In recent years immigration has become a salient issue in public debates in Europe. This is in no small part related to a substantial increase in immigration that most affluent European countries have experienced since 1990. In most of these countries, the proportion of the population that is foreign born has increased considerably during this period, while the recent refugee crisis has further added to these pressures.

This rising immigration has had profound effects on politics in Europe. The discourse of far-right parties has increasingly emphasized the negative consequences of immigration for the economy and society (Afonso and Rennwald Reference Afonso, Rennwald, Manow, Palier and Schwander2018; Stockemer and Barisone Reference Stockemer and Barisione2017). Not only has this trend been linked to the electoral success of extreme right parties (Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2008), but it has also reconfigured mainstream politics as parties have tried to respond to growing concerns about immigration (Abou-Chadi Reference Abou-Chadi2016; Abou-Chadi and Krause Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2018). One of those concerns, which has figured prominently in the media and political discourse, is the potential consequences of immigration for the welfare state. Political actors and the media have focused heavily on the fiscal effects of immigration, namely the question of the net impact of immigration on public finances.

Consequently, citizens have been exposed to conflicting messages. Some sources claim that immigrants are a drain on public finances, while others argue that immigrants' net contribution is positive. How does this debate influence public opinion on the welfare state? Does the exposure to negative frames of immigration undermine support for the welfare state, and do positive frames have the opposite effect?

The existing literature on the link between immigration and the welfare state does not offer a direct answer to this question because it focuses predominantly on the effects of the scale of immigration (for example, Alesina and Glaeser Reference Alesina and Glaeser2004; Brady and Finnigan Reference Brady and Finnigan2014; Finseraas Reference Finseraas2008), rather than the framing of its costs and benefits. The general literature on framing is helpful in so far as it tells us that people tend to respond to frames (for example, Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007b; Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016), but its focus on issue frames does not offer clear insights into the question of how clearly valenced frames (that is, outlining positive or negative aspects) influence public opinion. This article contributes to both of these literatures by focussing on the microfoundations of the relationship between immigration and the welfare state. Information on immigration is hardly ever presented in fully neutral terms, and even information on the stock or flows of immigrants is often communicated through partisan lenses. If we want to understand how immigration affects welfare support, we need to pay attention to how citizens process this information and how this in turn affects their welfare policy preferences.

To this end, we draw on the literature from psychology, and specifically research on negativity bias (Kahneman and Tversky Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979; Rozin and Royzman Reference Rozin and Royzman2001) and the sequencing of negative and positive information (Boydstun, Ledgerwood and Sparks Reference Boydstun, Ledgerwood and Sparks2017; Ledgerwood and Boydstun Reference Ledgerwood and Boydstun2014; Sparks and Ledgerwood Reference Sparks and Ledgerwood2017). In line with this literature, we hypothesize that negative frames regarding the impact of immigration undermine welfare support, while positive frames have little or no effect. Individuals take less notice of positive frames, and the effect of such frames can be further undermined by previous exposure to negative frames, which tend to stick longer in people's minds.

We test this hypothesis using survey experiments on over 9,000 individuals in Germany, Sweden and the UK. We focus on these countries for two reasons. First, in each case, a substantial proportion of the population is foreign born (12–15 per cent) and the costs and benefits of immigration have been the subject of recent heated political debates. In the UK, immigration was a key issue in debates leading up to the EU Referendum and the subsequent negotiations on the terms of Brexit. In Germany and Sweden concerns about immigration have been amplified by the 2015 refugee crisis. The decision of the German and Swedish governments to accept a large number of refugees has encountered considerable opposition at home and contributed to the growing success of far-right parties that have campaigned on an anti-immigrant platform.

Secondly, these countries depict the three worlds of welfare capitalism (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990). The institutional structure of the welfare regime may influence how the public perceives the link between immigration and welfare spending. Thus, although our theoretical argument suggests that negative framing of immigration will reduce support for higher spending everywhere, it is possible that the level of support will vary across the welfare regimes. Sweden's universal welfare regime gives immigrants comparatively easy access to benefits, which may generate perceptions that immigrants benefit disproportionately from the welfare state and thus increase opposition to greater spending (c.f. Fietkau and Hansen Reference Fietkau and Hansen2018; Hjorth Reference Hjorth2016) more than in the other two countries. The criteria for accessing benefits for immigrants are stricter in Germany and the UK. Germany's insurance-based regime is also less generous to those who did not pay into the system, while the UK's liberal regime is less generous overall.

Our analysis shows that negative framing of immigration has a strong effect on support for welfare spending in all three countries. Although there is some evidence that this effect is amplified for people who hold anti-immigrant and anti-welfare attitudes or feel insecure about their financial prospects, on the whole negative framing applies generally across the population. As expected, the effect of positive framing is significantly weaker and does not strengthen support in any of our countries. We also find differences in the size of the effect across countries that are in line with our reasoning about the influence of regime types.

These findings have clear implications for the politics of welfare reform in Europe. They suggest that as long as immigration remains one of the key issues in national politics, it might be much easier to foster coalitions that support welfare state retrenchment than coalitions that support further expansion of the welfare state.

Immigration and support for welfare spending

Since the publication of Alesina and Glaeser's seminal book (Reference Alesina and Glaeser2004), there has been increased academic interest in the relationship between immigration and the welfare state. Alesina and Glaeser argued that racial and ethnic heterogeneity in the United States undermines support for redistribution, and that this is the main reason why the United States does not have a generous welfare state. Minorities, they maintain, are seen as benefiting disproportionately from the welfare state, which makes it difficult to build solidarity and broad-based support for redistribution.

Although this argument about the trade-off between heterogeneity and redistribution has received strong empirical support in the United States, the findings for Europe have been less clear. While some studies find that race or ethnicity affect welfare support (Harell, Soroka and Iyengar Reference Harell, Soroka and Iyengar2016), others suggest that different political and economic institutions have a mediating impact (Larsen Reference Larsen2011; Mau and Burkhardt Reference Mau and Burkhardt2009). Commonly, the literature examines how the stock or flow of immigrant populations affects aggregate support for the welfare state. The findings are far from consistent. Some analyses find evidence that increased immigration has a negative effect on support for redistribution (Dahlberg, Edmark and Lundquist Reference Dahlberg, Edmark and Lundquist2012; Eger Reference Eger2010; Schmidt-Catran and Spies Reference Schmidt-Catran and Spies2016; Senik, Stichnoth and Straeten Reference Senik, Stichnoth and Straeten2008). Others find some support for the compensation hypothesis, which posits that higher levels of immigration provoke feelings of economic insecurity, which increases support for welfare spending (Brady and Finnigan Reference Brady and Finnigan2014; Burgoon, Koster and van Egmond Reference Burgoon, Koster and van Egmond2012; Finseraas Reference Finseraas2008).

A common denominator of these studies is their reliance on cross-sectional data, which largely leaves unspecified the causal mechanisms behind individual attitude formation. More recent scholarship has tried to address this criticism by using survey experiments. These studies more explicitly test the effect of information about immigration on individual attitudes about the welfare state (Alesina et al. Reference Alesina, Miano and Stantcheva2018; Naumann and Stoetzer Reference Naumann and Stoetzer2017, Runst Reference Runst2017). However, in most cases the focus is still on the effect of the size of the immigrant population on welfare state support.Footnote 1 Respondents are typically asked to evaluate the number of immigrants or primed with the correct number of immigrants, and then asked about their support for various aspects of the welfare state. On the whole, these experimental studies find no direct uniform effect of immigration on support for redistribution, although they suggest that the effect may vary according to income, education or exposure to labour market risks (Naumann and Stoetzer Reference Naumann and Stoetzer2017; Runst Reference Runst2017).

One potential reason why these studies find no strong effect of immigration is that respondents may not see an immediate link between immigration and redistribution. Even if they are made aware of the number of immigrants in their country, they may perceive that number differently or may not find that information immediately relevant when answering the question about their support for redistribution. We argue that a more appropriate assessment of the effects of immigration on welfare state support is to confront respondents with more direct information about the economic costs and benefits of immigration. An explicit mention of immigrants' fiscal impact is more likely to trigger considerations about the welfare state, including its sustainability (socio-tropic concerns) or higher taxes and competition for welfare services (self-interest). Political actors and the media are aware that this type of information elicits strong responses and use it frequently when addressing the public. Indeed, as Alesina and Glaeser (Reference Alesina and Glaeser2004) have shown in the case of the United States, conservative politicians and media outlets have instrumentally used information about the costs of different ethnic groups to activate natives' racial prejudices, undermine redistributive policies and mobilize political support.Footnote 2 Far-right parties in Europe have relied on a similar strategy and tried to portray immigrants as exploiting the welfare system.

Information about the costs and benefits of immigration is more likely to be consequential than information about the number of immigrants not only because it makes the link between immigration and redistribution more transparent, but also because it is often presented through valenced frames. Such frames indicate a clear standpoint and emphasize either the negative or positive aspects of an issue. We know from research in psychology and communication studies that valenced frames tend to be more effective at influencing attitudes than neutral frames because they present information in a more accessible way (Baumeister et al. Reference Baumeister2001; Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007a; Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007b). Political actors and the media regularly rely on valenced frames when discussing the economic effects of immigration. Depending on the source and the methodology used, immigration has been portrayed as either being a drain on the budget and public services or having a positive net fiscal contribution. Yet we know little about the effects of such frames on citizens' attitudes. Does information about the economic consequences of immigration affect attitudes towards redistribution and the welfare state? And does valence of the frames matter? The next section outlines our theoretical reasoning and the hypotheses we test using the survey experiment.

Framing effects and negativity bias

Research on public opinion has shown that how political actors and the media frame their communication affects citizens' attitudes. We know that citizens' perceptions are affected by the way in which the media describes an issue, policy or candidate (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007b; Gross Reference Gross2008). For example, a hate group rally is perceived more favourably if it is framed in terms of free speech rather than as a threat to public safety (Nelson, Clawson and Oxley Reference Nelson, Clawson and Oxley1997a). Attitudes towards government spending on the poor depend on how the consequences of such policies are represented (Sniderman and Theriault Reference Sniderman, Theriault, Saris and Sniderman2004), while support for aggregate government spending is affected by whether the support is framed in general or specific terms (Jacoby Reference Jacoby2000).

Different mechanisms have been identified to explain the effect of framing on public opinion. The information in a frame may induce learning and subsequently change an individual's opinion on policy. Alternatively, a frame may emphasize certain considerations of an issue or policy, thus increasing their weight and making them more relevant. Finally, the media and political actors may prime an issue to bring associated beliefs to the forefront of consideration (Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016).

While this research has demonstrated that frames have a powerful effect on public opinion, the focus has been predominantly on issue frames. Such frames typically include different content, which makes it difficult to separate the effects of that content from the effects of valence alone (positive vs. negative) (Boydstun, Ledgerwood and Sparks Reference Boydstun, Ledgerwood and Sparks2017). Yet, in competitive democracies citizens are often exposed to valenced frames that do not necessarily emphasize different aspects of an issue, but simply contain conflicting information that stresses either positive or negative consequences.

Information on the fiscal impact of immigration is one such case. For example, in the UK citizens have been exposed to conflicting messages from different media outlets. While the Guardian cited a study arguing that immigrants contributed GBP 20 billion more in taxes than they received in welfare payments over ten years (4 November 2014), the Daily Mail referred to a study that claims that the annual net cost of immigrants is GBP 17 billion (17 May 2016). Similarly, in Germany some outlets have emphasized that each foreigner contributes EUR 3,300 more in taxes and premiums than they receive in state support (Sueddeutsche Zeitung, 27 November 2014), while others have reported that on average each foreigner represents a net cost of EUR 1,800 (Bild, 1 February 2015).Footnote 3

How do citizens respond to such valenced frames? Drawing on research from psychology and behavioural science, and in particular the notion of negativity bias, we argue that the effects of such valenced frames are asymmetric and that negative frames have a stronger impact on citizens' attitudes than positive frames. Psychologists have shown that under many conditions, humans have an innate predisposition to attend to valence and to give greater weight to negative than positive information (Baumeister et al. Reference Baumeister2001; Rozin and Royzman Reference Rozin and Royzman2001). Since Kahneman and Tversky's (Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979) seminal work on prospect theory, which suggests that negative frames are more powerful than positive frames in shaping people's judgements, a vast multidisciplinary literature has demonstrated this principle in a range of domains. For example, public perceptions of the economy have been shown to be affected more strongly by negative than positive economic news coverage (Soroka Reference Soroka2006). Job placement programmes are evaluated more positively when they are discussed in terms of their success rate rather than their failure rate (Davis and Bobko Reference Davis and Bobko1986). Negative information has also been shown to play a greater role in evaluations of US presidential candidates and political parties as well as voter turnout (Holbrook et al. Reference Holbrook2001). Similarly, negative political advertising has a stronger effect than positive advertising, and people tend to remember it longer (Johnson-Cartee and Copland Reference Johnson-Cartee and Copland1991).

There are several explanations for this evident presence of negativity bias. Some theories posit that negativity bias is a built-in predisposition or an inherent characteristic in the central nervous system. The desire for survival implies that humans may be genetically predisposed to pay more attention to negative events. In this line of reasoning, some accounts suggest that negativity bias operates automatically at an early (evaluative-categorization) stage of reasoning (Ito et al. Reference Ito1998). Others argue that negative information is more potent because of the much lower frequency of negative than positive events (Lewick, Czapinski and Peeters Reference Lewick, Czapinski and Peeters1992). Yet others emphasize the contagion effect and argue that negative events and information ‘may inherently be more contagious, generalize more to neighboring domains, and be more resistant to elimination’ (Rozin and Royzman Reference Rozin and Royzman2001, 315). The different possible reasons notwithstanding, extensive empirical studies have demonstrated the dominance of negativity bias and the fact that negative information is more salient and more memorable. We therefore expect that:

Hypothesis 1 The effects of the negative framing of immigration will be more powerful than the effects of positive framing, and thus have a greater impact on welfare attitudes.

More specifically, we expect that:

Hypothesis 2a Respondents exposed to the negative framing of immigration show significantly less support for welfare spending than those in the control group, who are not exposed to any information about immigration.

People who receive information about the fiscal costs of immigration should be more likely to perceive immigrants as being the main beneficiaries of the welfare system. This should lead to reduced aggregate support for welfare spending either because of reduced solidarity towards the out group or because of self-interest as the net fiscal burden of immigration may be associated with potentially higher taxes.

If negative information about immigration generates lower support for welfare spending relative to the control group, should we expect positive information to have the reverse effect? Two reasons lead us to believe that this is unlikely to be the case and that the effects of positive information should be negligible. The first is associated with the literature on negativity bias, which suggests that positive frames are weaker and less memorable, and thus are less likely to shape attitudes. The second is related to the more recent literature in psychology that examines the effects of the sequencing of positive and negative messages. This literature shows that negative frames tend to be stickier than positive frames. They lodge in people's mind for longer, so reframing from negative to positive is more difficult than the other way around (Boydstun, Ledgerwood and Sparks Reference Boydstun, Ledgerwood and Sparks2017; Ledgerwood and Boydstun Reference Ledgerwood and Boydstun2014; Sparks and Ledgerwood Reference Sparks and Ledgerwood2017). Because immigration is such a salient topic in advanced countries, our respondents are likely to have already encountered some messages about its fiscal impact (Allen and Blinder Reference Allen and Blinder2013). If negative information is indeed more memorable and stickier than positive information, then respondents who were previously exposed primarily to messages that emphasize the negative fiscal impact of immigration may find it more difficult to believe subsequent information that immigrants contribute more to the welfare system than they take out. Correspondingly, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2b Respondents exposed to the positive framing of immigration do not show significantly stronger support for welfare spending than the control group.

It is important to note here that our understanding of the framing effect is not the same as persuasion via belief change. As Nelson, Oxley and Clawson (Reference Nelson, Oxley and Clawson1997b) show, although the two concepts are related, they differ both theoretically and empirically. Persuasion via belief change is evident when respondents believe the information that is discrepant with their prior attitude, and which then leads them to change their attitudes accordingly. The underlying rationale is that such information affects opinion because it is new and thus not already part of the respondents' knowledge or convictions. In contrast, framing effects cannot be reduced to new information only. Instead, frames also ‘operate by activating information already at the recipients’ disposal, stored in long term memory’ (Nelson, Oxley and Clawson Reference Nelson, Oxley and Clawson1997b, 225). Frames, therefore, may not always offer new information, but they influence people's weighting of different considerations and the perceived relevance of a particular belief for policy attitudes. This conceptualization of framing effects can be verified empirically. If memory activation were not part of the framing effects, the effect of our negative framing would be evident only among respondents who had no previous exposure to negative information about the costs of immigration. While our study lacked the resources to expose our respondents to such information prior to the experiment, data on newspaper readership offer a reasonable proxy for previous exposure. Controlling for readership of newspapers that tend to propagate an anti-immigration sentiment, we find no appreciable difference in the magnitude of the framing effects across the two groups (see Appendix Table A12). This confirms the idea that the framing effect entails weighting both new and previously acquired information, and that it is not simply belief change due to new information.

Moderating Effects

The framing literature tells us that the strength of the frame is an important determinant of its effectiveness (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007a; Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007b). Frames that provide clear and unambiguous information are more easily accessible and are thus more likely to be consequential for attitude formation. Because a statement about the fiscal impact of immigration represents a strong frame and makes the link between immigration and redistribution immediately obvious, we expect to see clear effects of this frame at the aggregate level.

However, it is possible that this effect may be further amplified by strong pre-existing attitudes or characteristics. As Chong and Druckman (Reference Chong and Druckman2007b, 120) argue, ‘individuals who possess strong attitudes are not only more likely to recognize which side of an issue is consistent with their values, but they are also more likely to engage in motivated reasoning’, which includes an inclination to evaluate new information in a way that supports their preconception and to devalue contrary evidence. Two types of such strong attitudes seem especially important for our study – anti-immigrant and anti-welfare attitudes. Individuals with such attitudes should be particularly susceptible to our negative frame that emphasizes the fiscal costs of immigration. Those who have clear anti-immigrant attitudes are more likely to believe information that immigrants are benefiting disproportionately from the welfare state, and this is likely to further strengthen those attitudes. Consequently, they should be less likely to support further welfare spending. Similarly, among respondents who receive the negative frame, those who are already critical of the size of the welfare state should be especially reluctant to support an expansion of welfare benefits because the frame further reinforces their belief that welfare costs are too high or that many people on benefits are not deserving. We believe these attitudes more effectively capture cognitive considerations and are thus more consequential than simple categories such as education, income or political leaning.

In addition, we consider expectations about economic prospects as another factor that may moderate the effect of our framing. Individuals who are worried about their economic prospects are more likely to end up being dependent on the welfare state and thus may see immigrants as competition for scarce resources. Theoretically, however, it is unclear whether such circumstances should amplify the effect of our negative framing. On the one hand, such individuals may support greater spending as they expect that they will need to rely on the welfare state more heavily in the future. On the other hand, they may be less supportive of welfare spending if they perceive immigrants as non-deserving or believe that a leaner welfare state would be less attractive to immigrants, which in turn might help reduce the perceived competition for welfare.

The survey experiment

To test how the framing of the impact of immigration affects support for welfare spending, we conducted survey experiments in Germany, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Our experiments were embedded in YouGov's regular Omnibus surveys. These surveys are administered online and respondents are recruited from YouGov's panels of 800,000 members in the UK, 320,000 in Germany, and 100,000 in Sweden. The samples drawn from these panels are representative of the national population based on age, region, gender, education, political interest and voting behaviour in the last election. Respondents are selected using active sampling to ensure that only those contacted are able to access the survey. The final sample sizes are 3,269 in the UK, 4,158 in Germany and 2,001 in Sweden. The smaller sample size in Sweden reflects the difficulty and cost of obtaining a large sample in a country with a smaller population. The surveys were fielded from 9–12 June 2017 in the UK, 14–17 August 2017 in Germany, and 22–29 September 2017 in Sweden.Footnote 4

For the main experiment, all individuals were primed with neutral information to prompt them to think about how the welfare state is funded and the relationship between taxation and welfare spending:

(Priming information): The government provides a range of social benefits and services to address the needs associated with unemployment, sickness, education, housing, family circumstances, and retirement. Such benefits and services are financed through taxation and national insurance and all legal residents in [country name] are entitled to receive them. To spend more on social benefits and services, the government may need to increase taxes and national insurance contributions.

Individuals were then randomized into three groups. The first group received information that framed the economic impact of immigration on the welfare state in a negative light:

(Negative frame): Because immigrants are also entitled to receive social benefits and use public services, the economic implications of immigration are an increasing concern. Recent research shows that immigration is a drain on government finances – on average, immigrants take out significantly more from the welfare state in social benefits and services than they contribute in taxes and national insurance.

The second group received the opposite information:

(Positive frame): Because immigrants are also entitled to receive social benefits and use public services, the economic implications of immigration are an increasing concern. However, recent research shows that immigration is in fact a boost to government finances – on average, immigrants contribute significantly more to the welfare state in taxes and national insurance than they take out in social benefits and services.

The final group served as our control group and received only the priming information.

Every group was then asked our dependent variable question. Previous research has shown that when individuals are asked about increasing social spending without being made aware of the potential costs, then support for spending tends to be overstated (Margalit Reference Margalit2013). We therefore assess support for social spending by referring to the potential costs of any increase. The following question, with five possible responses ranging from ‘strongly support’ to ‘strongly oppose’, serves as our dependent variable:

Do you support an increase in government spending on social benefits and services even if this may lead to higher taxes?

The treatment groups therefore differ only in the framing information that they received. Randomization ensures that all three groups are nearly identical (see Tables A6–A8) in all other respects in terms of observable and unobservable variables that may confound cross-group comparison.

Strong pre-existing attitudes regarding immigrants and welfare spending more broadly may amplify the effect of our frames. Similarly, those who are less economically secure may view immigrants as competitors for welfare benefits. Therefore, prior to the treatment we placed three additional questions on the survey to investigate the conditional effect of our frames. The wording of each of these questions was inspired by survey experiments undertaken by Ford (Reference Ford2016) and Margalit (Reference Margalit2013). The first question measures the extent to which individuals hold anti-welfare preferences that may amplify negative information regarding the welfare state.Footnote 5 The second question assesses pre-existing anti-immigrant attitudes.Footnote 6 The final question is designed to examine whether economic insecurity could moderate our treatment effects.Footnote 7

Results

Figure 1 shows the distribution of support for increased welfare spending. The dependent variable has been recoded into three categories to simplify the presentation of our results and make the graphs more readable.Footnote 8 Figure 1 shows that there is substantial variation in support for increased welfare spending both between countries and between treatment groups. In general, support for increased spending is highest in the UK and lowest in Sweden. At first glance, this may be surprising given what we know about the respective welfare regimes (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990). However, our question asks respondents if they favor increased spending even if it leads to higher taxes. In Sweden, welfare expenditure is already high at 27.1 per cent of GDP, compared to 21.5 per cent in the UK and 25.3 per cent in Germany (OECD 2018).Footnote 9 Therefore, it is possible that Swedish respondents broadly believe that spending is high enough already, while UK respondents believe that there is greater capacity for increased expenditure. In addition, the UK has the lowest income tax in all categories of income, and hence the prospect of higher taxes as a price for increased spending may not appear so unacceptable.Footnote 10 In any case, this should not affect our substantive results since we are concerned with how framing changes support for spending rather than the prevalence of support for increased expenditure in general.

Figure 1. Support for increased social spending by treatment group

Note: Stata graph schemes designed by Bischof (Reference Bischof2017).

While there is a clear difference in the overall level of support for increased welfare spending across the three countries, the pattern of support across the treatment groups within countries is remarkably similar. Figure 1 also shows that respondents in the control group were more likely to support an increase in spending in each country. The difference between the control group and the negative treatment group is largest in the UK at 13 percentage points. In Sweden the difference is 11 points and in Germany 6 points. This provides preliminary support for our hypothesis that negative framing of the impact of immigration leads to reduced support for welfare spending. It is also noticeable that individuals in the positive treatment group in each country have lower levels of support for increased spending than the control group. This may indicate that even a mere mention of immigration triggers considerations that reduce welfare support. While this is an interesting outcome, at this stage it is unclear whether the level of support for increased spending among the positive treatment group is significantly different to that of the control group. In the next section we turn to a more formal test of our hypotheses.

Regression Models

To formally test our hypotheses, we regressed our dependent variable on a categorical indicator of a respondent's treatment group. The control group is specified as the reference category. As the dependent variable is categorical, we use an ordered logit model with post-stratification weights. Given the experimental protocol and the fact that our samples are weighted to be representative, spurious correlation is unlikely to be a problem in our models. We therefore follow advice by Mutz (Reference Mutz2011, chap. 7) to keep the model simple and not to include control variables.Footnote 11 In subsequent models, which examine the moderating effects of pre-existing attitudes, we interact those attitudes with the treatment. The models are specified as follows:

with ![]() $Y_i^* $ capturing individuals' support for increased welfare spending, i indexing individuals, and εi representing an error term. To examine the conditional effect of pre-existing attitudes on our treatments, additional models are estimated containing the interaction terms β 2TREATMENT GROUP × ANTI-WELFARE, β 3TREATMENT GROUP × ANTI-IMMIGRATION and β 4TREATMENT GROUP × ECONOMIC INSECURITY. The interaction models also contain all constitutive terms. Separate models are estimated for each country. The results can be found in Tables 1–3.

$Y_i^* $ capturing individuals' support for increased welfare spending, i indexing individuals, and εi representing an error term. To examine the conditional effect of pre-existing attitudes on our treatments, additional models are estimated containing the interaction terms β 2TREATMENT GROUP × ANTI-WELFARE, β 3TREATMENT GROUP × ANTI-IMMIGRATION and β 4TREATMENT GROUP × ECONOMIC INSECURITY. The interaction models also contain all constitutive terms. Separate models are estimated for each country. The results can be found in Tables 1–3.

Table 1. Immigration framing and support for redistribution in Germany

Note: ordered logit regressions, coefficients are log odds with standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Table 2. Immigration framing and support for redistribution in Sweden

Note: ordered logit regressions, coefficients are log odds with standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Table 3. Immigration framing and support for redistribution in the UK

Note: ordered logit regressions, coefficients are log odds with standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

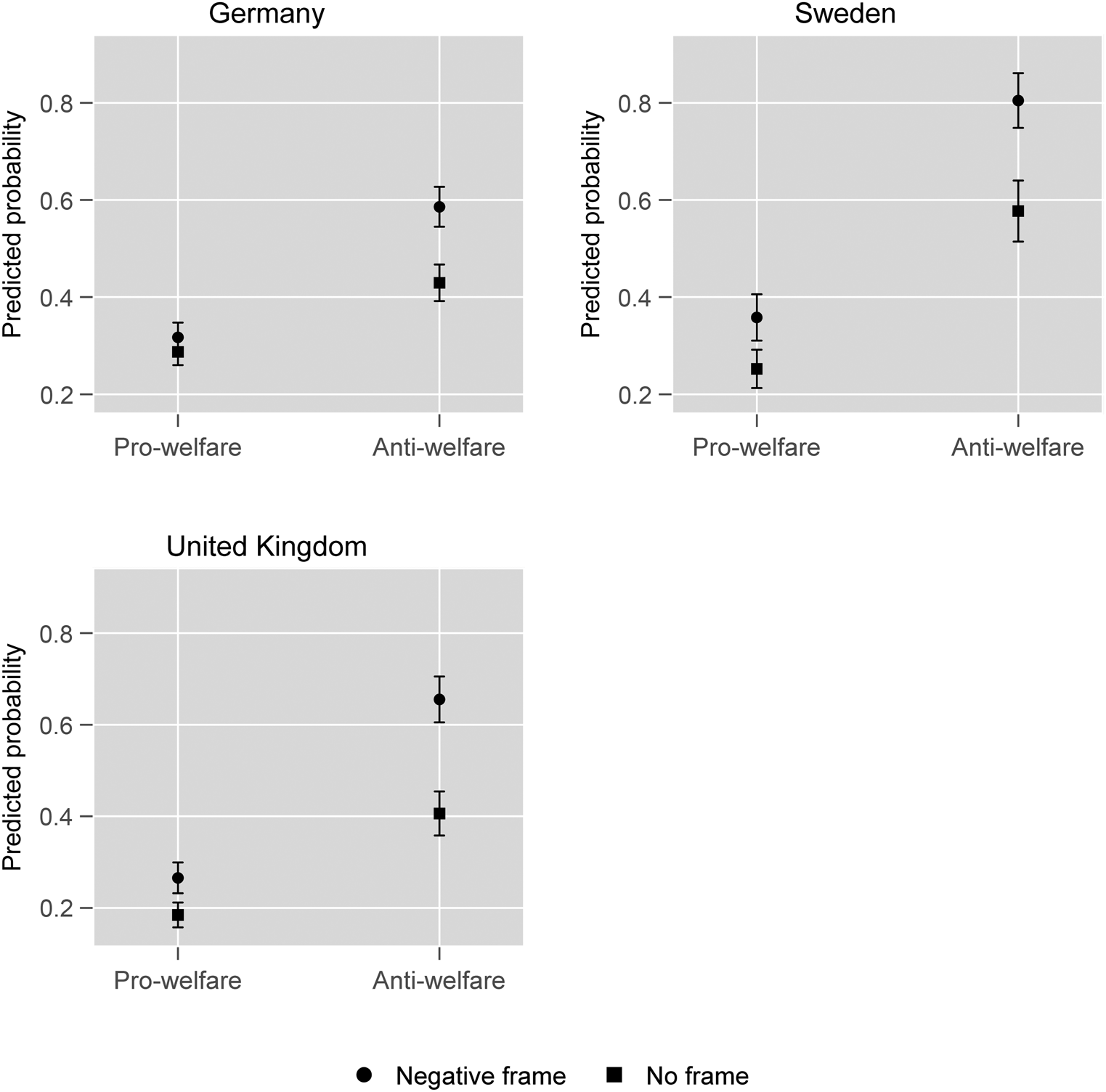

The main models (Models 1, 5 and 9) show that negative framing of immigration is associated with reduced support for greater welfare spending in all countries. Figure 2 depicts the predicted probabilities of supporting or opposing greater spending for the different groups. The differences between the negative frame and the control group are stark in each country. In Germany, individuals in the negative treatment group have a 44 per cent probability of opposing increased spending, compared to 36 per cent in the control group. The differences are even greater in Sweden (53 vs. 38 per cent) and the UK (42 vs. 28 per cent). These results provide strong support for Hypothesis 2a. Individuals who received the negative framing concerning the impact of immigration on the welfare state are much less likely to support greater spending than respondents who received no framing. This figure also suggests some cross-country differences in the level of support for greater spending within the negative frame group. In line with the reasoning about the impact of welfare regimes outlined in the introduction, Sweden leads the way with over half of respondents in this group unwilling to support greater spending.

Figure 2. Predicted probability of opposition or support for increased welfare spending by treatment group

The results also provide some support for Hypothesis 2b. Drawing on the literature on negativity bias, we expected that positive framing of the impact of immigration would be weaker than negative framing. This is because negative information tends to be more salient and memorable than positive information (Ledgerwood and Boydstun Reference Ledgerwood and Boydstun2014; Boydstun et al. Reference Boydstun, Ledgerwood and Sparks2017; Sparks and Ledgerwood Reference Sparks and Ledgerwood2017). Given the salience of immigration as an issue in contemporary politics, we also expected that respondents would already have encountered some negative messages concerning the impact of immigration. As negative messages tend to be stickier, overturning them with positive information can be challenging.

Figure 2 shows that, as expected, the positive frame is weaker than the negative frame in all countries.Footnote 12 In addition, individuals in the positive treatment group are less likely to support increased welfare spending and more likely to oppose it than respondents in the control group. However, it is important to note that this difference in support for increased spending between the positive treatment group and the control group is statistically significant only in Sweden (see Tables 1–3). The finding that positive information about the impact of immigration can reduce support for welfare spending may seem anomalous. However, cultural and economic factors (Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2007; Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015; Sides and Citrin Reference Sides and Citrin2007; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino2019) as well as prior media coverage of immigration are likely to play a role in shaping how individuals perceive the impact of migrants. Previous research has shown that negative priors about immigration are widespread (Alesina et al. Reference Alesina, Miano and Stantcheva2018) and that immigration is usually presented in an overtly negative tone in the media (Abrajano, Hajnal and Hassel Reference Abrajano, Hajnal and Hassel2017; Allen and Blinder Reference Allen and Blinder2013). As these negative messages tend to be more powerful due to negativity bias, it is conceivable that even the use of the term ‘immigrants’ in a positive context may trigger a negative response among respondents. Further support for this proposition can be found in studies of the electoral performance of anti-immigrant political parties. These studies show that simple exposure to media coverage of immigration-related stories – whether positive or negative – increases support for anti-immigration parties (Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart Reference Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2007; Burscher, van Spanje and de Vreese Reference Burscher, van Spanje and de Vreese2015).

Although this is a plausible explanation, it is possible that the negative effect of the positive treatment is a methodological artifact in the sense that the positive frame may not have been perceived as such. The pairwise contrasts of the treatment coefficients (Appendix Table A2) suggest that this is not the case and confirm that the effects of the negative and positive treatments are distinct from each other in all cases.

Two further tests were used to examine if the positive frame may not be perceived as positive. The first was a pre-test survey using a convenience sample of students undertaken at King's College London; 69 per cent of those who received the negative frame believed that it was accurate, compared to 66 per cent of those who received the positive frame. Since students generally display more pro-immigrant attitudes, we would expect the difference in the perceptions of the accuracy of these frames to be even more evident in the broader population. But since our sample in this pre-test was small (79 students), we have also undertaken a post-experiment manipulation check in the UK to verify if the positive treatment was perceived as such.Footnote 13 Respondents in each treatment group were subjected to the same experimental protocol as set out above. An additional question was added at the end of the experiment, asking whether respondents believe that immigrants contribute more in taxes than they receive from the welfare state. The results of the manipulation check can be found in Table 4. They show clear differences between the positive and negative treatment groups: 42.3 per cent of respondents who received the negative frame stated that they believe immigrants contribute more than they cost, compared to 53.7 per cent of those in the positive frame group. A formal test of these differences can be found in Appendix Table A3. The results of this logit model show that respondents in the negative frame group are significantly less likely to believe that immigrants contribute more than they cost than those in the positive frame group. These results lead us to conclude that both the negative and positive frames were correctly perceived by respondents.

Table 4. Manipulation check frequencies (%)

Note: respondents were asked the following question: ‘Do you believe that, on average, immigrants contribute more in taxes and national insurance than they receive in benefits and services from the welfare state?’

No, Immigrants cost more than they contribute

Yes, immigrants contribute more than they cost

Fieldwork carried out by YouGov, 20–21 February 2019.

Overall, we find support for each of our hypotheses. Negative frames are more powerful than positive frames (Hypothesis 1). The results also show that negative framing of the impact of immigration reduces support for increased welfare spending (Hypothesis 2a), but positive framing has little effect (Hypothesis 2b). In the next section we consider the conditional impact of our treatments.

The Conditional Effect of Negative Framing

While the results presented above provide strong support for our theoretical argument, it is possible that the effect of negative framing could be stronger for individuals who hold specific beliefs about welfare and immigration. The first conditional effect we consider is whether individuals hold anti-welfare attitudes.Footnote 14 Some people believe that welfare benefits are intrinsically wrong and that many benefit claimants are undeserving. These individuals are likely to be more susceptible to negative framing as it will reinforce their belief that many people unjustly claim benefits. We therefore interacted our treatment group variable with the binary indicator of anti-welfare attitudes.Footnote 15

The results can be found in Models 2, 6 and 10 of Tables 1–3. The interaction terms in these models are all negative and statistically significant for the respondents who received the negative frame. This supports our argument that negative frames are more powerful. As the results from the positive frame group are not significantly different from those of the control group, and in order to enhance the clarity of the graphs, Figures 3, 4 and 5 contain only the results for the negative frame group and the control group. To further ensure that the graphs are readable, we only plot the predicted probabilities for opposition to welfare spending.

Figure 3. Predicted probability of opposition to increased welfare spending in the negative treatment group conditional on pro/anti-welfare attitudes

Figure 4. Predicted probability of opposition to increased welfare spending in the negative treatment group conditional on attitudes towards immigrants

Figure 5. Predicted probability of opposition to increased welfare spending in the negative treatment group conditional on perceived economic insecurity

Figure 3 shows the predicted probabilities of opposing increased welfare spending depending on an individual's pre-existing welfare attitudes. In comparison to the control group, respondents exposed to the negative frame always have a higher probability of opposing increased welfare spending. However, as Figure 3 suggests, this difference in probability between the treatment and control groups is much more pronounced for respondents holding anti-welfare attitudes. The likelihood of opposing welfare spending for this group is also always substantially higher than for respondents who do not hold anti-welfare attitudes. For example, in Germany individuals who received the negative frame and hold anti-welfare attitudes have a 59 per cent probability of opposing increased welfare spending, compared to 32 per cent of those who do not hold such attitudes.

It is also likely that people who hold negative predispositions towards immigrants are more receptive to negative framing regarding the impact of immigration. To examine this possibility, we interacted a dummy capturing anti-immigrant attitudes with our treatment group indicator.Footnote 16 Figure 4 shows that the probability that an individual in the negative treatment group will oppose higher welfare spending increases substantially for those harboring anti-immigrant attitudes. However, as Models 3, 7 and 11 in the tables show, this interaction is significant in Sweden and the UK, but not in Germany. This indicates that in Sweden and the UK the effect of the negative treatment is further amplified for respondents who hold anti-immigrant views. In all three countries, opposition to welfare spending is higher among those who hold anti-immigrant views regardless of whether they were in the negative frame or control group. In each country, individuals who received the negative frame were more likely to oppose increased spending if they also held pro-immigrant views. These results indicate that negative framing increases opposition to social spending among both pro- and anti-immigration individuals, though the size of the effect is greater among those who hold anti-immigrant attitudes in Sweden and the UK. Appendix Figure A3 provides further evidence of this result, showing the marginal effect of negative framing conditional on an individual's pre-existing attitudes towards immigrants.

Finally, if individuals are currently facing or expecting economic insecurity in the future, they may view immigrants as competition for welfare resources. Economically insecure respondents may thus be more susceptible to the negative frame. The results of the interaction between the dummy capturing economic insecurity and the treatment variable can be found in Models 4, 8 and 12 of the tables and are illustrated in Figure 5.Footnote 17

In Germany and Sweden, the interaction is not statistically significant for any of the treatment groups. In contrast, Figure 5 shows that in the UK, among individuals who did not receive any frame, those who perceive themselves as economically insecure are less likely to oppose increased welfare spending.Footnote 18 However, for those in the negative frame group, perceived economic insecurity does not affect their opposition to welfare spending. In effect, the negative framing overrides perceptions of economic insecurity. The differences between the UK on the one hand, and Germany and Sweden on the other, are likely a result of the current welfare generosity and the type of immigration experienced in each country. Germany and Sweden have more generous welfare states than the UK, which may increase the perception of greater competition for resources in the latter. Furthermore, in 2016 Germany introduced stricter rules on the rights of EU migrants to access most welfare benefits, including requiring that an individual has lived in Germany for five years before they can make a claim. Restrictions on migrants' access to the welfare state are likely to have reduced the perception that they represent competition to the native population. The nature of immigration could also change perceptions of welfare competition in each country. The immigration debate in the UK focuses on economic migrants, mainly from EU countries, and their impact on the labor market and welfare services including benefits and housing. In Germany and Sweden, recent immigration debates have revolved around refugees from Syria and Afghanistan. These debates have tended to emphasize the cultural impact of immigration rather than the effect on the labor market. However, it is also important to note that economically secure individuals in the negative frame group were also more likely to oppose increased welfare spending than economically secure respondents in the control group. Further confirmation of this can be found in Figure A4, which shows the marginal effect of negative framing conditional on an individual's relative economic security. This suggests that although economic insecurity amplifies the effect of the negative framing of immigration, even those who do not face economic insecurity are not immune to it.

Taken together, these results indicate that the effect of negative framing can be exacerbated by other attitudes. Individuals who believe welfare claimants are likely to be undeserving, and those who hold negative predispositions towards immigrants, are more likely to oppose increased welfare spending if they received the negative frame in our experiment. However, in most instances, negative framing increases opposition to welfare spending irrespective of an individual's pre-existing attitudes and perceptions of economic insecurity. The results are also consistent with our theoretical argument: the effect of the negative frame of immigration on the welfare state is greater in these conditional models than the effect of the positive frame.Footnote 19 Overall, the results show that negativity bias can be a powerful influence on individual-level attitudes.

Conclusion

The impact of immigration on politics and society is one of the most salient issues in affluent democracies. The increased prominence of radical right parties, and the shifts on immigration policy that they have seemingly enforced on mainstream parties, have increased the importance of the issue (Abou-Chadi and Krause Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2018). One of the central debates surrounding immigration is its impact on government finances, principally via increased pressure on the welfare state. There is no consistent evidence regarding the impact of immigration on the welfare state, but the perception that immigrants are a strain on the welfare state remains, particularly among opponents of immigration.

In this research, we have tested whether the way in which the impact of immigration is framed can influence individual-level support for welfare spending. Using a survey experiment, we randomly assigned individuals in Germany, Sweden and the UK to receive either negative information regarding the impact of immigration, positive information or no information. The results show that while the differences in the level of welfare support/opposition may be regime related, the negative framing significantly reduced support for, and increased opposition to, greater welfare spending in all three countries. Furthermore, pre-existing anti-welfare and anti-immigrant attitudes amplified the effects of negative framing of immigration. However, the positive treatment did not increase support for welfare spending in our experiment.

We argue that the greater power of the negative treatment can be explained by negativity bias. Previous research shows that individuals appear to be predisposed to give greater weight to negative information (Baumeister et al. Reference Baumeister2001; Rozin and Royzman Reference Rozin and Royzman2001). Moreover, negative information is usually stronger and more memorable than positive information (Ledgerwood and Boydstun Reference Ledgerwood and Boydstun2014; Boydstun, Ledgerwood and Sparks Reference Boydstun, Ledgerwood and Sparks2017; Sparks and Ledgerwood Reference Sparks and Ledgerwood2017). This means that it is both more difficult to overturn negative preconceptions and easier to override previously held positive beliefs.

While the results support our central argument that negative framing of immigration reduces support for welfare spending, it should be noted that we do not know if this effect persists over time. Resource limitations prevented us from conducting a re-contact study. However, given that negative frames are likely to be stickier and more memorable than positive frames, there is reason to believe that the effects may not be transient.

Another concern is that the findings generated by our survey experiment may not perfectly reflect the real world, an issue emphasized by Barabas and Jerit (Reference Barabas and Jerit2010). Our respondents were not made aware of the exact source of information they were presented with. In the real world, the source of such information is often evident and may affect its credibility. Using actual newspaper articles or TV reports, rather than general framing, would have addressed this concern. However, directly comparable information was not readily available. While various articles and reports have emphasized either the costs or benefits of immigration, their measures of costs/benefits are rarely comparable.Footnote 20 Since our argument is that negative frames carry more weight than positive frames, it was imperative that the information about immigration provided to the two treatment groups was identical in everything apart from the direction. Consequently, we cannot exclude the possibility that the effects we found would be somewhat smaller in the natural setting, but we have no reason to believe that the direction of the effect would be very different.

These results have potentially significant implications for those engaged in debates about immigration. It is often believed that engaging with the evidence and presenting the generally positive economic impact of immigration will change public opinion. However, the tone of the immigration debate is overwhelmingly negative in most European countries. As individuals are innately predisposed to negative information and afford it greater weight, such positive accounts regarding the impact of immigration are easier to discount. This presents a formidable challenge to those on the pro-immigration side of the argument. A further implication of this research is that support for the welfare state may be more difficult to sustain if opponents consistently link social spending and immigration. If these beliefs become more widely held, overturning negative preconceptions about the nature of social expenditure will become increasingly difficult, which may present a threat to the sustainability of the welfare state.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/X0EC41 and online appendices at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000395.

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this research was provided by the British Academy (grant number: SG161954), the Social Sciences and Public Policy Faculty Research Fund at King's College London, and the Research Development Fund at the University of Sussex. We would like to thank the following for comments and advice on various aspects of this research: Damien Bol, Andrew Clark, Bernhard Ebbinghaus, Emmy Eklundh, Florian Foos, Mark Kayser, Johannes Lindvall, Elias Naumann, and participants at the University of Sussex Politics Research in Progress Seminar 2018, the European Political Science Association Conference 2018, Society for the Advancement of Socio-Economics Conference 2018, and the workshop on Inequalities and Preferences for Redistribution at the Paris School of Economics, 2019.