The late fifteenth century is often heralded as a world historic juncture that ushered in the exploration, and eventual exploitation, of the New World; the Columbian Exchange of crops, peoples and diseases; and an age of colonial rule by Europeans. While the New World discoveries were history changing in their significance for world economic and institutional development, Columbus's discovery of the New World in 1492 CE often overshadows another important circumnavigation that took place only six years later. When Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama sailed around Africa's Cape of Good Hope in 1498, this event was momentous for economic development in the Middle East and Central Asia, regions that long benefited from connecting markets in Western and Southern Europe with South and East Asia.

Both Columbus and da Gama were desperately seeking opportunities to trade with Asia when they began their risky journeys West and East, respectively. Up until that point, spices, textiles and other ‘Eastern’ commodities moved from China and India through Middle Eastern cities, like Aleppo and Cairo, before continuing to Venice or other European destinations. Da Gama's feat of exploration meant that Europeans would be able to create a route to Eastern ports, giving them direct access to valued commodities. Observers commenting at the time believed that Cairo and Mecca would be ‘ruined’ as a result (Frankopan Reference Frankopan2016, 222).Footnote 1 Cities that indirectly benefited from Middle Eastern trade were also concerned about the new developments. For example, it was believed that Venice would ‘obtain no spices except what merchants were able to buy in Portugal’ and a sense of ‘shock, gloom and hysteria’ set in among Venetians who believed that da Gama's discovery marked an end to their city's prosperity (Frankopan Reference Frankopan2016, 220–222).

What impact did European exploratory breakthroughs have on the economic development of the Middle East? Although historians have long suggested that Europe's Age of Exploration may have dampened growth in Middle Eastern societies, this conjecture has not been systematically tested. This is despite the fact that shocks to trade in the early modern period have been considered critical drivers of economic growth for Atlantic countries that benefited from the New World discoveries (Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2005). We examine Eurasian urbanization patterns as a function of distance to Middle Eastern trade routes before and after 1500 – the turning point in European breakthroughs in seafaring, trade and exploration. We find that cities proximate to historical Middle Eastern trade routes were larger in 1200 than areas further from those routes; this pattern reversed, however, between 1500 and 1800.Footnote 2 To address the issue of the endogenous development of trade routes, we exploit the fact that prior to European advances in seafaring, the world's most important trade routes connected land and sea choke points. We use the distance to lines connecting these choke points as an instrumental variable (IV) for actual trade routes. Taken together, our results suggest that Middle Eastern traders may have been some of the original ‘losers of globalization’.Footnote 3

Our findings help us understand when (and why) the Middle East fell behind Europe economically. Existing theories that seek to explain the ‘long’ divergence between the Middle East and Europe focus on the effects of Islamic law (Kuran Reference Kuran2010), Islam's outsized political influence relative to other world religions (Rubin Reference Rubin2017) or how cultural institutions common in Muslim societies may have hindered economic growth (Greif Reference Greif1994).Footnote 4 A separate stream in the literature focuses on the impact of political institutions in differentiating Europe from the Middle East, particularly military institutions common to the Muslim world (Blaydes and Chaney Reference Blaydes and Chaney2013; Blaydes Reference Blaydes2017) and the ways in which political fragmentation and representative institutions common in Latin Christendom encouraged European development (Cox Reference Cox2017; Stasavage Reference Stasavage2016). Yet religio-cultural and institutional arguments overlook the ways in which interactions between Europe and the Middle East contributed to divergent development outcomes.Footnote 5 Our findings suggest that while institutional advantages may have helped pave the way for European exploration, at least some of the reversal in economic fortune we observe for the historical trajectories of Muslim and Christian societies can be explained through a channel associated with changing global trade patterns, which are subject to sudden disruptions.

While our findings speak primarily to the rise and fall of cities in the Muslim world, the relevance of proximity to Muslim trade routes for the economic development of European cities also helps explain the “little” divergence in economic prosperity that occurred within Europe during the early modern period. A rich literature in political economy seeks to explain divergent growth trajectories within Europe (for example Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2005; Dincecco and Onorato Reference Dincecco and Onorato2016; Stasavage Reference Stasavage2014; Van Zanden Reference Van Zanden2009). We argue that southern Europe had long benefited from proximity to Middle Eastern trade routes – an advantage that was lost with the seafaring breakthroughs of the sixteenth century.Footnote 6 Our findings suggest that changing trade patterns had the dual effect of increasing the importance of proximity to the Atlantic (Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2005) while simultaneously decreasing the relevance of old, Middle Eastern trade routes, which had implications for global economic development. This provides a different perspective than Greif (Reference Greif1994), who has argued that cultural differences between ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’ societies in the realm of long-distance trade created the conditions under which European societies generated growth-promoting institutions that ultimately fostered economic prosperity. Our narrative suggests that Greif's Maghrebis and Genoese were subject to the same fundamental trade shocks and, as a result, rose or declined as a result of their similarities, rather than their differences.

Finally, our focus on the impact of changing trade patterns speaks directly to core issues in the field of international political economy. Scholars have argued that changes in the international economic environment, particularly those related to trade networks and global value chains, can induce commercial vulnerability (Gereffi, Humphrey and Sturgeon Reference Gereffi, Humphrey and Sturgeon2006) and volatility (Gray and Potter Reference Gray and Potter2012) in affected areas. Gereffi, Humphrey and Sturgeon (Reference Gereffi, Humphrey and Sturgeon2006) argue that there are strong relational components of shifting global value chains, and that countries which exist along a particular trade path become economically vulnerable to changes in that route. Gray and Potter (Reference Gray and Potter2012) examine the effects of trade openness on economic volatility and find that when states become peripheral or marginalized in an international trade network, this increases their downside financial exposure. Exploratory activities of the sixteenth century dislocated an entire network of Mediterranean-centered commerce which had prospered since antiquity (Crowley Reference Crowley2011). The result was that Western Europe ‘became the dominant society in the world’, a development that represented a ‘whole new era’ of history (Curtin Reference Curtin2000, viii).

Trade, Islam and city growth

If agricultural development created the earliest forms of wealth for world societies, it was historical trade that encouraged new heights in human prosperity. The first towns and cities typically arose in empires of the alluvial lowlands of places like Mesopotamia, as these were the first locations of systematized agriculture (Frankopan Reference Frankopan2016, 3). As urban living began to spread to other areas, political, economic and cultural life began to consolidate in cities where merchants and artisans increasingly found markets for their products (Wickham Reference Wickham2009, 24–25).

Antiquity was a period of intense and lucrative trade that fed dramatic increases in prosperity. A by-product of that exchange was the growth of major urban centers, particularly in Southern Europe, North Africa and the Levant, where relatively high levels of urbanization reflected increases in standards of living. Pre-Islamic Persian societies, for example, built sophisticated administrative systems with educated bureaucracies that eased trade by validating the quality of goods at market and maintaining a road system that crisscrossed the empire (Frankopan Reference Frankopan2016, 4). Roman provinces in North Africa and the Levant were considered the ‘bread basket’ of the empire, providing wheat, olive oil and other commodities valued by city dwellers in Rome and elsewhere. So important was the Carthage–Rome trade ‘spine’ that when that trade ended, Rome's population fell by more than 80 per cent (Wickham Reference Wickham2009, 78). While Europe became isolated from the richest Roman lands, the Roman provinces of the East continued to be urban, wealthy and sophisticated.Footnote 7

Findlay and O'Rourke (Reference Findlay and O'Rourke2007, xxii) point out that the Islamic world was the only major region to maintain sustained and direct contact with all other major regions of Eurasia during the late antique and medieval periods.Footnote 8 Long-distance trade, which leveraged the unique locational advantages of the Middle East and Central Asia, served as a driver of economic prosperity and urbanization. Many cities in the region thrived as trade centers with middlemen that profited from the exchange of goods. Lombard (Reference Lombard1975, 10) described Muslim cities during this period as a ‘series of urban islands linked by trade routes’.Footnote 9 Reliance on trade perhaps made them less likely to develop as producers of tradable goods over the long run.

Medieval Long-Distance Trade

While the medieval period did not witness a rebirth of the intense, short-haul trade of the Roman Empire, long-distance trade was an important feature of the Middle Ages, particularly for Muslim societies that were well positioned to participate in trade which sought to connect distant world population centers. Trade connecting the Middle East to South and East Asia was particularly robust: merchants used both Central Asian overland routes as well as sea routes connecting the Indian Ocean to the Red Sea. Spices, like pepper which made meat palatable, and textiles, including Indian cottons and Chinese silks, were in high demand. Holy Land Crusades beginning in the late eleventh century introduced new opportunities to reintegrate Western Europe's economy into this trade (Abu-Lughod Reference Abu-Lughod1989, 47; Blaydes and Paik Reference Blaydes and Paik2016). But the Crusades were not only critical for stimulating economic markets in Western Europe; they also enriched ‘Muslim middlemen who spotted that new markets could produce rich rewards’ (Frankopan Reference Frankopan2016, 144).

Trade was vitally important to Middle Eastern urban prosperity. Merchants made fortunes as they met the growing demand for goods from China and India (Frankopan Reference Frankopan2016, 144). For example, analysis from mid-fifteenth century Cairo suggests that the 200 most important merchants ‘possessed over two million pieces of gold each’ (Labib Reference Labib and Cook1970, 77). Court records from Bursa from the late fifteenth century suggest that the wealthiest merchants in the city were those involved in either the spice or silk trade (Inalcik Reference Inalcik, Inalcik and Quataert1994, 344–345). Lombard (Reference Lombard1975, 146) argues that the concentration of wealth in the hands of merchants encouraged them to conclude profitable deals with members of the court who spent their wealth on luxury goods.

Increasing trade fed the growth and development of what historians have called the ‘classical period’ of the Islamic city, typically described as the period between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries. Cairo – situated at the intersection of the Red Sea trade routes and overland routes to sub-Saharan Africa – was home to palaces, city fortifications and large mosques (Hanna Reference Hanna1998). Cairo's proximity to Alexandria linked it to the Mediterranean Sea. Beyond Egypt, the Seljuks introduced major innovations in the development of the urban citadel, typically located on high ground with sizable walls and towers (Kennedy Reference Kennedy and Irwin2010, 280). From Samarkand to Damascus, massive buildings and monumental structures were built as elites sought to leave a physical imprint on cities characterized by growing prosperity (Kennedy Reference Kennedy and Irwin2010, 280). Keene (Reference Keene, Luscombe and Riley-Smith2010) argues that these grand cities were the ultimate expression of civilized living during the medieval period; they contained amenities beyond the imagination of even the most sophisticated urban dwellers in Europe.

Middle Eastern and Central Asian states had a strong incentive to maintain security in the interest of ensuring long-distance trade. Caravan routes could be disrupted by war, political change and Bedouin incursions; sea traffic was susceptible to naval action and piracy (Constable Reference Constable and Fierro2010).Footnote 10 States sought to secure and maintain trade routes by building roads and armed fortresses at stopping points on major routes as well as constructing rest houses to serve merchants and pilgrims (Hanna Reference Hanna1998, 23).

To what extent did rapacious sultans hinder traders’ ability to engage in commercial activity? While it is difficult to draw a conclusion for such a large region over a long time period, scholars have offered summary interpretations for particular historical moments. For example, in Fatimid Egypt and Syria there was ‘comparatively little interference by the governments in the trade of their subjects – a fact also manifested in reasonable customs tariffs – and the generally favorable situation created by the growing needs of an economically rising Europe’ (Goitein Reference Goitein1967, 33). Although customs duties existed, Goitein (Reference Goitein1967, 61) describes the Mediterranean area as a ‘free-trade community’. Goldberg (Reference Goldberg2012, 351), writing about a similar period, suggests that merchants supplied imported commercial goods that the rulers themselves valued and sought to access. In addition, while it may have been possible for rulers to expropriate the wealth of merchants, Hodgson (Reference Hodgson1974, 137) describes this as a short-sighted strategy since traders could move or hide their assets with relative ease.

Changing Patterns of Trade in the Early Modern Period

While overland trade remained active and stable in Central Asia through the fifteenth century, trade patterns after that point were considerably less certain (Levi Reference Levi, Morgan and Reid2010). In addition, technological improvements, including advances in ship building, were critical to shifts in sea trade routes (Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri1985, 15). Da Gama's explorations, for example, allowed the Portuguese to create their own ‘silk road’ linking Lisbon with Angola, Mozambique, East Africa and, then, India and the Spice Islands (Frankopan Reference Frankopan2016, 224).Footnote 11 English and Dutch seafarers arrived in the Indian Ocean by the end of the sixteenth century, consolidating European trade influence in South and East Asia.

Declines in spice purchases in Middle Eastern cities like Alexandria and Beirut were reported almost immediately after the discovery of the Cape Route, as was an increase in the price of pepper in Cairo (Inalcik Reference Inalcik, Inalcik and Quataert1994, 341). Before da Gama's breakthrough, Middle Eastern merchants were purchasing over a million pounds of pepper a year, much of which was resold in Europe (Labib Reference Labib and Cook1970, 73). In the following two decades, however, Germany, England and Flanders began to purchase their pepper from Portuguese merchants (Inalcik Reference Inalcik, Inalcik and Quataert1994, 342). While trading activity in Cairo did not end, Cairene merchants faced a ‘considerable shrinking of a market for merchants…when the Dutch came to dominate the spice markets of Europe’ (Hanna Reference Hanna1998, 76). The real Dutch price of pepper – a distinctively ‘Eastern’ commodity – declined steadily between 1500 and 1700 despite the fact that other widely traded commodities – like sugar – fluctuated considerably over the same interval (Findlay and O'Rourke Reference Findlay and O'Rourke2007, 226).

In response to the changing nature of trade, the imperial administrations of major Muslim societies fought to maintain the continued health and relevance of the routes they controlled (Levi Reference Levi, Morgan and Reid2010). The Mamluk sultan asked rulers on the Malabar coast of the Indian subcontinent to close their markets to the Portuguese (Inalcik Reference Inalcik, Inalcik and Quataert1994, 319).Footnote 12 The Ottoman Empire sought to strengthen its commercial position by modernizing roadways and upgrading sea and land fortifications (Frankopan Reference Frankopan2016, 225).Footnote 13 The Ottoman sultan also sought to align himself with Muslim rulers in Sumatra with the goal of eliminating the Portuguese monopoly over certain trade routes (Inalcik Reference Inalcik, Inalcik and Quataert1994, 328). Muslim rulers in Central Asia, Persia and South Asia invested in the maintenance and improvement of trade routes by repairing overland roads, providing security for caravans and quieting tribal peoples who sometimes obstructed commercial traffic (Levi Reference Levi, Morgan and Reid2010).

Yet despite efforts to maintain their competitive edge in commerce, cities were vulnerable to fluctuations in the benefits derived from trade. For example, beginning in 1503 the number of vessels arriving in Jeddah from central Indian Ocean ports like Calicut and Daybul fell by as much as 60 per cent, delivering a serious blow to the local economy (Meloy Reference Meloy2015, 219). The Portuguese limited the number of vessels sailing to Jeddah from Indian ports and forced those that did to receive special licenses (Meloy Reference Meloy2015, 224). According to Meloy (Reference Meloy2015, 224), ‘although the Portuguese never completely dominated the Indian Ocean trade, they were able to reduce and even regulate the flow of its maritime commerce’. In 1514, for example, only three ships were permitted to go from Calicut to Jeddah and Aden, respectively (Meloy Reference Meloy2015, 225).Footnote 14

Most cities connecting Muslim trade routes did not experience Jeddah's immediate and dramatic fall in commerce. They did, however, face a gradual loss of population by the nineteenth century. Basra, for example, is another important city that experienced economic disruption as a result of changing trade patterns. It was historically both a sea port and a caravan city connecting Aleppo with the eastern Arabian Peninsula (Abdullah Reference Abdullah2001, 17). Merchants of Basra imported goods from India, sending back Arabian horses – which were highly valued on the subcontinent – and dates – which served as both a valuable commodity and as ship's ballast (Abdullah Reference Abdullah2001). In 1200, Basra was estimated to have a population of 50,000. By the early eighteenth century, conversations between the Ottoman governor in Basra and local merchants suggested a decline in the number of ships from India, likely as a result of the resurgence of alternative routes bringing commodities from India to Europe (rather than a decline in demand for Indian goods). While the trade eventually rebounded, there was tremendous instability in levels of exchange, which damaged the city's prosperity. By 1840, the French consular agent in Basra reported that the city's population had fallen precipitously (Abdullah Reference Abdullah2001, 55).

The Atlantic explorations also impacted the nature of Old World trade patterns. In particular, dynamism in international trade shifted from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic with the New World discoveries.Footnote 15 Cities like London and Amsterdam rose in prominence relative to the declining economic prospects of cities in Italy and along the Adriatic, which had largely linked the Middle East to Europe. According to Frankopan (Reference Frankopan2016, 255), ‘Old Europe in the east and the south which had dominated for centuries…now sagged and stagnated…New Europe in the north-west…boomed’. Formerly prominent Middle Eastern societies were unable to effectively compete in the New World economy, while Northern and Western European cities were growing rapidly, ‘in the Ottoman world…the number of cities with populations of more than 10,000 remained broadly the same between 1500 and 1800’ (Frankopan Reference Frankopan2016, 256). Karaman and Pamuk (Reference Karaman and Pamuk2010) show that per capita revenue in the Ottoman Empire was also flat over this interval, while England and the Dutch Republic were growing at an impressive rate.

Empirical analysis

Our narrative suggests that trade – particularly long-distance exchange – was a driver of economic prosperity in the medieval period. Yet reliance on trade also implies susceptibility to the effects of shocks to trade paths. In this section, we compare the impact of changes to trade to the advantages or disadvantages conferred by other factors, including geographic characteristics, religious identification or a city's proximity to other large cities. We test a series of hypotheses about the nature of urban growth and decline in the Islamic world and Christian Europe, with a focus on time periods before and after 1500 to examine the extent to which the urbanization patterns were disrupted by Europe's breakthroughs in seafaring, trade and exploration.Footnote 16

Measuring Historical Patterns of Urbanization

As suggested above, we believe that one reason for the decline of Muslim city populations relative to Christian cities relates to the loss of the Muslim world's ‘middleman’ role after the seafaring technology improvements initiated by Europeans in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. We do not suggest that these technological advancements were exogenous; these developments were the culmination of increasing institutional advantage enjoyed by European polities rooted in Europe's evolving Commercial Revolution. That said, until critical discoveries were realized – like da Gama's discovery of the Cape Route – Muslim trade routes were economically significant despite Europe's emerging economic advantages.

In order to best isolate the effect of changing trade patterns on prosperity, we investigate changes in city size between 1200 and 1800.Footnote 17 Although trade patterns were evolving before da Gama's circumnavigation of Africa and Columbus's discovery of the New World, we take 1500 as the midpoint of our analysis as it represents a disjuncture in terms of breakthroughs in both Eastern and Western exploration. We have chosen 1800 as the end point of our analysis because city size at that point represents the state of the world on the cusp of the Industrial Revolution. Our analysis begins in 1200 – a high point in Islam's ‘Golden Age’ – during which trade was of growing relevance for Western Europe and of continued importance for cities of the Muslim world.

The main source of data for our outcome variable – city population estimates for localities across Europe, Muslim Africa, Western Asia, Central Asia and Muslim South Asia – come from Chandler and Fox (Reference Chandler and Fox1974; henceforth Chandler).Footnote 18 The authors provide population data estimates for cities around the world, with increasingly comprehensive data beginning around 800 and continuing into the twentieth century.Footnote 19

In addition to population estimates, Chandler and colleagues have compiled lists of the world's largest cities (rank ordered by size) at different points in time. Population estimates are provided for many of the cities on the list, allowing us to benchmark estimated figures even for those localities that do not have city size values. For cities that have information on their ranks but are missing actual population figures, we obtain population estimates using the power law distribution of city sizes and rank information.Footnote 20

One important challenge associated with using the largest world cities lists is that a city that appears on a list for a given year does not necessarily remain on subsequent lists of top cities. Conversely, cities that rise in prominence only in later periods are missing in earlier lists of top cities. For example, Fez appears as the second-largest city in the world in 1200 with a population of 250,000, but drops to sixteenth place in 1500 with a population of 125,000, and does not appear on the list in 1800. London – listed as the second-biggest city in the world in 1800 with a population of 861,000 – is not on the list of largest cities in 1500 or 1200.

After compiling all the cities that appear at least once in any of the lists of the world's largest cities between 1200 and 1800, we assign lower and upper bounds for the population of each. Where a population estimate exists, either provided by Chandler or from the estimate based on the power law, both the lower- and upper-bound values are assigned the same estimate. If a city is missing from the list for a given year but appears on our compiled list, we assign zero as the lower bound, and the population of the smallest that does appear on the year's list as the upper bound of the city's population. In other words, a city that appears on a top list in any given period, but does not make the ‘cut’ in another year, is assigned a range between zero and the lowest estimate from the largest cities list for that year. Finally, we use Chandler's extensive population data records to fill in additional population figures for the years when a city drops off the list of the world's largest cities. We believe that data quality for cities that were ever large, or began as small and then became large, will be higher than for other cities. The prominence of these locations in any time period would have increased the incentives for historians to learn about their population size for all time periods.

Coding Dominant Religion at the City Level

Although we are primarily interested in comparing the parts of Eurasia that were near and far from Muslim trade routes before and after Europe's Age of Exploration, there were important institutional differences between polities in the Muslim world and Christian Europe that need to be accounted for. Our sample is focused on cities that were either Muslim or Christian ‘dominant’ for the specified regions.

Determining a city's historical dominant religious identification might be challenging for a number of reasons. For example, there are frequently divides between the religious identity of city dwellers versus their political leaders. We therefore relied primarily on expert accounts to help us determine the dominant religious affiliation. We used a number of sources to code the cities in our dataset, including, but not limited to: Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325–1354 (Ibn Battuta), The New Islamic Dynasties (Bosworth), The Rise and Fall of Great Cities (Lawton), A History of the Muslim World Since 1260 (Egger) and Islamic and Christian Spain in the Early Middle Ages (Glick). While our empirical approach does not allow us to track fast-changing religious transformations (for example, periods of rapid change in religious regime followed by reversion), we are able to chart the main trends in religious transformation on the time interval.Footnote 21 This variable allows us to test the effect of institutional changes for each city, which co-vary with dominant religious identification.Footnote 22

To summarize, our sample includes all cities that ever appeared on a ‘largest cities of the world’ list for places that became Muslim or Christian dominant in 1200 and 1800. We focus on cities that are designated as Christian or Muslim based on our coding of the dominant religion of the city for each year.

Empirical Approach and Results

In this section we investigate the long-term effects of historical trade on city size as well as the effect of subsequent changes in trade routes on urbanization levels. Our empirical analysis focuses on the changing relevance of proximity to Muslim trade routes on city population between pre-1500 (that is, 1200) and post-1500 (that is, 1800). Our approach follows Lieberman (Reference Lieberman2001), who suggests that a cornerstone of comparative historical analysis relies on the periodization of a historical chronology where a key marker of variation might be used to create an explanatory variable. Using this approach, the baseline relationship between the city's population and the Muslim trade routes can be described in the following way:

$$\eqalign{ Pop_{it} &= \beta _0 + \beta _1Dist2Trade_i + \beta _2Post1500 + \beta _3Dist2Trade_i\cdot Post1500 \cr & \quad+ X_i\gamma + \varepsilon _{it},} $$

$$\eqalign{ Pop_{it} &= \beta _0 + \beta _1Dist2Trade_i + \beta _2Post1500 + \beta _3Dist2Trade_i\cdot Post1500 \cr & \quad+ X_i\gamma + \varepsilon _{it},} $$where Pop it is the natural log of the city population of city i in year t, Dist2Trade i is the natural log of the city's distance to the nearest Muslim trade route in 1100,Footnote 23 Post1500 is the period dummy for 1800, X i is a vector of geographic controls, and the robust standard errors εit are clustered by city. In the above equation, we do not include city fixed effects, since Dist2Trade i is fixed for city i over time. We do, however, include a vector of time-invariant city-level controls, and adjust the standard errors for within-city correlation since our data consist of repeated observations for each city over time. Using our interval data with population estimates for each city, we utilize a generalized maximum log likelihood interval model to obtain the coefficient value estimates.Footnote 24 The coefficient β 3 captures the effect of changes in the distance to the nearest Muslim trade route on changes in city population between 1200 and 1800 CE.

The geographical control variables, X i, are drawn from a variety of sources, and we include them in Columns 2–7 in Table 1.Footnote 25 We first include the longitude and latitude of the city location, distance to the nearest coast as well as dummy variables for the different continents. As fertile lands likely sustained higher population density and overall development in history, we also include the agricultural suitability index from Ramankutty et al. (Reference Ramankutty2002), which gives the fractional value for the probability that the land will be cultivated based on its climate and soil properties.Footnote 26

Table 1. The effect of distance to 1100 CE Muslim trade routes on city size

Note: 1100 CE Muslim trade routes. Geographic controls include longitude and latitude, continental dummies for Asia and Africa, distance to coast and agricultural suitability. Robust standard errors corrected for clustering at the city level. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

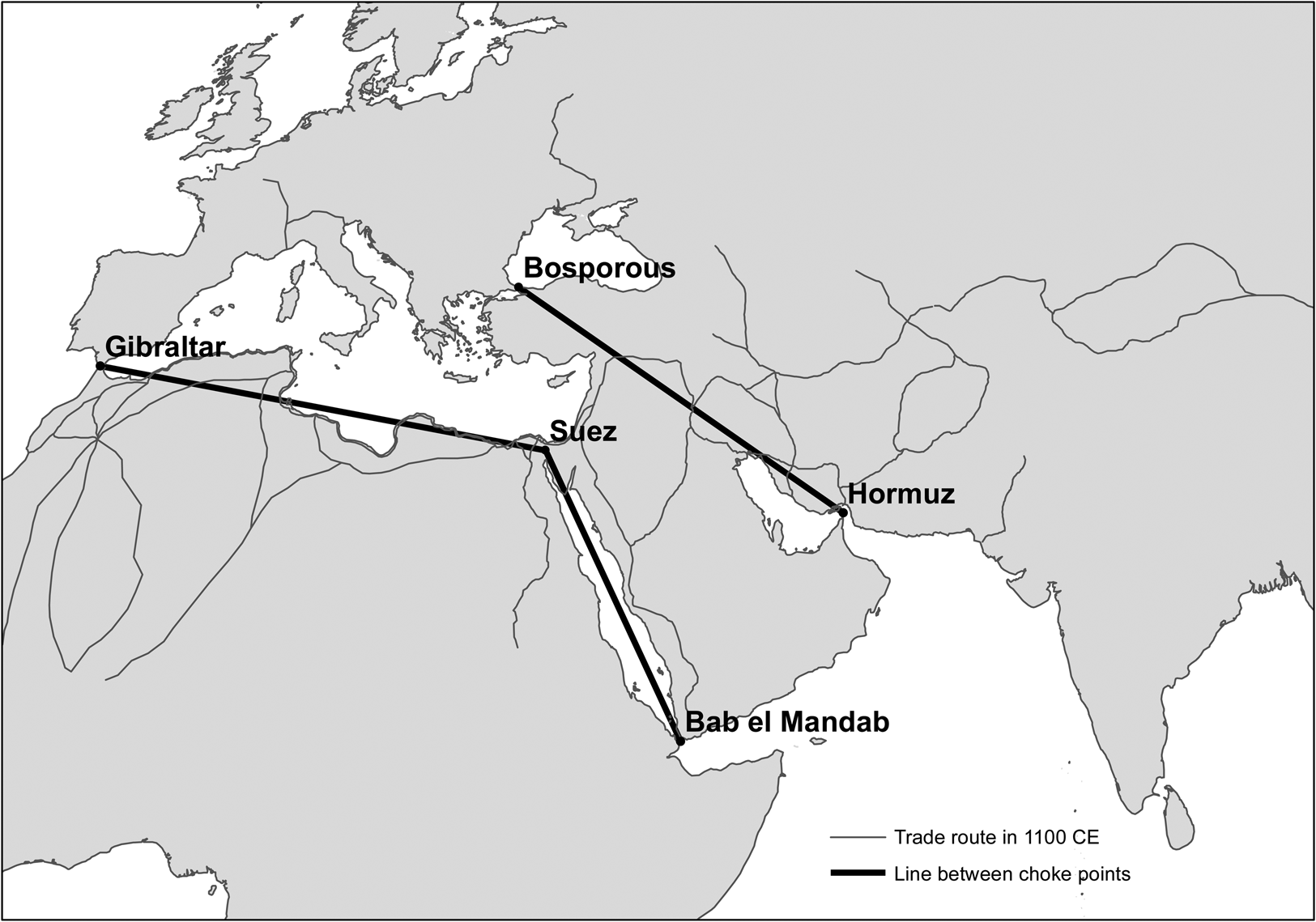

Because we believe that natural geographic features conducive to trade are important for city size, in Column 3 we control for any effect associated with being closer to the geographic connecting points between continents. Being closer to the trade route will also typically mean that some cities are closer to a ‘choke point’. We control for distance to the choke point to separate these two effects. We identify five natural geographic choke points: the Strait of Hormuz, the Strait of Gibraltar, the Bab al-Mandab (the Mandab Strait that connects the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden), the Bosphorus Strait and the isthmus of Suez. Figure 1 shows the locations of these points. With the exception of the isthmus of Suez, all of the choke points are narrow sea pathways located in between continents. These were natural connecting points for sea traders, and would have featured prominently as endpoints in the overland caravan trade routes. We also include the isthmus of Suez, which is the narrow (75 mile-wide) neck of land connecting Africa and the Arabian Peninsula; it served as a natural pathway through which the Muslim traders traveled to transport goods.

Figure 1. Lines connecting major choke points.

In Column 4, we control for whether being a Muslim, as opposed to a Christian, city had an effect on the urban population independent of its proximity to the trade routes. Muslim societies operated differently from Christian cities as a result of divergent institutional structures. Thus the urbanization of Muslim cities was likely determined by both trade as well as other institutions common to Muslim polities. One objective of our study is to understand how patterns of trade in the medieval and early modern periods impacted urbanization while also statistically controlling for a city's religious orientation.

In Column 5, we include each city's Muslim and Christian ‘urban potential’. Bosker, Buringh and van Zanden (Reference Bosker, Buringh and van Zanden2013) argue that city growth between 800 and 1800 depended heavily on whether a city was proximate to large cities with a shared religious affiliation, as interdependent trade networks that formed within religious groups contributed to economic growth. We calculate the urban potential for each city using the formula defined in Bosker, Buringh and van Zanden (Reference Bosker, Buringh and van Zanden2013) and include the urban potential outcome as an additional control variable.

Next, one might be concerned that there are cases in which the city's dominant religion was different from that of the empire that ruled it. In particular, we observe an increase in the number of cities coded as Muslim in India by 1500, but we do not have consistent information about the nature of religious conversion on the part of the city populations. The rise of the Mughal Empire in the early sixteenth century may capture an India-specific effect that is different from the general Muslim effect we have sought to characterize. In Column 6, we thus include an additional control for cities located in India.

Finally, in Column 7 we investigate the importance of the Mongol invasion in the thirteenth century, which led to the destruction of key cities in Eurasia. Devastating raids and pillaging likely contributed to changes in trade routes and the depopulation of key cities in the Middle East and Central Asia. However, there are emerging arguments for the opposite effect of Mongol rule. Peace and the consolidation of vast lands brought under the rule of a single Mongol empire created opportunities to expand trade and urbanization.Footnote 27 We use this specification to assess the impact of the Mongol expansion on urbanization.Footnote 28

Across all seven specifications in Table 1, we see that cities closer to the historical Muslim trade routes were larger in 1200 but smaller in 1800. Both the β 1 and β 3 coefficients are statistically significant at the 1 per cent level in all specifications. To understand the substantive size of the effect, consider the baseline results from Column 1.Footnote 29 Our findings suggest that a 100 per cent increase in distance to historical Muslim trade in 1200 leads to a decrease in city population of about 14 per cent, or about 6,000 people for an average sized city in our sample. The coefficient for the interaction term (β 3), however, shows that relative to 1200, cities far from historical Muslim trade routes increased in size in 1800 compared to other cities; a 100 per cent increase in distance to historical trade is associated with a 17 per cent increase in city size. These differences – while small by contemporary standards – were large for their time when city populations numbered in the thousands, not millions. The substantive significance of the pattern observed in Column 1 increases with the inclusion of additional control variables.Footnote 30

In our main specification, being a Muslim city does not appear to have an impact on city size after controlling for the distance to historical Muslim trade routes.Footnote 31 In order to better understand this result in light of the existing literature on the growth-hindering impact of the region's cultural, religious and institutional configurations, we run an additional set of empirical tests to explore the potentially time-varying impact of a city's dominant religious identification as well as tests to determine whether our results are robust within a split sample of Muslim and Christian cities. In Table 2, we replicate our main results in three additional specifications.

Table 2. Alternative specifications

Note: Geographic controls include longitude and latitude, continental dummies for Asia and Africa, distance to coast and agricultural suitability index. Robust standard errors corrected for clustering at the city level. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

In the first column, we examine the time-varying effects of being a Muslim city.Footnote 32 While in our main specification we find that Islam has no statistically significant effect on city size, in Column 1 we show the coefficient values where we also include the interaction between the Muslim city dummy variable and the variable indicating observations for 1800. Our results suggest that the effect of Muslim city status is time varying: while Muslim status had a positive effect on city size in 1200, the interaction between Muslim city status and 1800 is negative. Substantively, our results suggest that compared to 1200, being a Muslim city in 1800 is associated with a 44 per cent decrease in population size, controlling for other factors. Importantly for our arguments here, even after taking into account the time-varying effect of Muslim city status on urban growth, we find a similar magnitude of effect to our main results for distance to historical Muslim trade routes.Footnote 33

In Columns 2 and 3, we show the effect of distance to trade for just Muslim and Christian cities, respectively. These two split-sample specifications are analogous to running the main regression with an interaction term for all predictors.Footnote 34 We find the same basic patterns in terms of the sign and statistical significance of distance to historical Muslim trade routes and the interaction between distance to trade and the variable indicating 1800. It is notable that the coefficient size is even larger for Christian than Muslim cities.

In sum, our empirical results suggest that, regardless of religious affiliation, proximity to Muslim trade routes appears to have benefited city growth. This advantage, however, disappears with Europe's breakthroughs in exploration and may explain some of the decline of cities in southeastern Europe relative to northwestern Europe. While cities generally grew in size over this time period (Bosker, Buringh and van Zanden Reference Bosker, Buringh and van Zanden2013), our results suggest that by 1800, those close to historical Muslim trade routes stagnated to the extent that they became relatively smaller than those further away from the routes. While the rise of cities in northwestern Europe was spurred by the birth of Atlantic trade (Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2005), our analysis provides an alternative – and complementary – narrative for the broader effect of Europe's seafaring breakthroughs, which included the alienation of Muslim cities from their advantage in trade.

Examining Time Trends

A key assumption of our empirical approach is that urbanization patterns for cities near and far from Muslim trade routes were parallel before 1200. One way to check whether trends differ before this time period is to run a placebo test to determine whether the distance to Muslim trade routes by 1200 already had a differential effect between the previous time period – we consider 600 – and 1200. If the interaction term with the dummy variable for the year 600 is statistically significant – that is, if the distance to the historical Muslim trade routes has a differential effect even before the discovery of the Cape Route – the parallel-trends assumption would be violated.Footnote 35 We estimate the following equation, in which the omitted period (the year 1200) serves as the baseline:

$$\eqalign{Pop_{it} & = \beta _0 + \beta _1Dist2Trade_i + \beta _2600 + \beta _3 1800 \cr &\quad + \beta _4Dist2Trade_i\cdot 600 + \beta _5Dist2Trade_i\cdot 1800 \cr &\quad + {\rm X}_i\gamma + \varepsilon _{it},} $$

$$\eqalign{Pop_{it} & = \beta _0 + \beta _1Dist2Trade_i + \beta _2600 + \beta _3 1800 \cr &\quad + \beta _4Dist2Trade_i\cdot 600 + \beta _5Dist2Trade_i\cdot 1800 \cr &\quad + {\rm X}_i\gamma + \varepsilon _{it},} $$The results presented in Table 3 show that the coefficient for the distance variable interacted with the previous time period (β 4) is not statistically significant, suggesting that the effect of proximity to the trade routes on urbanization did not differ over the time periods before 1200. Figure 2 shows time trends on the mean predicted city population, in which we see the parallel growth of cities close to and far from the trade routes in the period leading up to 1200. Afterwards, we observe that the cities close to trade routes experienced stagnation between 1200 and 1800, while those far from trade routes experienced growth leading up to 1800.Footnote 36

Figure 2. Mean predicted city population in 600, 1200 and 1800.

Table 3. Pre-treatment Trends – 600, 1200 and 1800

Note: 1100 CE Muslim trade routes. Robust standard errors corrected for clustering at the city level. Includes the full set of controls from Table 1, Column 7. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Next, we focus in on the changes observed between 1200 and 1800 by taking the distance to the nearest trade route in 1500 from Kennedy (Reference Kennedy2002) as the baseline, and assessing the pre-1500 trends in 1200 versus post-1500 trends in 1800. The estimation is specified in the following equation:

$$\eqalign{Pop_{it} & = \beta _0 + \beta _1Dist2Trade_i + \beta _21200 + \beta _31800 \cr &\quad + \beta _4Dist2Trade_i\cdot 1200 + \beta _5Dist2Trade_i\cdot 1800 \cr &\quad + {\rm X}_i\gamma + \varepsilon _{it},} $$

$$\eqalign{Pop_{it} & = \beta _0 + \beta _1Dist2Trade_i + \beta _21200 + \beta _31800 \cr &\quad + \beta _4Dist2Trade_i\cdot 1200 + \beta _5Dist2Trade_i\cdot 1800 \cr &\quad + {\rm X}_i\gamma + \varepsilon _{it},} $$In Equation 4, the omitted period (the year 1500) serves as the baseline period, and 1800 as the post-1500 period. The interaction of the year 1200 dummy variable and the distance to trade route allows us to test for pre-1500 trends. The interaction of the year 1800 dummy variable with distance to the trade route in 1200 gives information on the direction and magnitude of the proximity effect by 1800. Table 4 presents the results. We find support for the parallel-trends assumption, as indicated by the statistically insignificant β 4 coefficient estimate. From 1500 to 1800 we observe the ‘reversal’ result, in which the proximity effect reverses its sign. This result is primarily driven by the relative rise of cities far from the trade routes and the stagnation of those closer to the routes after 1500, as indicated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Mean predicted city population in 1200, 1500 and 1800.

Table 4. Pre-treatment Trends – 1200, 1500 and 1800

Note: 1500 CE Muslim trade routes. Robust standard errors corrected for clustering at the city level. Includes the full set of controls from Table 1, Column 7. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Instrumental Variable Analysis

As is common in the literature examining the effects of trade on growth, we wrestle with the question of how to take into account endogenously created trade networks. Scholars of trade history suggest that the location of trade entrepots and routes is a function of a variety of factors, including geographical features, historical trajectories and economic conditions (Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri1985, 161). Scholars seeking sources of exogenous variation in the location of routes tend to either use old transportation routes as a source of quasi-random variation or to rely on a sample that is inconsequential in the sense that unobservable attributes do not impact the placement of trade or transportation networks (Redding and Turner Reference Redding and Turner2015).

We adopt an IV approach to mitigate these concerns. As an IV for the distance to the Muslim trade routes in 1200, we construct line segments between five natural sea and land choke points across North Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia. The lines connect the Strait of Gibraltar and the isthmus of Suez, the isthmus of Suez and the Bab el-Mandab, and the Bosphorous Strait and the Strait of Hormuz. The line segments are meant to capture historical trade networks (see Figure 1). We note that major end point cities along the Muslim trade routes located themselves near these points and, as such, the lines connecting these choke points also approximated the travel routes connecting the cities. For example, Cairo, located close to the isthmus of Suez, was a major destination for Trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean trade, as it enjoyed relatively easy access to the southwest and northwest corners of the Mediterranean, respectively. Fez is Morocco's imperial city located closest to the Strait of Gibraltar, Constantinople (later Istanbul) is on the Bosphorus Strait, and Sana'a is the largest major settlement near the Bab el-Mandab (that is, the Mandab Strait).Footnote 37

Our empirical strategy draws on the idea that the connective line segments would have no reason to go through regions of particular significance, other than that those regions represent the shortest path between natural choke points. That is, the lines are not drawn intentionally to go through historically important cities, proximity to which would necessarily mean larger populations by construction and not by proximity to a trade route. We also assume that the distance to the line segment is an excludable instrument for Muslim trade routes, and that no other transportation network may have developed due to urbanization during this time period.Footnote 38

Our analysis first requires that we validate that the line segments actually capture the historical trade networks.Footnote 39 Table 5, Column 1 shows the first-stage result, in which the distance to the nearest Muslim trade route in 1200 is regressed on the distance to the nearest line segment connecting the natural choke points, along with other control variables. We find that the distance to the nearest line is positively correlated with distance to the nearest Muslim trade routes.Footnote 40 In particular, a 10 per cent increase in the distance to a line segment connecting the natural choke points is associated with a 7.5 per cent increase in the distance to the nearest historical Muslim trade route; this coefficient is statistically significant at the 1 per cent level. Next, Column 2 presents the result in which the distance to the nearest trade route is instrumented by the distance to the line segment. We find that, consistent with the findings in Table 1, the distance effect on city population remains negative in 1200, while the differential effect of distance on city population is positive by 1800.Footnote 41

Table 5. Instrumental variable regression

Note: robust standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered at the city level. Includes the full set of controls from Table 1, Column 7. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Robustness Checks

In this section, we consider our findings in light of two sets of robustness tests – empirical evaluation with additional control variables and consideration of alternative time spans for our analysis.

Additional control variables

Although we have included a number of geographic, economic and political control variables in our main specifications, in this section we consider additional factors that may explain city size. We consider various historical and regional developments in Europe that may confound our main results that we have not yet accounted for in our empirical analysis.

The specifications reported in Table 6 maintain all the same control variables used in Table 1 and include a number of additional control variables. In Columns 1 and 2, we include measures of Carolingian political influence and Holy Land Crusade mobilization, respectively, as both have been suggested as historical channels that might impact the development paths of cities (Blaydes and Chaney Reference Blaydes and Chaney2013; Blaydes and Paik Reference Blaydes and Paik2016). In Column 3, we include a dummy variable for whether a city was located in one of the Low Countries (for example, Luxembourg, Belgium and the Netherlands). The Low Countries have been thought to enjoy geographic and institutional structures that led to better economic growth and greater urbanization compared to the rest of Europe (Mokyr Reference Mokyr1977; van Bavel Reference Van Bavel2010). We also check for effects related to the European ‘city belt’ in Column 4; this region encompasses northern Italy, areas of the Alps and southern Germany, as well as the Low Countries. The cities along this belt formed strong trade networks particularly along the Rhine River and Baltic Seas during the High Middle Ages, allowing them to remain strong enough to deter expansion efforts by territorial states (Abramson Reference Abramson2017).

Table 6. Robustness check – additional control variables

Note: 1100 CE Muslim trade routes. Robust standard errors corrected for clustering at the city level. All columns include the full set of controls in Table 1, Column 7. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Next, we include a Roman Empire control variable in Column 5. Roman roads facilitated trade within the European city belt and other parts of Europe by providing critical infrastructure that supported economic development (Dalgaard et al. Reference Dalgaard2017). And because Roman roads not only covered European cities but also many cities in North Africa, Anatolia and the Levant, we are able to include this variable for both Muslim and Christian cities in our sample.Footnote 42

In Column 6, we include an Ottoman Empire control variable. From its beginning in the fourteenth century through its expansion until the late seventeenth century, the Ottoman Empire controlled many of the most important Muslim trade routes in the Mediterranean Sea, Persian Gulf and Red Sea regions. The consolidation of different parts of the Middle East under a single imperial polity may have led to the growth of cities, especially during periods of the empire's expansion.Footnote 43

Finally, we examine the impact of Atlantic trade on urbanization in Column 7. The growing success of Atlantic coastal cities in maritime trade and exploration was associated with the ability of Atlantic traders to seek their own routes to both the East and the New World. In particular, a reorientation of trade toward the New World strongly advantaged these locations. Being an Atlantic trading city, therefore, may have helped a city to grow with an expectation that this impact would increase over time.Footnote 44 We follow Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2005) in identifying cities that are located in Atlantic states (we code England, France, Portugal, Spain and the Netherlands as ‘Atlantic Countries’), and control for the Atlantic effect to explore whether proximity to Muslim trade routes remains statistically significant.Footnote 45

In Table 6, we find that including these potential confounding variables in our analysis has little impact on the magnitude and statistical significance of our main effects associated with the time-differing impact of proximity to historical Muslim trade routes on city size.

Alternative time intervals

Next, we examine whether our main empirical results are robust when examining periods shorter than the 1200 to 1800 time span. In all of our alternative specifications, 1500 still represents the midpoint in our analysis and we close the temporal window around 1500. Table 7 presents the results where the pre-1500 period of analysis begins in 1400 and the post-1500 period of analysis ends in 1600. For this exercise, we measure each city's distance to the nearest Muslim trade route in 1400, and compare city populations in 1400 and 1600.Footnote 46 Our results are similar to those found in our main specification presented in Table 1; cities closer to the Muslim trade routes are likely to be larger before 1500, while increases in the distance from the routes are associated with increases in population post-1500. The magnitude of the differential effect is smaller for the shorter time intervals, however. In Table 7, β 3 values range from 0.04 to 0.05, while the range is from 0.17 to 0.19 in Table 1. It is not surprising that the magnitude of the effect is smaller than in the main specification given the shorter time span for the analysis.

Table 7. The effect of distance to trade routes on city size: 1400 vs. 1600 CE

Note: 1300 CE Muslim trade routes. Robust standard errors corrected for clustering at the city level. Geographic controls include longitude and latitude, continental dummies for Asia and Africa, distance to coast and agricultural suitability index. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Appendix Table A.6 replicates the main results in Table 1, but takes 1300 as the pre-1500 CE period of analysis and 1700 as the post-1500 period. Appendix Tables A.7 and A.8 present the results from the split-sample analyses in Table 2, but for the shorter time spans. Similarly, Appendix Tables A.9 and A.10 provide robustness checks for the analyses using the shorter time spans and with the inclusion of additional control variables. We find highly similar results with the inclusion of the additional controls.

Conclusion

When and why did once thriving urban centers across Eurasia fall into decline, sometimes abandoned by the wider world? In the year 1200 CE, most of the largest cities in Western Europe were inhabited by just tens of thousands of individuals, while Middle Eastern and Central Asian cities – like Baghdad, Marrakesh and Merv – had upwards of 100,000 residents each. Evidence from a variety of sources suggests that part of this prosperity can be attributed to the pivotal role Muslim cities played in long-distance trade. Strategic location was crucial, as ‘Islam occupied a key position, at the point of intersection of the major trade routes’, connecting the two most important economic units of the period – the Indian Ocean trade zone with the Mediterranean Sea (Lombard Reference Lombard1975, 9–10). The cities that mattered were not Paris or London but rather those that ‘connected to the East…cities that linked to the Silk Roads running across the spine of Asia’ (Frankopan Reference Frankopan2016, 125).

How and why, then, was this pattern so decisively reversed? Muslim lands of the Middle East and Central Asia benefited from locational centrality, conferring on those societies a comparative advantage in bridging world regions through trade. We find that trade centrality is a more consistent predictor of city size than Muslim religious identification, and that the impact of trade on city size is robust to a variety of measurement strategies and empirical specifications. The changing influence of proximity to historical Muslim trade routes is not driven by improvements to the prospects for Atlantic cities alone. Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2005, 547) suggest that ‘areas lacking easy access to the Atlantic, even such non-absolutist states as Venice and Genoa, did not experience any direct or indirect benefits from Atlantic trade’. We go even further to suggest that these cities not only failed to benefit from Atlantic trade but also suffered a major trade shock as a result of the discovery of the Cape Route – a world historical event that occurred contemporaneously with the Atlantic discoveries.

Our findings also suggest an indirect channel through which European institutional advantages damaged the economic prosperity of the Middle East. Rather than a conventional narrative about European exploitation of colonized peoples, European discoveries of new trade routes – an outcome likely driven by growth and investment-promoting institutions – made Middle Eastern middlemen obsolete and damaged the region's development prospects.Footnote 47 According to Cliff (Reference Cliff2011, 361), ‘for nearly a thousand years, trade…had been conducted on Muslim terms…suddenly, the Portuguese had torn up the old order…swaths of the Islamic world were faced with economic decline’. Indeed, the ‘conquest of the high seas’ conferred an advantage to Europe ‘that lasted for centuries’ (Braudel Reference Braudel1967, 300). Findlay and O'Rourke (Reference Findlay and O'Rourke2007, 304–305) write that by the ‘middle of the eighteenth century, the international economy had been transformed out of all recognition from the system that had existed at the beginning of the millennium’.

What might have happened to Muslim cities had the European Age of Exploration not occurred? Middle Eastern merchants had an influential role in medieval Muslim societies, particularly compared to Europe, where ‘elite power was based in the countryside and the rural estate’ (Kennedy Reference Kennedy and Irwin2010, 274). Given the importance of trade in medieval Muslim cities, merchants were an influential social group that had the potential to organize politically. But because the returns from trade were so lucrative, merchants were focused on securing and maintaining trade routes rather than developing new lines of commercial activity. For example, Labib (Reference Labib and Cook1970, 73) argues that in trade entrepots like Venice and Egypt, commercial middlemen were ‘dealing less in the export of its own products’ than in transit trade. While we cannot know with any certainty if the Middle East would have developed representative assemblies or more secure property rights in the absence of a trade shock, at the very least Europe's exploratory developments accelerated the decline of Middle Eastern economies and may have contributed to institutional underdevelopment through a weakening of the native merchant class.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EHW8MI and online appendices are available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000267.

Acknowledgements

We thank Carles Boix, Benjamin de Carvalho, Saumitra Jha and seminar participants at the University of Pennsylvania, Stanford University, United Arab Emirates University, University of California Davis, University of Washington, Yale University, Waseda University and Yonsei University for helpful discussions.