Cultural values often have enormous staying power, outlasting the formal institutions and historical events that shaped them. The persistence of political preferences, religious views and civic traditions is well established, and more recent research has demonstrated the remarkable staying power of victim identities, risk and trust attitudes (Acharya, Blackwell and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018; Campbell et al. Reference Campbell1960; Charnysh Reference Charnysh2015; Lupu and Peisakhin Reference Lupu and Peisakhin2017; Myers Reference Myers1996; Nunn and Wantchekon Reference Nunn and Wantchekon2011; Pop-Eleches and Tucker Reference Pop-Eleches and Tucker2017; Putnam Reference Putnam1993; Wittenberg Reference Wittenberg2006). Some values – notably those connected to civicness and intergroup relations – are purported to have endured for over half a millennium, transmitted from one generation to the next (Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2016; Voigtländer and Voth Reference Voigtländer and Voth2012).

The standard view in the theoretical literature in biology and psychology is that both families and communities contribute to value transmission (Cavalli-Sforza and Feldman Reference Cavalli-Sforza and Feldman1981); social science research gives parental socialization the pride of place. Parents have been found to play a particularly important role in the formation of personality in early childhood (Piaget Reference Piaget1954). By contrast, communities are seen as important for shaping fast-changing beliefs about public preferences and behavioral norms (Giavazzi, Petkov and Schiantarelli Reference Giavazzi, Petkov and Schiantarelli2019; Tabellini Reference Tabellini2008). Even scholars who recognize the significance of the context in which families are embedded argue that families can counteract community influence by increasing their socialization efforts (Bisin and Verdier Reference Bisin and Verdier2001). However, there is also an alternative perspective: families that are in a minority in a community that is culturally different or actively hostile may be unable or unwilling to resist assimilating into the dominant value system, because assimilation increases the returns to co-operation with the majority group (Lazear Reference Lazear1999).

This article evaluates the role of community in the persistence of deep-seated and slow-changing values that shape political and economic behavior.Footnote 1 We ask whether the composition of the community matters beyond the baseline of family influence. Identifying the effect of community is challenging because individuals and families often self-select into like-minded communities in order to preserve their values. Whether an individual grows up surrounded by peers who share her family's values depends on parents' interest in inculcating these values in the first place.

Our study overcomes this endogeneity problem by leveraging as-if-random variation in community composition in the aftermath of mass displacement. We draw on a historical quasi-experiment whereby all families from the same region were forcibly resettled but only some ended up as the majority in their new communities. This enables us to identify the effect of community composition on the persistence of distinctive social values among the descendants of forced migrants and to overcome the problem of self-selection into migration or into specific community types. In this way we provide a novel test of an important theoretical proposition that remains empirically understudied.

After World War II (WWII), Poland's borders shifted westward, precipitating mass population transfers. Poles residing in provinces annexed by the Soviet Union were displaced to the territories that Poland acquired from defeated Germany. Political imperatives, such as taking swift ownership of German property while accommodating millions of uprooted Poles, as well as administrative realities, including the lack of familiarity with the new territory and the limited availability of transportation, resulted in a haphazard resettlement process. Family units remained intact, but whether families from the same area settled together at their destinations depended on factors orthogonal to migrants' characteristics and preferences: the availability of space on trains at their origin, the duration and itinerary of the trip, and the availability of housing in settlements at disembarkation. As a result, some migrants became part of the majority in their new settlements, whereas others ended up as a minority, outnumbered by Polish migrants from other, culturally distinct regions.

To study the long-term transmission of values, we focus on the population with distinct political traits prior to resettlement – Poles from the historical region of Galicia, today split between western Ukraine and southeastern Poland. Between 1772 and 1918, Poland was partitioned between the Austrian, Russian and Prussian empires. Galicia was governed by Austria, which encouraged education in Polish, facilitated the flourishing of Polish culture and religious traditions, and held relatively free elections. By contrast, Russian and Prussian administrations suppressed schooling in Polish, barred Poles from serving in local administration, and restricted manifestations of Polishness in religious and political spheres. As a result, by 1918, Poles in Austrian Galicia were more patriotic, religious and politically active than their brethren under Russian and Prussian control (Bartkowski Reference Bartkowski2003; Wandycz Reference Wandycz1974). Scholars concur that these traits have persisted into the present (Bukowski Reference Bukowski2018; Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya Reference Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya2015; Zarycki Reference Zarycki2015).

If the persistence of cultural values is a product not only of family socialization but also of community characteristics, then the descendants of Galician Poles who ended up in settlements dominated by Galician migrants should be more likely to exhibit traits associated with Austrian rule than their brethren who ended up in the minority in villages where the majority consisted of voluntary migrants from other parts of Poland. On these traits, the population of Galician-majority settlements should also be more similar to Poles whose families were not resettled because they lived just west of the new Polish–Ukrainian border, in western Galicia.

To test these hypotheses, we collected historical data on the village-level distribution of migrants in Silesia (southwestern Poland) and conducted a survey of 593 descendants of Galician migrants in sixty resettled villages, sampling an equal number of villages where migrants from Galicia dominated and villages where they were the minority. We also surveyed 100 respondents in ten Galician villages that were not uprooted. We use this second sample as a baseline for measuring distinctively Galician values, to substantiate our claim that differences between majority and minority resettled communities stem from the more successful reproduction of Galician cultural values in majority-Galician resettled communities rather than from the selection of migrants with specific values into majority or minority communities during resettlement or from the experience of being in the majority as such.

We find that respondents in Galician-majority villages are considerably more religious and patriotic today and are more likely to turn out to vote than respondents in minority Galician settlements. On these traits, they resemble respondents in Galician villages whose families were not resettled. At the same time, the persistence of Galician cultural values in majority settlements does not appear to explain voting preferences. Finally, as expected, respondents in majority and minority settlements are indistinguishable from each other on traits unrelated to the legacies of Austrian rule in Galicia.

These findings suggest that the transmission of values is more effective when families live in like-minded communities, and that major demographic disturbances or population movements weaken the transmission of historically rooted traits. Community is thus important for value transmission insofar as it can buttress and amplify the family's influence.

This project provides a systematic empirical test of a much-debated theoretical proposition that communities amplify the process of value transmission. We do not compare the relative weight of family to that of community in the transmission process, as families remained intact in both majority and minority communities. We study the variation in community structures that exists above and beyond family persistence. Nor do we examine how the descendants of Galician migrants differ from other residents in their communities (that is, the descendants of migrants from the Russian or Prussian partitions of Poland). This question would require a different research design and has been explored by Becker et al. (Reference Becker2020), who find that the descendants of forced migrants from the territories annexed by the Soviet Union have higher levels of human capital than the offspring of voluntary migrants from other parts of Poland.

We contribute to the literature on the transmission of cultural values and beliefs. In their review of the state of the literature on cognitive and institutional legacies, Simpser, Slater and Wittenberg (Reference Simpser, Slater and Wittenberg2018, 434) emphasize ‘the need to take mechanisms seriously. Paucity of information often appears at first to be an insurmountable barrier, but…ingenuity can open unsuspected avenues for research’. By exploring the role of communities in the transmission process in an empirically novel way, we aim to strengthen the overall research agenda on cultural legacies, in which the mechanisms underlying the persistence of political traits remain understudied. Our examination of transmission mechanisms also contributes to the study of the effects of forced displacement (Braun and Mahmoud Reference Braun and Mahmoud2014; Charnysh Reference Charnysh2019; Ibáñez and Moya Reference Ibáñez and Moya2010; Nalepa and Pop-Eleches Reference Nalepa and Pop-Eleches2018) and, more broadly, to research on the conditions under which migrants, both domestic and international, assimilate or retain their distinctive value systems (Barni et al. Reference Barni2014; Fouka Reference Fouka2019; Giavazzi, Petkov and Schiantarelli Reference Giavazzi, Petkov and Schiantarelli2019).

Understanding Mechanisms of Transmission

There is a fledgling consensus in the literature on the long-run persistence of cultural values that both families and communities matter for value transmission. The emphasis on family and community as twin engines of value persistence is well grounded in an influential theory of cultural transmission by Cavalli-Sforza and Feldman (Reference Cavalli-Sforza and Feldman1981), who distinguish between vertical and horizontal processes. Vertical transmission refers to family socialization, and horizontal transmission describes the influence that peers and community authority figures have on the formation and evolution of values and beliefs. In recent studies of the long-term persistence of values, both vertical and horizontal transmission are commonly subsumed under the label of intergenerational socialization. For instance, in their work on the persistence of racism in the US South, Acharya, Blackwell and Sen (Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018, 24–46) distinguish between two mechanisms of reproduction: intergenerational socialization and institutional reinforcement.

Scholars usually give the pride of place, explicitly or implicitly, to transmission within families. Tabellini (Reference Tabellini2008) hypothesizes that deeply held moral judgements about the proper state of the world are best transmitted within families. Giavazzi, Petkov and Schiantarelli (Reference Giavazzi, Petkov and Schiantarelli2019) concur, noting that communities' socializing influence is likely limited to the induction into and transmission of fast-changing expectations about acceptable norms of behavior in a group, and that communities are less important in the transmission of deeper values. Bisin and Verdier (Reference Bisin and Verdier2001) take a more favorable view of community by arguing that it can socialize individuals into specific value systems, yet they still maintain that families that invest sufficient effort into shaping their offspring's views can successfully resist the effects of hostile community socialization. On the other end of the spectrum is Lazear's (Reference Lazear1999) hypothesis: in research on immigrant assimilation, he has argued that small minorities will always adopt the culture of the majority group and that families will always assimilate when outnumbered because the gains from assimilation outweigh the benefits of retaining their values.

We hypothesize that communities play an important role in the transmission of deep-seated social values, and that communities matter above and beyond the family baseline. Value transmission is much more likely to be successful in situations where the family's efforts are buttressed by those of other like-minded families and community elites. Put simply, the same parental effort to socialize their offspring into a set of values will be more effective when such values predominate in a given community compared to a situation in which families find themselves in an unfamiliar or hostile environment. In addition, either parents or their children will seek to conform to the majority value system (assimilating, as hypothesized by Lazear (Reference Lazear1999)), even when that value system contradicts the one internalized by the family, in order to maximize the benefits of co-operation in a mixed community.

Context

To identify the impact of community on the transmission of cultural values, we leverage a natural experiment of history that closely approximates the ideal design of similar families being randomly assigned to different communities. This section provides background on the post-WWII displacement in Poland to substantiate our claim of as-if-random settlement patterns.

The Process of Forced Resettlement

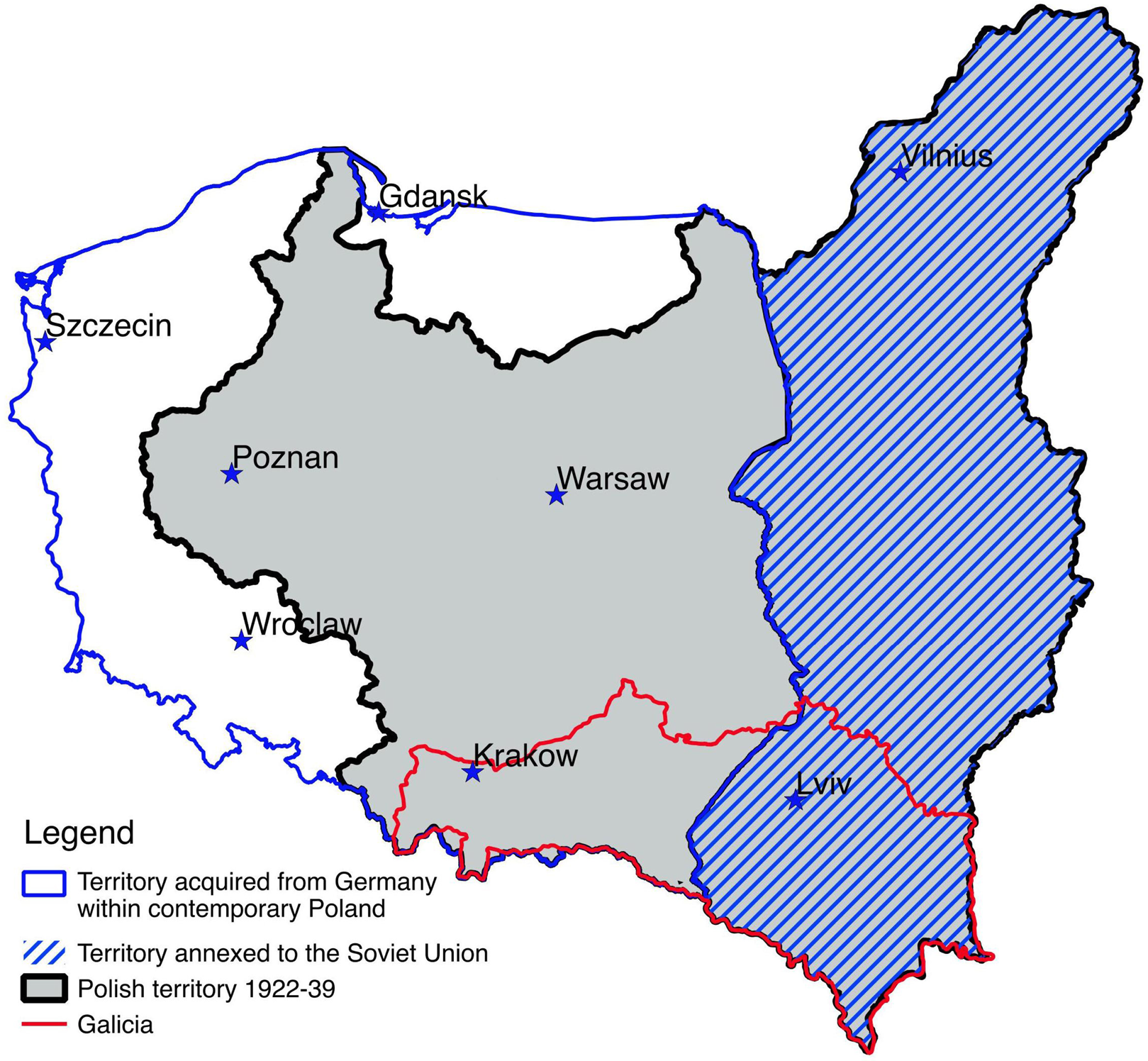

At the end of WWII, the Soviet Union annexed 45 per cent of pre-war Polish territory (see Figure 1). The post-1945 Polish–Soviet border largely followed the Curzon line, drawn up at the end of WWI as a proposed boundary to separate areas with ethnic Polish majorities to the west from those with ethnic Lithuanian, Belarusian or Ukrainian majorities to the east. As compensation for the losses of eastern territories, Poland received 101,000 square kilometers from defeated Germany, including parts of Eastern Prussia and the city of Danzig.

Figure 1. Changes to Poland's territory in 1945

Stalin was keen to establish states dominated by titular ethnic majorities in order to minimize the likelihood of internal conflicts. Mass population transfers were undertaken to achieve this objective: ethnic Germans were expelled from the newly reconfigured Poland, and ethnic Poles from the now-Soviet territories were ‘voluntarily repatriated’. More than 5 million Poles were resettled from areas annexed by the Soviet Union and from other parts of Poland into the territories that Poland acquired from Germany in 1945.

This article focuses on Polish migrants from the historical region of Galicia, which straddles the post-1945 Polish–Ukrainian border. These migrants comprise the largest culturally homogeneous group resettled to the formerly German territories. Focusing on Poles from eastern Galicia minimizes concerns about selection into migration, as their exodus in the aftermath of the border changes was nearly universal.Footnote 2

At the heart of our research design is the claim that resettlement was quasi-random, with otherwise similar families assigned to different types of communities. This section uses the historical record to support this claim; in the subsequent section on research design we reinforce the qualitative accounts of resettlement with quantitative evidence, including balance tests on pre-resettlement characteristics of the origin and destination settlements.

The Soviet government and its clients in Poland wanted to present the international community with a fait accompli in case Western allies changed their minds about the annexation of German territory (Thum Reference Thum2011). Political expediency, limited state capacity after a devastating war, and the sheer vastness of the task all resulted in a highly disorganized resettlement process. Historians have described the resettlement process as ‘total chaos’ (Kersten Reference Kersten, Ther and Siljak2001, 83) and a ‘fail[ure of] coordination between officials’ (Kochanowski Reference Kochanowski, Ther and Siljak2001, 143).

Administrative capacity was weak as Poles from abroad, from central Poland, and from the now-Soviet borderlands streamed simultaneously into formerly German settlements. Those coming from the Soviet Union traveled along one of the three major railways running on the east–west axis (see Appendix Figure A.1). Poles leaving western Ukraine boarded along the southernmost route running from Lwów and Rawa Ruska in Galicia to Opole and Wrocław in Silesia (Śląsk). Migrants were permitted to bring personal items, farm equipment and cash, yet most arrived empty handed, having left in a hurry, been robbed, or been forced to trade belongings for food on a journey that took around three weeks (Kosiński Reference Kosiński1960).

At the point of departure in western Ukraine, families were instructed to appear at the nearest railway station. Whether they boarded the train with other families from their own or neighboring settlements depended on who was at the station at the time of embarkation and on the availability of space on a specific train. Residents of the same villages were often split into several transports, departing weeks or even months apart. There were no schedules or predetermined itineraries, and the initial wait for embarkation could last 10–15 days (Kulczycki Reference Kulczycki2003; Sula Reference Sula2002). Once on the train, migrants were at the mercy of the post-war railway system that prioritized the movement of troops and suffered from poor management (Kochanowski Reference Kochanowski, Ther and Siljak2001). In theory, migrants were supposed to be dropped off at specific locations. In practice, they were often unloaded in the middle of fields or at stations deemed convenient by train conductors. Kochanowski writes that ‘particularly in 1945, no arrangements were made [for arriving expellees]’ (p. 145). As a result, ‘sometimes where the transported ended up was a matter of pure chance’ (Thum Reference Thum2011, 68). State Repatriation Office Director Władysław Wolski lamented that migrants were often offloaded partway to their destinations, in the middle of an open field, because conductors lacked route plans (Ciesielski Reference Ciesielski2000).

As forced Polish migrants weaved their way westward, Germans were evicted, and voluntary migrants from central Poland and Western Europe streamed into the formerly German settlements.Footnote 3 Notably, officials in charge of resettlement did not have the most up-to-date information about the dynamics on the ground (Kochanowski Reference Kochanowski, Ther and Siljak2001). As a result, once off the train, migrants were frequently sent from one destination to another when it turned out that officials had incorrect information about the availability of housing. It was not uncommon for groups of friends or neighbors or even family members to get separated at this stage, even if they succeeded in boarding the same train. In a representative account, Galician migrant Marian Samulewski (ND) described his tribulations as follows: ‘We were told our trip was over […] but there were no more empty houses in Wierzchówo, so only 3–4 families were able to settle there’. Samulewski's family stayed put in Wierzchówo; others continued on their journey.

Once a family had located a house, it was unlikely to move to reunite with former neighbors and friends from Galicia. Initially, there was too much uncertainty regarding whether accommodation would be available in some other settlement. There were also rumors of a new war with Germany and widespread expectations that resettlement was temporary, which reduced incentives to relocate. Once the initial settlement period had passed, self-sorting into village communities became difficult administratively, in part because until 1957 migrants could not freely sell or exchange land obtained from the state in the new territories (Machałek Reference Machałek2005). We address concerns about post-resettlement sorting in more detail in subsequent sections.

Forced Migrants from Galicia: Distinctive Cultural Values

This section briefly describes the Polish experience under Austrian, Prussian and Russian rule (1792–1918), with a focus on distinctive traits acquired by Poles in Galicia, the northernmost province of the Austrian Empire.Footnote 4 Unlike their brethren in Protestant Prussia and Orthodox Russia, Poles who lived in the Catholic Austro-Hungarian Empire practiced Catholicism freely. Their children studied in Polish-language schools. Starting in 1869, courts and state administration in Galicia used Polish, and by 1870–71 Polish was the language of instruction at leading universities. By contrast, in the Prussian and Russian empires, the use of Polish in administration and education was limited and periodically banned (Wandycz Reference Wandycz1974). The Austro-Hungarian Empire was also the first to introduce representative institutions and to allow regional self-governance. Poles dominated Galicia's elected legislature and held senior positions in the provincial executive. In Prussia and Russia, Poles were largely denied access to positions in regional government or opportunities to vote for Polish candidates and parties (Wandycz Reference Wandycz1974).

Scholars concur that Austrian rule imparted a set of distinctive political values that still distinguish Galicia from the rest of Poland.Footnote 5 Poles in the former Austrian partition are today more religious, conservative, patriotic, and nationalist and are more likely to vote and support the democratic form of government than Poles in the former Prussian and Russian partitions (Bukowski Reference Bukowski2018; Drummond and Lubecki Reference Drummond and Lubecki2010; Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya Reference Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya2015; Zarycki Reference Zarycki2015). In the Appendix we run a set of geographic regression discontinuity analyses, which demonstrate that religiosity and turnout rates are higher among Poles living in the former Austrian partition (Tables A.1 and A.2).

Scholars of Polish voting behavior commonly argue that cultural values rather than economic attitudes shape voting in Poland, and that religiosity is more informative of political preferences than the size of one's pocketbook (Jasiewicz Reference Jasiewicz2009; Stanley Reference Stanley2019). Higher religiosity and patriotism in the former Austrian partition suggest greater support for the right-wing Law and Justice Party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość), which champions the traditionalist version of Polishness rooted in Catholic values and nativism. At the same time, longer experience with elections under Habsburg rule would suggest higher support for the center-right Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska), which emphasizes progressive individualism and has positioned itself as the ‘chief defender of liberal-democratic transition’ (Stanley Reference Stanley2019, 21).

Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya (Reference Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya2015) find that both the Law and Justice and Civic Platform parties perform better in the former Austrian partition than in the former Russian partition, due to a combination of higher turnout and lower support for the post-communist Left. We replicate their analyses in the Appendix using municipal-level electoral returns from the first round of the 2015 presidential election and the 2015 parliamentary election. We find that support for the Civic Platform is slightly higher in the former Austrian partition compared to the Russian partition, whereas differences in support for Law and Justice across the border do not reach significance.Footnote 6 There appear to be no differences in income, industrial production, corruption, or institutional trust on either side of the former imperial borders (Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya Reference Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya2015).

Theoretical Expectations

Scholars disagree about the extent to which community structures affect the transmission of cultural values given that parental socialization is such a dominant channel. We hypothesize that communities play an important role in the value transmission process, and that Galician values would be more likely to persist in majority-Galician settlements. Thus we expect the descendants of forced migrants in villages that had been settled mostly by migrants from Galicia after WWII to be more patriotic, religious and politically active than the descendants of the same migrant population in villages with a minority of Galician migrants (Hypothesis 1).

Furthermore, we expect the differential persistence of Galician values in majority and minority communities to inform political preferences: we predict that the descendants of Galician migrants in majority communities will be more supportive of the Law and Justice and/or Civic Platform than their counterparts in minority communities (Hypothesis 2). We thus hypothesize that the inherited Galician traits will have an indirect influence on respondents' political choices. Finally, we expect that the descendants of Galician migrants in majority communities will be very similar or identical to the descendants of Galician Poles who were not displaced on traits associated with Austro-Hungarian rule, since both groups of respondents would have been surrounded by like-minded families since 1945 (Hypothesis 3). This last hypothesis tests the proposition that differences in religiosity, patriotism, and political engagement between majority and minority Galician communities are due to the fact that Galician-majority communities are better able to preserve unique Galician cultural traits.

It bears highlighting that these hypotheses do not challenge the standard view in the literature that family socialization is an important channel of value preservation. Rather, we test how much community structures matter beyond the family baseline.

Research design

Survey Sampling Strategy

To identify majority and minority Galician communities, we built a dataset on the origins of the migrant population in Silesian villages that had been vacated by ethnic Germans using archival documents from the 1940s and secondary sources. Towns and cities were excluded because of high mobility. The roster of resettled villages is as complete and precise as the imperfect historical record allows. For instance, in one Silesian province (Opole), data on migrants' exact places of origin based on historical property deeds are available for two-thirds of all the settlements.Footnote 7 We then randomly sampled thirty-three villages where, at the conclusion of the resettlement process, forced migrants from Ukrainian Galicia were in the majority and thirty-three villages where migrants from Ukrainian Galicia were in the minority and the majority group consisted of voluntary migrants from Central Poland (predominantly Russian partition). We refer to these two types of villages as majority and minority. A majority village is one in which migrants from Galicia made up 60 per cent or more of the total population (81 per cent on average). In minority villages, Galician migrants were 40 per cent or less of the population (35 per cent on average). In each village, we interviewed village elites (mayors, priests, teachers) to confirm the origins of local residents (the correlation between elite reports and historical data was r = 0.73). Over the course of fieldwork six villages had to be dropped: five because enumerators had difficulty finding respondents there – this proved especially challenging in minority villages – and one because there was confusion in the historical record and during fieldwork about the composition of its migrant population.Footnote 8

Enumerators were asked to locate ten descendants of forced migrants from Galician Ukraine in each of the villages. We aimed to maximize the number of respondents and the number of communities while minimizing costs. We interviewed only the descendants of migrants from Ukrainian Galicia, not those from other origin groups. Only one respondent over the age of 18 was interviewed in every selected household.Footnote 9 Overall, the survey was completed in thirty-two majority and twenty-eight minority villages; 310 respondents were interviewed in majority villages and 283 in minority villages for the total of 593 second- or third-generation descendants of resettled Galician Poles.Footnote 10 Villages where the survey had been completed are mapped in the southwestern quadrant of Figure 2. Minority villages are somewhat clustered in the north. This does not pose an inferential challenge given that all the settlements are located within 100 kilometers of each other. We discuss the clustering issue further in the Appendix on pp. 12–13. The survey was completed in the fall of 2016. Response rates were high by the standards of public opinion work in Europe at over 70 per cent. We present additional information about the enumerator teams and survey structure in the Appendix (p. 14).

Figure 2. Sampled Silesian settlements (western Poland) and settlements of origin (eastern Galicia)

We also interviewed 100 respondents in ten villages just west of the post-1945 Polish-Ukrainian border in the contemporary Polish province of Podkarpackie (see map in Appendix Figure A.3). These villages were in the same institutional environment as migrants' villages of origin before 1945, but, being located on Polish territory, were not subject to resettlement. We use this comparison group to provide additional evidence that the observed differences between majority and minority villages are due to the greater persistence of Galician traits in majority communities rather than migrants' self-selection or the experience of being in the majority as such. To maximize the chances of finding respondents of Galician origin, we picked the ten comparison villages at random from a list of settlements that were ethnically Polish prior to WWII since ethnically mixed communities in western Galicia experienced large population turnovers during and after WWII. As a result, the western Galician settlements are not a perfect comparison group; they were historically more ethnically homogeneous than villages from which Galician migrants originated. This biases against finding similarities between the western Galician baseline and the majority-Galician settlements in western Poland.

Pre-treatment Balance

A major challenge to the claim of quasi-random assignment of migrants to majority or minority communities is self-sorting. For instance, more religious or patriotic migrants might have made a special effort to band with like-minded settlers into majority-Galician villages. If this were the case, then contemporary differences in values between majority and minority communities would be due to selection rather than to the hypothesized persistence of Galician traits.

This section uses village-level historical dataFootnote 11 to address concerns about the selection of migrants from different types of origin villages into different types of destination villages, since there is no data on migrants' values at the time of resettlement. Data on migrants' settlements of origin in Galicia come from survey questions about the birthplaces of respondents' maternal and paternal grandparents.Footnote 12 Eighty-six per cent of the origin settlements are in Ukrainian Galicia; the remainder are in Volhynia, on the Russian side of the former imperial border. The settlements of origin are plotted in the southeastern quadrant of Figure 2. The symbols on the map indicate whether residents of a given settlement wound up in a majority village (triangle), a minority village (arrow), or both village types (star). The spatial pattern suggests that there is no obvious clustering by village type.

In Table 1 we compare ethnic composition and voting behavior across the different types of origin settlements.Footnote 13 Data on the ethnic composition of the origin settlements come from the 1921 Polish census, the only interwar census with information below the county level for Galicia.Footnote 14 Electoral data are for the 1922 and 1928 legislative elections, which were the only free and fair elections in interwar Poland. The origin settlements are very similar in population size, ethnic and religious composition, and voting behavior. The sample size for electoral outcomes fluctuates between different political parties, but all voting differences are substantively small and do not reach significance. Turnout, the variable on which we expect differences across minority and majority destination villages, was measured for all origin settlements with at least 500 voters and is nearly identical across the two village types. Overall, the data support this project's foundational assumption that Galician migrants who settled in majority and minority villages originated from very similar settlements.

Table 1. Pre-migration covariates in settlements of origin

Note: we provide data for all the major parties that ran candidates across multiple districts in the region of Galicia. N is lower for electoral data because voting results were published only for settlements with over 500 voters and because parties did not run in all districts. Coefficients are group means; standard deviations and errors in parentheses. Two-tailed t-tests; differences in means are presented as absolute values.

We also use data from the 1939 German census to compare economic conditions in migrants' destination villages in western Poland on the eve of WWII. As reported in Table 2, the villages that would be settled in a few years' time by different proportions of forced and voluntary migrants were nearly identical in size and economic structure, as measured by land ownership, characteristics of the labor force, and distance from the railway. Once again, differences across the majority and minority villages are negligible in magnitude and do not reach statistical significance.

Table 2. Pre-resettlement characteristics of destination villages

Note: coefficients are group means. Standard deviations/errors in parentheses. Two-tailed t-tests; differences in means are presented as absolute values.

In Appendix Table A.6, we also present balance tests on contemporary post-treatment variables across the two village types. We find no differences in education, income, or village size, though minority settlements have slightly larger populations in the present. As expected, majority and minority localities are also similar in their cultural composition, comprising predominantly migrants from the Russian and Austrian partitions in different proportions.

Results

Main Findings

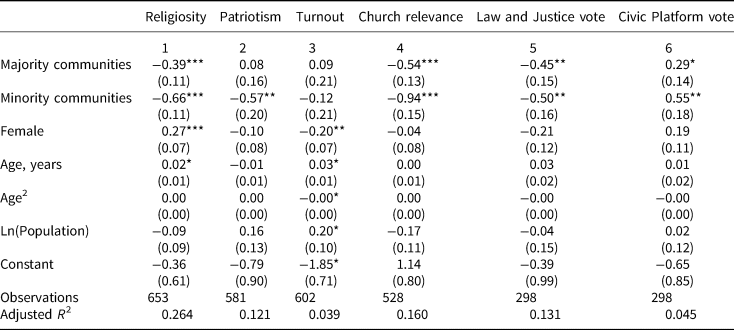

In Table 3, we test the hypothesis that political values associated with Austrian imperial rule in 19th-century Poland – religiosity, patriotism and political participation – are more likely to have persisted in communities where migrants from Ukrainian Galicia are in the majority than those where they are in the minority.Footnote 15 There are two models for each dependent variable: a bivariate model that includes only a dummy for residence in a majority village against the baseline of living in a minority village and a full model with controls. The fully specified model includes pre-treatment controls from the 1939 German census (settlement size, share of population in agriculture, share of large farms (above 20 ha)) and distance to the railway in 1946, as well as controls for gender and age from the survey. The models exclude post-treatment variables such as settlement size in the present as well as income and education levels, because these variables might themselves be a product of variation in the resettlement dynamics.Footnote 16

Table 3. Persistence of Galician values in majority communities

Note: OLS regression. Standard errors clustered at the settlement level in parentheses. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

The dependent variables are factored indices (see detailed description in the Appendix on pp. 15–17). We use factor analysis to combine multiple survey questions into a few measures to facilitate the presentation of the findings.Footnote 17 The religiosity index captures how often the respondent prays, attends religious services, and listens to religious radio programming. The patriotism measure combines responses to questions about one's level of pride in being Polish and belief in the importance of supporting the Polish government irrespective of its policies. The voter turnout index, a proxy for political participation, combines answers to questions about actual turnout in the most recent presidential election (2015) and turnout in a hypothetical upcoming parliamentary election. The estimation technique is ordinary least squares (OLS), and standard errors are clustered at the settlement level. We also replicated these and subsequent analyses using hierarchical models to allow for the fact that respondents are nested within settlements (see Appendix Table A.7). The results hold irrespective of the estimation approach.

Consistent with expectations, the residents of majority villages are more religious and patriotic today. They are also more likely to turn out to vote than their peers in minority settlements. To facilitate interpretation of these coefficients, we visualize the magnitude of the effects in terms of changes in standard deviation in the dependent variables in Figure 3. Those in majority communities are more religious by 0.28 of a standard deviation and more likely to turn out in elections by 0.22 of a standard deviation. The effect of living in a majority community on patriotism is by far the largest, amounting to an increase equivalent to 0.60 of a standard deviation.

Table 4. Political preferences in majority communities

Note: OLS regression. Standard errors clustered at the settlement level in parentheses. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Nineteen per cent of respondents were born to couples in which one parent is from Austrian Galicia and the other from Russian Volhynia; 15 per cent were born into Volhynia-only couples. In Appendix Table A.8, we examine whether political values associated with Austrian rule are more strongly expressed once we exclude respondents of Volhynian ancestry.Footnote 18 Among those of pure Galician ancestry, all the effects associated with living in majority communities are consistently larger in magnitude and statistically significant. This analysis confirms that there is something uniquely Galician about the traits we study, as they are expressed more strongly among respondents who have both sides of the family originating in Galicia. It also suggests a mutually reinforcing rather than substitutive relationship between community and family transmission: if families compensated for community influence by amplifying their socialization efforts in minority settings, we would see the attenuation rather than the strengthening of the majority effect in this subsample.Footnote 19

We have now established that the core Galician values are more persistent in villages where migrants from Galicia constitute a majority. Do these values translate into political preferences (Hypothesis 2)? We measure party preferences using a factored index that combines reported vote for the candidate from the conservative and nationalist Law and Justice Party or the more liberal Civic Platform in the 2015 presidential election and an intention to vote for these parties in a hypothetical parliamentary election. We also examine the relevance of religion to politics – the two are linked in the literature on voting behavior in Poland (Jasiewicz Reference Jasiewicz2009) – using a factored index that combines respondents' opinions about the relevance of the Catholic Church to individuals' moral needs, problems of family life, and Poland's social problems. The results of analyses modeled in the same way as those in Table 3 are reported in Table 4. As expected, respondents in majority villages are considerably more likely to view the Church as relevant to politics than their counterparts in minority settlements. The differences between majority and minority communities on this outcome amount to one-third of a standard deviation (see the lower half of Figure 3). However, living in a majority village does not predict party preferences. The coefficients on Majority Communities are positive for the Law and Justice vote and negative for the Civic Platform vote, but do not reach significance. It seems that higher religiosity and patriotism do not translate into higher support for the Law and Justice Party. This might be because Galician political values do not map well onto the Law and Justice political platform or because the descendants of Galician migrants vote strategically in a region where the Civic Platform is more popular.Footnote 20 This finding is consistent with results from geographic regression discontinuity analyses by us and other scholars who also do not find conclusive evidence that Poles in the former Austrian partition are more likely to support the Law and Justice Party (see Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya (Reference Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya2015) and our analysis in Appendix Table A.2.)

Additional Tests and Robustness Checks

A concern mentioned earlier is that unobserved differences in the strength of social connections prior to resettlement might drive our findings on turnout, religiosity, and patriotism. It is possible that more tight-knit Galician communities were able to stay together upon resettlement, making an extra effort to travel and disembark together. Yet historical records and the fact that even majority-Galician villages contain migrants from different Galician settlements suggest that such co-ordination was unlikely. While we lack pre-treatment data on social capital in the origin villages, we are able to examine contemporary differences in the reported density of social ties across the two village types. We do so by combining responses about the frequency of attendance at meetings, interest groups, get-togethers with friends, and joint work with others on improvements to the settlement into an index of village integration. As shown in Appendix Table A.9, majority and minority villages do not differ on this index.

Respondents in majority and minority settlements are also similar on traits that are not associated with the history of Austrian rule or that are constant across the partition borders in the non-resettled regions of Poland today. In particular, they have similar levels of interpersonal trust (neighbors and strangers), institutional trust (church, police, parliament, and government), and trust in foreign governments (EU, Germany, Russia, Ukraine). Nor do they differ in attitudes toward Jews or Muslim migrants or in their evaluations of the communist period. We plot these null results across the two community types as predicted changes in standard deviations in Figure 4. The underlying models are presented in Appendix Table A.9.

Figure 4. Effect of living in a majority village on interpersonal trust, trust in foreign leaders, attitudes toward Jews and Muslims, views on living under communism, and social capital (village integration)

Note: estimates and 95 per cent confidence intervals are based on Models 2, 4, 6 and 8 in Appendix Table A.9.

While we show that majority and minority villages do not differ in their proximity to the railway, a possibility remains that, say, majority villages were more accessible, which could have implications for the persistence of cultural values. Furthermore, migrants motivated to preserve Galician values may have sorted into majority villages in the post-resettlement period when relocation opportunities opened up, contaminating the interpretation of the ‘community’ channel of transmission. Several factors mitigate against this concern. Until 1957, resettlers to western Poland were not permitted to sell or exchange land (Machałek Reference Machałek2005), which impeded self-sorting across migrant communities. Anecdotally, over the course of fieldwork we did not come across any families that moved to a different village after resettlement in order to reunite with their former neighbors. The first census data on the level of in-migration date to 1988 and are only available for municipalities, one administrative level above individual settlements. The census asked whether respondents had been born in the settlement where they resided at the time. In Appendix Table A.6 we present evidence against self-sorting: proportions of the non-indigenous population are similar, at 51 and 50 per cent, in municipalities with majority and minority settlements, respectively.Footnote 21 While these facts help mitigate against the challenge to our research design that comes from possible self-sorting following resettlement, we cannot rule out the incidence of self-sorting entirely.

By design, we did not collect data on political attitudes and behaviors among non-Galician families in majority and minority communities. Additional data collection of this kind would have been expensive, and we were not worried about the non-Galician population, because it was the same – descendants of voluntary migrants from the Russian partition – in majority and minority Galician villages. However, without information about the values of voluntary migrants from central Poland it is harder to establish that the reported effects solely reflect the weakening of Galician values in minority communities relative to majority communities. We addressed this concern by checking in Appendix Table A.4 whether in resettled municipalities a higher proportion of migrants from Ukrainian Galicia – irrespective of whether they are settled as majorities or minorities – is associated with a higher incidence of what we have identified as uniquely Galician political values. We found that a greater share of migrants from Western Ukraine in 1948 predicts higher contemporary levels of religiosity and turnout as well as lower vote for the Civic Platform candidate in the 2015 presidential election but not higher support for the Law and Justice Party. This once again confirms that there is such a thing as a set of Galician cultural values, and that they are in evidence in our region of study against the baseline of voluntary settlers from the Russian partition.

Comparison to Western Galician Villages

In this section we compare the descendants of Galician migrants to respondents in villages immediately west of the post-1945 Polish–Ukrainian border, in Podkarpackie province, to verify that the Galician-majority resettled communities are different from minority settlements on specifically Galician traits, and that the transmission of these traits – rather than sorting or the experience of being in the majority as such – explains our findings.

We expect the descendants of migrants from eastern Galicia in majority villages to be more similar to respondents in western Galicia than respondents in the minority villages, in line with Hypothesis 3. Alternatively, if greater religiosity, patriotism, and turnout in majority-Galician resettled communities are a product of self-selection of Galician migrants with such characteristics into majority communities, then respondents in majority communities should be more patriotic, religious, and politically active than non-resettled Galicians in Podkarpackie and the residents of minority communities. To test these propositions, we re-ran the analyses from Table 3 using villages west of the Ukrainian border as the reference group and binary indicators for majority and minority villages as key explanatory variables.

The results are reported in Table 5. In all models, the coefficient on Minority Communities is larger in magnitude than the coefficient on Majority Communities, suggesting greater similarity in responses between the residents of Galician-majority resettled communities and the non-resettled communities in Podkarpackie. Respondents in both majority and minority communities are less religious than the non-resettled baseline, but those in the minority villages are only half as religious as the residents of Podkarpackie (Model 1). As predicted, the levels of patriotism are statistically indistinguishable for respondents in Podkarpackie and majority-Galician villages in Silesia, whereas patriotism is considerably lower in the minority villages (Model 2). For turnout, there are no statistically significant differences between Podkarpackie settlements and minority villages, contrary to Hypothesis 3, though the coefficient is negative as expected (Model 3).

Table 5. Comparison of resettled migrants to the Western Galicia baseline

Note: settlement size is measured for 1939 in treated villages and in 1921 for Podkarpackie villages. OLS regression. Standard errors clustered at the settlement level in parentheses. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

With respect to political values, there are also greater similarities between the majority and non-resettled villages than between the minority and non-resettled villages. In particular, while respondents in both majority and minority communities are less likely to view church as relevant to politics, the coefficient is nearly twice as large in magnitude on the minority dummy as on the majority dummy. Respondents in both majority and minority resettled communities are less supportive of the Law and Justice Party and more supportive of the Civic Platform relative to respondents in the non-resettled villages.Footnote 22

Overall, the comparison of majority and minority resettled communities to villages in southeastern Poland is consistent with the hypothesis that community bonds facilitate the transmission of historically held values. This evidence contradicts the alternative explanation that more religious, patriotic, and politically active Galician migrants self-selected into the majority villages. The descendants of forced migrants from western Ukraine in majority communities are more similar to the comparison group of western Galicians who never moved than to the descendants of forced migrants from the same region in minority villages. We do, however, observe a considerable weakening of the Habsburg legacies in the aftermath of displacement even in majority communities, especially with respect to the norms that could not be openly expressed under communism, such as religiosity and voting, as opposed to patriotism, which was encouraged.

Understanding Community Transmission Processes

The preponderance of evidence suggests that Galician values are more likely to endure in villages with Galician majorities. The implication is that communities of like-minded families enhance and perhaps activate the transmission of cultural values carried within individual family units, even in the same institutional environment. The theorized channel of transmission is repeated social interaction with migrants from the same region, similar to the socialization process described in Acharya, Blackwell and Sen (Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018). As observed in ethnographic studies, the identity of the dominant group plays a key role in determining which traditions persist and which will eventually disappear (Pawłowska Reference Pawłowska1968). Even though local organizations – churches, schools, and clubs – were similar across majority - and minority-Galician villages, as shown in the Appendix, the content of the values they transmitted depended on the relative sizes of the migrant groups.Footnote 23 The transmission of values also took place through daily rituals and cultural practices, outside of institutionalized settings. For example, religiosity was reinforced through regular June and May prayers under the village cross, rosary prayers in fraternities, midnight masses, and indulgences (150, 187). These types of events were considerably more common in Galician-majority communities.

For instance, in the majority village of Dziadowa Kłoda, migrants from Galicia asked the priest to assign church pews based on region of origin and did not attend the funerals or weddings of migrants from other regions (Hołubecka-Zielnicowa Reference Hołubecka-Zielnicowa1970, 66). Preserving higher levels of religiosity, patriotism, and political participation was often as simple as finding oneself among peers from Galicia. In the words of Genowefa Kruk (ND), resettled to Siedlce, ‘Here […] the majority of people came from Obertyn, Dolina, and Stryj [Galician settlements], so all of our traditions were simply transported here. Nothing has changed…What we did there, we do here.’ Similarly, Jozefa Rudnik, resettled from Usznia (western Ukraine) to Domaniów recalls: ‘When we came here, we brought our culture from the East’ (quoted in Jakubowska Reference Jakubowska2014, 35).

The larger the share of Galician migrants, the more people would participate in social practices that reinforce political values associated with Austrian rule in a new environment. Shared values were often tied to physical reminders of migrants' region of origin, which included church bells and works of religious and patriotic art. One example is the so-called Kresy Madonnas,Footnote 24 religious depictions of the Virgin Mary that carry high cultural and historical significance – eighty of which are located in parishes around Silesia. In Grodziec, a majority settlement in our sample, religious and patriotic traditions are strengthened by the presence of Madonna Częstochowska, a seventeenth-century icon originally from the parish of Biłka Szlachecka, now in western Ukraine.Footnote 25 Not all of the Polish resettlers from Biłka Szlachecka ended up in Grodziec; those resettled as minorities elsewhere were separated from important markers of Galician culture.

In minority villages, parental pressures often failed to prevent children's assimilation into the norms of the non-Galician majority. For instance, Michał Sobków recalled how his mother failed to convince his sisters to wear headscarves, a practice common in her Galician village of origin but unusual in the destination village, which was dominated by migrants from other regions (Maciorowski Reference Maciorowski2011, 15). In sum, in areas where they constituted the majority, the descendants of migrants from Galicia were more likely to follow and transmit group norms and values and to resist the temptation to adopt traits associated with other groups.

Conclusion

This study leverages a quasi-experiment of history that divided a homogeneous population into different types of communities – some in which Polish migrants from Galicia dominated and others in which they constituted a minority – to evaluate the role of community in the transmission of historically rooted values above and beyond the influence of the family. We find that respondents in majority and minority settlements are very similar to each other along a broad set of socioeconomic and geographic characteristics, but differ on the markers of historical Galician political values. Community composition thus matters for the persistence of cultural values. Where Poles from Galicia were resettled as a majority, traits associated with Austrian rule – religiosity, patriotism, and political participation – remain more prevalent today. On these traits, migrants' descendants in majority villages resemble the population of Galician villages that were not resettled after WWII. In contrast, in settlements where Poles from Galicia are a minority, these values are considerably weaker relative to both majority-Galician resettled villages and the more rooted villages west of the post-1945 Polish–Ukrainian border.

We do not seek to downplay the role of families in the value transmission process. Rather, given that family units remained intact in both majority and minority communities, we argue that, first, communities do play a role in the persistence of deeply rooted and slow-changing cultural values and, second, communities affect value transmission beyond and above the family. For reasons of costs and logistics we did not collect data on the nature of political values among non-Galician residents of majority and minority communities. Such data would be necessary to establish how well families do in value socialization when not buttressed by community support. Yet even in minority communities, Galician parents might have been reluctant to expend a great deal of effort on socializing their offspring because the majority was made up of other Poles, who speak the same language and practice the same religion. Further work would be needed to establish whether parents might be able to compensate for the absence of community reinforcement and aggressively attempt to socialize their offspring if they live in a context where the dominant majority is radically different from and/or openly hostile to the minority group, as Bisin and Verdier (Reference Bisin and Verdier2001) theorize.

Empirically, this study speaks to the conditions under which cultural persistence is more likely. We conclude that cultural values are less likely to endure once community bonds are broken either because of naturally occurring economic or social mobility or due to forced resettlement. Thus historical legacies may decay faster in cities, where community bonds are weaker, than in the countryside. Our findings also contribute to research on assimilation processes, suggesting that migrants are more likely to retain their culture when settled in an area that is densely populated with other families from their region or country of origin.

Supplementary material

Online appendices are available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000447.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted for excellent comments to Avital Livny, Edmund Malesky, Didac Queralt, Arturas Rozenas, Peter van der Windt, Tomasz Zarycki, Christina Zuber, and to seminar participants at George Washington University, Juan March Institute, NYU-Abu Dhabi, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Washington University in St. Louis. Dmitry Dobrovolskiy, Laura Moreno, Daniel Tobin and Anna Weissman provided stellar research assistance. This project was funded by NYU-Abu Dhabi and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Harvard University and NYU-Abu Dhabi.

Data availability statement

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XJB2Z8.