdly, these proxies of party institutionalization highlight the danger of conflating regime duration (the number of years the regime was in power) with the organizational strength of the ruling parties. For instance, thirty-seven parties were in power between 20 to 40 years. Yet almost a third of these parties (27 per cent) failed to survive beyond the tenure of the founding leader. This comparison reveals that many parties that seem to be durable and long-lived appear so only because they are attached to strong and charismatic leaders. Such strong leaders are frequently able to remain in power for long periods of time. Once the leader dies, however, the weakness of the party organization is often revealed.

To be clear, I am not proposing that scholars use the data presented in this section as new proxies for party institutionalization. My goal in this section is to use easily observable data to illustrate that most parties are not able to pass very conservative baseline tests of organizational autonomy. However, I do not propose that scholars simply use the raw count of leadership turnovers or years of survival past the founders as proxies for party institutionalization. Using these counts would conflate the outcome of party institutionalization with the measures themselves.

Substantive Implications

What are some of the substantive implications of decoupling party strength from leader strength? The previous section demonstrated that many parties that have been coded as part of single-party regimes are likely not very strong organizations and are unable to survive the departure of the founding leader. This section will show that important differences emerge when we separate out parties that can and cannot survive the death of the founding leader within the single-party regime category. Parties that are coded as part of single-party regimes but fail to survive longer than the founding leader perform significantly worse on outcomes such as economic growth and regime stability compared with those classified as members of single-party regimes that do survive past the founding leader. These findings suggest that strong parties do indeed matter for regime stability, even if they are rarer than we currently assume.

One of the central findings in the recent literature on authoritarian stability is that party-based regimes tend to be the most stable form of dictatorship. In their review article on one-party rule, Magaloni and Kricheli (Reference Magaloni and Kricheli2010) note that ‘compared to other types of dictatorships, one-party regimes last longer (Geddes Reference Geddes2003; Huntington Reference Huntington1968; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2008), suffer fewer coups (Cox 2008; Geddes Reference Geddes2008; Kricheli Reference Kricheli2008), have better counterinsurgency capacities (Keefer Reference Keefer2008), and enjoy higher economic growth (Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008; Gehlbach and Keefer Reference Gehlbach and Keefer2011; Gehlbach and Keefer Reference Gehlbach and Keefer2012; Keefer Reference Keefer, Winters and Yusuf2007; Wright Reference Wright2008)’ (124).

Scholars have attributed a number of causal effects of strong parties to regime stability. While some functions, such as creating a superficial party brand, can be carried out via weak organizations,Footnote 16 economic growth and conflict prevention require strong, autonomous parties. One core mechanism that drives economic growth in party-based regimes is the ability of institutionalized parties to attract private investment and promote technological innovation (Gehlbach and Keefer Reference Gehlbach and Keefer2011; Gehlbach and Keefer Reference Gehlbach and Keefer2012; Simmons Reference Simmons2016; Wilson and Wright Reference Wilson and Wright2017). North and Weingast (Reference North and Weingast1989) famously argued that economic growth cannot occur when ruling sovereigns have no method of credibly committing to not expropriate future earnings. Institutionalized parties that function independently of any particular leader provide a forum for elites to organize collectively, therefore creating de facto constraints on the leader. Rulers who renege on promises not to expropriate can expect to be sanctioned by elites, creating conditions that encourage private investment (Gehlbach and Keefer Reference Gehlbach and Keefer2011; Gehlbach and Keefer Reference Gehlbach and Keefer2012). Institutionalized parties can also regularize interactions between leaders and elites, resulting in greater transparency regarding policy changes, government revenue and spending. Having access to more information makes it more difficult for autocrats to obfuscate rent-seeking behavior.

Strong parties also play an important role in preventing the outbreak of conflict, whether through coup attempts or civil war onset. Coups d’état pose a significant risk to autocratic stability and are the most frequent way in which autocratic leaders are deposed (Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Coups arise within autocracies largely due to the inability of autocratic leaders to credibly commit to not abuse their ‘loyal friends’ (Magaloni Reference Magaloni2008, 1). Institutionalized parties solve this commitment problem by creating a parallel organization, out of the arbitrary control of the leader, that distributes spoils, benefits and jobs to party elites (Magaloni Reference Magaloni2008; Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Shifting control of access to benefits to the party organization reassures elites that they will continue to receive a steady stream of benefits that is uninterrupted by a leadership change.

These mechanisms also extend to the prevention of civil wars. Keefer (Reference Keefer2008) argues that armed conflict arises when incumbents cannot make credible promises to distribute public or private goods to large segments of society. This problem is often exacerbated by the fact that leaders without credible ruling organizations cannot rely on loyal civilian or military elites to safeguard the regime (Magaloni Reference Magaloni2008). Conversely, when leaders rule through institutionalized parties, they can make credible promises to provide public services or distribute benefits to social groups (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2010). By increasing accountability towards citizens and promoting elite cohesion around regime maintenance, regimes with strong ruling parties should experience fewer outbreaks of civil conflict.

Finally, institutionalized ruling parties can also facilitate peaceful leadership transitions (Brownlee Reference Brownlee2007). Since conflict over leadership succession is a common cause of coups (Frantz and Stein Reference Frantz and Stein2017) and civil wars (Kokkonen and Sundell Reference Kokkonen and Sundell2017), regimes that can solve succession challenges through the party are more likely to remain stable over the long run.

To summarize, regimes with strong parties should indeed perform better on outcomes such as economic growth or the prevention of coups and civil wars. However, as the previous section demonstrated, many ruling parties that have been coded as leading single-party regimes do not survive past the departure of the first leader, and therefore are unlikely to be truly strong.

I show that within the category of single-party regimes, parties that remain in power past the departure of the founding leader perform significantly better on these outcomes compared to parties that do not. It is important to note that I am not necessarily making a causal argument here. I am simply taking established arguments that single-party regimes perform better on certain outcomes, and show descriptively that when we decouple party strength from leader strength, there is important variation within the category of single-party regimes. This provides additional evidence that parties that do not remain in power after the departure of the founding leader are likely to be weak organizations that cannot function independently.

For this analysis, I focus on the subset of forty-nine regimes that have been coded as single-party by Geddes, Wright and Frantz. I create a dummy variable, Party Survived, that takes a value of 1 if the ruling party remained in power past the departure of the founding leader, and a 0 otherwise. Parties that do not survive the departure of the founding leader can be interpreted as weak parties, and those that do survive can generally be considered stronger.Footnote 17

I create three main dependent variables that reflect key regime outcomes: economic growth, coup vulnerability and the outbreak of civil conflict. The first variable, Economic Growth, is calculated as the regime's average yearly GDP growth rate. The second variable, Coup Attempts, is calculated as the percentage of years in which a coup attempt occurred in the regime. The third variable, War Onset, is calculated as the percentage of years for which the regime experienced an onset of civil conflict.Footnote 18

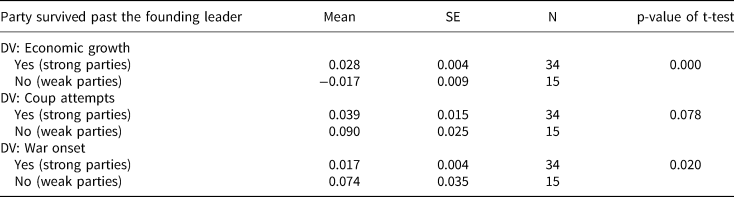

Table 1 summarizes key differences between parties that survive past the founding leader and those that do not. Parties that do not survive past the departure of the first leader perform significantly worse on all three outcomes compared with those that do. Of the forty-nine regimes that are labeled as single-party, eighteen include ruling parties that fail to remain in power past the departure of the founding leader. On average, these weaker parties experience significantly lower levels of economic growth, more coup attempts and more civil conflict onset, and the differences are statistically significant.

Table 1. Party strength and regime outcomes

Note: sample includes only regimes that are coded as single party by Geddes, Wright and Frantz (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014). Economic growth is calculated as the average yearly growth rate for each regime. Coup attempts and war onset are calculated as the mean number of coup attempts and mean number of years with new war onset for each regime.

These relationships remain consistent even when we consider other possible drivers of economic growth and conflict. Appendix Table 3 presents the results from regression analyses, which allow me to control for a number of other possible explanatory factors. Model 1 demonstrates that strong parties, as proxied by parties that survive past the founder leader, are positively associated with higher levels of economic growth, even when we control for GDP, oil production, ongoing civil wars and levels of democracy.Footnote 19 Models 2 and 3 show that strong parties are negatively associated with coup attempts and the outbreak of civil wars, even when controlling for poverty, oil and ethnic fractionalization (Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin2003; Londregan and Poole Reference Londregan and Poole1990). The results generally remain statistically significant, even with a limited number of observations.

Altogether this analysis demonstrates that when we differentiate parties within the single-party category according to survival beyond the founding leader, important substantive differences emerge along key regime outcomes. This provides additional evidence that parties that do survive multiple leadership transitions are more likely to be strong, and those that do not may have been miscategorized as part of single-party regimes. Moreover, these findings lend support to the argument that strong parties are indeed associated with better regime outcomes when we take into account the organization's ability to survive independently of the leader.

Conclusion

As the field of authoritarian politics has expanded, researchers have put forth a number of theories and hypotheses about the institutions and processes that drive authoritarian stability. Due to the scarcity of detailed cross-national data on the strength of authoritarian party organizations, researchers often turn to data on the existence of ruling parties or data on regime typologies as a proxy for strong parties. This article provides a cautionary tale about the accuracy of these indicators as proxies for ruling party strength.

Strong ruling parties should be able to survive their founding fathers, yet most ruling parties do not. Even many parties that have been classified as part of single-party regimes fail to survive the departure of the founding leader. This impermanence provides prima facie evidence that existing classifications of regime type may be an inaccurate reflection of the true underlying configuration of power between leaders and institutions. The mere existence of a ruling party does not guarantee its effective power or organizational capacity.

By demonstrating the relative rarity of strong ruling parties that can outlast particular leaders, this article also highlights an important limitation to arguments about the role of parties in dictatorships. Strong ruling parties, such as the PRI in Mexico or the CCP in China, may play a key role in promoting autocratic stability; however, only a limited number of parties are up to the task.

What is the way forward for future empirical research on authoritarian parties? One of the main takeaways from this article is that the first leadership change is a critical juncture for authoritarian regimes, and this provides a good litmus test for assessing the baseline organizational independence of ruling parties. This also suggests that scholars should be cautious of forming assessments of institutional strength when the regime is still in the term of its first leader. Founding leaders often promote their ruling parties as a way to amplify their own personal authority, and such regimes can appear to be single-party dictatorships. The fragility of the party organization is often not revealed until the leader's death or departure.

Moreover, as scholars continue to develop new datasets on authoritarian institutions, future measures of ruling party strength should consist of disaggregated indicators that reflect the bureaucratization of the organization. Some possible criteria include whether there are formal rules that determine promotion within the party hierarchy and to what extent such rules are followed. These types of disaggregated indicators will help distinguish party strength from leader strength, as well as move beyond the use of discrete regime types, which often obscures variation within categories. Moreover, researchers should be encouraged to rely more on objective indicators that can be replicated and verified. For instance, data that are collected from party constitutions can be cross-checked across multiple coders. Either the constitution has a particular rule in place regarding party promotion or it does not, and such an indicator does not rely on the judgment of individual coders.

Finally, since this article focused on elite-level politics, researchers can also collect additional indicators of party strength that reflect lower-level institutionalization and the ability of the party to fulfill other tasks not covered in this study. Some examples include building an organizational presence in rural areas, developing mass-level membership, establishing official forums to increase transparency for policy making, or establishing a system of dues or self-financing. Doing so will continue to help scholars better test theories, discover empirical trends, and complement qualitative and formal scholarship that examines the origins, logic and consequences of stable authoritarian rule.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/7H6XQO, and online appendices at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000115.

Author ORCIDs

Anne Meng, 0000-0002-0686-3734

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this article were presented at the Midwest Political Science Association Annual Meeting, the Virtual Workshop on Authoritarian Regimes, the Quantitative Collaborative at the University of Virginia, and the Southern Political Science Association Annual Meeting. I thank Leonardo Arriola, Jennifer Gandhi, Daniel Gingerich, David Leblang, Carol Mershon, Thomas Pepinsky, Robert Powell and Fiona Shen-Bayh for helpful comments and discussions. Chen Wang provided excellent research assistance.