Among the abstractions beloved of political theorists, tolerance enjoys a special place. In recent years, few topics have received as much sustained attention across theoretical approaches, from the normative and analytic (Rawls Reference Rawls1999; Scanlon Reference Scanlon2003) to the historical (Bejan Reference Bejan2015, Reference Bejan2017; Murphy Reference Murphy2001) and critical (Brown Reference Brown2008; Mahmood Reference Mahmood2015). The same is true in political science. Since the publication of Samuel Stouffer's Communism, Conformity, and Civil Liberties (Reference Stouffer1955), tolerance has become ‘among the most investigated phenomena in modern political science’ (Gibson Reference Gibson2006, 21). Yet unlike deliberative democracy – on which some dialogue, however ‘aggravating’, has taken place (Mutz Reference Mutz2008, 522) – when it comes to tolerance, there has been little engagement across the empirical–theoretical divide.

This may be due to assumptions many on both sides share: namely, that political theory's contribution to the study of politics is essentially normative, and that there should be a strict division of scholarly labor between matters of ‘value’ and ‘fact’ (McDermott Reference McDermott, Leopold and Stears2008). But political theory can also be a crucial source of ‘ontological illumination’ offering insight not only into the should of politics, but the what (Mayhew Reference Mayhew2000). A classic illustration comes from the field of tolerance studies itself. The ‘least-liked’ measure developed by Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus (Reference Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus1982) drew directly on the theoretical work of Bernard Crick (Reference Crick1974, 70), who argued that the element of disapproval or ‘objection’ was constitutive of tolerance, so that one cannot be said to ‘tolerate’ something without it.

The ‘least-liked’ instrument is now among the most commonly used approaches to measuring tolerance. Nevertheless, since this early moment of cross-field fertilization, political theory and political science have rarely engaged.Footnote 1 We argue that both would benefit from renewed dialogue given today's resurgent conflicts of faith, class and culture. This article starts the conversation by bringing recent insights from political theory to bear on empirical work. We begin by illustrating how studies of tolerance in political theory and political science have diverged, along ontological and descriptive as well as normative lines.

Synthesizing recent theoretical developments, we then offer three concrete recommendations for empirical research. We call for more nuanced understandings of (1) the content and modes of difference (the objects of tolerance)Footnote 2 as well as the various grounds for objection to them and (2) the vast repertoire of possible responses to difference (the subjects of tolerance). Both are crucial for addressing limitations in the dominant approaches in political science; these typically use individuals' support for Western-style civil liberties as a proxy for tolerance, a measurement that may be problematic to apply to the study of tolerance in societies that are not liberal or democratic. Our third recommendation draws attention to (3) the ‘acceptance component’ and the sources of tolerance by asking a crucial question often neglected by empiricists: why do people tolerate at all?Footnote 3 What are their motivations for tolerating?

Next, we illustrate the value of our recommendations by testing them empirically. We designed and conducted three original experiments inspired by a problem central to historical toleration debates: conversion. Given the same cleavage type (religious or non-), are converts tolerated differently compared to nonconverts? For example, is a convert to radical Islam or atheism – or to secular movements and causes, such as the extreme left or right, or the anti-vaccine movement – more or less tolerated than a nonconvert? Our results suggest a marked ‘convert’ – or even ‘apostate’ – effect for contemporary religious as well as secular differences, with converts tolerated less than nonconverts across a variety of cleavage types. Those holding identical views or identities, in other words, were tolerated differently based on whether their differences were presented as fixed or changeable.

These results support our theoretical recommendations. First, they illustrate how richer ontologies of difference adapted from political theory can fruitfully inform empirical work when it comes to the objects of tolerance, particularly by acknowledging the dynamism of identities and other loci of difference today. If, as the results suggest, the grounds for objection can significantly affect tolerance judgments, then future experiments ought to take variation in the genesis and expression of difference into account. Secondly, our results confirm theorists' emphasis on the different subjects of tolerance, showing important variation in the range of ‘tolerant’ responses by individuals or institutions beyond support for civil liberties, from ‘minimal’ non-interference to more ‘maximal’ responses like respect and power-sharing. Thirdly, our experiments suggest avenues for future research into the ‘acceptance component’ highlighted by theorists by asking subjects what they think drives conversion as a mode of difference.

The results of our theoretically informed experiments also shed light on current controversies about what constitutes a ‘tolerant’ response to issues like immigration, transgenderism or even ‘transracialism’ (Tuvel Reference Tuvel2017). Liberal societies place a premium on individual freedom. Yet our results suggest that those seen as choosing to differ by converting to some disapproved position or identity will be less tolerated than those who simply are different. This suggests that conversion will continue to be relevant as a mode of difference, even or especially in liberal societies that valorize individual freedom and responsibility. While current empirical approaches do not generally encompass or explore such variation in the nature of and response to difference, our theoretically informed strategy suggests a way forward.

Finally, although this article focuses on bringing insights from political theory to bear on political science, we believe both sides have much to gain from dialogue. We touch on the benefits for theorists in the conclusion. In particular, we suggest that empirically informed work might provide an antidote to increasingly narrow and moralized understandings of tolerance now dominant in normative political theory. As the challenges of coexistence in the face of diversity intensify across the globe, we anticipate that the study of tolerance, both in theory and in practice, will require ever-greater interdisciplinary collaboration of the kind we pioneer here.

Empirical Assumptions

While the divergence between political theory and political science in the study of tolerance may not be surprising, given their different norms and objectives, it is nonetheless striking, particularly with regard to their ontological and normative assumptions. Since the 1950s, the empirical study of tolerance has developed along the track laid by Stouffer (Reference Stouffer1955). His work established the ‘pre-selected’ or ‘fixed’ measure of tolerance for use in surveys, in which respondents are asked the extent to which unpopular groups should be allowed to exercise civil liberties like holding public rallies and demonstrations.Footnote 4

Sullivan et al. (Reference Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus1982) famously contested this measure as conflating positive (or less negative) affect toward particular groups with ‘tolerance’ and ignoring the ‘objection component’ which, following Crick, they argued distinguish tolerance from more positive responses to difference like affirmation or acceptance. Their ‘least-liked’ approach asked respondents to identify and respond to the groups they disliked the most from a list of unpopular groups presented. A third approach simply asks respondents the extent to which they support policies that limit all citizens' civil liberties (Hetherington and Suhay Reference Hetherington and Suhay2011).

Political scientists continue to debate the relative merits of these three approaches.Footnote 5 Nevertheless, all three use measurements that emphasize support for a set of individual rights – of speech and association – tightly linked with Western-style liberal democracy. Although political scientists do not equate tolerance with support for civil liberties – indeed, Gibson (Reference Gibson2006) and others have noted the risks in conflating tolerance with liberal democracy – the dominant measurement strategy in the field creates this emphasis and neglects other aspects of tolerance that may be meaningful. Thus, while a rich literature has emerged addressing valuable topics such as the correlates and levels of tolerance and intolerance (Gibson Reference Gibson2008; Peffley and Rohrschneider Reference Peffley and Rohrschneider2003; Sullivan and Hendriks Reference Sullivan and Hendriks2009), the effects of situational context on tolerance judgments (Gibson and Gouws Reference Gibson and Gouws2001; Marcus et al. Reference Marcus1995; Nelson, Clawson and Oxley Reference Nelson, Clawson and Oxley1997) and the drivers and malleability of tolerance (Finkel Reference Finkel2002; Kuklinski et al. Reference Kuklinski1991; Mutz Reference Mutz2002), noticeable gaps remain.

Developments in Political Theory

Conceptual

Since the late 1960s, political theorists' interest in tolerance has been largely conceptual and analytic. The indelible impression left by theory on the empirical study of tolerance – in the form of the ‘least-liked’ measure – was of this sort. Still, two conceptual questions debated by theorists have scarcely registered among political scientists. First, is there a difference between ‘tolerance’ and ‘toleration’?Footnote 6 The uneasy consensus among theorists is to use the former to refer to an attitude, with positive connotations of acceptance or non-judgment, and the latter to refer to a practice or policy with the negative sense of ‘putting up with’ an acknowledged evil (Murphy Reference Murphy2001).

Second, theorists distinguish between the ‘horizontal’ dimension of toleration and the ‘vertical’, with the former describing a first-person or interpersonal practice, and the latter the state policies or institutional arrangements governing difference in society (Waldron and Williams Reference Waldron, Williams, Williams and Waldron2008). On this view, the individual rights of worship, speech and association enforced by a secular state, neutral between its citizens' ‘comprehensive doctrines’ (Rawls Reference Rawls1996), religious or non-, belong to the practical sphere of vertical toleration, and not the affective realm of horizontal tolerance. For theorists, the catchall language of tolerance used by political scientists runs together these attitudinal/practical and horizontal/vertical aspects, while the empirical focus on individual attitudes appears unduly narrow.

As we have seen, theorists have also done important conceptual work unpacking toleration into its constituent parts. These include the ‘objection component’ – the negative valuation many argue distinguishes ‘tolerance’ from acceptance or affirmation (Crick Reference Crick1974; Forst Reference Forst2003). Yet this position has come under pressure from those who think that negative toleration can (and should) transform into something more positive (Galeotti Reference Galeotti2002; Walzer Reference Walzer1997), or that objection is not necessary and a more permissive conceptual approach is required (Balint Reference Balint2017; King Reference King1976; Zagorin Reference Zagorin2003).

Theorists also highlight the ‘acceptance component’ of toleration – that is, the contravening reasons that counterbalance or overrule one's objections (Forst Reference Forst2003). For many, non-interference with a disapproved difference does not count as ‘toleration’ unless done for the right (that is, moral rather than pragmatic) reasons (Gardner Reference Gardner and Horton1993).Footnote 7 Many theorists also extend this moralizing approach to the objects of tolerance, insisting that objectionable differences must be changeable, so that the tolerated can be seen as responsible for them – making ‘racial tolerance’, for example, a kind of category mistake (Bellamy Reference Bellamy1997; Shorten Reference Shorten2005).Footnote 8 Thus, while empiricists have embraced the ‘objection component’, theorists have begun to ask deeper questions about the nature and necessity of objection, as well as what kinds of reasons for objection and acceptance distinguish toleration from other responses to difference.Footnote 9

Normative

Discussion of the reasons for objection and acceptance naturally raise normative questions. Where should one set the limits of objection and interference, respectively? Should our answers as private individuals and public citizens differ? Political theorists have long examined whether we have a duty to tolerate the intolerant and other ‘paradoxes of toleration’ (Forst Reference Forst2003; Rawls Reference Rawls1999). These discussions have intensified in response to debates about multiculturalism and ‘illiberal’ religious or cultural minorities living in liberal democracies (Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka1995; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor1994). Similar difficulties arise around hate speech (Bejan Reference Bejan2017; Waldron Reference Waldron2012). Should a tolerant society tolerate hateful speech? Or must it restrict the rights of racists or religious fundamentalists, in the name of tolerance itself?

In contrast with political scientists' normative certainty, recent years have seen growing normative dissatisfaction surrounding tolerance among political theorists. Following early critics like Thomas Paine and Goethe, some theorists question whether tolerance is really a virtue (Heyd Reference Heyd1998), and others whether toleration is a good thing at all. As a form of grudging sufferance or permission, they worry that toleration conveys an unmistakable whiff of contempt towards the tolerated while perpetuating asymmetries of power at odds with a genuinely inclusive and ‘well-ordered’ society. This disillusionment has been encouraged by a rising postcolonial sensitivity to tolerance as a discourse of power, and the way in which contrasts between the ‘intolerant’ East and ‘tolerant’ West function as civilizational justifications of Western empire (Brown Reference Brown2008; Mahmood Reference Mahmood2015).Footnote 10 For these critics, toleration serves to depoliticize difference and empower the sovereign (and ostensibly ‘neutral’ secular) state, rather than realize ‘a happy community of differences’ (Brown Reference Brown2008, 28).

These arguments present a serious challenge to the normative desirability of tolerance/toleration assumed in most theoretical and empirical accounts. In response, some theorists argue that critics conflate particular abuses of the ‘discourse’ of tolerance with the concept itself, while relying implicitly on its normative desirability in making their critique (Bowlin Reference Bowlin2016; Laborde Reference Laborde2017). Still others have responded by seeking to replace ‘mere’ toleration with something more robust, like multicultural recognition, equality or mutual respect (Galeotti Reference Galeotti2002; Gutmann and Thompson Reference Gutmann and Thompson2009; Nussbaum Reference Nussbaum2008), or by defining the concept of toleration itself more narrowly as a morally righteous response to difference (Forst Reference Forst2003; Gardner Reference Gardner and Horton1993).Footnote 11

The result has been much greater theoretical sensitivity to the variety of possible responses to difference. For instance, Forst (Reference Forst2003) develops a fourfold distinction between different conceptions of toleration – permission, coexistence, respect and esteem – based on context (the relative power of the subject and object of toleration) and the morality of the reasons for objection and acceptance.Footnote 12 As we discuss below, even if one rejects the moralizing tendency at work, such theoretical distinctions in the subjects of tolerance provide a helpful means of extending conceptualizations and measurements of tolerance in empirical political science, beyond the prevailing emphasis on support for civil liberties.

Bridging the Divide

Since their early moment of cross-fertilization, the theoretical and empirical literatures on tolerance have moved increasingly apart. To bridge the gap, we offer three broad recommendations for enriching empirical research with insights from political theory.

(1) The first concerns the objects of tolerance. While empirical researchers focus almost exclusively on objectionable ‘groups’, theorists speak of ‘difference’ as a broader phenomenon manifesting across groups, certainly, but also across individuals, ideas and practices, which can arise and be expressed in distinctive ways. The empirical focus on ‘group’ identity without differentiation risks conflating objects of tolerance. Thus, when survey respondents say they favor limiting the political expression of a group they dislike, it is not clear whether they judge the distinguishing feature of the group (the content of difference) to be offensive or the group's behavior (the mode of differing) (Mondak and Hurwitz Reference Mondak and Hurwitz1998). Likewise, some groups may be found objectionable no matter what they do, be it peaceful demonstration or violent protest (Gibson and Gouws Reference Gibson and Gouws2001). The group/individual distinction (Golebiowska Reference Golebiowska1995) is also crucial, as when a member of one's family or tribe who is gay may be tolerated, but not the LGBTQ+ community in general (or vice versa).

To account for this diversity, we recommend investigating both the content of difference and the mode of differing in more systematic ways. By ‘content’ we mean whether differences are, for example, religious, political, ideological, ethnic, racial, gender-based, or issue-based. By ‘mode’ we mean how those differences are generated (by birth, education or conversion) or expressed (through proselytism, cultural practices or public protest). The empirical focus on measuring levels and correlates of tolerance as a generalized attitude, akin to happiness or health, means that existing research does not delve into variations in the content of difference as often as one might expect. While recent work suggests that tolerance varies substantially by target group (Lee Reference Lee2013; Golebiowska Reference Golebiowska2014), it ignores what it is about different groups that leads some to be tolerated, and others not – and how this might reflect subjects' differing reasons for objection.Footnote 13

(2) Our second recommendation concerns the subjects of tolerance – both the agents of tolerance (be they individuals or institutions) and the attitudes, choices and behaviors they exhibit. We argue that the range of possible ‘tolerant’ responses to difference studied in empirical work must expand beyond the conventional civil rights-based approach in order to explore tolerance adequately outside of, as well as within, liberal democracies.Footnote 14 Debates in political theory provide a fruitful foundation by arranging ‘tolerant’ responses to difference along a continuum from minimal to maximal (Abrams Reference Abrams, Williams and Waldron2008; Creppell Reference Creppell2003; Forst Reference Forst2003). ‘Minimal’ responses might include indifference, resigned acceptance and other forms of non-interference, while maximal ones go beyond ‘mere’ tolerance of difference to more robust responses such as respect, recognition, mutual understanding and active support for civil liberties.

Other useful typologies of response to difference emerge from theorists' horizontal/vertical and tolerant/tolerationist distinctions. The former maps partially onto social versus political tolerance in the empirical literature, in that surveys of ‘political tolerance’ focus on attitudes toward the state interfering with the freedom of disliked others (such as to speak in public), while surveys of ‘social tolerance’ focus on attitudes toward citizens interfering (say, opposition to someone moving in next door). Yet theorists do not consider one of these ‘political’ and the other not. Indeed, both citizens and the state can limit freedom and suppress difference in politically meaningful ways, especially in democracies. As Gibson (Reference Gibson1992) suggests (following John Stuart Mill), an overlooked political consequence of intolerance ‘can be found in the constraints on political thought and action that citizens impose upon each other’ (339).Footnote 15

Tolerant responses to difference are clearly more varied and complex than the empirical literature suggests. We thus encourage empirical efforts to capture the minimal and maximal manifestations of tolerance suggested by normative theoretical debates surrounding the extent and kind of tolerance best for liberal and multicultural societies today. In addition, contemporary immersion in technology and social media suggest new and as yet under-theorized types of response to difference available to empiricists. For example, in what sense might cutting oneself off from those one disapproves of via social media or ‘safe spaces’ constitute a form of intolerance? Investigating a wider range of responses to difference is thus another potentially fruitful way of bridging the theoretical–empirical gap.

(3) Finally, the ‘acceptance component’ – here defined as the question of why people are motivated to tolerate – rarely appears in the empirical literature, even as political scientists recognize that tolerating one's enemies is counter-intuitive at best (Finkel Reference Finkel2003; Peffley et al. Reference Peffley, Knigge and Hurwitz2001). This neglect may stem from the ontological and normative assumptions outlined earlier. Indeed, it is typical to read that tolerance is important to study because it is good for liberal democracy (Gibson and Gouws Reference Gibson and Gouws2002, 46), with the suggestion that people are motivated to tolerate because of their broader commitments to that regime type.

This is limiting for two reasons. First, it means researchers lack the resources needed to investigate tolerance in authoritarian, hybrid, proto- or post-democratic regimes – precisely the contexts where efforts to promote tolerance may bear the most fruit (Marquart-Pyatt and Paxton Reference Marquart-Pyatt and Paxton2007).Footnote 16 Second, explaining the central motivation to tolerate in terms of a broader commitment to liberal democracy overlooks other possible motivations. Empirical researchers often follow J. S. Mill by justifying tolerance with reference to the marketplace of ideas (Stouffer Reference Stouffer1955; Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus Reference Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus1982). Yet political theorists have highlighted many other (moral and non-moral) reasons to tolerate (Sabl Reference Sabl, Williams and Waldron2008; Walzer Reference Walzer1997), the differential appeal of which in different cultural, economic and political contexts deserves greater empirical attention.

Finally, when it comes to teaching or promoting tolerance, its role in supporting liberal democracy will often not be the most appealing rationale. Empiricists should therefore investigate people's own reasons for tolerating difference and how these reflect or extend existing rationales in political theory, in order to understand which may be most useful in modifying tolerance in different contexts. Reorienting empirical research toward reasons for ‘acceptance’ (as well as ‘objection’) may thus also reveal the deeper and less morally edifying purposes tolerance may serve – including the perpetuation of asymmetries of power highlighted by critical theorists.

Putting Theory into Practice: The Case of Conversion

The experiments below focus primarily on the first of our three recommendations, concerning the objects of tolerance – and particularly the mode of differing – by turning to the example of conversion. As theorists note, when it comes to the kinds of difference for which we demand tolerance today, some (such as race) are expressed and/or interpreted as ‘given’ and fixed – by genetics, God or cultural upbringing – while others are seen as changeable and (often implicitly) the product of personal choice – as with political affiliation, or when a person converts to a new religion.

Conversion is a complex concept (Rambo and Farhadian Reference Rambo and Farhadian2014). Is it a binary process of converting from point A to point B? Or a more ‘crystalline’ process of transformation (Scherer Reference Scherer2013) in which multiple views and identities combine? Or is it something in between? How much choice is involved? These questions have been central to discussions of multiculturalism in political theory (Barry Reference Barry2001; Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka1995) as well as in the empirical literature on nationalism and political identity (Huddy Reference Huddy2001; Smith Reference Smith1998). But such complexities have important implications for tolerance, too, as varieties of difference beyond the static, largely one-dimensional groups favored by many empirical studies. Not only has religious conversion been at the heart of debates over toleration in the Christian and Islamic worlds for centuries, it remains so in much of the Arab Muslim world today (Sarkissian Reference Sarkissian2011).

Conversion can thus be a useful lens for examining contemporary questions of tolerance with the benefit of historical perspective. In contrast to the more rigid identities of the past, identities today are more fluid, allowing a greater role for self-authorship and personal choice (Baumeister Reference Baumeister1986; Frable Reference Frable1997; Thomson Reference Thomson1989). A heightened emphasis on ‘self-expression’ is connected to contemporary notions of modernity, freedom and democracy (Inglehart Reference Inglehart1997). Phenomena as diverse as immigration, multiculturalism, dual citizenship, transgenderism, transracialism, socio-political sorting and intersectionality all evoke questions of fluid, shifting or overlapping identities. Moreover, the extent to which a particular difference is understood as a matter of choice or something else – genetics, manipulation or the recovery and expression of a more ‘authentic’ identity – is itself subject to cultural, historical and geographical variation.

In the experiments our goal was simple: to test the hypothesis suggested by debates over toleration in political theory that the mode of difference matters. Specifically, we hypothesized that differences presented as chosen – as the dynamic product of free will embodied by the idea of a recent convert – would be associated with less tolerance than those presented as given, holding the content of the difference constant.

Experimental Design and Measurement

To test this hypothesis, we conducted three experiments across samples of US-based college students, ages 18–30, via Amazon Mechanical Turk, on the basis of several theoretical and methodological considerations.Footnote 17 First, we deliberately selected college samples to explore tolerance with scenarios on campuses, which have been flashpoints in recent discussions of tolerance and free expression. The campus setting was chosen to ensure subjects had some stake in the community of fellow students and flow of ideas within it. In addition, college-educated citizens represent a pool from which thought leaders may eventually emerge to lead, maintain institutions and influence others, as suggested by elite-based theories of democracy and political tolerance.Footnote 18 From a methodological perspective, studies also suggest the Mechanical Turk platform provides access to samples that, while different from nationally representative samples, behave similarly in experimental replications to subjects recruited in other ways (Berinsky, Huber and Lenz Reference Berinsky, Huber and Lenz2012; Krupnikov and Levine Reference Krupnikov and Levine2014). Finally, the demographics and political attitudes of younger Turkers better match nationally representative samples of younger people more generally (Huff and Tingley Reference Huff and Tingley2015).

The experimental design was similar in all three studies: after reading the scenario to which they were randomly assigned about either a convert or a nonconvert, subjects answered several questions about their attitudes toward the student in the scenario. To align with prior work, the key dependent variable – tolerance – was measured first in conventional, rights-oriented ways, using an index of five items, including ‘This student should be allowed to make a speech in our community’, ‘This student has the right to express any opinion he or she has’ and ‘This student should be banned from running for student government’ (reverse scored). Higher scores on the index indicate higher tolerance.Footnote 19 All respondents were also asked demographic questions, how the student in the scenario made them feel and how they viewed a number of groups in society, including those featured in the scenarios. Scenario texts and question wording can be found in online Appendix A.

While our first study focused on differentiating the objects of tolerance, in our second and third studies we turned attention to differentiating its subjects as well, by exploring broader ways of measuring ‘tolerant’ responses to difference beyond a strictly rights-based interpretation. Subjects were asked how they would behave toward the student in the scenario and others like him. The options drew from political theory, including a ‘minimally’ tolerant behavior limited to non-interference (‘avoid them’); ‘moderately’ tolerant behaviors emphasizing social and economic practice (‘be polite and kind to them’, ‘do business with them’, ‘let them do what they want in private’); and more ‘maximally’ tolerant ones touching on mutual respect, freedom and power (‘let them do what they want in public’, ‘try to understand their differing perspective’, ‘allow them to occupy positions of power in society’). Finally, to build knowledge about why converts may be less tolerable – that is, what motivates people to tolerate them less – subjects in Studies 2 and 3 were invited to tell us what they think drives conversion.

Study 1

In Study 1, subjects were randomly assigned to one of several potential scenarios of difference across religious, partisan and issue-based cleavages, as shown in Figure 1. Subjects in the ‘convert’ condition were asked to imagine that a student at their university wants to hold a public rally and demonstration on campus, with the student in the scenario described as a recent convert.

Fig. 1. Experimental design for Study 1.

To illustrate, in our issue-based scenario, students in the convert condition were given the following prompt: ‘Imagine that a student at your university has recently changed his mind and decided that vaccines are harmful to society. This student would like to hold a public rally and demonstration on campus in support of the anti-vaccine movement.’ By contrast, students in the ‘nonconvert’ condition were asked to imagine that a student at their university who believes that vaccines are harmful to society would like to hold a public rally and demonstration on campus in support of the anti-vaccine movement – with no suggestion of conversion.

Importantly, the content of the difference (being anti-vaccine) remained the same across the convert and nonconvert conditions. The other scenarios followed suit with students in the nonconvert condition asked to imagine a nonconvert, and students in the convert condition asked to imagine a convert (‘recently decided to become a Republican’, ‘recently converted to Islam’, ‘recently converted to Evangelical Christianity’ or ‘recently decided he is against all churches and religions’). These cleavages were selected either because they feature in prior work on tolerance (atheists, Muslims) or because we had reason to suspect, and subsequently confirmed with our results, that the target groups would be unpopular with our sample.Footnote 20

As Figure 2 illustrates (and Table 1 reports in more detail), respondents who imagined a convert to the anti-vaccine movement were significantly less tolerant of the student compared to those who imagined a nonconvert (p = 0.033), even though the content of the difference – being a member of the anti-vaccine movement – was identical. The same was true for respondents who imagined a convert to Islam, as opposed to a Muslim student (p = 0.067).

Fig. 2. Study 1, mean tolerance index by scenario and condition.

Table 1. Study 1, dependent variables by scenario and condition

Table shows means and standard deviations, along with mean differences, standard errors, p-values, and Cohen's d.

***p ≤ 0.001, **p ≤ 0.01, *p ≤ 0.05, ^p ≤ 0.10.

Both were small-to-medium size effects (Cohen's d = 0.42, 0.37) between a third and a half of a standard deviation in change in the dependent variable. To help place these effect sizes in context, converts were associated with a level of tolerance that was 6–7 percentage points lower than that for nonconverts with matching views. These changes are notable for being consistent in their magnitude with findings from other studies, including non-experimental ones. For example, Berggren and Nilsson (Reference Berggren and Nilsson2016) found that expansions of economic freedom in US states corresponded on average to a 6 percentage point increase in tolerance, while Djupe and Calfano (Reference Djupe and Calfano2012) found similarly sized increases in tolerance attitudes in subjects primed with inclusive religious values.

Finally, we found that the convert consistently made subjects feel more worried across all five scenarios, with the difference significant in the case of an Evangelical Christian convert (p = 0.043) and pooling across the five scenarios (p = 0.054). (The tolerance index, when pooling across the five scenarios, fell shy of statistical significance at p = 0.127, with the difference in the expected direction.) While respondents were also less tolerant of atheist and Republican converts, the difference was not statistically significant as it was for anti-vaccine and Muslim converts, as shown in Figure 2.

Why did the religious (Muslim) and issue-based (anti-vaccine) scenarios produce a statistically significant ‘convert effect,’ while the other scenarios did not? Partisan, religious and issue-based differences are theoretically distinctive, and the dynamics of conversion and implications for tolerance likely vary across cleavage types. For example, it is possible that conversions across broader varieties of difference are less threatening than specific issue-based ones due to greater potential for overlap, or because they are seen as less determinative of ultimate choices and behavior. These issues merit further study and underscore our larger point about the importance of variation in the objects of tolerance. The sample sizes may also have resulted in limited power in some of the scenarios. However, we suspect that the other scenarios were neither threatening enough nor uniformly disliked enough for many respondents to consider denying others their rights, which brings us to our next two studies.

Studies 2 and 3

In Studies 2 and 3, we applied a branching approach based on social identity theory (Tajfel et al. Reference Tajfel1971) so that respondents would be faced with opinions and identities likely to be opposed to their own, and we also rendered them more extreme. Social identity theory posits a natural tendency for people to think in terms of ingroups and outgroups, favoring the former and/or denigrating the latter. Although it features heavily in the prejudice literature, it has played a limited role in research on tolerance.Footnote 21

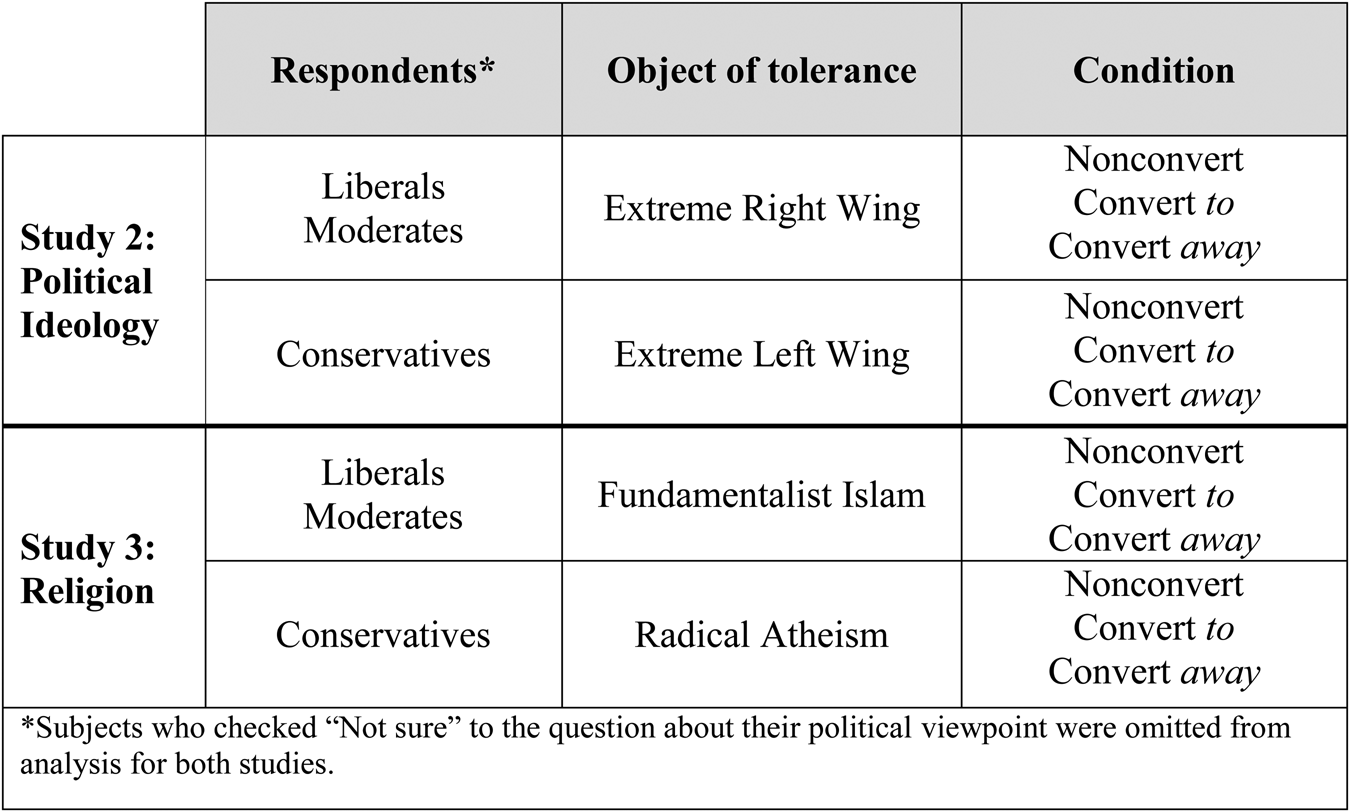

Study 2 focused on political ideological conversion. Conservatives in the convert condition were asked to imagine that the student in the scenario ‘used to be politically conservative’, yet ‘now adheres to extreme left-wing thinking’. By contrast, conservatives in the nonconvert condition were asked to imagine that ‘a student at your university adheres to extreme left-wing thinking’. Thus, the content of the difference (extreme left wing) again remained the same. Liberals and moderates received identical convert/nonconvert scenarios, except that the scenarios substituted ‘extreme right’ for ‘extreme left’ and, in the convert condition, described the student as having previously been politically liberal.Footnote 22 The convert was therefore described as deliberately adopting outgroup membership.

Study 3 turned to religious conversion. Due to the association between religiosity and conservative political views (Layman Reference Layman2001; Malka et al. Reference Malka2012), conservatives were branched to a radical atheist scenario, while liberals and moderates were branched to an extreme religious scenario due to greater secularism among them found in Study 1. We also continued to branch here on the basis of political ideology because today's heightened levels of political polarization (Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2014; Mason Reference Mason2018) make political identity, as compared to general levels of religiosity, an especially salient cleavage type driving ingroup/outgroup thinking. In addition, in an earlier large pilot study, the number of Mechanical Turk respondents who reported being conservative or very conservative was larger than the number of respondents indicating they were religious or very religious, thus suggesting that blocking on the basis of political ideology would lead to somewhat more balanced sample sizes, with larger statistical power. The small number of religious subjects in our sample also matches previous work on the limited religiosity of MTurkers (Lewis et al. Reference Lewis2015).Footnote 23

As a result, conservatives in the convert condition were asked to imagine that a student at their university ‘used to hold conservative views’, yet ‘now adheres to an extreme and radical form of atheism’. For liberals and moderates, the convert condition involved a student converting to ‘an extreme and fundamentalist form of Islam’, having previously held liberal views. As in the previous studies, in the nonconvert condition, the student was presented as a nonconvert (to radical atheism/fundamentalist Islam).

Studies 2 and 3 also expanded upon Study 1 by adding a third experimental group to each branching, as shown in Figure 3. Thus far the convert condition has involved a student converting to the outgroup defined as a different and potentially disliked identity, ideology or issue position, while the nonconvert condition involved a student who merely adheres to it. In Studies 2 and 3, a third group was added – a convert away from it to the presumed ingroup – in order to represent the ‘reverse convert’ condition.

Fig. 3. Experimental design for Studies 2 and 3.

Figure 4 displays the main findings on tolerance, and Table 2 reports all results. Strikingly, the data revealed remarkably consistent evidence of a ‘convert effect’ – or, perhaps more precisely, an ‘apostate effect’ – on tolerance across all four scenarios. Hence subjects were significantly more inclined to deny rights to converts to the extreme right (p = 0.023), extreme left (p = 0.089), fundamentalist Islam (p = 0.049) and radical atheism (p = 0.027) than to nonconverts whose given views were otherwise identical. As Table 2 shows, the results are especially notable for conservatives in the extreme left and radical atheism scenarios, given that their numbers were relatively low.

Fig. 4. Studies 2 and 3, mean tolerance index by scenario and condition.

Table 2. Studies 2 and 3, dependent variables by scenario and condition

Table shows means and standard deviations, along with mean differences, standard errors, p-values, and Cohen's d.

***p ≤ 0.001; **p ≤ 0.01; *p ≤ 0.05; ^p ≤ 0.10.

These effects were similar in size to those in Study 1, except for conservatives branched to the radical atheism scenario where the reduction in tolerance associated with the convert to condition (compared to the nonconvert condition) was two to three times greater in magnitude (a 16 percentage point drop). The results also show that the convert made subjects significantly more uncomfortable in both the extreme right (p = 0.009) and radical atheist scenarios (p = 0.08).

Additional Analysis

What of those who convert away from these points of view? Both the long history of religious conversion and social identity theory suggest that ingroup-to-outgroup conversion should be less tolerable than outgroup-to-ingroup conversion, so much so that it may seem debatable whether tolerance is at issue in the latter case at all. However, recent converts even to one's own ingroup can provoke suspicion. For example, Jensen (Reference Jensen2008, 401) illustrates how ethnic Danes who convert to Islam may be labeled by the Muslim immigrant community in Denmark as ‘the wrong kind of Muslim’.

Nevertheless, we found strong evidence that ‘converts away’ – across all four scenarios in Studies 2 and 3 – are significantly more tolerated than either nonconverts or ‘converts to,’ as online Appendix D's regression results show (and Figure 4 also shows graphically). While these results are not surprising, they underscore important questions not only about the directionality of conversion, but also its potential for multidimensionality. After all, individuals may convert to an ingroup or otherwise ‘liked’ position in one sense yet remain part of an outgroup or ‘disliked’ perspective in another. Although recent work on identity emphasizes such elements of complexity and intersectionality (Rocca and Brewer Reference Rocca and Brewer2002; Birnir Reference Birnir2007; Jones Reference Jones2017; McCauley Reference McCauley2017; Mason Reference Mason2018), the implications for tolerance judgments are not well-understood.

The main analysis focused on the conventional tolerance index. As shown in Table 3, which pools results by study, respondents were generally less tolerant of converts along the broader set of minimal-to-maximal measures drawn from political theory, as well, with some suggestive variation. In both Studies 2 and 3, subjects were less inclined to share power, form friendships and seek understanding with converts (‘maximally’ tolerant behaviors, p = 0.068, 0.009). They were also less inclined to forgive them, be polite to them and do business with them, among other ‘moderately’ tolerant behaviors underscoring social and business practice (p = 0.016, 0.003).

Table 3. Pooled findings for study 2 (Ideology) and study 3 (Religion)

Table shows means and standard deviations along with mean differences, standard errors, p-values and Cohen's d.

***p ≤ 0.001; **p ≤ 0.01; *p ≤ 0.05; ^p ≤ 0.10.

However, on minimal tolerance – avoidance – they differed. In the case of political ideological conversion (Study 2), respondents were significantly more inclined to avoid a convert (p = 0.004), but in the case of religious conversion (Study 3), they were not. This is an intriguing result. It may be that avoiding a political or ideological convert is more socially acceptable than avoiding a religious one, at least in secular liberal-democratic contexts. Political theorists often note that religious claims of conscience are more tolerated than secular ones (Laborde Reference Laborde2017; Leiter Reference Leiter2014). Thus, subjects may have felt that avoiding a religious convert would be intolerant, while avoiding a political one is not.

Moreover, avoidance – based on the principle of non-interference – may be a more ambiguously ‘tolerant’ response to difference than initially suspected. Avoidance is more tolerant than active interference, such as violently opposing one's enemies, and in that sense is a minimal form of tolerance, perhaps akin institutionally to the Ottoman Empire's ‘millet’ system. Yet avoidance may also suggest intolerance, particularly when it can be understood as ‘interfering’ in some other sense, as for example with the free flow of ideas as critics of ‘safe spaces’ on college campuses charge. Either way, the prospect of secular-political conversion appeared to affect respondents more profoundly than religious conversion, with the former triggering an avoidant response deserving further study.

But why did our subjects generally find converts less tolerable overall – not only Islamic, radical Islamic and radical atheist ones, but also converts (or ‘apostates’) to the extreme left and extreme right, to say nothing of converts to the anti-vaccine movement? Put another way, why tolerate nonconverts, when their views are the same?

This question touches on the third of our recommendations emphazing the ‘acceptance component’ of tolerance. Our qualitative data provide some valuable hints. When subjects were asked why the student might have converted to the new perspective – in the ‘convert to’ condition – the top reasons given emphasized emotions, such as frustration and anger; persuasion by others; and deliberate agreement with the new perspective (online Appendix E). For example, respondents might suspect a convert of being less rational or coherent. More broadly, it may be that converts (as opposed to long-time adherents) bring especially alarming prospects to mind, including the dominance of emotion over reason, those on the ‘wrong side’ acquiring committed members who strongly agree with the cause, and successful proselytizing or recruitment by one's enemies.

This explanation for lessened tolerance for converts would support critical theorists who see tolerance primarily in terms of power. Thus, the nonconvert case may reflect Forst's ‘permission’-style conception of tolerance, in which respondents magnanimously allow alternative viewpoints to exist – so long as the respondents' own superior social position remains secure and the tolerated difference narrowly circumscribed. Yet the convert signals a possible change in the status quo, with the alternative viewpoint attracting followers and thus growing in power relative to the respondent. If tolerance depends on asymmetric power relations, as Brown (Reference Brown2008) argues, then it makes sense that the former should be more tolerable than the latter, despite their identical views.

A related possibility is that converts are seen as ‘responsible’ for their objectionable viewpoints compared with nonconverts, and so may be viewed as less deserving of tolerance. Theorists of multiculturalism have long debated the importance of individual choice, suggesting that the liberal state has a responsibility to address inequalities that result from ‘unchosen’ circumstances, including economic starting points and – more controversially – minority cultural membership (Barry Reference Barry2001; Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka1995). Nonconverts may be viewed as ‘unlucky,’ having been born into an objectionable way of thinking through no fault of their own, and so less responsible for their views. Converts, however, might be viewed as having deliberately chosen their objectionable views – an act others may feel correspondingly less obligated to tolerate, especially in liberal cultures that emphasize individual responsibility.

Here, we return to the salience of different reasons for objection. In our samples, religious conversion was seen as driven more by emotion, while political conversion was viewed as driven more by persuasion and strong agreement with the cause. This suggests a possible reason why political conversion may have provoked a stronger avoidant response than religious conversion. The former may be viewed as a deliberate decision, for which converts must be held responsible, while the latter may be seen as a more ‘emotional’ and less rational choice. This would again suggest important differences in the nature of conversion by cleavage type, and the need for further empirical research into the relationship between different logics of objection and acceptance.

Summary

Although our experiments naturally cannot address all of the concerns raised in our earlier theoretical discussions, they illustrate empirically and powerfully the value of deeper collaboration across political theory and political science along the lines we suggest. Following our recommendations, the experiments focus on (1) more nuanced understandings of how difference is generated and expressed by way of conversion, while also touching on (2) the subjects of tolerance who may respond in different (more minimally or maximally tolerant) ways based on (3) their reasons for and logics of acceptance.

As predicted, the mode or way of differing – as one type of variation in a more expansive and theoretically informed ontology of difference – can indeed matter for tolerance judgments and responses across a variety of cleavage types, from issue-based to political ideological and religious, despite the content of the difference remaining the same. Further empirical work should seek not only to replicate and extend these results with additional samples, but to explore other types of variation in the nature of and response to difference, including the public/private, horizontal/vertical, tolerant/tolerationist, attitudinal/practical and speech/deed dimensions highlighted by theorists.

Finally, our experimental findings of a ‘convert effect’ are provocative in their own right. They suggest that conversion is salient as a mode of difference beyond the religious context, raising important questions about the possibility of secular apostasy. For example, if people generally find conversion more threatening than non-conversion, then this would help to crack one of the persistent ‘enigmas of tolerance’ – threat as an unexplained variable (Gibson Reference Gibson2006). Importantly, Western liberal democracies place a high premium on self-expression and personal freedom. But if citizens are less likely to tolerate those they see as choosing to be different along disliked or controversial lines, then they lack precisely the tolerance that liberal democracy prides itself on. One's effective freedom to differ – that is, to differ or disagree by choice – declines accordingly.

Conclusion

Reopening the dialogue on tolerance between political scientists and political theory is long overdue. In this article, we have sought to move beyond the ‘pattern of competitive distrust’ dividing theorists and empirical political scientists and bridge the growing theory–empirical divide (Marcus and Hanson Reference Marcus and Hanson1993, p. xv). To do so, we drew from recent political theory to propose three new directions for empirical research, which emphasize (1) the objects of difference, including the ways in which difference is generated and expressed, (2) subjects' responses to it and (3) the sources or reasons for tolerance (the ‘acceptance component’).

We also demonstrated the promise of greater cross-disciplinary collaboration along the lines we suggest. The problem of conversion represents just one example of variation within the richer, more adaptive and dynamic ontology of difference and responses to it that contemporary conditions of intensifying globalization and multiculturalism demand. Our work raises the possibility that conversion may be as threatening a mode of difference in liberal democratic contexts that privilege personal freedom in the construction of identities as in ‘illiberal’ religious regimes that do not. Indeed, we have provided suggestive evidence that those seen as choosing to differ across issues and politics as well as religion can attract significantly less tolerance than those seen as ‘merely’ different. Not only does this apparent rebuke of individual freedom and agency suggest further avenues for comparative, cross-national work on tolerance, it also demonstrates how engagement with political theory can open up conceptual and interpretive possibilities for such work.

Although our focus in this article has been to bring theoretical insights to bear on empirical research, political theorists also stand to benefit from dialogue with an empirical literature with which many are unfamiliar. In recent years, theorists' understanding of the complicated relationship between theories and practices of toleration has benefitted greatly from their increasing engagement with social and intellectual historians (Bejan Reference Bejan2017; Forst Reference Forst2003; Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka and Heyd1998; Murphy Reference Murphy2001; Walzer Reference Walzer1997). Greater engagement with the concrete, practical challenges of tolerance studied by political scientists today would be equally beneficial, particularly when it comes to understanding the persistence of ‘negative’ affect in the encounter with difference – even in the secular and multicultural liberal democracies many theorists see as ‘beyond’ toleration. Similarly, the wide range of responses to difference and reasons for acceptance captured by empiricists offer a much-needed corrective to the ‘profound moralizing tendency’ of recent normative work determined to construe toleration ever more narrowly (Zuolo Reference Zuolo2013, 219), even as the everyday challenges of unmurderous coexistence in our own liberal democratic societies increase (Balint Reference Balint2017; Bejan Reference Bejan2017).

As political theorists and political scientists continue to contemplate the demands of tolerance in theory and practice today, further dialogue along the lines we pioneer here promises to reveal embedded assumptions while pointing toward richer research agendas inspired by and adequate to the dilemmas of tolerance in our own times.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets are available at Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HWJI6N and online appendices at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000279.