American public opinion is highly polarized on climate change. Surveys show that an overwhelming majority of Democrats believe climate change is happening, while fewer Republicans – especially those who are most conservative – share this belief (Tesler Reference Tesler2018). This polarization mirrors Democratic and Republican elites’ positions on the issue as well. Yet in 1997 the gap between strong partisans on climate change was only 5 percentage points: 73 per cent of Democrats and 68 per cent of Republicans reported that global warming was happening (Krosnick, Holbrook and Visser Reference Krosnick, Holbrook and Visser2000). Why do Republicans now largely reject the climate science consensus?

We argue that climate skepticism among Republicans may have been encouraged by polarizing party cues communicated through the news media, and specifically those from Democratic elites – the out-group party that has dominated climate change news coverage and has sent consistent signals to the mass public in support of the scientific consensus. This top-down model of attitude formation has a rich history in public opinion scholarship (see Berinsky Reference Berinsky2009; Lenz Reference Lenz2012; Zaller Reference Zaller1992), but research is comparably more limited on out-group cue taking and attitudinal backlash (but see Bischof and Wagner Reference Bischof and Wagner2019; Feddersen and Adams Reference Feddersen and Adams2018; Goren, Federico and Kittilson Reference Goren, Federico and Kittilson2009; Nicholson Reference Nicholson2012 for recent, important exceptions). Moreover, the role of party elites writ large has been underexplored in literature on climate change politics that is primarily focused on ideology-driven motivated cognition (Campbell and Kay Reference Campbell and Kay2014; Dixon, Hmielowski and Ma Reference Dixon, Hmielowski and Ma2017; Kahan, Jenkins-Smith and Braman Reference Kahan, Jenkins-Smith and Braman2011), organized climate skeptics and the journalistic practice of false balance (Boykoff and Boykoff Reference Boykoff and Boykoff2007; Dunlap and Jacques Reference Dunlap and Jacques2013; Dunlap and McCright Reference Dunlap, McCright, Dryzek, Norgaard and Schlosberg2011), and economic costs and related media framing (Nisbet Reference Nisbet2009; Scruggs and Benegal Reference Scruggs and Benegal2012). Some scholars have recently begun to explore the role of party elite cues in the context of climate change (Carmichael and Brulle Reference Carmichael and Brulle2017; Guber Reference Guber2013; Tesler Reference Tesler2018), but these works do not distinguish between in-group and out-group cueing and do not analyze the news media, which play a critical role in communicating elite cues to the mass public.

In this article, we build novel measures of aggregate climate change skepticism annually starting in 1986 and quarterly starting in 2001. We use a combination of dictionaries and supervised machine learning to identify news articles with party elite cues and common climate change news frames that are likely to be correlated with such signals. We find that Democratic elite cues lead, rather than follow, aggregate levels of climate skepticism and skepticism among Republican identifiers. We also demonstrate that these cues are correlated with our aggregate public opinion measures after controlling for confounders, such as the dynamics of cues from Republicans and common news media frames like the economic cost of climate change mitigation and scientific uncertainty. For stronger causal identification, we conduct a survey experiment on a sample of almost 3,000 American citizens and find that exposure to Democratic elite cues is associated with higher levels of self-reported climate skepticism among Republicans. The backlash effect found here is similar in size to providing Republicans in-group cues from Republican elites, but, importantly, its effect can be attenuated by a consensus cue in which Democratic and Republican elites signal agreement on climate science and mitigation.

In short, this article uniquely combines text analysis, time-series modelling and an experiment to illustrate the power of out-group cues in a real-world setting on an issue of high salience. The study provides a compelling explanation for the otherwise perplexing polarization of Americans on an important area of scientific consensus.

PARTY ELITES AND CLIMATE SKEPTICISM

Republican Party supporters are now much more skeptical of climate science than they were in the 1990s. Some scholars have highlighted ideology and values as the root causes of this phenomenon. These theories draw strongly from psychological research on motivated reasoning (Ditto and Lopez Reference Ditto and Lopez1992; Kunda Reference Kunda1990). Citizens may be motivated to resist messages from experts or seek out information from contrarian sources in support for their values and identities (Kahan, Jenkins-Smith and Braman Reference Kahan, Jenkins-Smith and Braman2011; Leiserowitz Reference Leiserowitz2006; Lewandowsky and Oberauer Reference Lewandowsky and Oberauer2016; Pasek Reference Pasek2017). And, in this case, the policy implications of climate change are not easily compatible with free market orthodoxy (Campbell and Kay Reference Campbell and Kay2014; Dixon, Hmielowski and Ma Reference Dixon, Hmielowski and Ma2017; Oreskes and Conway Reference Oreskes and Conway2010). According to this view, we are very unlikely to change people's minds unless we can reconcile climate action with these value predispositions.

However, there are important limitations to this approach. First, most Americans do not harbor consistent ideological predispositions (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2016; Kinder and Kalmoe Reference Kinder and Kalmoe2017). This fact becomes apparent in the climate change context, in which market-friendly ways to reduce carbon emissions, like carbon pricing, are much less popular among Republicans (Amdur, Rabe and Borick Reference Amdur, Rabe and Borick2014). Most people who label themselves as conservatives do not take consistent conservative positions on fiscal issues (Barber and Pope Reference Barber and Pope2019; Drutman Reference Drutman2017). More importantly for our purposes here, explanations rooted in motivated reasoning do not easily account for dynamics: conservatives and Republicans once had very similar views on climate change as liberals and Democrats (Krosnick, Holbrook and Visser Reference Krosnick, Holbrook and Visser2000). These are the dynamics we study here.

We believe considerable light is shed on this question by a long line of work in political science that has shown the importance of top-down persuasion by party elites in opinion formation. This occurs because many people use cues from parties as cognitive shortcuts to make decisions in a low-information context (Cohen Reference Cohen2003; Conover and Feldman Reference Conover and Feldman1989; Kam Reference Kam2005; Lenz Reference Lenz2012; Popkin Reference Popkin1991) or to form opinions in line with their strong affect-oriented attachments to parties (Lodge and Taber Reference Lodge and Taber2013). As a result, party elites can have considerable persuasive power (Cohen Reference Cohen2003; Kam Reference Kam2005).

Most research on party cues focuses on in-group cues, where partisans are responsive to signals from their own party's elites either because of the informative value of such cues or due to their own affective attachment to their party's leaders. However, partisans may also be responsive to out-group cues where they are repelled by signals from the opposing party's elites, rather than being persuaded. Again, the mechanism undergirding such responsiveness could be either a rational process of learning in a low-information context or a social–psychological response to negative affect associated with out-group elites. The latter has become more important over time as partisans have become affectively polarized (Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012).

Some empirical work has shown that out-group cues can cause ‘backlash’ in the United States. In an experimental setting, Nicholson (Reference Nicholson2012) manipulates the existence of cues from then-presidential candidates John McCain and Barack Obama, as well as President George W. Bush, on a pair of bills related to immigration and foreclosure. He finds that out-group cues repelled partisans more than in-group cues persuaded co-partisans. Goren, Federico and Kittilson (Reference Goren, Federico and Kittilson2009) likewise find that party elite cues can influence the degree to which partisans agree with value statements; out-group party cues are notably more powerful. Observationally, it is tricky to disentangle the effects of in-group and out-group cues since they typically rise and fall together with issue salience in the real world. Berinsky (Reference Berinsky2009), however, shows that Democratic identifiers turned against support for the Iraq War even when the signals sent by their own party's elites were mixed, suggesting the responsiveness of these partisans to unified Republican elite support.

There is also some evidence of out-group cueing in the comparative context. Bischof and Wagner (Reference Bischof and Wagner2019) find that the entry of ideologically extreme parties into the Dutch parliament had a polarizing effect on citizens. Specifically, the entry of far-right parties pushed left-wing partisans further to the left. Similarly, Feddersen and Adams (Reference Feddersen and Adams2018) show that Swiss voters were influenced by party positions on migration as signaled by press releases – including a notable backlash against out-group parties. There is a growing sense that out-group cues may be as important as in-group cues in opinion formation, and perhaps even more so.

There are grounds to expect that party cues may have played an important role in stimulating climate skepticism. Most Americans get their information on climate change primarily from the news media (Tesler Reference Tesler2018), which has increasingly carried party cues to the public as the issue has become more salient (Merkley and Stecula Reference Merkley and Stecula2018). Importantly, these elite cues signal the existence of a sharp political divide to the public, unlike in other countries (McCright and Dunlap Reference McCright and Dunlap2011). Party elite cues certainly had an opportunity to shape American attitudes on climate change, but that is far from evidence that they may have been responsible for over-time dynamics in climate skepticism.

Observational evidence has been consistent with the predictions of elite cueing theory in three ways. First, the sharpest divide on climate science exists among those who are highly educated, those who consume the most news and those who are most attentive to the issue (Guber Reference Guber2013; Tesler Reference Tesler2018), which is in line with Zaller (Reference Zaller1992). Importantly, elite cueing theory also passes a placebo test: this finding does not hold in countries where party elites are less divided on climate action (Tesler Reference Tesler2018). Secondly, prior studies have found that concern about climate change is correlated with legislative activity such as committee hearings (Carmichael and Brulle Reference Carmichael and Brulle2017). Finally, there is some experimental evidence that softening Republican elite positions on climate change alters Republican attitudes towards climate science (Tesler Reference Tesler2018).

However, these works have two notable limitations. First, they do not build the news media environment into their analysis even though it plays an important role in this process by communicating elite cues to the broader public (Althaus et al. Reference Althaus1996; Bennett Reference Bennett1990; Dalton, Beck and Huckfeldt Reference Dalton, Beck and Huckfeldt1998). Secondly, and more importantly for our purposes, these works cannot distinguish between out-group and in-group cueing effects. And there is reason to suspect out-group cues may have played a particularly important role in shaping Republican attitudes towards climate change. Democratic cues are much more pronounced in climate coverage, and Republican cues have been inconsistent in their direction – either in support of or in opposition to climate action – at least until 2009 (Merkley and Stecula Reference Merkley and Stecula2018). It is a case that, in some respects, resembles elite debate surrounding the Iraq War, where in-group party cues from Democratic elites were muddled and not particularly informative compared to out-group party cues from Republicans for Democratic partisans (Berinsky Reference Berinsky2009).

The clear observable implication is that there should be some association between the prevalence of cues from Democratic elites in the news media – where most Americans learn about climate change – and climate skepticism. However, one complication associated with interpreting over-time correlations on this question is the threat of reverse causality. A sizable literature in opinion formation tells us that elites often have an important influence on public attitudes (Lenz Reference Lenz2012; Zaller Reference Zaller1992), but policy makers are often responsive to public opinion for the purposes of securing re-election (Erikson, Mackuen and Stimson Reference Erikson, Mackuen and Stimson2002). As a result, we expect to see that Democratic elite cues lead, rather than follow, aggregate levels of climate skepticism.

Hypothesis 1: The prevalence of Democratic Party elite cues in the news lead aggregate levels of skepticism about climate science.

We test this hypothesis with vector autoregression (VAR), which is described in more detail below. One limitation of this approach is that it does not speak to contemporaneous relationships between variables. For more evidence of a causal process, we want to also show that there is a positive, contemporaneous association between these variables, holding constant other factors we might think are important.

Other dynamics in political discourse may act as sources of confounding. The most obvious candidate are cues from Republican elites. Journalists often cite ‘both sides’ in a story to preserve balance (Boykoff and Boykoff Reference Boykoff and Boykoff2007). As a result, Republicans are likely to be cited alongside Democrats in periods when climate change and related policy are salient. Republican supporters are also likely to take cues from their in-group party on climate change, so we need to control for them.

Additionally, we want to account for frames in discourse that might influence climate skepticism, while also being correlated with the prevalence of party elite cues. This is because party elites use such frames when justifying their positions in news coverage of climate change. Frames that emphasize the economic costs of climate mitigation or scientific uncertainty might be of particular importance in explaining climate skepticism. We know that poor economic conditions (Brulle, Carmichael and Jenkins Reference Brulle, Carmichael and Jenkins2012; Carmichael and Brulle Reference Carmichael and Brulle2017; Elliott, Seldon and Regens Reference Elliott, Seldon and Regens1997; Scruggs and Benegal Reference Scruggs and Benegal2012), energy prices (Scruggs and Benegal Reference Scruggs and Benegal2012) and the cost of reforms reduce support for policy action (Ansolabehere and Konisky Reference Ansolabehere and Konisky2014; Bechtel and Scheve Reference Bechtel and Scheve2013). Thus opponents of climate change action use frames related to economic cost, which is carried to the mass public by the media (Nisbet Reference Nisbet2009). Over the course of a policy debate on the costs and benefits of certain policies, these frames appear with some regularity (Stecula and Merkley Reference Stecula and Merkley2019), and experimental evidence has shown that these frames can influence public opinion (Davis Reference Davis1995; Vries, Terwel and Ellemers Reference Vries, Terwel and Ellemers2016).

Other analysts have highlighted a campaign orchestrated by industry and conservative groups to highlight supposed uncertainties in the fundamental tenets of the consensus of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – that climate change is happening, man-made and a serious threat (Dunlap and Jacques Reference Dunlap and Jacques2013; Farrell Reference Farrell2016a; Farrell Reference Farrell2016b; Jacques, Dunlap and Freeman Reference Jacques, Dunlap and Freeman2008). They engaged in this framing in order to reify the status quo (Feygina, Jost and Goldsmith Reference Feygina, Jost and Goldsmith2010). Journalists, for their part, unwittingly elevated these arguments to provide balanced coverage (Boykoff and Boykoff Reference Boykoff and Boykoff2007; Dunlap and McCright Reference Dunlap, McCright, Dryzek, Norgaard and Schlosberg2011). Content analyses have shown that uncertainty framing has been prevalent in the past (Boykoff and Boykoff Reference Boykoff and Boykoff2007; Painter Reference Painter2013; Painter and Ashe Reference Painter and Ashe2012), and some experimental studies have found that citing contrarian experts indeed confuses the public about the existence of expert consensus (Corbett and Durfee Reference Corbett and Durfee2004; Friedman et al. Reference Friedman, Dunwoody and Rogers1999; Koehler Reference Koehler2016).

These frames may influence public attitudes about climate change; Republican elites are likely to use them in the course of a political debate. To the extent that dynamics in these frames are correlated with party elite cues, they may serve as confounds, which leads to our second hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2: There is a positive, contemporaneous correlation between the prevalence of Democratic Party elite cues and climate skepticism, holding other factors constant.

Evidence of a correlation between Democratic elite cues and aggregate climate skepticism, in which the former has temporal precedence and where the relationship is robust to controls, would provide some evidence of out-group cueing effects on climate skepticism, but ultimately such a design is not causal. A large experimental literature has shown that party cues can influence attitudes on a number of questions related to public policy, but most of this work has focused on in-group cues and almost none has used climate change as a test case. Experimental evidence in support of an out-group cueing effect on attitudes towards climate science would help shore up our causal claim:

Hypothesis 3: Skepticism of climate science will be higher among Republicans when respondents are exposed to a cue signaling Democratic Party support for climate science and mitigation.

AGGREGATE TIME-SERIES DATA AND METHODS

We begin by outlining the method and results of our aggregate time-series analyses before describing the design and results of our experiment. We follow the lead of Stimson (Reference Stimson1999) in measuring aggregate levels of climate change skepticism. We combine 172 different poll questions since the late 1980s from the Roper Center archive at Cornell University, which is a repository of a wide selection of polls addressing climate change attitudes.

The questions we use for our measure include those that asked respondents whether or not climate change is happening, whether or not climate change is a serious problem, whether or not they are worried about global warming, and whether or not climate change is caused by humans.Footnote 1 After ensuring all of the questions were coded in the same direction, we used them to extract a latent measure of public skepticism of climate change. We are able to construct an annual measure beginning in 1986 and a quarterly measure starting in 2001 with available polling data. Our aggregate climate skepticism measures are presented in the left and center panels of Figure 1.

Figure 1. Climate change skepticism

Note: (A) Annual, 1986–2014, (B) Quarterly, 2001–2014, (C) Republicans, Quarterly, 2001–2014. All series displayed without WCalc smoothing.

The aggregate measures of climate skepticism used here, however, do not tell us what is happening among Republican identifiers specifically. Carmichael and Brulle (Reference Carmichael and Brulle2017) constructed a quarterly measure for Republicans starting in 2001 using the same method. Their Partisan Climate Change Threat Index (PCCTI) uses a slightly different subset of climate change polling questions – focused exclusively on perceptions of the seriousness of the threat posed by climate change. The series for Republican identifiers is presented in Panel C of Figure 1; it is reverse coded so that higher values indicate more skepticism of climate change. Our quarterly variant of aggregate climate skepticism is highly correlated with the reverse-coded Republican PCCTI (0.48). We standardize our public opinion measures for ease of interpretability.

The dynamics of aggregate opinion on climate science are likely explained in part by changes in the news media information environment. As a result, our primary variables of interest are constructed from a media content analysis. We downloaded climate change coverage by the New York Times and the Washington Post from LexisNexis. We chose these sources for two main reasons. First, newspapers play a more important role in informing the electorate than television (Druckman Reference Druckman2005), and these are two of the highest-circulation newspapers in the United States that are traditionally seen as agenda-setting outlets throughout our period of study (Golan Reference Golan2006; McCombs Reference McCombs2005).Footnote 2 As a result, numerous studies in the field of political communication use these sources as proxies for the news media (see, for example, Eyck and Williment Reference Eyck and Williment2003; Farnsworth and Lichter Reference Farnsworth and Lichter2005; Soroka, Stecula and Wlezien Reference Soroka, Stecula and Wlezien2015). Secondly, we needed sources that were continuously available since the beginning of the time period of our study in 1986, which ruled out sources like the USA Today or the Wall Street Journal. Articles and transcripts were selected if they mentioned climate change or global warming in the body of the text or the subject tag. We then ensured the articles were relevant and primarily focused on climate change.Footnote 3

We define a party cue in this context as an explicit or implicit stance on climate change science or related policy attributed to elites of either the Democratic or Republican Party. We measure these cues using the automated content analysis software Lexicoder in conjunction with a dictionary of key terms, such as party names, office titles and party leaders. These leadership positions include presidents, presidential nominees, vice presidents, speakers of the House, and Senate and House majority and minority leaders. Our dictionaries can be found in Appendix Section B. We classify articles according to whether or not they reference the Democratic or Republican Party and their respective elites. Of course, not all articles with party references contain cues signaling elite positions on climate change, but the overwhelming majority do. We manually coded a random sample of 700 articles that referred to either party in the text to validate our automated measure. Approximately 80 per cent of these articles contained a cue on climate change according to our definition.

We constructed a time-series measure of the share of articles in a given period that contain cues from Democratic and Republican elites, respectively. We use shares because volume measures are more likely to be correlated with other factors that are also associated with the overall salience of climate change. However, our results are robust to using volume measures as shown in Appendix Table D1.

One limitation of using these measures is that they do not account for the message being conveyed by party elites. We manually coded a random sample of 3,000 news articles and transcripts on climate change that an identical automated analysis indicated featured either Democratic and Republican cues for a related project. We scored articles according to whether they contained a consistent message from a party either in favor of or opposed to the climate consensus, or if the messages in the article were mixed in their orientation.Footnote 4 The overwhelming majority (97 per cent) of articles featuring messages from Democratic elites contained messages that were entirely supportive of the climate consensus, even as far back as the 1980s. By contrast, Republican elites oscillated between periods of strident opposition to the climate consensus, such as during the Kyoto debate, and conciliatory messages during the later stages of the Bush administration. Notably, our coding of the share of Republican messages hostile to climate science and mitigation is highly correlated with the League of Conservation Voters’ congressional roll-call score on the environment for Republicans in the House and Senate (0.72), suggesting it is a valid indicator of the stance taken by Republican elites on climate change.

Consequently, we multiply the proportion of climate news stories with Republican cues by the proportion of Republican messages uniformly hostile to climate science or mitigation. This gives us an estimate of the share of climate news stories with Republican cues with this specific message. Appendix Figure C1 compares the share of news stories with Republican cues, the share of news stories our hand coding determines have Republican cues hostile to the climate change consensus, and our composite measure of the two. We use this composite measure in the analyses that follow.

Our quarterly measures for Democratic and Republican cues are displayed in Panel A of Figure 2. The panel shows that Democratic cues have experienced a sustained increase since 2008, while Republican cues with messages hostile to climate science and mitigation have been on the decline since 2001. An annual version of this graph starting in 1986 can be found in Panel A of Appendix Figure C2.

Figure 2. Potential polarizers in the news, quarterly data 2001–2014

Note: (A) Democratic, and Republican cues in news coverage; (B) Uncertainty framing; (C) Economic cost framing; (D) Salience of coverage.

MODELS

The first set of hypotheses address the direction of the association between party cues and aggregate climate skepticism. We can shed some light on this by estimating a reduced-form VAR where our endogenous variables are regressed on their past values and the past values of the other endogenous variables in our system. The downside of this approach is that it does not tell us anything about the contemporaneous relationships between the variables. We cannot use the results to infer causality. We can, however, learn whether one variable ‘granger causes’ another – that is, whether past values of a variable facilitate the prediction of current values of another variable above and beyond the previous values of other variables in the system.

We estimate a series of VAR equations to disentangle the relationship between aggregate climate skepticism and party elite cues.Footnote 5 We control for exogenous changes in the climate, comprised of a standardized National Oceanic and Atmosphere Administration index of the share of days below the average temperature or in drought conditions. We also hold constant exogenous dynamics in economic conditions, proxied with unemployment rates and crude oil prices taken from the Federal Reserve Economic Data database. Finally, we control for seasonality with dummies representing the quarter of the year. We do not control for a linear trend because we do not think it is theoretically defensible. Ultimately, we are interested in accounting for any trends in public attitudes towards climate change. Here we display the results of granger causality tests. We expect Democratic elite cues to granger cause aggregate climate skepticism, but not the reverse (Hypothesis 1). Republican cues are also likely to lead aggregate climate skepticism, though this is less central for our purposes here.

To test our second hypothesis, we estimate lagged dependent variable models quarterly from 2001 to 2014 and annually from 1986 to 2014 that regress aggregate climate skepticism on its lag, Democratic elite cues and a set of controls. We have theoretical reason to expect memory in our dependent variable – climate skepticism at t − 1 is likely to partially cause its value at t because there tends to be stickiness in public opinion – so omitting the lag could lead to biased estimates. More formally, the model is represented in Equation 1. β 1 should be positive and significant to provide support for Hypothesis 2.

$$\eqalign{ {\rm climate}\,{\rm skepticis}{\rm m}_t & = \alpha + \delta \,{\rm climate}\,{\rm skepticis}{\rm m}_{t-1} \cr & \quad + \beta _1\,{\rm democratic}\,{\rm cue}{\rm s}_t + \beta _{2-11}X + \varepsilon } $$

$$\eqalign{ {\rm climate}\,{\rm skepticis}{\rm m}_t & = \alpha + \delta \,{\rm climate}\,{\rm skepticis}{\rm m}_{t-1} \cr & \quad + \beta _1\,{\rm democratic}\,{\rm cue}{\rm s}_t + \beta _{2-11}X + \varepsilon } $$X in the above equation represents a series of media and non-media controls. First, we expect there so be some correlation between Republican and Democratic elite cues, and the former may also be correlated with aggregate climate skepticism because of an in-group cueing process. Secondly, we have some expectation that frames related to uncertainty and economic cost may be both associated with the prevalence of party elite cues and climate attitudes. Emphasis frames can be less adequately captured with simple dictionaries. As a result, we identified stories with economic cost and uncertainty frames by using supervised machine learning, which is increasingly used to study news content and political discourse more broadly (Grimmer and Stewart Reference Grimmer and Stewart2013; Lacy et al. Reference Lacy2015).

We manually coded a random sample of 2,179 newspaper articles stratified across three periods (1980–1996, 1997–2005 and 2006–2014) to minimize any fluctuation in the performance of the algorithm as climate change rose in salience. Articles and transcripts were coded 1 if they discuss the perceived costs of climate change mitigation, such as higher energy prices, a weaker economy, fewer jobs, declining competitiveness against developing countries or the costs of regulatory compliance. These articles contained economic cost frames. On a separate dimension they were coded 1 if they questioned the major elements of the IPCC consensus – that climate change is happening, predominantly man-made and a serious threat.Footnote 6 These articles contained uncertainty frames.

We trained a pair of support vector machine (SVM) algorithms on our manually coded articles.Footnote 7 SVM is a supervised machine-learning technique that plots data points on an n-dimensional space to find a hyperplane that best differentiates between different classes of objects. We randomly divided our manually coded set into a training (80 per cent) and testing set (20 per cent) for each coding task to validate our automated classification. We found reasonably close agreement between our classifier and our manual coding. Importantly, the prevalence of false positives and false negatives is similar, meaning our estimates of the prevalence of these frames are likely unbiased over a large number of observations in each period.Footnote 8

Panel B of Figure 1 displays the prevalence of uncertainty frames at the quarterly level since 2001. They have declined from around 20 to 25 per cent before 2007 to 15 per cent afterward. The annual variant of this graph in Panel B of Figure C2 shows more clearly that uncertainty frames have been on the decline since a peak of around 45 per cent in 1997. Panel C illustrates the dynamics of economic cost frames. They too have been on the decline since 2001. The annual variant in Panel C of Figure C2 shows that they tend to increase in times of policy debate, like in 1992, 1997 and 2001.

As expected, the prevalence of Republican cues is correlated with economic cost frames quarterly (0.64) and annually (0.55), but not as strongly with the prevalence of uncertainty frames (0.34 and −0.07). Nevertheless, controlling for the dynamics in these frames will give us more confidence that we are seeing evidence of a causal association between party elite cues and climate skepticism. Secondly, we control for salience with the combined number of stories in the New York Times and the Washington Post on climate change. Panel D of Figure 2 plots the volume of articles. Salience steadily increased going into 2007, and spiked again in 2009 and 2010. There appears to have been a sustained increase in the equilibrium level of climate change salience. The annual variant of this plot can be found in Panel D of Appendix Figure C2. The prevalence of Democratic cues is highly correlated with climate change salience quarterly (0.57) and annually (0.57), however, this is not true for Republican cues (−0.45 and 0.11). Finally, we preserve our controls from the VAR models for climate and economic conditions as well as seasonality.

AGGREGATE TIME-SERIES RESULTS

Table 1 reports the results of the granger causality tests. The top panel shows our tests using quarterly aggregate climate skepticism, while the bottom panel uses our measure of climate skepticism for Republican identifiers. There is strong evidence that Democratic cues lead climate skepticism (Hypothesis 1). These signals in the news media granger cause aggregate climate skepticism (p ~ 0.01) and climate skepticism specifically among Republican identifiers (p ~ 0.03), while climate skepticism does not granger cause these cues (p ~ 0.32 and p ~ 0.86). By contrast, there is only weak and inconsistent evidence of an in-group cue-taking process. Republican cues do not granger cause overall aggregate levels of climate skepticism (p ~ 0.94), but they do weakly granger cause skepticism for Republicans specifically (p ~ 0.09). Climate skepticism does not granger cause Republican cues in either case (p ~ 0.82 and p ~ 0.99).

Table 1. Granger causality tests

The VAR analyses provide some evidence of cue taking on climate change, with a comparatively stronger sign of out-group cue taking among Republicans. Democratic elite cues appear to lead Republican climate skepticism, signaling that these citizens have been repelled by Democratic messages on climate change (Hypothesis 1).

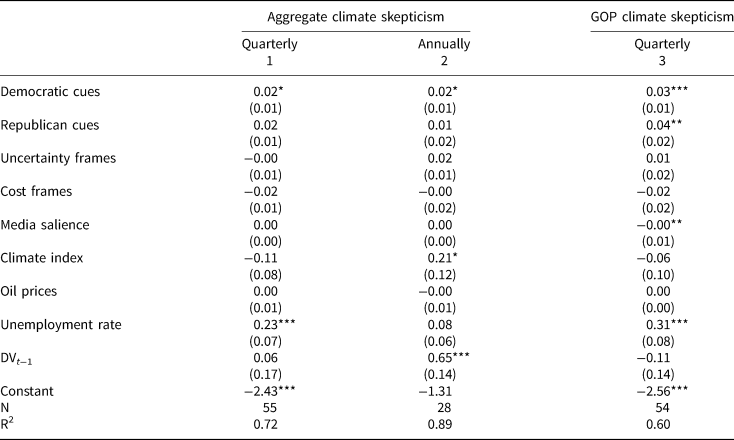

One limitation of the previous analyses is that they do not provide evidence of contemporaneous relationships. We might also want to tease out whether it is the dynamics in Democratic elite cues that are affecting opinion, or whether other elements of media discourse are doing the work while being correlated with these cues. Table 2 provides the results of our contemporaneous models. Again, there is stronger evidence of out-group, rather than in-group, cue taking (Hypothesis 2). Model 1 shows that A 10-percentage-point increase in the share of Democratic cues in climate coverage is associated with a 0.2-standard-deviation increase in climate skepticism (p ~ 0.07). Republican cues are non-significant. Aside from Democratic cues, unemployment also appears to be strongly correlated with aggregate climate skepticism (p < 0.01).

Table 2. Predictors of aggregate climate change skepticism

Note: robust standard errors in parentheses, *p < 0.1 **p < 0.05 ***p < 0.01

Our quarterly model of aggregate climate skepticism is restricted to the period of 2001–2014 because of polling data availability. The same result holds for our annual version of the series starting in 1986 (Model 2). A 10-percentage-point increase in the prevalence of Democratic cues is associated with a 0.2-standard-deviation increase in aggregate climate skepticism (p ~ 0.09). Republican cues are not significantly related to aggregate climate skepticism (p ~ 0.60).

Model 3 provides some evidence of both in-group and out-group cue taking (Hypothesis 2) using our measure of Republican skepticism towards climate change provided by the PCCTI. A 10-percentage-point increase in Democratic cues is associated with a 0.3-standard-deviation increase in Republican climate skepticism (p < 0.01), while a 10-percentage-point increase in Republican cues opposed to the climate change science or mitigation is associated with a 0.4-standard-deviation increase in Republican climate skepticism (p ~ 0.02). After controlling for party cue prevalence, uncertainty and economic cost framing are not associated with Republican climate skepticism. Republicans also appear responsive to the unemployment rate. A one-point increase in the unemployment rate is associated with a 0.3-standard-deviation increase in climate skepticism (p < 0.001). Interestingly, Republicans become less skeptical of climate change when salience increases after controlling for the prevalence of party cues. An increase in 100 news articles per quarter about climate change is associated with a decrease of 0.4 standard deviations in Republican climate skepticism (p ~ 0.03).

The previous results provide consistent support for an out-group cue-taking effect in climate change attitudes (Hypothesis 2). Democratic cues appear to be a key predictor of aggregate levels of climate change skepticism, as well as skepticism among Republicans specifically. Importantly, these cues lead, rather than follow, opinion (Hypothesis 1). Together these results suggest that Republicans are repelled, rather than persuaded, by Democratic elite cues in climate change coverage. There is comparatively mixed evidence for in-group cue taking.

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

The previous section provides some observational evidence that Democratic elite cues shape aggregate levels of climate skepticism and are strongly associated with skepticism even after controlling for other elements of political discourse that might influence these dynamics. However, aggregate time-series analyses only provide suggestive evidence of causality. Other factors that we have not measured may act as confounders over time.

For stronger evidence of a causal link between Democratic elite cues and climate skepticism, we conducted a survey experiment on a sample of almost 3,000 American respondents from Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) in 2019. This sample is comparable to the American public in gender, race, partisanship and ideology. However, it skews younger, wealthier and more educated. A comparison between our MTurk sample and the 2016 General Social Survey is shown in Appendix Table E1. This sample is comprised of people who are more likely to pay attention to climate change and to have well-formed opinions on the issue. Any treatment effects found in this sample are likely to be, if anything, a conservative estimate of the effect of elite cues on the American public.

All respondents received a short statement outlining the scientific consensus on climate change. We randomly assigned respondents into one of two conditions to receive a cue about climate science and mitigation policy from Democratic elites. Respondents received no such cue in the control condition. We also want to compare the effects of receiving Democratic elite cues to receiving cues from Republican elites or from both, so we also randomly assigned respondents into three conditions to receive cues from Republican elites. One treatment condition signaled Republican opposition to climate science and mitigation policy, while another condition provided information that Republican elites were increasingly likely to support the scientific consensus and climate mitigation policy. Respondents in the control condition received no cue from Republican elites.

The experimental conditions are displayed in Table 3 and the text of the treatments can be found in the Appendix. From these randomizations we can extract six distinct experimental conditions. The control condition does not contain a party cue of any sort. The Democratic cue condition contains only a cue from Democratic elites. The opposing Republican cue condition contains only a cue from Republican elites expressing skepticism about climate science and opposition to climate mitigation, while the polarized cues condition contains both this cue and the one from Democratic elites. The supporting Republican cue condition only contains a cue signaling increasing Republican acceptance of climate science and mitigation policy, while the consensus cues condition contains both this cue and a cue from Democratic elites.

Table 3. Party cue experimental conditions

The experimental protocol was as follows. Respondents first completed a short pre-treatment survey featuring questions related to their demographics and socio-economic status. They also indicated their partisanship and were given a pair of screener questions.Footnote 9 Respondents were then exposed to the party cue corresponding to their treatment condition. They finally answered a question related to our dependent variable of interest – climate skepticism – by indicating their level of agreement with the following statement (strongly agree to strongly disagree, 7-point): ‘The Earth is getting warmer mostly because of human activity, such as burning fossil fuels’. A total of 80 per cent of respondents agreed with the scientific consensus at some level, while only 13 per cent disagreed to some degree. We re-scale this variable from 0 to 1 for the following analysis, where 1 indicates respondents who are the most skeptical of climate science. All variables are described in Appendix Table E2.

MODEL

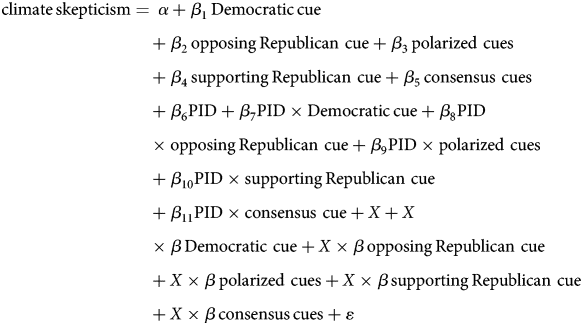

We estimate a simple OLS regression model in which we interact each of our treatment conditions with a measure of respondent partisanship on a 7-point scale ranging from strongly Democratic to strongly Republican. Partisanship, however, cannot be randomly assigned. Our treatment may have heterogeneous effects across other variables that are correlated with partisanship. One likely possibility is that the effect of our cue treatment may be moderated by the trust people have towards scientists – independent of partisan considerations – because each of our treatments involves parties either supporting or rejecting the scientific consensus illustrated in the control condition. The effectiveness of our treatment also likely varies across levels of political interest. We control for each of these variables and their interactions with our treatment conditions in our model; X represents our controls shown below in Equation 2:

$$\eqalign{{\rm climate}\,{\rm skepticism} &= \, \alpha {\rm} + \beta _ 1\,{\rm Democratic}\,{\rm cue} \cr & \quad {\rm} + \beta _ 2\,{\rm opposing}\,{\rm Republican\ cue} + \beta _ 3\,{\rm polarized\ cues} \cr & \quad{\rm} + \beta _ 4\,{\rm supporting}\,{\rm Republican\ cue} + \beta _ 5\,{\rm consensus\ cues} \cr & \quad + \beta _ 6{\rm PID} + \beta _ 7{\rm PID} \times {\rm Democratic}\,{\rm cue} + \beta _ 8{\rm PID} \cr & \quad \times {\rm opposing}\,{\rm Republican\ cue} + \beta _ 9{\rm PID} \times {\rm polarized\ cues} \cr &\quad {\rm} + \beta _{ 10}{\rm PID} \times {\rm supporting}\,{\rm Republican\ cue} \cr & \quad + \beta _{ 11}{\rm PID} \times {\rm consensus\ cue} + X + X \cr & \quad \times \beta \,{\rm Democratic\ cue} + X \times \beta \,{\rm opposing}\,{\rm Republican\ cue} \cr &\quad {\rm} + X \times \beta _{}\,{\rm polarized\ cues} + X \times \beta \,{\rm supporting}\,{\rm Republican\ cue} \cr & \quad{\rm} + X \times \beta \,{\rm consensus}\,{\rm cues} + \varepsilon } $$

$$\eqalign{{\rm climate}\,{\rm skepticism} &= \, \alpha {\rm} + \beta _ 1\,{\rm Democratic}\,{\rm cue} \cr & \quad {\rm} + \beta _ 2\,{\rm opposing}\,{\rm Republican\ cue} + \beta _ 3\,{\rm polarized\ cues} \cr & \quad{\rm} + \beta _ 4\,{\rm supporting}\,{\rm Republican\ cue} + \beta _ 5\,{\rm consensus\ cues} \cr & \quad + \beta _ 6{\rm PID} + \beta _ 7{\rm PID} \times {\rm Democratic}\,{\rm cue} + \beta _ 8{\rm PID} \cr & \quad \times {\rm opposing}\,{\rm Republican\ cue} + \beta _ 9{\rm PID} \times {\rm polarized\ cues} \cr &\quad {\rm} + \beta _{ 10}{\rm PID} \times {\rm supporting}\,{\rm Republican\ cue} \cr & \quad + \beta _{ 11}{\rm PID} \times {\rm consensus\ cue} + X + X \cr & \quad \times \beta \,{\rm Democratic\ cue} + X \times \beta \,{\rm opposing}\,{\rm Republican\ cue} \cr &\quad {\rm} + X \times \beta _{}\,{\rm polarized\ cues} + X \times \beta \,{\rm supporting}\,{\rm Republican\ cue} \cr & \quad{\rm} + X \times \beta \,{\rm consensus}\,{\rm cues} + \varepsilon } $$We expect positive, significant coefficients on β 7 and β 9 in support for Hypothesis 3, and we also expect a positive, significant coefficient on β 8 in line with in-group cue taking.

EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

Figure 3 displays the estimated marginal effects from the model based on Equation 2. Appendix Table E3 reports the full estimation results.Footnote 10 The results strongly support the findings of the aggregate time-series analyses. Panel A shows the estimated effect of a Democratic Party cue on climate skepticism. The interaction term is positive and significant (p ~ 0.05). There is no significant effect on climate skepticism for those who are strongly Democratic, but among strong Republicans there is estimated to be an increase in climate skepticism of 0.06 points on the 0 to 1 climate skepticism scale – or about 0.2 standard deviations on that measure (p ~ 0.03). These results provide strong support for Hypothesis 3. The interaction for the opposing Republican cue treatment is also significant (Panel B; p ~ 0.02). Again, there is no estimated effect of this treatment on strong Democrats, but among strong Republicans there is expected to be a similar 0.06-point increase on the climate skepticism index in response to the cue (p ~ 0.02). There is evidence here of both in-group and out-group cue taking, primarily for Republican supporters.

Figure 3. Estimated effect of party cue treatments on climate change skepticism

Note: (A) Democratic cue treatment; (B) Opposition Republican cue treatment; (C) Supportive Republican cue treatment; (D) Consensus cue treatments; (E) Polarized cue treatment. The figure displays 90 per cent confidence intervals.

Unsurprisingly, the treatment condition that contained both Democratic and opposing Republican cues also has a significant interaction (Panel C; p ~ 0.003). There is expected to be a modest treatment effect among strong Democrats in the expected direction of 0.04 points, but it is only marginally significant (p ~ 0.09). Strong Republicans, however, are expected to increase their skepticism of climate change by 0.09 points or 0.3 standard deviations on this measure (p ~ 0.002). These effects are stronger than those of the Democratic cue and opposing Republican cue conditions, but the interaction term is not significantly different from either. By contrast, neither the supporting Republican cue nor the consensus cue treatment conditions exerted a polarizing effect on respondents. The effect of Democratic cues on Republican climate skepticism appears to have been attenuated by the Republican elite cue supportive of the climate change consensus.

In short, the experimental results presented here support the main findings from the aggregate time-series analyses presented in the previous section. Republican respondents were responsive to out-group party cues from Democratic elites in their reported attitudes towards climate science. These effects are modest, but they are still remarkable given the decades of partisan polarization that have already occurred on this question and the relatively thin nature of the treatments used here.

DISCUSSION

Climate scientists, politicians and political scientists alike have been perplexed that a sizable portion of the American public rejects climate science, particularly among Republican Party supporters. Some have pointed to the role of organized climate denialists and the prevalence of ‘false balance’ in news coverage; others have highlighted the importance of ideology and media framing. Until recently, the role of party elites has taken a back seat. All of these factors could very well influence climate attitudes in the isolation of a survey experiment, but this does not mean they are meaningful drivers of the dynamics of American climate skepticism. We believe scholars also need to investigate over-time dynamics in the news media environment in order to examine this question, which has thus far been neglected in research.

This article situates climate change polarization within the larger literature on citizen cue taking, opinion formation and persuasion. We argue that out-group cues from Democratic elites caused attitudinal backlash among Republican voters, reflected in their growing embrace of climate skepticism. The role of out-group cues in repelling partisan citizens has been less prominent in the literature, which has largely focused on persuasion by in-group elites (Cohen Reference Cohen2003; Kam Reference Kam2005; Mondak Reference Mondak1993), though the importance of out-group elites has recently come to scholarly attention in the United States (Goren, Federico and Kittilson Reference Goren, Federico and Kittilson2009; Nicholson Reference Nicholson2012). Our study provides more evidence of the central importance of out-group cues on a pressing and important national issue by marshalling a unique combination of text analysis, time-series modelling and an experiment.

We find that the most consistent factor that predicts aggregate patterns of climate skepticism in the public, and among Republican supporters specifically, are cues from Democratic party elites. We find that Democratic elite cues lead, rather than follow, public opinion on this topic (Hypothesis 1), and that they are contemporaneously correlated with public opinion even after controlling for other factors scholars have deemed important in shaping attitudes towards climate change (Hypothesis 2).

These findings are supported by our survey experiment. We find that polarizing party cues from Democratic (and Republican) elites increase climate skepticism among Republican Party supporters (Hypothesis 3). We found this to be the case with thin treatments and after decades of partisan polarization has already occurred. We did not find a consistently similar effect among Democratic Party supporters, though we must sound a word of caution on this latter point. It is possible that these results were hampered by a ceiling effect – Democratic supporters are already very supportive of the climate change consensus, so it is possible that our treatments could not move the needle any further. The backlash exhibited by Republican respondents to Democratic elite cues rivals the persuasive power of in-group cues from Republican elites in our sample, but it also appears to be attenuated by consensus cues signaling agreement between Democratic and Republican elites on climate science and the need for mitigation.

In short, we show that the story behind climate change polarization is similar to other political issues of the day: members of the public were exposed to a large volume of partisan messages on climate change as the issue grew in salience – in this case primarily from Democratic elites – and formed their opinions accordingly. This work joins an emerging literature on the role of the media and elite cues in climate change polarization (Carmichael and Brulle Reference Carmichael and Brulle2017; Guber Reference Guber2013; Merkley and Stecula Reference Merkley and Stecula2018; Tesler Reference Tesler2018) and work showing the persuasive influence of out-group party cues (Berinsky Reference Berinsky2009; Bischof and Wagner Reference Bischof and Wagner2019; Feddersen and Adams Reference Feddersen and Adams2018; Goren, Federico and Kittilson Reference Goren, Federico and Kittilson2009; Nicholson Reference Nicholson2012).

There are a number of important implications from these findings. First, party elites who strongly identify with the scientific consensus on climate change or other issues must weigh the costs and benefits of aggressively communicating their stance in the mass media. The rising prevalence of party elites in news coverage of climate change was inevitable at some level because of the need for large-scale policy action, but this finding has implications for other scientific issues, such as the safety of genetically modified organisms and vaccines. Efforts to bring these issues into the realm of elite conflict will almost surely lead to polarization as an unanticipated consequence.

Secondly, emphases on ideology and motivated cognition, while important to understanding why it is difficult to persuade Republicans and conservatives of the perils of climate change, is perhaps of more limited utility in helping us explain how we got to this point in the first place. Republican supporters were not always so skeptical of climate change. They listened to, and formed opinions based on, signals from trusted opinion leaders within their communities. By viewing the roots of climate change skepticism primarily in deep-seated ideological and value constructs, we minimize the degree to which elites can shape those constructs. It also means that these elites can turn the tide by providing a consensus in support of climate action. Although our experiment did not find a de-polarizing effect of a consensus cue treatment, a stronger treatment featuring highly respected Republican officials may have had more success.

Lastly, the potentially prominent role of party elites in the formation of public attitudes on climate change suggests scholars should invest less time and resources into identifying messaging strategies to mobilize support for the climate consensus, and more on understanding the motivations and behavior of party elites. Finding ways to mobilize an elite consensus across partisan lines is perhaps the most promising strategy to bring public opinion in line with the scientific consensus on climate change.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QKATSL and online appendices at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000113.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Paul Quirk, Richard Johnston, Fred Cutler, Stuart Soroka, Christopher Wlezien, Josh Pasek, Brendan Nyhan, Philip Habel, Yphtach Lelkes, and members of the UBC Comparative-Canadian Workshop for helpful feedback at various stages of the project. Thanks also to Mark Warren and Spencer McKay for generously including our questions as part of their larger survey for an unrelated project. The survey experiment was approved by the UBC Behavioral Research Ethics Board [protocol # H19-00311]. This project was funded by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada [grant # 767-2015-2504 and 752-2015-2536; and Insight grant # 12R06693].