In 2016, populist movements swept across the globe. Most prominently, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union and the United States elected Donald Trump president. Although there are certainly many reasons for these outcomes, the success of these populist campaigns have been seen, at least in part, as a rejection of global economic integration. One argument that was repeatedly used as a justification for rejecting integration is that other countries are behaving unfairly, and, as a result, that new restrictions are needed on the flows of people, goods and capital.Footnote 1 For example, Donald Trump repeatedly argued on the campaign trail that retaliations against China are needed because its trade and investment practices are unfair. In other words, Trump not only tried to appeal to voters by arguing that new restrictions on trade and investments from China may improve their economic prospects, but also that reciprocity requires them.

Although a growing body of international political economy (IPE) scholarship has studied why individuals form preferences toward trade, immigration and international investment, this literature has largely ignored whether the policies other countries adopt influence individual attitudes. Instead, this literature has primarily examined how economic and socio-cultural factors affect public opinion.Footnote 2 For example, one strand of this scholarship has found that economic factors – like an individual’s skill set, employment sector or asset holdings – are often highly correlated with views on trade and immigration.Footnote 3 Another strand has found that socio-cultural factors – such as nationalism, outgroup resentment and cosmopolitanism – are also highly correlated with views on these topics.Footnote 4 Little research, however, has examined the extent to which the desire for reciprocity influences views on IPE.Footnote 5

In this article, we provide evidence that reciprocity is an important determinant of public opinion in one area of IPE: the regulation of foreign direct investment (FDI). Reciprocity, in this area, is the idea that policy makers can encourage other countries to open their markets to investments by permitting or restricting FDI. Government officials understand this concept. For example, former Secretary of Commerce Elliot Richardson explained that it is important for the United States to welcome FDI because ‘[i]t is patently impossible to open doors for American business abroad while we slam shut the doors to foreign business in our own country’.Footnote 6 Not only are government officials aware of the importance of reciprocity, it has driven the adoption of US policies on FDI: the United States’ process for regulating foreign investment emerged from concerns about the influx of FDI from Japan at a time when it maintained policies that denied reciprocal market access.Footnote 7

But despite the ample evidence that reciprocity has been a major driver of FDI policy in the United States and other countries, it has received little theoretical attention from IPE scholarship. Over the last two decades, a growing body of IPE research has sought to understand why countries regulate FDI.Footnote 8 Given that a major finding of that literature is that regulations on inward FDI are based on domestic political considerations, it is not surprising that a related line of scholarship has emerged studying the determinants of public support for inward FDI flows.Footnote 9 These studies have focused, however, on using public opinion data and surveys to evaluate how skills and economic position influence individual support for inward foreign investment.

To our knowledge, scholars have not yet evaluated whether reciprocity influences public support for restrictions on FDI flows. But there are good reasons to believe that it would. For one, foundational research in international relations has long theorized that reciprocity can play an important role in international affairs in inducing co-operative behavior.Footnote 10 This logic may lead individuals to believe reciprocity is important to ensuring that foreign governments provide access to their markets. Alternatively, recent research has shown that reciprocity can be an important driver of individual foreign policy preferences.Footnote 11 This research has built, in part, on findings from psychology and behavioral economics suggesting that individuals care deeply about fairness, and thus are likely to respond positively to others who behave co-operatively and to punish those who behave unfairly. This suggests that an important driver of individual support for foreign investments may be whether the potential investments are from countries that allow reciprocal investments. In other words, people might not only care about how the investment could affect their economic or physical security, but also whether they think that allowing it is fair.

In order to evaluate the effect of reciprocity on public opinion toward inward FDI, we fielded a series of survey experiments in the United States and China. We conducted two experiments to both a nationally representative sample of 2,010 adults in the United States and a stratified sample of 1,659 adults in China, and performed a third follow-up experiment to a sample of 838 respondents recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service. Our primary experiment used a conjoint design that allowed us to directly compare the relative influence of reciprocity and a number of factors previously theorized to drive opposition to foreign investments. This experiment asked respondents whether the government should block a series of hypothetical acquisitions of domestic firms by foreign companies. Our second and third experiments focused on positive and negative reciprocity by asking respondents how they thought their government should respond to one of several changes that a foreign country could make to its inward investment policies.

The results of these experiments suggest that reciprocity is an important determinant of public opinion on the regulation of foreign investments. In both the United States and China, respondents were consistently more likely to oppose foreign acquisitions when the foreign firm’s home country did not provide reciprocal market access. More specifically, in our conjoint experiment, American respondents were 16 percentage points – and Chinese respondents were 19 percentage points – more likely to oppose a potential acquisition when the foreign firm’s home country prohibited market access. We also found suggestive evidence that respondents may be more supportive of punishing negative reciprocity than they were of rewarding positive reciprocity.

BACKGROUND

Reciprocity and the Regulation of FDI

China has recently made the importance of reciprocity to FDI policy a salient issue. Despite being one of the largest sources of outward FDI,Footnote 12 China heavily restricts inward FDI. Data compiled by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) suggests that China has more restrictions on inward FDI than any other OECD or other major emerging economies such as Brazil, Russia, and India.Footnote 13 This lack of reciprocity in FDI policy has emerged as a major source of friction between China and other countries. A 2016 Brookings Institution report even argued that the ‘lack of reciprocity between China’s investment openness and the US system is the most worrisome of the trends’ in investment between the two countries.Footnote 14

This concern over a lack of reciprocity is not new; China simply provides the most recent example of this phenomenon. Concerns over reciprocity have long been identified as a major driver of investment policy in the United States and other countries.Footnote 15 For example, the restrictions that the United States places on foreign investments were developed in the 1980s in response to apprehensions over the rise of investment from Japan when it was not open to reciprocal investments from America.Footnote 16 As one scholar wrote, ‘the largest underlying cause of friction over Japanese FDI in the 1980s was the perception that, while the United States was wide open to Japanese investment and imports, US firms faced substantial barriers to investment and trade in Japan’.Footnote 17

There have even been proposals to base US investment policies explicitly on the principle of reciprocity. For example, Prestowitz argued that the United States should restructure regulations on foreign investments to give foreign firms only the access and protections that their home countries provided to American firms.Footnote 18 A bill enshrining this proposal has been repeatedly introduced in the US Congress,Footnote 19 and US policy toward some industries has explicitly incorporated reciprocity requirements.Footnote 20

IPE Scholarship on the Regulation of FDI

Despite the evidence that reciprocity influences the regulation of FDI, it has not been a major topic of IPE research. Over the last two decades, a growing body of scholarship has examined the regulations that countries place on FDI flows.Footnote 21 More specifically, this literature has studied why countries either adopt policies to encourage inward FDI flows – like providing tax holidays – or policies to restrict inward FDI flows – like restricting foreign acquisitions of domestic firms.Footnote 22

These articles have primarily examined the economic and non-economic factors that influence whether countries encourage or restrict inward FDI. For example, Pandya argued that democracies adopt fewer restrictions on inward FDI because the general public favors these policies due to their positive effect on wages. According to Pandya, autocratic regimes, however, are less willing to liberalize because they are more responsive to the preferences of local firms that want to prevent competitors from entering their market.Footnote 23 In related research, Owen argued that labor unions opposed to inward FDI use their political power to block it in their industries.Footnote 24 To support this argument, Owen presented evidence from nineteen developed countries suggesting that high unionization rates are associated with greater restrictions on inward FDI. Other studies have examined whether restrictions on inward FDI are based on security considerations. Graham and Marchick reviewed controversial attempts by foreign firms to acquire American companies and concluded that, although those opposed to acquisitions often invoked national security concerns, their motivations were primarily economic.Footnote 25

These studies have primarily used observational data, but a few studies have examined the determinants of individual attitudes toward FDI.Footnote 26 For instance, Scheve and Slaughter found that British workers in high-FDI industries perceived themselves as having less job security.Footnote 27 In another study, Pandya used public opinion data from eighteen Latin American countries to show that individual preferences toward FDI are a function of its distributional effects on income.Footnote 28 Relatedly, Kaya and Walker analyzed public opinion data from thirty-two countries and found that respondents who had completed higher education or were employed in the private sector were less likely to think that large multinational corporations hurt local business.Footnote 29 Additionally, two recent working papers have used survey experiments to explore attitudes toward FDI. Jensen and Lindstädt conducted surveys in the United States and the United Kingdom to examine public support for FDI. They found, among other things, that the home country of the foreign investment is a major determinant of levels of opposition.Footnote 30 Zhu found that Chinese attitudes toward investment in high-skilled and low-skilled sectors differ, and that individual characteristics are an important predictor of attitudes toward both types of FDI.Footnote 31

Although this body of literature has gone a long way toward explaining why countries may either encourage or restrict FDI, only a handful of articles have considered how reciprocity influences FDI policies. For example, Crystal argued that one reason American firms have not lobbied hard for the US government to restrict FDI flows is that these firms profit from other governments not restricting inward investments.Footnote 32 Additionally, Tingley et al. found that one factor that predicts which attempted acquisitions of American companies by Chinese firms are met with political opposition is whether China restricts investments in the same industries.Footnote 33

Why Reciprocity May Influence Public Opinion on FDI

Although reciprocity has not played a major role in scholarship on the regulation of FDI, scholars have long understood that reciprocity plays an important role in international relations.Footnote 34 Perhaps most notably, Keohane argued that reciprocity is fundamental for explaining state behavior because it can allow ‘cooperation to emerge in a situation of anarchy’.Footnote 35 The basic reason is that, even without hierarchical power structures, states can influence the actions of other states by reciprocally punishing or rewarding them.

Reciprocity has not only been used to explain international relations generally, but also specific areas of IR scholarship. For instance, reciprocity is a critical part of international trade policy.Footnote 36 Indeed, scholars have argued that reciprocity has driven US trade policy since WWII.Footnote 37 Further research has also shown that reciprocity plays an important role in security policy.Footnote 38 Goldstein and Freeman argued that the interactions between the United States, the Soviet Union and China during the Cold War can be best explained in terms of strategic reciprocity.Footnote 39 In another example, Morrow found that reciprocity largely explains compliance with the laws of war.Footnote 40

Scholars have only recently begun to examine whether reciprocity might influence individual attitudes about international relations. Some research is informed by standard rational choice accounts of reciprocity’s role in conditional co-operation.Footnote 41 Other research has built on findings from psychology and behavioral economics showing that individual behavior may deviate from traditional rational choice models.Footnote 42 One of these deviations is that, even when they have to forgo individual gains to do so, concern for equality and fairness may lead individuals to reward or punish others for ‘pro-self’ behavior. For example, individuals playing an ultimatum game in a lab may reject offers they view as unfair even though it means leaving money on the table.Footnote 43 Although this line of scholarship has suggested that people may forgo individual gains to reward altruistic behavior, ‘[t]here also seems to be an emerging consensus that the propensity to punish harmful behavior is stronger than the propensity to reward friendly behavior’.Footnote 44

Drawing on these insights, a handful of articles have tested whether concerns about reciprocity influence foreign policy preferences.Footnote 45 Kertzer et al., for instance, studied how moral sentiments influence views on foreign policy and found that beliefs about fairness and reciprocity are a particularly important predictor of attitudes toward international relations generally. Similarly, Kertzer and Rathbun found that fairness concerns influence how participants in the lab behave in scenarios developed based on bargaining situations central to IR theory.Footnote 46 Additionally, both Tingley and Tomz, and Bechtel and Scheve found that reciprocity could affect attitudes toward climate change policy,Footnote 47 and Chilton found evidence indicating that reciprocity influences public support for complying with international legal obligations during interstate conflicts.Footnote 48

To our knowledge, previous public opinion research on individual support for investment flows has not directly tested whether the general public is concerned about reciprocity. The recent research on the role of reciprocity on foreign policy preferences, however, suggests that the policies other countries adopt should directly influence whether individuals are supportive of allowing foreign investments. In other words, even though at least some research has suggested that outward FDI decreases domestic wages and employment levels,Footnote 49 concern for fairness should make individuals want to punish countries that do not allow their own country’s firms to enter their markets. This research also suggests that the desire to punish foreign countries for denying market access should be stronger than the desire to reward foreign countries for opening their markets.

EMPIRICAL APPROACH

Research Method

For a combination of substantive and methodological reasons, we chose to use survey experiments to research the relationship between reciprocity and support for restrictions on FDI. The first substantive reason is the strong relationship between democratic regimes and FDI flows. Existing evidence indicates that democracies attract more inward FDIFootnote 50 and impose fewer restrictions on inward FDI.Footnote 51 Since democracies are responsive to the concerns of the electorate, understanding whether the public cares about reciprocity is important for understanding how reciprocity influences FDI policy. Secondly, the returns on investments made by foreign multinational corporations are affected by how the public perceives a firm’s legitimacy.Footnote 52 Understanding the sources of opposition to foreign investments is thus important for understanding investment patterns. Finally, despite the fact that a substantial body of research has examined public opinion regarding various international flows – like the flow of goods,Footnote 53 foreign aidFootnote 54 and people across bordersFootnote 55 – there has been comparatively little research on public attitudes toward FDI flows.Footnote 56 Using survey experiments allows us to bring FDI flows into the discussion of public opinion on IPE more generally.

There are also two methodological reasons that survey experiments are an appealing way to study the relationship between reciprocity and support for restrictions on FDI. First, since reciprocity likely correlates strongly with other factors that drive opposition to FDI, it is difficult to isolate the effect of reciprocity on opposition to FDI using observational methods. For example, there has been opposition to the surge in inward FDI from China in the United StatesFootnote 57 and in Europe,Footnote 58 but that surge happened at the same time that those economies experienced downturns. Using observational data, it is thus difficult to tell how much of the opposition is due to resentment that China heavily restricts inward FDI flows and how much is due to the perception that Chinese firms are taking advantage of a weak economy.Footnote 59 Using survey experiments, however, it is possible to estimate the effect of reciprocity on opposition to inward FDI flows by varying levels of reciprocal market access while holding other features of the transaction constant. Secondly, there are ways to design survey experiments – like the conjoint design we use – that make it possible to simultaneously test the effects of many treatments. Although our primary interest is the effect of reciprocity, as we discuss below, a number of other factors have also been hypothesized as driving opposition to FDI.Footnote 60 Our research design allows us to estimate the relative effect of reciprocity compared to other features of foreign investments that may drive political opposition.

There are, of course, limitations to using survey experiments to study the influence of reciprocity on public opinion. For example, if a survey experiment asks participants about their reactions to foreign countries’ policies based on a reported static state of affairs (for example, ‘country X has recently opened/restricted market access’), it may not accurately capture the temporal component of reciprocity. That is, in this case, reciprocity is about individual attitudes evolving in response to changes in policy over time, not reporting their current position after being informed of news. This may bias survey experiments towards finding an effect by failing to capture the ways in which the evolution of policy over time may attenuate reactions. Also, survey experiments largely have research designs that rely on stated preferences. Respondents may respond strongly in a survey, but not hold their view strongly enough to translate it into action.Footnote 61

Case Selection

We focused on one type of foreign investment, mergers and acquisitions (M&As),Footnote 62 in part because we believe that focusing on a specific type of investment is likely to generate more concrete views than simply asking respondents about attitudes towards foreign investments generally. Given our decision to focus on a specific type of investment, we chose to focus on M&As because we believe they are more likely to generate political opposition. Moreover, prior observational research has examined factors that influence political opposition to M&As,Footnote 63 which provides us with alternative hypotheses to test.

We fielded our survey in the United States and China for three reasons. First, these two countries are the world’s two largest recipients of inward FDI.Footnote 64 Thus these are the two countries in which it is arguably most important to understand opposition to foreign investment. Secondly, the United States is a democratic country that has relatively low barriers to foreign FDI, whereas China is an autocratic country that has relatively high barriers to foreign FDI. Since prior research has consistently found differences in openness to FDI between democratic and autocratic countries,Footnote 65 examining the United States and China allows us to test whether our findings are consistent across both regime types. Thirdly, since the United States and China have spent years negotiating a Bilateral Investment Treaty that would increase the reciprocal protections afforded to foreign investors,Footnote 66 research on public opinion in these two countries has the potential to influence an important current policy debate.

Alternative Determinants of Support for FDI

Although our principle focus is on reciprocity, other factors may influence opposition to foreign acquisitions of domestic firms. As a result, we also tested other factors that have been shown to drive opposition to FDI.

First, we examined the effect of the Country of origin of the foreign firm. Previous research has found that public attitudes towards a range of international economic activities change based on the foreign countries involved. For example, Jensen and Lindstädt found that American respondents’ openness to foreign investments depended on those investments’ country of origin.Footnote 67 Relatedly, both Strezhnev and Umaña, Brenauer, and Spilker found that support for preferential trade agreements changed based on whether the country was a democracy or autocracy.Footnote 68 Finally, Li and Vashchilko showed that bilateral FDI flows were affected by national security concerns.Footnote 69 We thus tested whether opposition to foreign acquisitions of domestic companies changes based on whether the foreign firm was from China, Japan or Saudi Arabia;Footnote 70 whether a country is democratic or not; or whether a country is a security or economic threat.

Secondly, we examined the effect of the type of Ownership of the foreign firm. Previous research has suggested that American politicians are more likely to oppose foreign investments from state-owned enterprises.Footnote 71 This is perhaps because acquisitions by state-owned enterprises are more likely to be viewed as negatively affecting economic or national security.Footnote 72 As a result, we tested whether opposition towards foreign acquisitions of domestic companies changes based on whether the foreign firm was ‘privately owned’ or ‘government owned’.

Thirdly, we examined the effect of the domestic firm being in an industry that is sensitive for national security reasons. The primary way that a foreign acquisition of an American company can legally be blocked in the United States under a review process that regulates foreign investments is if the transaction poses a risk to national security.Footnote 73 Moreover, previous research has shown that American politicians are more likely to oppose specific transactions when the target firm is in an industry that is important to national security.Footnote 74 We therefore tested whether opposition towards foreign acquisitions of domestic companies changes based on whether the foreign firm was in an industry that posed a ‘low’ or ‘high’ risk to national security.

Fourthly, we examined the effect of the Firm Size of the target firm. It would be reasonable to believe that opposition to foreign acquisitions would be higher for large target firms with national profiles. This could be the case, for example, if those firms are seen to be particularly important for the country’s economic security or national identity. Relatedly, previous research has shown that American politicians are more likely to block specific transactions when the target firm has a value of over $200 million.Footnote 75 We therefore tested whether opposition towards foreign acquisitions of domestic companies changes based on whether the target firm was a ‘small company based in your area’ or a ‘large Fortune 500 company’.

Finally, we examined the effect of the target firm’s industry being in Economic Distress. It has been theorized that opposition to foreign acquisitions of domestic firms is likely to be greater when the domestic firm has experienced an economic downturn relative to the rest of the country.Footnote 76 Moreover, research has shown that American officials have blocked transactions when the targeted firms are in industries experiencing economic distress and high rates of unemployment.Footnote 77 We therefore tested whether opposition towards foreign acquisitions of domestic companies changes based on whether the target firm is in an industry that has ‘lower’ or ‘higher’ rates of unemployment than the national average.

PRIMARY EXPERIMENT

Subject Recruitment

Our primary experiment was conducted using an online survey administered to respondents recruited by Survey Sampling International (SSI). SSI conducts surveys for corporate and academic research in over 100 countries. We first administered our experiment to a sample of 2,010 adults from the United States. This sample was nationally representative of the adult population of Americans based on gender, age, ethnicity and census region. We subsequently administered our experiment to a sample of 1,659 adults from China that was stratified to reflect the Chinese population’s gender, age and region. The surveys were administered two weeks apart in February 2015.Footnote 78

Survey Design

Our primary experiment used a conjoint design. Conjoint analysis is a marketing tool that has recently started to be used in political science.Footnote 79 It presents respondents with a profile or vignette in which multiple attributes are randomly and independently varied. For example, respondents may be presented with the biography of a hypothetical political candidate where characteristics like the candidate’s age, gender, profession, political positions and party identification are randomly varied. The respondents would then be asked to evaluate several profiles or vignettes, and each time they would be presented with a different combination of attributes. This conjoint design makes it possible to then estimate the relative effect of each characteristic on the respondents’ answers.

Conjoint analysis offers several advantages.Footnote 80 First, it improves causal inference because it is possible to identify the effect of factors on individual preferences without making functional form assumptions. Secondly, conjoint analysis allows researchers to test many different hypotheses in a single research design. Thirdly, it enhances realism by asking respondents to evaluate choices with multiple pieces of information, unlike traditional designs, which attempt to isolate preferences along a single dimension. Fourthly, conjoint analysis asks respondents to register a single behavioral outcome – like supporting or opposing a given policy – which makes it possible to evaluate the relative explanatory power of multiple theories. Fifthly, conjoint designs give respondents multiple reasons to justify any policy decision. Sixthly, conjoint analysis is an excellent way to evaluate policy designs because it makes it possible to predict which components of various policies are likely to have the most support. Finally, recent research has suggested that the realistic properties of conjoint analysis result in high degrees of external validity.Footnote 81

Although conjoint analysis has been used to study a number of topics in IPE,Footnote 82 to our knowledge, our experiment is the first to use a conjoint design to study the flow of capital. In our conjoint experiment, respondents were asked to evaluate transactions in which a foreign firm is proposing to buy a domestic company.Footnote 83 We randomly varied features of each transaction related to the previously outlined hypotheses. More concretely, respondents in the United States were presented with the following vignette:

Company A is a company based in [Country Treatment] that is [Ownership Treatment]. Company A is currently attempting to acquire an American company in an industry that is considered to pose a [National Security Treatment] risk to national security. The American company is a [Firm Size Treatment]. The American company is in an industry that is experiencing [Economic Distress Treatment] than the American economy overall. The country that Company A is based in currently has [Reciprocity Treatment] in the same industry.

The text for the six bolded treatments was randomly and independently varied. The options for each of the six treatments are presented in Table 1. By randomly varying all of the options in Table 1, respondents in the United States were asked to evaluate a total of 576 different possible transactions.

Table 1 Treatment Options (as Presented to US Respondents)

* Indicates that this treatment was not presented to respondents in China.

After reading about the potential transaction, the respondents were asked whether their government should prevent the proposed acquisition. The respondents were only given two options to register their opinion: yes or no. By doing so, we used a ratings-based conjoint designFootnote 84 as opposed to a choice-based conjoint design.Footnote 85 The respondents were then asked to evaluate four more potential transactions, but each one presented the respondents with a different random set of treatments.Footnote 86

There are four features of the vignettes used in our conjoint experiment worth discussing. First, although some conjoint designs vary the order in which the treatments are presented, our design always presented the treatments in the same order. Using an invariant order has the advantage of allowing the vignette to take the form of a realistic paragraph and is consistent with several other recent articles that have used vignettes in conjunction with a conjoint design.Footnote 87 Presenting treatments in a fixed order does, however, introduce an additional assumption into our research design: that the order of the attributes does not affect the results. It is thus possible that the ordering of the treatments biases our results and limits our ability to comparatively evaluate the effects of treatments.

Secondly, the question we asked after the vignette was framed negatively (that is, should the government block the proposed transaction). We chose this formulation because it represents the policy choice that officials, at least in the United States, face. The US default is that foreign acquisitions of American companies are allowed,Footnote 88 but the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) process allows the government to block transactions that pose a national security risk.Footnote 89 The implication is that policy leaders are likely to be focused on when citizens want a transaction blocked, not when they want it approved. A concern with this decision is that the negative framing may prime respondents to be less supportive of transactions. That said, we do not believe this causes a substantial problem for our research for two reasons: we are interested in the relative effects of treatments (not absolute levels of support for foreign transactions) and we conducted two additional experiments that use a neutral framing.

Thirdly, although we varied six features of the transactions in the survey fielded in the United States, we were only able to vary four features in the survey fielded in China. We intentionally designed the surveys to be comparable, but shortly before our survey launched in China we were denied legal approval to ask Chinese respondents questions that highlighted rivalries with foreign countries or national security concerns. Given this constraint, Chinese respondents were given an amended version of the vignette that did not contain the Country Treatment or National Security Treatment.

Fourthly, there are several aspects of the wording of our vignette that may bias or limit the generalizability of our results. For example, our Country Treatment included types of countries – for example, a ‘democratic country’ – as well as three specific countries that have been the subject of specific hostility to foreign investments in the United States: China, Japan and Saudi Arabia. We did not, however, include specific countries from which respondents may respond favorably to foreign investment. Our results thus do not allow us to predict how respondents may have reacted to countries that may have been viewed more favorably. To put it another way, the ‘context’ of our vignette likely moderates the effect of reciprocity, and since we only asked about reciprocity in specific contexts and not the universe of possible cases, drawing broad generalizations from our findings may be inappropriate.

For our National Security Treatment, we varied whether the company is in an industry that ‘poses’ a high or low risk to national security. This was because specific industries are subject to greater scrutiny during the CFIUS review process based on their relevance to national security. A more natural way to word this treatment, however, may have been how ‘relevant’ the industry is to national security. Phrasing the treatment in terms of risk may have thus have created confusion that biased the results for this treatment.

Finally, our Firm Size Treatment varied whether the company was ‘a small company based in your area’ or a ‘national Fortune 500 company’. Although it reduced the total number of treatments to combine the geographic reach and size of the company, confounding these variables makes it impossible to disentangle their effects.

Results

Figure 1 presents the results for the respondents in the United States.Footnote 90 The dots are point estimates, and the lines are 95 per cent confidence intervals of the influence that each attribute has on the probability that respondents would support the government blocking a proposed foreign acquisition of an American company.Footnote 91 The options listed first for each treatment are baseline categories that serve as the benchmark for our estimates, and thus they do not have a point estimate or confidence interval. For example, the baseline for the Country Treatment is a ‘foreign country’. Figure 1 thus shows that when a firm is from ‘a country [that] is a security threat to the United States’, respondents are 11 percentage points more likely to support the government blocking the acquisition than when the firm is from a ‘foreign country’.

Fig. 1 Primary experiment results – US respondents Note: Figure 1 plots the average marginal component effect relative to baseline conditions for each treatment condition. Standard errors clustered at the individual level. Horizontal lines indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Figure 1 reveals that levels of reciprocal market access in a foreign firm’s home country have a substantial impact on support for blocking an acquisition. Compared to a baseline of no restrictions, opposition increases by 11 percentage points when the foreign firm’s home country has ‘a number of restrictions’ on American firms acquiring their companies and by 16 percentage points when the home country has ‘an absolute prohibition’ on American firms acquiring their companies. Interestingly, although market access restrictions substantially increased opposition, support only increased by 1 percentage point when the foreign firm’s home country had signed a treaty permitting American companies to acquire their companies.

Figure 1 also confirms prior research suggesting that the characteristics of the country of origin have a substantial effect on opposition to foreign investment.Footnote 92 Our results suggest that respondents are 11 percentage points more likely to oppose an acquisition by firms from countries described as security threats to the United States and 15 percentage points more likely to oppose an acquisition by a firm from a country that is both a security and economic threat. Interestingly, firms that are from countries that are just economic threats – and not security threats – only increased opposition over the baseline by 4 percentage points. Additionally, support increases by 8 percentage points when the foreign firm is from a democratic country and decreases by 4 percentage points when the foreign firm is from a non-democratic country.

In addition to testing types of countries, we also asked about three specific countries: China, Japan and Saudi Arabia. As previously noted, we selected these countries because proposed acquisitions of American companies by firms from these countries have generated controversy in the United States, and these three countries have all been the subject of previous survey research. Respondents in our sample were 6 percentage points more likely to oppose an acquisition by firms from China, 4 percentage points less likely to oppose an acquisition by firms from Japan, and 5 percentage points more likely to oppose an acquisition by firms from Saudi Arabia. Our results are consistent with previous research suggesting that Americans are more opposed to investments from China and Saudi Arabia than generic ‘foreign countries’, but more receptive to investments from Japan.Footnote 93

Figure 1 also suggests that the ownership of the foreign firm has minimal impact on support for blocking potential acquisitions. Opposition only increases by 1 percentage point when the foreign firm is government owned compared to privately owned firms. Unlike the ownership of the foreign firm, the national security risk of the industry being targeted had a large effect: opposition increased by 17 percentage points when the targeted companies are in industries with a high national security risk compared to industries where the national security risk was low.

In contrast to the large effect of the national security treatment, the two treatments that are proxies for the economic impact of the transaction had relatively small effects. Opposition only increased by 1 percentage point when the foreign firm targeted a company that is a national Fortune 500 company compared to small, local companies. Additionally, support increased by 2 percentage points when the foreign firm targeted companies in industries with unemployment rates above the national average compared to those in industries with unemployment rates below the national average.

Figure 2 presents the results from the respondents in China. For the reciprocity treatment, the Chinese respondents reacted comparably to American respondents. For the Chinese respondents, opposition increased by 8 percentage points when the foreign firm’s home country has ‘a number of restrictions’ on Chinese firms acquiring their companies and by 19 percentage points when the home country has ‘an absolute prohibition’ on Chinese firms acquiring their companies. As with the American respondents, opposition decreased by 5 percentage points when the foreign firm’s home country had signed a treaty providing Chinese companies the ability to acquire their companies. These results indicate that reciprocity is a major concern for both American and Chinese respondents.

Fig. 2 Primary experiment results – Chinese respondents Note: Figure 2 plots the average marginal component effect relative to baseline conditions for each treatment condition. Standard errors clustered at the individual level. Horizontal lines indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals.

The results for the Ownership treatment were also similar to the American sample: whether the foreign firm was privately or government owned had little impact on levels of support. In contrast, the size of the firm being targeted did impact the levels of opposition. Opposition increased by 11 percentage points when the foreign firm targeted a large national company compared to a small, local company. Finally, the Chinese respondents’ support increased by 7 percentage points when the foreign firm targeted a company in an industry with high rates of unemployment compared to companies in industries with low unemployment.

ADDITIONAL EXPERIMENTS

Secondary Experiment: Effect of Changes in Foreign Governments’ Policies

Our primary experiment revealed that reciprocity had a strong effect on public opposition to the acquisition of domestic firms. A complete lack of reciprocity increased opposition by 16 percentage points for American respondents and by 19 percentage points for Chinese respondents. However, the results also revealed that a positive reciprocal investment policy – signing a treaty to eliminate barriers – only increased support for acquisitions by 1 percentage point for American respondents and by 5 percentage points for Chinese respondents.

Because we were interested in the relationship between positive and negative reciprocity, our survey also included a secondary experiment focused solely on this relationship. We included this experiment because our conjoint analysis tested the effect of reciprocity on respondents’ support for blocking a specific transaction involving a single firm, but we also wanted to measure the effect of reciprocity on levels of support for broader restrictions on foreign acquisitions. We also wanted to frame government decisions in an active way; that is, saying that the foreign government had recently increased (or decreased) restrictions on investment.

In the secondary experiment, respondents were told that their country is considering changing its policies on the purchase of domestic companies by foreign firms.Footnote 94 The respondents were then told that a foreign country has recently made one of five changes in its policies towards acquisitions of their companies. Specifically, the respondents were randomly told that the foreign government had made it either: (1) ‘much harder’, (2) ‘somewhat harder’, (3) ‘no change in its process’, (4) ‘somewhat easer’ or (5) ‘much easier’ for US (Chinese) companies to buy companies in their country. The respondents were then asked whether the United States (China) should make it harder or easier for companies from that foreign country to acquire domestic companies.

The top panel of Figure 3 presents the results for American respondents and the bottom panel presents the results for Chinese respondents. Each horizontal line represents a different level of restriction that respondents were told the foreign country had recently implemented. The x-axis places responses on a scale from whether respondents thought it should be ‘much easier’ (set at 0) or ‘much harder’ (set at 1) for foreign companies to buy domestic companies. The dots represent the mean responses and the lines represent the 95 per cent confidence intervals for each treatment.

Fig. 3 Secondary experiment results – US and Chinese respondents Note: Figure 3 plots answers to the reciprocity follow up experiment for US and Chinese respondents. Subjects are told that a country has recently made some change to their policy (different horizontal lines) for how easy it is for a foreign firm to buy a domestic firm, ranging from (1) ‘much harder’ to (5) ‘much easier’. What should the response of their own country be? Horizontal lines indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Changes in reciprocal market access had a significant impact on how open American respondents thought the United States should be to foreign investment. When a foreign country has made it much harder for American companies to acquire their domestic firms, the mean response was 0.77. On the other end of the spectrum, even when the foreign country has made it ‘somewhat easier’ or ‘much easier’ for American firms to acquire their companies, American respondents were still more supportive of restricting access than increasing it. Specifically, both treatments had mean responses of 0.60. Further, the deviation from the baseline of no change (0.65) was smaller in the case of positive changes versus negative changes, but the difference does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (p=0.10).

Changes in reciprocal market access also had a significant impact on how open Chinese respondents thought China should be to foreign investment. The mean response was 0.69 when the foreign country made it ‘much harder’ and 0.48 when the foreign country made it ‘much easier’. The deviation from the baseline of no change (0.56) was smaller in the case of positive changes versus negative changes, but the difference does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (p=0.19).

There are two things worth noting about these results. First, these results provide some suggestive evidence that positive reciprocity may be weaker than negative reciprocity, but the results for both American and Chinese respondents failed to reach statistical significance at conventional levels. Secondly, for all five treatments, Chinese respondents were less supportive of increasing investment restrictions than the American respondents. This finding could be a result of differences in our samples, Chinese respondents being more open to foreign investment than Americans generally, or respondents’ views being influenced by the very different absolute levels of restrictions currently in place in the United States and China.

Follow-up Experiment: Positive and Negative Reciprocity

The secondary experiment only informed respondents about recent changes in another country’s level of openness to foreign investments; it did not tell them about the other country’s absolute level of openness to foreign investments. It is thus possible that the results are driven by beliefs about absolute levels of market access. For example, if American respondents believed that US investment policies were already dramatically more open than China’s, Americans may consequently not feel the need to make the United States more open to foreign investment in response to China opening its markets. In other words, beliefs about the absolute level of market access may influence willingness to punish negative policy changes or reward positive policy changes.

Given this concern, we conducted a follow-up experiment designed to manipulate changes in market access and absolute levels of market access. The experiment was fielded in June 2015 to 838 respondents in the United States recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (mTurk) service. We elected to field our experiment through mTurk because it offers the practical advantage of being dramatically cheaper than recruiting respondents through traditional firms, but research has suggested that mTurk still produces reliable results,Footnote 95 and mTurk has been widely used by political scientists to recruit respondents generally.Footnote 96 As in our case, it has also been used to recruit respondents for follow-up experiments conducted after using traditional firms for primary experiments.Footnote 97 The trade-off is that mTurk samples are less likely to be representative of the general population than those recruited by traditional firms, which potentially limits the generalizability of the results.Footnote 98

In our follow-up experiment, respondents were told that ‘[o]n a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is no restrictions and 10 is an absolute ban on foreign ownership, in the past, Country A has had a score of [Past Score Treatment] for the ability of US companies to buy companies in Country A. Today this country is now a [Present Score Treatment]’.Footnote 99 For both the Past Score Treatment and Present Score Treatment, respondents were randomly told that the levels were 0, 3 or 6. We thus had nine total treatment conditions. We then told the respondents that the United States is currently a 3 on this scale and asked the respondents whether the United States should make it easier or harder for companies from Country A to buy American companies.Footnote 100

Figure 4 presents the baseline results of this experiment. The horizontal axis runs from 0 (make much harder) to 1 (make much easier) and the vertical axis has each of the possible treatment conditions. Each condition first lists the Past Score and then the Present Score. For example, ‘3–6’ means the respondents were told that the country previously had a score of ‘3’ but now has a score of ‘6’ (in other words, the country had increased restrictions on foreign investments).

Fig. 4 Follow-up experiment results – baseline Note: Figure 4 plots the baseline results of the reciprocity follow-up experiment. Preferred US position (x-axis) versus other country past and present position (y-axis, 0 (no restrictions) to 10 (complete restrictions)). Horizontal lines indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals.

There are two findings worth noting in Figure 4. First, when the other country was at the same level as the United States in both the past and present (‘3–3’), the mean response was that the United States should not change its current policy. To be exact, the mean response for the ‘3–3’ treatment was 0.49. Secondly, respondents were most likely to favor making it much easier for foreign firms to buy US companies when the other country had the most open score (‘0’) in the present treatment. The respondents were most likely to favor making it much harder for foreign firms to buy US companies when the other country had the least open score (‘6’) in the present treatment.

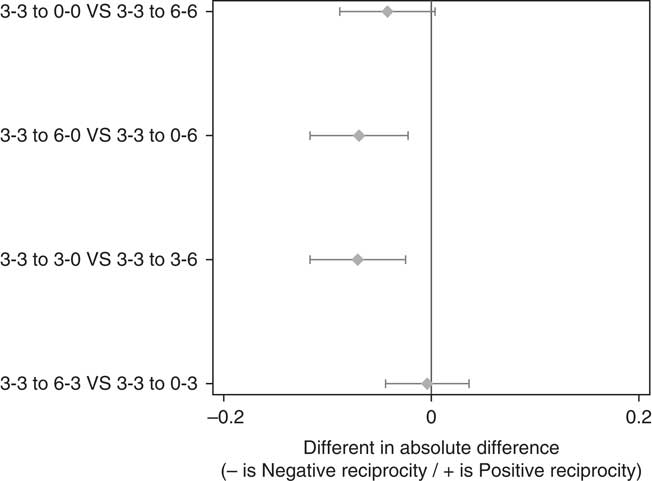

Although these results are informative, our goal with this experiment was to test the relationship between positive and negative reciprocity while simultaneously manipulating changes in market access and absolute levels of market access. Specifically, this experiment was designed to test the difference between positive and negative reciprocity by comparing responses for pairs of treatments that meet two criteria: (a) the size of movement between the past and present treatments is the same and (b) they are now equidistant from the US position of ‘3’. There are four pairs of treatments that meet these criteria: (1) ‘0–0’ & ‘6–6’; (2) ‘6–0’ & ‘0–6’; (3) ‘3–0’ & ‘3–6’; and (4) ‘6–3’ & ‘0–3’. For example, when we compare ‘6–0’ to ‘0–6’, both moved by ‘6’ and both countries now have policies that are equidistant from ‘3’. If negative and positive reciprocity were equally strong, then these two treatments would produce an average response that was the same distance from the baseline treatment of ‘3–3’. If negative reciprocity has a larger effect, however, then ‘0-6’ would have a treatment effect that is a greater distance from the baseline of ‘3–3’ than ‘6–0’.

To formally test this, we calculated a set of differences utilizing the ‘3–3’ treatment as a baseline. We estimated a regression model with all the treatment conditions as independent variables, clustered the standard errors by respondent, and then differenced the coefficients appropriately. This produces the ‘difference-in-absolute differences’ between the four matched pairs, whereby a negative value indicates that negative reciprocity had a larger treatment effect and a positive value indicates that positive reciprocity had a larger treatment effect.

Figure 5 presents these results. Each line represents one of the four matched pairs. To read Figure 5, take the matched pair of ‘0–0’ & ‘6–6’ that is presented in the first line. The baseline ‘3–3’ treatment had an average response of 0.49. The ‘0–0’ treatment – which asked respondents to consider a country that was more open to foreign investments than the United States – had an average response of 0.45. The absolute value of the distance between the ‘0–0’ treatment and the baseline ‘3–3’ treatment was thus 0.04.

Fig. 5 Follow-up experiment results – negative vs. positive reciprocity Note: difference in absolute deviations from baseline position of country at 3-3. Positive values indicate that the magnitude of change was greater in responding to positive changes by a country (positive reciprocity larger). Negative values indicate that the magnitude of change was greater in responding to negative changes by a country (negative reciprocity larger).

In contrast, the ‘6–6’ treatment – which asked respondents to consider a country that was less open to foreign investments than the United States – had an average response of 0.58. The absolute value of the distance between the ‘6–6’ treatment and the baseline ‘3–3’ treatment was 0.09. When this value (0.09) is subtracted from the value for its matched pair (0.04), the result is −0.05. This is the result reported in the first line of Figure 5. In other words, for this matched pair, there is a bigger effect for the negative reciprocity treatment than for the positive reciprocity treatment. This difference, however, falls just short of statistical significance at the 0.05 level.

Figure 5 shows that for all four matched pairs, the effect of the negative reciprocity treatment is larger than for the matched positive reciprocity treatment. The effect is statistically significant at the 0.05 level for two of the pairs and at the 0.1 level for three of the pairs. The effect is not statistically significant for the fourth pair (‘6–3’ to ‘0–3’). But it is worth noting that this is the only pair in which the foreign country ends with the same policy as the United States (‘3’), and perhaps unsurprisingly, the respondents simply answered that the United States should not change its policy. Taken together, these results provide evidence suggesting that many people more readily support punishing other countries for bad behavior than rewarding them for good behavior.

CONCLUSION

Our results suggest that reciprocity has an influence on opposition to foreign acquisitions of domestic companies. When a foreign firm’s home country restricts investments from the respondent’s country, the respondents are more likely to oppose potential transactions. This result is consistent with findings that fairness and reciprocity are important drivers of attitudes about foreign affairs generally,Footnote 101 and findings that reciprocity is an important driver of public opinion about specific areas of international relations.Footnote 102

We also found some suggestive evidence that the effect of positive reciprocity may be weaker than that of negative reciprocity. Simply put, the public may want their government to block investments from countries that restrict FDI flows, but may be less likely to support easing restrictions on firms from countries with few limitations on foreign investments. This finding, although inconclusive, is consistent with findings from experiments in psychology and economics about individual responses to negative and positive reciprocity.Footnote 103 It is also consistent with the fact that there have been calls in the United States to restrict investments from countries that do not provide access to American firms, but we are unaware of parallel proposals to provide additional market access to countries that have fewer market restrictions than the United States.Footnote 104

Before continuing, it is important to acknowledge that although our experiments suggest that reciprocity has an influence on public opinion on FDI, they do not demonstrate why reciprocity might affect opinion. It is possible that individuals care about reciprocity because they believe that it will induce co-operative behavior from other countries, or because believe fairness norms are important. Relatedly, it may simply be the case that FDI is a ‘hard’ issue for the public to process,Footnote 105 and reciprocity may thus be an appealing heuristic because it provides an intuitive answer to a hard question. Future research will be required to adjudicate between these possible explanations.

There are four main caveats to our results that should be noted. First, the effect of reciprocity on attitudes towards FDI may be particularly strong in the United States and China. Both countries are major sources of outward FDI as well as leading destinations for inward FDI. This may lead respondents in these countries to care more about reciprocal market access than respondents would in countries with less outward FDI. Secondly, we focused on M&As and not Greenfield investments, in part because we believed M&As would produce stronger public reactions, so reciprocal access for other forms of FDI may produce weaker responses. Thirdly, our survey experiments asked respondents for their opinions on individual transactions, and as a result they may not have fully captured the temporal aspects of reciprocity. Future research is needed to determine whether repeated FDI interactions attenuate the effect of reciprocity, or lead to patterns of escalation or de-escalation. Fourthly, although we found that reciprocity was an important determinant of public opposition to proposed foreign investments, this does not mean that these views would necessarily drive changes in actual policy. By showing that reciprocity can change public opinion, our results provide evidence for one step in a possible causal chain – they do not prove every link.Footnote 106

With those caveats in mind, we believe our results make an important contribution to our understanding of what influences public opinion on both foreign investment specifically and IPE more generally. Our results indicate that public attitudes change based on the policies that other countries adopt towards FDI. As previously noted, prior scholarship has focused on explaining attitudes towards IPE in economic and sociological terms, while largely ignoring public attitudes towards other countries’ behavior.Footnote 107 Our results suggest that there are limits to theories seeking to explain attitudes towards global economic integration exclusively in terms of domestic consequences or individual respondents’ characteristics. Our findings also highlight the need for further inquiry. How much weight do individuals evaluating foreign investments place on domestic consequences – like the effects on the economy or national security – compared to concerns like reciprocity? How does the preference for reciprocity translate into policy? Can policy instruments that try to ensure liberalization – like multilateral and bilateral treaties – help constrain countries? We leave all of these questions unanswered. But without answering them, it may be impossible to understand the wave of support for reversing economic integration that is sweeping the globe.